#rosalind e. krauss

Text

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc, (weatherproof steel), 1981 [installed at Federal Plaza, New York, NY; removed March 15, 1989] [MoMA, New York, NY. © Richard Serra / ARS, New York]

Bibl.: Rosalind E. Krauss, Richard Serra / Sculpture, Edited and with an introduction by Laura Rosenstock, Essay by Douglas Crimp, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, 1986, p. 137 (pdf here)

#graphic design#art#sculpture#structure#geometry#catalogue#catalog#richard serra#rosalind e. krauss#laura rosenstock#douglas crimp#moma#the museum of modern art#1980s

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nei giorni scorsi ho assistito a una prova aperta di The Garden, il nuovo lavoro di Gaetano Palermo, con Sara Bertolucci e Luca Gallio, che quest’anno è stato selezionato per la quarta edizione di ERetici_le strade dei teatri, il progetto di accoglienza, sostegno e accompagnamento critico, ideato e curato dal Centro di Residenza dell’Emilia Romagna.

In scena una black box ospita al suo interno un unico fermo immagine che solo alla fine si smaterializza lasciando lo spazio vuoto. Una donna, vestita con una sottoveste rosso mattone, è riversa a terra sul fondo destro del palcoscenico e lì resterà immobile, mossa solo da un respiro lento e profondo.

La dimensione immaginifica e di spaesamento che si crea per lo spettatore è dettata dalla drammaturgia sonora, che ad ogni cambio di brano amplia l’immaginario in nuove visioni, e dall’impianto luminoso, che resta statico dopo una prima accensione a lampi di neon. Per rifarci al titolo ci troviamo davanti a una natura morta, che fa però permeare di vita quell’immagine statica in ogni attimo che passa.

Fotografia o cinema? Teatro o dj set? Installazione o durational performance? O tutto questo insieme? L’impianto del lavoro è decisamente teatrale: come si diceva in principio, c’è una scena nera che si illumina quasi cinematograficamente per restare così, con la stessa tonalità di colore e luce, fino alla fine. Poi c’è la drammaturgia sonora che è ciò che da movimento a un’immagine altrimenti immobile e fa sì che lo spettatore proceda nella giustapposizione di immaginari e di significati.

Il dispositivo che il collettivo artistico mette in opera viene così definito da un crash mediale che fa collasse il cinema nel teatro, il teatro nel dj set, la fotografia nell’installazione e così via. Questo meccanismo inoltre sembra operare su quel piano di reinvenzione del medium di cui parla Rosalind Krauss (2005): facendo collassare sulla scena molteplici media il collettivo porta lo spettatore dentro il processo stesso, rendendo percettibile, grazie alla ripetizione all’infinito della stessa immagine, la finzione della rappresentazione e il funzionamento dell’immaginazione.

La mente così vaga tra le immagini della memoria: da un’apparizione lynchiana a una classica vittima del cinema di Hitchcock, da un corpo collassato durante un rave party al corpo a terra di Babbo Natale nella clip de La Verità di Brunori sas, dai corpi della cronaca nera a quello di Aylan riverso sulla spiaggia greca e così via, continuamente si creano e distruggono immagini nella mente di chi guarda.

In questa pratica mediante la quale si crea un ibrido, per restare anche nella metafora naturale, che incrocia più media, si assiste a una sorta di Iconoclash (Latour, 2005): accade allora che chi guarda si ritrova in una sorta di terra di mezzo, di indecisione dove non sa l’esatto ruolo di un’immagine, di un azione perché, nel caso di The Garden, questo si modifica non appena viene assimilato dell’occhio di chi guarda; e su questa scena ciò che accade è proprio questo: lo spettatore è messo davanti ad un’immagine iconica che cambia costantemente di significato e senso, passando dal sentimento del tragico a quello del comico fino a dissolversi svanendo ironicamente, rompendo il quadro della rappresentazione.

Una delle caratteristiche fondamentali delle immagini è, sempre per Bruno Latour, la loro capacità di scatenare passioni ed è proprio su questo meccanismo che sembra lavorare il collettivo guidato da Palermo che a settembre presenterà al pubblico una prova aperta di questo lavoro presso la Corte Ospitale di Rubiera dove si chiuderà il progetto ERetici.

*****************************************************

*Krauss, R. (2005). Reinventare il medium. Cinque saggi sull'arte d'oggi, a cura di Grazioli E., Mondadori, Milano.

* Latour, B. (2002). What is iconoclash? Or is there a world beyond the image wars. Iconoclash: Beyond the image wars in science, religion, and art, 14-37.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artedge n. 1. Il Grande Vetro di Mar-Cel Duchamp secondo una lettura post-strutturalista.

Il Grande Vetro di Marcel Duchamp o Richard Mutt o Rose Selavy è probabilmente una delle opere d’arte più significative del XX secolo, ma nessuno lo avrebbe detto nel 1923. Per comprenderne la grandezza è, infatti, opportuno ripercorrere alcune tappe fondamentali di Mar-Cel, la cui frammentazione della propria soggettività è forse il lascito più grande dell’artista.

