#paleoecologist

Text

“It was an assumption—almost an article of faith—amongst many biogeographers, ecologists, and paleoecologists that the great regional rainforests were, at Western contact, the product of natural climatic, biogeographic, and ecological processes,” wrote paleoecologist Chris Hunt, now based at Liverpool John Moores University, and his colleague, Cambridge University archaeologist Ryan Rabett, in a 2014 paper. “It was widely thought that peoples living in the rainforest caused little change to vegetation.”

New research is challenging this long-held assumption. Recent paleoecological studies by Hunt and other colleagues show evidence of “disturbance” in the vegetation around Pa Lungan and other Kelabit villages, indicating that humans have shaped and altered these jungles not just for generations—but for millennia. Borneo’s inhabitants from a much more distant past likely burned the forests and cleared lands to cultivate edible plants. They created a complex system in which farming and foraging were intertwined with spiritual beliefs and land use in ways that scientists are just beginning to understand.

Samantha Jones, lead author on this investigation and researcher at the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, has studied ancient pollen cores in the Kelabit Highlands as part of the Cultured Rainforest Project. This is a U.K.-based team of anthropologists, archaeologists, and paleoecologists that is examining the long-term and present-day interactions between people and rainforests. The project has led to continuing research that is forming a new scientific narrative of the Borneo highlands.

People were most likely manipulating plants from as early as 50,000 years ago in the lowlands, Jones says. That’s around the time humans likely first arrived. Scholars had long classified these early inhabitants as foragers—but then came the studies at Niah Cave. There, in a series of limestone caverns near the coast, scientists found paleoecological evidence that early humans got right to work burning the forest, managing vegetation, and eating a complex diet based on hunting, foraging, fishing, and processing plants from the jungle. This late Pleistocene diet spanned everything from large mammals to small mollusks, to a wide array of tuberous taros and yams. By 10,000 years ago, the folks in the lowlands were growing sago and manipulating other vegetation such as wild rice, Hunt says. The lines between foraging and farming undoubtedly blurred. The Niah Cave folks were growing and picking, hunting and gathering, fishing and gardening across the entire landscape.

[...]

“The Cultured Rainforest project has shown how profoundly entangled the lives of humans and other species in the rainforest are,” says University of London anthropologist Monica Janowski, a member of the project team who has spent decades studying highland Borneo cultures. “This entanglement has developed over centuries and millennia and succeeds in maintaining a relatively balanced relationship between species.” Borneo’s jungle is, in fact, anything but untouched: What we see is a result of both human hands and natural forces, working in tandem. The Kelabit are a little bit farmer and a little bit forager with no clear line between, Janowski says. This dualistic approach to land use may reveal a deeper human nature. “Scratch any modern human and you will find, under the surface, a forager,” she says. “We have powerful foraging instincts. We also have powerful instincts to manage plants and animals. Both of these instincts have been with us for millennia.”

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why you should become a Paleoecologist, like Me!

Get to think about whole ecosystems, not just individual organisms

Look at the Big Picture and connecting it to Today!

No day on the job is the same!

There's so few of us there's not much competition!

Why you should NOT become a Paleoecologist, like Me!

too many variables, and most are lost to time

different fields of paleontology (bird, mammal, insect, flowering plant, non-flowering plant, etc.) have different standards, good luck figuring that out

Daily existential crises over the nature of time, space, matter, and energy

There's so few of us because we're all collectively going insane

Join Paleoecology Today! You'll lose your remaining sanity, but the moral high ground will always be yours!

249 notes

·

View notes

Text

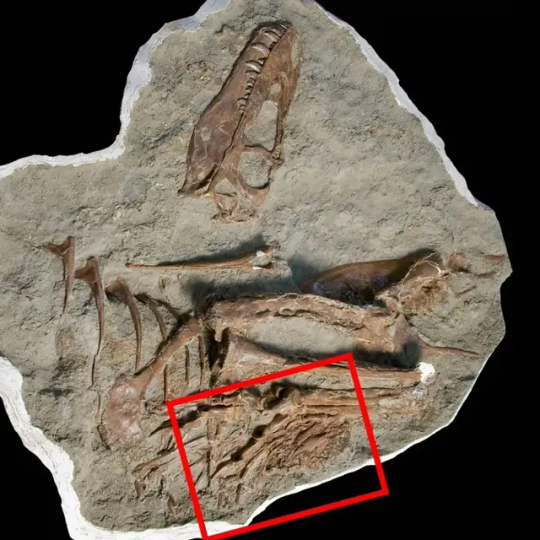

First tyrannosaur fossil discovered with its last meal perfectly preserved in its stomach

Researchers have found a tyrannosaur’s last meal perfectly preserved inside its stomach cavity.

