#such a compelling question. we may never know (it is explicitely shown to us the fandom just collectively has the brain capacity of a 2 y/o

Text

LADY NAGANT!!!!!!

#SHES HEREEEEEEEEEEE#lady nagant fired for attempted unionisation she was ahead of her time fr </3#overhaul 😭 he's such a wet little mess of a man yeah no u just sit in the rain while she does all the work it's fine#ough her getting overhaul out of tartarus bc he couldn't do it himself. i fucking hate overhaul but#there's smthn about lady nagant still showing heroic tendencies even after all this time and everything that happened#like is she evil or did she just snap after years being forced to be a blind government dog for the Very Corrupt Hero Commission?#such a compelling question. we may never know (it is explicitely shown to us the fandom just collectively has the brain capacity of a 2 y/o#'you told the others to go wild so why am i the only one whose freedom comes at a price?' :(((( she's never been truly free :((#i think she deserves to go wild personally i think lady nagant should blow up the hpsc and all for one too actually#she's everything i want hawks to be like hawks u want ur lady nagant era sooooo badly pls pls pls arent u tired of being nice#mha#mha spoilers

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

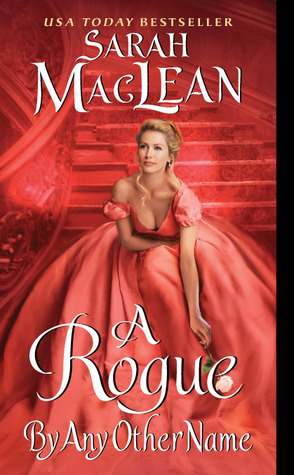

A Rogue By Any Other Name. By Sarah MacLean. New York: Avon, 2012.

Rating: 2/5 stars

Genre: historical romance

Part of a Series? Yes, The Rules of Scoundrels #1

Summary: A decade ago, the Marquess of Bourne was cast from society with nothing but his title. Now a partner in London’s most exclusive gaming hell, the cold, ruthless Bourne will do whatever it takes to regain his inheritance—including marrying perfect, proper Lady Penelope Marbury.

A broken engagement and years of disappointing courtships have left Penelope with little interest in a quiet, comfortable marriage, and a longing for something more. How lucky that her new husband has access to such unexplored pleasures.

Bourne may be a prince of London’s underworld, but he vows to keep Penelope untouched by its wickedness—a challenge indeed as the lady discovers her own desires, and her willingness to wager anything for them... even her heart.

***Full review under the cut.***

Content Warnings: explicit sexual content, gambling

Overview: I don’t know how to rate this book. On the one hand, MacLean has a knack for writing addictive romances, and I found the heroine to be fairly complex and the crux of the plot to be compelling; but on the other hand, there were a lot of tropes I personally do not care for in this book, so enjoying it fully was difficult. I ultimately settled on giving A Rogue by Any Other Name 2 stars because of my subjective experience, not necessarily because MacLean is bad at her craft.

Writing: I found MacLean’s prose to be fairly well-crafted; not only does it flow well, but it also balances showing and telling. Sentences and descriptions are lush and emotive when they need to be, and slow and sensual when appropriate. MacLean also paces her novel fairly well; on the whole, the story (and sentences) moves along at a quick pace that doesn’t feel rushed, and moments that were more emotionally weighty felt like they had room to breathe.

Perhaps the most interesting thing MacLean does with her book’s structure is insert small excerpts of letters in between scenes or between chapters. These letters are written primarily from the heroine’s point of view, showing her attempts to write to the hero from the time he goes away to Eton to almost the present day. In my opinion, these letters were a good way to show that the heroine had a long history of trying to reach the hero, and I think it worked better than MacLean simply telling the reader in some flashback or climatic scene.

Plot: The main plot of this book follows Michael (the Marquess of Bourne) as he seeks revenge on Viscount Langford, the man who took his entire inheritance in a game of cards. After nearly ten years, he finds that Langford has lost his lands to the Marquess of Needham and Dolby, who has added them to his eldest daughter’s dowry. Bourne thus traps the eldest daughter in a compromising situation which forces them to wed, and he must devise a way to get back at Langford while also dealing with the angst that his marriage stirs up. Not only is his wife, Penelope, one of his dearest childhood friends, but Langford’s son is the third part to their inseparable childhood trio. Bourne must thus figure out whether revenge or love for his childhood friends is more important.

On top of that, Bourne is notorious for not only losing his inheritance, but for building back his fortune by running one of London’s most dangerous gambling dens. His reputation, as well as the scandal should the circumstances of his marriage leak out, is sure to cause harm to Penelope’s family by making it impossible for her younger sisters to marry.

Honestly, I was pretty intrigued by this plot. The question of what matters more, revenge or love, was a really interesting promise with a lot of potential for angst and moral dilemma. I think in general, MacLean handled the plot well by making Penelope a formidable force and making the details of the drama feel real. The thing I really didn’t like, however, was how the initial “marriage trap” went down. Bourne puts Penelope in a compromising situation by having her spend the night alone with him. To her credit, she tries to escape, and Bourne was 100% a horrible person for making her stay with him. I honestly felt like that wasn’t the problem, since it created high stakes and a flaw that Bourne had to atone for. Where it went wrong for me was in Bourne’s character and his actions. I think if Bourne had just blocked the door and prevented Penelope from leaving their shared room, it would have been sufficiently bad, but Bourne also picks up Penelope and spanks her before ripping her dress so that even if she escapes, she’s well and truly ruined. To me, picking up a woman and spanking her feels infantilizing, and it’s a misogynistic flaw that I simply can’t get over. I also feel like ripping her dress and exposing her constitutes sexual assault, and I couldn’t get over that either.

Characters: Penelope, our heroine, is fairly likeable at the start. She’s the eldest in a line of daughters whose spinsterhood threatens to ruin her sisters’ chances at finding matches, and her dilemma between doing right by her family and doing something for her own happiness was a compelling one. I liked that she was sharp-tongued to the point where she would say or withhold things from Bourne to hurt him; it made her seem flawed without being overly petty, mainly because most of the things that hurt him were borne out of her frustration over her situation. The main thing I didn’t like about her was that she didn’t seem to have any female friends, and when she met another woman who was beautiful or who may have shown interest in Bourne, she got absurdly jealous. To MacLean’s credit, Penelope never acts in hostility towards other women and eventually develops a kind of friendship with Bourne’s gorgeous housekeeper, but I found this jealousy over a man who does nothing but hurt her disappointing.

Bourne, our hero, is an archetype that I really don’t like: self-hating, brooding, controlling, and violent. While I liked his revenge vs love dilemma, I hated that he was self-loathing to the point of destroying everything around him (when he could have easily just... not). I think more could have been done to make him a selfish, obsessive, manipulating character without making him so controlling of Penelope. His actions regarding their marriage are bad enough; I really didn’t need him to try to control Penelope’s life by giving her no control over the household, over where she goes, etc. and I really didn’t need him to be so violent and jealous that he thought about murdering anyone who so much looked at Penelope.

To be honest, I was hoping Penelope would run away from Bourne and end up with Tommy, a childhood friend who seems to treat her with genuine kindness and worries about her happiness. Tommy was interesting in that he loves Penelope as a brother would, not as a suitor, and respects her decisions even if they are obviously toxic or self-destructive.

Other characters were interesting for their potential to offer commentary. I liked Penelope’s sisters, who embody different personality types and have different views on marriage and scandal. Watching Penelope worry for them was honestly touching, and provided unique opportunities for reflecting on romantic expectations versus realities. Bourne’s colleagues at the gambling den were also pretty great in that they seemed to be more respectful of Penelope than Bourne was. I liked that they called Bourne out for his behavior and didn’t try to control Penelope on his behalf.

