#my music tastes are varied and not highbrow

Note

I’ve heard mixed things about ghost in the cell stand alone complex. I understand that it’s not as iconic as the movie, but is it still good?

GitS:SAC (both seasons, they're very similar) is definitely the second best thing to ever come out of GitS, and yeah, it's quite good. I'd even go as far as to say that it's the "real" GitS, because the original movie is mostly Oshii doing his thing. SAC strikes the balance between the schlocky manga (no, having a lot of text does not make anything not schlock and I WILL die on this hill) and the fairly highbrow movie - call it tasteful pulp, if you will. Production values are high, the music is fantastic (Yoko Kanno's best work in my opinion), and the writing varies between solid and excellent. The movie is in an entirely different league (that being the best movies of all time, period), but SAC is still the gold standard for an anime cyberpunk TV show.

As for the rest: We don't talk about Innocence, and we don't talk about Arise either. We do talk (shit) about 2045. Solid State Society is more or less a retelling of the movie with the SAC attitude - it's not bad, but I'd call it inessential when you could just watch '95 instead.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Playlisting!

I was tagged by @la-paritalienne and @harryincamp <3 thanks babes!!!

Rules: we’re snooping your playlist. Put your entire music library on shuffle and list the first ten songs, then choose ten victims

GUESS WHAT i am gonna talk about the songs bc I like doing that!

1) Meant to Be (Bebe Rexha ft. Florida Georgia Line)

I wish there was a version of this that was all Bebe. Her part is fucking gorge. Also when she sings about guys breaking her heart I wanna hold her.

2) Fair (Ben Folds Five)

Listen I have always had a great idea for a video for this song (it’s essentially a super slow-mo acting out of the song interspersed with a high speed replay of the relationship of the couple)

3) You and Me of the 10,000 Wars (Indigo Girls)

CLASSIC EMILY!!! So lyrically rich and full of metaphors and lovely imagery. You hardly ever hear this one live, which is sad. “I wanted everything to feed me, about as full as I got was of myself and the upper echelons of mediocrity,” girl WHAT? dang.

4) A Woman’s Love (Alix Dobkin/Lavender Jane Loves Women)

warning that alix d. is a terf, bleh. But this song is vintage lez, damn. Big first time loving a woman, I just realized I’m a dyke and nothing has ever felt better mood.

5) Nothing to Prove (Jill Sobule)

I LOVE JILL!!! She’s clever and funny and she writes a good song. My fave here is her joke about moving to LA and having people say they’re in the industry-- “I ask, ‘oh are you in steel?’” If that’s not big east coaster moving west energy, damn.

6) Filthy/Gorgeous (Scissor Sisters)

This will forever remind me of my housemate, B-Monster. It was 2007-2008 (maybe a bit longer) and they loved scissor sisters and dancing like a wildling.

7) I Like Fucking (Bikini Kill)

CATHARSIS!!!! What we need is action strategy, I want I want I want I want I WANT IT NOW <3 <3 <3

8) Laramie (Amy Ray)

Ummm rude to throw this gay depression tune in, eh? But it’s good and important, a reflection on Matthew Shepherd’s murder from a southern gay who’s traveled all over. “Tolerance, it ain’t acceptance. I know you wanted it to be.” So much better live than the recorded version bc you could feel the intensity and rage behind the pain.

9) The Book of Love (Magnetic Fields)

You ought to give me wedding rings.

10) Early in the Morning (Buddy Holly)

Do you ever sit around and wonder what music Buddy Holly would’ve made if he hadn’t died in that plane crash? What he would’ve sounded like in the 70s or 80s or later on? I sure enough do.

well that was a journey, wasn’t it?

idk who to tag! if you don’t wanna do this no worries, and if you do but weren’t tagged please do it!!

@42mins @uhohmorshedios @greeneyedlarrie @cupcakentea @statementlou @lesbianchrispine @alienfuckeronmain @hogwartzlou @jlf23tumble @greeneyedbelle

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

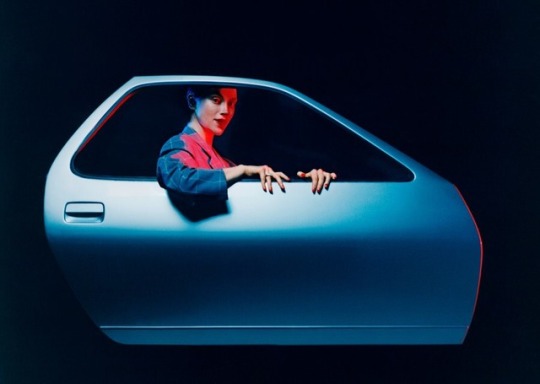

Switching Lanes With St. Vincent

By Molly Young

January 22, 2019

Jacket (men’s), $4,900, pants (men’s), $2,300, by Dior / Men shoes, by Christian Louboutin / Rings (throughout) by Cartier

On a cold recent night in Brooklyn, St. Vincent appeared onstage in a Saint Laurent smoking jacket to much clapping and hooting, gave the crowd a deadpan look, and said, “Without being reductive, I'd like to say that we haven't actually done anything yet.” Pause. “So let's do something.”

She launched into a cover of Lou Reed's “Perfect Day”: an arty torch-song version that made you really wonder whom she was thinking about when she sang it. This was the elusive chanteuse version of St. Vincent, at least 80 percent leg, with slicked-back hair and pale, pale skin. She belted, sipped from a tumbler of tequila (“Oh, Christ on a cracker, that's strong”), executed little feints and pounces, flung the mic cord away from herself like a filthy sock, and spat on the stage a bunch of times. Nine parts Judy Garland, one part GG Allin.

If the Garland-Allin combination suggests that St. Vincent is an acquired taste, she's one that has been acquired by a wide range of fans. The crowd in Brooklyn included young women with Haircuts in pastel fur and guys with beards of widely varying intentionality. There was a woman of at least 90 years and a Hasidic guy in a tall hat, which was too bad for whoever sat behind him. There were models, full nuclear families, and even a solitary frat bro. St. Vincent brings people together.

If you chart the career of Annie Clark, which is St. Vincent's civilian name, you will see what start-up founders and venture capitalists call “hockey-stick growth.” That is, a line that moves steadily in a northeast direction until it hits an “inflection point” and shoots steeply upward. It's called hockey-stick growth because…it looks like a hockey stick.

