#paul cartledge

Text

“How Reliable is Herodotus’ Account of the Persian Wars?

Answer by Paul Cartledge

Herodotus was not just any old historian but the founder of an entire intellectual discipline and practice, or craft, the one that I am honoured to try my hand at myself. Opinions differ today, as they always have done, on what exactly a historian’s chief task or aim should be, but Herodotus made a pretty good stab at adumbrating it in the famous Prooimion or Preface to his Histories (‘Researches’, ‘Enquiries’): he wished both to record for posterity and to celebrate ‘great and wonderful deeds or achievements (erga)’ and – above all, N.B. – to explain them. In his particular case what he wished to explain above all was why and how and thanks to whose responsibility Greeks and non-Greeks (principally Persians) had come to fight each other.

He had in mind as his subject what we today call the ‘Persian Wars’ or (more accurately) Helleno-Persian Wars, as those were fought out by land and sea on either side of the Aegean at the far eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea between 490 (Battle of Marathon) and 479 BC/BCE – or from 499 to 479, if one includes also the essential preliminary ‘Ionian Revolt’ (499-4), since this was the first occasion on which Greeks, then many of them subjects of the mighty Persian empire, had engaged in warfare with their ‘barbarian’ (non-Greek) masters in pursuit of the ideal of political freedom. That (unsuccessful) revolt gave Herodotus, himself an Eastern Greek from Asia Minor (Halicarnassus) and born c. 485 a Persian subject into a mixed Greek-barbarian family, his own dominant theme.

It was always clear to Herodotus where his linear chronological narrative would end – 479, with the final victory for those (few) Greek cities led by Sparta and Athens who had dared to resist the intended Persian conquest of all mainland Greece led by Emperor Xerxes. But where to begin? Herodotus boldly chose what we call the mid-6th century or c. 550 BCE for his starting point, but how could he possibly claim to know or at any rate confidently believe anything at all about events and processes ongoing some 70 years or two to three generations before his own birth? Given that he seems not to have been able to speak or read any language other than his own Greek (he wrote in the Ionic dialect but spoke in Doric), and given that the Hellenic world of the mid-6th century was not a world either of extensive official public documentation or of extensive prose-writing of a descriptive, factual nature, he had no choice but to become not only the world’s first historian but also the world’s first oral historian. That is to say, the chief type of evidence – not quite the only, since he does quote some documents and cite some physical monuments– that he gathered from about 450 to 430 was the oral testimony of either face-to-face or second-hand informants. Those informants moreover were either native Hellenophones or non-Greeks with a sufficient command of Greek.

It is hugely to his credit that Herodotus evolved a sophisticated hierarchy of value in interpreting such oral testimony, a hierarchy according to reliability. Top of the table was what he called opsis, or autopsy, meaning first-hand testimony whether of his own or of those of his informants who had actually viewed or participated in the events related, including evidence of physical monuments (another meaning of erga). After that, some way after, came what he called akoê or hearsay evidence, evidence that might reliably go back ultimately as far as two to three generations (but no farther) before his own time. Both types of evidence however were then further subjected to the reliability test: were his informants to be trusted – or might there perhaps be reasons why they would provide him knowingly or unknowingly (‘false memory syndrome’) with false testimony both as to facts and as to their interpretation?

At this point it’s necessary to state unequivocally that Herodotus was in no way an official historian, indeed his work has been characterised as the very denial of official history – that is, of the sort of records – or propaganda sheets – put out by middle eastern rulers or priestly castes. But even if he was not compiling and composing in the interests of any particular state or power-group, does that mean he was always himself disinterested either in what he chose to relate or in how he chose to relate it? Here Herodotus is vulnerable to two kinds of negative critique: first, that in interpreting the deeds of humans he nevertheless was too quick to invoke the notion of supernatural or divine intervention as an explanatory mode, that he was in short too theological; second, that he did not always sufficiently perceive the bias of his informants, whether they were members of an aristocratic Athenian family or members of a hereditary Egyptian priesthood. Both those critiques seem to me to have some force. And Herodotus himself was clearly very aware of the second: in response he claimed, somewhat speciously, that it was his job to ‘relate what he was told’ and that it shouldn’t be assumed he necessarily believed it. (I should probably here add that I do not myself believe the hyper-criticisms that have been levelled at Herodotus since antiquity, to the effect that he just made things up, or that, for example, he didn’t in fact view the monuments and cities abroad such as Babylon that he claimed or implied he had seen.)