Langford, our primary antagonist, wasn’t present enough for me to have an opinion one way or the other. Honestly, I didn’t feel that much animosity towards him - he was an ass for taking the entire inheritance from a 21 year old, but I felt like the blame was more on Bourne. I only reveled in his eventual demise because he got pretty sexist in the final showdown.

Romance: I’m going to just say it: I wasn’t rooting for Penelope and Bourne to be together. Most of their “love story” involved a lot of manipulative, controlling behavior on Bourne’s part, which would have been something to atone for and could have been a good story had Penelope not forgotten about it the instant Bourne showed some basic human decency. A lot of their fights consisted of Bourne being manipulative, Penelope realizing that everything he does is for selfish reasons, then forgetting it because she finds him attractive or because he does something nice. There was no acknowledgment or atonement for him hurting her or using her, and Penelope decides she loves Bourne because he raised himself above his scandal by building back his fortune. For some reason, she finds that admirable, but because we see Bourne ruining people in the same way he was ruined at the beginning of the book, I couldn’t see him in the way Penelope did.

Bourne’s redemption also felt pretty empty. Throughout the whole book, there’s this constant lamentation that he’s not good enough for Penelope, that he will only cause her ruin, but he wants her anyway. He’s also so obsessed with revenge that everything he does hurts Penelope, whether it be ignoring her happiness or going after Langford by way of Tommy. Instead of a slow, steady process where he comes to value love over revenge and where he makes up for all the hurt he caused her, he seems to turn on a dime with maybe 25% left of the book. Honestly, I found their whole romance exhausting after the first hundred pages, and I wished there was more of a gradual ennobling of Bourne’s character, rather than the self-indulgent pity party he seems to exhibit.

TL;DR: Even though A Rogue By Any Other Name has quick, witty prose and an interesting crux at the heart of the plot, the self-loathing, controlling hero and exhausting romance ultimately prevented me from enjoying this book.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submission: How do you think r+l=j will be handled in the books?

Hi, him-e! I appreciate the fact that you make an effort to parse through what the show’s given us in order to make more calculated predictions about what’s coming in the books. I’d like to ask, then—because I don’t recall you ever talking about it—how will r+l=j be handled in the books.

It’s a fairly accepted possibility in fandom that finding out about it will wreck Jon. And fair enough, it probably will, considering how much pride he takes from being Ned’s son. But then there’s the rub for me—a lot of people also expect Jon to be angry at Rhaegar and to revolt against his biological father by abandoning the role he was supposed to have in the WftD. That makes sense, it can be existentially terrifying to think that your actions are all a product of a prophecy and that you have no control over them. It’d also fit with the other five main characters, who will likely all be going through their own dark phases.

Here’s the part where I think we should take the show into consideration. What effect did r+l=j have on Jon, exactly? Mostly, none—I’d say it served as a catalyst for Dany’s downfall. Nothing was made to challenge Rhaegar’s character or actions, and the last season was the perfect place to do so, considering he’s Dany’s brother and almost every single aspect of Dany started being portrayed negatively. But sure, one could argue that the show isn’t good at handling psychological turmoil and that he’s Jon’s father too, and Jon must remain morally pure.

Still, I then think about the books. If GRRM intends to make Jon rebel against Rhaegar and what he stood for as part of the fandom believes, why didn’t he seed anything related to that yet? Anything that makes Rhaegar more challenging and least susceptible to idolization? Some examples of how he could’ve done this:

* GRRM could’ve shown Doran or Oberyn still angry at Rhaegar for leaving Elia behind. Instead, they both want to side with Viserys and later Daenerys without any (mentioned) reservations.

* GRRM could’ve had Ned thinking about the fucked up power dynamic between Rhaegar and Lyanna (less harshly than Robert, but still negatively), but instead Ned only thinks about how Rhaegar didn’t frequent brothels.

* GRRM could’ve had Dany have her view of Rhaegar be challenged the way her view of Aerys is being (slowly) challenged, instead she still thinks of him the same by the end of the fifth book.

* GRRM could’ve added a POV who is critical of Rhaegar’s actions, yet he added three in FeastDance who idolize him (JonCon, Cersei, Barristan).

And that’s not even mentioning how R/L was painted as straightforwardly romantic in the S7 finale, which may well be what GRRM does—if he doesn’t think Dany was raped by Drogo in the books, maybe he thinks R/L is an unproblematic love story, even if many have pointed out the consent issues. Finally, I don’t see his friend Arthur Dayne having his reputation challenged in any way in-universe for remaining with Rhaegar despite the fact that there is reasonable criticism to hold against him.

My question, then, is: isn’t it more likely that Jon’s problem with r+l=j lies with his relationships with Ned and Dany and not with Rhaegar?

Hi, thanks for your submission, and sorry it took me a while to answer! ;))

Using the show as an indicator for how the books will deal with things like this is very tricky—because, as you said, the show sucks at psychological insight, and character motivations are usually either grossly simplified or not taken into consideration at all (which, ironically, makes them seem even more obscure and complicated if you’re trying to analyze them. See: the entire debate on why Sansa didn’t tell Jon about the knights of the Vale back in season 6. The show simply didn’t address the reason why she didn’t tell Jon, because it wasn’t important to the plot, but the fandom—me included—tried to make sense of it nonetheless, with increasingly convoluted explanations. Was Sansa trying to throw Jon under the bus, and let him perish in the battle so she could be lady of Winterfell? But that clashes with her desperate attempts to convince Jon to delay the battle. Did she hope they could do without Littlefinger’s help until last minute? Was she afraid that Jon would’ve had the final say on how to use the Knights, had he known? Was she trying to prevent him from taking credit for the victory? And so on).

There’s also the fact that the show dealt very quickly and superficially with the Prince that was Promised and Azor Ahai prophecies, mostly via Melisandre’s cryptic catchphrases and more as an afterthought or book nod than as an organic part of the narrative. The prophecy was just not conveyed well in the show. We’ve hardly ever seen other characters grapple with its meaning, or experienced its importance in the context of Westeros’ slowly waking up to the threat of the White Walkers. So, if the bulk of book!Jon’s reaction to r+l=j is temporarily rejecting his supposed role in the PtwP prophecy, it makes sense that the show completely skipped it, just as it makes sense that it skipped the valonqar part in Cersei’s prophecy: it simply has no place in the show’s narrative as they devised it. There would be no point in having a major character angst about his role in a prophecy, if said prophecy is all but a namedrop whose significance remains largely unknown to the average viewer who hasn’t read the book.

So… is it possible that in the books resurrected!Jon will go through a phase of complete rejection and denial of his heroic destiny, that will climax with the reveal of his parentage and a major identity crisis? Yes, totally. It’s exactly the mix of complex character study + mystical/magical stuff that I can see d&d scrapping in favor of a more materialistic, down to earth “game-of-thrones” narrative (the whole bend-the-knee pseudopolitical drama with Dany, for example).

But what will he reject, what will he deny? Which identity will challenged?

His destiny as a prophesied hero, fulfilling which has never been an (explicit) driving force for him? (we know everything Jon’s done in the Night’s Watch was building up towards his becoming the champion of humanity against darkness, the “third head of the dragon”, the “prince that was promised”, but it was Ned’s teachings and Ned’s moral lessons that inspired his choices and actions, not Rhaegar’s prophecy) His (non-existent) relationship with a biological father that never mattered to him?

Or…

isn’t it more likely that Jon’s problem with r+l=j lies with his relationships with Ned and Dany and not with Rhaegar?

^ Nailed it.

