#sjedit

Text

#SuperJuniorEdit#SJEdit#Super Junior#SM Town#Leeteuk#Heechul#Yesung#Shindong#Eunhyuk#Donghae#Siwon#Ryeowook#Kyuhyun#Choi Siwon#Lee Donghae

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jebla me ona anketa za praznovjerja sta ju napravise uopce, reko budu samo mutuals glasali hihi haha hoho, 30 000+ GLASOVA IMA??? znate kolko glupih amera sad imam u svom dvoristu (tumblr notes), cu da se objesim

#boli me duoe sta nikad niste culi da ak sjedite na cosku stola se necete zenit#da bog da vam drzava eksplodirala#<- zali se na gluposz i svjestan je toga#al kolko poruka 'OP tvoja mama je ovo izmisljala' sam dobio doslovno stavize mi metak u celo#i onda stave ono machbeth praznovjerje pardon sta nisam theater kid GO AWAY#dosl dodam other opciju oni i dalje preglupi da ne dodaku svoj strucan komentar

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isprike svim ljudima koji su ikad morali sjedit kraj mene u školi i vidjet me kak pišem jako užasan fanfiction 👍🏼

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

hej ti. da, ti... vidim te.

vidim te i čujem te. ne moraš više sjedit i čamit u kutu i molit me da te doživim, čujem i poslušam. sad sve radim kako želiš. drago mi je da smo napokon došle na ti.

drago mi je da se upoznajemo jer živimo cijeli život zajedno, a nismo imale priliku da se upoznamo kako treba i do kraja.

nadam se da si malo zadovoljnija nego što si bila svih ovih godina. žao mi je što te nisam slušala, bila si u pravu u vezi svega i svakoga do sada. žao mi je što nisam imala snage poslušat te. teško mi je to bilo za prihvatit. znaš i sama da nam prihvaćanje baš i nije išlo tijekom života... prihvaćanje sebe, drugih, situacija, mišljenja, ponašanja.

hvala ti što si mi pokazala koliko ljubavi imam za dati i što ljubav nije toliko strašna. bolna je, ali nije strašna.

hvala ti što si mi pokazala koliko si snažna i uzemljena kad se sve u tebi i oko tebe ruši i raspada.

hvala ti što puštaš da stvari idu svojim tokom jer prihvaćaš što ne trebaš imati kontrolu nad svime što se događa. neke stvari je bolje pustiti koje nisu u našoj moći.

hvala ti što dišeš, vidiš, čuješ i duboko osjećaš i ne stidiš se više toga.

i hvala ti što si odlučila živjeti.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

hladne noćne postelje

ako ne mogu gledati tebe

čekat ću umiranje dana

i sjedit ću pod mjesečinom

u satima koji zahtijevaju moje snove

o sjedeći u tišinama noći

gledat ću sasvim nepoznato nebo

nebo koje mene odavno razumije

nebo koje je i tvoje isto

dok gledam mjesec

kako hoda preko obzora

ja ću znati da ti isti pohod gledaš

da ti oči traže ono što moje izbjegavaju

možda kada bi zrake mjeseca

miris tebe mogle donijeti meni

možda bih tada mogla leći

u svoje hladne ponoćne postelje

6. srpnja 2023.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

vi sta idete na docek sutra ste zli jer ja moram sjedit i pisat seminar i bit jadna .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Krema za vanjske hemoroide: pronađite olakšanje uz Electu

Liječenje vanjskih hemoroida može biti i neugodno i uznemirujuće. Ove natečene vene oko analnog područja mogu uzrokovati bol, svrbež i iritaciju, utječući na vašu svakodnevnu udobnost i kvalitetu života. Ako tražite učinkovito rješenje, nemojte tražiti dalje od Electine specijalizirane vanjski hemoroidi krema . U ovom blogu istražit ćemo prednosti korištenja kreme za vanjske hemoroide i kako vam Electini proizvodi mogu pomoći da pronađete olakšanje.

Razumijevanje vanjskih hemoroida

Vanjski hemoroidi su proširene vene koje se pojavljuju oko vanjskog dijela anusa. Mogu biti uzrokovani čimbenicima poput naprezanja tijekom pražnjenja crijeva, dugotrajnog sjedenja, trudnoće ili sjedilačkog načina života. Simptomi obično uključuju:

• Bol ili nelagoda: Vanjski hemoroidi mogu biti prilično bolni, posebno kada sjedite ili tijekom pražnjenja crijeva.

• Svrbež i iritacija: Zahvaćeno područje može postati svrbež i nadraženo, što dovodi do značajne nelagode.

• Oticanje i upala: Vene oko anusa mogu nateći, uzrokujući primjetna izbočenja i upalu.

Zašto koristiti kremu za vanjske hemoroide?

Krema za vanjske hemoroide osmišljena je za ciljano ublažavanje simptoma povezanih s hemoroidima. Evo zašto korištenje specijalizirane kreme može biti korisno:

1. Umirujuće olakšanje: Visokokvalitetna krema za hemoroide može pružiti trenutačno umirujuće olakšanje od boli i svrbeža. Sastojci kao što su hamamelis, aloe vera i hidrokortizon pomažu smiriti upalu i smanjiti nelagodu.

2. Pospješuje zacjeljivanje: Mnoge kreme sadrže sastojke koji potiču zacjeljivanje oštećenih tkiva. To može ubrzati oporavak i smanjiti ozbiljnost simptoma tijekom vremena.

3. Smanjuje oticanje: Kreme za vanjske hemoroide često sadrže protuupalna sredstva koja pomažu smanjiti oticanje i ublažavaju pritisak oko zahvaćenog područja.

4. Poboljšava udobnost: Nanošenje kreme može pružiti zaštitnu barijeru, smanjujući trenje i iritaciju tijekom dnevnih aktivnosti.

Kako Electina krema za vanjske hemoroide može pomoći

U Electi razumijemo potrebu za učinkovitim i umirujućim rješenjima za upravljanje vanjskim hemoroidima. Naša krema za vanjske hemoroide formulirana je s pažljivo odabranim sastojcima za maksimalno olakšanje i udobnost. Evo po čemu se ističe Electina krema:

1. Vrhunski sastojci: Naša krema sadrži mješavinu prirodnih i znanstveno dokazanih sastojaka dizajniranih za rješavanje nelagode povezane s vanjskim hemoroidima. Sastojci poput hamamelisa, nevena i vitamina E odabrani su zbog svojih protuupalnih i ljekovitih svojstava.

2. Nježna, ali učinkovita: Electina krema za vanjske hemoroide dizajnirana je da bude nježna prema osjetljivoj koži, a istodobno pruža snažno olakšanje. Formulacija je izrađena tako da umanji iritaciju i poboljša ukupnu udobnost korisnika.

3. Brzodjelujuće olakšanje: Naša je krema dizajnirana za brzo ublažavanje boli, svrbeža i oteklina, pomažući vam da se vratite svojim svakodnevnim aktivnostima uz minimalnu nelagodu.

4. Jednostavna primjena: Krema se lako nanosi i brzo upija, što ju čini praktičnom za korištenje kao dio dnevne rutine. To omogućuje dosljedno liječenje i trajno olakšanje.

Savjeti za korištenje kreme za vanjske hemoroide

Kako biste postigli najbolje rezultate Electine kreme za vanjske hemoroide, slijedite ove savjete:

1. Očistite područje: Prije nanošenja kreme, provjerite je li zahvaćeno područje čisto i suho kako biste izbjegli daljnju iritaciju.

2. Nanesite prema uputama: Slijedite upute na etiketi proizvoda za učestalost i količinu primjene. Obično se preporučuje nanošenje kreme 2-3 puta dnevno ili nakon pražnjenja crijeva.

3. Održavajte dobru higijenu: Održavajte područje čistim i izbjegavajte korištenje oštrih sapuna ili maramica koje bi mogle pogoršati iritaciju.

4. Ostanite hidrirani i jedite hranu bogatu vlaknima: zdrava prehrana i odgovarajuća hidracija mogu spriječiti zatvor i smanjiti napor tijekom pražnjenja crijeva, što može pomoći u ublažavanju simptoma hemoroida.

Otkrijte udobnost i olakšanje uz Electu

Ako se borite s vanjskim hemoroidima, Electina krema za vanjske hemoroide nudi pouzdano rješenje za učinkovito olakšanje. Naša stručno formulirana krema osmišljena je kako bi ublažila nelagodu, smanjila upalu i pospješila zacjeljivanje, pomažući vam da se vratite ugodnijem i bezbolnijem životu.

Istražite Electin asortiman proizvoda i pronađite olakšanje koje zaslužujete. Prihvatite udobniji i zdraviji način života uz Electinu kremu za vanjske hemoroide već danas. Vaš put do olakšanja počinje ovdje!

