#nikau hindin

Text

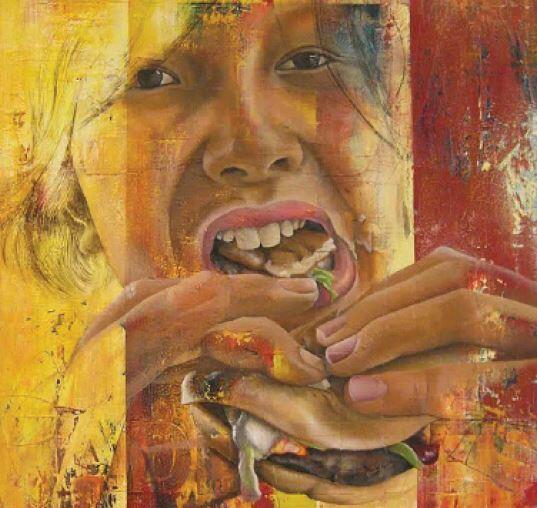

Illustraciones: Nikau Hindin, Obesity and Junk Food, 2009, @nikaugabrielle

En los últimos 60 años se ha producido un aumento exponencial de la producción y el consumo de “alimentos” -o mejor dicho, productos comestibles- ultraprocesados (UPP por sus siglas en inglés), como patatas fritas envasadas, galletas, bebidas azucaradas y comidas preparadas. Gracias a la expansión del sistema alimentario industrial, y de las estructuras mundiales de abastecimiento y venta al por menor, y a la concentración y el poder de las empresas dentro de este sistema, los UPP están sustituyendo a los alimentos frescos y mínimamente procesados y a las comidas caseras en nuestras dietas. Los hábitos alimentarios se van haciendo cada vez más homogéneos y las tradiciones culinarias están desapareciendo. Este cambio comenzó en los países de renta alta y ya ha llegado a todos los países, representando en algunos de ellos más del 50% de lo que la gente come. [1]

Esta edición del boletín de Nyéléni explora el modo en que la “dieta corporativa” basada en los UPP se está imponiendo en diferentes regiones del mundo y lo que esto implica para la salud y la soberanía alimentaria de las personas. Además, ofrece ejemplos de resistencia, desde la recuperación de cultivos tradicionales hasta la lucha por medidas reguladoras eficaces. Lo que está claro es que para recuperar la soberanía sobre nuestra mesa debemos mirar más allá de nuestras cocinas y reformar el sistema alimentario en su conjunto.

FIAN Internacional y AFSA

– Para descargar el boletín en PDF, haga clic en el siguiente enlace:

👉🏾Nyeleni No. 55(610,82 kB)

Fuente: Nyéléni

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

35ª Bienal de São Paulo Apresenta Mostra em Belém

O Museu de Arte de Belém (MABE) sediará uma seleção especial da 35ª Bienal de São Paulo, intitulada "Coreografias do Impossível". A exposição estará aberta ao público de 3 de abril a 26 de maio, inserindo Belém, pela segunda vez consecutiva, no circuito itinerante da Bienal, que alcança mais de dez cidades.

Curada por Diane Lima, Grada Kilomba, Hélio Menezes e Manuel Borja-Villel, a mostra contará com a participação de artistas como Deborah Anzinger, Edgar Calel, Gabriel Gentil Tukano, MAHKU e Nikau Hindin. A temática aborda as complexidades do mundo contemporâneo, explorando as interseções entre o possível e o impossível, o visível e o invisível, através de perspectivas artísticas que utilizam o corpo e o movimento.

A expansão da Bienal para outras cidades, além de São Paulo, visa a ampliação do acesso à arte e à cultura, permitindo que a exposição atinja públicos diversificados.

Andrea Pinheiro, presidente da Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, e Inês Silveira, presidente da FUMBEL, comentam sobre a realização da mostra em Belém, enfatizando a inclusão da cidade no circuito da Bienal e a oportunidade de acesso à arte proporcionada pelo evento.

