#like the old ones with the illustrations and about the greek gods and poems and such

Text

My friends finally bullied me into watching Sandman

#the sandman#the corinthian#old art redraw#fanart lol#fanart#art#fan art#ghostlysdoodles#sandman fanart#the corinthian fanart#redraw#uh yeah#i wanted to try it out in the style of the books id read when i was little from my nana#like the old ones with the illustrations and about the greek gods and poems and such#that style#i failed but i tried and it was fun

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

While checking around for my “Roman gods are not Greek gods” posts, I found back this tripartition of mythology, which is actually a fact that everybody should kno about if they want to dabble in Greco-Roman myths (especially Greek myths).

We know that, during Antiquity, the Romans and the Greeks thought that there wasn’t just one, but three different types of “theology” - three different views, perceptions and reception of the gods.

The first theology was the theology of the priests and of the state - aka, religion. The Greek gods as perceived and described by religion, as honored through rituals and festivals.

The second theology is the “mythic theology” - what we call “mythology today”. It is a set of legends, folktales and stories that are not part of religion, but rather used and carried by art - it is the gods are seen, perceived and described by the poets, by the epics, by the theater plays.

The third theology is the theology of the philosophers - who used the gods and their tales as images and allegories for various abstract or concrete topics. It is the gods as depictions and description of natural phenomenon, or the myths as a way to actualy exemplify a social fact or explain psychological workings.

For the classic Greeks and Romans, there was a clear divide between those three very different point of view of the gods. It was basically three different versions of the pantheon. This is notably why you will find texts noting that priests disliked and condemned the poets’ mythological works, due to them being blasphemous and making the gods too human when religion described them as perfect ; and it is also why the philosophers of old dissed on and rejected the literary works of mythology as nonsense only good to feed superstitions, because for them the gods weren’t characters or realities, but rather abstract concepts and rhetorical allegories.

This is something I feel needs to be reminded, because today these three different theologies have been mixed up into one big mess - as literary myths are placed one the same level as philosophical “myths” (actually texts taking the shape of myths), and both considered of outmost religious importance. When in fact, things were quite different...

EDIT: I was asked if there was a myth that could illustrate the three different theologies, and on the spot I would say “the affair between Aphrodite and Ares”.

This story originates from the “mythological theology”. It is primarily a story, and a good one. It is the story of a husband who discovers his wife is unfaithful and tries to get revenge, it is the story of an extra-marital affair gone wrong, it is typical set of divine shenanigans ending on a grotesque display of divine humiliation - it is an excellent narrative material for plays and poems (and the legend does originates from poems).

The story was also dearly beloved and reused by the “philosophical theology”, because the philosophers adored the idea of the love between Ares and Aphrodite - for them it was the perfect depiction of how the concepts of “love” and “war” , despite being seemingly opposite, attracted each other and were closely tied. For them, this story isn’t to be taken literaly as “a god cheated on another god”, but rather as “this is an allegory showing that love and war are two sides of the same coin, which is why Aphrodite falls for Ares despite being married to Hephaistos”. But for them the whole net part is just poetic nonsense invented to make people laugh ; or maybe they will reinvent them as a moral, cautionary tale that should be used to warn people of the dangers of unfaithfulness.

And then there’s the “religious theology”, the point of view of the priests - for whom such a story is mockery and sacrilege. You can imagine them saying: “You are making the gods look like fools! Gods don’t cheat on each other, gods don’t get captured in nets while butt-naked, gods don’t even sleep on beds - GODS DO NOT EVEN HAVE HUMAN FORMS IN THEIR NATURAL STATE - what the heck is this bullshit you’re saying, you’re just insulting the gods by turning them into lecherous humans and grotesque clowns for your vulgar story!” (This is a reconstitution and not the actual words of an Ancient Greek priest)

#greek gods#roman gods#greek mythology#greek religion#roman mythology#roman religion#ancient theology

618 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 days of devotion: Nymphai

Day 4: A favourite myth or myths of this deity

There are uncountable myths that concern the nymphs, and picking my favourite among them feels impossible. There’s the chase of Daphne, of course, the story of Echo, and arguably in some cases, Kirke. I do think one nymph stands out to me, and I’ll talk of her down below. TW: Mentions of abduction/allusions to r//pe.

Thetis, (unwilling) wife of Peleus and mother of Achilles. She was a nereid, daughter of Nereus, 'the old man of the sea.'

A reason why I gravitate towards her (other than for the fact that my wife worships her) are several things; 1) she’s mentioned in the oldest piece of western literature and my favourite epic poem, 2) her unwavering love for Achilles and 3) her grief at his fate and her loss of him. Nymphs frequently beget heroes in mythology, but they often do not (have to) fulfil the other societal pressures and expectations put on mortal women in their roles as wife and mother. They are seen to take care of infants - but they are usually not their own. Thetis is an exception. She is a mother, not just a progenitor. Another reason she stands out to me, is illustrated in this quote below,

“In the Iliad, such encounters [of nymph and mortal man] happen only to the Trojans and their allies and are absent from the genealogies given for the Achaians [Greeks]. Apparently, the motif of the mortal herdsman who is loved by a local nymph was at first confined to Asia Minor; Griffin suggests it is in origin a variation of the union of the Great Goddess with a mortal consort. Unions between nymphs and mortals, however, were not unknown to the Achaians, for Achilles was born of Peleus and the unwilling Nereid, Thetis.” - Greek nymphs, Myth, Cult, Lore by Jennifer Larson

Why is Thetis the exception to the rule? I have no idea. I’m fascinated by her.

Another reason why I love her, especially in the Iliad, is the distinction in relationships between mortals and gods, and mortals and nymphs. The nymphs in hymns and poetry were called “my dear nymphs”, standing much closer to mortals than the distant Olympian gods did. You do not see (there are exceptions, for example the goddess Aphrodite) where they are talked of lovingly and intimately. Here is a quote of the Iliad, in which Achilles talks of Thetis,

“Mother tells me, the immortal goddess Thetis with her glistening feet, the two fates bear me on to the day of death.”

Besides the inherent tragedy of Thetis having to tell Achilles his fate; he calls her by the familial title of mother, first. I don’t have a scholarly reason for liking this so much. It just makes my heart soft.

Thirdly, I also respect her for her willingness to fight a fate she did not want for herself. Gods and mortals alike cannot change “the will of Zeus” (fate), but she did give it her best shot when,

“Out of all the sea goddesses, he [Zeus] subjected me to a man, Aiakos’ son Peleus, and I endured the bed of a mortal man, though I was completely unwilling.” (Iliad, Homer)

She changed into varying (terrifying) shapes to loosen his hold on her, and eventually gave up, though not for lack of trying. She fits into one of the most common motifs in later myths throughout Europe of the ‘swan maiden’ here, where a man captures a bird maiden by stealing her coat of feathers while he watches her bathe. She struggles, fails to break free, and silently fulfils the duty of mother and wife, until she eventually regains possession of the coat and disappears, usually still periodically checking up on her children after. In Thetis’ case, she was a nereid, changing into sea animals. This fascinates me, because besides her being a mother of an Achaian hero, here too she is the exception, being one of only two figures* in ancient Greek mythology who bear a similar fate of forced marriage with a mortal man by holding her down as she struggles and then gives in (while later in folkloric tales about neraïdes, it is a much more common motif)**.

And lastly, a reason already listed above for adoring the myth of Thetis, is that when she couldn’t sway the end the Fates had in store for her son, Achilles, she tried to immortalise him in fire anyway (talked of in the Argonautica, by Apollonius of Rhodes). She failed, as none could sway the will of the Fates, but she attempted it anyway, just as much as she fought against Peleus’ grip.

She tried making Achilles immortal by placing him in the fire during the night (Achilles was a child, and Thetis still lived as Peleus’ wife with him) and anointed him with ambrosia during the day. The attempt fails when Peleus happens to see his son’s immersion in the flames, and gives out a terrible cry, whereupon Thetis throws the boy down, goes away herself, and does not return. Peleus was bound to find her and stop the process of immortalisation, as Achilles wasn’t destined to become a god. She tried her best, though. I have to give her that.

*The other example is of Aiakos, Peleus' father, funnily enough, with another nereid called Psamathe. Psamanthe, whose name means "sea sand," had turned into a seal to escape his grasp (and failed). She had a son called Phokos, "seal."

**There are several reasons why this was less common in ancient Greece (for example, people finding it repugnant that a deity, any deity, was subservient to a mortal, unless it be by the will of Zeus, or by the influence of European fairy-capture stories).

Extra note: my favourite art of Thetis can be found here.

Sources used: Greek Nymphs, Myth, Cult, Lore, by Jennifer Larson, The Iliad by Homer, Pindar, and the Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes.

