#or maybe... a polyptych

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Hans Capon Character Analysis

Part 1: Hans' Disillusionment with the Nobility

I went into this wanting to write one thing and then instead ended up writing something different entirely which, after watching it get stupidly long, I decided to split in two. So you can consider this an analysis triptych (they other two are already drafted and ready to go). It's still stupidly long, so I apologize for that.

We know that Hans learned what the platonic ideal of a noble looked like and from that point on did his very best to live up to that ideal. He saw what he was supposed to be even while realizing that he could never live up to that ideal. Hans spends all his time trying to reach for perfection only to find his best only ever being at best shy of where he wants to be. More often, his best is far removed from where he thinks he's meant to be / supposed to be.

This is a theme that comes up several times throughout the game. First, when they're at the inn in Troskowitz where Hans pulls the "excuse" about why he can't do work:

I say "excuse" in quotes because the more time you spend talking to Hans the more it becomes obvious that he actually believes what he's saying. All that stuff about the three states of man is 100% something that he was either taught directly or overheard. It's entirely possible that he once tried to help out the castle staff and was told he wasn't allowed to do that because it went against the will of God. Like I fucking love AUs where Hans and Henry met as kids, but there's a non-zero chance that any attempt to do so, if not simply preempted, would have been shut down by Hanush and the others around him. This is what it means to be a noble, Hans. You're not allowed to do any of these fun things. You have a job to do. You're going to rule Rattay someday and that comes with certain responsibilities.

Here are some choice excerpts from that conversation:

I want to draw special attention here to the role that Hans places himself in, the role of the Bellator, a protector of others. This is what he's allowed to do. Remember that for later.

The other thing I want to draw attention to is this bit:

This isn't just about losing face. This is about the fact that he grew up hearing how wrong it would be for him to do peasant work. This is about the fact that he was told that if he did this, he'd be going against God, and everyone would think less of him for not acting as he's supposed to / required to. Not just in the eyes of God, but in the eyes of society.

Remember how I said that Hans has an idealized notion of nobility? That applies here as well. As the codex entry on the Three States of Man tells us, this is the ideal medieval society, one that is meant to be conducive to peace. That lack of social mobility and freedom that Hans has been chained by his whole life has a purpose: to ensure harmony.

But the script he's so used to, that he clings to so desperately, fails him. Harmony could not be further from his reality. Case in point, at the beginning he tells Henry that he can protect him with his name and therefore his own noble status:

But then, that doesn't turn out to be true. He does everything in his power to declare his noble status, to invoke his name, even places his arm behind his back and attempts to bow in order to properly present himself as nobility to the guards at the Trosky Castle gates—all for naught. No one cares. Hans tries so fucking hard to stick to the script he's been taught his whole life, and no one gives a shit. Svatya makes fun of him, refuses to apologize, and then physically assaults him. Instead of seeing Svatya getting clapped in the pillory, he is.

During the divorce era, he once again tries to grasp for any amount of familiarity from his old life by turning to hunting. It's a noble sport and something he's good at. Camping and going out to hunt, being out in nature over an extended period of time, these are all things he's done before. Things he can comfortably fall back on. If he forgets about the fact that he's alone—no Henry, no horse, no hunting dogs—he can almost pretend he's back in his old life.

Even his attempt at romancing Enneleyn at the wedding fits into this desperate attempt to cleave to his understanding of his noble title. (This is a point that also crops up in this fantastic analysis of Hans' character by @codeword-art, that Hans knows what people think nobles should be like, this including a love for women. This post and the one that preceded it are analyzed in greater depth in part two of this analysis.)

And then even that is torn from him when he's told he'll hang for poaching. Nobility was the one thing that was supposed to act as a get-out-of-jail-free card for him, his guaranteed fallback. Nobility was meant to remove the noose from around his neck... and then failed to do so. What's the point of being a noble if no one believes that you are one? What's the point of being a noble if it only comes with a lack of social skills, a lack of relationships, and a lack of freedom? What's the point of sticking to a script if everyone refuses to play their parts? Growing up, nobility always acted as a panopticon for him, surrounded by people's judgments of him. His character, his aptitude, was always everybody's business. But that pain, that judgment, always came with benefits before.

This illustrates for Hans, quite clearly, how quickly those benefits can be stripped for him and made meaningless. Nobility can't save him. Nobility has only ever taken from him, and then, when he needed it most, it wasn't there for him as a parachute.

At the end of Next to Godliness we can talk to Hans about what he's going to do with Arse-n-balls. And if Henry advises Hans to punish him, first Hans tries to defend him.

At which point Henry invokes his noble status and suggests that letting this transgression go unpunished would lead to people questioning him in his position:

At which point Hans folds quite quickly:

How much do you reckon Hans' worldview was shaken in hindsight, upon realizing the reality of the punishments he might have subjected people to. A day in the stocks or pillory? Being hanged for poaching? Suddenly he's seeing these things from the perspective of a peasant and what that might feel like.

Nobles are meant to protect people and dole out punishments only when necessary. But this whole system is so easily upended the second corruption gets involved.

He's next confronted with this issue in a big way if you decide to sell out Olda and go to Semine with Hashek. Despite von Bergow's wishes, Hashek wants to burn the place down to the ground along with all the people in it. Everyone is to die. This isn't what von Bergow wanted (and if you do agree to Hashek's plan, he is appropriately outraged after) and while Hans questions if the two of you did the right thing if you decide to go against Hashek's wishes, he's quite distressed if you don't go against his wishes and kill everyone. It puts him into a funk for quite a while after and leaves him viewing himself as inherently tainted by the experience.

Horrified as he is that Olda, as a nobleman, would side with Zizka and co (and expresses this right after the possible torturing if the truth is discovered), he's just as horrified that Hashek, a nobleman, would order the slaughter of innocents. He objects on several occasions but mostly goes along with what Henry says, only questioning what the right decision was after.

Nobles are supposed to be better than this. If he was expected to do better, to be better, to live up to all these unachievable ideals, why does no one else give a shit?

The next time this crops up in a big way is after the Maleshov rescue when Hans become quite upset at the sight of a destroyed village. A conversation with Brabant follows that showcase a number of Hans' feelings on the matter:

This is unjust, he says. Because in his eyes, the nobility should be above such dirty, underhanded tricks to get what they want. Brabant insists that the village will be resettled before long ("people die, it's what they do" etc etc) and that this is just how war is.

Hans, however, is unsatisfied:

Here too we see his idea of the Bellator and what that means for him as a noble. In Hans' eyes, their job is to protect the common people. To do everything in his power to make sure that these atrocities don't happen.

If Henry then agrees with him, Hans says something else telling (regardless of what happens with Semine):

These things happen because of his failure. He's a Bellator, a noble who should be capable of protecting people. Instead they failed at Nebakov and he was captured. The death of these people, to Hans, is on his own head.

We know that our boy Luke lost rizz points with pretty much everyone because he decided to burn down the village near Maleshov during the siege, but this too is a moment that's worth remarking on. In the moment, Hans defers to Henry and insists that well, they're in a war, aren't they? But after von Bergow's interrogation, he has quite a few things to say to Henry:

On the flipside, if Henry goes against Dry Devil, Hans praises his actions while simultaneously acknowledging that he wouldn't have been strong enough to do the same:

It's interesting that at this point in the story he trusts Henry (not a noble) with ethical judgments far more than either himself or other noblemen. Deferring to Henry isn't entirely new for him, but that's another post entirely. What matters here is that we're witnessing the wool being pulled from Hans' eyes in real time here: the inherent superiority of nobles is rapidly evaporating.

