#new york review of books

Photo

Rosemary Mayer, Some Days in April (from Temporary Monuments), Hartwick, New York, 1978 [«The New York Review of Books». © The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York, NY]

#art#photography#mixed media#magazine#rosemary mayer#estate of rosemary mayer#new york review of books#1970s

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Cinema Detectives - a short film about the comics and life of Chris Reynolds (producer: Jonathan Tapsell).

#Chris Reynolds#Cinema Detectives#Jonathan Tapsell#Laurel Award#Mauretania Comics#The New World#New York Review of Books#❤️

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abed Salama with a photograph of his son Milad, al-Bireh, West Bank, March 2021

Heading Toward a Second Nakba

nybooks.com/articles/2023/10/19/heading-toward-a-second-nakba-a-day-in-the-life-of-abed-salama/

David Shulman

Nathan Thrall argues that the accident in which Abed Salama’s son died was a predictable, even inevitable, outcome of the Israeli occupation in its quotidian forms.

On a stormy winter day in February 2012, a Palestinian bus carrying schoolchildren on an outing collided with an Israeli trailer truck on the notoriously dangerous Jaba‘ Road near the West Bank village of A-Ram, not far from Ramallah. The bus burst into flames; six young children and one teacher were killed and others were seriously injured. Among the dead was Milad, the five-year-old son of Abed Salama, from the town of Anata. Nathan Thrall has made the story of that accident and that family the thread that binds together A Day in the Life of Abed Salama, a penetrating, wide-ranging, heart-wrenching exploration of life in Palestine under Israeli occupation. I know of no other writing on Israel and Palestine that reaches this depth of perception and understanding.

...

Critical moments were wasted at Israeli checkpoints, preventing emergency services from arriving at the scene.

No one wanted to kill those children along with one of their teachers. Israeli rescuers and soldiers who finally reached the accident site did their best to save the injured. But the central point of Thrall’s narrative is that this disaster, like today’s ongoing violence in the Palestinian territories in general, was a predictable, even inevitable, outcome of the occupation system in its quotidian forms. It is a regime of state terror whose raison d’être is the theft of Palestinian land and, whenever possible, the expulsion of its Palestinian owners. I have seen this system in operation over the course of the past twenty-odd years.

...

One of the mysteries attendant on Israel’s decades-long occupation of the Palestinian West Bank (and indirectly of Gaza) is that relatively few people know that reality for what it is. Mainstream Israelis by and large don’t want to know, though the West Bank is only a few miles from the big Israeli cities. Outside of Israel, an efficient smokescreen created by the Israeli government has largely hidden that reality from the world. Those who do know it well, from the inside, are Palestinians living under the occupation and human rights and peace activists, both Israeli and Palestinian, who are regularly present there.

...

Brutal military occupation generates such casualties, just as it generates resistance on the part of the occupied. But the most telling change in the West Bank is the rapid proliferation of new settler “outposts” (ma’ahazim), as they are called, usually inhabited by young men and women imbued with a messianic ideology, burning racist hatred of Palestinians, and a proclivity for extreme violence. We activists encounter these settlers every week (some of us almost every day) in the territories. The outposts, theoretically illegal under Israeli law, have proved to be an effective mechanism for taking over large stretches of Palestinian land; the settlers and their representatives in the government have made no attempt to conceal this explicit goal. The army and the police invariably side with the settlers, sometimes by passive acquiescence in their attacks, sometimes by actively taking part in them. [emphasis mine]

Lately, settler violence has taken the form of large-scale predatory attacks on Palestinian villages—what I, in the light of my own family history, can only call pogroms. (My granduncle was murdered by Cossacks in Ukraine before World War I.) On the night of February 26 in the northern West Bank, hundreds of armed settlers descended on the village of Hawara after two settlers were shot dead that day by a Palestinian. Palestinian houses were burned to the ground, vehicles were torched, innocent civilians were attacked, and one Palestinian man—a gentle peace worker, as it happened—was shot to death. A similar outrage was perpetrated by Jewish settlers in the village of Turmus‘ayya on June 21. Such attacks, usually accompanied by machine-gun fire, are now common, though they may vary somewhat in scale. Palestinian villagers in Area C of the West Bank, where all the Jewish settlements and outposts are located, live in constant fear.

...

The aim—openly espoused by government officials such as the minister of finance, Bezalel Smotrich—is to pave the way for a second Nakba, or catastrophe, as the exodus of Palestinians from their lands in the course of the 1948 war is referred to in Arabic. If life for Palestinians in the territories becomes unbearable, they will, the settlers think, just go away—maybe to Jordan, Saudi Arabia, or some other Arab country. This sick fantasy turns up regularly on the settler websites.

...

