#luis alvarez

Photo

Quarantine - Luis Alvarez

Argentinian , b. ? -

Oil on canvas , 100 x 120 cm.

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

pick a best friend

You know that meme where they show you different outfits and you think of names of the people who would wear them and talk about their personalities?

I have no idea how true this is but pick a Rad Lab "boy"

(P.S. I love how I'm catering to one person like I have five followers but @un-ionizetheradlab is the only one who seems to care /lh)

#manhattan project#rad lab#uc berkeley#ernest lawrence#j robert oppenheimer#luis alvarez#edwin mcmillan#glenn seaborg#emilio segre#chien shiung wu#robert wilson#pick a best friend

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

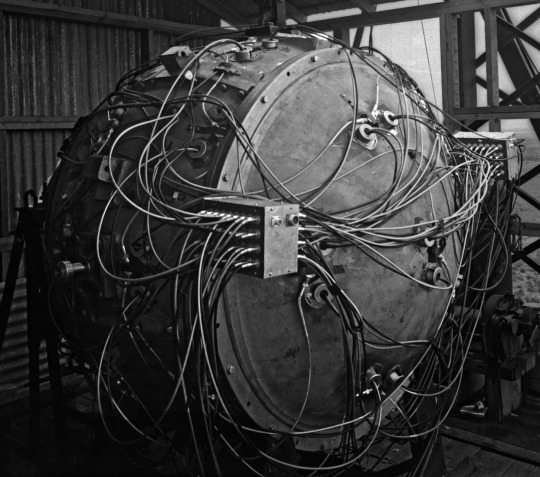

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

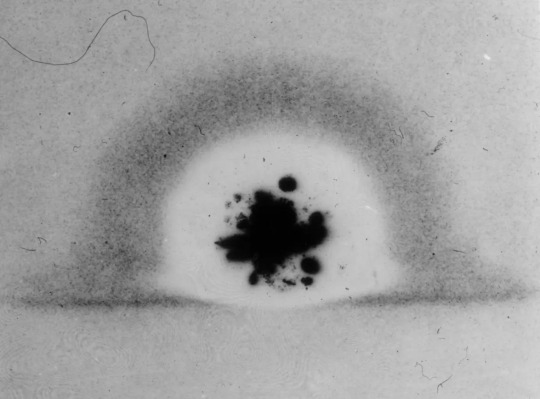

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

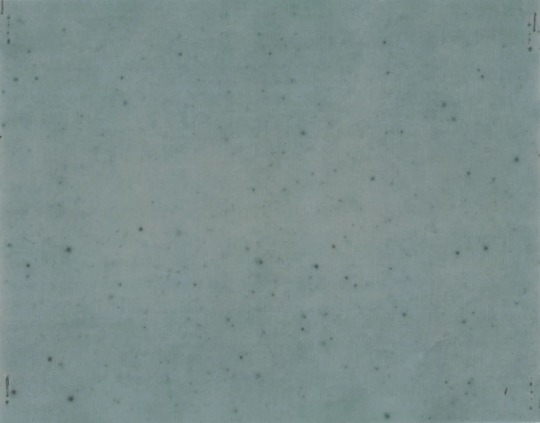

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mujeres

Bukowski les escribió un libro,

Da Vinci les dibujo una sonrisa eterna,

Neruda las convirtió en un poema,

Sabina las volvió canción,

El Marqués de Sade las transformó en tentación.

La guerra entre Esparta y Troya fue por Helena, Napoleón en medio de sus batallas por Europa le escribía cartas de amor a Josefina, Apolo dios de la poesía se obsesionó con Dafne, Poe se volvió loco por Leonora, Dante cruzó el infierno por Beatriz.

Algunas religiones las acusan del

pecado original cuando en realidad ustedes son unas diosas, El Taj Mahal maravilla del mundo se construyó en honor a una princesa.

Poderosos huracanes y delicadas flores llevan sus nombres.

José Alfredo y Silvio se perdieron en el alcohol y encontraron inspiración para escribir las canciones más hermosas para ustedes.

Unas son amas de casa, doctoras, licenciadas, maestras, estilistas, comerciantes, estudiantes, etc.

Y pues, los hombres comúnes y normales simplemente las convertimos en el amor de nuestra vida.

Libro: Apodyopsis| Luis Alvarez

#Apodyopsis#Luis Alvarez#frases#escritos#pensamientos#poesia#fragmentos#literatura#escritores#libros#poemas#literatura universal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Serber and Luis Alvarez.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecilia Gómez by © Luis Alvarez

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

'“Oppenheimer” has been justly praised for its attempt at historical fidelity in telling the life story of the brilliant, agonized physicist, but it’s not a documentary.

