#luke crain

Text

The Haunting of Hill House

1.09 – Screaming Meemies

#the haunting of hill house#olivia crain#nell crain#luke crain#thohhedit#hillhouseedit#thehauntingsource#mikeflanaganuniverse#horroredit#usertj#tuserheidi#userriel#usercats#horrortvfilmsource#userbbelcher#chewieblog#dailynetflix#*gif#*airi#hh 1x09

577 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE

1.01 "Steven Sees a Ghost"

#the haunting of hill house#thohhedit#thehauntingsource#adaptationsdaily#tvarchive#smallscreensource#userspot#tvfilmsource#tvfilmcentral#filmtvdaily#cinemapix#tvedit#dailycolorfulgifs#usermorgan#userrobin#steven crain#luke crain#mine*#ep: steven sees a ghost#this scene is so precious

512 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like Hill House and House of Usher are teaching the same moral using opposite techniques.

#haunting of hill house#hill house#fall of the house of usher#mike flanagan#house of usher#flaniverse#the haunting of hill house#the fall of the house of usher#Netflix#hugh crain#nell crain#theo crain#shirley crain#luke crain#olivia crain#roderick usher#tamerlane usher#lenore usher#annabel lee usher#frederick usher#camille usher#madeline usher#house of usher spoilers#usher

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's been almost five years since The Haunting of Hill House came out on Netflix. And it has irrevocably changed my life.

The depiction of grief. Addiction. Depression. Loss. Identity. Family relationships. Family dynamics. Healing your inner child. Having to deal with your inner child. The fact that in some ways you never really grow up, you're that exact same person inside that is dealing with all these increasingly complex and difficult things, trying hard to not let the child in you react because you know it shouldn't.

Thinking about Theo taking her gloves off. Nell going to therapy, putting in work, and still having her demons chase her around all the way to the end. Shirley's entire life and career being based around wanting to help people in their darkest moments the way someone helped her (though isn't that what they all do, too? Especially Theo). Luke as the youngest, being left behind or not believed and eventually having to find ways to self-soothe, which as an adult are not as health-friendly as other options out there. But it's what he had to do to cope. And Steve... everyone knows a Steve.

I know people have commented before about the five Crain siblings and the five stages of grief. But they also each experience those themselves, and in some ways the five of them simply display how much grief and living can do to a person. Juxtaposing the entire modern part of the series with them as children reminded me how much the things I do now can also be drawn back to little Me. The decisions I make, what scares me, who I reach out to. What haunts me? I may not have a big scary terrifying Death House in my past, but I mean... we've all got our version of a big scary terrifying Death House.

The tragedy of Hill House, the complicated love that's shown, the connections and relationships we have with our families, the world, ourselves. I cannot, will not, should not, would not forget it.

#hill house#haunting of hill house#thohh#the haunting of hill house#steve crain#shirley crain#theo crain#nell crain#luke crain#grief#thoughts#random#family trauma#tv#idk#anyone know what I mean?

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s start with some hill house fanarts

#the haunting of hill house#theo crain#art#Crain siblings#nell Crain#Steven Crain#Shirley crain#Luke crain

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

In episode 8 of The Haunting of Hill House when Luke goes to burn down the house he gets 5 canisters of gas, which is out of character for him. He's all about the 7. Seven counts for seven Crains. But the house already took 2. So he's got the five cans for the five living Crains.

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

My favorite hobby is using Instagram stories to create mike Flanagan related memes

Anyway-isn’t this literally the plot of episode four?

#mike flanagan#the haunting of hill house#hill house#luke crain#steve crain#nell crain#shirley crain#the hat man

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

The haunting of hill house being about how the kitchen is the heart of the house, because that’s where we spend the most time together, and the red room is the stomach, and it’s where we spend the least time together, and how the place where you eat is where you love and when you haven’t been in home in a long while, you confuse being eaten for being loved

I mean how could you tell the difference? Your mother fed you and now your mother feeds on you and isn’t that what love is? If I can’t have the heart, I’ll have the stomach. That’s the way to the heart anyways. That’s where everything goes.

