#the moral is that there are labor unions in heaven also.

Text

casey jones the union scab is a good song

#the moral is that there are labor unions in heaven also.#box opener#labor#im memorizing as many union songs as possible because roughly once every six months#i am in a situation where the only people singing the song at the rally#whatever rally it might be#are 1. THE GUY LEADING THE SONG#2. ME#so. i must be prepared#THE ANGEL'S LOCAL NUMBER 23‚ THEY SURE WERE THERE

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

However, there is someone who looks a bit like Eichmann in this experiment: Milgram himself. The volunteers were pretend torturing people and experiencing acute stress. Milgram, though, does not appear to have experienced any stress while actually torturing people.

Milgram’s researchers psychologically bullied and abused their volunteers, to the point where they stuttered, panicked, and again, in some cases actually experienced seizures. Terrorizing people into experiencing seizures is reasonably described as torture. Milgram’s experiments can’t be reproduced because psychologists today recognize that it is unethical to torture people, even if you are torturing them in the name of better understanding torture.

...

Milgram’s experiments suggest that the main source of evil is not obedient bureaucrats indifferent to morality, but powerful leaders convinced of the righteousness of their actions.

Milgram and (presumably) his research assistants and colleagues believed that they were doing important work in understanding fascism. That trumped concern for their own volunteers—volunteers who the study itself was designed to reveal as weak, unthinking, and morally flawed. Milgram was the important knower, and what he set out to know was that his own volunteers were inferior. Add in Milgram’s own career ambitions and incentives, and you have a formula for violence, abuse, and a cover-up of that violence and abuse.

Milgram set up an experiment to prove that the unquestioning immorality of flunkies is the chief danger facilitating fascism. But what he ended up demonstrating instead is that arrogant leaders in the grip of ideology and self-aggrandizement can excuse just about any violence directed at those they consider inferior. The mix of ideological conviction and entitlement is extremely dangerous.

So, like the Nazis before them, Trumpists want to install fanatic loyalists who believe they have the mandate of heaven (literally) to torment and torture immigrants, women, LGBT people, labor unions, and political opponents. MAGA understands, unlike Milgram, that people are not drones, and will not just implement evil because their boss said so. But they also know, as Milgram demonstrated, that if you tell people they have a righteous cause, and that they are entitled to advance that cause at any price, you can enable atrocities.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi bitches, I'm a bit nervous to ask this but I'm being genuine I promise. I don't want you to think I'm some biggoted old fool.

Could you please help me understand how sex work isn't exploitative? I hear a lot of people saying "it's just the same as normal work, it's better than my job at Amazon/target/wherever and no one is calling that work exploitative" or "well you wouldn't do YOUR job if you didn't have to either" but like, checkout work IS hella exploitative??? Most work IS hella bullshit that only exists to feed the capitalist machine. I DO fight for a world where work is a choice. I understand why The Right would love onlyfans, but why is The Left lining up to defend it?

Sex work - especially things like onlyfans - is overwhelmingly done by the poor or as a way to escape poverty ("I was being paid shit in my previous job, now I can afford an apartment" is something I hear a lot). But in doing so it transfers all the risks to them, it's essentially turning sex work into the gig/hustle economy, isn't it? You end up on a zero hour contract with no union, health, benefit, maternity protection, in a job that can be hella dangerous and have serious emotional repercussions and requires huge emotional labour and/or disconnect and I don't really understand why we're just cheering this along?

I don't object on moral grounds. Sex is sex. Consenting adults do what you want. People are well within their moral and legal rights to choose to sell sex, (or the emotional labour that comes with it), or photos, or whatever they want - just like they are free to go work for target. I absolutely understand the need to - and support - decriminalisation of sex work, the need to make it safe and secure for sex workers, but I just can't see why ~the world at large~ sees huge numbers of young 18 year old women being herded and encouraged into joining Onlyfans - in several cases with people saying "can't wait for you to turn 18 so you can have an OF" so the patriarchy can pay £3-4 a month to see their tits and people cheer this along? One or two get rich, I'm sure, but who is getting REALLY rich? It's the old white men that own onlyfans and take a 20% cut, as always. It's the patriarchy working as it always has. Allowing one or two women to succeed while holding the rest down for exploitation. Except now it's mixing with the worst bits of 21st C capitalism, too. Surely all OnlyFans is is Uber for Sex work, using the gig economy to de-unionise and isolate workers, strip them of benefits, make them into independent contractors and profit off them?

Sure, it's a step up from kidnapping girls from Romania to have them do porn, but is that really the bar? Can we maybe just stop for a second and imagine a world where rich white men don't get richer off the emotional and physical labour of women? Where the other available work options aren't so shit that a zero-hour career with no employment protections, a limited lifespan, in a dangerous industry doesnt look like heaven in comparison? Sure, you can work for three years, sell your emotional labour, and pay for college. But why are we cheering that instead of asking why this has to happen in the first place? We're fiddling around the edges of the system, giving it a makeover, and rebadging it "female empowerment" instead of actually changing anything fundamental. Poor women sell sex. A few are allowed to break out. Men get to leer at naked women for pennies a year. Rich men get richer. Plus ça change. Not even to mention that because of the ~emotional~ connection that onlyfans gives beyond porn, we're embedding the idea that women are "money in, girlfriend out" machines. I know several girls that won't even *talk* to men in any situation without a minimum $50 fee. And apparently the fact we also have a crisis of men so lonely they're willing to pay this isn't a problem either? Where's our luxury communism dreams bitches?

Bitches, I trust you. What am I missing?

I don’t think you’re a bigoted old fool. Nor a prude! I think you’re incredibly enlightened about the dangers of unfettered capitalism and labor exploitation.

Almost all of the issues you highlight about exploitative sex work can be said about exploitative labor in any industry. Poor people taking shitty jobs that don’t pay enough and enrich capitalist, patriarchal corporate overlords? That happens all over the world in industries from meat packing to clothing sweat shops to, yes, sex work. The exploitation of a person’s body for labor is an ethical stain on our culture at large. It’s why we’re so in favor of labor rights advances including a higher minimum wage, unions, and humane work environments.

Raising the Minimum Wage Would Make Our Lives Better

Are Unions Good or Bad?

Coronavirus Reveals America’s Pre-existing Conditions, Part 1: Healthcare, Housing, and Labor Rights

Sex work is not unique in that it opens desperate and poor people up to labor exploitation. It’s not even uniquely dangerous to the bodies of workers--John Oliver did a bit on the US meat packing industry recently that made me faint with body horror.

So we agree that labor exploitation is bad. And it’s something that we should work towards ending in every industry. But I can see why some people would view exploitative sex work to be a different kind of bad. Because sex is sensitive! It can be used to punish and hurt. See revenge porn and the way synonyms for “sex worker” are stigmatized and used as insults throughout society.

Now, a few clarifications. When I refer to sex work, I’m not just talking about cam work on OnlyFans. There are lots of other outlets for many different kinds of sex work. And I’m also not just talking about women sex workers. People of all gender identities and sexualities do sex work, and we should advocate for fair labor practices and safety for all of them. I am firmly pro- decriminalizing sex work so that the industry can be made safe, regulated, and destigmatized in an effort to reduce exploitation. I want sex workers to have the power of collective bargaining! I want them to be protected by law enforcement and our justice system, instead of targeted by it! I want them to pay taxes and have the privileges associated with all tax paying workers! I want them to have the power and protection of a regulatory industry that will purge abusive and violent clients from their field!

I also disagree with the characterization that choosing sex work freely, even out of desperation, is a “step up from kidnapping a girl from Romania to have them do porn.” Human trafficking is not sex work. It’s slavery and torture. Even when the choice is between making $7.25 an hour working at WalMart and making $7.25 as a cam girl, there’s still a choice involved, even if it’s a shitty one. There’s consent. Trafficking victims have no choice, no consent, only violence.

I honestly don’t want to start a debate here. We’re all on the same page that labor exploitation is bad. So I’ll just end with this: not all sex work is inherently exploitative. Which I guess is your real question!

I’ve mentioned before that I have friends who are former sex workers. Specifically strippers and a specialty dominatrix. As with any job, they had their ups and downs, their good nights and bad nights. But they all agree that they freely chose the work not out of desperation or a lack of other options. And they even enjoyed the work in some cases. If someone prefers sex work, thrives in giving that emotional labor to others, I’m not going to judge and I’m certainly not going to tell them they’re being exploited. It would frankly be insulting, condescending, to tell someone that their choice of work (when it truly is a choice) is bad for them.

