#palazzo schifanoia

Text

Francesco del Cossa, The Triumph of Minerva: March (detail of the weavers), from the Room of the Months, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara

"She’s the goddess of a thousand things…/If I’m worthy may she be a friend to my endeavours." Ovid, Fasti, Book III: March 19: The Quinquatrus

#francesco del cossa#march#fresco#room of the months#palazzo schifanoia#ferrara#weavers#ovid#fasti#minerva#mithology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choral book detail 15th century

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Could you one day maybe consider drawing Arya and Myrcela brotp? 👉🏾👈🏾🥺 I think they have huge friendship potential

Arya thought that Myrcella's stitches looked a little crooked too.

Inspired by a detail from Francesco del Cossa's Triumph of Minerva. (Fresco, late 15th century, Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara, Italy)

#asoiaf#asoiaf fanart#myrcella baratheon#myrcella lannister#arya stark#sansa stark#house lannister#house stark

461 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any art/painting recommendation which are very teen aegon coded

From top left: (descriptions are from left to right side)

Detail of frescoes in the Hall of the Months, Palazzo Schifanoia,

Portrait of Guiliano De Medici by Benozzo di Lese di Sandro Gozzoli

Carlo Crivelli catalogue raisonné, 1975 Bovero

Portrait of a Young Man Cosmè Tura (Cosimo di Domenico di Bonaventura)

Boy with Wine Glass and Flute Jacob Gerritszoon[a] Cuyp or Cuijp 1652

Rembrandt van Rijn, Man with a Hawk, 1643

A late portrait of the two sons of the 3rd Duke of Lennox, Lord John Stuart and his Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart; Anthony van Dyck.

Portrait of two brothers by Henri Gascar (1635 –1701)

