#phytosaur

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

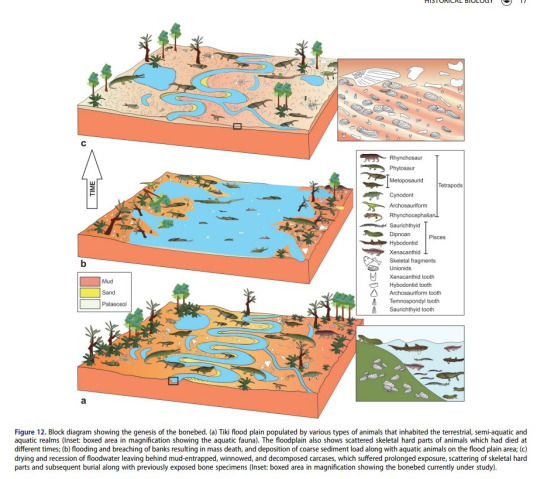

On yesterdays stream we covered the Tiki formation of India, a productive Triassic formation most notable in recent years for it's bonebed of Colossosuchus. This formation was deposited largely during the Carnian, an episode in Earth history known for increased global rainfall.

Subsequently there are lots of flooding events from this period and since we have this from the Tiki formation as well a flooded forest seemed like the best setting for this piece. Also not the baby and juvenile Colossosuchus: the bonebed that preserved them mostly consisted of...

...younger animals so we though if could be cool to show a nursery. Interestingly phytosaurs differ from crocodile in that they have proportionally much shorter snouts as babies. Besides this charismatic megafauna we have a lot of small stuff from here. Based on micro...

fossils the most common animals should actually be small archosaurs, but so far their record isn't good enough to put a name on them. Plants are also known in larger quantities.

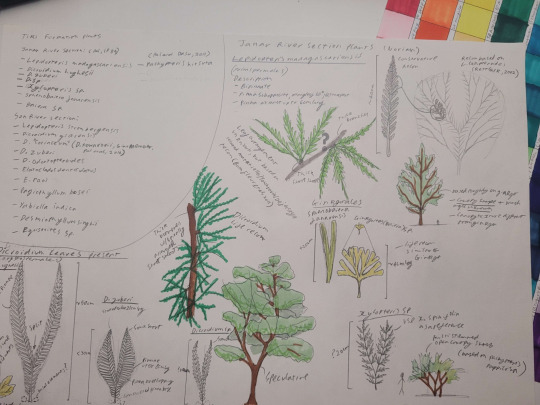

Thankfully Julianne Kiely helped with this and even provided a quick little guide to the flora of this formation.

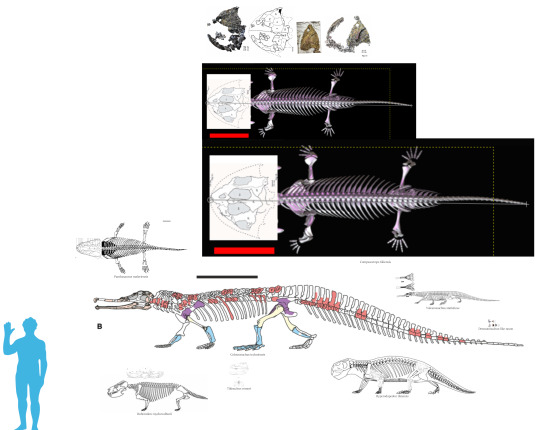

As so often Discord member JW provided the size charts for this stream. take note on the huge temnospondyl from here, a specimen that is now unfortunately lost. Thanks to personal communication with Dr. Sanjukta Chakravorti we were able to get a pretty good estimate.

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

A phytosaur tooth, possibly Redondasaurus sp. from the Redonda Formation in Quay County, New Mexico, United States. There are currently two species described, Redondasaurus gregorii and Redondasaurus bermani. The genus may or may not be synonymous with Machaeroprosopus.

#phytosaur#phytosauria#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#redondasaurus#machaeroprosopus#parasuchidae#triassic#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#レドンダサウルス#マケロプロソプス#パラスクス科#植竜類#化石#古生物学

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

March Madness: Bracket 7

And we're back with another day of march madness. Today's competitors are a couple of very large archosaurs.

