#ogou

Note

Bonjou. What is Ogou Desalin like? Have you had any experiences with him? Apparently he is supposed to be Dessalines himself but I've heard this lwa just carries his name (you hear different things depending on who you ask).

Hi there,

Yes, some folks recognize an Ogou Dessalines, but how I have been taught and the area in Haiti I have primarily learned in does not teach that. Instead, Dessalines is an elevated and important ancestor, but not a lwa. It's possible that some folks hold an Ogou that also takes Dessalines name, but again not something from where my learning comes from.

Additionally, some folks say Ogou Panama is Dessalines, but that is again a difference of learning and belief, just like you said!

Hope this helps!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Orisha Ogun

1 note

·

View note

Text

✧❁ wallpaper 〴 mayuka ˗ˏˋ ´ˎ˗

reblog if you save ➳

༶•┈┈┈┈┈┈୨♡୧┈┈┈┈┈•༶

#wallpapers#mayuka#mayuka ogou#ogou mayuka#mayuka niziu#niziu mayuka#niziu#mayuka lockscreen#mayuka lockscreens#mayuka wallpaper#mayuka wallpapers#niziu lockscreen#niziu lockscreens#niziu wallpaper#niziu wallpapers#jpop#jpop girl group#jpop idol#jmusic#jgirls

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

NiziU

#niziu#withu#press play#heartris#yamaguchi mako#mako#hanabashi rio#rio#katsumura maya#maya#oe riku#riku#arai ayaka#ayaka#ogou mayuka#mayuka#nakabayashi rima#rima#suzuno miihi#miihi#nina hillman#makino nina#nina

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ogou Or Ogun. Spirits Of Iron In African Diaspora.

This is Papa Ogou one of many in the Ogou nation.

Ogou is a Nago spirit from the Nago Nation these spirits came to Haiti from Africa. they are strong spirits and used with the Asson or Tcha Tcha (rattle) there personality falls between Rada and Petro.

Now some might think, " Isn’t there a spirit like this in Lukumi ? ” Yes. There is, He is Ogun an Orisha. One of few Orishas who made it outside of Africa and who has some similarities with Ogou: In Haitian Vodou and Santeria and so on. They both are associated with iron and metal. Ogun is more of a blacksmith, whereas Ogou is more of a soldier.

When you hold a knife, railroad spike, sword or horseshoe in your hand and you're holding Ogun or Ogou. Ogun is also the patron of anyone who works with metal.

This spirit is great even if your practicing hoodoo because he can protect you help you even help increase your energy in your workings.

There are also many Ogous in Haiti, like Ogou Kriminel, Ogou La Flambeau, Ogou Feray, Ogou Badagris, Ogou Shango, to name a few. He is also associated with a particular region of Nigeria, and is often depicted as an older soldier there names in Cuban Santeria (La Regla Lucumi) he is known as Ogun, or Oggun; In Brazilian Candomble.

The name Ogou is not the same name like in Africa but is actually a title used to describe warriors and they also carry a machete, but some favor a sword. There colors are red and blue, but some Ogous take additional colors like green or khaki. Remember: if you can’t afford anything other color to wear, you can always use a (white scarf to salute any spirit.)

Ogoun Ferraille, aka Papa Ogou Feray in New Orleans, this warrior lwa is the primary figure of Saint James the Greater—the saint himself riding into battle on a white horse. He is sometimes also represented by Saints Andrew, Martin Caballero, some use Saint Peter and John the Baptist any many others depending on which African diasporic religion you want to practice.

He is the chief of all the warrior paths of Ogun durning the Haitian revolution which gave the colors to the Haitian flag.

Orisha Ogun

INVOKED:

Ogun or Ogou is invoked to heal diseases affecting blood, including AIDS, leukemia, and sickle-cell anemia. He is invoked for safety and success before surgery. He also heals infertility and erectile dysfunction. Request his protection from crime and criminals. He also help finds employment for devotees.

Ogou is usually syncretized to Saint James the Greater but may also can be associated with Michael Archangel and Saints Andrew, any many others depending on which African diasporic religion you want to practice.

He is a works tirelessly at the forge, in the bedroom, and on behalf of his devotees. He never rests.

He will use his machete to cut away all evil and sweep your enemies away. But he is also a tender and loving Papa. I’ve will cry when his children are in pain. Ogou also loves the ladies and he is one of the most commonly married lwa.

ATTRIBUTES: A machete, a three-legged iron cauldron, traditionally wrapped in chains and filled with iron implements, including tools, spikes, nails, and knives👇

SPIRIT COLOURS: Red, black, sometimes green, sometimes red and white (the colors of heated iron), or blue and red (the colors of the Haitian flag) or Green and black for Ogun. But can always wear white if you don't have the other colors.

OFFERINGS: Red candles, cigars, rum, whisky, aguardiente, or other alcoholic beverage— incense, metal, chains, metal tools, railroad spikes. He likes red beans and rice, and typically likes Florida water as a cologne.

Fill a cauldron with found pieces of metal, like rails or railroad spike (not plastic).

He will often blow cigar smoke on people to give them blessings.

He like fire we make a fire for him sometimes on the veve.

So whichever one you're drawn to like Haitian or African spirits, there's no spirit better to have for protecting than Ogun. Except, St. Michael or God of course 😃

Everyone needs a warrior. Ogun is his name among the Yoruba people. Among the Fon he is called Gu. In Cuban Santeria (La Regla Lucumi) he is known as Ogun, or Oggun; In Brazilian Candomble , Ogum; in Haiti’s Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo Papa Ogou, or simply Ogou.

Feast Day: He is syncretized with St. Peter whose feast day is June 29, St. James whose feast is July 25th, and St. Michael whose feast is Sept. 29th.