26 notes

·

View notes

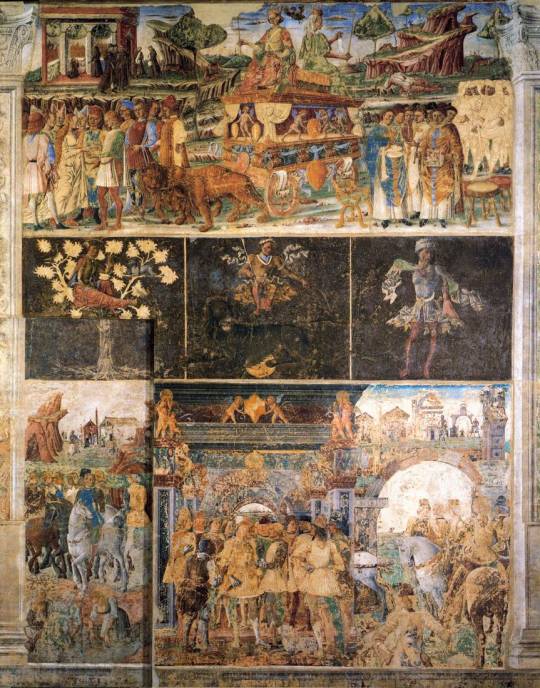

Photo

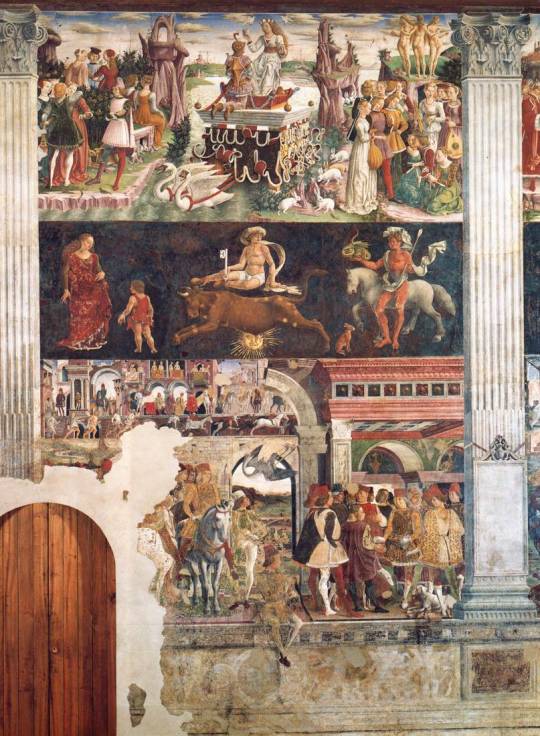

Francesco del Cossa

Allegory of April: Triumph of Venus

1476-84

Fresco, 500 x 320 cm

Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara

169 notes

·

View notes

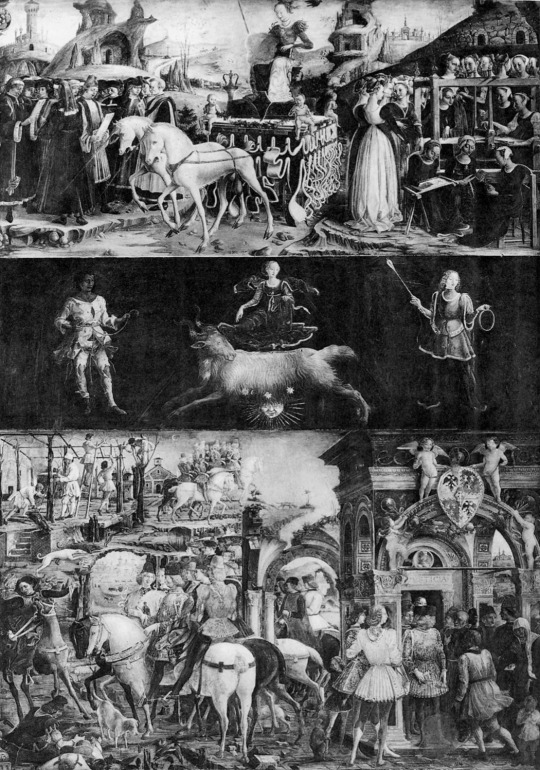

Photo

March (Aries), fresco, c. 1470. Ferrara, Palazzo Schifanoia

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

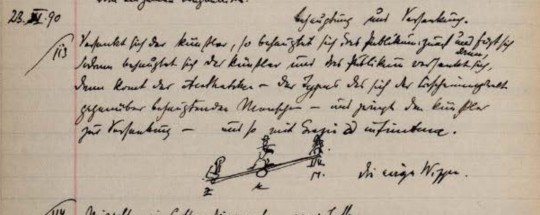

Kippen

1.

Man kann die Dinge nicht schaukeln, ohne sie zu kippen. Die grundlegenden Bruchstücke sind eventuell nicht durchgehend oder nicht anhaltend grundlegend und nicht durchgehend und nicht anhaltend Bruchstücke. Oder sie sind, wenn sie durchgehend sind, was sie sind, nicht anhaltend das, was sie sind. Oder sie sind, wenn sie anhaltend sind, was sie sind, nicht durchgehend das, was sie sind.

2.

Das Unbeständige ist dem Aby Warburg ein Elefant im Raum. Dasjenige, durch das Bewegung geht, indem es oder wenn es in und als Form(en) wahrnehmbar wird, stellt dem Warburg Fragen. Genau das macht Aby Warburg nicht nur zu einem Bild- und Rechtswissenschaftler des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. Es lässt ihn auch als jemanden erscheinen, der die bildlichen und rechtlichen Verhältnisse noch einmal anders bewertet, als es Pierre Legendre tut. Beiden werden Bilder und Rechte zum Gegenstand ihres Interesses, weil sie sich die Frage nach der Sanktionierung und Limitierung des Symbolischen, des Fiktiven, der Kunst (auch derjenigen, die man Recht nennt) stellen. Legendres Bild- und Rechtwissenschaft hat sichaus der Lektüre Lacans und aus Lacans Freudlektüre sowie aus seiner Beschäftigung mit dem römischen Recht entwickelt, er hat 'die moderne Normwissenschaft schlechthin' mit älteren Normwissenschaften assoziiert. Bei Warburg mag das ähnlich sein, übersetzbar und verwechselbar wäre ihm eventuell sogar auch was er macht, übersetzbar in das Wissen der psychoanalyse und verwechselbar mit dem Wissen der Psychoanalye. Aber im Detail entwickelt sich Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft anders, trivial zu sagen, aber nicht trivial zu verstehen.

Biographisch gibt es eine Auffälligkeit. Kaum kommt Aby Warurg aus Amerika zurück, macht er mit dem Anwalt Sally George Melchior eine Kreuzfahrt und untehält sich mit ihm über symbolische Handlungen, über die mancipation, eine actio, eine Formel, ein Protokoll, ein Zeremonie, ein Akt, der aus Akten besteht. Als er 1923 seinen Vortrag über die Reise nach Amerika gehalten hatte, den Vortrag, der heute unter dem Namen Schlangenritual kursiert, stellt ihm Fritz Saxl die Frage, wen man nach Hamburg zu einem Vortrag einladen sollte. Waburg schlägt vor, einen Germanisten und Rechtshistoriker, Conrad Borchling einzuladen und ihn über symbolische Handlungen und Symbole sprechen zu lassen. Der kommt und spricht natürlich über Stäbe (englisch: poles), das sind, wie Michael Niehaus sagt: wandernde Dinge.

