#paleoanthropology

Text

#bajirao mastani#renaissance#長月翠#trans mtf#silvia caruso#spn#book recommendations#brittany elizabeth#paleoanthropology#萝莉视频#asian fashion#heartbreak#social anxiety#austin butler

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

#paleoanthropology#hope beel#Mary Kate Olsen#austin butler#oculus#formula 1#studyspiration#lgbt memes#vaporwave#i sell pix#weddings

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analysis of data from dozens of foraging societies around the world shows that women hunt in at least 79% of these societies, opposing the widespread belief that men exclusively hunt and women exclusively gather. Abigail Anderson of Seattle Pacific University, US, and colleagues presented these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on June 28, 2023.

A common belief holds that, among foraging populations, men have typically hunted animals while women gathered plant products for food. However, mounting archaeological evidence from across human history and prehistory is challenging this paradigm; for instance, women in many societies have been found buried alongside big-game hunting tools.

Some researchers have suggested that women's role as hunters was confined to the past, with more recent foraging societies following the paradigm of men as hunters and women as gatherers. To investigate that possibility, Anderson and colleagues analyzed data from the past 100 years on 63 foraging societies around the world, including societies in North and South America, Africa, Australia, Asia, and the Oceanic region.

They found that women hunt in 79% of the analyzed societies, regardless of their status as mothers. More than 70% of female hunting appears to be intentional—as opposed to opportunistic killing of animals encountered while performing other activities, and intentional hunting by women appears to target game of all sizes, most often large game.

The analysis also revealed that women are actively involved in teaching hunting practices and that they often employ a greater variety of weapon choice and hunting strategies than men.

These findings suggest that, in many foraging societies, women are skilled hunters and play an instrumental role in the practice, adding to the evidence opposing long-held perceptions about gender roles in foraging societies. The authors note that these stereotypes have influenced previous archaeological studies, with, for instance, some researchers reluctant to interpret objects buried with women as hunting tools. They call for reevaluation of such evidence and caution against misapplying the idea of men as hunters and women as gatherers in future research.

The authors add, "Evidence from around the world shows that women participate in subsistence hunting in the majority of cultures."

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Acclimation is actually an insane thing that our bodies do and its amazing how rapidly we adjust to a new environment.

It's like "Oh you wanna live in a place where the average temperature is literally 10 TIMES hotter than we're used to with almost 100% humidity so sweat isn't as effective? Ok give me a few days to adjust than we're good just some more sweat as we get used to it"

"What the fuck you wanna move to a place that's THOUSANDS OF FEET up in the air? A place without enough OXYGEN for you to function fuck...Ok give me a few days to MAKE MORE BLOOD AND MAKE YOUR HEART BIGGER then you'll be alright."

On a generational basis it's even funnier cause within a few dozen generations we can actually adapt to like any environment. People from Africa and Aboriginals are usually darker because Melanin acts as sunscreen in a place where they get too much sun and during a time where people didn't wear many clothes or have indoor shelters like today.

But as humans migrated north to latitudes where the Sun isn't constantly raining down an endless beam of death and cancer and started to wear more clothes due to it being colder they started lacking in Vitamin D and that leads to a whole HOST of other health issues related to births, cancers and other shit so we started lessening the pigment in our Skin in order to get as much Vitamin D that we can. This happened within a few generations as far as we're aware and like this shit is happening on a SUPER Fast biological scale.

For a kinda poor metaphor, the rate at which humans adapt to massively different environments to best live in is like how Speed runners can complete OOT within like 5 minutes compared to the 27 hours it takes to beat casually

Edit:So apparently I am a dumbass when it comes to tempreture as the way we measure tempreture is not in fact liniar and is more logrimtic in nature than I was led to belive by math. There isn't a 10X increase in tempreture. But still you can go from living in Norway in the Winter to the Tropics/Sahara in a short period of time and our bodies adapt concerningly fast

#human#humans are cool#humans are awesome#anthropology#archeology#biology#learning#science#paleoanthropology#humans are weird#humans are space orcs

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about how much of a full circle moment the Blue Marble photograph was/is.

This image was taken in 1972 by the crew of Apollo 17 on their way to the Moon - the last humans to ever visit Luna, to date.

And it just so happens that the approximate center of the image is the southeastern region of Africa, under bright noonday sun.

And it just so happens that the southeastern region of Africa, from the Cape to the Horn, is where our most ancient prehuman ancestors, the australopithecines, originally evolved.

Dinkʼinesh ("Lucy"), the holotype of Australopithecus and the genesis of our modern understanding of our species' origins, was not discovered until two years after this photo was taken. In this image, the bones of our most treasured ancestor still lie beneath the earth of Qadaqar, Ethiopia.

This is not just an image of our home planet. This is an image of our cradle. This is where the humanity was born, four million years ago.