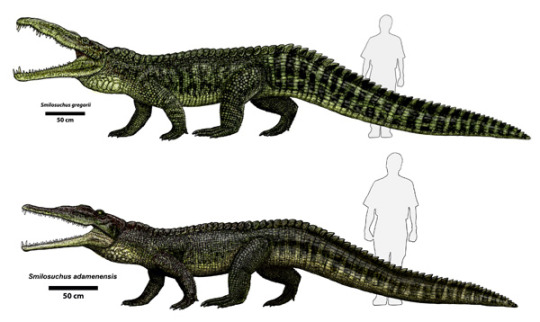

Smilosuchus gregorii is a very large phytosaur measuring upto 23 ft long.

Purussaurus is the largest known caiman measuring between 25 and 30 ft in length.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

hello, paleonerds!

as some of you know, i work for the st. george dinosaur discovery site museum. the museum is really struggling with finances after a slow summer, so we're hosting a fundraiser in the form of an art contest to help raise money.

the subject of the contest is phytosaurs, since we finally just received our phytosaur skull replica. the entry fee is $2 per entry, via a donation to the museum (linked on the form). the three winners will be printed and displayed within the museum!!

here is the link to the contest form

#museumblr#paleoblr#paleontology#paleo#dinosaurs#phytosaurs#museum#phytosaur#art contest#please boost#paleo meme

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Croctober first day:

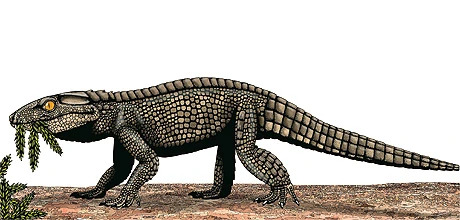

Colossosuchus

Using prompt by @/arminreindl :

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rutiodon, a Late Triassic phytosaur, basking in the sunlight of a late summer afternoon. A hypuronector, icarosaurus and other reptiles scurry and fly among the bushes.

Lockatong fm., Triassic

#drawing#art#paleoart#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#triassic#fossils#phytosaur#paleontology#watercolor#palaeontology#watercolour#dinosaur#palaeoart

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triassic Double Feature

Just weeks ago I remissed the lack of new croc taxa, seems I spoke to soon because they are being pumped out like crazy right now. For simplicity, I will cover two of the recent sorta-crocs together as neither are super extensive and they match in overall time.

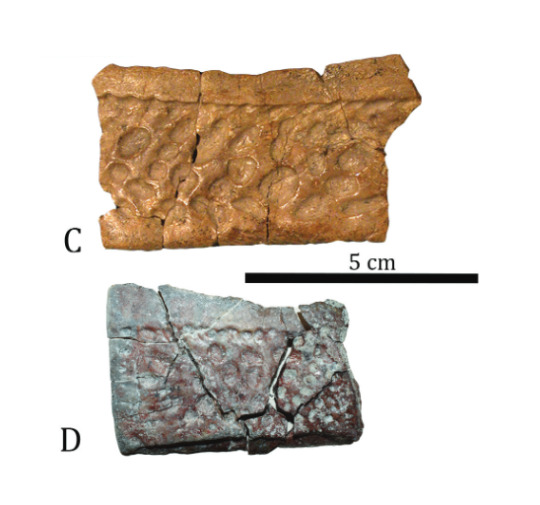

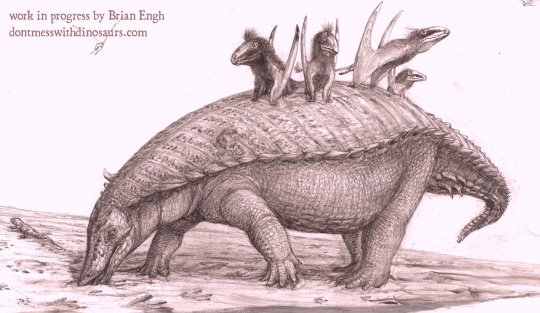

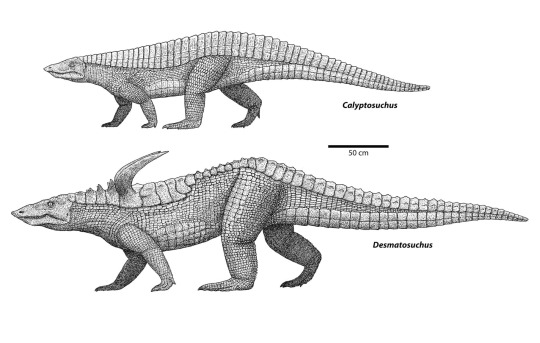

These two new genera are the aetosaur Kryphioparma and the phytosaur Jupijkam. Pictured below the fossils of both with reconstructions of close relatives (art by Brian Engh and Gabriel Ugueto).