Duchamp, il grande Duchamp che conosciamo noi oggi, esordì, fallendo, al XXVIII Salons des Indépendants di Parigi dove, allontanandosi dal Cubismo dei fratelli e pittori già affermati, propose il suo “Nudo che scende le scale”, che risentiva piuttosto di un’estetica futurista. L’opera venne rifiutata dal comitato ed il rifiuto portò Duchamp a vivere un vero e proprio trauma. Nell’estate del 1912 Duchamp si trasferì a Monaco, definita da egli stesso come “la scena della mia completa liberazione”, probabilmente dall’aspetto retinico dell’avanguardia parigina - “retinico” veniva usato dall’artista per indicare la pittura che non impegna la “materia grigia” della mente ed è un aspetto non trascurabile se si vede in Duchamp il padre del Concettualismo, e lo è -. Tuttavia, dopo l’esperienza a Monaco, due furono gli eventi che segnarono principalmente la carriera di Duchamp: l’incontro con Raymond Russel, che mostrò gli stratagemmi con cui combinava caso e scelta e il Salon de la Locomotion, tenutosi a Parigi nel 1912 e al quale confidò all’amico Brancusi “La pittura è finita. Chi può fare meglio di questa elica? Dimmi puoi farlo?”. Probabilmente il Salon de la Locomotion è più pertinente se si parla di readymade. Ciò che interessa a noi è piuttosto il caso, che definisce il Grande Vetro.

Nel 1915, a causa della Grande Guerra e similmente ad altri artisti, Duchamp si trasferirà come esule a New York e qui comincerà a lavorare intorno, sopra, dentro e fuori al Grande Vetro. “La sposa messa a nudo dai suoi celibi”, nota anche con il nome di Grande Vetro, non era, tecnicamente parlando, un dipinto. Si trattava di un vetro composto da due pannelli a cui si dedicava con molti materiali curiosi: polvere, oggetti di piombo e argento. A tale opera Duchamp lavorava sporadicamente, passando più tempo a creare un clima concettuale intorno alla sua opera attraverso una quantità di note che appuntava nella cosiddetta “Scatola verde”, pubblicata poi nel 1934. Le interpretazioni sul Grande Vetro sono tra le più varie: dal religioso all’erotico, ed in queste poco aiutano le annotazioni quasi febbrili dello stesso autore, che tra l’altro nel 1923 dichiarò conclusa l’opera come “incompiuta”.

La lettura di Rosalind Krauss -che mi permetto di definire una delle letture più complete mai lette nella storia dell’arte- guarda al Grande Vetro come una fotografia. Krauss dice che sebbene possa sembrare contraddittoria la lettura fotografica dobbiamo tenere in mente due cose: la prima è il forte realismo degli oggetti “fissati” nel vetro e la seconda è l’impenetrabilità dell’allegoria stessa, espressa da un lato da un ingranaggio metallico che ospita i Celibi (in francese “CELibataires” e da qui “MarCEL”), dall’altro da una nuvola amorfa e sempre metallica che ospita la Sposa (in francese “MARiee” e da qui “MARcel”). Ed in questo senso Mar-Cel. Le ambiguità non vennero risolte dopo la pubblicazione delle Note, ma anzi aumentarono le chiavi di lettura dell’opera, prima fondante solo sulla didascalia (”La sposa messa a nudo dai suoi celibi” ). Per questo motivo Krauss va incontro al carattere fotografico che collega i due aspetti del Grande Vetro, ovvero il suo verismo e la sua resistenza all’interpretazione. Sulla base di questo Krauss dice che le fotografie non contengono la loro interpretazione come i dipinti, piuttosto, in quanto prese direttamente dalla realtà, le fotografie sono la manifestazione di un fatto e la loro spiegazione spesso dipende da un testo aggiunto, come la didascalia (in questo caso: la sposa messa a nudo dai suoi celibi). Prima di addentrarsi in questa lettura è opportuna la considerazione di Roland Barthes, che ha definito questo carattere della fotografia come “messaggio senza codice”. Le parole emergono da un fondo di linguaggio organizzato su regole grammaticali e lascito lessicale -quindi da un sistema ben codificato- ed è proprio all’interno di questo sistema che le parole trovano il loro significato: sono simboli per dirlo in termini di semiologia. Le immagini sono icone, perché sono legate ai loro referenti -non per convenzione, come le parole- ma attraverso la somiglianza. L’ultimo di questi segni è l’indice, che è letteralmente causato dal suo referente e per questo intrattiene un legame materiale con esso.

L’indice è ciò che si trova in Duchamp: le forme coniche dei setacci -la parte dell’apparato dei Celibi in cui vi è condensato il desiderio maschile- è indice della fissazione della polvere depositata sul vetro per mesi; così come i nove spari -raggi del desiderio che penetrano nel regno della Sposa- sono indice di dove hanno colpito la superficie nove fiammiferi; o ancora i pistoni di corrente ad aria -i riquadri dentro la nuvola della Sposa- che rimandano alla stessa tecnica utilizzata per “Tre rammendi-tipo,1913-14”, che fonda sul concetto di caso. Sulla base di questa lettura si può giungere a cogliere il significato dell’opera, che ruota intorno alle questioni che stimolano la produzione di Duchamp: l’indice non implica solo uno spostamento del tipo di segno utilizzato -da iconico a indicale-, ma anche un profondo cambiamento nel processo artistico. In che senso? L’indice, essendo la traccia di un evento -come l’herpes è la traccia di un virus-, è dettato dalla pura casualità: il caso esclude il desiderio dell’artista tradizionale di comporre la propria opera, annullando l’idea di abilità collegata all’artista. L’uso del caso, così come se ne serve Duchamp, meccanizza l’operare dell’artista. Seguendo questo ragionamento, allora, anche "Ruota di bicicletta” e “Scolabottiglie” sono indice di un evento, ovvero del loro incontro con Duchamp. In tal senso il “ripetibile” -oggetto seriale- diventa frutto di un “evento unico”, ovvero il suo incontro -fisico- con l’artista, così come la fotografia è indice -segno- dell’incontro fisico della luce su carta sensibile.