Reliability, finally, operates on several levels – from a particular detail of his account of say the finally decisive Battle of Plataea all the way up to the alleged motivation of Xerxes in planning and effecting his simply massive expedition (though not as massive as Herodotus believed – here he was certainly guilty of considerable factual inaccuracy). If we make due allowance for an excess of theology, for a weakness for large numbers, and for an occasional prejudice in favour of or against a particular key player (for Athens at the Battle of Salamis, for instance, or against King Cleomenes I of Sparta and Themistocles, or – as Plutarch vehemently protested – medizing Thebes), then I think we may confidently say that Herodotus’ historical judgement is remarkably reliable given the conditions in which it had to be exercised.

I have left to the end a bit of a ‘stinger’. Almost all that I have written above applies to Herodotus the historian of the Helleno-Persian Wars conceived pretty much as we would frame that still vitally important topic today. Herodotus, however, deployed and depicted a far broader and richer canvas, since besides being that historian he was also what we would call today a pioneer ethnographer and comparative social anthropologist, interested to discover and compare the nomoi – laws and customs – of a multiplicity of non-Greek peoples living adjacent to the Hellenes, above all others the Egyptians (book 2) and a variety of what he called ‘Scythians’ (book 4). In this area Herodotus’s vulnerability to deception, disinformation or sheer ignorance was far greater, and his reliability correspondingly far smaller.

Further Reading suggestions: With apologies for apparent self-promotion, I develop the above discussion at greater length in my introduction to Tom Holland’s bold new Penguin Classics translation (London 2014). See also my 2017 (Chalke Valley History Festival) History Hub blogpost. An inventive way of re-reading Herodotus is William Shepherd’s The Persian War in Herodotus and Other Ancient Voices (Oxford 2019). A particularly good ‘very short introduction’ to Herodotus is Jennifer T. Roberts’ Herodotus (Oxford 2011). Roberts is also the editor of the excellent Norton Critical Edition of the Histories as translated by Walter Blanco and accompanied with a wide variety of supporting essays by Blanco (London 2013).’

Source: the site of Herodotus Helpline ( https://herodotushelpline.org/how-reliable-is-herodotus-account-of-the-persian-wars/).

Very good text from a very important Classicist. My only criticism is that I think that Pr. Cartledge does not take sufficiently into account the fact that Herodotus’ ethnography, despite its inevitable flaws and errors, offers often accurate and important information on the customs of non-Greek peoples (and even in other cases in his ethnography, in which Herodotus is mostly wrong, there is a kernel of truth in what he relates or at least he preserves aspects of how some ancient peoples of his time showed themselves, their past, and their neighbors).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a great episode! I even learned one new thing lol. Can you guess what new thing I learned??

#athens#democracy#Paul Cartledge#I don't trust him on Alexander but def on Athens and Sparta#(look he called H a dolt so. BYE)#Spotify

1 note

·

View note

Photo

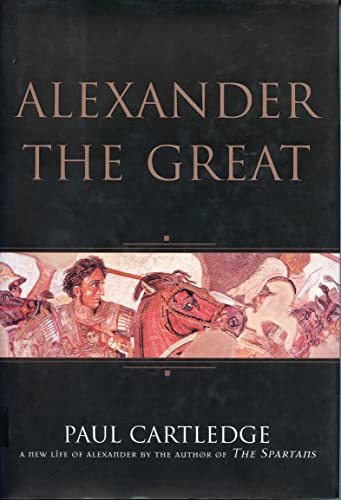

Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander

"Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander" by Paul Cartledge offers a detailed yet accessible exploration of the legendary figure's life and legacy. The author's expertise and engaging storytelling provide fresh insights into Alexander the Great's conquests and their historical significance. This book is recommended for scholars and general readers alike.

Alexander the Great's profound impact on Roman culture is undeniable, particularly when considering the fusion of Greco-Oriental influences during the Hellenistic era, which permeated Rome and, subsequently, Western Europe. His conquests paved the way for cultural diffusion and laid the groundwork for religious and imperial ideologies. His ideological legacies include figures like Pompey and Caesar. The territories Alexander the Great once controlled formed the foundation of Rome's eastern dominion, often considered the culturally and economically richer half of the empire.

However, understanding Alexander himself proves challenging due to conflicting ancient sources and continuous reinterpretations throughout history, often reflecting the agendas of interpreters.

In Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander, Paul Cartledge offers a captivating and comprehensive new examination of Alexander the Great. With his trademark storytelling prowess, Cartledge, chair of Cambridge University's Classics Department, guides readers through the life and conquests of Alexander with precise detail and an engaging narrative that balances discussion on Alexander's achievements with acknowledgment of places where we lack historical evidence.

Cartledge challenges prevailing notions about Alexander's motivations, particularly regarding Alexander's aim of spreading Hellenism. Cartledge argues that while Alexander was indeed attached to Hellenism, his driving force was personal glory and conquest. This nuanced perspective adds depth to our understanding of Alexander, presenting him as a complex figure driven by ambition and a thirst for success.

