#steven johnson

Text

It is August 1854, and London is a city of scavengers. Just the names alone read now like some kind of exotic zoological catalogue: bone-pickers, rag-gatherers, pure-finders, dredgermen, mud-larks, sewer-hunters, dustmen, night-soil men, bunters, toshers, shoremen. These were the London underclasses, at least a hundred thousand strong. So immense were their numbers that had the scavengers broken off and formed their own city, it would have been the fifth-largest in all of England. But the diversity and precision of their routines were more remarkable than their sheer number. Early risers strolling along the Thames would see the toshers wading through the muck of low tide, dressed almost comically in flowing velveteen coats, their oversized pockets filled with stray bits of copper recovered from the water's edge. The toshers walked with a lantern strapped to their chest to help them see in the predawn gloom, and carried an eight-foot-long pole that they used to test the ground in front of them, and to pull themselves out when they stumbled into a quagmire. The pole and the eerie glow of the lantern through the robes gave them the look of ragged wizards, scouring the foul river's edge for magic coins. Beside them fluttered the mud-larks, often children, dressed in tatters and content to scavenge all the waste that the toshers rejected as below their standards: lumps of coal, old wood, scraps of rope.

Above the river, in the streets of the city, the pure-finders eked out a living by collecting dog shit (colloquially called “pure”) while the bone-pickers foraged for carcasses of any stripe. Below ground, in the cramped but growing network of tunnels beneath London's streets, the sewer-hunters slogged through the flowing waste of the metropolis. Every few months, an unusually dense pocket of methane gas would be ignited by one of their kerosene lamps and the hapless soul would be incinerated twenty feet below ground, in a river of raw sewage.

The scavengers, in other words, lived in a world of excrement and death. Dickens began his last great novel, Our Mutual Friend, with a father-daughter team of toshers stumbling across a corpse floating in the Thames, whose coins they solemnly pocket. “What world does a dead man belong to?” the father asks rhetorically, when chided by a fellow tosher for stealing from a corpse. “'Tother world. What world does money belong to? This world.” Dickens' unspoken point is that the two worlds, the dead and the living, have begun to coexist in these marginal spaces. The bustling commerce of the great city has conjured up its opposite, a ghost class that somehow mimics the status markers and value calculations of the material world. Consider the haunting precision of the bone-pickers' daily routine, as captured in Henry Mayhew's pioneering 1844 work, London Labour and the London Poor:

It usually takes the bone-picker from seven to nine hours to go over his rounds, during which time he travels from 20 to 30 miles with a quarter to a half hundredweight on his back. In the summer he usually reaches home about eleven of the day, and in the winter about one or two. On his return home he proceeds to sort the contents of his bag. He separates the rags from the bones, and these again from the old metal (if he be luckly enough to have found any). He divides the rags into various lots, according as they are white or coloured; and if he have picked up any pieces of canvas or sacking, he makes these also into a separate parcel. When he has finished the sorting he takes his several lots to the ragshop or the marine-store dealers, and realizes upon them whatever they may be worth. For the white rags he gets from 2d. to 3d. per pound, according as they are clean or soiled. The white rags are very difficult to be found; they are mostly very dirty, and are therefore sold with the coloured ones at the rate of about 5 lbs. for 2d.

The homeless continue to haunt today's postindustrial cities, but they rarely display the professional clarity of the bone-picker's impromptu trade, for two primary reasons. First, minimum wages and government assistance are now substantial enough that it no longer makes economic sense to eke out a living as a scavenger. (Where wages remain depressed, scavenging remains a vital occupation; witness the perpendadores of Mexico City). The bone collector's trade has also declined because most modern cities possess elaborate systems for managing the waste generated by their inhabitants. (In fact, the closest American equivalent to the Victorian scavengers – the aluminium-can collectors you sometimes see hovering outside supermarkets – rely on precisely those waste-management systems for their paycheck.) But London in 1854 was a Victorian metropolis trying to make do with an Elizabethan public infrastructure. The city was vast even by today's standards, with two and a half million people crammed inside a thirty-mile circumference. But most of the techniques for managing that kind of population density that we now take for granted – recycling centers, public-health departments, safe sewage removal – hadn't been invented yet.