I'll start with Kryphioparma, which I wager is the less interesting of the two. Kryphioparma was an aetosaur, which are effectively early pseudosuchians that evolved a body type very similar to what nodosaurs did later. Heavily armored, sometimes with prominent spikes and herbivorous.

Kryphioparma is only known from four isolated and incomplete osteoderms, and though these are actually diagnostic and highly distinct, it does mean there's not super much to say. Hell, the scientific name literally means "mysterious shield" in reference to how little we know.

Regardless, scientists did determine two things. 1) It's a typothoracine aetosaur, narrowing down its placement to one of the two main branches. This means its closer related to Typothorax (with its armored cloaca) than to Desmatosuchus (with its shoulder spikes). 2) The second thing we know is that it wasn't alone. No, the localities that yielded its bones (Placerias Quarry and Thunderstorm Ridge) actually preserve a highly diverse aetosaur fauna, including Calypsosuchus, Tecovasuchus and two species of Desmatosuchus. All images by Jeff Martz.

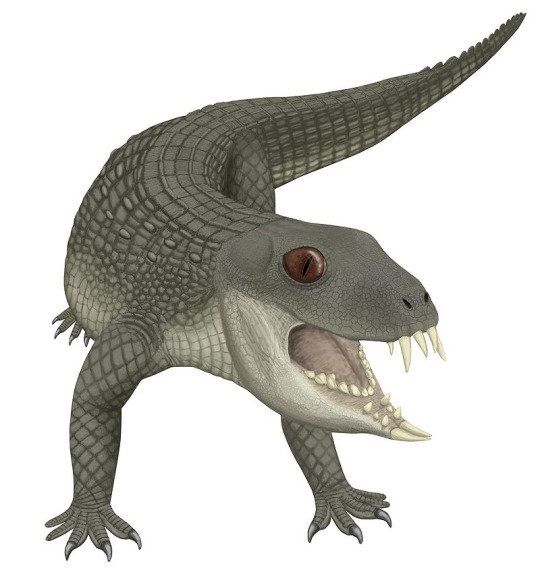

Now the arguably more exciting find is that of Jupijkam, a type of phytosaur, which are archosaurs superficially resembling today's crocodiles. Now when I grew up, phytosaurs used to be considered to be entirely unrelated to crocs, being a type of archosaur believed to have diverged prior to the bird-croc split. However, it would appear that recent studies suggest that they could actually be true croc-line archosaurs, potentially being the earliest diverging group of Pseudosuchian.

Jupijkam is from the Rhaetian-Norian Blomidon Formation of Novia Scotia, Canada. This not only makes it one of the youngest, but also one of the northern-most known phytosaurs to date. It's scientific name, Jupijkam, is actually derived from the name given by the local Mi’kmaq people to their version of the horned serpent.