Dress, by Balmain

The toe of the stick starts with Marry Me, Clark's debut solo album, which came out a decade ago and established a few things that would become essential St. Vincent traits: her ability to play a zillion instruments (she's credited on the album with everything from dulcimer to vibraphone), her highbrow streak (Shakespeare citations), her goofy streak (“Marry me!” is an Arrested Development bit), and her oceanic library of musical references (Kate Bush, Steve Reich, uh…D'Angelo!). The blade of the stick is her next four albums, one of them a collaboration with David Byrne, all of them confirming her presence as an enigma of indie pop and a guitar genius. The stick of the stick took a non-musical detour in 2016, when Clark was photographed canoodling with (now ex-) girlfriend Cara Delevingne at Taylor Swift's mansion, followed a few months later by pictures of Clark holding hands with Kristen Stewart. That brought her to the realm of mainstream paparazzi-pictures-in-the-Daily-Mail celebrity. Finally, the top of the stick is Masseduction, the 2017 album she co-produced with Jack Antonoff, which revealed St. Vincent to be not only experimental and beguiling but capable of turning out incorrigible bangers.

Masseduction made the case that Clark could be as much a pop star as someone like Sia or Nicki Minaj—a performer whose idiosyncrasies didn't have to be tamped down for mainstream success but could actually be amplified. The artist Bruce Nauman once said he made work that was like “going up the stairs in the dark and either having an extra stair that you didn't expect or not having one that you thought was going to be there.” The idea applies to Masseduction: Into the familiar form of a pop song Clark introduces surprising missteps, unexpected additions and subtractions. The album reached No. 10 on the Billboard 200. The David Bowie comparisons got louder.

This past fall, she released MassEducation (not quite the same title; note the addition of the letter a), which turned a dozen of the tracks into stripped-down piano songs. Although technically off duty after being on tour for nearly all of 2018, Clark has been performing the reduced songs here and there in small venues with her collaborator, the composer and pianist Thomas Bartlett. Whereas the Masseduction tour involved a lot of latex, neon, choreographed sex-robot dance moves, and LED screens, these recent shows have been comparatively austere. When she performed in Brooklyn, the stage was empty, aside from a piano and a side table. There were blue lights, a little piped-in fog for atmosphere, and that was it. It looked like an early-'90s magazine ad for premium liquor: art-directed, yes, but not to the degree that it Pinterested itself.

Coat, (men’s) $8,475, by Versace / Shoes, by Christian Louboutin / Tights, by Wolford

The performance was similarly informal. Midway through one song, Clark forgot the lyrics and halted. “It takes a different energy to be performing [than] to sit in your sweatpants watching Babylon Berlin,” she said. “Wherever I am, I completely forget the past, and I'm like. ‘This is now.’ And sometimes this means forgetting song lyrics. So, if you will…tell me what the second fucking verse is.”

Clark has only a decade in the public eye behind her, but she's accomplished a good amount of shape-shifting. An openness to the full range of human expression, in fact, is kind of a requirement for being a St. Vincent fan. This is a person who has appeared in the front row at Chanel and also a person who played a gig dressed as a toilet, a person profiled in Vogue and on the cover of Guitar World.

The day before her Brooklyn show, I sat with Clark to find out what it's like to be utterly unstructured, time-wise, after a long stretch of knowing a year in advance that she had to be in, like, Denmark on July 4 and couldn't make plans with friends.

“I've been off tour now for three weeks,” she said. “When I say ‘off,’ I mean I didn't have to travel.”

This doesn't mean she hasn't traveled—she went to L.A. to get in the studio with Sleater-Kinney and also hopped down to Texas, where she grew up—just that she hasn't been contractually obligated to travel. What else did she do on her mini-vacation?

“I had the best weekend last weekend. I woke up and did hot Pilates, and then I got a bunch of new modular synths, and I set 'em up, and I spent ten hours with modular synths. Plugging things in. What happens when I do this? I'm unburdened by a full understanding of what's going on, so I'm very willing to experiment.”

Coat, by Boss

Jacket, and coat, by Boss / Necklace, by Cartier

Like a child?

“Exactly. Did you ever get those electronics kits as a kid for like 20 bucks from RadioShack? Where you connect this wire to that one and a light bulb turns on? It's very much like that.”

There's an element of chaos, she said, that makes synth noodling a neat way to stumble on melodies that she might not have consciously assembled. She played with the synths by herself all day. “I don't stop, necessarily,” she said, reflecting on what the idea of “vacation” means to someone for whom “job” and “things I love to do” happen to overlap more or less exactly. “I just get to do other things that are really fun. I'm in control of my time.” She had plans to see a show at the New Museum, read books, play music and see movies alone, always sitting on the aisle so she could make a quick escape if necessary. But she will probably keep working. St. Vincent doesn't have hobbies.

When it manifests in a person, this synergy between life and work is an almost physically perceptible quality, like having brown eyes or one leg or being beautiful. Like beauty, it's a result of luck, and a quality that can invoke total despair in people who aren't themselves allotted it. This isn't to say that Clark's career is a stroke of unearned fortune but that her skills and character and era and influences have collided into a perfect storm of realized talent. And to have talent and realize that talent and then be beloved by thousands for exactly the thing that is most special about you: Is there anything a person could possibly want more? Is this why Annie Clark glows? Or is it because she's super pale? Or was it because there was a sound coming through the window where we sat that sounded thrillingly familiar?

“Is Amy Sedaris running by?” Clark asked, her spine straightening. A man with a boom mic was visible on the sidewalk outside. Another guy in a baseball cap issued instructions to someone beyond the window. Someone said “Action!” and a figure in vampire makeup and a clown wig streaked across the sidewalk. Someone said “Cut!” and Clark zipped over for a look. It was, in fact, Amy Sedaris, her clown wig bobbing in the 44-degree breeze. The mic operator was gagging with laughter. It seemed like a good omen, this sighting, like the New York City version of Groundhog Day: If an Amy Sedaris streaks across your sight line in vampire makeup, spring will arrive early.

