#makie lacquerware

Text

Antique Sakazuki Sake Cups

+SHOP+

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

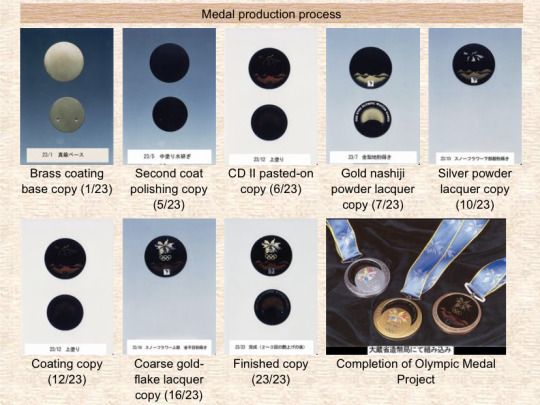

The Nagano Olympic medals combined the Maki-e techniques of sprinkling gold and silver powder on a pattern drawn in lacquer, the cloisonné technique of baking vitreous enamels, and the use of photographic technology in the metal processing.

“To convey local characteristics, the 1998 medals were created in Kiso lacquer. The decoration technique adopted was embossed gilding with shippoyaki (i.e. cloisonné techniques) and precision metalwork. The obverse represents the rising sun in Maki-e, surrounded by olive branches and accompanied by the emblem in cloisonné. The reverse is mainly in lacquer. It represents the emblem of the Games in Maki-e, with the sun rising over the Shinshu mountains. The lacquered parts were done individually by artists from the Kiso region.” (Source)

“The Lillehammer Olympic medals were wonderful, created on a theme of symbiosis with nature using stone cut from ski jumps. For the 1992 Albertville Olympic Games held in France, the medals were made of crystal and were representative of France. Looking back now, it was only natural that for the Olympics in Nagano, I would think, Let’s make medals using lacquer, a representative craft of Japan. Let’s fuse lacquerware techniques with Nagano Prefecture’s precision machining technology.” (Source)

#far and away the prettiest winter olympic medals.#i like the 92 albertville lalique glass medals but sochi 2014 did the transparent concept so badly#nagano#nagano 1998#winter olympics#lacquer#lacquerware#maki-e#makie#kiso#1998#1990s#shippoyaki#cloisonne#metalwork#shinshu#japan#fave

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The golden leaves on this tea caddy are fantastic examples of the technique. To obtain this perfect gradation and shading requires keen skills and a wealth of experience. Master craftsman Kazumi Murose has both. Now considered a living national treasure in Japan, Murose is dedicated to the promotion and practice of traditional lacquerware skills. This flawless piece is available from the Onishi Gallery.

0 notes

Photo

New arrival! Vintage ojubako, 3 story lacquer box❤️ Urushi lacquered natural wood with dynamique gold makie painting. Now available on our online store and at our Parisian boutique. Our boutique will be closed from March 3 to 9. Our online store remains open and click & collect will be on appointment. We will be back on March 10 at 11AM! #maisonsatoparis #lacquerware #japaneselacquer #japancraft #vintagelacquerbox #makie #laquejaponaise #お重箱 (à Paris, France) https://www.instagram.com/p/CpQTaAzNdzV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Ingrandimento del dettaglio di una lacca giapponese. • Blow-up of a detail of a Japanese lacquerware. • 日本漆器の拡張された部分。 •• ©︎ @kozeroz ••• #lacca #laccagiapponese #artigianato #artiapplicate #artegiapponese #museo #makie #lacquer #lacquerware #lacquerwork #japaneselacquare #urushi #shikki #artisan #appliedarts #artsandcrafts #japaneseart #museum #rijksmuseum #modernjapaneselacquer #modernjapanslak #漆 #漆器 #日本漆器 #蒔絵 #職人技 #美術館 #cerchio #circle #円 (presso Rijksmuseum) https://www.instagram.com/p/CoESbazPWSP/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#lacca#laccagiapponese#artigianato#artiapplicate#artegiapponese#museo#makie#lacquer#lacquerware#lacquerwork#japaneselacquare#urushi#shikki#artisan#appliedarts#artsandcrafts#japaneseart#museum#rijksmuseum#modernjapaneselacquer#modernjapanslak#漆#漆器#日本漆器#蒔絵#職人技#美術館#cerchio#circle#円