In addition to that, the fact that he's constantly put into the position of damsel in distress means that he's frequently saved or protected by Henry. He's not the Bellator of his own life. Henry is. Henry is more noble in Hans' eyes than any noble he's ever met. This even comes up at one point early in the game, following their first romance option:

I'm sure I don't need to point out how this means that Henry effectively dismantles Hans' sense of self only to build it up again. All his self-esteem was rooted in the fact that he's a capable Bellator, a defender of the people and worthy of his position as a noble. Then Henry comes in, does it all better despite his peasant upbringing, and then shows Hans that he has value in spite of what he perceived all his faults to be.

Even before the siege on Maleshov, Hans is slowly starting to build up an increasingly robust view of himself as a Laborator. I talked about this in more detail here, where we see Hans volunteer himself for manual labor that we see no one else in the game do other than Henry. In fact, it's something that is often (and jokingly at that) offloaded onto Henry. But here, Hans presents the far more noble position (in this case, dealing with the hunted game) to Henry while taking the manual labor task for himself.

With what noblesse oblige is Hans left with then? Stripped of all the artifice, what remains?

Just his word. The word of a nobleman.

Hans and Henry both get into an argument with Hanush at the end of KCD1 when he gives Toth his word that his safety will be ensured if he lets Radzig and Lady Stephanie go. Henry is (understandably) upset that Hanush will just let Toth go, but Hanush insists that his word as a nobleman is his bond. At which point Hans steps in to argue that they may as well not honor that bond:

Henry also argues, but Hanush ultimately comes back with this:

It's a point that sticks with Hans, and we see it invoked fairly early on in the game:

It's also challenged right toward the beginning as well. Henry responds to what Hans says with something that makes no sense, invoking the idea of one's word but here in the name of him being a blacksmith:

@antivanwine14 recently made a spectacular post about precisely this. There's no such thing as the word of a blacksmith. It doesn't carry the same weight whatsoever. But Hans decides to take it that way regardless:

No pretension, no posturing about the importance of a noble's words over those of a peasant. Either Henry has been elevated in Hans' mind (no doubt) or nobility is losing the special, unique lustre that it might have once held for him (almost certainly true as well).

We fast-forward a bit. His next encounter with the word of a nobleman is at Raborsch, where his word is given... for him, when he's engaged against his will. If you ask me, this changes things. In a big way. Hans has very little, but the one thing that he thought he had was his word to give. Every thing he swears by from that point forward serves as a reclamation.

And the first thing he does with that reclamation is swear that he'll be there for Henry just as Henry was there for him:

(and then he did, etc etc)

I do find it curious here that he doesn't invoke the word of a nobleman here in this promise to Henry. Instead, he swears by God, their mutual belief system. Giving Henry his word isn't enough anymore. As if Henry has outranked it in his eyes. I wonder if he thought back to the moment when Henry responded to Hans' word as a noble with the word of a blacksmith here. Unlike social stratification, this is a place where they are on equal footing.

The next time that Hans does give his word is at Maleshov during the siege: von Bergow's safety in exchange for both Rosa's safety and von Bergow's agreement to switch sides.

This makes sense. He's speaking to another nobleman here, someone who would understand what it means if the word of a noble is given.

And it is, of course, then immediately put in danger by Sam:

If Sam kills von Bergow here, he takes the last remaining vestiges of any sort of sense of self or identity from Hans. Nobility is losing its lustre, he's not a worthy Bellator and instead always has to have Henry saving his ass, and this is all that remains. What is a noble without his word? As Hanush told him very clearly at the end of the first game, his word is his honor. And without honor, he's nothing.

What's left if the artifice is stripped away? If all he has left to him is his word, if that too is rendered meaningless, Hans, in his mind, will be left as nothing.

It should also be noted here that Sam is not held back by the rules of this society that Hans is so solidly part of. Much like queerness, he exists well outside of it, as both Jews and sodomites were considered heretics. Sam has that freedom that Hans so badly longs for, but it comes at a considerable cost, that of oppression. It's risky to exist at the fringes of society.

As @hallowedlore perfectly put it (in private conversation), when Sam attacks von Bergow, a statement throwing into question why he should care about the rules of their fancy nobility, the only thing that stop him is the threat of violence from Zizka. Death, not social decorum.

Hans is clinging on to this bit of identity with all his might here as though it's a life-raft. And Godwin immediately backs him up, reminding him that what he did there mattered.

But it doesn't get him very far. And certainly not with Sam, who couldn't care less about pleasing a Christian god. It strikes me as curious (and topical) here that he comes away from the big roundtable discussion with von Bergow and the other nobles feeling like insignificant shit while their talk at the Devil's Den did not leave him feeling that way.

Being a nobleman was meaningless here too. His nobility didn't matter one bit, all that mattered was being the strongest personality in the room. And Hans is anything but that. That boy is made of insecurities, his outward facing personality all a mask behind which is only hot air.

Only his jealousy regarding Sam's inbuilt relationship with Henry makes him turn back to old patterns:

See, Henry? He's different from us. But the argument doesn't work on Henry and barely even works on himself.

Increasingly, Hans realizes that the nobility isn't where he feels like he belongs the most. This worldview of his is fucked and all wrong. Who went and decided that he should be a Bellator while someone like Henry isn't?

Because he does associate Henry with nobility in a big way. When Henry goes to ask Hans what he should do about Erik's offer of a duel, Hans thinks it over and then comes back with this:

These are different times. Are they? Or is it just Hans' heart that has changed here? Because right after this, he asks Henry to stay. To forgo honor and nobility and not put himself in unnecessary danger.

The aftermath of the silver heist likewise serves as a painful reminder of what is waiting for him on the other side of all this: a marriage that he doesn't want to a woman he doesn't know. What benefits remain of nobility? All he'd see by this point is obligations. No one listens to him, no one cares what he has to say except for Henry. All the bluster is ultimately meaningless. He doesn't belong with the other nobles, and all his best attempts at fitting into the mold fail him. All his life he's spent his time trying to be like those around him, trying to be someone he isn't, and it's never good enough.

The people he feels most comfortable around, Henry and Godwin, are both people with ties to nobility while wanting as little to do with titles and related obligations as possible. They both have social mobility to a certain extent. The opposite of nobility, to Hans, is freedom.

Shorty after the attack by the Praguers, Hans goes to wait for Henry in front of his room. When Henry asks him how he's doing, because he's clearly got experience leading troops, Hans laughs it off:

If there was any doubt left that he views himself as an incapable Bellator, this is excellent proof, backed up even more later on following the suicide mission:

This is what being a noble has gotten him. People's judgments and expectations, obligation to marry and carry on a family line, and the ability to play God and decide who gets to live and who dies. All he wanted was to protect people. Instead he gets to send them to their deaths.

This will come up again in part two, but it bears mentioning here as well. After getting laid, Hans vents to Godwin about how much he hates that no one ever treats him like an adult. He's a noble and an adult, and none of it ever seems to matter:

Who's "they"? Because the rest of what he says mentions that he thought the Trosky delivery would make "them" take him seriously. This isn't just about Hanush. This is about all nobles. That he'd finally fit in.

But he doesn't, and he won't.