I think Jon’s psychological conflict about his parentage will be more about Ned/his Stark identity (and Dany) than about Rhaegar. For one thing, Rhaegar—regardless what light the overall story presents him in—isn’t really present in Jon’s narrative; Jon has virtually no opinion of him, and Rhaegar’s name rarely shows up in his chapters. Sure, when the PtwP prophecy finally erupts in Jon’s narrative and he realizes what Rhaegar was trying to accomplish, he’ll necessarily develop more complex feelings for him. But as of now, Rhaegar Targaryen is simply someone from the past that Jon isn’t really preoccupied with. Secondly, and more importantly, Rhaegar is a dead character, who has always been dead since the beginning of the story. I truly doubt he is going to have more of an impact on Jon’s character evolution than Ned (the father that raised him, the only father he’s known, and the faux-protagonist of book one) or Dany (the living and breathing major character Jon will plausibly have a romantic dynamic with, that with no doubt will be drastically affected by the parentage reveal).

I actually think it’s more likely and more narratively compelling that, rather than rebelling against Rhaegar, r+l=j makes Jon rebel against Ned, and everything he represents. Make him temporarily reject his Stark identity (out of fiery anger re: being lied to by Ned, and forced to a life of bastardy and anonymity, the reasons behind which resurrected!Jon, more wolf than he’s ever been, might not immediately understand, or care to understand) and embrace his Targaryen ancestry instead, with the whole fire&blood shebang. That is… until he’s made whole again by the love he has for his siblings, and the need to protect them. I think Jon’s love for his family—the family he grew up in—will be what eventually leads him *back home*, back to his Stark roots, back to Ned’s teachings.

#submission#got**#jon**#stark meta#got asks#show vs books#got meta#jon meta#r plus l equals j#asoiaf spec#rhaegar targaryen#ned stark#asoiaf meta

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Facebook Edgerank decides which stories appear in users news feed?

New Post has been published on https://martechguide.com/facebook-edgerank-decides-which-stories-appear-in-users-news-feed/

Facebook Edgerank decides which stories appear in users news feed?

Facebook Edgerank decides which stories appear in users news feed?

Facebook Edgerank algorithm hides the boring stories, so if the story doesn’t score good, no one will be seeing it.

When people login facebook what they see the first is the “newsfeed”. This is what is shared among their friends on facebook platform.

Every action their friends take is a potential newsfeed story. Facebook calls these actions “Edges.” That means whenever a friend posts a status update, comments on another status update, tags a photo, joins a fan page, or RSVP’s to an event it generates an “Edge,” and a story about that Edge might show up in the user’s personal newsfeed. Facebook Edgerank decides which stories appear in users news feed?

Facebook created an algorithm to predict how interesting each story will be to each user. And Facebook calls this algorithm “EdgeRank” because it ranks the edges. Then they filter each user’s newsfeed to only show the top-ranked stories for that particular user.

Why Should I worry?

Because most of your Facebook fans never see your status updates.

Facebook looks at all possible stories and says “Which story has the highest EdgeRank score? Let’s show it at the top of the user’s newsfeed. Which one has the next highest score? Let’s show it next.” If EdgeRank predicts a particular user will find your status update boring, then your status update will never even be shown to that particular user.

How does EdgeRank work?

EdgeRank is like a credit rating.it’s invisible, it’s important, it’s unique to each user, and no one other than Facebook knows knows exactly how it works.

At Facebook’s 2010 F8 conference, they revealed the three ingredients of the algorithm:

Affinity Score

Edge Weight

Time Decay

Affinity Score

Affinity Score means how “connected” a particular user is to the Edge. For example, I’m friends with my brother on Facebook. In addition, I write frequently on his wall, and we have fifty mutual friends. I have a very high affinity score with my brother, so Facebook knows I’ll probably want to see his status updates.

Facebook calculates affinity score by looking at explicit actions that users take, and factoring in

the strength of the action,

how close the person who took the action was to you, and

how long ago they took the action.

Explicit actions:

Include clicking, liking, commenting, tagging, sharing, and friending. Each of these interactions has a different weight that reflects the effort required for the action–more effort from the user demonstrates more interest in the content. Commenting on something is worth more than merely liking it, which is worth more than merely clicking on it. Passively viewing a status update in your newsfeed does not count toward affinity score unless you interact with it.

Affinity score measures not only my actions, but also my friends’ actions, and their friends’ actions. For example, if I commented on a fan page, it’s worth more than if my friend commented, which is worth more than if a friend of a friend commented. Not all friends’ actions are treated equally. If I click on someone’s status updates and write on their wall regularly, that person’s actions influence my affinity score significantly more than another friend who I tend to ignore.

Lastly, if I used to interact with someone a lot, but less so now, then their influence will start to wane. Technically, Facebook is just multiplying each action by 1/x, where x is the time since the action happened.

Affinity score is one-way. My brother has a different affinity score to me than I have to him. If I write on my brother’s wall, Facebook knows I care about my brother, but doesn’t know if my brother cares about me.

This may sound confusing, but it’s mostly common sense.

Edge Weight

Each category of edges has a different default weight. In plain English, this means that comments are worth more than likes.

Every action that a user takes creates an edge, and each of those edges, except for clicks, creates a potential story. By default, you are more likely to see a story in your newsfeed about me commenting on a fan page than a story about me liking a fan page.

Facebook changes the edge weights to reflect which type of stories they think user will find most engaging. For example, photos and videos have a higher weight than links. Conceivably, this could be adjusted on a per-user level–if Sam tends to comment on photos, and Michelle comments on links, then Sam will have a higher Edge weight for photos and Michelle will have a higher Edge weight for links. It’s not clear if Facebook does this or not.

New Facebook features generally have a high Edge weight in order to promote the feature to users. For example, when Facebook Places rolled out, check-ins had a very high default weight for a few months and your newsfeed was probably inundated with stories like “John checked into Old Navy.” Generally, after a few weeks or months Facebook dials the new feature back to a more reasonable weight.

Time Decay

As a story gets older, it loses points because it’s “old news.”

EdgeRank is a running score–not a one-time score. When a user logs into Facebook, their newsfeed is populated with edges that have the highest score at that very moment in time. Your status update will only hit the newsfeed if it has a higher score–at that moment in time–than the other possible newsfeed stories.

Facebook is just multiplying the story by 1/x, where x is the time since the action happened. This may be a linear decay function, or it may be exponential–it’s not clear.

Additionally, Facebook seems to be adjusting this time-decay factor based on

how long since the user last logged into Facebook, and

how frequently the user logs into Facebook.

It’s not clear how exactly this works, but my experiments have shown time-decay changes if I log into Facebook more.

How do I check my EdgeRank Score?

Anyone who claims to check your EdgeRank is lying to you. It is completely impossible.

You can measure the effects of EdgeRank by seeing how many people you reached. You can also measure how much engagement you got (which impacts EdgeRank) using a Facebook analytics tool.

But there is no “general EdgeRank score” because each fan has a different affinity score with the page.

Furthermore, Facebook keeps the algorithm a secret, and they’re constantly tweaking it. So the value of comments compared to likes is constantly changing.

How can I optimize my fan page for EdgeRank?

It’s hard to trick an algorithm into thinking that your content is interesting. It’s much easier to rewrite your content so your fans leave more likes and comments.

Take your dull press releases, and turn them into questions that compel your fans to engage.

Here’s some examples:

“Click ‘like’ if you’re excited that we just released our new line of Gift products at Picworks.”

“Fill-in-the-blank: All I want for Gifting is ___. Our latest Diwali special discount is Rs 800/- Off.”

“On a scale of 1-5, I think Modi is a great marketer. Read his case study on General Elections this year.”

All those likes and comments will increase the Affinity Score between each fan and your page, boosting how many fans see your status updates in their newsfeed.

When people login facebook what they see the first is the “newsfeed”

This is taken from www.edgerank.net

0 notes

Text

One Way or Any Way? – Part 2

By Greg Koukl

I do not consider myself a particularly brave person, and I think it especially foolish, on the main, to make a frontal assault on a clearly superior force. Further, it is always dangerous to cross theological swords with C.S. Lewis. He was, arguably, the most compelling voice for Christianity in the 20thcentury, and his impact continues unabated into the 21st.

