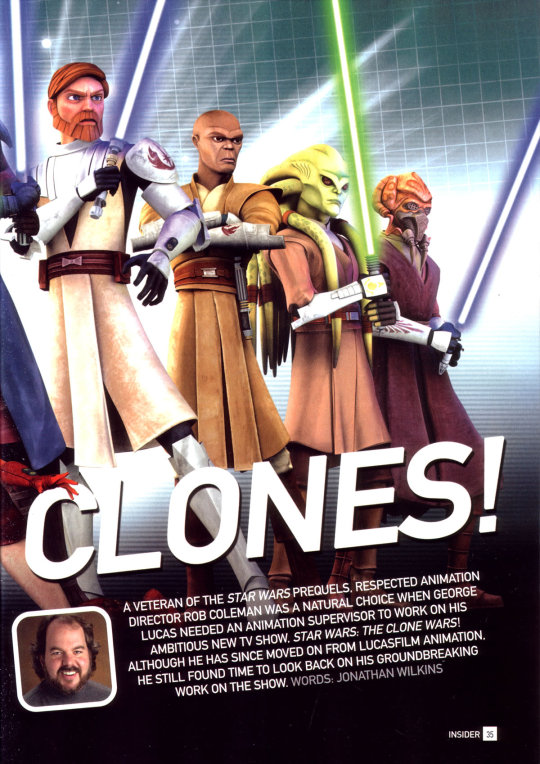

#guest directors

Photo

CREATING CLONES (#107, FEB 2009)

A veteran of the Star Wars prequels, respected animation director Rob Coleman was a natural choice when George Lucas needed an animation supervisor to work on his ambitious new TV show, Star Wars: The Clone Wars! Although he has since moved on from Lucasfilm animation, he still found time to look back on his groundbreaking work on the show. Words: Jonathan Wilkins

When did you first get involved in Star Wars: The Clone Wars?

I worked very closely with George Lucas on the prequel films and we had conversations about setting up an animation division while we were shooting Revenge of the Sith. That was around 2003.

I didn’t officially become involved until I completed all the animation on Revenge of the Sith. I started talking to Gail Currey, who I’d worked with at ILM [Industrial Light and Magic] and who was putting together Lucasfilm Animation at that point. She and George invited me to come aboard and help set it up. My first job in May 2005 was to fly over to Singapore to hold a presentation to help attract talent in order to build the studio there.

What are the day-to-day challenges of an animation consultant?

Dave Filoni, the series’ supervising director, and Catherine Winder, our launch producer, had both worked in animation before but had not worked in the Star Wars universe. George Lucas asked me to meet with them and immerse them in the world of Star Wars. The role of animation consultant came out of that early working relationship with Dave Filoni.

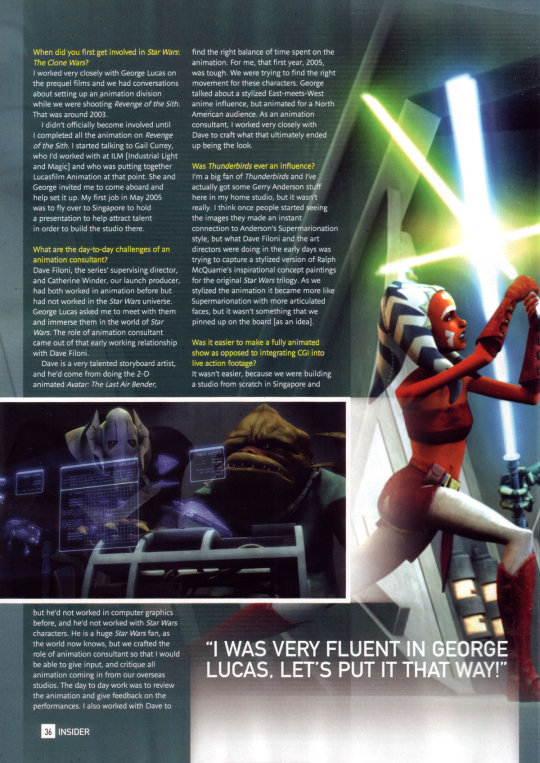

Dave is a very talented storyboard artist, and he’d come from doing the 2-D animated Avatar: The Last Airbender, but he’d not worked in computer graphics before, and he’d not worked with Star Wars characters. He is a huge Star Wars fan, as the world now knows, but we crafted the role of animation consultant so that I would be able to give input, and critique all animation coming in from our overseas studios. The day to day work was to review the animation and give feedback on the performances. I also worked with Dave to find the right balance of time spent on the animation. For me, that first year, 2005, was tough. We were trying to find the right movement for these characters. George talked about a stylized East-meets-West anime influence, but animated for a North American audience. As an animation consultant, I worked very closely with Dave to craft what that ultimately ended up being the look.

Was Thunderbirds ever an influence?

I’m a big fan of Thunderbirds and I’ve actually got some Gerry Anderson stuff here in my home studio, but it wasn’t really. I think once people started seeing the images they made an instant connection to Anderson’s Supermarionation style, but what Dave Filoni and the art directors were doing in the early days was trying to capture a stylized version of Ralph McQuarrie’s inspirational concept paintings for the original Star Wars trilogy. As we stylized the animation it became more like Supermarionation with more articulated faces, but it wasn’t something that we pinned up on the board [as an idea].

Was it easier to make a fully animated show as opposed to integrating CGI into live action footage?

It wasn’t easier, because we were building a studio from scratch in Singapore and teaching a very green, but very talented, group of people who had never worked at this level before.