When Hanush arrives at Suchdol, he highlights that everyone there is a hero for their deeds there, but it doesn't matter. Hans once more has his noble obligations shoved down his throat, which effectively feels like the last straw in this disillusionment. Nobility has granted him nothing but pain and any child of his would suffer the same fate. There's even some easily missed idle dialogue you can walk in on where they're arguing about precisely that. It doesn't matter what he does, how heroic he is, how many good deeds he performs, at the end of the day none of it ever mattered (read left to right):

It always strikes me in that conversation how unbelievably bitchy Hans sounds here. The "I'm glad you noticed" could not be cuntier. He is not happy. And even then, Hanush barely offers him any guarantees.

Effectively, this leaves Hans open to questioning the harmony of society as it was taught to him and, in questioning it, realizing that that harmony never existed to begin with. He spends the whole game realizing that the social order he's been subjected to and thought he fit into perfectly is not only illogical but also something he has despised his whole life. This is discovered not only because he was shown an alternative in his own shift into more of a Laborator beside Henry (who to him embodies the qualities of a Bellator far better than he), but also in his own queerness.

It doesn't escape me that there's something to be said about Suchdol here. During the siege, Henry and Hans effectively live outside of the bounds of nobility or social stratification. Everyone is equal in the face of Hunger and Despair. And it's only in this space, this place outside of what is and isn't deemed acceptable by society, that Hans finds it in himself to kiss Henry. To breach every code of conduct he's ever known. Because they're already in the space outside of social acceptability. Hell, the entire Devil's Band is situated in precisely this space just by going against Sigismund. You couldn't ask for a more perfect environment for Hans to step outside of the bounds that have held him since birth.

This is even shown even more starkly with this anon's point in mind about how it goes if you don't romance Hans:

This is unjust. Henry is only in danger because he's not a noble. There's something to be said about agency here, but that discussion has to wait for part three of this analysis triptych. Nothing about this social stratification serves him any longer, all the more so when he romances Henry. It's also why he seems so uncertain about the two of them when Henry returns, and they are meant to return to reality and the expected social order.

This social order that was meant to bring with it harmony for all is the same social order that would demand that he marry and beget an heir. Why should he try to fit himself into this cookie cutter mold if he never fit to begin with? As we see with Barnaby especially, being discovered as queer spells an existence at the fringes of society if not outside of it entirely. Queerness is inherently and by definition at odds with social order, thus returning us to the nobility vs. freedom dialectic. And regardless of which of the two Hans ultimately chooses, obligation or what his heart wants, that disillusionment can never be undone.

Part 2, Part 3

#hans capon#hansry#kcd#kcd2 spoilers#kingdom come deliverance#kcd meta#it's possible this will change from being a triptych to a quadriptych#or maybe... a polyptych#because there's still more I could say here 🤡🤡🤡#even after writing three posts like this#anyway again I APOLOGIZE this is like... thesis length#I am so sorry#how does this KEEP HAPPENING

230 notes

·

View notes

Note

17

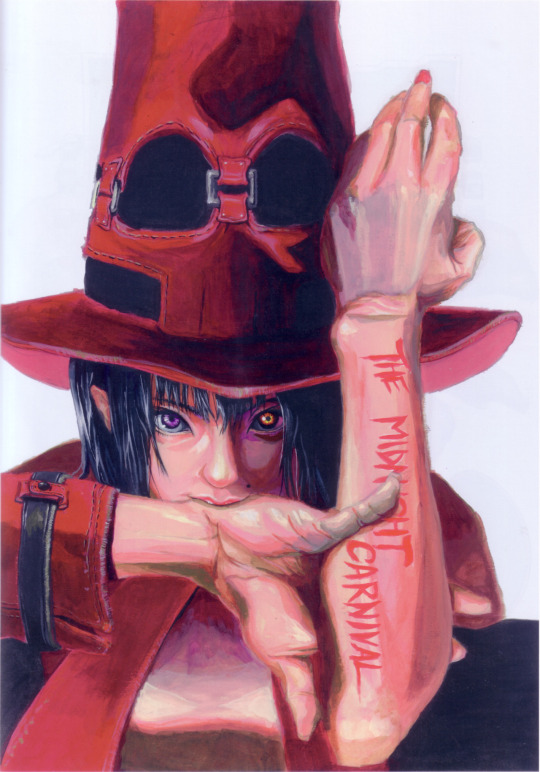

17. What inspires you?

i love getting this question because i get to show off my favorite pictures ever.... anyway

i think its fairly evident but in general fighting game art has been so important to like. my art progress in the past 2-ish years i feel. and also how i do character design kind of. im just pulling random pics i have saved to my puter but old gear art in particular has something special about it wrt posing and composition... i already drew stuff along those lines before getting into fgs seriously but finding art like this definitely streamlined it into something more intentional and coherent

another huge inspiration is just old raytraced environments. tragically this account went defunct a few months back but i still love scrolling through its media tab sometimes still... it always gives me the biggest creativity boost. some of my favorite pics ever are these two i feel the influence here kind of shows in the way i draw abstract backgrounds with copious patterning most of the time

uhhh uhhh dont have any images with sources on hand but generally saying any 'wonky' imperfect mspaint art of a character just posing and looking cool. fucking love that stuff. i love the stilted perspective and shading and weird shapes that comes with old art along those lines.... i like incorporating pastiches to that with how i do weird angles and patterns and whatever

not a visual thing but uhhh no doubt the music i listen to inspires a lot of my art. its something thats hard to describe and maybe its just me thinking about it too hard but aside from like often incorporating album covers and lyrics into my drawings i just follow a lot of the 'philosophies' of the genres i like wrt how i create art myself. like 'who cares if somethings too cluttered or weirdly discordant what if you bring that to the forefront and intentionally play on complex composition to create something cool. make a single piece thats basically a polyptych. layer a dozen things over one another. whatever'. when i listen to prog my ears are busy and so the images i make must be too

also vague answer but i just like the art my friends make and it always inspires me to make cool stuff. 👍

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Different Thread, Chapter Eighteen:

Polyptych

Bum shook his head. “ Fine ? Things can’t be fine. Why else would you drink? And how did you do that?” he asked, prodding a finger in the direction of Nakyum’s forehead.

Without thought, Nakyum reached for the spot Bum was pointing out, feeling grazed skin. He’d rushed so fast this morning to get ready he hadn’t had a chance to look in the mirror. He’d hurt himself, falling out of the car. But that wasn’t what made his pulse quicken or his cheeks heat. There had been a kiss that Nakyum hadn’t been repulsed by. Why hadn’t he reacted?

“Oh, this? It’s nothing. I just bumped my head.”

Bum clicked his tongue. “The first time you get wasted, and I’m not there to witness it?”

“Trust me. You wouldn’t have wanted to,” Nakyum mused humourlessly. He considered then that he had to be honest with Bum if he wished Bum to be honest with him. “You’re right. It wasn’t a good night, though the presentation was great— amazing , actually.”

“Of course it was; you wrote it,” Bum sniffed.

Acknowledging the warmth that came with his friends never wavering faith, Nakyum nevertheless waved the notion away with a hand. “He didn’t credit me once in the presentation or the online article. Considering how many people attended, it will be spoken about and circulated, and I am completely invisible. He will get all the credit.”

Bum was slack-jawed. Evidently, even his pessimistic opinion of Nakyum’s teacher fell short of that level of betrayal. “He did what?”

“Don't look surprised. You’ve been trying to warn me about this for ages now.” It wasn’t so bad, Nakyum supposed, admitting you had judged wrongly.

Dropping his gaze, Bum looked sheepish. His wide and dark eyes were so full of sorrow they looked like pools. Nakyum hated it when he looked like that. Of course, he wouldn’t gloat in being right; Bum wasn’t that sort of person. “I’m still sorry. I’d hoped maybe I was making something out of nothing and be wrong about him. You don’t deserve this.”