#thetis#thetis worship#the nymphs#nymphai#nymph cults#helpol#hellenic reconstructionism#hellenic polytheism#30 days of devotion

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

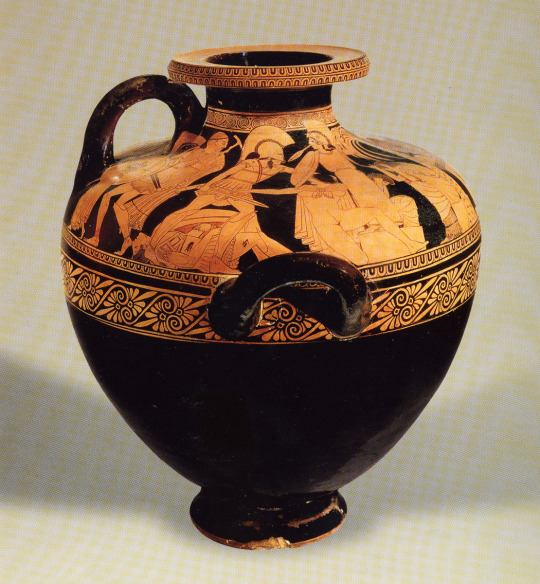

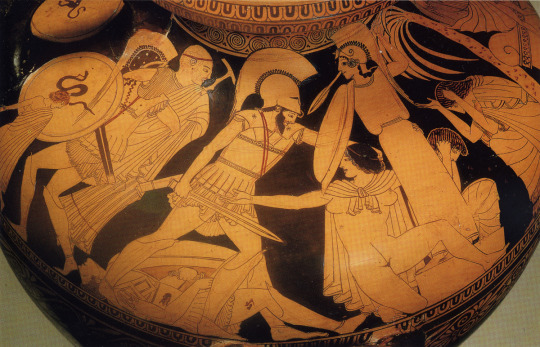

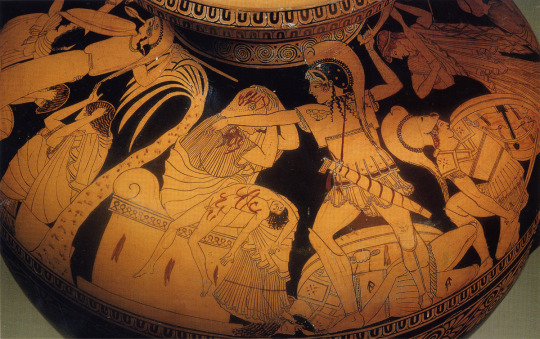

*Pics from Classical Art Research Centre, University Of Oxford

Hydria with the Sack Of Troy by Kleophrade's Painter, early 5th century

This red-figured style vase was painted at the time of the Persian Wars. The Persians plundered Athens destroying the first temples erected on the Acropolis (before the Parthenon) until the Greeks defeated them at the Battle Of Salamis (480 BC). Athens' sack becoming a trauma to the Athenians inspired the so-called Kleophrade's Painter to depict the most legendary sack of a city, none other than Troy, 4 centuries before Virgil.

Second picture

On the left, Aeneas bears his old father, Achises, on his shoulders in order to save him from the massacre. His son, Ascanios, leads them. This moving moment, when Aeneas decided not to leave behind his father despite the danger, signifies the beggining of gods' plan for him, as he'll become the predecessor of the first Romans. The depiction of Aeneas' myth on the vase indicates that Aeneas' destiny was known to the Greeks, before the Aenead, no matter the little written sources about it (of course, this doesn't reduce at all Virgil's marvellous illustration of the myth that turned out to be one of the most famous epic poems ever written).

On tne center, Ajax The Lesser aggressively approaches Cassandra and the other women (perhaps, Andromache, too) who have found refugie to Palladion, Athena's altar. Athena as the Parthenos, meaning the virgin, is supposed to protect the women who turn to it. Therefore, Cassandra was protected by the moral laws of the society as a sacred beggar. Nonetheless, Ajax The Lesser didn't obey to the divine laws and raped the misfortuned Cassandra -the one who had foreseen Troy's end, but no one believed her. The violence of the scene is intesively transmitted, as Cassandra streches her hand pleading and the other women hide their faces and pull their hair in grief, while the heartless Ajax The Lesser walks towards them looking terrifying in full armor. (Nemesis (=punishment) always being important for the greek way of thinking, Ajax The Lesser will suffer Athena's wrath and will be finally killed by Poseidon -in a rare case where Athena and Poseidon's intentions are in line).

Third picture

On the center, it's one of the most realistically painted scenes; Neoptolemos, Achilles' son, after having killed Astyanax, Hector's little son, strikes Priam, who is covered with blood. The old king will die along with his city, completely defenceless. The vivid red color not only attracts the viewer's attention, but makes it look like it comes straight out of a horror film increasing the scene's drama.

All in all, I love this vase, as it enclosures many different myths connected with a single event. There's much movement and tension, while the bodies' position (for example, look at the last pic how Neoptolemos has turned his body) and the effort to depict real space (for instance, at Neoptolemos' feet a dead soldier looks like he's three dimensional) make the scene a lot realistic. Forgetting the virtuous Achilles and Helen's beauty, we come face to face with the war's cruelty, where the heroes turn to beasts.

#archaeology#art#greece#greek art#greek mythology#myth#classic greece#vase#ancient greek vase#ancient vase#troy#troyan war#persian wars#athens#priam#cassandra#neoptolemos#ajax the lesser#aeneas#ascanio#achises#red-figured#sack of troy#kleophrade's painter

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi everyone, i'm back with my bullshit. Thanks specially to @margaretartstuff for giving me this idea.

Time to disappoint you all with my 7 ( 6 actually- ) different editions ( or versions- ) of the Odyssey, each one worse than the last because i got most of them when i was like 10 years old ! The good old days were i didn't have to worry about being a functional adult. Anyways.

1. ) This one for some reason includes the Homeric Hymns as well:

i remember buying it ONLY because in the one i already owned had Odysseus named "Ulysses" and i was going through a phase in which i was picky about it. Well i don't think i ever left that phase, let's be real 🥲

it's a good one, i like this one a lot, since as i said it includes other things as well.

The translation is good in general as well ( i mean they wrote "Helio(s)" instead of Sun, but that's up to the translator after all ), the verses have numbers as well and they didn't erase any part from it.

2. ) Oh this one, i have mixed feelings about this one:

The book is SO PRETTY and the translation is pretty nice as well, but uh, it includes that one "Penelope's Version" that Margaret Atwood wrote that is a big nono for me, it's one of those "feminist" retellings that WHAT A SURPRISE keep calling Helen a w/hore, but oh well.

It has some pretty drawings, they're funny more than anything else, but it calls Odysseus "Ulysses" so yeh, haven't read this version on a long time.

3. ) THIS IS— A MANGA—:

I've seen some people around here talking about it before sksnsk it's pretty, it's fun, but it's VERY short and i hate it.

It also, for example, include stuff that wasn't in the Iliad and lacks stuff that was in the Odyssey, like the Circe and the Sirens episode. I mean it is supposed to be summarized, but i wished it was longer, i'll find a newer comic someday...

Sooomedaay...

LOOK AT THESE ODYSSEUS AND PENELOPE !!

My main complain is the lack of, well, you know the drill, Minoan fashion, but wellp.

4. ) This is the one i use when i read the Odyssey out loud to little kids, literally:

It's very, VERY goofy. The drawings are just very cute to me and i can't help but laugh whenever i take a loot at it.

It's not perfect, i mainly use it as i said when i'm reciting the poem outloud, but look at that Helios

Look at that yellow dude with the rays of the sun as his moustache

i mean it does some stuff that did make me go "ehh" like saying "Helios, the god of the Sun" when Helios literally means sun, but not everyone knows that ( i think? ) so maybe that's the reason behind it.

And yes i'm aware that Odysseus is called Ulysses, welcome to Spain, most of the translations have that name and, well, you know, Hispania roots and all that.

5. ) MY FAVOURITE !!!

This. This thing right here. I love it with all my heart. It has illustrations that are either vase paintings, or mosaics, or more later-on paintings. The only complain i have is that the painting used for the sirens depicts them as mermaids- but oh well, they're called the same in Spanish so what am i gonna do about it 🥲

My personal favourites are these !! A couple of them sre actually very well-known:

Had to put them together due to Tumblr's limit of pictures. Sorry that they're kind of blurry, the pages are made of *that* paper.

I've read this edition multiple times and i still don't get tired of it, it's probably not the best one since i'm looking at it with the lens of a ξένο κορίτσι, not a Greek, so maybe if one had a look at it, it isn't that good, who knows.

6. ) Now, uh, yeh— a thing—:

Sometimes i forget the fact that the author is Italian.

This is a version for children aaaaandddd...

I mean- what else am i supposed to say about this version, i got it when i was 8, thanks to it Odysseus became the first and favourite Greek hero for me.