And so the city itself improvised a response – an unplanned, organic response, to be sure, but at the same time a response that was precisely contoured to the community's waste-removal needs. As the garbage and excrement grew, an underground market for refuse developed, with hooks into established trades. Specialists emerged, each dutifully carting goods to the appropriate site in the official market: the bone collectors selling their goods to the bone-boilers, the pure-finders selling their dog shit to tanners, who used the “pure” to rid their leather goods of the lime they had soaked in for weeks to remove animal hair. (A process widely considered to be, as one tanner put it, “the most disagreeable in the whole range of manufacture.”)

We're naturally inclined to consider these scavengers tragic figures, and to fulminate against a system that allowed so many thousands to eke out a living by foraging through human waste. In many ways, this is the correct response. (It was, to be sure, the response of the great crusaders of the age, among them Dickens and Mayhew.) But such social outrage should be accompanied by a measure of wonder and respect: without any central planner coordinating their actions, without any education at all, this itinerant underclass managed to conjure up an entire system for processing and sorting the waste generated by two million people. The great contribution usually ascribed to Mayhew's London Labour is simply his willingness to see and record the details of these impoverished lives. But just as valuable was the insight that came out of that bookkeeping, once he had run the numbers: far from being unproductive vagabonds, Mayhew discovered, these people were actually performing an essential function for their community. “The removal of the refuse of a large town,” he wrote, “is, perhaps, one of the most important of social operations.” And the scavengers of Victorian London weren't just getting rid of that refuse – they were recycling it.

— The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic - and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World (Steven Johnson)

#book quotes#steven johnson#the ghost map#the ghost map: the story of london's most terrifying epidemic - and how it changed science cities and the modern world#history#sanitation#waste management#recycling#economics#poverty#employment#labour#sociology#homelessness#welfare#authors#britain#victorian britain#england#london#thames#mudlarks#toshers#tanners#charles dickens#henry mayhew

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

So celebrity gossip is not my normal schtick but I thought it was kinda amusing.

#dell curry#sonya curry#nikki smith#steven johnson#well damn#celebrity gossip#spouse swap#love is so messy sometimes#steph curry#seth curry#my ex is dating your ex so there