I’d helped build the animation teams at ILM for years and it’s a long process. Once we had those established, actually doing the movies was easier because I had people who understood what it was to work at that level. Initially the TV series was harder because not only was I trying to immerse them in the world of Star Wars, I was training them on how to actually animate to the level I wanted.

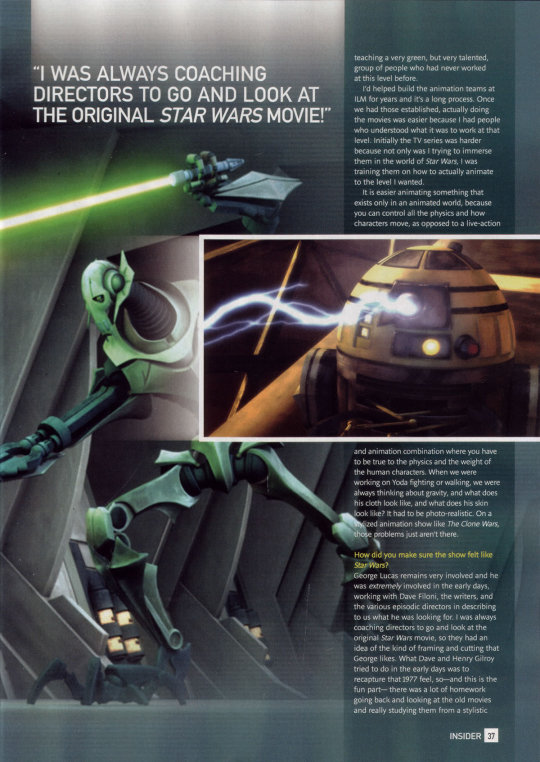

It is easier animating something that exists only in an animated world, because you can control all the physics and how characters move, as opposed to a live-action and animation combination where you have to be true to the physics and the weight of the human characters. When we were working on Yoda fighting or walking, we were always thinking about gravity, and what does his cloth look like, and what does his skin look like? It had to be photo-realistic. On a stylized animation show like The Clone Wars, those problems just aren’t there.

How did you make sure the show felt like Star Wars?

George Lucas remains very involved and he was extremely involved in the early days, working with Dave Filoni, the writers, and the various episodic directors in describing to us what he was looking for. I was always coaching directors to go and look at the original Star Wars movie, so they had an idea of the kind of framing and cutting that George likes. What Dave and Henry Gilroy tried to do in the early days was to recapture that 1977 feel, so—and this is the fun part—there was a lot of homework going back and looking at the old movies and really studying them from a stylistic and directing-choice point of view. We looked at camera choices, cutting choices. George uses a certain kind of lens and there is a certain kind of cutting that he does. Once you become well-versed in that, you can make him very happy. I’d worked side by side with him for so many years that I had an advantage over the other episodic directors. I already knew how to communicate with George. I was very fluent in George Lucas, let’s put it that way!

So you knew what to expect?

Yes. But I was also trying to find a balance. This is Dave Filoni’s show. Being asked to be the animation consultant and directing some episodes helped to move the series along. I went over and taught classes in Singapore. I ended up doing the Downfall of a Droid and Duel of the Droids episodes, which were the very first two shows to come out of Singapore. They wanted me to help shepherd them along, which I was happy to do. They are probably the roughest shows that we did, because they were the first two out of the gate. I’ve directed three more since then and they are much stronger because the team had more experience and more familiarity with the characters and the cameras than they did in those two episodes.

Is there anything you would change about them?

There is so much I would change! The hardest thing to do as a director is to say, “That’s good enough.” If you don’t start approving work, and you don’t have a vision of what you want the show to look like, it will never be finished! I think where I was successful with George was that I was always able to step into the river and say, “That’s good enough.” The river keeps flowing past you, and you’ll see better work coming later on, but you have to stick with what you did before. There are certainly shots in those episodes that I would love to have back, but I don’t regret it because we had to deliver the show.

The show is animated in about a fifth of the time of a feature film, so we didn’t get the subtlety and fidelity in the faces and lip-synching in those earlier shows. Later episodes are far better, because I was able to spend time and really hone the team’s awareness of what was important in the face. In those earlier episodes it was all hands on deck!

How is an episode put together?

Dave Filoni is the supervising director. He works directly with George Lucas and the writers to create an overall plan for all of the episodes each season. He’s there at the beginning with the producer. It usually takes a couple of days to a week, and they plan out in very rough form what will happen.

They come up with episode synopses which are about a paragraph long for each episode, and describe what happens to the heroes, what the problems are, and what gets solved.

The writing team divides up the episodes between them and they start writing. Once the first drafts come in, Dave and George read them and make notes and decisions. Then they start choosing episodes that are actually going to be made. That’s when an episodic director gets involved. They’d call the director in and say, “Rob we’ve got an R2-D2 show coming up”—in my case it was a two parter—“and here’s an early draft”.

The director gives notes, as a fresh pair of eyes to the story. Then in maybe a few days or a week a shooting draft is ready. At that point, the episodic director works with the storyboard artists, doing storyboards on paper or computer, or in my case going straight to 3-D computer graphics to map out what the scenes are going to look like. You spend maybe six weeks mapping out the whole show, so you have a version of the show done in storyboards or in computer animatics that describes visually what the show’s going to look like.

There might be a still image of Anakin standing, and I would record people in the studio for temp dialogue and work with editor Jason Tucker to cut it all together, so it’s to length, but nothing’s animated at that stage, and nothing’s got color. It’s usually just black and white or gray. I’d present that to George, and then he would give me notes. I’d do a revision on that and present it for a final look. Then George would sign off on it.