#Haitian Vodou Lwa#African spirit Ogun#Law Ogou#Spirits#Haitian Vodou#New Orleans Voodoo#Lwa & Saint connection#spiritual#google search#rootwork#Southern voodoo#like and/or reblog!#follow my blog#Google search

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayuka

#Mayuka#まゆか#マユカ#마유카#Ogou Mayuka#おごうまゆか#小合麻由佳#Lead Rapper#niziu_info_official#niziu_artist_official#NiziU#虹U#ニジユ#니쥬#ニジュー

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ogou mayuka, mayuka (idol, niziu), japanese, 2003

(( galerie ))

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Does the Witch Doctor in Africa countries make Kabbalistic Pacts with the Devil like in Haitian Voodoo and Jamaican Obeah?

They most certainly do not make Kabbalistic Pacts with the Devil which is a Judeo Christian Islamic concept, which they were not, African priest and priestess doubled as healers both spiritual and physical , they understand there is a duality in nature as in the spiritual worlds one can tap into , eg Horus cannot exist without his polar opposite Set.

Now that said there are areas where both the Christian concepts became entwined with African religious concepts as in the cross roads and Papa Legba.

Because slave owners were worried about potential rebellion, they often separated enslaved people from the same area.

By mixing people from different regions and language groups, they could use the communication barrier to discourage or even prevent revolt. However, many of the deities were similar, and so enslaved people from different parts of Africa soon found commonalities in their spiritual beliefs and practices, which they were forced to keep hidden.

Papa Legba soon found a home in the religious structures of enslaved people in Haiti and the Caribbean, as well as in the American colonies. Author Denise Alvarado says Legba:

...stands at a spiritual crossroads and grants or denies permission to speak with the spirits of Guinee, and is believed to speak all human languages. He is always the first, and the last spirit invoked in any ceremony because his permission is needed for any communication between mortals and the loa—he opens and closes the doorway to the spirit world.

Over time, after African syncretic practices blended with Catholicism in the new world, Legba became associated with several saints, including Saint Peter, Saint Anthony, and Saint Lazarus.

In the Haitian religion of Vodou, Legba is seen as the intermediary between mortal men and the loa, or lwa. The loa are a group of spirits responsible for various aspects of daily life, and they are the children of a supreme creator, Bondye. They are divided into families, such as the Ghede and Ogou, and practitioners develop relationships with them through offerings, petitions, and prayers. Often, Papa Legba is the one who carries these prayers to the loa.

Note the cross roads would later become associated with the devil in this religious synchronism.

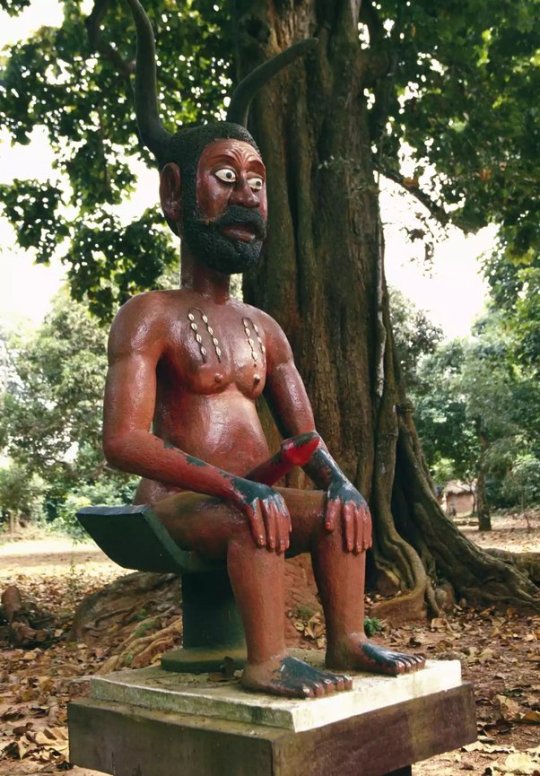

Statue of Legba as fertility god. Atlantide Phototravel / Getty Images Plus

Legba has evolved in numerous ways from his origins in Africa, where he is sometimes viewed as a fertility god or a trickster; he many be depicted as both male and female, sometimes with a large erect phallus. In other areas, he is a protector of children or a healer, and can grant forgiveness for crimes against others. Variants of Legba exist in many places including Brazil, Trinidad, and Cuba.

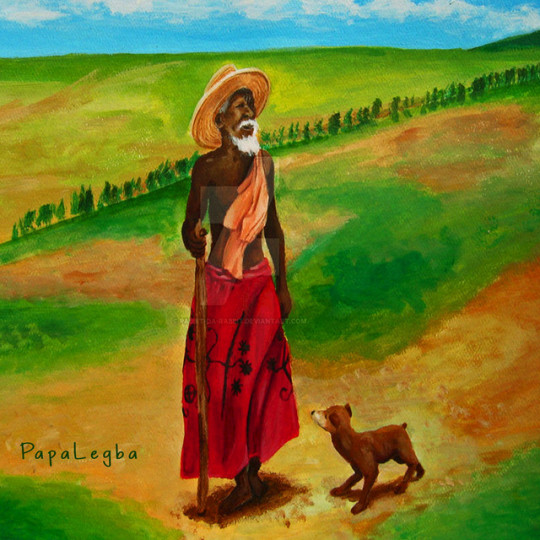

Papa Legba appears in many forms in New Orleans Voodoo and Haitian Vodou. He is typically depicted as an older man, sometimes wearing a straw hat or old tattered clothing, walking with a cane, and accompanied by a dog. He's associated with the colors black and red.

Legba is strongly associated with crossroads magic, and is referenced in a number of early twentieth-century blues tunes from the area of the Mississippi Delta. Famed bluesman Robert Johnson is said to have met a spirit at the crossroads, and offered him his soul in exchange for musical success. Although eventually the story was twisted to say Johnson met the Devil, musical folklorists believe that tale is rooted in racist ideology; instead, Johnson met Legba at the crossroads, where he had gone seeking guidance and wisdom.