0 notes

Text

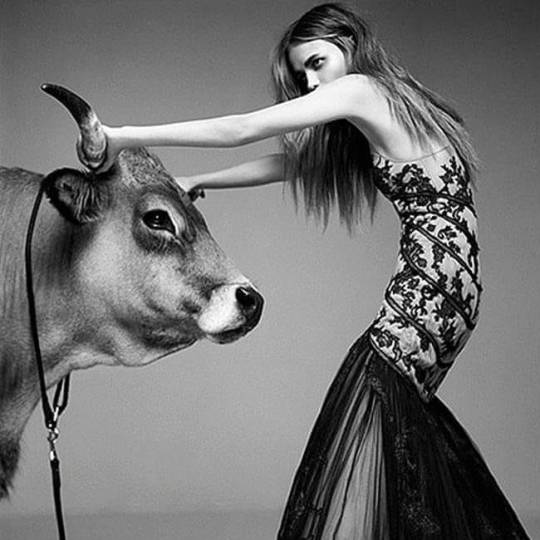

Romana Brolih: IZBACITE BIKA

IZBACITE BIKA

–

Kako je to imati osornost koja neće zacijeliti, radite na sebi, udahnite duboko, ne sjedite prekriženih nogu, psihoterapija, razmaženost, cinizam, sebičnost, malodušnost, traume, ravnodušje, bjegovi, nepoštivanje drugog, zagrlite medvjeda, upoznajte vuka, ne potiskujte tigra. U sebi.

Ne izbjegavajte ljude, vaš partner nije vaš roditelj, reagirajte, ali ne na prvu, nije nitko kriv…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Maratonsko iskustvo

Pročitao sam puno priča o prvom istrčanom maratonu, evo zadnju pred 5 minuta i skoro sve su odlične, inspirirajuće, oda ljudskom duhu, upornosti. Pojedine su epovi kao da stvaraju kult ličnosti, ali svi imamo ovakav ili onakav ego. Kakav god tko bio kao čovjek, tko istrči maraton za mene ima, a mislim i za sve druge, potpuni respekt kao trkača i to je to.

Moja maratonska priča je barem meni mnogo zanimljivija u vrijeme prije utrke, mnogo prije. Na jesen 2020g., već sam pauzirao godinu dana od trčanja. Neću u detalje zašto. Ubili me hemeroidi, al onako da nemoš sjedit života mi. I tako kad je prošlo to peckanje, zaletio se jedan dan do štenare na pivo. Sjede Janko i Žana. I tako nakon 2-3 pive padne ideja na stol da slijedecu subotu (a bilo petak navečer) vodim školicu jer nema trenerice. Nema problema!

Budim se u subotu i shvatim da nisam trčao godinu dana, a vodim grupu. Sad me pecka duša. Obukao sam majicu jedine istrčane utrke do tad, zagrebačkog halfa (di sam dobio spomenute hemeroide), čisto da izgledam ko stari trkač.

Na nasipu me dočekala entuzijastična grupa trkača i trkačica. Spremno sam uvukao trbuh, predstavio se i rekao kako ce i oni za mjesec dana moći istrčati mali krug (nisam time aludirao na sebe jer ja to definitivno nisam mogao). Javi se potom jedan ženski glas - "nama su rekli da za 2 mjeseca". Ok ima prpošnih u grupi.

Završio trening, mislim da smo imali 3-4 kilometra. Ja ne znam kako je njima bilo, al znam da je meni bilo najgore. I ajde sav sretan uspio sam, dovukao sam ih do klupica, nisam se ozlijedio, nisam povratio po nikome. Kad čujem opet isti ženski glas, s dalmatinskim naglaskom -"bilo je brže nego je pisalo". Odgovorim crvenkast u licu: "nitko se drugi nije žalio".

Ta cura bila je Dubravka i odlučio sam posvetit joj više trenerske pažnje u nastavku teksta i života. (cura u crnoj majici)

Slika nastala na tom prvom treningu. Primjetno je moje dobro kondicijsko stanje.

Nastavio sam trčati koliko sam mogao, uslijedilo je još dosta halfova i negdje 2 godine kasnije došao mi je maraton u fokus. I kako je došao, tako su me strefile raznorazne stvari radi kojih nisam dugo mogao imati kontinuitet u treninzima i često sam solo trčao. Bolesti, ozljede, naleti auta. I tako došla zimska baza 2023/2024 prva koju sam uspio odraditi. Mislim da nije bilo treninga u kojem nisam mislio na maraton i tako sam si počeo dodavati kilometre i van zadanog treninga. Tek na jesen sam se pridružio klubu i počeo ozbiljnije trčati i falio mi je taj kontinuitet, ali reko ima vremena, mogu tek na jesen na maraton. Negdje u 2.mjesecu došao mail o Bratislavi. Prilika za maraton. Odluka je pala kao za ona 3 kilometra nakon pive.

Nas par je imalo ideju da odemo autom, pa par dana điramo po gradu i to na žalost nismo napravili, jer grad je fantastičan i definitivno se vraćam u njega. A zamišljao sam ga kao spoj Rumunjske i Svazilanda.

Ali ekskurzija busom, nas 60-tak u busu na kat, hrane na kat i šta možeš više poželit.

Dubravka i ja imali smo od stvari 1 ruksak i 2 torbe. Al znate one torbe koje su više kao ogromne vreće kojima su ljudi nekad na selu nosili bale sijena i koječega. E, u malom ruksaku bila je sva naš odjeća, a tim 50 kilnim vrećama - hrana! I satrali smo sve do Bratislave. Još uvijek imam 5 kila više nego prije tog puta, i to nakon maratona.

Isti dan Dubravka je trčala cenera i bome ga je istrčala. Došla je na cilj sva izubijana jer je pala i potrgala se. Jer je razgledala grad i trčala istovremeno pa nije vidila most. Ona je rekla rupu u zemlji al vidio sam sliku.

Došlo jutro, prognoza 27 stupnjeva taj dan, što je baš "sjajno" kad se spremaš za takvu utrku oko nule čitavo vrijeme. Nalijevam tekućinu čitavo jutro, jer alkohol od sinoć sigurno neće pomoć.

Odlazimo iz hotela, kad nakon 200 metara pitam ja Dubravku "šta ti neće bit hladno, ipak je sad tek 16 stupnjeva". Ona izašla u kratkim rukavima. Ma nije inače nešto zimogrozna, samo kad je vani ta temperatura, a idemo spavat, ona voli obuć flis piđamu, neku lijepu jaknu, vunene čarape, najdeblji poplon koji čuvam za dane kad polarna struja udari u ove krajeve, zadihta prozore, spusti rolete da ne bi ladnog zraka cirkuliralo, pa se onako zamotana zarola u taj poplon ko palačinka. Kad mi kaže "laku noć" čujem to onako u daljini zagušeno kao da govori iz utrobe zemlje.

Zato vidjevši je u kratkim rukavima, uhvatila me nevjerica. I otrči ona po jaknu u hotel. Vratila se nakon tek 20 minuta pa više nisam stigao maknut iz sebe te litre tekućine, nego sam trčao bućkajući se prvu polovicu utrke. A bio mi bed pišat uz stazu jer nisam nikog vidio da to radi. Tek jednog starijeg kasnije kako piša po mostu. I kad sam došao bliže, skužim - Janko!

20 kilometara sam mislio na Dubravku, jaknu i Toj toj. I doslovno samo 2 bila na 20-om kilometru. U prvi uletila neka cura taman prije mene, i kako je ušla tako je isti tren istrčala van. Reko sestro, ne znam šta si našla unutra, al da je i medvjed, it's ok.

Bilo je baš fora kod cilja skrenuti za još jedan krug i odjednom se smanji gužva za 80%. To, osjećam se kao da su svi iza mene!

Tu je vrućina počela radit svoje. Srećom organizacija je bila odlična i spremno sam ulijetao u sve vatrogasne šmrkove koje su bile duž staze. Davali su nam i ful namočene spužve koje sam izlijevao di sam stigao po sebi, samo da si malo spustim temperaturu. Staza je bila predivna, totalno uživanje razgledanja i trčanja. Uživanje je prestalo na 30-om kilometru. Do 35-og sam se držao svog tempa i nisam stajao do tada, ali negdje u to vrijeme sam se prestao znojit i lupila me dehidracija, a noge počele vikat. Od tada bio je red hodanja, red trčanja, samo da se dovučem do cilja. Na 37-om me prestigao moj pacer kojeg sam s tugom ispratio pogledom. Istovremeno, to je bila moja najveća istrčana dužina (36 km na treninzima). Zadnjih 5 km zanemaruješ bol i guraš naprijed i znaš da si uskoro gotov, a ostaje sjećanje za čitav život. Toliko sam često na treninzima zamišljao ulazak u maratonski cilj. Moj je bio malkice drugačiji od zamišljanog. Naime, posljednjih 300 metara je bila uzbrdica, a ja sam tu dao gas, jer neće me valjda vidjet draga kako se vučem do cilja, nego ulazim ko gazela. Posljedica toga je bila da mi je krenulo na riganje, pa kad se Dubravka pred mojim ciljem ubila od mahanja i vikanja, ja sam ju zelen jedva pogledao, prošao kroz cilj, naslonio se na ogradu i pustio dušu i koješta još. Ima i službena slika toga al neću vas mučit. Došao sebi nakon par trenutaka i gledam di su ove s medaljama. Di je moja medalja? Eno ih stoje 100 metara dalje. Krenuo je prema jednoj, ona diže ruke u kojima je moja medalja. Misli si ona, eto sad ce on za par sekundi do mene. Držala ona jadna te ruke u zraku dobrih 2 minute dok sam se ja dovukao do nje.