35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossívelItinerância Museu de Arte de BelémPalácio Antônio Lemos, Praça Dom Pedro II, s/n3 abr – 26 mai 2024ter – dom, 9h30 – 16h30Entrada gratuita

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Qiane Matata-Sipu - Stories of 100 Indigenous Women

This was quite a striking series of environmental portraiture to encounter, powerful too. The accompanying each kōrero with portraits that depicted these 100 wāhine in environments which linked to their story. Something I noticed in almost every portrait was the use of framing each one with an environment that furthers the story of each individual.

[Left] //015 Kim Tairi, librarian (2019), [Right] //022 Pualani Case, spiritual and cultural leader + kumu hula (2019).

Every portrait was taken in a different location, some in the home, others among nature, a studio or workplace. But each is linked with the wāhine in focus and a part of their story. Something I noticed is that not every one was portrait, some were landscape; some the model was centred others to the right or left. Some had the background as a supporting element (out of focus) whereas others were just as much a part of the background/interacting with it (wider angle of focus).

[Left] //004 Kiri Nathan, fashion designer + entrepreneur (2019), [Right] //100 Karen Matata, educator + marae champion + māmā (2021).

The lighting in the above two portraits were what struck me the most. The front-facing angle of the subject in the left image, very naturally well lit, sort of blends in with the background as though part of it. The opposing direction of the body and head (3/4 in each direction), neither making contact with the camera creates some movement as though the subject is engaging with something beyond the cameras frame. The contrast between the natural light coming in through the window vs. the darker background creates a lot of depth in the image and appropriately places focus on the body neck and face of the subject (particularly the tāniko that collars the korowai), darkening only slightly the right side of their face.

[Left] //059 Julie Paama-Pengelly, tā moko artist (2021), [Middle] //008 Meri Te Tai Mangakahia, suffragist (2019), [Right] //024 Nikau Hindin, reviver of Aute (2019).

I chose the above three for their different profiles and lighting. On the left is very warm interior lighting, informal setting with only the upper body in view and subjects face at a side view. There appears to be some backlighting or top-down judging by the highlight on her hair.

The middle is shot in-studio or a plain interior. With two opposing backlight sources (blue on the right and pink on the left) with spotlighting facing the subject (vignetting occur around the image). Both faces are well lit and the lighting diffused on the face (no intense shadowing)

The right protrait is taken outdoors on an overcast day judging by how much light is falling from the top left onto her face and shoulders (and the background). I would think that a neutral reflector (white or gold) may have been used to lighten the image from the right.

0 notes

Photo

Studio update

I am now doing my MFA at the university of Hawai’i. I came here because there are skilled kapa practitioners here who can help guide me. Wauke/aute also grows better here and there is a small resource I am fortunate enough to tap into. This is the only place in the world I can do my Masters. Here are candid photos of my studio. Yes it is a joy to have my own space to paint, write, cry, laugh and read at my leisure. I feel truly blessed for this opportunity to delve into my potential. The artist flame that has always resided inside me, now has the freedom to explore, experiment, fail and create.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Detail.

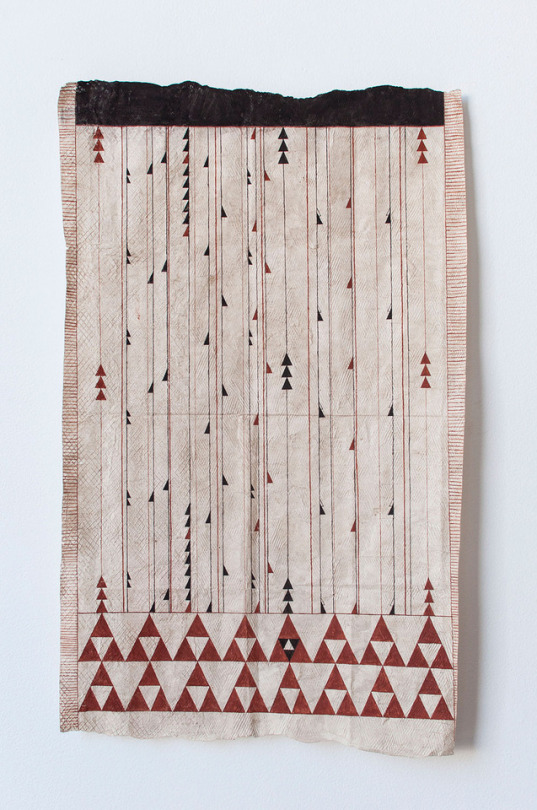

Nikau Hindin - Te Uranga (The rising and setting of the sun due East and due West. Autumnal Equinox. 20.03.2020)