Papa Legba is a master communicator, who is said to speak the languages of all human beings; he then translates petitions and delivers them to the loa. He is a teacher and warrior, but also a trickster deity. Legba is a remover of obstacles, and can be consulted to help find new, positive opportunities, thanks to his ability to open doors and new roads

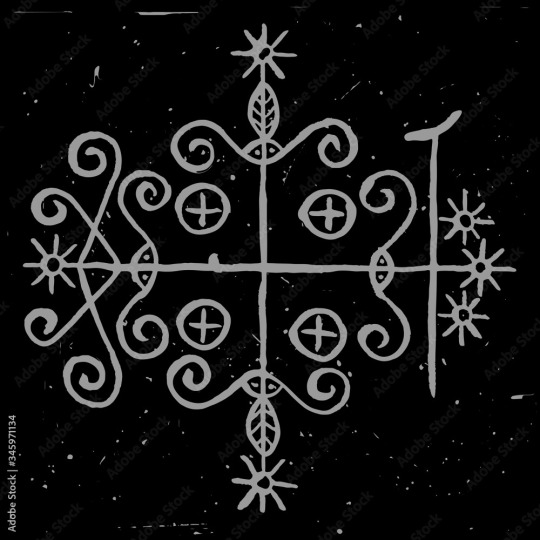

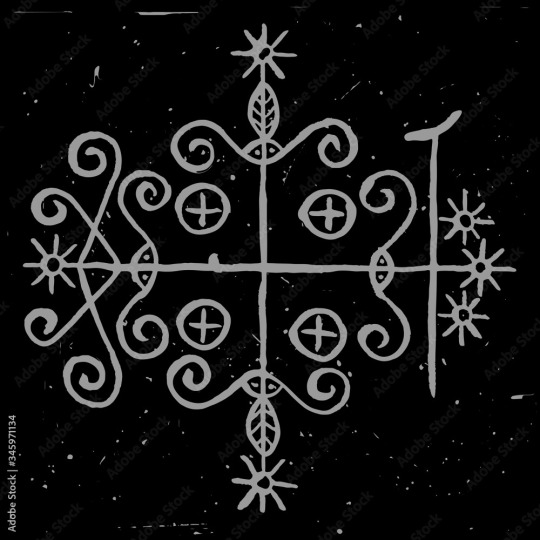

Legba represents a West African and Caribbean Voodoo god. This god has many different names depending on the region in which he is worshipped is most commonly known in Haiti as Papa Legba. Papa Legba serves as the guardian of the Poto Mitan--the center of power and support in the home. Additionally, he allows for communication between humans and the spirit world. According to West African Voodoo practices, spirits of the dead are not able to inhabit one's body unless permitted by Papa Legba. The symbol for Legba typically has a red background, one of his representative colors. The symbol includes several keys which signify Legba's control over communications and forms of passage, including locks, gates, and passageways;it also includes a cane, as Papa Legba is generally depicted as an old and feeble man in the Haitian religion. There are many chants to summon Papa Legba, one of which is: Papa Legba, Open the gate for me/Atibon Legba, Open the gate for me/Open the gate for me/Papa that I may pass/When I return I will thank the Lwa.

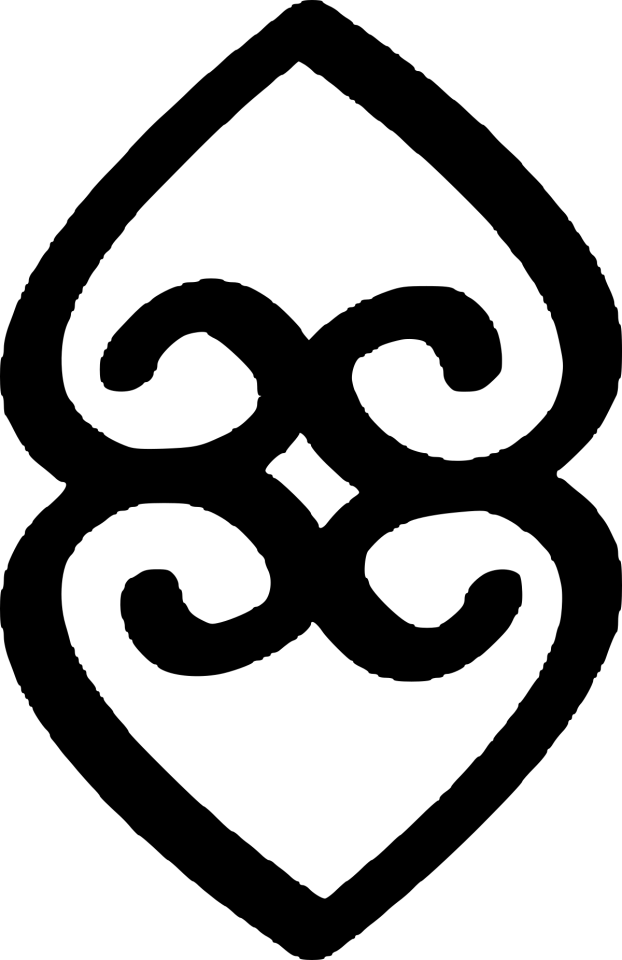

GYE NYAME - Supremacy of God

Gye Nyame, meaning “except for God,” symbolizes God’s omnipotence through the knowledge that people should not fear anything except for God. Another interpretation of “except for God” is that no one has seen the beginning of all creations, nor will anyone live to see the end, except for God. Gye Nyame indicates the recognition of the supremacy of God over all beings, and therefore is the one that is feared and revered by all. This is one of the many Adinkra symbols of West Africa, Ghana, and is used by the Akan people in various decorations, clothing, and artwork. Some say that the symbol represents a spiral galaxy, or two hands with different gestures that refer to God being supreme to the simplistic ideals of male and female identifications that are used today. The use of this symbol by the Akan people suggests that the Akan had a highly advanced writing language that transmitted religious and cultural concepts, and also might have had a somewhat extensive knowledge of astronomy, which shows their intellect and indicates that the Akan were a more advanced civilization.