Zweimal in seinem Leben reagiert Warburg also auf den Kontakt mit den Schlangen und dem Schlängeln (d.i. Kulturtechnik, die auf ein meteorologisches Problem reagiert, weil die Tänzer mit ihrem Tanz und den Schlangen den Regen beinflussen wollen) indem er danach das Gespräch mit Juristen sucht. Das kann Zufall sein, coincidence ist das bestimmt. Aber meine These ist weiter, dass Aby Warburg in dem Moment in nachdrücklichem Sinne ein Autor der Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft geworden ist, als er nicht sein Wissen über Bilder juristisch zu ergänzen sucht oder sein Wissen über das Recht mit Bildern zu ergänzen sucht. Diese beiden biographischen Fälle, von mir aus Zufälle, sind Kreuzungen, in denen Warburg nichts zu ergänzen sucht. Er will kreuzen. Der Zeitpunkt, in dem er in nachdrücklichem Sinne zum Autor einer Bild- und Rechtswissenschaft wird, das ist insofern die Zeit seines ersten Vortrages in Rom, die Zeit, in der er Zeitmessung und Schaffung von Denkräumen als dajenige begreift, was ihm Fragen stellt. Das ist die Zeit, in der er den Palazzo Schifanoia entziffert, ein Verwaltungsgebäude (kein Objekt der Verfassungen, aber eines der Verwaltungen, also auch niederer, minderer, schwacher juridischer Kulturtechniken).

In dem Moment, wo er begreift, dass nicht unbedingt Bilder oder unbedingt Rechte das Objekt seiner Wissenschaft sind, sondern dass es Objekte sind, durch die Bewegung geht, eine Bewegung, die in und als Form wahrnehmbar wird, in der Kehren, Kippen, Windungen, Wenden oder Falten vorkommen, da wird er zum Autor.

Kalender, Sternenbilder, Boronzelebern, eine Welt, die der Atlas im Rücken hat, auf der Fortuna bewegt und bewegend ist und darum immer das, was ich Polobjekte nennen, das sind die Objekte seiner Wissenschaft. Das müssen keine Bilder sein, Tabellen, Diplomaten und diplomatische Schreiben tun es auch. Das müssen kein Gesetz, kein Vertrag und kein Vertragen sein, Schlangen tun es auch, Schlingen tut es auch.

Durch sie, seine Objekte, geht Bewegung. Durch Kalender und Sternenbilder wird der Bewegung Wort und Bild gegeben, wird sie orientiert und zu Aktion. Durch Kalender und Sternenbilder geht Bewegung, sie machen Bewegung möglich, auch dann wenn alles weitere unsicher bleibt. Durch Staatstafeln kann man die Lateranverträge in einem Sinne kreditieren: man kann sie von allen Seiten ansehen und ihre Polarisierung wahrnehmen. Warburg stellt das der Übersetzung zur Verfügung. Will ich opfern, kann ich opfern. will ich nicht, kann ich es nicht wollen. Will ich mich mit Mördern einlassen, kann ich es. Will ich es nicht, kann ich es nicht. Warburg macht abschätzbar, diese Kreditierung schätz die Laternverträge, nur eben auch so, wie man Risiken und Gefahren schätzt. Das ist praktische Beratung am Recht, so was muss Rechtswissenschaft auch lehren, nicht nur was gilt und was gelten soll, nicht nur was gut und was böse ist, nicht nur was erlöst und was verdammt, nicht nur, was angeblich Apokalypse aufhält oder Apokalypse bringt, nicht nur, was den Reichtum angeblich sichert und was ihn angeblich zerstört. Man braucht vague Assoziationen, wenn man nicht gleich an nichts glauben will. Das ist Ungewissheit als Chance aber auch als changierendes Riskieren und Gefährden, sogar auch als Gefährung und Riskierung des Changierenden. Das ist Unbeständigkeit als dasjeinge, was nicht nur Laster sondern eventuell auch ein Bus ist, also Transporter für Menschliches und Umenschliches, und was metaphorisch, aber nicht nur metaphorisch ist.

Warburg wird in dem Moment zum Autor einer Bild- und rechtswissenschaft, als er Polarforscher wird. Der Vortrag von 1912 markiert diesen Zeitpunkt. Von da an macht seine Bildwissenschaft Unterschiede, die einen Unterschied machen, die ihn also von anderen und von solchen Bildwissenschaftlern untescheiden, deren Objekt nicht unbedingt ein Polobjekt, aber unbedingt ein Bild sein soll. Von da an macht Warburgs rechtswissenschaft Unterschiede, die einen Unterschied machen, die ihn von anderen Rechtswissenschaftlern unterscheiden weil das Objekt seiner Rechtswissenschaft nicht unbedingt Recht, gesetzlich, legal, gerecht sein soll, es soll unbedingt ein Polobjekt sein. Zugespitzt ausgedrückt: Dieses Objekt wird nicht unbedingt gebraucht, um die Welt recht und gerecht zu machen, nicht unbedingt gebraucht, um sie gut und edel zu machen, um sie gut und edel zu erhalten oder um etwas in ihr zu billigen, es wird nicht unbedingt gebraucht, um etwas zu rechtfertigen. Es wird unbedingt gebraucht, um zu polarisieren, aber das heißt auch: um Polarisierung wahrnehmen und oder ausüben zu können. Die Polarisierung versucht Warburg durchaus als etwas zu denken, das man anfangen und mit dem man anfangen könnte, aber das ist der Punkt, an dem man Warburg vorhält, sein Rezeption der Wissenschaft entweder metaphorisch oder instrumentell zu betreiben, in Wirklichkeit aber nicht zu verstehen, was Polarität sei.