2019 kōkōwai (red ochre), ngārahu (soot pigment) on aute (paper mulberry)from the series Kōkōrangi ki Kōkōwai: From Celestial Bodies to the Earth

1 note

·

View note

Photo

[1] Vaimaila Urale, Aniva, 2019. Black card and sand. Courtesy of Sanderson Contemporary, Auckland, Aotearoa/NZ. [2] Mixed design Tongan kupesi, prior to 1930s. Courtesy the Lady Dowager Fielakepa. [3] Ngatu with spitfire plane motifs, c. 1940s. Photo: Eddie Lam, 2019. [4] Tanya Edwards, Queen Salōte, 2018. Digital print. Courtesy of the artist. [5] Nikau Hindin, Te Tīpare o Hinetakurua, The Crown of the Winter Goddess. (Winter Solstice, 21.06.2020), 2019 (detail). Kōkōwai (red ochre), ngārahu (soot pigment) on aute (paper mulberry). Courtesy of the artist.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toi Te Kupu: Whakaahuatanga

Wananga Toi Maori Conference

Aotea Centre, 15th-16th June 2022

Each artist and contributor had such wonderful korero, so I would like to acknowledge that my summary here is only a brief explanation of what transpired today that relates specifically to the subjects and ideas in my MFA practice. Ngā mihi ki te Toi o Tāmaki, me nga iwi o Tamiki (ngati whatua) me nga hapu o te hui.

He korero whakapuaki: He Atamira a Hautau; Opening Adress: Staging Images, Contemplating Forms: Maori Art& Transformation. Ngahuia Te Awekotuku MNZM

Writer, activist and a leading wahine in Maori arts; Ko Ngahuia Te Awekotuku spoke to decades of her own art practice, as well as Maori matauranga as it relates to the past and future. Her korero began with Maori practices as they relate to whare and marae installations and broader architecture. Her reo explained the way Maori designs of both tupuna and contemporary artists have been ‘objectified and collected,’ noting Ruatepupuke marae which is now in Chicago USA.

She noted how the role of curator relates to this; the naming, positioning and organising of artwork is mostly being done by non-Maori with only recent development in this area. I am specifically interested in how this korero links to my fascination with bromeliad names and titling. The non-maori initiatives within these plants further alienates them from whenua and the landscape they reside.

Ngahuia said that ‘It is te reo that will enrich wider perspectives of the materials on display’

She explained the pouri of stolen taonga, or specific exhibits that displayed Maori artifacts as artworks instead of in museums. These exhibits featured stone, bone and wood, whereas korowai and other magnificent weavings were considered craft and had no place in such exhibits as decided by pakeha. Futhermore, wahine were invited to attend the exhibition instead wearing the korowai/weavings, to be perceived as walking artworks. Her korero, although with sadness and acknowledgment to the pain this would have implemented to her and other wahine artists involved, teaches to me that the ‘craft’ ideologies to do with reception by the art world of textile work, are a specifically Western narrative. Maori matauranga empowers its people's creations, with 'art' and even 'toi' not always accurately encompassing how a Maori creater would describe their work, as brought up by several speakers including Ngahuia, Graham Tipene and Bernard Makoare.

I believe this is something to consider in my practice because of my own Maori whakapapa. Are my ideas that textiles and craft have been blanketly perceived as lesser by the art world considering a Te Ao Maori lense in which this idea not present? Only when presented in a pakeha gallery setting, with Western non-maori curation, do these textile politics truly exist.

Alienation of the textiles that Ngahuia describes as ‘among some of the most complex in the world’ is a disrespect to not just the artform but Wahine Maori. This example of disrespect and yet objectification of such important taonga may have been decades in the past, but what of it resides today? Certainly a lot. Whaea such as Ngahuia continue paving an Aotearoa for Maori artists which is beginning to revolve and reindiginise, but like many of the speakers today alluded to, the broad field of artmaking alone still does not give Maori artists the deserved space.