Is this cringy? Sorry about it 🥲

7. ) The seventh one is an old PDF document that i had to read when i first started learning Greek. It still has my notes and people don't like my handwriting much, so i'm leaving this here.

Hope you had fun ! And hope that you laughed at me, that one girl that knows the whole Odyssey by heart.

No i'm not ok.

#this was fun and. at the same time. self concerning.#imagine being Greek and finding out that some Spanish woman has a weird obsession#with a poem related to your culture#i would freak out#also TUMBLR isn't letting me post this#and i'm going insane#the odyssey#odyssey#not incorrect quotes

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

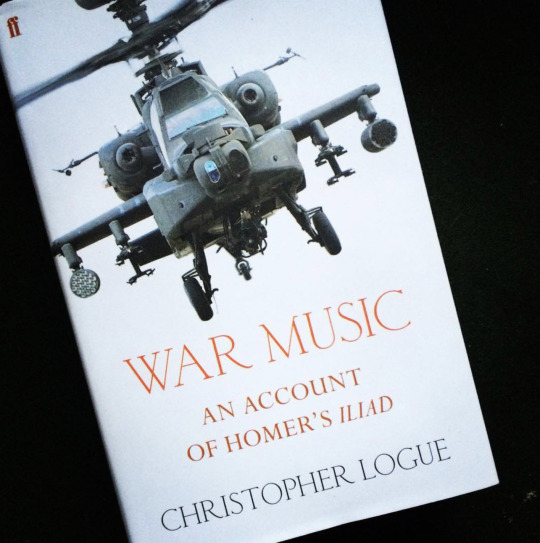

Black Swan bookgasm review #1: War Music by Christopher Logue (1981)

This is the first in a series of random book reviews taken from my own hand written notes in my journal. Notes are re-edited to make it into a more coherent presentation with the hope others would read the book for themselves.

War Music by Christopher Logue (1981)

War Music by Christopher Logue comprises versions of Homer’s Iliad published over decades since 1981. It’s a modern, cinematic re-rendering of the Greek epic which manages to re-cast Homer’s battles for twentieth-century readers.

I first read parts of it when I went out on tour to Afghanistan as a combat helicopter pilot. It was a ragged dog eared copy given to me by one of my older siblings who had served in the armed forces with distinction and now he wanted me to have it since I was being deployed to Afghanistan.

In between down times between missions I would read it and just soak in its inventive use off language to tell a story birthed at the dawn of Western civilisation and teaching a lesson as old as civilisation itself: that all wars are the same wars.

The English poet Christopher Logue called himself a “Catholic atheist.” Were he religious, he said, he would look out for God in creation. “Did the ancient Greeks believe in their gods as I believe in the ancient Greeks?” he wondered. One of the Lasallian Brothers at his Catholic school in Southsea told him about the elaborate ornamentation hidden from view on cathedral roofs, “safe in the sight of God until Judgment Day.” This information convinced the young Logue to work from that day in the spirit of the medieval carvers: without justification. “That I did not know what I wanted to do was unimportant,” he wrote.

Logue, born in Portsmouth in 1926, described his father as “a devout Irish-English Catholic.” His paternal grandfather, a Catholic from Coleraine in Northern Ireland, spent twenty-two years in the British Army. His Irish aunt Margaret taught him to read and write. “Atheism?” she once admonished him. “There’s no such thing. A silly boast God finds no trouble in forgiving.” Logue never stopped believing in God, he said, because he had never started believing in Him. “I find the idea of a beginning as impossible to credit as that of an end.” His own atheism left him unimpressed. He preferred the company of people whom he knew to be religious.

Logue always envied people with a purpose. It was not until 1959, after a stint in a military brig and a period writing pornography in Paris, that he found his. In his early thirties and already feeling old, he was asked by the classicist Donald Carne-Ross, then working for the BBC, to adapt a passage from the Iliad for an English version he was broadcasting on the Third Programme. Doris Lessing, a close acquaintance, had told Logue that the Iliad, if not the task of its translation, suited him well: “Something to do with heroism, tragedy, that sort of thing.” But Logue found Homer boring. Carne-Ross proposed a section of Book XXI in which Achilles attacks the river Scamander, provided Logue with a prose crib and advised him to read published translations to get a sense of the story. “A translator must know one language well,” Carne-Ross told Logue. “Preferably his own.”

Carne-Ross also advised Logue to go away and “read translations by those who did. Follow the story.” Logue gave it a go, and the result sowed the seed of what was to blossom over the decades into the centrepiece of Logue’s working life; his ultimate creative endeavour.

For more than forty years the English poet Christopher Logue worked in fits and starts on his narrative poem War Music, subtitled An Account of Homer’s Iliad. The poem, which he was unable to complete before he died in 2011, was published in several sections titled War Music (1981), Kings (1991), The Husbands (1995), All Day Permanent Red (2003), and Cold Calls (2005), corresponding, respectively, to Books 16-19, 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, and 7-9 of The Iliad. These books were brought together in a single volume by Faber publishers that tells the story of Logue’s fragmentary and highly original Trojan War.

Clearly the poem cannot be read outside of its relation to The Iliad, but we also cannot call it a “translation” in the familiar sense. To do so would suggest that it belongs in the same category as works produced with an aim of comprehensive fidelity to the original’s language and structure, texts such as those by Richmond Lattimore, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert Fagles, and Stanley Lombardo.

Is War Music, then, a form of loose translation, a “carrying over” of spirit, with all the liberty that implies? Is Logue, as Gary Wills wrote, the third in an exclusive tradition of English poets, after George Chapman and Alexander Pope, “to bring Homer crashing into their own time”? I think so.

Logue drew inspiration from a vast range of sources. The lines with which Zeus surveys the Trojan plain after a day’s fighting have been taken directly from a New Yorker piece on the first Gulf War: “He looks/ Back to the Ridge that is, save for a million footprints,/ Empty now”. When Agamemnon shouts Achilles down, his words are half-borrowed from Milton’s Lycidas: “Blindmouth!/ Good words would rot your tongue”. Snippets of the venerable translations by Pope and Chapman pop up at unexpected moments, amid the ultra-violence of Logue’s battle scenes.

War Music is a translation that takes no prisoners. No line of Homer’s survives un-annealed by the application of English. Like Homer, Logue is absolutely unapologetic about the business of bloodletting. This attitude complements his insusceptibility to beauty. “In verse (as elsewhere) beauty will serve any view and give it a glamour,” he wrote, pondering the case of Ezra Pound. “We should not be afraid to call it whorish.” Logue takes courage in this matter from the example of the Iliad. “The Greeks are not humanistic, not Christian, not sentimental,” Xanthe Wakefield told him on the occasion of his first looking into Homer. “Please try to understand that. They are musical.” Logue sets himself the challenge of converting the sounds of slaughter into the chimes at midnight. This requires an acute sensitivity to fate untinged by timidity. In one of his working notes Logue reminds himself to supply, at a certain point in the poem, a simile for “how far courage can take you.” In truth his whole work stands as an extension of that simile, almost to its breaking point.

Logue’s retelling of the Iliad plays with the idea that, when it comes to war, any sort of ending is an illusion. His decision to illustrate Homer’s story of brave men and bickering gods with flagrantly anachronistic combat imagery (“whumping” helicopters; Uzis “shuddering warm against your hip”) makes the point that, when it comes to war, the best humanity has ever managed is the odd break between battles. This is certainly how I felt in my down time between missions. The whumping sound of the rotar blades throbbed in my ear as I got into the cockpit of my helicopter - many times it made me think of Logue’s haunting lines.

War Music is incomplete because the war isn’t over. “Someone”, the last line reads, “has left a spear stuck in the sand.” It’s an ideal outgoing image: still, striking, but throbbing with potential; gesturing to the wars to come. As I left Afghanistan I thought about my colonial ancestors who had sought adventure and high service in this beautiful barren land and that I was but a passing present incarnation and then the chilling sad thought struck me that I know I won’t be the last in the wars to come.

It is, of course, frustrating that War Music will never be complete but the collected edition one can buy now gives us a definitive text of one of the strangest and most thrilling English poems since the 20th Century. It also confirms that Logue’s Homer deserves a place alongside those of Chapman and Pope.

#covid19#book review#book#reading#logue#war music#christopher logue#history#classical#homer#poem#personal#bookgasm#literature

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Silmarillion - A (generic) review

Maglor casts the Silmaril into the sea, by Ted Nasmith.

The Silmarillion - or story of the Silmarils - is one of those must-see classics for everyone who is a Tolkien fan or wants to know more about the universe he developed, in much more detail, in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

It is important to note that we are not talking about a linear history but a compendium of myths and legends from Middle-earth that include the Ainulindale - "the song of the Ainur" - which would be like the Genesis or creation of the world (Arda), the Valaquenta - history of the Valar or gods that rule the world -; the Quenta Silmarillion - the history of the Silmarils, which gives its name to the complete compendium, but which is only a part, the largest, of it -, Akallabeth (or history of the rise and fall of Númenor, which comes to be as a reinterpretation of Atlantis, a la Tolkien) and for one, an epilogue briefly summarizing the history of the Rings of Power and the Third Age, which is really the basic content from which the history of The Lord of the Rings expands.

