#louis froissart

Text

I was looking at reviews of Lucy Freeman Sandler's study of the Lichtenthal Psalter and it just made me Feel Things™, in terms of looking back at the past and seeing the imprint of something so human.

Brief Primer: The Lichtenthal Psalter is believed to have been commissioned by Joan de Bohun (nee Fitzalan) for her daughter, Mary, on occasion to her marriage to the future Henry IV in 1380/1381. It is now located in Cistercian convent of Lichtenthal in Germany and it is generally believed that it came to Germany with Mary's daughter, Blanche, when she married Louis, Elector Palatine, in 1402, before being passed to the convent by her husband's great granddaughter in 1503. On a related note, there are two de Bohun manuscripts in Copenhagen's Det kongelige Bibliotek that are generally believed to have come to Denmark with Mary's other daughter, Philippa, on occasion of her marriage to Eric of Pomerania, but the provenance of the manuscripts in Denmark doesn't date far enough (iirc, it only goes back to the 17th or 18th century) to confirm that belief.

Already that makes me emotional - the book that was made for 10-year-old Mary's marriage accompanying her 10-year-old daughter on her marriage, who had been two when Mary died.

From Maidie Hilmo's review in Medieavistik, Vol 20 (2007):

This study has uncovered a number of fascinating thematic in the illustrations of the biblical narratives in the Lichtenthal Psalter. An example concerns the intended female recipient of this book. In the illustrations considerable emphasis is placed on birth scenes, while an effort is made to censor scenes such as Noah's nakedness.

And Lydia Dennisson's review in Speculum, vol. 81, no. 3 (2006):

Conversely, Sandier has discovered that the artists, principally [John de] Tye, "edited" the text so that biblical episodes perceived to be especially significant coincide with the main textual divisions: a scriptural image may be used to reinforce a topical point and the topical image, in turn, comment on the scriptural. She speculates as to whether in his selection John de Tye may have had a particular focus; for instance, there are several prominent scenes of childbirth, and any scenes that might be perceived as negative, or derogatory to women, are omitted.

Like! The thought and care that went into tailoring the book to be make potentially appropriate for a 10-year-old girl! The censoring of Noah's junk! The editing out of scenes derogatory to women! It just feels so human. Whether this was a typical adjustment for if the intended reader was young and/or female, John de Tye's specific intervention or because of specific instructions from the book's commissioner (Joan) is unrecoverable, I imagine, but I like to imagine that it came from Joan, specifically, and love the image of her standing over them to make sure that they do what she says.

I don't have the book (yet) to check what Sandler says about Noah's junk being censored but in the context of Froissart's claim that Mary's marriage to Henry was "instantly consummated"... I feel Froissart's claim is likely not referring to sexual consummation, or if it was, it wasn't true. At the very least, it indicates that Joan did not want Mary exposed to dicks in art, much less in real life, at this age.

(also: if the psalter was finished by the time of Mary's wedding and was made at the manuscript workshop at Pleshey - one of Thomas of Woodstock's principle residences - which seems to be likely, this suggests that this wasn't as secretive as Froissart depicts.)

Hilmo:

The pictorial program begins with a calendar illustrating the Labours of the Months and the signs of the zodiac. Sandler points out that a visual topos for adolescence is transferred to a zodiacal context in the illustration for Virgo, which depicts "a sun shining over a girl combing her hair while looking in a mirror" (131). It is part of this author's restraint that she allows the reader to make the observation that this might have been one of the ways in which this manuscript was personalized for Mary de Bohun.

I don't have any commentary here but it's just..so... 🥺Just the thought and care going into customising it?

Hilmo:

In the bottom of the Beatus page, echoing the Creation scenes at the top, Eve bears Abel in a cave-like setting beside heraldic displays in the border. In historiated initials, fruit- fulness is also given prominence in connection with the births of Esau, Jacob, and Moses.

Since this psalter was commissioned by Mary de Bohun's mother, Joan Fitzalan, at the time of Mary's marriage, it is suggested that such scenes in this psalter were to prepare the young girl for the desired outcome of her marriage and to serve educational as well as spiritual purposes. Sandler states that the armorial displays "proclaim the connection of all the Bohuns - past and present - with kings and princes, a view of the high estate of the family that commissioner and artist hoped to transmit."

As someone who imagines Mary as especially fulfilled by motherhood, this is so, so interesting to know. Like, yes, it's a bit... eh in terms of imagining Mary as a girl/woman that must have children but it was the norm/expectation for married women. But it does help suggest how Mary would have initially imagined and then framed her experiences of motherhood which is so useful.

Also, the focus on the lineage is very interesting in the context of Blanche's only known son who was nicknamed "the English".

Anyway I cracked and ordered the book for myself as a belated Christmas present.

#joan de bohun countess of hereford#mary de bohun#henry iv#blanche of england#blog#manuscripts#the lichtenthal psalter#bohun manuscripts

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis-Antoine Froissart (French, 1815–1860)

Flood in Lyon ,1856

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

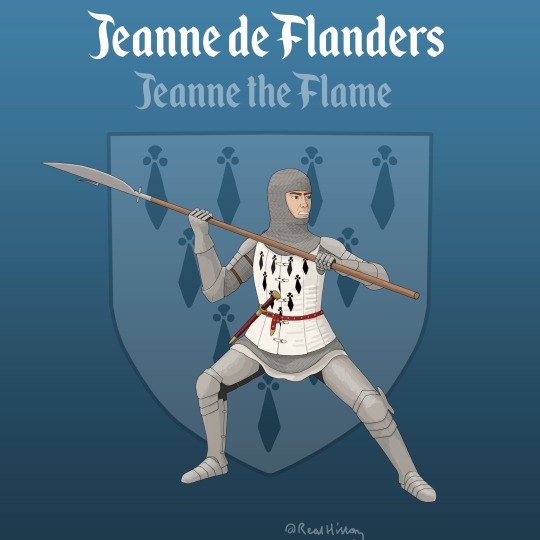

Jeanne de Flanders was the Duchess of Brittany in the 14th century.

Her husband, John de Montfort, was the son of Duke Arthur II of Brittany and the half-brother of John III.

When his brother died without a male heir, de Montfort resorted to military force to make his claim to the Duchy in the War of Breton Succession.

When her husband was imprisoned by King Philip VI of France, Jeanne declared their infant son the leader of the Montfort cause. She raised an army and marched to the town of Hennebont.

Charles of Blois besieged the town in 1342. Jeanne herself commanded the defence of the town, dressed in armour and fully armed.

At one point, she observed from a tower that Charles’ camp was lightly guarded, so she led 300 men in an assault on the camp. They destroyed supplies and burned down many tents. The besiegers attempted to cut her off from the city, so she and her men rode to Brest instead. In Brest, she gathered more soldiers, slipped out and into Hennebont with a force larger than she is left with.

As a result, she became known as Jeanne la Flamme or Jeanne the Flame.

The siege was eventually lifted after the arrival of English reinforcements. Jeanne herself later sailed to England to seek further aid from King Edward.

When her fleet was attacked en route by Louis of Spain, Jeanne led the defence of her ship against a boarding action while wielding a sharp glaive.

By 1345, the Montfort cause in Brittany was essentially taken over by the English.

That same year, Edward had Jeanne confined at in England. It was said the reason for her confinement was that she had become insane, but there is no evidence for this. It is more likely that Edward wanted to more firmly secure Brittany under his power.

She spent the rest of her life in captivity, living long enough to see her son become Duke John IV of Brittany before she died in 1374.

Jeanne de Flanders is a member of the relatively small club of identifiable female individuals who fought in combat. The chronicler Jean Froissart commented that she “had the courage of a man and the heart of a lion.”