Whenua as a Source discussion topic with wahine artists Ruakura Turei, Nikau Hindin, Carla Ruka and Nova Paul.

‘I work with Papatuanuku’ is how uku/clay artist Carla Ruka introduced her practice. The other wahine all explained their own relationship with whenua and described embodied responses to the land as a being; with many references to mauri ora and matauranga from the whenua and ngahere itself.

Raukura Turei considers sourcing from the whenua to directly encounter whakapapa. Thus, when using land, uku, or sand one is embodied with whakapapa and whenua as one. Raukura says that she ‘sources where I am drawn to, a calling from my whakapapa.’ She describes a nostalgia coupled with that, because of memories being on that whenua as a child. I won’t write about her tupuna out of respect. I am however, fascinated by her approach to whenua and role as an artist when using this as a medium or subject. Much like other artists in this lineup, her practice embodies such deep mauri and ideas that words such as ‘landscape painting’ in which one may describe her work, does not particularly apply. The turanga wai wai in which the artist’s process begins, and the connection between artist, whenua and tupuna throughout, asks for its placement as a finished object to be considered just that; a vulnerably embodied representation of the artist’s whenua and tupuna.

If I think about ‘whenua as a source’ as it relates to my own practice, I would consider the visual representation as a source as opposed to the physical uku with which some of these artists work. Painting the landscape within Aotearoa has become challenging after a)beginning my MFA and b)beginning the journey of learning my whakapapa. As I begin understanding what whenua means, not just as it looks and not just as it exists to me, the weight of its meaning as an entity and thus the replication of it, dawns new realisations about what my role in that relationship means. It has become important for me to reflect toku whakapapa in my work through whenua, which is why my journey of learning my whakapapa and ancestry is directly linked with my art practice.

This korero has helped solidify my thinking around the bromeliad as a subject which highlights polarities within Aotearoa landscape. It has also opened up questions within my practice, about how certain representations of whenua do or don’t embody the mauri that exists in the land.

Wheako Whaiaro: John Miller, Natalie Robertson

Natalie Robertson hosted a discussion with photographer John Miller, whose documentary photography within various activation spaces has made him a key leading artist in Aotearoa.

This discussions was fascinating as it focused on John's whenua photography, where the subject was nga rakau and ngaherehere. Photographs from the 70s and 80s, during a time period in which Maori land was being leased for up to 99 years by Paper Mills and international companies who were following the ethos that 'land must produce food or pine trees. Maori use must be subdued for good of common wealth.’ When these contracts were being implemented in areas like Putowake, Maori did not know the absolute destructive amount of pine trees planned to be planted.

John's images 'stand as witness to the destruction and change of land.' one particular work shows a panoramic view of the vast Matawaia landscape in 1997. He returned to take an identical image in 2008, and the absolute dense population of pines covers the view. He recalls that the loud birdsong that used to greet him on arrival was replaced with utter silence.

'we often think that pine forest is better than no forest, but what we are seeing here is complete destruction.' further images show a buried house, destroyed by landslides from the foresting works on the maunga. Even the ngahere away from the pine, once hosting thriving native plants, is dismal and dead.

John’s images and korero brings to light the destruction of Maori land caused by pakeha greed. With his work spanning several decades, his photography serves further than an artform and also acts as documentational evidence about these issues.

He Korero: Kia kitea Te Mana Motuhake i te taone: Talk: Visual Sovereignty in the City, Bernard Makoare

Bernard Makoare’s korero brought up wonderful discussions around language as it relates to deferent aspects of Maori art and matauranga.

Words like ‘toi,’ ‘mana whenua’ which in some pakeha contexts have been used as what he describes as a ‘Maori generic’ way of summarising their much deeper meanings. Breaking down these words helps reclaim their mana. For example; what is mana? Refering to Bob Jahnke’s earlier explaination on balance within Maori art in both composition and spirit, Bernard describes mana as a ‘balance between power and authority.’ Power does not have to be an oppressive word, he considers it to define as ‘doing something excellently.’ If mana whenua is the intrinsic nature of what’s imbedded in the land, and as artists we are to apply excellency to the best of our ability when addressing whenua, I am made to rethink the way in which I paint the mauri with Aotearoa’s landscape.

