#the summer soldier and sunshine patriot

Text

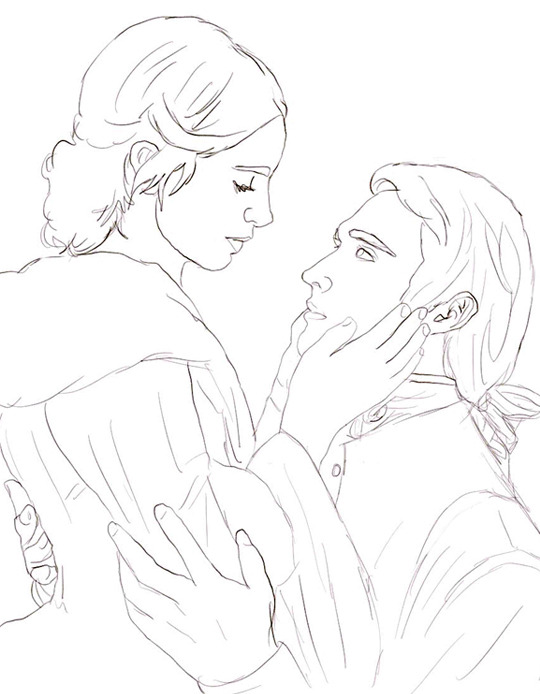

Benjamin & Elizabeth Anniversary Snippet!

Hi, everyone! In honor of today's special SS&SP occasion, I wrote a little snippet from a random (but one of my favorites) early 1778 scene to celebrate Benjamin and Elizabeth and get back into the swing of writing them. This summer is hectic, and I know I have to heavily rework the next chapter, but I wanted to have some fun, so here we are! Thanks for sticking around, and for loving Benliz as much as I do! I hope you enjoy!

“Are you nervous?” Benjamin asked.

He stood beside her, his gaze intensely focused on the general’s quarters, searching through the windows as if he was looking for an invisible threat in the stone house. After spending the past several hours walking in and out of them, the houses faded into one another, blurs of brown, grays, and tans, the monotony occasionally broken by weathered white stucco and green shutters. Melted snow ran down the roofs, darkening the colors, but the windows caught the sunlight. Thank god, it was a beautiful day for her parade through camp.

The last thing the generals need to see is you soaking wet with dirt on your hem, she thought. How impossible would it be for them to take you seriously?

Hamilton knocked on the door. He turned over his shoulder. “Should just be a moment, Miss Walker! He surely must be home.”

“You know I am always a little nervous,” she told Benjamin, but she tried to smile, “it’s always a given, unfortunately.”

But it- it wasn’t a shame with him. It wasn’t a secret sin, tied around her heart with strong ropes. Something her father tried to restrain and keep in the shadows, unspoken and abandoned like every problem besides his Congress and his money and her brother’s behavior. She told him when she was nervous, and he fixed it-- with his voice, his words, a change in his presence. Not always-- no, you can never be that optimistic, Elizabeth- but enough.

Enough to keep her standing here.

“Are you tired, then?”

She laughed, “Tired? I’m accustomed to the schedule here-” she leaned in, whispered, “Benjamin.”

There, the classic head tilt, the sheepiness and shock in his eyes, a loosening of the rope.

“I am simply inquiring after your health-”

“Go ahead,” she pressed.

He briefly glanced at the door, the rest of the group.

“Elizabeth.”

God, it was risky.

But she loved hearing him say her name.

Only for a moment.

She found the straight to lean backward on her heels, running her hands along her skirts, but she laughed again. “I’m nervous, but I am not tired, and I’d like to meet the rest of the generals.”

“Of course,” he nodded, and followed her, transforming himself back into a professional officer. “A pity though.”

Oh, she couldn’t let that go. “Why? Will the general not like me? Surely his men have told him about me-” she held up a hand, “and I know we told them to keep my presence a security, but they like to chatter amongst themselves, and I hear the general is quite the talker-” Her nerves rose, her voice a pitch higher.”

“No,” he said solemnly.