What is the problem - if you can call it that - that The Silmarillion has? It is not an easy read. Even those who have successfully completed The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings cannot guarantee that The Silmarillion will not completely defeat them. That is why I say that it must be borne in mind that it is a compendium of traditions, myths and legends, that Tolkien Sr. never managed to conclude and give it a publishable format, so it corresponded to his son, Christopher, who left us at the beginning of the year, give it this format that we know and that, although nothing easy, was at least somewhat readable.

Once you get the idea that this is not a fluid, linear, or fast reading, you probably find the most beautiful stories that the Professor imagined to give body and depth to his universe, and to which you must approach with the respect and daily dosage with which you would read the Bible - if you are one of those who still read the Bible -. Really, The Silmarillion has everything. Do you want a Creation story? Ainulindale. Do you want to read about the different gods and spirits of Middle-earth, both Valar and Maiar? Valaquenta. And with the history of the Silmarils you are already immersed in a world that has the same solidity and depth as the ancient epic poems of the north and why not, also of the old Mediterranean civilizations. Only instead of Vikings, Trojans, or Greeks, we have elves, humans, dwarves, and orcs.

Do you want the most beautiful love story? Read the legend of Beren and Lúthien. Do you want a heartbreaking tragic hero, a Greek drama in all its essence? There you have Turin Turambar and his cursed lineage. Do you want drama and fate and curse? Meet Feanor and her children, who for a damn trio of jewels - yes, okay, the Silmarils are the most valuable gems in the world, as they contain the light of lost paradise - BUT THEY ARE STILL A DAMNED TRIO OF JEWELRY, they make a an oath that will mean family annihilation and that, in the end, will only bring them pain and ruin.

Unforgettable moments of unique beauty are often yours, such as Fingon rescuing his cousin Maedhros hung and tortured in Thangorodrim (undoubted flavor of Prometheus Chained); Lúthien metamorphosed into a monster to the rescue of her mortal lover; Turin accidentally killing his beloved friend Beleg and later, unknowingly marrying his own sister, giant eagles, fire-breathing dragons, a Dark Lord before the Dark Lord that we all know who simply likes to punch mortals and immortals. ; all revolving around the mantra that the author liked so much to cultivate: absolute power corrupts. Absolutely corrupts. There is nothing in the world, neither the most glorious city nor the most valuable jewel, worth death and destruction.

Tuor arrives at Gondolin, by Ted Nasmith.

The Silmarillion is a song to paradise lost. Without a trace of humor and yes with a lot of melancholy and sadness, and beauty in abundance, yes, Tolkien was able to create a mirror of the past of our world that served in equivalence to his own world.

Recommended for Tolkien fans, yes, as I said, in small daily doses. And if you have the chance to get an illustrated edition, either by Alan Lee or Ted Nasmith (which was my case, better than better).

And if you can't handle it, leave it, you're not going to impress anyone either. There are specific editions on individual stories like Beren and Lúthien or the Children of Húrin that perhaps you can digest. As soon as this quarantine is over, I will see if I can get hold of them.

#the silmarillion#books#j.r.r. tolkien#christopher tolkien#reviews#my reviews#illustrator#ted nasmith#cover art

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

MYTHOLOGY MASTERPOST

In response to an ask, I’ve compiled this masterpost of mythology resources. It’s by no means comprehensive, as myth is an extremely broad subject, and I’ve mainly focused on Greco-Roman mythology. I’ve tried to include a range of websites alongside books and original sources, so you can get by without spending anything. The upside to Classics being a kinda dusty subject is you can find so many texts online for free!

THE ESSENTIALS

If you’re just starting to get interested in mythology then it can be pretty daunting & it’s hard to know where to start. So, to help, here’s some recommendations for websites/texts that lay out the information without assuming any previous knowledge

theoi.com is an absolutely brilliant resource for anyone interested in mythology. It is stunningly comprehensive, with information on every god, goddess, nymph, monster and hero appearing in Greek mythology! Every entry has so much well researched information about the god and stories they appear in, and even includes excerpts from the original sources.

There are, of course, countless books dedicated to telling, or retelling, myths, and everyone seems to have their favourite. Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes by Edith Hamilton is a popular one, and is really good at telling the stories without dumbing them down, and I really like the way Hamilton writes too. It also has some bonus Norse mythology at the end!

Alternatively, Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths is also really good, and very comprehensive, although fairly hefty at about 800 pages.

Stephen Fry recently released his own retelling of the myths, entitled Mythos, which I really need to get around to reading. It’s a bit of a random selection of myths, but includes quite a few of the LGBT ones from what I’ve seen. You can also pick up an audiobook of him reading it – if you grew up listening to him narrate the Harry Potter books, I would definitely recommend this.

INTERMEDIATE

If you enjoyed those, and want to learn more about ancient mythology, I would really recommend then starting to delve into the original source material.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is a pretty good place to start. It’s a collection of over 250 stories from creation to Julius Caesar, all linked by the theme of transformation, but it’s fairly easy to dip in and out of – think of it kind of like a short story anthology. Here is the entire work online for free, and I also found another site here which is Dryden’s translation - a little more old fashioned but closer to the poetic style, so it just depends what you prefer. If you wanted to buy

Apollodorus’ Bibliotheca is another great ancient compendium of myths. It covers the gods taking over from the titans, Hercules’ labours, and finishes at the Trojan War. Which brings me to…

Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. With 24 books each, Homer’s epic poems can look pretty intimidating. But I would really, really recommend reading them. There are a myriad of different translations, which I will get into later, but to start off I would suggest either Fagles or Lattimore. I found full texts of both online, here and here although I'm not sure what translations they are.

EXTRA RECOMMENDATIONS

At this point I got a bit carried away. If you’re scrolling through this thinking you’ve already read a lot of these, here’s some extras.

I love the Homeric Hymns. Anddd I found a website here which has all the hymns – and displays with the original Ancient Greek and English translation side by side, which is really handy if you, like me, are attempting to learn Ancient Greece.

If you feel like you’re used to all the weirdness of Greek myths, boy have I got news for you. Ancient Egyptian myths make Pasiphae look tame. Try reading a very serious story about a god jizzing into a rival god’s salad in order to become king. If that sounds interesting: get help! Just kidding, read this book: The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt by Richard Wilkinson. It’s very comprehensive, and also has lots of fantastic illustrations.

If you want an original source to read for the Egyptian myths, I’d suggest The Egyptian Book of the Dead, translated by Raymond Faulkner and Ogden Goelet

Kevin Crossley-Holland’s The Penguin Book of Norse Myths: Gods of the Vikings is another good introductory book to another set of myths, this time Norse. He’s a novelist in his own right (anyone else read The Seeing Stone?) and this comes across clearly in the ways he tells the stories.

TRANSLATIONS

Please bear in mind that there are lots of different translations of ancient texts. I am not an authority in which one is best, and there isn’t a simple answer in any case, but I made my above suggestions based on either what I’ve personally read, or a translation I’ve heard good things about. That said, if you are interested in translation theory pls send me a message and we can yell about it together then here’s a few more recommendations.

Above, I recommended Lattimore or Fagles as a good starting point for Homer. If you don’t know which to pick, as a very broad generalisation Lattimore’s is more like poetry, and Fagles’ reads more like prose. (I may get people who disagree. Everyone has an opinion on translations.) Lattimore stuck to the original daxylyctic hexameter of the Ancient Greek text and, perhaps most impressively, stuck to the same line count as Homer. Fagles is more readable, but perhaps loses something in this. I honestly haven’t decided which I prefer yet. But for a first read of Homer, I would definitelty recommend one of these two – it just depends whether you are reading more for the poetry or for the story.* Robert Fitzgerald’s translation of the Iliad is also very popular, although it’s far looser a translation than the above two. This makes it kind of easier to read, but I personally think it’s a bit too loose to be perfectly honest.

Alexander Pope’s translation is a much earlier translation, published in 1720, and the language shows. However his translation is brilliant at conveying the drama and grandeur of Homer’s work.

There was a lot of excitement on Tumblr at announcement of Emily Wilson becoming the first woman to translate Homer’s Odyssey into English. I haven’t had a chance to read it yet (and I want to so badd) but from the excerpts I’ve seen and all the interviews and articles I’ve read it looks absolutely stunning. Please read this.

There is a super handy Wikipedia page which shows the first few lines of the Iliad/Odyssey as translated by every English translator ever. It makes for super interesting reading, but can also help you choose one to read that appeals to you!