0 notes

Photo

Katsuhiko Urade (浦出 勝彦) - 蒔絵箱「紅葉葵」/Maki-e box [Scarlet rosemallow]

{Lacquerware}

114 notes

·

View notes

Photo

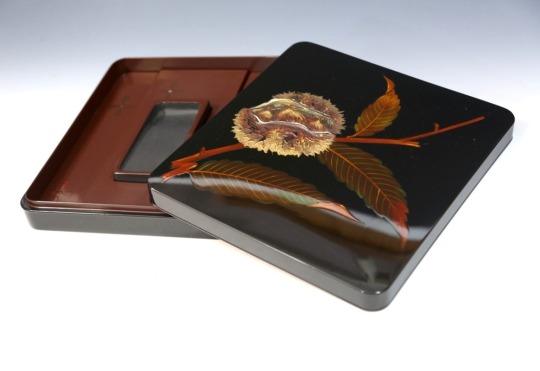

Makie lacquerware with chestnut design

83 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ancient Japan period series REVENGER by Nitroplus will be getting a new Nendoroid of maki-e lacquerware artist, Yuen Usui! Extra props will include some his works, a coin and a sheet of gold lacquer for "other" uses!

Release Date: September 2023

Pre-order: on Aitaikuji

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

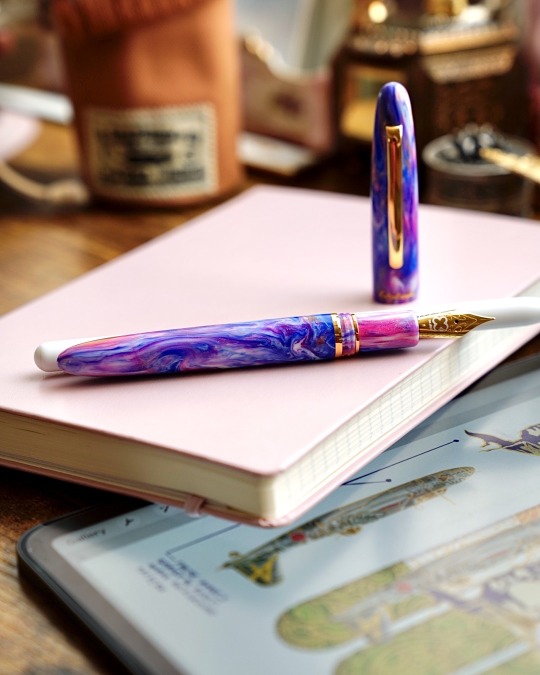

Thought I’d share this custom India-themed Maki-e design for a Namiki 50 I created for one of my clients. I’m on a pretty strict no buy, actually, and this customer was kind enough to trade me a custom design in exchange for a grail MontBlanc fountain pen I’ve been wanting! ✨

“Maki-e (蒔絵, literally: sprinkled picture (or design)) is a Japanese lacquer decoration technique in which pictures, patterns, and letters are drawn with lacquer on the surface of lacquerware, and then metal powder such as gold or silver is sprinkled and fixed on the surface of the lacquerware.”

Unfortunately, I won’t see the completed pen in person as it’s being shipped directly to my client after being painstakingly hand-painted in my design by Japanese artisans overseas. 🥹 But I can at least share these photos of the finished concept!

For the next few days, I’m head down working on another design for the same client, this time a Maki-e on a Montblanc 149. How cool is it that my art is going to be turned into Maki-e?! Insane!

And yes, I traded again in exchange for a pen. LOL. Can you tell I’m fountain pen addicted? Yeesh. You can also pay me actual money, of course. 😂 Just saying. But I enjoy the idea of trading art for grail pens. It’s just… Cool, and romantic in a way, and makes my creative heart excited that I can offer my unique skillset in exchange for something I wouldn’t otherwise be able to acquire (y’know, thanks to being on no buy, lol). That’s what stationery should be, anyway. Beautiful, and fun. 🥰💖

TGIF! I hope you all have a wonderful and blessed weekend! 🙏✨

#fountain pen#fountain pen addict#maki-e#maki e#custom design#art desk#artist studio#cozy desk#desk setup#fountain pens#digital art

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

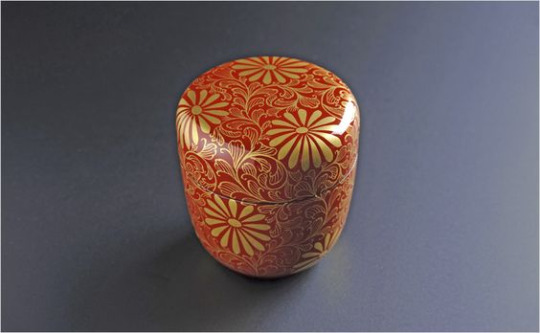

Japón laca : Resina y metales nobles (Oro y plata...)