As an episodic director you “package up the show.” This means you make shot-by-shot directing notes on what you want to see happening. You might say Anakin walks onto the bridge of the Twilight. Ahsoka’s sitting there with Artoo, and turns to him and says the line. You give director points, like “Anakin’s angry at this point because he’s just come from such-and-such a place and he’s irritated by this or that.” When the animators get it in Singapore they understand, because otherwise it could be animated completely out of context. Animators might get five shots in a row, but they may not know what’s come before so it’s very important as a director that you tell them. Normally an episodic director would then leave that process and go onto the next show, but I then critiqued not only the animation coming in for my show, but also for the other four episodic directors.

Were there any examples where it was completely off and they had to start again?

Yes, of course. That was the biggest challenge. It was something I had to get used to. I’d spent 12 years at ILM with my animation crew down the hallway. I could walk into their offices and talk to them at anytime. Now I was in a situation where my animators were on the far side of the Pacific Ocean and I had to wait hours to talk to them because of the time difference! Although they all spoke English beautifully, there were occasionally communication issues. To be fair to them, I was used to working with some of the most experienced animators in the world and had a shorthand with them. Now I was dealing with some very talented up-and-coming people, but they didn’t have the vocabulary that I was used to. I had to fly over there a few times, and then we got better and better. You’ll see as the season goes on, the animation really improves—but that was a learning process for me.

Your episodes feature Ron Perlman as Gha Nachkt—what was he like to work with?

I never got to meet him! Dave Filoni gets all the fun working with the actors. As the supervising director, he directs all the voice talent for all of the shows and it’s all done in Los Angeles. I’m holding the fort critiquing all the animation coming in from overseas, and he’s down in L.A. meeting Ron Perlman! Dave did get me an autograph though! Ron did a great job in the show. I didn’t meet many of the voice talent for Star Wars. I never got to meet Andy Secombe, who did the voice of Watto. I never met Brian Blessed who played Boss Nass, so it’s not totally out of the norm. I did get to spend so much time with Frank Oz, who played Yoda, that he’s become a friend of mine, so that’s an added bonus of being the animation director!

What are your favorite scenes from the show?

I really like the writing on those shows, and to be able to see Artoo becoming a tougher little guy was a lot of fun for me. I would say the scene - with him fighting with the other droid was a favorite. It was fun to figure out how to shoot that and what was going to happen there. The writers had outlined the entire fight, but as a director you get to pick all the angles, which was fun. The assassin droids coming to life in the hold of the ship was really fun to direct, and to invent how we saw the IG-88s jumping around. We’d only ever seen them standing still in The Empire Strikes Back, so to get them to jump and leap an. spin their heads around was a highlight for me.

How did you come up with that extreme style of complicated movements?

I was trying to go with the opposite of what the character looked like. If you have a toy or you saw it in the movies, he’s just standing there not doing anything. He just looks so rigid, and I thought from an animator’s point of view “Let’s take that rigidity and just throw it away!” Let’s really surprise the fans, so that when these thing leap up they’re actually much more flexible than their “Tin Man” appearance would allude to. What I was able to do is make it into a vertical fight. I didn’t want to just have a fight on the ground; we’ve seen that so many times. I had this set that had been already outlined in the script where it was described as this big warehouse with shelves upon shelves of droid parts. I went up to the Home Depot store and walked around the aisles. I was thinking, “Wouldn’t it be cool to look up and see those droids jumping and leaping from side to side?” So that’s how that started. I thought that was just a neat image.

There’s some very creative lighting schemes, such as the sequence where Anakin awakens in the medical bay.

That was harder in the early days when we were doing those droid episodes. Andrew Harris was the Lighting Supervisor for those. All of the color and ideas for the lighting comes through the art department, which Dave Filoni supervises. I can’t recall exactly who did the concept paintings for those early shows, but they did some beautiful work. I inherited such beautiful paintings from those guys that I did very few tweaks from a directorial point of view. I really loved what they were doing artistically. The paintings had come with that bleached-out art direction, and I relied heavily on Andrew to pull that off with the Singapore crew.

It’s quite surprising to see that sort of detail in an animated show.

You’ve touched on something that was very important to George, Dave, and myself. I keep using the word “shoot” when I talk about making the show because we kept talking about it that way. We thought about it as shooting it with real cameras. This is still an animated world that exists in our imaginations, but we used cinematic tricks that we would use if it were a live-action film. We see lens-flares and exposures as if you’re in a dark room and shooting up to a bright window so that everything goes into silhouette. George loves that kind of stuff. So we used the language of real film and applied it to the show

What kind of scenes do you prefer working on? Big action sequences, like space battles, or mailer, character-based scenes?

I don’t actually have a preference. I think every episode or movie has to have a balance. I tended to spend most of my brain power on the quieter character-based scenes, because it was imperative that the animated characters came up to the same level as the real actors. But it was certainly fun to work on the opening space battle in Revenge of the Sith.

These TV shows have a lot of action because of the audience we’re going for, but it’s a real blend. There’s a Mace Windu episode that I directed that’s coming up later in the season, and that was a real combination of action and character. I’m really proud of that episode. It turns out that they liked it enough to make it the season finale. We were really doing well by the time we got to that show. It’s a real blend of big action sequences and smaller character pieces.

I think a strong director is someone who is able to play to people’s strengths, because not everybody is good at both of those kinds of scenes. There were specific animators I would give action work to, and other animators I would give acting to, and there’s a smaller group who can handle both.

