#like 'x piece of fiction has Implications i want to discuss' can and should be separated from like. scarlet letter on author‚ probably

Text

there's context here but frankly making a real post abt this would require my brain to be in better shape so this is just the little orphaned scratchpad version, but like

everybody's always on about, like, fanfic is just an amateur peer community so we can't critique it the way we would Real Lit bc the power dynamic is different and everybody involved is tender and delicate

but like. how many readers have to Only Read Fanfic—which like, i have no actual numbers but anecdotally that seems like it's more and more of a thing—before it's like, actually fic has effectively grown up and become the Man it was imitating. also frankly plenty of BNFs *do* in fact have status and influence over their audience, like, yeah they typically are more *accessible* to their audiences than pro authors and if yr going to take advantage of that by addressing them directly it does in fact behoove you to treat them like an actual person rather than an Invulnerable Content Purveyor, as in fact you should be treating *everyone* you interact with on the internet despite all of our facelessness, but like

kinda feels like fic has in fact reached a level of visibility and influence with the reading population where this whole argument that like, it can do whatever it wants while we can't point at anything it's doing as being an issue in any way starts to feel a little dubious to me?

#like this IS complex and i hope it doesn't sound like i'm saying i think X random fanfic writer is on the same level as Y bestselling author#but like. with the rise in AO3's visibility and the way a lot of people seem to be favoring fic with content warnings over unlabeled tradpub#it feels like. you've got a field that now has huge influence but apparently critique remains unthinkable#and it's just like. idk. if fic is shaping readers' expectations to the extent it seems to be... we need a forum for critique#i get that maybe that forum is not 'the same social media where the fic authors themselves are hanging out'#and also like. in general i think critique ought to be less ad hominem regardless of writer status‚ probably#like 'x piece of fiction has Implications i want to discuss' can and should be separated from like. scarlet letter on author‚ probably#but. idk#anyway i imagine those of you who write fic will have some pushback for me and i'm open to it#but like. idk. i'm just not totally convinced fic is such a small subculture anymore that it should get a critique pass#truly am feeling v stupid atm though so like. dandelion brain disclaimer

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Maybe its not supposed to be a racism allegory. It still works for the story and worldbuilding. Just like Beastars, where attempts to compare it to real life won't work since the problems the characters face are really specific to their own society and their own nature, so the story wouldn't make sense if you replaced them with humans. But if the allegory really was the author's intent, then you're right and it was poorly done.

alright. i want to give you the benefit of the doubt, but there is a bit of ignorance to what you say. so i’ll be as thorough as possible about my thoughts.

authorial intent is really powerless when it comes to what a piece of media says or does. if a piece of media harms, but the author did not mean it to harm, does that make the harm any more less?

content creators and content consumers alike are likely familiar (and if not, should be) with the notion of ‘death of the author.’ from tvtropes’ summary of the concept:

Death of the Author is a concept from mid-20th Century literary criticism; it holds that an author's intentions and biographical facts (the author's politics, religion, etc) should hold no special weight in determining an interpretation of their writing. This is usually understood as meaning that a writer's views about their own work are no more or less valid than the interpretations of any given reader. Intentions are one thing. What was actually accomplished might be something very different. The logic behind the concept is fairly simple: Books are meant to be read, not written, so the ways readers interpret them are as important and "real" as the author's intention. [...]

Bottom line: A) when discussing a fictional work with others, don't expect "Author intended this to be X; therefore, it is X" to be the end of or your entire argument; it's universally expected that interpretations of fiction must at least be backed up with evidence from within the work itself and B) don't try to get out of analyzing a work by treating "ask the author what X means" as the only or even best way to find out what X means — you must search for an answer yourself, young seeker. Writing is the author's job; analyzing the work and drawing conclusions based on it is your job — if the author just gave away the answers every time, where would the fun be in that?

>interpretations of fiction must at least be backed up with evidence from within the work itself. okay, fine. so i argue brand new animal is a racism allegory. let’s look within the show to find evidence of this.

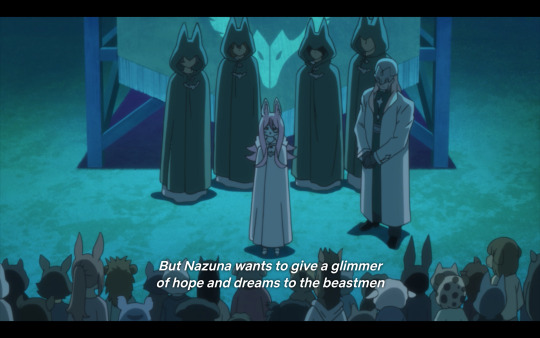

from episode 9: “But Nazuna wants to give a glimmer of hope and dreams to the beastmen who’ve been persecuted and suffered for so long.”

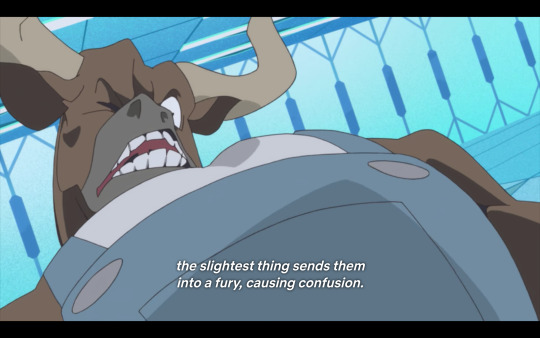

'the beastmen who have been persecuted.’ what exactly does that mean? persecution as defined in mac’s dictionary function (which cites new oxfords english dictionary): hostility and ill-treatment, especially because of race or political or religious beliefs.

the beastmen are not oppressed because of who they believe in, so not of religious beliefs or political beliefs, with the exception of believing they deserve rights, which plays into... that they are persecuted for race.

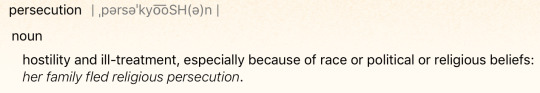

i dont really think i need to back up that statement, but for the sake of a sound argument, this is from episode 1.

it’s clear that this human dude has a distaste for michiru here because of what she is, a beastman, which is essentially what she is, her race. hence racial persecution, or, racism.

in your own words, “attempts to compare it to real life won't work since the problems the characters face are really specific to their own society and their own nature, so the story wouldn't make sense if you replaced them with humans.”

is the above exchange really so displaced from real life? this kind of thing really does happen; being targeted and even beat up simply for existing as you are is not something that is so specific to only the world of bna.

sure you may argue that replacing humans into the whole story would not make sense and well sure, yes. it is indeed a work of fiction so it won’t be a perfect replication of the human experience. but there is enough situations like the above to argue it mirrors racial prejudice in real life.

the evidence is there, so with the philosophy of “death of the author,” it is arguable this piece of media exists as a racial allegory, whether or not trigger wrote it to be that way. if they somehow did not have real race/minority relations in mind when writing this, which i would find very hard to believe, than it has still become bigger than them. because people who face racism will relate to scenarios such as beastmen being the target of hate crimes like the above, and nothing the authors meant to do really changes that feeling.

when such a scenario as above is set up in the very first episode to give you a picture of what this persecuted group experiences, while simultaneously likening itself to what minorities in real life experience, the treatment in following episodes of said group will reflect back as commentary on real life groups whether or not the authors intended that.