Silvia Trevisan

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jackson Pollock. “Summertime”: Number 9A.

1948. Oil and enamel on canvas, 33 1/4 by 218 inches

The great Pollocks, like the great Mondrians, operate through a structure of oppositions: line as opposed to color; contour as opposed to field; matter as opposed to the incorporeal. The subject that then emerges is the provisional unity of the identity of opposites: as line becomes color, contour becomes field, and matter becomes light. Pollock characterized this as “energy and motion made visible”; Lee Krasner spoke of it as “unframed space.” Pollock’s most serious critics have described it with great care and eloquence.

There is nothing “formalist” about this ambition. Its subject — the operation of an abstract logic — also contained the psychological, although a condition of the psychological that was de-specified, like a dream that is both charged with feeling and stripped of images. So, to the above characterization of his art, Pollock adds “memories arrested in space.” The absorption of the “image” into the dialectical structure, so that memories arrested in space assume the same level of abstraction as everything else, was constant in Pollock’s work. Not only is contour as such (that is, the formal means of calling forth the figure) the major visual resource of Pollock’s mature art; but, more to the point, there is not one single year (with the possible exception of 1950) when he is not operating specifically with the binary opposition figure/nonfigure, which means infiltrating a nonspecific figuration into the linear matrix of even the allover paintings. We have only to think of Summertime from 1948, or Our of the Web from 1949, or Ocean Greyness from 1953. Beyond the in-painting of certain areas, Pollock’s technical inventiveness extended to the excision of shapes from the canvas grounds as well as the exploitation of collage elements torn from abstract, linear drawings.

from “Reading Jackson Pollock, Abstractly”, Rosalind E. Krauss

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Medium is the Message, Marshall McLuhan

The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Rosalind E. Krauss

0 notes

Text

Chat GPT & Art: A Research Conversation with AI.

Yes, there are several famous mixed media artists who have made significant contributions to the art world. Here are a few notable mixed media artists:

Joseph Cornell: Known for his intricate shadow boxes and assemblage art, Cornell's work often combined found objects, images, and text.

Robert Rauschenberg: Rauschenberg was a pioneer in combining various materials and techniques, blurring the line between painting and sculpture.

Louise Nevelson: She was renowned for her monochromatic, abstract sculptures created from found wooden objects and architectural elements.

Anselm Kiefer: Kiefer's work often incorporates a wide range of materials, including lead, straw, and ash, creating large-scale mixed media paintings.

Rosalind E. Krauss: An influential art critic and theorist, Krauss has written extensively on the subject of mixed media art and its significance in contemporary art.

Jasper Johns: Johns is known for his use of encaustic paint, collage, and mixed media in his artwork, which played a pivotal role in the Pop Art movement.

These artists have pushed the boundaries of traditional artistic mediums, creating innovative and thought-provoking works that continue to inspire and influence contemporary artists.

Mixed media art has also had a significant impact on society in several ways:

Diversity of Expression: Mixed media art encourages diversity in artistic expression. Artists can combine various materials, techniques, and ideas to create unique and individualistic works, reflecting the complexity of modern society.

Interdisciplinary Influence: Mixed media blurs the boundaries between art and other disciplines, such as literature, science, technology, and more. This interdisciplinary approach can lead to innovative and thought-provoking creations that resonate with a broad audience.

Environmental Awareness: Some mixed media artists use recycled or found materials, promoting environmental awareness and sustainability. This aspect of mixed media art aligns with the growing concern for eco-consciousness in contemporary society.

Cultural Exploration: Mixed media often allows artists to explore and celebrate diverse cultural backgrounds. It can be a platform for the expression of multicultural experiences and perspectives.

Storytelling and Narrative: Mixed media art often incorporates narrative elements, allowing artists to tell stories or convey social and political messages. These artworks can serve as a means of storytelling and addressing important societal issues.

Engagement with Technology: With the integration of digital and technological elements, mixed media art engages with modern society's ever-evolving relationship with technology, leading to the creation of digital and interactive mixed media works.

Accessibility: Mixed media art, like pop art, contributes to the democratization of art. Its use of diverse and often more affordable materials can make art more accessible to a wider audience.

Inspiration for Collaboration: Mixed media art encourages collaboration between artists from different fields, fostering a sense of community and creative exchange. This collaborative spirit is an important aspect of contemporary artistic practice.

In essence, mixed media art reflects the complexities, diversity, and interconnectedness of modern society. It challenges traditional artistic boundaries and offers a dynamic platform for artists to express themselves and engage with the world around them, making it a relevant and influential form of artistic expression in today's society.