Diese Kröte müssen Juristen und Bildwissenschaftler schlucken, nämlich die, dass Warburg nicht nach dem Modell eines interdisziplinären Versprechens arbeitet, in dem das Wissen um Bilder das Wissen um Rechte ergänzt oder das Wissen um Rechte das Wissen um Bilder ergänzt.

Warburg will mit Polarität, mit Meteorologie, mit Unbeständigkeit umgehen können. Der will, so denke ich, das alles auch umgehen können. Aber die Kreuzungen stellt ihm Fragen, auch dann noch, wenn das Anhaltende nicht durchgeht und das Durchgehende nicht anhält. Und das lässt ihn nur kreuzen, nichts ergänzen. Man kann die Dinge nicht schaukeln, ohne sie zu kippen. Warburg, und das unterscheidet ihn von Legendre, bleibt Wechsler und Verwechsler, der bleibt das, was man in Star Wars einen Changeling nennt. Für Legendre ist das Bild ein Objekt, das die Abwesenheit meistern und den Abgrund überbrücken soll. Für Warburg ist das Bild ein Objekt, durch das Bewegung gehen soll. Und darum unterscheidet sich Warburg, jetzt vermute ich auf eine Weise, von der ich nicht weiß, wie mutig sie ist, zwar von Legendre, aber nicht unbedingt groß. Ich glaube, dass Warburg einer der Typen ist, die Eduardo Viveiros de Castro erforscht hat, dessen Unbeständigkeit also diejenige einer wilden Seele ist.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

TÍTULO: Virgen entronizada con el Niño, los santos Ana, Isabel, Agostino y el beato Pietro degli Onesti

AUTOR: Ercole de Roberti

FECHA: 1479 - 1481

MATERIAL Y TÉCNICA: Pintura al óleo sobre lienzo

DIMENSIONES: 323x240 cm

INVENTARIO: 203

El cuadro, también llamado Pala Portuense, fue pintado entre 1479 y 1481 para la iglesia de Santa María en Porto Fuori de Rávena, gobernada por los Cánones de Letrán; fue trasladado, durante el siglo XVI, a San Francisco, en la misma ciudad, desde donde llegó a la Pinacoteca tras las supresiones napoleónicas. Bajo una majestuosa arquitectura se encuentra el podio octogonal sobre el que descansa el trono de la Virgen; la base está decorada con paneles que simulan antiguos relieves de bronce, siguiendo el ejemplo de lo que Donatello creó para el altar del Santo en Padua. Narra La Matanza de los Inocentes, La Adoración de los Reyes Magos y La Presentación de Jesús en el Templo.

A los lados del trono aparecen San Agustín, a la izquierda, protector de la orden de Letrán, y Pietro degli Onesti, su fundador; la base del trono está sostenida por columnas a través de las cuales se puede ver un extraordinario paisaje marino tormentoso, probablemente en alusión a la fundación de Santa María del Porto: habiendo llegado a Rávena a su regreso de Tierra Santa, de hecho, Pietro degli Onesti había escapado. del naufragio y había prometido a la Virgen la construcción de una gran iglesia como exvoto por el milagro recibido.

El retablo constituye uno de los resultados más cercanos a la monumentalidad compuesta y clásica lograda por de' Roberti, quien aquí calma el agitado dinamismo de los frescos del Palazzo Schifanoia en Ferrara y llega a formas sólidas y medidas, donde las figuras son tratadas con una robusta El modelado plástico y las inquietudes expresivas del artista quedan confinadas a las partituras decorativas.

Información e imagen de la Pinacoteca de Brera.

0 notes

Text

Weekend Epifania a Ferrara tra mostre, mercatini e la Befana

Ci sono anche le aperture serali

della mostra di Achille Funi al Palazzo dei Diamanti, il 5 e 6

gennaio, tra le iniziative in programma per il weekend

dell’Epifania a Ferrara. E tutti i musei civici della città

(Museo Schifanoia e Civico Lapidario, Casa di Ludovico Ariosto)

e il Museo della Cattedrale, insieme al Castello, rimarranno

aperti senza giorno di chiusura fino a domenica 7 gennaio, con…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Re-enchanting the World - Malgorzata Mirga-Tas

Pavillon Pologne

Reprend la structure en trois bandes superposées des fresques du Palazzo Schifanoia de Ferrare.