It’s a fine line, but the line does exist. Sex work CAN BE exploitative. But it is not inherently exploitative, as far as I’m concerned.

222 notes

·

View notes

Note

If someone invaded your home state, burned down homes and businesses, requisitioned your food to supply their army, took your car, shot local authorities as traitors, and told you they were doing all this for some higher moral purpose, what would you do? Now pretend its 1861 and you live in Virginia. Did your answer change? Defending slavery did not bring all those soldiers to the battlefield, defending their homes did. That's an important distinction.

you mean like what the Confederacy did with the Conscription Act of 1862, which was mostly intended as a way to forcibly induct pro-Union southerners or give the government an excuse to confiscate their holdings? Or how books like Cannibals All! existed before the war and posited that black people needed the slave-labor structure of the south and the Confederacy’s idea of religion to have a chance of getting into heaven? Or how even guys like John Mosby stated in their own writings that they “never heard of any other reason besides slavery” as the impetus behind the war?

And as I’ve said of Robert E. Lee, if he and the rest of his god-bothering rabble had a tenth of the moral fortitude they liked to present they’d have sided with Lincoln and found a way to end the war as bloodlessly and as quickly as possible. After all, his own cousin did the same because in his own words “there was no Virginia in my oath of office, only the United States”.

Also, the Louisianan troops marched a hell of a long way if they were only concerned with protecting their homes, didn’t they?

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red Umbrella Struggles

Image from: @Lilla Szász: Mother Michael Goes to Heaven (2008-2010)

Red Umbrella Struggles

April 18–June 23, 2019

Conversation: April 17, 5–7pm, with the artists featured in the exhibition

Opening: April 17, 7pm

Edith-Russ-Haus for Media Art

Katharinenstraße 23

D-26121 Oldenburg

Germany

www.edith-russ-haus.de

Facebook

Artists: Petra Bauer & SCOT-PEP, Louise Carrin, Daniel Jacoby, Ditte Haarløv Johnsen, Tadej Pogačar, Lilla Szász

Red Umbrella Struggles is an international group exhibition that revolves around the controversial and multifaceted topic of sex work. The show takes its inspiration from two newly commissioned projects by Edith-Russ-Haus’s 2018 Media Art Grant holders, Petra Bauer and Daniel Jacoby. Both artists are interested in investigating the topic through strategies of collaboration and dialogue.

Rather than merely representing and picturing sex workers and their industry, the artists of this exhibition, through means of conversation, move the emphasis from voyeurism or victimization to questions of dignity and rights. In acknowledging that sex workers are experts on their own lives, these artist projects look at how the complexities of gender, migration, and labor are involved in this battlefield of ideologies.

Swedish artist and filmmaker Petra Bauer has been working on a film project with SCOT-PEP, a sex-worker-led organization in Scotland, for the past three years. The result of their collaboration, Workers! (2019), was filmed inside the Scottish Trade Union Congress, a building rooted in workers’ struggles for rights and political representation. During their one day “occupation” of this institution, conversations unfolded that center the voices of sex workers in the discussion of their own labor and lives.

The complex exhibition installation includes the historical forerunner of Bauer’s work, Carole Roussopoulos’s documentary Les prostituées de Lyon parlent (1975). The film follows the story of the occupation of a church by 200 sex workers in protest of police harassment and dangerous working conditions. Workers! also takes inspiration from Chantal Akerman’s iconic Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), which depicts the daily routine of Jeanne as a mother, housewife, and sex worker. Bauer’s film is likewise a tool for exploring debates on women’s work beyond the polarizing divisions prevalent in feminism, both past and present.

The video work Expression of an Egg (2019) by Daniel Jacoby takes the sleepless flow of live-stream webcamming sites as its source material. The realm of camming has grown incredibly fast over the past decade, facilitated by higher bandwidths and cheaper technologies. Expression of an Egg navigates a series of vaguely articulated images that eventually lead to a deeper connection with the online persona of one individual: webcam BDSM performer Matt, with whom Jacoby began virtually collaborating on the staging of a fiction. Using Hiroshi Teshigahara’s movie The Face of Another (1964) as a reference and the live stream as a filming device, Jacoby’s video zeroes in on Matt as its protagonist. In an effort to relate to the main hero of the Japanese film, whose life is drastically affected when he’s given a prosthetic face, the webcammer creatively adapts scenes of the original film to his current camming avatar: a transvestite bimbo. Through symbols borrowed from Teshigahara, Matt attempts to represent a feeling of alienation present in the camming world that is potentially transferable to modern urban society at large.

The exhibition title, Red Umbrella Struggles, references the international symbol of the sex workers’ rights movement, which was first used in 2001 during a performative event organized by the Slovenian artist Tadej Pogačar for the 49th Venice Biennale. The Red Umbrella March was part of Pogačar’s participatory project CODE:RED (1999–), which researches and discusses various aspects of sex work as a specific parallel economy.

The exhibition presents various iterations of Pogačar’s project, which, like Bauer’s, positions itself both as an artwork and as in service of the struggle for labor rights. Other works in the exhibition focus more on specific features and characteristic of this particular type of labor.

Lilla Szász’s photo installation Mother Michael Goes to Heaven (2008–10) is the result of a long-running collaboration and friendship with a group of sex workers in Budapest. The series portrays experiments in queer family structure by following the lives of its subjects as they protect and support each other on the boundaries of society, in a position riddled with precarity and insecurity.

In One Day (2007), Danish film director Ditte Haarløv Johnsen represents the hardships of motherhood and the suffocating reality of migrant labor by following a day in the life of a West African sex worker in Copenhagen. Meanwhile, striking a lighter note, Louise Carrinlets us imagine through her documentary Venusia (2016) the boring and dull moments that also attend this job, aligning its ins and outs with any other type of work routine.

The various political and moral discourses on sex work tend to deprive sex workers of their voice and pose difficulties to their attempts to differentiate and shape their own identities. Red Umbrella Struggles pictures this social struggle of this marginalized profession, which is mirrored in the mutual support likewise involved in the artist collaborations.

Workers! by Petra Bauer and SCOT-PEP is showing concurrently at Collective, Edinburgh, Scotland, April 12–June 30, 2019.

https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/252773/red-umbrella-struggles/

#www.szaszlilla.hu#https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/252773/red-umbrella-struggles/#https://www.edith-russ-haus.de/home.html

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Human Rights Visual Art

Human rights/social justice visual arts

Visual art is a medium of self-expression in today’s society that allows for individuals to share their experiences and voice their opinions. Those who are denied human rights, or those who advocate for human rights, use visual art to express world suffering. According to Amnesty International, in 2017 the United States was one of the top ten human rights abusers in the world. The United States has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world, laws that allow family separation, and permit cheap labor without giving the illegal immigrants any rights (AMNESTY). To think a country so advanced is yet so behind on the moral values for human life, it seems unbelievable. While the vast majority of American society may not be as aware of the significant human rights violations worldwide - there are a few visual art artists who are bring awareness to these specific issues. Banksy, Benny Andrews and Ralph Chaplin are three modern artists who are known for their human rights activism.

“United States of America 2017/2018.” Early Marriage and Harassment of Syrian Refugee Women and Girls in Jordan, www.amnesty.org/en/countries/americas/united-states-of-america/report-united-states-of-america/.

“US Turning Its Back on Human Rights.” Human Rights Watch, 29 June 2018, www.hrw.org/news/2018/06/29/us-turning-its-back-human-rights.

Banksy is a well known street artist who leave his work anonymously and silently across the world in signinfance places at the most crucial times when awareness needs to be raised for a certain cause. The image below is a specific street art work by Banksy is a playful twist on rebellion. It is a great example of how Banksy tries to convey his art to the public - a powerful message through an original, intriguing perspective. The image depicts a young adult man clenching a bouquet of flowers in his fist ready to throw them towards a direction his body is pointing towards. From the aggressive body language of the man, the black scarf across his face, the dark and white contrast of his clothing, it is evident that the bouquet of flowers is completely out of place in this image. It seems as though the man was meant to be holding a spear, rock, gas bomb - a weapon not a heap of colorful, peaceful flowers. The tension and anger on the man’s face also contrasts with the gentleness of the flowers.