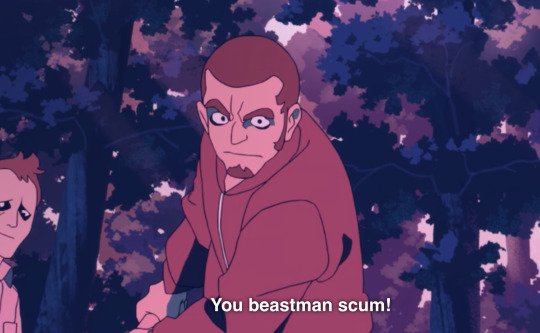

in bna’s case it’s rather damaging with implying this minority group is prone to rage and destruction because of their nature or dna:

episode 9: “Beastmen are easily influenced by their emotions. When their frustration builds up, the slightest thing sends them into a fury, causing confusion.”

episode 10: “The stress from multiple species invading your habitat accumulates subconsciously. In that situation if there is a powerful mental shock, the enrage switch in beast [dna] is set off, and their fight instincts take over.”

this is where you may argue in your own words “the story wouldn't make sense if you replaced them with humans.” which, yes that is true, but again this is fiction. the dynamic they establish in that first episode with beastmen being persecuted by humans is one founded in real race relations so the show at large becomes a vehicle to which it addresses race relations.

ep 10: “They’re [the drug vaccine that cures beastmen of being animals] made to subdue beastmen who have turned savage.”

goodness this almost becomes about eugenics! which is another movement founded on racism and other -isms!

the word “savage” generally refers to wild, violent unconfined animals, which, fine, i suppose, after all these ARE animal people in the show. but the show has established this animal people group as a targeted victim minority. historically in real life, the word “savage” has been a label used to describe many persecuted groups, like indigenous peoples or african americans, in a way to dehumanize them by comparing them to animals and force the idea that they are uncivilized while making the people in power feel more justified about their rough treatment of the targeted group.

i suppose arguably they are using the word “savage” to describe animals as the word originally was intended, but after establishing the framework of these animals as being persecuted peoples, do you understand the implications? are they basically saying yes, targeted minorites, are savage? admittedly i will say that that idea is a big jump, but even if you stick to the world of the show, basically this establishes that everyone is at the mercy of their genes turning them bad... not a great message.

i kind of went beyond the scope of what you addressed in your message, but wanted to show an example of how i think it is very important to consider how a piece of media can very easily become bigger than its creators, and that you cannot hide behind authorial intent saying otherwise when media expresses potentially damaging ideas.

to reiterate the line from tvtropes: Intentions are one thing. What was actually accomplished might be something very different.

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Steven Universe Future 3-13-2020

Together Forever: This episode was a lot less about Steven and Connie, and more about just Steven than expected.

Connie has some plans for college, but we don’t quite get to know what her career goals are exactly. She’s planning on getting into politics, but I’m not sure at what level or what branch. Not that that matters to the episode too much or anything. The University of Jayhawk is all the across the country from Delmarva. This is a distance that Steven cannot emotionally handle right now. Upon this realization, he sinks down into his bed, part of his “floating” powers.

It is good to see that he and Connie keep in touch at least over video calls. On a slightly more concerning note, Steven has memorized Connie’s schedule down to the minute.

Garnet says at the end of the episode, that there was no future in which Steven wouldn’t propose to Connie. I’m guessing had he talked to Garnet instead, he would have proposed to her out of spite or in an effort to prove Garnet wrong.

Instead of Garnet, we do get Ruby and Sapphire this episode. Steven doesn’t seem too surprised by their appearance in this episode, so I imagine that they have been teaching these classes for a while. Ruby is doing some kind of nature scout class, did she make those badges herself, or are they part of a nationally recognized scout organization? Either way she’s teaching some gems and Onion about the beauty of nature. Steven tells her about how Connie seems to really have her life together and knows what she is doing.

I can see a parallel here with Ruby and Sapphire, and Steven and Connie. In this particular case, Steven is Ruby. He doesn’t have the foresight that Connie does right now. He, in a way, lacks future vision.

Ruby, either lacking the knowledge of what might be socially acceptable or being too excited about prospect of Steven expressing his love, tells Steven that he should propose to her. Ruby’s logic here is that it worked for her. She ignores the fact that she and Sapphire had been together for over 5000 years and that they are adults.

Steven visits Sapphire as well, she is teaching a class on alternate timelines. I wonder what that entails exactly. I suppose that they do all of those equations that she explained to Steven, but with the understanding that the future still isn’t as predictable as one might think. She also encourages Steven to propose to Connie despite the fact that she is aware of the sociological implications of this, but she’s a hopeless romantic about it anyways.

Steven declare to the gems, that this will be his last day as Steven Cutie-Pie Demayo Diamond Quartz Universe. Interesting that that interaction with Garnet from almost 4 years ago left that impression on him. That is the same day that he learned about future vision, so I suppose that just stuck in his mind. Also, was he planning to take Connie’s last name or add Maheswaran to his plethora of middle names (that he thinks belongs on official documents for some reason).

He makes his plan. He gets jam, glow sticks and cake. On top of the world, he dresses his best and asks her out from outside her window. He says they’ll be back in 15 minutes (this reminds of an episode of How I Met Your Mother, but the season and name escape me).

At the beach, in the same place they first met, Steven has a picnic set up. Had this just be a romantic gesture or a proposal to date, not marriage, things probably would have gone a lot better for him. Connie responds well to all this. She has been shown to have romantic feelings for Steven in the past, she attempted to kiss him in An Indirect Kiss and she successfully kissed him on the cheek in the movie. Steven sings his song with the sentiment of “I want to be me with you”. The lyrics of which, like many love songs in my opinion, have a codependent quality to them. Steven doesn’t know his future, so he wants someone else to be his future, to be someone else.

Connie, very sensibly, says no. They are young, have never discussed this, and I’m pretty sure they aren’t even an item. She also tells him, “It’s a not now” because there is plenty of time. Steven is in his unending quest for stability, and he still hasn’t found it. Throughout this conversation Connie and Steven occupy opposite spaces on screen. They are in different places in their lives right now, sure and unsure, stable and unstable.

I think if Steven were around more teens his age, he might not be feeling this way, so much at least. He would realize how many people don’t have their lives figured out at this age. Many people his age just want to graduate high school. He really needs to talk to Greg about this. Greg wanted to be a musician, but he was also a community college drop out. He didn’t have everything figured out. (I’m pretty sure this will be part of next week’s episodes in some way)

Connie is willing to stick around when her alarm goes off. Steven tells her to go, probably because he doesn’t want to burden her and because he won’t be holding it together for long. As soon as she leaves, he lies back and creates a crater. The shockwaves ruining the picnic. He lies there until dark.

When he gets up, Garnet is there. She explains to him the inevitability of this situation. She tells him that the hole he is trying to fill won’t be filled by Connie or Stevonnie. Connie is not his “missing piece”. In this scene, Garnet is towering and Steven feels almost as small as his younger self. I think this accentuates how young and foolish Steven was this episode. He holds a frustrated look during this conversation. He says he blames Garnet for making this all look so easy. Reminds me of Cry for Help/Friendship. Pearl had felt the same way about Ruby and Sapphire/Garnet. Steven and Pearl craved that perceived perfection.

Steven then eats his feelings.

Growing Pains: I was wrong in my prediction that Steven would either be stuck in pink mode or have a human ailment.

The episode opens with a scene from the newest instalment of dogcopter. In the movie, Dogcopter proposes to a dog named Drew. Steven laments the fact that “everyone else is getting married”. He continues to eat his feelings like at the ending of last episode, and then his body starts getting out of control. He keeps growing sporadically. He mostly ignores it because it doesn’t hurt him physically.

He wants to reach out to someone who isn’t Connie right now. He can’t reach the gems, so he calls Greg, who is on tour with Sadie and Shep right now. Greg is having a great time, and Steven won’t rain on that parade, even when Greg offers to call him back. He almost wants to call Connie, but she calls him instead. His shapeshifting forces him to answer her call.

He can no longer hide what’s going on with him, since it is manifesting physically. Connie suggests that he should see a doctor. He doesn’t want to bother anyone even when he is physically unwell. He even describes it as a waste of time. Connie persuades him.

Steven pays Doctor Maheswaran a visit, Connie escorts him in. As soon as Connie leaves the room for them to conduct tests, she calls Greg.

This episode really explores how both human and gem Steven really is. He has a human body and it is effected like a human body is. But he is also a gem, it makes his body react unusually and if he’s fractured skeleton is any indication, it is keeping him alive.

Dr. Maheswaran finds out about Steven’s physical traumas through his x-ray. She asks him if he had any particularly traumatic experiences. Steven basically recalls the entire show. Dr. Maheswaran goes on to describe the physical aspects of trauma and the way the body reacts in a way I don’t think I’ve ever seen in any piece of fictional media. Steven’s body is trying to protect him from danger that isn’t there anymore. Minor stress to him is now the equivalent to major stress. To make things worse, he feels as though his support system is gone.