Scottish philosopher David Hume described her as the “most extraordinary woman of her age.”

#history#real history#military history#medieval#middle ages#medieval history#medieval europe#warrior#warrior women#powerful women#historical women#woman#warrior woman#women

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joanna of Flanders - “Fiery Joanna”

Joanna of Flanders (b. c.1295 - after 1373) was the daughter of Louis de Nevers, count of Flanders. The heiress of a powerful family, she married in 1329 John of Montfort, half-brother to the duke of Brittany. Said duke died in 1341 without a direct descendant and a war of succession began between John of Montfort and Jeanne of Penthièvres, niece of the deceased duke, who was backed by her husband Charles de Blois. Both factions were supported by the crowns of England and France respectively.

Joanna appears to have been a supporter of her husband’s military maneuvers. In 1341, they occupied Nantes and Rennes and secured the duchy’s treasury. However, it was after John of Montfort was captured that Joanna came to shine as a military leader. She organized the defense of her lands and secured an alliance with Edward III of England. Her most celebrated feat took place when she defended Hennebont as the town was besieged by the troops of Charles de Blois in may 1342.

Jean Le Bel’s describes Joanna in his True Chronicle:

“The valiant countess, armed and riding a great charger from street to street, was cheering and summoning everyone to the city’s defence, and commanding the women of the town, ladies and all, to take stones to the walls and fling them at the attackers, along with pots of quicklime.”

She then personally led an attack on the French camp:

“And now you shall hear of the boldest and most remarkable feat ever performed by a woman. Know this: the valiant countess, who kept climbing the towers to see how the defence was progressing, saw that all the besiegers had left their quarters and gone forward to watch the assault. She conceived a fine plan. She remounted her charger, fully armed as she was, and called upon some three hundred men-at-arms who were guarding a gate that wasn’t under attack to mount with her; then she rode out with this company and charged boldly into the enemy camp, which was devoid of anyone but a few boys and servants.They killed them all and set fire to everything: soon the whole encampment was ablaze.”

This action led her to be nicknamed “Jeanne la Flamme / Fiery Joanna”. Alarmed, the besiegers went back to their camp. Realizing that there was no way to go back to the city, Joanna rallied her men and left for the castle of Brayt. The enemy gave chase and managed to kill some of her retainers, but Joanna escaped with most of her troops.

Joanna planned to return. She gathered 500 well equipped men, left Brayt during the night and arrived to Hennebont at dawn. She then entered the city to a “triumphant blast of trumpets and drums and other instruments”.

English reinforcements later came and the city was saved. This was to be Joanna’s last active part in the war. Froissart extend Jean Le Bel’s account and wrote that Joanna fought actively, sword in hand, during a naval battle. It, however, seems that he confused or conflated two naval battles.

Joanna left for England with her two sons in 1343. She was to never see Brittany again since she was confined to a castle in England. It had been alleged that it was because she had become mentally ill, but a more convincing hypothesis could be that she represented a threat to Edward III who wanted to gain control over her lands.

Interestingly, the leader of the opposite faction, Jeanne de Penthièvres (c.1320-1384), also took the head of the operations after her husband was captured. This is why this war was later nicknamed “The war of the two Jeannes”. In 1347, she took in hand the military leadership and administration of the duchy and organized the defense of her lands against the English in 1354-1355. Though reports and her presence on the field may have been apocryphal, she still proved an competent military leader.

Here’s the link to my Ko-Fi if you want to support me.

Bibliography:

Jean Le Bel, True Chronicle

Evans Michael, “Jeanne de Montfort”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.1

Evans Michael, “Jeanne de Penthièvres”, in: Higham Robin, Pennington Reina (ed.), Amazons to fighter pilots, biographical dictionary of military women, vol.1

Sarpy Julie, Joanna of Flanders, heroine and exile

#historyedit#Joanna of flanders#history#women in history#jeanne de penthièvres#warrior women#middle ages#badass women#14th century#france#french history#historyblr#medieval history#medieval women#women in armor#moodboard#history mooboard#aesthetic

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

The campaign of propaganda against Valentina Visconti

Irritated by her sister-in-law's calming effect upon the troubled king (while she was rebuffed frequently by him), it seems that Isabeau set to besmirching Valentina's good reputation. Valentina was Italian, and, "as everyone knew", Italy was a nation of poisoners and sorcerers. Charles's illness was reinterpreted; no longer a judgement upon the behavior of his uncles or the misgovernment of his advisers, the unfortunate king was recast as the victim of Valentina's sorcery and enchantment. A rumor started to circulate to the effect that Valentina had bewitched the king; she was the cause of his illness and the obstacle to its cure. As it was rumor there was no need to prove such a claim; its mysterious nature bilked direct proof or formal demonstration, and Valentina's enemies were able to condemn her without a tribunal. To this a concomitant rumor was pressed into service: the classic tale of a poisoned apple and the death of a little prince. Valentina's enemies leapt into the fray to exploit the sad death of her young son Louis in September 1395. It was whispered that she had planned to remove the young dauphin but that instead her own son, who was playing with the other royal children, ate the tainted fruit and died of poisoning. The story was picked up by Froissart, keen to deride a woman whom he believed to be ambitious with aspirations above her station.

Ambitious Valentina is a them that crops up from this time and one that Jean the Fearless of Burgundy recycled on the occasion of his Justification for the murder of Orleans. It was a "known fact" (the rumor reported) that upon Valentina's departure from Milan to marry Louis of Orleans, her father, Giangaleazzo, bid her a fond farewell with the words: "Adieu, belle fille! je ne vous vueil jamais veoir tant que vous soyez royne de France." (Good-bye, beautiful daughter! I do not expect to see you again until you are queen of France!) [..]

Initiated by the rumor of evil spells linked to and fueled by the "known" sorcery habits and nefarious aspirations of Valentina's father, Isabeau's bespoke campaign of propaganda against her sister-in-law aimed to remove Valentina's considerable potential for influence by ensuring that she would have no further personal contact with the king, the princes, the people, the conduct of the business of the kingdom, or to take any action which might be contrary to Isabeau's projects and ambitions. Valentina was to be disloged from court, distanced from Paris, and relegated far beyond the center of political decision making. With Isabeau's campaign, Valentina was reduced to powerlessness and separated from the royal family and her allies. Eugène Jarry expresses well Isabeau's strategy:

"Isabeau did not forget the duchess of Orleans' influence over the mind of the king. Her plan was mapped out: it was absolutely necessary to remove the daughter of the duke of Milan. This outcome was achieved by the most cowardly of schemes. The outburst of negative public opinion against Valentina was too precise not to have been stirred up by interested parties."

Here Jarry links public opinion to interested parties. Isabeau was not the only interest party; the house of Burgundy carried its share of responsibility even though Burgundy was content enough to allow Orleans to divert himself with his Italian dreaming. Philippe was cordial and welcoming to Valentina, but his political reality dictated that he needed to work toward removing Orleans from all participation in government. Burgundy's wife, Marguerite of Dampierre, countess of Flanders, was of a mind to assist Isabeau in blackening Valentina's reputation. In taking control of the government in the wake of Charles's first episode of insanity, Burgundy had positioned Marguerite to steer the young queen in the interests of their House. From 1392, Marguerite jealously guarded her pre-eminent position in Isabeau's court, and no one could gain access to the queen without her consent.

[..]

Collas claims that Marguerite had been greatly put out by Valentina's arival and her subsequent drop in status; she was henceforth the middle-aged sister in law of the defunct king while Valentina was the cherished younger sister-in-law of the current king.