The podcast link below also discusses the relation of Banksy's work to political movements and how it relates to other similar movements around the world. The podcast discusses the specific use of graffiti that compliments Banksy's artwork and its motive. The idea behind graffiti art is that it it is just as illegal as the protests behind the movements Banksy is trying to represent. There is plenty of controversy on the topics that Banksy tries to represent. He raises the voices of those who cannot be heard through contrasts of color and darkness. He represents the good and the evil in simple images that send human rights based messages.

(Banksy's street art - Donaghy, Kieran. “Human Rights Street Art.” LinkedIn SlideShare, 27 Oct. 2011, www.slideshare.net/kierandonaghy/human-rights-street-art. )

PODCAST: “The Politics of the Visual 2: Street Life.” Pod Academy, podacademy.org/bookpods/politics-of-the-visual-2/

Benny Andrews is another well known human rights visual artist. Andrews is an African-American artist known for his modern artwork that revolves around human rights. His more modern painting strategies give his art more sophistication that Banksy's street art. The image below is a famous image by Andrews depicting an African-American man standing on yellow land with a simple contrasting blue sky background. In the center of the image the man stands looking at the sky and seemingly crying out in despair. The man is almost expected to be a giant in the image as he stands hunched over as if in pain. The man seems to be African-American as well. He stands barefoot and with no eyes on his face. The artist depicted this specific image this way to represent human right as it takes away from the individualism of the character if the individuals eyes are not showing. The man’s cry out in despair strives to show his suffering and pain, he stands barefoot on the yellow ground in order to show that his feat may be burning on hot floor. The name of the artwork collection this painting is from is also called “There must be Heaven”. This shows that the work of art was created in the African-Americans hope there must as better place they may go to because of the suffering they have endured on Earth.

The video link below is also a description of the civil rights the Andrews artwork wanted to portray. It shows several different pieces that provide a similar message for human rights as the one described above.

VIDEO: Boondoggle, director. Benny Andrews - in His Own Words. YouTube, YouTube, 27 Aug. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=d9u_35nSgoo

(Benny Andrews image - Cimakh. “The Importance of Art in Human Rights.” UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog, 16 Apr. 2018, cas.uab.edu/humanrights/2018/04/20/the-importance-of-art-in-human-rights/.)

Ralph Chaplin

An example of a historic human rights activist is Ralph Chaplin. The image below is one of his activist work that served to provide hope and advocacy for labor workers. The drawing below is his famous work named “The hand that will rule the world - One Big Union”. In 1917 this clenched fist symbol meant independence for the workers as machines began to take over their jobs and cause job loss for a majority of people. The drawing by Chaplin was a controversial yet popularized image as a white, privileged man stood up for the rights of the people. The image purposefully has the men standing below the industry factories in the distance with the fist rising above them as they unite in order to show that they are stronger together and that their solidarity comes from their union.

(Ralph Chaplin image - Cimakh. “The Importance of Art in Human Rights.” UAB Institute for Human Rights Blog, 16 Apr. 2018, cas.uab.edu/humanrights/2018/04/20/the-importance-of-art-in-human-rights/.)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tarot Card Meanings of the Empress Tarot Card

Sticking to the High Priestess comes the Empress. The appointed number of her is 3, which represents union, fertility, procreation, and completion. Simply because the High Priestess represents 2 opposing forces, the Empress follows with the launch of a brand new, unifying principle. She's the card of creation. Thus, the Empress is related with productivity, new energy, creativity, and childbirth. The Empress will be the mother of all the things and personifies the innovative power related to the natural planet. She's the mother earth using the energy of its to drive the feminine wisdom of her across the universe.

over here Galapagar

In a Tarot card reading, the Empress rules the actual physical world which that is definitely physical. Usually, we discover an eagle by the side of her that symbolically represents the bridge between earth and heaven. Unlike the Magician, the power of her is feminine and passive. She depicts the world of emotion, not the realm of thought. The association of her to the heavens is dependant on the concept that work that is hard and ingenuity is able to result in a spiritual awakening.

In the daily world, The Empress represents feeling. She's sympathetic and fair and bases the decisions of her on the moral value system of her. She's focused on the household and concerns herself together with the good of the community of her. The Empress is an all natural diplomat and understands the issues everyone is confronted with. Thus, she's there to console and also offer the wisdom of her.

Among the bad Tarot card meanings connected with the Empress could be her over protectiveness and also maternal domination. She is able to impede the improvement of the soul's journey by over indulging in the role of her as the very good mother. Must this be put on to men in a Tarot reading, the Empress is able to forewarn of a male extremely connected to the mother of his. He might be powerless to get a committed and healthy relationship, since he might too frequently, may it be subconsciously or consciously, examine his partner's traits to those of his mother 's.

Upright Empress Tarot Card Meanings In a Tarot Reading

In a Tarot reading, the upright Empress card signifies very good fortune. The Empress is indicative of all the things creative, which means you are able to rely on the own creative endeavors of yours achieving success. The hard work of yours is going to pay off both materially and spiritually. You are going to be ready to anticipate material and spiritual abundance through the initiatives of the labor of yours. The Empress additionally indicates a birth or maybe marriage and will represent a gratifying sexual relationship. She encourages you to draw on the feminine power of yours. Know that much can be accomplished by generosity and nurturing. If you are surrounded by difficult folks, the most effective way is diplomacy. When you have problems regarding well being, the Empress represents healing.

The Empress additionally represents beauty. She likes surrounding herself with luxury. The Empress Tarot Card is able to indicate the purchase of things that are new. This's especially true of products that make the home of her much more comfortable and eye appealing.

• Motherhood

• Fertility

• Beauty

• Prosperity

• Abundance

• Nurturance

• Diplomacy

Reversed Empress Tarot Card Meanings In a Tarot Reading

The Empress card reversed in a Tarot reading is able to signify an inventive block. You might find your mood depressed & bad. Work is able to feel mundane and laborious. Financial matters are usually tested, and you might find you're striving making ends meet. There might be a general lack of abundance. Spiritually, the Empress reversed might signify you're being way too greedy with the emotions of yours or maybe you might be holding onto the money of yours too tightly. The Empress warns you being generous to those you like. In a Tarot reading, the Empress reversed might also indicate problems with pregnancy. Be careful of an unwanted pregnancy, practice safe sex and. You may additionally be overprotective of a person you like, which is straining the relationship of yours.

• Creative blocks

• Unwanted pregnancy

• Financial troubles

• Greed

• Holding on way too tightly to one 's feelings

• Depression

check these guys out tarot en Santa Pola

0 notes

Text

we’re conserving a promise

of life in the eternal and of all of True nature being restored.

Today’s reading of the Scriptures from the New Testament is the 15th chapter of the Letter of First Corinthians where Paul writes of this pure hope:

Dear friends, let me give you clearly the heart of the gospel that I’ve preached to you—the good news that you have heartily received and on which you stand. For it is through the revelation of the gospel that you are being saved, if you fasten your life firmly to the message I’ve taught you, unless you have believed in vain. For I have shared with you what I have received and what is of utmost importance:

The Messiah died for our sins,

fulfilling the prophecies of the Scriptures.

He was buried in a tomb

and was raised from the dead after three days,

as foretold in the Scriptures.

Then he appeared to Peter the Rock

and to the twelve apostles.

He also appeared to more than five hundred of his followers at the same time, most of whom are still alive as I write this, though a few have passed away. Then he appeared to Jacob and to all the apostles. Last of all he appeared in front of me, like one born prematurely, ripped from the womb. Yes, I am the most insignificant of all the apostles, unworthy even to be called an apostle, because I hunted down believers and persecuted God’s church. But God’s amazing grace has made me who I am! And his grace to me was not fruitless. In fact, I worked harder than all the rest, yet not in my own strength but God’s, for his empowering grace is poured out upon me. So this is what we all have taught you, and whether it was through me or someone else, you have now believed the gospel.

The message we preach is Christ, who has been raised from the dead. So how could any of you possibly say there is no resurrection of the dead? For if there is no such thing as a resurrection from the dead, then not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, all of our preaching has been for nothing and your faith is useless. Moreover, if the dead are not raised, that would mean that we are false witnesses who are misrepresenting God. And that would mean that we have preached a lie, stating that God raised him from the dead, if in reality he didn’t.

If the dead aren’t raised up, that would mean that Christ has not been raised up either. And if Christ is not alive, you are still lost in your sins and your faith is a fantasy. It would also mean that those believers in Christ who have passed away have simply perished. If the only benefit of our hope in Christ is limited to this life on earth, we deserve to be pitied more than all others!