How many episodes did you direct?

I did three more episodes after the two we’ve talked about. Two of them will be seen in this first season and one of them has been moved to the second season. I’m proud of the droid ones, but there are better ones coming! They do have guest director spots that come up every once and a while, and I would certainly be keen to direct another one. It’s all to do with timing and schedule.

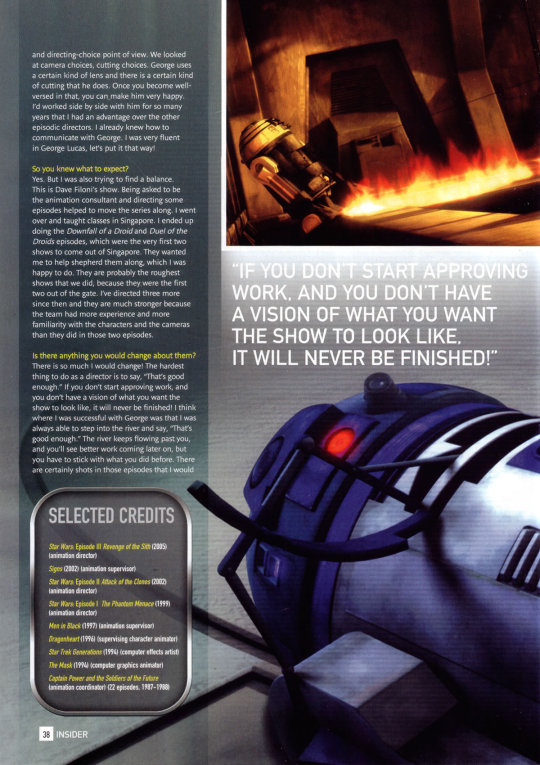

SELECTED CREDITS

Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith (2005) (animation director)

Signs (2002) (animation supervisor)

Star Wars: Episode II Attack of the Clones (2002) (animation director)

Star Wars: Episode I The Phantom Menace (1999) (animation director)

Men in Black (1997) (animation supervisor)

Dragonheart (1996) (supervising character animator)

Star Trek Generations (1994) (computer effects artist)

The Mask (1994) (computer graphics animator)

Captain Power and the Soldiers of the Future (animation coordinator) (22 episodes, 1987-1988)

SPOTTING COLEMAN?

Coleman Trebor one of the many Jedi slain by Count Dooku in Attack of the Clones, is named after Rob Coleman. The man has cameos in

Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith (2005) Opera house patron

Star Wars: Episode I The Phantom Menace (1999) Podrace spectator in Jabba’s private box

#Rob Coleman#i107#insider#crew#the clone wars#guest directors#<-(1 of 3)#detailed insights about the process of making an episode!

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Americanos da Guest Directors apresentam álbum de estreia

https://zinemusical.wordpress.com/2023/09/08/americanos-da-guest-directors-apresentam-album-de-estreia/

#Guest Directors#shoe gaze#post shoe gaze#dream pop#alternativemusic#alternativerock#gary thorstensen#tad#zine musical

0 notes

Text

SAHAR: Imogen got a boyfriend last year and then stopped texting me.

IMOGEN: ...Er, no! You stopped texting me!

#one thing about the directors they're going to put this girl in lesbian lighting!!!#guest starring a lot of ben because this is his song too 💛 seek help king. please#anyway. i havent made a gifset in 1 billion years please be nice#heartstopper#osemanverse#heartstopper netflix#hstv#imogen heaney#sahar zahid#ben hope#imogen x sahar#good luck babe#good luck babe!#my edits#my gifsets#heartstopperedit#op#alice oseman#jesus that's a lot of tags#chappell roan

532 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bear s2ep6 is what succession is but for poor people

#this was almost like every end of the year party i ever had with my dad's family at my grandmas house#also fucking stellar job to the director the casting director the writers and producers#the guest actors like thats a lot of good fucking actors my god#i know jamie lee getting a nom as best guest actress#the bear fx#carmen berzatto#natalie berzatto#jeremy allen white#succession hbo

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greta Gerwig was on TCM picking films tonight and talked about inspiration/influences for Barbie.

She explained how “authentic artificiality” was the catchphrase for filming Barbie and named The Red Shoes as one of the films that captured that so well.

And after the film showing, she expanded on that catchphrase and how it influenced Barbie:

“I wanted it to feel like…and we always asked ourselves…how would they do this in 1959? If we were making it in 1959, would you use front projection, rear projection, how would we composite this shot, what would be the thing that we’d use then. Because to me I wanted to give myself the constraints of what a movie world is. Whatever Barbieland was was a sound stage, that it had a lid, it had an edge. And we looked at different versions of the design too, where we would see a corner joined at the end of the stage. Because I wanted that sense of being contained in a box. There’s so many examples in The Red Shoes where you both feel the edge of what the painting is but then you can also see the illusion and depth that it creates. And it was that type of juxtaposition I was interested in.”

She also named two easter eggs in Barbie for any Red Shoes fans out there:

Ken’s cateye sunglasses are inspired by the glasses on Lermontov in the train scene.

The scene Barbie walks up to Kate McKinnon’s house is shot to mimic the scene where Vicki walks up to Lermontov’s mansion in that great big dress.

She kept mentioning the “handmade” aspect of the visual in The Red Shoes. So this comment really resonated for me:

“There’s something exuberant about Powell and Pressburger’s joy of making. It feels like, ‘Well, why don’t we try it like this? Let’s make it like this.’ It feels like it gets at the heart of what I was hoping for Barbie, which…at its heart—it’s play. It has that play of cinema that I love.”