When he thinks back to the proposal, things go haywire. As his body continues to grow in size, he takes up more and more of the room. He is almost too big to fit. There is nowhere left for him to hide. He yells “I can’t be around you right now” much in the way he yelled “I just want to fix it” back in Volleyball. His yell shatters the windows.

Greg finally arrives, revealing that Connie had called him. Connie still very much cares about Steven. He explains to Greg that everything feels like the end of the world to him now.

Receiving understanding and support from Greg is what gets Steven to go back to his normal size. At home he continues to explain his fears and worries. All of which, as Greg explains, are normal. Steven now knows what his problem is, or at least one aspect of it, but I don’t think his problems are solved just yet. From the way he “swells up” in response to stress in this episode, I think something big is about to happen in the show. Something so big, that for his body to protect him from it, he will grow into the giant monster from the opening theme song.

Predictions for next week:

Discussion of leaks ahead

Mr. Universe: Still no episode description for this one, but I imagine this is where Steven crashes the van. Steven is still not in a great place right now, and while he seems more willing to talk about things, his body is still reacting in a way that is unsafe for him and others. I believe that this will lead to the van crashing. As others have pointed out, this episode may involve Pearl because she played a big part in the episode Mr. Greg. I still somehow think this episode will be the story of how Rose decided to have Steven, if not it will be about how Greg made the decision to drop out of college and take on the rockstar persona Mr. Universe.

Fragments: This is where that first leak came from, the “leave me alone I need space one”. I’m still not 100% sure what “fragments” is in reference to. Others I have discussed with have suggested memories. I am not entirely sure the direction of this.

#steven universe#steven universe future#su spoilers#suf spoilers#su leaks#suf leaks#long post#j posts about stuff#c#corrupted steven theory#Did tumblr like just eat this post or something#what's going on???

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Advice, the Completed Version

This is a follow up to this post: https://whatspastisprologue-blr.tumblr.com/post/184968470815/writing-advice. I’d written that on my phone, I think, and goofed somehow, so I didn’t post the entire thing.

Now, to start, I love reading what you guys have to say, and I consider you guys basically geniuses. You spend hours, or what seems like hours, analyzing SPN (and also other works as well, but mainly SPN), and you’re willing to put up with horrible backlash from people too dumb to realize they’re wrong.

And I keep thinking how I would love to write something, be it a novel or a TV show, that people love so much that that they’re willing to write meta for it. Contrary to what I’ve seen around about some creators being upset when their audience figures out what’s going on, I’d be delighted to know that people care so much that they pay close enough attention to figure it out. As for things like subtext, I see myself jumping up and down like, “You’ve got it! I thought you would! I put that in there to see if you’d notice and you did! Yay!” To me, meta has become a high form of praise just by its existence, but from the standpoint of literary criticism and how art both reflects and transforms society, also absolutely necessary. Please, critique art!

Which leads me to part two: how do I actually put stuff into the work for people to write meta about? Like, I’ve seen mini-essays ranging from fictional parallels/references/shout-outs to alchemical practices to entire discussions about, for instance, specific shirts (”x character is wearing x shirt again!”) to various pieces of decor to the meaning of various types of food (bacon, cake versus pie, burgers) and how food is used (Sam and food, or Cas and food). I’ve seen posts written analyzing songs used in episodes and how they inform the episodes or a character’s arc, etc. I’ve watched fascinating yet trippy videos about narrative spiral that make me wish I was approximately 400% smarter so I could properly appreciate and understand what I was watching. I’ve seen meta about colors and symbols, and the symbolism of different types of beer, which means that someone must have thought of it.

Someone, at some point, decided, “let’s have a beer that symbolizes family, a family beer”. And others agreed. And someone else, or perhaps that same person, decided, “let’s have a beer that shows up whenever things aren’t as they seem”, and again, others agreed, so now we have a running list of El Sol appearances.

I’ve seen some truly mind-blowing, fantastic meta that’s been written, but obviously, that analysis works because there’s something to analyze. It wasn’t pulled from nothing, as some mistakenly believe. We can talk about the Red Shirt of Bad Decisions because there’s evidence for it in the text. Someone put it there. Someone made sure to include El Sol enough times in episodes with a similar theme (things being not what they seem/alternate realities/djinn hallucinations) that we can talk about its significance and know, in upcoming episodes, that when we see that beer, it’s a sign that there’s incorrect assumptions being made by characters, that what we see isn’t necessarily real, etc.

So, how do I put content into a work so that people can pick up on it and then write about its meaning and significance?

I guess, relevant to this, is a third question, that could possibly help me figure all this out as well: what makes “Supernatural” worth writing all this meta about? That might not be phrased right to get my meaning across. While, granted, I have fandom lanes that I stay in, so I could just be unaware of meta being written for that work, but I don’t hear of people analyzing, say, “Psych”, or “Bones”, or “NCIS”. I don’t hear of long, in depth-articles about how food is used on “Glee” to give insight into a character’s mental/emotional state or closeted bisexuality. Is that just because there’s nothing to write meta about for those shows, or is it because, even if there is something to write meta about for those shows, “Supernatural” lends itself to that analysis and criticism in a way those other television shows don’t?

On a related note, people have been publishing books and YouTube videos and even teaching college classes at least partially about “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and its spin-off, “Angel”, for 20-odd years. Is all of the meta surrounding “Supernatural” the progression of that phenomenon, with SPN at least partially reaping the benefits of what BtVS helped establish? Does it have something to do with being a paranormal genre show?

Don’t get me wrong, I truly and wholeheartedly believe that SPN is a show worth writing meta about, and I’m always excited to see more of it. So it’s not whether or not the show is worth it that I’m questioning, but what specific qualities contribute to the show’s worthiness that so many other television shows don’t seem, to my knowledge, to have?

As a budding literary critic, meta is fascinating; as a creator, it’s kind of overwhelming, because that’s a lot of analysis of a work, a lot of studying with a magnifying glass. But, as someone who’s starting to see the willingness of people to write meta as a benchmark or grade of how good that work is (because people, I would assume, wouldn’t spend several hours writing an analysis of a show that sucked), it means that I want to do a good job of putting things in there for people to pick at, and I want to do what I can to make sure that what’s being analyzed is something good (as in, the messages are positive and/or useful, no harmful lessons or unfortunate implications).

I’ve been working on the backstory for my series for at least a year now, and I still feel like I’m less than halfway done. I don’t want to start writing without a clear plan of where I’m going, at least for a little while (my idea is to have a few “little endings”, thinking for if this is going to be a TV show one day, and if the show gets cancelled before the “Big Ending”, I still want there to be an ending that’s satisfying, even if it’s not the Big Ending that I hoped to get to, so I suppose I could plan to the first little ending). Sometimes, I feel like I’m behind, drastically behind, that I should have at least one book (or season) planned by now, but then I think about how I’m still in my early twenties, and how I want to write something worth writing meta about (and thus, the work needs to contain something to write meta about) and part of me wants to freeze and is grateful that the going has been slow so far.

But, with “Supernatural” ending, and given my love for the sandbox that it’s helped define and re-define, with episodes that push the bounds of storytelling in so many fascinating and delightful ways, given my appreciation for shows such as SPN, BtVS/Angel, and Wynonna Earp (and also Stranger Things and Lucifer), I’m inspired to write. Part of it is to honor SPN’s legacy by re-defining the sandbox even further, by taking what it’s done so wonderfully and, sort of like a relay race, doing my part to carry the baton a little farther--because that show has been so amazing that, since I truly love and appreciate it, how do I not pay it forward? Pay tribute? How could I just drop the baton? And part of it is because the general sandbox that those shows play in is just one that I love, one that I want to play in and expand on, and help continue to demonstrate that genre shows are (or can be) awesome, transformative pieces of art, not just some semi-obscure show about fighting monsters.

To do all that, however, I’d really appreciate your advice, and if you think of others who should weigh in, I’d be thrilled to hear from them as well.

Thanks!