The mud stuck and, for her own safety, Orleans removed Valentina from court. Froissart records that such were the murmurings of the public that had Valentina not withdrawn she might have been attacked and lynched by a Parisian mob that believed she meant to poison the king and his children.

Zita Eva Rohr- True Lies and Strange Mirrors: the Uses and Abuses of Rumor, Propaganda and Innuendo During the Closing Stages of the Hundred Years War, in Queenship, Gender and Reputation in the Medieval and Early Modern West

#xiv#zita eva rohr#true lies and strange mirrors#isabeau de bavière#queens of france#charles vi#valentine visconti#louis i d'orléans#giangaleazzo visconti#jean i de bourgogne#marguerite de dampierre#armagnacs vs bourguignons#hundred years war#reputation and propaganda

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medieval Fashion... for Pets!

From John Block Friedman, ‘Coats, Collars, and Capes: Royal Fashions for Animals in the Early Modern Period’ (2016)

Illumination from Livre de la chasse by Gaston de Foix (c. 1406–1407)

Prosperous social groups owned a variety of pets in the Middle Ages: dogs, cats, birds, squirrels, rabbits, hares, deer, badgers, smaller monkeys, marmots, and even bears. Keeping pets was largely due to ostentation, signifying that the owner had room, food, and staff to care for them. Small pet accessories such as ornate protective bed coverings, cushions, jewelled dog collars, monkey harnesses and mobility-restricting blocks, gilt chains and embroidered muzzles for bears, and birdcages and cage coverings symbolised the plenitude of material assets and luxurious household goods, thus emphasising the pet owners’ elevated social status.

Though simple ostentation of this sort undoubtedly was a factor in medieval pet ownership, the proliferation of costly animal accessories also played a significant important role in the material culture of vivre noblement: the continual display of wealth through conspicuous consumption. 15th century Northern Europeans’ love of texture, rich colours, metal-fabric-jewel mixtures, furs, and identity-expressing badges were used as insigniae to identify the wearer’s social status or role as part of a noble retinue.

The keeping and display of pets and their accessories therefore constituted a distinct form of medieval material culture, whereby fashion for animals was an additional means to extend and assert the pet owner’s identity in society.

Accessorising the Medieval Dog:

Detail from Le Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (c. 1416)

Late medieval dogs were just as “doggy” as they are today. Fashion for dogs was frequently depicted in art and noted in royal expense accounts through payments for collars. Household dogs usually wore daily leather or fabric collars supporting small bells, or wider textile or fabric-covered leather collars ornamented with the owner’s heraldic arms, insigniae, and personal mottoes through metal mounts or embroidery. By contrast, purely decorative fabric collars for special occasions were often constructed of jewelled velvet, and reflected the prevailing taste for silk, gold and silver thread, rich colours, and solid metal and jewel ornamentation characteristic of late medieval Northern Europe. The use of velvet, in particular, was confined by medieval sumptuary laws to certain classes of people defined by their socioeconomic level and noble status as nobility by birth.

The nobility thus paid great attention to such textile and metal collars for their dogs — and at great expense. In 1420, Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, ordered a crimson velvet greyhound collar with two gold escutcheons bearing his arms. Embroidered in letters composed of tiny pearls was his motto “moult me tarde” (“much delays me”). In 1463, King Louis XI of France ordered from the goldsmith Jacques de Chefdeville a lavish gold collar for his greyhound, Chier (’Dearie’), comprised of:

“ten segments hinged with crimped gold wire, a buckle and its tongue, a tab, four other [protective] spikes set in downward curving leaves, fifty bosses, fifty rivets, three studs and three rivets. … And in copper settings ten large spinels, twenty pearls, one ruby, one jacinthe, and one crystal panel the said king has provided. And also foil placed beneath the said spinels, ruby and jacinthe to give them better colour.”

This cost 246 livres, 12 sous, and 8 deniers, in addition to 55 sous, 1d for “a quarter-yard of crimson velvet for a lining, doubled under the collar” as the first one was not rich enough to please the king. For comparison, the noted bibliophile Louise de Savoie, Countess of Angoulême, paid her court manuscript illuminator 35 livres tournois in 1496 for his wages for a year; thus, Chier the greyhound’s collar cost almost seven years’ wages for a highly skilled artist. The mixture of precious metals, gems, pearls, and textiles in these canine collars was perfectly in keeping with the fabrics and colours most sought-after by medieval nobles and courtiers. With respect to their collars, then, Philip’s and Louis’ greyhounds looked like favoured human members of their entourages.

That such dog collars were open assertions of noble identity is clear from written and pictorial sources. Louise de Savoie’s expense accounts in 1454 show a payment of 34s, 4d for eight copper collar escutcheons bearing her arms, intended for her hunting greyhounds. This suggests that Louise felt the need to extend her identity into the animal realm, ensuring that her name touched every aspect of nature as her dogs pursued her deer through her woods. Ornate dog collars were also depicted in Flemish tapestries, where owners’ initials and mottoes were woven into the art. For example, the famous La Chasse à la licorne tapestries show the letters “AE” (the monogram of the person who commissioned them) embroidered on the collars of the hunting dogs.

Detail showing monogram on dog collar, from the third tapestry in the La Chasse à la licorne tapestry series (c. 1495-1500)

Dressing the Animal Body:

The evidence for late medieval animal livery is fairly considerable. Such garments appear for dogs, monkeys, bears, and even a marmot. In some cases, the garments were intended to provide warmth. In 1455, Marie de Cleves, Duchess of Orléans ordered five such jackets (“habil-lements”) for her greyhounds. The accounts of King Charles VIII of France — a noted pet owner — also mention a payment during the winter for a quarter-aune of bright green (“gay vert”) wool to make a warming jacket for a very small lapdog.

In other cases, the garments were intended to assert the owner’s identity. The giving and wearing of livery was a distinctively medieval phenomenon and a major component of the vivre noblement ethos; in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the custom was quickly adapted to putting animals in the livery of their owners, as was the case with horse trappings. The wearing of livery was closely tied to identity assertion and affirmation: “Lords took to clothing their followers in similar colours or styles of dress to impress those outside their households and to emphasise their authority” (Benjamin Wild). Animal livery was intended to express the power of the lord and his “civilising” force over the animal world, as well as his continuing and magnificent consumption of commodities.

Detail of a greyhound wearing a cape emblazoned with the French fleur de lis, from the illumination ‘Isabella arrives in Paris’ in Jean Froissart’s Chroniques (15th century)

Garments ordered by nobles for their pets are often itemised in the expense accounts of the royal households of France. Perhaps the most extreme example of pet livery occurs in the 1492 wardrobe expenses of Charles VIII’s queen, Anne de Bretagne, whose twenty-four dogs — including nine greyhounds — each had a personal servant. The dogs all wore matching black velvet collars, with four dangling ermine paws reflecting the Duchy of Brittany’s coat of arms. By this period in Europe, a deep black had become so stylish a colour that black velvet was Genoa’s single biggest export in the 16th century; “because plain black velvet enjoyed the advantage of displaying wealth without ostentation, it was deemed equally appropriate for a ruler or his smartly liveried servants” (Lisa Monnas). Thus, Anne ensured that her twenty-four dogs, being important members of her household, were fashionably garbed in the new colour — just as her courtiers were. Even as mundane a pet as the hare could wear this fabric: the accounts of King Charles VII of France show that Queen Marie d’Anjou paid “for a quarter aune of black velvet with [deluxe] triple pile to cover two leather collars that the said lady had had made, to put on the necks of two hares that she had raised for her pleasure.”