Read more here…

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

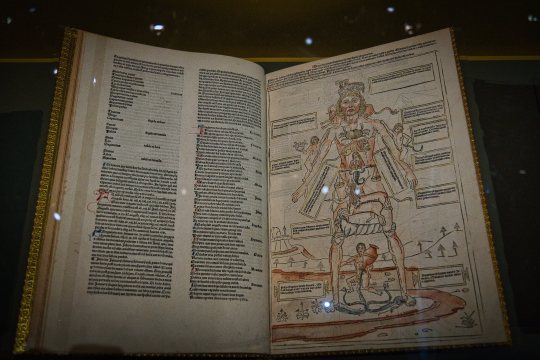

Picture 1 (Giant book)

Fasciculus medicinae by Johannes de Kethman, 1461

Picture 2 (Red)

document case with the arms of Borso d'Este around 1452/1471, maybe by Ferrare

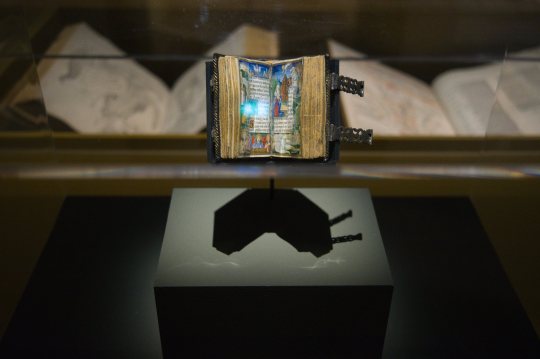

Picture 3 (Tiny book)

Officium parvum Beatae Mariae by Giovan Pietro Birago, 1494

Picture 4

A Tempera by the Master of the polyptych of the chapel Médicis between 1315-1320

#Fasciculus medicinae#johannes kethman#document case#old books#tiny book#XIV century#XV century#luminar4#photographer on tumblr#polyptych#aixenprovence

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Who do you think is more powerful and why: DMC Dante and Vergil or DmC Dante and Vergil?

Interesting. Well, you’d have to analyze that comparison from multiple axes, I think - it can’t be asked straight across or decoupled from context, especially as the two iterations of the Sons of Sparda story exist in universes with some pretty notable differences.DMC Classic is a surreal, lavish neoclassical fantasy where everything is exaggerated and overpowered for sheer hyperbole and bombast. Swords can be unrealistically enormous ironing boards and still present no logistical or physics issues for Dante; Vergil can cut bullets in half in midair, arrange them like antipasti, and serve them back at his opponent like a sous chef.

It seems to take place in an idealized generic Western European Everycity. Maybe sort of like a Rome, but London or Bruges or Budapest or Brasov would look much the same - it is reminiscent of any city with an old town, and the Japanese developers liberally borrowed all the urban Western European stuff they liked: London’s red double deckers and phone booths, for example. Italy is hinted at, by context, but never confirmed. We know it’s not landlocked, in any case - and that whatever body of water it adjoins is large enough to encompass an island.Technology exists, but is arrested at a certain point of romanticized classical modernism: they have cinema (we see movie posters), but not television (though I suppose it’s possible it exists - all we know is that Dante doesn’t have one). They have rotary telephones, but not cell phones. They have motorcycles and guitars and amplifiers and jukeboxes, but not computers. Nico can craft sophisticated motorized prosthetics and weapons, but they seem mechanical, not digital - predicated on servos and leverages and explosive propulsions.It makes sense for technology to be quainter in a fantasy-reality fusion series, where most of the characters’ powers will come from magic.ReDmC is a more grounded, grittier fable, with a cyberpunk/tech slant; more pop art bildungsroman and less baroque polyptych - (though to its credit, it pays homage to its neoclassical ancestry and DMC DNA in some really sublime interstitial set pieces and still lives).It also takes place in a Western setting, but this time it’s the New World, the new West, and a decidedly North American depiction. It could be emblematic of either coast; Dante’s trailer by the carnival looks suspiciously like Santa Cruz/a So-Cal pier, but could also be like Coney Island. The city is a little dystopian, with general elements that wouldn’t be out of place in either NYC or LA, or any major metropolis: again, a generic idealization, liberally borrowing whatever appeals.The world we see in ReDmC is anchored in a slightly more modern, realistic depiction, so in some ways, the brothers’ powers (at least in story/cutscenes) are also scaled down slightly in scope to better match this aesthetic. Technology-as-magic plays a slightly bigger role here than classical magic, which is diminished a bit, which makes sense in a sci-fi/reality fusion series.But we also have an interesting wrinkle: the brothers aren’t human at all. Rather, they’re the offspring of two juggernauts - two breeds of powerful nonhuman being - one celestial, one infernal. This suggests that, unlike Dante and Vergil, ReDante and ReVergil are wholly unfettered by powerless humanity at all - they resemble humans in image only.Also, canonically, this hybridization/abomination seems to have an exponential, compounding effect larger than the sum of its parts: a Nephilim is a being *more* powerful than the average angel or demon, (having been historically hunted down and exterminated for precisely this reason) - and the only being on earth capable of killing a demon emperor like Mundus. (Again, as in DMC Classic, we have the concept of identical twins: two bodies inhabited by one cloven soul, which is sort of used to explain why neither brother can manage it alone.)Their updated heritage all makes sense with the proviso tacitly set forth by Capcom when instructing Ninja Theory on how to handle Reboot: “IT HAS 2 B MOAR EXTREEME!!!111112″Of course Dante and Vergil couldn’t just be half demons, man - they have to be something even more intense.(Which interestingly also removes a lot of Sparda’s motivation for giving a fuck about humanity - if his wife isn’t human, then the human world just becomes a witness protection place for these two to settle down - not necessarily anything either of them are particularly sentimental about or magnanimously invested in. This difference is something that I play with in my Reboot fic, since it’s so much more ambiguous. Dante’s sudden decision at the end is thus entirely his own emotional impulse, and Vergil’s lack of trust or appreciation for humans’ self-governance becomes less a refutation of his own nature, and more the measured conservationist philosophy of someone who has observed a lesser taxonomical species his whole life, seen how easily they became enthralled, and determined they shouldn’t be left to their own devices, or they’re liable to extinct themselves in short order.)There are a couple of other considerations:First, we have to compare ReTwins solely with 3Twins, because that’s the parallel property, timeline-wise, and we only have one DmC game to canonically go on.Second, while I love ReDmC, it can’t be denied Ninja Theory was a little half-baked with producing a through-composed theory of narrative, and the inconsistencies their badass! changes would create in the original lore, which was fairly comprehensive, careful and well-considered. So there are some loose ends and threads here and there that can’t really be reconciled either with the original, or even with ReDmC’s own internal logic. Within the context of their own respective worlds, I think ReDante and ReVergil are *depicted* as more underpowered in their setting than classic Dante and Vergil, but *scripted* as more powerful, interestingly enough. On paper versus in practice.I would venture to posit that either set of twins would probably find themselves at a sudden disadvantage in the others’ worlds.So I feel like it’s something of a push, functionally, with narrative goals and the emphasis on “power” being shifted compensatorily depending on the context and the story being told, but ultimately having the same atomic weight, even with different ratios of components, if that makes sense - - and that the answer would vary quite a bit depending on the parameters the question was asked under.I feel like such a dork for ruminating this much and writing such an exhaustive reply, but then again, this is what we do, right? This is our brand. Anyway, what do you think?