Food is everything and every child would be swallowed up by a wolf if it meant being everything to something.

Every child just wants to come home. Be welcomed home. Be called home. They’ll offer up space inside themselves to do it. Lonely and starving and wanting to prove they can share.

Nell hopes for coffee.

Luke buys burgers.

Theo eats with Shirley.

Shirley insists on family dinner.

Steven is an eater. He eats stories. (Stories live longer than people. Stories keep people alive).

Hill house makes eating sound cruel, to make the kids feel guilty for being hungry, to make them hungrier, and make them choose being eaten over eating.

But the kitchen is the heart of the house.

It’s where they eat. (where they give and take and share and keep and indulge and provide love).

Steven is shared stories, and in turn shares them.

Shirley makes family dinners.

Theo prefers to eat with her sister.

Luke fills someone’s stomach.

Nell is asked out for coffee.

#oh to be wake all night and rant about the haunting of hill house#the difference between love and possession#feeding someone and eating them#the haunting of hill house#netflix#nell crain#theo crain#luke crain#steven crain#shirley crain

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

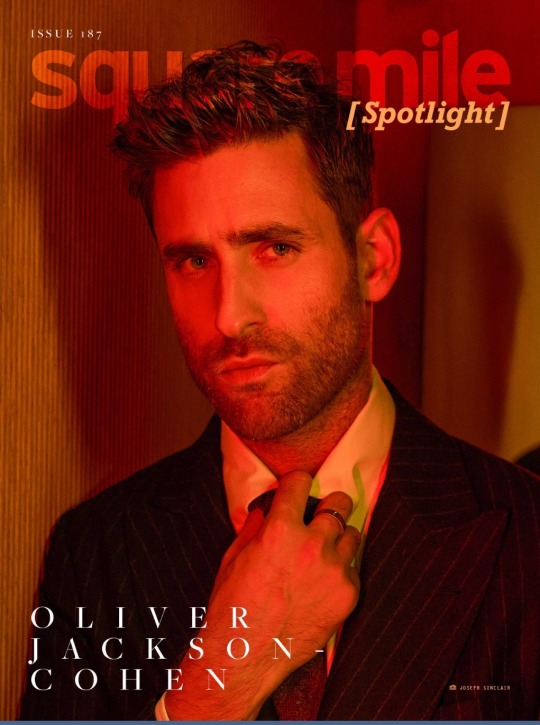

Few actors have endured as fraught a journey as Oliver Jackson-Cohen. Few actors are more in demand than the star of The Haunting of Hill House and Jackdaw

by Maeve Ryan

OLIVER JACKSON-COHEN HAS been doing this a while. He decided to act at the age of six. Joined a theatre troupe and began to climb. He continued until university but didn’t get into any drama schools. Throughout our conversation, he tells me there were no signs pointing him in this direction, no surefire chance at success. But he’s found it, and then some.

He rose to prominence with his highly acclaimed portrayal of Luke Crain in Mike Flanagan’s The Haunting of Hill House.

A character that battled a heroin addiction to cope with past traumas, though addiction was the least interesting thing about him. The show featured stars of the past, and launched new ones into the present, Oliver Jackson-Cohen being one of them. The role of Luke changed the course of his life – for more reasons than one.

It was the first time in his life he no longer had to hide, he tells me. “I could be as fragile as I felt.” He took his newfound Netflix fame and began to carve a path that finally aligned with who he was, not who the world wanted him to be.

Now, he takes centre stage in Jamie Dobb’s new film Jackdaw. When he read the script, he thought he was the last man for the job. When Dobb explained the hyper masculine lead needed someone to bring softness behind it, he signed on.