Central to Cartledge's exploration is Alexander's military genius. Through detailed chronicles of Alexander's battles with the Persians, Tyrians, and Babylonians, Cartledge highlights the young leader's strategic brilliance and innovative tactics. He demonstrates how Alexander's love of hunting served as a metaphor for his approach to warfare, as he adapted hunting strategies such as the surprise attack to achieve military success. This analysis sheds light on Alexander's mindset and sheds new light on his military achievements.

The book is enriched by many appendixes, including a glossary and an extensive bibliography, which enhance the reader's understanding and provide valuable resources for further exploration. Cartledge's skillful storytelling brings history to life, making the ancient world feel vivid and immediate. His vivid descriptions and storytelling make for an absorbing read that will appeal to both scholars and general readers alike.

Overall, Alexander the Great: A New Life of Alexander is a masterful biography that offers fresh insights into the life and legacy of one of history's most iconic figures. With its diligent research, engaging narrative, and nuanced analysis, this book is sure to become a definitive work on Alexander the Great for years to come. Whether the audience is a seasoned scholar or a casual reader with an interest in ancient Greece, this book is a must-read.

Continue reading...

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know any sources to find out about ancient worship of heroes? Thanks

I do. That's a well documented topic, fortunately.

Before I start listing modern studies, let me recommend Pausanias' Description of Greece. Pausanias was particularly interested in local cults and religious anecdotes, so he's recorded a fair amount of hero cults that we probably would have never known about otherwise.

Now, when it comes to studies, I would prioritize these for a start:

The Sacrificial Rituals of Greek Hero-Cults by Gunnel Ekroth

Greek Heroine Cults by Jennifer Larson

Pindar and the Cult of Heroes by Bruno Currie (part 2 is entirely focused on the ins and outs of heroization)

You will also find relevant chapters in more general works like Cults and Rites in Ancient Greece by Michael H. Jameson and Paul Cartledge (chapters 1, 2, 8) by or Animals in Ancient Greek Religion by Julia Kindt (chapter 2 focuses on the ritual differences in sacrifice between heroes and gods etc).

When you want to start getting deeper, remember to also look at open source thesis manuscripts. There are a few out there that touch upon hero cult in a way or another. You might also find relevant information in more literary analyses about Homeric heroes, but they won't focus on the cult aspect as much as the works I've listed above.

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I've really enjoyed your blog-- there's a lot of good information on it. In fact, I just wrote a novel set in ancient Thebes, set in 335 BCE, right before Alexander's attack. However, I'm a little scared to write the sequel, because Alex is going to show up in it as a major character. He is SO famous, and there's so many books about him, that I hardly know where to begin.

So, do you have any specific books you recommend, like any good starter bios or anything else that would be good for this specific setting? (Specifically against the destruction of Thebes and right before the invasion of Persia.)

Thank you so much!

Some Useful Bibliography on Alexander (and Thebes)

Thank you! And sorry for the delay. The queries in my inbox tend to be feast or famine. LOL

In terms of information on Alexander, I would start with the brand new Cambridge Companion to Alexander the Great, edited by Daniel Ogden. It has many of the leading scholars. On Alexander and the Greeks in particular, see my dear friend Borja Antela’s chapter. This is now what I’d consider the best intro resource on Alexander for the interested non-specialist, especially as it’s reasonably priced. The bibliography will help a lot. For Macedonia itself, Carol Thomas has Alexander and His World (which I’ve used teaching) and Carol King has Ancient Macedonia. Both are good, one-book introductions.

If you’ve not already, you’ll want to consult Mark Munn’s chapter “Thebes and Central Greece” in The Greek World in the Fourth Century, Larry Tritle, ed. Paul Cartledge also has a book Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece, but he’s a Spartan specialist. Lately, publishers have had him write on other subjects—not always to good effect, as per his book on Alexander, imo. But I’ve not read this one so can’t comment. I think Thebes is closer to his usual bailiwick.

James Romm did a book The Sacred Band., although like Cartledge Romm is all over the place. Same cautions apply. And I’ll also offer the counter-proposal that the band was not pairs of lovers, by David Leitao, "The Legend of the Sacred Band," in The Sleep of Reason by Martha Nussbaum and Juha Sihvola, eds. His view is not a homophobic diss; it’s a source problem. Plutarch is our sole source for the lovers bit, and he’s notoriously unreliable on some facts, especially when he has an ulterior message.