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Meditations on [a Part of] “Leibliches Hören und sein Knecht” by Philipp Simon & Lukas Quietzsch

By James D Bowman 3

It’s not impossible to read this as comix, as an abstract strip (each door a panel) or graphic novella (doors as chapters, slats as panels) and to be led into at least a part of the socio-spiritual heart of comix, comix-as-a-kind-of-consciousness, which creates a taste for itself. To “read” sidewalks, for instance, chalk-blotched and gum-pocked, and to see, as John Cage heard sweet symphonies in the sounds of traffic,1 the stories that secrete themselves out of sheer chance into our world of interpretation and iterability, is edifying. Francis Bacon’s reluctance to see Velasquez’s “Portrait of Pope Innocent X” in person, “in the flesh” (despite or because of his obsession with it, its inspiring him to produce many paintings) is an intriguing inversion of what Derrida calls the metaphysics of presence: Bacon was as interested in ABSENCE, which his art reveals, as Deleuze elucidates beautifully.2 I have no such reluctance with regard to the Simon and Quietzsch work, but I will assert it’s my prerogative to encounter it like this, as is, as a photo, knowing something (maybe much) has been lost in translation, and that (metaphysics aside) there’s power in presence, presence packs a punch. It’s THIS, though, this PHOTO, this abridged iteration, which I read (and more easily than I’d read it in person) as an abstract comic, a strip with (if it’s read from left to right) an upward tilt, subliminally signifying optimism. The “Z” shape repeats, majuscule, the great governing glyph with which a reader must concern herself, suggestive of sleep, somewhat Gethsemanesque: the disciples doze in the garden of Christ’s agony; a shield of slumber behind which to hide, hiding from thoughts of the lumber beyond the slumber—yea, even the lumber of the cross. And it is in this sense that the doors serve as a sort of polyptych, a “trace” (in the Derridean sense) of the art-historical, of the classical, the palpably religious. But aren’t doors also shields, as walls are (at least from the elements)? And what is it these protect, these doors, these panels of our polyptych? They shield us, at least, it seems, from the unbearable blankness of the wall, its barrenness and sterility, the colorlessness of the clinic. They shield themselves from themselves, as well; an impasse or stalemate, “protecting” themselves from the rest of themselves. The boards that form each “Z”, for instance, zigzag and so, since zigzags manifest neurotic energy (as squiggles manifest erotic energy), we get the sense that the Z’s are a sort of reaction formation; that their horizontality and diagonality are the useless pseudo-refutation of those vertical beams behind them—which they CLING to nevertheless, an elegant yet bare abstraction of ambivalence as such. Yet, like a house, a shield divided against itself cannot stand, or protect itself (or us) from much; therefore all the indications of wear and tear, therefore that gap in the fourth door like a missing tooth. The doors do not allude to youth, and are far removed from rejuvenation—but not from reverberation. Each seems to me to be an imperfect echo of all the others, an echo altered, instilled with minimal differences. Truly a numinous contribution to comix as an abstract art.

1.

JohnCageahudby. “John Cage - About Silence and Traffic.” YouTube, 21 Oct. 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H-Xy-gAaOzw

2.

Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation. New York, Continuum, 1981.

#comix#comics#abstract comics#abstract comix#gilles deleuze#john cage#francis bacon#art criticism#jacques derrida#aesthetics#james d bowman 3

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Master of the Death of the Virgin (maybe also known as Joos van Cleve) - Death of Mary - ca. 1513

Triptych with on it: Saints George and Nicasius, with the donors Nicasius and Georg Hackeney. The death of Mary. Saints Christina and Gudula, with the wives of the donors, Christina and Sybilla Hackeney.

The Death of the Virgin Mary is a common subject in Western Christian art, the equivalent of the Dormition of the Theotokos in Eastern Orthodox art. This depiction became less common as the doctrine of the Assumption gained support in the Roman Catholic Church from the Late Middle Ages onward. Although that doctrine avoids stating whether Mary was alive or dead when she was bodily taken up to Heaven, she is normally shown in art as alive. Nothing is said in the Bible about the end of Mary's life, but a tradition dating back to at least the 5th century says the twelve Apostles were miraculously assembled from their far-flung missionary activity to be present at the death, and that is the scene normally depicted, with the apostles gathered round the bed.

A virtuoso engraving by Martin Schongauer of about 1470 shows the Virgin from the foot of a large bed with the apostles spread around the three sides, and this composition influences many later depictions. Earlier depictions usually follow the standard Byzantine image, with the Virgin lying on a bed or sarcophagus across the front of the picture space, with Christ usually standing above her on the far side, and the apostles and others gathered around. Often Christ holds a small figure that may look like a baby, representing Mary's soul.

A prominent, and late, example of the subject is Death of the Virgin by Caravaggio (1606), the last major Catholic depiction. Other examples include Death of the Virgin by Andrea Mantegna and Death of the Virgin by Hugo van der Goes. All these show the gathering of the apostles around the deathbed, as does an etching by Rembrandt.

Three minor anonymous artists are known to art history as the Master of the Death of the Virgin.

A triptych (TRIP-tik; from the Greek adjective τρίπτυχον "triptukhon" ("three-fold"), from tri, i.e., "three" and ptysso, i.e., "to fold" or ptyx, i.e., "fold") is a work of art (usually a panel painting) that is divided into three sections, or three carved panels that are hinged together and can be folded shut or displayed open. It is therefore a type of polyptych, the term for all multi-panel works. The middle panel is typically the largest and it is flanked by two smaller related works, although there are triptychs of equal-sized panels. The form can also be used for pendant jewelry.

Despite its connection to an art format, the term is sometimes used more generally to connote anything with three parts, particularly if they are integrated into a single unit.

The Master of the Death of the Virgin was an Early Netherlandish painter active between 1507 and 1537. He is believed to be responsible for a large group of paintings; two of these are altarpieces of the Death of the Virgin, one in Cologne and one in Munich, from which his name is derived. He is sometimes, but not universally, identified with Joos van Cleve. Nothing further appears to be known about him.

Joos van Cleve (also Joos van der Beke; c. 1485 – 1540/1541) was a painter active in Antwerp around 1511 to 1540. He is known for combining traditional Dutch painting techniques with influences of more contemporary Renaissance painting styles.

An active member and co-deacon of the Guild of Saint Luke of Antwerp, he is known mostly for his religious works and portraits of royalty. As a skilled technician, his art shows sensitivity to color and a unique solidarity of figures. He was one of the first to introduce broad landscapes in the backgrounds of his paintings, which would become a popular technique of sixteenth century northern Renaissance paintings.

He was the father of Cornelis van Cleve (1520-1567) who also became a painter. Cornelis became mentally ill during a residence in England and was therefore referred to as 'Sotte Cleef' (mad Cleef).

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Dan,

I want to tell you some thoughts on a fragment called “The Last Judgment” accredited with Hieronymus Bosch.

The painting was first recorded in 1822 as part of the collection of the Städtliche Gallery in Nuremberg. Later on, it came in possession of the Bavarian State Painting Collection, which also belongs to the Alte Pinakothek.