@mittensmorgul @occamshipper @tinkdw @dimples-of-discontent @drsilverfish

P.S: I saw this GIF, or a picture of it, before I knew it was from SPN. When I saw it in an episode, I was just like, “?!”. (Oh, the things I’d seen from SPN before realizing it, or all the scenes I could recognize/quote that I’d maybe seen clips of at most, because I’d seen GIFs and screencaps so many times--that show took over my life before I ever started watching it). Anyway, as much as I truly love storytelling and I want to do it for my life because I love it and because I want to inspire hope in people through art, I’ll leave with this:

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Misha Collins is manipulating the LGBT for his own gain.

With the amount of trouble that Misha Collins has caused for the leads and the studio, it is baffling how anyone could still be a fan of his. Here is part of a conversation I had with a doll face. This is what she had to say about his fans.

''Willful blindness. She [the fan we were discussing who seems to have seen the error of the minion's ways] wants to believe the best in a person she has chosen to admire. On the very, very surface, misha doesn't seem like a bad person and people get sucked in, most choose not to look deeper because they get comfortable with where they are and what they believe in and they decide that the person they've chosen to believe in can do no wrong. In a twisted kind of way, it's like the faith that a child has in a parent. Some children never grow out of believing that their parent is infallible. Some people get drawn in by the hellers and never come back out. It sucks, and it makes people rabid, but that's the kind of bullshit that people like misha rely on to gain profit.''

She wrote this very well. I have noticed, that the hellers have a tier system. Right at the apex of the pyramid, is Misha of course, and below him you have influencers like @misharius, a volatile heller with a notorious reputation. She is the one who told Jared at Jaxcon, that she has more memes of Jensen and Misha than on Jared. She uses the AKF tag for her destiel stuff.

She was one of the liars who were implicated in the Travis Aaron Wade case. She accused Jensen of Islamophobia. And she is a close friend of Briana Buckmaster, resident leech. And she has fangirls of her own. People like her force fans to enter the fandom or start watching the show, through the destiel door. So they see everything through the destiel lens.

Because she may be implicated in court case involving Travis Aaron Wade and I think she might be problematic, I suggest that you block her. Believe me, you don't want to get involved in a person like this. She is a nasty piece of work.

Most of the people, below the influencers on the hierarchy, are children. So the analogy that doll face used about their affection being child like and naïve because they don't know any better actually makes a lot of sense. That means that the majority of the people in creepy uncle Misha's fanbase are children. And he is using sex, in the form of destiel to attract and keep their attention. How does that not make you feel weird.

Then there are people whom Misha has convinced that the pursuit of destiel is an LGBT pursuit. And destiel's failure in canon will be a failure for the LGBT. I did a post like this previously where I examined the kind of words that he uses to make it look like destiel is a sexuality. That is why lesbians are shipping destiel. Slash fiction is one of the subjects I enthusiastically delve into and I said, time and again, that it is an intimate straight and bi female sexual expression platform revolving around male subjects that the writers and readers are attracted to. So I found it baffling that lesbians were writing slash fiction rather than femmeslash.

Destiel doesn't seem to have a small odd fraction of lesbian writers. No, that section appears large and militant, and it goes back to Misha turning the pursuit of destiel into an LGBT pursuit. So they are emotionally governed by the love the ship, but socially governed by what the failure of canon would mean for them. So how nasty Misha is. I think that @misharius might be lesbian too. So is intelligentshipper. They have no emotional or sexual stake in destiel. They are pushing for it because of what it might mean to them. So essentially, Misha is using the LGBT in militant mode to keep himself in the game, instead of out on the streets where he belongs.

The thing is that the laws of physics oddly, come into play here. For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Every time the LGBT wages a battle against the leads and the studio, in the name of their ''cause'' aka destiel, it results in casual and neutral viewers of the show forming opinions regarding the group.

If those viewers are LGBT themselves, [and I am guessing that they are older than millenials] they feel embarrassed because Misha's group is abrasive and shows the LGBT as an entitled group of people. Gen X people are not militant bullies, generally speaking, gay or straight.

If they are non-LGBT viewers, depending on who they are, this encounter with the LGBT will color their view of this group of people whom they might actually not have any previous contact with or have any opinion of to start with.

Misha Collins is creating conflict where there isn't one, simply so that the CW will never even fathom firing him. He literally made up a problem that was not there. He did the exact same thing with the misogyny allegations that he made against SPN. He should have been fired for that but inexplicably wasn't. He basically rallied a bunch of millennial feminists to fight a problem that was not there. SPN was never a perfect show, and it shouldn't be because, after all, it is a human endeavor and is therefore bound to be flawed. But it was never really misogynistic.

Misha Collins is a selfish virus that feeds off others and cant survive on its own merit and grit. Therefore it needs to latch onto a host like Jensen and recently Danneel. On his own, Misha is not worth looking at and therefore drags Jensen into his mess. That is why he tweets so much and tweets various big names in the world. To give off the impression that he is a somebody like them. Friendly reminder to block @misharius. I have a feeling you don't want to deal with this person.

Excuse the obvious typos.

#misha#jensen ackles#destiel#cockles#jenmish#jensen and misha#deancas#casdean#dean x castiel#castiel#cas#bi dean#dean is bi#dean and cas#jenmisheel#dean winchester#destiel headcanon#jdvm#misha collins#sam winchester#sam and dean#jensen and jared#wincest#supernatural#jared padalecki#padackles#performing dean#sabriel#sammy winchester#j2

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

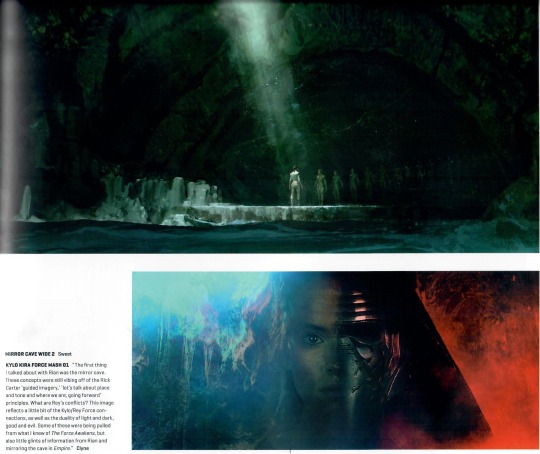

into the mirror cave

“The first thing I talked about with Rian was the mirror cave . . . What are Rey’s conflicts? This image reflects a little bit of the Kylo/Rey Force connections, as well as the duality of light and dark, good and evil. Some of these were being pulled from what I knew of The Force Awakens, but also little glints of information from Rian and mirroring the cave in Empire.” — James Clyne, VFX art director, The Art of Star Wars: The Last Jedi

“The idea is this island has incredible light and the first Jedi temple up top, and then it has an incredible darkness that’s balanced down underneath in the cave . . . In this search for identity, which is her whole thing, she finds all these various versions of ‘Who am I’ going off into infinity, all the possibilities of her. She comes to the end, looking for identity from somebody, looking for an answer, and it’s just her.” — Rian Johnson (x)

“The idea that if there’s a Jedi Temple up top, the light, it has to be balanced by a place of great darkness. We’re drawing a very obvious connection to Luke’s training and to Dagobah here, obviously. And so the idea was if the up top is the light, down underneath is the darkness. And she descends down into there and has to see, just like Luke did in the cave, her greatest fear. And her greatest fear is [that], in the search for identity, she has nobody but herself to rely on.” — Rian Johnson (x)

Some (long, rambling) thoughts on the mirror cave sequence below the cut.

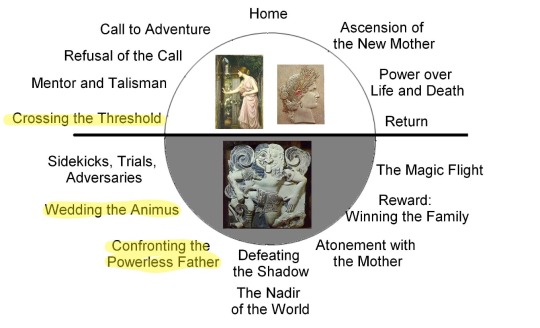

Rian certainly took a page from the heroine’s journey and mined some Carl Jung here. In this post I’ll discuss the mirror cave and hut scenes and how they trace the “crossing the threshold” and “wedding the animus” steps. In a future post I’ll discuss Rey’s confrontation with Luke as the “confronting the powerless father [figure]” step.

crossing the threshold: descent to “a dark place”

“There's something else beneath the island … A dark place.”