Dojmovi su neopisivi i vrijedilo je svega, ali nikad više.

6 dana kasnije, registrirao sam se za Atenski maraton. :)

2 tjedna kasnije, bit cu oženjen za ovu što se žalila na početku teksta. Na kraju ispada da sam se ipak morao dokazat da mogu trčat kolko sam rekao na prvom treningu da bi mi se obećala.

Pouka ovog teksta je, samo popijte pivu s Jankom i odite doma.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ja kad ciljano sjednem na kut stola i sva mi se rodbina zgrozi i kaže: nemoj tamo sjedit nećeš se nikada udat

1 note

·

View note

Note

osjetite moju toplinu jer je u mojoj sobi prevruce trenutno,,,,,,,,,,,,,septembar

toplina bi rado bila podjeljena sa Vama, ako je to zelja.

pa otvorite prozore i sjedite kao ja u mrak

možemo skupa,,,,,,,

0 notes

Text

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imate problema s bolovima i tegobama u zglobovima?

Bolove u koljenima, ramenima, leđima i mišićima danas osjeća većina ljudi iz raznih razloga. Ono što smo primijetili je da vape za trenutnim olakšanjem. Predstavljamo vam Cannaxine kremu i roll-on, najnoviji kozmetički preparat s uljem sjemenki konoplje!

Proces izlječenja bolesti kao što je artritis, giht, reuma ili osteoporoza je većinom jako dugačak i mukotrpan, a u sve to vrijeme teško je živjeti s konstantnom boli i probadanjima. Zato je važno da svi imaju neki preparat s kojim si mogu olakšati svakodnevicu.

KADA SE SAVJETUJE KORIŠTENJE CANNAXINE KREMA I ROLL-ONA?

Cannaxine krema i roll-on preporučuje se osobama koje

· Pate od boli i nelagode u koljenima, zglobovima, leđima, ramenima i vratu. Mnogim osobama ta vrsta nelagode otežavala je ili čak onemogućavala normalno kretanje u svakodnevnom životu.

· Osjećaju ukočenosti u ramenima i leđima.

· Cannaxine krema izvrsno je rješenje i kod ozljeda kao što su uganuća, iščašenja i istegnuća koja se događaju kao posljedica pretjeranih napora na radnom mjestu ili prilikom sportskih i rekreativnih aktivnosti.

CANNAXINE KREMA I ROLL-ON FANTASTIČNOG SU SASTAVA!

Cannaxine krema i roll-on u sebi sadrže:

· Ulje sjemenki konoplje - po mnogim iskustvima pokazalo je pozitivno djelovanje na ublažavanje boli uzrokovanu artritisom, zbog svojih vrlo jakih protuupalnih svojstva.

· Mentol - odličan saveznik ulja sjemenki konoplje u borbi protiv nelagoda za gotovo sve organske sustave, posebno na koštano-mišićni. Bolovi u mišićima i zglobovima pogađaju sve dobne skupine, a najčešći su u starijoj populaciji jer starenjem dolazi do slabosti mišića i promjena na hrskavici.

· CBD - djeluje analgetski.

· Ekstrakt korijena vražje kandže - u nekim zemljama službeno koristi za liječenje artritisa i gihta te je prirodna zamjena kortikosteroidima.

· Smola indijskog tamjana - pogodna za smanjivanje upale, smanjuje jutarnju ukočenost i smetnje pri kretanju, intenzitet boli i poboljšava pokretljivost zglobova.

· Kora slatke naranče - pomaže u suzbijanju oticanja tkiva kao posljedice upala.

· Ulje arnike - poznato po svojstvima ublažavanja boli, pomaže kod bolova u mišićima, kod grčeva i reumatskih bolova te ulje limuna koje savršeno zatvara krug ovog fenomenalnog spoja sastojaka svojim antibakterijskim djelovanjem.

· eterično ulje kore limuna

· ekstrakt cvijeta nevena

KAKO SE CANNAXINE KREMA I ROLL-ON NANOSE

Cannaxine krema nanosi se u manjoj količinu na željeno područje te je potrebno kružnim pokretima umasirati dok se krema u potpunosti ne upije. Koristiti prema potrebi, 2 – 3 puta dnevno.

Kako bi olakšali korištenje Cannaxina u bilo kojem trenutku, uz kremu dobivate i Cannaxine roll-on kojeg uvijek možete nositi sa sobom u torbi ili džepu. Iznimno je praktičan te vam omogućava nanošenje dok ste na poslu, u šetnji ili dalje od kuće.

Cannaxine roll-on je odlična solucija za olakšanje kad su u pitanju poteškoće u prstima ili teže dostupnim dijelovima tijela. Puno ćete lakše nanositi obzirom na to da ima praktični rotirajući ergonomski dizajn.

Dok sjedite na poslu i osjetite kako vas zateže vrat, Cannaxine roll-on može biti trenutno rješenje! U nekoliko sekundi umasirate roll-onom, ili kremu, i osjetite trenutno olakšanje. Supstanca u roll-onu je prozirna, ne morate se brinuti oko tragova ni količine.

Set sadrži:

· Cannaxine krema 50 ml

· Cannaxine roll-on 15 ml

Proizvedeno u Španjolskoj.

GDJE MOŽETE KUPITI CANNAXINE KREMU I ROLL-ON?

Budite oprezni, na internetu postoji mnogo krivotvorenih proizvoda koji se prodaju pod markom autentične kreme. Certificirani proizvod na području Republike Hrvatske možete kupiti samo na službenoj web stranici na sljedećoj poveznici.

Kliknite ovdje za službenu web stranicu CANNAXINA

0 notes

Text

Svakome treba dobar Feng Shui.

Nekoliko običnih principa Feng Shui-a:

Ukloniti nepotrebne predmete - radi Stvaranja Protoka, Otvaranje Prostora

Kaotičan dom kreira kaotičan život. Kaotičan um.

Počisti ormar i ormarić. Otpusti stvari koje vise ne trebaš.

2. Svaki put kad sjedite negdje, u uredu, na sastanku, dok večerate, pobrinite se da uvijek vidite ulazna vrata. Kreativnost, poštovanje. Kraljica vrata prostora. "You got the power."

U perifernom vidu - Vrata, želim biti sigurna da sam u području Moći

Vrata - usta Chi-a, kreiranja osjećaja dobrodošlice, kreiranje Svemira sa sobom. Želimo Svemiru dati do znanja energije dobrodošlice. Narančasta, bež, zelena. Boje napretka - obilja

3. Predmeti zlatne boje - Always

Zlatna boja

- boja obilja, osjećaj širenja, osjećaj prelaska na sljedeću razinu (u uredu)

4. Spavaća soba - kakve slike ? Što visi iznad uzglavlja? Ne: voda (emocionalna ravnoteža) i samci

5. Ogledala - reflekcija kreveta

6. Biljke - kreiraju Yang i aktivnu energiju - dnevni, blagavaonica, radni prostor, kuhinja

Biljke s iglicama - otrovna energija

Jugoistok/istok životnog prostora - tamo najaktivnije vibracije i najviše će nas podržavati, cvijeće

Vaše okruženje priča priču. Podsvjesno stalno u interakciji.

3 Oskara. Ona je rekla Svemiru da je ona spremna za njih. Ljude/klijente s više Oskara.

Vaš Dom ima svoj Vlastiti Um.

Vaš Dom i dalje šalje signale Svemiru, štogod vam se događa.

Prednost Feng Shui-a - nije potrebna disciplina, jedino nastaviti čistiti stvari koje nam više ne služe.

30 dubina, 210 visina, 180 širina - idealne dimenzije za novu komodu koja će zamijeniti stare ormare u spavaćoj sobi s ogledalima

Marie Diamond

Marie Diamond jedna je od najtraženijih Feng Shui majstorica na Zapadu. Ona koristi svoju intuiciju i duboko poznavanje energetskih sustava, zakona privlačnosti i radiestezije te ih kombinira sa znanjem kvantne fizike, Feng Shuija i meditacije kako bi usmjerila pozitivnu energiju u domove pojedinaca, obitelji, pa čak i velikih korporacija.

Marie je međunarodna autorica bestselera, govornica i savjetnica – ne samo za Feng Shui, već i za iscjeljivanje karme, manifestaciju i druge grane drevne mudrosti. Također je značajno i njeno pojavljivanje u hit filmu Tajna, koji je postao najprodavaniji DVD u povijesti.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Contragate and Counterterrorism: An Overview

Crime and Social Justice

Vol. 31, No. 2 (2003)

Gregory Shank

https://www.socialjusticejournal.org/SJEdits/27-8Edit.html

Crime and Social Justice is pleased to offer this timely special double issue on state terrorism, political corruption, and crime. The issue was initially conceived well before the Iran-Contragate scandal broke when we undertook to publish papers delivered at an April 1986 symposium on "State Terrorism in the Third World" organized by Heinz Dieterich in Frankfurt, West Germany. The symposium became unexpectedly timely as a consequence of the Reagan administration's decision to bomb Libya "in self-defense" under the pretext of countering state terrorism. The topic has remained of enduring interest to Global Options' Terrorism Watch and to other authors working along similar lines whose works also appear in this issue.