En haut, l’artiste raconte l’épopée mythique des Roms vers l’Europe. Au centre, on retrouve les signes du zodiaque mais réactualisés. En bas, les allégories de la Renaissance ont été ici remplacées par des scènes de la vie quotidienne des Roms (nettoyage d’un poulet, partie de cartes, enterrement…)

0 notes

Photo

MAŁGORZATA MIRGA TAS Da Schifanoia: re-incantare il mondo

Dopo essere stata esposta alla 59^ Biennale d’arte di Venezia del 2022, la mostra ispirata agli affreschi dei mesi del ferrarese Palazzo Schifanoia, arriva a Ferrara.

0 notes

Text

Francesco del Cossa, April. Fresco in Palazzo Schifanoia (detail), Triumph of Venus

"They say Spring was named from the open (apertum) season, /Because Spring opens (aperit) everything and the sharp/ Frost-bound cold vanishes, and fertile soil’s revealed,/ Though kind Venus sets her hand there and claims it." Ovid, Fasti, Book IV

0 notes

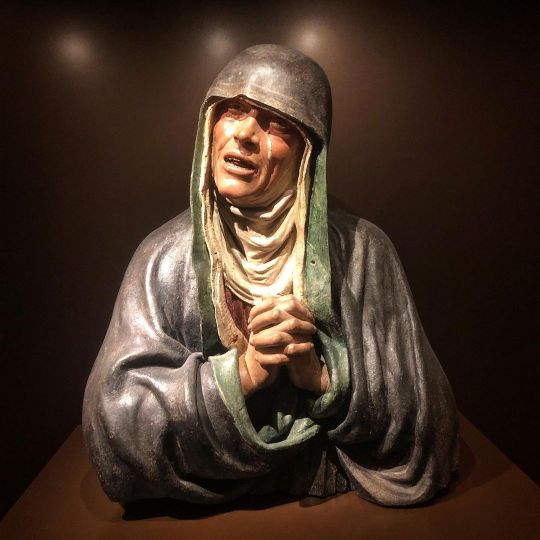

Photo

#guidomazzoni #palazzoschifanoia (presso Palazzo Schifanoia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CmpCvZKrMk9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

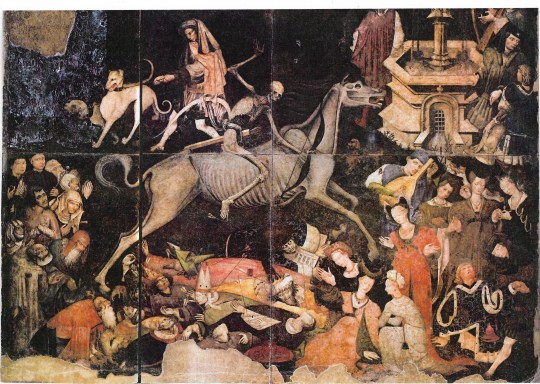

Sicily's Triumph of Death

Triumph of Death – Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo

Palazzo Sclafani, Palermo

The Triumph of Death – il Trionfo della Morte – is a huge fresco filling most of the end wall of a large and lofty hall in Palazzo Abbatellis, the National Gallery of Sicily in Palermo. It was not painted for that room, but for a wall of the courtyard of another palazzo in the city, Palazzo Sclafani, still standing and still to be seen, though not visited, close to a public garden east of the Cathedral. That palazzo was built in 1330, originally for a Count, Matteo Sclafani, but exactly a hundred years later, in 1440, the City Administration (the Senate), wishing to rationalise its hospital provision and have one big hospital rather than seven small ones, requisitioned the palazzo, by then in a poor state, and set about converting it into the main hospital for the city. This development evidently included commissions for artists, and one of those was given to the painter of the Triumph. It is unfortunate that the commission document has never been found, but we can be thankful that aerial bombardment of Palazzo Sclafani in 1943 did not destroy, only damaged, the fresco, which was soon after removed, restored and displayed where it now is.

Details from Triumph of Death (clockwise from top): Death rides of a skeletal horse; The Fountain of Life; Death’s Victims; Lute Player

The painter’s choice of subject was a natural one for the courtyard of a hospital in those days. Sclafani’s palazzo dated from the time of the Black Death, but in Sicily, as in mainland Italy and the rest of Europe, Death in the form of plague had galloped back into people’s lives unpredictably and most often fatally ever since. Skeletal Death rides his skeletal horse full tilt across the fresco; his victims lie in a heap at the bottom of the picture. There is, however, Life, a Fountain of Life, beside which a harpist plays his silent music. Elegant ladies converse with animated gestures of shared alarm; there are men to the left, young and old, but, one observes, no children. Above the men a menacing wolfhound and another dog strain at the leash. Death, in short, threatens Life, for the mitred as for the unmitred, but Life is there. Memento Mori, you who enter this place and may not leave it alive; but remember, too, that you have lived, and life, with all its music and conversation, will continue after you.

Such is the general message. I have chosen this work as the focus of my latest Studies in Connoisseurship partly because we are living through a global pandemic. The hospitals of Palermo, as of many other cities in Italy and beyond, have once more been filled with very ill people dying, or threatened with dying, as life outside them struggles to continue.