Jackson-Cohen’s career, and presence, proves that the strength of a man lies in his ability to go beyond society’s standards. He breaks the stereotypes like bread over a long conversation in Soho. We discuss his entrance into the industry, facing traumas, and finding a safe place to land.

sm: What was the first movie you ever saw that made you want to act?

o-jc: Home Alone. I remember seeing that film and saying, oh whoa, so a kid can do this? I remember telling my dad, ‘I think I want to do that.’ I was six or seven.

But it gets dark. So, my mum and dad’s house had a bay window that was on the street. And when I came home from school for a week, I just sat in the window thinking, any minute now, someone from Home Alone is going to walk past, and go, there’s a kid! Let’s get him! I was willingly wanting to get kidnapped. Which is so fucked. My dad came home and was like, ‘What are you doing?’ And then he was like, ‘Yeah, that’s not how that works.’

We found a theatre program – I started going there when I was eight. I was never the golden kid. In the drama clubs, I was always like the snake in the background. Or just the scenery. We used to put on terrible plays. I was such an insular kid. I found a safe place to feel where it’s real, but it’s not. So you can experience it all. I did that for three years, and then I was kicked out.

sm: What! Why?

oj-c: I had an attitude or something like that. I got suspended so many times. I genuinely was not looking for trouble. I was always the one to get caught. Like, I was the kid who someone handed the knife to, and I’d be standing above the dead body, and then the next thing I knew it was 20 years in prison. It was always stuff like that. But it was time to move on anyway.

I found this drama school at Riverside Studios. It was a small group, maybe eight or nine people. It was so interesting, because I’m going to do a gross name drop, but in the group was Carey Mulligan and Imogen Poots. It was incredible.

sm: Those were the kids that were just there? Did you have to audition?

oj-c: No, but I did a trial. It was a lot of devised stuff, like improv. A guy named Andrew Bradford ran it. He really supported kids. It was all day Saturday. We were all teenagers. It felt like another life. It grew and grew and by the time I left I was 17 or 18. It wasn’t one of those places that you were beaten down. No fake bullshit. It was a safe place to try stuff. We’d put on plays and we all got agents from that as kids.

sm: Is that the moment you look back on and think of as the beginning?

oj-c: I think so. But it was such a long period of time. Career wise, it was quite stagnant. I did one job when I was 15 that was some late night soap. Then I didn’t do anything until I was 18. I wasn’t like this is real until later. It started to snowball when I finished school. I went to get a French lit degree, hated it, dropped out, and applied to drama school. I didn’t get in anywhere.

In the meantime, there was a job at the BBC for a silly period drama. I did that, took the money, and went to do a foundation in New York at Strasberg.

sm: Tell me about the audition for drama school. You didn’t get in anywhere?

oj-c: Yes. I’m telling you there were no signs that pointed to me saying, yeah, you’re quite good at this. It felt like everyone was saying, ‘don’t do it.’ Which is a really interesting place to start from. If no one around me believes in me, how do I? And I just keep going? It was a mix of delusion and stupidity.

sm: Did you think about doing something else?

oj-c: When I was still in high school, I worked as a runner on productions, mainly at the BBC. I was revolving through that so when I finished school, that was kinda my job.. I got to see the inner workings of how sets worked, rehearsal periods. I got to see the writers and the actors, how they would construct a joke, and adjust things.

When I was 17, I started doing the European Music Awards. I would go and work in the costume department, I didn’t fucking know anything about how to sew on a bun but it was amazing. I got such a solid understanding of how a production office works, how a schedule works.

