#ruden art

Text

I'm on fire this week, doing so much progress in a lot of things :D

Anyways, them <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 <3

#desert duo fanart#grian fanart#gtwscar fanart#goodtimeswithscar fanart#secret life fanart#gtwscar#goodtimeswithscar#grian#desert duo#secret life#desertduo#ruden art

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

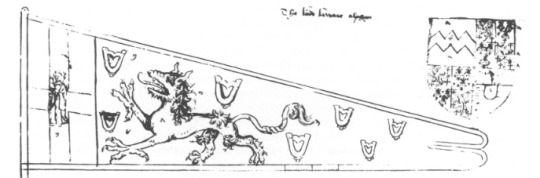

BESTIARIUM: Alphyn

THE ALPHYN IS A RARE LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY BEAST, appearing on a heraldic badge in the Lords de la Warr, on a gideon held by a knight in the Millefleur tapestry, and briefly in the Book of Standards.

Fig I. A depiction of the Alphyn fom the Book of Standards. The alphyn appears in the centre of the triangular standard with its upper paw ready to strike. Its teeth are bared and the alphyn’s long tongue curls upwards. On the upper right, a heraldic shield is shown.

Alphyns possesses a thick man and tufts of fur, appearing akin to the heraldic tyger. They have long ears, tongues, and a tail—knotted in the middle, much like celtic art. Sometimes the alphyn bears the foreclaws of an eagle, cloven hooves, or the pawed feet of a lion.

Fig II. A depiction of an alphyn with its first front talon raised. The alphyn stares to the front with a scowl with its tongue curved upwards. Similarly, the alphyn’s tail curves in an S shape. From Wikimedia Commons.

To further understand the heraldic alphyn, it is best to look at the heraldic tiger. Unlike the very real tiger, the heraldic tyger is a fanged wolf-like speckled beast said to be from “Hyrcania” in Persia. They have the long tufted main and tail of a lion, with a pointed snout. Tygers are famed for their speed and vanity—one such story stating the following:

“Some report that whose who rob the tyger of her young, use a policy to detainne their damme from the following them by casting sundry looking-glasses in the way, whereat she useth to long gaze, whether it be to behold her own beauty or, because she seeth one of her young ones; and so they escape the swiftness of her pursuit.”

Display of Heraldry, Guillim

Hyrcania is not a place in modern Persia, rather being a historical region located south-east of the Caspian Sea in modern-day Iran and Turkmenistan. It was a province of the Median empire. The region was famously associated with tigers in Latin Literature, as cited by this line in the Aeneid:

“Although her back was turned, she still surveyed

The speaker blankly and distractedly

Over her shoulder, then broke out in fury,

“Traitor—there is no goddess in your family,

No Dardanus. The sharp-rocked Caucasus

Gave birth to you, Hyrcanian tigers nursed you.

Why pretend now? Is something worse in store?

Was there a sigh for tears of mine? A glance?”

Did he give in to tears himself, or pity?

Injustice overwhelms me—which concerns

Great Juno and our father, Saturn’s son.”

Aeneid, trans. Sarah Ruden

Medieval scholars, drawing heavily from Greek and Roman texts, attributed their tyger to Persia—which is not uncommon for medieval sources, knowing their misinformed (and sometimes orientalist) nature. Hyrcania also means “wolf-land”, which is likely why the tyger appears more in line with the heraldic wolf instead of a real tiger.

Hyrcania’s tyger is also used as an insult in the medieval and following renaissance period. In Henry VI Part III, Shakespeare uses the hyrcanian tiger as a symbol of ferocity:

The hungry cannibals would not have touched,

Would not have stained with blood:

But you are more inhuman, more inexorable,

O, ten times more, than tigers of Hyrcania.

See, ruthless queen, a hapless father's tears:

This cloth thou dip'dst in blood of my sweet boy,

And I with tears do wash the blood away.

The Third Part of Henry VI, Cambridge University

Considering the Alphyn’s clear likeness to the tyger, we may be able to understand the Alphyn in kinship to the tyger. The eagle and the lion are both representations of noble action and the upper class, so it may be easy to assume that the Alphyn is a noble medieval spirit.