As a connoisseur my motive is different. The fresco, unsurprisingly, has captivated many visitors and inspired some writers, but the fact that without a surviving contract or other document from the early 1440s we still do not know who painted this work surely plays its part in our fascination: we see it as a unique phenomenon, sui generis. This of course is unreal: someone painted it. Sicilians wonder if he was Sicilian. The last owner of Palazzo Sclafani lived in Spain; could he have proposed a Spanish artist? Some, bizarrely, have suggested that the painter may have come from the Netherlands. If he was Sicilian, did he afterwards leave the island to seek his fortune, like Antonello da Messina, on the mainland? Or did he come from the mainland, invited by the hospital’s rector, Pietro Speciale, or someone else who was commissioning works of art for it? A work like the Triumph of Death does not appear from nowhere; what other works by its creator preceded it?

I cannot answer these questions, but privately I have shared the quest for answers over many years, and I think I can at least contribute to our understanding of this anonymous artist by adding other works that may reasonably be attributed to him. As with all exercises in connoisseurship, what is ‘reasonable’ is what can be argued visually through juxtaposition of images.

First, a general observation should be made about the work from an aesthetic point of view. Iconographically, the Triumph of Death is well known and quite a lot has been written about antecedent examples of the theme, at the Campo Santo at Pisa, in the work of Orcagna, and elsewhere. In this case, however, the horse and the rider are not enough to pull the composition together, because all around them are disparate groups of figures and animals and objects that relate awkwardly to each other and fail to bond into a coherent whole. Whatever else he was, this artist cannot be said to be a great composer. Seen from a distance – as the fresco can be – it reminds one of some large and similarly incoherent tapestries. This is a serious defect which no doubt excludes it, as a whole, from the very highest rank of artistic achievement.

Details from Triumph of Death (clockwise from top left) – Death’s Horse; The King; a Survivor of Death; Death’s Victims

The words ‘as a whole’ are to be emphasised, though, because as soon as we draw close and our eyes take in the details (as would those of anyone standing or walking under the arcade of that hospital courtyard in 1442), they are everywhere amazed by what they discover in the sphere of draughtsmanship. There the artist excels, both in ‘disegno’, his brilliant invention of representational forms, and in the extraordinary refinement and elegance of his line, whether in the tail of the hound, the head of the horse (like something out of Guernica), in the aristocratic ladies or, most originally of all, in the heads of the dead tumbled together at the bottom. It is the quality of this artist’s drawing, rather than his colour or composition, that makes it less important that all the colour reproductions offered here are of questionable fidelity.

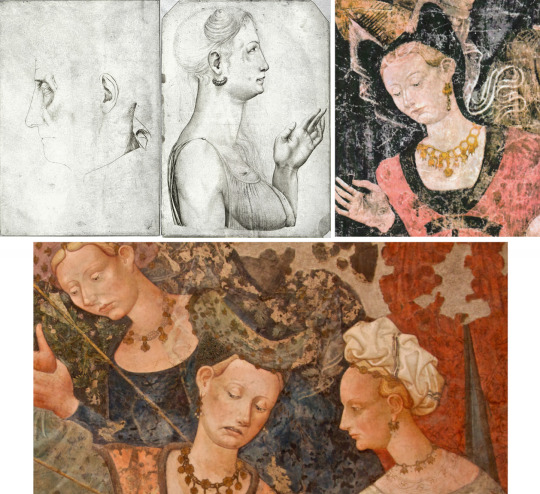

Comparing drawings at the Louvre (top left and top centre) with details of the noble women from Triumph of Death

Comparing the similar hand gesture of the drawing of a Lady (left) and a Survivor of Death (right)

To pick out the draughtsmanship is, I believe, to pick up the key that can unlock the mystery of what else this artist did. Over many years of intermittent study I have kept a look-out for any drawings that might be associated with him by virtue of their extreme linear elegance combined with a certain oddity. Among the drawings in the Vallardi Album at the Louvre are a few that are not by Pisanello, and among these is a pair of profiles, one of a mature Lady, the other of an older Man. The one of the Lady is the more developed and the more remarkable, for the fine lines of the hair and the purity of contour in her profile. Compare this drawing with the depiction of the aristocratic ladies in the Trionfo, especially the one seen in profile who likewise wears an eardrop, and I think a definite similarity is observable. It is confirmed when we turn to the raised left hand of the Lady in the drawing. Artists describe hands and their gestures in such interestingly different ways: this one favours two fingers (first and second) straight, two fingers (third and fourth) bent. Anyone who tries to put their own fingers into the same position will soon realise that it is not natural and not sustainable; but there it is, not only in the drawing but in the Trionfo, exactly in one instance, and to varying degrees of bentness in many more. To anyone acquainted with the history of connoisseurship this could be a textbook illustration of Giovanni Morelli’s ‘method’.