The theme "Contragate and Counterterrorism" was chosen to highlight the wrongdoing and strategic excesses of the Reagan presidency. On the one hand, Contragate appears to signify simultaneous changes underway in the rightwing governing alliance at the federal level, and disarray in Reagan administration counterterrorism policy. On the other hand, abundant evidence of systematic criminality exists in relation to the bribery of foreign officials, and the skimming off of profits from arms trafficking in support of world-spanning covert wars. Narcotics traffickers and arms dealers, supplemented by rightwing philanthropists seeking tax write-offs, have joined foreign governments in supporting a war and a terrorist mercenary force the American public has repeatedly rejected.

As in the 1972-1974 Watergate and the 1976-1978 Koreagate scandals, there are allegations of foreign funds (with the potential for blackmail) introduced to influence U.S. electoral elections and congressional votes. New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis observed that, like Watergate, there is sufficient evidence to charge individuals for conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government, in this case with respect to money siphoned off from arms sales to the contras, under the United States Criminal Code, Section 371 of Title 18. Besides perjury and obstruction of justice, another relevant statute would be Section 2778 of Title 22, which makes it a crime, punishable by two years in prison and a $100,000 fine, to export arms illegally (March 24, 1987).

Why were Reagan administration counterterrorism officials so prominent in this scandal? Is the policy in disarray because its implementation has been hypocritical, or because it has fostered instability in the Third World and removed large markets from the arena of legal trade relations at a time when major industries are bursting from overcapacity and many Latin American debtors have ceased to pay the interest, much less the principal, on mammoth loans? From a corporate vantage point, no doubt, a fundamental irrationality governs when it is necessary for Cuban soldiers to protect American oilmen at Chevron's Angola operation against terrorist attacks staged by U.S.-supported UNITA forces and South African commandos.

How can this black-and-white policy be sustained in a world where the nemesis of Libyan terrorism, according to Maas (1986), was made a reality by former CIA officers, Special Forces and Green Beret trainers (and assassins), U.S. explosives manufacturers, and weapons producers? In which the chief entrepreneur of that program, convicted felon Edwin Wilson, could plausibly argue from his cell in Marion Federal Penitentiary that nothing he had done in Libya was different from what Washington was doing covertly in dozens of other countries? In which similar offshore enterprises, "private" armies, and logistical support systems have operated for years to sustain the Nicaraguan contra terrorist forces under the guidance of National Security Council (NSC) counterterrorism staff and CIA liaison officers?

In the passages below, I will touch upon themes that are implicit or explicit in many of the contributions to this issue. Most prominent is the reality that lawbreaking has become an endemic feature of the U.S. imperial presidency. Constitutional restraints on the arbitrary and abusive exercise of executive power have been undermined whenever the invocation of national security interests has served as a veil of secrecy drawn over the executive's conduct of foreign policy. The Reagan administration's counterterrorism program lends itself to secrecy, unaccountability, corruption, and, ultimately, to a violation of democracy. Having become central to a national scandal, the choice for the administration lies either in altering its policy of state terrorism or in professionalizing its execution. The current prospect for change is not promising.

The first section of this issue sets out to resolve definitional questions regarding the semantic and political uses of the concepts of terrorism, antiterrorism, and counterterrorism. The relation of counterterrorism policy to the dominant features of Reagan administration foreign-policy initiatives, and to the violations of international law with which this presidency has become associated, is also developed. Subsequent sections address the two primary foci of the current scandal: state terrorism and the conflicts in Central America and he Middle East.

Contributions on Central and Latin America propose the existence of an international terror network that is integral to the political superstructure of client-state economies, where human and political rights are eroded with each improvement of the business climate for U.S.-based multinational and transnational corporations. Case studies of the repressive instruments required to create this climate -- subversion of national economies, coup d'état, torture, and the annihilation of the political opposition through systematic disappearances and death squad activity -- point to systematic cooperation between global frontier managers, such as the Israeli-U.S. connection, and continent-wide coordination between death squad and intelligence forces. The reason behind the Reagan administration's obstinate adherence to its contra terrorist policy against Nicaragua, in contrast to its more pragmatic approach in Mozambique, for example, is explored in terms of the specific obligations issuing from the domestic and international political alliances with ultra-rightist organizations that helped put Reagan into office in 1980.

The third section deals with the Middle East, in particular the strategic relationship between the United States and Israel, and the crisis in Lebanon. The counterterrorism policy of Israel, much admired by policymakers in Washington, also contributed to the adoption of arms sales as an instrument of foreign policy vis-à-vis Iran. Current investigation shows that this covert policy was operationalized using the same private apparatus and foreign funding sources that support the contra infrastructure.

The remaining sections of the issue include contributions on the Reagan administration's use of the McCarran-Walter Act in the immigration case of Margaret Randall, which represents a wider pattern of ideologically motivated exclusion of divergent points of view, and dangerous infringement of the constitutional right to freedom of speech; on the inhuman conditions resulting from the 22-month lockdown ordered by the Federal Bureau of Prisons at Marion Federal Penitentiary in Illinois; and on new questions raised about the Cold War effort of the Reagan administration to disseminate accounts of the papal assassination attempt of 1981, which purposefully and incorrectly lay blame on the Soviet Union and Bulgaria for a crime perpetrated by a well-known right-wing terrorist.

In presenting the complex issues involved in "Contragate and Counterterrorism," we have attempted to strike a balance between structural causes and conspiratorial motives. Social scientists have traditionally frowned upon theories suggesting the operation of a conspiracy as, at best, too heavily weighted toward the subjective factor and, at worst, as the wild delusions of the powerless, while political realists insist that human agents guide the situational logic that conditions change. Recent history provides adequate evidence that the New Right has outthought and outplanned the political center and the Left, and that its leaders who provide strategic guidance, its managers, and its members have, since the mid-1950s, displayed a corporatist vision and a staying power that we discount only at our collective peril. The Contragate scandal has revealed the operation of an undeniable conspiracy to carry out a foreign policy in violation of the will of Congress, of the American people, and perhaps even against the interests of sectors of the executive branch itself. As is customary, when a U.S. government falls from a crisis of confidence, the sacrificial lambs are the operational and membership layers of the governing structure, and only exceptionally the strategists and funders.

The broad outline of this conspiracy is contained in the affidavit for a federal civil lawsuit filed against many of the principals in the Contragate scandal written by the plaintiff's attorney Daniel Sheehan (1986). This affidavit has, to date, proved to be highly accurate and is useful background material for researchers wishing to dig deeper into the scandal. Using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), created in 1970, the attorneys at the Christic Institute have attempted to establish the existence of the illegal, private contra support network involved in gunrunning, drug smuggling, murder, terrorism, and other crimes in order to bring its members to justice.

The Privatization of Special Operations and Counterterrorism

The individuals who face possible prosecution are ardent defenders of the Reagan Doctrine; they are the cadres inside and outside the government who have performed an activist role in promoting a single-minded, global anticommunist counterrevolution. The powers that be certainly do not fault their resolve. They do, however, lodge criticisms of their planning, execution, and professionalism. On the one hand, the policymakers tended far too much to the details of gun running and bribe paying, and far too little to the exploding Third World debt crisis and to the international isolation of the U.S. resulting from their military unilateralism. On the other hand, they got caught cold running these criminal enterprises, embarrassingly so.

The network called Project Democracy by Oliver North involved its own communications system, secret envoys, leased ships and airplanes, offshore bank accounts and corporations, as well as a divergent array of private groups -- former high-ranking military officers and intelligence personnel, anticommunist Cuban exiles, and conservative groups concerned with stemming the tide of communism in Central America. Individuals at the logistical level have been shown to have remarkably similar historical and political profiles. That profile reflects the overlapping long-term friendship circles of participants in the Joint Unconventional Warfare Task Force in Vietnam in the 1960s, including Operation Phoenix, the CIA-directed assassination and "counterterror" program of which former CIA Director William Casey's friend, General Singlaub, was the onsite commander (Anderson, 1986: 151; San Francisco Chronicle, February 2, 1987; Snepp, 1977: 12).