The more I study Plutarch, the less I trust him. LOL

Last, another friend and colleague, Jenn Finn has written a bang-up chapter on the destructions of both Thebes and Persepolis, for the upcoming collection I edited, so I got a preview. “Urbicide, Memory Sanctions, and the Perso-Macedonian Dynasty.” I’m not sure when the collection will be out, but certainly not before late 2024, and more likely 2025. She might be willing to share the draft, however, if you need it immediately. She’s at Loyola U. in Chicago. As always, Jenn does fantastic work.

#asks#alexander the great#alexander the great bibliography#ancient Thebes#Greek Thebes#The Sacred Band#books on Alexander the Great#ancient macedonia#ancient greece#Classics#tagamemnon

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Cardinal, you ve talked a little bit about Crassus tending to open his house to all levels of society and his treatment of his domestic staff and slaves, and I would love to hear more of your thoughts about it?

OH BOY. Okay. So I had to think about this one for two months, because the first attempt to answer this resulted in about ten pages of writing and that’s. arguably too much. I’ve attempted to condense my thoughts down here as much as possible, but. we’ll see how it goes! somehow this is still over a thousand words!

Gonna start this off by tacking this at the top of it.

The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge

To follow that up though, there was no cohesive slave identity shared across the broad scope of people who were slaves in ancient rome, because the lived experiences of each group (agricultural, domestic, freedmen/women, gladiatorial, etc) were so different (for example, freedmen could go on to own slaves themselves, slaves in the mines and working in rural agricultural conditions were the least likely to have a shot at gaining freedom because that would be a loss of income for the roman that owned them, etc) that to associate it all as a uniform identity-experience is also Not Good.

(ibid)

ANYWAY. So my focus on Crassus here has three sides to it.

for the sake of simplicity, we will be using The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge (unless otherwise cited), at the end, I'll tack on some other reading outside of the body of text that I've written.

The most immediate side is that I’m interested in the lives of slaves in the Late Republic, but in a broader scope than the handful of individuals who have historical prominence, you know? Slaves and freedmen occupied a unique social space in the Late Republic, and had a political-social prominence, and I’m curious about which politicians recognized them as a block worth paying attention to. I want to see what they have to say in the absence of a voice.

you can see that the potential social flexibility of the slave was a problem for the Augustan Age/Early Empire by laws that were passed to curtail this, which in turns says something about their role in Late Republic life and society.

So, slaves are an extension of the house they belong to, which is a deeply simplified understanding of all of this so bear with me a little! There’s a social contract, so to speak, that when granted freedom, the (now) freedman has a patron-client relationship with his former owner, who has an obligation to maintain this dynamic.

Freed Slaves and Roman Imperial Culture, Rose MacLean

ALRIGHT. We’re getting to the point where this involves Crassus, hang on.

So Crassus in Plutarch’s bio sounds off that he’s got a lot of slaves, and a lot of mines, but the ones of most value are his slaves in Rome specifically, because they were trained (some personally, by Crassus himself) and skilled in high demand areas, and were sought after. Aside from the obvious, the part that strikes me as interesting is that this is not. an insignificant number. Plutarch says five hundred. That’s a recognizable amount of people in Rome who have a certain amount of social flexibility (the slaves of upper class or political heavy weights had less in common with the urban poor, and frequently interact with other houses of political influence) and all of those people are attached to Crassus.

This would extend even further to any of them who gained their freedom, because that would continue over into a patron-client relationship, and those five hundred slaves mentioned by Plutarch are all in a group that are the most likely to have a chance at buying their freedom. Whether or not this was the case is a huge Who Knows! because Plutarch skips over huge chunks of Crassus' life to get to the political machinations of conspiracy.

Less abstractly and more straightforwardly: Crassus and Clodius were well aware of the political-violence potential of slaves

Roman Freedmen in the Late Republic, Susan Treggiari

This contrasts heavily against, say, Pompey, who has several named slaves/freedmen in his biography that indicate levels of a personal relationship or friendship (we cannot use the mentions of individuals in Pompey's biography to assume that he was inclined to giving his own slaves freedom), and Caesar himself seems to have been even more insular than Pompey in this.

Roman Freedmen in the Late Republic, Susan Treggiari

There’s an underlying thing happening, though, later in Pompey’s life: Pompey (and Caesar) later rival Crassus in terms of wealth, but the difference has to do with location, land distribution, and slaves. Crassus seems to have most of his wealth concentrated in or near Rome (slaves, architecture, renting properties, the fire brigade, etc) with less of a focus on agriculture-mines for an income and more on. this. I'm still going through a couple of books for more on this vague train of thought, but its. something to think about.