BETWEEN ALPHYAN AND ENFIELD

Almost rarer in heraldic sources than the alphyn, the enfield is an irish heraldic beast originating from the Gaelic onchú “water-dog”. The enfield is described as bearing the head of a fox, chest of a greyhound, front talons of an eagle, the body and hindlegs of a lion, and the tail of a wolf. In this eccentricity, the enfield appears in three contexts:

As the coat of arms of London Borough of Enfield

On the passant sable supporting with the fleur-de-lys on the arms granted to William Marion Mann and his son in June 1964 by the College of Arms in London, along with the heraldic bear as the crest

Armorial bearings of the Irish O’Kelley as the crest upon the helmet, usually in the passant.

It is thought the enfield was the heraldic crest and symbol of the O’Kelley, with a mythological explanation for why the family possessed the enfield symbol:

There is a tradition among the O'Kellys of Hy-Many, that they have borne as their crest an enfield, since the time of this Tadhg Mor, from a belief that this fabulous animal issued from the sea at the battle of Clontarf, to protect the body of O'Kelly from the Danes, till rescued by his followers

(O'Donovan 1843, 99).

However, heraldry did not become common or accepted among gaelic families until the Norman conquest—suggesting that the enfield was rather a tribal than heraldic symbol in origin. The onchú is an irish mythical beast connected to water and as such the enfield arose from the sea, connecting the heraldic spirit to the seas:

The onchu, then, is a fierce animal of the dog tribe, on occasion water-dwelling, that sometimes involves itself in human conflicts. It was so often used as a device on the Gaelic battle-standard, that the term onchu actually became applied to the standard itself. It is a priori highly likely that the onchti and the enfield are one and the same.

Of Beasts and Banners the Origin of the Heraldic Enfield

The alphyn and the enfield are intertwined from the source, as the alphyn likely arose from the enfield—unlike most heraldic beasts, the alphyn does not appear in any medieval bestiaries. Through Irish officers of arms the alphyn possibly came into English thought, forever connecting the alphyn to the Irish enfield/onchú.

ALPHYN, NOBLE

In my deepest experience, the Alphyn is a very noble beast. My alphyn—for I invited one to dwell within my home—is a very affectionate, noble spirit. With the nobility of the heraldic lion, the alphyn stands out as a medieval beast. My alphyn dwells as an affectionate protector of my home and dear grimoire, standing as a rampart lion would upon a crest.

CONCLUSION

The Alphyn is a rather unique heraldic beast and medieval spirit. From its sudden appearance and connection to the Irish enfield, there is much to explore in terms of working with an alphyn. Whether as the protective lion, a swift tyger-like beast, or an animal ready to strike, the alphyn is a wonderful friend in my witchcraft. Standing firm, the alphyn watches on—ready to strike, whether as rampart or passent.

Alphyn, blood on roses,

Curled in your tuff paw,

Arise, noble alphyn,

Come into my bathe.

Alphyn, gaze upon

Your to mine splendor

Bibliography

Friar, S. (1987). A Dictionary of Heraldry. New York : Harmony Books.

Krisak, L. (2009). The Aeneid. Translated by Sarah Ruden. Pp. 320. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. Hb. £18.50. Translation and Literature, 18(1), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.3366/e096813610800040x

Shakespeare, W. (2019). The Third Part Of King Henry Vi. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA45317116

Williams, N. J. A. (1989). Of Beasts and Banners the Origin of the Heraldic Enfield. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 119, 62–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25508971

0 notes

Text

Not that I want to get involved in the “Vergil Bee Discourse,” but it did get me thinking…why merely associate Vergil with bees when you could associate Queen Dido with bees, as her city (Carthage) is the one he describes with the allegory of a hive…especially since she is a queen, just like matriarch of a beehive.

Either way, I couldn’t resist and had to draw a monumental Dido tending to her hive city.

—

Iura magistratusque legunt sanctumque senatum;

hic portus alii effodiunt; hic alta theatris

fundamenta locant alii, immanisque columnas

rupibus excidunt, scaenis decora alta futuris.

Qualis apes aestate nova per florea rura

exercet sub sole labor, cum gentis adultos

educunt fetus, aut cum liquentia mella

stipant et dulci distendunt nectare cellas,

aut onera accipiunt venientum, aut agmine facto

ignavom fucos pecus a praesepibus arcent:

fervet opus, redolentque thymo fragrantia mella.