What was on the menu 75 million years ago? The hind legs of two baby dinosaurs, according to new research on the fossil published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

Dinosaur guts and hard evidence of their diets are rarely preserved in the fossil record, and it is the first time the stomach contents of a tyrannosaur have been uncovered.

The revelation makes this discovery particularly exciting, said co-lead author Darla Zelenitsky, a paleontologist and associate professor at the University of Calgary in Alberta.

“Tyrannosaurs are these large predatory species that roamed Alberta, and North America, during the late Cretaceous. These were the iconic apex or top predators that we’ve all seen in movies, books and museums. They walked on two legs (and) had very short arms,” Zelenitsky said.

“It was a cousin of T. rex, which came later in time, 68 to 66 million years ago. T. rex is the biggest of the tyrannosaurs, Gorgosaurus was a little bit smaller, maybe full grown would have been 9, 10 meters (33 feet).”

The tyrannosaur in question, a young Gorgosaurus libratus, would have weighed about 772 pounds (350 kilograms) — less than a horse — and reached 13 feet (4 meters) in length at the time of death.

The creature was between the ages of 5 and 7 and appeared to be picky in what it consumed, Zelenitsky said.

“Its last and second-to-last meal were these little birdlike dinosaurs, Citipes, and the tyrannosaur actually only ate the hind limbs of each of these prey items. There’s really no other skeletal remains of these predators within the stomach cavity. It’s just the hind legs.

“It must have killed … both of these Citipes at different times and then ripped off the hind legs and ate those and left the rest of the carcasses,” she added. “Obviously this teenager had an appetite for drumsticks.”

The two baby dinosaurs both belonged to the species called Citipes elegans and would have been younger than 1 year old when the tyrannosaur hunted them down, the researchers determined.

The almost complete skeleton was found in Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park in 2009.

That the tyrannosaur’s stomach contents were preserved wasn’t immediately obvious, but staff at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alberta, noticed small protruding bones when preparing the fossil in the lab and removed a rock within its rib cage to take a closer look.

“Lo and behold, the complete hind legs of two baby dinosaurs, both under a year old, were present in its stomach,” said co-lead author François Therrien, the museum’s curator of dinosaur paleoecology, in a statement.

The paleontologists were able to determine the ages of both the predator and its prey by analyzing thin slices sampled from the fossilized bones.

“There’s growth marks like the rings of a tree. And we can essentially tell how old a dinosaur is from looking at those, the structure of the bone,” Zelenitsky said.

Changing appetites of top predators

The fossil is the first hard evidence of a long-suspected dietary pattern among large predatory dinosaurs, said paleoecologist Kat Schroeder, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University’s department of Earth and planetary science, who wasn’t involved in the research.

The teen tyrannosaur didn’t eat what its parents did. Paleontologists believe its diet would have changed over its life span.

“Large, robust tyrannosaurs like T. rex have bite forces strong enough to hit bone when eating, and so we know they bit into megaherbivores like Triceratops,” Schroeder said via email. “Juvenile tyrannosaurs can’t bite as deep, and therefore don’t leave such feeding traces.”

She said that scientists have previously hypothesized that young tyrannosaurs had different diets from fully developed adults, but the fossil find marks the first time researchers have direct evidence.

“Combined with the relative rarity of juvenile tyrannosaur skeletons, this fossil is very significant,” Schroeder added. “Teeth can only tell us so much about the diet of extinct animals, so finding stomach contents is like picking up the proverbial ‘smoking gun.’”

The contents of the tyrannosaur’s stomach cavity revealed that at this stage in life, juveniles were hunting swift, small prey. It was likely because the predator’s body wasn’t yet well-suited for bigger prey, Zelenitsky said.

“It’s well known that tyrannosaurs changed a lot during growth, from slender forms to these robust, bone-crushing dinosaurs, and we know that this change was related to feeding behavior.”

When the dinosaur died, its mass was only 10% of that of an adult Gorgosaurus, she said.

How juvenile tyrannosaurs filled a niche

The voracious appetite of teenage tyrannosaurs and other carnivores has been thought to explain a puzzling feature of dinosaur diversity.

There are relatively few small and midsize dinosaurs in the fossil record, particularly in the Mid- to Late Cretaceous Period — something paleontologists have determined is due to the hunting activities of young tyrannosaurs.

“In Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park, where this specimen is from, we have a very well sampled formation. And so we have a pretty good idea of the ecosystem there. Over 50 species of dinosaurs,” Zelenitsky said.

“We are missing mid-sized … predators from that ecosystem. So yeah, there’s been the hypothesis that, the juvenile tyrannosaurs filled that niche.”

By Katie Hunt.