Blazer (men’s) $1,125, by Paul Smith

Another thing Clark does when off tour is absorb all the input that she misses when she's locked into performance mode. On a Monday afternoon, she met artist Lisa Yuskavage at an exhibition of her paintings at the David Zwirner gallery in Chelsea. Yuskavage was part of a mini-boom of figurative painting in the '90s, turning out portraits of Penthouse centerfolds and giant-jugged babes with Rembrandt-esque skill. It made sense that Clark wanted to meet her: Both women make art about the inner lives of female figures, both are sorcerers of technique, both are theatrical but introspective, both have incendiary style. The gallery was a white cube, skylit, with paintings around the perimeter. Yuskavage and Clark wandered through at a pace exclusive to walking tours of cultural spaces, which is to say a few steps every 10 to 15 seconds with pauses between for the proper amount of motionless appreciation.

The paintings were small, all about the size of a human head, and featured a lot of nipples, tufted pudenda, tan lines, majestic asses, and protruding tongues. “I like the idea of possessing something by painting it,” Yuskavage said. “That's the way I understand the world. Like a dog licking something.”

Clark looked at the works with the expression people make when they're meditating. She was wearing elfin boots, black pants, and a shirt with a print that I can only describe as “funky”—“funky” being an adjective that looks good on very few people, St. Vincent being one of them—and sipped from a cup of espresso furnished by a gallery minion. After she finished the drink, there was a moment when she looked blankly at the saucer, unsure what to do with it, and then stuck it in the breast pocket of her funky shirt for the rest of the tour.

A painting called Sweetpuss featured a bubble-butted blonde in beaded panties with nipples so upwardly erect they actually resembled little boners. Yuskavage based the underwear on a pair of real underwear that she'd constructed herself from colored balls and string. “I've got the beaded panties if you ever need 'em,” she said to Clark. “They might fit you. They're tiny.”

Earrings, by Erickson Beamon

“I'm picturing you going to the Garment District,” Clark said.

“There was a lot of going to the Garment District.”

As they completed their lap around the white cube, Clark interjected with questions—what year was this? were you considering getting into film? how long did these sittings take? what does “mise-en-scène” mean?—but mainly listened. And she is a good listener: an inquisitive head tilter, an encouraging nodder, a non-fidgeter, a maker of eye contact. She found analogues between painting and music. When Yuskavage mourned the death of lead white paint (due to its poisonous qualities, although, as the artist pointed out, “It's not that big a deal to not get lead poisoning; just don't eat the paint”), Clark compared it to recording's transition from tape to digital.

“Back in the day, if you wanted to hear something really reverberant”—she clapped; it reverberated—“you'd have to be in a room like this and record it, or make a reverb chamber,” Clark said. “Now we have digital plug-ins where you can say, ‘Oh, I want the acoustic resonance of the Sistine Chapel.’ Great. Somebody's gone and sampled that and created an algorithm that sounds like you're in the Sistine Chapel.”

Lately, she said, she's been way more into devices that betray their imperfections. That are slightly out of tune, or capable of messing up, or less forgiving of human intervention. “Air moving through a room,” Clark said. “That's what's interesting to me.”

They kept pacing. The paintings on the wall evolved. Conversation turned to what happens when you grow as an artist and people respond by flipping out.

“I always find it interesting when someone wants you to go back to ‘when you were good,’ ” Yuskavage said. “This is why we liked you.”

“I can't think of anybody where I go, ‘What's great about that artist is their consistency, ” Clark said. “Anything that stays the same for too long dies. It fails to capture people's imagination.”

Coat (mens), $1,150, by Acne Studios

They were identifying a problem with fans, of course, not with themselves. It was an implicit identification, because performers aren't permitted to critique their audiences, and it was definitely the artistic equivalent of a First World problem—an issue that arises only when you're so resplendent with talent that you not only nail something enough to attract adoration but nail it hard enough to get personally bored and move on—but it was still valid. They were talking about the kind of fan who clings to a specific tree when he or she could be roaming through a whole forest. In St. Vincent's case, a forest of prog-rock thickets and jazzy roots and orchestral brambles and mournful-ballad underlayers, all of it sprouting and molting under a prodigious pop canopy. They were talking about the strange phenomenon of people getting mad at you for surprising them. Even if the surprise is great.

Molly Young is a writer living in New York City. She wrote about Donatella Versace in the April 2018 issue of GQ.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2019 issue with the title "Switching Lanes With St. Vincent."

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

phillips as poplit

It was spring, around 11am and cold; we had teas with condensed milk in a small Malaysian place in the Lower East Side and I held up an AbEx painter book that was on sale and you made a joke about the page layout.

For about a week the prior May I’d wondered whether or why there hadn't been a poptimist moment in literature, whether that was even a coherent concept. I’d been convinced by a friend the main reason was popular literature was missing the impassioned obsession with craft and technical production, the “Futurist (as in Italian) machine-worship thing.”

But now I was wondering, somewhere between Ludlow and Allen Street, whether this might be an entirely separate question from whether there was admirable or highbrow pop literature. George Melly who raises the topic of pop literature in the 1970 Revolt Into Style thinks the answer to this second question is also no:

The written word, at any rate ‘between hard covers,’ represents a permanence of a sort. Thought is trapped there... There is a further objection: to write and to read are solitary activities. Pop is communal, tribal, a shared experience.

None of these convinced you when I read them out loud, which made me finally sure they didn’t convince me either. Records are as physical as books, you said; the digital has untethered writing from any distinctive permanence or aura thereof; pop experiences can clearly be solo and yet also somehow communal (think the opening scenes of Almost Famous, the discovery of his older sister’s record collection, its portal into another world).

With the Sticky Fingers cover in my eyes I told you “I have this weird suspicion that writers like Kaitlin Phillips might be innovators of pop literature. All the traits are there (for a masculinized version, think rock’n’roll). An emphasis on style over content, the way and electricity with which you deliver a line, the cult of personality and aspirational quality of fandom, the quasi-total package of high-status youth, the conversion of private life into public life, image and glamour. This seems like one of the most exciting developments in recent writing; we probably needed a pop literature, or at least it was inevitable.” But I told you I also thought we needed to be clear about what pop literature was. Reading Maggie in contrast, what strikes me always is her honesty, her willingness to bear the grotesque or deeply shameful without immediately redeeming her image, without the savvy branding or the sleight of hand that turns flaw into costly signal, or weakness into an display of competitive femininity.