It’s a fitting statement for a movie about a child’s toy and extends to the wider realms of creative pursuits, where real life pressures often constrain child-like play and we lose the joy of making we once had.

Don’t forget the play aspect of creativity. At heart, we’re all still kids with our paint sets and dolls having fun making things and telling stories.

#greta gerwig#barbie#tcm#the red shoes#powell and pressburger#classic film#women directors#quality film meta on tcm guest picks night#the other film she picked was philadelphia story btw so 🎯#i havent seen barbie yet but thought this was interesting#probably increased my probablity of watching it 100%#films#the philadelphia story#my txt#creativity#inspiration#2023

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

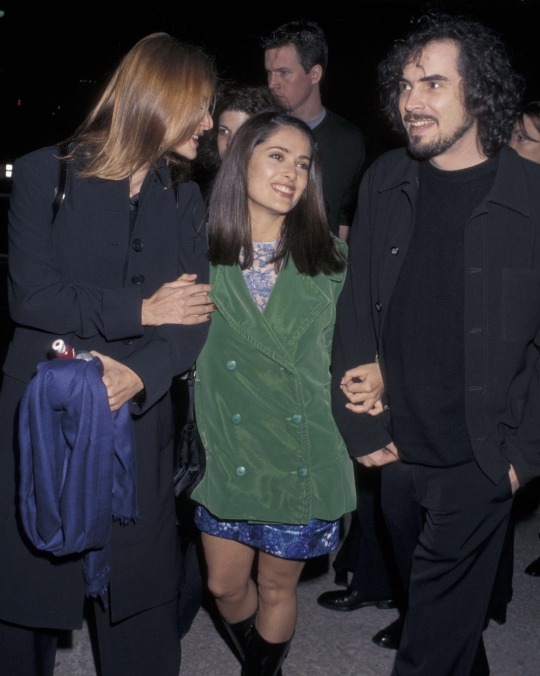

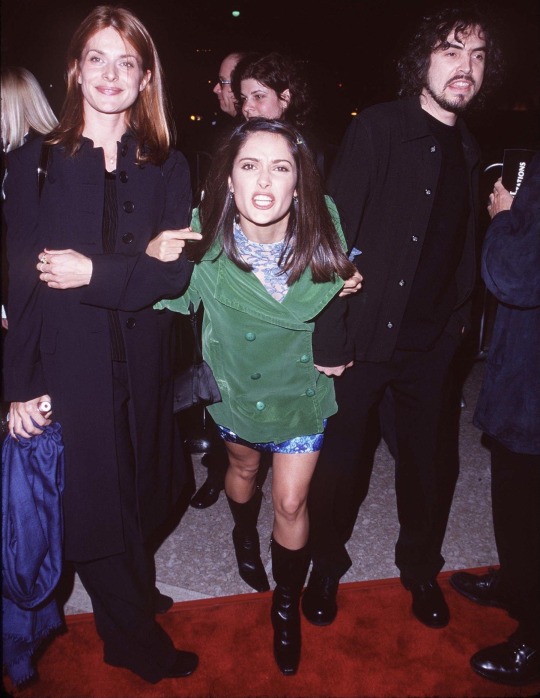

Nastassja Kinski, Salma Hayek, and Alfonso Cuarón attend the premiere of Great Expectations, 1998. Photographed by Steve Granitz.

#the press info didn’t know who alfonso was and labeled him as GUEST when he’s director of the movie that’s premiering#nastassja kinski#salma hayek#alfonso cuaron#alfonso cuarón#1998#1990s#steve granitz

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

#brittany snow#jaspre guest#Christina Grasso#parachute#love these ladies#director brittany snow#she is a boss#because she’s beautiful

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael Craze pops up as Vince Kelly, a teenage runaway from a borstal centre, in Gideon's Way: Boy With Gun (1.23, ITC, 1966)

#fave spotting#michael craze#ben jackson#doctor who#gideon's way#1966#boy with gun#itc#a relatively rare fave spotting! outside of his DW work‚ Mike didn't make a huge amount of appearances in cult tv‚ at least not many that#survive or are easily seen; he'd previously starred in Target Luna‚ a completely lost serial‚ but didn't return when the show carried on as#Pathfinders in Space (oddly‚ perhaps because of a change of director‚ every single returning character was recast) and beyond#there were also episodes of Dixon pf Dock Green and Armchair Theatre but these are also in all likelihood lost tv; others‚ like an ep of#Hammer's sci fi anthology Journey to the Unknown‚ are frustratingly unavailable to the average viewer (I was really hoping Network would#do something with JttU after they announced an agreement with Hammer but alas it wasn't to be)#mike would have been about 22 when filming this ep (around May '65) but was still largely playing juvenile parts as here#(his age isn't given but as a borstal runaway he's clearly intended to be a teen); this aired in feb or march '66 in most regions‚ by which#time he had presumably been cast in DW (or very near to it; he'd debut in The War Machines in June of that year)#DW would act as a sort of transition for Craze from youth parts into adult roles (i mean Ben's own age is debatable but I'd say he's surely#meant to be at least 18?). there'd be some more guest spots and a few horror films to come (he was a regular collaborator with Norman#J. Warren) but he doesn't pop up with the regularity of many other Who companions so this was a lovely little surprise (zero memory of him#being in it from when i first watched years ago)

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

English added by me :)

#想做个快乐的小废物~ 混吃混喝被照顾~ = new rent free sound bite#douyin#video#tiktok#i LOVE format changes....yes.... special guest director(s) for the new episode of my favorite tv show....#酱油白米饭#flashing

187 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NOTES FROM THE FRONT LINE (#132, APR 2012)

It’s generally accepted that Walter Murch (along with friend and colleague Ben Burtt redefined the role of the cinematic sound engineer, coining the term “Sound Designer” for Apocalypse Now (1979), which was foreshadowed by his “Sound Montage” credit for The Conversation (1974).