#First tyrannosaur fossil discovered with its last meal perfectly preserved in its stomach#tyrannosaur#Gorgosaurus libratus#Citipes#Citipes elegans#dinosaurs#paleontologist#Alberta’s Dinosaur Provincial Park#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi welcome. you can call me finch

🌾 they/them / 30s / chinese / marxist / prairie boy in toronto (tragic)

I don't talk shop much but I am a tattooer by trade, fascinated by all kinds of representations of nature. I think evolutionary biology is the most interesting thing in the world and maybe in another life I am a paleoecologist but here I am drawing birds on people. it's a living

if you got here via fandom stuff sorry but I do not sideblog so you will get that mixed in with the other junk.

🌱 frequently tagged stuff:

art + textiles

scenes (place-based vibes)

reading notes

my art

my dog

photolog

babylon 5 / narn bin

all purpose star trek

disco elysium

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to a Live Science report, a new study has suggested that the pollen once thought to have belonged to flowers deposited by Neanderthals in Iraqi Kurdistan's Shanidar Cave was actually left there by insects. Paleoecologist Chris Hunt of Liverpool John Moores University said that previous interpretations that the pollen came from flowers that were collected by Neanderthals to be buried with a deceased member of their community was more likely deposited by bees. Hunt explains that the bees might have burrowed into the dirt on the cave floor, leaving pollen they had collected there as they dug in.

Since the 1950s and 1960s when the caves of Shanidar were first excavated, the flowers have been thought to be evidence of Neanderthals engaging in deliberate burial rituals.

Hunt believes that while the pollen may not have been part of a burial ritual, that does not negate the possibility that the Neanderthals living in the area engaged in this type of symbolic behavior.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The heating across the world’s oceans is literally off the charts. Last week, a buoy in Florida’s Manatee Bay recorded a water temperature of 101 degrees Fahrenheit. And since March, global average sea surface temperatures have kept smashing record highs.

You can see the global average for 2023 represented as the solid black line in the chart below. (The other squiggles are previous years.)

Meanwhile, temperatures in the North Atlantic have been climbing higher and higher above the highs in previous years. Last week, that ocean notched its highest temperature since records began in the early 1980s.

Scarier still, the North Atlantic doesn’t typically see its highest annual temperature until early September, so it’s likely to keep breaking records in the coming weeks. (In the chart below, the North Atlantic’s record-setting temperatures are the solid black line.)

What we’ve been seeing this summer is the product of the natural variability inherent in Earth’s climate combined with humanity’s rapid warming of the planet. El Niño, the band of warm water in the Pacific, has also formed and strengthened, raising global temperatures. When variability meets a long-term trend of rising temperatures, “the warms just get warmer,” says Michael Jacox, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “And when things would have been sort of extreme already, they're that much higher.”

Media attention has focused on corals—in Florida’s hot-tubbish waters and elsewhere—and rightfully so. When stressed by high temperatures, they bleach, releasing the symbiotic algae that harvest energy for them. “Of course there's a lot of concern around coral reef systems because of their biodiversity and their economic importance,” says Peter Roopnarine, a paleoecologist and the curator of invertebrate zoology and geology at the California Academy of Sciences. “But this is really affecting everything, in every aspect of the ocean and ocean life, and it goes well beyond the corals.”

Consider the plankton—literally “wandering” from the Greek. This galaxy of organisms makes up the base of the oceanic food web. Phytoplankton are microscopic floating plants that feed on sunlight. These are in turn eaten by animals called zooplankton, including small crustaceans and fish larvae. Zooplankton are consumed by larger critters, like adult fish. “Phytoplankton will drive zooplankton, which will drive fish and will feed other things,” says Francisco Chavez, a biological oceanographer and senior scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. “The whole ecosystem has to be impacted in some form or another under warmer sea surface temperatures.”

Warmer temperatures will themselves stress out any number of the species in the planktonic community. Like corals do in reef ecosystems, the organisms of the open ocean have certain tolerances for heat. “A big part of the problem is we don't know the optimal temperature ranges for probably 99 percent of the organisms out there,” Roopnarine says. “We know they have them, but it's a very difficult thing to measure.”

The sea has absorbed around 90 percent of the excess heat humanity has pumped into the atmosphere—and it shows. By 2014, half of the world’s ocean surface was logging temperatures once considered extreme, which rose to 57 percent by 2019. In other words, extreme heat has become the new normal.

“Twenty years ago, we were talking about how 2050 would be when we could really point to dramatic things beginning to happen, and we would be in trouble by 2080, 2100,” says Roopnarine. “Literally—I would say every year for the past 15 years—things are happening that tell us our models have been a bit too slow. The speed at which this has been happening, I think, is quite surprising.”

Heat on its own isn’t the only concern. When oceans warm, a few things happen physically and chemically to the surface waters that these organisms call home. The warmer seawater gets, the less oxygen it can hold. As the planet rapidly warms, scientists have found that ocean oxygen levels have been steadily dropping, in some cases precipitously: The loss is up to 40 percent in tropical regions. That, of course, deprives organisms of the oxygen they need to survive.