Drawing of a Man with a Fur Collar (Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München)

Comparing the Louvre Drawing (left) and Munich drawing (right) with faces from Triumph

At the Print Room at Munich (Staatliche Graphische Sammlung) there is another drawing, this time of a Man with a Fur Collar seen close-up, his head turned to our left, his neck emerging from a fur collar encircling it. this is not finished, but those fine lines drawn in long parallel strokes that distinguished the tresses of the Lady in the Vallardi Album are also here, along with a very particular shape given to the eye (upper lid and corner nearest to the nose) and to the ear, philtrum> and lips. These features are most clearly matched in the face of the young man on the extreme left of the Trionfo, and that of his companion.

Portrait of a Lady – Johnson Collection, Philadelphia

Comparing the Drawings from the Louvre (Top Left and Bottom Right) and Munich (Bottom Left) with the Painting of the Lady at Washington

At this point in my quest for drawings by the Trionfo Master the trail goes cold. There is, however, a painting in the Johnson Collection at Philadelphia, attributed, unconvincingly in my view, to Ercole de Roberti, which exhibits exactly the eye-shape, ear-shape, lips and philtrum of the Munich drawing, as well as the sharp, rounded eyebrows of the Vallardi Lady and the ear of the Vallardi Man.The Johnson painting has morphological similarities with the Trionfo, but it seems to belong to a later period, and there is reason for thinking that it does. It may indeed be the link between the Trionfo and a whole body of much later work by this artist, not in Sicily but in Ferrara.

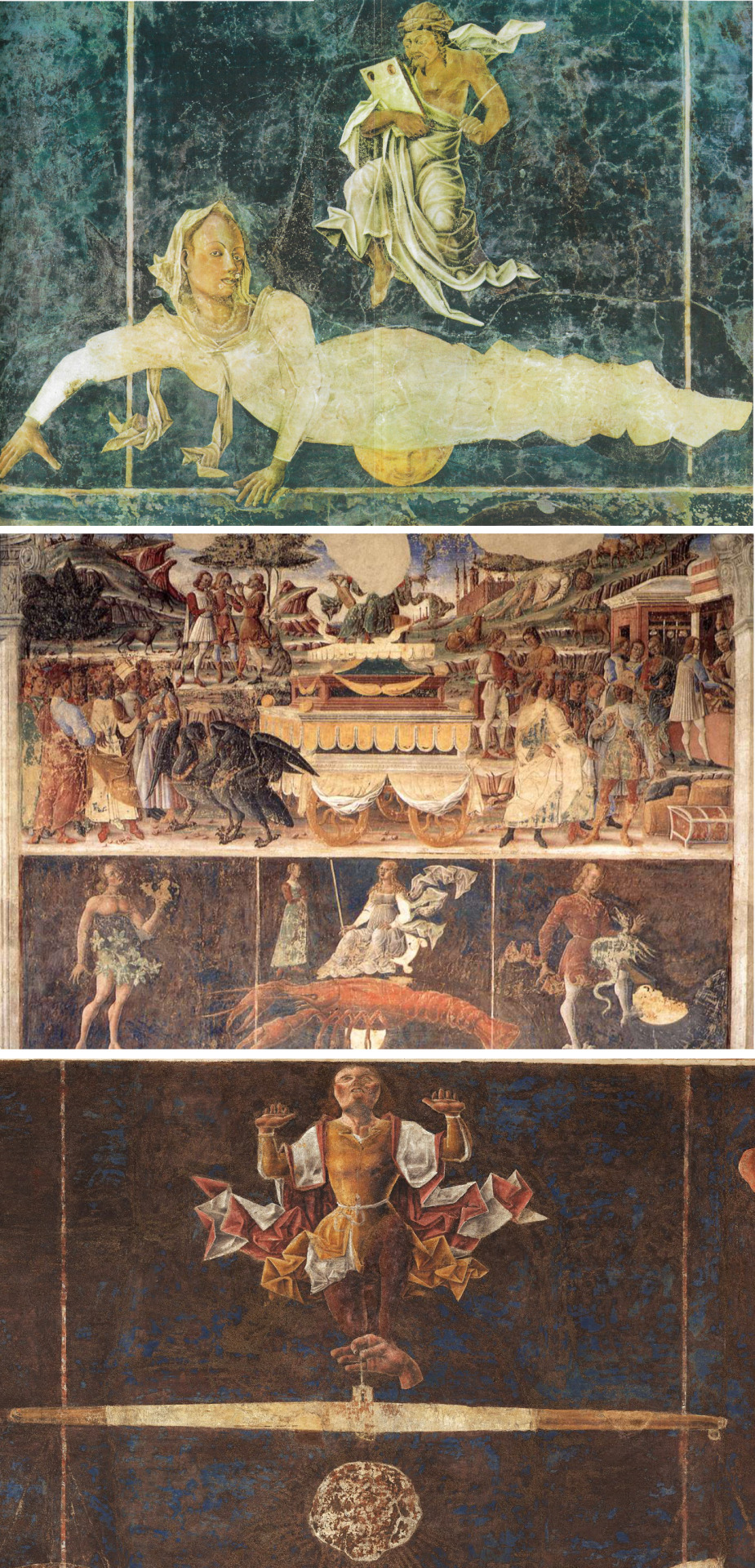

Comparing faces with fresco in Palazzo di Schifanoia of Virgo recumbant with her Decani (bottom panels)