Even so, as a young Christian I read something Lewis wrote that gave me pause the first time I saw it. Now, decades later, it troubles me more than ever. The problematic piece appears towards the end of The Last Battle, the final installment of Lewis’s wonderful and theologically rich children’s fantasy, The Chronicles of Narnia.

Emeth, a noble young Calormene soldier who all his life had innocently served Tash, the false god of his people, encounters Aslan face to face for the first time.

“Lord, I am no son of thine but the servant of Tash,” he admits to the great lion.

“Child,” Aslan answers, “all the service thou hast done to Tash, I account as service done to me…. If any man swear by Tash and keep his oath for the oath’s sake, it is by me that he has truly sworn, though he know it not, and it is I who reward him.”[i]

In narrative form, Lewis seems to be suggesting that those who sincerely pursue God the best way they know how, regardless of the particulars of their own religion, are accepted by Him. Could he be right?

Anonymous Christians?

I don’t for a moment think Lewis was a pluralist. In fact, when Emeth asks Aslan if he and Tash are one (“Tashlan,” as some had put it), he “growled so that the earth shook.” This was error; Tash and Aslan were opposites. Clearly, though, the religious sincerity and the noble life of this young Calormene were taken by Aslan as implicit loyalty to the lion himself.

Lewis intimates that, though all religions are not true in themselves (pluralism), there still exist people of other faiths who are what Catholic theologian Karl Rahner called “anonymous Christians”—those enjoying the grace that comes through Jesus alone, even though they never explicitly put their faith in Him.

Was Lewis right? Many Evangelicals in this country seem to think he was, giving rise to a trend I have called the “confused confession.” It’s a term I introduced in the last issue of Solid Ground (January 2019) to describe the following claim: “Jesus is my savior. He is the only way for me. But I can’t say He is the way for others.”

As I argued earlier, this could mean a number of different things.[ii] Some, for example, may be uncertain about the fate of those who never heard about Jesus. This, I think, is Lewis’s concern. Perhaps God will judge them by the limited light they’ve been shown. Others, though, seem to take it quite a bit further.

Dinesh D’Souza, author of the vigorous defense of Christianity titled What’s So Great about Christianity, faltered in a debate with atheist Christopher Hitchens and Jewish thinker Dennis Prager. When asked by Prager if Jews who do not accept Jesus as savior can still be saved, he said, “I believe the answer to that is yes.” Clearly, Abraham made it to Heaven without believing in Jesus, D’Souza pointed out. There must be, then, another “mode of salvation…that doesn’t include Jesus.”[iii]

In her book A Simple Path, Mother Teresa explained why she did not “preach religion” to those in her care. In a section titled “Equal Before God” she writes:

There is only one God and He is God to all; therefore it is important that everyone is seen as equal before God. I’ve always said we should help a Hindu become a better Hindu, a Muslim become a better Muslim, a Catholic become a better Catholic.[iv]

Consequently, Mother Teresa never considered it a problem when people of different religions joined together in prayer at her center and read from their own scriptures, since her focus was to encourage them in their “relationship with God, however that may be.”

Roman Catholic thinker Avery Cardinal Dulles makes this stunning claim in his essay “Who Can Be Saved?”:

Jews can be saved if they look forward in hope to the Messiah and try to ascertain whether God’s promise has been fulfilled. Adherents of other religions can be saved if, with the help of grace, they sincerely seek God and strive to do his will. Even atheists can be saved if they worship God under some other name and place their lives at the service of truth and justice.[v]

Remarks like these raise a host of questions. If Jews today don’t need to believe in Jesus, but can be saved as Abraham was, why did both Jesus and Paul say the gospel should go to the Jews first, before it went to the Gentiles (Matt. 10:5–6, Acts 1:8, Rom. 1:16)? Given that Hindus worship idols, wouldn’t helping them be “better” Hindus make them better at breaking God’s first commandments (Ex. 20:3–5)? If atheists are seeking truth, why does Paul say they are suppressing the truth (Rom. 1:18)? If people following false religions are recipients of God’s grace, why does Scripture say they have exchanged the truth of God for a lie (Rom. 1:25) and are therefore without excuse (1:20)? Worse, what implications do such sentiments have for the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18–20)?

This is why I call such a confession “confused.” It may sound plausible at first, but it is hard to make sense of it in light of either Old or New Testament teaching.

Let me tell you one of the reasons this confusion gets a foothold. People draw the wrong conclusions from an obvious scriptural fact: Not everyone in history needed to believe in Jesus to be restored to relationship with God. Though it may be that Abraham understood something about Jesus (John 8:56), that cannot be said of every patriarch, prophet, or Old Testament faithful. Despite their own sins, they still found favor with God apart from explicit faith in Christ. This is Lewis’s point.

Couldn’t the same be true today, some ask, not only of those who have never heard, but also for those who reject the message of Christ through no apparent fault of their own? How can we say what’s in a person’s heart? Who are we to judge?

This, I think, is D’Souza’s, Teresa’s, and Dulles’s point. Though Jesus’ death on the cross is the only provision for forgiveness, belief in Jesus is not the only way to receive the grace He alone provides. This view is called “inclusivism,” since even those who do not believe in Christ can, in certain circumstances, be “included” in the grace that He alone secures.

It is true; you and I are in a poor position to judge the hearts of others. But God is not. Though our judgments may falter, His are true. Has He said anything to shed light on this question? He has. Lots.

A “Jealous” God

First, it might be helpful to remember that from the very beginning, the God of the Bible has been narrow in His demands.

Adam and Eve’s violation of God’s singular restriction in the garden brought swift justice. The serpent’s suggestion of an alternate route to wisdom, knowledge, and fulfillment resulted in death, not the promised enlightenment.

God’s very first commandment to His fledgling people explicitly condemned all other “roads to Rome.” In Exodus 20:2–5, He said, “I am the Lord your God.... You shall have no other gods before Me.... You shall not worship them or serve them; for I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God.” Transgressors of this command were executed, some destroyed directly by God Himself.

God showed His utter contempt for other religions by pummeling Egypt with plagues, each one directed at a different Egyptian deity (Exodus 12:12b: “...and against all the gods of Egypt I will execute judgments—I am the Lord”). The capstone plague ended the life of every firstborn whose doorway lacked the blood covering that was to be applied according to God’s very precise and particular conditions.

During their wanderings in the desert, the Jews were offered only one antidote to the poison of the serpents God had unleashed in judgment upon them. Only those who gazed upon a bronze snake lifted up on a pole were spared (Num. 21:9). Jesus Himself cites this event as a type—a foreshadowing—of His crucifixion, which alone purchases eternal life (John 3:14–15).

In Acts, we learn that “Christian” was not the first name given to the followers of Jesus. Instead, the name they used for themselves embodied the heart of their message about the Savior. They were simply called “The Way”—not “a way,” or “one of the ways,” or “our way,” but The Way (Acts 9:2; 19:9, 23).

This pervasive theme of exclusivity was captured with crystal clarity in Jesus’ words, “Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the way is broad that leads to destruction, and there are many who enter through it. For the gate is small and the way is narrow that leads to life, and there are few who find it” (Matt. 7:13–14). Jesus’ very next words warned of false prophets who would appear as sheep yet would ravage the flock like wild wolves.

From Wide to Narrow?

Even so, it does seem that New Testament standards are more “narrow” than Old Testament ones. Why is that? Here, some distinctions may be helpful.

First, throughout the biblical revelation, the source of salvation has always been the unmerited mercy of God. Our Sovereign owes no rebel a pardon. That He extends clemency to any is a pure gift of grace (Eph. 2:8, Titus 3:4–7).

