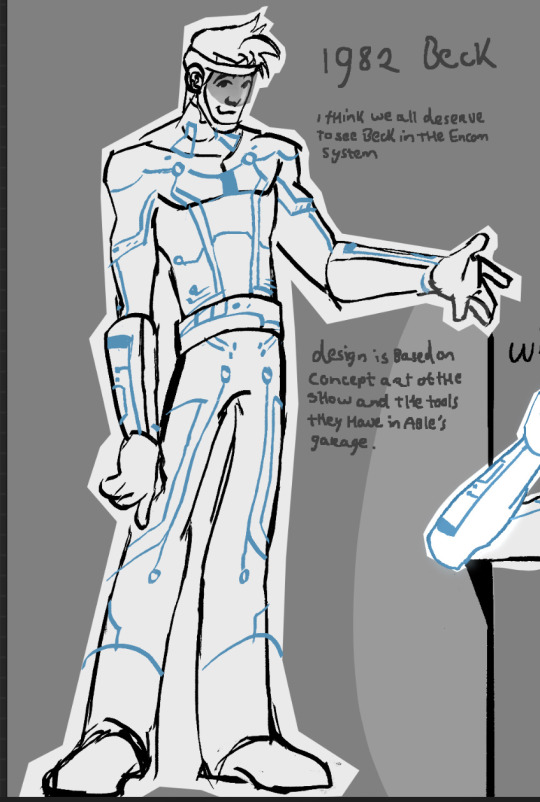

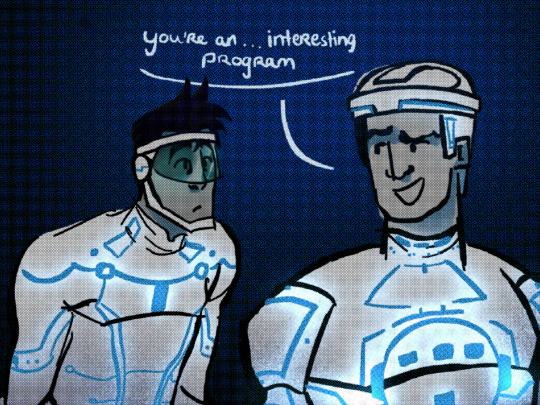

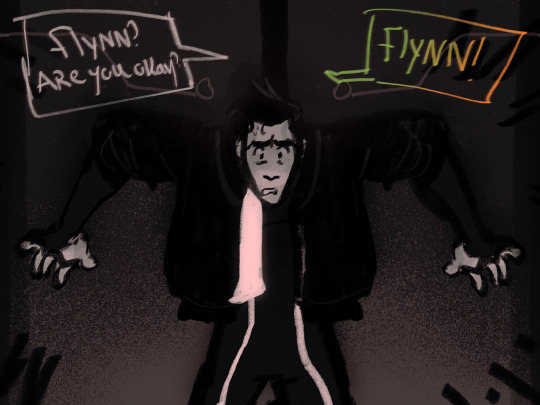

#something something also foreshadowing for Rinzler

Text

Okay lemme go crazy for a sec

Season 2, episode 9: Guilt

When Tron’s simulation machine malfunctions while he’s attached to it, Beck has no choice but to manually figure out what’s wrong, getting transported into Tron’s system. Time for a trip down memory lane.

As Beck travels through Tron’s system, things start to freak out, as it slowly starts trying to fit Beck into these simulations so as not to disrupt or alter them. This leads to him being put in some weird positions.

When Beck finally gets to the dream simulation that led the machine to malfunction, he finds a horrifying sight.

If Tron doesn’t stop, he’ll end up not just hurting his subconscious.