[Utensilios de té/Utensilios de té Natsume] Medio Natsume Vermillion Gold Makie Chrysanthemum Karakusa Ryukyu Lacquerware-Azufaifo medio bermellón laca dorada crisantemo arabesco

#Japón laca : Resina y metales nobles (Oro y plata...)#¿Esta es la imagen y algunos datos (O no) la “Historia” la pones tú? ¡La tuya! ¿Lo harás...?#Japón Tradicional.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Artistry of Maki-e Fountain Pens: A Guide to Understanding and Appreciating the Tradition

Maki-e is a traditional Japanese art form that involves decorating various objects, including fountain pens, using lacquer and metallic powders. The technique is known for its intricate designs and stunning visual appeal, making it a favorite among collectors and pen enthusiasts. In this blog, we'll explore the history, techniques, and beauty of maki-e fountain pens.

A Brief History of Maki-e:

Maki-e has a rich history dating back to the Heian period (794-1185) in Japan. The art form was initially used to decorate lacquerware and other household items, but eventually made its way to fountain pens in the 20th century. Today, maki-e fountain pens are highly sought after for their unique designs and craftsmanship.

Techniques Used in Maki-e Fountain Pens:

The maki-e technique involves applying layers of lacquer to the pen and then sprinkling metallic powders on top. The powders are then fixed in place with another layer of lacquer. The process is repeated until the desired design is achieved. Maki-e artists use a variety of tools, including fine brushes and stencils, to create intricate patterns and details.

Designs and Themes:

Maki-e fountain pens can feature a wide variety of designs and themes. Some popular motifs include landscapes, animals, and traditional Japanese symbols. Some artists also incorporate gold and silver leaf into their designs for an added touch of luxury. The possibilities are truly endless when it comes to maki-e fountain pens, making each piece truly unique and one-of-a-kind.

Maki-e fountain pens are a true work of art, combining the traditional Japanese art form of maki-e with the functionality of a fountain pen. The intricate designs and stunning visual appeal make them a favorite among collectors and pen enthusiasts. Whether you're a beginner or a seasoned collector, maki-e fountain pens are a beautiful addition to any collection.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

金継ぎ Kintsugi

Kintsugi (golden joinery) is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum, a method similar to the maki-e technique. As a philosophy, it treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise. Lacquerware is a longstanding tradition in Japan, at some point it may have been combined with…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Issey Hattori

Window in the Sky

I made this piece so that people could feel the beautyof black lacquer, gold Maki-e, and inlaid mother of pearl.

Maki-e and inlaid mother of pearl are said to have been established in the Nara Period (710 to 784).

I used these techniques, which have been faithfully passed down through the generations, to skillfullycreate shapes and designs that are not typical of traditional lacquerware.

0 notes

Photo

New arrival! Vintage Wajima lacquer bowl with lid. Red lacquer with bird and kaki tree gold makie painting. For Japanese clear soup "suimono", little pastry, decoration or a gift for your loved one? It’s up to you how to use it for❤️ Now available on our online store and at our Parisian boutique! #maisonsatoparis #lacquerware #japaneselacquer #japancraft #bowlwithlid #wajima #makie #laquejaponaise #vaissellejaponaise #漆器のある暮らし (à Paris, France) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cl8YPXWI4FU/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#maisonsatoparis#lacquerware#japaneselacquer#japancraft#bowlwithlid#wajima#makie#laquejaponaise#vaissellejaponaise#漆器のある暮らし

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (65a): Concerning the Vessels in which the Kaiseki is Served¹.