Second, the ground of salvation has always been the redemption secured by Christ on the cross. Old Testament saints who, because of progressive revelation, had not yet learned about Jesus were still saved because of Him. God “passed over the sins previously committed” (Rom. 3:25), knowing the full, complete, and final payment would be made at the cross (Heb. 9:15, 10:10–18).

Third, the means of salvation has also been constant. Every sinner ever justified gained access to God’s mercy by faith. Whether in Old Testament or New, active trust in God’s grace appropriated His mercy. In every age, the just have lived by faith (Gen. 15:6, Hab. 2:4, Rom. 4:5, 5:1).

Each of those has been constant. Only one thing changed as God progressively revealed His plan. The way one expressed their faith in God (the means), that appropriated the work of Christ (the ground), based on the grace of God (the source), has been different at different times.

Adam received the covering God provided for his nakedness and trusted God’s promise that a seed of woman would crush the serpent (Gen. 3:15, 21). Abraham simply believed God’s promise of descendants who would bring blessing to the nations of the earth (Gen. 12:3, 15:6). Jewish slaves in Egypt trusted God by believing the blood covering would protect them from the plague of death at the Passover (Ex. 12:13, 23). Old Testament saints trusted God through the atoning sacrifices He required to cover their sins (Leviticus).

There is only one question we need to answer at this point: What is the appropriate way of expressing faith now, in the New Covenant period, since the public appearance and proclamation of the world’s singular Messiah?

The answer from every New Testament writer is the same. Since Pentecost, the focus of faith and the ground of salvation are one and the same: Jesus. There is no other name that can save, and there is no other “name” we may put our trust in. Not the Levitical sacrifices or Passover blood (Heb. 10:8–10). Not zeal or sincerity (Rom. 10:1–2). Certainly not pagan gods, false prophets, or counterfeit religions (Matt. 24:23–25, Gal. 1:8–9, Jude 4).

That’s why Jesus said that our response to Him would be the acid test of our true loyalty to the Father. Anyone who loves God will honor the One sent by God. Conversely, those who reject Him, reject the Father also. This one point is so critical, it is repeated in various ways no less than 16 times in the New Testament (John 5:23b, 5:37–38, 8:19, 8:42a, 12:48–50, 14:7, 15:20b–21, 15:23, 16:2–3; 1 John 2:22, 2:23, 4:2–3, 4:15, 5:1, 5:9–12; 2 John 1:7–9a).

These verses reveal something crystal clear to me. Had any Old Testament saints lived during the time of Jesus or after, their love for the Father demonstrated by their earlier expression of faith would have driven them to embrace His Son, Jesus. Each one of those accepted by the Father under the Old Covenant would have loved the Son of the New (“Your father Abraham rejoiced to see My day, and he saw it and was glad,” John 8:56).

In a sense, then, nothing has changed from Genesis to Revelation. God’s way has always been specific, limited, and precise. A narrow gate leads to life. A broad way leads to destruction (Matt. 7:13–14).

And there are many more verses that make this clear. For example:

“He who believes in the Son has eternal life; but he who does not obey the Son will not see life, but the wrath of God abides on him.” (John 3:36)

“Therefore I said to you that you will die in your sins; for unless you believe that I am He, you will die in your sins.” (John 8:24)

“And I say to you, everyone who confesses Me before men, the Son of Man will confess him also before the angels of God; but he who denies Me before men will be denied before the angels of God.” (Luke 12:8–9)

And after he brought them out, he said, “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” They said, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved.” (Acts 16:30–31)

I testify about [the Jews] that they have a zeal for God, but not in accordance with knowledge. For not knowing about God’s righteousness and seeking to establish their own, they did not subject themselves to the righteousness of God. For Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to everyone who believes. (Rom. 10:2–4)

And the testimony is this, that God has given us eternal life, and this life is in His Son. He who has the Son has the life; he who does not have the Son of God does not have the life. (1 John 5:11–12)

The God-Fearing Gentile

The most compelling single passage against inclusivism comes from the book of Acts and the conversion of a Gentile named Cornelius. Scripture says Cornelius was “a devout man…who feared God with all his household, and gave many alms to the Jewish people and prayed to God continually” (10:2). Indeed, his “prayers and alms [had] ascended as a memorial before God” (10:4). As “a righteous and God-fearing man,” he was “divinely directed by a holy angel” to send for Peter to come to his house and hear a message from him (10:22).

This is quite a spiritual pedigree, all without the gospel of Christ. In fact, Peter was so impressed at the clear working of God in Cornelius’ life, he said, “I most certainly understand now that God is not one to show partiality, but in every nation the man who fears Him and does what is right is welcome to Him” (10:34–35). This is the whole of inclusivist theology in a single sentence. Everything stated about Cornelius fulfills the inclusivists’ demand.

What does Peter do next? He does not assure this “anonymous Christian” that all is well and turn on his heel to leave. Instead, he preaches the life, death, and resurrection of Christ (10:36–41), then warns of final judgment by Jesus for all except those who believe in Him for the forgiveness of their sins(10:42–43).

Why go through all this trouble and labor over theological details about Jesus? Here’s why. For all his spiritual nobility, Cornelius is still lost. If the inclusivist gospel were true, Cornelius would not have needed a special visit from Peter. Yes, Cornelius had responded faithfully to all the revelation given to him up to that point. But it was not enough. It was just the first step. Even God-fearing Cornelius needed the rest of the story, the specifics about Christ and the cross, without which he could not be saved.

The teachings of Christ and also the writings of those disciples Jesus personally trained to proclaim His message after Him give little comfort to inclusivists. Remarkably, Dulles admits as much: “The New Testament and the theology of the first millennium give little hope for the salvation of those who, since the time of Christ, have had no chance of hearing the gospel.”[vi]If this is the clear testimony of the ancients, what good reason do we have to abandon that message in the modern era? I don’t see any.

And I will give you one final reason to be faithful to that message.

Pascal Redux

I have a last thought for any who may still be tempted to sit on the fence on this issue. Blaise Pascal, the 17th century French scientist and Christian sage, once offered a famous wager to his detractors. Based merely on a kind of cost/benefit risk assessment, Pascal argued it is smart to “bet” on God. If the Christian is right, he gains eternal life. If wrong, he passes into non-existence, nothing lost. The atheist, on the other hand, gains nothing substantial if correct, and if incorrect suffers eternally for his error.

I think the wisdom of Pascal’s wager applies to inclusivism. If we preach the message of Jesus, the apostles, and the early church—that faith in Christ is necessary for salvation—and we are wrong, what is the downside? If we proclaim that those separated from the gospel are also separated from Christ and have no hope and are without God in the world (Eph. 2:12), yet we are mistaken, Heaven will be more crowded than we thought. If we erroneously preach exclusivism, the upshot is good news, not bad.

However, what if we take the side of inclusivism and err? What if we are wrong when we teach that the person who has heard the gospel of Christ does not have to answer its challenge by humbling himself before the cross? What if we say that sincere people will be accepted by God in the pursuit of their own religious convictions? What if we discourage other Christians from “forcing” their views on “good” Jews, Muslims, Hindus, etc.? What if we do any of these things and it turns out their rejection of Christ—either active or passive—seals their fate: judgment and an eternity of suffering for their crimes against God? What is the downside then? Only that we have given false hope to the lost and have prevented them from seriously considering the only salvation available to them. If you are an inclusivist and you are wrong, that is very bad news.

It seems we have a simple choice. We can be broad-minded and advance the broad way, a path Jesus said leads to destruction. Or we can endure being called “narrow-minded” and preach the narrow way, the only path that Jesus said leads to life. I, for one, would not want to be on the inclusivist’s side of this issue.