In the early 20th century, artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque experimented with collage, incorporating pieces of paper and other materials into their paintings. The Dada movement in the 1910s and 1920s also embraced the use of found objects and unconventional materials in art.The term "mixed media" started to be used more widely to describe works of art that combined different materials and techniques. It gained further popularity during the mid-20th century as artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns explored the possibilities of mixed media in their art.Since then, mixed media art has continued to evolve and diversify, becoming a significant and recognized art form in its own right. It has played a crucial role in challenging traditional artistic boundaries and expanding the possibilities of artistic expression.

0 notes

Text

Evaluation

In response to both modules, I began thinking about my experience with cultural hybridity and my relationship to cultural identity. My initial notions on this topic centred around the struggles of being third culture (or cross-cultural), meaning that I was born of a Turkish father and Scottish mother and how the distance to my Turkish heritage created a void in my identity.

I decided early on that it would be more valuable for me to utilise a unified conceptual framework for both Process and Enquiry and Visual Language – I believe this allowed me to broaden my scope of research and really expand my own understanding of these ideas. I primarily used online platforms like JSTOR for academic journals and book reviews for my research – I put an emphasis on the quality of the texts I was consuming in this project. Some notable texts I read were: “The Crucible Within” by Ruben G. Rambuat; “Adult Third Culture Kids” By Ruth Hill Useem and Ann Baker Cottrell; and “Third Culture Kids” by David C. Pollock and Ruth Van E. Reken; to name a few. There were a few central ideas in these texts which informed my practice further: third culture is a shared experience; third culture kids experience the world in a truly unique way, even differently to their parents; experiences related to cultural hybridity - such as self-identification, aspirations, discrimination and assimilation into culture are more objective markers of development of these children.

I really valued the workshops provided - I developed my own work using practices from multiple workshops including: bone china burnout; paper vessels; envelope poems and folded forms.

Within Visual Language, I considered both the Index and Stranger briefs though workshop activities and additional reading materials – through this I made the choice to pursue the Index brief. I found Rosalind Krauss’ Notes on the Index to be engaging, particularly her ideas on pronouns as ‘shapeshifters’ – to understand language as signs was a new concept to me and one that I wanted to delve into. Furthermore, Krauss’ discussion of the ‘mirror stage’ whereby a child experiences themselves as a being which is physically distant from themselves though their own reflection resonated with my own ideas of feeling distant and alienated by my own identity. Krauss’ ideas informed my own practice by giving me a new perspective of my culture and upbringing – that these experiences could be viewed as indices.

Folding, dipping and firing my poems became the focal point of my practice. This process is inherently indexical as the final stage of the process (the firing) left traces of the original objects, tangible fold lines and unfold lines are perfectly preserved in the objects. I let these objects be what they are, without judgement or preconceptions of what they would be. Through this I learned that my actions and intentions hold more significance than the aesthetic outcome.

Initially I struggled to understand what Process and Enquiry was asking of me. I found it particularly important to discuss the brief and module in tutorials. I learned that being honest in these discussions was for my own benefit and ultimately the only solution in moving forward.

In this module, I tried to simplify my ideas into specific areas of interest as my subject matter was incredibly broad. I learned of a Turkish phrase which perfectly encapsulated the feelings I was trying to convey; ‘Ait olma’ which translates to the feeling of longing for belonging.

Overall, I believe I used my time in studio to the best of my ability – I have mostly been in 5 days per week, with few exceptions. I have a challenging home life being an unpaid carer for my chronically ill and disabled partner and having my own challenges with ADHD and so I am proud of my commitment to this course. I have made a considered effort to expand my understanding of contemporary art by visiting exhibitions in Glasgow however, I would like to build on this and make this a more habitual practice. I Something I would also like to improve on is my time management – I have access to help with this through learning support but I have not taken full advantage of this. I can manage this on my own however I have learned that in degree level study I should absolutely be making full use of the resources I have.

0 notes

Text

Evaluation

In response to both modules, I began thinking about my experience with cultural hybridity and my relationship to cultural identity. My initial notions on this topic centred around the struggles of being third culture (or cross-cultural), meaning that I was born of a Turkish father and Scottish mother and how the distance to my Turkish heritage created a void in my identity.

I decided early on that it would be more valuable for me to utilise a unified conceptual framework for both Process and Enquiry and Visual Language – I believe this allowed me to broaden my scope of research and really expand my own understanding of these ideas. I primarily used online platforms like JSTOR for academic journals and book reviews for my research – I put an emphasis on the quality of the texts I was consuming in this project. Some notable texts I read were: “The Crucible Within” by Ruben G. Rambuat; “Adult Third Culture Kids” By Ruth Hill Useem and Ann Baker Cottrell; and “Third Culture Kids” by David C. Pollock and Ruth Van E. Reken; to name a few. There were a few central ideas in these texts which informed my practice further: third culture is a shared experience; third culture kids experience the world in a truly unique way, even differently to their parents; experiences related to cultural hybridity - such as self-identification, aspirations, discrimination and assimilation into culture are more objective markers of development of these children.

I really valued the workshops provided - I developed my own work using practices from multiple workshops including: bone china burnout; paper vessels; envelope poems and folded forms.