Detail of insects and two hares from the Cocharelli codex (c. 1330-1340)

Source: John Block Friedman, ‘Coats, Collars, and Capes: Royal Fashions for Animals in the Early Modern Period’ in Medieval Clothing and Textiles 12 (2016)

#medieval furbabies!#the real article is 35 pages long so i cut/edited it down so y'all can read about medieval fur babies#medieval#pets

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Willing to bet this is who Adam’s playing in The Last Duel. He’s too young to play Jean of Berry, Philip the Bold, or Jean Froissart, and he’s too old to play Louis of Valois...or at least I would have thought so if I hadn’t remembered that Ben Affleck is playing the historically eighteen-year old Charles VI, so who knows at this point.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Great Big Reading List

Here it is! These are the books that I’m trying to read this summer - in the future, some of them could be part of an exam reading list, but that is to be fully and officially built at a later date. I do not necessarily anticipate finishing this list in its entirety, but it’s got a whole lot of fairly different works on it.

I made it along a couple themes, just to narrow down my choices - very generally they were violence, war, bodies, and identity. I also added some that I was just interested in (see a few in the 18th and 19th centuries).

Not all of these have been easy to find online or in paper!

A final warning because Saint-Cyr and de Sade are both on there - be careful with those two books and be sure you want to read them prior to doing so - looking at their descriptions and being aware of de Sade, they deal with a lot of brutality. These aren’t really the kind of thing you’d read on a whim.

***Note that while reading over the summer before grad school is great, there is no actual requirement for doing so in most cases (in the US, at least as far as I know).***

Medieval

La Chanson de Roland

Lancelot (Charrette) - Chretien de Troyes

La Folie d'Oxford - Béroul

Erec et Enide - Chretien de Troyes

La Mort le roi Artur - (from the Vulgate-Grail, I think?)

Aucassin et Nicolette

Le Livre du voir dit - Guillaume de Machaut

La Prison amoureuse - Jehan Froissart

Le Livre de la cité des dames - Christine de Pizan

Le Petit Jehan de Saintré - Antoine de la Sale

Les Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles

Le Charroi de Nimes

16th Century

Les Tragiques - Agrippa d'Aubigné

Discours des misères de ce temps - Pierre de Ronsard

Histoires tragiques - Francois de Belleforest

Abraham sacrifiant - Théodore de Bèze

Lepante - Guillaume de Salluste du Bartas

la "Monomachie de David et de Goliath" - Joachim du Bellay

Porcie - Robert Garnier

La Rochelleide - Jean de la Gessée

Illustrations de Gaule et Singularitez de Troie - Jean Lemaire de Belges

Discours de la servitude volontaire - Etienne de la Boétie

Médée - Jean de La Péruse

Pantagruel - Francois Rabelais

17th Century

Oeuvres poétiques - Theophile de Viau

Le cid - Corneille

Andromaque, Phèdre, et Britannicus - Racine

Contes - Charles Perrault

Les Aventures de Télémaque - Fénelon

La Mort d’Achille, La Mort d'Alexandre, Coriolan - Alexandre Hardy

Dom Juan - Molière

18th Century

Le Diable amoureux - Jacques Cazotte

Le Paradox sur le comedien - Denis Diderot

La dispute - Pierre de Marivaux

L'Esprit des lois - Charles Louis de Secondat Montesquieu

Pauliska, ou la Perversité moderne - Jacques-Antoine de Reveroni Saint-Cyr*

Aline et Valcour - Donatien Alphonse Francois de Sade*

L'emigré - Gabriel Senac de Meilhan

Paul et Virginie - Bernardin de Saint-Pierre

Memoires du Comte de Comminge - Claudine-Alexandrine Guerin Tencin

Traité sur la tolerance - Voltaire

19th Century

Atala - Chateaubriand

La Chartreuse de Parme - Stendhal

La fille aux yeux d'or - Balzac

Lorenzaccio - Musset

Le Dernier Jour d'un condamné - Victor Hugo

La Sorcière - Michelet

Carmen - Merimée

La Morte Amoureuse - Gautier

Les fleurs du mal - Baudelaire

Les Diaboliques - Barbey d'Aurevilly

Boule-de-Suif / Mademoiselle Fifi - Maupassant

Les Chants de Maldoror - Leautreamont

Igitur - Mallarme

20th Century

Cahier d'un retour au pays natal - Césaire

Traversée de la mangrove - Condé

Les Bonnes - Jean Genet

Antigone - Anouilh

La femme de Job - Chedid

Nedjma - Kateb Yacine

Le Cimetiere marin - Valéry

La route des Flandres - Simon

Stèles - Segalen

La condition humaine - Malraux

La Guerre de Troie n'aura pas lieu - Giradoux

Le dimanche de la vie - Queneau

#sophie creates a reading list#long post#if you're newer to the french language i'd suggest starting with the 20th century works#simply because the language is not as wildly complex#and if you want to read some of the med/ren ones id suggest plays#feel free to ask me qs about this bc while i have not read all the works#i did do at least some research on them as i was putting them on here#was somewhat hesitant abt posting w the st cyr + de sade books#but i'm here to be realistic#and they do both technically fit the themes#im not reading justine bc im not sure i could deal with that book#also lol can u tell im not the biggest fan of 17th century lit

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artifact Series J

J. Allen Hynek's Telescope

J. Edgar Hoover's Tie

J. McCullough's Golf Ball

J. Templer's Wind-Up Tin Rooster *

J. C. Agajanian’s Stetson

J.T. Saylors's Overalls

J.M. Barrie’s Swiss Trychels

J.M.W. Turner's Rain, Steam and Speed-The Great Western Railway *

J.R.R. Tolken's Ring

Jack-in-the-Box

Jack's Magic Beanstalk

Jack Daniel's Original Whisky Bottle

Jack Dawson's Art Kit

Jack Duncan's Spur *

Jack Frost's Staff

Jack Kerouac's Typewriter

Jack Ketch's Axe

Jack LaLanne's Stationary Bike *

Jack London's Dog Collar

Jack Parson's Rocket Engine

Jack Sheppard's Hammer

Jack Sparrow's Compass

Jack Torrance's Croquet Mallet

Jack the Ripper's Lantern *

Jackie Robinson's Baseball

Jackson Pollock's "No. 5, 1948"

Jackson Pollock's Pack of Cigarettes

Jackson Pollock's Paint Cans

Jack's Regisword

Jack Vettriano's "The Singing Butler"

Jack's Wrench

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm's Kinder- und Hausmarchen

Jacob "Jack" Kevorkian's Otoscope

Jacob Kurtzberg's Belt *

Jacqueline Cochran's Brooch

Jacques Aymar-Vernay’s Dowsing Rod

Jacques Cousteau's Goggles

Jacques Cousteau's Diving Suit

Jacques-Louis David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps *

Jade Butterfly

Jadeite Cabbage

Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar's Smoke Pipe

Jamaica Ginger Bottle

Jaleel White's Hosting Chair

James Abbot McNeill Whistler's Whistler's Mother *

James Allen's Memoir

James Bartley's Britches

James Ben Ali Haggin's Leaky Fountain Pen

James Bert Garner’s Gas Mask

James Bett's Cupboard Handle

James Braid's Chair *

James Brown's Shoes

James Bulger's Sweater

James Buzzanell's Painting "Grief and Pain"

James Buzzanell’s Survey Books

James C. McReynolds’ Judicial Robe

James Chadwick's Nobel Prize

James Clerk Maxwell's Camera Lens

James Colnett's Otter Pelt

James Condliff's Skeleton Clock

James Cook's Mahiole and Feather Cloak

James Craik's Spring Lancet

James Dean's 1955 Prosche 550 Spyder, aka "Little Bastard"