Nkisi Sarabanda, symbolizing the signature of the spirit, is a representation of a bakongo cosmogram. This symbol portrays how the Congo-angolan people viewed the interaction between the spiritual and material world, or in other words between the living and the dead;the Congo-angolan people believe that these worlds are inherently intertwined. An Nkisi is a spiritual object used for worship purposes, and have been found in places where enslaved Africans have lived in, such as in the plantation homes. Nkisis show the development of African American culture in how they are essentially African objects, but are constructed through American materials. This also reveals an aspect of the melting pot of African and American culture. Sarabanda just connotes "the highest spirit". Part of the symbol takes the form of a cross, because the Congolese had an inclination towards Christianity. Communication appears to take place at the center of the cross, where the worlds intersect, and it was believed that spirits sat at the center of the sign. The arrows represent the four winds of the universe, and the symbol as a whole resembles the form of a spiral galaxy;this indicates their interest in astronomy and affinity towards nature.

Nsoromma, meaning "children of the heavens" or "star," symbolizes the guardianship of God and how he watches over all beings. It is one of the many Adinkra symbols that the Ghanaian people have lived by. The protection of God is constant, like the stars in the universe. The stars also embody light, with the vision of light slicing through darkness as a savior, or protector. The symbol indicates the existence of the spiritual world, in which our ancestors and past families exist and watch over us, creating a feeling of safety and wholeness. Nsoromma expresses the message to live life to its fullest knowing that you are supported and strengthened by God.

Divinity of Mother Earth

Asase Ye Duru—literally meaning “the earth has no weight”—is a symbol that represents power, providence and divinity. The symbol is one of many adinkras, or depictions of important concepts created by the Akan peoples of Ghana. Asase Ye Duru emphasizes the importance of the Earth and its preservation. People must respect and nurture the Earth, and should never act in ways that might directly or indirectly harm the Earth. The significance of the Earth to the people of Ghana is evident in the following proverbs: Tumi nyina ne asase, meaning All power emanates from the earth; and Asase ye duru sen epo, meaning The earth is heavier than the sea. The African Burial Ground honors these principles, as it surrounds itself with natural resources and emphasizes the cohesion of death and nature.

#vodun#african traditional religions#panafrican thought#kemetic dreams#asase#duru#akan#earth#ghana#nso#nsoromma#children of the heavens#nkisi#nkisi sarabanda#bakongo#bakongo symbolism#gye#gye nyame#legba#new orleans voodoo#haitian vodou#brazil#trinidad#cuba#denise alvarado#obeah#kabbalistic#odinani#horus#set

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy day-after-Wednesday!

youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hector Hyppolite (Haitian, Saint-Marc 1894–1948 Port-au-Prince) Ogou Feray, also known as Ogoun Ferraille, ca. 1945

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, 1981

#jean michel basquiat#Hector Hyppolite#hatian artist#hatian painter#surrealism#surrealist#lettrism#lettrist#black artists#black painters#aesthetic#modern art#art history#tumblr art#beauty#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblraesthetic#aesthetictumblr

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

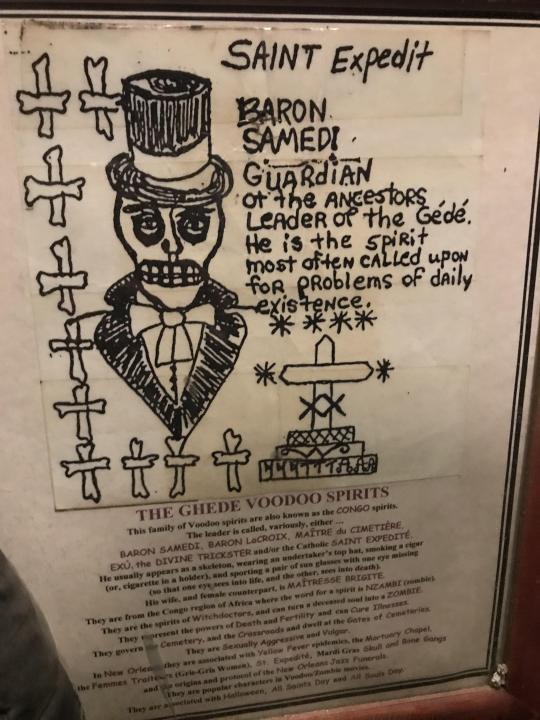

RE: Was Baron Samedi worshiped in New Orleans prior to the late 20th century?

This one is also about the actual lwa.

Baron Samedi can aptly be described as not just the most iconic lwa, but one of the most iconic things from New Orleans Voodoo. Ironically, I have only found inconclusive evidence that he was worshiped in New Orleans during the 19th or early 20th centuries.

In American popular media, Baron Samedi is frequently conflated with other Haitian deities, called the Gede. The real-life Baron Samedi has his origins in Haitian Vodou, as does Maman Brigitte (Gran Brijit). The Haitian lwa are derived from African deities, among the most important being the Dahomean trickster god Legba (himself, derived from the Yoruba deity Eshu). Over the course of Haitian history, Dahomean Legba was refracted into Papa Legba, Met Kalfou, and the Gede - by extension, the Bawons, including Baron Samedi. This explains why the Gede are trickster deities of sexuality and liminality, who embrace all that is taboo - just like Dahomean Legba!