Within Visual Language, I considered both the Index and Stranger briefs though workshop activities and additional reading materials – through this I made the choice to pursue the Index brief. I found Rosalind Krauss’ Notes on the Index to be engaging, particularly her ideas on pronouns as ‘shapeshifters’ – to understand language as signs was a new concept to me and one that I wanted to delve into. Furthermore, Krauss’ discussion of the ‘mirror stage’ whereby a child experiences themselves as a being which is physically distant from themselves though their own reflection resonated with my own ideas of feeling distant and alienated by my own identity. Krauss’ ideas informed my own practice by giving me a new perspective of my culture and upbringing – that these experiences could be viewed as indices.

Folding, dipping and firing my poems became the focal point of my practice. This process is inherently indexical as the final stage of the process (the firing) left traces of the original objects, tangible fold lines and unfold lines are perfectly preserved in the objects. I let these objects be what they are, without judgement or preconceptions of what they would be. Through this I learned that my actions and intentions hold more significance than the aesthetic outcome.

Initially I struggled to understand what Process and Enquiry was asking of me. I found it particularly important to discuss the brief and module in tutorials. I learned that being honest in these discussions was for my own benefit and ultimately the only solution in moving forward.

In this module, I tried to simplify my ideas into specific areas of interest as my subject matter was incredibly broad. I learned of a Turkish phrase which perfectly encapsulated the feelings I was trying to convey; ‘Ait olma’ which translates to the feeling of longing for belonging.

Overall, I believe I used my time in studio to the best of my ability – I have mostly been in 5 days per week, with few exceptions. I have a challenging home life being an unpaid carer for my chronically ill and disabled partner and having my own challenges with ADHD and so I am proud of my commitment to this course. I have made a considered effort to expand my understanding of contemporary art by visiting exhibitions in Glasgow however, I would like to build on this and make this a more habitual practice. I Something I would also like to improve on is my time management – I have access to help with this through learning support but I have not taken full advantage of this. I can manage this on my own however I have learned that in degree level study I should absolutely be making full use of the resources I have.

0 notes

Text

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc, (weatherproof steel), 1981 [installed at Federal Plaza, New York, NY; removed March 15, 1989] [MoMA, New York, NY. © Richard Serra / ARS, New York]

Bibl.: Rosalind E. Krauss, Richard Serra / Sculpture, Edited and with an introduction by Laura Rosenstock, Essay by Douglas Crimp, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, 1986, p. 52 (pdf here)

#art#sculpture#structure#geometry#catalogue#catalog#richard serra#rosalind e. krauss#laura rosenstock#douglas crimp#moma#the museum of modern art#1980s

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cantaloupe island guitar pdf plans

CANTALOUPE ISLAND GUITAR PDF PLANS >>Download (Descargar)

vk.cc/c7jKeU

CANTALOUPE ISLAND GUITAR PDF PLANS >> Leer en línea

bit.do/fSmfG

como estudiar jazzjazz duets

improvisar jazz

jazz duets login

Saint lary plan des pistes pdf, Misty may treanor back tattoo, Highly decorated us soldiers, Easy 1000 island dressing, Brown and white moose, 4 jun 2013 — ple also make reed boats to travel to the mainland. What do you think life is like on these islands? Islas de los Uros en el lago Titicaca 4 nov 2018 — PDF disponible aca: gum.co/baEAF jazzduets.com/shop English Version: youtube.com/watch?v=Z9YzG. por J GONZÁLEZ — ajustadamente posible el plan de estudios a las particularidades de cada individuo. "Cantaloupe island "de Herbie Hancock, "The Preacher" y Sister. 5 CHORDS. 5 DAYS. 5 DAYS OFF. 5 DE SEPTIEMBRE. 5 FOR HER 3 FOR HIM 6 A M GUITAR VERSION. 6 DIAS 7 NOCHES BANCO SABADELL PLAN COMPROMIS 201501. por SR Cogua Abadía · 2020 — Solo Guitar, Musical Composition, Bright Size Life, First Circle, Jazz, Question And Answer, Cantaloupe Island interpretadas por Pat Metheny. Tico-tico Alto Saxophone - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. h. Cantaloupe Island - Full Big Band - Mike Kamuf. Download Free PDF 8 Cfr. Rosalind E. Krauss, “'The Rock': William Kentridge's Drawings for One's landfill is someone else's treasure island.

https://www.tumblr.com/witepixuxome/698281929279258625/epemag-pdf-editor, https://www.tumblr.com/witepixuxome/698282028775440384/parthibo-shirshendu-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/witepixuxome/698282028775440384/parthibo-shirshendu-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/witepixuxome/698282028775440384/parthibo-shirshendu-pdf, https://www.tumblr.com/witepixuxome/698282028775440384/parthibo-shirshendu-pdf.

0 notes

Photo

Britt Sondreal, “Flame”, 2007

http://www.brittsondreal.com/index.cfm

*

(...)In Freud's view, the oceanic feeling is at one and at the same time the basis of religious sentiments and the ground of a limitless narcissism, the infant's experience of a total lack of difference between itself and its world. It is this very lack of difference that, Freud also asserts, allows from primitive man to see nature as an extension of himself and thus, in phallicizing the fire, to enter into aggressive, sexualized play with it. Civilization will deeroticize the fire, returning it to the reality of its naturalized, desymbolized difference from the human sphere. Civilization will strip the oceanic of this aggressive, undifferenciated lining, will repress it.(...)