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

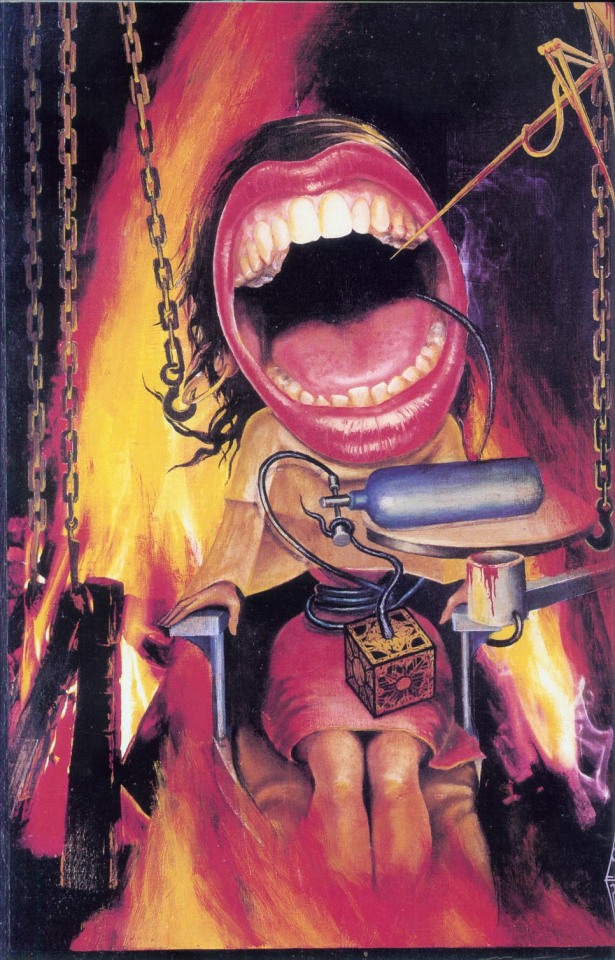

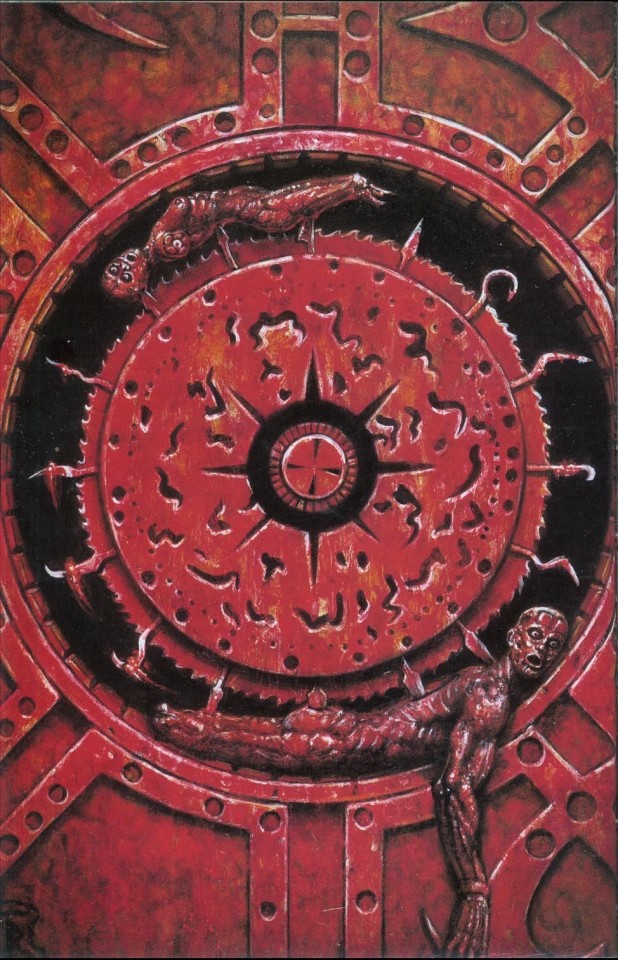

MARVEL BRANCHES OFF INTO CLIVE BARKER-STYLE HORROR IN THE EARLY '90s.

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on blood-soaked interior illustrations and/or horror pin-ups from "Clive Barker's Hellraiser" Vol. 1 #10. December, 1991. Epic Comics (a then Marvel Comics imprint).

Artwork by Mark Evans, Dominic Buggatto, Bo Hampton, & Steven Johnson.

Source: https://read-comic.com/clive-barker-s-hellraiser-issue-10.

#Hellraiser Vol. 1#Hellraiser Comics#Hellraiser#Hellraiser Epic Comics#Epic Comics#Clive Barker's Hellraiser#Clive Barker's Hellraiser 1991#1991#90s horror#Horror Comics#Horror#Horror Art#Clive Barker#Comics#Marvel#Epic Comics 1991#Illustration#Hardgore#Epic Comics Marvel Imprint#1990s#Clive Barker's Hellraiser Vol. 1#Steven Johnson#Dominic Buggatto#Mark Evans#Body horror#Epic#Bo Hampton#Marvel Imprint

0 notes

Text

#julie pinson#billie reed#rachel melvin#steven johnson#Stephen Nichols#soap opera#daytime tv#dool#daytime television#actress

0 notes

Photo

Invention of the Cal Trans Automatic

1 note

·

View note

Text

A paragraph I enjoyed quite a lot; Steven Johnson, author of 'The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic', on how he imagines John Snow's self-experiments revolving around anesthetic chloroform.