Secondly, the warmer water gets, the less dense it becomes. At the surface, you end up with a band of hot water, with cooler waters in the depths, a layering known as stratification. “If you've ever gone swimming in a lake in the summer, if you're at the surface, it's nice and warm, and then you dive down and it gets cold pretty fast,” says Michael Behrenfeld, an ocean ecologist at Oregon State University. “That's the stratification layer that you're going through.”

In the ocean, this warm water acts like a cap that interrupts critical ecological processes. Normally, nutrients well up from the depths, providing food for the phytoplankton floating at the surface. Stratification prevents that. In addition, winds typically blow across the surface and mix that water down deeper, also bringing up nutrients. But with stratification, the contrast between the surface layer of warm water and the underlying cold water is so strong that it’s very difficult for wind energy to mix the two.

Together, all of these mean that phytoplankton in a warmer ocean are deprived of the nutrients they need. In response, they produce fewer of the pigments they use to turn sunlight into energy. “Phytoplankton will decrease their photosynthetic pigments because they're becoming more nutrient-stressed,” says Behrenfeld. “They don't need to harvest as much light because they don't have enough nutrients to do as much photosynthesis as they did before.” (Behrenfeld can actually see transformation in satellite imagery.)

They also reduce their pigment production because of their increased exposure to light. Without the wind mixing the water, they’re stuck in that cap of hot water at the surface for longer. With access to more light, they need less pigment in order to do the same amount of photosynthesis.

“The nutrient stress part is what we're really worried about,” says Behrenfeld. “If it's more stressed, there's less photosynthesis, which means less production of organic material for the food chain, which feeds fish.”

The warming of the world’s waters is creating winners and losers in the phytoplankton community. As temperatures go up, smaller species of phytoplankton tend to proliferate, which feed smaller species of zooplankton, which start to dominate the ecosystem. The larger species of zooplankton then have to spend more energy to gather enough of the tiniest phytoplankton to fill up. (Imagine surviving on a steady diet of cheeseburgers and then having to switch to sliders.)

“In a lot of cases, plankton can be quite resilient, but you get changes in the community composition,” says Kirstin Meyer-Kaiser, a marine biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The species that can best adapt to the warmer waters and changes in the food supply have an advantage. The zooplanktonic copepod species Calanus finmarchicus, for instance, typically lives at subarctic latitudes. “But it's penetrating farther and farther north,” says Meyer-Kaiser, “and becoming more and more common, and coming to dominate the community up there as you have temperatures rising and warm water influx.”

But the heat threatens other varieties of zooplankton, like the larvae of seafloor-dwelling creatures. These are cold-blooded animals, whose metabolisms speed up as temperatures rise. So the larvae of crustaceans can carry yolk from their mothers as they wander the open ocean, but they burn through that food faster. "They may not be able to disperse quite as far before they become desperate and absolutely have to settle down to the seafloor,” says Meyer-Kaiser. “Early life history stages, such as larvae, tend to be more sensitive to environmental changes than adults of the same species. So they could potentially not be able to survive in a heat wave.” That, of course, could impact fisheries, threatening the livelihood of subsistence fishers.

These ripple effects could well extend into Earth’s climate system. When phytoplankton grow, they sequester carbon, like plants do on land. When zooplankton consume them, their poop sinks to the seafloor, locking that carbon in the depths. In addition to the ocean waters themselves sequestering carbon from the atmosphere (carbon dioxide dissolves in water, which raises its acidity, which is how you get ocean acidification), this is a hugely important way that the planet removes some of humanity’s emissions.

As plankton attempt to adapt to a hotter habitat, “we are going to see dramatic changes at both species and community levels. This is a revamping of the entire Earth system,” says Meyer-Kaiser. “My prediction is the ecosystem will figure out ways to adapt. Sure, we'll lose biodiversity. Sure, we're going to lose important functions. But animals will continue to persist.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ancient DNA Reveals The Surprisingly Complex Origin Story of Corn

By Barbara Fraser December 13, 2018

Teosinte and maize look like very different plants, but it only took a few changes to teosinte's genes to get maize

In Mexico, corn tortillas rule the kitchen. After all, maize began evolving there from a grass called teosinte some 9,000 years ago, eventually becoming a staple consumed around the world.

But that spread presents a puzzle. In 5,300-year-old remains of maize from Mexico, genes from the wild relative show that the plant was still only partly domesticated. Yet archaeological evidence shows that a fully domesticated variety was being grown in South America more than 1,000 years before that.

“How can you have maize as part of a crop complex in South America when domestication isn’t even finished in Mexico?” asks Logan Kistler, curator of archaeobotany and archaeogenomics at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

He and his colleagues now believe they have found the answer in the southwestern Amazon basin, where people apparently continued domesticating an early “proto-maize” from Mexico, as well as other key crops such as manioc, squash and sweet potatoes.