65) The vessels used when serving the food that accompanies tea should surely be new and spotlessly clean². Supposing that the bowls and oshiki [折敷] are things like Negoro [根來] and Yoshino [芳野 = 吉野] lacquerware: it is important for them, too, to be new; and if so, there will be no problem with even bringing such things out into the presence of noblemen and persons of high rank³.

Also, with respect to things like the oshiki, even if they are wonderfully beautiful [examples] of antique makie [蒔繪], or nashiji [梨子地], or else [imported] Chinese pieces [whether new or old] -- as well as hegi-date oshiki [such as are used when presenting offerings to the Shintō deities] -- none of these should [ever] be placed underneath [the meal]⁴.〚And in the [spirit of] wabi, the oshiki may even be done away with entirely⁵.〛

[Nevertheless,] in recent days many people have begun using antique oshiki of beautiful appearance [when serving the kaiseki]⁶. [When I told him about this, Ri]kyū knit his brows [in consternation, at my news]⁷.

_________________________

◎ This entry, which is more or less the same in all of the different versions* of the Nampō Roku, consists of a fairly short text passage followed by a kaki-ire [書入].

The kaki-ire, which is rather long, will be translated in the next post.

___________

*Shibayama Fugen’s and Tanaka Senshō’s texts both add one short sentence (see footnote 5). While I have included this sentence in the above translation, it has been enclosed in doubled brackets, in keeping with the convention that I established earlier in this blog.

In addition to this, a number of minor differences in language clearly show how Shibayama’s version was derived from the Enkaku-ji manuscript, while Tanaka’s genpon [原本] version was made by editing Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon [特殊写本] text in light of the literary conventions (such as using the kanji wabi [佗] for the Sōtan-preferred wabi [侘]) that prevailed around the lend of the eighteenth century. These will be discussed in the footnotes.

¹The phrase that functions as the title in the original is cha-uke ryōri no ki [茶ウケ料理ノ器]. Cha-uke [茶請け] means things (like sweets) that are served along with a bowl of tea*; cha-uke ryōri [茶請け料理], then, would refer to the food that is served during the kaiseki.

__________

*Such as in some place like a restaurant, or in one of the tea-stalls that were found along major thoroughfares.

²Cha-uke-ryōri no ki, ika ni mo atarashiku isagiyoki wo mochiiru-beshi [茶ウケ料理ノ器、イカニモアタラシクイサギヨキヲ用ベシ].

Cha-uke-ryōri no ki [茶請け料理の器], as explained above, means the vessels used to serve the food -- in other words, the bowls and oshiki that are used to serve the kaiseki*.

Ika ni mo atarashiku isagiyoi wo mochiiru-beshi [如何にも新しく潔いを用いるべし] means (one) should surely† use new and clean‡ (vessels).

Here Shibayama’s version has ki-butsu [器物] (rather than ki [器] -- both of which mean vessel); while Tanaka’s genpon text inserts a comma between atarashiku [アタラシク = 新しく] (new) and isagiyoki [イサギヨキ = 潔き] (clean), apparently with the intention of emphasizing these necessary attributes.

__________

*While Rikyū seems to have preferred to serve the meal as a bentō -- arranged in a fuchi-daka, and accompanied by a bowl of soup (from the lid of which sake was drunk) -- his practices were ignored, after his death, in favor of the larger meal that had been offered to the guests during Jōō’s middle period (a practice carried on -- despite Jōō’s own subsequent efforts to simplify things to one bowl of soup, three vegetables, and rice -- by Imai Sōkyū and his machi-shū followers).

†Ika ni mo [如何にも] means really, truly, certainly, very. In other words, the vessels used to serve the kaiseki should absolutely be (relatively) new and clean.

‡Atarashiku isagiyoi [潔い] means new and clean.

Isagiyoi means not only clean or pure, but also manly (here, the implication would be that the vessels should be sober, rather than gaudy or frivolously shaped or decorated).

So, in addition to being new (this is not to say they must be brand new, but new enough that they show no evidence of things like discoloration of the crackles in the glaze due to infiltration of food juices, nor chips or scratches or other signs of wear) and clean, isagiyoi would also suggest that the utensils should be simple, without the sort of excessive decoration that is occasionally seen in modern kaiseki vessels.