The movie gets most things right about Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project, the government effort to build the atomic bomb, as one would expect given that filmmaker Christopher Nolan based it on “American Prometheus,” the superb 2005 biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.

But artistic imperatives and Nolan’s understandable choice to tell his story from Oppenheimer’s point of view led him to perpetuate a few myths about the making of the atomic bomb and to gloss over aspects of the story that may be interesting for lay viewers.

Based on what I gleaned about Oppenheimer and the project from researching my 2015 biography of Berkeley physicist Ernest O. Lawrence (played in the movie by Josh Hartnett), “Big Science,” I’ll try to correct the Hollywood record and fill in the gaps.

Let’s jump in.

For the most part, Nolan sticks to the facts. “Oppenheimer” is notable among biopics for portraying real people doing the things they did at the time. Even peripheral characters who flit briefly across the screen are given their real names or identifiable characteristics.

As far as I can tell, the only imaginary or composite character in the film is the unnamed Senate aide played by Alden Ehrenreich, whose dramatic function is to be a sounding board for the grousing of Lewis L. Strauss (brilliantly played by Robert Downey Jr.), Oppenheimer’s political nemesis.

That bongo-playing physicist glimpsed at the Trinity plutonium bomb test in the New Mexico desert? Unnamed in the film, he’s Richard Feynman, later to be revered as Caltech’s resident genius but, at 24, attached to the Los Alamos bomb lab at the very beginning of his scientific career. (He did bring his bongos to the desert.)

Lawrence’s associate Luis Alvarez, later a Nobel laureate, is accurately portrayed as bursting into an Oppenheimer seminar in 1939 with the first news of the discovery of nuclear fission by German physicists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann. The film also accurately shows Oppenheimer instantly responding, “That’s impossible,” promptly withdrawing his snap judgment and, within a week, outlining how the discovery might be used to make a bomb.

But the film doesn’t cover Alvarez’s resentful and damaging testimony in the Oppenheimer security hearing, during which he claimed to have heard Vannevar Bush, the top science advisor to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, reveal that Truman had not trusted Oppenheimer. Bush — who is played by Matthew Modine — vociferously contradicted the story.

The most glaring historical gaffe is the film’s perpetuation of the myth that Oppenheimer was the boss of the Manhattan Project; it shows him assuring Gen. Leslie R. Groves that he can run the project. (Matt Damon would have had to put on at least 50 or 60 pounds to more accurately impersonate Groves, who tipped the scales at nearly 300 pounds.)

Oppenheimer was merely the boss of Los Alamos, one of the project’s numerous separate labs and technical installations. Its job was to actually build the bomb, drawing on the research of labs at Columbia, the University of Chicago and Berkeley. Though Groves was the overall boss, the project’s scientific management was divided, rather tetchily, between Lawrence and Arthur Holly Compton of the University of Chicago.

Lawrence was the scientist whose advice Groves trusted the most. He originally wanted Lawrence to run the lab that was eventually built at Los Alamos, but decided Lawrence was too important to be limited to the bomb-designing task.

Oppenheimer was Groves’ second choice, but he turned to Lawrence for assurance that Oppenheimer could effectively run the bomb lab.

Lawrence, who at that time was a close friend of Oppenheimer, his valued colleague at UC Berkeley — he named his first son Robert after Oppenheimer — assuaged Groves’ concerns about Oppenheimer’s leftist politics and lack of a Nobel Prize. Lawrence sealed the deal for his friend by promising Groves that if Oppenheimer failed in his task, he would take it over himself.

A few words about Ernest Lawrence. Before and during the war, the South Dakota native was the most famous and influential scientist in America — arguably the first home-grown scientific celebrity in American history.

The inventor of the cyclotron, the most important atom-smasher of its era and the invention that transformed particle physics in the 1930s, Lawrence was featured on the cover of Time magazine on Nov. 1, 1937, over the caption “He creates and destroys,” and won the Nobel Prize in 1939.

Lawrence’s skill at explaining complex scientific principles in lay terms kept him in the public eye via radio talks and newspaper articles and helped him attract millions of dollars in foundation and government funding for his Radiation Laboratory — the “Rad Lab” — at UC Berkeley. It was due to his influence that UC was awarded the contract to run Los Alamos after the war, which it still holds, albeit with somewhat diminished authority. Lawrence also invented a color TV system that was eventually incorporated into Sony’s Trinitron technology.