Their findings, published today in Science, show that crop evolution doesn’t necessarily follow a straight line from wild ancestor to domesticated plant.

Maize that humans were nurturing in Mexico probably continued to contain genes from its wild relative because it was cross-breeding with nearby teosinte plants, Kistler says. But when travelers carried some seeds to South America, where they were planted far from their place of origin, the influence of teosinte faded.

Origins of Corn, Chocolate

Not long ago, such a detailed look at crop evolution would have been unthinkable, but huge leaps in technology in the past decade have allowed researchers to read a plant’s history in its genome.

A similar investigation recently bared the ancient roots of Theobroma cacao, whose seeds are made into cocoa powder and chocolate. Although chocolate as a ritual drink is usually associated with Mexico’s Aztec culture, recent analysis of plant residue points to South America, specifically Ecuador, as the place where cacao originated.

That’s not surprising, says Sonia Zarrillo, a paleoethnobotanist at the University of British Columbia in Canada, because the upper part of the Amazon River watershed in Ecuador and Peru has the largest number of wild cacao species.

That diversity is usually an indicator of the place where a plant originated and where domestication began. Molecular genetic analysis allows scientists like Zarrillo to confirm that by examining ancient DNA in pollen, seeds, and plant residue such as starch grains and microscopic mineral structures called phytoliths gathered from cooking utensils at archaeological sites.

Just as maize traveled south with traders, humans probably carried cacao seeds north by boat or over land to Mexico, Zarrillo says.

South American Crops

Many well-known crops have their roots in the Amazon Basin, probably because of the tropical region’s great biological diversity. The area where the scientists pinpointed Amazonian maize domestication, in what is now northeastern Bolivia and southwestern Brazil, is especially rich because it is in an “ecotone boundary” — a transitional area between different ecosystems, says Yoshi Maezumi, a tropical paleoecologist at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, who worked with Kistler on the maize study.

“It’s right on the border where you find the southern edge of the rainforest turning into savannah and grassland,” Maezumi says. “You have a mosaic of different types of landscapes and these areas are really rich for hunting, fishing and gathering.”

When maize arrived, inhabitants of that area were already cultivating rice and manioc, she says. They probably hunted in the nearby forest and fished in the rivers. Traveling by canoe along rivers and streams, they carried seeds and tubers to more distant villages, spreading the plants farther afield.

Corn’s Earliest Ancestor

By finding evidence of early maize domestication in the southwestern Amazon, scientists have solved one puzzle, but their findings raise new questions.

Kistler would like to work backward, using clues from ancient DNA to figure out what the earliest ancestors of modern corn looked like.

Maezumi hopes to explore how other tropical crops became domesticated, and what that can tell her about the people who cultivated them and environmental conditions at the time.

“What we’ve shown is that the process of domestication is more complicated than previously thought,” she says. “New (archaeological) sites are being discovered all the time. There’s so much new information coming out that’s changing the way we think about what humans were doing on the landscape and how they were using the land.”

Editor’s Note: In an earlier version of this story, a photo caption incorrectly stated the location of the University of Warwick, which is in the United Kingdom.

https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/ancient-dna-reveals-the-surprisingly-complex-origin-story-of-corn

0 notes

Text

A Fossil Museum Uses the Past to Reimagine Climate’s Future

A Fossil Museum Uses the Past to Reimagine Climate’s Future

As the La Brea Tar Pits & Museum undergoes a major redesign, its leaders hope it can do more to engage the public and educate visitors about the realities of climate change.

“Why did two-thirds of large mammals die at the end of the Ice Age?” asks Emily Lindsey, a paleoecologist and associate curator and excavation site director at the La Brea Tar Pits & Museum, home to over 3.5 million Ice Age…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

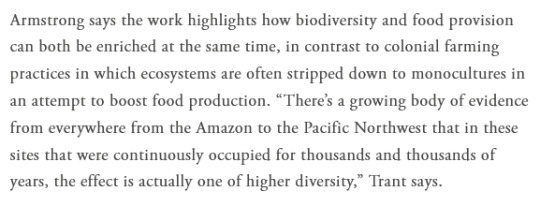

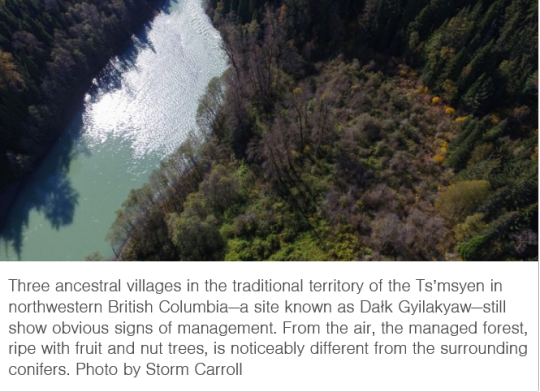

Imagine traveling back hundreds of years and finding your way up a salmon-spawning river in British Columbia to a small village. You walk into the trees and find yourself in a patch of forest dramatically different from the conifer growth around it. Small fruit and nut trees form the canopy, and there are clusters of berry bushes and cleared paths. The forest floor hosts tended herbs used for food and medicine. One child carefully peels moss from the bark of a pruned crab apple tree; another clears the ground next to a salmonberry bush.