19th Century New Orleans Voodoo was greatly influenced by Haitian Vodou, due to the massive influx of Haitian refugees that arrived in the Crescent City after the Haitian Revolution. Following the post-Revolution migration wave, several Haitian lwa became features of New Orleans Voodoo, including:

Papa Legba → “Papa Limba” or “La Bas”, syncretized with St. Peter

Damballah → “Daniel Blanc”, syncretized with St. Michael

Agassu → “Yon Sue”, syncretized with St. Anthony

Ogou Feray could have also been worshiped as “Joe Ferraille” (“Joe Feray”), and Ayizan Velekete as “Vériquité”. While the Erzulies were not directly worshiped per se, veneration of Mother Mary was a key feature of 19th century New Orleans Voodoo. (The Erzulies are syncretized with Mother Mary.)

(I should also note that, in New Orleans, the lwa were called “spirits”, while Bon Dieu/Bondye was simply called “God”)

During the 19th century, the two most important lwa were probably Papa Legba - the Doorkeeper - and Damballah - the most ancient of the lwa. This would explain why their names appear most frequently in 19th- and 20th-century sources, especially in large scale rituals. Damballah might have been refracted into multiple deities, including “Daniel Blanc” and “Zombi the Snake God” – a deity famously associated with Marie Laveau. Others argue that “Grand Zombi” is actually derived from the Kongo supreme deity Nzambi Mpungu, or an invention fabricated by journalists.

A third key deity – “Onzancaire” / “Monsieur Assonquer” – might have been associated with Ogou Feray – one of the most important Haitian lwa. However, the origins of “Onzancaire” are elusive. Because so many different theories have been proposed, I do not know where his true origins lie.

Other deities of non-Haitian origin were also features of New Orleans Voodoo. St. Marron (Jean St. Malo) was the New Orleanian folk saint of runaway slaves. Mother Leafy Anderson – founder of the Spiritual Church Movement in New Orleans – introduced worship of the Native American Saint Black Hawk (see: Kodi A. Roberts (2015) Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans, 1881–1940). My understanding is that “Dr. John” (Jean Montaigne) was also deified, in a similar manner to St. Black Hawk. Orisha, such as Shango and Oya, may too have been worshiped. Other deities are listed here and here.

Baron Samedi is conspicuously absent. I think this has to do with the history of Haitian Vodou. Prior to the Haitian Revolution, Haitian Vodou was less of an organized religion, described as a "widely-scattered series of local cults" (see: The Social History of Haitian Vodou, p. 134). It was between the years 1804 and 1860 that Haitian Vodou began to stabilize into a clear predecessor of its present form. (see: The Social History of Haitian Vodou, p. 139) This period of stabilization took place after the migration wave of the early 19th century, which could explain why key features of Haitian Vodou are missing from 19th century New Orleans. For example, I have yet to find evidence that division of the Petwo and Rada lwa made it over to American soil. The refraction of Dahomean Legba might have never been transmitted by Haitian refugees, which would explain the absence of Met Kalfou and the Gede/Bawons from worship.

This too explains why the Papa Legba of American history was both Doorkeeper AND Guardian of the Crossroads. It has been theorized that the legendary “Devil at the Crossroads” was actually Met Kalfou. However, this “Devil” does not match the appearance of Kalfou, described as "no ancient, feeble man...huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life." Instead, the one at “the Crossroads” appears as a limping old man who loves music and dogs (“Hellhound on my Trail”). It’s Papa Legba!

Rather than Kalfou, I think American Papa Legba actually inherits his more menacing attributes from Eshu. This would explain why he walks with a limp (like Eshu), is notoriously vengeful (like Eshu), and is sometimes described as androgynous (like Eshu!).

In any case, the Papa Legba of American history can be clearly traced back to Haiti. His appearance as a limping old man is inherited from Haitian Papa Legba; his love of dogs and music from Dahomean Legba. 19th century sources clearly identify him with Saint Peter (“St. Peter, St. Peter, open the door;”) The same cannot be said for Baron Samedi. He was probably not syncretized with St. Expedite, because St. Expedite “did not achieve popularity until the late 1800s or early 1900s in New Orleans” – long after the Haitian migration wave.

I have found one compelling source that places worship of Baron Samedi in 19th century New Orleans. Creole author Denise Alvarado is something of an expert on this topic, her being born and raised in New Orleans. In Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans (2022), Denise Alvarado identifies a “Spirit of Death” with Baron Samedi / Papa Gede. The most convincing piece of evidence comes from the second interview, in which the interviewee describes a ceremony where attendees donned purple robes. The color purple has been historically associated with Papa Gede (by extension, Baron Samedi).

That being said, I do think the evidence Alvarado provides is tenuous. Without additional context, it’s difficult to say whether the purple robes are truly linked to the Haitian lwa. The other newspaper article sounds rather sensationalized. The 19th century saw horrendous news coverage of New Orleans Voodoo, where reporters would exaggerate or straight-up fabricate details to demonize Vodouisants. The reporter’s description of the spirits of death does not align with the Haitian Gede or Bawons. It is important to remember that New Orleans Voodoo is not entirely Haitian in origin. Several other traditional African spiritualities are woven into New Orleans Voodoo. Prior to the Haitian migration wave of the early 19th century, one of the main influences was Kongo spirituality, in which ancestor veneration is central. Additionally, the newspaper cited is from the year 1890 – years after Marie Laveau’s death. The reliability of this article is therefore questionable. I think this could be a Damballah / “Grand Zombi” situation, where this “Spirit of Death” bears superficial resemblance to the lwa but isn’t actually him. It is also possible that he is simply a fabrication by journalists.

The defamation of Vodou continued into the early 20th century, as Haiti was occupied by the U.S. between the years 1915 and 1934. I don’t see how worship of the Gede/Bawons could have been transmitted to New Orleans between the end of the Haitian migration wave and year 1934. There’s a good chance that Baron Samedi / Papa Gede only properly became features of New Orleans Vodou during the revitalization movement of the late 20th century.

