#the tale of earendel

Text

BoLT legit says “Eärendel reads tales and prophecies in the waters” which is ???!!! and now I wanna hc him having a sort of synesthesia (?) like seeing words and visions of past and future from the music in the waters (lol here’s my url) that tells the story of the world… And then I think it makes sense this is the result of combining Tuor’s sea-longing and Idril’s foresight…haha he’s such a…hybrid…baby ok I’m not funny at all

#might make a longer post to rephrase#always get interrupted by random ideas when I read Tolkien’s random ideas lol#earendil#the tale of earendel#the book of lost tales

133 notes

·

View notes

Note

Finrod talking about when Men study a thing “it reminds them of some other clearer thing” makes me think elves have a sense of mystery around the possibility of this place beyond Arda human spirits come from and go after death, like soul aliens, not as lordly in Andreth’s view but curious like learning about the possibility of extraterrestrial life. I wonder if one who chooses mortality for its own sake, besides wanting to escape Arda Marred, is drawn to that place as the destination of escape.

I headcanon this as a big part of Elros's choice tbh! Though I like to think of his choice as being somewhat an emergent property of different tangles too, like 'only thinking about/valuing this so deeply and personally in the first place because of this-world deep affinity to Men and the concept of numenor and the war of wrath' etc.

but also I think this is also a lot of how Eärendel (in the BOLT, distinct from Eärendil in the published Silm) is portrayed, albeit much of his actions are also subjected to many circumstantial confounding variables (a mainstay of Tolkien that is really good imo). he’s very Human but also his perspective is i think different from pure humans in part bc of his peredhil status

#SO SORRY I MISSED THIS FOR SO LONG!!!!!!! my notifs are garbage since the last update#echoofthemusic#immortality and mortality#elros#earendil#the tale of earendel

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tale of Earendel

It’s complicated, scattered, and in most parts, unwritten :) Earendel’s voyages and adventures on various islands remind me of The Voyage of the 'Down Treader' ^^

We could have even had mermaids!!! Alas...

* * *

I love these verses from "The Bidding of the Minstrel, from the Lay of Earendel":

But the music is broken, the words half-forgotten,

The sunlight has faded, the moon is grown old,

The Elven ships foundered or weed-swathed and rotten,

The fire and the wonder of hearts is acold.

(...)

The song I can sing is but shred one remembers

Of golden imaginings fashioned in sleep,

A whispered tale told by the withering embers

Of old things far off that but few hearts keep.

0 notes

Text

ICYMI: fragments of Kidnap Fam fix-it by Jirt

Here Damrod and Díriel ravaged Sirion, and were slain. Maidros and Maglor were there, but they were sick at heart. This was the third kinslaying. The folk of Sirion were taken into the people of Maidros, such as yet remained; and Elrond was taken to nurture by Maglor. (HoME 5, The Later Annals of Beleriand)

The Third and Last Kinslaying. The Havens of Sirion destroyed and Elros and Elrond sons of Earendel taken captive, but are fostered with care by Maidros (HoME 11, The Tale of Years)

Yet not all the Eldalië were willing to forsake the Hither Lands where they had long suffered and long dwelt; and some lingered many an age in the West and North, and especially in the western isles and in the Land of Leithien. And among these were Maglor, as hath been told; and with him for a while was Elrond Halfelven, who chose, as was granted to him, to be among the Elf-kindred; but Elros his brother chose to abide with Men. (HoME 5, Quenta Silmarillion)

#kidnap fam#maedhros#maglor#elrond#elros#canon fix it#just throw the Ambarussa under the bus why don't you#omg but Elrond and Maglor after the First Age#'for a while'#by which you mean right through the Third Age

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

So in the BoLT I, there’s a chapter called ‘The Tale of Earendel’ and, as you may have guessed, it’s all about Eärendil. Okay, fair enough. Most of it is in outline form with poems interspersed, but! Something intriguing I found was (during the bit about Eärendil trying to find Valinor):

“Driven west. Ungweliante. Magic Isles. Twilit Isle. Littleheart’s gong awakes the sleeper in the Tower of Pearl.” And then there’s a note with that sentence and I go to check the notes section and:

“Struck out here: the Sleeper is Idril but he [Eärendil] does not know”

#nolo reads bolt#idril celebrindal#book of lost tales#earendil#aa....aaa...AAAA.#sorry this is canon to me now#;u;

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Norsery Rhymes from A to Z

Happy Thorsday - Earendel, The Valiant and Brave Star Toe of the Morning

Well here we are another Thor’s Day and another 20 min sketch of a Norse (and Germanic) mythological characters. This week it looks like we’re finally out of the D’s and onto the few E’s there are. It’s Earendel / Earendil / Earendell / Aurvandel / Aurvandill / Aurendil / Auriwandalo / and Auzandil mentioned in the Prose Edda's Skáldskaparmál, Gothica Bononiensia and the Old English Corpus in various forms.

Known as ‘The Valiant’ and ‘The Brave’, he’s also called ‘The Luminous Wanderer’ and ‘The Light of the Morning’, ‘The Radiant’, and ‘The Brilliant Traveler’.

His name despite all of the various regional versions all mean some variation of a rising or shining ray of light. Depending on which version it can more specifically be translated as ‘the dawn bringer’, ‘the rising light’, or ‘the brilliance’, or ‘the ray of light’, or ‘the shining beam of light’, or most commonly ‘the light of the morning star’. It can also have connotations with ‘wandering’, ‘travelling’ or ‘adventuring’.

Married to the witch and Seidhr sorceress (soothsaying, or seer) Gróa / Groa (Gefion), and possibly father to Svipgar the hero of the Grógaldr and Fjölsvinnsmál.

Earendel was implied to be a hero and adventurer in his own right. But he is best well known for his traveling's with his friend Thor. Who had been taken captive by the stone Jötunn Hrungnir. After which, while returning from their adventure from defeating the giant in Jotenheim. Thor had shards of a magic whetstone in his head that Hrungnir had thrown at him but had been shattered by Mjolnir. Earendil on his way home and Thor travelling with him so that his wife Groa could use her power to remove the shards and heal him.

When they came to the Élivágar river in Ginnungagap, Thor who was immune to the effects of this river from before time, decided to carry Earendel across in an basket to protect him from the cold. So with Earendel in to the basket, Thor wasn’t careful about how he was squished in there and his big toe was exposed to the cold of the primordial river and got frostbite. Thor not wanting to see the damage spread, broke off his toe and threw it in the sky where it became the bright morning (or other) star. Once Earendil could walk Thor went on ahead to Groa to have the stone shards removed. But while she was weaving the incantation to remove them he started her with the tale of the toe and her husbands immanent return which caused her to falter and made the stone get stuck there beyond her ability to help.