For other texts: I’m currently studying The Aeneid using David West’s translation, Medea and Hippolytus as translated by Edith Hall, and Bernard Knox’s translation of Oedipus the King and Antigone. I’ve been enjoying all of these. If you’ve been following me a while, you’ll know I’m a big fan of Anne Carson. She translated Sappho, and some tragedies as well. Her translations focus more on conveying the poetry or feelings behind the words rather than an exact translation of the words themselves, which makes for electrifying reading if you’re used to perhaps more staid translations. Antigonick was a particular favourite of mine, probably because I knew the play so well so I was able to really appreciate the changes and decisions she made, although it was more an intepretation than a translation. This difference, as brilliant as it is, is why I would, however, suggest you read other translations first before attempting Carson.

I hope this was helpful! A second masterpost focusing on more general Classics resources will be coming soon.

#tagamemnon#masterpost#mythology#Greek Mythology#classics#tsoa#hellenism#yall this took me so long#but now i need sleep#mine#soz for dumping this in the tsoa tag ill take it out later i want Recognition

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Observing How God Cares For You

The word worry comes from the Old English term wyrgan, which means “to choke” or “to strangle”.

God wants His children preoccupied with Him, not with the mundane, passing things of this world. He says,

“Set your mind on the things above, not on the things that are on earth” (Col. 3:2).

Fully trusting our Heavenly Father dispells anxiety. And the more we know about Him, the more we will trust Him.

Many rich people worry about necessities - that’s why they stockpile so much of their resources as a hedge against the future. Many poor people also worry about life’s essentials, but they aren’t in a position to stockpile.

The Scripture says,

“Seek first the Kingdom of God and His righteousness (Matt. 6:33)“ and “lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven (v. 20)“

We are not to lavish on ourselves what God has given us for the accomplishments of His holy purposes.

Jesus says, “Do not be anxious for your life, as to what you shall eat, or what you shall drink; nor for your body, as to what you shall put on. Is life more than food, and the body than clothing?” The tense in the Greek text is properly translated, “Stop worrying.”

Furthermore, focusing on earthly treasures produces earthly affections.

“Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also” (Matt. 6:21)

It blinds our spiritual vision and draws us away from serving God. That’s why God promises to provide what we need.

As children of God we have a single goal - treasure in heaven; a single vision - God’s purposes; and a single Master - God, not money. Therefore, we must not let ourselves become preoccupied with the mundane things of this world.

Life comes from God - and the fullness of life from Jesus Christ.

Three reasons why not to Worry

It is unnecessary, because of our Father

It is uncharacteristic, because of our faith

It is unwise, because of our future

Worry is Unnecessary because of our Father

God is the Owner, Controller, and Provider, and beyond that as your loving Father, then you know you have nothing to worry about. Jesus said, “What man is there among you, when his son ask him for a loaf, will give him a stone? Or if he shall ask for a fish, he will not give him a snake, will he? If you then, being evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more shall your Father who is in heaven give what is good to those who ask Him!” (Matt. 7:9-11)

Jesus illustrates that with three observations from nature.

God always feeds his creatures.

In Matthew 6:26 Jesus says, “Look at the birds of the air, that they do not sow, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not worth much more than they?”

Matthew 10:29-31 says “Are not two sparrows sold for a cent? And yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father. But the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Therefore do not fear; you are of more value than many sparrows”.

“Life is a gift from God. If God gives you the greater gift of life itself, don’t you think He will give you the lesser gift of sustaining that life? Of course He will, so don’t worry about it.”

But keep in mind, of course, that like a bird, we have to work because God has designed that man should earn his bread by the sweat of his brow (Gen. 3:19). If we don’t work, it is not fitting that we eat (2 Thess. 3:10). God provides for man through his effort.

Worry is unable to accomplish anything productive.

“Which of you by being anxious can add a single hour to his span of life?

Not only will you not lengthen your life by worrying, but you will probably shorten it. Job 14:5 says of man, “His days are numbered, the number of his months is with Thee, and his limits Thou hast set so that he cannot pass.”

To worry about how long you are going to live and how to add years onto your life is to distrust God. If you give Him your life and are obedient to Him, He will give you the fullness of days. You will experience life to the fullest when you live it to the glory of God. No matter how long or short, it will be wonderful.

God arrays even the meadows in splendor.

28 And why are you anxious about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin, 29 yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. 30 But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which today is alive and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you, O you of little faith? (Matt 6:28-30)

Wildflowers have a very short life span. People would gather dead batches of them as a cheap source of fuel for their portable cooking furnaces. A God who would lavish such beauty on temporary fire fodder certainly will provide the necessary clothing for His eternal children.

An anonymous poem expresses this lesson simply,

Said the wildflower to the sparrow,

“I should really like to know,

Why these anxious human beings

Rush about and worry so.”

Said the sparrow to the wildflower,

“Friend I think that it must be,

That they have no Heavenly Father,

Such as cares for you and me.”

Worry is Uncharacteristic because of our Faith

If you worry, what kind of faith do you manifest? “Little faith”, according to Matthew 6:30

Words from the book Anxious For Nothing by John Mac Arthur.

0 notes

Link

A Divine Council is an assembly of deities over which a higher-level god presides.

Contents

1Historical setting

2Archaic Sumerian

3Akkadian

4Old Babylonian

5Ancient Egyptian

6Babylonian

7Caananite

8Hebrew

9Chinese

10Celtic

11Ancient Greek

12Ancient Roman

13Norse

14See also

15References

16External links

Historical setting

The concept of a divine assembly (or council) is attested in the archaic Sumerian, Akkadian, Old Babylonian, Ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Caananite, Israelite, Celtic, Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman and Nordic pantheons. Ancient Egyptian literature reveals the existence of a "synod of the gods". Some of our most complete descriptions of the activities of the divine assembly are found in the literature from Mesopotamia. Their assembly of the gods, headed by the high god Anu, would meet to address various concerns.[1] The term used in Sumerianto describe this concept was Ukkin, and in later Akkadian and Aramaic was puhru.[2]

Archaic Sumerian

One of the first records of a divine council appears in the Lament for Ur, where the pantheon of Annunaki is led by An with Ninhursag and Enlilalso appearing as prominent members.[3]

Akkadian

The divine council is led by Anu, Ninlil and Enlil.[4]

Old Babylonian

In the Old Babylonian pantheon, Samas (or Shamash) and Adad chair the meetings of the divine council.[4]

Ancient Egyptian

The leader of the Ancient Egyptian pantheon is considered to either be Thoth or Ra, who were known to hold meetings at Heliopolis (On).[5][6]

Babylonian

Marduk appears in the Babylonian Enûma Eliš as presiding over a divine council, deciding fates and dispensing divine justice.[7]

Caananite

Texts from Ugarit give a detailed description of the structure of the divine council, where El and Ba'al are presiding gods.[8]

Hebrew

The Council of Gods, Giovanni Lanfranco (1582–1647), Galleria Borghese

Loggia di Psiche, ceiling fresco by Raffael and his school (The Council of The Gods), Villa Farnesina, Rome, Italy, by Alexander Z., 2006-01-02

In the Hebrew Bible, there are multiple descriptions of Yahweh presiding over a great assembly of Heavenly Hosts. Some interpret these assemblies as examples of Divine Council:

"The Old Testament description of the 'divine assembly' all suggest that this metaphor for the organization of the divine world was consistent with that of Mesopotamia and Canaan. One difference, however, should be noted. In the Old Testament, the identities of the members of the assembly are far more obscure than those found in other descriptions of these groups, as in their polytheisticenvironment. Israelite writers sought to express both the uniqueness and the superiority of their God Yahweh."[1]

The Book of Psalms (Psalm 82:1), states "God (אֱלֹהִ֔ים elohim) stands in the divine assembly (בַּעֲדַת-אֵל ); He judges among the gods (אֱלֹהִ֔ים elohim)" (אֱלֹהִים נִצָּב בַּעֲדַת־אֵל בְּקֶרֶב אֱלֹהִים יִשְׁפֹּט). The meaning of the two occurrences of "elohim" has been debated by scholars, with some suggesting both words refer to YHWH, while others propose that God rules over a divine assembly of other Gods or angels.[9] Some translations of the passage render "God (elohim) stands in the congregation of the mighty to judge the heart as God (elohim)"[10] (the Hebrew is "beqerev elohim", "in the midst of gods", and the word "qerev" if it were in the plural would mean "internal organs"[11]). Later in this Psalm, the word "gods" is used (in the KJV): Psalm 82:6 - "I have said, Ye [are] gods; and all of you [are] children of the most High." Instead of "gods", another version has "godlike beings",[12] but here again, the word is elohim/elohiym (Strong's H430).[13] This passage is quoted in the New Testament in John 10:34.[14]

In the Books of Kings (1 Kings 22:19), the prophet Micaiah has a vision of Yahweh seated among "the whole host of heaven" standing on his right and on his left. He asks who will go entice Ahab and a spirit volunteers. This has been interpreted as an example of a divine council.