Roman Freedmen in the Late Republic, Susan Treggiari

Pompey and Caesar seemed to follow the trend the rest of their military-senatorial contemopraries were following, which. would have inadvertently led to a worsening economic disparity in Rome (the urban poor + displaced farmers being driven off their land and forced to go to Rome for work because the influx of slaves from military conquests was a source of income that slave owners would have hated to give up)

there’s. some kind of additional thought in here about the crucifixion of the six thousand as a display of power and a threat to anyone else who was thinking of revolting against rome. Crassus seemed to have forgone the idea of taking anyone after the battle as a slave and opted for total annihilation, which falls in line with how he could be a ruthless motherfucker when it came to establishing order and did not apparently view this as an economic opportunity.

which moves on to my second thing about Crassus, I think that part of why he had his house open to people across different social classes and wasn’t prone to lavish displays of whatever had to do with how he grew up. I also think that it ties back to Crassus honing in on groups of people and realizing that they had political importance in some way. Plutarch’s bio makes note that he spent time advocating on behalf of anyone who needed it, even on cases that Caesar wouldn’t touch. That is an absolutely KILLER way to build up your reputation in a way where you would not necessarily need to traditionally align yourself with either of the two major political parties, and would lend you a lot of good will with groups of people who are not given voices in historical accounts. An absence of voice does not mean an absence of body!

Which ties into the third thing, Crassus occupies a third space in politics. Crassus specifically appears to drift around without much harm done to his reputation where it counts (Cicero gives him shit for it, but he still managed to get out of several sticky situations mostly unscathed) (Crassus’ appearances in other biographies indicate someone who is not firmly aligned one way or another politically as well, which is fascinating for other reasons).

I think generally, Crassus had his finger to the pulse of the many beating hearts of Rome's groups and understood on some level, the potential power of each one.

Those are my thoughts! also I’m going back in time to the Augustan Age and putting thumbtacks into all of Octavian’s shoes!

ADDITIONAL READING

Freed Slaves and Roman Imperial Culture, Rose MacLean

Roman Freedmen in the Late Republic, Susan Treggiari

The Cambridge World History of Slavery, Volume 1: The Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. Keith Bradley and Paul Cartledge

my point of contention with the last one is that Crassus didn't go on enough military campaigns to rival the other men in this group for it to be an even comparison, especially since he had an opportunity with the Spartacus Revolt and executed six thousand people instead.

#ask tag#long post#good grief is it long#hopefully any of it makes sense. im an artist. i draw comics. the only thing ive taught as an instructor in a classroom was catholic#catechism lmaoo and that was half by accident#book club tag#tris homines

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek horses were smaller (by perhaps some two hands on average than the average cavalry charger early this century), stockier, more cob-like than those we are used to seeing or riding. Stallions were not gelded, which did nothing to assuage their tendency – shared by the mares – to bite. Nor did the rider operate with such seemingly indispensable modern aids to balance and control as stirrups and saddle. The horses for their part went unshod.

The nature of the beast meant that the horse was a hugely expensive commodity; the price most commonly paid for a horse in the fourth century was up to three hundred times the average daily wage of a skilled worker. The expense was especially magnified by a climate and terrain generally lacking in extensive lush pastureland. Only the seriously rich could hope to maintain a horse, let alone a stable or stud, and the horse correspondingly functioned as an obvious status symbol marking out the elite and often aristocratic few.

It followed that even fewer Greeks could afford to own let alone breed racehorses – hence the quite prodigious extravagance implied by Alcibiades’ boasting that he had entered no less than seven teams of four-horse chariots at the Olympics of (probably) 416: this was the ‘blue-riband’ event of the Games (cf. Hiero 11.5), and Alcibiades not only won the first prize but had four of his teams in the first seven finishers. Small wonder that he commissioned Euripides to write a commemorative and celebratory ode, besides exploiting his triumph shamelessly for political purposes. The young Xenophon must surely have been hugely impressed.

Paul Cartledge in the introduction to Xenophon's (possibly?) On Horsemanship.

#ALCIBIADES MENTIONED. god the idea of young xenophon and alcibiades interacting is for some reason stupidly funny. in part because xenophon#was extremely devout. or wanted to be perceived that way#horses#ANYWAY im just sharing this because i want to force myself to read a bit before sleeping at least#and this is a way to motivate myself

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Productivity Check-In: 11/22/23 - 11/26/23

Work:

• Finish Pandora’s Jar by Natalie Haynes

• Read The Wedding in Ancient Athens by John Oakley and Rebecca Sinos

• Start reading Thebes by Paul Cartledge

• Quiz for Age of Pericles

• Submit outline for presentation on marriage in Classical Athens

Thoughts:

• Restful but productive Thanksgiving break!