0 notes

Text

For our session with Taarati and Dion on Monday we broke into four groups and went to visit public art around Auckland CBD. Before we visited the pieces we brainstormed questions to think about when we visit the different pieces. The questions were centred around context, materials, story and concept. My group visited the Saint Paul ST Gallery exhibition Speaking Surfaces (2020). Speaking surfaces featured Jen Bowman, Ruth Castle, Nikau Hindin and Ben Thompson, Mabel Juli, Karrabing Film Collective, Emily Parr and Arielle Walker. The aim of the exhibition was to question how do surfaces speak. The exhibition features seven pieces ranging from films to woven dishes. It was good to have the guide as I didn’t entirely understand some of the history and culture behind some of the pieces just from looking at them. It We also visited Lisa Reihana’s exhibition Ihi (2020) at the Aotea Center Foyer. The installation spans 65 square meters and is split between two different screens. The digital piece tells the story of Ranginui and Papatūānuku and Tāne and the separation between Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatūānuku (the earth mother). It is a modern twist on a piece of New Zealand’s history. The modern twist is created through modernising traditional attire and Lisa graduated with a bachelor of fine arts from Elam School of Fine Arts, Auckland University in 1987. She then received her Masters of Design from Unitec Institute of Technology. She became a member of the New Zealand order of merit in 2018 and received a Arts Laureate Award in 2014. The piece features two dancers Taane Mete and Nancy Wijohn. I found that Lisa’s piece made me think about the history and culture of our nation. The picture above is a part of Lisa’s instillation.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Te Uru Aute Presentation

Kia ora whanau, he uri tenei no te hokianga whakapou karakia.

Ko Ngatokimatawhaoroa te waka,

Ko Tapuwae te awa,

Ko Ngahuia te marae,

Ko Ngaitipoto te hapuu,

Ko Ngapuhi me Te Rarawa nga iwi.

Good afternoon whanau, my name is Nikau Hindin and I whakapapa back to the Hokinaga and this is my marae over looking the Harbour.

The revival of traditional practices is a key element to my research project. The Hawaiian waka haurua Hokule’a and the subsequent revival of traditional navigation in the Pacific has been a huge influence on my way of thinking.

This is a star compass up at Hector Busby’s place in Aurere. The star compass is the Polynesian system of orientation – you can see here that the pou line up with the horizon and the spaces between them represent the 32 houses in which the stars rise and fall into.

This compass usually resides in the mind of the navigator and they use points on the waka to calibrate the star houses but when you aren’t on the water this gives students the chance to immerse themselves in the practise of celestial navigation.

An important kaupapa in this project is activating theory through practice. My Maori Studies Degree became more relevant to me when I discovered Dante Bonica’s workshop. In his classes, you come to the Auckland Museum and replicate taonga tawhito using traditional methods and tools. Neither words or pictures can do justice to the experience of making taonga the old way. Working this way gives you an intimate awareness of the material your are interacting with because the process is so slow and repetitive. I often work with wood and when you use these tools you learn about the materials weaknesses and strengths, its weight and balance, its knots and grain. From Dante’s classes I became in awe of the ingenuity and craftsmanship of our tupuna and my desire to learn more about their traditional practices grew.

One Day Dante showed me this aute plant and told me it was special because our tupuna used to grow aute.

The importance of this tit bit of information didn’t sink in till I went to the University of Hawai’ and learnt how to beat wauke into kapa and then learnt that wauke translates to aute in Māori. When Maile Andrade mentioned that Maori once beat kapa too I was surprised I knew nothing about Maori tapa cloth… and that’s when I remembered Dantes aute plant and the ability to continue to this practice in Aotearoa inspired me to begin this learning journey.

What you are seeing was my first mini wanaga where we scraped the outer bark and prepared the aute for soaking.

After the bark has been soaked it becomes soft enough to beat.

One of the aspects I loved about beating kapa in Hawaii, that hasn’t manifested here in Aotearoa- YET- was the communal nature of beating, as well the refined process that came from generations and generations of practice.