But the truth is, Christ is risen from the dead, as the firstfruit of a great resurrection harvest of those who have died. For since death came through a man, Adam, it is fitting that the resurrection of the dead has also come through a man, Christ. Even as all who are in Adam die, so also all who are in Christ will be made alive. But each one in his proper order: Christ, the firstfruits, then those who belong to Christ in his presence.

Then the final stage of completion comes, when he will bring to an end every other rulership, authority, and power, and he will hand over his kingdom to Father God. Until then he is destined to reign as King until all hostility has been subdued and placed under his feet. And the last enemy to be subdued and eliminated is death itself.

The Father has placed all things in subjection under the feet of Christ. Yet when it says, “all things,” it is understood that the Father does not include himself, for he is the one who placed all things in subjection to Christ. However, when everything is subdued and in submission to him, then the Son himself will be subject to the Father, who put all things under his feet. This is so that Father God will be everything in everyone!

If there is no resurrection, what do these people think they’re doing when they are baptized for the dead? If the dead aren’t raised, why be baptized for them? And why would we be risking our lives every day?

My brothers and sisters, I continually face death. This is as sure as my boasting of you and our co-union together in the life of our Lord Jesus Christ, who gives me confidence to share my experiences with you. Tell me, why did I fight “wild beasts” in Ephesus if my hope is in this life only? What was the point of that? If the dead do not rise, then

Let’s party all night, for tomorrow we die!

So stop fooling yourselves! Evil companions will corrupt good morals and character. Come back to your right senses and awaken to what is right. Repent from your sinful ways. For some have no knowledge of God’s wonderful love. You should be ashamed that you make me write this way to you!

I can almost hear someone saying, “How can the dead come back to life? And what kind of body will they have when they are resurrected?” Foolish man! Don’t you know that what you sow in the ground doesn’t germinate unless it dies? And what you sow is not the body that will come into being, but the bare seed. And it’s hard to tell whether it’s wheat or some other seed. But when it dies, God gives it a new form, a body to fulfill his purpose, and he sees to it that each seed gets a new body of its own and becomes the plant he designed it to be.

All flesh is not identical. Animals have one flesh and human beings another. Birds have their distinct flesh and fish another. In the same way there are earthly bodies and heavenly bodies. There is a splendor of the celestial body and a different one for the earthly. There is the radiance of the sun and differing radiance for the moon and for the stars. Even the stars differ in their shining. And that’s how it will be with the resurrection of the dead.

The body is “sown” in decay, but will be raised in immortality. It is “sown” in humiliation, but will be raised in glorification. It is “sown” in weakness but will be raised in power. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body. For it is written:

The first man, Adam, became a living soul.

The last Adam became the life-giving Spirit. However, the spiritual didn’t come first. The natural precedes the spiritual. The first man was from the dust of the earth; the second Man is Yahweh, from the realm of heaven. The first one, made from dust, has a race of people just like him, who are also made from dust. The One sent from heaven has a race of heavenly people who are just like him. Once we carried the likeness of the man of dust, but now let us carry the likeness of the man of heaven.

Now, I tell you this, my brothers and sisters, flesh and blood are not able to inherit God’s kingdom realm, and neither will that which is decaying be able to inherit what is incorruptible.

Listen, and I will tell you a divine mystery: not all of us will die, but we will all be transformed. It will happen in an instant—in the twinkling of his eye. For when the last trumpet is sounded, the dead will come back to life. We will be indestructible and we will be transformed. For we will discard our mortal “clothes” and slip into a body that is imperishable. What is mortal now will be exchanged for immortality. And when that which is mortal puts on immortality, and what now decays is exchanged for what will never decay, then the Scripture will be fulfilled that says:

Death is swallowed up by a triumphant victory!

So death, tell me, where is your victory?

Tell me death, where is your sting?

It is sin that gives death its sting and the law that gives sin its power. But we thank God for giving us the victory as conquerors through our Lord Jesus, the Anointed One. So now, beloved ones, stand firm, stable, and enduring. Live your lives with an unshakable confidence. We know that we prosper and excel in every season by serving the Lord, because we are assured that our union with the Lord makes our labor productive with fruit that endures.

The Letter of 1st Corinthians, Chapter 15 (The Passion Translation)

Today’s paired chapter of the Testaments is the 50th chapter of the book (scroll) of Isaiah that points to the True illumination of the Son as Messiah:

Eternal One: Where is the document of My divorce from your mother, Israel?

And to whom did I turn you over when I could no longer pay?

No, it was you who amassed debt—a debt of constant wrongdoing—

And that’s why your mother was sent away.

Why is it that when I came to visit, no one was there to greet Me;

and when I called out for you, no one answered?

Do you think My reach insufficient, My power too limited to rescue you?

I need only to speak the words and entire oceans will evaporate;

rivers will become deserts, leaving fish to stink and die for lack of water.

I can dress the heavens with blackness

and trade its velvet skies for the scratchy clothes of mourning.

The Lord, the Eternal, equipped me for this job—

with skilled speech, a smooth tongue for instruction.

I can find the words that comfort and soothe the downtrodden, tired, and despairing.

And I know when to use them.

Each morning, it is God who wakes me and tells me what I should do,

what I should say.

The Lord, the Eternal, has helped me to listen,

and I do as He says. I have not been rebellious or run away from God’s work.

But it’s been hard. I offered My back to those who whipped me,

my cheeks to those who pulled out my beard;

I did not turn away from humiliation and spitting.

Because the Lord, the Eternal, helps me I will not be disgraced;

so, I set my face like a rock, confident that I will not be ashamed.

My hero who sets things right is near.

Who would dare to challenge me?

Let’s stand and debate this head-to-head!

Who would dare to accuse me? Let him come near.

See here, the Lord, the Eternal, helps me—who could possibly win against me?

All my accusers will wear out like a ratty old moth-eaten shirt.

So, you who are listening, do you acknowledge the Eternal One as God?

And do you take seriously what the servant of God has to say?

If you are enveloped in darkness, with no light to see,

take confidence in the name of the Eternal One; rely on your God.

Ah, but if you’ve tried to go it alone,

the light by which you go is your own consuming fire,

And the torches you light will be your undoing.

Eternal One: By My hand you will go down in torment.

The Book (Scroll) of Isaiah, Chapter 50 (The Voice)

to be accompanied by this note from The Voice translation:

The prophet speaks, but his words are those of the Servant of God. The Servant is in tune with God, the Master Teacher. He teaches as he has been taught, and—for the first time it seems—He understands that suffering is an integral part of the work God has for him. The reality for God’s Servant and any who follow him is this: to be close with God means to be at odds with people.

A link to my personal reading of the Scriptures for Wednesday, july 28 of 2021 with a paired chapter from each Testament of the Bible along with Today’s Proverbs and Psalms

A post by John Parsons that looks at the eternal here, & now:

From our Torah portion this week (Eikev) we read: "And now, Israel, what does the LORD your God ask of you..?” (Deut. 10:12). This is the unending question for the heart of faith: it is always here and it is always “now.” The midrash says that the word “and now” (וְעַתָּה) implies the “what” of repentance (תְּשׁוּבָה), turning to God in this hour, regardless of whatever sins you have committed in your past. True repentance turns you away from your sin to become present before God, wherever you might be... [Hebrew for Christians]

7.27.21 • Facebook

and another about clinging to faith in a world that is not our True Home:

The only way out of the painful ambiguity of life is to hear a message from the higher world, the Heavenly Voice, that brings hope to our aching and troubled hearts: "Faith comes by hearing the word of Messiah - ῥῆμα Χριστοῦ" (Rom. 10:17). And yet what is the meaning of this message if it is not that all shall be made well by heaven's hand? There is hope, there is hope, and all your fears will one day be cast into outer darkness, swallowed up by God's unending comfort... "Go into all the world and make students (תַּלְמִידִים) of all nations" (Matt 28:19), and that means sharing the hope that what makes us sick - our depravity and despair - has been healed by Yeshua, and that we escape the gravity of our own fallenness if we accept his invitation to receive life in him. "For you will light my lamp; the LORD my God will outshine my darkness" (Psalm 18:28).