This Special Operations Group (SOG) reflected Singlaub's unconventional warfare approach, including the secret assassination activities of a unit recruited and operated under the supervision of the CIA Station Chief in Laos, Theodore Shackley, and his deputy Thomas Clines (both of whom had previously run the CIA's clandestine war against Cuba). Oliver North served along the Demilitarized Zone and may have been one of Singlaub's deputies in the program; the Deputy Air Wing Commander for SOG airborne resupply was Air Force General Richard Secord, a man with special operations expertise in expediting the movement of cargo from one place to another, who, by some accounts, saved North's life there. Secord's superior was General Harry "Heine" Aderholt (Maas, 1986: 31; Sheehan, 1986: 34; Insight, February 12, 1987; New York Times, October 24, 1986). Edwin Wilson had delivered tons of equipment and supplies under the cover of his Maritime Consulting proprietary (Maas, 1986: 31), while Erich von Marbod had become arbiter of all military assistance to Vietnam as the comptroller of the Defense Security Assistance Agency, and at the fall of Saigon personally directed the destruction or removal by sea and air of U.S. military hardware (Ibid.: 36; 53). The brother of another key figure in the contra scandal, Robert Owen, was a member of an Army Special Forces unit in the SOG. Assistant Defense Secretary Richard Armitage, who also figures in the scandal, administered funds for the Phoenix Project during his tour at the Saigon U.S. Office of Naval Operations from 1973 to the fall of Vietnam in April 1975 (U.S. News & World Report, December 15, 1986: 23; Sheehan, 1986: 35; Time, March 9, 1987).

Others central to the private contra resupply operation were anti-Castro Cubans, members of the 2506 Brigade, who had worked under Shackley and Clines in the CIA's covert war against Cuba during the Kennedy administration as members of the special team that infiltrated into Cuba prior to the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. According to Sheehan (1986: 32), these individuals were recruited and trained as political assassins by the Havana and Tampa Mafia figure, Santos Trafficante, in a CIA program under the supervision of E. Howard Hunt, of Watergate renown (see also Powers, 1979: 187).

One, Felix Rodriguez ("Max Gómez"), a friend of Shackley and Vice President Bush, who had also been a member of the CIA unit responsible for the death of Che Guevara in Bolivia in 1967, was sent to Vietnam in the early 1970s as a CIA airmobile counterinsurgency expert. A second ex-CIA Cuban was Luis Posada ("Ramon Medina"), who escaped in August 1985 from a Venezuelan prison after awaiting trial (along with the terrorist Orlando Bosch) on charges linked to the Cubana airliner bombing that killed 73 people (San Francisco Chronicle, November 4, 1986; New York Times, October 12, 1986; October 13, 1986; October 16, 1986; October 22, 1986). A third Cuban, a former CIA sabotage and assassination expert named Rafael Quintero, supervised the arrival of weapons in Central America and coordinated weapons drops inside Nicaragua as part of a network including Richard Secord, Albert Hakim, and Thomas Clines (San Francisco Examiner, December 7, 1986). Quintero was replaced by the Secord employee, Robert Dutton, in 1986 (Ibid.), who had worked with Secord in Iran before the fall of the Shah, as had von Marbod, Edwin Wilson, and Albert Hakim, Secord's business partner who sold surveillance systems to the Shah's secret police (the Savak). The privatization of foreign policy was already well developed at that point, as Shackley, Clines, Secord, and Armitage supervised, directed, and participated in a nongovernment covert "antiterrorist" assassination program set up by Edwin Wilson to eliminate potential opponents of the Shah (Sheehan, 1986: 36-37).

This private foreign policy was an analog to the formal contractual relation these individuals entered into with Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza in an operation that was eventually taken over by the CIA in June 1981, when President Reagan authorized the CIA to undertake the financing, training, and military supply of the Honduras-based contras. When Congress was drafting the Boland Amendment in 1983, Oliver North contacted Shackley, Clines, Hakim, and Secord and had them reactivate their military supply operation to the contras (Sheehan, 1986: 40-41). A former White House official stated that the administration already had private backup because the "handwriting was on the wall in 1982" (U.S. New & World Report, December 15, 1986).

WACL, Countersubversion, and Counterterrorism

North was also instructed by William Casey, and perhaps others on the NSC, including George Bush (New York Times, March 25, 1987), to contact Robert Owen of Gray & Company (a Washington, D.C., public relations firm). Owen was to publicly solicit funds and assistance for the contras in coordination with John K. Singlaub's U.S. Council on World Freedom (Sheehan, 1986: 16), set up on November 22, 1981, four days after a secret approval by Reagan of a CIA plan to begin direct assistance to the contras (Anderson, 1986: 150-152; Dickey, 1983: 112). This underscores a second essential element in the Project Democracy profile: affiliation with the Taiwanese and South Korean-supported World Anti-Communist League (WACL), which maintained a low profile until Singlaub's leadership of that organization was widely publicized in relation to his role, along with North and Secord, in the contra resupply network. These two networks are linked in their origins: the CIA with Shackley, Clines, Singlaub, and former deputy director of intelligence, Ray Cline, were central to the creation in 1954 of the Asian People's Anti-Communist League (APACL), the predecessor of WACL (Sheehan, Amended Complaint, 1986: 15; Anderson, 1986: 55).

As Anderson (1986: 155) points out, if the memberships of officers of the United States Council for World Freedom in other New Right organizations are taken together, they give WACL a voice in all the major coalitions of the American New Right movement. WACL affiliates would come to engage in joint operations in Central America, and act as unofficial envoys of the Reagan administration in establishing links with ultra-rightists in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. The action-oriented members of WACL organizations repudiated a reliance on electoral change, having discovered that the state, even under the control of the most right-wing president in history, failed to serve as the ideal motor of their anticommunist revolution. Although they remained deeply embedded in governmental structures, they revitalized WACL to carry out their own foreign policy and to forge their own alliances internationally. WACL moved to support "freedom fighters" in Third World anticommunist insurgencies, especially in Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Nicaragua, and Afghanistan, and its U.S. affiliates also moved to maintain dossiers on domestic "subversives" (Ibid., 1986: 258).

The counterterrorist drive launched at the onset of Reagan's first term in office had not ultimately served to radically expand the FBI's covert intelligence functions to 1950s or even pre-Watergate levels, as the Right had hoped, despite the FBI's reinvigorated statutory capabilities. The post-Watergate FBI under William Webster had been compelled, as had the CIA under Admiral Stansfield Turner and President Reagan's current national security adviser, Frank Carlucci, to purge long-term covert operatives accustomed to unlawful J. Edgar Hoover-era methods. The FBI lacked an empirical basis to justify increasing its antiterrorist staff and budget because real incidents were continually diminishing, totaling 52 in 1979, 30 in 1980, and only 17 in 1986 (Motley, 1983: 16). Nonetheless, pressure was applied from the Senate Subcommittee on Security and Terrorism and from high-level military analysts, such as Colonel James B. Motley at the National War College, in an effort to exploit terrorism as the primary political means to reconstitute domestic and international intelligence structures.

Webster tended to reject the term "subversion" because of its definitional unclarity: the operational consequences of accepting an expansive concept of terrorism that encompassed criminal and noncriminal activities were covert, secret intelligence operations instead of narrower criminal investigations based on probable cause that a law may be violated. As a result, dossier building and surveillance of the corporate Right's domestic opposition were privatized, institutionalized most notably in the terrorism and subversion-oriented Western Goals (the brainchild of the late chairman of the John Birch Society, Larry P. McDonald),1 in Lyndon LaRouche's informant network, and most recently, in other as yet unnamed rightwing groups and foreign agents under investigation for the 59 nationwide political burglaries by the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights. What the FBI has been doing with its massive budget increases in recent years, it should be cautioned, remains to be analyzed.

Counterterrorism in Law and Language

The FBI's cautious approach to countersubversion was not replicated by foreign policy officials. Gregory Shank's article in this issue, "Counterterrorism and Foreign Policy," argues that chief policymakers in the NSC adopted the broader definition of terrorism to guide international relations. Secretary of State George Shultz, for instance, articulated a widely held rightwing belief that terrorism is a weapon of global unconventional warfare aimed at U.S. strategic interests. This echoed Rand Corporation and Heritage Foundation terrorism analysts, who forecast that low-intensity conflict would be the primary challenge to the U.S. through the end of the 20th century; it also echoed the unconventional warfare activist orientation of General Singlaub's U.S. WACL chapter, founded in 1981 just as Reagan forces had assumed federal power. Secretary of State Shultz also actively pushed the idea that conventional military attacks against terrorist targets should accompany unconventional warfare. Within the Reagan administration, the notion of rolling back "communist terrorism" was coupled with 19th-century "just war" ideology and grafted onto Brigadier General Ed Lansdale's counterinsurgency warfare premise of a democratic anticommunist revolution. These concepts are the ideological mainstays of the Reagan Doctrine.

Secretary Shultz' public proclamations emphasized that "we do not practice terrorism, and we seek to build a world...in which human rights are respected by all governments, a world based on the rule of law." Edward Herman's article in this issue analyses the semantics of terrorism that make possible the "if I don't like it, call it terrorism" approach to this complex phenomenon. The article outlines the intellectual illusions created in state-supported analyses through the systematic exclusion of governments as the dominant practitioners of state terror, and points to U.S.-supported dictatorships, where death squads have operated as an extension of the state repressive apparatus and there has been the wholesale use of terror as a mode of governance. The use of "counterterrorism" in Western terrorism semantics fills the need created to describe the policies of the United States, South Africa, El Salvador, and Guatemala, all of which "do not engage in terrorism," as Secretary Shultz points out. Their attacks on their enemies require the use of alternate words. The term "retaliation" is handy, but it implies a response to an immediately preceding act. Longer-term, continuous assaults on bases and populations of "terrorists" are therefore termed "counterterrorism" to disguise their function as state terrorism. When the Reagan administration announced that human rights would be replaced by terrorism ("the ultimate abuse of human rights") as a guiding principle of U.S. foreign policy, this indicated its tacit shift toward WACL's "counterterrorism."