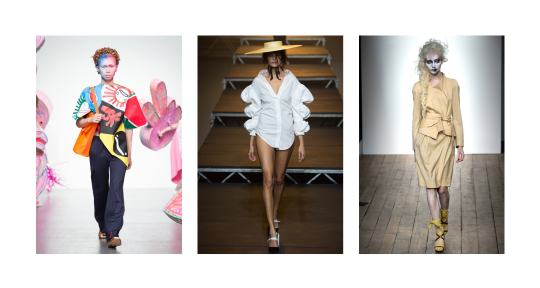

This fragment painted on oak wood was found 1817 (about 400 years after its production!) in the depot of the Nuremberg Castle in Bavaria. The original must have been huge: the dimensions of the fragment are 60cm x 114cm! It is supposed to be the lower right part of a triptych, if you look at the very bottom left you can see a big amount of dark blue fabric, this is said to belong to a great, standing archangel Michael. In that case, the painting would look as followed: at the top Christ as a judge, underneath him Michael weighing the souls, to his left, the resurrection of the elect, angels leading to heaven, and to his right the saved fragment: the damned, demons dragging them to hell. This structure was quite a typical one for the 15th century (check out below the polyptych of the Last Judgment by Rogier van der Weyden). It wasn’t even known for a long time if Bosch painted it or not –the new consensus is that it’s painted by an anonymous Bosch follower. This fragment displays the immense popularity and relevance of Bosch for the painters of his time.

What I find so exciting about this painting is not only its visual appeal, the content is so overwhelming: it depicts in a way a “hell on earth”, a system of the afterlife on our world, a visualization of dystopia in our future.

We know that Bosch was rather conservative, he belonged to this re-moralist brotherhood in his hometown and nearly never left the village he lived in. Most of his commissioners were catholic royals and his paintings said to depict the horror people would suffer in hell - a very creative horror though. The goal of his paintings was to depict this hell and create fear inside of the observer and therefore behave more morally correct. Nevertheless today his paintings fulfill some sort of different role, we find them amazing and fantastic, many see them as the pioneering precursors of the surrealist paintings and find similarities between Dali’s and other surrealist paintings and Bosch’s. It makes sense if I was a little Dali boy and would see one of this paintings I would’ve also been heavily inspired!

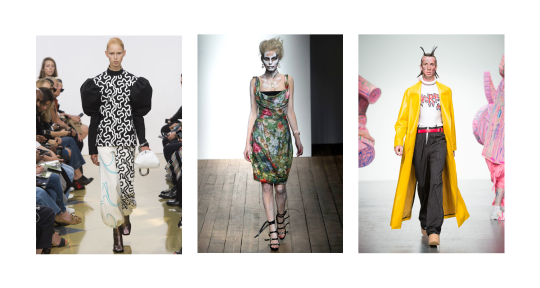

Even though most of his figures appear nude, the aspect of metamorphosis, collage of elements and transformation is highly linked to fashion design. In a way, I could see modern designs by JW Anderson, Jacquemus, Craig Green, Charles Jeffrey Loverboy and the likes popping up in his paintings. Bosch’s sceneries also remind me of big fetish parties from bird-perspective: people in weird costume next to naked women and men, all in rather experimental, almost painful poses, creeping around, in dream-like landscapes. Several Designers used his paintings as prints and inspiration for their creations, among them also Lee Alexander McQueen in his very last other-worldly collection.

I will describe a few of my favorite figures in this painting. On the left side of the painting, we see about 10 naked people crawling up from holes in the ground. The holes are dark slits, the earth seems to be spitting out people. Among others, we see a pope, two royals and also a priest or pastor, all identifiable by their headgear. The ground is hissing out flames. On center top we can see a green-ish demon, its spine-bones are bunching out strongly, its butt towards the viewer. Two big wings span from its back, a mix of butterfly, moth, and bird, very organic and delicate. It is looking at us, with big black shiny eyes. Kind of a cocky face expression. With its mouse or fox ears, it resembles a bat-demon somewhat. He’s farting on a tortured soul. Not far from it we can see a rather elegant humanoid bird-creature. It has legs and hands of a human and head and tail of a bird, the tail turns into something lizard-y. Its bulky body covered in a long yellow gown, with typical medieval sleeves, wide and long, adorned with white feathers at the hem. With a long metallic rake at hand, it seems to be pulling humans out of the soil. Underneath it, we find two rather funny promenading individuals. The first one is an old guy with a white hood around his face, to both sides of his head grow a few thin filigree feathers. Its facial expression displays annoyance or displeasure. The small body stands on four human feet and is shrouded in a blue cloak with white lace parts. A ridiculously big tail a la peacock-feather-meets-platypus peeks out from the cloak. The other figure has a slightly slimmer body shape. Its white skin is naked. The tail and head are of a mouse (or rat), the snout being very pointy red with extremely long white feelers. Its head is covered in a nun-like white cloth, crowned by a red pointy hat. It seems to have a boob, or an udder hanging from its torso. This weird figure is basically just standing there, quasi-hanging out in hell….

Next is a group of four dwarfs or ogres. These figures are very important because they wear oriental clothing and one of them bears the Turkish coat of arms symbol, the moon, on his turban. This is a typical symbol in medieval Christian painting: the Turkish as representatives of the whole Arabic world and Islamic culture, and furthers representing the bad, the evil enemy and the devil. In the very center of the painting, we can see a monster which looks like an explosion. It has no head, instead two tails at the bottom and top of its body. The colors from its skin and wings are fancifully chosen. This demon is brutally smacking a tortured person against the fire-spitting ground. The demons take charge of the dead, who are evidently being led off to hell!

All creatures and scenes shown on this fragment are illustrating the insanity reigning in the devilish hell, a huge chaos rules the world of the sinners and traitors and nobody is safe! The creatures appear as fusions and metamorphosed mutants, all shapes and forms are mingling, all colors and kinds are melting to creatures which take quite a while for our minds to process! The fashion creations in our current world are not far from this, they are wicked and weird, they are materialistic and abundant, exaggerated and extreme. Imagine if eventually, Bosch was just a visionary fortune teller, he might have had some sort of magical crystal ball streaming him live imagery from London or Paris catwalks and runways, providing him with endless inspiration for these Babylonian sceneries!? Or maybe he was able to peek through a future-curtain directly into the studios of the big fashion houses, he could see the poor tortured souls of the interns being maltreated by eccentrically dressed fashion fanatics! We will never know exactly how Bosch’s creatures were conceptualized, but don’t you believe my fashion-visionary theory to not be too far from reality?

text & image selection: Federico Protto

image sources: The Last Judgement (fragment), by Hieronymus Bosch: boschproject.org Polyphonic of the Last Judgment by Rogier van der Weyden: artbible.info First Bosch detail: pinterest.de Other two Bosch details: boschproject.org All runway images: vogue.com

#fashion & _______#fashion & catastrophe#catastrophe#fashion#hieronymous bosch#hyeronimus bosch#rogier van der weyden#art theory#federico protto#alexander mcqueen#charles jeffrey loverboy#charles jeffrey#jw anderson#craig green#jacquemus#vivienne westwood#federicoprotto

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

After having played back my old ten year old game pokemon diamond which marked me as a child, I decided to realise this polyptych in 4 parts inspired by stain-glass windows : This will allow me to make an hommage to this wonderfull game which celebrates (in my country) its 10th anniversary of existence. We will see the four pokemons creator of the world according to the Pokemon Mythology which was brilliantly developped in the diamond and pearl opuses. I used a thin black pencil, then I scanned and put the colors on Illustrator. I hope it will bring you back good memories, and that you will maybe play back to your old pokemon games.

Vlad.