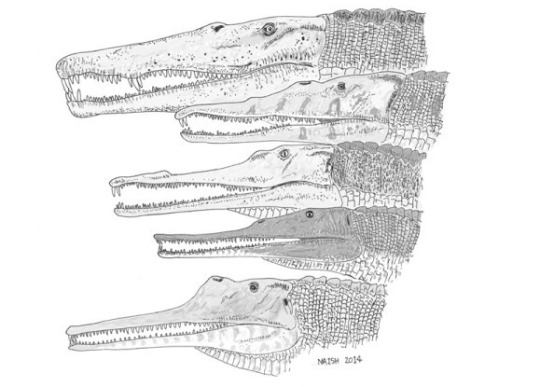

How Jupijkam is related to other phytosaurs is a bit wonky. Now generally, its recovered as a mystriosuchine, which isn't exactly a surprise given that most phytosaurs fall into this category. It's placement however shifts ever so slightly depending on the precise methods and characters used. 2/4 times it was found to be most closely related to Rutiodon (the phytosaur shown at the very start), once alongside the Indian Volcanosuchus and once to its exclusion. One tree simply results in a big polytomy which isn't really helpful, and one time it was found as a much more derived form related to Mystriosuchus. Whatever the case, additional finds both of other phytosaurs and Jupijkam specifically might clarify this in the future. Currently however, it seems that this form is not related to all the other American species of its time, suggesting it held out till the late Triassic independently. Which is pretty neat. Below you can see a comparisson between Jupijkam and some other slender-snouted phytosaurs, courtesy of Brownstein 2023. A is Jupijkam, B is Rutiodon and C is Machaeroprosopus

Really that wraps things up already, two new genera, both Triassic, both (potentially) early Pseudosuchians. A little bit out of my usual focus but very interesting none the less. Definitely gotta make another post soon since they just dropped yet another new one (a metriorhynchid), but I gotta read that paper first. Speaking of which A new aetosaur (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the upper Blue Mesa Member (Adamanian: Early–Mid Norian) of the Late Triassic Chinle Formation, northern Arizona, USA, and a review of the paratypothoracin Tecovasuchus across the southwestern USA (escholarship.org) A late-surviving phytosaur from the northern Atlantic rift reveals climate constraints on Triassic reptile biogeography | BMC Ecology and Evolution | Full Text (biomedcentral.com) plus the respective Wikipedia pages Kryphioparma - Wikipedia Jupijkam - Wikipedia

#pseudosuchia#phytosaur#aetosaur#croc#palaeoblr#paleontology#prehistory#triassic#chinle formation#Kryphioparma#Jupijkam#long post#science#reptiles

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

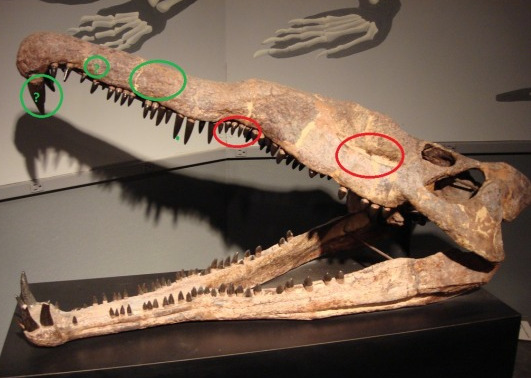

Did phytosaurs have lips?

Mystriosuchus planirostris by @paleoart, the inspiration for this post.

2016 was many things, but one of the best was definitely being the call out year for many archaic paleoartist mistakes. One of these was the absence of lips in many reconstructions, from the skin-wrapped maws of theropod dinosaurs to the bare-toothed saber-toothed cats to the rather ridiculous depictions of entelodonts and other prehistoric mammals as fanged demons. This year saw the publication of various papers showing that teeth do generally in fact need lips to be protected from damage and moistened, meaning that many animals traditionally reconstructed as bared-toothed monsters need a healthy amount of oral tissue.

That said, things aren’t black and white. Crocodilians, after all, still have bare teeth. In one of these papers, Larson et al 2016, it’s been suggested that their aquatic habits compensate for their lack of lips, as humidity certainly isn’t a problem. However, as the Mark Witton link above informs you, many crocodiles go through prolonged periods of life on land without tooth degradation. It also doesn’t cover how terrestrial crocodylomorphs would have coped with the absence of lips, or why many aquatic vertebrates like dolphins (Platanista aside) still kept their lips.

It seems, therefore, that crocodiles are simply off in this regard. Their liplessness actually appears to derived from a highly unusual facial development process, which essentially renders their entire face a single “scale”. This seems to have evolved in order to develop the extensive Integrumentary Sense Organs (ISOs), thinning the facial skin in order to increase sensivity, and it carried over into their terrestrial descendants.

This obviously raises the question of whereas groups similar ecologically and morphologically to aquatic crocodilians underwent a similar process. Where they also lipless, or did they in fact retain their lips, making comparisons to crocodiles all the more questionable?

The Phytosaurs

Phytosaur head diversity by Darren Naish. Taxa included: Smilosuchus gregorii, Pravusuchus hortus, Mystriosuchus westphali, Paleorhinus bransoni and Pseudopalatus pristinus.