Tragically, you see a lot of how an actor is a small cog in this machine. Everyone is working so diligently. This whole idea of superiority that can go on, it was important for me to witness early on. Because when you go onto set and someone says five minutes, it actually means five minutes. But it was also hard because I was watching people do what I love. I didn’t get into school, so I said fuck it, I’m gonna do a foundation for a year and reapply to drama school from New York.

sm: Why choose the Strasberg program?

oj-c: Someone told me about it. I thought I needed to go do something that gives me a playground, a space in the meantime. But when I got there, I was with this small agency, and they started sending me out on auditions. The first or second one I went on, they flew me to LA to do a screen test and I got it. This was six weeks into the program. I was like: what do I do?

sm: What did you decide?

oj-c: There were three or four movies I got, but then the financial crash happened and it all fell apart. So I went back to New York to continue with the program. But meanwhile, I had been signed to WME and my agents were like, let’s go down the studio route because that’s going to be fun. I got an audition for this Drew Barrymore movie, got that, and then I dropped out. Then got another job that moved me to LA. I was there for a year shooting and doing the prep for that.

The whole idea was that I’d do that and reapply to drama school. Then I kept on booking. It’s only in the past couple years I was like, thank fuck I didn’t stop. There were moments that I thought I needed to stop and do three years of training.

sm: Did you feel like you were missing something that other people had?

oj-c: I felt like I was back-footed. Like I had no idea what I was doing, then I realised no one does. There is no arrival point where you’re like, ‘I know how to act!’ A lot of it was becoming comfortable with learning and making mistakes. Some will hurt and some don’t matter.

sm: So you start booking jobs, and then it just keeps going? No break?

oj-c: There’s obviously periods where you’re out of work. Or you really want a job and you do 50 auditions for it and you don’t get it. A lot of that went on. But I was 22. I ended up staying in New York until I was 28. I felt like a deer in the headlights. I was just so grateful that I was working and that people wanted to hire me that I never stopped to ask if it was actually fulfilling.

I listened to a lot of people early on. I needed guidance. I needed someone to say, do this job, this will lead to this, or it’s important you work with this person. Then I woke up one day and was like, is there anything here that I’m actually proud of?

That comes with experience and maybe a little bit of delusional confidence where you go, I think I want to try and do something here that is more aligned with me. It was a weird time to be in LA. I’m six foot three. I look a certain way. People wanted the product. I thought that was how I’d get there. I’ll pretend to be confident, I’ll be a version of what these people want. Keep my mouth shut and pretend. I reached a point where I was like, I cannot keep going this way.

sm: Did you feel that you’d abandoned yourself? Or was it a slow realisation?

oj-c: It became harder and harder to pretend to be this chill guy. I’m not chill. But when you’re handed something, you go, this is fun. Then the more you read and become accustomed to the environment you’re in, you start to feel entitled to have an opinion. To feel entitled enough to say: I actually don’t like this, I actually find this quite soul destroying. Having to make myself small, or block myself off and not be as vulnerable as I feel. To not show that.

It was an interesting time – in the late 2000s, men were men and what I was being asked to do was be an idea of what a tall, white, masculine man was that sort of never really sat. I actually feel really fragile. So I took a break for six months. I was like, I’m just going to say no now and try to re-shape the direction of what I want to do. Then The Haunting of Hill House came along.

sm: How did that audition happen?

oj-c: I’d done a film with the producer before. They sent me a conversation that happens in the show between Luke and his twin sister, it was him asking her to get him drugs. They asked me to read that and literally the following day, they called me and were like yep, you.

means something to people. It was an amazing thing to be a part of.

sm: Did you immediately recognise that Luke was the kind of character you were looking to play on the page?

oj-c: Sort of. If I’m honest, I did quite a lot with the role. Mike was very open to collaborating. I put a lot of stuff in there that wasn’t necessarily there originally.

All of the siblings were there but they were sort of blank canvases for anyone to put whatever they needed to put in it. We all came in and made bigger choices to create this family dynamic. They brought on this incredible writer, Scott Kosar, who wrote The Machinist, to tackle the Luke character because he was in recovery at the time.

sm: The writer was in recovery?

oj-c: Yes. He tackled all those monologues about staying clean and everything. That was him. You know, you’re talking about a family that lived in a haunted house, that’s sort of a silly premise but all the substitutions that everyone did, it was all about trauma. Living and being followed by things unless you face them.

sm: What did you bring to the Luke character that wouldn’t have been there if somebody else played it?

oj-c: Someone else would have brought something amazing to it. But Mike Flanagan had so many tapes come through of people playing the addiction, and you can’t play the addiction. When I first looked at Luke I was like, okay, he’s a heroin addict, but then I was like, actually, to put a label on that, to label him, does such a disservice.