Exercising faith means actively listening to the Eternal Voice, the Word of the LORD that calls out in love in search of your heart's trust... To have faith means esteeming God's love for you, that is, understanding that you truly matter to God, and that the Divine Voice calls out your name, too.... Living in faith means consciously accepting that you are accepted by God's love and grace. Trusting God means that you bear ambiguity, heartache, and darkness, yet you still allow hope to enlighten your way.

The Rizhiner Rebbe once said, “Let your light penetrate the darkness until the darkness itself becomes the light and there is no longer a division between the two. As it is written, “And there was evening and there was morning, one day.” Yea, the darkness and the light are both alike unto Thee, O LORD, as it is written: “If I say, "Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light about me be night, even the darkness is not dark to you; the night is bright as the day, for darkness is as light with you" (Psalm 139:11-12).

We walk by faith, not by sight - by hearing the Word of God, heeding what the Spirit of God is saying to the heart (2 Cor. 5:7). For now we "see through a glass darkly," which literally means "in a riddle" (ἐν αἰνίγματι). A riddle is an analogy given through some resemblance to the truth, though quite often the correspondences are puzzling and even obscure. Hence, “seeing through a glass darkly” means perceiving obscurely or imperfectly, looking "through" something else instead of directly apprehending reality. This is contrasted with the "face to face" (פָּנִים אֶל־פָּנִים) vision and clarity given in the world to come, when our knowledge will be clear and distinct, and the truth of God will no longer be hidden. Being "face to face" with reality means being free of the riddles, the analogies, the semblances, etc., which cause us to languish in uncertainty... Now we know in part, but then shall we know in whole.

Despite the obscurity of life in this temporary age, we are encouraged not to lose heart, since though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being raised into newness (ἀνακαινόω) day by day (2 Cor. 4:16). “For our light and transient troubles are achieving for us an everlasting glory whose weight is beyond description, because we are not looking at what can be seen but at what cannot be seen. For what can be seen is temporary, but what cannot be seen is eternal" (2 Cor. 4:17).

Therefore walk “by faith” as if the invisible is indeed visible. Stay strong and keep hope, for it is through hope that we are saved (Rom. 8:24). Faith is the conviction (ἔλεγχος) of things unseen (Heb. 11:1). Do not be seduced by mere appearances; do not allow yourself to be bewitched into thinking that this world could ever be your home. No, we are strangers and pilgrims here; we are on the journey to the reach "the City of Living God, to heavenly Jerusalem, to the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven" (Heb. 12:22-23). Therefore do not lose heart. Stay focused and keep to the narrow path. Set your affections on things above since your real life is “hidden with God” (Col. 3:1-4). Do not yield to the temptation of despair. Look beyond the "giants of the land" and reckon them as already fallen. Keep pressing on. Chazak, chazak, ve-nit chazek - "Be strong, be strong, and let us be strengthened!" Fight the good fight of the faith. May the LORD our God help you take hold of the eternal life to which you were called (1 Tim. 6:12). Amen. [Hebrew for Christians]

7.28.21 • Facebook

Today’s message (Days of Praise) from the Institute for Creation Research

July 28, 2021

Stunted Growth in Carnal Christians

“And I, brethren, could not speak unto you as unto spiritual, but as unto carnal, even as unto babes in Christ. I have fed you with milk, and not with meat: for hitherto ye were not able to bear it, neither yet now are ye able.” (1 Corinthians 3:1-2)

The apostle Paul here makes a clear distinction between “spiritual” Christians, controlled and led by the Holy Spirit, and “carnal” Christians, still controlled by the desires of the flesh. A carnal Christian is a baby Christian. Baby Christians are a cause of great rejoicing when they are newborn believers, just like baby people. But if they remain babies indefinitely, they become an annoyance to hear and a tragedy to behold.

Each born-again believer needs urgently to “grow in grace, and in the knowledge of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ” (2 Peter 3:18). That spiritual growth comes only through study of the Word, accompanied by belief and obedience. First there must be “the sincere [or ‘logical’] milk of the word” (1 Peter 2:2), but that is good only for the first stages of growth. “For every one that useth milk is unskillful in the word of righteousness: for he is a babe. But strong meat belongeth to them that are of full age, even those who by reason of use have their senses exercised to discern both good and evil” (Hebrews 5:13-14). Scripture encourages us to grow to maturity and then to continue growing.

Carnal Christians are not necessarily pseudo-Christians, although they should examine themselves to determine whether their profession of faith in Christ is genuine (2 Corinthians 13:5), but they should not be content to remain spiritual babes. Every Christian should be able to say with the prophet Jeremiah: “Thy words were found, and I did eat them; and thy word was unto me the joy and rejoicing of mine heart: for I am called by thy name, O LORD God of hosts” (Jeremiah 15:16). HMM

0 notes

Text

Dear Frances,

Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted (1892) centres on the eponymous heroine, Iola Leroy, the daughter of a white slave owner and one of his slaves. When the novel opens, we are at some point during the American Civil War, and a group of slaves meet in secret to discuss the Union army’s progress. Forbidden to congregate, they hold clandestine prayer meetings in the woods. They are talking in code about the war, so as to hide their knowledge from their white owners. Most of them desert their owners and join the Union army, and one of them informs the Union commander of a young woman who is being held as slave in their vicinity. Her name is Iola Leroy, and they decide to rescue her.

The story then jumps back to the years prior to the war, and we follow Iola’s story. Her father, Eugene Leroy, was a wealthy slaveowner who had survived a serious illness through the care of one of his slaves, Marie, who was one-quarter black. He fell in love with her, set Marie free, sent her to a northern school, then married her and had three white children.

Eugene decides to raise Iola, Harry, and Gracie as white, to protect them from prejudice. They were educated in the North and their black ancestry was hidden from them. While at school, Iola even professes a pro-slavery stance. However, when Eugene suddenly dies of yellow fever, his cousin, Alfred Lorraine, decides to make use of legal loopholes to overtake Leroy’s property. Lorraine goes to court to declare Marie’s manumission illegal and her marriage is then annulled. She and her three children revert to slavery and are separated and sold away by Lorraine, who becomes the heir of Eugene’s fortune.

The plot shifts back to the war, when Iola has been rescued from slavery and becomes a nurse in a military hospital. She then receives a marriage proposal from a white medical doctor, Dr. Gresham, who initially professes to be against miscegenation. Upon knowing about Iola’s black ancestry, he asks her to hide it from others and to pass as white. The novel explores her struggle with the question on whether or not she should pass as white and hide her ancestry, so as to make her life easier and take advantage of opportunities for assimilation into white society.

This is a topic that would be explored many times later in literature, such as in Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral by Jessie Redmon Fauset (1928) and Passing by Nella Larsen (1929), and you take a clear stance on it: embracing black identity is a more fulfilling experience for the characters, even if it means that they will have to confront racism to find a job or a house. Further, you make clear that, by asking Iola to ‘pass as white’, Gresham is not only exercising a (not so) subtle form of oppression, but also romanticizing her past as a slave as well as fashioning his role as some kind of ‘white saviour’.

You explore not only the personal but also the political implications of ‘passing’, and, such as in Harriet Wilson’s Our Nig, or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black (1859), you also dismantle the conflation of skin colour, social class, civil rights, and morality, as well as criticize the racism of northern white Americans who were used to think of themselves as ‘more enlightened’ as their southern counterparts.

As Iola sets out to find her mother and bring her family together, she strives to improve the conditions of black people. Caught in the intersection of racial and gender oppression, she struggles to assert her professional independence as a woman during the post-war Reconstruction period.

Such as in Geraldine Jewsbury’s The Half-Sisters (1848), you explore the idea that the fact that a woman has a career does not endanger her womanhood, but rather enhances her roles as wife and mother and contributes to a better family life, as a source of self-respect. Further, you seem to equate enforced domesticity with moral corruption. “”Uncle Robert,” said Iola, after she had been North several weeks, “I have a theory that every woman ought to know how to earn her own living. (…) I think that every woman should have some skill or art which would insure her at least a comfortable support. I believe there would be less unhappy marriages if labor were more honored among women.””

Through conversations between the characters, you incorporate discussions (and speeches) on religion, racism, the rise of violence against black people, temperance (the discussion on the damaging effects of alcohol, as part of a larger discussion on male violence against women), women’s rights, assimilation, education, moral progress, and the movement for equal rights for black people. “”Slavery,” said Mrs. Leroy, “is dead, but the spirit which animated it still lives; and I think that a reckless disregard for human life is more the outgrowth of slavery than any actual hatred of the negro. “The problem of the nation,” continued Dr. Gresham, “is not what men will do with the negro, but what will they do with the reckless, lawless white men who murder, lynch and burn their fellow-citizens”.”