What a marvelous coincidence, no?

#spy has thoughts#i'm not crying you're crying#my deep and abiding love of humanity knows no bounds#science#space#paleoanthropology#anthropology

466 notes

·

View notes

Text

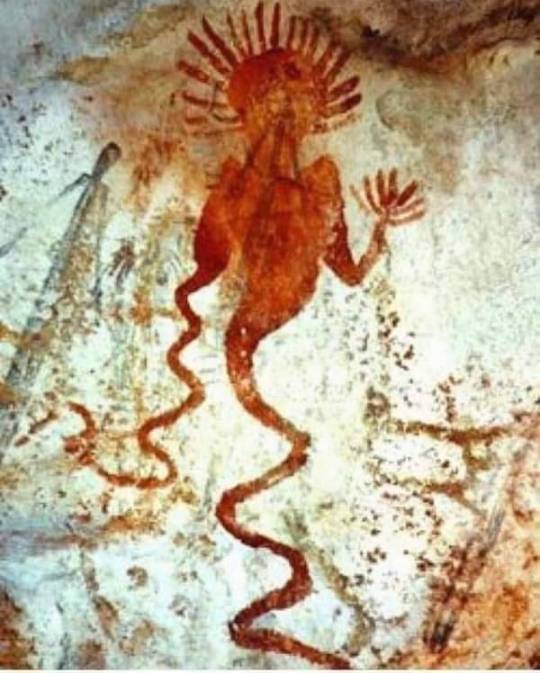

Images drawn in Altamira caves around 36000-11000 BC, Spain

744 notes

·

View notes

Text

my paleo inspired monotypes 💞

#my art#art#paleoart#paleolithic#cave paintings#early humans#printing#monotype#monoprint#color pencil#collage#palaeoart#archaeology#paleoanthropology

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Individual houses were typically in use for between fifty and 100 years, after which they were carefully dismantled and filled in to make foundations for superseding houses. Clay wall went up on clay wall, in the same location, for century after century, over periods reaching up to a full millennium. Still more astounding, smaller features such as mud-built hearths, ovens, storage bins and platforms often follow the same repetitive patterns of construction, over similarly long periods. Even particular images and ritual installations come back, again and again, in different renderings but the same locations, often widely separated in time....

as individual houses built up histories, they also appear to have acquired a degree of cumulative prestige. This is reflected in a certain density of hunting trophies, burial platforms and obsidian - a dark volcanic glass, obtained from sources in the highlands of Cappadocia, some 125 miles north. The authority of long-lived houses seems consistent with the idea that elders, and perhaps elder women in particular, held positions of influence. But the more prestigious households are distributed among the less, and do not appear to coalesce into elite neighborhoods.

a description of Çatalhöyük, a neolithic city from 7,400 bc. from the dawn of everything, by davids: graeber and wengrow.

this city remained settled for 1,500 years - "roughly the same period of time that separates us from amalafrida, queen of the vandals in .. ad 523"

#eezordalf's wisdom#the dawn of everything#david graeber#david wengrow#anthropology#paleoanthropology#books#prehistory#neolithic#Çatalhöyük#catalhoyuk#history#unfocus your eyes and let the vast maw of time take you#wizardblr#wizardposting

597 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twenty thousand years ago, someone dropped a deer-tooth pendant in a cave in southwestern Siberia, where it lay until archaeologists excavated it in 2019. Now, researchers have caught a glimpse of its last wearer. After years of effort, Elena Essel, a graduate student at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (EVA), developed a way to extract DNA embedded in an artifact’s porous surface by sweat and skin cells. Her team’s analysis of the ornament, reported this week in Nature, shows it once adorned a woman whose ancestry lay far east of the cave.

“It’s the first time to my knowledge that we have a nondestructive way to extract DNA from Paleolithic artifacts,” says co-author Marie Soressi, an archaeologist at Leiden University. The technique promises a window into how, and by whom, ancient ornaments and tools were used. Human DNA gleaned from their surfaces could offer “new insight into cultural practices and social structure in ancient populations,” says evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiro of the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The EVA team found some of the ancient DNA came from wapiti, the species of elk whose tooth was used to make it. But some DNA was from a female modern human; its sequence revealed she was most closely related to people of the Maltinsko-buretskaya culture, known to have lived 2000 kilometers farther east near Lake Baikal—and who are among the ancestors of Siberians, Native Americans, and Bronze Age steppe herders. By comparing the DNA from both the woman and the elk with other ancient samples, the researchers dated the pendant to between 19,000 and 25,000 years ago.

The paper has come out just in time for a new field season, Essel says. She has a request for colleagues as they unearth new artifacts: “Please, please, please wear gloves and face masks if you want to look at the DNA of the people who were making these things and using them.”