During the Carter administration, counterterrorist national command and policy formulation had become located in the Special Coordination Committee (SCC) of the National Security Council (NSC). Members of the SCC are statutory members of the current NSC -- e.g., President Reagan, Vice President Bush, Secretary of State Shultz, Secretary of Defense Weinberger, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Adm. William J. Crowe, and the Director of Central Intelligence at the time of the scandal, William Casey. These officials are served by a staff directed by the national security adviser. Initially, two interagency groups, both chaired by representatives of the State Department, coordinated the program and provided guidance: one, the strategic Executive Committee on Terrorism (with representatives from the CIA, the NSC, and the Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Treasury, Transportation, and Energy), and two, the 29-agency Working Group on Terrorism. In theory, the Department of State is mandated to conduct foreign relations and is charged with developing and refining policy with regard to international terrorist threats and incidents involving U.S. citizens and interests abroad, operating through its Office for Counterterrorism and Emergency Planning (Motley, 1983: 34-37).

In December 1985, the Reagan administration released an abridged version of Vice President Bush's National Security Council Task Force on Terrorism. The Task Force members, it should be noted, included many who have recently gained Contragate notoriety: William Casey, Adm. John Poindexter, Donald Gregg, Oliver North, Lt. Gen. John Moellering, Lt. Col. Douglas Menarchik, Charles Allen, Craig Fuller, Craig Coy, and Lt. Col. Robert Earl. The report recommended creation of a full-time NSC position with support staff to coordinate two counterterrorism units (Village Voice, March 24, 1987). Within the NSC's delegation of tasks, Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North -- the deputy director of the political-military affairs division (the covert operations arm under President Reagan) -- was the foremost candidate. He served for five years under a variety of national security advisers and ultimately held two crucial and related portfolios: the contra war effort and the antiterrorist and counterterrorism policy (San Francisco Chronicle, November 25, 1986; January 21, 1987). Perhaps North exaggerated when he told the rightwing Concerned Women for America that he briefed President Reagan twice weekly on these two areas; there is no doubt, however, that Reagan liked North, the born-again Christian possessing academic and hands-on experience with low-intensity warfare. He called him Ollie and a hero (San Francisco Chronicle, December 7, 1986; March 2, 1987; New York Times, December 4, 1986).

North guided the interagency counterterrorism group at the White House, meeting with, among others, Oliver B. Revell, an assistant executive director of the FBI and NSC consultant who was compelled to remove himself from the FBI's Iran arms sales criminal investigation once North became a suspect (New York Times, December 4, 1986). Charles Allen, the national intelligence officer for terrorism at the CIA, also worked with North, and eventually was to transmit to Iran intelligence about Iraq's war effort using the former Savak agent and arms middle-man, Manucher Ghorbanifar, as part of the arms-for-hostages deal (New York Times, February 27, 1987).

Like the contra war, counterterrorism policy became lodged in a unit parallel to the established structure. It was here that some principals in the scandal operated beyond the pale of institutional accountability. Major General Secord (who ran Project Democracy along with North and Singlaub) helped run a secret counterterrorism unit authorized by President Reagan in April 1984 with the signing of National Security Decision Directive 138. This document reportedly was drafted by Oliver North and promoted pre-emptive military strikes against terrorist targets. The counterterrorism unit was first proposed in 1982 and 1983, and reported directly to the NSC at the White House. It was intended to "take tough approaches to terrorism" by circumventing the State Department, Defense Department, and the CIA because of their reluctant, slow, and supposedly leak-prone bureaucracies (San Francisco Examiner, March 8, 1987). Colonel Robert L. Earl, North's assistant at the NSC who helped former national security adviser Robert C. McFarlane prepare a misleading chronology of the Iran initiative, was a member of the special counterterrorism unit (New York Times, March 18, 1987; San Francisco Chronicle, March 19, 1987).

After the U.S. bombing of Libya in April 1986, North blamed the CIA for the death of an American hostage who was killed by his Lebanese captors in retaliation. He referred to circumventing the interdepartmental group on terrorism and recruiting a 40-man, U.S.-controlled Druse force that reported to Secord and Amiram Nir, the Israeli counterterrorism adviser to Prime Minister Peres (who may owe his selection for the job to his consultative role on Vice President Bush's National Security Council Task Force on Terrorism) (New York Times, March 2, 1987; San Francisco Chronicle, December 4, 1986). As a result of the Contragate scandal, Congress may investigate whether the NSC covert unit operated in conjunction with the Pentagon's Intelligence Support Activity unit in carrying out the 1985 car bombing in Beirut that killed 80 people (an action attributed to the CIA). It is also this unit that would have carried out proposed kidnappings of terrorist suspects authorized by President Reagan in 1986 (New York Times, February 24, 1987; Bamford, 1986).

In 1986, the Defense Department's National Security Agency provided North with 15 encryption devices (which have "disappeared") for "counterterrorist activities" which he, Secord, and a Costa Rica-based CIA agent ("Thomas Castillo") used to create a private communications network outside the purview of other government agencies with which they communicated with members of the private contra supply network (Tower Commission, in New York Times, February 27, 1987; March 25, 1987; San Francisco Examiner, March 22, 1987). The counterterrorism of Project Democracy had as its wider goal purposefully directed terror aimed at restoring the status quo ante in Nicaragua. Because this goal was not explicit public policy and clearly violated international law, its true nature was disguised.

Donald Pfost's article in this issue, "Reagan's Nicaraguan Policy: A Case Study of Deviance and Crime," analyzes these Reagan administration violations of international and domestic law, as well as the policy's ideological underpinnings. The article argues that U.S. policy toward Nicaragua must be considered a species of political crime, differing from the more conventional criminological approach, which has legitimated such interventions by characterizing them as "political policing." The catalogue of crimes in the Irangate-Contragate scandal minimally includes conspiracy to obstruct justice, conspiracy to commit perjury before Congress, and conspiracy to defraud the federal government. Other laws or acts of Congress possibly violated by the secret financing of the contras are the Boland Amendment, which prohibited military aid to the contras by federal agencies, and the Arms Export Control Act, which bars military aid to any country supporting terrorism. Also violated was the Neutrality Act, which makes it a criminal offense to aid or participate in military expeditions against countries with which the U.S. is at peace. Internationally, the World Court decided that U.S. actions against Nicaragua were contrary to international law, and as Shank and Pfost argue, a counterterrorism policy that resorts to pre-emptive military strikes against sovereign states under the U.N.'s collective self-defense doctrine also violates international law.

Contragate and the Reagan Doctrine

Despite early recognition of many of these violations, the Reagan administration, in its effort to reverse public antipathy to intervening in foreign revolutions, successfully exploited public fear of "random" nonstate terrorist violence as the primary ideological vehicle to replace moribund anticommunism. Funding the contra terrorist war against Nicaragua was presented by the administration as part of a seemingly coherent antiterrorist global strategy and moral imperative that encompassed:

1. Classical counterinsurgency warfare (against "terrorist subversion" that had evolved into guerrilla war) in Central America, utilizing Special Operations Forces (SOF) supplemented by police and intelligence service training programs in "counterterrorism";

2. Long-term "contra"-type rollback operations in Asia, Africa, the Near East, and Central America against U.S.-defined "state terrorist" regimes (i.e., socialist or radical nationalist states outside the U.S. sphere of interest), also employing SOF units in conjunction with mercenary armies. The Reagan Doctrine here tapped WACL, with its expertise in unconventional warfare, including terrorism, as a "third option" (in Theodore Shackley's term) against the "Soviet Empire";

3. Short-term "active self-defense against terrorism"-type operations featuring pre-emptive military actions, such as the combined SOF and quick-strike conventional forces launched against Grenada and Libya, were viewed as a low-risk, high-payoff variant of the Reagan Doctrine.

The seeming coherence in this triad belied fissures in the Reagan Doctrine. According to conservative analysts, resistance to the doctrine emanated from a faction in the executive branch that preferred a strategy of negotiations with Afghanistan, Angola, and Nicaragua. Negotiations were geared to a "political transition model," that is, forcing a change in the current government by requiring the incorporation of U.S.-sponsored anticommunist insurgents into these governments (through "free elections" and "democratic reforms"), and the elimination of their reliance on Soviet-bloc assistance. This group included most of the State Department, the military officers in the Department of Defense, and some key CIA officials such as former Deputy Director John N. McMahon, who opposed the Afghan program and resisted arms sales to Iran not authorized by the president.

The second faction, which pursued a strategy of violently overthrowing these governments and replacing them with more pliable anticommunist regimes composed of the prerevolutionary ruling strata, included key members of the National Security Council staff, ranking Defense Department civilians (Secretary Weinberger, Nestor Sanchez, and Richard Armitage), the CIA (Director Casey, his task force chief on Nicaragua, and Clair George, the deputy director for clandestine operations), and the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Elliott Abrams (Insight, March 16, 1987: 11; San Francisco Chronicle, February 2, 1987). In Congress, it was a Democrat, Congressman Stephen J. Solarz (N.Y.), who provided the primary impetus for funding the mercenary terrorists.

