#or how the nobility and the aristocracy would have treated the poor

Note

How realistic is it for someone to survive getting jumped with sticks, and surviving with a finger fracture, that is later treated with surgery. What sequence of events would allow this to happen ? Setting is XVIIIth century France, and the character's hair is long, thick, curled and pomaded and powdered, which means his skull would get some cushioning.

So, this a whole set of different components, and taken together there are some issues.

The two most unrealistic details are probably surviving surgery, and their wig remaining on their head through the attack.

It's pretty reasonable for someone to survive getting jumped by attackers armed with sticks. There's a lot of ways this can go, and it's not a good situation to be in, but this isn't certain death unless the attackers really know how to get the most out of their weapons.

Even if the fight goes badly, if they survive without serious internal injuries, they could probably recover.

I'll admit that I have a modern bias, but surgery in the 1700s was a horror show. A large part of this was because of bacterial contamination wasn't understood until the the mid-19th century. Even while observing the best practices of the time, minor surgery, such as repairing a fractured finger were significantly more dangerous. In fact, with this scenario, it's quite plausible that they'd simply end up with a permanently mangled finger after the attack. If they did seek surgical assistance, there would be a very real risk of bacterial infection and death.

That leaves us with the hair or wig. The eighteenth century is near the end of the peruke (the powdered wig) as a fashion accessory in French culture. Popular culture (especially films) tend to dramatically over-represent the peruke and its ubiquity. These could be quite expensive and fragile. While some have survived, they are quite difficult to preserve. These were most often seen among the nobility, and courtiers, later filtering down into the merchant class. These wigs were not something that everyone wore. More than, the tradition of the powdered wig in France effectively died as a result of the French Revolution, because it was heavily associated with the aristocracy.

The peruke was easy to dislodge during strenuous physical activity. So, if your character was actually wearing a wig, then that would probably be lost (and potentially damaged) during the scuffle. Your character may be able to retrieve it after the fight if their attackers leave them there. For what it's worth, I think this is a good detail to be aware of and consider, just for the verisimilitude of your fight scenes. Lose articles of clothes or other carried items might be lost or damaged during combat, and it can help ground the fight as an actual event in your story rather than a disconnected interlude.

There was a practice of wearing powder directly in one's hair rather than on the wig. Again, in France, this was tied to the aristocracy, and the practice died with the French Revolution. In England it went out of fashion with the 1795 Guinea tax on hair powder, and by that point powdered hair had connotations of callous wealth.

All of that said, I don't see a powdered wig, or powered hair, offering much protection from blunt force trauma. As anyone who has ever run their head into a solid object can attest, your hair makes for poor armor. It's great as thermal protection, and this was also true of the peruke, but it's not going to save you from a club to the head.

So, how realistic is it? That's really hard to say. There's some parts of this that aren't at issue, and others that are a little questionable. Could it happen? Sure. Can you get away with writing it? That depends on how well you can sell the chain of events. Ultimately, the realism will depend on how believable you can make the chain of events.

-Starke

This blog is supported through Patreon. Patrons get access to new posts three days early, and direct access to us through Discord. If you're already a Patron, thank you. If you’d like to support us, please consider becoming a Patron.

#howtofightwrite#Starke answers#writing advice#writing reference#writing tips#Starke is not a real doctor

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

People- YuuMori exaggerates how evil the nobility and upper class is.

(Ignoring the fact that it presents some nobles as decent people while focussing on the one's that aren't)

Me-

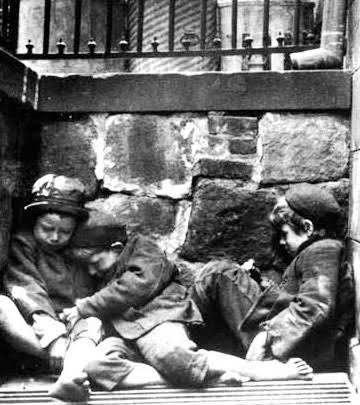

They thought the poor deserved to stay poor because they were lazy and/or undeserving of fortune.

Orphans would remain orphans even after adoption and were often regarded as intruders and outsiders. An adopted lower class orphan could never be associated with the rich family that adopted them. Adopted orphans could be abandoned and were often subject to harsher punishments and less care. Around 60% of the criminals were estimated to be orphans because of their situation.

They literally shoved naked toddlers up hot soot filled chimneys to clean them leading them to develop cancer and other terminal diseases. Many of these kids would sometimes get stuck in the chimneys and people would try to smoke them out by lighting a fire under them. Sometimes they'd have to leave the stuck child there because it was too hard to get them out and let them die there. The nobility and the master sweeps threw a massive hissy fit when the practice was abolished and actually continued the practice till very very recently. Oh and the kids literally slept with the same rag blanket they used to collect the chimney dirt during the day.

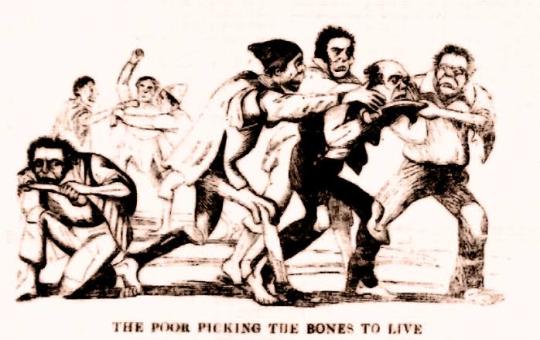

The Andover Workhouse Scandal- the workers were so starved and underpaid they ate the animal bones they were supposed to be crushing.

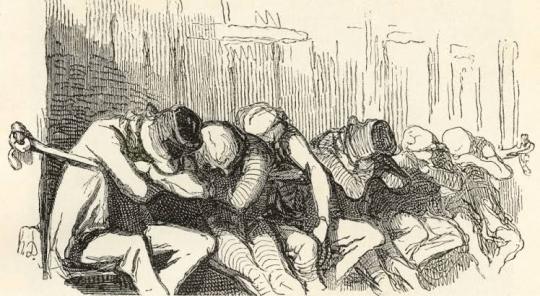

The fucking Two Penny Hangover- a sleeping arrangement for the poor where you slept hanging on a rope for 2 pennies completely exposed to the elements and they woke you up by untying the rope on one end and letting you crash face first into the floor.

Or you could sleep in the 4 penny coffin if you managed to have enough to spare.

The Poor Law Amendment of 1834. Oh how do we fix poverty? Why, by getting those lazy homeless bastards off their assess and forcing them to do gruelling absolutely awful work at warehouses for bare minimum wages and then when they can't pay off the loans and debts, by tossing the entire family into prisons and running them into the ground with work and little food.

Somewhat less related but Ignaz Semmelweis went insane because he was mocked and attacked for insisting that the victorian doctors actually wash their hands before performing child births after working at the morgue even though the doctors were practically causing a large number of pregnant women to die due to sepsis.

Seriously, read any Charles Dickens or Thomas Hardy book and you'll see absolutely how disgusting so many of the upper and middle class people were.

#tw: child abuse#yuuMori#yuukoku no moriarty#moriarty the patriot#meta#the series does lowkey exaggerate aspects but its not far off from the reality#of what someone like Liam and Louis would have experienced#or how the nobility and the aristocracy would have treated the poor

141 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this has been asked before but have you seen a translation of the sick Vyn SSR card? If so, what are your thoughts?

Yeah, I've read it--I love it so much, since it showcases Vyn's more polarizing nature (neediness, childish petulance, among others). It also affords another look at his background, too, through parallels between him and the kitten.

Spoilery bits after the cut!

Also damn I found it bittersweet, how he obviously wanted to make peace with Rosa after she pushed him away (in his POV) so he can focus on his work, without even taking into account his input on the matter. He totally didn't need to deliver her meals daily, but he did anyway--he really wanted to see her, only to chicken out at the last minute to respect her wishes to be independent of him.

I found it really sweet of him. And oh, his disappointment and hurt when Rosa told him not to stay...yeah. Poor Vynmeow. I shall treat him more lovingly in future fics (haha).