The first two chapters of the Book of Job describe the "Sons of God" assembling in the presence of Yahweh. Like "multitudes of heaven", the term "Sons of God" defies certain interpretation. This assembly has been interpreted by some as another example of divine council. Others translate "Sons of God" as "angels", and thus argue this is not a divine council because angels are God's creation and not deities.

"The role of the divine assembly as a conceptual part of the background of Hebrew prophecy is clearly displayed in two descriptions of prophetic involvement in the heavenly council. In 1 Kings 22:19-23... Micaiah is allowed to see God (elohim) in action in the heavenly decision regarding the fate of Ahab. Isaiah 6 depicts a situation in which the prophet himself takes on the role of the messenger of the assembly and the message of the prophet is thus commissioned by Yahweh. The depiction here illustrates this important aspect of the conceptual background of prophetic authority."[15]

Chinese

In Chinese theology, the deities under the Jade Emperor were sometimes referred to as the celestial bureaucracy because they were portrayed as organized like an earthly government.

Celtic

In Celtic mythology, most of the deities are considered to be members of the same family - the Tuatha Dé Danann. Family members include the Goddesses Danu, Brigid, Airmid, The Morrígan, and others. Gods in the family include Ogma, the Dagda, Lugh and Goibniu, again, among many others. The Celts honoured many tribal and tutelary deities, along with spirits of nature and ancestral spirits. Sometimes a deity was seen as the ancestor of a clan and family line. Leadership of the family changed over time and depending on the situation. The Celtic deities do not fit most Classical ideas of a "Divine Council" or pantheon.

Ancient Greek

Zeus and Hera preside over the divine council in Greek mythology. The council assists Odysseus in Homer's Odyssey.[16]

Ancient Roman

Jupiter presides over the Roman pantheon who prescribe punishment on Lycaon in Ovid's Metamorphoses, as well as punishing Argos and Thebes in Thebaid by Statius.[17]

Norse

There are mentions in Gautreks saga and in the euhemerized work of Saxo Grammaticus of the Norse gods meeting in council.[18][19][20] The gods sitting in council in their judgment seats or "thrones of fate" is one of the refrains in the Eddic poem "Völuspá"; a "thing" of the gods is also mentioned in "Baldrs draumar", "Þrymskviða" and the skaldic "Haustlöng", in those poems always in the context of some calamity.[21] Snorri Sturluson, in his Prose Edda, referred to a daily council of the gods at Urð's well, citing a verse from "Grímnismál" about Thor being forced through rivers to reach it.[22][23] However, although the word regin usually refers to the gods, in some occurrences of reginþing it may be simply an intensifier meaning "great", as it is in modern Icelandic, rather than indicating a meeting of the divine council.[24]

See also

Sons of God

War in Heaven

References[edit]

^ Jump up to:a b Sakenfeld, Katharine ed., "The New Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible" Volume 2, pg 145, Abingdon Press, Nashville.

Jump up^ Freedman, David N. ed., "The Anchor Bible Dictionary" Volume 2 pg 120, Doubleday, New York

Jump up^ E. Theodore Mullen (1 June 1980). The divine council in Canaanite and early Hebrew literature. Scholars Press. ISBN 978-0-89130-380-0. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

^ Jump up to:a b Leda Jean Ciraolo; Jonathan Lee Seidel (2002). Magic and Divination in the Ancient World. BRILL. pp. 47–. ISBN 978-90-04-12406-6. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ Virginia Schomp (15 December 2007). The Ancient Egyptians. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7614-2549-6. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ Alan W. Shorter (March 2009). The Egyptian Gods: A Handbook. Wildside Press LLC. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-1-4344-5515-4. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ Leo G. Perdue (28 June 2007). Wisdom Literature: A Theological History. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-0-664-22919-1. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ Mark S. Smith (2009). The Ugaritic Baal Cycle. BRILL. pp. 841–. ISBN 978-90-04-15348-6. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ Michael S. Heiser. "Divine Council 101: Lesson 2: The elohim of Psalm 82 – gods or men?" (PDF).

Jump up^ ""Psalms 82:1"".

Jump up^ HamMilon Hechadash, Avraham Even-Shoshan, copyright 1988.

Jump up^ "godlike beings, in JPS 1917". Retrieved 18 March 2013.

Jump up^ "Psalm 82:6 KJV with Strong's H430 (elohim/elohiym)". Retrieved 18 March 2013.

Jump up^ "John 10:34". Retrieved 18 March 2013.

Jump up^ Freedman, David N. ed., "The Anchor Bible Dictionary" Volume 2 pg 123, Doubleday, New York

Jump up^ Bruce Louden (6 January 2011). Homer's Odyssey and the Near East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-0-521-76820-7. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ Randall T. Ganiban (8 February 2007). Statius and Virgil: The Thebaid and the Reinterpretation of the Aeneid. Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-521-84039-2. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

Jump up^ John Lindow (2002) [2001]. Norse Mythology: A guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780195153828.

Jump up^ Viktor Rydberg (1907) [1889]. Teutonic Mythology. 1 Gods and Goddesses of the Northland. Translated by Rasmus B. Anderson. London, New York: Norroena Society. pp. 210–11. OCLC 642237.

Jump up^ Samuel Hibbert (1831). "Memoir on the Tings of Orkney and Shetland". Archaeologica Scotica: Transactions of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 3: 178.

Jump up^ Ursula Dronke (2001) [1997]. The Poetic Edda (her translation of rǫkstólar). 2 Mythological Poems. Oxford, New York: Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press. pp. 37, 117. ISBN 9780198111818.

Jump up^ The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Translated by Jean Young. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1964 [1954]. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780520012325.

Jump up^ Lindow, p. 290.

Jump up^ Lindow, p. 148.

External links[edit]

Translation of the Lament, from the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature

Michael S. Heiser's Divine Council Website

#divine council#council of the gods#mythology#egyptian mythology#Greek Mythology#roman mythology#sumerian mythology#norse mythology#chinese mythology#celtic mythology#druids#Hebrew#akkadian#mythology campaign#annunaki#extraterrestrial

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dialogue with Atiq Rahimi

By Nadia Ali Maiwandi

From the November 2004 issue of Aftaab Magazine

[caption: Atiq Rahimi on the set of his film Earth and Ashes in Afghanistan.]

Atiq Rahimi was born in Kabul in 1962. He fled the country in 1984, living in Pakistan for a year and then receiving political asylum in France. Rahimi studied film at Sorbonne and made several documentaries about his native land. Earth and Ashes is his first novel, and subsequently his first film in fiction. He currently lives in Paris.

Nadia Ali Maiwandi spoke with Rahimi in October 2004 about Earth and Ashes, the novel and film. The interview was conducted in English, and despite language barriers -- Rahimi was nervous about his English skills -- he was profoundly articulate and poignant, even funny.

Nadia Ali Maiwandi: So much of what's written about Afghanistan lately revolves around the Taliban and their oppressive rule. Earth and Ashes was published in 2000, before the world's awareness of so much of these atrocities. What inspired this tale, and its setting during the Soviet invasion?

Atiq Rahimi: I wrote the novel in 1996 when the Taliban had just come to power. I thought, "Why? Why this violence? Why so much destruction?" During the Soviet war, there was a lot of vengeance, much catastrophe. The Taliban came from this catastrophe. It is important to know where this came from. Also, I wanted to show the three generations of Afghanistan. Dastaguir, the old man, represents Afghanistan's past, its traditions, its customs, its honor. This is the older generation. His son is the present, my generation. He works in a mine; he is the mujahideen generation, the chaos. Yassin, the grandson, is the future. He is deaf, handicapped by war. It is always true that communication between generations does not exist. My generation, the generation of Mujahideen and Communist, has no communication with the past or future.

NAM: What strikes a reader about Earth and Ashes just as much as the story itself is the way it is told. I found the use of second person unusual and with great effect. I wasn't quite sure of your intent, though-- were you looking to draw us into Dastaguir's mind, or distance us from him?

AR: When you are thinking or talking to yourself, you always use "you" [in referring to yourself]. I used the second person to illustrate that Dastaguir is alone. He hasn't another person. This is introspection. Secondly, the use of this narrator creates a disassociation with the reader, but it is subtle. The words are specific, but the use of "you" makes the distance between the reader and the character.

NAM: Yes, sometimes the narrator is Dastaguir's conscience, offering him advice or scolding him. Other times it interrupts and speaks to other characters. It seemed to work as Dastaguir's inner voice at times, and the voice of God at other times.

AR: Yes, it is an experiment in narration, in each context the narrator changes. Anyone who listens becomes one of the characters and the narrator itself becomes one of the characters. It is like when you are writing a letter, you write about yourself and you change the narrator. The events you write are as you narrate them. Also, a lot of our great poetry is written in the second person. It was a tool that many ancient poets used who wrote in Farsi, especially when the poems are directed toward God.