“You went straight to the dark.”

“That place was trying to show me something.”

For an excellent read on the heroine’s descent, see “The Descent: the Heroine’s Journey in The Force Awakens” and “Bride of the Monstrous: Meeting the Other in the Force Awakens” by @ashesforfoxes.

the heroine’s journey and the animus figure

A quick summary of some relevant Jungian concepts follows.

While the male hero goes on an active quest as a rite of passage (involving some physical feat like slaying the monster), the heroine goes on a more inward-focused quest (reconciling the monster within). The heroine’s journey involves an awakening within herself, by descending to a place where she can liberate her inner goddess.

In The Feminine in Fairy Tales, Jungian scholar Marie-Louise von Franz reminds us that this journey within is fundamental to the process of the heroine’s individuation, that it is “a time of initiation and incubation when a deep inner split is cured” by descending into the unconscious.

In The Heroine’s Journey, Maureen Murdock describes this descent as a “journey to our depths” that “invariably strengthens a woman and clarifies her sense of self” because it is a process of “looking for the lost pieces of myself” or seeking to complete oneself. As Murdock writes:

Persephone is pulled out of the innocence (unconsciousness) of everyday life into a deeper consciousness of self by Hades. She is initiated into the sexual mysteries … She becomes Queen of the Underworld.

Similarly, Rey is compelled to descend to that dark place underneath the island where she is pulled into a “deeper consciousness of self” mediated by her Force bond with Kylo. “That place was trying to show me something.” Note, “dark” here is not “evil” but it can show us something about ourselves (for instance, our greatest fears) as it represents the unconscious part of our psyche.

Persephone’s descent into the underworld is when she faces the unknown and matures. She had to leave her family and the familiar, namely the world above ruled by her mother Demeter in which she was kept in an infantile state of girlhood. The world below with Hades is where she accesses what Jungians call the animus and actualizes her selfhood as a woman.

So what is this animus? The anima and animus are “soul-image” archetypes projected onto a person typically of the opposite sex. The animus represents the masculine aspects of the female psyche. As von Franz tells us in The Feminine in Fairy Tales, the animus “has to do with ideas and concepts” and in fiction is typically represented by a man. In her essay “The Process of Individuation” in the Jung anthology Man and his Symbols, von Franz notes:

A vast number of myths and fairy tales tell of a prince, turned by witchcraft into a wild animal or monster, who is redeemed by the love of a girl—a process symbolizing the manner in which the animus becomes conscious. ... Very often the heroine is not allowed to ask questions about her mysterious, unknown lover and husband; or she meets him only in the dark and may never look at him. The implication is that, by blindly trusting and loving him, she will be able to redeem her bridegroom. But this never succeeds. She always breaks her promise and finally finds her lover again only after a long, difficult quest and much suffering.

The parallel in life is that the conscious attention a woman has to give to her animus problem takes much time and involves a lot of suffering. But if she realizes who and what her animus is and what he does to her, and if she faces these realities instead of allowing herself to be possessed, her animus can turn into an invaluable inner companion who endows her with the masculine qualities of initiative, courage, objectivity, and spiritual wisdom.

The animus, just like the anima, exhibits four stages of development. He first appears as a personification of mere physical power--for instance, as an athletic champion or “muscle man.” In the next stage he possesses initiative and the capacity for planned action. In the third phase, the animus becomes the “word,” often appearing as a professor or clergyman. Finally, in his fourth manifestation, the animus is the incarnation of meaning. On this highest level he becomes (like the anima) a mediator of the religious experience whereby life acquires new meaning. He gives the woman spiritual firmness, an invisible inner support that compensates for her outer softness. The animus in his most developed form sometimes connects the woman’s mind with the spiritual evolution of her age, and can thereby make her even more receptive than a man to new creative ideas. It is for this reason that in earlier times women were used by many nations as diviners and seers. The creative boldness of their positive animus at times expresses thoughts and ideas that stimulate men to new enterprises.

Fairy tales from the female individuation perspective are all about wedding the animus or reconciling with the monster, which is deeply identified with the heroine’s innermost self. This part of the journey is necessary to heal that inner psychic split, to become whole. Reconciling her animus in a positive way allows the heroine to access new ideas and concepts and achieve her creative potential. Rey must acknowledge and integrate her positive animus to “become what you were meant to be” (more on the positive vs negative animus below).

(Edit: See also this wonderful meta by @skysilencer elaborating on the anima and animus as parts of the psyche.)

rey’s mirror cave journey and kylo ren as her animus

Following the beats of the heroine’s journey and Jungian concepts, Rian has given us what many of us have predicted all along: Rey joining with Kylo Ren as her animus on her journey of self-discovery.

Rey descends through a black hole that pulls her into the ocean depths beneath the island. When she emerges at the mouth of the mirror cave, her hair is undone. This is the first step of her growth from girlhood to womanhood and the liberation of that inner goddess.

Rey kept her hair tightly coiled in those signature three buns all her life on Jakku because she clung to the infantile hope that her parents would return and recognize her. We now know that this hope was a fiction she fabricated to give herself a reason to live. We tell ourselves stories in order to live. Rey imposed her own rosy narrative on a harsh reality in order to survive. “Child . . . you already know the truth.” Indeed, as Maz correctly intuited, Rey already knew the truth: her parents were nobody and they were never going to come back for her.

Rey’s loosened hair represents letting go of that past and uncoiling that fictional narrative that was holding her back.

The new undone look also signifies a sexual awakening.

And who should be there, listening patiently, as a companion to Rey’s awakening? Rey narrates her mirror cave journey to none other than Kylo Ren, who is with her on that journey as her animus.

Recall, the animus first appears as “mere physical power” but in a higher form gives the woman “an invisible inner support” as mediator of a meaningful spiritual experience. At first, Kylo appeared to Rey as a creature in a mask, a manifestation of mere physical power. Through their Force bond, Kylo certainly manifests as a “muscle man” particularly when he refuses to throw on something to cover those gleaming pecs. Later, he becomes a source of spiritual support when he assures Rey “you’re not alone” after she confides to him she had never felt so alone as in that cave where she sought answers.

Also, recall, the animus has to do with ideas and concepts. Kylo represents the idea of “let the past die” on Rey’s path to self-actualization. Rey needs to hear this in order to move on from her disappointment at being so casually tossed aside by her parents. While Rey clings to the past (her parents, Luke the legend who she says the galaxy needs, the myth of the Jedi and the Jedi “page-turners” she takes on the Falcon), Kylo wants to throw it all away. Kylo wants to tear down the curtains, just as those red velvet curtains in Snoke’s throne room burned away to reveal the black void of space around them. Kylo wants to live in that black void of cold reality where Luke and the Jedi are demythologized and deconstructed, where he can see clearly Rey’s parents for who they were as opposed to the childish way Rey put a curtain over the truth with her own make-believe tale (“they’ll be back … one day”). Rey needs a cold splash of that demythologization to grow up.

As Rian Johnson tells us in The Art of Star Wars: The Last Jedi, there’s “a sin in venerating the past so much that you’re enslaved to it.” Yet the idea is not so simple, as Rian also acknowledges the need to reconnect with the past (and implicitly the need to re-construct myths by which to live):

If you think you are throwing away the past, you are fooling yourself. The only way to go forward is to embrace the past, figure out what is good and what is not good about it. But it’s never going to not be a part of who we all are.

We become “enslaved” if we go too far in either direction, whether venerating the past too much or wanting so badly to desecrate and “kill” the past. The extreme and destructive way in which Kylo seeks to “kill it” represents the negative animus. That side is, paradoxically, too emotionally tied to the past (and fixated on perceived past wrongs), unwilling to simply let go of the anger and resentment. To integrate her positive animus, Rey needs to acknowledge and learn from the past by looking at it in an objective way, which requires distancing herself instead of letting the past rule her emotions. Both Rey and Kylo need to embrace the past and the fact that it is part of who they are, in order to move forward.

Let’s distinguish the positive animus from the negative animus, which can be identified with the heroine’s shadow. The negative animus often appears as a sort of “death-demon” or murderer (“murderous snake” for instance) and “personifies all those semiconscious, cold, destructive reflections that invade a woman in the small hours” according to von Franz. Bluebeard would be an example of the negative animus: a seducer who is ultimately destructive and must be overcome. The negative animus can be that inner critic reinforcing feelings of worthlessness.