#productivity challenge#studyblr#history major#study motivation#study blog#studyspo#classics major#classics student#ancient history student#study inspo

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gymnopaidia

The other major Apolline festival at Sparta was the Gymnopaediae, and thereby hangs an interesting etymological tale. Traditionally, the name has been translated as the Festival of Naked Youths, deriving the title from gumnos and paides, but the central action of the festival involved a contest between three age-graded choirs or choruses - Old Men beyond military age, Warriors of military age, and sub-military Youths - and not just action by the Youths alone. So why call the festival after only one of the three principal groups involved?

A more plausible etymology takes gumnos to mean not naked but unarmed, and the paidiai bit to be derived from the Greek word for dancing... So in the Gymnopaediae we are probably dealing with a Festival of Unarmed Dancing, organized as such perhaps in the second quarter of the seventh century.

That would in truth have special cultural as well as cultic meaning and relevance, since the Spartans were famed for dancing in general and for one particular military dance, the Pyrrhic (named in honour of Pyrrhos, or Neoptolemus, son of Achilles). Since all the gods of Sparta, moreover, the female ones as well as the male, were represented visually in their cult statues wearing arms and armour, a festival of unarmed dancing in honour of an armed Apollo would acquire a very particular connotation. This was perhaps the nearest the Spartans got to collectively and communally creating high culture in an Athenian sense. It was to the Gymnopaediae particularly that high-ranking Spartans liked to invite their distinguished foreign friends as guests, treating them to the spectacle of tardy Spartan bachelors being ritually abused for flouting the injunction to marry and procreate.

An early non-Spartan poet likened the Spartans to cicadas, because they were always up for a chorus (both choral dancing and choral singing). The Gymnopaediae, celebrated at the hottest time of the year in the hottest place in Greece for its height above sea-level (about 200 metres), gave a characteristically Spartan calisthenic spin to this joyous theme.

From The Spartans: An Epic History, by Paul Cartledge

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Books recs on Alexander? And also any books to avoid? I've read the Robin Lane Fox biography but that's it.

ooooh I love this question. A lot depends on what kind of stuff you want to read about (military history? sexuality? politics? greater context of the era? history of Macedon in general? biography of Alexander specifically? focus on Hephaestion? Olympias? etc.), but here are some general nonfiction recommendations from my shelves*:

Alexander of Macedon, 356-323 B.C. (Peter Green). If I had to recommend one single book it would be this one; Green’s writing is factual, engaging, entertaining, and well-contextualised. The book is delightfully bitchy at times, and appropriately sober at others. Only real downside is that Green doesn’t much care for Hephaestion, but he doesn’t let that opinion get too intrusive when discussing Alexander’s relationship to him.

Alexander the Great (Robin Lane Fox). You already read this one but it’s a classic so I’m sticking it on the list again anyway.

The Search for Alexander (Ibid.). Similar to his other book, but with the cool benefit of his having re-traced Alexander’s footsteps as closely as possible.

Brill’s Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC - 300 AD (ed. Lane Fox).

The Landmark Arrian: The Campaigns of Alexander (ed. Romm, Strassler). This is by far my favourite edition of Arrian’s writing on Alexander, primarily because of the contextualising information.

The History of Alexander (Quintus Curtius Rufus). There are various English-language translations available; I prefer the Loeb editions.

The Life of Alexander (Plutarch). Again, I like the Loeb translations, but most English-language translations of Plutarch are acceptable.

Alexander the Great (Paul Cartledge).

Alexander the Great (Ulrich Wilcken).

Alexander the Great (Richard Stoneman).

Alexander the Great (Philip Freeman).

Alexander and the East: The Tragedy of Triumph (A.B. Bosworth). Pretty much everything by Bosworth is good in my opinion.

Responses to Oliver Stone’s Alexander (ed. Cartledge, Greenland). Very much a mixed bag, but a lot of really cool historical information about specifics aspects of Alexander’s time that might not be covered in straightforward biographies, e.g. typical fashion of the time period.

The Conquests of Alexander the Great (Waldemar Heckel). Most writing by Heckel is good, and recommended.

Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great’s Empire (Robin Waterfield). Focused more on the aftermath of Alexander’s death, but interesting nonetheless.

The Nature of Alexander (Mary Renault). Some (myself included) would call it outdated, but Renault’s classic biography is just a really enjoyable read regardless. The appendices she adds to her Alexander novel trilogy, especially the first book (Fire from Heaven), are also lovely.

*By this I mean these are all books I own and have read multiple times.