As such, I propose two hypotheses:

Baron Samedi was not properly worshiped in New Orleans until the late 20th century. He quickly rose in popularity, as he was easily grafted onto the pre-existing worship of the spirits of the dead (ancestors).

Alvarado has correctly identified Baron Samedi / Papa Gede with the “Spirit of Death”; however, this “Spirit of Death” was a radical departure from his Haitian predecessor, taking on a markedly different form from the lwa.

But that’s all just a Theory… A GAME THEORY!!!

…Anyways, annotated bib:

Marshall, Emily Zobel. American Trickster: Trauma, Tradition and Brer Rabbit. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Chapter 1 ("African Trickster in the Americas") describes Dahomean Legba’s origins in the Yoruba deity Eshu.

Cosentino, Donald. "Who is that fellow in the many-colored cap? Transformations of Eshu in old and new world mythologies." Journal of American Folklore (1987): 261-275. https://www.jstor.org/stable/540323.

From the abstract: “Myths of Eshu Elegba, the trickster deity of the Yoruba of Nigeria, have been borrowed by the Fon of Dahomey and later transported to Haiti, where they were personified by the Vodoun in the loa Papa Legba. In turn, this loa was refracted into the corollary figures of Carrefour and Ghede.” Accessed here: https://www.centroafrobogota.com/attachments/article/24/17106647-Ellegua-Eshu-New-World-Old-World.pdf

Haitian immigration : Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. The African American Migration Experience. https://www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm@migration=5.htm

Describes post-Haitian Revolution migration wave like so: “the number of immigrants [from Haiti to New Orleans] skyrocketed between May 1809 and June 1810… The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites, 3,102 free persons of African descent, and 3,226 enslaved refugees to the city, doubling its population.”

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Mentions worship of Ogou Feray as “Joe Ferraille”. Fandirch herself cites Long, C. M. (2001). Spiritual merchants. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, p. 56: https://archive.org/details/spiritualmerchan0000long/page/56/mode/2up?

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 247: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT247#v=onepage&q&f=false

Mentions worship of Ayizan Velekete as (the male) “Vériquité”.

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Hoodoo, voodoo, and conjure: A handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008, p. 15: https://books.google.com/books?id=TH7DEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: "Blanc Dani, Papa Lébat, and Assonquer make the most frequent appearances in both nineteenth- and twentieth-century sources. The first two, in particular, figure prominently in large-scale rituals."

Humpálová, Denisa. "Voodoo in Louisiana." (2012). https://dspace5.zcu.cz/bitstream/11025/5338/1/BP%20Denisa%20Humpalova%202012.pdf

One of several sources that identifies “Grand Zombi” with Nzambi Mpungu.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 247: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT247#v=onepage&q&f=false

Posits that “Grand Zombi” could be derived from Nzambi Mpungu, or "may be the invention of journalists inspired by "zombie tales" of Haiti's infamous living dead, combined with Moreau de Saint-Méry’s endlessly repeated description of a snake-worshiping ceremony in colonial Saint Domingue."

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Voodoo: An African American Religion. LSU Press, 2024, p. 46: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Voodoo/O-v3EAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22assonquer%22+%22azewe%22+vodou&pg=PA46&printsec=frontcover

Describes several possible origins for the elusive “Onzancaire”, including a theory that he was a deity related to Ogou Feray.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 236: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT236#v=onepage&q&f=false

One of several sources to describe St. Marron (Jean St. Malo).

Roberts, Kodi A. Voodoo and Power: The Politics of Religion in New Orleans, 1881-1940. LSU Press, 2015, p. 82: https://books.google.com/books?id=EWOkCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT82&lpg=PT82

Describes how Mother Leafy Anderson (founder of the Spiritual Church Movement) “found” St. Black Hawk, introducing him to New Orleans Voodoo.

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, p. 39: https://books.google.com/books?id=ktlWEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39#v=onepage&q&f=false

Posits that high priestess Betsy Toledano worshiped the Orisha Shango and Oya during the 19th century.

Anderson, Jeffrey E. Hoodoo, voodoo, and conjure: A handbook. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2008, p. 15: https://books.google.com/books?id=TH7DEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15#v=onepage&q&f=false

List of deities worshiped in 19th century New Orleans Voodoo.

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, p. 126: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Witch_Queens_Voodoo_Spirits_and_Hoodoo_S/ktlWEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA126

Another list of deities worshiped in 19th century New Orleans Voodoo.

Mintz, Sidney & Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995) “The social history of Haitian Vodou” in Cosentino, Donald J., ed., Sacred Arts of Vodou, Chapter 4. LA: UCLA Fowler Museum, 123-47. P. 134: https://ghettobiennale.org/files/Trouillot_Mintz_LOW.pdf

Describes Haitian Vodou as a "widely-scattered series of local cults" prior to the Haitian Revolution.

Mintz, Sidney & Trouillot, Michel-Rolph (1995) “The social history of Haitian Vodou” in Cosentino, Donald J., ed., Sacred Arts of Vodou, Chapter 4. LA: UCLA Fowler Museum, 123-47. P. 139: https://ghettobiennale.org/files/Trouillot_Mintz_LOW.pdf

Describes the stabilization of Haitian Vodou into a predecessor of its current form. This occurred between the years following the Haitian Revolution and year 1860.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 101: https://archive.org/details/divinehorsemenli00dere/page/100/mode/2up

Description of Kalfou (Carrefour) as "no ancient, feeble man...huge and straight and vigorous, a man in the prime of his life." Deren conducted her ethnographic work during the 1940s and 1950s.

Marvin, Thomas F. “Children of Legba: Musicians at the Crossroads in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.” American Literature, vol. 68, no. 3, 1996, pp. 587–608. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2928245. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Description of “The Devil at the Crossroads” as a musical genius and “limping old black man”: “Most versions of this story instruct the aspiring musician to bring his instrument to a lonely crossroads at midnight and await the arrival of a limping old black man who will tune the instrument, play it briefly, and then return it endowed with supernatural power."