³Tatoi Negoro・Yoshino-tō no wan・oshiki mo atarashiki ga sen nari, kijin・kōi no mae ni mo kurushi-karazu [タトヒ根來・芳野等ノ椀・ヲシキモ新シキガセン也、貴人・高位ノ前ニモ不苦].

Tatoi [たとい = 仮令], here, means something like “for example,” “supposing (that).”

Negoro・Yoshino-tō [根來・吉野等] are two varieties of inexpensive lacquerware that were common during the Edo period.

Negoro-nuri [根來塗] is painted with two coats of lacquer, one red and one black. Sometimes the red coat is outermost (as seen in the example on the left), and sometimes the black coat is on the outside. In either case, the outer coat of lacquer is usually polished down to reveal the inner coat here and there (which produces a sort of informal decorative effect), as can be seen in the photo.

Yoshino-nuri [吉野塗] is also usually painted with two coats of lacquer, both of which are the same color -- either black or red. When dry, a simple, somewhat abstract, decoration is painted on in the opposite color.

Tatoi Negoro・Yoshino-tō no wan・oshiki mo atarashiki ga sen nari [たとい根來・吉野等の椀・折敷も新しきが專なり] means “for example, things like Negoro and Yoshino bowls and oshiki* (may be used) -- provided they are new.”

Kijin・kōi no mae ni mo kurushi-karazu [貴人・高位の前にも苦しからず] means “there is no problem about bringing vessels of this sort into the presence of noblemen and persons of high rank.”

The reason for this statement is because Negoro and Yoshino lacquerware were usually produced for the use of the lower classes, hence many people would feel reluctant to serve persons of high rank using such things.

Here, Shibayama’s text has tatoi Negoro, Yoshino-tō no oshiki ni te mo, atarashiki ha kijin-kōi no go-zen [h]e dashite mo kurushi-karazu [タトヒ根來、吉野等ノ折敷ニテモ、新敷ハ貴人高位ノ御前ヘ出シテモ不苦]. This means “for example, things like both Negoro and Yoshino oshiki† (may be used); and there is no problem with bringing such things into the presence of nobles and persons of high rank provided they are new.”

So what this version is arguing is that oshiki made of Negoro or Yoshino lacquer can be used even when entertaining persons of the highest status, provided that they are brand new. This is the meaning that the Enkaku-ji scholars concluded was intended by the author.

Meanwhile, Tanaka’s genpon text has tatoi Negoro-nuri ni te mo, atarashiki ba, kijin-kōi no go-zen [h]e dashite kurushi-karazu [タトヒ根來ヌリニテモ、アタラシクバ、貴人高位ノ御前ヘ出シテクルシカラズ]. This version means “supposing (the vessels) are of Negoro lacquer, provided they are brand new, there is no problem with bringing (such things) into the presence of even noblemen and persons of high rank.”

This is the way the line was printed in the block-printed revised edition of the Nampō Roku published at the end of the eighteenth century. By looking at all three versions side by side, we can see how this idea evolved between the late seventeenth century (when this text was surreptitiously added to the Shū-un-an cache of documents -- probably by someone acting on behalf of the Sen family) and the version published a century later.

___________

*An oshiki [折敷] is a sort of tray-table, originally used when presenting offerings to a Shintō deity. Originally the foot consisted of a box of similar make, usually with openings cut in the four sides (to make the piece appear lighter) -- this kind of kami-oshiki [神折敷] is shown in the fourth photo under footnote 4, below.

By the Edo period, those used for serving food, as here, generally had four (or sometimes two) legs -- as can be seen above in this photo of a set of five Negoro-nuri oshiki from the late eighteenth century. (A hegi-date oshiki with two legs is also shown in the above-mentioned photo under footnote 4.)

Sometime between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries trays without legs came to be preferred by the modern schools derived from the Sen schools (even though they continue to refer to them as oshiki), while the daimyō schools continue to use footed oshiki.

†The fact that the word wan [椀], bowls, is missing from the latter two versions of the text is curious.

During the Edo period, as pottery became more widely available, simple bowls and dishes made of white clay (covered with a clear, colorless glaze, similar to what is seen in the vessels used on kami-dana [神棚] today -- these vessels are shown in the above photo) were sometimes used for chanoyu -- their low cost meaning that they could be replaced easily as soon as they started to look “used” -- and the omission of the word wan (from the list of lacquered things) might reflect the increasing frequency with which the use of such vessels was spreading throughout the tea community during the eighteenth century.