“O fortunati, quorum iam moenia surgunt!”

Aeneas ait, et fastigia suspicit urbis.

Infert se saeptus nebula, mirabile dictu,

per medios, miscetque viris, neque cernitur ulli.

Lucus in urbe fuit media, laetissimus umbra,

quo primum iactati undis et turbine Poeni

effodere loco signum, quod regia Iuno

monstrarat, caput acris equi; sic nam fore bello

egregiam et facilem victu per saecula gentem.

Hic templum Iunoni ingens Sidonia Dido

condebat, donis opulentum et numine divae,

aerea cui gradibus surgebant limina, nexaeque

aere trabes, foribus cardo stridebat aenis.

Hoc primum in luco nova res oblata timorem

leniit, hic primum Aeneas sperare salutem

ausus, et adflictis melius confidere rebus.

— P. Virgilius Maro “Aeneid” Lib. I, 426–452

—

Laws, offices, a sacred senate formed.

A port was being dug, the high foundations

Of a theater laid, great columns carved from cliffs

To ornament the stage that would be built there:

Like bees in spring across the blossoming land,

Busy beneath the sun, leading their offspring,

Full grown now, from the hive, or loading cells

Until they swell with honey and sweet nectar,

Or taking shipments in, or lining up

To guard the fodder from the lazy drones;

The teeming work breathes thyme and fragrant honey

“What luck they have—their walls grow high already!”

Aeneas cried, his eyes on those great roofs.

Still covered by the cloud—a miracle—

He went in through the crowds, and no one saw him.

Deep in the city is the verdant shade

Where the Phoenicians, tired from stony waves,

Dug up the sign that Juno said would be there:

A horses’s head, foretelling martial glory

And easy livelihood through future ages.

Dido was building Juno a vast shrine here

Filled with rich offerings and holy power.

The stairs soared to a threshold made of bronze;

Bronze joined the beams; the doors had shrill bronze henges.

Here a strange sight relieved Aeneas’ fear

For the first time, and lured him into hope

Of better things to follow all his torments.

“Aeneid,” Book 1, lines 426–452, Translated by Sarah Ruden, 2008

#Queen Dido#Carthage#tagamemnon#aeneidposting#Aeneid#vergil#aeneid book 1#Aeneas#p virgilius maro#Rome#classical studies#rome#ancient mediterranean#classics#my art#Not my translation#Sarah ruden#Poetry#hexameter#Iambic pentameter#epic#epic poetry#bees#beehive#dido#elissa#phoenicia#punic

121 notes

·

View notes

Photo

pixelart is evidently a very good medium for animation

#art#digital art#tw horror#tw body horror#tw gore#tw eye gore#tw eyes#animation#oc animation#oc art#ruden has so much fukin lore#a creepy eye demon decided to fuck up her life basically#original character#original art#digital animation#pixel art

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

More OC’s of mine! (Welp me and my friend’s)

Say hello to Tentaclutz the Water Dragon and Ruden Foxx the Folf. One of the happiest couples you’ll ever meet 😊

And along with them meet their beautiful (already born) children~ Nick the main Folf Hybrid and Ruben the main Dragon Hybrid. Tha happy family of four~ (and pretty soon 7 >w>)

Don’t worry, I’ll post some more art of them ;3

Note that also some of this art is kinda old so there’s probably better quality art of them -_-

#art#digital art#my art owo#furry#my oc art#my oc character#furry oc#furrydrawing#muscle furry#dragon#folf#furry couple#hybrid#hybrid species#furry offspring#pups#furry ship#furry community#@Ruden Foxx

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Icon of the Mother of God of Rudens

Commemorated on October 12

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Holy Seducer

Ceramic: Raku technique / FE oxide / CU oxide

2017 / Ogre / Latvia

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Here's my contribution for the Alethrion Art Challenge for November with the Demigod Bird Ruden.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A New King

A homily on Mark 11:1-11; 15:1-19,

preached at Trinity Cathedral, Pittsburgh,

on Palm Sunday 2021

I would speak to you in the Name of God, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, Amen.