“Then what is it? Oh, Major, tell me-”

She wanted him to tell her, and for a slight second, she wished they were alone. She wished they were alone, and that he could take her in his arms, and tell her gently. Let her down softly, as if he were helping her off her horse, a brush of tenderness, what had kept her stable half of her sleepless nights.

But all she could do was lean towards him, take a small step closer.

“A pity,” he said, his voice slow, “because I would love to do something about your hair.”

“My hair?”

She reached up. Mary had styled it differently today, into a plait, letting it cascade down her back, a delicate mess of curls. She smiled as she pinned the cocked hat into place, “Will the Generals approve, Miss Lizzie?”

But she didn’t care what they thought.

“Do you like it?” She whispered.

“A little too much. I want to rearrange it." Full of unnecessary conviction.

God, she almost rolled down the hill.

“That is not allowed, Major Tallmadge.”

Her mind was suddenly ambushed with the thought, the tantalizing vision of him running his hands through her hair, his fingers brushing against the skin behind her ear, her neck. Her heart raced, damn the nerves.

“Don’t laugh,” she ordered.

“I will not.”

In the distance, Hamilton knocked on the door again. “Damn the big man,” she heard him mutter to the marquis.

“We can compromise,” she said after inhaling a deep breath.

“How so?”

“The ground is a bit unsteady.” She lied.

“Yes,” he agreed.

“You can help.”

“I can.”

She looked down, and saw his hand leave the hilt of his sword, lingering in the air between them. Oh, if only she could take it.

The door opened.

And Benjamin’s hand was on the small of her back.

A quick stroke.

And it was better than any of her fleeting fantasies.

She was doing what she loved, and she wasn’t alone.

“Let’s go meet General Knox.”

Was keeping the secret fun?

She didn’t know, yet.

At least he was allowed to have his hand on her back.

#as you can see#they are TERRIBLE at keeping secrets#like I know I said they are#but it still shocks me#this was fun!!#ahh!!#it's been FOREVER#so pardon my nerves#anYWAYS#benjamin tallmadge#elizabeth walker#ss&sp#the summer soldier and sunshine patriot#turn: washington's spies#turn: washington's spies fic#turn amc fic#turn fic#otp: first thing in the morning#amanda writes (kind of)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.”

- Thomas Paine

23 notes

·

View notes

Quote

These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer

soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink

from the service of his country; but he that stands it now,

deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like

hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with

us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: It is

dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows

how to set a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange

indeed, if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be

highly rated.

Thomas Paine, The American Crisis

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of Trenton

* * * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

December 25, 2023

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

DEC 25, 2023

In the summer heat of July 1776, revolutionaries in 13 of the British colonies in North America celebrated news that the members of the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, had adopted the Declaration of Independence. In July, men had cheered the ideas that “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States,” and that, in contrast to the tradition of hereditary monarchy under which the American colonies had been organized, the representatives of the thirteen united states intended to create a nation based on the idea “that all men are created equal” and that governments were legitimate only if those they governed consented to them.

But then the British responded to the colonists’ fervor with military might. They sent reinforcements to Staten Island and Long Island and by September had forced General George Washington to evacuate his troops from New York City. After a series of punishing skirmishes across Manhattan Island, by November the British had pushed the Americans into New Jersey. They chased the colonials all the way across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania.

By mid-December the future looked bleak for the Continental Army and the revolutionary government it backed. The 5,000 soldiers with Washington who were still able to fight were demoralized from their repeated losses and retreats, and since the Continental Congress had kept enlistments short so they would not risk a standing army, many of the men would be free to leave the army at the end of the year, weakening it even more.

As the British troops had taken over New York City and the Continental soldiers had retreated, many of the newly minted Americans outside the army had come to doubt the whole enterprise of creating a new, independent nation based on the idea that all men were created equal. Then things got worse: as the American soldiers crossed into Pennsylvania, the Continental Congress abandoned Philadelphia on December 12 out of fear of a British invasion, regrouping in Baltimore (which they complained was dirty and expensive).

By December, the fiery passion of July had cooled.