Not to mention his petty, childish sassy moments during their small non-arguments. I'm a sucker for gap moe, and seeing two-doctorates, elegant Vyn being petty and petulant when making a point at Rosa just tickles me.

We also see more glimpses of Vyn's background, too, through the kitten. I'm not going to expound on it word for word but, its sort of sad, in a way, that the kitten is forced to make do with what surroundings it has to survive. In an environment when showing weakness is tantamount to offering itself as fodder to the food chain, it isn't much of a stretch to see young Vilhelm stoically carrying himself in a way where he had to resort to hide behind facades just so people wouldn't know how vulnerable he is at the time. It's certainly not something a young person--who's supposed to grow, learn, become their own person--should undergo. But thems the breaks when growing up into aristocracy/nobility, probably.

One can only imagine the weight of burden that he had to deal with, all by himself. And like the kitten, who wants to survive, he had to make do with that he had, and luckily met Rosa, someone who can provide him with much-needed emotional support. Finally, Vyn can breathe easy a little bit, and allow himself to lean on someone...

Rosa has her moments here too. Like how reckless she tends to be when playing savior (kitten, hiding Vyn in car). This is also the same reason she got publicly berated by Artem during that huge argument over a case. It's the typical shonen protagonist I Want To Save The World tendency that Rosa has, and I actually...like her for it? Sure it puts her in terrible situations at times and causes trouble for the people around her but, like in real life sometimes it takes drastic measures to effect change--and we know how much Rosa wants to make the world a better place, through her lawyer profession.

She just needs the support of the dudes around her to temper her self-destructive tendencies a little. I'm very biased towards Vyn, of course, so I would argue that his methods (provide guidance but allow her independence) is best for someone like her.

Anyway.

That out of the way, CAN I GUSH AT HOW HOT THE ICE CREAM SCENE IS THANK YOU HOYO FOR MAKING ORAL FIXATION VYN CANON. Like goddamn ice cream kiss that is so fucking hot I'm still blushing at the thought of it aaaaaaaaaaa

Also WHY IS NO ONE TALKING ABOUT THE FADE TO BLACK BIT DURING HIS TELECONFERENCE. Dude is totally making out/doing it with Rosa during the teleconference. Holy. Shit. Thank you for giving me daydream fodder for me to endure having to sit through painfully boring work teleconferences, Dr. Sexy.

I think I have blathered on enough and I should sleep now but thanks for this kind of ask (and letting me go on and on like an obsessed idiot)!

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

aristocrat!hongjoong

aristocrat!hoongjong x fem!reader headcanon

genre: fluff, angst

trigger warning(s): swearing, brief violence, mentions of unwanted sexual remarks. let me know if there’s anything else!

author’s note: this is the first time in years that i’ve written something omg 😅 😅 lemme know what you guys think!! 💕 💕

none of the pictures are mine!!

for reference, i’m using british peerage (hierarchy). there are five ranks: baron, viscount, earl (count), marquess, and duke - the highest being duke, and the lowest, baron.

second son of an earl

despite being born into wealth and nobility, i think he’d be pretty grounded and level-headed

has to do with the fact that he’s naturally empathetic and curious

leads to a bit of a rebellious streak

more or less acts according to his parents expectations before them

but often does things that would scandalize them behind their backs

one of his favourite things to do is to sneak out during the manor at night dressed in commoner’s clothes

(which are carefully hidden in the music room)

his older brother takes the brunt of parental and societal pressure to act a certain way, but that doesn’t mean joong is off the hook

aristocracy just has so many god-forsake rules and mannerisms that everyone has to follow

unless they want to disgrace their entire family and lineage

yeaaah,,,

the only places he genuinely feels free are: a) in the music room, and b) exploring the city with you

during the third or fourth time he snuck out, he visited a local tavern.

cue you working as a tavern maiden

after serving him one (1) drink, you could tell that joong wasn’t actually a “commoner”

his clothes might have been worn and cheaply made, but his mannerisms,,,just didn’t match up

he was a little too polite; held himself a little too well

not to mention the hungry gleam of curiosity in his eyes

like everything was new and he was trying to absorb as much as he could

unfortunately for him, you weren’t the only one that noticed

after one too many drinks, some brutish fellows swaggered up to him

“‘ey there pal, ya werldn’t mind ‘anding sum coins over, would ya? ‘elp a brotha out”

joong, who had become a little too brazen thanks to the alcohol, told them to fuck off and stumbled to his feet, ready for a fight

except he couldn’t stand straight

and he didn’t have his sword

not good

luckily for joong, these fellows had been pestering you for the longest time

they were unusually rowdy and loud - which was saying something cause this was a tavern for fuck’s sake

and they constantly threw lewd remarks your way

but they didn’t actually do anything or break any of the tavern’s rules, so you had to serve their drinks with your best forced smile

they didn’t even tip well

assholes

anyways, back to the situation at hand

seeing a fight about to break out - which most definitely was against the rules - you hollered for the owner

“OI, A FIGHT’S ‘BOUT TO BREAK OUT!”

cue an angry-looking, burly man (with quite the ginger beard) and a very angry bar maiden (yes, you) tossing their sorry asses out the back door

joong, who by now had stumbled back into his seat, watched the scene with his mouth agape

to be frank, he’d never seen a woman act the way you did

all the women in his life were meek and docile

like a china doll that would break with one wrong move

they needed to be shielded, protected

clearly, you didn’t need protection

not when you hauled a man twice your size out the door, getting a good sucker punch for all the times they talked about your tits and ass

Right. In. Front. Of. Your. Face.

from that day on, joong became a regular at the tavern

he was careful not to drink as much as he did on the first time, at most getting tipsy

always polite and respectful

a bit on the quieter side, but made pleasant small talk whenever you took his order or served him his drinks

several months passed like this, and you’d become quite fond of him.

definitely helped that he was easy on the eyes

then one night, when he felt a little braver than usual, he invited you on a midnight adventure after your shift

you were pretty tired ngl, but you couldn’t turn him down after seeing the hopeful glimmer in his eyes

and boy, were you glad you didn’t

you don’t think you’ve ever felt so carefree in your life

or had so much fun

racing across bridges, exploring the hidden nooks and crannies of the city

much to your chagrin, joong would buy you (expensive) snacks that you just had to try because “he wasn’t gonna let his favourite girl miss out”

you ignored the fluttery feeling in your tummy

quickly, these “midnight adventures” became a frequent thing

he’d have a drink at the tavern, wait for you to finish your shift, and then the two of you would set off

you learned a lot about joong

of course he would have his spoiled rich boy™ moments-

“what do you MEAN you’ve never tried cane sugar?!”

“joong, not everyone gets it imported to their house”

but he genuinely just has such a good heart

always listens when you need to rant or vent

(and offers surprisingly practical advice)

never once thought of you as lesser than him for being poor or a commoner

quickly learned that you felt uncomfortable when (in your eyes) he spent too much money on you, so he made sure to be more conscientious

(also gave him a reality check. it forced him to acknowledge the things he didn’t even realize he took for granted)

tells you about all the dumb gossip he hears through the noble grapevine

“who CARES if the color of the fabric is slightly off?! i swear park has a rod up his ass-”

especially loves to tell you about the music he’s composed

even if he gets a little shy at times

cute

he just looks so happy when he talks about music. the way his gums would show when he smiles, the crinkles in the corners of his eyes, the way he’d grab a stick and draw different musical notations in the dirt to show you what he meant

happiness looked good on hongjoong

he even went as far to sneak you into his music room, playing the songs he wrote

and god did he look beautiful

the way the moonlight pooled on his fingers and spilled onto the bone-white piano keys

the way he looked so at ease

the way the music breathed, lived, jumping off the scraggly parchment paper to dance under starlight