The novel incorporates genres such as slave narrative, sentimental novel, historical fiction, social protest, and the coming of age narrative, as well as political and social commentary. I particularly liked the use flashbacks and dialect throughout the novel, and the fact that its main political ideas are incorporated through conversations conveyed in dialect, providing not only a black perspective but a black voice. You seem to link the topics of how slavery fractures the family unit and how racism fractures one’s notion of identity – particularly racial identity, as in the case of ‘passing’. “I ain’t got nothing ‘gainst my ole Miss, except she sold my mother from me. And a boy ain’t nothin’ without his mother. I forgive her, but I never forget her, and never expect to. But if she were the best woman on earth I would rather have my freedom than belong to her.”

The subtitle of the novel – “(…) or, Shadows Uplifted” – seems to suggest racial and civil empowerment, as well as the release from the shadows of war and slavery. “The shadows have been lifted from all their lives; and peace, like bright dew, has descended upon their paths. Blessed themselves, their lives are a blessing to others”. It also hints at religious enlightenment and salvation, at the uplifting of the afflicted, as you explore the moral contradiction of slavery and Christianity: “But, Mr. Bascom,” Harry said, “I do not understand this. It says my mother and father were legally married. How could her marriage be set aside and her children robbed of their inheritance? This is not a heathen country. I hardly think barbarians would have done any worse; yet this is called a Christian country.” “Christian in name,” answered the principal”. Finally, the subtitle also points to the lifting of the “veil of concealment” represented by the act of ‘passing’, and to a defence of the assertion of black heritage and black identity.

Iola Leroy resists the literary convention of the “tragic mulatta” and its conflation with the “fallen woman” trope to evoke sympathy in a white reading audience: your book does not portray miscegenation as a catalyst to a female character’s demise, and you refuse to use Iola to placate white readers. She is her own woman.

Iola will eventually choose her black heritage, and you frame this choice as one of truth and moral fortitude over (white) appearance and shallowness. Some have read this framing as a conservative choice in its disavowal of passing (which they read as a disavowal of miscegenation and equality); to me, however, particularly in the context in which you were writing, your framing reveals ‘passing’ as a subtle form of oppression and the need of assimilation into white society as a conservative stance.

The highlight of the book for me is the fact that it encompasses a variety of black experience, from slaves to freed blacks to mixed-race characters to black intellectuals and the black upper class: it is a jam session of black voices, with an underlying, radical beat of resistance and hope.

Yours truly,

J.

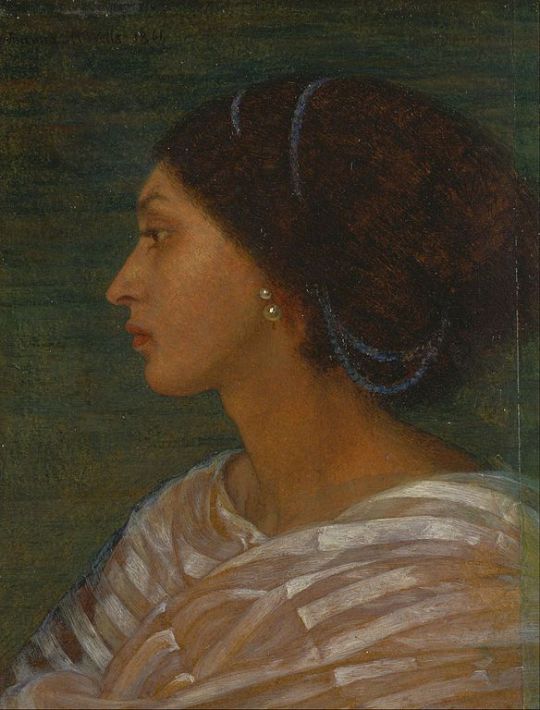

‘Head of Mrs Eaton (Fanny Eaton)’ by Joanna Boyce Wells (1861)

“Miss Leroy, out of the race must come its own thinkers and writers. Authors belonging to the white race have written good racial books, for which I am deeply grateful, but it seems to be almost impossible for a white man to put himself completely in our place. No man can feel the iron which enters another man’s soul.” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

*

Now, Captain, that’s the kind of religion that I want. Not that kind which could ride to church on Sundays, and talk so solemn with the minister about heaven and good things, then come home and light down on the servants like a thousand of bricks. I have no use for it. I don’t believe in it. I never did and I never will. If any man wants to save my soul he ain’t got to beat my body. That ain’t the kind of religion I’m looking for. I ain’t got a bit of use for it. Now, Captain, ain’t I right?” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

*

“Miss Iola, I think that you brood too much over the condition of our people.” “Perhaps I do,” she replied, “but they never burn a man in the South that they do not kindle a fire around my soul.” – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

*

One day a gentleman came to the school and wished to address the children. Iola suspended the regular order of the school, and the gentleman essayed to talk to them on the achievements of the white race, such as building steamboats and carrying on business. Finally, he asked how they did it? “They’ve got money,” chorused the children. “But how did they get it?” “They took it from us,” chimed the youngsters. Iola smiled, and the gentleman was nonplussed; but he could not deny that one of the powers of knowledge is the power of the strong to oppress the weak. – Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Iola Leroy: Shadows Uplifted

About the book

Broadview Press, 2018, 352 p. Goodreads

Penguin Classics, 2010, 256 p. Goodreads

Beacon Press, 1999, 320 p. Goodreads

First published in 1892

My rating: 3,5 stars

Projects: The Classics Club; A Century of Books; Back to the Classics, hosted by Karen

My thoughts on Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted (1892), by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper #readwoman #readsoullit #zoracanon Dear Frances, Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted (1892) centres on the eponymous heroine, Iola Leroy, the daughter of a white slave owner and one of his slaves.

0 notes

Text

The Inexhaustible Poetry of Lawrence Joseph

The Inexhaustible Poetry of Lawrence Joseph

By Anthony Domestico

March 17, 2020

…So many selves—

the one who detects the sound of a voice,

that voice—the voice that compounds

his voice—that self obedient to that fate,

increased, enlarged, transparent, changing.

—from “Woodward Avenue”

All poets have many selves; all non-poets do, too. But the selves that constitute the poet Lawrence Joseph are particularly numerous and peculiarly unlikely in their combinations.

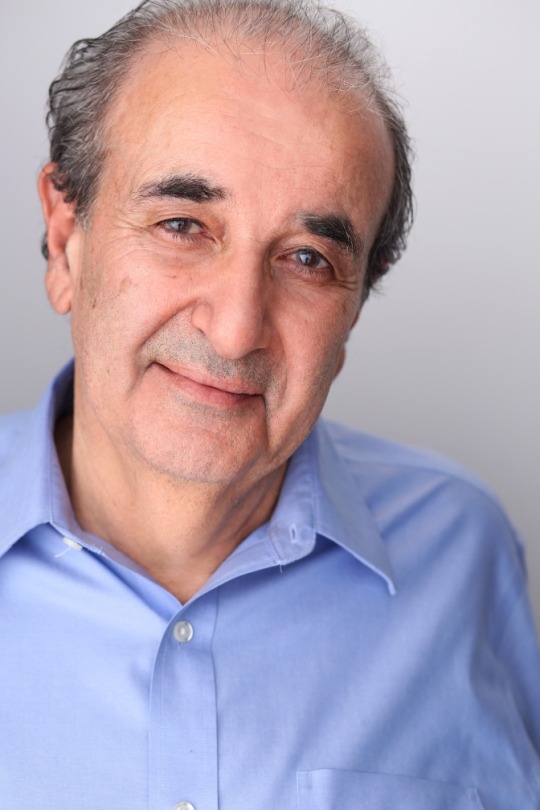

Lawrence Joseph is a Detroit poet. (For decades, his father and uncle owned and ran a grocery store, which they inherited from their father, on the corner of John R. and Hendrie.) He’s a New York City poet. (He has lived in Battery Park, a block from Ground Zero, for twenty-six years. After the September 11 attacks, he couldn’t locate his wife, the painter Nancy Van Goethem, for more than twenty-four hours.) He’s an Arab-American poet. (His grandparents were among the first wave of immigrants from Lebanon and Syria to Detroit in the 1910s.) He’s a leftist poet. (“Eyes fixed on mediated screens,” he writes in “Visions of Labor,” “in semiotic / labor flow: how many generations between / the age of slavery of these States and ours?”) He’s a Catholic poet. (Or, as he prefers, a poet who is Catholic—one who has been, as he announces in the very first poem in his very first book, “appointed the poet of heaven.”) Perhaps most interestingly, he’s a lawyer-poet.