When I say the word king, what comes to your mind? Maybe you picture one of the old English monarchs living in a castle and going to war with his enemies. It could be that you picture a modern dictator, draped in military medals, who quashes dissent and imprisons his political enemies. Or maybe you think of a head-of-state like the U.S. president, arriving by heavily armored motorcade for his inauguration the Capitol. Whatever the case, and whatever political views you have, you probably think of things like pomp and prestige and — most of all — power when you think about a king.

When people in Jesus’ day thought of kings, they might have thought of someone like Alexander the Great, the famous general who conquered the ancient world and paved the way for the Roman Empire. We have a description of Alexander from a historian who lived around the same time as Jesus (or in the same century anyway). He describes how Alexander besieged Babylon and then, when the conquered ruler had surrendered, rode into the city:

A large number of the Babylonians had taken up a position on the walls, eager to have a view of their new king, but most went out to meet him… [One Babylonian leader] had carpeted the whole road with flowers and garlands and set up at intervals on both sides silver altars heaped not just with frankincense but with all manner of perfumes.

Then, the historian tells us, Alexander “entered the city on a chariot and went into the palace. The next day he made an inspection of Darius’ furniture and all his treasure.”

Does that sound familiar? Alexander, the new king of Babylon, rides into the city on a road that’s been strewn with greenery. A huge throng of people are greeting him and acclaiming his victory. And when he arrives, he starts to look around at everything, acting as if he owns it all now because of course he does.

But other people in Jesus’ day, Jewish people, might not have thought first about Alexander the Great when they thought about kings. Instead, they might have remembered the words of an ancient oracle from the Hebrew prophet Zechariah:

Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion!

Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem!

Lo, your king comes to you;

triumphant and victorious is he,

humble and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

Either way, on that day when Jesus sat on a donkey and rode into Jerusalem on a path strewn with cloaks and palm branches, everyone would have recognized that Jesus was acting like a king — He was stepping into the role and performing the script perfectly. As N. T. Wright, the former Bishop of Durham, has written, “Within his own time and culture, [Jesus’] riding on a donkey over the Mount of Olives, across Kidron, and up to the Temple mount spoke more powerfully than words could have done of a royal claim.” And the crowds who are waving their palm leaves and shouting “Hosanna!” get the message. As Wright says, “they praise their god for the arrival, at last, of the true king.”

But what kind of king is Jesus? How does He assert His kingship? How does He show His royalty?

The short answer is: in the most devastating, hope-dashing, grief-inducing way possible.

For His royal welcome into the city of the great Israelite king David, He is arrested and brought to trial.

For His first kingly speech to the Roman Empire’s governor, He doesn’t say anything more than a sentence. Pilate, the governor, asks Him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” And Jesus says simply, “You say so.”

For a first glimpse at His political platform, we witness a scene where Jesus, who called Himself “son” and addressed God as Abba, is standing side by side with a violent insurrectionist who goes by the name “son of Abbas [=son of a father],” or Barabbas. Here, the implication seems to be, we have two antithetical characters and two antithetical agendas: One son of Abbas believes in grabbing swords and spears and storming the gates; the other son of Abba has already told His followers not to carry any swords and to offer the other cheek when someone slaps them in the face.

For His coronation, He stands in the middle of hundreds of Roman soldiers. They place a royal purple robe on Him. They twist together branches from a thorn bush and press them down on His head for a crown. Then they kneel down in homage and, for accolades for the new king, they hurl wads of spit in His face and beat the thorns deeper into His scalp with rods.

For the public heralding of His kingship, they hoist Him up high on two stakes. They strip off all His clothes so everyone can see His ribcage shudder as He struggles to breathe. They put nails through His wrists and feet to hold Him in place on the stakes. And then they fix a sign over His head so that all the jeering onlookers can know that this is all a parody. The sign says that this man is “The King of the Jews.”

What kind of kingship is this?

It’s a kingship of self-surrender rather than conventional force.

It’s a kingship of silence rather than propaganda.

It’s a kingship of acquiescence rather than violence and coercion.

It’s a kingship of humiliation rather than glory and honor.

And it is a kingship that culminates in death rather than longevity and prosperity.

Why, then, do we remember it at all? History records the kingship of victors and tyrants; those who lose and abdicate power are, by definition, not kings. So why does history remember this emasculated and disgraced “king”? Why are we here this morning in such a grand, ornate place to remember and adore a would-be king who was strung up to suffer six hours of excruciating torture after which He finally died in godforsaken agony?