Murch later turned his hand to directing, helming Return to Oz, the 1985 sequel to the beloved classic. It was his friend George Lucas who offered him the opportunity to take the director’s chair again for The Clone Wars season four episode from the Umbaran quadrilogy, “The General.” Interview by J. W. Rinzler

Star Wars Insider: How did you first get invited to direct an episode of The Clone Wars?

Walter Murch: I heard about Bob Dalva, who’s a friend, film editor, director, and cameraman. George Lucas had asked him to be a guest director on the show (Season Two’s “The Deserter”) and I kept tabs with him, checking how it was going. He was having a great time doing it. I think it was a year later that George said, “What about you? Do you want to be a guest director?” Based upon the experience that Bob had, and my own general interest in the interface between art, story, and technology, I thought I would see what it was all about.

Did you choose a script from the four episodes of the Umbaran story arc?

They just said here it is. I didn’t get to choose. I think I would’ve been overwhelmed if I had to choose, because I didn’t know anything about the process other than what Bob and George had told me. It was much better just to get an assignment and not have to make a choice, weighing variables that I had no knowledge of at that time.

What did George tell you about the show?

Not much. He said, “It’s great, you’ll love it!” What he’s interested in with guest directors is people coming on board and injecting whatever it is that makes a metal into an alloy: a little extra something that’s not normally in the metal, but that helps to turn it into something else: iron into steel, brass into bronze, hopefully stronger. There are four directors on staff—very talented directors who are each working on three projects at once in various stages, whereas a guest director is only working on one thing and doesn’t hang around after the job is done. I wasn’t involved at all in the final animation. It’s just a very specific 12-week gig—to learn the software and produce the work.

George also wanted to bring in, with Bob and me and Duwayne Dunham—another guest director who has done two shows—someone who has experience in live action. George wants an infusion of a live-action sensibility into the process of doing animation, so it becomes scene-based rather than shot-based. Animation tends to be shot-based work because of the expense of producing animation; you want to minimize the amount of work, so shoot only what is absolutely necessary. Whereas with the zViz software (a proprietary software platform developed by George Lucas and Lucasfilm that helps directors compose shots), which is what we were working with, it doesn’t cost anything to keep the shot going, especially in a dialogue scene. It’s covering the dialogue the way you would cover a normal dialogue scene in live action from many different angles, which allows you to choose in the editing how the scenes will be constructed.

So you had 12 weeks. At this point was the script already written?

Yes, it was finished and, other than meeting at the end of the process, I never had any interaction with the writer. [Supervising director] ave Filoni did ask, “What do you think about the script? Any ideas?” In this story, the two clones, Fives and Hardcase, have to penetrate an alien airbase and there’s a perimeter fence around it. In the original script, they walked up to the fence and turned it off with some device they had. I thought we should make it a little harder, just to get a bit more action into it; also, if you can do everything with your own devices, it makes the opposition look weaker. So the whole idea of climbing up the tree, and then booby-trapping it to distract the guards —that was my contribution to the story.

So once you did the script, it went to the story reel phase using zViz. Was there anything in between those stages?

There was a lot of work already done in set and character design, all of which I inherited. They just said, “Here it is!” I slightly changed the nature of what some of the weird creatures were—that was another script idea I guess—I made the weird flying creatures into vultures so that they would try to eat the bodies of dead clone troopers. In the script they were just seen as passing clouds, but since they looked like vultures mated with manta rays, I thought, Let’s give them a personality and a purpose. What do these guys do? So that was another thing. I didn’t modify the look of the creatures, but I did modify what they did.

You then moved onto the zViz story reels.

I went to zViz class for the first two weeks. I had a one-on-one tutor and I was learning the software. Co-incident with that, in the afternoons, I started to play with the set and the characters, and reading the script, and working out how we were going to stage everything; just arranging the basic elements of the “soldier” aspect of the work, which is: “Here’s the army. There’s the enemy. Our army is moving in this direction. They’re coming from that direction. They’re in single-file, and so on.” At that stage, only basic camera parameters had been set, so I went through the script scene-by-scene and blocked it out using zViz. I had a team of four story artists who were going to be working with me—Bosco Ng and Dave Brickley would sometimes be standing next to me saying, “Don’t do that. It’s more efficient to do this,” just like when you learn to drive a car. You have an instructor there to prevent you from crashing. I got about two percent into using zViz. Maybe five percent. Maybe I would have been able—for the story reel—to do some actual story reel animation, but this particular show is so full of action that I left it to the artists that were working with me.

What was the next stage?

After the blocking? The story reel. I assigned scenes to the story artists and they would phone me up four hours later and say, “Want to take a look?” And that would give me other ideas and I’d make suggestions and they would work their way through the scenes.

As with live action, do you have to choose the “virtual camera lenses” you use?

Yes. I began to sketch that out in the plotting stage. But I generally left that up to the animators, except for a few specific places like that shot of the first emergence of the scorpion tank: I wanted that to be a telephoto lens.

Did you find it liberating?