And to reuse my joke from my Aurvandil post. Earendel may have been luminous and valiant. But he forgot the first rule of adventuring... Bring warm socks. It also wouldn’t hurt to have a towel.

#norsemythology#earendel#aurvandill#thor#groa#svipgar#Jotun#giant#morningstar#norse#myth#mythology#conceptart#characterdesign#lineart#linedrawing#art#characterart#Illustration#drawing#sketch#star

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not to be tedious, but Idril does indeed do some wreckage in HoME! "At length she had sped the most part of her guard down the tunnel with Earendel, constraining them to depart with imperious words, yet was her grief great at that sundering. She herself would bide, said she, nor seek to live after her lord; and then she fared about gathering womenfolk and wanderers and speeding them down the tunnel, and smiting marauders with her small band; nor might they dissuade her from bearing a sword."

My god, you’re right. In between the swooning and and the hair dragging she does some smiting! BRB - adding more dead bodies to Fair They Wrought Us.

The Fall of Gondolin in the Book of Lost Tales II careens between amazing details and stuff that you know Tolkien would’ve changed if he ever finished one of his later narratives. I’m not sure if Idril’s smiting would’ve stuck, but I wish we could have read a post LOTR Fall of Gondolin regardless. IMO Tolkien got better at writing women in between the late teens when he wrote TFOG and his later stuff from LOTR and later in the 50s.

#ty for the correction#Tolkien fans are nothing if not tedious#not shocking that Tolkien improved as a writer from his mid twenties to his fifties!#that's the dream#Idril#Gondolin#siadea#askaipi

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

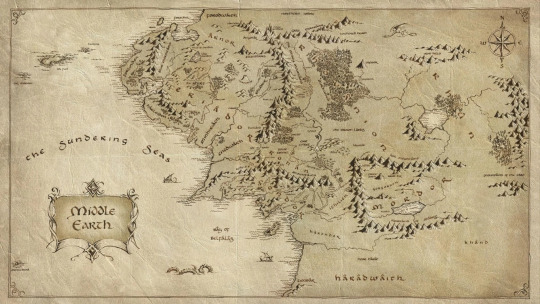

Middle-earth / Средиземье

"Middle-earth", or Endor in Quenya (Ennor in Sindarin) - and in The Book of Lost Tales the Great Lands - are the names used for the habitable parts of Arda after the final ruin of Beleriand, east across the Belegaer from Aman.

This continent was north of the Hither Lands shown in the Ambarkanta, and west of the East Sea; and throughout the First and Second Ages it underwent dramatic geographical changes, caused by Iluvatar.

Name

he term "Middle-earth" was not invented by Tolkien. Rather, it comes from Middle English middel-erde, itself a folk-etymology for the Old English word middangeard (geard not meaning Earth, but rather enclosure or place, thus yard, with the Old Norse word miðgarðr being a cognate). It is Germanic for what the Greeks called the οικουμένη (oikoumenē) or "the abiding place of men", the physical world as opposed to the unseen worlds (The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, 151). The word Mediterranean comes from two Latin stems, medi- , amidst, and terra, (earth/land), meaning "the sea placed at the middle of the Earth / amidst the lands".

Middangeard occurs six times in Beowulf, which Tolkien translated and on which he was arguably the world's foremost authority. (See also J. R. R. Tolkien for discussion of his inspirations and sources). See Midgard and Norse mythology for the older use.

Tolkien was also inspired by this fragment:

Hail Earendel, brightest of angels / above the middle-earth sent unto men.

in the "Crist" poem by Cynewulf. The name earendel (which may mean the 'morning-star' but in some contexts was a name for Christ) was the inspiration for Tolkien's mariner Eärendil.

"Middle-earth" was consciously used by Tolkien to place The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion, and related writings.

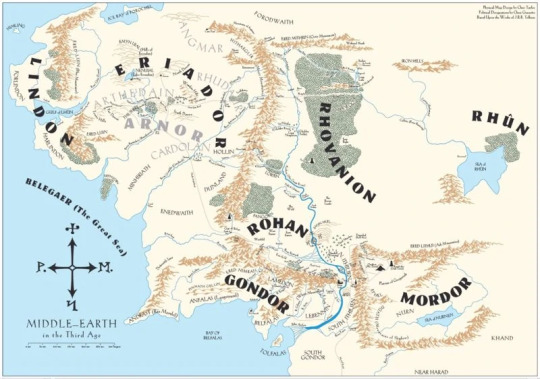

Map of the Western part of Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age

Tolkien first used the term "Middle-earth" in the early 1930's in place of the earlier terms "Great Lands", "Outer Lands", and "Hither Lands" to describe the same region in his stories. "Middle-earth" is specifically intended to describe the lands east of the Great Sea (Belegaer), thus excluding Aman, but including Harad and other mortal lands not visited in Tolkien's stories. Many people apply the name to the entirety of Tolkien's world or exclusively to the lands described in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion.

In ancient Germanic and mythology, the universe was believed to consist of multiple interconnected physical worlds (in Nordic mythology 9, in West Germanic and English mythology, 8). The world of Men, the Middle-earth, lay in the centre of this universe. The lands of Elves, gods, and Giants lay across an encircling sea. The land of the Dead lay beneath the Middle-earth. A rainbow bridge, Bifrost Bridge, extended from Middle-earth to Asgard across the sea. An outer sea encircled the seven other worlds (Vanaheim, Asgard, Alfheim, Svartalfheim, Muspellheim, Niflheim, and Jotunheim). In this conception, a "world" was more equivalent to a racial homeland than a physically separate world.

The world

Tolkien stated that the geography of Middle-earth was intended to align with that of the real Earth in several particulars. (Letter 294) Expanding upon this idea some suggest that if the map of Middle-earth is projected on our real Earth, and some of the most obvious climatological, botanical, and zoological similarities are aligned, the Hobbits' Shire might lie in the temperate climate of England, Gondor might lie in the Mediterranean Italy and Greece, Mordor in Sicily, South Gondor and Near Harad in the deserts of Northern Africa, Rhovanion in the forests of Germany and the steppes of Western and Southern Russia, and the Ice Bay of Forochel in the fjords of Norway. Far Harad may have corresponded with Southern Africa, and Rhûn corresponded with the whole of Asia. The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are presented as Tolkien's retelling of events depicted in the Red Book of Westmarch, which was written by Bilbo Baggins, Frodo Baggins, and other Hobbits, and corrected and annotated by one or more Gondorian scholars. Years after publication, Tolkien 'postulated' in a letter that the action of the books takes place roughly 6,000 years ago, though he was not certain.