James Dean's UCLA Varsity Jacket

James Dinsmoor's Dinner Bell

James Eads How’s Bindle

James Earl Ray's Rifle

James Fenimore Cooper's Arrow Heads

James Gandolfini's Jukebox

James Hadfield’s Glass Bottle of Water

James Hall III’s Shopping Bags

James Henry Atkinson's Mouse Trap

James Henry Pullen’s Mannequin

James Hoban's Drawing Utensils

James Holman’s Cane

James Hutton's Overcoat

James Joyce’s Eyepatch

James M. Barrie's Grandfather Clock

James M. Barrie's Suitcase

James Murrell's Witch Bottle

James Philip’s Riata

James Prescott Joule's Thermodynamic Generator

James Smithson's Money

James Tilly Matthews’ Air Loom

James Warren and Willoughby Monzani's Piece of Wood

James Watt's Steam Condenser

James Watt's Weather Vane

James W. Marshall’s Jar

Jan Baalsrud’s Stretcher

Jan Baptist van Helmont's Willow Tree

Jane Austen's Carriage

Jane Austen's Gloves

Jane Austen's Quill

Jane Bartholomew's "Lady Columbia" Torch

Jane Pierce's Veil

Janet Leigh's Shower Curtain

Janine Charrat's Ballet Slippers

Jan Janzoon's Boomerang *

Janis Joplin's Backstage Pass from Woodstock *

Jan Karski's Passport

Janus Coin *

Jan van Eyck’s Chaperon

Jan van Speyk's Flag of the Netherlands

Jan Wnęk's Angel Figurine

Jan Žižka's Wagenburg Wagons

The Japanese Nightingale

Jar of Dust from the Mount Asama Eruption

Jar of Greek Funeral Beans

Jar of Marbles

Jar of Molasses from The Boston Molasses Disaster

Jar of Sand

Jar of Semper Augustus Bulbs

Jar of Shiva

Jar of Sugar Plums

Jascha Heifetz's Violin Bow

Jason Voorhese's Machete

Javed Iqbal's Barrel of Acid

Jay Maynard's Tron Suit

Jean II Le Maingre's Gauntlets

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau’s Cradleboard

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin's Bubble Pipe

Jean Chastel's Silver Gun

Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin's Pocket Watch

Jean Fleury's Aztec Gold Coins

Jean-François Champollion’s Ideographic Dictionary

Jean Froissart's Mirror *

Jean-Frédéric Peugeot's Pepper Mill

Jean Hilliard’s Earmuffs

Jean Parisot de Valette’s Sword Sheath

Jean-Paul Marat's Bathtub

Jean Paul-Satre’s Paper Cutter

Jean-Pierre Christin's Thermometer

Jean Senebier's Bundle of Swiss Alpine Flowers

Jean Valnet's Aromatherapy Statue

Jean Vrolicq’s Scrimshaw

Jeanne Baret's Hat

Jeanne de Clisson's Black Fleet

Jeanne Villepreux-Power's Aquarium

Jeannette Piccard's Sandbag

Jeff Dunham's First Ventriloquist Box

Jefferson Davis' Boots

Jefferson Randolph Smith's Soap Bar

Jeffrey Dahmer's Handkerchief

Jeffrey Dahmer's Pick-Up Sticks

Jemmy Hirst's Carriage Wheel

Jenny Lind's Stage Makeup

Jeopardy! Contestant Podiums

Jerome Monroe Smucker's Canning Jars

Jerry Andrus’ Organ

Jerry Garcia's Blackbulb *

Jerry Siegel's Sketchbook

Jesse James' Saddle

Jesse James' Pistol

Jesse Owens' Hitler Oak

Jesse Owens' Running Shoes

Jesse Pomeroy's Ribbon and Spool

Jester's Mask

Jesus of Nazareth's Whip

Jesús García's Brake Wheel

Jet Engine from the Gimli Glider

Jet Glass Cicada Button

Jethro Tull's Hoe

Jeweled Scabbard of Sforza

Jiang Shunfu’s Mandarin Square

Jim Davis' Pet Carrier

Jim Fixx's Shorts

Jim Henson's Talking Food Muppets

Jim Jones' Sunglasses

Jim Londos' Overalls

Jim Robinson's Army Bag

Jim Thorpe's Shoulder Pads

Jim Ward's Piercing Samples

Jimi Hendrix's Bandana

Jimi Hendrix's Bong

Jimi Hendrix's Guitars *

Jimmie Rodgers Rail Brake

Jimmy Durante's Cigar

Jimmy Gibb Jr's Stock Car

Jimmy Hoffa's Comb

Jin Dynasty Chainwhip

Jingle Harness

Joan II, Duchess of Berry's Dress

Joan of Arc's Chain Mail

Joan of Arc's Helmet (canon)