(you think that’s the moment you started falling for him)

fast forward and the two of you have been friends for a few years now

you know everything about him, and he knows everything about you

unfortunately, the older he gets, the more responsibilities his parents hand him

meaning he can’t sneak out as often as he’d like

but he still makes sure to see you at least once a week

on one particular night, you notice that hongjoong’s been especially quiet

been particularly insistent on treating you to your favourite snacks

you mention this to him, but he brushes it off by saying he feels bad for not being able to be there for you as much as he’d like

hongjoong was a good liar (even if he didn’t like it), but you knew that he wasn’t telling you the truth

not the whole truth, at least

but you didn’t press it; he’d tell in his own time

so the two of you raced across bridges, laughter bouncing off the walled shops

exploring every nook and cranny of the city even if the two of you knew it like the back of your hands

and eventually, the two of you would lay in your favourite field on the outskirts of the city, staring at the stars in peaceful silence

well, peaceful for you

joong felt hollow

or maybe like someone filled his stomach and chest with stones

hongjoong wasn’t an idiot; he knew you liked him

and he knew he was in love with you

you and your calloused hands

your dress permanently stained with ale

your knot of hair messily pulled back to keep it out of your face as you worked

your boisterous laugh

your bright eyes and smile

how you weren’t afraid to call him out on his rich boy shit™

the way you’d take off your shoes and dance in the field under the night sky

how you were a strong willed and free-spirited woman, but you let him take care of you from time to time

the way his eyes would linger on you when he thought you weren’t looking

the way your eyes would linger on him when you thought he wasn’t looking

“accidental” brushes of the arm, of hands

no, he wasn’t stupid

so how was he supposed to tell you he was getting married?

#ateez#ateez hongjoong#ateez seonghwa#ateez yunho#ateez yeosang#ateez san#ateez mingi#ateez wooyoung#ateez jongho#ateez fluff#ateez angst#kim hongjoong#hongjoong#ateez x reader#ateez x female reader#ateez headcanons#ateez fanfic#ateez fanfiction#aristocrat!ateez#ateez smut

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Revolution (AO3)

Summary: It seems that even love cannot conquer a class divide, but maybe there's a little more to it than that? 1.8k

Written for the @writersofdestiel ‘Valentine’s Fic Exchange 2020′, for the wonderful @thunderthighsmish, who requested a historical AU.

The pounding on the oak door was sudden, loud, and showing no signs of stopping. The unrest within the city had left all of the aristocracy and nobility within Paris feeling uneasy, and the abrupt banging on the door only further served to leave an unsettled feeling in the stomachs of the residents of this particular household.

Vicomte Castiel Novak exchanged equally distressed looks with his parents, before abandoning his dinner to answer the insistent knocking. He stopped their housekeeper, Ellen, as she made for the door, instead sending her back to her duties in the kitchen.

As he pulled open the door, Castiel’s heart skipped a beat as Dean stood before him. It had been almost a year since he’d last seen his childhood best friend and first love, and for a moment nothing but happiness enveloped him. He hadn’t changed much at all, really. Same green eyes, same countless freckles, same dirt smudges across his cheek—

Right. The reason Castiel hadn’t seen Dean in nearly a year came flooding back and his eyes widened as he glanced backwards into the house, to make sure his parents hadn’t seen him. After their fight on Valentine’s Day, after Dean had pushed him away, Castiel’s parents had vowed to have Dean arrested if he ever came near their family home again.

“What are you doing here?” He asked, trying to crowd Dean backwards so he could close the door behind them. Despite being recognised as an adult, Castiel was all too aware of what his parents thought of Dean, and had no intention of letting them see him.

“They’re coming.” Dean’s face was defiant under all the dirt, but there was something very akin to fear in his eyes.

“Who’s coming?” Castiel sighed, feeling frustrated and unnerved by coming face-to-face with Dean without any prior warning. It left him with a whirlwind of emotion that he had yet to sort through. “What are you talking about?”

Fists grabbed the front of Castiel’s cravat, but the gesture was not an attack. Dean stared at him fiercely, and Castiel fell silent, knowing that this wasn’t some trick or play on Dean’s part. Something had happened, something that had brought Dean back to him after so long.

“Everyone is coming. The people. The revolution.”

“There is always a revolution.” Castiel froze, his shoulders locking with tension as he heard the reply come from behind him, recognised the authoritarian tone of his father, a Comte that was used to his every order being obeyed. “The people will fail and learn their place as they have always done before. You will release my son.”

Dean clenched his jaw in anger and opened his fist, letting Castiel’s cravat slip from his fingers. “They took the Bastille a little under an hour ago and freed the prisoners. Then they put the Governor's head on a spike.”

Castiel’s father swore under his breath and opened the door wider. Castiel felt himself being tugged inside and he reached out blindly, hands finding Dean’s sleeve. He clung on tightly, refusing to let go, hauling Dean in with them.

“You’re sure?”

Dean nodded. “They’re coming here next. The victory has given them confidence. Not immediately, good men were lost and they plan to mourn. But your name was mentioned. They’re stopping all exits out of the city and then they’re coming. You don’t have long.”

“How do you know all this?” Castiel cringed as his mother joined them in the entry hall, having overheard every word of their conversation.

There was a moment of awkwardness, where Castiel could see Dean brace himself and knew the answer to the question before Dean even opened his mouth.

“You joined the revolution?”

“Of course I did,” Dean snapped. “You wouldn’t understand, living here with your titles and your money, you’ve never had to worry about where your next meal was coming from. But you’re judging me for joining a movement that promises me a better life?”

Anger flared inside Castiel, replacing the hurt that had risen at Dean’s poor opinion of him. “Of course not. You know I’ve never felt like that.”

Dean scoffed. “Could’ve fooled me, Cas. You—”

“Enough!” Castiel’s father thundered. “You’ve done your duty and informed us of the threat to our lives. We will take the appropriate action and you can be on your way. In the future, you would do well to remember yourself and treat my son with the respect he deserves.”

Beneath the dirt and freckles, Dean’s face turned an unflattering shade of puce. His lips mouthed the word ‘duty’, but no sound came out, as if he was fighting back a thousand responses before eventually settling on, “Oui, Monsieur le Comte. My sincere apologies, Monsieur le Vicomte,” he spat at Castiel, the words filled with poison and bitterness.

“Stop that.” Castiel wanted to take hold of Dean by the shoulders and shake him, to rattle him until he saw signs of the boy he’d fallen in love with. This cold man before him, this angry person was not the kind-hearted boy he’d grown up with. “Stop that, Dean. There have never been titles between us.”

Dean shook his head, his anger fading as quickly as it had appeared, replaced by a resigned sadness. His eyes were averted, and he seemed to be avoiding Castiel’s attempts to catch his eye. “You’re wasting time. And you’ll never make it out of the city without me. I’ve arranged passage out of Paris, from there you’re on your own.”

Castiel felt the breath knocked from his lungs at the finality and dismissal of Dean’s tone. He stared numbly, struck with the knowledge that life as he knew it was over. But he would not mourn for that. Instead, he would mourn for a childhood love that had been doomed to failure.

It seemed that even love could not conquer a class divide.

The Comtesse placed her gloved hand on Castiel’s shoulder in a gesture of comfort. “My son, make your farewells. We must prepare.”

“Maman,” Castiel whispered, his eyes closing in a desperate attempt to block out that last expression on Dean’s face. He wanted to remember the happier times they had together. “Please forgive me. I can’t go with you.”

“Castiel—”

Her objection was lost as Dean’s eyes once again turned to him, surprise clouding his expression. “Don’t be an idiot, Cas. You’ll be killed if you stay here.”

“But if I go, I’ll never see you again.”

“You were never going to see me again anyway,” Dean sighed. “We’re not the same, Cas. You’re a fool if you think it didn’t matter that you’re a Vicomte. Of course it matters.”

“To you,” Castiel burst out. “Not to me. I loved you. I’ve always loved you. It wasn’t me that decided it wasn’t worth it, Dean. It wasn’t me that abandoned you. I’ve always been right here.”

Dean clenched his jaw and said nothing, just stared directly through Castiel as if he wasn’t even there.

“He was undesirable,” Castiel’s father spoke up. “An unsuitable match for a future Comte. I knew his brother was sick and he needed medicine. We gave him money and told him not to come back.”

And that answered every question Castiel had. Why Dean had argued with him, told him that Castiel was just another stuck up aristocrat, that he never wanted to see him again. While it didn’t surprise him that his parents had taken steps to remove Dean from his life—they’d never made a secret of their feelings towards him—it was like a blade to the chest to hear that Dean had let them. That he’d been party to it.