By the time you checked email over kabocha squash & sake I was mostly talking to myself: “The vision’s always felt to me like, ‘let's replace a history of brutal economic hierarchies with a future of brutal social hierarchies,’ which, middle school sucked for a lot of people and might be worse than capitalism but, your mileage may vary.” Maybe I don’t see a serious problem in reveling in bad ideology, maybe the style makes up for it. Maybe it’s the sometimes Janus face of some of these scenes which grates, one face making, with moral indignity, a claim towards the radically anti-hierarchical, while the other indulges gleefully the pleasures of life at the top.

ii.

Of pop music Alva Noë writes, “the artist is not a vehicle for music; instead music is a vehicle for the artist.” Pop music is the “art of pure personal style,” a manipulation of cultural codes to enthrall and to convert. What propaganda is to art, advertisement is to pop, a hypnosis, an attempt at psychic implantation.

The music, or here, the writing, is a conjuring act of personality, an apparition summoned by the right triangulation of tone, the attitude, and taste (these all being orientations towards, the how instead of what— in a word, style). The material world is transformed into iconography: objects are used by people, therefore status is transferred through association. “We can all agree that bath salts are passé,” Phillips opens a college essay of hers, “Eastern Promises,” written for the Spectator. Five years later, her Bookforum review of a Rhonda Lieberman tribute begins in explosive baroque prose:

Not just because I—Barnard shiksa from the boonies—was conditioned to envy my more socially savvy Jewish American counterparts for their sunglasses (from Selima), their scarves (not Hermès, actually) knotted the way their mothers taught them, and other birthright privileges awarded young ladies of a certain socioeconomic-religious-cultural demographic, who I imagine learned about Freud from their fathers (this is just a fantasy!), am I fascinated by Rhonda Lieberman.

These links between people and objects, and their history, constitute a cultural graph on which the pop work has been positioned. The objects gets separated out like God on the first day, splitting darkness from light: in or out, low or high, melted into sacred vs profane. In a poptimist or “post-critical” era, this is one of the few discourses which revels Roxy-like in aristocratic sentiment. Often, relatedly, there is in pop a a deep interest in fame and inner circles, celebrity and its half-sibling fashion— see Warhol, Bowie, Gaga.

From early in Phillips’s writing career, agile code-switching is a cornerstone of the performance. “You might shvitz—uh, sweat—with Dad at a Mikvah” she writes aside references to W.H. Auden, Mick Jagger, and Benjamin Britten in “Eastern Promises.” The article, which sells the virtues of bathhouses to her college classmates, includes as primary selling points the potential for brush-ups with celebrity, the history of Someones who have been sighted through the steam. (Another article from that time is a sprawling amateur-journo investigation of St. A’s, the hyper-elite Columbia fraternity which sports a private chef.) Like a young Joan Didion, there's a self-deprecation in her writing that can only be read as irony in-context: “I came up from [the pool] shrieking... I report only that I made no friends.”

Another piece from 2013, a longform on Tao Lin, was linked to by the LARB, Ron Silliman's blog, and some alt literature sites. She wrote about Lin’s demonstrated savvy at building an online following, speculated on the mechanics at play: “Many critics, and fellow bloggers, ask ‘why?,’ but perhaps the more pertinent line of inquiry is ‘how?’” She had started a Twitter account at n+1, @nplusoneinterns, that took as its shtick the pretense of being a group account. Tao Lin himself ended up asking her to make a similar account for him; she gave out the password to classmates to post whatever they wanted. She wasn’t alone in fielding this kind of request; there was a small army of Lin fans that he led and encouraged in growing his reputation through stickering public spaces and making fan blogs.[1]

Phillips’s iconographic matriarch is always Rhonda Lieberman. “She embodies the particular kind of East Coast sophistication I ideated and craved, a wry dinner-party companion known for asides about her complicated relationships with intellectuals.” In Lieberman's writing, the academic-intellectual is turned into a life texture: “1) daily horoscopes and tarot readings; 2) Friedrich Nietzsche; 3) listening to [others on] Prozac.” Like Lieberman, Phillips smashes the high and the low side-by-side (more code-switching, the cultural-linguistic equivalent of turning on a dime): “Derrida is the Madonna of thought. He’s antiphallogocentric and a total diva.” Or, “Thorstein Veblen’s pecuniary emulation, i.e., the Jewish American Princess who buys a Coach purse at twelve only to learn about Prada a year later.” Abstract --> concrete via the i.e.. Lieberman herself is proto-pop, a total mother. “Reviewing a book by Lieberman weirdly feels like reviewing her,” Phillips confesses.

iii.

The flags are at half mast in Union Square: I’m watching you watch a squirrel, seriously fat, scaling Lincoln’s brass left leg. The trees are black-denuded still, it’s too early in the year. Post-structuralism, psychoanalysis, and Derrida: the dollar used bookstands are stacked with them, some kind of sign. The end of an era or an era’s perpetuation? The last clearings or signs of health? Internal readings (formalist, structuralist, New Critical) vs. external readings (Marxist, biographical, sociological, Bourdieuian). The visiting European intellectuals who come lecture, give panel talks, do their continent disservice so routinely out of touch, or banal, or sentimental in that way middle-aged liberals get.

You had recently started switching from kairos, event-time, to chronos, sequential-numeric. Off of summer’s “after the party,” or “when we wake up,” and onto the worldtime of 9:00 a.m. It was making me grumpy, a feeling counteracted only by the way the teenagers next to us were talking: “perf,” “def,” “I’m totally jeal.”