To avoid: Anything by Richard A. Gabriel; anything by E.A. Wallis Budge; anything sensationalising Alexander’s death (e.g. claiming that he was poisoned and this new book explains all about how and who was to blame); most books or articles published before 1975; anything basing itself on the premise that Alexander was an unpopular or generally incompetent ruler (you can pick out these books easily by eschewing anything with a title like “Alexander the Great... FAILURE” or similar — a real work by John Grainger); Alexander the Great: His Life and His Mysterious Death by Anthony Everitt... a book so knowledgeable about Alexander that it uses a bas-relief of Scipio Africanus on the cover instead of one of its purported subject. Yes, that is a real thing that this book does.

Anyway, I hope that helps! I only provided books in English (excluding the Latin/Greek original texts obviously) because you asked in English, but I can also recommend some books in French and German. If any of these books aren’t available in your region, just send me an ask (off anon, please) and I’ll be more than happy to provide you with a PDF or EPUB copy on request.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Cartledge on Commentating on Herodotus: the Cambridge Green and Yellows

youtube

In this final talk from the 2022-2023 edition of the Herodotus Helpline series, Professor Paul Cartledge (Cambridge) examines the five published commentaries on Books 1, 5, 6, 8 and 9 of Herodotus' 'Histories' as part of the Cambridge 'Green and Yellow' series. Professor Cartledge examines the wider context of the series and explores specific themes that tie together the different commentaries, notably the focus on Herodotus' religious interests and the question of literary-historical perspectives.

Source: the youtube channel of Herodotus Helpline

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Cartledge gives the least interesting discussion of Antigone that i've ever heard and then says that Sophocles has been considered "apolitical" and like, i GUESS if you think the only way to be political is literally having your plays be romans à clef about current politics that could be true but Antigone, which he describes about being a conflict between the family (female) and the law (masculine) is more accurately described as conflict between which set of laws to follow, divine or terrestrial, or, more plainly, whether one is bound to follow a a law when by following it you will be allowing injustice to happen. i am mad about this book, thank you.

#he also says that the bacchai is autobiographical because euripides left athens to go live in pella#and of all the people in that play i really do NOT think euripides identifies with Dionysus#(because in his schema euripides = bacchus; athens equals pentheus [i guess]; and agave = fate??? history????)#classics#books & reading

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finished "Some Desperate Glory" by Emily Tesh and god it's like rearranged me emotionally... It's been a while since a book hit so many things I am absolutely obsessed with in just the right way.

CW for non-descript discussion of incest

There is a lot I could say, but I think first and foremost, it's been a very long time since I read a fiction novel about incest that hit as hard as this one does, that really goes into how exactly it is so emotionally and mentally traumatizing, how the grooming process can be so incredibly understated and so life-destroying to realize, how that still doesn't erase the conflicted feelings. There was just a lot being covered by this I wasn't expecting, and usually wouldn't expect in genre fiction tbh.

But that's what this novel is. A long meditation about child abuse and grooming and the slow horror of realization, and the pain of acceptance. And also fascist indoctrination and how that plays into it all!!!!

My only other thought I can put into comprehensible sentences: Kyr/Cleo would have been a WAY more fulfilling romance than Kyr/Lisabel, I'm not even sorry, Lisabel just did not have half the screen-time, character growth or interesting dynamic. Give me the enemiesto lovers.

@cd-container Thank you for rambling excitedly about this book while reading it and convincing me to give it a shot <3

Also I'm putting the author's reading list from the end of the book here, for future reference:

The Anatomy of Fascism by Robert O. Paxton

The Impossible State: North Korea, Past and Future by Victor Cha

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright

The Spartans by Paul Cartledge

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

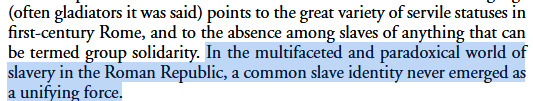

Athens After Empire: A History from Alexander the Great to the Emperor Hadrian

Ian Worthington’s Athens After Empire: A History from Alexander the Great to the Emperor Hadrian shows how there has been a tendency to fixate on the heyday of famous ancient cities while the events before or after have been unfairly and misleadingly eclipsed. Paul Cartledge’s excellent Hellenistic and Roman Sparta (1989) presents how such an approach distorted Sparta’s enduring importance. Now, Worthington's splendid, learned, and highly readable volume will achieve the same for Athens. Worthington's aim is to demonstrate that Athens did not fade away or drop off the historical radar or even decline into oblivion, and he successfully proves his thesis.

Scholars, students, and keen ancient history enthusiasts will all find this book a stimulating illumination of Athens beyond the Classical Age.