In theory, such analyses are most promising for artefacts made from animal bones or teeth, not only because they are porous and thereby conducive to the penetration of body fluids (for example, sweat, blood or saliva) but also because they contain hydroxyapatite, which is known to adsorb DNA and reduce its degradation by hydrolysis and nuclease activity. Ancient bones and teeth may therefore function as a trap not only for DNA that is released within an organism during its lifetime and subsequent decomposition but also for exogenous DNA that enters the matrix post-mortem through microbial colonization or handling by humans.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06035-2

#elena essel#marie soressi#paleoanthropology#archaeology#dna analysis#wearer of adornment#identified by#25000 year old sweat#wild

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sorry to all paleoanthropologists. But it's true!

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

#reddit aint too bad sometimes#anthropology#memes#biology#science#ussy#human history#evolution#human evolution#evolutionary biology#paleoanthropology#paleontology#homo neanderthalensis#neanderthal man#neanderthals#homo sapiens#history

336 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a growing body of physiological, anatomical, ethnographic, and archaeological evidence to suggest that not only did women hunt in our evolutionary past, but they may well have been better suited for such an endurance-dependent activity.

We are both biological anthropologists. I (co-author Cara) specialize in the physiology of humans who live in extreme conditions, using my research to reconstruct how our ancestors may have adapted to different climates. And I (co-author Sarah) study Neanderthal and early modern human health. I also excavate at their archaeological sites.

It’s not uncommon for scientists like us—who attempt to include the contributions of all individuals, regardless of sex and gender, in reconstructions of our evolutionary past—to be accused of rewriting the past to fulfill a politically correct, woke agenda. The actual evidence speaks for itself, though: Gendered labor roles did not exist in the Paleolithic era, which lasted from 3.3 million years ago until 12,000 years ago. The story is written in human bodies, now and in the past.

[...]

Our Neanderthal cousins, a group of humans who lived across Western and Central Eurasia approximately 250,000 to 40,000 years ago, formed small, highly nomadic bands. Fossil evidence shows females and males experienced the same bony traumas across their bodies—a signature of a hard life hunting deer, aurochs, and woolly mammoths. Tooth wear that results from using the front teeth as a third hand, likely in tasks like tanning hides, is equally evident across females and males.

This nongendered picture should not be surprising when you imagine small-group living. Everyone needs to contribute to the tasks necessary for group survival—chiefly, producing food and shelter, and raising children. Individual mothers are not solely responsible for their children; in forager communities, the whole group contributes to child care.

You might imagine this unified labor strategy then changed in early modern humans, but archaeological and anatomical evidence shows it did not. Upper Paleolithic modern humans leaving Africa and entering Europe and Asia show very few sexed differences in trauma and repetitive motion wear. One difference is more evidence of “thrower’s elbow” in males than females, though some females shared these pathologies.

And this was also the time when people were innovating with hunting technologies like atlatls (spear throwers), fishing hooks and nets, and bow and arrows—alleviating some of the wear and tear hunting would take on their bodies. A recent archaeological experiment found that using atlatls decreased sex differences in the speed of spears thrown by contemporary men and women.

Even in death, there are no sexed differences in how Neanderthals or modern humans buried their dead or the goods affiliated with their graves. These indicators of differential gendered social status do not arrive until agriculture, with its stratified economic system and monopolizable resources.

All this evidence suggests Paleolithic women and men did not occupy differing roles or social realms.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Humans are dumb and predictable, we use it to learn.

So honestly one of my favorite parts about being an Anthropology Student and looking specifically into Paeleoanthropology is that we know the common human behaviors that have been done even though it like, damages our teeth and bones but we do it anyways and use that to determine things about us and others.

One of these things is that Humans, even though it is damaging to our teeth tend to use our chompers as a Third Hand, like we hold onto so much stuff with it when we want to hold it steady or just dont have the room in our hands for it. We have been doing this hundreds of thousands of years and Paleoanthropologists in Spain have used that to determine if Homo Heidelbergensis, our Most Recent Hominin Ancestor(Basically the transition between Erectus and Sapiens) was mainly right handed or left handed.

What they did was look at the damage marks fossilized teeth had, and saw the patterns, different damage patterns emerging if your holding say a bone in your teeth as you scrape the meat off of it with your stone tool. Weather your scraping with your left or right hand makes a distinctive pattern, and through that you can determine which hand they favored.

As it turns out Heidelbergensis was largely Right handed! or at least the population that is in Sima De Los Huesos in Spain.

#science#anthropology#archeolo#paleoanthropology#fun facts#humans are weird#humans are dumb#College#i'm procrastinating

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

#長月翠#sexy content#trans mtf#valentines day#silvia caruso#dylan obrien#spn#icons camila cabello#ive#motylki#paleoanthropology#metalocalypse#萝莉视频#hope beel

132 notes

·

View notes