[1] Is it only fair I trace her provenance this way? From her essay on Lin, “His decision to be a writer seems to have cemented during his senior year, in 2004, when Lin went into self-imposed isolation. He left the dorms and moved to New Jersey.” Later: “His first three years out of college are marked by their tenacious, discursive productivity. In fact, from his output during this period, it is hard to tell he lost hope at all.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Anti-Aesthetic- an essay

In Newton's’ third law of motion, it’s explained that every action has an opposite and equal reaction. Although seemingly an obscure theory to apply to the world of visual arts, this can explain one of the most sort after and developed aesthetics used globally in the industry; the anti-aesthetic. A term coined in 1980 by Hal Foster, the anti-aesthetic describes a movement that flips current aesthetic trends on its head, often with a socio-political agenda. In this, every action the industry deems pleasing and beautiful, has an opposite and equal reaction in the anti-aesthetic movement. From what began as a movement against the art world has grown in a movement against everything from film, music and fashion to advertising, graphics and culture. The idea of joining a collective of people worldwide who preach the anti-aesthetic is often the main reason artists join the visual arts world- to fight against conformity and challenge ideas of so called beautiful things in the industry.

This essay will answer several questions through a series of chapters in the chosen format of an extended essay. Chapter one will be describing how the anti-aesthetic movement began across the visual arts industry by exploring how the leading figures of anti-aesthetic utilise their medium to create chaos and because of this, the criticism they have faced. In this chapter, key artists that are featured are Marcel Duchamp and Allen Jones who helped pioneer Pop Art in the UK; John Waters and Andy Warhol as filmmakers, whose work shocked and upset audiences with a refusal to settle in a beautiful and accepted aesthetic and finally, discussing how the punk movement, with designers such as Jamie Reid, allowed amateurs to break into the graphic design industry and became a big influence to future underground subcultures.

Chapter two will discuss how this has affected the graphic design industry specifically and how outside factors such as protest art, feminist groups and political turmoil have shaped contemporary graphics under the question; How the anti-aesthetic movement has impacted upon the visual arts industry? Within this, following from the first chapter, will explore punk further, discussing how punk helped curate a graphic and visual language for movements against political injustice.

‘How do large companies use the anti-aesthetic in their advertising and how can this be harmful to the political side of the movement’ is the question in the third chapter. By looking at advertising campaigns and brand identities, this essay will discuss whether the anti-aesthetic is used appropriately or whether advertising is saturating and commercialising the anti-aesthetic and stripping it of its’ integrity.

Chapter One- How did the anti-aesthetic movement began across the visual arts industry?

This chapter will cover how the history of the anti-aesthetic movement began and how 20th century art movements became part of it. Also in this chapter, film, fashion, subculture and other elements of the visual arts industry will be explored. This will later to be applied to the graphic design industry specifically in the next chapter.

One of the first examples of the anti-aesthetic was the Dada movement which, in 1916 Switzerland, a group of artists came together to rebel against the pretentious and highbrow sensibilities of the art world and to reflect the anger, bitterness and unjust society that was the aftermath of the First World War. Feeling oppressed under bourgeois nationalist and colonialist values, the Dada artists wanted to reject conformity and mock those who suffocated under the modern world, which they felt lacked integrity and meaning. Thus born was ‘anti-art’. Perhaps one of the first movements to tear away from classic oil painting and other fine art materials, the artists of Dada used wood, sand, newspaper clippings, photographs and wool to create temporary and perishable art forms that went against everything the art world had held true.

One of the most famous pieces include Fountain (1917) by Marcel Duchamp, in which the artist turned a urinal upside down and placed it out of context to stand in a gallery with the irreverent title ‘Fountain’. Crude, chaotic and illogical by the practices of the time, this piece has held a record of influence, inspiring artists such as Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons. The Dada movement opened a floodgate for rebellion in the art world and the prevalent and political ripples are still felt today. The ‘anti-art’ or anti-aesthetic became a tool for underground, amateur, bored, lonely, angry artists to utilise and make their voices heard above the mainstream.

Fuelled by the Dadaists fighting against the mainstream, rebellion exploded into the art world. What followed would be an influx of experimental and challenging art movements throughout the early 20th century. Although Dadaism seemed to end around 1922, it briefly resurfaced as ‘Neo-Dada’ in the early 60’s. Artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg- whose most famous works included Johns’ ‘Land’s End’ (1963) and Rauschenbergs’ ‘Retroactive l’ (1963) - used the legacy of Dada’s unconventional objects as art and were met with much criticism in which they took delight, for example John’s work being described by one American critic as, “Only further de-aestheticised looking” (citation unknown, Brockes, 2016, The Guardian) Even Marcel Duchamp, forty years after he first began, revelled in the resurgence and continued to create notorious and novelty works as before, including ‘Etant Donnes’ (1966) , considered his second greatest work.

Inspired by this piece, a group named Situationist International (SI) began creating art that reflected their anti-capitalist ideology. Naming Dada, Surrealism and Marxism as their sources of inspiration, SI wanted to break down the divide between art and consumer and make cultural production a part of everyday life. The group wrote many essays and published artists books based on their manifesto, a good example of this being ‘Mémories’ (1959) by Asger Jorn and Guy Debord. Sharing this idea of consumer based art, Pop-Art started to gain attention, both in the US and the UK. Described as, “Popular, Transient, Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young, Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous and Big business” by artist Richard Hamilton in 1957, Pop Art in the UK was more political than its US counterpart and relied more on irony and parody. Allen Jones used sculpture and lithography in his work, for example his 1969 piece ‘Chair’ (Fig.1) was described as “so blatantly fetishistic that to say it objectifies women is a tautology” ( Jones, 2013, The Guardian). Tackling subjects such as sexuality, fetish and male gaze. Jones’ work is a good example of how postmodernism and the anti-aesthetic work hand in hand. Jones’ work questioned the ideas and morals of society at the time and created a clear divide between art and popular culture. In the US, many underground artists were using postmodernism in their own way. Most famously, Andy Warhol was taking popular culture and subverting it, commenting on consumerism and the irony of the ‘American Dream’, for example Warhol’s ‘Campbell's Tomato Juice Box’ (1964) is described as “Appropriating and reproducing Campbell’s packaging outright, Warhol shifts the viewer’s focus from “original” artistic idea to the meaning evoked by a ubiquitous American food brand.” (MOMA, date unknown). A clear example of early anti-aestheticism; Warhol’s work was criticised and seen as vapid, shallow and going against the long established beliefs of what art should contain.

However, Warhol’s art pieces were not the only medium he used to rebel against the art world. Perhaps less popular, Warhol created over 500 short films, dubbed ‘screen tests’, which were often silent, non-linear and had little or no plot lines. The content of the films themselves were often pornographic and featured close celebrity friends of Warhol, such as Lou Reed, Edie Sedgwick and Nico. Warhol also created three experimental films which he named ‘anti-films’ titled ‘Kiss’, ‘Eat’ and ‘Sleep’. These films were met with heavy criticism at the time, mostly due to the fact they were gratuitously long, with their running time between five and eight hours long. However, retrospectively, these films are seen as a turning point in the crossover between art and film. “Warhol is the most dramatic example of an artist misunderstood and slighted in the 20th century but now, at the beginning of the 21st century, loved and valued.” (Jones, 2001, Candid Camera, The Guardian). Pop Art can be included in early anti-aesthetic movements because it is the most popular contemporary example of art being created for the artist’s own moral and political agenda rather than tailored to the taste of the critics. This, in itself, became anti-art by the standard of the conventional art industry.

Inspired by Warhol, a young artist named John Waters was creating films in Baltimore that both disgusted and delighted the underground cinema world. Starting with silent shorts and collage style films such as Mondo Trasho (1969) (Fig.2), Waters ignored critics to create bizarre, experimental and very controversial films. Scenes that included chickens being crushed during intercourse and drag queens eating fresh dog faeces made Waters’ films infamous and still referenced today.

However, it wasn't content alone that made Waters’ films part of the anti-aesthetic. Stylistically, Waters’ films rebelled against the norm by having a ‘home video’ and cheap aesthetic. Against the polished and high budget films that the 1970’s film industry were beginning to produce, Waters’ films stood out. Like Warhol, Water’s films varied in length, rarely had linear plot and were extremely low budget. “I didn’t even know there was editing...My first choice was always writing a concept that people would want to see, even if I didn’t sell it very well.” (Waters, 2014, The Dissolve Magazine). The idea of using the anti-aesthetic in films makes the concept more accessible to the mass audience. Warhol and Waters both utilised this and also established the anti-aesthetic so that it’s still as relevant today as it was in the 1970s. The socio-political agenda of creating art and film for the people inspired generations of artists who may never have had the exposure without accessible cinema.

Also within the industry, it's been said that artist filmmakers such as Warhol and Waters were early pioneers of the punk movement; often seen as the ultimate expression of the anti-aesthetic. “I identified with that community...Pink Flamingos was a punk film but we didn't have a name for it.” (Waters, 2015, East Bay Express). Debatably, punk began in the early 1970’s in the UK and with it brought a tidal wave of innovative visual art. Punk dominated the creative underground world, from music and fashion to film and graphic design- which will be explored in the next chapter. Revolutionaries such as Jamie Reid, who coined the ‘ransom note’ punk staple (fig.3) and paved the way for the amateurs to step forward and leave their mark on the punk scene. Reid famously designed the covers for most of The Sex Pistols albums and created posters influenced by pop culture. “These were raucous, vitality-filled transmissions from a turbulent graphic universe totally different in intention and effect from the smooth, orderly, design history-conscious parallel universe of professional design aesthetics, purposes and training.” (Poynor, 2016, Design Observer) Away from the overexposure of punks money makers such as Vivienne Westwood and The Sex Pistols, the creative individuals, finding solace in the punk message, got creative and designed their way into fame. This began with the rise of DIY punk zines, that were often fanzines created by teenagers in their bedrooms. Using xerox, collage and handwritten type, zines went against any type of magazine aesthetic and in turn created their own, now iconic, anti aesthetic.

The next chapter will investigate how the influences of the visual arts industry have impacted upon graphic design and vice versa.

Chapter Two- How has the anti-aesthetic movement has impacted the graphic design industry?

Despite its roots in the marginalised, underground circles of the visual arts industry, the concept of the anti-aesthetic continues to leave a prominent mark in graphic design. From revolutionising the power of the poster to making protest and political art more accessible, anti-aesthetic is still seen everywhere. This chapter will explore how punk-inspired poster art became popular while also discussing how this worked in partnership with protest art and design. It will also review how political design has developed its own design codes and influences and how this is still used today.

With the art nouveau-resurgence psychedelic posters of the 1960’s, poster art became more than just an advertising tool and became an art form in its own right- but it wasn’t until the punk movement when poster art became more accessible. An art degree was no longer required and amatuer artists saw an oppotunity to create their own interpretations. Hand in hand with the music industry, a rise in DIY aesthetic made way for artists such as Mark Perry, whose works include Sniffin’ Glue punk zine (1976-77) and Linder Sterling, who co-created the infamous ‘Orgasm Addict’ (1977) (fig.4) album cover, to cross mediums by being musicians and artists, combining their passions to create raw and innovative design.

“...DIY projects represent an attempt by people to resist corporate culture saturating the Western world, oppressively narrowing design choices and restricting personal expression.” (Lupton, 2006)

Punk was always political but artists such as Sterling used their political stand-points as inspiration for their work. In an age where women's magazines were domestic in content and sports and porn dominated men’s magazines, Sterling used collage in her posters to subvert this sexist ideal. "So, guess the common denominator – the female body. I took the female form from both sets of magazines and made these peculiar jigsaws highlighting these various cultural monstrosities that I felt there were at the time." (Sterling, undated, quoted The DIY movement in music, art and publishing, 2016). This style of work became the early stages of protest art as the industry knows it today.

The late 1970s/early 80’s were a time of political turmoil, with gratuitous police brutality and violence on the streets which culminated with the Miners’ Strike of 1984-1985. The injustice and unrest that people felt was cause to create a visual identity of the angry working class. The miners’ strike influenced graphic design by giving a platform to regular people who created art out of frustration and anger, in a similar way to the punk explosion in the music industry. Where it differs from punk, the protest art of the strike was not against the aesthetic but instead it rejected any sort of aesthetic because the art was not to be appreciated or admired. It was created out of a sense of urgency to make a point. “These images are important and have value because they are the spontaneous, authentic and urgent expression of political ideas and demands and of the motivations of the strikers”. (Rick Poyner, 2015, In loving memory of work) However, punk proved to be influential among the protest artwork, with the anti-government rhetoric of punk being applied to current political unrest. The anger at the figureheads of austerity, that was a foundation for punk, was echoed in the miners’ artwork, such as the ‘God Save the Queen’ (1977) (fig.5) poster by Jamie Reid, inspired campaigns across the protest, especially the ‘Victory to the Miners’ (fig.6) posters by Paul Morton which had the slogan across an image of Margaret Thatcher. “The majority of the work from that time had an instant design feel to it reminiscent of a (past) punk culture.” (Ian Anderson, 2015, In loving memory of work).