#pokemon#pokemon game#pokemon diamond and pearl#pokemon diamond#pokemon pearl#pokemon platinum#plakia#giratina#dialga#arceus#pokemon art#fan art#stained glass window#vitrail#pokemon diamant#pokemon perle#pokemon diamant et perle#pokemon platine#polyptych#god#gods#mythologie#mythology#colorful#universe#anniversary#10th anniversary#20072017#legendary pokemon#pokemon legendaries

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

i didnt really plan to blog here but twitter really does make having a long rambling thought seem pretentious. that made me think of presentation though... for context?, i have a sideblog which is pretty girly and unpretentious (imo). i “wouldnt want someone to think that thats the fulle extent of my personality” (airquotes because it’s not that simple). but ime once you feel more comfortable with fluidity of expression (not masks, face(t)s (amorphous jewel!)) you dont mind presenting just the one side of yourself as much. you don’t fear forgetting yourself... or the judgement of others as much, but that’s a more obvious one. anyways, this is another unchecked-privilege paving over of the poor by the wealthy (wealthy/poor ””spiritually””. in self-knowledge... safety-in-self.).

(paving over, like stepping on, but sounding less obvious, more impersonal and systemically useful to a class)

the “wealthy” can afford, setting a standard unattainable... 1..n... polyptychal expressions.

the insecure, on the other hand

dogfucker anthem full volume, to paraphrase lili’s words. true-manspreadingly obnoxious or the crassness of a desperate attempt to not dissolve? yes, maybe you have to do it and get bored of it.

(a-n-them, a-na-them-a)

i want to read that thing i saw once about eating your shadow

0 notes

Text

Bill Viola

Last Christmas, I saw Martyrs at St Paul’s Cathedral in London. The work consists of four plasma screens, each showing a single figure who is progressively overcome by the onslaught of a natural force. Despite each person’s agonizing predicament, their resilience and deep seated beliefs keep them from conceding their fight. Viola explans that Martyrs are characterised by their human capacity to bear pain, hardship and even death in order to remain faithful to their values, beliefs and principles. They offer a contemporary contemplation on life, death and afterlife.

Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water), 2014 High-Definition video polyptych on four plasma displays, colour, 1400 x 3380 x 100 mm Duration: 7.15 minutes

I think that his use of video is very clever- He has this ability to transform complex concepts into subtle, zen-like videos through his mastery of this medium and timing. He captures the essence of human nature. These ideas are also explored in other works of his, namely Nantes Triptych.

This video, sound installation is made of three large scale panels of projected video. The left panel depicts a women giving birth, the right panel shows an image of an old woman in the process of dying. The middle panel displays a clothed man underwater movin g through alternate stages of turbulence and undulating stillness- he seems to be suspended in a void both in space and time.

Nantes Triptych, 1992

Video, 3 projections, colour and sound (stereo)

Duration: 29 min., 46 sec

The work alludes to a narrative of life- a beginning (the birth) and death (the dying woman). I don’t really understand the middle panel. I think the man in the middle looks as if he is waiting for something, maybe to transcend to something else? I think that Viola’s work is relatable to my works (specifically, D E C L I N E), in that viola explores the cycle of life (a beginning and end), however, he explores the more spiritual implications of this process. Also, he uses people as the subject matter and actually looks at life within humans, while I explore this life process from a material perspective. I think his use of video is something I want to strive towards. He uses video as an inner eye to explore existence in the form of real spatio-temporal situations. Through combining these videos, he transforms real situations into multi-layered units of supra-temporal audio-visual action. He creates different levels of consciousness. His artistic medium successfully transposes human experience into a visual. This level of complexity is so revolutionary to me. I also think this idea of life is something I can explore more in my own art practice.

Beadle, J. (2000). The embodiment of art. British Medical Journal, 321(7252), 57. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/204010487/

Carlos Vara Sánchez. (2015). Bill Viola’s “Nantes Triptych”: Unearthing the sources of its condensed temporality. Aniki: Revista Portuguesa Da Imagem Em Movimento, 2(1), 35–48. https://doi.org/10.14591/aniki.v2n1.105

Lauter, R., & Ammann, J. (1999). Bill Viola : Europäische Einsichten, Werkbetrachtungen = European insights, reflections on the work of Bill Viola . Munich ;: Prestel.

Viola, B., Sellars, P., Hoberman, J., Hyde, L., & Ross, D. (1997). Bill Viola . New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with Flammarion, Paris-New York.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Immanuel Wilkins, “Part 4: Guarded Heart” (Blue Note 2020) | Exceptional tune — actually the closing section of a 25+minute polyptych — on the lovely debut album by a young alto saxophonist with an excellent sense of melody and, at times, the meddle to lose himself in it. Not sure why it seems right to be listening to this repeatedly on the 25th anniversary of Jerry Garcia’s death, but there you go. Maybe it’s the fight of its flight, opened with a solo invocation by drummer Kweku Sumbry, joined by Daryl Johns’ feisty bass, pushed along by Micah Thomas’ piano and then picked up to the finish line by Wilkins himself, with the band positively smoking behind him. The melodic nature of the overall composition is never lost here, even as the musicians push each other towards a purer and purer mode of ensemble expression (approximately 3:30-6:30). The spirit is old, invoking generations, but the playing is fresh and exciting, making connections.

0 notes

Photo

Photographer: David Hilliard Website: http://www.davidhilliard.com http://www.yanceyrichardson.com/exhibitions/david-hilliard2 Bodies of Works: 1) Being Like 2) The Tale is True David Hilliard’s photographs are mainly devoted to documenting his own intimate life, particularly the subtle relationship between him and his father. Works of David Hilliard are usually presented in forms of diptychs or triptychs. To me, polyptych is an unusual but very powerful way to present images. Compared with the single picture, polyptych gives viewers a more comprehensive and complicated view of a story: It expands the view beyond the frame of a single picture. In David Hilliard’s pictures, there are always some unexpected elements happened simultaneously but outside the single image. For example, in Feeding Gretchen, one will never know the father is secretly feeding the dog under the dining table until he sees the lower image. In my opinion, the polyptych methods kind of endow a piece of work with a dynamic or rhythm. As one moves his eyes from one panel to the other, the story also starts to flow. In both Being Like and The Tale is True, David Hilliard adopts the multi-paneled way to present his images. Being Like, as Yancey Richardson Gallery introduces, is a self-portrait project of Davide Hilliard, which presents a boy’s physical and emotional experiences in various ages. There are two images that I found very interesting. One is called Boys Tethered, the other one is Rock Bottom. Both of these two works are taken in the wild, which creates a sense of tranquility and also enables viewers to feel closer and more relatable. Boys Tethered is a triptych presented in three images. This beautiful setting is taken at a pier by the sea. On the left panel, there is a dark red boat with a boy sitting inside. Around the corner, we can see part of the pier. It looks like that the boy is about to set off his adventure. In the middle image, there are no human figures inside, but a rope on the pier, which linked with the boat, drew my attention. Following the rope, I saw another boy in the third image, rope in his hand. Sitting at the edge of the pier, he looks down at the rope on his hand. He seems thinking about something; maybe he is wondering if he should release the rope and let the boat flow away. The image somewhat gives me a painful feeling of growing-up. There is always going to be one day when a kid is old enough to leave his parent and set off his own journey. At that time, he has to face all uncertainties in the future on his own. Deciding to leave is a sign of growing up. It is both exciting and somewhat scary, both beautiful and also painful. This intimate photo just makes viewers fell so relatable: It is David Hilliard’s autobiography, but also everyone’s biography. In another photo in this collection, Rock Bottom, David Hilliard shows us the relationship between the father and son. Through the triptych, I saw a close but far, like but also unlike relationship in this father and son. The image of the father is shown in the left image, large and sharp, whereas the son is shown in the right image, smaller and far behind his father. They look similar; they both have the same tattoo on their chests. However, they are far away from each other. In between them, the middle image separates them into two parts. The whole work seems to me that while the son always tries to follow his father, he can never reach it. The other body of Work of David Hilliard, The Tale is True, again, is his autobiography. The “tale” in the title implies an old English story—The Seafarer. At the beginning of the works, Hilliard includes a poem: This tale is true, and mine. It tells How the sea took me, swept me back And forth in sorrow and fear and pain, Showed me suffering in a hundred ships, In a thousand port, and in me… The Seafarer