Castiel buried his face in his hands and tried to compose himself, trying to hide tears that stung his eyes, even though he couldn’t stop them falling. Then hands were encircling his wrists, pulling his arms down and away from his face, a familiar, almost tender touch that just made the ache in his chest worse.

“I’m so sorry,” Dean whispered, and there was a soft kiss pressed to his knuckles. “Sam was sick, we didn’t think he was going to make it through the winter. I had to, Cas. I’m so sorry. It was the worst choice I ever had to make.”

“You could have told me.” Castiel pulled his hands away from Dean and dried his eyes. “Instead you made me believe that this was all my fault.”

Dean swiped at his own eyes, taking Castiel’s hands again, refusing to give up now that everything was out in the open. “It was the only way you’d believe me. The only way you’d let it go.”

The years fell away between them as they stepped towards each other. There were no signals, or words spoken, but in unison they fell into each other’s arms.

“I love you,” Dean whispered, and Castiel kissed him. It was a brief moment of understanding and devotion, but it was all theirs and nothing could take that away from there.

“As I love you.”

The Comte cleared his throat, stepping forward. “Castiel, we can talk about this later, but we have to go.”

Castiel straightened to his full height and turned his reddened, but furious eyes on his parents. “Then go.”

“Castiel, you cannot stay here—” His mother began desperately, but Castiel cut her off.

“I can, and I will. I never needed any of this to be happy. I just needed Dean.” His icy blue eyes turned on his father. “You interfered with that once before, but you will never do so again. Leave. Take my mother and never come back.”

“There’s a carriage out the back that will take you as far as Lille. It will be a long journey. From there you should cross the border.” Dean told them, quietly. “Good luck.”

Castiel watched expressionlessly as his parents listened for the first time, rushing up the stairs to pack whatever they could carry.

Dean’s fingers laced with his own, drawing his attention. Castiel squeezed lightly. “You’re not going to make me go with them?”

“Never. But you should pack too, but light. Is there anything you can’t live without?”

Castiel looked at Dean, observing his beautiful green eyes. His freckles. The dirt smudges that were still smeared across his cheek. “Yes,” he said eventually. “But it’s right here.”

Masterpost

#writersofdestiel#spncreatorsdaily#destieldrabblesdaily#yourspecialeyes#deancasfanficnet#spn#destiel#destiel fanfic#dicespn#destieldice

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAW # 34 : BE ROYAL IN YOUR OWN FASHION: ACT LIKE A KING TO BE TREATED LIKE ONE

JUDGEMENT

The way you carry yourself will often determine how you are treated: In the long run, appearing vulgar or common will make people disrespect you. For a king respects himself and inspires the same sentiment in others. By acting regally and confident of your powers, you make yourself seem destined to wear a crown.

TRANSGRESSION OF THE LAW

In July of 1830, a revolution broke out in Paris that forced the king, Charles X, to abdicate. A commission of the highest authorities in the land gathered to choose a successor, and the man they picked was Louis-Philippe, the Duke of Orléans.

From the beginning it was clear that Louis-Philippe would be a different kind of king, and not just because he came from a different branch of the royal family, or because he had not inherited the crown but had been given it, by a commission, putting his legitimacy in question. Rather it was that he disliked ceremony and the trappings of royalty; he had more friends among the bankers than among the nobility; and his style was not to create a new kind of royal rule, as Napoleon had done, but to downplay his status, the better to mix with the businessmen and middle-class folk who had called him to lead. Thus the symbols that came to be associated with Louis-Philippe were neither the scepter nor the crown, but the gray hat and umbrella with which he would proudly walk the streets of Paris, as if he were a bourgeois out for a stroll. When Louis-Philippe invited James Rothschild, the most important banker in France, to his palace, he treated him as an equal. And unlike any king before him, not only did he talk business with Monsieur Rothschild but that was literally all he talked, for he loved money and had amassed a huge fortune.

As the reign of the “bourgeois king” plodded on, people came to despise him. The aristocracy could not endure the sight of an unkingly king, and within a few years they turned on him. Meanwhile the growing class of the poor, including the radicals who had chased out Charles X, found no satisfaction in a ruler who neither acted as a king nor governed as a man of the people. The bankers to whom Louis-Philippe was the most beholden soon realized that it was they who controlled the country, not he, and they treated him with growing contempt. One day, at the start of a train trip organized for the royal family, James Rothschild actually berated him—and in public—for being late. Once the king had made news by treating the banker as an equal; now the banker treated the king as an inferior.

Eventually the workers’ insurrections that had brought down Louis-Philippe’s predecessor began to reemerge, and the king put them down with force. But what was he defending so brutally? Not the institution of the monarchy, which he disdained, nor a democratic republic, which his rule prevented. What he was really defending, it seemed, was his own fortune, and the fortunes of the bankers—not a way to inspire loyalty among the citizenry.

Never lose your self-respect, nor be too familiar with yoetrself when you are alone. Let your integrity itself be your own standard of rectitude, and be more indebted to the severity of your own judgment of yourself than to all external precepts. Desist from unseemly conduct, rather out of respect for your own virtue than for the strictures of external authority. Come to hold yourself in awe, and you will have no need of Seneca’s imaginary tittor.

BALIASAR GRACIAN. 1601-1658

In early 1848, Frenchmen of all classes began to demonstrate for electoral reforms that would make the country truly democratic. By February the demonstrations had turned violent. To assuage the populace, Louis-Philippe fired his prime minister and appointed a liberal as a replacement. But this created the opposite of the desired effect: The people sensed they could push the king around. The demonstrations turned into a full-fledged revolution, with gunfire and barricades in the streets.

On the night of February 23, a crowd of Parisians surrounded the palace. With a suddenness that caught everyone by surprise, Louis-Philippe abdicated that very evening and fled to England. He left no successor, nor even the suggestion of one—his whole government folded up and dissolved like a traveling circus leaving town.

Interpretation

Louis-Philippe consciously dissolved the aura that naturally pertains to kings and leaders. Scoffing at the symbolism of grandeur, he believed a new world was dawning, where rulers should act and be like ordinary citizens. He was right: A new world, without kings and queens, was certainly on its way. He was profoundly wrong, however, in predicting a change in the dynamics of power.

The bourgeois king’s hat and umbrella amused the French at first, but soon grew irritating. People knew that Louis-Philippe was not really like them at all—that the hat and umbrella were essentially a kind of trick to encourage them in the fantasy that the country had suddenly grown more equal. Actually, though, the divisions of wealth had never been greater. The French expected their ruler to be a bit of a showman, to have some presence. Even a radical like Robespierre, who had briefly come to power during the French Revolution fifty years earlier, had understood this, and certainly Napoleon, who had turned the revolutionary republic into an imperial regime, had known it in his bones. Indeed as soon as Louis-Philippe fled the stage, the French revealed their true desire: They elected Napoleon’s grand-nephew president. He was a virtual unknown, but they hoped he would re-create the great general’s powerful aura, erasing the awkward memory of the “bourgeois king.”

Powerful people may be tempted to affect a common-man aura, trying to create the illusion that they and their subjects or underlings are basically the same. But the people whom this false gesture is intended to impress will quickly see through it. They understand that they are not being given more power—that it only appears as if they shared in the powerful person’s fate. The only kind of common touch that works is the kind affected by Franklin Roosevelt, a style that said the president shared values and goals with the common people even while he remained a patrician at heart. He never pretended to erase his distance from the crowd.

Leaders who try to dissolve that distance through a false chumminess gradually lose the ability to inspire loyalty, fear, or love. Instead they elicit contempt. Like Louis-Philippe, they are too uninspiring even to be worth the guillotine—the best they can do is simply vanish in the night, as if they were never there.