“These are the times that try men’s souls,” read a pamphlet published in Philadelphia on December 19. “The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

The author of The American Crisis was Thomas Paine, whose January 1776 pamphlet Common Sense had solidified the colonists’ irritation at the king’s ministers into a rejection of monarchy itself, a rejection not just of King George III, but of all kings.

Now he urged them to see the experiment through. He explained that he had been with the troops as they retreated across New Jersey and, describing the march for his readers, told them “that both officers and men, though greatly harassed and fatigued, frequently without rest, covering, or provision, the inevitable consequences of a long retreat, bore it with a manly and martial spirit. All their wishes centred in one, which was, that the country would turn out and help them to drive the enemy back.”

For that was the crux of it. Paine had no doubt that patriots would create a new nation, eventually, because the cause of human self-determination was just. But how long it took to establish that new nation would depend on how much effort people put into success. “I call not upon a few, but upon all: not on this state or that state, but on every state: up and help us; lay your shoulders to the wheel; better have too much force than too little, when so great an object is at stake,” Paine wrote. “Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.”

In mid-December, British commander General William Howe had sent most of his soldiers back to New York to spend the winter, leaving garrisons across the river in New Jersey to guard against Washington advancing.

On Christmas night, having heard that the garrison at Trenton was made up of Hessian auxiliaries who were exhausted and unprepared for an attack, Washington crossed back over the icy Delaware River with 2400 soldiers in a winter storm. They marched nine miles to attack the garrison, the underdressed soldiers suffering from the cold and freezing rain. Reaching Trenton, they surprised the outnumbered Hessians, who fought briefly in the streets before they surrendered.

The victory at the Battle of Trenton restored the colonials’ confidence in their cause. Soldiers reenlisted, and in early January they surprised the British at Princeton, New Jersey, driving them back. The British abandoned their posts in central New Jersey, and by March the Continental Congress moved back to Philadelphia. Historians credit the Battles of Trenton and Princeton with saving the Revolutionary cause.

“Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered,” Paine wrote, “yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#American Revolution#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#American history#tyranny#These are the times that try men's souls

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorktown, 1781

Yorktown, 1781

Read here originally written as part of this much longer work.

Now or never

September 20th, 1781.

The British had trapped themselves, at Yorktown. General Cornwallis had barricaded himself in a Virginian swamp, the Marquis de Lafayette had explained. What’s more the French fleet was more than happy to aid in the destruction of their mutual enemy, Great Britain. Still more, a double agent, a black man by the name of James Armistead Lafayette was feeding English intelligence false information. It was now or never, now that Cornwallis had sent for reinforcements and a fleet from New York.

“We must take Cornwallis, lest we lose all morale and the people,” Washington said.

Tallmadge merely nodded, silent but never not observant holding his Dragoon helmet close.

“It is now or never,” Lafayette said.

These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. - Thomas Paine

The trenches

October 11th, 1781.

Several sleepless nights for Major Benjamin Tallmadge as the patriot and allied militias dig trenches surrounding the English enemy. The English put up a fight, of course they do, amidst the darkness sounds of cannons being fired shake the ground and would burst any unaccustomed to war’s eardrums. The smoke from the English muskets fills the air, making it more than a little difficult to breathe, great plumes of white billowing into the air made worse by the southern heat and swampy ground of Virginia and every once in awhile a great booming noise just overhead and something were it less brutal one could half deceive themselves into thinking it a blazing red comet falling to earth.

By morning the trenches are dug, and remarkably, no American casualties, not yet Tallmadge only prayed for the least amount of life taken, and a steady and swift end to this conflict. There are a few casualties on their allies, the French side, but not enough to be noted in any war as substantive. Morale is still high, they need only push Cornwallis til he breaks.

With the right poison, even a snake can take down a lion.

Firestorm

October 15th, 1781.

Across the York River, the sound of a French military drum echoed a steady “da-da-da-dum.” English warships held that side of the river, for the moment. Encroaching in the dead of night the navy of French Admiral Comte de Grasse, set about their cause, the one they were all to pleased to do on General Washington’s insistence.