Robert Johnson’s song “Hellhound on My Trail” identifies “The Devil at the Crossroads” with Papa Legba, who is associated with dogs.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 244: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT244&lpg=PT244#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: "Mary Washington, born in 1863, said she was trained in the arts of Voudou by Marie Laveau. She remembered a song that was sung at the weekly ceremonies: "St. Peter, St. Peter open the door; I am callin' you, come to me; St. Peter, St. Peter open the door." Mrs. Washington explained that "St. Peter was called La Bas, St. Michael was Daniel Blanc, and Yon Sue was St. Anthony." She also mentioned a spirit called Onzancaire."

Alvarado, Denise. The Magic of Marie Laveau: Embracing the Spiritual Legacy of the Voodoo Queen of New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2020, p. 57: https://books.google.com/books?id=SZOMDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57#v=onepage&q&f=false

Relevant quote: “Baron Samedi remains a popular and powerful force in New Orleans Voudou today, along with his wife Manman Brigit. He is syncretized with St. Expedite, among the most popular of saints in New Orleans. We do not hear of St. Expedite in association with Marie Laveau, however, because he did not achieve popularity until the late 1800s or early 1900s in New Orleans (Alvarado 2014).”

Alvarado, Denise. Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans. Weiser Books, 2022, pp. 127-128: https://books.google.com/books?id=GsofEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA127&lpg=PA127#v=onepage&q&f=false

This is the strongest evidence I could find that Baron Samedi / Papa Gede was worshiped in 19th - early 20th Century New Orleans.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen : The Living Gods of Haiti. New Paltz, NY: McPherson, 1983 (originally published in 1953), p. 107: https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.505921/page/107/mode/2up?q=purple

Historical evidence that, since at least the 1940s, Papa Gede’s colors are “black or purple”. To this day, purple is associated with Baron Samedi and the Gede as a whole.

Long, Carolyn Morrow. A New Orleans voudou priestess: The legend and reality of Marie Laveau. University Press of Florida, 2007, p. 250: https://books.google.com/books?id=_XzSEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT250&lpg=PT250

Relevant quote: “The religion that evolved in nineteenth-century New Orleans and was embraced by Marie Laveau and her Voudou society combined traditions introduced by the first Senegambian, Fon, Yoruba, and Kongo slaves with Haitian Vodou, European magic, and folk Catholicism. It also absorbed the beliefs of blacks imported from Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas during the slave trade of the 1830s–1850s. These “American Negroes” were English-speaking, at least nominally Protestant, and practiced a heavily Kongo-influenced kind of hoodoo, conjure, or rootwork. New Orleans Voudou is therefore not identical to Haitian Vodou, but represents a unique North American blend of African and European religious and magical Traditions.”

Fandrich, Ina J. “Yorùbá Influences on Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.” Journal of Black Studies, vol. 37, no. 5, 2007, pp. 775–91. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034365. Accessed 23 June 2024.

Describes major Senegambian and Kongo influences on New Orleans Voodoo, prior to the Haitian Revolution. Relevant quote: “New Orleans's African population was Kongo dominated with a strong affinity with the spirits of the dead…Dahomeyan influence occurred only indirectly through the Haitian refugees who "flooded" the city after 1808. In 1809 alone, more than 10,000 Haitians arrived, and doubled the city's population. They brought their Vodou religion with them, which ultimately merged with the already existing New Orleans or Louisiana Voodoo traditions. During the French colonial regime, 80% of the enslaved Africans came from one single ethnic group: the Bamana (also called Bambara) people from the Senegal River basin (today's Senegal, Gambia, and Mali), most of them stemming from one single ethnic group, the Bambara people. The majority of the remaining 20% were Kongolese and some Dahomeyans (Hall, 1992). Despite their rather different geographical origins, these two cultures blend easily into one another. Eighteenth-century Louisiana Voodoo maintained a marked Senegambian flavor, with some Kongolese elements blended in, until the end of the 18th century.”

Dubois, Laurent. “Vodou and History.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 43, no. 1, 2001, pp. 92–100. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2696623. Accessed 23 June 2024.

An overview of the history of Haitian Vodou, as it pertains to U.S. history. Demonization of Vodou continued past the U.S. occupation of Haiti, until the late 20th century.

#between the two it is 100% papa legba who had a bigger impact on horror stories from the american south of the early 20th century#i think a lot of people would think it's baron samedi but no! it's the mischevious limping old man!#commentary#the loa (hazbin hotel)#baron samedi (hazbin hotel)#big papa legba

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

NiziU

#niziu#withu#press play#heartris#yamaguchi mako#mako#hanabashi rio#rio#katsumura maya#maya#oe riku#riku#arai ayaka#ayaka#ogou mayuka#mayuka#nakabayashi rima#rima#suzuno miihi#miihi#nina hillman#nakino nina#nina