Tolkien wrote extensively about the linguistics, mythology and history of the world, which provide back-story for these stories. Many of these writings were edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher.

Notable among them is The Silmarillion, which provides a creation story and description of the cosmology which includes Middle-earth. The Silmarillion is the primary source of information about Valinor, Númenor, and other lands. Also notable are Unfinished Tales and the multiple volumes of The History of Middle-earth, which includes many incomplete stories and essays as well as numerous drafts of Tolkien's Middle-earth mythology, from the earliest forms down through the last writings of his life.

Cosmology

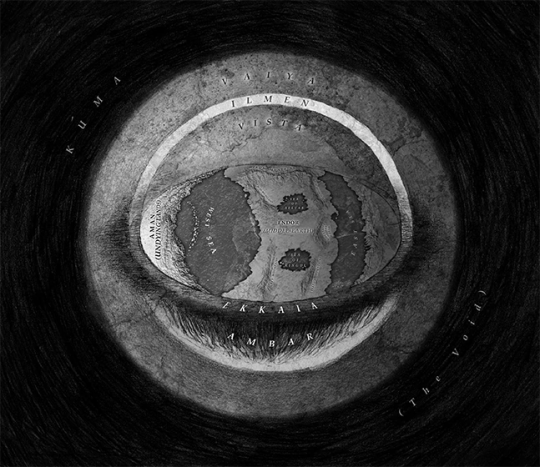

A depiction of the initial geography of Eä

The supreme deity of Arda is called Eru Ilúvatar. In the beginning, Ilúvatar created spirits named the Ainur and he taught them to make music. After the Ainur had become proficient in their skills, Ilúvatar commanded them to make a great music based on a theme of his own design. The most powerful Ainu, Melkor (later called Morgoth or "Dark Enemy" by the elves), Tolkien's equivalent of Satan, disrupted the theme, and in response Ilúvatar introduced new themes that enhanced the music beyond the comprehension of the Ainur. The movements of their song laid the seeds of much of the history of the as yet unmade universe and the people who were to dwell therein. Then Ilúvatar stopped the music and he revealed its meaning to the Ainur through a Vision. Moved by the Vision, many of the Ainur felt a compelling urge to experience its events directly. Ilúvatar therefore created Eä, the universe itself, and some of the Ainur went down into the universe to share in its experience. But upon arriving in Eä, the Ainur found it was shapeless because they had entered at the beginning of Time. The Ainur undertook great labours in these unnamed "ages of the stars", in which they shaped the universe and filled it with many things far beyond the reach of Men. In time, however, the Ainur formed Arda, the abiding place of the Children of Ilúvatar, Elves and Men. The fifteen most powerful Ainur are called the Valar, of whom Melkor was the most powerful, but Manwë was the leader. The Valar settled in Arda to watch over it and help prepare it for the awakening of the Children.

Arda began as a single flat world, which the Valar gave light to through two immense lamps. Melkor destroyed the lamps and brought darkness to the world. The Valar retreated to the extreme western regions of Arda, where they created the Two Trees to give light to their new homeland. After many ages, the Valar imprisoned Melkor to punish and rehabilitate him, and to protect the awakening Children. But when Melkor was released he poisoned the Two Trees. The Valar took the last two living fruit of the Two Trees and used them to create the Moon and Sun, which remained a part of Arda but were separate from Ambar (the world).

Before the end of the Second Age, when the Men of Númenor rebelled against the Valar, Ilúvatar destroyed Númenor, separated Valinor from the rest of Arda, and formed new lands, making the world round. Only Endor remained of the original world, and Endor had now become Eurasia.

Geography

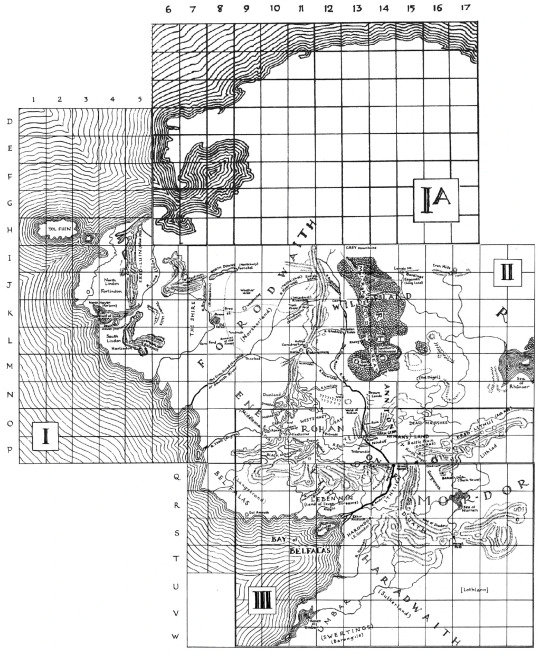

An expanded, composite map of Middle-earth drawn by Christopher Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien never finalized the geography for the entire world associated with The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. In The Shaping of Middle-earth, volume IV of The History of Middle-earth, Christopher Tolkien published several remarkable maps, of both the original flat earth and round world, which his father had created in the latter part of the 1930s. Karen Wynn Fonstad drew from these maps to develop detailed, but non-canonical, "whole world maps" reflecting a world consistent with the historical ages depicted in The Silmarillion, The Hobbit, and The Lord of the Rings.

Maps prepared by Christopher Tolkien and J.R.R. Tolkien for the world encompassing The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were published as foldouts or illustrations in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. Early conceptions of the maps provided in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings were included in several volumes, including "The First Silmarillion Map" in The Shaping of Middle-earth, "The First Map of the Lord of the Rings" in The Treason of Isengard, "The Second Map (West)" and "The Second Map (East)" in the War of the Ring, and "The Second Map of Middle-earth west of the Blue Mountains" (also known as "The Second Silmarillion Map") in The War of the Jewels.

Endor, the Quenya term for Middle-earth, was originally conceived of as conforming to a largely symmetrical scheme which was marred by Melkor. The symmetry was defined by two large sub-continents, one in the north and one in the south, with each of them boasting two long chains of mountains in the eastward and westward regions. The mountain chains were given names based on colours (White Mountains, Blue Mountains, Grey Mountains, and Red Mountains).