OBSERVANCE OF THE LAW

When Christopher Columbus was trying to find funding for his legendary voyages, many around him believed he came from the Italian aristocracy. This view was passed into history through a biography written after the explorer’s death by his son, which describes him as a descendant of a Count Colombo of the Castle of Cuccaro in Montferrat. Colombo in turn was said to be descended from the legendary Roman general Colonius, and two of his first cousins were supposedly direct descendants of an emperor of Con stantinople. An illustrious background indeed. But it was nothing more than illustrious fantasy, for Columbus was actually the son of Domenico Colombo, a humble weaver who had opened a wine shop when Christopher was a young man, and who then made his living by selling cheese.

Columbus himself had created the myth of his noble background, because from early on he felt that destiny had singled him out for great things, and that he had a kind of royalty in his blood. Accordingly he acted as if he were indeed descended from noble stock. After an uneventful career as a merchant on a commercial vessel, Columbus, originally from Genoa, settled in Lisbon. Using the fabricated story of his noble background, he married into an established Lisbon family that had excellent connections with Portuguese royalty.

Through his in-laws, Columbus finagled a meeting with the king of Portugal, Joao II, whom he petitioned to finance a westward voyage aimed at discovering a shorter route to Asia. In return for announcing that any discoveries he achieved would be made in the king’s name, Columbus wanted a series of rights: the title Grand Admiral of the Oceanic Sea; the office of viceroy over any lands he found; and 10 percent of the future commerce with such lands. All of these rights were to be hereditary and for all time. Columbus made these demands even though he had previously been a mere merchant, he knew almost nothing about navigation, he could not work a quadrant, and he had never led a group of men. In short he had absolutely no qualifications for the journey he proposed. Furthermore, his petition included no details as to how he would accomplish his plans, just vague promises.

When Columbus finished his pitch, João II smiled: He politely declined the offer, but left the door open for the future. Here Columbus must have noticed something he would never forget: Even as the king turned down the sailor’s demands, he treated them as legitimate. He neither laughed at Columbus nor questioned his background and credentials. In fact the king was impressed by the boldness of Columbus’s requests, and clearly felt comfortable in the company of a man who acted so confidently. The meeting must have convinced Columbus that his instincts were correct: By asking for the moon, he had instantly raised his own status, for the king assumed that unless a man who set such a high price on himself were mad, which Columbus did not appear to be, he must somehow be worth it.

In the next generation the family became much more famous than before through the distinction conferred upon it by Cleisthenes the master of Sicyon. Cleisthenes... had a daughter, Agarista, whom he wished to marry to the best man in all Greece. So during the Olympic games, in which he had himself won the chariot race, he had a public announcement made, to the effect that any Greek who thought himself good enough to become Cleisthenes’ son-in-law should present himself in Sicyon within sixty days—or sooner if he wished—because he intended, within the year following the sixtieth day, to betroth his daughter to her future husband. Cleisthenes had had a race-track and a wrestling-ring specially made for his purpose, and presently the suitors began to arrive—every man of Greek nationality who had something to be proud of either in his country or in himself.... Cleisthenes began by asking each [of the numerous suitors] in turn to name his country and parentage; then he kept them in his house for a year, to get to know them well, entering into conversation with them sometimes singly, sometimes all together, and testing each of them for his manly qualities and temper, education and manners.... But the most important test of all was their behaviour at the dinner-table. All this went on throughout their stay in Sicyon, and all the time he entertained them handsomely. For one reason or another it was the two Athenians who impressed Cleisthenes most favourably, and of the two Tisander’s son Hippocleides came to be preferred.... At last the day came which had been fixed for the betrothal, and Cleisthenes had to declare his choice. He nzarked the day by the sacrifice of a hundred oxen, and then gave a great banquet, to which not only the suitors but everyone of note in Sicyon was invited. When dinner was over, the suitors began to compete with each other in music and in talking in company. In both these accomplishments it was Hippocleides who proved by far the doughtiest champion, until at last, as more and more wine was drunk, he asked the flute-player to play him a tune and began to dance to it. Now it may well be that he danced to his own satisfaction; Cleisthenes, however, who was watching the performance, began to have serious doubts about the whole business. Presently, after a brief pause, Hippocleides sent for a table; the table was brought, and Hippocleides, climbing on to it, danced first some Laconian dances, next some Attic ones, and ended by standing on his head and beating time with his legs in the air The Laconian and Attic dances were bad enough; but Cleisthenes, though he already loathed the thought of having a son-in-law like that, nevertheless restrained himself and managed to avoid an outburst; but when he saw Hippocleides beating time with his legs, he could bear it no longer. “Son of Tisander, ”he cried, “you have danced away your marriage. ”

THE HISTORIES, Herodotus, FIFTH CENTURY B.C.

A few years later Columbus moved to Spain. Using his Portuguese connections, he moved in elevated circles at the Spanish court, receiving subsidies from illustrious financiers and sharing tables with dukes and princes. To all these men he repeated his request for financing for a voyage to the west—and also for the rights he had demanded from João II. Some, such as the powerful duke of Medina, wanted to help, but could not, since they lacked the power to grant him the titles and rights he wanted. But Columbus would not back down. He soon realized that only one person could meet his demands: Queen Isabella. In 1487 he finally managed a meeting with the queen, and although he could not convince her to finance the voyage, he completely charmed her, and became a frequent guest in the palace.

In 1492 the Spanish finally expelled the Moorish invaders who centuries earlier had seized parts of the country. With the wartime burden on her treasury lifted, Isabella felt she could finally respond to the demands of her explorer friend, and she decided to pay for three ships, equipment, the salaries of the crews, and a modest stipend for Columbus. More important, she had a contract drawn up that granted Columbus the titles and rights on which he had insisted. The only one she denied—and only in the contract’s fine print—was the 10 percent of all revenues from any lands discovered: an absurd demand, since he wanted no time limit on it. (Had the clause been left in, it would eventually have made Columbus and his heirs the wealthiest family on the planet. Columbus never read the fine print.)

Satisfied that his demands had been met, Columbus set sail that same year in search of the passage to Asia. (Before he left he was careful to hire the best navigator he could find to help him get there.) The mission failed to find such a passage, yet when Columbus petitioned the queen to finance an even more ambitious voyage the following year, she agreed. By then she had come to see Columbus as destined for great things.

Interpretation

As an explorer Columbus was mediocre at best. He knew less about the sea than did the average sailor on his ships, could never determine the latitude and longitude of his discoveries, mistook islands for vast continents, and treated his crew badly. But in one area he was a genius: He knew how to sell himsel£ How else to explain how the son of a cheese vendor, a low-level sea merchant, managed to ingratiate himself with the highest royal and aristocratic families?

Columbus had an amazing power to charm the nobility, and it all came from the way he carried himself. He projected a sense of confidence that was completely out of proportion to his means. Nor was his confidence the aggressive, ugly self-promotion of an upstart—it was a quiet and calm self-assurance. In fact it was the same confidence usually shown by the nobility themselves. The powerful in the old-style aristocracies felt no need to prove or assert themselves; being noble, they knew they always deserved more, and asked for it. With Columbus, then, they felt an instant affinity, for he carried himself just the way they did—elevated above the crowd, destined for greatness.

Understand: It is within your power to set your own price. How you carry yourself reflects what you think of yourself. If you ask for little, shuffle your feet and lower your head, people will assume this reflects your character. But this behavior is not you—it is only how you have chosen to present yourself to other people. You can just as easily present the Columbus front: buoyancy, confidence, and the feeling that you were born to wear a crown.

With all great deceivers there is a noteworthy occurrence to which they owe their power. In the actual act of deception they are overcome by belief in themselves: it is this which then speaks so miraculously and compellingly to those around them.

Friedrich Nietzsche, 1844-1900

KEYS TO POWER

As children, we start our lives with great exuberance, expecting and demanding everything from the world. This generally carries over into our first forays into society, as we begin our careers. But as we grow older the rebuffs and failures we experience set up boundaries that only get firmer with time. Coming to expect less from the world, we accept limitations that are really self-imposed. We start to bow and scrape and apologize for even the simplest of requests. The solution to such a shrinking of horizons is to deliberately force ourselves in the opposite direction—to downplay the failures and ignore the limitations, to make ourselves demand and expect as much as the child. To accomplish this, we must use a particular strategy upon ourselves. Call it the Strategy of the Crown.