NAM: There are many connections made in the prose to the ancient text of Ferdowsi's Shahnama (The Book of Kings). Why did you choose to include this work in Earth in Ashes and connect it so heavily to your characters?

AR: It is very similar to Shahnama-- Rustam knows his son only after the war. Shahnama is like the Greek story of Oedipus, who unknowingly kills his father in the war and then marries his mother. Except in Shahnama, the father kills the son. It is reversed. This illustrates the patriarchal society of Afghanistan. Women are absent.

NAM: I did notice there were no live women in your novel.

AR: Did you notice that? Yes, there is not one woman except for in dreams and in the past. Women are absent. Woman is imagined.

NAM: So you feel that Dastaguir is like Rustam because he has bad news to deliver to his son, which may kill him.

AR: Yes, the connection is made because what he says to his son might cause his own son's death.

NAM: I noticed a lot of symbolism in the story, especially apples. To me, I thought of the apples and the apple-blossom scarf to mean hope-- when you think of blossoms, you think of spring, of new life. Is this what you meant to convey?

AR: There is a lot of symbolism of apples. It is in a lot of our poetry. Apples were the first food of man and woman. The reader can interpret for themselves what these things mean because it means something different to each one.

NAM: I noticed a lot of symbolism in the story, especially apples. To me, I thought of the apples and the apple-blossom scarf to mean hope-- when you think of blossoms, you think of spring, of new life. Is this what you meant to convey?

AR: (Rahimi laughs) It was not at all easy to adapt to film. I worked on the film for two years. I had to find cinematic language, see how to show all these things in cinema.

NAM: How did you find actors?

AR: That was also not easy. All but one had no professional experience. I auditioned over 60 for the part of the old man and about as many children. I took auditions in Kabul and Pul-e Khumri. That's where it was shot, in Pul-e Khumri, northern Afghanistan.

NAM: How was the film received in Afghanistan?

AR: Very well, really. I had two conditions on showing it: One, that is must not be censored. There is a scene where a naked woman is running-- I did not want it censored. It is not pornographic-- it had a reason. Two, I wanted a mixed audience of men and women, no separation.

NAM: And both of your conditions were met?

AR: Yes.

NAM: How were you able to do that..?

AR: (He laughs) I don't rest until I get what I want.

NAM: Congratulations on your many awards. Winning the Cannes must have been exciting.

AR: Yes, thank you. We won Cannes, and also Best Film and Best Actor in the Osian Cinefan Film Festival held in New Dehli.

NAM: Are there any plans to bring the film to the United States?

AR: It is coming to the New York Museum, perhaps around March. Also in Berkeley, California for a film festival there.

NAM: What are you working on now?

AR: I have a new book, One Thousand Houses of Dreams and Terror, which was published two years ago in Europe, and has been translated into many languages-French, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, German, and many others. This one is about the women of Afghanistan-- and love and war and terror. I'm currently working on translating this novel into a film.

About Nadia Ali Maiwandi

Nadia Ali Maiwandi was born in New York City, New York. Maiwandi has a BA in English and Creative Writing.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ch. 2: “The Empress of Mars” Analysis Doctor Who S10.9: Friday, Odin & the Doctor; Missy’s 2 Faces; Etc.

Apologies for getting these 3 chapters for “The Empress of Mars” out after the airing of “The Eaters of Light.” I post first on Archive Of Our Own, which I did before the 10th episode. With photos, it takes more time to post here.

If you missed the 1st chapter, check it out Ch. 1: Fastballs, Mars-Not-Mars, Rassilon References, Etc.

NOTE:

TPEW = “The Pyramid at the End of the World”

TRODM = “The Return of Doctor Mysterio”

THORS = “The Husbands of River Song”

CAL = Charlotte Abigail Lux, the little girl from the Library

TOS = The Original Series of Star Trek

TNG = Star Trek: The Next Generation

Norse Mythology & Vikings Have a Big Role

Roman and Egyptian mythology aren’t the only mythological references in “The Empress of Mars.” Norse Mythology, for example, has a huge role in the episode, as well as other Viking references.

Egil & Eagle

At NASA, we see a sign “EGIL” in front of the Doctor in the image below, which refers to Egill Skallagrímsson (Anglicized as Egil Skallagrimsson). The Doctor, The Ghost, is associated here with Egil. At first we see the sign without the Doctor.

According to Wikipedia, Egil “was a Viking-Age poet, warrior and farmer. He is also the protagonist of the eponymous Egil's Saga. Egil's Saga historically narrates a period from approximately 850 to 1000 CE and is believed to have been written between 1220 and 1240 CE.”

Egill was born in Iceland, the son of Skalla-Grímr Kveldúlfsson and Bera Yngvarsdóttir, and the grandson of Kveld-Úlfr ("Night Wolf"). His ancestor, Hallbjorn, was Norwegian-Sami.

Here’s another wolf reference, where the Doctor-mirror is the grandson of a metaphorical wolf.

When Grímr arrived in Iceland, he settled at Borg, the place where his father's coffin landed. Grímr was a respected chieftain and mortal enemy of King Harald Fairhair of Norway.

OK, the term “Borg” automatically conjures thoughts of several Star Trek: TNG episodes where alien cyborgs known as the Borg show up to assimilate people, turning them into Borg and absorbing them into the collective. They first show up in the episode “Q Who?” Um… I never thought about this before, but wow, just change Q to Doctor! Captain Picard gets converted to a Borg in “The Best of Both Worlds.” Part 1 was the finale to Season 3, while Part 2 was the premiere of Season 4.

Egill composed his first poem at the age of three years. He exhibited berserk behaviour, and this, together with the description of his large and unattractive head, has led to the theory that he might have suffered from Paget's disease. As professor Byock explains in his Scientific American article, Paget's disease causes a thickening of the bones and may lead eventually to blindness. The poetry of Egill contains clues to Paget's disease, and this is the first application of science, with the exclusion of archaeology, to the Icelandic sagas.

Here’s a reference to blindness.

Egil had a very bloody history. At times, he was marked for death, but his epic poetry, fit for kings, saved him. So words saved him, just like they have saved the Doctor time and time again.

“Egil” is another overloaded word, as its homophone is “eagle.” The Doctor is either a bird, being a proxy of Zeus, or Zeus, himself. Zeus’s Roman equivalent is Jupiter. In Norse mythology, Odin is the chief god. He’s not a one-to-one correspondence, though, to Zeus and Jupiter, like the typical Greek and Roman gods are to each other. Odin, among other things, is also a god of war like Mars. He’s a tyrannical leader who is not concerned with justice, and this sounds like Morbius, who may be the possessed Doctor.

Odin, too, was a shape-shifter and turned himself into an eagle. It’s one of his many disguises.

Valkyrie Has Multiple Meanings

The Martian probe Valkyrie, while probing the Martian ice caps, is named for multiple references.

Operation Valkyrie & “Let’s Kill Hitler”

Operation Valkyrie was a German plan during WWII to assassinate Hitler, take control of German cities, disarm the SS, and arrest the Nazi leadership. Although the participants made lengthy preparations, the plot failed. Of course, this also refers to the 11th Doctor episode “Let’s Kill Hitler,” where River was engineered to kill the Doctor. Of course, that lengthy plot failed, too, at least for the time being.

In “The Lie of the Land,” we saw the Doctor involved in a totalitarian government with the Truth logo, which looked like it could be a type of Nazi logo with an SS (mirrored Ss). Interestingly, Daleks were created as symbols of the Nazis.

Valkyries of Norse Mythology

In Norse mythology, valkyries are female figures who decide the fate of those who die in battle.

According to Wikipedia:

Selecting among half of those who die in battle (the other half go to the goddess Freyja's afterlife field Fólkvangr), the valkyries bring their chosen to the afterlife hall of the slain, Valhalla, ruled over by the god Odin. There, the deceased warriors become einherjar (Old Norse "single (or once) fighters"). When the einherjar are not preparing for the events of Ragnarök, the valkyries bear them mead. Valkyries also appear as lovers of heroes and other mortals, where they are sometimes described as the daughters of royalty, sometimes accompanied by ravens and sometimes connected to swans or horses.

Ravens and horses are certainly significant. In fact, ravens are indirectly referenced at least 4 times in the current story. We’ll examine more about the raven in a few minutes. And we’ll look at them in more depth in regards to Clara and the Doctor in the next chapter.