So it became about what he was running from, and what was terrorising him. For me, it became about childhood sexual abuse. How do you escape this thing you don’t want to feel? And if you can’t keep it at bay, it will take over. It became about that struggle, not ‘I need my fix.’ It became about this terrorising thing that’s always present, which translates into the show. We all have things that follow us. It became about trying to humanise it and make it real by using that as a way in.

sm: You’ve been open on social media about the sexual abuse you faced as a child. How did you navigate acting something so close to home?

oj-c: I’m of the school of thought: use whatever is real for you. That’s why I do the job. A lot of us use our own personal experience, but we bring it to a safe space where it’s okay for us to experience it. In a way it calls for that, and it felt important to do for the show.

I come back to this idea of needing to stop and reassess what I wanted to do, where I wanted to go, and what I wanted to say in the work that I do. I felt like I couldn’t keep hiding. We’re all complicated, we’ve all had complicated upbringings. That’s just part of life. It’s unfortunate, but it’s sort of always going to be a mess. I needed to put everything that I felt into something. I do that all the time.

We use the parts of yourselves. Including the darker parts, and some of the stuff we don’t want to look at. I’ve never been one of those people to go half on something. You either do it or you don’t. There’s no middle ground. I’m not going to half step in, or pretend.

sm: Did you have any practices while filming to help you not carry the hurt from that world into your own?

oj-c: What was interesting was that all of that sadness was in there anyway. I wasn’t generating any of it, I was just opening it up. I didn’t whip myself up into a frenzy. It just felt like I didn’t have to hide, or pretend it wasn’t there.

sm: Would you say acting has been healing for you?

oj-c: I don’t think the word healing is correct. But it’s been incredibly helpful in helping me understand myself better. It’s probably not the healthiest but I’ve said this before, I feel like I need the job to lay out all my neuroses and vulnerability. I keep myself so closed off in real life. It’s an outlet that feels necessary. That’s why I go off to work every couple days.

sm: You are cast in a lot of thrillers and horrors. Why do you think you mesh well with that genre as an actor?

oj-c: You know, after I did Haunting of Hill House, it was sort of this big thing where the amount of horror scripts that came through was crazy. The amount of, ‘do you want to play a drug addict?’ It’s incredible how desperate people are to put us into boxes.

After Hill House, I did The Invisible Man. That was a horror but the messaging - we’re talking about gaslighting, we’re talking about toxic relationships to an extreme. It was so much more than a scary film. It felt like it had something to say. That’s the thing about horror. When it’s done well, it’s incredibly impactful.

sm: After Hill House, did you feel you had agency when choosing your roles?

oj-c: To a certain extent. But no matter where you’re at: the job you want, they don’t want you. You can be Julianne Moore, but they’d rather have someone else. It’s constant. But it did change quite a lot. In terms of becoming Netflix famous, which is the strangest, most intense thing ever because you’re the most famous person on the planet and then something else comes out. I felt like I was in a fortunate space where I could choose more, but there were films that I really wanted that I didn’t get.

sm: I heard that when you first read the Jackdaw script, you didn’t think you were right for the role?

oj-c: Yes. I called the director Jamie Childs and told him he was nuts. Because again, here’s this hyper masculine man that felt quite robotic on the page. I met Jamie on the set of Wilderness. He was telling me, ‘I’ve written this movie. I’d love to get your feedback on it.’ So I read it. It was still an early draft. Then he said, ‘Do you want to do it?’ I genuinely thought I wasn’t the right fit. I thought it was just out of convenience that he wanted me.