Joan Feynman's Ski Pole

Joanna of Castile's Vase

Joan Rivers' Carpet Steamer

Joan Rivers' Red Carpet

Joe Ades's Potato Peeler

Joe Girard’s Keys

Joe Rosenthal's Camera Lens

Joel Brand's Playing Cards

Joséphine de Beauharnais' Engagement Ring

Johan Alfred Ander’s Piece of Porcelain

Johann Baptist Isenring’s Acacia Tree

Johann Bartholomaeus Adam Beringer's Lying Stones

Johann Blumhardt's Rosary

Johann Dzierzon’s Beehive Frame

Johann Georg Elser's Postcard

Johann Maelzel's Metronome *

Johann Rall's Poker Cards

Johann Tetzel's Indulgence

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Prism

Johannes Brahms' Coffee Creamer

Johannes Diderik van der Waals' Gloves

Johannes Fabricius' Camera Obscura

Johannes Gutenburg's Memory Paper *

Johannes Gutenburg's Printing Press *

Johannes Gutenberg's Printing Press Keys

Johannes Kepler's Planetary Model

Johannes Kepler's Telescope Lense

Johannes Kjarval’s Landscape Painting

John A. Macready's Ray-Bans *

John A. Roebling's Steel Cable

John A.F. Maitland's Musical Brainnumber *

John André’s Stocking

John Anthony Walker's Minox

John Axon's Footplate

John Babbacombe Lee’s Trapdoor

John Bardeen's Radio

John Bodkin Adams’ Stethoscope

John Brown's Body *

John Brown's Machete

John C. Koss SP3 Stereophones

John C. Lilly's Isolation Tank Valve

John Cabot's Map

John Carl Wilcke's Rug *

John Crawley's Painting

John Croghan's Limestone Brick

John Dalton's Weather Vane

John Dee's Golden Talisman

John Dee's Obsidian Crystal Ball

John Dee’s Seal of God

John DeLorean's Drawing Table

John Dickson Carr's Driving Gloves

John Dillinger's Pistol *

John D. Grady’s Satchel

John D. Rockefeller's Bible

John D. Rockefeller, Sr. and Jr.'s Top Hats

John Dwight's Hammer

John F. Kennedy's Coconut

John F. Kennedy's Presidental Limousine

John F. Kennedy's Tie Clip *

John Flaxman's Casting Molds

Sir John Franklin's Scarf

John Gay's Shilling

John Gillespie Magee, Jr.'s Pen

John H. Kellogg's Bowl

John H. Kellogg's Corn Flakes

John H. Lawrence's Pacifier

John Hancock's Quill

John Harrison’s Longcase Clock

John Hawkwood’s Lance

John Hendrix's Bible

John Henry Moore's White Banner

John Henry's Sledge Hammer

John Hetherington's Top Hat

John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter's Torture Rack

John Holmes Pump *

John Hopoate's Cleats

John Howard Griffin's Bus Fare

John Hunter's Stitching Wire

John Hunter's Surgical Sutures

John J. Pershing's Boots

John Jacob Astor's Beaver Pelt

John Jervis’ Ship

John Joshua Webb’s Rock Chippings

John Kay's Needle

John Keat's Grecian Urn *

John, King of England's Throne

John L. Sullivan's Boots

John Langdon Down's Stencils

John Lawson's Mannequin Legs

John Lennon's Glasses

John "Liver-Eating" Johnson's Axe

John Logie Baird's Scanning Disk *

John M. Allegro's Fly Amanita

John Macpherson's Ladle

John Malcolm's Chunk of Skin

John Malcolm's Skin Wallet

John McEnroe's Tennis Racket *

John Milner's Yellow '32 Ford Deuce Coupe

John Moore-Brabazon’s Waste Basket

John Morales' McGruff Suit

John Mytton’s Carriage

John Pasche's Rolling Stones Poster Design

John Paul Jones's Sword

John Pemberton's Tasting Spoon

John Philip Sousa's Sousaphone

John Rambo's Composite Bow

John Rykener's Ring

John Shore's Tuning Fork

John Simon's Mouthwash

John Simon Ritchie's Padlock Necklace

John Smith of Jamestown's Sword

John Snow's Dot Map

John Snow’s Pump Handle

John Stapp’s Rocket Sled

John Steinbeck's Luger

John Sutcliffe's Camera

John Sutter's Pickaxe

John Tunstall's Horse Saddle

John Trumbull's "Painting of George Washington"

John von Neumann's Abacus

John Walker's Walking Stick

John Wayne Gacy's Clown Painting *

John Wayne Gacy's Facepaint

John Wesley Hardin's Rosewood Grip Pistol

John Wesley Powell's Canoe

John Wesley Powell’s Canteen

John Wilkes Booth's Boot *

John Wilkes Booth Wanted Poster

John William Polidori's Bookcase

Johnny Ace's Gun

Johnny Appleseed's Tin Pot *

Johnny Campbell's University of Minnesota Sweater

Johnny Depp's Scissor Gloves

Johnny Smith's Steering Wheel

Johnny Weismuller's Loincloth *

Joker's BANG! Revolver

Jon Stewart's Tie

Jonathan Coulton's Guitar

Jonathan R. Davis' Bowie Knife

Jonathan Shay's Copy of Iliad/Odyssey

Jonestown Water Cooler

Jorge Luis Borges' Scrapbook

José Abad Santos' Pebble

José Delgado’s Transmitter

Jose Enrique de la Pena's Chest Piece

Jōsei Toda’s Gohonzon Butsudan

Josef Frings’ Ferraiolo

Josef Mengele's Scalpel

Josef Stefan's Light Bulbs

Joseph of Arimathea's Tomb Rock

Joseph of Cupertino's Medallion *

Joseph Day's Sickle

Joseph Ducreux's Cane

Joseph Dunninger's Pocket Watch

Joseph Dunningers’ Props

Joseph E. Johnston Confederate Flag

Joseph Force Crater's Briefcases

Joseph Fourier's Pocket Knife

Joseph Glidden’s Barbed Wire

Joseph Goebbels' Radio *

Joseph Jacquard's Analytical Loom

Joseph Bolitho Johns’ Axe

Joseph Kittinger's Parachute

Joseph Lister's Padding

Joseph McCarthy's List of Communists

Joseph Merrick's Hood

Joseph-Michel Montgolfier's Wicker Basket

Joseph Moir’s Token

Joseph Pilate's Resistance Bands *

Joseph Polchinski’s Billiard Ball

Joseph Stalin's Gold Star Medal *

Joseph Stalin's Sleep Mask *

Joseph Swan's Electric Light

Joseph Vacher's Accordion

Joseph Vacher's Dog Skull

Joseph Valachi's '58 Chevrolet Impala

Josephus' Papyrus

Joseph Wolpe's Glasses

Josephine Cochrane's Dishwasher

Joshua's Trumpet *

Josiah S. Carberry's Cracked Pot

Joshua Vicks' Original Batch of Vicks Vapor Rub

Josiah Wedgewood's Medallion

Jost Burgi's Armillary Sphere *

Jovan Vladimir's Cross

Juana the Mad of Castiles' Crown

Juan Luis Vives' Quill Set

Juan Moreira’s Facón

Juan Pounce de Leon's Chalice

Juan Ponce de León's Helmet

Juan Seguin's Bandolier

Jubilee Grand Poker Chip *

Judah Loew ben Belazel's Amulet *

Judas Iscariot’s Thirty Silver Coins

Judson Laipply's Shoes

Jules Baillarger's Decanter

Jules Leotard's Trapeze Net

Jules Verne's Original Manuscripts

Julia Agrippa's Chalice

Julia Child's Apron *

Julia Child's Whisk

Julian Assange’s Flash Drive

Julie d’Aubigny's Sabre

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg's Wedding Rings

Julius Asclepiodotus’ Shield Boss

Julius Caesar's Wreath

Julius Wilbrand's Lab Coat Buttons *

Jumanji

Jumper Cables

Junji Koyama’s Vegetables

Jure Sterk's Ballpoint Pen

Jürgen Wattenberg's Leather Provision Bag

Justa Grata Honoria’s Engagement Ring

Justin Bieber's Guitar

Justinian I's Chariot Wheel

Justin O. Schmidt's Wasp Mask

Justus von Liebig's Fertilizer Sack

Justus von Liebig's Mirror

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history, but he is by no means sufficient as a guide in it. The mediaeval period is certainly difficult to arrange. In the first place, it has a double aspect — Feudalism and Catholicism — the organisation of the Fief and Kingdom, and the organisation of the Church. In the next place, these two great types of social organisation are extended over Europe from the Clyde to the Morea of Greece, embracing thousands of baronies, duchies, and kingdoms, each with a common feudal and a common ecclesiastical system, but with distinct local unity and an independent national and provincial history. The facts of mediaeval history are thus infinite and inextricably entangled with each other; the details are often obscure and usually unimportant, whilst the common character is striking and singularly uniform.

The true plan is to go to the fountain-head, and, at what-ever trouble, read the best typical book of the age at first hand — if not in the original, in some adequate translation. I select a few of the most important: — Eginhardt’s Life of Charles the Great; The Saxon Chronicle; Asser’s Life of Alfred, which is at least drawn from contemporary sources; William of Tyre’s and Robert the Monk’s Chronicle of the Crusades; Geoffiey Vinsauf; Joinville’s Life of St. Louis; Suger’s Life of Louis the Fat; St. Bernard’s Life and Sermons (see J. C. Morison’s Life)\ Froissart’s Chronicle; De Commines’ Memoirs; and we may add as a picture of manners, The Paston Letters private tours istanbul.

But with this we must have some general and continuous history. And in the multiplicity of facts, the variety of countries, and the multitude of books, the only possible course for the general reader who is not a professed student of history is to hold on to the books which give us a general survey on a large scale. Limiting my remarks, as I purposely do, to the familiar books in the English language to be found in every library, I keep to the household works that are always at hand.

Sufficiently general for our purpose

It is only these which give us a view sufficiently general for our purpose. The recent books are sectional and special: full of research into particular epochs and separate movements. It is true that the older books have been to no small extent superseded, or at least corrected by later historical researches. They no longer exactly represent the actual state of historical learning. They need not a little to supplement them, and something to correct them. Yet their place has not been by any means adequately filled. At any rate they are real and permanent literature. They fill the imagination and strike root into the memory.

They form the mind; they become indelibly imprinted on our conceptions. They live: whilst erudite and tedious researches too often confuse and disgust the general reader. To the ‘ historian,’, perhaps, it matters as little in what form a book is written, as it matters in what leather it is bound. Not so to the general reader. To teach him at all, one must fill his mind with impressive ideas. And this can only be done by true literary art. For these reasons I make bold to claim a still active attention for the old familiar books which are too often treated as obsolete to-day.