#john snow#steven johnson#book blog#books#book quotes#quotes#booklr#paragraph#books and reading#books and literature#books and libraries#the ghost map#literature#lit#nonfiction#epidemic#london#experimentation#anesthetic chloroform#chloroform#anesthetic#book photography#reading#read#snow#mine

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Play Made the Modern World (Book Extract)-by Steven Johnson

‘Roughly forty-three thousand years ago a young cave bear died in the rolling hills on the northwest border of modern-day Slovenia. A thousand miles away and a thousand years later, a mammoth died in the forests above the river Blau near the southern edge of modern-day Germany. Within a few years of the mammoth’s demise, a griffon vulture also perished in the same vicinity. Five thousand years…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

But the single most important factor driving London's waste-removal crisis was a matter of simple demography: the number of people generating waste had almost tripled in the space of fifty years. In the 1851 census, London had a population of 2.4 million people, making it the most populous city on the planet, up from around a million at the turn of the century. Even with a modern civic infrastructure, that kind of explosive growth is difficult to manage. But without infrastructure, two million people suddenly forced to share ninety square miles of space wasn't just a disaster waiting to happen – it was a kind of permanent, rolling disaster, a vast organism destroying itself by laying waste to its habitat. Five hundred years after the fact, London was slowly re-creating the horrific demise of Richard the Raker: it was drowning in its own filth.

— The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic - and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World (Steven Johnson)

#book quotes#steven johnson#the ghost map#the ghost map: the story of london's most terrifying epidemic - and how it changed science cities and the modern world#history#sanitation#waste management#medical history#sociology#victorian era#britain#victorian britain#england#london

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Justin Chatwin va avea o apariţie cameo în scurtmetrajul ‘Through the Corners’

Proiect nou la orizont ! Justin va avea un rol cameo în viitorul scurtmetraj indie Through the Corners. Todd Blubaugh (foto) deţine rolul principal, distribuția fiind completată de Shannon Mary Dixon și Ryan Mulkay.

Scott G Toepfer regizează după un scenariu propriu, Steven Johnson servind ca producător prin intermediul Factory Films.

Deși majoritatea informațiilor sunt ținute sub cheie momentan, se pare că intriga filmului se învârte în jurul protagonistului care vrea să își vindece rănile familiale cu ajutorul tradițiilor de la țară.

Nu au fost dezvăluite detalii despre rolul interpretat de Justin.

Filmările au demarat la sfârșitul lunii august, acestea continuând în toamna acestui an în mai multe locații din California. Sunt planificate filmări și în Kansas la final de noiembrie. Data de lansare a scurtmetrajului este preconizată pentru anul viitor.

Scriitor, fotograf, mare pasionat de motociclete și ocazional actor, Blubaugh a mai avut rolul principal în lungmetrajul independent Lotawana lansat anul acesta. În 2016 și-a lansat prima carte, Too Far Gone. Blubaugh are de asemenea propriul podcast, The Blue Todd Cast, Justin fiind invitat în una din edițiile de anul trecut.

După ce a renunțat la carieră în microbiologie în 2007, Toepfer s-a văzut lucrând full-time că fotograf pentru companii că Mercedes-Benz sau Harley-Davidson. Acest job de pe urmă l-a condus spre cinematografie, Toepfer ajungând să regizeze la scurt timp reclame, iar în 2011 documentarul It’s Better In the Wind.

#Proiect nou#Through the Corners#2023#Indie#Scurtmetraj#Ştire#Comunicat oficial#Todd Blubaugh#Shannon Mary Dixon#Ryan Mulkay#Scott G Toepfer#Steven Johnson

0 notes

Text

I cant help it I love men covered in blood

#hot characters#hot actors#cillian murphy#peaky blinders#scream#daredevil#matt murdock#steven yeun#patrick bateman#american psycho#hannibal#mads mikkelsen#kick ass#aaron taylor johnson

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

RAYMOND ABLACK as Brandon

Love in the Villa (2022) dir. Mark Steven Johnson

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

THE EXPANSE (2015-2022)

Exodus (5.01)

insp.

#😳#the expanse#theexpanseedit#fred johnson#jim holden#chrisjen avasarala#amos burton#beegifs#chad coleman#steven strait#shohreh aghdashloo#wes chatham

266 notes

·

View notes