More at the link.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timothy Garton Ash:

Tetiana, a young activist I met in Lviv last December, works part-time as a tattooist. People often ask for tattoos of the Ukrainian flag or the country’s trident symbol, she told me, but one of the most popular since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine a year ago is the word volya, which means both “will,” as in willpower, and “freedom.” It captures the essence of what I saw in Ukraine—and of what Ukraine is reminding the world.

“The secret of happiness is liberty,” Thucydides has Pericles say in a funeral oration in ancient Athens, the birthplace of democracy, “and the secret of liberty is courage.” The courage to live and die for freedom is most obviously apparent in the men and women of the Ukrainian armed forces.

The Ukrainian state has had a checkered record over the three decades since the country gained independence in 1991, but Ukrainian civil society has grown from strength to strength, through three major episodes of popular mobilization: the Orange Revolution of 2004–2005; the Euromaidan, or Revolution of Dignity, in 2013–2014; and the response to the Russian invasion in 2022.

A family from Kramatorsk, near the front line in eastern Ukraine, proudly showed me photos of the Ukrainian soldiers now based in their house, and of the ammunition and land mines stored in what used to be their chicken shed. They also demonstrated how locals reported the position of Russian units to the Ukrainian army, using annotated maps on their phones. Everyone seems to be doing something: sending food, clothes, or equipment, helping internally displaced people, or—like Max, a young volunteer I met—traveling repeatedly to the east to bring back the old and sick from villages in the line of fire. In a July 2022 survey, 61 percent of Ukrainians said they had participated in the resistance by donating funds, 37 percent by volunteering in the community, and 7 percent by volunteering in the Territorial Defense Force units established to complement the regular armed forces. “The Ukrainian army is 42 million people,” Andriy Sadovy, the mayor of Lviv, told me—the entire country. If ever there was a people’s war, this is it.

The same ingenuity and spirit is apparent in the ways Ukrainians are standing up to Vladimir Putin’s criminal targeting of the country’s energy infrastructure, roughly half of which has been damaged. The characteristic sound of downtown Lviv is now the loud chug-chugging of small generators outside shops and houses. Over the Christmas holidays, travelers at Kyiv’s central station were invited to power the lights on a large Christmas tree by pedaling an exercise bike connected to a dynamo. “Ten seconds of light! Ten seconds of jolly mood!” cried a man dressed as Santa Claus.

Amazingly, in polling conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) last September, 68 percent of Ukrainians answered yes to the question “Do you consider yourself a happy person?,” compared with just 53 percent in 2017. When I asked the sociologist Nataliya Zaitseva-Chipak to help me understand this phenomenon—how on earth could people be happier during a war of terror directed against the civilian population?—she replied, “Yes, I’m happier!” It wasn’t just the overwhelming sense of common purpose, she explained. It was also appreciating everything you still have when your compatriots are suffering so much worse in the trenches or the pulverized city of Mariupol. One journalist even told me her friends say that “it’s okay if the missiles are falling on us because it means they’re not killing our soldiers on the front line.”

(New York Review of Books). ( Ukraine in our Future : Yimothy Garton Ash)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about architect Victor Horta's Hotel Tassel in Brussels after reading this story by Martin Filler about Art Nouveau.

Photo from UNESCO's World Heritage entry on the building.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

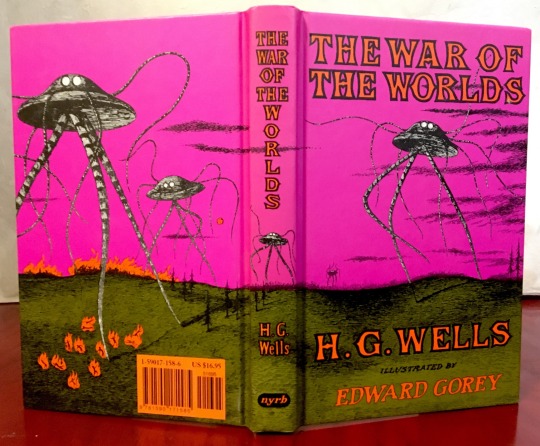

Book 037

The War of the Worlds

H.G. Wells / illustrated by Edward Gorey

New York Review of Books 2005

The first of many Edward Gorey books in my collection. I remember being surprised that Gorey had illustrated this book when I first saw this reissue. Martians seemed a little outside of his wheelhouse, but I knew this book would be coming home with me. A fantastic NYRB production.

#bookshelf#illustrated book#library#collection#personal library#personal collection#bookseller#books#book lover#bibliophile#war of the worlds#hg wells#edward gorey#nyrb#new york review of books#fiction

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read this review of a new biography of Bronislava Nijinska, the sister of Vaslav Nijinsky, and this section near the opening has me hooting and hollering. How are you going to be a ballet dancer for any extended period of time without having powerful thighs, you cowards? People pick the weirdest stuff to be sexist about. Like look at this picture and her smile, those teeth. I’d kill to have teeth that nice. And these assholes are complaining?