The Sen family, however, seems to have always continued with their preference for lacquerware (which, in Rikyū’s day, was much cheaper, and more readily available, than pottery).

⁴Oshiki-rui mo, ika-yō ni mi-goto-naru furuki-makie・nashi-ji, mata ha kara-no-mono ni te mo, hegi-date no oshiki ni shiku-bekarazu [折敷類モ、イカヤウニ見事ナル古キ蒔繪・梨子地、又ハカラノ物ニテモ、ヘギタテノヲシキニシクベカラズ].

Oshiki-rui [折敷類]* means things of the same class or category as the oshiki. This would seem to means lacquerware trays and objects of that sort.

Mi-goto-naru furui makie・nashiji, mata ha kara-no-mono, hegi-date no oshiki [見事なる古い蒔繪・梨地、又は唐の物にても、片木立の折敷] is enumerating the various sorts of oshiki:

◦ makie [蒔繪] means the object is usually painted with shin-nuri, on top of which a design is painted in red lacquer over which gold dust is sprinkled while the lacquer is still tacky, resulting in a decoration of gold against the black background -- here the text specifies that it is antique examples of maki-e work that should not be used;

◦ nashiji [梨地] is a more elaborate type of lacquer in which flecks of gold are suspended in a clear lacquer (the effect resembling the mottled skin of a Japanese pear) -- again, the text argues that it is antique specimens of nashiji that are proscribed;

◦ kara-no-mono [唐の物] means pieces of continental make, which (as a class) would include numerous sorts of lacquer work (in addition to techniques such as makie and nashiji, these included raden [螺鈿], mother-of-pearl inlay, and tsui-shu [堆朱], carved lacquer, among many others, as seen above) -- these should not be used, whether new or old, because their rarity (and commensurate value) would distract the guests from their meal†;

◦ hegi-date no oshiki [片木立の折敷] are oshiki made from split-wood -- the wood was split into thin sheets using a pair of fork-like tools which results in a slightly rough surface (it could be sanded smooth, but was usually left in its natural state): this kind of oshiki were produced for use when making offerings to a Shintō deity, and this is why they were judged to be inappropriate for use in the tearoom‡.

Ika-yō ni...shiku-bekarazu [如何様に...敷くべからず] means whatever it may be...none (of these sorts of oshiki) should be used underneath (the food that is served during the kaiseki).

In other words, this text is saying that only newly-made lacquered oshiki of the most simple sort -- those of Negoro and Yoshino lacquer, for example -- should be used. Elaborate antiques, treasured imported pieces, or unpainted wooden oshiki of the sort used when presenting offerings to the Shintō Gods -- none of these are appropriate for use in this way.

Here, both Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon and Tanaka’s genpon text deviate markedly from the (earlier**) Enkaku-ji version of the text.

Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon has ika-yō ni mi-goto-naru furui makie, nashiji, arui ha kara-no-mono ni te mo, furui wo mochiiru ha ikenai, hegi-tate no oshiki ichidan yū nari [イカヤウニ見事ナル古キ蒔繪、梨子地、或ハ唐ノ物ニテモ、古キヲ用ルハ不好、ヘギタテノ折敷一段尤也].

This means “no matter how splendid the old makie, nashiji, or kara-no-mono, are, old [pieces] should not be used [to serve the meal]; [but] hegi-date oshiki are even more appropriate.”

Apparently this shift in preference for hegi-date oshiki reflects the emphasis on purity and newness -- since hegi-date oshiki, by convention, were used only once.

Meanwhile, Tanaka’s genpon text reads ika-hodo migoto no makie, nashiji, arui ha kara-no-mono ni te mo, furui wo mochiiru ha ikenai, hegi-date no oshiki ichidan yū nari [イカホド見事ノ蒔繪、梨地、アルヒハ唐ノモノニテモ、古キヲ用ルハ不好、ヘギタテノ折敷一段尤ナリ].

This version, in translation, is almost identical to Shibayama’s text: “no matter how wonderful the makie, nashiji, or kara-no-mono might be, it is displeasing to use old [pieces]; [however] hegi-date oshiki are even better [than newly-made lacquered pieces].”

The differences between these two versions are idiomatic, rather than substantive.