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

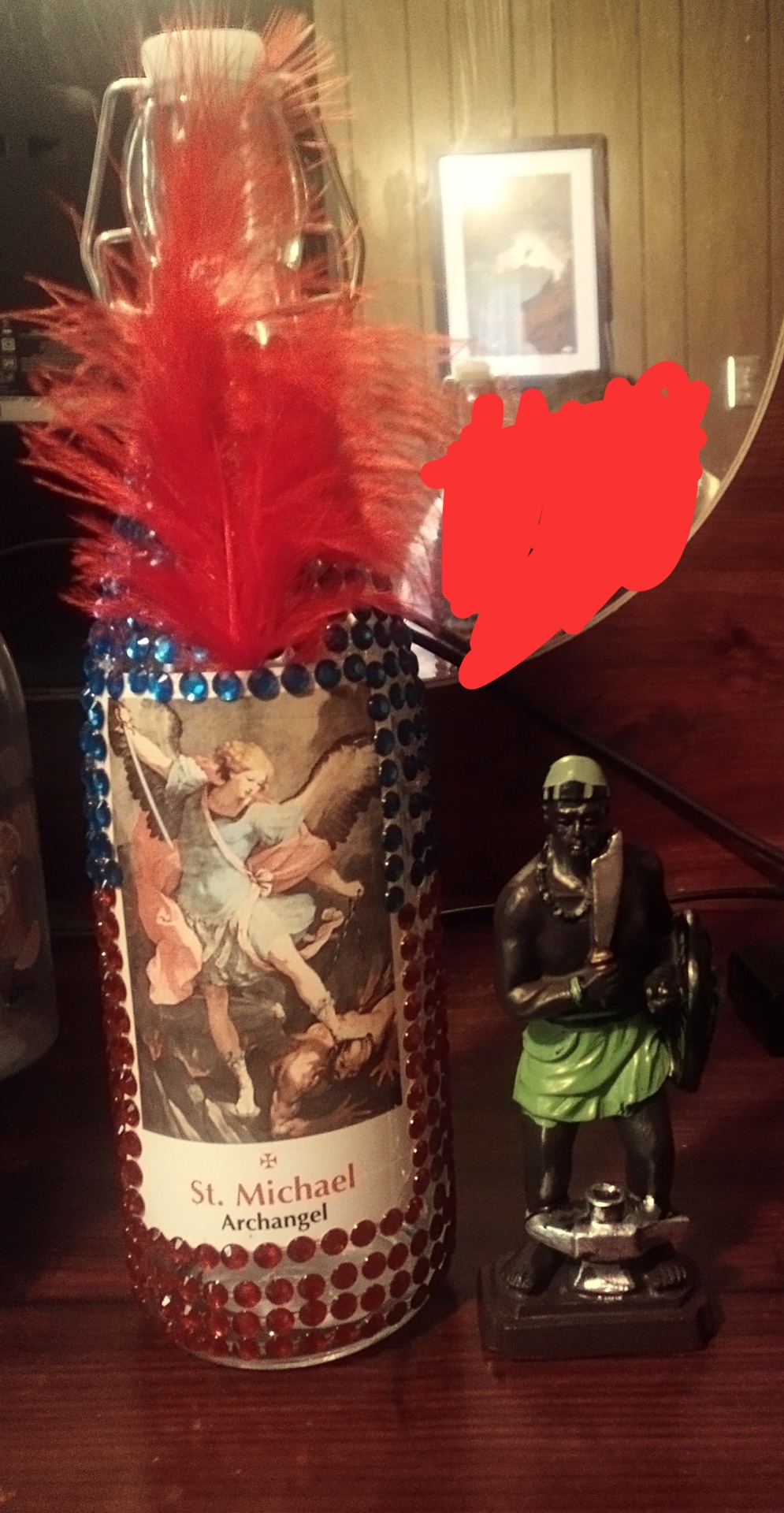

Pics From New Orleans Voodoo House's & Shops.

Hey guys I went back home to check out some voodoo / hoodoo altars and to get some ideas for myself, I even ended up making a spirit bottle for my self enjoy.

(left) A bottle I made of St. Michael aka Papa Ogou wit Ogun Statue. (Right) Other spirit bottles.

Papa Legba altar. ☝️

Ogou/ Ogun altars.

La Syrenn altar (below) & Yemaya Orisha altar (above)

Muilty purpose New Orleans voodoo altar (left) Gede Painting (right)

Pics I took of a Gede altar

More pics I took of the Gede altar wit Papa Gede & Gran Brigitte.

Another Gede altar pic I took (left)

#Voodoo altars#New Orleans voodoo#spiritual#google search#like and/or reblog!#traditional hoodoo#southern hoodoo#Gede spirits#Legba altar#Elegba Altar#La Syrenn alter#Yemaya Altar#Ogou altar#Ogun altar#Spirit bottles#Vodou#follow my blog#ask questions please!#southern voodoo#Voodoo Societies#Spiritual altars

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Annual pilgrimage dedicated to Ogou Feray in Plaine-du-Nord, Haiti

July 1994, ph. Jean-Claude Cautausse

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Via vodou.renaissance

Ogou is will-power which expresses the pure energy of the life force. Will-power is that psychological function closest to the core of any human being, the Self, and an act of will is the purest act of the Self. Those who walk with Ogou are most strongly identified with their highest Self when they are healthy, and with their Ego when they are unhealthy.

The whole escort of Ogou are Lwa of pure affirmation. Of all the Lwa, they most successfully convey the energy of... Subscribe to Vodou Renaissance Instagram to read the rest of this caption.

We will continue to explore those powers in the way they are embodied in our personalities in future posts.

Below is a list of Powers of Ogou that we will explore:

* Strength of will

* Dynamic power

* Power to synthesize

* Strong sense of purpose

* Power of beneficent destruction

* Strong one-pointed focus

* Power to preserve values

* Power to lead

* Power to direct

* Power to govern

* Fearlessness

* Power to initiate

* Detachment, or the power to detach

* Wisdom to establish, uphold or enforce the law

* Strength and courage

* Independence

* Power to liberate

* Keen understanding of principles and priorities

* Truthfulness arising from absolute fearlessness

* Power to centralize

* Large-mindedness

#Vodou #Voodoo #HaitianVodou #HaitianVoodoo #Hoodoo #AfricanSpirituality #BlackSpirituality #Haiti #HaitiCherie

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

OGUN: THE GOD OF WAR

In Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo, Ogun is a warrior orisha associated with blacksmithing and the creation of iron tools and weapons. Called Ogou in Haiti, he is in charge of guarding sacred temples and political power and is known for his protection of Vodou followers.

HISTORY AND ORIGINS

Like many of the orisha and loa, Ogun has his origins in Africa. In the Yoruba belief system, he was…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes