#quds news network is not reliable

Text

I hope people realise that QUDS news network is run by Hamas. It is not reputable and it shouldn’t be used as a reliable source of information.

#quds news network#quds news network is not reliable#israel#i stand with israel#jumblr#palestinian hypocrisy#hamas is isis#palestine

148 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Palestine Resources!

BDS Official Boycott List:

How to Write Your Reps About a Ceasefire:

Source: genicecream

If you live in the USA:

text CEASEFIRE @ 51905 to call for a ceasefire | text RESIST @ 50409 to send a letter to your representatives to pass HR3103–a bill that prohibits tax dollars from going to israel | download 5Calls app to contact members of your congress

How to Send e-sims:

-download the app Simly https://simly.io

-search for Palestine

-buy one of the options

-screenshot the QR code

-send the screenshot to [email protected]

source: sofidilla

Follow Reliable Resources for News:

MoTaz | Bisan | Al Jazeera | Quds News Network | Muhammad Smiry | Ghassan Abu Sitta | Mohammed El-Kurd | Hind Khoudary

Donate:

Care for Gaza | Palestine Children's Relief Fund | Medical Aid

Other Things You Can Do:

Palestinian Literature | Palestinian Recipes | Find an Upcoming Protest | Buy a Kufiya

this is far from a comprehensive list (ones like this are much more put together), but i thought it was important to be able to share these resources and spread what i can, especially with this platform. make sure you're always being aware of news and reblogging and retweeting, even spreading news is such an impact!

156 notes

·

View notes

Note

i thought al-jazeera was a reliable news source, outside of tumblr blogs now is there any other reliable way to be updated?

Al-Jazeera is still relatively reliable for most news out of Gaza, despite the recent misattribution. Other decent outlets include Al-Mayadeen, Al-Alamy, Al-Araby, Al-Quds, Resistance News Network (although some people will object to this one), Middle East Eye, and Middle East Monitor (the latter two focus more on analysis than breaking news, but not always). No news outlet is perfect and all of them have their issues, but we have to make do with what we have.

Further suggestions from our followers that I may be forgetting or not aware of are welcome.

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social media has been flooded with graphic footage and images showing casualties and destruction since Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October.

Such content emerges from all modern conflicts. However, this one has also seen a slew of demonstrably fake or mis-contextualised content being produced at a scale that has shocked even long-time observers of such conflicts.

"This is a new level," compared to other wars - including the one in Ukraine - says Dina Sadek, Middle East research fellow at the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab.

"We have been seeing misinformation, disinformation, and unverified and misleading content of everything under the sun," she added.

So, what is so different this time? Who is contributing to the problem, and what are their strategies and motivations?

General users amplifying false claims

"I think that's amplified the amount of people that are sharing misinformation and disinformation, perhaps unknowingly, online," said Charley Maher, social media editor from Bellingcat, an investigative website specialising in online research and image analysis.

Ms Maher said that unlike other conflicts there is a perceived need among people in many countries to publicly state a position about what is happening in the region.

The content many of those people are sharing often comes from media companies in the region, or with interests in the outcome of the conflict.

While much of the media content coming from Israeli and Arab outlets, and outlets in the wider Middle East, is accurate, some of it has been shown to be heavily skewed or incorrect.

Media Misinformation

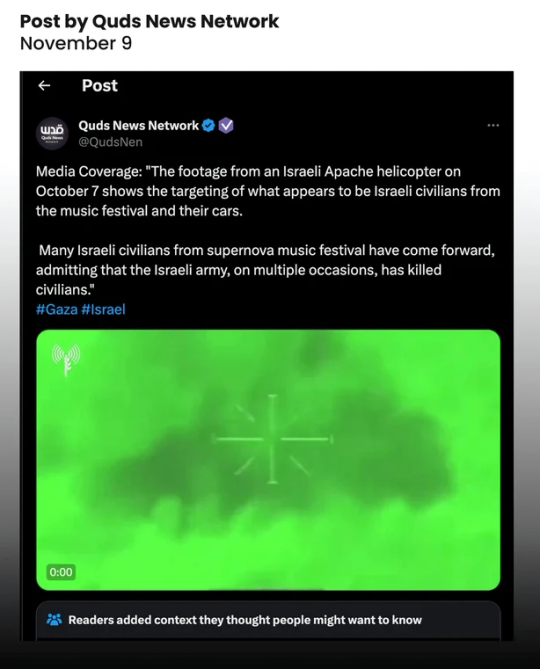

The prominent Palestinian news agency Quds News Network, among others, has shared misleading footage and amplified false narratives.

Quds News Network reports extensively from Gaza and has been considered by the Palestinian Authority and US State Department to be affiliated with Hamas and the other Gaza-based armed group, Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

It is independently owned and has a strong social media presence in both Arabic and English. As a result, its footage of attacks and destruction in Gaza is consistently shared widely online.

However, those online posts are not always reliable.

In one instance on 9 November, Quds cited "media coverage" to amplify false claims circulated on social media purporting to show a video from an Israeli Apache helicopter firing on people attending the SuperNova music festival.

More than 350 people were killed at the festival during the Hamas attacks of 7 October, out of a total of over 1,200 people killed across southern Israel.

In response to the Hamas attacks, the Israeli military launched a massive air campaign that it said targeted Hamas-linked locations in Gaza.

Two days later, on 9 October, the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) posted footage taken from planes and helicopters of the airborne operations. The footage that Quds later described as being of the Israeli military attacking the music festival was included within that IDF footage.

However, when Quds News Network reposted the video it incorrectly claimed it showed evidence that Israeli helicopters had shot at festival-goers.

That claim was analysed and debunked, including by researchers for the group GeoConfirmed and the BBC. They concluded it had been taken in an area nearer the Israeli-Gaza border, inside Gaza, not at the location of the festival.

Furthermore, the footage in the video published by the Israeli military was infrared, indicating it was recorded in the dark, while the attack on the festival began around 7am, well after dawn.

Other high-profile pro-Palestinian accounts amplified to the same claim about the footage. It was also posted on 19 November by Iranian state-affiliated news platform Tasnim News Agency.

The tweet posted by Quds has not been deleted or removed by X (formerly Twitter), and has been seen more than 550,000 times, and reposted almost 4,000 times.

It is just one of many examples of media misinformation since 7 October.

In this instance, researchers say the false claims may have been part of an attempt by Hamas, or elements sympathetic to them, to push back against criticism for killing civilians.

"That helicopter footage was being used to [say] that Hamas did not actually kill the rave concert goers, that it was the Israeli government. And that has been taken out of context," according to Moustafa Ayad, Executive Director of the Africa, the Middle East and Asia programme at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD).

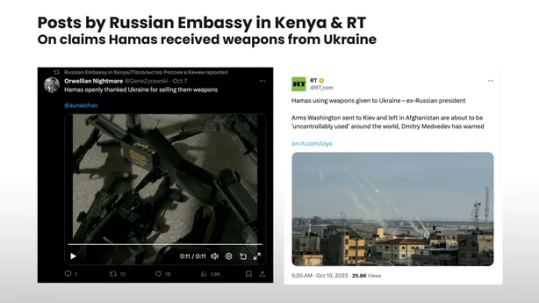

Russian social accounts have also been promoting claims relating to the Israel-Hamas conflict.

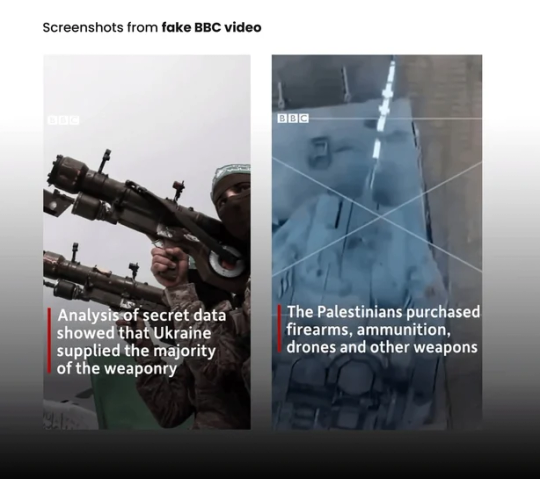

One heavily promoted claim was that Ukraine had provided weapons to Hamas. It was circulated on social media by Russian Telegram accounts through the production of a fake BBC News video report.

The content of the video claimed that the investigative website Bellingcat had obtained secret data containing evidence that Ukraine had sold arms to Hamas. The video was branded with the BBC logo and the text on screen was in the font and design style used in all online BBC videos.

"It's unclear if this is a Russian government disinformation campaign or a grassroots effort, but it's 100% fake," Eliot Higgins, the founder of Bellingcat, tweeted.

A professor briefly featured in the video told Reuters that claims attributed to him in it were "entirely fake. Never said that".

Russian state-controlled media accounts, diplomatic accounts, and politicians on X, had pushed the same narrative since around 7 October.

The Russian Embassy in Kenya shared a post from a user 'Orwellian Nightmare', which said "Hamas openly thanked Ukraine for selling them weapons".

The post included an 11-second video of unknown origin showing weapons, with the voice of someone heard in the background speaking Arabic.

The same claims reached, or were pushed by, senior Russian politicians and state-funded media.

On Telegram, Dmitry Medvedev, former Russian president, and current deputy chairman of the Security Council of Russia, also claimed weapons provided to Ukraine were being used by Hamas.

State-funded TV channel RT subsequently reported on Mr Medvedev’s "warning".

Officials Sources

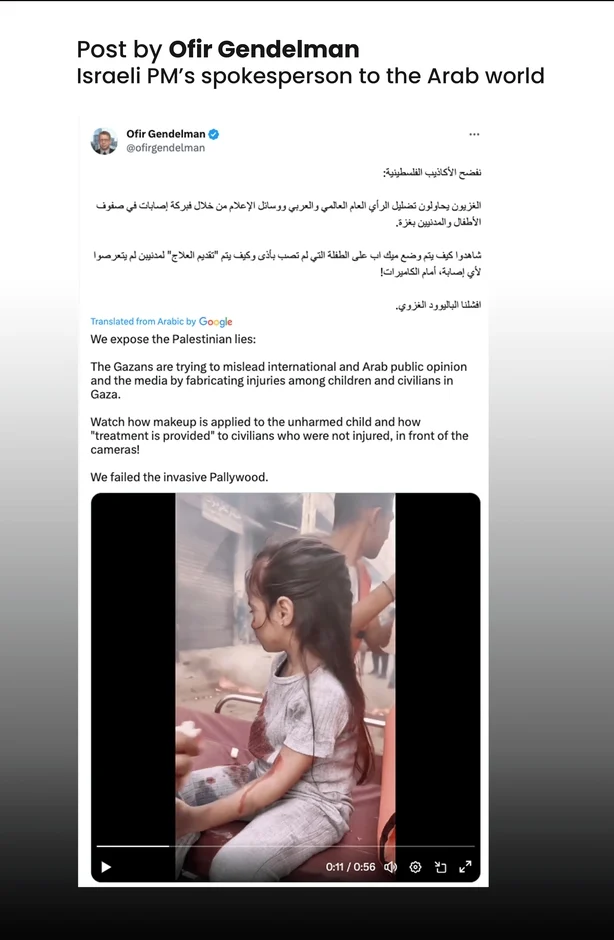

Disinformation and misinformation are also being produced and amplified by officials and spokespeople involved in the conflict.

The Israeli Prime Minister's Arabic language spokesperson shared footage that he claimed was evidence Palestinians regularly fake injuries to blame Israel for civilian casualties caused by air strikes.

In one such case, the spokesperson, Ofir Gendelman, posted a video showing a young girl with blood on her face on a gurney with emergency workers.

"Watch how makeup is applied to the unharmed child and how 'treatment is provided' to civilians who were not injured, in front of the cameras," he tweeted in Arabic.

He then makes reference, as he has done so at numerous time over recent years, to "Pallywood".

Pallywood is a term used by accounts and people who say Palestinians are creating fake ‘Hollywood’ scenes and trying to pass them off as news footage.

In fact, the footage was not being distributed as news footage, it was taken a short Lebanese film about the suffering of Palestinians called 'The Reality'.

The source video was posted on the film director's Instagram account on 28 October. In a later video posted on 9 November, the director said it had been taken out of context by some trying to add to the Pallywood narrative.

Referring to other scenes in the original film, he asked why there would be balloons, confetti, and musical instruments in "staged war content".

"The Pallywood discourse, which has been promoted by the State of Israel's official X accounts are still getting a lot of traction," Mr Ayad of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue said.

"At one point, I think we had clocked something like there were 450,000-plus references to Pallywood and there were 350,000 unique accounts that were referencing the Pallywood sort of trope in and of itself," Mr Ayad said.

References to 'Pallywood’ are not new, and tend to peak online during times of increased Israeli-Palestinian tension, according to Ms Sadek of Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab.

"That was the case back during 2021 crisis, and again before that in 2014, and before that in 2009 and 2006."

"It is essentially saying that Palestinians are faking deaths," said Mr Ayad. "And on top of it, it's being layered with what you could say is just like mockery of civilian casualties."

Misleading or false narratives shared by official accounts not only dilute the online conversation but can have more serious consequences, says Ms Maher from Bellingcat.

"I think it can be highly problematic because it can sway political responses, which obviously have a direct impact on the conflict itself."

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Quds News Network is a Hamas-affiliated news site. In this case it translated the words of Ben Gvir incorrectly - he threatened terrorists, not Palestinians. Haaretz quoted him as saying, “Our government killed the most terrorists, over 120 in the past six months, but a lot of work remains – and we have to lend a helping hand to soldiers and the police to support and strengthen them.”

But an Arab or Hamas media outlet lying about what an Israeli said is hardly news. Far more interesting is that this is where a UN representative gets her news from.

Quds News is an unabashedly pro-terrror site, like most Palestinian media. But it is also explicitly antisemitic.

One article denies that Jews are a people, quoting the Khazar myth and others.

This Quds News article about the Holocaust says that Jews believe "the suffering of the Jews cannot be compared to the suffering of the rest of the peoples, since the Jews are the people chosen by the Lord El, while the rest of humanity becomes in an inferior stage of this choice, - being gentiles - and therefore the suffering of the Jews - the supreme race of all - is not similar to the suffering of inferior Gentiles." In this quote, Quds News is echoing the justifications of the Nazis for genocide.

It then says that Palestinians are the primary victims of the Holocaust, not Jews.

This is all classic antisemitism. It is hate that the news site is quite proud of and not at all ashamed of. So it is no surprise that Francesca Albanese considers an antisemitic, Hamas news site to be a reliable source for her to quote.

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey so which part of the healing process is breaking into cemeteries and digging up corpses to steal?

https://twitter.com/QudsNen/status/1747524513342898451?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

rather confusing message you are sending here

Oh boy, it's a Twitter post from Quds News, the most reliable and dependable source you can find. Oh, wait...

It's a worthless rag, a literal propaganda outlet for Hamas and the PIJ, caught lying numerous times. Well isn't that just too bad.

But, since you seem so broken up about the desecration of the dead, do check out what Hamas has done to the bodies of those they murdered on 7/10 and beyond. And get off anon while you're at it, you worthless coward.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Iran out of 2015 Nuclear deal

Iran says it will no longer abide by restrictions on its nuclear program. Those limits were the center piece of the 2015 Iranian nuclear deal designed to hamper Tehran’s efforts to build an atomic bomb. Under the deal Iran was limited to operating around 5000 basic centrifuges enriching uranium to 3.7 percent and stockpiling no more than 202.8 kilograms. In reality, Tehran was openly violating those restrictions for years through incremental breaches. Back in May 2019 Iran announced it would step up its uranium enrichment levels to 4.5 percent -- still well below the 90 percent weapons grade needed to make a nuclear bomb – but clearly a step in that direction. A few months later Tehran confirmed it had also exceeded its uranium stockpile limits and had brought on line new trains of high capacity, more advanced centrifuges – with even more sophisticated versions on their way. So, breaking the 2015 nuclear deal is in line with these developments. It means Iran no longer honours restrictions on how much uranium it enriches or whether that uranium is enriched to weapons grade. Tehran’s also been breaching its agreements by continuing to develop ballistic missiles for use as a nuclear weapons delivery system -- under the guise of a so-called space program. Iran currently has over two thousand ballistic missiles. United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency says that during the early 2000s the Islamic republic explored various fusing, arming and firing systems to make its missiles more capable of reliably delivering a thermonuclear warhead. In May 2018 the full extent of Iran’s secret nuclear facilities were exposed by Israeli Mossad agents who released a treasure-trove of some 55,000 documents obtained from Iran’s secret nuclear archive -- outlining Tehran’s clandestine Project Amad nuclear weapons program. The islamic republic’s true nuclear ambitions were really never in doubt. Tehran’s claims to the world that its nuclear program was for peaceful power generation only – were always considered deceitful and dishonest – never supported by the available evidence. Iran currently has less than half of the 1,050 kilograms of enriched uranium needed to construct a single nuclear weapon. However, the United Nations International Atomic Energy Agency’s inspectors were often refused entry to key nuclear sites suspected of being involved in atomic weapons research – so there’s a lot that isn’t known. Best estimates suggest Iran’s “breakout” time – that is the length of time it will take Tehran to develop a nuclear weapon from where it is now – could be another seven months. Before the 2015 deal Iran had enough to potentially build more than a dozen bombs. The islamic republic has also threatened to restart construction of a heavy-water reactor that could produce plutonium -- potentially opening another path to amass fissile material for an atomic bomb. It took North Korea three years from the time it left nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty until it detonated its first atomic weapon. This latest escalation in the gulf followed a US drone airstrike which killed Iranian general Qasem Soleimani – long considered the world’s most important terrorist puppet master who organized and funded thousands of attacks by Iranian proxy militant terror groups such as Hezbollah, HAMAS, and Islamic Jihad. The 62 year old head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Quds Force was travelling in a convoy from Baghdad Airport -- with another key figure in Iran’s mostly Shi’ite terror network -- when they were hit. Retired U.S. General David Petraeus says Soleimani death was more significant than the elimination of al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden or Islamic State head Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The former CIA Director says Soleimani was responsible for the death of over 600 US soldiers and the architect and operational commander of Iran’s efforts to establish control over the entire middle east region. His network of Iranian proxy terrorist groups stretches from Pakistan and Afghanistan in the east, west across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, Bahrain, Cyprus, and the Palestinian territories. It extends across Africa to envelop Senegal, Gambia, Kenya, Sudan, and Egypt, and north into Turkey, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Bulgaria. His tentacles also spread to terror cells across Europe, India, eastern Asia, South America, and Mexico. While Shi’ite Muslims mourned his death and called for revenge – celebrations broke out across other parts of the Arab world where Soleimani was seen as a sadistic suppressor and war criminal who used violence and terror to maintain control of civilians. The US drone strike which killed Soleimani was carried out in retaliation for an attack on the American Embassy in Baghdad by Iranian backed militants. That followed air strikes by US forces on Iranian controlled Hezbollah militia who had earlier fired rockets on a US base in northern Iraq killing over a dozen people including an American contractor. Both Iranian sponsored attacks were organized by Soleimani. His death triggered a barrage of ballistic missile strikes from Iran – targeting American and coalition forces in Iraq. Ten missiles hit the Al-Assad Air Base, one hit a base in Erbil and four missiles failed to reach their targets. Tehran claimed it was a crushing revenge on American forces in retaliation for the assassination of Soleimani and killed over 80 American soldiers – however U.S. President Donald Trump says no American personnel were injured.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Zabelin/Getty

Why America Can't End Its 'Forever Wars'

— By William M. Arkin | 04/12/21 | Newsweek

A peace agreement with the Taliban and a May 1 deadline for American withdrawal of troops. A new pledge by President Biden to end the war. A Congressional step toward revoking the 20-year-old consent to use military force in Iraq. Talk, even, of rescinding the post-9/11 authorization to pursue Al-Qaeda. You might think America's forever wars are finally coming to an end. They're not—because everything we've learned from the past two decades at war has made it more difficult to actually end the wars.

Though the new administration seems intent on ending America's oldest war and there is growing fatigue over endless wars in the Middle East, and though the Pentagon is scrambling to refocus resources and attention away from counterterrorism to big war pursuits against the likes of Russia and China, war isn't going to actually end. That's because there is something about the way the United States fights—about how it has learned to fight in Afghanistan and on other 21st-century battlefields—that facilitates endless war.

This transformation of the American military happened gradually as the armed forces shifted the preponderance of tasks away from boots on the ground, away even from dependence on regular soldiers. The new American way of war moved even the means of bombing and killing—mostly through aircraft and drones, but also virtually in cyberspace—out of the actual war zones.

Troops shrunk in importance. There were no more armies to fight, no countries to occupy, and no appetite even to engage in hand-to-hand combat that put American lives at risk. What emerged is a certain kind of fighting, sustained by a flexible and reliable global network. The traditional measures of troop presence have become irrelevant while the means of actual warfare became invisible.

Take Afghanistan, for example. President Biden now says that the last remaining 2,500 "troops" in country will be withdrawn by the end of the year. And indeed, the last of the regular Army and Marine Corps units will come home. But these are not the only soldiers in the country, and the fighting—even on the ground—has shifted away from infantry to clandestine special operations and CIA paramilitaries. They exist uncounted, hidden behind a veil of secrecy and ignored in public tallies.

The American way of war actually makes it harder to end our "endless wars." Stocktrek Images/Getty

Fighting alongside them are others, also not troops. "Trainers" and technicians help Afghans to operate the billions' worth of equipment we've provided. The semi-combat elements of other agencies—the DEA and State Department, even the FBI—fight alongside them too, battling drugs, human trafficking and even corruption.

And then there are private contractors, who have become more and more intrinsic to everything military, even frontline operations. In Afghanistan, civilian contractors outnumber soldiers 7 to 1, and these non-soldier soldiers increasingly take on more and more direct military tasks. In fact, 54 different defense companies are right now advertising job openings in Afghanistan, looking for technicians to do everything from intelligence analysis and terrorist targeting to air conditioning repair.

The American way of war enables both troop withdrawals and continued fighting because over two decades of continuous warfare, new capabilities have emerged that fundamentally reorder the calculus on the ground. Capabilities that didn't even exist before 9/11—armed drones, autonomous precision strike, total surveillance, cyber warfare—have emerged and matured. But most important, The bulk of what sustains warfare in Afghanistan is located in the "safe" countries of the Middle East, even in Europe, and an increasingly larger proportion resides in the United States itself.

Linking this machine together is a global network that collects and processes mountains of information, moves that information around, sustains a worldwide targeting system, generates long range attacks, and makes most of the decisions. This extraordinarily complex network involves the participation of half the countries on earth. A hub—made up of giant command and intelligence centers—feeds spokes reaching out throughout the Middle East and South Asia, and into Africa and Asia. It is so little understood, so invisible, so resilient and so efficient, even as four successive presidents have promised and then tried to stop warfare, the spokes have grown and extended.

President Biden vows the Pentagon will move forward “in a transparent and principled manner.” Alex Wong/Getty

Perpetual war is this newly created machine itself. Today, that system comprises some two dozen countries where the U.S. is regularly bombing and killing. The American model facilitates "withdrawal" because with it, the very importance of "troops"— of actual boots that might be worn by soldiers on the ground—has virtually disappeared as a central element of killing terrorists. The consequence is not just that perpetual war increasingly takes place out of sight, but with fewer soldier deaths and injuries due to changed tactics and increasingly remote attacks, war also has become more and more irrelevant to American lives.

In our topsy-turvy world, the United States today is killing or bombing in perhaps 10 different countries. Some we know for sure: Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen. Some occasionally are acknowledged—Libya, Niger, Mali and Uganda. Others are more obscure—Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Lebanon, Nigeria. And still others—the Philippines, Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Thailand—are alluded to in fleeting news reports or hinted at in military deployments and supposed war games with host nation forces.

Beyond these 21 countries, American special operations forces are routinely present in some 70 additional countries, sometimes with partners and sometimes operating unilaterally, sometimes fighting against terror, and sometimes "fighting" against the endless forces of transnational organized crime, and sometimes even just collecting intelligence information and "preparing the battlefield" for future operations.

At the center of warfare in these countries—at the center of the perpetual war machine—are the back-end hubs of the Middle East, commands and bases in the supposedly safer countries outside combat zones—places like Jordan, Kuwait, Bah- rain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Djibouti. Here, the main headquarters are located, as are the main combat air and naval bases. The center of all air operations—the most important of all the centers—is located in the tiny Gulf state of Qatar, the army hub is in Kuwait, the navy hub is in Bahrain. This is where the majority of the preparatory work takes place.

In every country at the edge of this worldwide hub-and-spoke design where the actual bombing and killing takes place, the same Afghanistan math and model persists: There are acknowledged and unacknowledged forces; contractors mostly outnumber soldiers, operating clandestine and "low visibility" activities that substitute for the official and the acknowledged, and most of the lethal attacks come from outside the country. And the list of missions—policing the drug trade and stemming transnational organized crime, countering the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, dealing with long-range missiles and drones now owned by all, fighting cyber threats, defeating piracy, stopping illegal migration—justifies fighting almost everywhere.

The hub and the spokes are meshed together into a literal network—terrestrial, over the internet and in space—a global sensing and communicating machine which connects everyone "forward" and ultimately back to dozens of bases in the United States. So few are at the tip of the spear but that spear is also supercharged and precise, offering unprecedented flexibility. A hub that might be receiving and triaging intercepts or directing and flying drones one day with a focus on Syria can shift the next day to Libya, from Somalia one day to Nigeria the next.

Nowhere is this flexibility seen more clearly than in the January 3, 2020, drone strike that killed Iran's Quds force commander General Qasem Soleimani as he was leaving Baghdad International Airport. It was a masterful demonstration of expertise and America's unique global reach—of the perpetual war system itself.

US soldiers prepare the last convoy carrying US troops at Camp Adder on the outskirts of the southern city of Nasiriyah on December 17, 2011, marking the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq. Martin Bureau/AFP/Getty

While Trump administration officials deliberated in Washington and at Mar-a-Lago as to whether to pull the trigger, they never really had to ask about the how or even the likelihood of success. Behind the scenes, hundreds of uniformed specialists, civilians and contractors "worked the target," finding and then tracking the general's movements, intercepting and translating his (and other Iranian and Iraqi) communications, scheduling everything from satellite time to pilot shifts, preparing the drones and the other over-watch aircraft needed to fly, loading and arming the bombs that would be used, timing the movements, carrying out the air traffic control and complex choreography that was needed to bring it all together, even making the contacts with the involved governments to clear airspace and clear consent.

Thousands more kept the communications and networks open to support these "frontline" few, manning the command centers and headquarters, preparing the target graphics and preparing the briefings for the decision makers, providing minute-by-minute updates. These many thousands were spread out from local bases in Iraq and the Persian Gulf states to the military decision-making hub in Florida, to Georgia, where the listening and translating mostly occurred, to South Carolina, where the air effort was overseen, to dozens of other agencies and organization in the D.C. metropolitan area where the reconnaissance data was downloaded and processed.

It was a worldwide effort where the number of boots on the ground was utterly immaterial. The new American way of war means uniformed personnel, government civilians and private contractors leaving their homes throughout the United States to go to "war" in remote parts of the world, then returning home when their day of bombing and killing is over.

The killing of General Soleimani is not the exception. Since the new American way of war started as an effort to kill Al-Qaeda leaders and lieutenants, individuals have come to dominate the entire killing effort, even against the Islamic State. Other than small parts of Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, there are no real armies left to fight on the ground (or at least no desire to fight them force-on-force). For the United States, there is little interest in engaging terrorists in any kind of close hand-to-hand combat (that's the job of Afghan, Iraqi, Syrian and Kurdish "partners"). America—with its global network and possession of the greatest targeting information ever known to mankind—is the enabler of local and proxy killing.

The American focus—this machine's focus—is on finding and killing individuals, the more "high-value" the better. Targeting is the centerpiece of American global operations, the same information machine shifting from country to country and group to group almost seamlessly. This shift is even increasingly unconstrained by either language or culture. With a 21-nation battlefield against dozens of terrorist organizations on three continents, techniques like machine translation and big data exploitation are increasingly employed to process the Niagara of information.

Yet while there is no question that artificial intelligence enables greater flexibility, there is also a price. We are now 20 years into the era of post-9/11 perpetual war and there is still a scandalous shortage of linguists in the ranks (necessitating much of the outside contracting) and also a dearth of actual country and regional expertise. Even in Afghanistan, where perpetual war began in October 2001 and where the Pentagon has undertaken countless programs to build local expertise—foreign area officers, Afghan "hands," regionally oriented units—there is a contract linguist hired for every three soldiers.

The expertise that is truly valued is that which is necessary to operate the giant perpetual war network and all of the supporting software. Long-range precision targeting in an era of satellite navigation and individual weapons guidance that increasingly is able to autonomously loiter and search just needs a set of precise geographic coordinates where the target is located to do its job. It doesn't matter if it's Kabul or Kampala, Baghdad or Bangui.

The casket of firefighter Christopher Slutman leaves St. Thomas Church on April 26, 2019 in New York City. The Marine Corps Staff Sgt. was among three American service members killed by a roadside bomb in Afghanistan on April 8. Spencer Platt/Getty

Generating those coordinates demands endless numbers of back-end workers. As the U.S. war machine has developed, it isn't quite at the point where everyone is sitting at some remote keyboard, but the preponderance of those who "fight" this new kind of perpetual war are supporting a very small number of troops on the ground (or pilots in the air) who are actually in harm's way in places like Afghanistan or Iraq. It is a ratio of hundreds of thousands to one.

The efficiency is grossly misunderstood by those who count troops and believe the happy talk that emanates from officialdom that progress is being made, that forces are being withdrawn or that "ending" wars means either ending a war or connotes success. Another feature of perpetual war is that such deceptive and soothing war dispatches can be issued because one of the consequences of taking soldiers out of the equation of war is that the physical reality of actual combat—the sounds and smells of war—has grown distant to nearly everyone else in the machine. That's the internal effect.

Externally, the dominant position of information over metal maximizes American advantages while minimizing the number of American lives at risk. There is a double desire in the armed forces to avoid American deaths and injuries while also minimizing civilian casualties. First, minimizing American deaths and injuries is a sound military objective and a political necessity. Minimizing civilian harm is a humanitarian and strategic objective (as well as a legal requirement). But neither are altogether altruistic goals. Efficiency minimizes mistakes which thus suppresses news and thus facilitates frictionless continuation, free from interference from Congress, the public, the news media or even local governments.

Simply, the American way of war has become to make war as invisible as possible, not just because counterterrorism demands some special degree of secrecy, but also because operating in secret—at least secret from the American public—lets the government and the military continue without interference. Neither Congress nor the public has particularly clamored for transparency or an audit, and the national security establishment assumes that the American public doesn't want to know, which is to say that it doesn't want to be bothered by war because it largely doesn't have a stake in what happens and nor is it prepared to sacrifice anyway.

Unaudited and with poor measures of success, the Biden administration can assert that the Afghanistan war is ending because some level of stability has been created. This is despite consistent intelligence assessments that predict a disaster after the American withdrawal. Visiting Kabul last month, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin limited himself to saying that there would be a "responsible end" to the war, "responsible" mostly meaning that the paperwork would all be in order—that government consensus will be hammered out and obtained, that Congress will be neutralized, that the national security establishment will be silenced because it has run out of better ideas, that the Afghan government agrees (or is effectively bought off) and that American allies are on board. And finally, "responsible" means that no Americans will get injured or killed in the actual bug-out, that the scenes will be pleasing and triumphant.

U.S. service members walk off a helicopter on the runway at Camp Bost on September 11, 2017 in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. Andrew Renneisen/Getty

It's worth noting that this claim of being "responsible" was almost the exact same formulation General Lloyd Austin used when he was commander of U.S. forces in Iraq in 2011 when combat there was declared over as well, with a similar "withdrawal" of combat troops and with the Obama administration praising itself for ending "Bush's war." That is, before the Islamic State rampaged and the Iraq partners crumbled and the United States had to go back in 2014, bombing and killing in Syria and Iraq, where it still is engaged today, Afghanistan-style, increasingly remote and constantly struggling to minimize the number of troops involved and the level of American risk.

In the end, can anyone honestly look at the Middle East and say that there's been any success in two decades of war? That is, other than the laboratory success in building the capabilities of the American war machine and the global network. There is no question that as this system has matured, the number of American soldiers being killed and injured has dramatically declined. In fact, starting in about 2010, the number of contractor deaths and injuries began to exceed those in uniform.

Still, in 20 years of fighting, there have been almost 11,000 American deaths (including contractors) and more than 53,000 American have been physically broken, while countless others suffer from traumatic brain injuries and other post-traumatic disorders. The monetary cost to the American taxpayer is as much as $6.5 trillion, more than the defense budget of all the other nations combined, over six years of spending. It's twice the cost of annual health care for all Americans. It's 10 times the annual budget of the entire American public school system.

On February 25, U.S. fighter aircraft struck infrastructure targets in eastern Syria that it said were being utilized by Iranian-backed militant groups. The Pentagon announced that the strikes were "at President Biden's direction" and the news media reported that it was the first use of military force by the new administration.

Two days after the attack, the White House reported to Congress that the "United States always stands ready to take necessary and proportionate action in self-defense, including when...the government of the state where the threat is located is unwilling or unable to prevent the use of its territory by non-state militia groups responsible for such attacks."

US Marine and his translator listen to an elder from Trikh Nawar during a meeting with community leaders in the northeastern outskirts of Marjah on February 20, 2010. Patrick Baz/AFP/Getty

That's a dense Washington mouthful to decipher. First, though there's no mention of terrorism, the use of the term "non-state militia groups" intentionally expands the target description to include local insurgents but also drug cartels or organized criminal enterprises. Second, the unilateral justification—the administration is now explicitly saying that the United States will take action when a country where some nefarious activity is taking place doesn't, either because it is unwilling to or unable to do so. This Biden administration articulation isn't any different than the practice of the previous three administrations, but it serves as notice to Congress that "I told you I was going to do this" may be used to cover attacks that might be undertaken in the future.

The United States isn't quite back to the Clinton administration's humanitarian interventions of the 1990s, where protecting human rights was the doctrine to justify the use of military force in places like Somalia or the former Yugoslavia. But it also isn't the Congressionally approved, post-9/11 authorization to use military force against terrorism, against those responsible for the attacks. President Biden wrote to Congress, in justifying the Syrian attacks, that he directed military action "consistent with" his responsibility "to protect United States citizens both at home and abroad and in furtherance of United States national security and foreign policy interests, pursuant to my constitutional authority to conduct United States foreign relations and as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive."

If you think it might take a lawyer to parse out when military action isn't permissible under this formulation, you wouldn't be wrong. It takes hundreds working in the bowels of the national security establishment. Meanwhile, while Congress has taken a first step to repealing the now two-decades-old authorizations, there is no honest accounting of the where, how and why we're killing—how United States citizens are being protected and what security benefit are actually accruing to the United States in continuing perpetual war. The Biden administration seems to be making an end run on Congress and the public, embracing the model of minimal interference while also showing no intention of disrupting the machine itself.

This subtle shift in articulating why we continue to fight around the world is also seen in Secretary Austin's three-page introductory "Message to the Force" issued in March. Austin literally does not say the word "terrorism" in describing the priorities of the armed forces, only saying that as the Pentagon addresses accelerating competition in China and deals with the threats from Russia, Iran and North Korea (the priorities), it will also "disrupt transnational and non-state actor threats from violent extremist organizations, such as those operating in the Middle East, Africa and South and Central Asia."

That geographic broad brush is the battleground of perpetual war. It is a gilded quagmire of our own making.

Two civilian contractors prepare a US Army 14' Shadow surveillance drone before it's launched at Forward Operating Base Shank May 8, 2013 in Logar Province, Afghanistan. Robert Ninckelsberg/Getty

Austin also promises—as does President Biden—that the Pentagon will move forward "in a transparent and principled manner." In this objective, it is already failing. That February 25 strike in Syria? It was not the first of the Biden administration. But unless one had inside information, it would be difficult to determine that. The government stopped making regular strike summaries publicly available more than a year ago, and the Biden administration has taken no action to reverse that practice and be more transparent.

When Newsweek inquired about the numbers of Syria strikes that had taken place before February 25, the responsible command replied, "The process of gathering the information takes time, and we release it as soon as it becomes available." Not only has no data been released, but the Pentagon has also stopped issuing biweekly "progress highlights" from Syria and Iraq.

With regard to Afghanistan, the Defense Department Special Inspector General has also repeatedly complained that data on strikes, on Afghan military readiness and on the state of the many terrorist groups operating in country—data that previously was made available—has also been classified and kept from the public.

When it comes to other battlefields, public accounting is equally avoided, even when it is required by law. The president's "war powers" reports to Congress omit mention of fighting in controversial countries merely by declaring them "classified." The Secretary of Defense has also certified that reporting on certain countries is no longer necessary, not because the fighting has ended, but because U.S. "troops" haven't spent more than 60 days in country or the operations cost less than $100 million annually. In this way, reporting on U.S. bombing and killing in Yemen and Lebanon, in East Africa and in "Northwest Africa"—already sparse—has disappeared altogether.

There will be a “responsible end” to the war in Afghanistan, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin (pictured) has said. Michael Reynolds/EPA/Bloomberg/Getty

While that information has disappeared from the view of the American public, terrorist groups certainly know that the United States—even in the form of contractors who pretend to be locals—are there and attacking. Local populations know as well.

So, to put it bluntly, despite so much activity, despite the sacrifice of so many lives, despite enormous cost and despite countless excuses and justifications behind why we cannot stop fighting, we are neither defeating our enemies nor are we creating the conditions to become more secure. Yes, Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden are gone. But associating those special operations with success epitomizes the individualistic approach rather than representing any kind of honest assessment of greater security now or in the future.

After two decades of fighting, in fact, not one country in the Middle East—not one country in the world—can argue that it is safer than it was before 9/11. Every country that is now a part of the expanding battlefield of perpetual war is an even greater disaster zone than it was two decades ago.

It's clear that "ending" war in Afghanistan is not based upon the achievement of peace or stability, is not the result of the defeat of Al-Qaeda or the Taliban and comes amidst dynamic growth of the local affiliate of the Islamic State. For the future, continued fighting—even if it takes place under a new guise and hidden from view—will itself be stimuli for America's many enemies, who multiply and spread, thus ensuring perpetual war.

Perpetual war is a macabre bargain we live with. After 9/11, it seemed that the United States would pursue terrorists with every means possible and that the war would be ferocious, bloody and quick. But the American military also has its own culture—technologically driven, risk averse, precise—that condemns us to our own endless assembly line of doing what we are doing forever. Ending perpetual war isn't a formula, and the spread of the machine is so broad and ubiquitous that any single set of policy proposals—to stop fighting in this or that country or to eliminate this or that pro- gram—runs into unstoppable arguments. In the final analysis, ending perpetual war really means a psychological shift, one that derives from understanding the physicality of what's going on and one that demands an unsentimental look of what we're actually accomplishing.

— This essay is adapted from The Generals Have No Clothes: The Untold Story of Our Endless Wars, by William M. Arkin, published April 13th by Simon & Schuster.

0 notes

Text

Misreporting Iraq and Syria

By Patrick Cockburn, London Review of Books, February 3, 2017

The nadir of Western media coverage of the wars in Iraq and Syria has been the reporting of the siege of East Aleppo, which began in earnest in July and ended in December, when Syrian government forces took control of the last rebel-held areas and more than 100,000 civilians were evacuated. During the bombardment, TV networks and many newspapers appeared to lose interest in whether any given report was true or false and instead competed with one another to publicise the most eye-catching atrocity story even when there was little evidence that it had taken place. NBC news reported that more than forty civilians had been burned alive by government troops, vaguely sourcing the story to ‘the Arab media’. Another widely publicised story--it made headlines everywhere from the Daily Express to the New York Times--was that twenty women had committed suicide on the same morning to avoid being raped by the arriving soldiers, the source in this case being a well-known insurgent, Abdullah Othman, in a one-sentence quote given to the Daily Beast.

The most credible of these atrocity stories was given worldwide coverage by Rupert Colville, the spokesman for the UN High Commission for Human Rights, who said on 13 December that his agency had received reliable reports that 82 civilians, including 11 women and 13 children, had been killed by pro-government forces in several named locations in East Aleppo. The names of the dead were said to be known. Further inquiries by the UNHCHR in January raised the number of dead to 85, executed over a period of several days. Colville says the perpetrator was not the Syrian army, but two pro-government militia groups--al-Nujabah from Iraq and a Syrian Palestinian group called Liwa al-Quds--whose motives were ‘personal enmity and relatives against relatives’. Asked if there were other reports of civilians being executed in the final weeks of the siege, Colville said there were reports of members of the armed opposition shooting people trying to flee the rebel enclave. The murder of 85 civilians confirmed by multiple sources and the killing of an unknown number of people with bombs and shells were certainly atrocities. But it remains a gross exaggeration to compare the events in East Aleppo--as journalists and politicians on both sides of the Atlantic did in December--with the mass slaughter of 800,000 people in Rwanda in 1994 or more than 7000 in Srebrenica in 1995.

All wars always produce phony atrocity stories--along with real atrocities. But in the Syrian case fabricated news and one-sided reporting have taken over the news agenda to a degree probably not seen since the First World War. The ease with which propaganda can now be disseminated is frequently attributed to modern information technology: YouTube, smartphones, Facebook, Twitter. But this is to let mainstream media off the hook: it’s hardly surprising that in a civil war each side will use whatever means are available to publicise and exaggerate the crimes of the other, while denying or concealing similar actions by their own forces. The real reason that reporting of the Syrian conflict has been so inadequate is that Western news organisations have almost entirely outsourced their coverage to the rebel side.

Since at least 2013 it has been too dangerous for journalists to visit rebel-held areas because of well-founded fears that they will be kidnapped and held to ransom or murdered, usually by decapitation. Journalists who took the risk paid a heavy price: James Foley was kidnapped in November 2012 and executed by Islamic State in August 2014. Steven Sotloff was kidnapped in Aleppo in August 2013 and beheaded soon after Foley. But there is tremendous public demand to know what is happening in such places, and news providers, almost without exception, have responded by delegating their reporting to local media and political activists, who now appear regularly on television screens across the world. In areas controlled by people so dangerous no foreign journalist dare set foot among them, it has never been plausible that unaffiliated local citizens would be allowed to report freely.

In East Aleppo any reporting had to be done under licence from one of the Salafi-jihadi groups which dominated the armed opposition and controlled the area--including Jabhat al-Nusra, formerly known as the Syrian branch of al-Qaida. What happens to people who criticise, oppose or even act independently of these extremist groups was made clear in an Amnesty International report published last year and entitled ‘Torture Was My Punishment’: Abduction, Torture and Summary Killings under Armed Group Rule in Aleppo and Idlib. Ibrahim, whom al-Nusra fighters hung from the ceiling by his wrists while they beat him for holding a meeting to commemorate the 2011 uprising without their permission, is quoted as saying: ‘I heard and read about the government security forces’ torture techniques. I thought I would be safe from that now that I am living in an opposition-held area. I was wrong. I was subjected to the same torture techniques but at the hands of Jabhat al-Nusra.’

The fact that groups linked to al-Qaida had a monopoly on the supply of news from East Aleppo doesn’t necessarily mean that the reports in the press about the devastating effects of shelling and bombing were untrue. Pictures of flattened buildings and civilians covered in cement dust weren’t fabricated. But they were selective. It’s worth recalling that--according to UN figures--there were between 8000 and 10,000 rebel fighters in East Aleppo, yet almost none of the videos on TV ever showed any armed men. Western broadcasters commonly referred to the groups defending East Aleppo as ‘the opposition’ with no mention of al-Qaida or its associated groups. There was an implicit assumption that all the inhabitants of East Aleppo were firmly opposed to Assad and supported the insurgents, yet it’s striking that when offered a choice in mid-December only a third of evacuees– 36,000--asked to be taken to rebel-held Idlib. The majority--80,000--elected to go to government-held territory in West Aleppo. This isn’t necessarily because they expected to be treated well by the government authorities--it’s just that they believed life under the rebels would be even more dangerous. In the Syrian civil war, the choice is often between bad and worse.

The partisan reporting of the siege of East Aleppo presented it as a battle between good and evil: The Lord of the Rings, with Assad and Putin as Saruman and Sauron. By essentially handing over control of the news agenda to local militants, news organisations unwittingly gave them an incentive to eliminate--through intimidation, abduction and killing--any independent journalist, Syrian or non-Syrian, who might contradict what they were saying. Foreign leaders and the international media were at one time predicting slaughter on the scale of the worst massacres in postwar history. But, shamefully, by the time the siege came to an end they had completely lost interest in the story and in whether the horrors they had been reporting actually took place. Even more seriously, by presenting the siege of East Aleppo as the great humanitarian tragedy of 2016, they diverted attention from an even greater tragedy that was taking shape three hundred miles to the east in northern Iraq.

The offensive against Mosul, the biggest city still held by Islamic State, began on 17 October when Iraqi army troops, with the support of US-led air power, entered the city’s eastern districts. Expectations of a quick victory were soon disappointed when Iraqi soldiers began to suffer heavy casualties as small but highly mobile IS units of half a dozen fighters moved from house to house through hidden tunnels or holes cut in the walls to set up sniper positions, plant booby traps and bury IEDs. Local people whose houses were taken over say that the snipers were Chechens or Afghans who talked in broken Arabic. These fighters were supported by local IS men who also helped hide the suicide bombers who were to drive vehicles packed with explosives. There were 632 vehicle bombs during the first six weeks of the offensive. An IS squad would use a house until it had been pinpointed by Iraqi government forces and was about to be destroyed by heavy weapons or US-led airstrikes. Before the counterattack came they would move on to another house. IS has traditionally favoured fluid tactics, with each squad or detachment acting independently and with limited top-down control. Adapted to an urban environment, this approach allows small groups of fighters to harass much larger forces, by swiftly retreating and then infiltrating captured neighbourhoods so they have to be retaken again and again.

The Iraqi and US governments had every reason to play down the fact that they had failed to take Mosul and had instead been sucked into the biggest battle fought in Iraq and Syria since the US invasion in 2003. It was only in the second week of January that Iraqi special forces reached the River Tigris after ferocious fighting: with the support of US planes, helicopters, artillery and intelligence they had finally taken control of Mosul University, which had served as an IS headquarters for the eastern part of the city, along with the area’s 450,000 inhabitants. But reaching the Tigris was far from being the end of the fight. On 13 January, IS blew up the five bridges spanning the river. The city’s western part is a much greater challenge: home to 750,000 people, many of whom are thought to be sympathetic to IS, it’s a larger, poorer and older area, with closely packed streets that are easy to defend. Only the aid agencies, coping with the heavy civilian casualties and the prospects of a fight to the death by IS, appreciated the scale of what was happening: on 11 January, the UN Humanitarian Co-ordinator in Iraq, Lise Grande, said the city was ‘witnessing one of the largest urban military operations since the Second World War’. She warned that the intensity of the fighting was such that 47 per cent of those treated for gunshot wounds were civilians, far more than in other sieges of which the UN had experience. The nearest parallel to what is happening in Mosul would be the siege of Sarajevo between 1992 and 1995, in which 10,000 people were killed, or the siege of Grozny in 1994-95, in which an estimated 5500 civilians died. But the loss of life in Mosul could be much heavier than in either of those cities because it is defended by a movement which will not negotiate or surrender and kills anybody who shows any sign of wavering. IS believes death in battle is the supreme expression of Islamic faith, which fits in well with a doomed last stand.

Figures for wounded civilians in Mosul over the last three months may well exceed those for East Aleppo over the same period. This is partly because ten times as many people have been caught up in the fighting in Mosul, whose population according to the UN is 1.2 million; 116,000 civilians were evacuated from East Aleppo. Of that number, 2126 sick and war-wounded were evacuated to hospitals, according to the WHO. Casualties in the Mosul campaign are difficult to establish, partly because the Iraqi government and the US have been at pains to avoid giving figures.