Phytosaurs were, in some respects, the “original crocodiles”, having evolved and prospered long before crocodylomorphs ever touched the water. Although they weren’t particularly closely related (birds are closer to crocodiles than phytosaurs are), these archosauriform reptiles did hit most of the same notes as crocodiles: barrel-shaped bodies, extensive osteoderm armours (in some cases even better protected, due to the bell-shaped cap on the throat and various scutes on the forelimbs and belly), generally short limbs and large, paddle-like tails.

While some phytosaurs explored odd ecological niches – Nicrosaurus and similar taxa are adapted to a primarily terrestrial lifestyle, while Mystriosuchus was inversely so specialised to life in the water that it was practically the Triassic Metriorhynchus -, a generally semi-aquatic lifestyle for most phytosaurs can be inferred due to due sheer prevalence in freshwater and shallow marine deposits, limb proportions and shape, laterally flattened and powerful tails and retracted nostrils (though keep reading).

Various tracts attributed to these animals similarly imply a close functional match between phytosaurs and crocodiles. Various swimming tracts have been attributed to phytosaurs, while the Apatopus footprints show an interesting insight on these animals’ terrestrial locomotion capacities, being capable of an erect gait like archosaurs and mammals, including modern crocodiles and alligators. Paleopathology studies indicate similar behaviours such as interspecific biting (hence the need for strong armour), and perhaps more damningly endocast studies show that the general phytosaur brain shape was rather similar to that of modern crocodilians (albeit with a few differences, like the size of the brain and the presence of multiple sinuses; see below).

For all intents and purposes, phytosaurs were functionally crocodilian, offering one of the most extreme cases of convergent evolution ever recorded. But no matter how close, phytosaurs were still off the mark in various ways.

Phytosaur facial anatomy and morphology

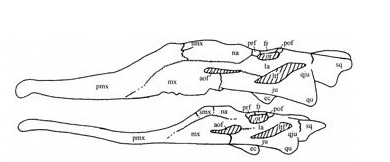

Pseudopalatus buceros skulls, exemplifying the general morphology of phytosaur skulls as well as interspecific variation. Notice massive premaxila.

The most classical thing you’ve ever heard about phytosaurs was how they differ from crocodiles in having the nostrils be close to the eyes/on top of the head rather than at the tip of the snout. This is true; as you can see, the nostrils are located in front or above the eyes in a “volcano-like” elevation; combined with the nostril-less and often conical snouts, this gives them a distinctive dolphin-like profile.

Like in cetaceans, this nostril placement would come in handy on a mostly aquatic lifestyle, avoiding drag and allowing the animal to surface only a small part of the head and remain concealed underwater. However, unlike cetaceans – and marine reptiles such as plesiosaurs -, this nostril position is not derived from nasal retraction. In fact, phytosaur nostrils are sometimes noted as being rather protracted, sometimes as a result of the general elevation of the nasal region.

Instead, what happened is that phytosaurs elongated the premaxila at the expense of the other skull bones. Unlike crocodiles – and whales and plesiosaurs and many other aquatic tetrapods -, half or more of the phytosaur upper jaw is composed of a single bone, normally a vestige at the end of the jaw in most amniotes, that expanded radically. This hints at a pretty rapid elongation of the snout, explaining maybe why long-snouted phytosaurs appear “out of nowhere” in the fossil reccord.

Predictably, this could also hint at rather atypical development, which is etremely important in dictating the presence or absence of lips.

Another frequently cited difference is the presence of antorbital fenestrae. These are the famous “holes” in front of the eyes present in most dinosaurs and other archosauriform reptiles. Crocodiles have lost them, but they are present in phytosaurs, though they can be reduced in some species. Perhaps associated with this, phytosaurs also have extensive antorbital sinuses, while crocodilians lack them altogether. Phytosaurs also have an extensive premaxillary sinus, though as crocodilians have most of their snout taken by the nasal airways this may not make a lot of difference.

With a few exceptions, most aquatic crocodilians have conical teeth; they compensate for the lack of meat-cutting speciations with the infamous “death-rolls”. Phytosaurs, by contrast, generally have serrated teeth, and combined with the presence of crests on many specimens it seems unlikely that these animals engaged in “death-rolls”, instead opting for more typical meat-eating behaviours. To date longirostrine phytosaurs are the only “gharial-like” vertebrates with serrated teeth, and it might explain why they were frequently associated with the carcasses of terrestrial vertebrates like rhynchocephalians and dinosaurs.