0 notes

Photo

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history, but he is by no means sufficient as a guide in it. The mediaeval period is certainly difficult to arrange. In the first place, it has a double aspect — Feudalism and Catholicism — the organisation of the Fief and Kingdom, and the organisation of the Church. In the next place, these two great types of social organisation are extended over Europe from the Clyde to the Morea of Greece, embracing thousands of baronies, duchies, and kingdoms, each with a common feudal and a common ecclesiastical system, but with distinct local unity and an independent national and provincial history. The facts of mediaeval history are thus infinite and inextricably entangled with each other; the details are often obscure and usually unimportant, whilst the common character is striking and singularly uniform.

The true plan is to go to the fountain-head, and, at what-ever trouble, read the best typical book of the age at first hand — if not in the original, in some adequate translation. I select a few of the most important: — Eginhardt’s Life of Charles the Great; The Saxon Chronicle; Asser’s Life of Alfred, which is at least drawn from contemporary sources; William of Tyre’s and Robert the Monk’s Chronicle of the Crusades; Geoffiey Vinsauf; Joinville’s Life of St. Louis; Suger’s Life of Louis the Fat; St. Bernard’s Life and Sermons (see J. C. Morison’s Life)\ Froissart’s Chronicle; De Commines’ Memoirs; and we may add as a picture of manners, The Paston Letters private tours istanbul.

But with this we must have some general and continuous history. And in the multiplicity of facts, the variety of countries, and the multitude of books, the only possible course for the general reader who is not a professed student of history is to hold on to the books which give us a general survey on a large scale. Limiting my remarks, as I purposely do, to the familiar books in the English language to be found in every library, I keep to the household works that are always at hand.

Sufficiently general for our purpose

It is only these which give us a view sufficiently general for our purpose. The recent books are sectional and special: full of research into particular epochs and separate movements. It is true that the older books have been to no small extent superseded, or at least corrected by later historical researches. They no longer exactly represent the actual state of historical learning. They need not a little to supplement them, and something to correct them. Yet their place has not been by any means adequately filled. At any rate they are real and permanent literature. They fill the imagination and strike root into the memory.

They form the mind; they become indelibly imprinted on our conceptions. They live: whilst erudite and tedious researches too often confuse and disgust the general reader. To the ‘ historian,’, perhaps, it matters as little in what form a book is written, as it matters in what leather it is bound. Not so to the general reader. To teach him at all, one must fill his mind with impressive ideas. And this can only be done by true literary art. For these reasons I make bold to claim a still active attention for the old familiar books which are too often treated as obsolete to-day.

0 notes

Photo

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history, but he is by no means sufficient as a guide in it. The mediaeval period is certainly difficult to arrange. In the first place, it has a double aspect — Feudalism and Catholicism — the organisation of the Fief and Kingdom, and the organisation of the Church. In the next place, these two great types of social organisation are extended over Europe from the Clyde to the Morea of Greece, embracing thousands of baronies, duchies, and kingdoms, each with a common feudal and a common ecclesiastical system, but with distinct local unity and an independent national and provincial history. The facts of mediaeval history are thus infinite and inextricably entangled with each other; the details are often obscure and usually unimportant, whilst the common character is striking and singularly uniform.

The true plan is to go to the fountain-head, and, at what-ever trouble, read the best typical book of the age at first hand — if not in the original, in some adequate translation. I select a few of the most important: — Eginhardt’s Life of Charles the Great; The Saxon Chronicle; Asser’s Life of Alfred, which is at least drawn from contemporary sources; William of Tyre’s and Robert the Monk’s Chronicle of the Crusades; Geoffiey Vinsauf; Joinville’s Life of St. Louis; Suger’s Life of Louis the Fat; St. Bernard’s Life and Sermons (see J. C. Morison’s Life)\ Froissart’s Chronicle; De Commines’ Memoirs; and we may add as a picture of manners, The Paston Letters private tours istanbul.

But with this we must have some general and continuous history. And in the multiplicity of facts, the variety of countries, and the multitude of books, the only possible course for the general reader who is not a professed student of history is to hold on to the books which give us a general survey on a large scale. Limiting my remarks, as I purposely do, to the familiar books in the English language to be found in every library, I keep to the household works that are always at hand.

Sufficiently general for our purpose

It is only these which give us a view sufficiently general for our purpose. The recent books are sectional and special: full of research into particular epochs and separate movements. It is true that the older books have been to no small extent superseded, or at least corrected by later historical researches. They no longer exactly represent the actual state of historical learning. They need not a little to supplement them, and something to correct them. Yet their place has not been by any means adequately filled. At any rate they are real and permanent literature. They fill the imagination and strike root into the memory.

They form the mind; they become indelibly imprinted on our conceptions. They live: whilst erudite and tedious researches too often confuse and disgust the general reader. To the ‘ historian,’, perhaps, it matters as little in what form a book is written, as it matters in what leather it is bound. Not so to the general reader. To teach him at all, one must fill his mind with impressive ideas. And this can only be done by true literary art. For these reasons I make bold to claim a still active attention for the old familiar books which are too often treated as obsolete to-day.

0 notes

Photo

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history, but he is by no means sufficient as a guide in it. The mediaeval period is certainly difficult to arrange. In the first place, it has a double aspect — Feudalism and Catholicism — the organisation of the Fief and Kingdom, and the organisation of the Church. In the next place, these two great types of social organisation are extended over Europe from the Clyde to the Morea of Greece, embracing thousands of baronies, duchies, and kingdoms, each with a common feudal and a common ecclesiastical system, but with distinct local unity and an independent national and provincial history. The facts of mediaeval history are thus infinite and inextricably entangled with each other; the details are often obscure and usually unimportant, whilst the common character is striking and singularly uniform.

The true plan is to go to the fountain-head, and, at what-ever trouble, read the best typical book of the age at first hand — if not in the original, in some adequate translation. I select a few of the most important: — Eginhardt’s Life of Charles the Great; The Saxon Chronicle; Asser’s Life of Alfred, which is at least drawn from contemporary sources; William of Tyre’s and Robert the Monk’s Chronicle of the Crusades; Geoffiey Vinsauf; Joinville’s Life of St. Louis; Suger’s Life of Louis the Fat; St. Bernard’s Life and Sermons (see J. C. Morison’s Life)\ Froissart’s Chronicle; De Commines’ Memoirs; and we may add as a picture of manners, The Paston Letters private tours istanbul.

But with this we must have some general and continuous history. And in the multiplicity of facts, the variety of countries, and the multitude of books, the only possible course for the general reader who is not a professed student of history is to hold on to the books which give us a general survey on a large scale. Limiting my remarks, as I purposely do, to the familiar books in the English language to be found in every library, I keep to the household works that are always at hand.

Sufficiently general for our purpose

It is only these which give us a view sufficiently general for our purpose. The recent books are sectional and special: full of research into particular epochs and separate movements. It is true that the older books have been to no small extent superseded, or at least corrected by later historical researches. They no longer exactly represent the actual state of historical learning. They need not a little to supplement them, and something to correct them. Yet their place has not been by any means adequately filled. At any rate they are real and permanent literature. They fill the imagination and strike root into the memory.

They form the mind; they become indelibly imprinted on our conceptions. They live: whilst erudite and tedious researches too often confuse and disgust the general reader. To the ‘ historian,’, perhaps, it matters as little in what form a book is written, as it matters in what leather it is bound. Not so to the general reader. To teach him at all, one must fill his mind with impressive ideas. And this can only be done by true literary art. For these reasons I make bold to claim a still active attention for the old familiar books which are too often treated as obsolete to-day.