The various conflicts with Melkor resulted in the shapes of the lands being distorted. Originally, there was a single inland body of water, in the midst of which was set the island of Almaren where the Valar lived. When Melkor destroyed the lamps of the Valar which gave light to the world, two vast seas were created, but Almaren and its lake were destroyed. The northern sea became the Sea of Helcar (Helkar). The lands west of the Blue Mountains became Beleriand (meaning, "the land of Balar"). Melkor raised the Misty Mountains to impede the progress of the Vala Orome as he hunted Melkor's beasts during the period of darkness prior to the awakening of the Elves.

Additional changes have occurred when Valar have assaulted Utumno. The North-west of the Middle-earth, where Melkor met the Valar host, was "much broken". The sea between the Middle-earth and Aman widened, with many bays created, including one which was the confluence of Sirion. The highland of Dorthonion and the mountains about Hithlum were also a result of the battles. Since the changes mentioned include both the beginning and the ending points of Sirion, it is possible the river itself was created at the same time.

The violent struggles during the War of Wrath between the Host of the Valar and the armies of Melkor at the end of the First Age brought about the destruction of Beleriand. It is also possible that during this time the inland sea of Helcar was drained.

The world, not including associated celestial bodies, was identified by Tolkien as "Ambar" in several texts, but also identified as "Imbar", the Habitation, in later post-Lord of the Rings texts. From the time of the destruction of the two lamps until the time of the Downfall of Númenor, Ambar was supposed to be a "flat world", in that its habitable land-masses were all arranged on one side of the world. His sketches show a disk-like face for the world which looked up to the stars. A western continent, Aman, was the home of the Valar (and the Eldar). The middle lands, Endor, were called "Middle-earth" and the site of most of Tolkien's stories. The eastern continent was not inhabited.

When Melkor poisoned the Two Trees of the Valar and fled from Aman back to Endor, the Valar created the Sun and the Moon, which were separate bodies (from Ambar) but still parts of Arda (the Realm of the Children of Ilúvatar). A few years after publishing The Lord of the Rings, in a note associated with the unique narrative story "Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth" (which is said to occur in Beleriand during the War of the Jewels), Tolkien equated Arda with the Solar System; because Arda by this point consisted of more than one heavenly body.

Map of Middle-earth in Peter Jackson's films

According to the accounts in both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, when Ar-Pharazôn invaded Aman to seize immortality from the Valar, they laid down their guardianship of the world and Ilúvatar intervened, destroying Númenor, removing Aman "from the circles of the world", and reshaping Ambar into the round world of today. Akallabêth says that the Númenóreans who survived the Downfall sailed as far west as they could in search of their ancient home, but their travels only brought them around the world back to their starting points. Hence, before the end of the Second Age, the transition from "flat earth" to "round earth" had been completed.

The Endor continent became approximately equivalent to the Eurasian land-mass, but Tolkien's geography does not provide any exact correlations between the narrative of The Lord of the Rings and Europe or near-by lands. It is therefore assumed that the reader understands the world underwent a subsequent undocumented transformation (which some people speculate Tolkien would have equated with the Biblical deluge) sometime after the end of the Third Age, or possibly at the fall of Sauron itself at the end of the Third Age. Another explanation is that many places shifted location, the Misty Mountains moving North to Scandinavia, the White Mountains rotating to become the Alps and the mountains of the west Balkans, Near Harad moving south and west to become the Sahara, Eriador flooding to become northern France and the British Isles, and so on. This would not be the first time that this had happened, as it seems that a consequence from the Siege of Utumno was that Endor rotated eastward, its axis the north pole.

People

Middle-earth was home to several distinct intelligent species. First are the Ainur, angelic beings created by Ilúvatar. The Ainur sing for Ilúvatar, who creates Eä to give existence to their music in the cosmological myth called the Ainulindalë, or "Music of the Ainur". Some of the Ainur then enter Eä, and the greatest of these are called the Valar. Melkor (later called Morgoth), the chief personification of evil in Eä, is initially one of the Valar.

The other Ainur who enter Eä are called the Maiar. In the First Age the most active Maia is Melian, wife of the Elven King Thingol; in the Third Age, during the War of the Ring, five of the Maiar have been embodied and sent to Endor to help the free people to overthrow Sauron. Those are the Istari (or Wise Ones) (called Wizards by Men), including Gandalf, Saruman, Radagast, Alatar and Pallando. There were also evil Maiar, called Umaiar, including the Balrogs and the second Dark Lord, Sauron.

Later come the Children of Ilúvatar: Elves and Men (men awoke in the first year of the sun), intelligent beings created by Ilúvatar alone. The Silmarillion tells how Elves and Men awaken and spread through the world. The Dwarves are said to have been made by the Vala Aulë, who offered to destroy them when Ilúvatar confronted him. Ilúvatar forgives Aulë's transgression and adopts the Dwarves. Three tribes of Men who ally themselves with the Elves of Beleriand in the First Age are called the Edain.

As a reward for their loyalty and suffering in the Wars of Beleriand, the descendants of the Edain are given the island of Númenor to be their home. But as described in the section on Middle-earth's history, Númenor is eventually destroyed and a remnant of the Númenóreans establish realms in the northern lands of Endor. Those who remained faithful to the Valar found the kingdoms of Arnor and Gondor. They are then known as the Dúnedain, whereas other Númenórean survivors, still devoted to evil but living far to the south, become known as the Black Númenóreans.

Tolkien identified Hobbits as an offshoot of the race of Men. Although their origins and ancient history are not known, Tolkien implied that they settled in the Vales of Anduin early in the Third Age, but after a thousand years the Hobbits began migrating west over the Misty Mountains into Eriador. Eventually, many Hobbits settled in the Shire.

After they are granted true life by Ilúvatar, the Dwarves' creator Aulë lays them to sleep in hidden mountain locations. Ilúvatar awakens the Dwarves only after the Elves have awakened. The Dwarves spread throughout northern Endor and eventually found seven kingdoms. Two of these kingdoms, Nogrod and Belegost, befriend the Elves of Beleriand against Morgoth in the First Age. The greatest Dwarf kingdom is Khazad-dûm, later known as Moria.

The Ents, "shepherds of the trees", were created by Ilúvatar at the Vala Yavanna's request to protect trees from the depredations of Elves, Dwarves, and Men.

Orcs and Trolls were evil creatures bred by Morgoth. They were not original creations but rather "mockeries" of Ents and the Children of Ilúvatar, since only Ilúvatar has the ability to give being to things. Their origins are not detailed (Tolkien considered many possibilities and frequently changed his mind). It seems most likely that the Orcs were bred largely from corrupted Elves or Men, or both. Late in the Third Age, the Uruks or Uruk-hai appear: a race of Orcs of great size and strength. Saruman bred Orcs and Men together to produce "Men-orcs" and "Orc-men"; at times, some of these are called "half-orcs" or "goblin-men".