I am still a student of this practice so my project seeks to refine my own skills in making bark cloth as well as share this practice with my peers and community.

An important lesson Dante has taught me over the years of working with stone tools is that your outcome is only as good as your tools. Fortunately for me I have been able to study the Auckland Museum’s collection of Maori tapa beaters.

The quality of some of these beaters is astounding – the grooves are so fine and straight. Examining these tools gives us clues into how our tupuna once beat tapa. It also instructed the way I made my own beaters, and helped me make decisions about the width and depth of the grooves.

The idea when you are beating is that you slowly spread out the fibre. It is a bit like felting.

It is a privilege to be able to have access to the beaters here and not only replicate the tools but use them, thus replicating the physical movements of our tupuna and reawaken the sound of this process which may not have been heard by this land for hundreds of years.

The Tainui whakatauki “Te kete rukuruku a Whakaotirangi” speaks of one womens far sightedness Whakaotirangi was Hoturoa’s principle wife. The story goes that on their journey from Hawaiki, while the rest of the crew ate their kumura seed she kept hers safe by tying a firm knot in her basket that helped preserve these kakano. When they arrived in Aotearoa she planted kumara, calabash and aute all of which flourished exceedingly.

From beating aute I have learnt that there are limitations to the aute tree at Dante’s due of its age. It is almost as if the aute I am using “hasn’t been told that it is going to become bark one day- so when I process it- it must get a bit of a shock from it’s transformation.”

Simmons is important to this jigsaw puzzle because Matua Dante got his aute tree from Simmons along time ago. Dante kept telling me that these aute tree send underground roots out which means aute treese pop up a few meters away. Our aute tree at school is surrounded by concrete so this hasn’t occurred. At Simmon’s place however, there is one main aute and about nine baby ones.

Ulitmately to sustain this practice we need more aute material and we need to plant more aute. The wauke in hawaii is harvested young, with intention of being processed and beaten into cloth. When I saw these beautiful, straight young aute I knew that these plants- if pruned and looked after correctly- would produce fine aute.

Looking forward I hope to plant an aute grove that can be harvested for making Maori tapa in the future. In the mean time, I have enough bark soaking and enough beaters made to beat collectively. I think that if you are following in the footsteps of you tupuna you a probably going in the right direction and in the words of Jeff Evans- on the revival of traditional navigation–

“It is both a spiritual awakening and a metaphysical passage that allows you to stand with your tupuna, invoke their knowlesge and reinvigorate their feats.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

vimeo

We are like this bark cloth.