Lawrence Joseph (Courtesy of FSG)

This last compound identity distinguishes Joseph from almost every other great American poet (almost: there is also Wallace Stevens). For nearly fifty years, Joseph has led two distinct professional lives—one legal, one poetic. Since 1987, he has been on the faculty at St. John’s University School of Law in Queens, where he serves as Tinnelly Professor of Law and teaches courses on torts and compensation, labor and employment law, and law and interpretation, among other subjects. Before coming to St. John’s, he taught at the University of Detroit and clerked for Justice G. Mennen Williams of the Michigan Supreme Court. He has given papers at (and been the subject of) legal conferences, and he has published essays with decidedly unpoetic titles: “The Causation Issue in Workers’ Compensation Mental Disability Cases: An Analysis, Solutions, and a Perspective” in the Vanderbilt Law Review, for example. David Skeel, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, writes that “Joseph has explored the increasing, though awkward and at times unreflective, recognition of subjectivity in Supreme Court opinions.” As Skeel told me on the phone, “Larry’s perspectival opinion has won the day.” He’s an important figure in the growing field of law and literature.

Yet since 1983, Joseph has also been publishing books of poetry that, in their formal control and moral witness, match anything published in the past half century. In March, Farrar, Straus and Giroux published A Certain Clarity: Selected Poems, which gathers together poems from five previous collections. The range of Joseph’s writing, in this book and throughout his career, is awesome. His language is streetwise and philosophical; his forms are by turn intensely compressed and exhilaratingly expansive.

Joseph’s 1983 debut, Shouting at No One, included Detroit geographies (Van Dyke Avenue, “UAW Local 89,” “the Church of I AM”) rarely encountered in American poetry. These early poems have short lines and long stanzas. They’re concrete, imagistic, and condensed, displaying, as the poet Toi Derricotte told me, a real “knowledge of the complexities of Detroit.” (Derricotte is herself a Detroit native who went to school near the Joseph family store.) Though Shouting at No One is primarily a Detroit book, it was published two years after Joseph had moved to New York City. With each subsequent collection, Joseph has expanded and continued to intensify his vision. The first poem in Curriculum Vitae (1988) takes place “in New York City, / during the nineteen eighties,” and the collection, though it often returns to Detroit, looks increasingly to Manhattan’s flow of capital—and to those left outside the flow, abandoned by the economy and the city: “I watch // a workman standing on the pier, looking / across at the coast turning toward // the Narrows, his hands bandaged, / victim of a work accident // who doesn’t know what to think / or what to do and hasn’t enough // to buy himself something to settle his mind.”

In his next book, Before Our Eyes (1993), Joseph includes both his first poems about America’s wars with Iraq, and an increased sensuousness. Here are that book’s first, painterly lines: “The sky almost transparent, saturated // manganese blue. Windy and cold. / A yellow line beside a black line, / the chimney on the roof a yellow line / behind the mountain ash on Horatio.” In 2005’s Into It, the language opens up even more, accommodating terms from the realms of law and political economy, especially in poems dealing with the September 11 attacks and the second Iraq War. Some of the poems get prosier; almost all find beauty “in the midst of delirium.” 2017’s So Where Are We? takes on America’s endless wars, both foreign (Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria) and domestic (the financial crisis, both its cause and effects).

Joseph’s poems map American violence in its diverse forms. They examine the physical violence of American empire: “Behind / the global imperia is the interrogation cell.” They chart the moral violence of the American economy: “Capital capitalizes, / assimilates, makes / its own substance.” And they note the connections between the two: “the blood money in the dummy account / in an offshore bank, washed clean, free to be / transferred into a hedge fund or foreign / brokerage account, at least half a trillion / ending up in the United States, with more to come.” A Certain Clarity measures and pushes back against the pressures of our time. Joseph has lived in New York City since 1981, for years by the Brooklyn Bridge and now for years by Wall Street. He has lived, in other words, at the center of American culture and capital, and his poems, as they stroll from Fulton Street to Pearl Street to Peck Slip, register the workings of American power in all its forms.

Yet Joseph is also an aesthete—“I’m not a pseudo-aesthete,” he told me, laughing: “I’m a full-blown aesthete”—as the righteous anger of his prophetic vision is matched by the sumptuousness of his language. Each of his poems finds its meaning in and through form: the various shapes his stanzas and sentences take, their shifts in cadence, tense, and register. “I believe that poets have to—perhaps above all have to—love sound,” Joseph has said, and his love of sound and color comes across in every poem. He has spent most of his life living alongside water—the Detroit River, the East River, and the Hudson—and A Certain Clarity contains one riverine observation after another. His poems often describe the changing light over water: “Pink above the Hudson / against the shadows lingering still, / the sky above an even blue and changing / to a pale gray and rose”; “This light is famous, / its sad, secret violet, and, this evening, / West and East rivers turned into one.”

When I asked Joseph about how his two lives—the life of the lawyer and the life of the poet—fit together, he quoted Wallace Stevens. “One is not a lawyer one minute and a poet the next,” Joseph said, quoting a 1942 letter Stevens wrote to Harvey Breit. “I don’t have a separate mind for legal work and another for writing poetry. I do each with my whole mind, just as everything that each of us does we do with our whole minds.”

The poet is concerned with many things: perception and meditation, the social and the soul. But the poet is concerned above all else with language: pressurizing language, perfecting and condensing and enlarging it. The poet is, to quote Marianne Moore on Stevens, “a linguist creating several languages within a single language.” So is the lawyer. James Boyd White, a legal scholar often cited as the founder of the law and literature movement of which Joseph is such an important part, has argued that judicial language should strive for “many-voicedness.” That’s a good description of the polyvocality of Joseph’s verse, which channels Gramsci and Melville, the union hall and the lecture hall, lyrical rhapsodizing and rage-filled cursing, often in the space of a single stanza.

“Reading, teaching, tens of thousands of cases, writing and teaching sets of facts, which are stories, narratives, rooted in every dimension of social reality has greatly expanded my range of language,” Joseph told me. It’s also attuned him to power and its perversions: “Being a lawyer has intensified my moral awareness of evil.” What better training for the kind of poet Joseph has always been: looking outward to the world and inward to the soul, finding a language for both.

***

‘I’ve lived in the language and theology of Catholicism since I was a child,’ Joseph told me.

… Baptized

in the one true church, I too

was weaned on Saint Augustine.

—from “Curriculum Vitae”

“All poems,” Joseph told me, “come out of experience,” and his poems often point back to his own biography in refracted, transfigured form. “The ‘I’ in a poem can never be identified with the poet’s empirical self,” Joseph said, quoting the critic Michael Hamburger. “The ‘I’ in a poem conveys a great many different gestures, of a great many different orders.” This is true for all poets, and it’s certainly true for Joseph. But it’s also true that a great many of Joseph’s poetic gestures have arisen from his interesting and complicated life.

Joseph was born on March 10, 1948 in Providence Hospital, a Catholic hospital located on West Grand Boulevard in Detroit. His parents were also born in Detroit; so were his many aunts and uncles (he counts twenty-six first cousins); and so was his wife, Nancy. Both his parents attended Catholic schools—his father on Detroit’s West Side, his mother on the city’s East Side. So did Nancy. “I’ve lived in the language and theology of Catholicism since I was a child,” he told me.

Detroit’s history in the twentieth century is the history of many things: of big industry and mass production; of labor and capital; of Motown and modern jazz; of professional sports (it’s one of the few cities that has had franchises in all four major sports) and political upheaval (the 1967 riots; the city’s recent bankruptcy). All of these have touched upon Joseph’s life in one way or another. He’s worked summer jobs in factories. He’s listened to, and written on, Aretha Franklin and Smokey Robinson. Knowing I’m a Red Sox fan, he told me that he will never forget the heartbreak of the Tigers losing the pennant to Boston on the final day of the 1967 season.

Detroit’s twentieth-century history is also the history of Arab Americans. Immigrants from Lebanon and Syria started settling in the Detroit area in small numbers in the 1870s. By 1951, three years after Joseph’s birth, about 50,000 people of Lebanese and Syrian descent lived in the city. Joseph’s maternal grandfather was born in Damascus and baptized into the Melkite rite. His paternal grandparents were born in Lebanon, as was his maternal grandmother, all baptized in the Maronite rite.