The poem clearly shows us what Hilliard hopes to express. Just like the seafarer, who suffers from the hardship brought by the merciless sea, David Hilliard’s life is tough as well. In an interview, Hilliard once said, “As a gay man, much of my life, especially in my early years, was spent searching for an identity that was acceptable to both society and myself.” To the seafarer, the sea and wind are torturing him, and to Hilliard, the struggle is the searching of his own identity. It is suffering, painful and hard. However, from the poem, we can also sense some optimistic feeling in the end. I feel the last three lines expresses that although life is full of hardship, the seafarer will adapt, endure and eventually accept it. That is the meaning of Seafarer, just like searching the identity is a meaning of Hilliard’s life. Just like Being Like, in The Tale is True, same father-son relationship photo appears as well. In the 4 panel photography Wiser and Despair, we see the father and the son again are shown in the separate panel, even though they are reading in the same table. In this picture, I noticed that David Hilliard’s father is sitting near the edge of the table and half of his book has already been out of the table. It seems that he acts a little bit awkward when sitting close to his son. By looking at photos David Hilliard took, I feel that there seems always an unbreakable gap between the father and son; the struggle never stops. However, the light in the room is really bright and warm. It creates a cozy and comfortable feeling, which make me believe that everything will get better. Another works I found interesting is the diptych The Tale is True. Actually, not only the poem, Hilliard’s picture also contains many details that response to the title. This picture is just a good example. In this piece, there is a huge painting ship is presented. Under the painting stood David. He didn’t look at the camera. Rather, he stood stiffly and looked somewhere we couldn’t see. It seems like he is getting lost. And the picture on the right is the hallway. With great depth of field, end of the hallway seems really far from us. Several open doors are there and at the end of the hallway, there was a chair, which is captured so sharp in this photo. The chair gives me a sense of feeling that it is out there, right in front of our eyes, but it seems also far away from us, hard to reach. Both the hallway and David Hilliard’s expression somehow shows an uncertainty to the future. But the ship on the top, sturdy and full of energy, seems will guide him through all the adversities. I really like David Hilliard’s work. Every piece in his work is beautifully composed, and the color his use is just so appealing. His usage of polyptychs in both Being Like and The Tale is True works really well in helping stories to flow naturally. And most importantly, his work, though intimate, is appealing and relatable. Through his works, we can feel him and sometimes also ourselves.

Sources: http://www.davidhilliard.com http://www.yanceyrichardson.com/exhibitions/david-hilliard2 https://www.mutualart.com/Article/David-Hilliard--Being-Like/5C101171BA207EAE

0 notes

Photo

Anita Genovese-Mahoney 8/30/17, 2D class TCNJ, Prof. Villanueva

Formal Analysis of: Littoral Drift Nearshore #463

(Polyptych, Bainbridge Island, WA 12/1/16, Five Simulated Waves)

Dynamic Cyanotype, approx 19″x 24″ each element (total 35 elements)

Artist: Meghann Riepenhoff

Description:

The first visual intake of this piece is size. It measures 8′x14′ and is comprised of 35 19″x24″ pieces within (a polyptych). Unfortunately I have not seen it in person, but I can imagine myself being overwhelmed with regard to size (in a good way)! The materials used are paper, coated with a cyanotype solution on both sides, the solution dries and is then boxed up to bring on location to be activated/developed by the UV light of the sun. The solutions can be played around and experimented with to create horizon lines for example. Objects can be placed on top of or submerged on the paper. The shapes are very organic feeling and flowing.

At times, the shapes look like a cut of some type of stone maybe marble or Lapis Lazuli. Each 19″X24″ piece is unique with different arrangements of pattern, swaths, veins, marbleizations and splashes of indigo, blue, white and even a few spots of lavender. Although each small panel is unique unto itself there is a relationship between the panels, a flowing between each panel into the other of whites, blues, lt. blues and indigo. Some of the colors playfully bounce off of each other, like the behavior of water. The colors in the entire piece are very saturated.

There are hard line marks defining the outline of the panels themselves as well as the curvy shapes at the top where they are separated by dark grey. The textures are hard and soft at the same time. There are stone like vein marks and flowing, splashing and spattering marks which are very water like. There is a sharp contrast between the “water/blues” and the flat “sky/grey” which gives the “water” more significance and also makes the colors pop out more.

Analysis:

When I first saw this piece, I immediately thought this is churning ocean waves possibly during a storm because of the grey forbidding sky. What pops outs to is the immense size of the piece and the amazing saturated blue colors. I feel enveloped in them yet and if I was to stand in front of it, I would probably feel dwarfed by the size of the piece. The piece is very well proportioned and balanced in. The two waves of either side form columns for the smaller waves in the center (top) creating a gateway. The wave on the right side curves into the right to draw your eye back into the center the same way that the wave on the left curves to the left to bring you to the center. There is movement that mimics the rhythm and movement of the ocean. This movement flows throughout each panel and into the next which establishes a unity of the entire 8′x14′ piece.

Interpretation:

I think the artist’s emphasis is to give the viewer a sense of awe of the power of nature. On one hand we have great respect (and sometimes disrespect) for nature, the element of water is a necessity, if we did not have it, all living things on the planet would die, yet water is such a powerful entity that it can kill us as we have seen recently in Houston. Nature can be terrifying at the same time as being beautiful and life giving. It is a part of us. Our bodies are made up of 72% water.

After reading several interviews with the artist: She actually came up with the idea of submerging the “coated” sheets of paper in the ocean from a mistake she had made while trying to photograph the bioluminescence of jellyfish at night. She was not able to photograph the jellyfish because she had chosen the wrong lunar cycle, but she found that the results of what ended up being photographed were visually exciting and resembled the landscape itself. She has said that the mistake she made is the recurrent theme in her work.

Her Title, “Littoral Drift” is a geologic term that means “the action of wind-driven waves moving sand and sediment along a shoreline”. Here is a quote by Meghann: “Littoral Drift evokes time and processes that are beyond our lifetime. I think it speaks to forces that are larger and more powerful. I like the play on words. Littoral sounds like literal, and these pieces are literally drifting in form as things change in them over time”.

Judgement:

Meghann Riepenhoff’s “Littoral Drift” is effective in what she tries to convey because each person will “experience” the painting rather than just view it. It becomes an experience even viewing it as a little photo on my computer. We know it is a large piece with the info provided. The blue and white colors and textures are water like. The movement and shapes are ocean like. The way each piece was placed in the composition as a whole looks like the ocean. That image will resonate in our brain as a stormy sea. What is so amazing is that those very images were actually formed by the ocean waves and exposed continually on the emulsion coated paper over time by the sun while Meghann holds the paper in the ocean. It is almost like there is a collaboration between two artists, the ocean and Meghann! The images can be ever changing depending if she wants to re-expose a particular print. An interesting idea to think about is how the prints can be ever changing as the landscape is ever changing.

This piece is high quality with high quality materials as well as high quality intellect. It has influenced me on my approach to work. The idea that a mistake can turn into a beautiful turning point in creating makes me want to create more!

1 note

·

View note