Oppenheimer, by contrast, was almost entirely unknown to the general public until after the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, when he was thrust into fame as “the father of the atomic bomb.”

Among the physics fraternity, however, Oppenheimer was virtually a cult figure, which is painted only murkily in the film. His graduate students at Berkeley and Caltech, where he held joint appointments, chain-smoked his brand of cigarettes (Chesterfields), imitated his loping gait, and replicated the almost unintelligible mumbling of his lecturing style.

Austrian physicist Paul Ehrenfest, a friend of Oppenheimer’s who sat through one of his Caltech lectures straining to make out his words, finally blurted out, “Oppie, is it a secret?”

Another myth perpetuated by the film is that the physicists were afraid that the bomb blast might ignite the atmosphere, destroying the world. “Oppenheimer” depicts this possibility being debated almost as late as the Trinity test. In fact, it had been raised very briefly in 1942 and promptly put to rest by Manhattan Project physicist Hans Bethe, who later called it “absolute nonsense.”

One more point concerns Oppenheimer’s recollection that upon witnessing the fireball produced by the Trinity test, he immediately thought of a line from the Sanskrit Bhagavad-Gita: “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

The film takes him at his word, but the truth is that he never mentioned this in public until 1965; one friend considered the claim to be one of Oppenheimer’s “priestly exaggerations.” By the way, the line from the Hindu scripture has been translated in other ways, notably as “I am become time, destroyer of worlds,” perhaps a subtler and more sinister thought than Oppie’s version.

Some aspects of the 1954 security hearing as depicted in the film warrant further examination. The film accurately shows that Groves, asked if he would give Oppenheimer a security clearance at the time of the hearing, answered carefully that he would not, under the stringent security rules imposed by the Atomic Energy Commission. But his subsequent sotto voce remark, to the effect that he probably wouldn’t give any of the Manhattan Project scientists clearance under those rules, doesn’t appear anywhere in the 1,011-page hearing transcript.

Then there’s Lawrence’s decision not to testify against his old friend. By 1954, Lawrence and Oppenheimer had had a bitter falling-out. The film attributes this mostly to Lawrence’s fury upon learning that Oppenheimer had carried on an affair with the wife of Caltech physicist Richard Tolman, a close friend of Lawrence. Tolman committed suicide shortly after learning of the betrayal, which Lawrence ascribed to his broken heart.

But another reason for their split was Oppie’s campaigning against the hydrogen bomb program, which Lawrence favored and which was a major source of government patronage for his lab — Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, an offshoot of the Rad Lab, had been founded largely to pursue research on the so-called Super.

Although Lawrence had promised Strauss, who as chairman of the AEC oversaw all civilian government nuclear research and stage-managed the security hearing, that he would testify, he was racked with second thoughts as his appearance date approached.

Lawrence knew that the physics community overwhelmingly supported Oppenheimer, and that Berkeley had become the center of anti-Oppenheimer sentiment, in part because of the conflict over the H-bomb program. This was not a good look for the Rad Lab.

Contrary to the film’s depiction, Lawrence never actually showed up outside the hearing room. Instead, he phoned Strauss the Monday before his scheduled appearance from the government’s Oak Ridge lab, which he had founded and designed for the production of enriched uranium for the bomb ultimately dropped on Hiroshima (the Trinity test was of a plutonium bomb like that dropped on Nagasaki, which was a much more complicated engineering challenge).

As the film shows, Lawrence pleaded a medical excuse — an outbreak of ulcerative colitis, the condition that would ultimately kill him in 1958. After Strauss responded with a vicious tongue-lashing over the phone, culminating in an accusation of cowardice, Lawrence summoned his fellow Oak Ridge guests, all government lab directors, to prove he was not feigning illness by showing them his toilet, brimming with bright red blood.

Christopher Nolan’s film implicitly asks viewers to come to their own conclusions about the moral dimension of the decision to drop the bomb on Japan. A committee of four physicists — Oppenheimer, Lawrence, Compton and Fermi — was tasked with the options, which included staging a demonstration at an uninhabited Pacific island to show Japanese officials what they faced if they didn’t surrender.

Lawrence, who had worked with Japanese scientists to build the first cyclotrons outside the U.S., was the last member of the committee to agree that using the bomb was the only choice, for the possibility of a dud demonstration was too great to risk. As the committee chair, Oppenheimer signed the one-page memo, dated June 16, 1945, that came to the dismaying conclusion that “we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.”