Welcome to a temperate forest garden.

A new study shows that once-managed gardens like this are still distinct from -- and more biodiverse than -- the surrounding forest, even 150 years after Indigenous people were displaced by colonial settlers and the gardens abandoned. More diverse ecosystems are generally thought to be more resilient to environmental change and resistant to the incursion of alien species.

Chelsey Armstrong, a paleoecologist and paleobotanist at Simon Fraser University (SFU) in British Columbia, studied four sites: Dałk Gyilakyaw and Kitselas Canyon, both in Ts’msyen traditional territory in northwestern British Columbia, as well as Shxwpópélem and Say-mah-mit, both of the Coast Salish people of southwestern British Columbia. Each site hosted several villages that were occupied for thousands of years, up until the late 1800s. [...]

The garden plants they studied also had seeds that were about twice as large on average -- a trait typically associated with plants that bear larger fruits, which hints that people were purposely selecting for higher production.

The gardens contained 10 culturally significant species not normally found together, two of which fall completely outside their natural geographic range and were likely transplanted.

“Crab apple is a coastal species that likes its feet wet in the intertidal, and we’re finding it far inland in these sites, so people were moving them, in some cases, big distances,” says Armstrong.

“Hazelnut is doing the opposite, coming from the east and being moved toward the coast,” she adds. “We know that hazelnut doesn’t grow anywhere else in the area except for these village sites.”

Both species have enormous cultural importance to the Ts’msyen and Coast Salish people. Hazelnut packs a lot of calories into an easily picked nut that can be stored for up to five years. Crab apples, known locally as moolks, feature in origin stories of the areas, and were a high-status food stored over the winter months to supplement a fish-heavy diet.

“It’s amazing to think that the decisions that were made 150 years ago around stewardship and management persist today,” says Andrew Trant, an ecologist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario who was not involved with this study. The work shows that “what we do today has the potential to be persistent six generations from today.”

Armstrong says the work highlights how biodiversity and food provision can both be enriched at the same time, in contrast to colonial farming practices in which ecosystems are often stripped down to monocultures in an attempt to boost food production. “There’s a growing body of evidence from everywhere from the Amazon to the Pacific Northwest that in these sites that were continuously occupied for thousands and thousands of years, the effect is actually one of higher diversity,” Trant says.

The study details tie in with Indigenous knowledge, says Armstrong, who has been working with Indigenous partners and colleagues from the four First Nations on whose traditional territory the village sites are located: the Kitsumkalum, Kitselas, Sts’ailes, and Tsleil-Waututh. [...]

Oral histories also suggest that the job of tending forest gardens fell largely to children. Elder Betty Lou Dundas of Hartley Bay remembers pruning crab apple trees and clearing the ground around their bases to raise the trees’ productivity.

Willie Charlie, former chief of Sts’ailes, a Coast Salish First Nation, says no knowledge is ever truly lost from his community -- even after the assaults of colonialism and the residential school system.

“My grandfather said all of our teaching are still there on the land, so if somebody has a good mind and a good heart and the right intention, they can go out there and those messages are going to come to them,” says Charlie.

-------

Headline, images, captions, and text published by: Jessa Gamble. “Ancient Gardens Persist in British Columbia’s Forests.” Hakai Magazine. 9 June 2021.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Siberian cave hosted Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans—possibly at the same time

A decade ago, anthropologists shocked the world when they discovered a fossil pinkie bone from a then-unknown group of extinct humans in Siberia’s Denisovan Cave. The group was named “Denisovans” in its honor. Now, an extensive analysis of DNA in the cave’s soils reveals it also hosted modern humans—who arrived early enough that they may have once lived there alongside Denisovans and Neanderthals.

The new study “gives [researchers] unprecedented insight into the past,” says Mikkel Winther Pedersen, a molecular paleoecologist at the University of Copenhagen who was not involved with the work. “It literally shows what [before] they have only been able hypothesize.”

Humans—including Neanderthals and Denisovans—are known to have occupied Denisova Cave for at least 300,000 years. Among the eight human fossils unearthed there are the pinkie, three bones from Neanderthals, and even one from a child with one Neanderthal and one Denisovan parent. Read more.