He said to me, ‘It needs someone to come in and make it human. To give it vulnerability.’ He said the film is about how this man readjusts his life following the death of his mum, and I was like, sold! You need some tears? I’ll bring you tears! I’m never leaving my sad boy era. It happened so quickly. We wrapped Wilderness, and then started filming three and a half weeks later. We were up north in January.

sm: You go swimming in the North Sea quite a bit in the film…

oj-c: Oh yeah. It got to like minus nine. It ended with me getting hypothermia. I think I’m a bit too delicate, that’s why. I had this amazing stunt guy called Jamie Dobbs who’s this gold motor-cross champion, and we had to shoot all this stuff of us in the night. They’d get me on a rig, and then they’d get Jamie and it got to minus 12. He got frostbite on his face. It was unbelievable. It was all night shoots. I am so surprised we all made it out alive.

sm: Had you ever cold plunged before?

oj-c: Not at all. I’m one of those people in August that’s like, I don’t know if I want to go in the sea, it looks a bit cold. We did three days on the water. Some of it was in a kayak. The underwater stuff, that’s where it got brutal. We were all eating every 25 minutes because we were so cold. There was a boat just for food. I couldn’t name one thing we ate. It was just fuel. We were going to work at 5pm, and then wrapping in the morning.

sm: Do you often try new things on film sets that you’d never do otherwise?

oj-c: Yes, all the time! That’s part of the allure of it. You get to learn all these weird things that you’d never do. You get to experience these amazing things. I’ve been doing this for so long, because I’m 150 years old, and someone will bring something up and I’ll be like, oh I’ve done that! But then I’m like wait no I didn’t, the character did.

sm: Was there anything else you learned on the set of Jackdaw? Motorcross?

oj-c: Yes! I fucking loved it. If I’m honest, a lot of it is me jumping on and starting up and then getting out of frame. Insurance-wise, I couldn’t do any of the jumps or anything. But it is so great. There is nothing quite like it.

sm: Do you ever think you’ll get into the writing side of film?

oj-c: I have. I just don’t know what I have to say yet. Everyone reaches a point where they think, I don’t want to forever be a product. It would be nice to be part of the creative. I have a lot of opinions.

You go into a job with the best intentions. This is what they’ve told us, this is what’s been sold and then you’ll see the final product and be like: that’s not at all what I thought it would be. The more you do it, the more you feel like you know what you actually like and what you want to be part of. I’ll get to it at some point.

Jackdaw is in cinemas now.

#oliver jackson-cohen#oliver jackson cohen#jackdaw#jackdaw film#jamie childs#2024#interview#cw: csa#mike flanagan#haunting of hill house#luke crain#jack dawson#i have that home alone anecdote memorised by now 😭#he writes!

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poppy Hill

A screaming Meemie

#poppy hill#pinterest#pinterest aesthetics#aesthetic#black aesthetic#red aesthetic#the haunting of hill house#the haunting of hill house aesthetic#luke crain#hugh crain#olivia crain#steve crain#shirley crain#theo crain#theodora crain#nell crain#ghost#ghost aesthetic#screaming meemies#flapper

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE

1.06 “Two Storms”

She is grieving in her own way.

#the funny sibling in the family#the haunting of hill house#mike flanagan#theo crain#shirley crain#luke crain#steven crain#thohh

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mike Flannigan you’ve done it again (i’ve been sobbing violently for the last hour with no signs of stopping soon)

#the haunting of hill house#the haunting of bly manor#steve crain#nellie crain#luke crain#theo crain#shirley crain#mike flannigan#flanaverse#victoria pedretti

110 notes

·

View notes

Photo

endless favorites ♡ luke & nell (the haunting of hill house)

“i was born 90 seconds before nell, but she was always my big sister.”