#tron#I’ve held onto this idea. FOR SO LONG. so I went a little insane#tronblr#tron uprising#tron beck#tron fanart#there’s so much I’ve written down about it hhhhghgh#the simulation of Tron fighting himself because he blames himself and never wants to be so ‘naive and hopeful’ ever again#bc that attitude led to nothing but betrayal and misery#going crazy#something something also foreshadowing for Rinzler#also also the outcome of Beck’s meddling with this harmful simulation leads to him getting hurt which is a metaphor for how programs#WILL get hurt if Tron lets his trauma fester and doesn’t ask for help in processing it#yeah#i ramble#art tag#tron 1982#tw strangling#tw strangulation#it’s not graphic at all but eh#tw eyestrain#eye strain tw#eye strain#cw: eyestrain#eyestrain

122 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NOTES FROM THE FRONT LINE (#132, APR 2012)

It’s generally accepted that Walter Murch (along with friend and colleague Ben Burtt redefined the role of the cinematic sound engineer, coining the term “Sound Designer” for Apocalypse Now (1979), which was foreshadowed by his “Sound Montage” credit for The Conversation (1974).

Murch later turned his hand to directing, helming Return to Oz, the 1985 sequel to the beloved classic. It was his friend George Lucas who offered him the opportunity to take the director’s chair again for The Clone Wars season four episode from the Umbaran quadrilogy, “The General.” Interview by J. W. Rinzler

Star Wars Insider: How did you first get invited to direct an episode of The Clone Wars?

Walter Murch: I heard about Bob Dalva, who’s a friend, film editor, director, and cameraman. George Lucas had asked him to be a guest director on the show (Season Two’s “The Deserter”) and I kept tabs with him, checking how it was going. He was having a great time doing it. I think it was a year later that George said, “What about you? Do you want to be a guest director?” Based upon the experience that Bob had, and my own general interest in the interface between art, story, and technology, I thought I would see what it was all about.

Did you choose a script from the four episodes of the Umbaran story arc?

They just said here it is. I didn’t get to choose. I think I would’ve been overwhelmed if I had to choose, because I didn’t know anything about the process other than what Bob and George had told me. It was much better just to get an assignment and not have to make a choice, weighing variables that I had no knowledge of at that time.

What did George tell you about the show?

Not much. He said, “It’s great, you’ll love it!” What he’s interested in with guest directors is people coming on board and injecting whatever it is that makes a metal into an alloy: a little extra something that’s not normally in the metal, but that helps to turn it into something else: iron into steel, brass into bronze, hopefully stronger. There are four directors on staff—very talented directors who are each working on three projects at once in various stages, whereas a guest director is only working on one thing and doesn’t hang around after the job is done. I wasn’t involved at all in the final animation. It’s just a very specific 12-week gig—to learn the software and produce the work.

George also wanted to bring in, with Bob and me and Duwayne Dunham—another guest director who has done two shows—someone who has experience in live action. George wants an infusion of a live-action sensibility into the process of doing animation, so it becomes scene-based rather than shot-based. Animation tends to be shot-based work because of the expense of producing animation; you want to minimize the amount of work, so shoot only what is absolutely necessary. Whereas with the zViz software (a proprietary software platform developed by George Lucas and Lucasfilm that helps directors compose shots), which is what we were working with, it doesn’t cost anything to keep the shot going, especially in a dialogue scene. It’s covering the dialogue the way you would cover a normal dialogue scene in live action from many different angles, which allows you to choose in the editing how the scenes will be constructed.

So you had 12 weeks. At this point was the script already written?

Yes, it was finished and, other than meeting at the end of the process, I never had any interaction with the writer. [Supervising director] ave Filoni did ask, “What do you think about the script? Any ideas?” In this story, the two clones, Fives and Hardcase, have to penetrate an alien airbase and there’s a perimeter fence around it. In the original script, they walked up to the fence and turned it off with some device they had. I thought we should make it a little harder, just to get a bit more action into it; also, if you can do everything with your own devices, it makes the opposition look weaker. So the whole idea of climbing up the tree, and then booby-trapping it to distract the guards —that was my contribution to the story.

So once you did the script, it went to the story reel phase using zViz. Was there anything in between those stages?