Rosalind E. Krauss, from “The Optical Unconscious”

#britt sondreal#photography#fire#rosalind e. krauss#the optical unconscious#deerotization of fire by civilization#desymbolized fire

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Contextual Research - Rosalind E. Krauss

Rosalind E. Krauss is a highly influential critic and theorist, working with theories of aesthetics in art that capture a theme or historical and/or cultural issue. Since 1965 she has published her work in Artforum (of which she was also co-editor from 1971 to 1974), Art International and Art in America. In 1976 she co-founded October, an academic journal specialising in contemporary art, criticism, and theory, with fellow critic Annette Michelson. Krauss used her position at October in order to publish essays on post-structuralist art theory, postmodernism, psychoanalysis, deconstructionist theory, and feminism. October also stressed the significant, historical importance of early 20th-century avant-garde art, such as Cubism, Expressionism, and Surrealism.

Krauss’ most well-known contribution to art criticism came was the theory that, by the 1970s, the art world had entered a “post-medium” age, wherein an artist’s media had become irrelevant. This is in direct conflict with the theory of her former mentor Clement Greenberg, which prioritized medium as an artwork’s most expressive feature. According to Krauss, “post-medium” forms of art had everything to do with the work’s expressive power and historical contextualisation, instead of a pure artistic medium.

Since 2005, she has been Professor of Modern Art and Theory at Columbia University in New York City.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

What does it mean to take a stand against illustration? And more importantly, what does it mean to call oneself an abstract artist who nevertheless has a subject? The claim that abstract art constructs a visual/auditory/verbal “equivalent” for experience is a claim that has been voiced since the late nineteenth century. Pollock, as we have seen, also thought in terms of the “equivalent.” But he knew that for some people there was an internal contradiction between the idea of abstraction and the idea of subject. In 1950, speaking for publication in The New Yorker, he chose the term that would leave the least doubt about where he stood at the level of a simple either/or. “I decided to stop adding to the confusion,” he said, referring to the numerical titles he was now giving his work. “Abstract painting is abstract. I confronts you.”

But the problem, of course, is that the either/or is a misrepresentation of what an abstract painter is up to. His greatest fear is that he may be making mere abstraction, abstraction uninformed by a subject, contentless abstraction, for which the term — wholly pejorative for everyone from Kandinsky and Mondrian to Pollock and Newman — is decoration.

Pollock’s painting was a frequent target for the accusation that what he was doing was nothing but decoration — so much so that in reviewing Pollock’s 1948 exhibition Clement Greenberg made the acerbic aside, “I already hear: ‘wallpaper patterns,’” before going in to analyze and defend the work. And this general accusation, in its utter failure to grasp Pollock’s subject, or even to see that his work had a subject, is reported as having been extremely upsetting to the artist.

The reason that Newman’s “most people” have to reduce the pair abstraction/subject to an either/or is because most people think that the work of art is a picture and that its subject is what it is a picture of. What’s in the work is what the work pictures. The dog, or landscape, or a black square, is the work’s referent. It is what the work is about. Thus a work in which nothing is pictured cannot be a work that is about something. Nor, by the same token, can there be a serious work that is about nothing.

But the twentieth century’s first wave of pure abstraction was based on the goal, taken most seriously indeed, to make a work about Nothing. The uppercase n in Nothing is the marker of this absolute seriousness. If anything ever drove Mondrian and Malevich, it was Hegelianism and the notion that the vocation of art was defined by its special place in the progress of Spirit. The ambition finally to succeed at painting nothing is fired by the dream of being able to paint Nothing, which is to say, all Being once it has been stripped of every quality that would materialize or limit it in anyway. So purified, this Being is identical with Nothing. It is onto this experience of identity that Hegel’s dialectic opens. To wish to paint the operations of the dialectic is no small ambition. One very page of his writing Mondrian invokes Hegel. His dicta about “dynamic equilibrium” translate into the grand condition of his subject, another term for Becoming. There is no way into this art without grasping the full degree of abstraction of Hegel’s logic.

from “Reading Jackson Pollock, Abstractly”, Rosalind E. Krauss

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Book of Disquiet - echoes

Better to write than to dare live - even if living means merely to buy bananas in the sunlight, as long as the sun lasts and there are bananas for sale

I love you. I love you,

but I’m turning to my verses

and my heart is closing

like a fist.

-

Perhaps he makes a choice. / What choice? / He chooses the memory of her. That’s why he turns. He doesn’t make the lover’s choice, but the poet’s.

From so much self-revising, I’ve destroyed myself. From so much self-thinking I’m now my thought and not I.

I wanted to explain myself to myself in an understandable way.

I gave shape to my fears and made excuses. I varied my velocities, watched myselves sleep. Something’s not right about what I’m doing but I’m still doing it- living in the worst parts, ruining myself.

The relationship between one soul and another, expressed through such uncertain and variable things as shared words and preferred gestures, are deceptively complex. The very act of meeting each other is a non meeting. Two people say I love you or mutually think it and feel it, and each mind has a different idea, a different life, perhaps even a different colour or fragrance, in the abstract sum of impression that constitutes the soul’s activity.