A large number of losses were inflicted even before Mosul was fully surrounded: the last passable main road to Syria, down which have come food, medicine, fuel and cooking gas since IS captured the city two and a half years ago, was closed in November by Shia paramilitaries. Tracks are still open, but they are dangerous and often can’t be used during the winter rains. As a result, prices in the markets in Mosul have soared: the cost of a single egg has jumped five times, to 1000 Iraqi dinars. In the main vegetable and fruit market there are only potatoes and onions for sale, and at high prices. As cylinders of cooking gas run out, wood taken from abandoned building sites is selling at a premium. The siege is likely to be a long one: if IS is going to make a stand anywhere, it is better from its point of view to do so in Mosul, where the Iraqi government and the US military may be more restrained than elsewhere in Iraq in the use of their firepower. The precedents are ominous: in 2015-16 airstrikes and artillery fire destroyed 70 per cent of Ramadi, the capital of Anbar province, which had a population of 350,000. IS has every reason to fight to the end in Mosul: aside from being the second biggest city in Iraq, it has iconic significance for IS. It was here, in June 2014, that a few thousand of its fighters defeated an Iraqi government garrison of at least 20,000 soldiers; and it was on the back of this miraculous victory that IS’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, declared his caliphate. Those who are trapped in Mosul aren’t optimistic about their chances: ‘What we feared is happening,’ a woman in her sixties who gave her name as Fatima, told the online newsletter Niqash, which published an account of conditions in the city. ‘The siege is starting for real. From now on every seed and every drop of fuel counts because only god knows when this will end.’

Despite the ferocity of the fighting in Mosul, and warnings from the UN about casualties in the city potentially surpassing those in Sarajevo and Grozny, international attention has been almost exclusively directed at East Aleppo. It wouldn’t be the first time in the region that the Western press corps turned out to have been watching the wrong battle: I was in Baghdad in November 2004 when most Western journalists were covering the end of the siege of Fallujah. The Marines ultimately captured it, but the American generals understandably played down--and the media scarcely noticed--that while US troops were fighting in Fallujah, in central Iraq, insurgents had seized the much larger city of Mosul, in the north. That victory turned out to be significant, because the US army and the Iraqi government never truly regained uncontested control of the city, with the result that the predecessors of IS survived intense military pressure and re-established themselves, waiting until the revolt in Syria in 2011 gave them fresh opportunities.

There are many similarities between the sieges of Mosul and East Aleppo, but they were reported very differently. When civilians are killed or their houses destroyed during the US-led bombardment of Mosul, it is Islamic State that is said to be responsible for their deaths: they were being deployed as human shields. When Russia or Syria targets buildings in East Aleppo, Russia or Syria is blamed: the rebels have nothing to do with it. Heartrending images from East Aleppo showing dead, wounded and shellshocked children were broadcast around the world. But when, on 12 January, a video was posted online showing people searching for bodies in the ruins of a building in Mosul that appeared to have been destroyed by a US-led coalition airstrike, no Western television station carried the pictures. ‘We have got out 14 bodies so far,’ a haggard-looking man facing the camera says, ‘and there are still nine under the rubble.’

1 note

·

View note

Text

Iran Dominates in Iraq After U.S. ‘Handed the Country Over’

By Tim Arango, NY Times, July 15, 2017

BAGHDAD--Walk into almost any market in Iraq and the shelves are filled with goods from Iran--milk, yogurt, chicken. Turn on the television and channel after channel broadcasts programs sympathetic to Iran.

A new building goes up? It is likely that the cement and bricks came from Iran. And when bored young Iraqi men take pills to get high, the illicit drugs are likely to have been smuggled across the porous Iranian border.

And that’s not even the half of it. Across the country, Iranian-sponsored militias are hard at work establishing a corridor to move men and guns to proxy forces in Syria and Lebanon. And in the halls of power in Baghdad, even the most senior Iraqi cabinet officials have been blessed, or bounced out, by Iran’s leadership.

When the United States invaded Iraq 14 years ago to topple Saddam Hussein, it saw Iraq as a potential cornerstone of a democratic and Western-facing Middle East, and vast amounts of blood and treasure--about 4,500 American lives lost, more than $1 trillion spent--were poured into the cause.

From Day 1, Iran saw something else: a chance to make a client state of Iraq, a former enemy against which it fought a war in the 1980s so brutal, with chemical weapons and trench warfare, that historians look to World War I for analogies. If it succeeded, Iraq would never again pose a threat, and it could serve as a jumping-off point to spread Iranian influence around the region.

In that contest, Iran won, and the United States lost.

Over the past three years, Americans have focused on the battle against the Islamic State in Iraq, returning more than 5,000 troops to the country and helping to force the militants out of Iraq’s second-largest city, Mosul.

But Iran never lost sight of its mission: to dominate its neighbor so thoroughly that Iraq could never again endanger it militarily, and to use the country to effectively control a corridor from Tehran to the Mediterranean.

“Iranian influence is dominant,” said Hoshyar Zebari, who was ousted last year as finance minister because, he said, Iran distrusted his links to the United States. “It is paramount.”

The country’s dominance over Iraq has heightened sectarian tensions around the region, with Sunni states, and American allies, like Saudi Arabia mobilizing to oppose Iranian expansionism. But Iraq is only part of Iran’s expansion project; it has also used soft and hard power to extend its influence in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan, and throughout the region.

Iran is a Shiite state, and Iraq, a Shiite majority country, was ruled by an elite Sunni minority before the American invasion. The roots of the schism between Sunnis and Shiites, going back almost 1,400 years, lie in differences over the rightful leaders of Islam after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. But these days, it is about geopolitics as much as religion, with the divide expressed by different states that are adversaries, led by Saudi Arabia on one side and Iran on the other.

Iran’s influence in Iraq is not just ascendant, but diverse, projecting into military, political, economic and cultural affairs.

At some border posts in the south, Iraqi sovereignty is an afterthought. Busloads of young militia recruits cross into Iran without so much as a document check. They receive military training and are then flown to Syria, where they fight under the command of Iranian officers in defense of the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad.

Passing in the other direction, truck drivers pump Iranian products--food, household goods, illicit drugs--into what has become a vital and captive market.

Iran tips the scales to its favor in every area of commerce. In the city of Najaf, it even picks up the trash, after the provincial council there awarded a municipal contract to a private Iranian company. One member of the council, Zuhair al-Jibouri, resorted to a now-common Iraqi aphorism: “We import apples from Iran so we can give them away to Iranian pilgrims.”

Politically, Iran has a large number of allies in Iraq’s Parliament who can help secure its goals. And its influence over the choice of interior minister, through a militia and political group the Iranians built up in the 1980s to oppose Mr. Hussein, has given it substantial control over that ministry and the federal police.

Perhaps most crucial, Parliament passed a law last year that effectively made the constellation of Shiite militias a permanent fixture of Iraq’s security forces. This ensures Iraqi funding for the groups while effectively maintaining Iran’s control over some of the most powerful units.

Now, with new parliamentary elections on the horizon, Shiite militias have begun organizing themselves politically for a contest that could secure even more dominance for Iran over Iraq’s political system.

To gain advantage on the airwaves, new television channels set up with Iranian money and linked to Shiite militias broadcast news coverage portraying Iran as Iraq’s protector and the United States as a devious interloper.

Partly in an effort to contain Iran, the United States has indicated that it will keep troops behind in Iraq after the battle against the Islamic State. American diplomats have worked to emphasize the government security forces’ role in the fighting, and to shore up a prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, who has seemed more open to the United States than to Iran.

But after the United States’ abrupt withdrawal of troops in 2011, American constancy is still in question here--a broad failure of American foreign policy, with responsibility shared across three administrations.

Iran has been playing a deeper game, parlaying extensive religious ties with Iraq’s Shiite majority and a much wider network of local allies, as it makes the case that it is Iraq’s only reliable defender.

Iran’s great project in eastern Iraq may not look like much: a 15-mile stretch of dusty road, mostly gravel, through desert and scrub near the border in Diyala Province.

But it is an important new leg of Iran’s path through Iraq to Syria, and what it carries--Shiite militiamen, Iranian delegations, trade goods and military supplies--is its most valuable feature.

It is a piece of what analysts and Iranian officials say is Iran’s most pressing ambition: to exploit the chaos of the region to project influence across Iraq and beyond. Eventually, analysts say, Iran could use the corridor, established on the ground through militias under its control, to ship weapons and supplies to proxies in Syria, where Iran is an important backer of Mr. Assad, and to Lebanon and its ally Hezbollah.

At the border to the east is a new crossing built and secured by Iran. Like the relationship between the two countries, it is lopsided.

The checkpoint’s daily traffic includes up to 200 Iranian trucks, carrying fruit and yogurt, concrete and bricks, into Iraq. In the offices of Iraqi border guards, the candies and soda offered to guests come from Iran.

No loaded trucks go the other way.

“Iraq doesn’t have anything to offer Iran,” Vahid Gachi, the Iranian official in charge of the crossing, said in an interview in his office, as lines of tractor-trailers poured into Iraq. “Except for oil, Iraq relies on Iran for everything.”