Yes, it was. I felt insecure during the two weeks when I was learning the software and not knowing how much more I had to learn. If we had all the time in the world, it would’ve been different—but this is an ongoing series and you have to hit schedule milestones. And I was very happy with the work the story artists did; they saved my bacon a number of times when there were things I couldn’t quite figure out. Based on their own experience being animators and working on The Clone Wars, they knew what could be done and that would trigger ideas from me. So it was a very good collaboration with all four guys.

Did you have any involvement with the direction of the actors?

Yes, once we’d recorded and cut the temporary voices in. and then made any adjustments, we went down to Los Angeles and recorded the actual voices of the clones and Krell. So I was there for the final recording. It’s very important, I think, for the director of the recording.

The episode has a lot of action in it, but is also quite violent. There’s a scene where some Umbarans walk past and the clones shoot them in the head.

That was another idea I had. And another was the amount of stomping that the scorpion tanks do. There are many clones that get killed by being stepped on. This was an idea I came up with based on exploring the ability with zViz to articulate the character’s movement, like a puppet. The scorpion tanks are a six-legged mechanism. It wasn’t specified in the script what those legs could do—it just walked forward and shot. I thought it would be more interesting if it appeared to be alive in an animalistic sense and, working with Dave Brickley, we started tooling around with these creatures. We made them stand up on their hind legs, so to speak, and put the front legs up in the air. Once you did that, it was clear that it would be good.

These ideas arise spontaneously out of the directing process and if nobody stops me, then I’ll do them. It’s grisly—people killed by being stepped on, and the idea of finishing off this Umbaran pilot—and it begs the question. “If they didn’t shoot him, what were they going to do with him?” Then there’s the whole idea of these vulture creatures feeding on the flesh of clones. I plead guilty to the grisly parts of the story, or emphasizing them anyway.

Is that because you think kids today can handle it?

I think so, but I wasn’t thinking about the audience spedifically. It’s shown at eight o’clock at night, and I know that the viewing age ranges very wide. I thought it was my duty—I’d been invited in to do this stuff and they were looking for somebody from the outside. So I guess I was pushing the edge of the envelope. And I think that’s one of the very interesting things about the show. It gets into some pretty deep, philosophical waters about what an army is: Who are the soldiers in an army, and what are they really doing? Do they obey orders without thinking or are they obliged to think on their feet and countermand an order if they know a better way to do it and what’s the cost of that? How does identity emerge out of group of soldiers who, in this case, are literally bred to be the same. And yet different identities do emerge out of their DNA—how does that happen? How do you cohere as a military fighting force where the idea is to sublimate your identity and not be individuals? Once you start thinking about all that, you get into some pretty interesting areas.

It sounds like it intellectually engaged you.

Yes, it did. But all this is not specifically limited to my episode. That whole Umbaran arc in particular is about the assassination of a kind of Hitler. When do you kill the guy who’s supposedly your commanding officer? What he’s doing is wrong and against all military code, and yet you have to obey him. it’s a dilemma that the human species confronts over and over. I looked at maybe 12 other episodes in the course of 12 weeks. and I was really impressed with the range of subject matters and the implications of some of the ideas that were being explored.

Also, I was taken with the density of the storytelling in a 22-minute session; I would be watching one of these episodes, looking at the animation and being impressed with the style and the production design and all of that, and then the seven-minute moment, the commercial break, would come and I’d realize, wait a minute, that felt like 20 minutes not seven! It felt like a lot had happened and it had only been seven minutes. Each of these 22-minute episodes feels like an hour in terms of the visual and thematic complexity of the stuff that’s being explored. Those experiences quickly eliminated any sense that I was making a film for kids. But by the same token, Return to Oz, which is essentially a film for kids, also has some heavy-duty stuff in it. I think kids can take it.

Did you get to see your episode before it went to air?

Yes, but the first version I saw I thought the picture was way too dark. I would not have animated things the way I did if I had known it was going to be that dark. I had been told Umbara was a dark planet, but I didn’t know it was going to be that dark. There’s a saying in England: When you do live-action night shooting, you’ll get the question, “Where is this light coming from?” And the answer is, “That’s ‘Customer’s Moonlight.’” In other words, the audience paid to see the movie—the light is there to allow them to see what they paid for. But when I saw the aired version of “The General”, the darkness had been lightened. I don’t know what knobs they twirled, but there was much mom light. And yet it still looked like a dark planet. So I was much happier.

Is there anything that you’d like to have differently?

The Clone Wars animation is getting on good. particularly for certain characters. that I would like to see them move even more in a live-action sense. There’s still a tendency, especially in the story reel stage, to over-articulate body language. There are lots of hand gestures, kind of in a marionette sense, and you tend to fall into doing that because there is no facial animation at the story reel stage, only rudimentary changes from anger to joy. And with the clones wearing helmets, you don’t see any face, so there is a tendency to over-compensate with body-language. I think that may have been necessary in the early days when the animation wasn’t as sophisticated. Now it’s getting so good, it might be time to back off from the marionette aspect and treat them more like real people, real actors.

Do you think they should invest a little more in that?

Yes, but with some characters I think they’re already there! There’s a wonderfully evil female character Asajj Ventress. She’s fantastic—both as a character and how she’s animated. I love that character.