The Strategy of the Crown is based on a simple chain of cause and effect: If we believe we are destined for great things, our belief will radiate outward, just as a crown creates an aura around a king. This outward radiance will infect the people around us, who will think we must have reasons to feel so confident. People who wear crowns seem to feel no inner sense of the limits to what they can ask for or what they can accomplish. This too radiates outward. Limits and boundaries disappear. Use the Strategy of the Crown and you will be surprised how often it bears fruit. Take as an example those happy children who ask for whatever they want, and get it. Their high expectations are their charm. Adults enjoy granting their wishes—just as Isabella enjoyed granting the wishes of Columbus.

Throughout history, people of undistinguished birth—the Theodoras of Byzantium, the Columbuses, the Beethovens, the Disraelis—have managed to work the Strategy of the Crown, believing so firmly in their own greatness that it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The trick is simple: Be overcome by your self-belief. Even while you know you are practicing a kind of deception on yourself, act like a king. You are likely to be treated as one.

The crown may separate you from other people, but it is up to you to make that separation real: You have to act differently, demonstrating your distance from those around you. One way to emphasize your difference is to always act with dignity, no matter the circumstance. Louis-Philippe gave no sense of being different from other people—he was the banker king. And the moment his subjects threatened him, he caved in. Everyone sensed this and pounced. Lacking regal dignity and firmness of purpose, Louis-Philippe seemed an impostor, and the crown was easily toppled from his head.

Regal bearing should not be confused with arrogance. Arrogance may seem the king’s entitlement, but in fact it betrays insecurity. It is the very opposite of a royal demeanor.

Haile Selassie, ruler of Ethiopia for forty or so years beginning in 1930, was once a young man named Lij Tafari. He came from a noble family, but there was no real chance of him coming to power, for he was far down the line of succession from the king then on the throne, Menelik II. Nevertheless, from an early age he exhibited a self-confidence and a royal bearing that surprised everyone around him.

At the age of fourteen, Tafari went to live at the court, where he immediately impressed Menelik and became his favorite. Tafari’s grace under fire, his patience, and his calm self-assurance fascinated the king. The other young nobles, arrogant, blustery, and envious, would push this slight, bookish teenager around. But he never got angry—that would have been a sign of insecurity, to which he would not stoop. There were already people around him who felt he would someday rise to the top, for he acted as if he were already there.

Years later, in 1936, when the Italian Fascists had taken over Ethiopia and Tafari, now called Haile Selassie, was in exile, he addressed the League of Nations to plead his country’s case. The Italians in the audience heckled him with vulgar abuse, but he maintained his dignified pose, as if completely unaffected. This elevated him while making his opponents look even uglier. Dignity, in fact, is invariably the mask to assume under difficult circumstances: It is as if nothing can affect you, and you have all the time in the world to respond. This is an extremely powerful pose.

A royal demeanor has other uses. Con artists have long known the value of an aristocratic front; it either disarms people and makes them less suspicious, or else it intimidates them and puts them on the defensive—and as Count Victor Lustig knew, once you put a sucker on the defensive he is doomed. The con man Yellow Kid Weil, too, would often assume the trappings of a man of wealth, along with the nonchalance that goes with them. Alluding to some magical method of making money, he would stand aloof, like a king, exuding confidence as if he really were fabulously rich. The suckers would beg to be in on the con, to have a chance at the wealth that he so clearly displayed.

Finally, to reinforce the inner psychological tricks involved in projecting a royal demeanor, there are outward strategies to help you create the effect. First, the Columbus Strategy: Always make a bold demand. Set your price high and do not waver. Second, in a dignified way, go after the highest person in the building. This immediately puts you on the same plane as the chief executive you are attacking. It is the David and Goliath Strategy: By choosing a great opponent, you create the appearance of greatness.

Third, give a gift of some sort to those above you. This is the strategy of those who have a patron: By giving your patron a gift, you are essentially saying that the two of you are equal. It is the old con game of giving so that you can take. When the Renaissance writer Pietro Aretino wanted the Duke of Mantua as his next patron, he knew that if he was slavish and sycophantic, the duke would think him unworthy; so he approached the duke with gifts, in this case paintings by the writer’s good friend Titian. Accepting the gifts created a kind of equality between duke and writer: The duke was put at ease by the feeling that he was dealing with a man of his own aristocratic stamp. He funded Aretino generously. The gift strategy is subtle and brilliant because you do not beg: You ask for help in a dignified way that implies equality between two people, one of whom just happens to have more money.

Remember: It is up to you to set your own price. Ask for less and that is just what you will get. Ask for more, however, and you send a signal that you are worth a king’s ransom. Even those who turn you down respect you for your confidence, and that respect will eventually pay off in ways you cannot imagine.

Image: The Crown. Place it upon your head and you assume a different pose—tranquil yet radiating assurance. Never show doubt, never lose your dignity beneath the crown, or it will not fit. It will seem to be destined for one more worthy. Do not wait for a coronation; the greatest emperors crown themselves.

Authority: Everyone should be royal after his own fashion. Let all your actions, even though they are not those of a king, be, in their own sphere, worthy of one. Be sublime in your deeds, lofty in your thoughts; and in all your doings show that you deserve to be a king even though you are not one in reality. (Baltasar Gracián, 1601-1658)

REVERSAL

The idea behind the assumption of regal confidence is to set yourself apart from other people, but if you take this too far it will be your undoing. Never make the mistake of thinking that you elevate yourself by humiliating people. Also, it is never a good idea to loom too high above the crowd—you make an easy target. And there are times when an aristocratic pose is eminently dangerous.

Charles I, king of England during the 1640s, faced a profound public disenchantment with the institution of monarchy. Revolts erupted throughout the country, led by Oliver Cromwell. Had Charles reacted to the times with insight, supporting reforms and making a show of sacrificing some of his power, history might have been different. Instead he reverted to an even more regal pose, seeming outraged by the assault on his power and on the divine institution of monarchy. His stiff kingliness offended people and spurred on their revolts. And eventually Charles lost his head, literally. Understand: You are radiating confidence, not arrogance or disdain.

Finally, it is true that you can sometimes find some power through affecting a kind of earthy vulgarity, which will prove amusing by its extreme-ness. But to the extent that you win this game by going beyond the limits, separating yourself from other people by appearing even more vulgar than they are, the game is dangerous: There will always be people more vulgar than you, and you will easily be replaced the following season by someone younger and worse.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

LAW # 31 : CONTROL THE OPTIONS: GET OTHERS TO PLAY WITH THE CARDS YOU DEAL

JUDGEMENT

The best deceptions are the ones that seem to give the other person a choice: Your victims feel they are in control, but are actually your puppets. Give people options that come out in your favor whichever one they choose. Force them to make choices between the lesser of two evils, both of which serve your purpose. Put them on the horns of a dilemma: They are gored wherever they turn.

OBSERVANCE OF THE LAW I

From early in his reign, Ivan IV, later known as Ivan the Terrible, had to confront an unpleasant reality: The country desperately needed reform, but he lacked the power to push it through. The greatest limit to his authority came from the boyars, the Russian princely class that dominated the country and terrorized the peasantry.

In 1553, at the age of twenty-three, Ivan fell ill. Lying in bed, nearing death, he asked the boyars to swear allegiance to his son as the new czar. Some hesitated, some even refused. Then and there Ivan saw he had no power over the boyars. He recovered from his illness, but he never forgot the lesson: The boyars were out to destroy him. And indeed in the years to come, many of the most powerful of them defected to Russia’s main enemies, Poland and Lithuania, where they plotted their return and the overthrow of the czar. Even one of Ivan’s closest friends, Prince Andrey Kurbski, suddenly turned against him, defecting to Lithuania in 1564, and becoming the strongest of Ivan’s enemies.

When Kurbski began raising troops for an invasion, the royal dynasty seemed suddenly more precarious than ever. With émigré nobles fomenting invasion from the west, Tartars bearing down from the east, and the boyars stirring up trouble within the country, Russia’s vast size made it a nightmare to defend. In whatever direction Ivan struck, he would leave himself vulnerable on the other side. Only if he had absolute power could he deal with this many-headed Hydra. And he had no such power.