These two movements, punk and the miners’ strikes, paved the way for protest art and allowed amatuer artists to get creative.“I have seen many stimulating images made by ‘amateurs’- we designers should learn from them.” (Ken Garland, 2016) This had a large impact on the graphic design industry, proving that an art degree wasn’t necessary to create iconic imagery. In contemporary culture, this idea is still be utilised during times of political injustice. The ‘Occupy’ movement of 2011 is a prime example of this, where people protested against the social and economic injustice in society.

Once again, a disdain for a conservative government fuelled this movement and drew many parallels to punk and the miners’ strikes when the vandalisation of the figurehead was used (Fig.7). This demonstrates that this imagery has become an unspoken graphic symbol of protest and therefore has greatly impacted on the graphic design industry. Protesters adapted a variety of imagery and slogans from punk and the miners’ strike and applied it to their current situation. What is apparent after protests is that the rushed, amatuer work becomes instantly more iconic than work created by trained graphic designers who spend months on a project, with many more people discussing the artwork and recognising the integrity and passion behind the work.

Towards the end of the 1980’s, protest art was still an influential part of graphic design. Most prominent was the rise of the Guerrilla Girls movement. Initially a group of anonymous protesters, the group fought against the gender and race inequality in the art world. In parallel to the collage work of punk designers, the Guerrilla Girls used clever and subversive collage for their posters. A famous example of this was their poster highlighting the disproportionate number of female artists to nude female paintings in the MET gallery in which they placed a gorilla head over the nude subject of ‘La Grande Odelisque’ (1814) by artist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (fig.8). The use of a gorilla head came from a misspelling of Guerrilla in an early meeting, but was later reclaimed by the group as a fitting symbol of aggressive masculinity that juxtaposed with the message of the movement. This subversion of gender roles reflects the political message that Linder Sterling utilised in her work in the 1970’s and can still be seen in contemporary graphic culture.

During the first few weeks of 2017, the ‘Women’s March’ that has been rallying against Donald Trump has become another example of this. Once again, many images of Trump, the figurehead of injustice, have been defaced as an act of defiance. This global demonstration attracted attention owing to the eye-catching and memorable imagery created by protesters (Fig.9). The use of collage, clever slogans and bold colours were seen being widely used across the protests, clearly influenced by the protest work of feminist like Sterling and the Guerrilla Girls, but is also very reminiscent of the protest work of the miners’ strike. (Fig.10) This demonstrates that there is a clear graphic design code within protest art which has it’s roots firmly in the anti-aesthetic ideal.

The graphic language of protest artwork, despite there being no set trend or rule system (as there often is in other graphic design movements,) follows a similar design concept. This shows how greatly anti-aesthetic movements such as punk and protest art have impacted upon the visual arts industry, especially in graphics, allowing for amateurs and non-designers to access a graphic community that may otherwise be unavailable. In a contemporary context, a lot of this can be attributed to the rise of social media, with innovative and stand out designs being globally shared and therefore inspiring other protesters and protest art designers. Before this rise in technology, clever and influential anti-aesthetic design was publicised and distributed through DIY zines and album covers which, in itself, inspired a generation of amatuer designers. Thus proving that anti-aesthetic is more accessible than ‘aesthetic’ current trends within the graphic design industry- trends that may require in depth knowledge of the industry and make reference to popular but previously niche aesthetics that isolate amateurs and people wanting to pursue design from their bedrooms.

Unfortunately, as with most underground and rebellious movements, the anti-aesthetic has been picked up by large corporations and used to advertise and promote products. In the final chapter, this essay will discuss how large companies are using the anti-aesthetic and stripping it of it’s integrity and how it disempowers political protest and saturates the anti-aesthetic as a movement.

Chapter Three- How do large companies use the anti-aesthetic in their advertising and how can this be harmful to the political side of the movement?

With the anti-aesthetic gaining momentum and popularity, naturally large corporations jump onto the trend in an attempt to appeal to a certain demographic. Companies such as Nike and Rimmel use imagery from punk, protest and the anti-aesthetic as a whole to promote their products. In this chapter, this essay will explore the different companies who use an ‘anti-aesthetic’ look in their advertising and how a rise in ‘protest style’ advertising may be taking genuinity from real political movements.

In advertising, companies are always looking for new, upcoming and popular trends to utilise and appeal to their own different demographics. Most companies look to appeal to teenage/young adult audiences as, owing to the rise of social media, they have the power to make or break an advertising campaign. Advertising agencies must tread carefully with campaigns in contemporary culture, as one wrong move could cause the company to trend online for the wrong reasons- for example, the company Protein World trended worldwide for their controversial ‘Beach Body Ready’ campaign in 2015.

To avoid this backlash from the target market, companies tend to reference popular fashions and pop culture in their campaigns- hence the anti-aesthetic becoming one of the most used trends in advertising. Resonating with young, rebellious, outsider teens and young adults, the anti-aesthetic is used across advertising for a range of different companies. Nike shifted away from the punk history of the anti-aesthetic and instead, in their most recent campaign, used a anti-aesthetic inspired by film. Created by and starring singer FKA twigs, Nike’s latest advertisements resemble an art house film and use interpretive dance, actors of colour and actors who don’t fit the usual ‘beauty’ aesthetic. (fig.11&12) Opposed to more traditional sportswear campaigns, Nike have subverted this and create an obscure and daring- almost political- video campaign that goes against the normal aesthetic of advertising, therefore utilising the anti-aesthetic in an unusual and innovative way.