Unlike the teeth of crocodiles, phytosaur teeth seem to be rarely interlocked. Even without lips, it seems likely that the upper jaw teeth covered the lower jaw ones.

What about the lips?

Leptosuchus skull, illustrating the basic points for and against phytosaur lips. For are in red: anteorbital fenestra and serrated teeth. Against are in green: long prexmaxila, POSSIBLE ISOs, front teeth POSSIBLY too large to fit within lips. The latter two are of course ambiguous.

With the above in mind, the absence for or against phytosaurian lips is…mixed.

The rapid premaxilary development in phytosaurs is the key to understanding how the jaw integument of these animals worked. It is possible that the premaxila’s growth prevented the formation of conventional lips, either due to physical and metabolic constraints or because the same genes triggering it could have prevented the development of lips. Perhaps the same pressures causing the crocodilian “single scale” would have been forced on phytosaurs by this developmental quirk.

On the other hand, other parts of the phytosaur skull anatomy seem to suggest the presence of lips:

The aforementioned antorbital fenestrae suggests that the phytosaur skull was less “skin-tight” than that of crocodilians. In modern birds, the only living reptiles with antorbital fenestrae, that area of the skull is covered by various soft tissues, and indeed areas of the avian beak devoid of a rhamphotheca tend to be covered by fleshy lips.

Serrated teeth tend to be more vulnerable than conical teeth to degradation, so most predatory animals that possess them have them covered by lips. The only crocodilians with clearly serrated teeth are terrestrial species and the fairly basal thalattosuchians, which are still on the limbo on whereas they had lips or not.

It is possible that phytosaurs found themselves in an unique integumental arrangement. Perhaps they did become lipless, with a “single scale” covering the jaws, while the rest of the head had a more normal integument.

A deciding factor in this argument would be the discovery of ISOs on phytosaur jaws. However, structures associated with these organs, such as pits, are rarely discussed outside of the context of pathology when it comes to these animals. There is plenty of literature on pits and holes in phytosaur skulls being caused by fights and bites, but few on any possible natural ones.

Conclusion

Modern Ganges River Dolphin. Although it has exposed teeth, it’s also not the norm among cetaceans.

Just because something resembles another doesn’t mean that there is an exact equivalency. Case in point: no matter how close phytosaurs got to crocodilians, they still differed in many aspects, and could not be mistaken for them in life.

It’s clear that skin-wrapping is a tremendous lack of appreciation for the organic nature of extinct animals. The lack of lips in crocodilians has been taken far too long to be the “norm”; but, as it turns out, it is an anomaly among the usual amniote tendencies.

We may never know for sure whereas phytosaurs had lips or not. Hell, it’s even possible that some had while others went full Platanista. However, far too often are they taken to be crocodile-like for granted, without other possibilities, equally as valid as they are, taking into consideration.

Hopefully, further research will grant us insights on how these already spectacular animals looked in life.

References:

Reisz, R. R. & Larson, D. (2016) Dental anatomy and skull length to tooth size rations support the hypothesis that theropod dinosaurs had lips. 2016 Canadian Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Conference Abstracts, 64-65.

Grigg, G., & Kirshner, D. (2015). Biology and evolution of crocodylians. Csiro Publishing.

Soares, D. (2002). Neurology: an ancient sensory organ in crocodilians. Nature, 417(6886), 241-242.

Stocker, M. R. & Butler, R. J. 2013. Phytosauria. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 379, 91-117.

Kimmig, J. 2013. Possible secondarily terrestrial lifestyle in the European phytosaur Nicrosaurus kapfii (Late Triassic, Norian): a preliminary study. Bulletin of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science 61, 306-312.

Gozzi, E. & Renesto, S.A. 2003. Complete specimen of Mystriosuchus (Reptilia, Phytosauria) from the Norian (Late Triassic) of Lombardy (Northern Italy). Rivista Italiana Di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 109(3): 475-498.