__________

*The kanji rui [類], which is used to mean a class or category, a grouping of objects that share a common property of some sort (such as being made from lacquer, or the objects that are arranged on a nagabon and used to prepare tea, to give two examples showing the range of potential usages for this term) is only found in this last group of entries in Book Seven, suggesting that they were authored by the same person near the end of the seventeenth century.

This word rui became somewhat fashionable in machi-shū writings after the middle of the seventeenth century, probably as a reflection of their shared mercantile background.

†Because of the concern that the fire will burn too far, and so begin to fail during the service of tea, nothing should be done that would distract the guests, and encourage them to dawdle.

This is why Rikyū preferred to limit the service to a bentō-style meal, served in a plain black-lacquered wooden box.

‡The hassun [八寸] tray, shown above, is traditionally a sort of hegi-date oshiki (that lacks legs). While the textured surface of the face of this tray was originally the result of the wood being split into thin strips using a pair of metal forks, today the lines are more commonly carved into a previously smooth-sanded during the finishing process (the reason for which appears to be to prevent the foods served on the tray from leaving distinctly shaped stains -- since, of course, modern people reuse the hassun tray rather than replacing it with a new one for each gathering).

**The Enkaku-ji version represents the text as it existed circa 1686. The toku-shu shahon was produced by one of the Enkaku-ji scholars (for personal reference) around the middle of the eighteenth century; and the (erroneously named) genpon text was edited (for publication) from the toku-shu shahon version towards the end of the same century.

⁵Wabi ni te mo oshiki ha tsukai-sute nari [侘ニテモ折敷ハツカヒ捨ナリ].

This sentence is found only in the toku-shu shahon and genpon versions of the text, meaning that it was added to the original text later.

Wabi ni te mo oshiki ha tsukai-sute nari [ワビにても折敷は使い捨てなり] means “also in the wabi (setting), the oshiki is expendable.”

Presumably this means that, in the more wabi settings, the small meal-tables could be substituted with trays (as is the general preference today*), or other ways of serving the meal (such as using a fuchi-daka, as did Rikyū; or the Shōkadō-bentō [松花堂辨當] that was created specifically for this purpose†).

The only difference between the two versions of this sentence is that Shibayama's toku-shu shahon uses the kanji wabi [侘]‡, which is how Sōtan wrote the word, while the genpon text has wabi [佗] -- the obscure kanji that, since it was not employed otherwise in the general language, came to be used to represent this idea of “wabi” (in the sense intended in chanoyu) from the eighteenth century onward**.

__________

*Except for some of the daimyō schools, which preferred to use the small tables, even in the wabi setting. Their objection appears to be the idea of serving the guests’ food effectively on the floor (the way you would give food to a dog).

†The Shōkadō-bentō [松花堂辨當] was created by by the nobleman-monk Shōkadō Jōjō [松花堂昭乗; 1584 ~ 1639], based on Rikyū's way of arranging the food in a fuchi-daka. (His name is also written Shōkadō Shōjō.)

Rather than placing the various food items so that they touched the other offerings, Shōkadō Jōjō’s box separated the different things -- to keep their flavors separate (as a nobleman who, as a spare son, was sent to the temple since a political career was out of the question, he nevertheless maintained the sensibilities of a nobleman throughout his life).

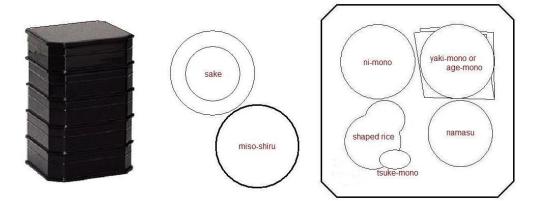

The shaped rice, accompanied by several pieces of tsuke-mono [漬物] (pickled vegetables), is placed in the front-left compartment. Namasu [膾], or some other (usually raw) dish that is eaten with sake (the so-called muko-tsuke [向付] in modern kaiseki parlance) is placed in the front-right compartment (usually on a small dish, hence the blue rim in the sketch, since this kind of food is generally dressed with a soya- and/or vinegar-based sauce). The ni-mono [煮物] (vegetables cooked in broth), again usually served in a small dish (indicated by the red rim) on account of the liquid, is placed in the back-left compartment; and the yaki-mono [燒き物] (charcoal-grilled vegetables) or age-mono [揚げ物] (deep-fried vegetables) is arranged (on a small, flat board, or sometimes a doubled piece of kaishi, to absorb the oil -- the drawing of Rikyū’s fuchi-daka, below, shows his use of this kind of folded kaishi) in the back-right compartment.