However, many advertising companies get this wrong and create a patronising campaign that is obviously pandering to a culturally alternative demographic. Rimmel London, as an example, use the ‘punk’ anti-aesthetic to promote their product, with campaigns set to early punk music and a consistent punk imagery used in their advertisements. The company references the London punk scene of the 70’s, with the Union Jack, leather jackets and D.I.Y text imagery across a large majority of their campaigns (fig.13). Although seemingly harmless, if not a little patronising, this use of the punk anti-aesthetic tends to come across shallow and lacking integrity. Punk rebelled against everything these large, multi-million dollar companies represent and to use their anti-aesthetic seems disingenuous. Rimmel is also guilty of using ‘protest’ as an aesthetic in their campaigns.

Titled ‘A lipstick revolution’, Rimmels campaign of late 2015 used protest imagery, such as rallies of models in sexed up military wear, an ‘R’ in a circle- referencing the anarchist A symbol (fig.14,15 &16)- and the tagline of ‘The Revolution needs you!’. This style of advertising would seem harmless if not for the current political climate, where so many people in today’s society actually go out and protest against injustice and are genuinely attempting to revolt against the unfair powers in the government. “By co-option of a revolutionary and protest aesthetic, the companies are obtaining a ‘new’ look that has not been used before and all the while, redacting any political messages that come with it. The politics are being stripped from the protest ‘look’, which is being repackaged as a consumerist choice.” (Mould, 2015).

This is not the first time fashion and beauty companies have misused and appropriated important protest imagery to advertise their products.

In 2014 Chanel used a staged ‘feminist protest’ to end the SS15 catwalk show, with head designer and notorious misogynist Karl Lagerfeld leading an ‘army’ of models wielding banners that read ‘Free Freedom’ and ‘History is HER story’. This stunt, like the Rimmel campaign, were publicised at a inconsiderate time, considering the Women's rights and the Black Lives Matter protests that were happening in America at the time, and rather than supporting the causes, it took away the integrity and power from the real life protesters.

As discussed in the previous chapter, protesters and people fighting against political injustice need and use this graphic language of protest to make an impact and be taken seriously in what they're protesting against. By companies this anti-aesthetic, the real imagery of protests that should be inspiring and recruiting others to join, is being saturated. Poyner summed this up in 2016 when he stated, ‘They deserve to be preserved and studied because they are part of our social history...conservation and study would apply to the graphic images and messages of any protest on this scale.’ (Poyner, 2016) This issue is especially important for protests regarding gender equality and LGBTQ+ rights, as the Government rarely regards their protests seriously.

There are, of course, other large companies that use the anti-aesthetic as a marketing tool. Shoe brand Dr Martens is an interesting example. In the 1970’s/80’s, Dr Martens became a staple in the punk, skinhead, two tone and new wave subcultures - supporting the underground and rebellion of the time. They also became synonymous with the working class, selling their comfortable, affordable footwear to milkman, postman and miners. However, after a near bankruptcy in 2003, Dr Martens rebranded and attempted to appeal to a wider audience and collaborated with high fashion designers to customise the shoes. Although they still marketed themselves as an ‘underground’ choice of footwear, the company began to make billions.

Despite their profits soaring, Dr Martens started to lose integrity and quickly became a mainstream brand with shoe prices rising to almost unaffordable prices- all the while peddling the brand as ‘A symbol of self-expression and individuality’ (ODD London on the DM Stand for Something 2013-16 campaign). This campaign told consumers to ‘Stand for Something’ (Fig.17) but failed to maintain the rebellious and ‘stick it to the man’ image and caused controversy with poor references to skinhead culture in a brochure claiming, ‘The boot (was the group's) weapon of choice.’ (2015 Dr Martens’ brochure). With this, Dr Martens follows a similar pattern to Rimmel, as aforementioned - a seemingly disingenuous attempt to commodify and fetishise current protest/anti-aesthetic language and imagery as a way to push product sales.

Commodifying current political trends is an unfortunate yet prevalent marketing tool in advertising, with protest, anti-aesthetic and feminism being the main targets, as contemporary examples. This trend has had a big impact on the graphic design and visual arts industry and has become a relatively lazy go-to design concept for companies to appear ‘edgy’ and keep up with popular culture. The anti-aesthetic, from its conception to present day, has been an important tool for underground and amatuer designers to express themselves and a way to break into the mainstream. With large, profitable companies using this aesthetic, it somewhat takes away from smaller designers who used the concept to stand out and be noticed. As Poyner stated, ‘The power of protest graphics always come from the sense that the people saying these things really do mean it.’ (Poyner, 2016) By saturating and commercialising the anti-aesthetic, there is little left in the way of design concepts and movements , for amateurs to relate and express themselves.

Conclusion

In summary, the anti-aesthetic movement has made the visual arts industry more accessible. It’s given people sitting at home in their bedrooms the opportunity to express how they feel about the world around them and tells the story of the things that have affected and interested them. It has allowed free thinkers to break the bonds of the previously conceived stuffy and formulaic art world of the 19th Century and radically change the artistic landscape. It has given amauter and aspriing designers an opportunity to shock and surprise critics and challenge the social and political norms of the day.

From it’s conception in the fine art world, the anti-aesthetic has weaved its way through all mediums of the visual arts, inspiring filmmakers, fashion designers, musicians and graphic designers alike. Perhaps most surprisingly, the anti-aesthetic has not only had a great impact upon the visual art industry but also changed the language of protest art and has had a political impact. Whilst large advertising campaigns seek to commercialise and normalise protest art, each protest creates a wave of new and innovative artwork, adding to the anti-aesthetic graphic language that has evolved. Exhibitions such as ‘Disobedient Objects’ (2014, V&A Museum, London) are immortalising the best and most powerful of protest art, while books, such as, ‘In Loving Memory of Work’ (2016, Craig Oldham) capture the explosive and poignant imagery from a specific movement.

The anti-aesthetic is more than just temporary trend. The movement has not only impacted the visual arts industry greatly, but has also impacted our culture. Without Dadaism, punk and protest art, our society would not have such variety and opportunities for today’s young artists. The anti-aesthetic teaches that no style, no approach and no voice is wrong and there are no limits on what you can create and achieve. Without the anti-aesthetic, the visual arts industry would be very exclusive and dull . Despite the anti-aesthetic not being as explosive as in it’s heyday, for example in the punk era, the beauty of the anti-aesthetic is that it will never go out of style- there will always be something to stand up for, and to fight- and with that the anti-aesthetic movement will live on forever.

Submitted as a Dissertation

0 notes