#DO NOT TAG AS SHIP#this is not a ship edit!!!!!!!!!!#luke crain#nell crain#the haunting of hill house#thohhedit#thehauntingedit#hillhouseedit#**#mine:haunting#*favs#my angel twins#thohh#*1k

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

MIKE FLANAGAN UNIVERSE SERIES MEME: [2/5] dynamics / relationships

Luke Crain & Nellie Crain

⇾ I was born 90 seconds before Nell. And, uh... I'd use that to, you know, if we had a fight, or, um... if I wanted something, I'd say I was the oldest, so... she had to do what I said. And... And she let me get away with it. I mean, even though she knew it was bullshit. The last time I saw her, she, um... she was driving me to rehab. So she... she dropped me off. And she... she looked at me and she said, "You go in there and you bring my brother back. Bring my brother back."

I was born 90 seconds before Nell... but she was always my big sister.

#the haunting of hill house#thohhedit#mikeflanaganuniverse#nellie crain#luke crain#nelliecrainedit#lukecrainedit#horroredit#tvedit#horror tw#mfum#myedits

756 notes

·

View notes

Text

rewatching Hill House with lewis and god like. thinking about how luke as an addict has NONE of the same fancy treatment that Nellie gets, we don't see anyone delving into the underlying REASONS he is an addict

and not just the poverty compared to his siblings but like

the trauma of hill house. we see nellie seek out a fancy sleep therapist in a sleek beautifully made up office, and separately is in a sleek fancy psychiatrist's office and speaking to him in one on one sessions

because luke is an addict he doesn't get that. because luke is an addict and is automatically blamed for everything BECAUSE he's an addict, bc he's automatically seen as evil and Wrong inside, everything is about what HE'S done wrong, the amends HE needs to make

and of course he's fucking hurt them, but a heroin addiction doesn't come from nowhere - esp bc we see him as a young boy with bad vision who struggles with his letters in a way that his sister doesn't at the same age, who comes off as quite a bit younger than nellie in some ways

yes, he's naïve in a way that nellie isn't as a child (although they obviously swap roles as adults), yes he doesn't do well assessing risk, but like

the thing about that is that. theo has a PhD in behavioural science or whatever

shirley is a mortician, steve is a successful author, nellie is a fucking PHOTOGRAPHER and like

nell is also naïve as an adult but bc she has that creative streak she's able to cobble whatever living together and access fancy care

but luke? steven basically laughs at him when they talk about him being able to write a story and the work being good. no one cares about luke. everyone is frustrated with nell's naivety but she gets a lot of slack that luke doesn't because she's not an addict

and i just think about how. luke doesn't get into art or a fancy career like any of his siblings do. he doesn't find a focus or an obsession. he doesn't develop support or loving connections. he's there, ripped open and traumatised like they are, with nothing to stem the wounds

of course he turns to fucking heroin. what else does he have? and then what little he DOES have goes down the drain as he spirals further and further, he steals from his siblings, he erodes those relationships to nothing, they see him as an inconvenience, they treat him cruelly

like. real talk.

can luke, as an adult, even fucking see very well?

bc baby luke has glasses that are thick as anything, and i KNOW that my man isn't carrying his contact case from alleyway to alleyway and shitty shelter to slightly less shitty clinic

MAYBE he's had corrective eye surgery. maybe he's just given up, because he can't get a job like his siblings anyway so why does it matter? he'd only lose his glasses anyway

but fuck it just. kills me.

like just the blaming luke for everything he's suffering when they're all insane and all traumatised, they're all DESTROYED

but they all acknowledge they're fucked up cos of the house... except luke. it's luke's fault, bc he's an addict

292 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Haunting of Hill House in red

if you have a request or want to be tagged for any of my edits send me an ask. don’t repost, reblogs appreciated. all of my edits can be found here

#the haunting of hill house#thohh#thohhedit#nell crain#steven crain#luke crain#shirley crain#theo crain#poppy hill#olivia crain#hugh crain#william hill#dana's edits

52 notes

·

View notes