There was a lot of work already done in set and character design, all of which I inherited. They just said, “Here it is!” I slightly changed the nature of what some of the weird creatures were—that was another script idea I guess—I made the weird flying creatures into vultures so that they would try to eat the bodies of dead clone troopers. In the script they were just seen as passing clouds, but since they looked like vultures mated with manta rays, I thought, Let’s give them a personality and a purpose. What do these guys do? So that was another thing. I didn’t modify the look of the creatures, but I did modify what they did.

You then moved onto the zViz story reels.

I went to zViz class for the first two weeks. I had a one-on-one tutor and I was learning the software. Co-incident with that, in the afternoons, I started to play with the set and the characters, and reading the script, and working out how we were going to stage everything; just arranging the basic elements of the “soldier” aspect of the work, which is: “Here’s the army. There’s the enemy. Our army is moving in this direction. They’re coming from that direction. They’re in single-file, and so on.” At that stage, only basic camera parameters had been set, so I went through the script scene-by-scene and blocked it out using zViz. I had a team of four story artists who were going to be working with me—Bosco Ng and Dave Brickley would sometimes be standing next to me saying, “Don’t do that. It’s more efficient to do this,” just like when you learn to drive a car. You have an instructor there to prevent you from crashing. I got about two percent into using zViz. Maybe five percent. Maybe I would have been able—for the story reel—to do some actual story reel animation, but this particular show is so full of action that I left it to the artists that were working with me.

What was the next stage?

After the blocking? The story reel. I assigned scenes to the story artists and they would phone me up four hours later and say, “Want to take a look?” And that would give me other ideas and I’d make suggestions and they would work their way through the scenes.

As with live action, do you have to choose the “virtual camera lenses” you use?

Yes. I began to sketch that out in the plotting stage. But I generally left that up to the animators, except for a few specific places like that shot of the first emergence of the scorpion tank: I wanted that to be a telephoto lens.

Did you find it liberating?

Yes, it was. I felt insecure during the two weeks when I was learning the software and not knowing how much more I had to learn. If we had all the time in the world, it would’ve been different—but this is an ongoing series and you have to hit schedule milestones. And I was very happy with the work the story artists did; they saved my bacon a number of times when there were things I couldn’t quite figure out. Based on their own experience being animators and working on The Clone Wars, they knew what could be done and that would trigger ideas from me. So it was a very good collaboration with all four guys.

Did you have any involvement with the direction of the actors?

Yes, once we’d recorded and cut the temporary voices in. and then made any adjustments, we went down to Los Angeles and recorded the actual voices of the clones and Krell. So I was there for the final recording. It’s very important, I think, for the director of the recording.

The episode has a lot of action in it, but is also quite violent. There’s a scene where some Umbarans walk past and the clones shoot them in the head.

That was another idea I had. And another was the amount of stomping that the scorpion tanks do. There are many clones that get killed by being stepped on. This was an idea I came up with based on exploring the ability with zViz to articulate the character’s movement, like a puppet. The scorpion tanks are a six-legged mechanism. It wasn’t specified in the script what those legs could do—it just walked forward and shot. I thought it would be more interesting if it appeared to be alive in an animalistic sense and, working with Dave Brickley, we started tooling around with these creatures. We made them stand up on their hind legs, so to speak, and put the front legs up in the air. Once you did that, it was clear that it would be good.

These ideas arise spontaneously out of the directing process and if nobody stops me, then I’ll do them. It’s grisly—people killed by being stepped on, and the idea of finishing off this Umbaran pilot—and it begs the question. “If they didn’t shoot him, what were they going to do with him?” Then there’s the whole idea of these vulture creatures feeding on the flesh of clones. I plead guilty to the grisly parts of the story, or emphasizing them anyway.

Is that because you think kids today can handle it?

I think so, but I wasn’t thinking about the audience spedifically. It’s shown at eight o’clock at night, and I know that the viewing age ranges very wide. I thought it was my duty—I’d been invited in to do this stuff and they were looking for somebody from the outside. So I guess I was pushing the edge of the envelope. And I think that’s one of the very interesting things about the show. It gets into some pretty deep, philosophical waters about what an army is: Who are the soldiers in an army, and what are they really doing? Do they obey orders without thinking or are they obliged to think on their feet and countermand an order if they know a better way to do it and what’s the cost of that? How does identity emerge out of group of soldiers who, in this case, are literally bred to be the same. And yet different identities do emerge out of their DNA—how does that happen? How do you cohere as a military fighting force where the idea is to sublimate your identity and not be individuals? Once you start thinking about all that, you get into some pretty interesting areas.