368 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do u know so much stuff?

I'm a paleoecologist and my best friend is a cultural historian

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I'm Learning Russian

It's been a while since I was last here on this site, and since I seem to be back-back for good(?), I figured I'd update everyone following me on what's going on right now.

And I figured I'd make a separate post talking specifically on why I've chosen to learn Russian (instead of Serbian).

First off, I still wish I could learn Serbian due to family reasons, but there's a severe lack of sources for me to use. Duolingo ain't got shit regarding the language. I wouldn't have cared if it was listed simply as Croatian! I just wanna learn the language!

Thanks to the whole anti-communist propaganda in the states, many Americans (whether by ignorance alone, by design, or some combination thereof) would hear a Slavic language and get pissy. At least this is what I think is likely the reason behind why it can be so hard in some areas to find just books on a Slavic language. If you're lucky to find any, it's always Russian. The area I live in has plenty of Polish, Russian, and Serbian populations (albeit descendants of immigrants, but you get the idea). You're think they'd have a decent amount of books at the local library. The best I could find was a book meant to teach how to translate written Russian (apparently you have to have a ridiculous aptitude for high-difficulty languages or have to already be familiar a bit with it?) and a Polish For Dummies book. That's it.

There aren't any community colleges nearby that I can find that event teach foreign languages at all (this is a right-wing-heavy area, so surprise-surprise).

But in this country as a whole, the only Slavic language I can find that you will commonly find in colleges and universities if any Slavic language at all is supported is Russian.

So that's reason number one: accessibility.

Another reason is that there's quite a bit of stuff happening in the country that due to Americans not expecting to take on foreign languages on a regular basis, let alone a complex one, the ruling class could easily claim what Russians are saying whether it's a soundbyte, a video with audio, or signs and posters and such. They're relying on the American people to be completely ignorant of the language so they could spin whatever they wanna say however they need it to say. (This would largely be fux news' area of expertise, as they've been doing so recently with the protests in Cuba by not only showing protests that occurred in Florida and passing them off as Cuban protests in Cuba, but they straight-up blurred out posters because someone might know how to speak Spanish.)

On top of this, there's something boiling in Russia, so if the Russian people need help and ask Americans for advice, it would be nice if some Americans spoke their language, instead of relying on Russians (and anyone not American in general) to know English to some extent.

So there's reason number two: avoiding misinformation and misunderstandings.

I don't have to tell you twice that climate change is happening right now and that we may not see the climates of many regions go back to normal within our own lifetimes even if we did everything right.

However, worst case scenario, what if we were too late? Where in the would could remain habitable for humans? There's Greenland, Canada, Antarctica (which would be warred over for territory because of course it would), and then there's Russia. Russia is semi-landlocked thanks to the arctic ice on the northern coasts, but once that melts, they would easily be able to trade by sea. They also have a lot of currently uninhabited land that, in this worst case scenario, would be thawed out and quite fertile and suitable for agriculture, especially for the potential billions (remember, we're passed the 7 billion population point) that would emigrate just to be able to survive. This means that if you wanted to move to Russia, it's probably best to learn the language.

That's reason number three: it will be the largest habitable landmass on the planet if we cannot bring about a chance of reversal to climate change.

The last reason is due to the possibility that if I went back to school for what I ultimately want to be (paleoecologist), my interests (pleistocene ecology) may lead me to digging up frozen carcasses out of the Russian permafrost. There's also an attempt in a Pleistocene Park in the making right now (all that's missing is the mammoth which we will never successfully clone) to bring back fauna we still have that once existed there to help with the land's ecosystem in the Russian steppe. And so far, it's succeeding in its goals. And as a paleoecologist, this would be right up my alley. But knowing the language would be incredibly helpful, too!

Russian isn't actually hard for the reasons many "top x videos" claim it to be. The alphabet isn't that hard, to be honest. It's the cases, which is where I'm stuck at right now.

Duolingo is not a good way to learn a language, as they do not teach grammar or cultural context. The app has become a game that makes you rely on memory and hopes you'll catch on.

No other apps that I have found will teach the grammar in a beginner-friendly way for free, either. I'm poor, and can't afford this shit, so I'm hoping to borrow that library book I mentioned earlier (now that I've learned the alphabet quite nicely) might be able to give me a better idea in a way that I can best understand it.

For now, I'm focusing on keeping up my practice as well as building a nice vocabulary bank. That's going to make learning the cases much easier. The good news is my husband is also interested in learning the language and even he learned the alphabet without much of an issue. So I have someone to practice with.

Hilariously, like with Spanish, I have a problem with a foreign language... I can read it fine, I can hear it okay, but writing it? Eh.. And speaking it from memory? Holy shit I struggle. But my husband hasn't had much of a chance to really practice thanks to his job, so maybe it's the lack of practice?