Raining down cannon fire which soon spread set the vast majority of the English fleet aflame. Tallmadge didn’t see it, not all of it. Truthfully, it was hard to watch, the agony of others, even the enemy, even redcoat lobsters, practically flamed alive. Cornwallis retreated in a small escape vessel but in but a manner of hours, the English fleet at Yorktown and the men who had stood through no fault of their own for their… King and Country were obliterated.

Tallmadge sucked in his breath nervously as recollections of Sarah Livingston passed briefly before his blue eyes. It was necessary, sure, and he wouldn’t run. But… such ungodly suffering, like flames lapping up from Hell, consuming everything in it’s wake.

The cannons, are like a heart beat that rips through you and tears you up. That tears the unlucky limb by limb. Worse than any bullet.

Some talk of Alexander and some of Hercules

Of Hector and Lysander, and such great names as these.

But of all the world's brave heroes, there's none that can compare.

With a tow, row, row, row, row, row, to the British Grenadiers.

Man or a monster

October 16th, 1781.

It had occurred to Benjamin but once before now that he might be wrong, even after all this time, Sarah’s words rang in his ears, ‘I am not ready to die for yours,’ Sarah had said, she had begged his assistance, and he had not returned it, he had killed her. As Comte de Grasse had demolished the English fleet and the man aboard those ships. It must be wrong, surely, or at least, not anything any Good God would approve of, on either side. His name was already tainted, at least to him, it was a wonder anyone could still see Good in him.

Benjamin, son of the right hand in Hebrew, is the chosen son. Or so one in all their wisdom had explained.

Wrong, would this be counted against him or for him, on the day he finally passes? As is most certain and unavoidable for all mankind.

Laying in his cot in his tent Tallmadge managed a prayer. A meek one, but, a prayer nonetheless. Tallmadge would do his duty, finish his task, mount his horse with his spurs and take up his musket and pistols were it so required. But, when this is over and he, at last, can hang up his spurs and his sword– he promises never to lay a hand on a gun or such a fatalistic tool as a sabre ever again. Such destruction and what cost? Surely it is only right for God to play such drawn-out affairs with life and death.

‘But what if perhaps God doesn’t exist?’

But it is surely not Benjamin’s place to question God’s design, faith and friends had kept him alive, however much he wavered and seemed ill at ease. It had been six years fighting George III’s empire, he would surely not break now. Even if it condemned his soul from thereafter.

Even if it made Benjamin no better than the demon or a Lamia the scriptures warn men about.

Redcoats redder

October 17th, 1781.

So the bombardment of the English began in earnest at last. Benjamin was aching for a fight and so it seemed were his colleagues Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens. Washington promised them soon enough – they must break the English defensive in its entirety first. 2,500 Patriots and 4,000 French allies… up against 8,000 English troops. But, as fate or God would have it, 8,000 unguarded, ill of malaria and dysentery and trying to hold a strategic position on land any sensible person would say was unholdable.

Perhaps it was just Cornwallis’s spite for the Americans, the English always seemed to forget the collective power of her colonies, or perhaps more foolish yet, holding out for reinforcements from New York. What it was, didn’t matter. Not when the clock was ticking and in this rare instance, God seemed to favour the patriot side. They’d take the remaining redoubts by storm it is either that or the noose. Liberty or death.

Benjamin had thought on the concept of dying now so many times, it seemed, he now had a sort of disconnect from the entire concept. That was until now. Until he could no longer deny its likelihood. Guns and strategic advantages aside, they were still outnumbered and they were still facing the worlds greatest Empire, if one could call it that. Tallmadge much preferred the concept of putting down a hungry beast, like a Mantacore of Greek legend, or… Echidna the mother of monsters from the same. Surely that was the most apt description for the thing they were fighting. Even bloodsucker or a leech was far too kind.

So, into the belly of the beast they charge, it is, simply… win or the bayonet end or the noose of the hollow crown.

Rochambeau

October 18th, 1781.