A friend points out to me: "to say of someone that he's handsome is to imprison him in his beauty"! I say: yes, it's true, but all the same: not too fast! let's not go too fast! It's beautiful, it's free, it's human. It might end up being necessary to let go {faire son deuil} of desire (that's what psychoanalysis tells us), but let's not do it right away: pleasure of desire, of the adjective: so that "truth" (if there is any) not be immediate: pleasure of the lure: the sculptor Sarrasine died from truth (Zambinella was nothing but a castrato), but he got pleasure from the lure (Zambinella was an adorable woman): without the lure, without the adjective, nothing would happen

-

“I will never know how you see red and you will never know how I see it.

But this separation of consciousness

is recognized only after a failure of communication, and our first movement is

to believe in an undivided being between us.…”

As he read Geryon could feel something like tons of black magma boiling up

from the deeper regions of him.

He moved his eyes back to the beginning of the page and started again.

“To deny the existence of red

is to deny the existence of mystery. The soul which does so will one day go mad”

-

Margin of silence, Kay sage, 1942 / Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, tr. Richard Zenith / Frank o’hara, “Mayakovsky”, Meditations in an emergency / “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” dir. Céline Sciamma / I saw three cities, Kay sage, 1944 / Pessoa, id. / Richard Siken, “Birds hover the trampled field”, War of the Foxes / The fourteen daggers, Kay Sage, 1942 / Pessoa, id. / Roland Barthes, The Neutral, tr. Rosalind E. Krauss and Denis Hollier / Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red

#web weaving#parallels#I am aware that this is insane behaviour and entirely too much for a wednesday but maybe drop kicking this into the ether will be cathartic#barthes' neutral is about love I'll take no questions#throwing some kay sage in there because this is my house and also she has big Pessoa energy#poetry#Anne Carson#Richard siken#Fernando pessoa#Not too fast let's not go to fast it's beautiful it's free it's human#and I'm expected to go on as usual????????#mine