Regardless, learning independently is going to be a nice primer for when (maybe if, who knows) we can finally go back to college once we've moved with my parents (long story) because the university in the area they want to move to does offer Russian. If things go well, I plan to take more than 2 levels (the university requires all students to take at least 2 levels of a foreign language).

So yeah. That's why I'm learning Russian. It's actually really fun, and I do watch vlogs from Russians on YouTube so I get a better understanding of their culture, too. I'm jealous they don't have this fucked up concept of a "lawn" like America does. All it is with the houses and dachas is native plants and fruits and veggies they decide to grow. Lucky...

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Excerpt from this story from Grist:

It is a story repeated throughout the fossil record: When the climate changes, so does the arrangement of the world’s plants. Species move back and forth toward the poles, up and downslope. Some species grow more common, others rarer. Species arrange themselves together in new combinations. The fossil record reveals plants for what they are, as mobile beings. For plant species, migrating in response to climate change is often a matter of survival.

As human-generated greenhouse gas emissions cause the world to rapidly warm, this movement is once again under way. Scientists have observed plants shifting toward the poles and upslope. They’ve noted old ecosystems suddenly replaced by new ones, often in the wake of fire, insect outbreaks, drought or other disturbances. They’ve observed an increase in the number of trees dying and watched as a growing number of the world’s biggest and oldest plants, including the baobabs of Africa and the cedars of Lebanon, have succumbed. Just this month, scientists announced that the Castle Fire, which burned through California’s Sierra Nevada last year, singlehandedly killed off more than 10 percent of the world’s mature giant sequoias.

So far, many of these changes are subtle, seemingly unrelated to one another, but they are all facets of the same global phenomenon — one that scientists say is likely to grow far more apparent in the decades to come.

Scientists debate what this floral rearrangement will look like. In some places, it may take place quietly and be easily ignored. In others, though, it could be one of the changing climate’s most consequential and disruptive effects. “There’s a whole lot more of this we can expect over the next decades,” said University of Wisconsin-Madison paleoecologist Jack Williams. “When people talk about wildfires out West, about species moving upslope — to me, this is just the beginning.”

The species whose migration we’ll likely notice first are those of agricultural, commercial or cultural importance. University of Maine paleoecologist Jacquelyn Gill points to sugar maple, whose range scientists project will shift far to the north in the coming decades. “As an ecologist, I’m happy that sugar maple is tracking the climate,” Gill said — it is a sign of resilience. On the other hand, she said, “As a person who lives in Maine and loves maple syrup, I am extremely concerned for the impact of sugar maple’s movements on a food I care about, on my neighbors’ livelihoods, and on the tourist industry.”

These shifts in species’ ranges also have serious implications for conservationists. Experts say the changing climate means that Sequoia National Park will eventually be left without its sequoias, Joshua Tree National Park without its Joshua trees. As with Gill’s sugar maples, this is distressing from a human perspective, though potentially of little importance from the plants’ perspective. The question is whether sequoias, Joshua trees, and countless other plants will be able to reach newly suitable habitats. For decades, scientists have debated whether plants would be able to track the rate of climate change, and whether people should intervene to help rare, isolated species reach more suitable habitat.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

The anonymous account, @Sciencing_Bi, first began tweeting in 2016, and over the years claimed to be a queer indigenous woman, a survivor of sexual harassment, and an anthropologist affiliated with Arizona State University (ASU). Through her seemingly candid stories about her own experiences, @Sciencing_Bi built up a loyal following, including McLaughlin, who frequently acted as a go-between to help preserve @Sciencing_Bi’s anonymity.

But after McLaughlin announced @Sciencing_Bi’s death from COVID-19 several days ago, people began trying to identify her, and her story began to fall apart. Scientists who had considered @Sciencing_Bi an online friend turned from mourning her death to accusing McLaughlin of inventing her outright. “Creating a fake pseudonymous account and pretending various marginalized identities is wrong. It’s evil,” tweeted Jacquelyn Gill, a paleoecologist at the University of Maine who had been friendly with @Sciencing_Bi.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

we actually know a lot about ancient climates and ecosystems. If you look it up, there's loads of info. Scientists know what theyre talking about and theres a reason why certain things are ruled out. Geologists study the chemistry and makeup of ancient sediments and rocks, while paleoecologists can analyse what fossils were present. Together and with others, they can accurately reconstruct ancient climates and ecosystems

That’s comforting to hear.

I was worried we’re still at the point where they ignore the concept of things maybe being less monstrous than what we used to think they look like.

1 note

·

View note

Text

-

#just read an article about climate change#written by a climatologist#which is great#one of the top comments were saying that a climatologist isn't qualified#to talk about climate#"You need to speak with a paleoecologist geologist and physicist#Climatologists deal with weather not climate#shut up andrew#squish posts

0 notes