In what ways is Kylo a negative or positive animus?

Negative animus: Kylo who embraces the monster role (“Yes, I am”). Kylo who says “you have no place in this story . . . you’re nothing” and resents the past. Kylo who is filled with so much self-loathing he stabs in the heart the man whose heart he has too much of (“You have too much of your father's heart in you, young Solo”) and wants to blast out of the sky the “piece of junk” in which he was conceived. Kylo who rages against the galaxy, who wants to impose a new order on the galaxy.

Positive animus: Kylo who says, “But not to me. Join me. Please.” Kylo who responds to “Ben” and who Rey sees turning in the future (“If I go to him, Ben Solo will turn”). Kylo who desperately needs to make peace with the past. Kylo who tells Rey, “You’re not alone.” Kylo who fought side by side with Rey, perfectly in sync. Kylo who we are rooting for to ultimately make peace with the galaxy.

Kylo has the potential to be Rey’s positive animus, but at the end of the film she cannot reconcile with him yet because he has not yet transformed from the murderous negative animus to Rey’s positive animus.

rey’s search for identity

“Who are you? … What’s special about you?”

Here, I digress a bit to discuss why Rey “nobody” is the perfect reveal and try to address some of the criticisms about the jarring sequence in the cave.

First, the way this sequence is filmed and narrated is superbly meta. Just as Rey is pulled out of her “everyday life” into another realm of consciousness, so are we as the audience pulled out of the immersive experience of the breakneck-paced dramatic narrative into a more self-reflective space. Some have criticized this moment as violating that rule of immersion, breaking the fourth wall and taking us out of the film. Reminiscent of Yayoi Kusama’s popular Infinity Mirrors exhibit, Rey’s mirror cave scenes evoke the experience of being in a modern art installation. You are part of those infinite possibilities. It is you, the audience, who create those infinite selves. This is entirely intentional and I believe indicative of Rian Johnson’s brand of auteurism: entirely self-aware and humbly transparent about his intentions. We are meant to reflect on our own assumptions about Rey. We are meant to question, does it really matter who her parents are? Why do we think it matters? For the fans who wanted her to be blood-related to a legacy Star Wars character: what does that say about you and your view of a character’s worth? your view of what builds character?

In The Art of Star Wars: The Last Jedi, Rian explains that he wanted to explore, “What do you keep from the past and what do you not? What is the value of the myths you grew up with? What is the value of throwing those away and doing something new and fresh?” In a very meta way, his treatment of Rey’s struggle with her past in The Last Jedi also led the fandom to question: What is the value of the mystery box?

So much criticism has been leveled about the “empty mystery box” and how anti-climactic it is to show us Rey’s own reflection at the end of the corridor of infinite selves after teasing us with those murky shadows behind the glass, as if mocking fans for their intense speculative interest in her parentage, which was arguably one of JJ’s deliberately constructed mystery boxes.

Did Rian totally deconstruct and wreck that box? Well, not exactly, because the point of the mystery box was never to yield a white rabbit like a simple magic track. From JJ’s TED talk:

The thing is that it represents infinite possibility. It represents hope. It represents potential. And what I love about this box, and what I realize I sort of do in whatever it is that I do, is I find myself drawn to infinite possibility, that sense of potential. And I realize that mystery is the catalyst for imagination. Now, it's not the most ground-breaking idea, but when I started to think that maybe there are times when mystery is more important than knowledge.

The mirror cave itself is a representation of the mystery box and Rey’s infinite potential. Rian, in a sense, preserves that mystery, that infinite possibility.

JJ goes on in his TED talk:

And then, finally, there's … the idea of the mystery box. Meaning, what you think you're getting, then what you're really getting. And it's true in so many movies and stories. Look at "E.T.," for example — “E.T." is this unbelievable movie about what? It's about an alien who meets a kid, right? Well, it's not. "E.T." is about divorce. "E.T." is about a heartbroken, divorce-crippled family, and ultimately, this kid who can't find his way … When you look at a movie like "Jaws," the scene that you expect … she's being eaten; there's a shark …The thing about "Jaws" is, it's really about a guy who is sort of dealing with his place in the world — with his masculinity, with his family, how he's going to, you know, make it work in this new town.

So many thought Rey was Luke 2.0 and that this story was about her going from nobody to somebody by virtue of discovering she belongs to an elite bloodline. So many thought The Last Jedi would be about passing the torch to the next Jedi. Well, it’s not really about the next Skywalker or the next Jedi. This story is about a girl finding her place in the world, who can’t find her way because she kept telling herself a lie about her past that trapped herself in her own mystery box, a box of her own making that allowed her to live with hope and at the same time limited her growth and kept her all alone. She told herself “they’ll be back … one day” when she knew her parents were never coming back. This story is about a girl who feels so alone. She meets a boy who feels this too: “You’re so lonely.” When Rey and Kylo are Force bonding together, their scenes are marked by silence, stripped bare of the noise and the sturm und drang of an epic-scale John Williams score, stripped down to the intimate-scale essence of their story: “You’re not alone.” “Neither are you.”

What Rian gives us is what we were really going to get all along: the revelation that the real substance is not in the box’s contents (the answer to the mystery of Rey’s parentage) but in that negative space around the mystery box, which is about two kids dealing with their loneliness.

So what do we make of Rey gazing at her own reflection, disappointed and alone?

Some have criticized the mirror cave sequence as an indulgent interlude emblematic of the vanity endemic to today’s narcissistic navel-gazing “me” generation—both the vanity of the auteur as well as the vanity of the film’s populist self-empowerment message. The mirror cave with its echo chamber and mirrors do bring to mind Echo and Narcissus. When Rey snaps her fingers, she hears nothing but her own sound, infinitely echoed. When Rey looks into the mirrors, she sees nothing but herself, infinitely reflected. (Edit: To be clear, I’m not agreeing with the “me” generation assessment. Also, it’s true that there are covert narcissists who feel vulnerable and neglected and that a deep-seated sense of insecurity or lack of self-esteem is at the root of narcissism. Rey and Kylo both exhibit some of this insecurity.)

Yet Rey is the opposite of a Narcissus. She doesn’t worship her own image or hold a grandiose view of herself (or lack empathy for others for that matter). Rather, she must learn to love herself instead of seeking love and validation from stand-in parental figures. As Kylo says, “Your parents threw you away like garbage. But you can’t stop needing them. It’s your greatest weakness. Looking for them everywhere, in Han Solo, now in Skywalker.” Here, unlike Narcissus who needed to detach himself from excessive love for his own image, Rey must come to embrace herself as worthy and self-sufficient. (Edit: Also, here, Rey is horrified rather than delighted to see her own reflections. See also Reyflections of Existential Horror from @and-then-bam-cassiopeia.)

As Rian tells us, her greatest fear is that she has nobody but herself to rely on. She must face that fear head on and realize she is enough, that all she needs is right in front of her nose (as Yoda might say).

She also comes to realize: “You’re not alone.”

wedding the animus: “when we touched hands”

“I thought I’d find answers here. I was wrong.” Yet the mirror cave does show Rey something vital to her search for identity: her own duality. At the end of that seemingly infinite hall of mirrors, Rey sees two shadowy figures walking forward behind the glass who then merge into one to form her own reflection. The shadows evoke a masculine figure and a feminine figure.

The “Kylo Kira Force Mash” concept art and its placement together with the mirror cave concept art on the same page in The Art of Star Wars: The Last Jedi suggest to me that the two shadows merging into one and emerging as Rey’s reflection is supposed to represent both (1) the duality of masculine and feminine within each of us, in particular Kylo and Rey wedding into one as Rey assimilates Kylo as her animus, and (2) the duality of light and dark within each of us.

Recall, the idea of wedding the animus is that we need to reconcile and integrate both sides (both masculine and feminine, both light and dark) to become whole.

The mirror cave scenes are followed by a “wedding the animus” scene. After Rey narrates her mirror cave journey to Kylo, sitting with him in the hut through their Force bond, she proceeds to engage in perhaps the most intimate act we have ever seen in Star Wars (or Disney for that matter). She extends her hand, and the camera zooms obscenely close to Rey and Kylo’s bare fingers making contact.