Interwoven

pulled this way and that

beaten down to expand

folded to unfold

pressed and impressed

diverse and contradicting

Puka in places

but altogether hole

Hawaiian 'ohe kapala print

on Fijian masi

by Māori girl

Layers on layers

of overlapping time space people

all accumulating here

on this piece of cloth before me

It's all soaking in

like this red earth alae to my skin

Infinite fibres

like pathways with direction

defining the undefinable

moves minds and hands

grasping

deep sleep to dream

the unimagined to imagine

the unconscious way

I look at this landscape

this landscape is us

Its all soaking in

like this red earth alae in my skin

0 notes

Photo

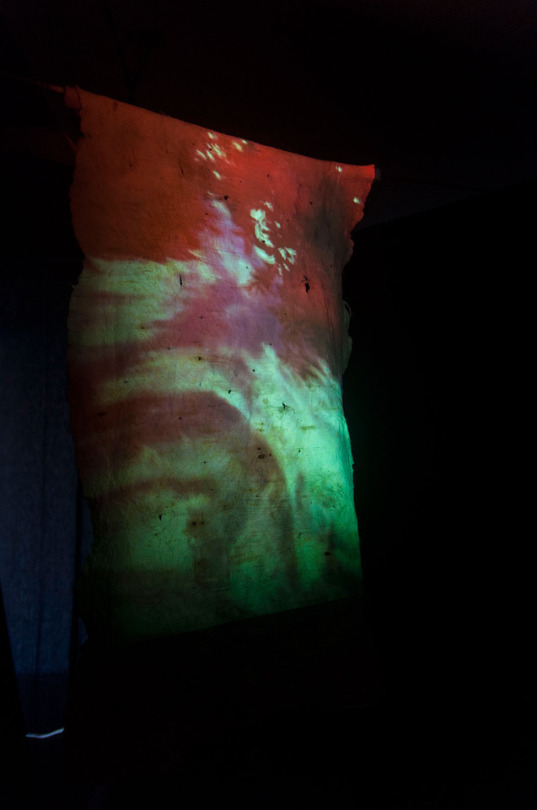

Te Wheiao

I've been dreaming of this moment for five years. • I've been dream of painting on a large piece of kapa since I first started learning. • I've been dreaming of my own exhibition with a series of kapa pieces I've beaten and marked. • Good things take time and commitment to seek out that knowledge and find your teachers. Here it is. Te Wheiao. All pieces have sold/gifted except Te Wheiao II - proceeds went towards my upcoming sail on Haunui from Norfolk back to Aotearoa.

Works List (all prices are USD)

Te Wheaio I, 2017

Kapa /Aute/Paper Mulberry, Alae/Earth from Kauaʻi, Kokowai/Burnt Earth from New Zealand, $900

Kokowai, 2018.

Digital Video, Kapa/Aute/Paper Mulberry NFS

ARORANGI (FOCUS ON THE SKY for finding diretction), 2018.

Kapa /Aute/Paper Mulberry, Alae/Earth from Kauai, Kokowai/Burnt Earth from New Zealand, $1,200

Kapa beaten by Verna Takashima and painted by Nikau Hindin

Taparau , 2017.

Kapa /Aute/Paper Mulberry, Alae/red Earth from Kauaʻi, Kokowai pango/Burnt Earth from New Zealand, $1,200

Ke Kā O Makaliʻi (The Bailer of Matariki (Pleidies)), 2018. Kapa /Aute/Paper Mulberry, Alae/Earth from Kauai, Kokowai/Burnt Earth from New Zealand, $900

Te Wheaio II, 2018. Kapa /Aute/Paper Mulberry, Alae/Earth from Kauai, Kokowai/Burnt Earth from New Zealand, $3,200

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Detail.

Nikau Hindin Te Tīpare o Hinetakurua, The Crown of the Winter Goddess. (Winter Solstice, 21.06.2020)>

2019kōkōwai (red ochre), ngārahu (soot pigment) on aute (paper mulberry)from the series Kōkōrangi ki Kōkōwai: From Celestial Bodies to the Earth

0 notes

Video

youtube

MUSEUM RESEARCH PRESENTATION

Te Uru Aute | The Aute Grove | Our Ancient Future

I had ten minutes to present my research to staff, lecturers, friends and family. I made this video and narrated it live as I stood at the podium. I really enjoyed this way of presenting because as I spoke the video brought my words to life. Here is what I said:

Kia ora whanau, he uri tenei no te hokianga whakapou karakia.

Ko Ngatokimatawhaoroa te waka,

Ko Tapuwae te awa,

Ko Ngahuia te marae,

Ko Ngaitupoto te hapuu,

Ko Ngapuhi me Te Rarawa nga iwi.

Good afternoon whanau, my name is Nikau Hindin and I whakapapa back to the Hokinaga and this is my marae over looking the Harbour.

The revival of traditional practices is a key element to my research project. The Hawaiian waka haurua Hokule’a and the subsequent revival of traditional navigation in the Pacific has been a huge influence on my way of thinking.

This is a star compass up at Hector Busby’s place in Aurere. The star compass is the Polynesian system of orientation – you can see here that the pou line up with the horizon and the spaces between them represent the 32 houses in which the stars rise and fall into.

This compass usually resides in the mind of the navigator and they use points on the waka to calibrate the star houses but when you aren’t on the water this gives students the chance to immerse themselves in the practise of celestial navigation.