The code word, Alexander Hamilton informed him: Rochambeau. We face them now, staring into the whites of their eyes, so the enemy cannot run. Alexander Hamiton and his Achilles, to his Patroclus to his Achilles, John Laurens would lead infantry. Benjamin would, such as his rank of 2nd continental light dragoon said, was to cut them off as calvary give little room for them to hold ground, or fight back. It would be brutal, Hamilton bluntly said to Tallmadge, but necessary. Tallmadge nodded, despite himself and gave Hamilton a friendly and determined smile, this is what Benjamin’s been fighting for since 1776. He was not about to give these men in red an inch. For Nathan, for how he couldn’t spare Major Andre, or Sarah, to end the conflict Miss Shippen was running from. For Anna Strong’s revenge, for Caleb and the ring, for their America.

Not charging into the frey not yet. Alexander and Laurens move silently in the dead of night removing the bullets from their guns until absolutely necessary. With the British defences pummelled to the ground, they take the redoubts with comparative ease. Until the English answer with their remaining cannons and the fog and fumes of war. Laurens and Hamilton stay their ground. Try as men might atop his horse, the men in red are easy targets. He cuts them down hacking and slashing with all his rage and all his might, like Achilles at Troy. They attempt to fire upon him and the calvary he is missed. One man’s horse is shot from under him and he hears the screams of an injured or dying animal, still, they keep fighting. Cannon fire shoots back in response, a last-ditch attempt by the English to hold their position. By 4 am it is decided in the end the total casualties amounted to 857, for both sides. But, outgunned, outplayed, exhausted and ill the English now as weary as their patriot enemies surrender.

The world turned upside down

October 19th, 1781.

A young redcoat stands atop the defences with a white handkerchief, and a drummer accompanies him. By 10:30 am the English offer sufficient terms of surrender. Humiliated, or ill, Cornwallis neglects to be present. Benjamin cannot help but scoff but he suppresses it if only out of politeness and civility to the now-defeated enemy.

A line is formed and sure enough, Washington receives the sword of the enemy, a symbol of surrender and a remarkably civil surrender at that. Save for poor Banastre Tarleton, not with his reputation for brutality. However, the English refuse to look at the Patriots, to whom the French and English are subordinate.

The Marquis de Lafayette merely sighed softly. “Yankee doodle,” he commanded, as the British drummer and fifer played the folk song, ‘The world turned upside down.’ There is a look of disbelief on the faces of the English, but, Tallmadge cannot help but return it with a grin, smug perhaps, but, this is what he had spent six years fighting for! What is more, he had survived.

#muse: benjamin tallmadge#history doesn’t repeat it rhymes / solos#battle of Yorktown#american revolution#18th century#historical fiction#my writing#on this day in history#ic / permitted excesses#benjamin tallmadge#ben tallmadge#aes / the lovers you take are dangerous#turn: washington's spies#turn amc#amc turn#turn washington's spies#drabbles#solos#drabble#for skill in music named / queue#violence cw#war cw

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every election cycle there is despair. Thomas Paine had something to say about that:

“THESE are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.”

Thomas Paine, The American Crisis, 1776

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomas Estevan

“THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated.”

~ Thomas Paine, The Crisis No. I (written 19 December 1776, published 23 December 1776)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

SS&SP CHAPTER 11

Hi everyone! SS&SP chapter 11 is FINALLY out, and you can read it here! I hope you guys enjoy it!

PS: To keep my fic protected from AI, I made it available only to people with an ao3 account, so sorry for the inconvenience! If you don't have an account, I highly recommend getting one cause it helps us writers out!

#WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO#the summer soldier and the sunshine patriot#SS&SP#Elizabeth Walker#amanda rambles about SS&SP (again)#otp: first thing in the morning#Benjamin Tallmadge x OC#Benjamin Tallmadge

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer

soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink

from the service of his country; but he that stands it now,

deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like

hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with

us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: It is

dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows

how to set a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange

indeed, if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be

highly rated.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service to his country, but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not casily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

— Thomas Paine.