In this moment, as she gasps, she sees a future with Ben. She sees him turning against Snoke. (Yes, he does turn against Snoke, but her vision is incomplete as he doesn’t turn against the First Order yet.) Likewise, he sees a future with her: “When the moment comes, you’ll be the one to turn. You’ll stand with me.” (I do think that in Episode IX we will see Rey standing with Kylo and turning to help him in some way, but Kylo’s vision is also incomplete in that she rejects his plea to join him in the throne room and does not turn against the Resistance.)

Yes, this moment is more intimate than a simple kiss or other physical act of intimacy, because Rey and Kylo are envisioning future lives together, standing side by side. Wedded to each other by the Force. The Force theme begins to play at this moment, as if underscoring the divine inevitability of this union.

Why does Rey fail to see clearly that Kylo would not yet turn in the throne room? “Ben, when we touched hands, I saw your future. Just the shape of it, but solid and clear.” Here I’m reminded of those shadowy figures again, and these verses from Corinthians 13:11 and 13:12 much referenced in literature and film:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

Rey is somewhat naive, like a child. In the mirror cave when she touches the glassy surface and in the hut when she touches Kylo’s hand, she sees through a glass, darkly. Rey’s knowledge of herself and her past is imperfect. Rey’s knowledge of Ben and the future is imperfect. Her vision is obscured by her naiveté and hope, by her optimistic insistence on clinging to rose-colored glasses and red curtains.

Chapter 13 in Corinthians is about love (sometimes translated to charity). What is a theme throughout Star Wars? Compassion. As Joseph Campbell points out, this means to suffer together, to feel someone else’s suffering as our own and wish to relieve that suffering.

Kylo began to feel compassion for Rey in the interrogation room when he discovered her loneliness. “You’re not alone.” Her suffering at Snoke’s hands likely contributed to his resolve to conceal his true thoughts from his master and slay Snoke at the right moment. When Rey is cut on the shoulder by a Praetorian Guard, Kylo glances towards her anxiously, further evidencing his compassion for her. However, he lacks compassion for her concern with her friends and the plight of the Resistance. He is still thinking in terms of “you’ll stand with me” instead of “we will stand together” working towards a shared goal.

Rey begins to feel compassion for Ben Solo through their Force bond, when she sees that fateful temple-burning night from Kylo’s point of view and learns that Luke lied about how he behaved. She also feels Ben’s loneliness. “Neither are you.” She extends her hand out of compassion. However, she didn’t ship herself to the Supremacy for Ben Solo, she went there to save her friends, and he understands that when she turns to the window port and demands, “Order them to stop firing!” Recall Rey’s reasons to Luke before flying off on the Falcon:

If he were turned from the dark side, that could shift the tide. This could be how we win.

Rey too is thinking about her own agenda, as opposed to what Kylo wants to accomplish: “We can rule together and bring a new order to the galaxy.” Kylo’s proposal to Rey, which involved a future together, is met with what he might have perceived to be an attempt on his life, though Rey’s grab for the lightsaber might simply have been her way of sending the message: you are not worthy of this yet. Neither of them are truly able to see from each other’s point of view; each has more to grow to reach that common ground and to truly love and suffer together.

At the end of the film, Kylo remains a negative animus who has not yet fully processed and embraced the past as part of who he is, full of murderous rage (“blow that piece of junk out of the sky!” and “more! more!”). His rage masks his true misery and self-loathing, which is pitifully obvious from the way he looks at Rey through their Force bond at the very end of the film, then slowly closes his fingers around the projected gold dice as he realizes despite his ascension to Supreme Leader he truly holds on to nothing. He's not angry and resentful in that moment. He's heartbroken and sad.

But … Ben Solo will turn. The structure of the heroine’s journey mandates that Rey will somehow reconcile with her positive animus.

#tlj spoilers#mirror cave#the art of star wars: the last jedi#my scans#tlj meta#carl jung#marie-louise von franz#heroine's journey#heroine's descent#rey x kylo ren#kylo ren as animus#negative animus#positive animus#wedding the animus#tlj art book#my meta

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Emo Music, not Emo Musician

Should emo songs be dismissed simply because a band member has been accused of sexual misconduct or another moral flaw? The question of separating art from the artist is especially relevant for the emo genre because emo lyrics are known for putting the musician’s personal vulnerabilities out on display. The art is not only expected to be directly related to the creator, but there are also those who argue that it is insincere. On the other hand, emo is a genre that is defined by its audience of angsty teenagers. Art should be judged by the effect that it has on its audience, and not by the intentions or morality of the artist, just as children should be judged separately from their parents.

In Ghost World, Enid presents an old poster in her remedial art class. The poster is an advertisement for Coon Chicken Inn, a restaurant with a rather racist theme. There are multiple possible intentions that I could see Enid having. One of the possibilities is the one that Enid tells her class, which is that the poster is a found art commentary about how racism is simply “white-washed over in our culture” (Ghost World). As interesting as the concept of racism lurking just beneath a happy facade is, Enid’s more likely intention was to simply have less work to do for her art class, because she is shown to be constantly annoyed by her classmates and the teacher, especially when she sees minimal-effort found-art hangers being praised over her sketchbook. Another possibility is that Enid just wants to get on her classmate’s nerves due to jealousy, and she uses similar language in her presentation of the poster.

Source

The true intention is irrelevant, however. At the art gallery, the audience settles for being offended, and simply demands that the poster is removed. Enid’s teacher pleads for the artist to have an opportunity to convey their intentions, but the viewers refuse to ponder the way that racism is hidden just out of sight, and instead force the art out of sight. Enid’s piece ends up being a failure. Her expressed intention is a flop, because the attendees of the art gallery do not examine the deeper meaning behind the poster. She is forced to fail the class, so turning in minimal-effort found art to get a good grade like her classmate did does not work out. The Coon Chicken Inn advertisement ends up being so offensive to the audience that it fails as a piece of art to convince the audience of re-examining racism or even of letting her pass art class.

Just because in Enid’s case the art was judged without the original intentions in mind, should emo songs also be interpreted the same way? Ghost World is certainly a work of fiction, and the poster episode could very well be a critique of judging creations and their inspirations separately. At the same time, the movie first seems to criticize the way that a stack of hangers can be explained to be commentary on abortion, and the art gallery scene may simply be a continuation of the analysis on the art teacher caring more about explanations than the way that the art actually carries the message across.

Source

Emo music, which is all about the audience relating to the emotions of the singer, can have a positive effect on the listeners even if that musician is a wretched human being. XXXTentacion’s death will never impact his lyrics, but maybe abusing his former girlfriend Geneva Ayala did. The allegations of verbal and physical abuse add to his confirmed history of violence and crime. I will admit that I am not a fan of X’s moral character, but I also think some of his songs are kind of catchy. Does that make me a wife beater? If so, our culture has a few too many sleeveless shirts given the success of the rapper’s albums.

X’s albums are not just a monetary success, because they provide awareness for issues that are not normally discussed. His album 17 is full of mental health issues, bringing awareness to suicide and depression. Even though XXXTentacion has a rough history, he is unapologetic for his violence. He does not inspire others to behave like he did through his music, however. “Jocelyn Flores,” a song from 17, clearly demonstrates the way that X sings about sensitive issues without adding ulterior motives. He expresses suicidal thoughts, and he is praised by his audience for bringing mental health issues under the spotlight. The song itself is not a testament to domestic violence. “Jocelyn Flores” inspires discussion of depression, and it should be judged for the way that its audience is forced to ponder the implications of suicide, not for the alleged actions of X.

youtube

In a way, Enid and X are direct opposites. Enid has innocent intentions but her art is thrown out due to its offensive nature, while XXXTentacion has a criminal past but his music is praised for what it inspires. The audience is the ultimate judge of art. What emo music evokes in the listener is the measure by which it should be evaluated instead of the musician’s personal life.

Quoted Sources:

Ghost World. Directed by Terry Zwigoff, performances by Thora Birch, Scarlett

Johansson, and Steve Buscemi, United Artists, 2001.