Seemingly sapient animals also appear, such as the Eagles, Huan the Great Hound from Valinor, and the Wargs. The Eagles are created by Ilúvatar along with the Ents, but in general these animals' origins and nature are unclear. Some of them might be Maiar in animal form, or perhaps even the offspring of Maiar and normal animals.

It is unknown to what people of Middle-earth Tom Bombadil belonged. As to his nature, Tolkien himself said that some things should remain mysterious in any mythology, hidden even to its inventor.

Languages

Tolkien devised two main Elven languages which would later become known to us as Quenya, spoken by the Vanyar, Noldor, and some Teleri, and Sindarin, spoken by the Elves who stayed in Beleriand (see below). These languages were related, and a Common Eldarin form ancestral to them both is postulated.

Other languages of the world include

Adûnaic – spoken by the Númenóreans

Black Speech – devised by Sauron for his slaves to speak

Khuzdûl – spoken by the Dwarves

Rohirric – spoken by the Rohirrim – represented in the Lord of the Rings by Old English

Westron – the 'Common Speech' – represented by English

Valarin – the language of the Ainur

History of Middle-earth

The history of Middle-earth is divided into three time periods, known as the Years of the Lamps, Years of the Trees and Years of the Sun; the latter is typically sub-divided further into four Ages, of which three are relevant to the printed works of the legendarium.

The Years of the Lamps began shortly after the Valar finished their labours in shaping Arda. The Valar created two lamps to illuminate the world, and the Vala Aulë forged great towers, one in the furthest north, Helcar with the lamp Illuin, and another in the deepest south, Ringil with the lamp Ormal. The Valar lived in the middle, at the island of Almaren. Melkor's destruction of the two Lamps marked the end of the Years of the Lamps.

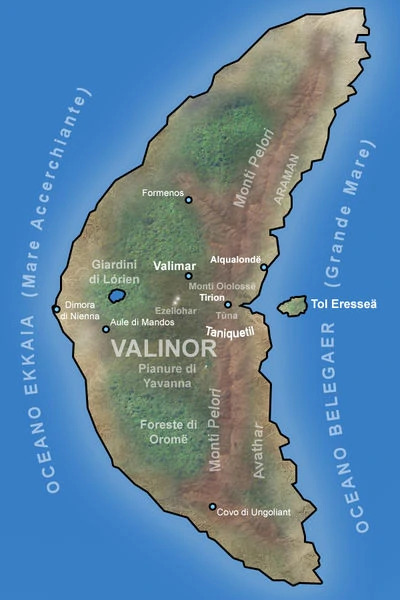

A speculative map of Aman in the Second Age

Then Yavanna made the Two Trees named Telperion and Laurelin in the land of Aman. The Trees illuminated Aman, leaving the rest of Arda in darkness, illuminated only by the stars. At the start of the First Age the Elves awoke beside Lake Cuiviénen in the east of Endor, and were soon approached by the Valar. Many of the elves were persuaded to undertake the Great Journey westwards towards Aman, but not all of them completed the journey (see Sundering of the Elves). The Valar had imprisoned Melkor but he appeared to repent and was released on parole. He sowed great discord among the Elves and stirred up rivalry between the Elven princes Fëanor and Fingolfin. He then slew their father, king Finwë and stole the Silmarils, three gems crafted by Fëanor that contained light of the Two Trees, from his vault, and destroyed the Trees themselves.

Fëanor persuaded most of his people, the Noldor, to leave Aman in pursuit of Melkor to Beleriand, cursing him with the name Morgoth. Fëanor led the first of two groups of Noldor. The larger group was led by Fingolfin. The Noldor stopped at the Teleri's port-city, Alqualondë, but the Teleri refused to give them ships to get to Middle-earth. The first Kinslaying thus ensued; Fëanor and many of his followers attacked the Teleri and stole their ships. Fëanor's host sailed on the stolen ships, leaving Fingolfin's behind to cross over to Middle-earth through the deadly Helcaraxë (or Grinding Ice) in the far north. Subsequently Fëanor was slain, but most of his sons survived and founded realms, as did Fingolfin and his heirs.

The Years of the Sun began when the Valar made the Sun and it rose over the world, Imbar. After several great battles, a long peace ensued for four hundred years, during which time the first Men entered Beleriand by crossing over the Blue Mountains. When Morgoth broke the siege of Angband, one by one the Elven kingdoms fell, even the hidden city of Gondolin. The only measurable success achieved by Elves and Men came when Beren of the Edain and Luthien, daughter of Thingol and Melian, retrieved a Silmaril from the crown of Morgoth. Afterward, Beren and Luthien died, and were restored to life by the Valar with the understanding that Luthien was to become mortal and Beren should never be seen by Men again.

Thingol quarrelled with the Dwarves of Nogrod and they slew him, stealing the Silmaril. With the help of Ents, Beren waylaid the Dwarves and recovered the Silmaril, which he gave to Luthien. Soon afterwards, both Beren and Luthien died again. The Silmaril was given to their son Dior Half-Elven, who had restored the Kingdom of Doriath. The sons of Fëanor demanded that Dior surrender the Silmaril to them, and he refused. The Fëanorians destroyed Doriath and killed Dior in the second Kinslaying, but Dior's young daughter Elwing escaped with the jewel. Three sons of Fëanor – Celegorm, Curufin, and Caranthir – died trying to retake the jewel.

By the end of the age, all that remained of the free Elves and Men in Beleriand was a settlement at the mouth of the River Sirion. Among them was Eärendil, who married Elwing. But the Fëanorians again demanded the Silmaril be returned to them, and after their demand was rejected they resolved to take the jewel by force, leading to the third Kinslaying. Eärendil and Elwing took the Silmaril across the Great Sea, to beg the Valar for pardon and aid. The Valar responded. Melkor was captured, most of his works were destroyed, and he was banished beyond the confines of the world into the Door of Night.

The Silmarils were recovered at a terrible cost, as Beleriand itself was broken and began to sink under the sea. Feanor's last remaining sons, Maedhros and Maglor, were ordered to return to Valinor. They proceeded to steal the Silmarils from the victorious Valar. But, as with Melkor, the Silmarils burned their hands and they then realized they were not meant to possess them and that the oath was null. Each of the brothers met his fate: Maedhros threw himself with the Silmaril into a chasm of fire, and Maglor threw his Silmaril into the sea. Thus the three Silmarils ended in the sky with Eärendil, in the earth, and in the sea respectively.