Michelle R. Stoker; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Li-Jun Zhao; Xiao-Chun Wu; Chun Li (2016). “Mosaic evolution in Phytosauria: the origin of long-snouted morphologies based on a complete skeleton of a phytosaur from the Middle Triassic of China”. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 76th Annual Meeting Program & Abstracts: 232.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A late-surviving phytosaur from the northern Atlantic rift reveals climate constraints on Triassic reptile biogeography

Published 17th July 2023

Description of a new phytosaur, Jupijkam paleofluvialis, from the Late Triassic of Nova Scotia in Canada.

Partial skull from Jupijkam paleofluvialis holotype

Jupijkam paleofluvialis rostrum

comparative Illustration of Jupijkam paleofluvialis(a), Rutiodon carolinensis(b) and Machaeroprosopus lottorum(c) skulls

Source:

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phytosaur vertebrae and leg bone. Late Triassic. Chinle Formation, Shinarump member.

0 notes

Text

Results from the #paleostream Guidraco, Indohyus, Grandemarinus, Machaeroprosopus.

463 notes

·

View notes

Text

A phytosaur tooth, possibly Redondasaurus sp. from the Redonda Formation in Quay County, New Mexico, United States. There are currently two species described, Redondasaurus gregorii and Redondasaurus bermani. The genus may or may not be synonymous with Machaeroprosopus. The crown is quite nice and serrated with part of the root still remaining.

#phytosaur#phytosauria#fossils#paleontology#palaeontology#paleo#palaeo#redondasaurus#machaeroprosopus#parasuchidae#triassic#mesozoic#prehistoric#science#paleoblr#レドンダサウルス#マケロプロソプス#パラスクス科#植竜類#化石#古生物学

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

new spino paper hath arrived

and its not by ibrahim OR sereno!!!! another player has thrown their hat into the ring!

236 notes

·

View notes

Text

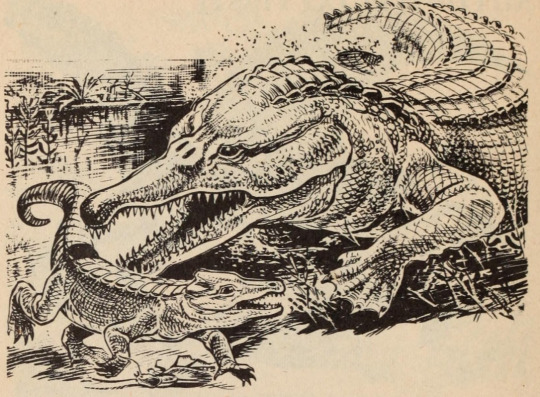

Phytosaurus and Protosuchus. Animal Ghosts. Edited by Claudia Clow. Illustrated by Walt Disney Productions. 1971.

Internet Archive

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

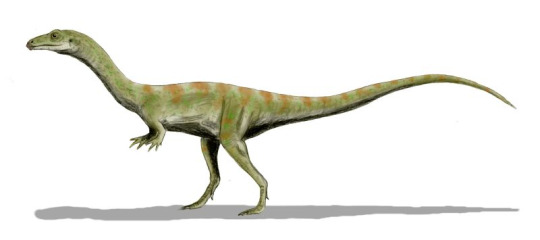

And now for a completely unrelated animal that has absolutely nothing to do with crocodiles...

Yes, the body plan is just that good.

Why crocodile-line archosaurs are cooler than you think

Pseudosuchian evolution is like really, really underrated. Like people learn a version of "crocodiles have been around for 200 million years" even though pseudosuchians have a super interesting and diverse history. Some forms even converged on the "primitive dinosaur" body plan, despite not being dinosaurs at all!

In rough order of divergence:

Desmatosuchus, an aetosaur

Arizonasaurus, a poposauroid

Shuvosaurus, another poposauroid (not a dinosaur!)

Postosuchus, a rauisuchid

Terrestrisuchus, an early crocodylomorph

Neptunidraco, a thalattosuchian

Baurusuchus, a sebecosuchian

Chimaerasuchus, a notosuchian

Simosuchus, another notosuchian

Anatosuchus, a crocoduck notosuchian

Yacarerani, yet another notosuchian

While bird-line archosaurs are fluffier, and have been much more widespread since the Jurassic, pseudosuchians displayed a much wider range of adaptations than we gave them credit for - from fully aquatic thalattosuchians to small terrestrial, herbivorous, armored notosuchians!

243 notes

·

View notes