0 notes

Text

I Got Through 2020. Here's How I'm Going To Get Through 2024

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country, but he that stands by it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered, yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Heather Cox Richardson

December 25, 2022 (Sunday)

In the summer heat of July 1776, revolutionaries in 13 of the British colonies in North America celebrated news that the members of the Second Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, had adopted the Declaration of Independence. In July, men had cheered the ideas that “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States,” and that, in contrast to the tradition of hereditary monarchy under which the American colonies had been organized, the representatives of the thirteen united states intended to create a nation based on the idea “that all men are created equal” and that governments were legitimate only if those they governed consented to them.

But then the British responded to the colonists’ fervor with military might. They sent reinforcements to Staten Island and Long Island and by September had forced General George Washington to evacuate his troops from New York City. After a series of punishing skirmishes across Manhattan Island, by November the British had pushed the Americans into New Jersey. They chased the colonials all the way across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania.

By mid-December the future looked bleak for the Continental Army and the revolutionary government it backed. The 5,000 soldiers with Washington who were still able to fight were demoralized from their repeated losses and retreats, and since the Continental Congress had kept enlistments short so they would not risk a standing army, many of the men would be free to leave the army at the end of the year, weakening it even more.

As the British troops had taken over New York City and the Continental soldiers had retreated, many of the newly minted Americans outside the army had come to doubt the whole enterprise of creating a new, independent nation based on the idea that all men were created equal. Then things got worse: as the American soldiers crossed into Pennsylvania, the Continental Congress abandoned Philadelphia on December 12 out of fear of a British invasion, regrouping in Baltimore (which they complained was dirty and expensive).

By December, the fiery passion of July had cooled. “These are the times that try men’s souls,” read a pamphlet published in Philadelphia on December 19. “The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

The author of The American Crisis was Thomas Paine, whose January 1776 pamphlet Common Sense had solidified the colonists’ irritation at the king’s ministers into a rejection of monarchy itself, a rejection not just of King George III, but of all kings.

Now he urged them to see the experiment through. He explained that he had been with the troops as they retreated across New Jersey and, describing the march for his readers, told them “that both officers and men, though greatly harassed and fatigued, frequently without rest, covering, or provision, the inevitable consequences of a long retreat, bore it with a manly and martial spirit. All their wishes centred in one, which was, that the country would turn out and help them to drive the enemy back.”

For that was the crux of it. Paine had no doubt that patriots would create a new nation, eventually, because the cause of human self-determination was just. But how long it took to establish that new nation would depend on how much effort people put into success. “I call not upon a few, but upon all: not on this state or that state, but on every state: up and help us; lay your shoulders to the wheel; better have too much force than too little, when so great an object is at stake,” Paine wrote. “Let it be told to the future world, that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive, that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet and to repulse it.”

In mid-December, British commander General William Howe had sent most of his soldiers back to New York to spend the winter, leaving garrisons across the river in New Jersey to guard against Washington advancing.

On Christmas night, having heard that the garrison at Trenton was made up of Hessian auxiliaries who were exhausted and unprepared for an attack, Washington crossed back over the icy Delaware River with 2400 soldiers in a winter storm. They marched nine miles to attack the garrison, the underdressed soldiers suffering from the cold and freezing rain. Reaching Trenton, they surprised the outnumbered Hessians, who fought briefly in the streets before they surrendered.

The victory at the Battle of Trenton restored the colonials’ confidence in their cause. Soldiers reenlisted, and in early January they surprised the British at Princeton, New Jersey, driving them back. The British abandoned their posts in central New Jersey, and by March the Continental Congress moved back to Philadelphia. Historians credit the Battles of Trenton and Princeton with saving the Revolutionary cause.

“Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered,” Paine wrote, “yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.”

0 notes

Text

"The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman."

- Thomas Paine

1 note

·

View note

Text

July 4th 1776 - July 4th 2022

🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸

THESE are the times that TRY MEN'S SOULS. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives everything its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as FREEDOM should not be highly rated. – Thomas Paine

1 note

·

View note

Text

I saw some Canon x OC hate earlier, so what did I do? I DREW SOME CANON x OC, BAYBEE, featuring my own garbage plate creations, as well as the glorious OC from this equally glorious fic by @tallmadgeandtea (the second drawing). I’ll color these eventually, but for now just enjoy them in their raw/half-arsed glory lol.