Because this is the kingship God has chosen for Himself — the kingship by which He rescues the world. Next Sunday we will celebrate the day God set His seal of approval on this king, announcing to us and to all the world that this is His anointed One, His representative — His Son.

Which means, among other things, that from now on, if we want to know what true and triumphant and lasting and divine kingship looks like, we should look at the suffering Figure hanging there on the stakes.

Before He died, Jesus told His followers how He intended to redefine kingship: “[T]he son of mankind didn’t come to have attendants but to be an attendant, and to give his life as the price to set a lot of other people free” (trans. Sarah Ruden). Jesus has shown us what it means for God to be king through His giving up His life for us out of love.

So, on this Palm Sunday, as we prepare to keep vigil with Jesus this Holy Week, we sing in trust and hope and praise,

All glory, laud, and honor

to thee, Redeemer, King,

to whom the lips of children

made sweet hosannas ring.

Thou art the King of Israel

thou David’s royal Son,

who in the Lord’s name comest,

the King and Blessed One.

To Him be the glory for ever and ever. Amen.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since there's some nice people, who got to work, I post this :)

Enjoy everybody! I need to draw more :/

@kairamuwu @skimmeh

#goodtimeswithscar fanart#gtwscar fanart#stareater au#goodtimeswithscar#gtwscar#ruden art#let me know if there's a stareater fanart tag :)

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

That Eidolon Women Who Translate article is going around & I think it needs a much more critical reading than it's been getting. First off, I'm going to say that she's of course right that Classics as a field still has misogyny problems. I just don't agree that the way the new translations by women have been treated have much to do with that.

The first example Myers discusses in detail is Anne Carson's Electra, in contrast with Hanna Roisman's. I haven't read Roisman's, but both Myers and the reviewer say that her text is more like Sophocles', and I've said, in basically the same words, this next paragraph:

Steinmeyer explained that perhaps the “dilemma” of Carson’s translation of Electra “could be resolved simply by labeling Carson’s text a re-creation or ‘inspired by’ instead of a translation of Sophocles.”

Carson's project is rebracketing and rewriting the ancient works; she doesn't claim to be attempting a close translation. Saying that, therefore, isn't a misogynist attack on a creator -- it's merely acknowledging that it's a work with a different purpose. And there are male authors who do this -- Christopher Logue's War Music, for example, is a "version" of the Iliad, and is treated as such by reviewers. And this line is just silly: "Carson had managed to compromise Sophocles’ text while simultaneously expanding it in the translation." An expansion by a translator is a contamination -- translation, by nature, is interpretation, and explaining something or expanding it is another step down the primrose path of the interpreter.

Moving on, reading the beginning of Garry Wills' review of Ruden's Aeneid, Wills is, as far as I can tell, more positive about Ruden than he is about Fagles, and more positive about Vergil than about either, which is right.

Ceaselessly calling out Creusa’s name.

She does not have room in that last line for the echo-effects Vergil creates:

Nequiquam-ingeminans iterumque-iterumque vocavi.

But Fagles, with greater room for maneuver, cannot equal the original either:

“Creusa!” Nothing, no reply, and again “Creusa!”

Myers quotes Wilson as positioning "the translation as 'secondary to that of the male-authored original,'" as though that's a problem -- translation is an art, but it's a secondary art, the way criticism is, and part of the difficulty of translation is that it's like describing a painting to someone who can't see it. You have to make compromises to get the power of a work into a different form. And more, you have to subordinate your own taste to the words the author wrote. If I were translating the Aeneid, I'd love to change Vergil's tic of using a very prosaic word after a lofty flight of verse, because I feel it rarely works. But it wouldn't be faithful if I did that, because I'm not writing, I'm conveying someone else's writing to people.

So when Wills praises Ruden for approximating Vergil in less space that Fagles, who, again, "cannot equal the original," he's saying that her choice of meter might have made it slightly harder for her -- and that she, by and large, succeeds.