The book smoothly combines a chronological narrative with a thematic one, viewing the connection between the cultural context and development of the city against a historical backdrop of frequently turbulent events. Through this approach, Worthington shows just how culturally rich Athens was and how it remained so, even though the democracy of the 5th and early 4th centuries BCE never really returned. This, however, was not the only string to Athens’s bow. Chapters One, Two, Three, and Five deal with the fluctuating situation under Macedonia, with Chapter Four exploring how the changes of power and ruler affected democratic institutions. Chapter Six describes Athens’s brief enjoyment of independence following the death of Antigonus Gonatas. Chapters Seven to Eleven examine the effect of Roman domination on Athens and down to the Battle of Actium, while Chapter Nine is a thematic chapter on change and continuity in Athenian social life and religion. Chapters Twelve and Thirteen look at Athens under multiple Roman emperors until Hadrian. The final two chapters, Fourteen and Fifteen, have a more thematic focus, especially looking at how the city was physically changing under the emperors due to extensive building projects. Worthington employs several different types of evidence - including texts, inscriptions, coins, and architecture - with great skills to give a complete picture. Difficulties in dating specific events or people as well as the gaps in the primary sources are also lucidly addressed.

Continue reading...

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Questions for Philip Pullman 3

What is the origin of the character Giacomo Paradisi, the true bearer of the knife in The Subtle Knife?

Ed Sheeran, musician

In one way he comes from inside my head, because he just turned up when I needed someone to be the bearer of the knife. In another sense, he comes out of a whole tradition of Italian folk tales and Italian storytelling, which includes such things as the commedia dell’arte. I gave him an Italian name because that helped create the atmosphere I wanted.

How do you know when you’ve written something good? How does it feel?

Caitlin Moran, journalist and author

It must be good if it still feels true and parts of it surprising when you read it for the 100th time, I suppose.

Are there any classical myths that you think we should live by today?

Paul Cartledge, ancient historian and former professor of Greek culture at the University of Cambridge

I’m very fond of the story of Prometheus because, in essence, it’s the same as the story I was telling in His Dark Materials, which is itself the same as the story of the third chapter of Genesis: the story of Adam and Eve. It’s about humanity acquiring knowledge and the gods who own the knowledge are very jealous of it and punish those who steal it. I’ve always felt a great resonance in that myth and I think that’s the one I’d pick to live by.

#philip pullman#hdm#his dark materials#giacomo paradisi#the subtle knife#ed sheeran#italian#writing#author#myths#classical mythology#greek mythology#prometheus#genesis#adam and eve#humanity#knowledge#myth

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

As Chilliarch / official second-in-command / right-hand man to the king, what would Hephaistion (or anyone else in that position) have been expected to do? Like if there was an actual “job description” for the role, what historically do you think it would have entailed? From what I can gather, he was essentially expected to:

Field requests to the king or handle them himself otherwise(?)

Oversee internal structural matters, from administration to cultural integration

Curious to know what else would have fallen under his purview.

It also seems to have been a civilian position, i.e., would that mean he'd still have to serve on the battlefield if called for it?

So, this would be a rather complicated, extended answer. Ergo, I’m going to duck this one with a “It’s too long to address as a post." It’s literally part of the book I’m writing. :-D

A couple of quick comments. The Chilliarchy appears to have been based on the Persian office of hazarapatish. Dandamaev and Lukonin address this role in their very important The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. In this, they try to give solid definitions of institutions that were fluid and changed over time, which is my main critique of what is otherwise an EXCELLENT book on Achaeminid Persia. Go Forth and Purchase, if you’re interested.

How Hephaistion modified the hazarapatish role or planned to (he didn’t hold it very long before he died, I suspect), is hard to say. It seems to have been a largely civil-service role that had a limited military aspect. But it changed, morphing over time as necessary.

Below are three articles, including one of mine. Don’t go back to my dissertation; there are some wrong things in that. The article is better, but I’ll still modify some of it. Although the Charles article was published after mine, he doesn’t cite mine, but he’s also not focused entirely on ATG. Listed from most recent to earlier.

Michael Charles, “The Chiliarchs of Achaemenid Persia: Towards a Revised Understanding of the Office,” Phoenix 69 (2015) 279-303. (This one does not appear to be available free.)

Jeanne Reames, “The Cult of Hephaistion,” in, Responses to Oliver Stone's Alexander: Film, History, and Cultural Studies, Paul Cartledge and Fiona Greenland, eds. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 2010. (The second 2/3rds discusses Hephaistion's military and diplomatic role, including the chiliarchy.)

Andrew W. Collins, “The Office of Chiliarch under Alexander and the Successors,” Phoenix 55 (2001): 259–83.

#asks#Chiliarch#Hazarapatish#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Alexander the Great#Achaemenid Persia#Offices of Achaemenid Persia#Classics#articles on the Chiliarchy#ancient Macedonia#Alexander's Empire

6 notes

·

View notes