Also the article has some great jabs at Balanchine, which I love. Hate that guy, weirdo, stole choreography from women.

#ballet#ballet russes#dance#choreography#art#bronislava nijinska#vaslav nijinsky#new york review of books#nyrb

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lament for Julia - Susan Taubes (1960s) NYRB

1 note

·

View note

Text

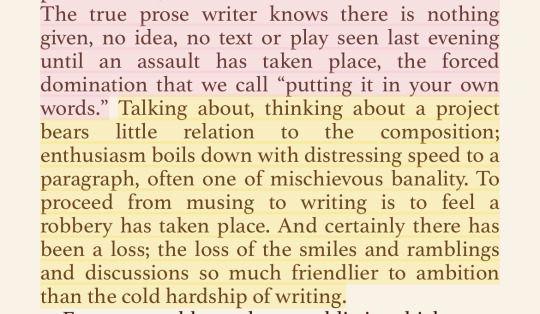

Elizabeth Hardwick, from “The Art of the Essay” The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (New York Review of Books, 2022)

#elizabeth hardwick#new york review of books#prose#writing#quotes#the art of the essay#dark academia#academia aesthetic#literature

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bought some books today

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leiris must feel, as he writes, the equivalent of the bullfighter's knowledge that he risks being gored. Only then is writing worthwhile.

#susan sontag#new york review of books#susan sontag 1964#odd man out#michel leiris#march 5 1964#gored#writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Italo Calvino, Mondo scritto e mondo non scritto (1983) [Institute for the Humanities, New York University, New York, NY, March 30, 1983: 'The Written and the Unwritten World’, The «New York Review of Books» May 12, 1983, pp. 38-39; then in «Letteratura internazionale», II, 4-5, 1985, pp. 16-18]; in Mondo scritto e mondo non scritto, «Opere di Italo Calvino», Edited by Mario Barenghi, Oscar Mondadori, Milano, (2002-)2006, pp. 114-125

#graphic design#mondo scritto e mondo non scritto#book#italo calvino#mario barenghi#new york review of books#letteratura internazionale#opere di italo calvino#oscar mondadori#arnoldo mondadori editore#1980s#2000s

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

The concrete effects of that affordability crisis can be felt and seen throughout the city. Local eviction moratoria have expired just as federal Covid relief diminishes and rents skyrocket at a pace with which working and even middle-class New Yorkers can’t keep up. City shelters see more families, and single men especially find themselves either without a stable place to stay or on the streets. Without support, mental health issues go untreated and drug use increases. 2,668 people died of drug overdoses in New York City in 2021, an increase of 78 percent since 2019 and 27 percent since 2020. Overwhelmingly, these New Yorkers were Black, Latino, and low-income. The city’s oppressed are not only struggling, they’re dying from despair on its streets in unprecedented numbers.

People experiencing deep hardship and pain are more visible in the city than they have been in some time, especially in the subway. When the city took proactive steps to find housing for people at the height of the pandemic, it dramatically cut down on the number of people sleeping outdoors. But once those steps were no longer taken, the amount of people on the streets rebounded to over 3,400, a number many advocates for the homeless believe was a drastic undercount.

For those not familiar with some of the broader and historical context of these problems, take a look at the below article if you have access to it.

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/08/17/tenants-under-siege-inside-new-york-city-housing-crisis/

Marxist analyses practically write themselves.

#new york review of books#nyc#new york city#eric adams#homelessness#social services#neoliberal austerity#housing#public health#deaths of despair#poverty#mental health

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meditative Week of Poetry: Rae Armantrout

1.

I take a step back

and it’s like dancing.

But what would it mean

to “return to my roots”?

Is that what the flowers do

in September?

2.

Kids earn money

and love

by being themselves

on YouTube.

“It only works

if it’s authentic.”

Was it better

when enthusiasms

had objects—

such as distant wars

or tulips?

Now we pay attention

to attention.

Take a step back,

and it’s like dancing.

What would it mean

for attention to be empty

as a phrase

repeated too often?

0 notes

Text

Book 039

The Haunted Looking Glass

Edward Gorey

New York Review of Books 2001

This collection of classic ghost stories chosen and illustrated by Gorey is another great NYRB reissue. Although I wish it had also been a paper over boards hardcover like the others.

#bookshelf#illustrated book#library#collection#personal library#personal collection#bookseller#books#book lover#bibliophile#haunted looking glass#edward gorey#nyrb#new york review of books#fiction

5 notes

·

View notes