Further, Eleanor Johnson's review does seem to have problems -- "she lumped Wilson’s Odyssey, Pat Barker’s Silence of the Girls, and Madeline Miller’s Circe together and referred to them as 'Homeric adaptations,'" which is definitely unfair to Wilson, and “piratic feminist manifestos" isn't a great phrase, but Myers also says

“Because Wilson’s Odyssey really is Wilson’s odyssey,” and the “poem is not just a rendering of the Odyssey, but a reading— her reading — of the Odyssey.” In other words, for Johnson, the translation contained too much Emily Wilson, and not enough Homer.

and I think that's a very valid critique. Really, any time we talk about a major poet's translation, we talk about their voice and how it influences the work they're translating & how much of their style comes through -- "too much of X" is a commonplace. And for reading in class, that's important, because students often make arguments based on word choices in translations. Which leads into her next point:

The names of famous translators of classical texts often become part of the scholastic lexicon: as an undergraduate, I was instructed to read “the Fitzgerald Odyssey” and “Fagles’ Iliad.” Referring to the translations in this way equates the translator and the author.

Her last line is simply wrong. Referring to the translations in this way separates the translator and the author; it emphasizes the role of the translator and alerts you that you're not reading Homer. (Further, especially in the age of Project Gutenberg and Perseus, if you tell a college class to "read the Iliad," at least some of them will end up with the first search result, Samuel Butler's 1898 prose version, which isn't terrible or anything, but is very 1898. If the class is reading a translation, you want them all to read the same translation; saying "get Fagles' Iliad" is an easy way of doing that.) And both Fitzgerald and Fagles are very distinctive as translators, and people have remarked on that, not always positively.

To pivot away from direct commentary on the article, it's frustrating because Myers has collected a lot of very diverse reviews of translations, many of them more positive than anything, and cited all of them as indicative of problems with how we talk about women's work. Is there a way to criticize Wilson's Odyssey that she would find acceptable? The source aside (a conservative magazine), this comment seems fine: "He [John Byron Kuhner] echoed Johnson when he said that Wilson makes 'all the judgements' about the text on behalf of her readers, 'eliminating ambiguity wherever she sees fit'" -- which shouldn't be the role of the translator.

And I haven't read Wilson's Odyssey in total, I admit, but I've read her talking about it and I've read the beginning, and I disagree with a lot of her choices (I've complained at length about "complicated" for "polutropos" & I'm not going to rehash it, but I think it's simply wrong) -- for one thing, there are ancient authors for whom colloquial language makes sense (Catullus, for one, or Aristophanes), but Homer just isn't one of them, because Homeric Greek is a constructed literary language that would never have been the same as the language you were speaking around the campfire. Is this a valid critique, or am I being misogynistic?

Lastly, male translators' biases should be investigated more -- the place in the Odyssey where Fitzgerald translates "those women" as "sluts," for example. But we have been talking about that. If women are going to be taken seriously as academics, we have to be acceptable targets of reasonable critiques of our work and not deflect them by talking about gender -- because most of the (honestly fairly mild) criticisms of the translation that Myers quotes are reasonable, and many of them do not engage at all with the translator's identity.

#tl;dr#in the extreme#the once (and probably not future) field#traduttore traditore#my thoughts on...

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

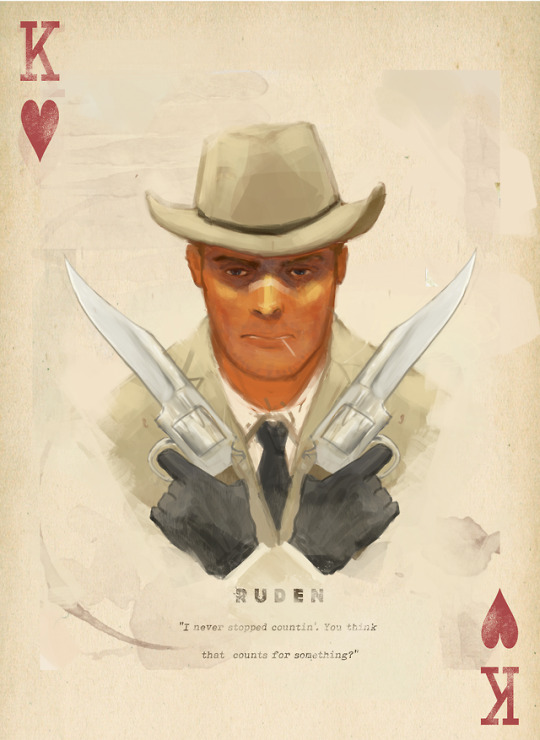

Ruden Alplaw(Cowboy) Playing Card.