Ivan brooded until the morning of December 3, 1564, when the citizens of Moscow awoke to a strange sight. Hundreds of sleds filled the square before the Kremlin, loaded with the czar’s treasures and with provisions for the entire court. They watched in disbelief as the czar and his court boarded the sleds and left town. Without explaining why, he established himself in a village south of Moscow. For an entire month a kind of terror gripped the capital, for the Muscovites feared that Ivan had abandoned them to the bloodthirsty boyars. Shops closed up and riotous mobs gathered daily. Finally, on January 3 of 1565, a letter arrived from the czar, explaining that he could no longer bear the boyars’ betrayals and had decided to abdicate once and for all.

The German Chancellor Bismarck, enraged at the constant criticisms from Rudolf Virchow (the German pathologist and liberal politician), had his seconds call upon the scientist to challenge him to a duel. “As the challenged party, I have the choice of weapons,” said Virchow, “and I choose these.” He held aloft two large and apparently identical sausages. “One of these,” he went on, “is infected with deadly germs; the orher is perfectly sound. Let His Excellency decide which one he wishes to eat, and I will eat the other.” Almost immediately the message came back that the chancellor had decided to cancel the duel.

THE LITTLE. BROWN BOOK OF ANECDOTES. CLIFTON FADIMAN, FD., 1985

Read aloud in public, the letter had a startling effect: Merchants and commoners blamed the boyars for Ivan’s decision, and took to the streets, terrifying the nobility with their fury. Soon a group of delegates representing the church, the princes, and the people made the journey to Ivan’s village, and begged the czar, in the name of the holy land of Russia, to return to the throne. Ivan listened but would not change his mind. After days of hearing their pleas, however, he offered his subjects a choice: Either they grant him absolute powers to govern as he pleased, with no interference from the boyars, or they find a new leader.

Faced with a choice between civil war and the acceptance of despotic power, almost every sector of Russian society “opted” for a strong czar, calling for Ivan’s return to Moscow and the restoration of law and order. In February, with much celebration, Ivan returned to Moscow. The Russians could no longer complain if he behaved dictatorially—they had given him this power themselves.

Interpretation

Ivan the Terrible faced a terrible dilemma: To give in to the boyars would lead to certain destruction, but civil war would bring a different kind of ruin. Even if Ivan came out of such a war on top, the country would be devastated and its divisions would be stronger than ever. His weapon of choice in the past had been to make a bold, offensive move. Now, however, that kind of move would turn against him—the more boldly he confronted his enemies, the worse the reactions he would spark.

The main weakness of a show of force is that it stirs up resentment and eventually leads to a response that eats at your authority. Ivan, immensely creative in the use of power, saw clearly that the only path to the kind of victory he wanted was a false withdrawal. He would not force the country over to his position, he would give it “options”: either his abdication, and certain anarchy, or his accession to absolute power. To back up his move, he made it clear that he preferred to abdicate: “Call my bluff,” he said, “and watch what happens.” No one called his bluff. By withdrawing for just a month, he showed the country a glimpse of the nightmares that would follow his abdication—Tartar invasions, civil war, ruin. (All of these did eventually come to pass after Ivan’s death, in the infamous “Time of the Troubles.”)

Withdrawal and disappearance are classic ways of controlling the options. You give people a sense of how things will fall apart without you, and you offer them a “choice”: I stay away and you suffer the consequences, or I return under circumstances that I dictate. In this method of controlling people’s options, they choose the option that gives you power because the alternative is just too unpleasant. You force their hand, but indirectly: They seem to have a choice. Whenever people feel they have a choice, they walk into your trap that much more easily.

THE LIAR

Once upon a time there was a king of Armenia, who, being of a curious turn of mind and in need of some new diversion, sent his heralds throughout the land to make the following proclamation: “Hear this! Whatever man among you can prove himself the most outrageous liar in Armenia shall receive an apple made of pure gold from the hands of His Majesty the King!” People began to swarm to the palace from every town and hamlet in the country, people of all ranks and conditions, princes, merchants, farmers, priests, rich and poor, tall and short, fat and thin. There was no lack of liars in the land, and each one told his tale to the king. A ruler, however, has heard practically every sort of lie, and none of those now told him convinced the king that he had listened to the best of them. The king was beginning to grow tired of his new sport and was thinking of calling the whole contest off without declaring a winner, when there appeared before him a poor, ragged man, carrying a large earthenware pitcher under his arm. “What can I do for you?” asked His Majesty. “Sire!” said the poor man, slightly bewildered “Surely you remember? You owe me a pot of gold, and I have come to collect it.” “You are a pet feet liar, sir!’ exclaimed the king ”I owe you no money’” ”A perfect liar, am I?” said the poor man. ”Then give me the golden apple!” The king, realizing that the man was Irving to trick him. started to hedge. ”No. no! You are not a liar!” ”Then give me the pot of gold you owe me. sire.” said the man. The king saw the dilemma, He handed over the golden apple.

ARMENIAN FOLK-IALES AND FABLES. REIOLD BY CAHARLES DOWNING. 1993

OBSERVANCE OF THE LAW II

As a seventeenth-century French courtesan, Ninon de Lenclos found that her life had certain pleasures. Her lovers came from royalty and aristocracy, and they paid her well, entertained her with their wit and intellect, satisfied her rather demanding sensual needs, and treated her almost as an equal. Such a life was infinitely preferable to marriage. In 1643, however, Ninon’s mother died suddenly, leaving her, at the age of twenty-three, totally alone in the world—no family, no dowry, nothing to fall back upon. A kind of panic overtook her and she entered a convent, turning her back on her illustrious lovers. A year later she left the convent and moved to Lyons. When she finally reappeared in Paris, in 1648, lovers and suitors flocked to her door in greater numbers than ever before, for she was the wittiest and most spirited courtesan of the time and her presence had been greatly missed.

Ninon’s followers quickly discovered, however, that she had changed her old way of doing things, and had set up a new system of options. The dukes, seigneurs, and princes who wanted to pay for her services could continue to do so, but they were no longer in control—she would sleep with them when she wanted, according to her whim. All their money bought them was a possibility. If it was her pleasure to sleep with them only once a month, so be it.

Those who did not want to be what Ninon called a payeur could join the large and growing group of men she called her martyrs—men who visited her apartment principally for her friendship, her biting wit, her lute-playing, and the company of the most vibrant minds of the period, including Molière, La Rochefoucauld, and Saint-Évremond. The martyrs, too, however, entertained a possibility: She would regularly select from them a favori, a man who would become her lover without having to pay, and to whom she would abandon herself completely for as long as she so desired—a week, a few months, rarely longer. A payeur could not become a favori, but a martyr had no guarantee of becoming one, and indeed could remain disappointed for an entire lifetime. The poet Charleval, for example, never enjoyed Ninon’s favors, but never stopped coming to visit—he did not want to do without her company.

As word of this system reached polite French society, Ninon became the object of intense hostility. Her reversal of the position of the courtesan scandalized the queen mother and her court. Much to their horror, however, it did not discourage her male suitors—indeed it only increased their numbers and intensified their desire. It became an honor to be a payeur, helping Ninon to maintain her lifestyle and her glittering salon, accompanying her sometimes to the theater, and sleeping with her when she chose. Even more distinguished were the martyrs, enjoying her company without paying for it and maintaining the hope, however remote, of some day becoming her favori. That possibility spurred on many a young nobleman, as word spread that none among the courtesans could surpass Ninon in the art of love. And so the married and the single, the old and the young, entered her web and chose one of the two options presented to them, both of which amply satisfied her.

Interpretation

The life of the courtesan entailed the possibility of a power that was denied a married woman, but it also had obvious perils. The man who paid for the courtesan’s services in essence owned her, determining when he could possess her and when, later on, he would abandon her. As she grew older, her options narrowed, as fewer men chose her. To avoid a life of poverty she had to amass her fortune while she was young. The courtesan’s legendary greed, then, reflected a practical necessity, yet also lessened her allure, since the illusion of being desired is important to men, who are often alienated if their partner is too interested in their money. As the courtesan aged, then, she faced a most difficult fate.