What the physicists didn’t know was that the decision already had been taken out of their hands. That Boeing B-29 bombers that would carry the bombs had already been assembled on Tinian Island, 1,500 miles south of Japan, and the military decision to use the bombs was preordained.

How should we think about the development of nuclear weapons and Oppenheimer’s role? My view is that the Manhattan Project was understandable and defensible given the wartime context. Allied physicists, especially refugees from the Nazi regime, knew that although Hitler had driven away Jewish scientists, the physicists left behind in Germany were among the best in the world, perfectly capable of developing the atomic bomb. They were in a panic that Hitler might get the weapon before the Allies.

They had no way of knowing that, as the Allies discovered after Germany’s surrender, there had been no German bomb project because the Germans miscalculated the physics involved and didn’t have access to the resources and equipment, including the cyclotron, in the U.S. and Britain.

The decision to pursue the hydrogen bomb is another story. Fermi and other leading physicists understood that its incredible power meant it could only be a weapon of genocide. Some worked on it anyway. Oppenheimer’s notion that nuclear research should be placed under international control to forestall the perils of nuclear proliferation was idealistic, but in terms of geopolitical reality hopelessly naive. There was no way that the U.S. and Britain would cede control of the technology to any international body after 1945.

The tragic message of Oppenheimer and “Oppenheimer” is that humankind has lived under a nuclear sword of Damocles ever since.'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#American Prometheus#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Ernest O. Lawrence#Josh Hartnett#Lewis Strauss#Alden Ehrenreich#Robert Downey Jr.#Richard Feynman#Luis Alvarez#Otto Hahn#Fritz Strassmann#Vannevar Bush#Franklin D. Roosevelt#President Truman#Matthew Modine#Leslie Groves#Matt Damon#Los Alamos#The Manhattan Project#Arthur Holly Compton#Nobel Prize#Hans Bethe#Trinity test#Bhagavad-Gita#Richard Tolman#Enrico Fermi

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

From left to right: Luis Alvarez, Herbert York, Donald Cooksey, Edwin McMillan, Edward Teller, and Ernest Lawrence.

#dream team#edwin mcmillan#edward teller#teller ede#ernest lawrence#luis alvarez#herbert york#LLNL#lawrence livermore national lab

0 notes

Text

Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man #138 (1988)

Captain America (Walker) has a change of mind.

#john walker#peter parker the spectacular spider man#marvel comics#comic panels#peter parker#luis alvarez

1 note

·

View note

Text

Such was the question Luis Alvarez asked himself.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quote#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#questions#luis alvarez

0 notes

Photo

Heladera - Luis Alvarez

Argentinian , b. ? -

Oil on canvas , 100 x 100 cm.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rad Lab "boys" on the magnet yoke for the 60-inch cyclotron (1938)

Oh yeah btw the 60-inch cyclotron was called the "Crocker Cracker".

Ernest Lawrence is fourth from the left, front row

J. Robert Oppenheimer is the guy smoking in the back

Other people included are Luis Alvarez, Edwin McMillan, John Lawrence, Robert Wilson, and Raymond Birge (fifth from right)

I love these guys lol

#rad lab#berkeley#uc berkeley#ernest lawrence#j robert oppenheimer#oppenheimer#luis alvarez#edwin mcmillan#john lawrence#robert wilson#raymond birge#cyclotron

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

An entry in his diary reads:

October 5 1949. Latimer and I independently thought that the Russians could be working hard on the Super and might get there ahead of us. The only thing to do seems to get there first – but hope that it will turn out to be impossible.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quotes#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#luis alvarez#diary entry#october 5#40s#1940s#wendell latimer#russian#atomic bomb#fission bomb#nuclear fission

0 notes

Photo

LA TARANTULA has been added to the MCOC Wishlist

This savage Delvadian/Latin American mercenary/villain/hero mantle is a classic recurring Spider-Man rogue and deserves to be in a Marvel video game like #MCOC @MarvelChampions .

#Tarantula#La Tarantula#César Mendivil#Anton Miguel Rodriquez#Rodriquez family#Latinx#Latino#Latina#Spider-Man rogue#Luis Alvarez#Jacinda Rodriquez#Maria Vasquez#soldier & spy#South America#additions#recent rank#spreadsheet cleanup#mercenary#Wishlist Cleanup#father-daughter#Delvadia#Zorro pastiche

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cecilia Gómez by © Luis Alvarez

4 notes

·

View notes