_____________________

[i] C.S. Lewis, The Last Battle (New York: Collier, 1956), 164–5.

[ii] For details, refer to “One Way or Any Way?—Part 1,” Solid Ground, January 2019, at str.org.

[iii] Dinesh D’Souza, “The Christian God, the Jewish God, or No God: A Meaningful Dialogue,” May 8, 2008. Find a video clip of this portion of the debate at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VoonNPAs1Zc.

[iv] Mother Teresa, A Simple Path (New York: Ballantine Books, 1995), 31.

[v] Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J., “Who Can Be Saved?,” First Things, February 2008.

[vi] Ibid.

0 notes

Note

1) Sorry if I came off as rude or attacking you, that wasn't my intention, but I just think that calling shinoyama 'queerbating' is simply not correct. Yamagi's feelings for Shino were hinted at as soon as in ep 4 of s1, when he outright asked if Shino liked girls - girls specifically (why would he be interested in Shino's orientation if he wasn't intersted in him personally in the romantic sense?), then were made clear in ep. 7 with the heart grab scene and then further reinforced later on, by

2) showing Yamagi's evident disdain/jealousy every time Shino mentions girls etc. It was very obvious from the beginning that Yamagi is gay for Shino, so the only question left was whether Shino would ever find about Yamagi's feelings and reciprocate, to which episodes 45/46 gave us an answer. The 'let's drink till morning, the two of us' WAS, in fact, Shino's explicitly asking Yamagi out romantically. It just couldn't have been anything else in that context, when we know for a fact that Shino

3) does consider going out for drinks, two people only, as romantic (again, the AkiLafter scene in ep. 41, and Shino's 'don't you know what that is? go with her alone'). And then there's Yamagi's reaction - the wide eyes and the 'quit joking around, you don't even know how I feel' (plus his confusion about 'how Shino felt' later on when he talks to Eugene) which made it clear that's exactly the way it felt to Yamagi as well - as a date invitation, except he couldn't know back then that Shino was

4) serious. But Shino WAS serious - the fact that he grabbed Yamagi's hair out of his face to look him straight in the eyes before asking him out was a clear indicator of how serious he was. He wouldn't have given Yamagi false hopes otherwise, while being perfectly aware of Yamagi's feelings for him. And it's not only that, the entirety of Shino's body language towards Yamagi in all their scenes together in ep 45, his fond expressions, the looks and the smiles that we'd never seen on him

5) before that, the gentle tone of his voice, him calling Yamagi scary with evident fondness (it's actually a common motive in anime, to reveal that a manly man may not be afraid of enemies, war etc. but he's always afraid of his spouse), everything about those scenes screamed that Shino knew about Yamagi's feelings even before the big reveal and was totally on board with them. Ep 46 basically confirmed what was already obvious, that in the end, they both had romantic feelings for each other

6) and had Shino not died, they'd have ended up together eventually. They're basically as canon as an IBO couple can get and their not getting a happy ending doesn't make them any less canon (technically there's still a chance Shino could turn out to be alive, as they literally went out of their way to not show us his body). As for the other potentially queerbaiting couples, I don't think that orumika, gaeein or makugae are meant to be interpreted as romantic (even though I ship all three).

7) As for Aston/Takaki, in their case I do interpret them as romantic without a shred of doubt in my mind; after all, there was a canon blushing and Aston promising to protect Takaki and his happiness was a clear-cut romantic trope, and they just seem like your typical Gundam couple, but I guess it was probably too early to establish that explicitly in canon, as Aston was most likely not ready yet to realize what his feelings for Takaki really were. Anyway, they fit into the pattern of s2's

8) policy of killing romantic couples off (followed by Naze/Amida, akilafter and shinoyama, and maybe Mika/Atra/Kudelia in the nearest future). But that's just Gundam for you, to destroy a love before it has a chance to bloom. It doesn't really qualify as queerbaiting to me, as they do this to hetero couples just as much. As for Gundam 00, I don't think that anything has been confirmed when it comes to characters' sexualities and such, but it was easy to figure out from the context. I've seen

9) a post in the general tags listing all the characters considered to be LGBTQA, so, from the top of my head - most of the named innovades are gender-neutral, from what I've gathered, with the exeption of Anew and Ribbons, I guess? The situation with Tieria is more tricky than that, though, as it's been made clear in the show that he identifies as a man, and that's how basically everyone sees and treats him; it's been also said a few times in the show that only men can be Gundam pilots and

10) I think it's about the physical build rather than how someone identifies (thus the theory about Nena Trinity being, in fact , an actual trans-girls; I've read it once on tumblr and it made a lot of sense within the story, but I can't find the post anyomre; I guess the blog has been deactivated), but then the official materias list Tieria as gender-neutral too, so it's really hard to tell, especially given the fact that Tieria has the means to produce spare bodies for himself and probably

11) decide their gender as well? So yeah, the whole situatuon with Tieria is as unclear as it can be, but one thing clear is that he identifies as a man in canon and is canonically in love with another man (Neil) even if he can't classify those feelings yet (as his letter to Lockon would suggest). I think it's safe to say that Lockon is bi; he says something about being nice to women in the show once and he clearly feels something special for Tiera (that even Feldt has noticed) and calls him

12) cute etc. I think it's safe to say Lyle is bi as well, as he literally hits on Tieria in the beginning (only to be immediately shot down, because there's already one Lockon in Tieria's heart). Setsuna is pretty much considered to be asexual (but not necessarily as aromantic, as he clearly feels something for Feldt in the movie). Alejandro Corner is gay; he's explicitly shown to be sleeping with Ribbons in the Special Edition compilation movies. There could be more, but it's hard to remember

13) everything on the spot (I should try to look fot that masterpost in the tags; hope it's still there). As for other Gundam gay couples I personally consider canon, there's Trowa/Quatre from Gundam Wing and Dearka/Yzak from Gundam Seed. Oh God, this turned out so damn long and now I'm feeling bad for bothering you and making you read all this, but those Gundam discussions are always so compelling (hope tumblr doesn't eat any of the messages; I had them saved just in case though).

Don’t worry about it; I’m always happy to discuss Gundam! Admittedly, I don’t get as heavily into Gundam as I’d like to; 00 is my favorite series, but I’ve only seen the main 50 episodes, not the movie(s). As for other Gundam series, I’ve only watched the original, Unicorn, about 1/4 of Wing, a tiny bit of Age and Reco, IBO, BF, BFT, and F91 (IBO and 00 being my favorites of what I’ve watched). I’m going to try and address every point in this, feel free to shoot another message if I miss anything important!

Admittedly, in the beginning I didn’t pay attention to IBO while I was watching. I tend to have a one-track mind when it comes to anime I like, and when I’m obsessed with one, I usually can’t bring myself to care about another, so I didn’t pick up a lot of things.

ShinoYama is, in my opinion, the least queerbaity ship in the entire Gundam franchise; I’d go as far as to say it’s completely canon, and honestly, I feel like it’s the closest we’ve gotten to a gay ship being treated exactly the same as a het ship. Yamagi obviously had romantic feelings for Shino, and Shino didn’t seem to consider it out of the question. Had he survived, I actually think they might have gone canon. Sorry if it came across as me dismissing ShinoYama as queerbaiting; I think they’re the closest we’ll ever get to representation!

It could be me caving to heteronormativity, but I feel like AkiLafter was made more explicit than ShinoYama in the “he’s being asked out on a date” department. It was handled similarly, but I still get a different vibe from it. I could be wrong, though!

Body language and wording are always a part of ships in series like this. And I feel like they were all leaning towards romantic in ShinoYama; they were heavily implied to like each other romantically. But again, it’s always just implied. None of the explicit kissing and “I love you”s that you get with things like Lyle/Anew and Naze/Amida.