0 notes

Photo

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history, but he is by no means sufficient as a guide in it. The mediaeval period is certainly difficult to arrange. In the first place, it has a double aspect — Feudalism and Catholicism — the organisation of the Fief and Kingdom, and the organisation of the Church. In the next place, these two great types of social organisation are extended over Europe from the Clyde to the Morea of Greece, embracing thousands of baronies, duchies, and kingdoms, each with a common feudal and a common ecclesiastical system, but with distinct local unity and an independent national and provincial history. The facts of mediaeval history are thus infinite and inextricably entangled with each other; the details are often obscure and usually unimportant, whilst the common character is striking and singularly uniform.

The true plan is to go to the fountain-head, and, at what-ever trouble, read the best typical book of the age at first hand — if not in the original, in some adequate translation. I select a few of the most important: — Eginhardt’s Life of Charles the Great; The Saxon Chronicle; Asser’s Life of Alfred, which is at least drawn from contemporary sources; William of Tyre’s and Robert the Monk’s Chronicle of the Crusades; Geoffiey Vinsauf; Joinville’s Life of St. Louis; Suger’s Life of Louis the Fat; St. Bernard’s Life and Sermons (see J. C. Morison’s Life)\ Froissart’s Chronicle; De Commines’ Memoirs; and we may add as a picture of manners, The Paston Letters private tours istanbul.

But with this we must have some general and continuous history. And in the multiplicity of facts, the variety of countries, and the multitude of books, the only possible course for the general reader who is not a professed student of history is to hold on to the books which give us a general survey on a large scale. Limiting my remarks, as I purposely do, to the familiar books in the English language to be found in every library, I keep to the household works that are always at hand.

Sufficiently general for our purpose

It is only these which give us a view sufficiently general for our purpose. The recent books are sectional and special: full of research into particular epochs and separate movements. It is true that the older books have been to no small extent superseded, or at least corrected by later historical researches. They no longer exactly represent the actual state of historical learning. They need not a little to supplement them, and something to correct them. Yet their place has not been by any means adequately filled. At any rate they are real and permanent literature. They fill the imagination and strike root into the memory.

They form the mind; they become indelibly imprinted on our conceptions. They live: whilst erudite and tedious researches too often confuse and disgust the general reader. To the ‘ historian,’, perhaps, it matters as little in what form a book is written, as it matters in what leather it is bound. Not so to the general reader. To teach him at all, one must fill his mind with impressive ideas. And this can only be done by true literary art. For these reasons I make bold to claim a still active attention for the old familiar books which are too often treated as obsolete to-day.

0 notes

Text

Jeanne II of Navarre and her attachment to her birthright.

(Jeanne II de Navarre, Le Livre d'Heures de Jeanne de Navarre, Jean Le Noir, 1336-1340)

****

Although Philip de Valois was able to win support for his rights to the French throne in 1328, Juana certainly never forgot her birthright as the daughter of the King of France and referred to herself as such in her address clause. Another reference to her Capetian lineage can be found in the unusual image cycle of Saint Louis in Juana's Book of Hours, which stresses the king's coronation and kingship rather than the customary images of his sainthood. Tania Mertzman argues in her study of the Book of Hours that the unusual image cycle "suggests that Juana is a worthy and direct descendant of Louis IX who should not be denied her place in the Capetian lineage and succession." Marguerite Keane believes that the book may have been commissioned to mark the birth of Juana's first son, Louis, in 1330 and that the choice of images signals her ambition for her child to succeed to the French throne. However, Martinez de Aguirre suggests a much later date for this commission, between 1336 and 1340. While this would not negate the previous suggestion regarding the Capetian succession, it would conflict with Keane's link to the birth of Juana's first son. In addition, Martinez de Aguirre notes the presence of her mother's Burgundian coat of arms, which is intriguing considering the adultery scandal that led to her disgrace and death. However, it appears that Juana did not disassociate herself from her mother and her Burgundian lineage; her maternal grandmother Agnès had been the greatest supporter of her hereditary rights during the succession crisis of 1316, and documentary evidence shows that Juana spent 7 livres and 12 sous for a "tapis vert" for the tomb of her mother emblazoned with the arms of France, Navarre, Champagne and Burgundy.

Certainly the behavior of her son Carlos II during the Hundred Years war could be interpreted as the actions of a man who believed that his own claim to the French throne was superior to that of the Valois and and his cousin Edward III of England. In Froissart's chronicle, Carlos II addressed the Parisians:

"He said that no one should feel any fear of him, since he was ready to live and die defending the kingdom of France- as indeed he was bound to, for he was descended in the direct line on both his father's and his mother's side. And he let it be understood clearly enough that, if he ever wished to lay claim to the French crown, he could show that he had a better right to it than the King of England."

Elena Woodacre- The Queens Regnant of Navarre- Succession, Politics and Partnership, 1274-1512

#xiv#elena woodacre#the queens regnant of navarre#jeanne de france#jeanne ii de navarre#queens of navarre#agnès de france#grandmother and granddaughter#marguerite de bourgogne#charles ii de navarre#he did have a better claim than edward iii

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history

Gibbon takes us into mediaeval history, but he is by no means sufficient as a guide in it. The mediaeval period is certainly difficult to arrange. In the first place, it has a double aspect — Feudalism and Catholicism — the organisation of the Fief and Kingdom, and the organisation of the Church. In the next place, these two great types of social organisation are extended over Europe from the Clyde to the Morea of Greece, embracing thousands of baronies, duchies, and kingdoms, each with a common feudal and a common ecclesiastical system, but with distinct local unity and an independent national and provincial history. The facts of mediaeval history are thus infinite and inextricably entangled with each other; the details are often obscure and usually unimportant, whilst the common character is striking and singularly uniform.

The true plan is to go to the fountain-head, and, at what-ever trouble, read the best typical book of the age at first hand — if not in the original, in some adequate translation. I select a few of the most important: — Eginhardt’s Life of Charles the Great; The Saxon Chronicle; Asser’s Life of Alfred, which is at least drawn from contemporary sources; William of Tyre’s and Robert the Monk’s Chronicle of the Crusades; Geoffiey Vinsauf; Joinville’s Life of St. Louis; Suger’s Life of Louis the Fat; St. Bernard’s Life and Sermons (see J. C. Morison’s Life)\ Froissart’s Chronicle; De Commines’ Memoirs; and we may add as a picture of manners, The Paston Letters private tours istanbul.

But with this we must have some general and continuous history. And in the multiplicity of facts, the variety of countries, and the multitude of books, the only possible course for the general reader who is not a professed student of history is to hold on to the books which give us a general survey on a large scale. Limiting my remarks, as I purposely do, to the familiar books in the English language to be found in every library, I keep to the household works that are always at hand.

Sufficiently general for our purpose

It is only these which give us a view sufficiently general for our purpose. The recent books are sectional and special: full of research into particular epochs and separate movements. It is true that the older books have been to no small extent superseded, or at least corrected by later historical researches. They no longer exactly represent the actual state of historical learning. They need not a little to supplement them, and something to correct them. Yet their place has not been by any means adequately filled. At any rate they are real and permanent literature. They fill the imagination and strike root into the memory.

They form the mind; they become indelibly imprinted on our conceptions. They live: whilst erudite and tedious researches too often confuse and disgust the general reader. To the ‘ historian,’, perhaps, it matters as little in what form a book is written, as it matters in what leather it is bound. Not so to the general reader. To teach him at all, one must fill his mind with impressive ideas. And this can only be done by true literary art. For these reasons I make bold to claim a still active attention for the old familiar books which are too often treated as obsolete to-day.

0 notes