It sounds like it intellectually engaged you.

Yes, it did. But all this is not specifically limited to my episode. That whole Umbaran arc in particular is about the assassination of a kind of Hitler. When do you kill the guy who’s supposedly your commanding officer? What he’s doing is wrong and against all military code, and yet you have to obey him. it’s a dilemma that the human species confronts over and over. I looked at maybe 12 other episodes in the course of 12 weeks. and I was really impressed with the range of subject matters and the implications of some of the ideas that were being explored.

Also, I was taken with the density of the storytelling in a 22-minute session; I would be watching one of these episodes, looking at the animation and being impressed with the style and the production design and all of that, and then the seven-minute moment, the commercial break, would come and I’d realize, wait a minute, that felt like 20 minutes not seven! It felt like a lot had happened and it had only been seven minutes. Each of these 22-minute episodes feels like an hour in terms of the visual and thematic complexity of the stuff that’s being explored. Those experiences quickly eliminated any sense that I was making a film for kids. But by the same token, Return to Oz, which is essentially a film for kids, also has some heavy-duty stuff in it. I think kids can take it.

Did you get to see your episode before it went to air?

Yes, but the first version I saw I thought the picture was way too dark. I would not have animated things the way I did if I had known it was going to be that dark. I had been told Umbara was a dark planet, but I didn’t know it was going to be that dark. There’s a saying in England: When you do live-action night shooting, you’ll get the question, “Where is this light coming from?” And the answer is, “That’s ‘Customer’s Moonlight.’” In other words, the audience paid to see the movie—the light is there to allow them to see what they paid for. But when I saw the aired version of “The General”, the darkness had been lightened. I don’t know what knobs they twirled, but there was much mom light. And yet it still looked like a dark planet. So I was much happier.

Is there anything that you’d like to have differently?

The Clone Wars animation is getting on good. particularly for certain characters. that I would like to see them move even more in a live-action sense. There’s still a tendency, especially in the story reel stage, to over-articulate body language. There are lots of hand gestures, kind of in a marionette sense, and you tend to fall into doing that because there is no facial animation at the story reel stage, only rudimentary changes from anger to joy. And with the clones wearing helmets, you don’t see any face, so there is a tendency to over-compensate with body-language. I think that may have been necessary in the early days when the animation wasn’t as sophisticated. Now it’s getting so good, it might be time to back off from the marionette aspect and treat them more like real people, real actors.

Do you think they should invest a little more in that?

Yes, but with some characters I think they’re already there! There’s a wonderfully evil female character Asajj Ventress. She’s fantastic—both as a character and how she’s animated. I love that character.

THE CINEMA OF WALTER MURCH

Walter Murch enrolled at the University of Southern California in 1965. In its School of Cinema, he met George Lucas, future writer/director John Milius, author Donald Glut (who penned the novelization of The Empire Strikes Back), Director of Photography Caleb Deschanel (who shot 1979’s More American Graffiti), and a host of other luminaries who came to prominence during the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. After Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola founded American Zoetrope, Murch helped edit and mix sound on the latter’s The Rain People (1969). His résumé soon filled out with a series of Lucas and Coppola projects: THX 1138 (1971), American Graffiti (1973), and The Godfather Part II (1974), before winning an Academy Award in 1980 for his sound design on Apocalypse Now. His subsequent credits include, among many others, Ghost (1990), The Talented Mister Ripley (1999), Cold Mountain (2003), Jarhead (2005) and The English Patient (1996), for which he netted Oscars for both film and sound editing.

#season 4#408#crew#insider#i132#the clone wars#guest directors#got real detailed into the process and the episode!