#mine#fan art#tallmadgeandtea#benjamin tallmadge#ben tallmadge#turn fan art#turn#turn amc#original female character#ben x oc#anywhos pic 1 is ben and lizzie from to kiss to consume#pic 2 is ben and elizabeth from the summer soldier & the sunshine patriot#and pic 3 is ben and clara from the world is made wrong#i've drawn my ocs in the past but never with canon characters#which is making me lowkey laugh cuz idk i can't ever take myself seriously#also amanda i hope it's okay i drew your OC i just?? love your fic a lot??#ALSO CAN I EVEN CALL YOU AMANDA?#i always feel weird calling ppl by name when i've never had an official convo with them lol#i am a messTM

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Simplified Retelling of the Life of Thomas Paine

Note: This post is mostly a compilation of important Events in the Timeline of Thomas Paine’s Life. It doesn’t go very in-depth on his Character or Personal Life. Any further questions are encouraged and appreciated. Also, this was meant to go on my other account, @publius-library, but I’m leaving it as the last informational post on this blog.

Thomas Paine was born on January 29, 1737, in Norfolk, England to a conservative, religious Family. This is Ironic, considering his Politics later in Life. He received a basic Eduction, teaching him rudimentary Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic. At the age of 13, Paine began to work with his Father as a corset Maker, the first Occupation in a long line of many other failed attempts.

Eventually, Paine maintained a job as an Officer of Excise for a period of Time. His job was to find Smugglers and collect Taxes on Liquor and Tobacco. During this Time, Paine had two unsuccessful Marriages, and an unhappy Career, which ended in an argument over his insufficient Pay in 1772.

Then, Paine met Benjamin Franklin in London, who advised him to go to America, and gave him several Letters of recommendation. Paine listened, and arrived in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774. Franklin’s Son-in-Law introduced him to Robert Aitkin, whom he helped form the Pennsylvania Magazine, which Paine edited and wrote poems and articles (including an attack on slavery) for during a Span of 18 Months.

After the Battle of Lexington and Concord, Paine published his Opinion that the American Cause should be a demand for Independence, not a Tantrum over Taxes. His Patriotic Fervor became more known to the Public when he published Common Sense on January 10, 1776. The fifty-page Pamphlet sold over 500,000 Copies within a few Months. Paine’s strong Words were used in similar Documents, such as the Declaration of Independence.

Paine continued to add Fuel to the American Flame by publishing 16 other Papers (while serving as an Aide-de-Camp to Nathanael Greene), entitled The Crisis, between 1776 and 1783, which he signed under the pseudonym, Common Sense. The First of these Papers was published on December 19, 1776, when the Continental Army was facing potential Ruin, so the Paper was read Aloud to the Troops, per Washington’s orders.

“These are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us—that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.” -Thomas Paine, 1776

Combined with the Inspiration Soldiers drew from the Battle of Trenton, caused the American Troops to reenlist on January 1st, which previously had been doubtful.

Paine was appointed as the Clerk of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania on November 2, 1779 after an unsuccessful career on the Committee for Foreign Affairs. From this position, Paine had many Chances to observe the state of Continental Troops. Paine took $500 from his own Salary, and started a Subscription for relief of Soldiers.

After the War came to it’s conclusion, Paine refused to accept Compensation for his Writings in order to keep the prices of the Publications cheap and accessible for all Citizens. As a Result, Paine faced many financial Hardships, and petitioned Congress for financial Support, which was backed by George Washington. However, this Petition was buried by Paine’s rivals, although he was given 500 pounds and a New York farm by the State of Pennsylvania. In his personal life, Paine dedicated his Time to Inventions, which included an iron Bridge without piers, and a smokeless Candle.

In April of 1787, Paine left for Europe to promote his Bridge across the Schuylkill River. In December of 1789, he published an anonymous warning against William Pitt’s attempt to involve England in a War with France over the Dutch Republic. He reminded the British Citizen that war had never had “but one thing certain, and that is increase of taxes.”