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

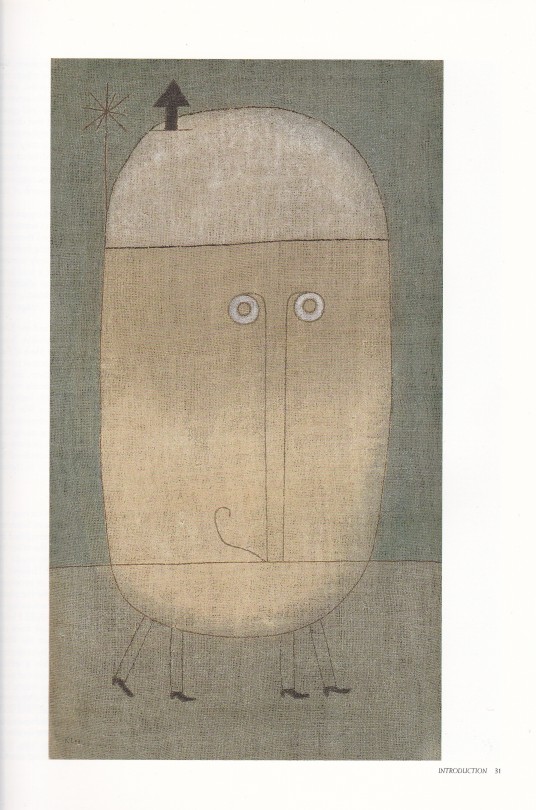

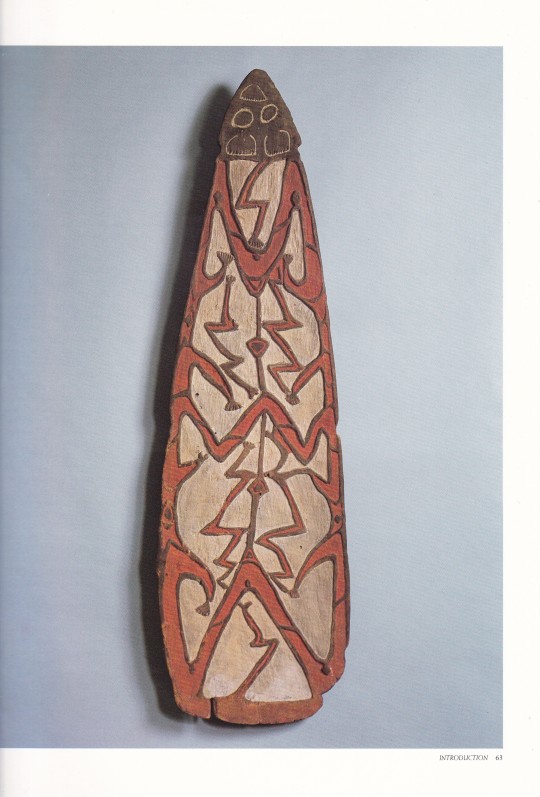

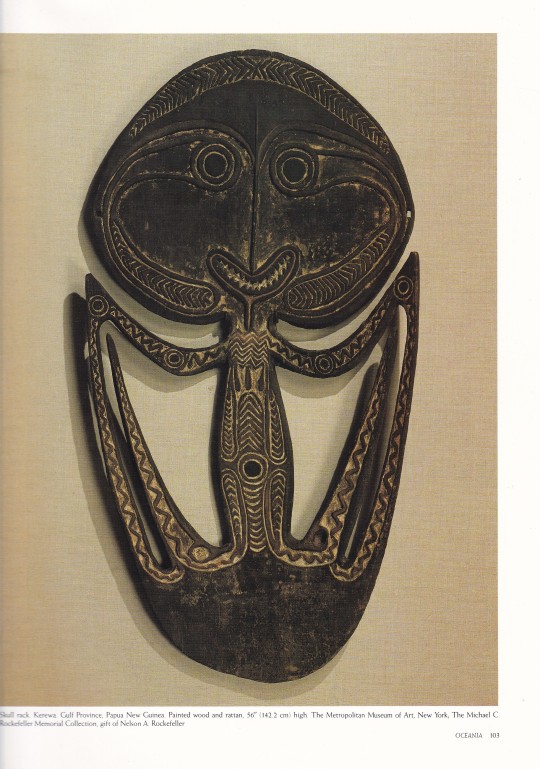

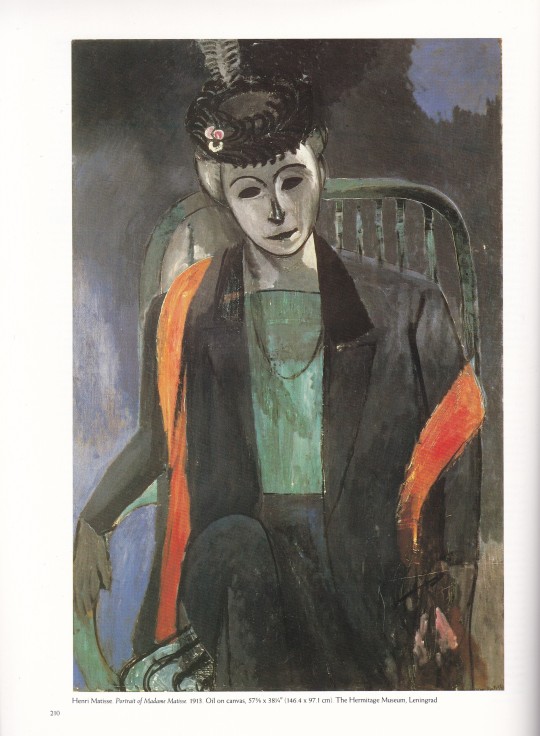

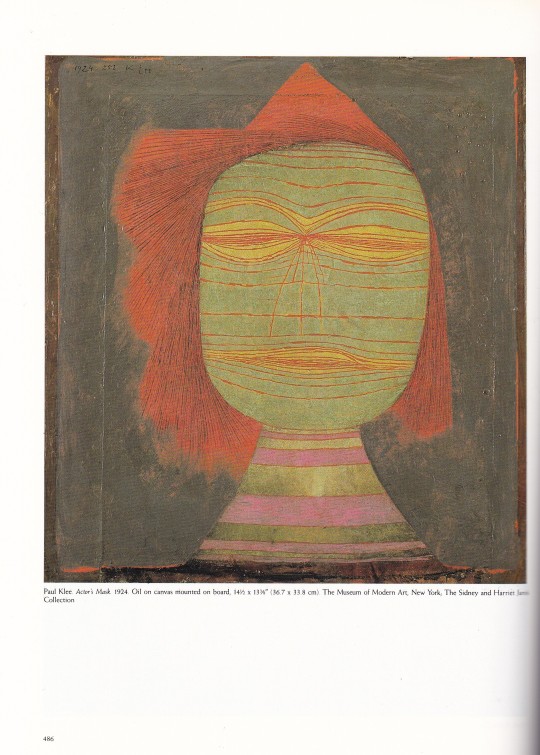

“Primitivism” in 20th Century Art

Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern

Foreword by Richard E. Oldenburg; prefaces by William Rubin and Kirk Varnedoe

Essays by renowned art historians and scholars including Kirk Varnedoe, William Rubin, Rosalind Krauss, Christian F. Feest, Philippe Peltier, Jean-Louis Paudrat, Jack D. Flam, Sidney Geist, Donald E. Gordon, Ezio Bassani, Alan G. Wilkinson, Gail Levin, Laura Rosenstock, Jean Laude, and Evan Maurer.

The Museum of Modern Art in conjuction with the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Dallas Museum of Art , New York 1984, 2 volumes, 706 pages,hardcover ISBN 978-0870705182

euro 120,00

email if you want to buy [email protected]

'In 1906 tribal sculpture was ''discovered'' by 20th century artists; these objects had suddenly become relevant because of changes in the nature of modern art itself. These two volumes comprise the first comprehensive scholarly treatment in half a century of the crucial influence of the tribal arts--particularly those of Africa and Oceania--on modern painters and sculptors. In this visually stunning and intellectually provocative work, 19 essays confront complex aesthetic, art-historical, and sociological problems posed by this dramatic chapter in the history of modern art. The main body of the book contains a series of essays on primitivism in the works of #Gauguin, the #Fauves, #Picasso, #Brancusi, the German Expressionists, #Lipchitz, #Modigliani, #Klee, #Giacometti, #Moore, the #Surrealists, and the Abstract Expressionists. It concludes with a discussion of primitivist contemporary artists, including those involved in earthworks, shamanism, and ritual-inspired performances.'

27/08/20

orders to: [email protected]

ordini a: [email protected]

twitter:@fashionbooksmi

instagram: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano tumblr: fashionbooksmilano, designbooksmilano

#Primitivism#20thCenturyArt#tribal&modern#artexhibitioncatalogue#MuseumofModernArt#fashionbooksmilano

3 notes

·

View notes