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

1, 2, 8, 13, 35, 38?

Rambling and whatnot below. Per the norm.

1.) Describe your comfort zone—a typical you-fic.

I don’t…know. I mean, I guess low action, minimal group dialogue, nothing too intense. Just peaks into serene moments. I’m not good at picking up where to start and stop, and how much backstory to give because I’m always one to overbuild a situation, but the quiet fluff moments where characters can interact in more intimate ways are my favorites. Also, if I can dump some garbled foreshadowing in there that no one but myself will understand, A+.

2.) Is there a trope you’ve yet to try your hand at, but really want to?

SOULMATES. I mean, I have one in the works, but it will probably never ever ever see the light of day. I guess I need to try my hand at a tiny drabble.

8.) Share a snippet from one of your favorite dialogue scenes you’ve written and explain why you’re proud of it.

Ah, there was a really cute/interesting little exchange where one of my OCs, Arpa, got compared to Rinzler from Tron, and they just…blew up about it. Like, “there’s a reason this suit is blue and black and not orange. I know who I fight for, thank you.” And it was just the dork flying their flag, like yep, technopath being compared to Tron, let me own this. But I think I deleted that…so…???

“If I remember correctly, you were the one with something up your ass last.” Hartley stirred the hot chocolate and took another sip.

“I mean, nobody really hates what he’s doing,” Leah said, putting the phone down. She popped open the box closest to her and fished out a piece of whatever was in it. “If anything, he’s helping the Flash by taking some of the minor cases out. It’s mostly been stuff dealing with the rougher parts of town, right?”

“Blowing a hole in a dumpster is not helping,” Cisco snorted. “Plus, didn’t you read about that meta at the airport? This dude showed up to help,” he kept on, sarcasm dripping from his voice, “and ended up sending The Flash flying into Interstate 274!”

“He-” Leah bit into…pork, sweet and sour pork, and brought a hand up to cover her mouth as she continued speaking. “He caught himself before he hit any cars though, didn’t he?”

“That’s not the point! M-h-his sui-ARGH!” Cisco let out an angry huff and brushed some hair back from his face as his lips pulled into a taunt frown.

“I think he’s helping, but suit yourself.” she muttered. “What else did you bring? Besides sweet and sour pork?”

Cisco muttered something angry and tossed a fortune cookie at her.

I don’t like the repeated words that I can see now and a few of the verbs I chose, but from all of my stuff that’s one of the best conversational pieces. It’s more…complex than just little to no dialogue tags, and to me, for the situation, it seemed very natural. It paints the tiniest bit of foreshadowing for a larger arc to come and kinda slips this certain character back into the narrative with the hint of redemption.

I wish there were something better, but a lot of what I write is tucked into long bits of narrative prose. I’m better at prose. It doesn’t help that I haven’t had a chance to write a real dialogue heavy scene since I really started to improve upon my writing. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

13.) What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever come across?

ACTION VERBS. Oh man, it’s such an easy trade up. That changed the way I wrote entirely. Instead of grabbing clumsily, try fumbled with. That kind of stuff. Also, filler words. I am the worst at filler words, and I most of the time refuse to follow that advice, but it is a good one. Let me have my filler words.

35.) Would you ever kill off a canon character?

I’m not entirely sure. I almost killed off Caitlin once, but instead chose to play the doppelganger card. I think if the situation called for it, I could. My brain seems content to just kill everyone off, so…

38.) Talk about a review that made your day.

Haaaa. I used to talk with someone every few days or so about my longfic, and for months I teased them about a certain aspect of foreshadowing. When it finally came to fruition, it went straight over their head. Just…FWOOSH. Typical for my writing. So I had to walk them through it but not give it away, and the reaction when they figured it out was just…priceless? Like, 5 minutes of silence followed by ‘I think I just died.’ If that counts as a review, that was fun.

There were also several sweet comments left on Let it Snow that varied from ‘you made me cry’ to more detailed ones that made me cry. Any review makes my day, honestly.

40 Questions — Meme for Fic Writers

1 note

·

View note