In 1981, President Reagan signed National Security Decision Directive 17, which was a secret declaration of covert war against Nicaragua (Bamford, 1987). Project Democracy, the parallel foreign policy apparatus born of the Reagan administration's antidemocratic thrust, was first mentioned by Reagan in a 1982 speech. But the worldwide network, funded initially by foreign governments as early as 1981, became the covert manifestation of the Reagan Doctrine beginning in 1983 (San Francisco Chronicle, February 16, 1987). At that time, the White House was displeased with State Department reluctance, and believed that Reagan Doctrine initiatives had to be run covertly to circumvent opposition. Responsibility for coordinating the program fell to the National Security Council staff, which was empowered to implement it by a January 1983 presidential national security decision directive that permitted the council to coordinate interagency "political action strategies" against the Soviet Union and its "surrogates" (Insight, March 16, 1987). This, it is said, was the genesis of the series of events documented in the Tower Commission report.

State Terrorism in the Americas

The contra terrorist war against Nicaragua is modeled after the CIA's covert war against the Cuban Revolution, which had represented the first rift in U.S. hemispheric hegemony. As James Petras points out in "Political Economy of State Terror: Chile, El Salvador, and Brazil" in this issue, the contra war is part of a wider process that has witnessed the growth and proliferation of state terror networks in Latin America that are part of, and in most cases subordinated to, an ongoing global terror network. Washington has become the organizational center for a variety of institutions, agencies, and training programs that provide the expertise, financing, and technology to service client-state terrorist institutions. Since the 1970s, this expertise has been supplemented by private services run by former intelligence and military officers.

All recent administrations, Democratic and Republican, have supported this network, and it has served as a significant foreign policy instrument. Martha Huggins' article, "U.S.-Supported State Terror: A History of Police Training in Latin America," is a case study of the official export of technologies of repression by the U.S. to client regimes to improve their capacity to destroy oppositional political and social movements through death squad activity and disappearances. In 1974, Congress prohibited funding for CIA and USAID-directed police training because of widely publicized human rights abuses; that function was then assumed by Taiwan's WACL-related Political Warfare Cadres Academy, which trained, among others, the El Salvadoran death-squad organizer Roberto D'Aubuisson (Anderson, 1986). Subsequently, a pliant Congress allowed the Reagan administration to re-institute U.S.-supported Programs in Central America as "counterterror" assistance against fabricated Nicaraguan and Cuban "terrorism."

Peter Dale Scott's article, "Contragate: Reagan, Foreign Money, and the Contra Deal," focuses on the network of former CIA officials and agents of influence as well as other international backers of the contras, who comprise what a Senate Committee report has described as the CIA's "world-wide infrastructure." Scott argues on the one hand that there are signs that Contragate represents both the illegal intervention of these backers in U.S. elections through the recycling of foreign-based funds, and the factional struggle for power hinging on relations with the intelligence community. On the other hand, Scott says, Contragate is the collusion and conspiracy to install and maintain a U.S. covert operation (despite the expressed will of Congress) that can be traced, first to the decisions of successive CIA directors to scale down and virtually eliminate clandestine services, and, second, to the existence of "offshore" intelligence operations (elements of Project Democracy), which grew as the CIA's covert assets were dispersed.2

These reforms of the CIA had the effect of building a powerful coalition of both Americans (ousted CIA clandestine operators, the Taiwan-Somoza Lobby, and the American Security Council) and foreigners (the World Anti-Communist League, and the secret Masonic Lodge guiding rightwing government actions across Italy, P-2) who were determined to restore the clandestine services. The rightward shift of political power as a result of the 1980 presidential election sharpened the prospects for a revival of domestic intelligence structures and operations and suggested a return to the weapon of secrecy afforded by intelligence, which permits unaccountability and freedom from the control of constitutional constraints and norms restricting official state action, and freedom from prohibitions on interfering with political expression.

The strong domestic lobby for U.S. covert operations included long-established spokesmen and funders of a "forward strategy," "political warfare," and "low-intensity conflict," grouped primarily in the most powerful of the manifestations of the military-industrial complex, the American Security Council (ASC).3 The ASC had aided Taiwan's foreign policy creation, the World Anti-Communist League, by setting up the American Council for World Freedom. Before Reagan, however, WACL had been marginal to U.S. foreign policy, partly because of the recurring involvement of its personnel in the international drug traffic, but also because the U.S. chapter had come under the control of extreme racists who were decidedly too profascist for domestic consumption.

In 1980, the ASC received the support of those CIA veterans of the clandestine services who had been eased or kicked out of the CIA. The ASC's affiliate, the Coalition for Peace Through Strength (CPTS), drew together some of the most influential elected officials and former military officers, and was headed by General Singlaub and General Daniel 0. Graham, as well as by retired Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Admiral Thomas Moorer of Western Goals (Anderson, 1986: 157).

Covert Funding Mechanisms and Political Corruption

After passage of the Boland Amendment the administration conspired to continue the contra program ostensibly outside the State Department and the CIA. This had two operational consequences: the first was to turn to extra-governmental expertise in the military and logistical aspects of covert war (Singlaub, Secord, and his business partners); the second was to secure covert funding outside congressional channels.

In the 1950s, the CIA had directly disbursed millions of dollars to pro-U.S. officials, politicians, political parties, unions, and news media in Europe and throughout the Third World. In the 1960s, after these payments had been exposed and became a domestic scandal, payments to the CIA's foreign networks were continued through a global system of "commissions" or political payoffs (including laundered U.S. Air Force funds) made by Lockheed Corporation to its foreign representatives such as Adnan Khashoggi, a Saudi businessman who is close to the Saudi royal family (Scott, 1986; Hougan, 1979). Partly as a result of the reforms of the CIA, U.S. and foreign CIA agents of the 1950s became the affluent arms salesmen of the 1970s, and individuals such as Khashoggi, wishing to leave a mark on history beyond accumulated wealth, engaged in diplomatic efforts. Khashoggi was an architect of improved Iran-Israel-U.S. relations, as well as of the current Saudi Arabia-South Korea entente, which underlies the contra-supporting World Anti-Communist League (Scott, 1986).

Since the Carter presidency, a third system of payments for covert U.S. operations abroad had evolved: the hidden "costs" in the shipment of U.S. arms sales. As with the "commissions," these costs are borne by the foreign purchaser. Under this system, middlemen would purchase government aircraft and weapons at a low "manufacturer's cost," and sell them to nations at the much higher "replacement cost." The U.S. government would be reimbursed at the lower cost, and the difference was transferred to finance privately run covert operations. These government deals would therefore take place under the control of private companies directed most recently by retired U.S. military personnel and foreign middlemen (Ibid.). This is the contour of much of the Project Democracy funding scheme.

The "privatization" of the contra war began with the decision of high Reagan administration officials to circumvent planned congressional restraints on the CIA after it was caught violating international law in 1983 with the mining of civilian harbors in Nicaragua and the passing out of manuals advocating the physical assassination of civilian government authorities inside Nicaragua to bring about the overthrow of that government. To date, it is known that former CIA Director William Casey moved the operation to the NSC, where Oliver North was located, in order to claim executive privilege were Congress to investigate its activities. Sheehan (1986: 16) makes the claim -- as yet not verified by other sources -- that Edwin Meese, George Bush, and Robert McFarlane conceived of this plan.

Arms Sales as Foreign Policy

When the U.S. intervenes abroad using weapons sales in excess of $14 million as a tool of diplomacy, the permission of Congress is required. An administration proposal to sell $354 million worth of missiles to Saudi Arabia immediately after the U.S. bombing of Libya in April 1986 was therefore debated in Congress. Supporters of the sale claimed that to combat the terrorist threat posed by Libya, U.S. arms sales were needed to cement relations with "moderate Arab states," such as Saudi Arabia. Assistant Secretary of State Richard Murphy said the sales were needed to send "a political signal" to the Iranians, whose military successes against Iraq had placed Saudi oil fields in jeopardy (New York Times, April 18, 1986).

To fund the contras through arms sales was surely to employ such sales as a tool of foreign policy without congressional approval. This situation benefited central figures in Contragate such as Clines, Secord, and von Marbod, who had become involved in the covert arms flow to the contras. Although he was to become a member of the Pentagon's Special Operations Policy Advisory Group following his official retirement in 1983, Secord became a private arms supplier to the contras, operating much as Edwin Wilson had. His connections with the contras, with the rulers of Iran, and with the royal house of Saudi Arabia especially suited him for the role, and his affiliations were considered unmatched by anyone in the military. As it turned out, the funneling of Saudi millions to the contras in 1984 and 1985 was through Secord and Hakim. In 1985, Prince Bandar, the Saudi Ambassador to the U.S., asked a California businessman to initiate unrelated business dealings with Secord and Hakim, both to mask the proposed contra funding deal and to help General Secord's business. Secord had participated in the controversial $8.5 billion sale of AWACS aircraft to Saudi Arabia in 1981, a deal which generated millions for the contras in 1981, and as much as $250 million for the WACL-supported antigovernment guerrillas in Afghanistan. This diversion of funds flowed from an agreement made by Saudi Arabia's King Fahd and Prince Bandar bin Sultan. Contra leaders admit receiving $32 million from Saudi Arabia as a result of the AWACS deal (San Francisco Examiner, July 27, 1986; Newsweek, December 15, 1986; U.S. News and World Report, December 15, 1986; New York Times, February 4, 1987; San Francisco Examiner, March 15, 1987).