I abandoned MakuGae pretty early on once Ein was introduced, so I don’t know a lot about what hints may have been dropped. And Ein and Gaelio weren’t around each other long enough for anything to be solidified. Orga and Mika, however, I feel are at least slightly indicated to have feelings for each other; it may be completely platonic, but there is such a strong emphasis on all the times that they hold hands, if one of them had been female it would have automatically been considered to be canon, even with the MikaKuuAto situation going on; which I could talk about for a long time, but in short, it’s pretty much canon, though with the KuuAto being a bit more subtle than MikaKuu or MikaAto (I am acutely aware of how Kuudelia said she loves Atra, though; that’s not something I can overlook, I’m just comparing it to the explicit MikaKuu kiss and Atra’s request to “have babies with” Mikazuki). MikaKuuAto is an entirely different subject that I’ll save for another post.

Aston and Takaki were very much hinted to be romantic. All the tropes were there, all that was missing was explicit confirmation; and there’s not a doubt in my mind that we would have gotten that had they been a straight couple. My issue with all of this, if you can call it that, is that the het ships are always made more explicit than the gay ones, however “canon” the gay ones may be. The only problem in my mind is that so many het couples have been made concretely canon, while the only gay one we’ve gotten is ShinoYama. And though there’s an equal amount of killing off between them, you’re still left with more living het couples than gay ones. Equal killing of love interests is like the difference between equality and equity; if you take an equal amount from someone with everything and someone with almost nothing, that’s technically “equal”, but the person with less inherently loses so much more than the person with everything.

I admit it’s been a while since I’ve watched 00, so I don’t remember much about it. Nena being trans isn’t something I ever picked up on, so it could have been made more clear. I definitely headcanon most of the Innovades as some form of nonbinary, but I always based “canon” for that around what pronouns are used for the characters; and in all of their cases, it was always he/him or she/her. With Tieria, it was mostly a headcanon spawned from the episode where he crossdressed to infiltrate that party, and how easily the female form and voice came to him; hell, on Wikipedia’s “List of transgender characters in media”, Tieria is listed there. Later in Season 2, though, he’s portrayed as being a cis male, so that somewhat threw my headcanon of him being a trans boy out of the window. I also heavily headcanon Regene and Revive as trans boys, though solely because of their voices. Really, though, the pairs like Regene and Tieria or Anew and Revive; they’ve been stated to share the exact same genes, so in same-gender pairings, neither or both of them are trans, and in different-gender pairings, one of them has to be trans.

I do think it’s implied that Tieria loved Neil, but again, it was never made as painfully explicit as things like Chris and Lichty, Anew and Lyle, Naze and Amida, etc etc. Tieria obviously cared a lot for Neil, and never really got over his death; but I still feel that it was never made as clear as those other ships whether the feelings were platonic or romantic.

As I never saw the movies, I didn’t know about the thing with Alejandro and Ribbons; if that’s a thing that happened, then I definitely have to see the movies. And though I never fully watched Wing, I did pick up on something between Trowa and Quatre, but still; Never hinted at as much as Heero and Relena.

Wow, my response ended up almost as long as your questions. You don’t have to worry about bothering me; I very much enjoy talking about Gundam! If I missed any points you made, don’t be afraid to send me another message~

#gundam 00#gundam iron blooded orphans#gundam ibo#gundam tekketsu no orphans#g tekketsu#gundam wing#Anonymous

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CanvasWatches: Haibane-Renmei

Should I start doing the (Re)Watches thing again, or is that a superfluous detail? On one hand, it provides information that it’s a review not based on my very first impressions, but on the other, is it really necessary?

Anyways, I rewatched Haibane-Renmei. I like it? It’s… it’s a nice little thing. Arty, imaginative, and dark without being outright pretentious about it. Class act. You should go watch it.

Seriously, it’s the type of show that… well, it doesn’t live or die by being unspoiled, but it’d be difficult to discuss without both participants having the context of seeing it. It’s one of those shows that’s more about aesthetic and tone than actual story.

It’s on Funimation at least, and I’m not even being sponsored to carefully, yet firmly shove you in it’s general direction! I just really like dubs and want to support them.[1] Also, it’s on Youtube, legally.

Go watch it. I’ll wait for you. After the page break.

So, one of the lessons one should study from the show is world building by suggestion instead of explicit dialogue. The show is a rare example of pretty much the entire cast knowing very little about what’s up with the fantastical elements, and those who might know something aren’t talking.

Heck, the guys likely to know something use a sign language just to avoid people requesting exposition. The jerks.

As a consequence of this, based on the piece by itself, I can’t conclusively tell you what The Deal with everything is, merely speculate based on imagery and random details.

I mean, the Haibane have a lot of Angel Imagery about them, and they’re… hatched? Born knowing how to walk and talk, and though they have no memory, and yet, based on Rakka’s experience, they feel as if they should remember something, but come up blank.

So I think it’s probably a purgatory thing, much like Angel Beats! wherein the residents have emotional baggage holding them back.

Except the Haibane don’t remember what traumas they might have, so it might be a more inner peace sort of thing?

I could also be totally off base, which is also exciting.

It’s that very aspect that makes this an important lesson: Haibane-Renmei works with being vague about its world because that’s what the story calls for. Other narratives, where you can’t take the fantastical elements with casualness, require exposition.

Basically, Haibane-Renmei is a benchmark for one end of the exposition scale. Stare at it, and hopefully I can find it’s partner at the other end.[2]

There are things about the world you can deduce and interpret, and admittedly ascribe. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter too much, as the actual central narrative is first about Rakka learning about the world she’s suddenly born into, then Reki overcoming her internal struggles with the help of Rakka.

Which is probably a metaphor about depression.

Look, I’ve always held the philosophy of ‘It’s nothing without a good surface story’ and despise when media tries to push vaguely defined symbolism and “Hidden Meaning” as the focus. If I can’t understand it on a first viewing, you have failed.

Haibane-Renmei does that correctly. On the first viewing, I had lingering curiosities, but I was mostly invested in exploring the world and solving what Reki’s big problem is.

And, now that I know those things, I am willing and able to enjoy a second viewing where I can analyze whatever bizarre elements are in the borders, because the creator put in the work of making a strong focal story that isn’t desperate to discard Unworthy Viewers.

Someone I’m particularly drawn to is The Communicator, who is sort of community leader for the Haibane, and thus the person probably most informed by what is going on, but at the same time is of the ‘vague lessons’ school that The Sphinx satirized.

He’s what the professor of a story analysis class I accidentally[4] took might call ‘The System Character’: a character that represents a system the protagonist is (supposedly) fighting against.[5]

The Communicator’s actually a very compassionate but reserved man, who clearly cares for his charges while trying to remain emotionally distant from these beings who, by their very nature, are destined to leave. He is the chief executor of the laws and customs that govern the Haibane, but will allow them to be broken or stretched whenever they’d be hindering. For example, he’s notably lax about Haibane speaking within the temple, which is supposedly forbidden, and eventually gives Rakka a job maintaining the structure Haibane must never touch.

And I think that’s because, over the last five years, The Communicator has realized that being overly restrictive may have doomed Reki, and built a divide that makes him incapable of helping her.

So, now, he needs to use Rakka to save the artist’s soul, but mindfully so as not to accidentally condemn Rakka. It’s subtle, but The Communicator keeps a close tab on at least Old Home and its going-ons, and when the more naive Rakka begins going through the same struggles as Reki is suffering, The Communicator identifies how Reki’s found a kindred spirit, and now can teach and help this New Feather, then aim her to help the Haibane he fears he’s going to lose.

It’s also implied that he, too, has failed to take flight, and wishes the pain of this failure on no one.

Then again, this might be things I’m just ascribing. But it doesn’t matter, because that’s not the point of the show. Its point is to bring the viewer into a new world and tell a pleasant story within it.