THE CINEMA OF WALTER MURCH

Walter Murch enrolled at the University of Southern California in 1965. In its School of Cinema, he met George Lucas, future writer/director John Milius, author Donald Glut (who penned the novelization of The Empire Strikes Back), Director of Photography Caleb Deschanel (who shot 1979’s More American Graffiti), and a host of other luminaries who came to prominence during the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. After Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola founded American Zoetrope, Murch helped edit and mix sound on the latter’s The Rain People (1969). His résumé soon filled out with a series of Lucas and Coppola projects: THX 1138 (1971), American Graffiti (1973), and The Godfather Part II (1974), before winning an Academy Award in 1980 for his sound design on Apocalypse Now. His subsequent credits include, among many others, Ghost (1990), The Talented Mister Ripley (1999), Cold Mountain (2003), Jarhead (2005) and The English Patient (1996), for which he netted Oscars for both film and sound editing.

#season 4#408#crew#insider#i132#the clone wars#guest directors#got real detailed into the process and the episode!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know your nerd cred is rock-solid when you get to rehearsal, say hi to the guest choral director, and he starts telling you about a performance of the Fauré Requiem he recently attended where for some reason they used nineteenth-century French Latin diction

#choir stuff#i'm so proud#honestly i love all three of the guest directors we've had#idek which one i like best or am rooting for#although i guess that means i'll be happy with the outcome regardless#but i will miss the other two!

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

is JCC the buddie writer?

JCC is Juan Carlos Coto, he's been a writer for most of the show's run (season 2 onward). You can check here to see the episodes he's worked on so far: https://www.tumblr.com/911bts/743248556205408256/7x02-and-7x03-were-written-and-directed-by-the?source=share

You'll see that most of these episodes have a buddie moment or are heavily centered on Buck and/or Eddie. He's not the ONLY buddie writer, but he has been responsible for a lot of them, along with Lyndsey Beaulieu, Andrew Meyers, Taylor Wong, and, of course, Tim Minear. (You can find lists of all their previous episodes on @911bts).

We also have prominent "buddie" directors coming back as well, including John J. Gray (who wrote 2x04 Stuck and directed 6x12 Recovery ((ie. Buck falls asleep on Eddie's couch)), Brenna Malloy (who directed 4x13 Suspicion aka the gayest shooting scene on the planet), and Bradley Buecker (who directed 3x02 Sink or Swim aka Buck&Chris in the tsunami, 5x02 Desperate Times aka Eddie's comphet panic attacks, and 6x10 In A Flash aka Eddie pulling Buck UP after the lightning strike and "DO MORE!").

I was telling Zee yesterday the only time Juan Carlos Coto wrote an episode that I was less than thrilled with (at least when it comes to Buck and Eddie) is 6x17 Love is in the Air. But upon rewatching several times, I changed my opinion. Love is in the Air was interesting because it put both Buck and Eddie with Random Love Interests but also at the same time very much slapped the label of "THIS IS NOT THE RIGHT ONE FOR THEM" on it. So I'mma give him the benefit of the doubt because he had to adhere to what KR & Fox wanted and it really seemed like he did his best to adhere by what his bosses wanted while still putting several fail-safes in both Bucktalia and Eddiemarisol. He gave us all the red flags with Natalia, and also very clearly spelled out that Eddie wants to date Marisol for the wrong reasons (trying to recreate his last toxic marriage with Shannon, dating her just cuz she's there, and still feeling pressured to date in general). Man said I can't save this trainwreck of an almost-series finale, but the least I can do is give these characters fail-safes so the fans know these aren't their endgames even though it might SEEM like it.

Now, back under Tim, and with (hopefully) the green light from ABC, I'm thinking the writers/directors for season 7 can go absolutely apeshit on the buddie scenes. Maybe even sprinkle in a lil canon buddie just as a treat because we've all been such patient baby birds waiting for mama bird's backwash, ya know?

#ask#911 abc#buddie#speculation#this in no way encompasses all of the writers/directors who've contributed big time to buddie#just scrolling through wikipedia there are plenty of recurring/ guest writers/directors who have created some of the best buddie episodes#that just goes to show how much those who are responsible for creating this show care for buddie and work hard to develop them well

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“While it may be hip to ‘blaze it’, please refrain from dabbling in illicit, questionable substances. Such infractions will be met with swift disciplinary action.”

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

KIM JAE WOOK IS F*CKING RETURNING TO US WE ARE GOING TO HAVE CONTENT FROM THIS MAN I CAN BREATHE AGAIN

#tv: tangeum#song of the geomungo: golden swallow#song of the geomungo golden swallow#tangeum#kim jae wook#kim jae uck#kdrama#local gay watches k-dramas.txt#it's as a supporting role tho so i am cryingggg#but it's a dark role apparently??? just art centered??? like if Ryan Gold had something extremely wrong with him and just went batsh*t#in the morals department plus he gets to be royalty. pathetic wet noble mess of a man giving off Scholar Who Walks The Night!Soo Hyuk vibes#mess of a man (says local gay who still has not seen SWWTN)#also it's the same director that worked on Voice S1 The Guest and Money Heist. God pls let this production go through i need it#(says local gay who also still has not seen any of the latter shows)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone in a video I'm watching pointed out how weird it is that the federation characters never react to the smell of Klingon disruptor fire and the worst part is that he's right. Because yeah, the particles left behind by recently vaporized corpses would smell really bad. I guess I could see Klingons' lack of a reaction as either them being used to it or a cultural value but for non-Klingons it does seem odd. Why am I being asked to think about this in the sfx commentary for a phase ii episode

#also the sfx guy's shade towards the guest director ramping up in intensity over the course of the video is hilarious#star trek#original post

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brittany Snow Jaspre Guest and Christina Grasso at the Parachute Screening in NYC

#brittany snow#jaspre guest#Christina Grasso#parachute#director brittany snow#she is stunning#so cute

21 notes

·

View notes