A complex of interests was at stake in the covert Saudi role other than financing the U.S.-Iran arms pipeline. Indeed, the move toward improved relations with Iran favored by King Fahd resulted in a power struggle in the royal family. Prince Sultan, the Saudi Defense Minister, had argued for a rapprochement with Iran after assessing that its close ally, Iraq, was unlikely to win its war with Iran. Part of that bridging effort would require supporting Iran's $18-a-barrel price for oil (New York Times, November 27, 1986). Vice President Bush and his Republican allies from Texas publicly supported the $18 price. Khashoggi was a key intermediary in securing the necessary degree of mutual understanding between Iran and Saudi Arabia. According to Scott (1986), the Iran-Israel-U.S. arms deals have been interpreted as only one aspect in this process of strengthening Saudi-Iranian understanding.

State Terrorism in the Middle East

Irangate demonstrates that the U.S.-Israeli strategic partnership shares a common global perspective, but the respective goals within that strategy conceal divergent material and political interests. Similar to the U.S., Israeli counterterrorism officials and private arms merchants figure prominently in this scandal, where covert operations -- such as the bribery of Iranian officials to gain influence and the diversion of millions of dollars to Project Democracy -- were funded through cash transfers resulting from overpayments (hidden costs) by Iran in its purchases of U.S. weapons. Although the Reagan administration had adamantly denounced state-supported terrorism in the Middle East and the "outrageous weapons deals made by Western European nations with the terrorist states in pursuit of appeasement," in August 1985 President Reagan approved the first shipment of U.S. arms by Israel to Iran (Anderson, San Francisco Chronicle, December 1, 1986). A schism between publicly stated counterterrorism policy and practice had developed under the mantle of intelligence gathering, the rationale for which was freeing hostages (and thereby picking up votes in the 1986 congressional elections), and combating terrorism.

U.S. government hypocrisy also extended to excusing the state terrorism of its allies in the Middle East. Noam Chomsky's article, "International Terrorism: Image and Reality," analyzes the Israeli model of countersubversive "antiterrorism" that the U.S. foreign policy elite (most notably Secretary of State Shultz and former CIA Director Casey) came to uncritically embrace. That policy reduced itself to the subjection of entire populations, such as southern Lebanon, to unremitting terrorism and foreign domination in the name of eliminating the "evil scourge of terrorism."

The policy of selling arms to Iranian "moderates" was not debated either in the U.S. or in Israel. While the U.S. ostensibly desired a war without victors, an important elite consensus in Israel sought a war without end. Politicians such as Ariel Sharon and Shimon Peres, and intelligence people like Yitzhak Shamir and Foreign Minister David Kimche shared this view (Aronson, 1987: 20). David Kimche, a 30-year veteran and one-time deputy director of Israel's Mossad intelligence service who has long been a central figure in developing Israel's counterterrorism policy, met twice with Oliver North in 1985 (San Francisco Chronicle, November 24, 1986; New York Times, December 30, 1986). Jacob Nimrodi, a founder of, and former colonel in, Israeli military intelligence and a military attaché in Teheran for a decade, was an important part of that consensus. Nimrodi, believed to be one of the richest men in Israel because of his arms deals with the Shah of Iran, was instrumental in opening up the U.S.-Israel pipeline to Iran and had agreed to sell U.S. weapons to Iran as early as 1981 (New York Times, December 1, 1986; San Francisco Examiner, November 30, 1986).

Both Nimrodi and Al Schwimmer, the American-born founder of Israel Aircraft Industries, benefited from opening up the weapons pipeline and are close friends of Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Peres participated in the original arrangements worked out between Iran and Washington, exchanging arms for hostages (New York Times, December 1, 1986; San Francisco Chronicle, November 27, 1986).

Jan Nederveen Pieterse's "The Washington-Tel Aviv Connection: Global Frontier Management" analyzes the history of the long-term U.S.-Israeli strategic relationship, including Israel's engagement in the military conflict against Nicaragua since 1981, and Israel's possible geopolitical interests in arming Iran. The article extensively details the history of U.S. arms sales to Israel, and Israel's economic dependence on the U.S., which totals a flow of $3 billion this year (Insight, February 23, 1987). It also supports part of the Tower Commission report, which concluded that Israeli motives in arming Iran included the promotion of its arms export industry, the weakening of its old adversary, Iraq, and the desire to draw the U.S. into arms sales to Iran in order to distance the U.S. from the Arab world, and ultimately to establish Israel as the only real strategic partner of the U.S. in the region (New York Times, February 27, 1987).

Other authors have proposed that the U.S. was drawn into an Israeli scheme favoring arms sales to develop intelligence contacts within Iran because NSC aides were uncritically attracted by Israeli intelligence capabilities and political analysis (Aronson, 1987; New York Times, November 27, 1986). These included Robert McFarlane; Dennis Ross, the NSC's Middle East specialist; Howard Teicher, the NSC's senior director of political-military affairs; the late Donald R. Fortier, who was a deputy Assistant to the President; and Michael Ledeen, an NSC counterterrorism consultant hired by McFarlane, and a founder of the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs in Washington, which supports a close alliance with Israel (New York Times, November 27, 1986).

As the State Department terrorism expert in Reagan's first term, Ledeen sought public support for covert actions aimed at the assassination of terrorists; he also hawked the idea, repeated by the American Security Council, that Nicaragua's Sandinista government had organized "a vast drugs and arms smuggling network to finance their terrorists and guerrillas, flooding our country with narcotics" (New York Times, February 2, 1987).

A friend of Theodore Shackley and recipient of Shackley's 1984 summary of Ghorbanifar's proposal, Ledeen played a decisive role in the initial stages of the Iran weapons-and-bribes initiative, coordinating directly with Israel's Foreign Minister David Kimche and Prime Minister Peres (Ibid.). Amiram Nir, the counterterrorism adviser to the Israeli prime minister, alleged to Oliver North in a memo printed by the Tower Commission report that Ledeen profited by as much as $50 for each missile the Iranians got (New York Times, March 25, 1987). Ledeen denies it and has repeatedly denied being an agent of Israel's intelligence service, Mossad, but the Israeli government refused to go on record retracting Nir's statement (Ibid.; New York Times, February 2, 1987).

Many of the principals in the current scandal were participants in the failed April 1980 U.S. hostage rescue attempt in Teheran. The operation included Secord, North, Hakim, and Cyrus Hashemi, a cousin of Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the "moderate" speaker of the Iranian parliament, who first revealed Washington's secret arms shipments (New York Times, January 16, 1987; Insight, January 12, 1987; San Francisco Chronicle, January 6, 1987; November 29, 1986). This constellation of individuals was central to carrying out -- and perhaps played a role in shaping -- the new U.S. covert policy vis-à-vis Iran. Since the early 1980s, Hakim had tried to continue doing business with Iran and to persuade the Reagan administration to improve relations with Iran. In April 1984, Cyrus Hashemi stated after meeting with Manucher Ghorbanifar (the first go-between for the U.S.-Israel-Iran deals) that the two men planned to "go and buy weapons through Albert Hakim in the U.S. and sell them to Iran" (New York Times, January 16, 1987; San Francisco Chronicle, December 5, 1986).

Privatization of the Iran arms sales policy had as its entree a January 17, 1986, secret intelligence finding signed by President Reagan that authorized the CIA to "interfere in the affairs of a foreign country," and to assist "third parties," as well as foreign countries, in shipping weapons. The operation was an extension of an Israeli initiative designed to gather intelligence and to shape the behavior of the regime of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his successor. When turning the project over in July 1985, Israel's Foreign Minister David Kimche handed Robert McFarlane an intelligence source -- a senior ayatollah in Teheran -- developed by Mossad through channels opened with secret Israeli arms sales to Iran (San Francisco Chronicle, November 24, 1986). The State Department and Defense Secretary Weinberger reportedly opposed the plan largely because the covert operation gave the CIA and NSC in the White House leading roles in developing and managing new foreign policies toward Iran (Ibid.).

To their dismay, in January 1986, Nimrodi, Schwimmer, and Kimche were replaced by the prime minister's counterterrorism expert, Amiram Nir. According to the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Aharonoth, Prime Minister Peres was uncomfortable with the idea of an Israeli, especially one of his friends, making commissions on the transactions. Perhaps more pointedly, Haaretz reported that some Israeli mediators had "meddled" with the bank account in Switzerland that was used to channel money from the Iranians to the Americans and eventually to the contras (New York Times, December 1, 1987).