I’ve always had an odd fascination with Death Mythology stories. From Anthropomorphic Personifications to what comes after, if you make Death a character or show me what comes next (even just portionally) you’ll have my attention.[7] And it shouldn’t be surprising, since death’s such a scary thing that looms over everyone, with some many unknowable questions, that of course humanity would try to answer these questions.

And Purgatories are bizarrely compelling because the implied existence of a transition world, where you go from an impermanent life to an equally impermanent realm. Heck, Dante’s own depiction portrayed it as climbing a mountain as you overcome your sins before finally being granted access to Paradise.[8] To go through the trial of life, only to find yourself before yet another trial is fascinating.

And the town of Haibane Renmei, Glie, is fascinating as far as Purgatories go, since not only can you die there conventionally, but there’s assumably mortal humans residing there, working jobs, living life, having babies, but also all forbidden from exiting the walls that surround the town, which explicitly has an outside world that is travelled by nomads known as Togas (who might be failed Haibane).

It’s also stated, explicitly, that Haibane that fail to take their day of flight will lose their halo and wings, and will grow old and die.

What does it mean to die in the afterlife? Where do you go? And what are the townspeople? Are they also deceased, but following a different path to salvation? Or are they mortals, and Glie is somewhere in the real world, like Baum’s Oz?

These are the sorts of Death World-building questions that excite me, and don’t have answers or are particularly addressed, and I’m not dissatisfied about that. Partly because, again, there’s a focal narrative, and partially because I appreciate having world elements just because that’s how the creator wants it to be, without any meaning behind it.

It’s okay to just have blue curtains.

Still, this is an Anime about Death and Depression, even if no one says so on screen.

We witness two characters pass on and go beyond the wall, and depression wreck our protagonists.

Kuu’s Day of Flight is viewed by most as good and right, and they move on. Rakka, of course, wasn’t properly informed about it, so was taken by surprise and fell into depression.

But the actions Kuu takes leading up to it…

So, I’m not a medical practitioner, and I’m not sure if I suffer (or have suffered) depression, so I’m basing this next bit of analysis on the word of mouth information that gets passed around. However…

Kuu’s shown to be upbeat as she goes about, tying up loose ends, granting vague good-byes to others in her life, and gives away her possessions (highlighted by Kuu giving her favorite coat to Rakka). While the upbeat personality didn’t come suddenly, this is still frightfully similar to suicide warning signs you’re supposed to keep an eye out for. This is the healthy “Death” of the series.

I’m sure the similarities were accidental, but it’s still intriguing.

In contrast, there’s Reki’s depression and suicide attempt.

The lead up shows her being more isolating, moving out of what was once her room and into her studio, where she desperately paints, trying to remember her cocoon dream, and no one but Rakka takes much notice, as only Rakka and Nemu know about Reki being sin-bound, and Rakka’s the only one to go through it personally.[9]

The sequence and final episode is emotional. Even as Reki prepares to be crushed by her train, she doesn’t really want to leave, and she even identifies what she needs to do to get out of it (ask for help), but still finds herself unable. Even when Rakka arrives to try and help, presenting Reki with her true name, Reki still rejects it (probably not helped by the fact that the Communicator’s first story amounts to ‘Well, your lot is to end in pain. Shrug Ascii.’) and Reki says things she knows will hurt Rakka, things that Reki tells her are true, that Reki never cared for Rakka, she just needed someone for one last attempt at being normal.

And so, Rakka leaves, and finds Reki’s diary to confirm that, no, Reki’s not actually that self-serving, and the depressed artist does still care.

So, Rakka returns, but it’s nearing too late, and Rakka is unable to help until, finally, moments before the end, Reki finally asks for help.

And gets it. So that’s nice.

However, Reki still leaves that same night, narrated by the Communicator’s revised story, as Reki’s True Name has changed to what she’d been using the whole time.

Because Reki, by putting on a mask and going through the motions for selfish reasons, was still doing good for others and living life. She kept trying, and eventually she ceased being her true self and was absorbed into her mask, which was also happened to be a healthier person.

Really, the one change I’d make is to delay Reki’s day of flight by at least a couple days, let the girl finally enjoy sunlight unhampered, and go around making amends for the wrongs she did and the wongs she received.

Have her meet with the Communicator first, both of them seeking repentance from the other, then have the Communicator tell his revised story over images of Reki returning to Abandoned Factory and making amends, playing with young feathers at Old Home, spending some time with Nemu, then a few scenes of her closing loose ends like Kuu before taking her day of flight.

I just didn’t like Reki surviving her suicide attempt, only to die that night anyways. I know life’s like that, but I think we could allow a little more fantasy in our town inhabited by angels.

I wish I could transition through my flippant ‘well, I could be wrong, art’s mysterious’ but I hate that mentality. I try to be open to being wrong and corrected, but I don’t like being indifferent, and I’m always annoyed by artists that embrace Death of the Author. It’s your work, your art, your creation. It has a part of you in it, that’s how art is created. You have authority over your story, don’t shrug that off. Embrace it.

Which… I think Haibane-Renmei doesn’t do that. Obviously, there’s a translation barrier, and I’m going off of TV Tropes, but when ABe (sic) says he’s keeping explanations vague to allow viewer interpretation, it feels less flippant than… cuss it, I’m naming names… less like Adventure Zone (Balance Arc) and Runewriters,[10] which have more concrete worlds and tones more towards telling a complete story, yet the creators have gone on record saying any peripheral material they produce or say has the same weight as any fan theory made by the audience.[11]

Haibane-Renmei, as a story and a piece of art, thrives off those vagueties. Rakka’s not sure exactly what’s going on, because her fellows are also working off an incomplete picture, because no one’s given a complete portrait. As such, the viewers are also kept unsure, because that’s what our viewpoint character is always feeling.

It’s set in a town literally closed off from the rest of the world, whatever that world is, because no one is allowed past those walls.

ABe gets to be vague because revealing concrete details would make this particular art weaker.

The work earned it.

I… really should do an essay on Death of the Author, and its use by modern critics and artists. Because I so hate it.

Well… that was my Rewatch of Haibane-Renmei, and harsh criticism of two Literary Criticism theories.

I really love this series. It’s an anime I think everyone should see, for it’s message and artistry.

I’d be happy to hear your thoughts or questions, because I like going off on weird tangents. Maybe, while you’re here, consider checking out my other works, and if you like what I’m doing, I’ve got a Patreon. Local businesses won’t accept the pages out of my notebooks as payment, after all.

Kataal kataal.

[1] Then again, Funimation, if you’d like to… the My Hero Academica Review got, like, three notes! Eh?

[2] Needs to be exposition heavy, but still narratively satisfying.[3]

[3] I hope it’s not Tolkien. I hate Tolkien.

[4] I thought I was signing up for a storytelling class. But, no, it was an ego stroking class on the teacher’s personal analysis method, that was ultimately horribly reductionist. The useful stuff can be found on TV Tropes (better executed) and the rest was chaft. Lady literally thought she could graph comedy, and was too proud to play Pac-Man.

[5] The fact that Rakka happily works within the system, and Reki’s problems spawn from rebelling is a good example why the professor of Footnote 4 is wrong.[6]

[6] I have a lot of lingering resentment, and must now try not to spend this review tearing apart an unknown literary theory.

[7] Though you still have to keep it. Watched an amount of Soul Eater while I was home sick from school, but I feel no draw to return to it.

[8] I strongly recommend Overly Sarcastic Productions video on Purgatorio for those interested in finding out about The Divine Comedy’s Empire without actually reading it.

[9] Also, they take medicine to hide the signs, though the black wings still remain.

[10] Sorry, Shazzbaa. We cool?

[11] Any further thoughts probably deserve an essay onto itself.

0 notes