During his stay in Europe, Edmund Burke made an attack on the uprising of the French, which would later come to a boil as the French Revolution. Paine published the Rights of Man on March 13, 1791, and the pamphlet was a sensation, being widely distributed by Jeffersonian societies. Federalists weren’t fans of Paine at this point. Burke eventually replied to Paine, causing the latter to publish Rights of Man, Part II on February 17, 1792.

More than a Defense of the French Revolutionaries, the Rights of Man became an analysis of the core Reasons for European Insurrection, and potential Remedies for social issues, including arbitrary Government, Poverty, Illiteracy, Unemploym’t, and War. Additionally, Paine spoke out in favor of Republicanism over the traditional Monarchy, outlined plans for more easily accessible education, relief for the Poor, pensions for Elders, and public Works for the Unemployed.

This proved a bit too ambitious for Paine’s contemporaries. His works were interpreted as a rallying call for Anarchy. The English Government banned Paine’s work and put out a Warrant for the Author’s Arrest. At the time, Paine was en route to France to serve in the National Convention. Paine was tried in absentia, and was found guilty of Seditious Libel and was declared an Outlaw.

In France, Paine was enthusiastically received, despite poor French skills. Paine hailed the Abolition of the Monarchy, but showed great distaste for The Terror, which were the central sentiments of the American or Fayette (as in Lafayette) Party. Paine attempted to save Louis XVI, favoring Banishment over execution, which would lead to Diplomatic Troubles with the American Government, who had made their Treaty with the King.

As with many others in the American Party, Paine was imprisoned by Radicals from December 28, 1793 until November 4, 1794. He was released after Robespierre’s Execution, and was readmitted to the Convention, despite his severe Illness. While he was in prison, Age of Reason was published, and Part II after his release. In these writings, Paine showed that, although he prayed to a Deity, he deplored Organized Religion. Since nothing goes well for Paine for longer than a Year, he was deemed an Atheist, which was synonymous with uncivilized and without morals at the time. Paine published Agrarian Justice in 1797, where he attacked inequalities in property Ownership, which only multiplied his political enemies.

Paine remained in France until September 1, 1802, then returned to the United States, where he discovered that all his Services to the Country had been forgotten, and replaced with a Reputation of an Infidel. Paine entered into Poverty, poor Health, and Alcoholism, but still continued his Attacks on Social Injustice.

One other Publication I think is noteworthy to mention is the Prospect, which struck organized Religion at it’s core. In this edition of Thomas Paine Hates Everyone, he mentions the recent death of the First Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton. After Hamilton’s death in the duel with Aaron Burr, the sitting Vice President, he was denied communion by a Minister. He speaks directly to that Minister when he writes,

“I regret the fate of General Hamilton, and I so far hope with you that it will be a warning to thoughtless man not to sport away the life that God has given him; but with respect to other parts of your letter I think it very reprehensible and betrays great ignorance of what true religion is. But you are a priest, you get your living by it, and it is not your worldly interest to undeceive yourself...

“You tell people, as you told Hamilton, that they must have faith. Faith in what? You ought to know that before the mind can have faith in any thing, it must either know it as a fact, or see cause to believe it on the probability of that kind of evidence that is cognizable by reason...” - Thomas Paine, 1804

Paine died in New York in 1809, and was buried in New Rochelle on his Farm.

Sources:

Thomas Paine - Britannica

Thomas Paine documents - Founders Online

Common Sense by Thomas Paine - The Project Gutenberg

The Crisis by Tom. P. - The Project Gutenberg

The Rights of Man by Tom. P. - The Project Gutenberg

Public Good by Tom. P. - Thomas Paine National Historical Association

Age of Reason by Tom. P. - The Project Gutenberg

Writings of Thomas Paine - The Project Gutenberg

#thomas paine#amrev#amrev history#the american revolution#american history#common sense#1700s#founding fathers#this man gives me heartburn (affectionate)

38 notes

·

View notes