In the Salone dei Mesi of the Palazzo di Schifanoia in Ferrara it is possible to distinguish fairly clearly the work of Francesco del Cossa, but there is another artist, credited with many of the Months whose identity has always puzzled art historians. He has been called the ‘Maestro di Ercole’ or the ‘Maestro degli Occhi Spalancati’, but these names have not led to much development of an oeuvre for an artist of such weird imagination and invention, a man capable, as Cossa was not, of creating extraordinary images like the figure of Virgo, for August, the giant lobster, for June, or the sign of Libra, for September.

Scenes from the Fresco at Palazzo Schifanoia: Virgo in the Allegory of August (top); The Lobster from the Allegory of June (centre); Libra from the Allegory of September (bottom)

From Palazzo Sclafani to Palazzo Schifanoia is not only a leap of geography; there must also be a gap of many years, perhaps a quarter of a century. It is frustrating and unsatisfactory that there is, as yet, so little to fill that gap. I do believe, nevertheless, that Palermo and Ferrara are connected in the career of this painter. The argument depends as always on a juxtaposition such as this one: the Munich drawing, the Johnson portrait, the heads of Virgo.

Detail of Virgo (top left) to compare with the Lady in Philadelphia (top centre) and the Man in Munich (top right), and comparisons of the horse from Triumph of Death (bottom left) and horses from the Allegory of March (bottom right)

From August we can move to other Months in the astrological zodiac, and discover that the eccentricity manifest at Palermo has not deserted this artist, but it has changed. In the many years that have elapsed he has developed, for example, a bizarre way of representing drapery – like sharply creased paper folded one way and then another – and rocks – like laminated tombstones. Despite the lapse of years there is a horse’s head whose structure can still remind us of the one at Palermo.

The Allegory of August, Triumph of Ceres and representation of Virgo – Palazzo Schifanoia

The Allegory of September (top) and detail of Mars in bed with a Nymph (bottom) – Palazzo Schifanoia

There is also a change of theme. The work at Palermo is dominated, very obviously, by Death, his work at Ferrara quite largely by Sex, especially so in August. The bare-breasted figure of Ceres brandishes the reaped corn and then, recumbent, sprawls luxuriously across three divisions while looking out seductively at the spectator. In September Mars is in bed with a nymph, Ylia, and the figure of Libra is set between two figures of a physique reminiscent of male ballet dancers, their calves developed like athletes on Greek pots. Sex, yes, but also, to complete the trinity, War. There is now a definite martial streak to the artist’s imagination, no doubt fuelled by the idea of ‘triumph’ and expressed in images of Mars, Vulcan’s Forge, armour.

Detail of Vulcan’s Forge from The Allegory of September

His contributions to the Triumph scenes are at least as ill-composed as the Triumph at Palermo, but under them, in the Months, he wisely sets his figures and creatures against plain dark backdrops. We remember them all the better for their standing out pale, even white, against the deep blues and browns. At Palermo this had only begun to happen in the upper left quadrant and behind the horse.

Clearly I and others must look diligently for other works by this artist that will allow us to see how he developed between the two periods of activity and what he was doing before the first one. The drawings that I have proposed as his must belong to the earlier, Palermitan phase of his career, but how did he draw in later years? His name is more likely to be discovered by historians and archivists. I would like him to be a Sicilian – the island has too few major artists besides Antonello da Messina – but I must declare a doubt that he was. We need the evidence in any case to tell us whether he was brought to Palermo from the mainland or was native to the island at the time of the Sclafani commission. Without the facts we are left in ignorance. If the thesis presented here, of a connection between Palermo and Ferrara, should find acceptance, I hope that it will have armed us with a little more understanding of his character as an artist. He has an abundance of character. As painter, as draughtsman, as inventor of images, he appears to be one of the great eccentrics of European art, and one that can speak to us, of life and death and love, in another dark time.

#triumph of death#sicily#italian art#palazzo schifanoia#palazzo sclafani#palermo#studies in connoisseurship#connoisseurship#art history#art secrets

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Francesco del Cossa, The triumph of Venus, detail, Palazzo Schifanoia, circa 1470

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TURA, Cosmè

Allegory of July: Triumph of Jupiter

1476-84

Fresco, 500 x 320 cm

Palazzo Schifanoia, Ferrara

81 notes

·

View notes