Valkyries today tend to be romanticized in a way, but in heathen times, they were more sinister and sound like they have a connection to the 12 Monks. According to Norse-Mythology.org:

The meaning of their name, “choosers of the slain,” refers not only to their choosing who gains admittance to Valhalla, but also to their choosing who dies in battle and using malicious magic to ensure that their preferences in this regard are brought to fruition. Examples of valkyries deciding who lives and who dies abound in the Eddas and sagas. The valkyries’ gruesome side is illustrated most vividly in the Darraðarljóð, a poem contained within Njal’s Saga. Here, twelve valkyries are seen prior to the Battle of Clontarf, sitting at a loom and weaving the tragic destiny of the warriors (an activity highly reminiscent of the Norns). They use intestines for their thread, severed heads for weights, and swords and arrows for beaters, all the while chanting their intentions with ominous delight. The Saga of the Volsungs compares beholding a valkyrie to “staring into a flame.”

The Norns sound very similar to the 3 Fates, which we examined in my analysis in TPEW, where I likened the Monks to weaving a tapestry and compared them to the 3 Fates who weave destinies. It seems likely then that the 12 Monks may symbolize the 12 Valkyries, who are weaving the tragic destiny to come.

Valhalla & the Cloister Wraiths

Valhalla is a the hall where the dead are deemed worthy of dwelling with Odin, and it’s located on Asgard, which brings in the references to the Doctor and River picnicking on Asgard. This picnic entry in River’s diary came up in “Silence in the Library,” as well as “The Husbands of River Song.”

Wolves guard Valhalla’s gates, and eagles fly above it.

According to Norse-Mythology.org:

Odin presides over Valhalla, the most prestigious of the dwelling-places of the dead. After every battle, he and his helping-spirits, the valkyries (“choosers of the fallen”), comb the field and take their pick of half of the slain warriors to carry back to Valhalla. (Freya then claims the remaining half.)

According to Norse-Mythology.org:

The dead who reside in Valhalla, the einherjar, live a life that would have been the envy of any Viking warrior. All day long, they fight one another, doing countless valorous deeds along the way. But every evening, all their wounds are healed, and they are restored to full health. They surely work up quite an appetite from all those battles, and their dinners don’t disappoint. Their meat comes from the boar Saehrimnir (Old Norse Sæhrímnir, whose meaning is unknown), who comes back to life every time he is slaughtered and butchered. For their drink they have mead that comes from the udder of the goat Heidrun (Old Norse Heiðrun, whose meaning is unknown). They thereby enjoy an endless supply of their exceptionally fine food and drink. They are waited on by the beautiful Valkyries.

But the einherjar won’t live this charmed life forever. Valhalla’s battle-honed residents are there by the will of Odin, who collects them for the perfectly selfish purpose of having them come to his aid in his fated struggle against the wolf Fenrir during Ragnarök – a battle in which Odin and the einherjar are doomed to die.

From what we’ve seen in “Hell Bent,” the Cloister Wraiths are, at least in one way, like the dead who reside in Valhalla. As the Doctor said, they are the dead manning the battlements. We may be experiencing the unreality of the symbolic Valhalla right now. The relative calm before the Ragnarök storm.

The Ice Queen Mirroring a Valkyrie or Odin

The Ice Queen, Iraxxa, decided who died and who lived, especially when it came to Colonel Godsacre. (God’s acre actually means “a churchyard or a cemetery, especially one adjacent to a church.”) Therefore, Iraxxa is mirroring a Valkyrie or even Odin, given her position of leader of the hive.

Odin, Ravens & the Valkyries

According to Wikipedia,

In Germanic mythology, Odin is a widely revered god. In Norse mythology, from which stems most of the information about the god, Odin is associated with healing, death, royalty, the gallows, knowledge, battle, sorcery, poetry, frenzy, and the runic alphabet, and is the husband of the goddess Frigg. In wider Germanic mythology and paganism, Odin was known in Old English as Wōden, in Old Saxon as Wōdan, and in Old High German as Wuotan or Wōtan, all stemming from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic theonym wōđanaz.

BTW, WOTAN is a reference to a 1st Doctor story called “The War Machines.” According to the TARDIS Wikia, “WOTAN was one of the first artificial intelligences created on Earth by Professor Brett. Its name stood for Will Operating Thought ANalogue.” It goes on to say, “Deciding to conquer the world, WOTAN ordered the construction of mobile, armed computers which were designated War Machines. These were constructed in locations across London.”

Anyway, according to WizardRealm.com:

Odin (or, depending upon the dialect Woden or Wotan) was the Father of all the Gods and men. Odhinn is pictured either wearing a winged helm or a floppy hat, and a blue-grey cloak. He can travel to any realm within the 9 Nordic worlds. His two ravens, Huginn and Munin (Thought and Memory) fly over the world daily and return to tell him everything that has happened in Midgard. He is a God of magick, wisdom, wit, and learning. He too is a psychopomp; a chooser of those slain in battle. In later times, he was associated with war and bloodshed from the Viking perspective, although in earlier times, no such association was present.

Interestingly, Odin has ravens. And this is another example of how “The Empress of Mars” has quite a few indirect references to ravens. Because Clara is associated with a raven, it brings up a reference to her, too. However, there are very pointed Clara references, which we’ll examine in the next chapter.

Being the god of magic, wisdom, wit, and learning, Odin has a lot in common with Merlin. Odin actually disguises himself as an old man and travels Midgard (Earth) looking for heroes for the coming of Ragnarök.

According to WizardRealm.com:

If anything, the wars fought by Odhinn exist strictly upon the Mental plane of awareness; appropriate for that of such a mentally polarized God. He is both the shaper of Wyrd and the bender of Orlog; again, a task only possible through the power of Mental thought and impress. It is he who sacrifices an eye at the well of Mimir to gain inner wisdom, and later hangs himself upon the World Tree Yggdrasil to gain the knowledge and power of the Runes. All of his actions are related to knowledge, wisdom, and the dissemination of ideas and concepts to help Mankind. Because there is duality in all logic and wisdom, he is seen as being duplicitous; this is illusory and it is through his actions that the best outcomes are conceived and derived. Just as a point of curiosity: in no other pantheon is the head Deity also the God of Thought and Logic. It's interesting to note that the Norse/Teutonic peoples also set such a great importance upon brainwork and logic. The day Wednesday (Wodensdaeg) is named for him.

It’s really interesting that Odin’s wars are fought on the “Mental plane of awareness.” This corresponds to the Doctor being a creature of pure thought through the Great Work. This also corresponds to him being a mirror of CAL, who is also a being of pure thought in a mental plane of awareness.

Odin & the Doctor

In “The Girl Who Died,” the Doctor pretended to be Odin when the Vikings took him and Clara captive. We then saw another extraterrestrial claiming to be Odin, shown below. His helmet is obviously symbolic in some ways of a bird. Are the wings those of an eagle or a raven? There are symbolic feathers on the top of the helmet, too, but that’s where the similarities to a bird end.

The crest looks more like something a Roman soldier would wear on his helmet. And then there’s the weird part covering his forehead that looks like 2 eyes and a nose. Is the representation supposed to be 2 faces in One? The symbolic eyes are empty, perhaps, representing The Ghost. Odin is a dark mirror of the Doctor, and it seems to me from the symbolism that Odin represents the possessed Doctor, who has an augmented eye. That could be a reference to the Eye of Harmony.

The Doctor actually does more than just pretend to be Odin in this episode. Like Odin in mythology, the Doctor decides life and death here. He assumes Odin’s role. Ashildr dies, and the Doctor literally brings her back to life, another signal of the coming of Ragnarök. Clara represents a valkyrie, the Doctor’s helping spirit.

But this isn’t all. Extraterrestrial (ET) Odin in “The Girl Who Died” has a connection to the “Robot of Sherwood.” The sheriff’s boar emblem looks very much like ET Odin’s helmet when placed behind someone’s head. Check out this image below of the arrow bearer in this perfectly centered camera shot where the emblem of the boar’s ears (yellow arrow) now looks like the wings on Odin’s helmet.

In fact, the sheriff looks a lot like Odin without the helmet.

Interestingly, we have seen a character in TRODM, Lucy Fletcher, whose name means arrow maker or to furnish (an arrow) with a feather. Through all the mirrors we’ve examined, she connects to Amy, who connects to River. Susan connects to River, too. And River may connect to Missy. We know Missy has been controlling the Doctor through Clara, and she’s running a con game now.

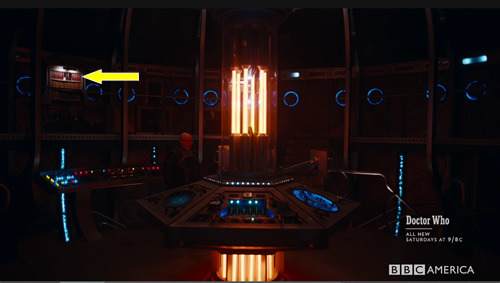

Who’s Behind Controlling the TARDIS?

Check out the image below in the darkened TARDIS when Nardole goes to get some gear to help Bill after she falls into the pit. The bookcase is lit, which is very abnormal. And it’s only one bookcase in particular. This indicates it’s River.