Thus began the Second Age. The Edain were given the island of Númenor toward the west of the Great Sea as their home, while many elves were welcomed into the West. The Númenóreans became great seafarers, but also became increasingly jealous of the elves for their immortality. But after a few centuries, Sauron, Morgoth's chief servant, began to organize evil creatures in the eastern lands. He persuaded Elven smiths in Eregion to create Rings of Power, and secretly forged the One Ring to control the other rings. But the elves became aware of Sauron's plan as soon as he put the One Ring on his hand, and they removed their own Rings before he could master their wills.

A map of Númenor during the Second Age, courtesy of the Encyclopedia of Arda.

The last Númenórean king Ar-Pharazôn, by the strength of his army, humbled even Sauron and brought him to Númenor as a hostage. But with the help of the One Ring, Sauron deceived Ar-Pharazôn and convinced the king to invade Aman, promising immortality for all those who set foot on the Undying Lands. Amandil, chief of those still faithful to the Valar, tried to sail west to seek their aid. His son Elendil and grandsons Isildur and Anárion prepared to flee east to Middle-earth. When the King's forces landed on Aman, the Valar called for Ilúvatar to intervene. The world was changed, and Aman was removed from Imbar. From that time onward, Men could no longer find Aman, but Elves seeking passage in specially hallowed ships received the grace of using the Straight Road, which led from Middle-earth's seas to the seas of Aman. Númenor was utterly destroyed, and with it the fair body of Sauron, but his spirit endured and fled back to Middle-earth. Elendil and his sons escaped to Endor and founded the realms of Gondor and Arnor. Sauron soon rose again, but the elves allied with the men to form the Last Alliance and defeated him. His One Ring was taken from him by Isildur, but not destroyed.

Middle-earth during the Third Age

The Third Age saw the rise in power of the realms of Arnor and Gondor, and their decline. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, Sauron had recovered much of his former strength, and was seeking the One Ring. He discovered that it was in the possession of a Hobbit and sent out the nine Ringwraiths to retrieve it. The Ring-bearer, Frodo Baggins, travelled to Rivendell, where it was decided that the Ring had to be destroyed in the only way possible: casting it into the fires of Mount Doom. Frodo set out on the quest with eight companions—the Fellowship of the Ring. At the last moment he failed, but with the intervention of the creature Gollum—who was saved by the pity of Frodo and Bilbo Baggins—the Ring was nevertheless destroyed. Frodo with his companion Sam Gamgee were hailed as heroes. Sauron was destroyed forever and his spirit dissipated.

The end of the Third Age marked the end of the dominion of the elves and the beginning of the dominion of men. As the Fourth Age began, many of the elves who had lingered in Middle-earth left for Valinor, never to return; those who remained behind would "fade" and diminish. The dwarves eventually dwindled away as well. The dwarves eventually returned in large numbers and resettled Moria. Peace was restored between Gondor and the lands to the south and east. Eventually, the tales of the earlier Ages became legends, the truth behind them forgotten.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Средизе́мье (англ. Middle-earth; синд.Ennorath; кв.Endore), буквально Среди́нная земля́, также существуют варианты перевода Среднеземье, Средьземелье) – континент в Арде. Часто этим словом обозначают всю Вымышленную вселенную Дж. Р. Р. Толкина. В самих же книгах Средиземьем называется восточная часть Арды, земли смертных, в противоположность Бессмертным Землям Амана.

Место в Арде

Название

Middle-earth – буквальный перевод на современный язык среднеанглийского middel-erde, произошедшего от староанглийского слова middangeard, которым назывался реальный, обитаемый людьми мир, находящийся посередине между небесами и преисподней.

На языке квенья Средиземье называлось Эндор, «срединная земля», на синдарине это же название звучало как Эннор. В различные эпохи именовалось также Покинутыми Землями, Внешними Землями, Великими Землями.

География

Средиземье представляет собой обширный континент с продолжительной береговой линией на западе, постепенно уходящей к юго-востоку.

Эпоха Светильников

После Первой Войны Валар упорядочили земли Арды и создали для роста растений Великие Светильники, установив их на юге и севере Средиземья. Свет светильников сливался на острове Алмарен, подле великого озера, где Валар и основали свою первую обитель. Вскоре в Арду вернулся Мелькор и возвёл на севере Средиземья свою первую цитадель, Утумно, а также прикрытие в виде Железных гор (с востока на запад). Они ограждали земли вечного холода на дальнем севере. Мелькор стал распространять своё влияние в Средиземье: зелень жухла и гнила, возникли ядовитые болота, леса стали тёмными, а звери превратились в чудовищ. Валар начали искать Мелькора, но он опередил их, разрушив Светильники, что вызвало катаклизмы. Симметрия вод и земель Средиземья была искажена, и первоначальный замысел Валар был нарушен. В результате падения Светильников возникли моря Хелкар и Рингиль, а Алмарен был уничтожен.

Эпоха Древ

После гибели Алмарена и Светильников Валар переселились на континент Аман, оставив Средиземье Мелькору. В те годы Мелькор возвёл на западе Железных гор крепость Ангбанд, на случай нападения из Валинора. Также Мелькор поднял Мглистые горы на огромную высоту. Вскоре у Куивиэнена, залива моря Хелкар, пробудились эльфы, и Валар начали войну за них с Мелькором. В результате Средиземье подверглось сильным разрушениям: северные земли превратились в пустыню, а море Рингиль расширилось на восток и запад, отделив часть восточных земель (они стали отдельным континентом, известным как Тёмные Земли). Море Белегаэр затопило западные берега Средиземья, основав Великий залив и залив Балар. Также возникли новые горы и нагорья в землях северо-западного Средиземья (Белерианда): Эред Ломин, Эред Ветрин и нагорья Дортониона.

Первая Эпоха

В конце Первой Эпохи произошла Война Гнева, последние сражения с Мелькором, которое вызвало сильные разрушения и изменения в Средиземье. Белерианд был разрушен и ушёл под воды Белегаэра, оставив лишь часть земель Оссирианда (названную Линдоном). Также остались некоторые возвышенности, ставшие островами: Химринг, Тол Фуин и Тол Морвен. Великий залив и море Хелкар (с Куивиэненом) перестали существовать. К северу от Линдона образовался залив Форохел, к юго-западу залив Лун, а на юге – залив Белфалас.

Королевства в Средиземье

Эпоха Древ

Эгладор – королевство эльфов-синдар в Белерианде, с 1497 Э. Д. ставшее Дориатом. Существовало с 1152 Э. Д. до 509 П. Э.

Фалас – королевство эльфов-синдар в Белерианде, находившееся в вассалитете Дориата. Существовало с 1149 Э. Д. по 473 П. Э.