Ninon de Lenclos had a horror of any kind of dependence. She early on tasted a kind of equality with her lovers, and she would not settle into a system that left her such distasteful options. Strangely enough, the system she devised in its place seemed to satisfy her suitors as much as it did her. The payeurs may have had to pay, but the fact that Ninon would only sleep with them when she wanted to gave them a thrill unavailable with every other courtesan: She was yielding out of her own desire. The martyrs’ avoidance of the taint of having to pay gave them a sense of superiority; as members of Ninon’s fraternity of admirers, they also might some day experience the ultimate pleasure of being her favori. Finally, Ninon did not force her suitors into either category. They could “choose” which side they preferred—a freedom that left them a vestige of masculine pride.

Such is the power of giving people a choice, or rather the illusion of one, for they are playing with cards you have dealt them. Where the alternatives set up by Ivan the Terrible involved a certain risk—one option would have led to his losing his power—Ninon created a situation in which every option redounded to her favor. From the payeurs she received the money she needed to run her salon. And from the martyrs she gained the ultimate in power: She could surround herself with a bevy of admirers, a harem from which to choose her lovers.

The system, though, depended on one critical factor: the possibility, however remote, that a martyr could become a favori. The illusion that riches, glory, or sensual satisfaction may someday fall into your victim’s lap is an irresistible carrot to include in your list of choices. That hope, however slim, will make men accept the most ridiculous situations, because it leaves them the all-important option of a dream. The illusion of choice, married to the possibility of future good fortune, will lure the most stubborn sucker into your glittering web.

J. P. Morgan Sr. once told a jeweler of his acquaintance that he was interested in buying a pearl scarf-pin. Just a few weeks later, the jeweler happened upon a magnificent pearl. He had it mounted in an appropriate setting and sent it to Morgan, together with a bill for $5,000. The following day the package was returned. Morgan’s accompanying note read: “I like the pin, but I don’t like the price. If you will accept the enclosed check for $4,000, please send back the box with the seal unbroken.” The enraged jeweler refused the check and dismissed the messenger in disgust. He opened up the box to reclaim the unwanted pin, only to find that it had been removed. In its place was a check for $5,000.

THE LITTLE, BROWN BOOK OF ANECDOTES. CLIFTON FADIMAN, ED.. 1985

KEYS TO POWER

Words like “freedom,” “options,” and “choice” evoke a power of possibility far beyond the reality of the benefits they entail. When examined closely, the choices we have—in the marketplace, in elections, in our jobs—tend to have noticeable limitations: They are often a matter of a choice simply between A and B, with the rest of the alphabet out of the picture. Yet as long as the faintest mirage of choice flickers on, we rarely focus on the missing options. We “choose” to believe that the game is fair, and that we have our freedom. We prefer not to think too much about the depth of our liberty to choose.

This unwillingness to probe the smallness of our choices stems from the fact that too much freedom creates a kind of anxiety. The phrase “unlimited options” sounds infinitely promising, but unlimited options would actually paralyze us and cloud our ability to choose. Our limited range of choices comforts us.

This supplies the clever and cunning with enormous opportunities for deception. For people who are choosing between alternatives find it hard to believe they are being manipulated or deceived; they cannot see that you are allowing them a small amount of free will in exchange for a much more powerful imposition of your own will. Setting up a narrow range of choices, then, should always be a part of your deceptions. There is a saying: If you can get the bird to walk into the cage on its own, it will sing that much more prettily.

The following are among the most common forms of “controlling the options”:

Color the Choices. This was a favored technique of Henry Kissinger. As President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, Kissinger considered himself better informed than his boss, and believed that in most situations he could make the best decision on his own. But if he tried to determine policy, he would offend or perhaps enrage a notoriously insecure man. So Kissinger would propose three or four choices of action for each situation, and would present them in such a way that the one he preferred always seemed the best solution compared to the others. Time after time, Nixon fell for the bait, never suspecting that he was moving where Kissinger pushed him. This is an excellent device to use on the insecure master.

Force the Resister. One of the main problems faced by Dr. Milton H. Erickson, a pioneer of hypnosis therapy in the 1950s, was the relapse. His patients might seem to be recovering rapidly, but their apparent susceptibility to the therapy masked a deep resistance: They would soon relapse into old habits, blame the doctor, and stop coming to see him. To avoid this, Erickson began ordering some patients to have a relapse, to make themselves feel as bad as when they first came in—to go back to square one. Faced with this option, the patients would usually “choose” to avoid the relapse—which, of course, was what Erickson really wanted.

This is a good technique to use on children and other willful people who enjoy doing the opposite of what you ask them to: Push them to “choose” what you want them to do by appearing to advocate the opposite.

Alter the Playing Field. In the 1860s, John D. Rockefeller set out to create an oil monopoly. If he tried to buy up the smaller oil companies they would figure out what he was doing and fight back. Instead, he began secretly buying up the railway companies that transported the oil. When he then attempted to take over a particular company, and met with resistance, he reminded them of their dependence on the rails. Refusing them shipping, or simply raising their fees, could ruin their business. Rockefeller altered the playing field so that the only options the small oil producers had were the ones he gave them.

In this tactic your opponents know their hand is being forced, but it doesn’t matter. The technique is effective against those who resist at all costs.

The Shrinking Options. The late-nineteenth-century art dealer Ambroise Vollard perfected this technique.

Customers would come to Vollard’s shop to see some Cézannes. He would show three paintings, neglect to mention a price, and pretend to doze off. The visitors would have to leave without deciding. They would usually come back the next day to see the paintings again, but this time Vollard would pull out less interesting works, pretending he thought they were the same ones. The baffled customers would look at the new offerings, leave to think them over, and return yet again. Once again the same thing would happen: Vollard would show paintings of lesser quality still. Finally the buyers would realize they had better grab what he was showing them, because tomorrow they would have to settle for something worse, perhaps at even higher prices.

A variation on this technique is to raise the price every time the buyer hesitates and another day goes by. This is an excellent negotiating ploy to use on the chronically indecisive, who will fall for the idea that they are getting a better deal today than if they wait till tomorrow.

The Weak Man on the Precipice. The weak are the easiest to maneuver by controlling their options. Cardinal de Retz, the great seventeenth-century provocateur, served as an unofficial assistant to the Duke of Orléans, who was notoriously indecisive. It was a constant struggle to convince the duke to take action—he would hem and haw, weigh the options, and wait till the last moment, giving everyone around him an ulcer. But Retz discovered a way to handle him: He would describe all sorts of dangers, exaggerating them as much as possible, until the duke saw a yawning abyss in every direction except one: the one Retz was pushing him to take.

This tactic is similar to “Color the Choices,” but with the weak you have to be more aggressive. Work on their emotions—use fear and terror to propel them into action. Try reason and they will always find a way to procrastinate.

Brothers in Crime. This is a classic con-artist technique: You attract your victims to some criminal scheme, creating a bond of blood and guilt between you. They participate in your deception, commit a crime (or think they do—see the story of Sam Geezil in Law 3), and are easily manipulated. Serge Stavisky, the great French con artist of the 1920s, so entangled the government in his scams and swindles that the state did not dare to prosecute him, and “chose” to leave him alone. It is often wise to implicate in your deceptions the very person who can do you the most harm if you fail. Their involvement can be subtle—even a hint of their involvement will narrow their options and buy their silence.

The Horns of a Dilemma. This idea was demonstrated by General William Sherman’s infamous march through Georgia during the American Civil War. Although the Confederates knew what direction Sherman was heading in, they never knew if he would attack from the left or the right, for he divided his army into two wings—and if the rebels retreated from one wing they found themselves facing the other. This is a classic trial lawyer’s technique: The lawyer leads the witnesses to decide between two possible explanations of an event, both of which poke a hole in their story. They have to answer the lawyer’s questions, but whatever they say they hurt themselves. The key to this move is to strike quickly: Deny the victim the time to think of an escape. As they wriggle between the horns of the dilemma, they dig their own grave.