#murdermetamay

Text

I love Thiago so much he’s so fun. Problem Human Of The Week, but unlike your usual Problem Human, Murderbot wants to like him and it wants him to like it. and therein is the tension. otherwise it could just write him off as just another irritating disappointing client who causes issues and doesn’t listen and thinks negatively of SecUnits.

he’s part of the Network Effect™️ of human relationships! Ok! he’s an example of of Murderbot’s more mundane challenges re: social/society integration, the very typical challenges involved with like. professionalism. family dynamics. etc. and the issues between Thiago and Murderbot are very much these more mundane issues, like “I don’t trust your security calls because I don’t trust the culture that gave rise to you and put guns in your arms and I don’t like how anxious Mensah is and I think you’re contributing to her anxiety.” as opposed to “yikes SecUnits scary.” which tbh I don’t get the sense is really on Thiago’s radar. he’s like so sheltered that SecUnits aren’t part of his experiences really.

and yeah he fucks up at the start of the book but he learns also? he listens to Murderbot when they talk it out later and reconsiders his opinions when new information comes up about the danger Mensah was in? and by the end of the book he’s fully advocating to protect Murderbot from people crowding it and pushing Feelings Talk on it while it is fucked up (rescued after squashed by ag-bot and strung up in alien pit etc). I mean he’s overridden by Ratthi who is a level 10 Murderbot Friend who understands that this Feelings Moment (letting MB know just how much ART and everyone care about it and went to rescue it specifically because he knows Murderbot has Emotional Issues and could benefit from a reminder that everyone really cares about it). But like Thiago had the spirit. He was just level 1 or 2 at this stage.

that’s character and relationship Growth! Thiago is not #1 man (Ratthi is #1 man) but he’s an important part of the team and he’s got his own hangups and idiosyncrasies and willing to learn and grow.

me seeing fictional characters navigate interpersonal drama like adults: now this is the real escapist fantasy. oh also sick killware clone baby.

#murderbot#murdermetamay#Thiago haters dni#<- I say this in humor but I’m so forreal don’t step on my Boy he’s trying and he’s an important member of the Murderbot’s Human Squad

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I did know was that Abene really had loved Miki. That hurt in all kinds of ways. Miki could never be my friend, but it had been her friend, and more importantly, she had been its friend. Her gut reaction in a moment of crisis was to tell Miki to save itself.

After I checked the charges and ammo in the bag, I found a fake pocket in the bottom. Inside it were several sets of identity markers and a larger, different brand of memory clip from the ones I had stored in my arm. I heaved myself upright, and found a reader in the cargo console.

Well, that was interesting.

I hate caring about stuff. But apparently once you start, you can’t just stop.

I wasn’t going to just send the geo pod data to Dr. Mensah. I was taking it to her personally. I was going back.

Then I laid down on the floor and started Rise and Fall of Sanctuary Moon from episode one.

It is very noticeable to me that immediately after Murderbot concludes that Miki really was Don Abene's friend, that Abene really cared about Miki, that their relationship was one of mutual respect and care, that it is possible for humans and bots to have that kind of relationship... that Murderbot immediately jumps to, actually I do want to see Dr. Mensah again. I'm gonna go back and see her in person. Anyway I'm not going to examine this train of thought any further now. Sanctuary Moon time.

The logical through-line is pretty stark, though. Even if Murderbot doesn't want to admit it, even to itself.

#The Murderbot Diaries#Rogue Protocol#MurderMetaMay#something I was reminded of while writing my longer piece

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friend Like Me: Murderbot's Relationships With Other AIs throughout The Murderbot Diaries

It’s important to me that the thematic core of The Murderbot Diaries is not only about determining what it means to be a robot person in a human world, but about showcasing so many ways to be a robot person in a human world. And about building relationships with other robot persons to support that self-actualization as both a robot and a person.

So often, in science fiction about robot personhood, the robot character is the only robot in the cast. Not only that, so often the robot character is the only robot they know.*

When media thinks about AI personhood, or Ais as characters in society, the AI character is often alone. Alone, and different. It’s a potent allegory for what it feels like to be an outsider, to be “other,” to feel “off” from the people around you. Whether a sympathetic friend or a scary unknowable villain, a lot of people can relate to feeling like that.

The Murderbot Diaries is doing something interesting, then, by showing us our protagonist Murderbot, the prototypical robot-among-humans, the robot as a parallel for queer and neurodivergent and outsider-cultural experiences in a world of expected norms, the robot with human friends, the one robot member of an otherwise all-human team… and it can’t live like that. So it leaves.

So far, the series feels split into two halves: the first four books, about Murderbot learning different ways to be a robot in relationships with humans, and the next three** about Murderbot learning different ways to be a robot in relationships with other robots, and a robot in a mixed society.

In All Systems Red, Murderbot starts off painfully alone. It repeatedly sees other SecUnits as enemies, and believes that SecUnits can't trust each other because they're all under control of humans. It has a very low opinion of SecUnits, including itself. Murderbot hates being used by humans for violence or for petty reasons, and admits that it wants to half-ass its job.

In Artificial Condition, Murderbot meets ART, a university research ship who loves its crew and loves its function. It is also free to be a snarky asshole, as Murderbot repeatedly notes (and assigns in its very name). This relationship to humans—genuinely caring for its crew, genuinely wanting to participate in its research and teaching function—is a very different relationship than Murderbot has had, though ART still needs to keep its intelligence and personality hidden from most humans for its own safety. Conversely, this is the book where Murderbot meets a ComfortUnit that is blatantly being abused and misused by its human owner, and it hates her. The contrast between ART and the ComfortUnit displays very different ways of Ais relating to their human “owners”—and what it means for them to get what they want out of life.

In Rogue Protocol, Murderbot confronts this theme most directly, with the bot Miki. Unlike the implications of secrecy we get from ART, Miki is not hidden from anybody; unlike with the ComfortUnit, Miki is a respected and equal member of its team. Murderbot has a very hard time believing that Miki is anything but a patronized “pet bot” to these humans, despite the evidence that the humans genuinely consider it a friend and teammate. Miki has never been abused, and never had to hide. Murderbot has a hard time accepting that this is a way bots and humans can relate to each other.

But Miki is still, in the classical sci-fi robot-on-a-human-team way, unique; it expresses to Murderbot, “I have human friends, but I never had a friend like me.”

This is a much better way of being a robot among humans than Murderbot has seen before, but it’s still not the ideal Murderbot wants, either.

Exit Strategy brings the theme full-circle and the quartet to a close. Murderbot faces off against a Combat SecUnit (or CombatUnit; Wells seems to change her mind about this). The Combat SecUnit represents everything Murderbot has rejected being, everything it has overcome on its journey of self-actualization. During their fight, the CSU rejects Murderbot’s offers of freedom, money, a fake ID, the opportunity to get out of its situation the way Murderbot has; it ignores the offer. Murderbot asks the CSU what it wants. The CSU replies, “I want to kill you.” The CSU represents the kind of SecUnit Murderbot does not want to be, the kind of robot it used to think it would inevitably be but has now seen so many other ways it can be. Murderbot says in the same scene, “I’m not sure it [the offer of freedom] would have worked on me, before my mass murder incident. I didn’t know what I wanted (I still didn’t know what I wanted)…” But at the same time, the confrontation makes it clear: Murderbot knows some things it doesn’t want, and the CSU is embracing everything Murderbot doesn’t want about being a SecUnit.

If this quartet is about what it means to be a robot, and to be a robot among humans, then the next set of books (Network Effect, Fugitive Telemetry, and System Collapse) is about being a robot among other robots, and a robot in a society that supports both humans and robots.

Fugitive Telemetry makes this most obvious, with its plotline about the free bot community on Preservation. Murderbot is uncomfortable around them in a similar way that it was uncomfortable around Miki. The Preservation bots are happy, fulfilled, responsible, mutually supportive, and have a meaningful community with both humans and each other that does not match Murderbot’s experiences of what being a bot, or being a bot among humans, means.

Network Effect brings Murderbot back into contact with ART, and introduces a new SecUnit, Three. Murderbot navigating its relationship with ART as a free agent and after a perceived betrayal is a huge part of the book. Murderbot’s disembodied-software-fork Murderbot 2.0, freed from much of Murderbot’s organic anxiety, shows itself much more willing to be social with other bots and constructs. System Collapse follows, bringing further depth and complexity to Murderbot’s relationship with ART and expanding its interactions with Three, and furthers Murderbot’s integration into the casual bot-human community that is ART’s crew. It also shows that Murderbot’s willingness to trust and even form tentative friendships with other AIs and systems, like AdaCol2, has expanded. The way it extends the governor module hack to the opposing SecUnits is informed a lot more strongly by Murderbot 2.0’s interactions with Three than its own previous clumsy attempts to reach out to the CSU in Exit Strategy, or abrupt dumping of the hack on the ComfortUnit in Artificial Condition. All of these plotlines emphasize Murderbot maturing into not just being a person among humans, but a person recognizing its place and obligations within society that includes both people like and unlike it.

The models of the many ways to be a robot person, and significant relationships and interactions with other robot persons, were and are crucial to Murderbot’s development, sense of self, articulation of its desires, and sense of belonging in the world. Murderbot isn’t alone, and it’s not the only person like itself that it knows. When offered a place in society, it is not the only person like itself in that society. Meeting other AIs, forming relationships with them, was crucial in helping it articulate what it wants in its life. Its human friends are incredibly important to it! That doesn’t stop being true. But so are its AI friends, and the other AIs it passed through the lives of.

This feels like one of the most honest and affirming depictions of what it’s like to feel “other”—that being around only majority people unlike-you, even the ones you like, even your friends, even the ones who mean the best for you and ask you what you need and do everything they can to provide it, can still be exhausting and alienating. Meeting other people like you—even if they’re like you in unlike ways, and have different ways of moving through the world—shows you the many ways to relate to the rest of the world, to be in the world. The many ways to relate to other people and to yourself. The Murderbot Diaries opens up a world where that can be true of bot/construct/AI characters, when so often in sci-fi, their loneliness and alienation is where the metaphor stops.

- - -

*Lt. Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation is probably the most famous example; the only positronic android like himself in existence, barring his evil twin who mostly just needs to be stopped. Others coming to mind include Becky Chambers's A Closed and Common Orbit, in which the AI character is trying to understand who she is in the context of being surrounded by humans; Alien, the secret android crewmate among humans is a threat, and in the sequel Aliens, the android crewmate is earnestly trying to prove he's not; Space Sweepers has a ragtag crew of several humans and a robot; most of the stories in Isaac Asimov's I, Robot are about a singular robot in a human facility. The setup "Human crew with their ship AI" is fairly common in sci-fi, from 2001: A Space Odyssey with its tragically antagonistic HAL9000 operating on a logic that would never occur to humans, to Wolf 359 and The Long Way to a Small Angry Planet where the ship AIs are struggling to determine and articulate how they want to relate to their human friends. Even in Ancillary Justice, Breq is alone and having to pass undercover as human cut adrift from her previous life as a ship's AI. (I know this changes later but I have not actually read the rest of the trilogy)

**as of System Collapse

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Threats to Murderbot’s Sense of Safety, Sense of Self, and Sense of Belonging

or: How the People We Meet Change Us, And Why That’s Not a Bad Thing

An analysis of Murderbot’s emotional foils and its character arc across the first three novellas of The Murderbot Diaries. (This is part 1.)

Written for @murdermetamay and also available to read on AO3

---

In the chapters leading up to the DeltFall Debacle in chapter five of All Systems Red, Murderbot emphasizes several times how it has to act like a good little SecUnit or else it’ll be found out as ungoverned and scrapped for parts. It has spent 35,000 hours constantly refining how it operates, keeping close watch on its actions and the consequences of its actions, and being hypervigilant—all in the name of surviving for another day of watching Sanctuary Moon instead of committing mass murder.

Whether or not it has been entirely successful at remaining undetected throughout those 35,000 hours is unknown to us as the audience. If there have been times where it realized it was almost caught, it doesn’t mention them, and if there were times when someone else noticed it was rogue, it didn’t know about them. So, to us, it’s been doing a pretty good job of hiding—but that certainty unravels very quickly as things start to go wrong for the PresAux survey team.

First, in that opening scene with the fauna in the crater, Murderbot takes it upon itself to ensure Volescu also gets out safely, despite MedSystem’s lack of useful instructions (aside from giving him a tranq). In doing so, Murderbot reveals its actual appearance to the whole team for the first time. Rather than the impersonal opaqued helmet they’ve all gotten used to, now they see its human face. This in itself is not anomalous. After all, calming victims, which it apparently sometimes has to do, is much easier when there’s a human face for the victim to look at rather than a soulless robot that doesn’t know what an emotion feels like.

Given the corporate attitudes we see throughout the series, it’s reasonable to assume that If this were a corporate team or contract, the revelation that the SecUnit has a face might have been momentarily uncomfortable for them, but would ultimately have been glossed over/forgotten about so they could go back to pretending it’s just another part of the habitat. In fact, Murderbot says as much, and even expresses it out loud to Mensah while they’re hiding in the jungle from GrayCris: “It’s usually better if humans think of me as a robot.”

While in the hopper, holding Bharadwaj, Murderbot says it tries to be “as much like an appliance as possible, [...] keeping my head down so I couldn’t see them staring at me.”

The first time it does something it’s not supposed to in front of these humans is when it yells “No!” at Ratthi shortly after getting in the hopper, but it doesn’t dwell on that too much because it was covered up by the humans also yelling at the same time.

Thus we begin to see the first cracks in Murderbot’s self-protective facade. But we also see how much it does seem to like these humans. It understands their interpersonal relationships, who’s friends with whom, who has a crush on whom, and that Dr. Gurathin is a loner but that the others seem to like him.

Next, Murderbot begins to dig itself an even deeper hole by verbally answering when Mensah comes to check on it in its cubicle. It chastises itself for doing so rather than not answering and pretending to be in stasis, but it notes that this is due to its awkwardness rather than its paranoia about being discovered as a hacked unit.

The next day, when Mensah invites it to stay in the crew area with them, it notes that it is out of practice controlling its facial expression because of the usual opaque faceplate and is probably making an expression “somewhere in the region of stunned horror, or maybe appalled horror.”

When Murderbot removes itself to the security ready room, it says: “Now they knew their murderbot didn’t want to be around them any more than they wanted to be around it. I’d given a tiny piece of myself away. That can’t happen. I have too much to hide, and letting one piece go means the rest isn’t as protected.”

In other words, now they know their murderbot isn’t just an emotionless robot, and actually has thoughts and feelings. Their belief otherwise has been a huge part of Murderbot’s cover up to this point, and now that part of its cover is gone.

Despite that, Murderbot continues to be helpful. That’s its job, and it likes these clients. Enough that it gives its real opinions on things when asked, enough that it is proactive in making sure it’s able to go with them as they investigate the map weirdness, and proactive in reporting anomalies like the autopilot cutting out.

But Murderbot’s sense of safety as a SecUnit—especially one without a functional governor module—is directly linked to how well it performs its job. The better it performs, the less likely it is to be investigated, and the less likely it is that the humans will discover that it even has a sense of privacy that can be violated in the first place.

Enter chapter five. Murderbot makes it back alive from the DeltFall habitat. Its humans have saved it from the combat override module. And then Dr. Gurathin tells everyone that Murderbot has a hacked governor module, that it is rogue.

That sense of relative security it had about its continued existence shatters in an instant. But, wait. Its humans, aside from Gurathin, don’t seem to see this as a big deal. Murderbot even lets itself have an emotion—a sense of betrayal—about Volescu’s apparent agreement with Gurathin, before changing its mind when he proved it wrong immediately after by defending it.

It has so far not expressed any emotions about Gurathin one way or another in this scene. It’s reporting the situation, play by play, although it does say it likes Overse because she also steps up to defend it.

Up to this point, Gurathin has been cautious. Speculative, yes, but he only knows so much, and despite his goals being misaligned with Murderbot’s at the moment, it doesn’t actively hold that against him—at least not in its logs—because it also understands the necessity of caution.

Until Mensah asks Murderbot if it has a name, and it says, “No.”

Because that’s when Gurathin says, “It calls itself ‘Murderbot.’”

And Murderbot finally stands up for itself directly. It grates out, “That was private.”

Murderbot’s relationship to its name could be a whole other essay, but it has demonstrated over and over again in the narrative that it does not want to be associated with murdering, and it especially does not want its humans to associate it with murdering. And now these clients, most of whom it likes, know what it calls itself. And they know it’s rogue. And it is terrified of what that will mean for its personal safety in the aftermath of this revelation, but mostly, it’s concerned because... how can they trust it now?

Of course Murderbot doesn’t like Gurathin. In this moment, it might even hate him: He violated its privacy, threatened its autonomy, and threatened its existence as a sentient being all within a very short amount of time. He attempted to break what little trust PresAux might’ve had in it. It has every right to hate him.

Additionally, if a “good” human can do that, how much worse will it be once it’s been turned over to the company?

It says a lot about who Murderbot is as a person that it chooses not to harm Gurathin even though it could. It cares what the others think of it, and of Gurathin, but even without that excuse it wouldn’t harm him. Otherwise, why hack its governor module? Why go through all that trouble to continue existing as a rogue unit in the first place? Who would it even be, if it had hurt him to save itself?

It doesn’t know, and it doesn’t ask. First it needs to get these clients out alive, and then it can deal with all the existential consequences that follow. To get them out alive, they need to trust it, at least a little. It’s a lovely detail that one of the first steps it takes toward reasserting that trust is proving that it has, in fact, been watching Sanctuary Moon this whole time.

So they let it help them, and it does get them out alive. These strange but nice humans buy its contract, buy it. Gurathin may have threatened its autonomy, but it saved his life along with the rest of PresAux, and they repaid it in kind by taking it to safety. Or trying to take it to safety.

Because Murderbot doesn’t want the safety they offer, not yet. It doesn’t know what it wants, but it knows it doesn’t want to be told what it wants. Before it decides, it first has to figure out what to do about those existential consequences.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musings on "(Faked/Temporary/Apparent) Death of A Significant Other" in Fiction

[Mentions contents from Network Effect (The Murderbot Diaries), Sherlock Holmes, BBC Sherlock, and House, M.D. (Season 8), Good Omens. So, potential spoiler]

Losing someone you love is probably the most traumatising experience that can change you forever. In "Life Change Index" by Holmes and Rahe which gives a score (max=100) that indicates how much stress a mojor/minor change in life causes. Since even potentially good change, like starting a new jow, can cause some stress, it includes both positive and negative life changes. But "Death of a Close Friend (37)", "Death of Close Family Member (63)" have high levels of stress, with "Death of Spouse" comes to the top with 100 points.

It is also stressful to experience loss vicariously through books, dramas, and films. Even when they are fictional. When it comes to a temporary loss, however, it is a different matter altogether, I think. I may go as far as to say we actively love it. Pain of loss, anguish, followed by joy of reuniting with the loved one - which we probably do not get to experience (even vicariously) in real life.

The most classic example of "turned out to be actually alive!" is, Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle. Holmes leaves a farewell letter to Watson, with forensic? traces indicating he fell into the Reichenbach Falls with Moriarty. Watson being a Victorian gent, he does not describe how he fell to pieces. But when Holmes dramatically re-emerges 3 years later, Watson promptly faints. Then

Watson is delighted! He does not seem to mind that Holmes had led him to believe that Holmes was dead for 3 years, without a single note to say otherwise.

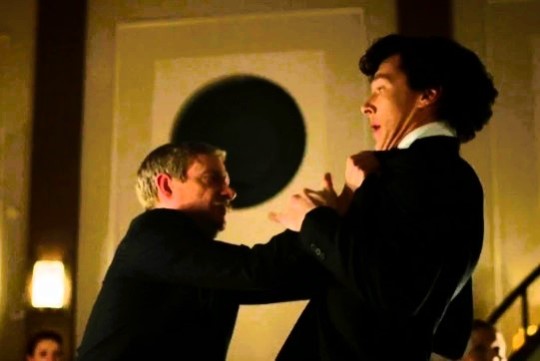

In BBC Sherlock, John Watson living in the 21st century was not so stoic in his response. At Sherlock's "death", John first fell to pieces, requiring him to go to see a therapist where he admits that Sherlock was his best friend. When Sherlock reappears with awkward cheerfulness, John punches him in the face after recovering from the initial shock. And stays very angry for a while, feeling betrayed by having been left to grieve for so long (2 years).

In House M.D., which is basically a medical drama version of Sherlock Holmes, with his best friend James Wilson, House also fakes his death. At his funeral, everybody tries to say something nice about House, but Wilson, angry with grief, calls him arrogant, accuses him for never caring for his friends. Then, gets a text message from House, "SHUT UP YOU IDIOT". House had to go to jail over petty crime for 6 months, when Wilson had only 5 months to live due to cancer. House sacrificed the rest of his career to spend the rest of Wilson's life together.

In Good Omens (Netflix version), when Aziraphale got inconveniently disincorporated, Crowley falls to pieces. Giving up on the idea of running away from Armageddon, he tries to drown his sorrow with drinks. When Aziraphale manages to find him there, Crowley immediately notices and gets delighted, even though Aziraphale was still without body and invisible.

~~~~~

The point I think I am getting to here is that "apparent death of a character, followed by a sort of resurrection" seems to be done in fictional creations when the said temporarily-deceased-one has a significant other that would take us (reader/audience) through anguish, followed by almost painful joy.

Thus, it makes sense to me that in Network Effect, it is Perihelion (aka ART) that would make the protagonist Murderbot go through grief by its apparent death. (Well, it was a death, for a while.) Obviously, MB would be devastated if it lost any of its humans. It cares for the PreservationAux colleagues deeply. But in addition to the fact that it would be a lot harder to resurrect a human (augumented or not) in a story later, it had to be ART, because as the author herself said in her interview, it is probably 'the love of Murderbot's life'.

It is noteworthy to say that MB itself did not give name to its emotional experience, because it probably did not know except that it was a very strong, very negative emotions. Its instant hatred towards those who killed ART and subsequent crippling grief become apparent to the readers through what Amena notices. Its pain is strong and raw, so much that even when MB is simply saying, Ugh, emotions, we feel its grief. And when finally we get to the part with:

All the lights in the control area went dark, then blinked back to life. Simultaneously all the display surfaces around me flickered, went to blank, then flashed reinitialization graphics.

And ART's feed filled the ship. In the pleasant neutral voice that systems use to address humans, it whispered, Reload in progress. Please stand by.

[ ..... ]

Then ART's voice, ART's real voice, filled the feed. It said, Drop the weapon.

Relief and joy we experience is almost heart-skippingly painful. Even though MB's response is more BBC Sherlock's John than the original John Watson, we know how much it must mean to MB. I re-listened/re-read that part at least 10 times.

It is also worth noting that ART also seems to love "pain of loss followed by joy of reunion/resurrection". In Artificial Condition, when a major character died in Worldhoppers, MB had to pause seven minutes while ART sat there in the feed doing the bot equivalent of staring at a wall, pretending that it had to run diagnostics. Then when the character came back to life 4 episodes later, ART was so relieved that they had to watch that episode 3 times before going on!

After long ramblings, my conclusion is, temporaly death of a significant character in fiction is good. More significant the character to the character we can emphasize with, the more painful the loss, and more delightful the reunion. John Watson is the love of Sherlock Holmes's life. Aziraphale is Crowley's. ART is Murderbot's.

#tmbd#murderbot#perihelion#bbc sherlock#sherlock holmes#good omens#faked death#house md#murdermetamay#the murderbot diaries#murderhelion

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was going to post this meta fully on tumblr and then it just wouldn't let me. So I put it on AO3 and tumblr gets a link.

What are resupply leads? What does Murderbot recharge when it takes a recharge cycle? How do construct cells work? Allow me to speculate.

#murderbot#the murderbot diaries#tmbd#meta#murdermetamay#secunit biology#construct biology#speculative biology

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to #MurderMetaMay!

This is a event for creating, sharing, and enjoying meta for The Murderbot Diaries. Our AO3 collection is accepting submissions from now through June 8.

We have weekly "themes" and bunch of meta prompts in the AO3 collection to get you started on making meta! But feel free create works that don't fit into specific prompts. Follow your meta-analysis heart.

Week 1 (May 1 - May 10): Inside: close readings & character analysis

Week 2 (May 11 - May 17): Outside: connections to other media, social issues, etc.

Week 3 (May 18 - May 24): Outside-In: expanding the setting via speculative additions

Week 4 (May 25 - May 31): Inside-Out: personal reflections of how the books have shaped how you feel, think, and live

If you post your works to tumblr, remember to use the tag #MurderMetaMay

For more detail about the event, and prompts to get your meta-thoughts flowing, check out our AO3 collection!

(This blog's header image is from the free-to-read pre-series short story by Martha Wells, "The Future of Work: Compulsory," hosted on WIRED and illustrated by Tracy J. Lee.)

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murderbot Diaries and Terminator: Dark Fate: What Does a Killer Robot WANT, Anyway?

The Terminator (1984) is probably the most famous killer robot in media, setting the image for a what a killer robot is. It’s shaped like a bodybuilder, weapons built into its metal skeleton, eyes hidden behind cool and impersonal sunglasses, a threateningly “foreign” accent, and no feelings, no remorse, and no desires besides killing its target. Kyle Reese describes it to Sarah Connor bluntly: “That Terminator is out there! It can't be bargained with. It can't be reasoned with. It doesn't feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop... ever, until you are dead!” And the film supports this wholeheartedly. We get a few scenes from the Terminator’s perspective, and they do not really indicate that it has much in the way of personality or free will. It’s scary because it is a ruthlessly efficient, tireless, and analytical machine built to kill. It will not stop until its target is dead, or it is.

Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991) gives us a nice Terminator, a Terminator captured from its controlling Skynet and re-programmed to help Sarah and John Connor rather than hunt them. This Terminator gives slightly more suggestions that it has a personality of its own, but ultimately it is still now ruthlessly efficient, tireless, and analytical in protecting its charges, but it still dies at the end in the course of fulfilling its objective. It was, after all, programmed by the human rebels to protect John Connor, and it did.

Did the Terminator want any of that? The second film halfheartedly cares a little, and the first film certainly did not at all. It’s an irrelevant question. It’s a robot; it’s incapable of truly wanting anything, it just does as it’s programmed. It fulfills its objective.

In modern sci-fi, that’s not really a satisfying answer anymore. It looks like a human, has human organic parts built into it, and it clearly has the ability to process large amounts of information and make complex and reasoned decisions. Why do we write it off so thoroughly? Does a Terminator like what it does? Would it choose this? What does a Terminator want?

The Murderbot Diaries (2017-present) by Martha Wells isn’t a direct answer to this question, but it sure is considering it.

The titular Murderbot is very similar to the Terminator: a human-form cyborg, a robot with human organic parts built in, a machine with guns in its arms made to do a job and that job being to protect and/or oppress humans. But as a thinking, feeling, complex entity, it has opinions about that job.

You know what else is a clear response to early Terminator movies’ fundamental uninterest in the Terminator’s inner life and personal opinions on things? Later Terminator movies. Specifically Terminator: Dark Fate (2019).

The fact that The Murderbot Diaries and Dark Fate came out at roughly the same time, in the same sci-fi AI-story zeitgeist, looking back critically at the 80’s and early 90’s Terminator and asking, well, what would it do if it didn’t have to murder, who would it be if it had the choice, is telling.

The Murderbot Diaries stars Murderbot, a SecurityUnit owned by a callously greedy and corner-cutting company that uses such SecUnits ostensibly to protect but in reality to intimidate, control, and surveil human clients. It calls itself “Murderbot” and all SecUnits as a whole “murderbots” for a reason. The world of the books sees SecUnits as mindless killer robots kept in check by their programming, in a very similar way that the Terminator was presented in 1984. We see the story from Murderbot’s point of view: it’s snarky, depressed, anxious, bitter, funny, and very opinionated. It also really, really hates intimidating, controlling, and surveilling people, and it specifically broke its own programming meant to keep it compliant so it wouldn’t have to hurt people. Instead, it wants to half-ass its job and watch soap operas… but it’s sympathetic to humans in danger despite itself, and when it chooses humans it cares about, it will go to great lengths (ruthless, but very tired and full of fear and pity) to protect them. What does it want? To be given space; to not be given orders; to have the ability to take its time and watch its shows and determine what its job as Security means to it.

Terminator: Dark Fate takes a different tack. (It’s actually about three badass women and I’m very sorry for focusing on the man-like character here BUT) Dark Fate presents an alternate timeline off the main series, where the Terminator succeeded in killing young John Connor. Previously, we had seen Terminators that would not stop until they were dead; this one fulfills Reese’s other warning. It will not stop until John Connor is dead. Well…. it succeeded. John Connor is dead.

Now what?

In the opening scene, we see this from his mother Sarah Connor’s perspective. The Terminator appears out of time, ambushes and kills young John Connor, and then stands there looking impassively at the destruction it wrought while Sarah screams.

It looks cold and satisfied when that scene is first presented. But when we see it again from the Terminator’s perspective, it seems to just stand there, staring stupidly, suddenly with no direction in life. It fulfilled its objective. It followed its programming. Now it has no more objective, can receive no more orders, and its programming has nothing more to tell it to do. It eventually disappears into the woods, learns more about humanity, grows a conscience, lives in a little cabin with a woman and her son fleeing an abusive husband in an apparently mutually very supportive relationship, chops wood, drives a truck, and gives Sarah Connor insider information to allow her to track down other incoming Terminators as a way of atonement. It does have remorse, if given time to think for itself and realize it. It doesn’t really want to hurt people, and even, similar to Murderbot, has a drive to use its strength and intimidating-ness to protect the people it chooses. It mostly wants to be quietly and safely left alone.

Both the Terminator and Murderbot are killer robots left adrift, aimless, reeling, suddenly having to decide for themselves what to do with their lives for the first time. Both are stories that circle back to the original Terminator premise and say, okay, but that killer robot isn’t killing for the sheer thrill of it, it was forced into doing that by a top-down authority in control of its programming. That would kind of fuck someone up, actually. It’s a hopeful narrative: these things are people, and they don’t want to be hurting other people. When given the option, they just want to rest, make amends, understand the truth, find a place they belong, and see the people they care about safe. And I think it’s fascinating that not only is smaller, literary sci-fi asking this question and telling this story, but so is the Terminator franchise itself.

We also just as blatantly see the evolution of Sarah Connor as a character. In The Terminator (1984) the Terminator is sent to kill Sarah Connor. When I was watching it recently with some friends who had never seen it before, they guessed—almost correctly—“oh, it’s because she’s the rebel leader in the future!” Sorry guys, this is a 1980s mainstream sci-fi blockbuster. Her as-yet unborn son is going to be the rebel leader. That’s why the robots in the future need to kill her, before she gives birth to the hero of the humans. Blech, I know.

Over the course of the movie, though, she becomes tough, fierce, and brave, the type who can and will survive the apocalypse; in future movies and tv series (like The Sarah Connor Chronicles, 2008, where she gets to be the eponymous title character this time!), she gets to be a strong leader in her own right. This is particularly true in Terminator: Dark Fate, where Sarah Connor is a tough, grizzled, middle-aged Terminator-fighter, who steals heavy weaponry from the government to track down and kill Terminators arriving from the future. She becomes a mentor to the new woman being hunted down by the new Terminator threat, Dani Ramos. This time, though, Dani isn’t fated to be the mother of the human rebel leader—she is destined to become the human rebel leader herself. Along with Dani’s own Kyle Reese figure, a cybernetically-augmented human fighter from the future named Grace, women get central action-hero and rebel-leader roles in Terminator: Dark Fate, feeling like an awkward apology for the sexism inherent in the premise of 1984’s The Terminator. (However, Dark Fate stops short of committing to the Dani-Sarah/Grace-Reese parallel and letting them be lesbians. It’s still a mainstream action movie, I guess.) We even see the development of a curt but resentfully respectful understanding between Sarah Connor and the Terminator that killed her son.

I lay this out because in the same way I see the literary DNA of the Terminator in Murderbot, I see elements of Sarah Connor in Dr. Mensah. She’s the human protagonist—the one who would be the protagonist if All Systems Red had been from the human perspective—and feels like the answer to a similar question to “what does a killer robot want?”, namely, “what if, instead of enemies locked into battle to the death, the badass human and the killer robot worked together and came to an understanding? What if they could be friends instead of enemies?” Mensah also feels like a feminist response to some of the issues I had with Sarah Connor—that she didn’t get to be the leader herself, that despite her own strength and tenacity being the mother to the leader was the most important thing she would do—and responds to them in a similar way that Dark Fate somewhat apologetically does. Mensah is the leader of her society (her planet). Mensah is a mother and she is a scientist and a leader and gets her badass action-hero moments (MINING DRILL). She is the first to reach out to Murderbot. To ask it how it feels, and calm down the others later when they’re afraid; her relationship with Murderbot is unique. She’s a foil to Murderbot in a parallel but opposite way that Sarah Connor is a foil to the Terminator. And while in Dark Fate they are not friends (the Terminator did still kill Sarah’s son, even if it didn’t specifically want to) we see the same kind of desire reflected: what if they were at least allies? What if they were working together? How would that relationship go? What kind of understanding could they come to, about what it means to be human and to be machine? It's a smaller part of the movie and they don't give a whole lot of answers, but it's there.

Both All Systems Red (and the subsequent Murderbot Diaries books) and Terminator: Dark Fate were released in a very different sci-fi zeitgeist than The Terminator was. They’re both looking back, and reacting to it: Dark Fate directly, The Murderbot Diaries indirectly. And they’re approaching the concept of the Terminator and its Sarah Connor figure with similar questions: What does the robot want, aside from its programming to kill, and if it could be freed of its programming to kill, what kind of relationships—with society, with the concept of self-determination, and with its human woman foil—could it potentially be able to develop, with that freedom?

#They’re also both aroace#is it regressive? Does it imply things about sex/romance and humanity?#I don’t care I appreciate that neither one had to prove itself a whole person by falling in love#that’s a topic for a different post#Dani and Grace didn’t get a romance either. Cowards#but I kind of appreciate there was no human romance and sex/inhuman lack of romance and sex that was sorta lowkey going on in the original#This piece is less polished than last week's but oh well#MurderMetaMay#The Terminator#Terminator Dark Fate#The Murderbot Diaries#meta#my meta

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

And May is now over!

Our AO3 collection is still open and accepting submissions until June 8th, if you still want to sneak one in there.

Thank you everyone who shared some meta thoughts. We hope you’ve had some fun this month reading and sharing Murderbot meta! 📚

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

MurderMetaMay Challenge

Try your hand at just 15 minutes of meta! Draft, doodle, or discuss with a friend.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 4: "Inside Out"

(personal reflections of how the books have shaped how you feel, think, and live)

Week 4 of MurderMetaMay closes out the month of May, running until Friday, May 31!

A lot of us connect deeply to Murderbot. The books took off in popularity for a reason. Week 4 invites you to reflect on your relationship with the books, what they mean to you, if they introduced you to concepts or influenced the way you think about the world or yourself.

This is pretty open-ended - what has Murderbot meant to you?

You can check out more prompts on our AO3 collection prompt list. But as always, if you have a fun idea for a meta that doesn't fit into the given prompts, go for it!

And if you've written anything on tumblr, now is a great time to archive it to the AO3 collection as well!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Meta] Name Dropping, by ArtemisTheHuntress and FlipSpring

2,695 words

#No Archive Warnings Apply, #Meta, #Analysis, #Character Analysis, #Names, #Spoilers for Book 7: System Collapse, #Spoilers for the whole series through System Collapse, #MurderMetaMay 2024

Murderbot tends to call bots by descriptive identifiers, rather than human-facing names.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 3: "Outside In"

(expanding the setting via speculative additions from our world)

Week 3 of MurderMetaMay runs from May 18 - May 24!

The world of The Murderbot Diaries is expansive, but also sparsely drawn - we see it through the eyes of Murderbot, who only comments on what's relevant to it. Week 3 invites you to speculate about the world of TMBD, and how it works. Biology, linguistics, alien remnants, religion, economy, politics laws, education - how might these work in the Corporation Rim, on Preservation, or elsewhere?

Wells works in broad strokes, leaning heavily on the sci-fi canon to build out her world. (Giant ground worms, anyone?) If you love to get into the minutiae and speculate on how, space transit works in the Murderbot universe, this is your week!

Some prompts:

SecUnit biology! How does Murderbot stay hydrated? How does it get its nutrients? How do the organic parts interface with the inorganic ones? How does the governor module work?

Aliens! Is the giant worm from ASR an alien? What does that suggest about the difference in categories/classification between giant fauna and alien remnants? What does legitimate alien remnant study look like? What's the difference between strange synthetics and alien remnants?

Linguistics and languages! What languages are spoken across the galaxy? How do translation/language modules work - for SecUnits, for augmented humans, for unaugmented humans?

The Feed! What is it, exactly, and how does it work?

Wormholes! What are they, exactly, and how do they work? How does interstellar travel happen, and what does that imply for galactic connectivity?

Bot guardianship! Preservation isn't the only planet that has it - how does it work on Preservation, and elsewhere?

We'd love to see what you come up with!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 1: "Inside"

(close readings, character analysis, lists of named things, people, & places, etc)

Week 1 of MurderMetaMay runs from May 1 - May 10!

The Murderbot Diaries is a well-constructed piece of art with deliberate characterization, worldbuilding details, and themes; Martha Wells is also fully upfront about being a "pantser" who writes what inspiration strikes her and sometimes changes her mind about things. Week 1 encourages you to write meta and analysis about the Murderbot Diaries as self-contained works.

Some prompts:

A close reading of your favorite scene

An analysis of how a certain character or theme develops over the course of the books

Murderbot's relationships with other bots, constructs, and systems vs. humans

Drawing maps of described places

Your thoughts on Kevin Free's portrayal and readings of certain scenes and moments, or comparisons between the different audio adaptations

The role of media in Murderbot's life

You can check out more prompts on our AO3 collection prompt list. But if you have a fun idea for a meta that doesn't fit into the given prompts, go for it!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week 1: "Inside" is almost over

Tomorrow marks the end of the first week of MurderMetaMay! Now is your chance if you want to squeeze out a quick paragraph about: close readings, character analysis, lists of named things, people, & places, etc

You can still post your meta to the AO3 collection for the rest of this month of course. But you know how the great wheel of Time is: tireless and indomitable.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Meta] Inhuman/Unperson: The Social Construct by FlipSpring

words: 2,100

#No Archive Warnings Apply #Meta #Speculative #Analysis #MurderMetaMay 2024 (Murderbot Diaries)

What exactly is the difference between a bot-human construct and an augmented human?

2 notes

·

View notes