Оссирианд – королевство эльфов-лаиквенди в Белерианде. Существовало с 1350 Э. Д. в 1497 Э. Д.

Дор-Даэделот – королевство Тёмного Властелина Моргота (Мелькора) в землях к северу от Белерианда и Хитлума. Существовало с 1497 Э. Д. до 590 П. Э.

Ногрод – королевство гномов из кланов Огнебородов и Широкозадов в горах Эред Луин. Существовало с ? Э. Д. до 590 П. Э.

Белегост – королевство гномов из кланов Огнебородов и Широкозадов в горах Эред Луин. Существовало с ? Э. Д. до 590 П. Э.

Казад-Дум – королевство гномов-Долгобородов под Мглистыми горами. Существовало с ? Э. Д. до 1981 Т. Э.

Первая Эпоха

Предел Маэдроса – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Феанора. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 472 П. Э.

Земля Маглора – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Феанора. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 455 П. Э.

Химлад – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Феанора. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 455 П. Э.

Дор Карантир – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Феанора. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 455 П. Э.

Хитлум – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финголфина. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 472 П. Э.

Невраст – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финголфина. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 416 П. Э.

Гондолин – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финголфина. Существовало с 416 П. Э. до 510 П. Э.

Дортонион – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финарфина. Существовало с 5 П. Э. до 455 П. Э.

Нарготронд – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финарфина. Существовало с 102 П. Э. до 495 П. Э.

Дор-ломин – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финголфина до 416 П. Э. С 416 королевство людей Дома Хадора в вассалитете Дома Финголфина. Существовало до 455 П. Э.

Ладрос – королевство людей Дома Беора в вассалитете Дома Финарфина. Существовало с 410 П. Э. до 455 П. Э.

Бретиль – королевство людей Дома Халет. Существовало с ~360 П. Э. по ? (конец П. Э.).

Вторая Эпоха

Форлиндон – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Финголфина. Существовало с 1 В. Э. до 3441 В. Э.

Эрегион – королевство эльфов-нолдор Дома Феанора. Существовало с 750 В. Э. до 1697 В. Э.

Харлиндон – королевство эльфов-синдар Иатрим. Существовало с 1 В. Э. до ~2000 В. Э.

Лориэн – королевство эльфов-галадрим. Существовало с ? (начало В. Э.) до ? (начало Ч.Э.).

Зеленолесье – королевство лесных эльфов. Существовало с ? (начало В. Э.).

Гондор – королевство людей-дунэдайн юга. Существовало с 3320 В. Э.

Арнор – королевство людей-дунэдайн севера. Существовало с 3320 В. Э. до 861 Т. Э.

Мордор – королевство Тёмного Властелина Саурона. Существовало с ~1000 В. Э. по 3441 В. Э.

Третья Эпоха

Артэдайн – королевство людей-дунэдайн севера. Существовало с 861 Т. Э. по 1974 Т. Э.

Рудаур – королевство людей-дунэдайн севера. Существовало с 861 Т. Э. по 1409 Т. Э.

Кардолан – королевство людей-дунэдайн севера. Существовало с 861 Т. Э. по 1409 Т. Э.

Рохан – королевство людей-северян. Существовало с 2510 Т. Э.

Дэйл – королевство людей-северян. Существовало ~1800 Т. Э. до 2770 Т. Э. Было восстановлено в 2941 Т. Э.

Шир – владения людей-хоббитов в вассалитете Артэдайна (до его гибели). Существовал с 1601 Т. Э.

Эребор – королевство гномов Долгобородов. Существовало с 1999 Т. Э. до 2770 Т. Э. Было восстановлено в 2941 Т. Э.

Серые горы – королевство гномов Долгобородов. Существовало с 2210 Т. Э. до 2589 Т. Э.

Железные Холмы – королевство гномов Долгобородов. Существовало с 2590 Т. Э.

Ангмар – королевство слуги Саурона, Короля-Чародея. Существовало с 1300 Т. Э. по 1975 Т. Э.

Мордор – вновь восстановленное королевство Саурона. Существовало с 2942 Т. Э. по 3019 Т. Э.

Другие королевства

Королевства харадрим – королевства людей-харадрим в южных и юго-восточных землях Средиземья, Хараде.

Королевства истерлингов – королевства людей истерлингов в восточных землях Средиземья, к востоку от Руна.

Кханд – ��оролевство людей-вариагов к востоку от Мордора.

#middle-earth#lord of the rings#the hobbit#silmarillion#lotr#средиземье#властелин колец#хоббит#силмариллион

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

The end of Ungoliant

The fate of Ungoliant as described in The Silmarillion is very vague.

After her quarrel with Morgoth over the Silmaril Ungoliant first wandered into Beleriand, but later on she went south and what happend there is unknown.

But there is a theory:

“But whither she went after no tale tells. It is said that she ended long ago, when in her uttermost famine she devoured herself at last.”¹

I believe that was the last thing Tolkien wrote regarding the fate of Ungoliant, with the Later Quenta dating around the late 50s. It is also the version that can be found in The Silmarillion and probably the closest to canon that you can get, so there is probably no need to write about it any further.

However, another idea can be found in Tolkien’s earlier writings, and I think that’s a very interesting version.

Ungoliant by Paul Raymond Gregory

In The Book of Lost Tales Ungoliant also goes south “to her home” after her confrontation with Melkor. In a paragraph about the journey of the sun the reason for it going from East to West is that Morgoth is in the North, and Ungoliant in the South:

“Now Manwë designed the course of the ship of light to be between the East and West, for Melko held the North and Ungweliant the South, whereas in the West was Valinor and the blessed realms, and in the East great regions of dark lands that craved for light.”²

This sets her in direct opposition to Morgoth and gives an image of two great dark beings troubling Middle-earth, independently from each other.

Later, Ungoliant is mentioned in relation to Eärendil, implying that he met her on his journeys. In The Book of Lost Tales this isn’t described any further, but in the Sketch of Mythology we can find the following:

“Here follow the marvellous adventures of Wingelot in the seas and isles, and of how Earendel slew Ungoliant in the South.”³

And in the Quenta Nolderinwa this idea reappears as well:

“In the Lay of Eärendel is many a thing sung of his adventures in the deep and in lands untrod, and in many seas and many isles; and most of how he fought and slew Ungoliant in the South and her darkness perished, and light came to many places which had yet long been hid.”⁴

Or in the revised version:

“In the Lay of Eärendel is many a thing sung of his adventures in the deep and in lands untrodden, and in many seas and many isles. Ungoliant in the South he slew, and her darkness was destroyed, and light came to many regions which had yet long been hid.”⁵

In the Later Annals of Beleriand this was also mentioned in an addition to the text.