0 notes

Audio

[edited transcript]

Part I: Introduction

Today, I’ll take a slightly different approach than I’ve taken in previous episodes. Normally, I take a topic from philosophy, and a single TV show to study in conversation with that philosophical question. In this case, my question itself is more connected to television, and I’m going to be using several TV examples to explore the question.

My question for today is, What is television? Today more than ever, that question is getting harder and harder to answer. Just think about all the new ways of watching TV: streaming, Netflix, cable, On Demand. And there are new kinds of programming. Creators are experimenting with lengths, narrative structures, nonfiction versus fiction, timelines, sequels, prequels—and that’s not even taking into account variations in broadcasting policy and regulations from country to country, and network to network. On the audience side, television can occupy a variety of different roles in different people’s lives. These are just some of the reasons why it’s so hard to answer the question, What is television?

This points to a broader discussion about what it means to define something, in a philosophical sense. That’s how I’m going to start this episode: a brief history of how philosophers have thought about definitions in the past, the kinds of definition that are useful for philosophical discussion, and what those definitions need to accomplish in the context of philosophical discussion. I’m going to give a brief overview of definitions from a philosophical standpoint. Then, I’m going to look at a handful of TV theorists who have either attempted to define television for themselves, or have given arguments for why we can’t define it. Finally, I’ll propose a way that four very different programs can all be grouped under the heading “television.” I’m going to be using a variation on family resemblance theory to do that. I’ll explain family resemblance theory in a little bit, but this is a controversial alternative to giving a traditional definition of a term.

Part II: Oxford English Dictionary

Before we get into some more heavy duty, philosophical definitions, I thought I’d start with the Oxford English Dictionary definition of television. The OED defines television as: “(1.a.) A system used for transmitting and viewing images and (typically) sound; the action of transmitting and viewing images using such a system…esp. such a system used for the organized broadcast of professionally produced shows and programs. (b.) The activity or occupation of broadcasting or transmitting on television; the television system or service as a whole; television as a medium of communication or as a form of art or entertainment. (c.) That which is broadcast or transmitted by television; the content of television programs.”

The first thing I noticed about this definition is the emphasis on broadcast, which modern television has certainly expanded beyond. But that is where television history is rooted: it evolved from radio into a series of broadcast networks, so I think that’s part of why broadcast plays such a prominent role in the OED definition. Along the same lines, television is defined first with reference to the physical TV system itself. That’s definition 1.a.: “a system used for transmitting”… et cetera [emphasis mine]. My question here is, in philosophy parlance, what kind of definition did I just read in the Oxford English Dictionary? Are there other kinds of definitions that are better suited to the task of discussing television, and the task of giving a philosophically-satisfying definition of television?

Part III: Philosophical Definitions

Let’s get into philosophical definitions. To work through this section, I’m mainly going to be referring to a piece from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, by Anil Gupta. I’ve cited from the Stanford Encyclopedia in previous episodes, and it’s a really great resource if you want a brief, but fairly detailed overview of any kind of general philosophical topic. Gupta notes that he is not covering every kind of definition, and of the kinds he covers, I will only address a few.

The first point Gupta makes is that some debates about definitions “can be settled by making requisite distinctions, for definitions are not all of one kind: definitions serve a variety of functions, and their general character varies with function. Some other debates, however, are not so easily settled, as they involve contentious philosophical ideas such as essence, concept, and meaning.” Later on, Gupta says, “The different definitions can perhaps only be subsumed under the Aristotelian formula that a definition gives the essence of a thing. But this only highlights the fact that ‘to give the essence of a thing’ is not a unitary kind of activity.” In other words, there are different kinds of definitions that are suited to different purposes. But if all definitions aim to give the “essence” of a thing, that seems to just push the question further back. What does it mean to describe an essence? Even if we know what we mean by essence, is that something that can be satisfactorily described in a single definition? Keep that question in mind as we move along.

One kind of definition that this article discusses is a stipulative definition, which “imparts a meaning to the defined term, and involves no commitment that the assigned meaning agrees with prior uses (if any) of the term.” A stipulative definition is set out for the purposes of the given discussion. As far as I can tell, a stipulative definition wouldn’t seem to capture essence in the fullest sense, because a stipulative definition is not committed to agreeing with preexisting uses of the term it defines. A definition that captures the essence, whatever that means, should reflect how that essence is understood in earlier uses of the term. Say that you stipulatively define “dogs” as “things with four legs” for the sake of a discussion. Someone could come up with counterexamples, like a three-legged dog, and in that sense they could argue that you’re not capturing the essence of dog (which includes three-legged dogs) in your stipulative definition. However, I think as long as you’re aware that your definition is a stipulative one, and you don’t attempt to use it as you would a comprehensive, essence-describing definition, then you should be okay. To that end, Gupta discusses some of the criteria for stipulative definitions, one of which is called the “conservativeness criterion.” The conservativeness criterion says that “a stipulative definition should not enable us to establish essentially new claims.” The implications of a stipulative definition should be restricted to the confines of the discussion in which it’s put forth. Since stipulative definitions don’t have to agree with prior uses of a term, this means that stipulative definitions can’t be used to make new arguments about the term, as that term was used in prior discussions. That’s a brief summary of how stipulative definitions work.

The next kind of definition is descriptive. “Descriptive definitions, like stipulative ones, spell out meaning, but they also aim to be adequate to existing usage.” In this case, if a descriptive definition doesn’t fit existing usage, it’s unsatisfactory. Think of it as an additional requirement added on to a stipulative definition. Your descriptive definition has to agree with how the term was used and understood, before you put forward your own definition. I think descriptive definitions sound like they come closer to capturing the essence, since the requirements placed on them are more stringent, and descriptive definitions are wedded to preexisting uses of the terms that they define. Gupta’s article lists three grades of descriptive adequacy for a descriptive definition. These are three ways you can judge a descriptive definition. A descriptive definition is“extensionally adequate iff there are no actual counterexamples to it”; it’s “intensionally adequate iff there are no possible counterexamples to it”; and the definition is “sense adequate (or analytic) iff it endows the defined term with the right sense. (The last grade of adequacy itself subdivides into different notions, for ‘sense’ can be spelled out in several different ways.)” [author’s emphasis]. Sense adequacy seems like a murky criterion. I think it’s similar to what it means to give the essence of something. What it means to endow the term with the right sense could be up for debate, and I think that’s why Gupta notes that there are different ways of understanding what it means to give the sense of a term, depending on the context in which you’re defining it. But I think the first two grades of descriptive adequacy—extensional adequacy and intensional adequacy—seem fairly straightforward. If you want to prove that a descriptive definition is extensionally inadequate, you supply a real-world counterexample. To return to dogs, to prove my stipulative definition extensionally inadequate, you could refer to an existing three-legged dog. To prove a descriptive definition is intensionally inadequate, you need to provide a logically-possible counterexample. The counterexample doesn’t need to be something that actually exists in the real world (because that would prove extensional inadequacy); it can be something that’s merely within the realm of possibility that would disprove the definition.

The final kind of definition we’ll discuss is an ostensive definition, which “typically depend[s] on context and on experience.” Gupta says, “We can think of experience as presenting the subject with a restricted portion of the world. This portion can serve as a point of evaluation for the expressions in an ostensive definition.” I think most ostensive definitions come in the form of “let x be this thing.” So, if we were talking about dogs, to paraphrase Gupta, I would say, “let Dug be this dog,” and I would be pointing to my pug, Dug. Ostensive definitions can be a way for new terms to enter the lexicon. When you see something new and assign it a name, you are giving it an ostensive definition by saying, let’s call this thing x. If that definition and name catches on, then we have a new term in our language. The Gupta article notes that Bertrand Russell and some other philosophers have proposed that ostensive definitions are “the source of all primitive concepts,” and that we built our language by giving names and ostensive definitions to the things we encountered. Presumably, whoever named television “television” could be thought of as having given an ostensive definition to this new thing, television, based on what they experienced in their first encounter with this new technology. But again, this ostensive definition doesn’t seem like the most useful definition for understanding what television is. We’re past the point of encountering, identifying, and naming TV for the first time, and we also want our definition to be agreeable with prior uses of the term. Ostensive definitions make no attempt to do that.