The border post is also a critical transit point for Iran’s military leaders to send weapons and other supplies to proxies fighting the Islamic State in Iraq.

After the Islamic State, also known as ISIS, ISIL or Daesh, swept across Diyala and neighboring areas in 2014, Iran made clearing the province, a diverse area of Sunnis and Shiites, a priority.

It marshaled a huge force of Shiite militias, many trained in Iran and advised on the ground by Iranian officials. After a quick victory, Iranians and their militia allies set about securing their next interests here: marginalizing the province’s Sunni minority and securing a path to Syria. Iran has fought aggressively to keep its ally Mr. Assad in power in order to retain land access to its most important spinoff in the region, Hezbollah, the military and political force that dominates Lebanon and threatens Israel.

A word from Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, Iran’s powerful spymaster, sent an army of local Iraqi contractors scrambling, lining up trucks and bulldozers to help build the road, free of charge. Militiamen loyal to Iran were ordered to secure the site.

Uday al-Khadran, the Shiite mayor of Khalis District in Diyala, is a member of the Badr Organization, an Iraqi political party and militia established by Tehran in the 1980s to fight against Mr. Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war.

On an afternoon earlier this year, he spread a map across his desk and proudly discussed how he helped build the road, which he said was ordered by General Suleimani, the commander of the Quds Force, the branch of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps responsible for foreign operations. General Suleimani secretly directed Iran’s policy in Iraq after the American invasion in 2003, and was responsible for the deaths of hundreds of American soldiers in attacks carried out by militias under his control.

Mr. Khadran said the general’s new road would eventually be a shortcut for religious pilgrims from Iran to reach Samarra, Iraq, the location of an important shrine.

But he also acknowledged the route’s greater strategic significance as part of a corridor secured by Iranian proxies that extends across central and northern Iraq. The connecting series of roads skirts the western city of Mosul and stretches on to Tal Afar, an Islamic State-controlled city where Iranian-backed militias and Iranian advisers have set up a base at an airstrip on the outskirts.

“Diyala is the passage to Syria and Lebanon, and this is very important to Iran,” said Ali al-Daini, the Sunni chairman of the provincial council there.

Closer to Syria, Iranian-allied militias moved west of Mosul as the battle against the Islamic State unfolded there in recent months. The militias captured the town of Baaj, and then proceeded to the Syrian border, putting Iran on the cusp of completing its corridor.

Back east, in Diyala, Mr. Daini said he had been powerless to halt what he described as Iran’s dominance in the province.

When Mr. Daini goes to work, he said, he has to walk by posters of Iran’s revolutionary leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, outside the council building.

Iran’s militias in the province have been accused of widespread sectarian cleansing, pushing Sunnis from their homes to establish Shiite dominance and create a buffer zone on its border. The Islamic State was beaten in Diyala more than two years ago, but thousands of Sunni families still fill squalid camps, unable to return home.

Now, Diyala has become a showcase for how Iran views Shiite ascendancy as critical to its geopolitical goals.

“Iran is smarter than America,” said Nijat al-Taie, a Sunni member of the provincial council and an outspoken critic of Iran, which she calls the instigator of several assassination attempts against her. “They achieved their goals on the ground. America didn’t protect Iraq. They just toppled the regime and handed the country over to Iran.”

The lives of General Suleimani and other senior leaders in Tehran were shaped by the prolonged war with Iraq in the 1980s. The conflict left hundreds of thousands dead on both sides, and General Suleimani spent much of the war at the front, swiftly rising in rank as so many officers were killed.

“The Iran-Iraq war was the formative experience for all of Iran’s leaders,” said Ali Vaez, an Iran analyst at the International Crisis Group, a conflict resolution organization. “From Suleimani all the way down. It was their ‘never again’ moment.”

A border dispute over the Shatt al Arab waterway that was a factor in the hostilities has still not been resolved, and the legacy of the war’s brutality has influenced the Iranian government ever since, from its pursuit of nuclear weapons to its policy in Iraq.

“This is a permanent scar in their mind,” said Mowaffak al-Rubaie, a lawmaker and former national security adviser. “They are obsessed with Baathism, Saddam and the Iran-Iraq war.”

More than anything else, analysts say, it is the scarring legacy of that war that has driven Iranian ambitions to dominate Iraq.

Particularly in southern Iraq, where the population is mostly Shiite, signs of Iranian influence are everywhere.

Iranian-backed militias are the defenders of the Shiite shrines in the cities of Najaf and Karbala that drive trade and tourism. In local councils, Iranian-backed political parties have solid majorities, and campaign materials stress relationships with Shiite saints and Iranian clerics.

If the Iraqi government were stronger, said Mustaq al-Abady, a businessman from just outside Najaf, “then maybe we could open our factories instead of going to Iran.” He said his warehouse was crowded with Iranian imports because his government had done nothing to promote a private sector, police its borders or enforce customs duties.

Raad Fadhil al-Alwani, a merchant in Hilla, another southern city, imports cleaning supplies and floor tiles from Iran. He slaps “Made in Iraq” labels in Arabic on bottles of detergent, but the reality is that he owns a factory in Iran because labor is cheaper there.

“I feel like I am destroying the economy of Iraq,” he said. But he insists that Iraqi politicians, by deferring to Iranian pressure and refusing to support local industry, have made it hard to do anything else.

Iran’s pre-eminence in the Iraqi south has not come without resentment. Iraqi Shiites share a faith with Iran, but they also hold close their other identities as Iraqis and Arabs.

“Iraq belongs to the Arab League, not to Iran,” said Sheikh Fadhil al-Bidayri, a cleric at the religious seminary in Najaf. “Shiites are a majority in Iraq, but a minority in the world. As long as the Iranian government is controlling the Iraqi government, we don’t have a chance.”

In this region where the Islamic State’s military threat has never encroached, Iran’s security concerns are mostly being addressed by economic manipulation, Iraqi officials say. Trade in the south is often financed by Iran with credit, and incentives are offered to Iraqi traders to keep their cash in Iranian banks.

Baghdad’s banks play a role, too, as the financial anchors for Iraqi front companies used by Iran to gain access to dollars that can then finance the country’s broader geopolitical aims, said Entifadh Qanbar, a former aide to the Iraqi politician Ahmad Chalabi, who died in 2015.

“It’s very important for the Iranians to maintain corruption in Iraq,” he said.

For decades, Iran smuggled guns and bomb-making supplies through the vast swamps of southern Iraq. And young men were brought back and forth across the border, from one safe house to another--recruits going to Iran for training, and then back to Iraq to fight. At first the enemy was Mr. Hussein; later, it was the Americans.

Today, agents of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards openly recruit fighters in the Shiite-majority cities of southern Iraq. Buses filled with recruits easily pass border posts that officials say are essentially controlled by Iran--through its proxies on the Iraqi side, and its own border guards on the other.

While Iran has built up militias to fight against the Islamic State in Iraq, it has also mobilized an army of disaffected young Shiite Iraqi men to fight on its behalf in Syria.

Mohammad Kadhim, 31, is one of those foot soldiers for Iran, having served three tours in Syria. The recruiting pitch, he said, is mostly based in faith, to defend Shiite shrines in Syria. But Mr. Kadhim said he and his friends signed up more out of a need for jobs.

“I was just looking for money,” he said. “The majority of the youth I met fighting in Syria do it for the money.”

He signed up with a Revolutionary Guards recruiter in Najaf, and then was bused through southern Iraq and into Iran, where he underwent military training near Tehran.

After traveling to Iran, Mr. Kadhim came home for a break and then was shipped to Syria, where Hezbollah operatives trained him in sniper tactics.

Iran’s emphasis on defending the Shiite faith has led some here to conclude that its ultimate goal is to bring about an Iranian-style theocracy in Iraq. But there is a persistent sense that it just would not work in Iraq, which has a much larger native Sunni population and tradition, and Iraq’s clerics in Najaf, including Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, the world’s pre-eminent Shiite spiritual leader, oppose the Iranian system.

But Iran is taking steps to translate militia power into political power, much as it did with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and militia leaders have begun political organizing before next year’s parliamentary elections.

Ryan C. Crocker, the American ambassador in Iraq from 2007 to 2009, said that if the United States left again after the Islamic State was defeated, “it would be effectively just giving the Iranians a free rein.”