Based the concept off of the Fallout New Vegas playing cards. I think this makes two “finished” Proctor portraits. Maybe I’ll do a whole series, would be a nice goal to finish. Feeling good about what I can accomplish this year with my art.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

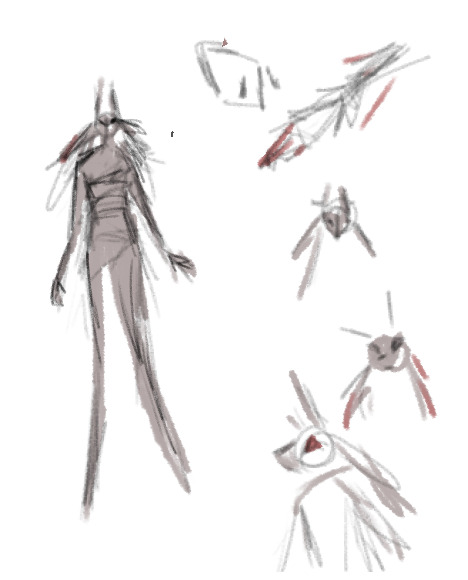

concept art of ruden

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

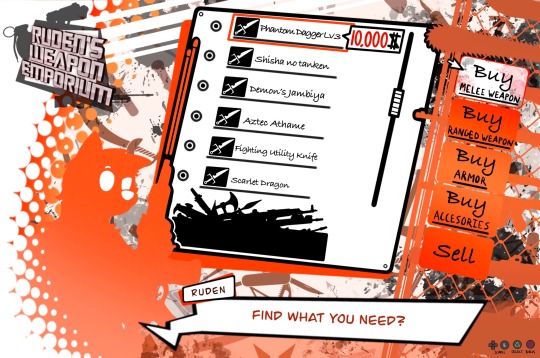

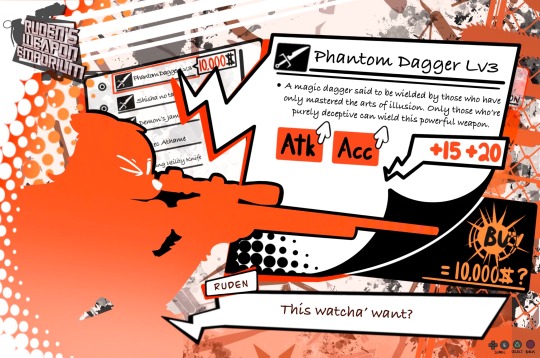

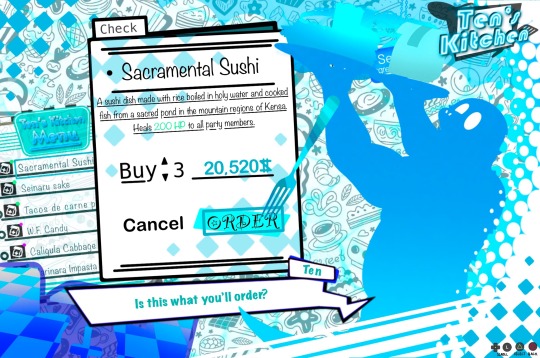

Working on some in-game shop menus! :3

As some of you know I’m trying to create a clear plot line and most of the art for a future video game project, and I’ve already got my fancy shmancy shop menus down!

Need some new equipment? Click away to Ruden’s Weapon Emporium! Need healing or revitalizing items? Click away to Ten’s Kitchen!

#digital art#art#my art owo#furry#possible video game#video games#video game project#upcoming game#work in progress#work in project#in game art#game art#shop

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Click for a closer look!

Here’s the four stooges that make up The Badlands Company so far, a merc group for all your dirty deeds done right for the right price.

From left to right: Collin O’Toole the technopath ( @2-weenies character), Bob the tiny strongman, Arkham Dnieprivich the Slavic scientist/kompot extraordinaire (also @2-weenies character), and Desmond Von Ruden a black german vampire whose as fugly as he is skilled in hand-to-hand combat.

And yes they’re all squatting and wearing Adidas tracksuits, this is what they do on their downtime.

2 notes

·

View notes