This followed the way that Rikyū arranged the same offerings in his fuchi-daka; and it represents the three vegetables that Jōō said should constitute the meal that was offered to the guests in the wabi setting. In addition to a fuchi-daka or Shōkadō-bentō, each guest was given a covered bowl of miso-shiru -- the lid of which was then used to drink the two portions of sake that were served while the guests ate the namasu.

‡The kanji wabi [侘] means disappointed, distressed, forlorn, wretched -- the emotions experienced by a social outcast.

**Rikyū, of course, always wrote wabi phonetically, as wabi [ワビ].

⁶Furuki oshiki no migoto-naru wo mochiiru-hito chika-goro ōshi [古キ折敷ノ見事ナルヲ用ル人近ゴロ多シ].

Furui oshiki no migoto-naru wo mochiiru-hito [古い折敷の見事なるを用いる人] means “the people who make use of splendid, (albeit) old oshiki.”

Chika-goro ōshi [近頃多し] means “in recent days numerous (people are doing this).”

In other words, by the last decades of the seventeenth century (which is when the original version of this entry was written), many people had already begun using antique oshiki when serving the meal. Indeed, the conventions of the time mostly argued for this kind of practice -- since chanoyu in the Edo period was all about venerating costly antiques, and lavishing large sums on the acquisition of these rare pieces*.

Here the other two versions exhibit several minor changes†.

Shibayama’s source has chika-goro furuki kara-bon nado wo mochiiru-hito ōshi [近頃古キ唐盆抔ヲ用ル人多シ]. This means “nowadays old Chinese trays, and things of that sort, are being used by many people.”

And Tanaka Senshō’s genpon has chikai-goro ha, furuki kara-bon nado wo mochiiru-hito ari [近キ此ハ、古キ唐盆ナドヲ用ル人アリ]. The meaning of this version is “as for the recent days, there are people who make use of things like old Chinese trays [when serving the meal to their guests].”

The emphasis on Chinese (or imported) trays and the like reflects the burgeoning trade between Japan and the continent -- despite the bakufu’s oppressively isolationist policies‡.

__________

*In the present day many modern-made pieces are also very costly, but this is a phenomenon that arose in the early 20th century, as a consequence of the sudden influx of large numbers of new practitioners (in other words, the women of all ages who were being encouraged to study chanoyu as a way to better their social status -- since holding a high menjō from one of the major schools of chanoyu or ikebana made the bearer highly desirable wife-material).

Prior to that time, newly made things, even by well reputed craftsmen (such as the Sen family's ten favored craftsmen), were not inordinately expensive (certainly nothing comparable to what they charge now). Indeed, this is precisely why the generations of the Raku family, and the other craftsmen, increased their output beyond the bounds of prudence after the end of the Edo period -- because, with the loss of income from the daimyō (and the focus on the hording of antiques that arose among the wealthy business class once the danger of these treasures moving abroad became clear), they had to virtually go begging for their day to day subsistence. (And, in order to support their current prices, this is why the present generations of those craftsmen often declare authentic pieces fake, as a way to limit their numbers.)

†The grammar of the Enkaku-ji version is admittedly a little weird -- and potentially confusing. The other two versions say much the same thing in notably nicer Japanese.

‡Indeed, it could be argued that it was precisely this official isolationism that made foreign products all the more tantalizing, and their acquisition more and more seductive -- to those who could afford them (and to those who could not).

⁷Kyū, mayu wo hisomeraru [休、眉ヲヒソメラル].

Mayu wo hisomeru [眉を顰める]* means to knit one’s brows (in perplexity or consternation).

Rikyū is clearly concerned about the increasing popularity of sort of deviant behavior that he is neither able to accept or condone.

__________

*Hisomeraru [顰めらる], as found in the Enkaku-ji and toku-shu shahon versions of the text, and the genpon text’s hisomerare-shi [顰められし], are archaic forms that have the same meaning, in English, as hisomeru.

0 notes