In a poem from Curriculum Vitae (1988), Joseph metaphorically crystallizes his Arab American Detroit: “Lebanon is everywhere / in the house: in the kitchen / of steaming pots, legs of lamb / in the oven, plates of kousa, / hushwee rolled in cabbage, / dishes of olives, tomatoes, onions, / roasted chicken, and sweets.” Inside the house, there’s warmth and love. Outside the house, the speaker witnesses the effects of industrial capitalism and racialized violence: “‘Sand nigger,’ I’m called, / and the name fits: I am / the light-skinned nigger / with black eyes and the look / difficult to figure—a look / of indifference, a look to kill.”

Joseph was baptized at St. Maron’s, a Maronite church in Detroit, as were his two brothers and one sister. “I’ve never not believed in God,” he told me. He remembers attending daily Mass from the first through eighth grades, “following along, from fourth grade on, with the St. Joseph Daily Missal, which included the Ordinary of the Mass in both Latin and English, and also hundreds of pages of the Liturgical Calendar and a ‘Treasury of Litanies and Prayers.’” He was confirmed at the age of ten and began serving Mass in the sixth grade. “I memorized the Baltimore Catechism,” he writes in “Curriculum Vitae,” “I collected holy cards, prayed / to a litany of saints to intercede / on behalf of my father who slept / through the sermon at seven o’clock Mass.” (From 1960 on, Joseph’s father worked as a meat cutter at A & P, in addition to helping his brother man the store, often working twelve hours a day.)

When he was almost four, Joseph’s family moved to Royal Oak, near Woodward Avenue and Twelve Mile Road, four miles north of Detroit’s 8 Mile Road boundary. They were parishioners at the Shrine of the Little Flower, located a few blocks from where they lived. Built in the 1930s, the Shrine is known in part for its Art Deco style but mainly for its patriarch, Father Charles Coughlin—the Jew-baiting talk radio priest who is the forerunner of much that is most toxic in our own political moment. Coughlin started off as a New Deal populist, preaching Leo XIII and Pius XI’s social encyclicals, before turning to anti-Semitism and flirting with outright fascism in the late 1930s and early ’40s. Joseph described Coughlin to me as “a progenitor of right-wing Catholicism that espoused a fascistic Catholic Corporate State.” Joseph has been describing and denouncing this strand of God-talk for years: “Thugs, / thugs are what they are, false-voiced God-talkers and power freaks / who think not at all about what they bring down.” Joseph’s family were Democrats. He delivered Detroit’s morning paper, the liberal Detroit Free Press, from the age of eleven to eighteen. (When Joseph met Nancy, she was working as an artist at the Free Press.)

His father’s grocery store, called Joseph’s Market, was in a rough neighborhood. Joseph’s uncle had his throat slashed at the store in the 1960s. When Joseph was twelve, his father, Joseph Joseph, taught him how to recognize the signs of heroin addiction. In “By the Way,” the poet remembers his father shot by a heroin addict in 1970: “The bullet missed / the heart and the spinal cord, / miraculously, the doctor said. / Everything eventually would be all right. / The event went uncelebrated among hundreds / of felonies in that city that day.” From an early age, Joseph walked and drove the streets of Detroit, looking and listening and jotting down notes. In high school he caddied, and in college he washed dishes and delivered pizzas and, during summers, worked in factories. Every Detroit street, he told me, contains some sensuous memory. The city is for him a metaphor and a body—a geography that is physical, spiritual, imaginative, and economic. “In Joseph’s Market on the corner of John R and Hendrie,” he writes in an early poem, “there I am again: always, everywhere, // apron on, alone behind the cash register, the grocer’s son / angry, ashamed, and proud as the poor with whom he deals.”

***

Joseph isn’t sentimental about our long-since departed manufacturing economy. He knows that capital has always thrived by exploiting labor.

Two things, the two things that are interesting

are history and grammar.

In among the foundations of the intelligence

the chemistries of words.

—from “When One Is Feeling One’s Way”

After attending the Jesuit University of Detroit High School, where he studied Latin and Greek, Joseph enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1966, where he took part in the antiwar movement and, in the winter of 1967, wrote his first poems. That July, while he was working at General Motors Truck & Coach in Pontiac as a dry sander, the Detroit riots occurred. Looters hit Joseph’s Market: “Take the canned peaches,” Joseph imagines his father saying as he drives away from the store. “Take the greens, the turnips, / drink the damn whiskey / spilled on the floor.”

At Michigan, Joseph studied with the poet Donald Hall, writing a paper on Vorticism (there’s the modernist influence) and an honor’s thesis on “Swinburne’s Poetic Technique” (there’s the interest in aestheticism). He won a fellowship and studied English at Cambridge University in England from 1970 to 1972, obsessively reading Albert Camus, Simone Weil, Eugenio Montale, John Berryman, and many others, translating St. Augustine’s De Trinitate, and writing poetry all the time.

Joseph told me that he realized in 1966, while an undergraduate, that he would write poetry for the rest of his life. He realized in 1972, while at Cambridge, that he would “have a professional life as a lawyer, and not as a professor of literature or creative writing.” This decision was no doubt informed by his background. He was “raised to be a lawyer,” he says: his uncle John founded the first Arab-American law partnership in Detroit, and Joseph was a skilled debater for all four years of high school. “I wanted the freedom to write what I wanted,” he told me. “I didn’t want what I wrote, and the pace that I needed to write it, economically dependent upon my profession.” So he enrolled at the University of Michigan Law School in 1973 and began a successful legal career. In that same year, he met Nancy. In 1975, Joseph moved to Detroit to live with her at the Alden Park—a Tudor apartment complex on Detroit’s East Side, on the Detroit River, next to the United Auto Workers’ Solidarity House, four or five miles from downtown and near where his maternal grandparents lived.

As one who has never received an MFA or taught in an MFA program, Joseph is a relative rarity in the poetry world. “I was always attracted to the margins,” he told me. He counts many poets as friends, but poetry isn’t his only interest. Sometimes, Joseph’s life outside of poetry can be felt in his command and poetic repurposing of legal language: “After I applied Substance and Procedure / and Statements of Facts,” he writes in “Curriculum Vitae,” “my head was heavy, was earth.” Here is a sestet from “On Peripheries of the Imperium”:

Conflated, the financial vectors, opaque

cyber-surveillance, supranational cartels,

in the corporate state’s political-economic singularity

the greatest number of children

in United States history are, now, incarcerated,

having been sentenced by law.

Due to his legal training, Joseph knows the language of power. He sees its victims and its victimizers; he sees its intended and unintended effects. As the legal scholar Frank Pasquale writes in a recent essay, Joseph’s poems “reveal patterns of power and meaning in the world by exploring the ramifications of critical terms.”

The law has influenced the diction of Joseph’s poems. It has also influenced his formal decisions. “Law’s aesthetic-formal-rhetorical dimensions,” he wrote to me, “asking questions, cross examination, argument, have greatly broadened the transitional rhetoric in my poetry.” Anyone who has read Joseph will know how often his poems shift: cutting between temporalities and locations; juxtaposing different languages that come from different social spaces. He’s also an interrogative poet. One recent poem memorably, horribly begins, “Technically speaking, / is a head blown to pieces by a smart bomb a beheading?”

Reading A Certain Clarity in its entirety, an argument about American political economy emerges. We have moved from “mass assembly based on systems of specialized / machines operating within organizational domains” to the flim-flam of leveraged buy-outs and “techno-capital.” Joseph isn’t sentimental about our long-since departed manufacturing economy. He knows that capital has always thrived by exploiting labor, polluting workers’ bodies and poisoning our environment. (For decades he’s been writing about what economists call “negative externalities” and what Pope Francis describes as the plundering of creation for profit.) But he’s horrified by the speed and unreality of our current finance economy—unreal except in its devastating effects upon those not in power: “Narco-capital techno-compressed, / gone viral, spread into a state of tectonic tension and freaky / abstractions—it’ll scare the fuck out of you, is what it’ll do, / anthropomorphically scaled down by the ferocity of its own / obsolescence.”

***

You can’t budget a half hour for a phone call with Joseph. You can’t even confidently budget an hour.

Who talks like that? I talk like that.

—from “Who Talks Like That?”