An important kaupapa in this project is activating theory through practice. My Maori Studies Degree became more relevant to me when I discovered Dante Bonica’s workshop. In his classes, you come to the Auckland Museum and replicate taonga tawhito using traditional methods and tools. Neither words or pictures can do justice to the experience of making taonga the old way. Working this way gives you an intimate awareness of the material your are interacting with because the process is so slow and repetitive. I often work with wood and when you use these tools you learn about the materials weaknesses and strengths, its weight and balance, its knots and grain. From Dante’s classes I became in awe of the ingenuity and craftsmanship of our tupuna and my desire to learn more about their traditional practices grew.

One Day Dante showed me this aute plant and told me it was special because our tupuna used to grow aute.

The importance of this tit bit of information didn’t sink in till I went to the University of Hawai’ and learnt how to beat wauke into kapa and then learnt that wauke translates to aute in Māori. When Maile Andrade mentioned that Maori once beat kapa too I was surprised I knew nothing about Maori tapa cloth… and that’s when I remembered Dantes aute plant and the ability to continue to this practice in Aotearoa inspired me to begin this learning journey.

What you are seeing was my first mini wanaga where we scraped the outer bark and prepared the aute for soaking.

After the bark has been soaked it becomes soft enough to beat.

One of the aspects I loved about beating kapa in Hawaii, that hasn’t manifested here in Aotearoa- YET- was the communal nature of beating, as well the refined process that came from generations and generations of practice.

I am still a student of this practice so my project seeks to refine my own skills in making bark cloth as well as share this practice with my peers and community.

An important lesson Dante has taught me over the years of working with stone tools is that your outcome is only as good as your tools. Fortunately for me I have been able to study the Auckland Museum’s collection of Maori tapa beaters.

The quality of some of these beaters is astounding – the grooves are so fine and straight. Examining these tools gives us clues into how our tupuna once beat tapa. It also instructed the way I made my own beaters, and helped me make decisions about the width and depth of the grooves.

The idea when you are beating is that you slowly spread out the fibre. It is a bit like felting.

It is a privilege to be able to have access to the beaters here and not only replicate the tools but use them, thus replicating the physical movements of our tupuna and reawaken the sound of this process which may not have been heard by this land for hundreds of years.

The Tainui whakatauki “Te kete rukuruku a Whakaotirangi” speaks of one womens far sightedness Whakaotirangi was Hoturoa’s principle wife. The story goes that on their journey from Hawaiki, while the rest of the crew ate their kumura seed she kept hers safe by tying a firm knot in her basket that helped preserve these kakano. When they arrived in Aotearoa she planted kumara, calabash and aute all of which flourished exceedingly.

From beating aute I have learnt that there are limitations to the aute tree at Dante’s due of its age. It is almost as if the aute I am using “hasn’t been told that it is going to become bark one day- so when I process it- it must get a bit of a shock from it’s transformation.”

Simmons is important to this jigsaw puzzle because Matua Dante got his aute tree from Simmons along time ago. Dante kept telling me that these aute tree send underground roots out which means aute treese pop up a few meters away. Our aute tree at school is surrounded by concrete so this hasn’t occurred. At Simmon’s place however, there is one main aute and about nine baby ones.

Ulitmately to sustain this practice we need more aute material and we need to plant more aute. The wauke in hawaii is harvested young, with intention of being processed and beaten into cloth. When I saw these beautiful, straight young aute I knew that these plants- if pruned and looked after correctly- would produce fine aute.

Looking forward I hope to plant an aute grove that can be harvested for making Maori tapa in the future. In the mean time, I have enough bark soaking and enough beaters made to beat collectively. I think that if you are following in the footsteps of you tupuna you a probably going in the right direction and in the words of Jeff Evans- on the revival of traditional navigation–

“It is both a spiritual awakening and a metaphysical passage that allows you to stand with your tupuna, invoke their knowlesge and reinvigorate their feats.”

0 notes

Video

youtube

TE KIRI Ō TĀNE

means the skin of Tāne-mahuta, atua of the forests and birds

I made this video awhile ago with my sister for the Museum to introduce people to my Honours Project about Māori Tapa Cloth. Having prepared and soaked the aute already, my sister and I went out west and spent the day hiking, cooking and eating boil up and then we beat tapa together. I am still learning about the nuances of this process and in this video I explain a little about my reasons for looking into this practice and how important revitalising traditional practices are for Māori.

0 notes