But that is the last time this version appears. In the Annals of Aman she returned into the South of the world, “where she abides yet for all that the Eldar have heard”⁶ and afterwards in the Later Quenta the version of Ungoliant devouring herself is added to the paragraph of her going south (see first quote).

Tolkien never wrote about Eärendil’s journeys and adventures, he only wrote brief outlines. I think this is very regrettable – I believe it would have been a fascinating Middle-earth version of the Odyssey.

It might be that even if he had written about it in his later years he would not have included Eärendil slaying Ungoliant – it was probably difficult to explain how someone like Eärendil would be able to kill Ungoliant if even Morgoth had such difficulties in dealing with her. But I don’t think it would be impossible - for all we know she could have been half-starved when Eärendil finally reached her. Eärendil killing her on his journeys before he reached Valinor would also mean that she was already dead at the time of Morgoth's downfall.

The version in the Annals of Aman and the Later Quenta are short and vague enough that there is enough room to imagine that Ungoliant was indeed killed by Eärendil on his great voyage. Ungoliant devouring herself is a fitting end for her and definitively works well within the story, but I think the earlier version of her end would make a better tale. I prefer it, especially because we barely get any information about anything else that Eärendil experienced on his voyage.

Footnotes

¹ J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien. Morgoth's Ring, Part 3: The Later Quenta Silmarillion, II: The Second Phase, Of the Thieves' Quarrel, §20

² J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien. The Book of Lost Tales - Part 1, VIII The Tale of the Sund and Moon

³ J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien. The Shaping of Middle-earth, II: The Earliest 'Silmarilllion', §17

⁴ J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien. The Shaping of Middle-earth, III: The Quenta, §17

⁵ J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien. The Shaping of Middle-earth, III: The Quenta, §17 (Q II)

⁶ J. R. R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien, Morgoth’s Ring, Part 2: The Annals of Aman, Section 5, §126

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

opinions on the book of lost tales?

It’s been ages since I picked up either volume, so I can’t quite remember everything in them, alas. I should remedy that one of these days.

HOWEVER, I remember Aelfwine and I like that whole idea, of this random Anglo-Saxon dude just rolling up to Eressea out of nowhere. I’m also kind of delighted that the name is recycled later for Eomer and Lothiriel’s son Elfwine.

I also remember in the original Tale of Tinuviel Beren is cast as a Noldo, and I’m very glad that that got changed later because Beren as a Mortal Man is so much more compelling to me.

And there’s an Earendel poem in volume 2 that I really love:

Éarendel sprang up from the Ocean's cupIn the gloom of the mid-world's rim;From the door of Night as a ray of lightLeapt over the twilight brim,And launching his bark like a silver sparkFrom the golden-fading sandDown the sunlit breath of Day's fiery DeathHe sped from Westerland.

He leaps and launches and speeds and it’s so dynamic and the imagery is beautiful and ahhhhh Tolkien is just so good at words.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been re-reading The Lost Road (which every Tolkien fan should get around to at least once, it’s fascinating), and one passage jumped out at me for the first time:

Mariners in the old days said that the scent of lavaralda could be felt on the air long ere the land of Eressea could be seen, and that it brought a desire of rest and great content. He had seen the trees in flower day after day, for they rested from flowering only at rare intervals. But now, suddenly, as he passed, the scent struck him with a keen fragrance, at once known and utterly strange. He seemed for a moment never to have smelled it before: it pierced the troubles of his mind, bewildering, bringing no familiar content, but a new disquiet.

'Eressea, Eressea!' he said. 'I wish I were there; and had not been fated to dwell in Numenor' half-way between the worlds. And least of all in these days of perplexity! '

This is Elendil speaking, but not quite the Elendil of the Silmarillion. The story follows a father and his son as they’re continuously reincarnated. In the first chapter, the father’s an Oxford professor named Alboin Errol with a deep, life-long interest in Old English (Christ Tolkien confirms that it’s largely autobiographical). In the second, he’s a Númenorean prince during the Akallabêth; in the third, an Anglo-Saxon traveller called Aelfwine, in Sindarin Eriol.

The association between Aelfwine and Elendil as characters is interesting in itself, and it’s particularly poignant here. He won’t make it to Eressea in this lifetime. When Aelfwine - the more developed version of the character - does get to Eressea, it’s as an exile himself. We learn in The Notion Club Papers (from yet another Tolkien self-insert) that he spent is childhood as a refugee after the Danish invasion of Somerset, and that his journey west was motivated by another series of Danish attacks.

What struck me here is how The Lost Road turns the story of Númenor - not the fall, but the empire itself, at the height of its glory - into an exile narrative. The first Númenoreans were taken from their homes in Beleriand, granted superhuman physical and mental gifts, and then told not to leave. That’s their tragedy. The qualities that make Eärendil so admirable are the same ones that slowly destroy his descendants. They’re brave, curious, never content to stagnate, always eager and open to the world. They’re explorers.

And it goes wrong every time. Tar-Aldarion’s wanderlust wrecks his family. The Númenorean mania for ship-building leads to ecological collapse at home; what starts out as military aid to Lindon ends in centuries of violent colonial expansion. It’s true that Númenor is blessed, but those blessing flow strictly from west to east. And since the west is closed off to them, all that desire for knowledge and beauty and wonder gets stymied and twisted and shunted back off to Middle-earth.

Of course, they can’t go home again. Beleriand is gone. The land different, and they’re different too. The Númenoreans are, in very real ways, more than human. At the same time, they’re less than elves. Naturally, they start to fight wars of conquest. How else are they going to find a place in the world? They’re exiles in their own bodies.

It’s not surprising that The Lost Road contains what is probably Tolkien’s most sympathetic articulating of the viewpoint of the King’s Men:

'They say now that the tale was altered by the Eresseans, who are slaves of the Lords: that in truth Earendel was an adventurer, and showed us the way, and that the Lords took him captive for that reason; and his work is perforce unfinished. Therefore the son of Earendel, our king, should complete it. They wish to do what has been long left undone.'

'What is that?'

'Thou knowest: to set foot in the far West, and not withdraw it.

To conquer new realms for our race, and ease the pressure of this peopled island, where every road is trodden hard, and every tree and grass-blade counted. To be free, and masters of the world. To escape the shadow of sameness, and of ending. We would make our king Lord of the West: Nuaran Númenoren. Death comes here slow and seldom; yet it cometh. The land is only a cage gilded to look like Paradise.'

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

@vardasvapors this image and your commentary makes me so excited…

I’ve been thinking about the choices of Elrond and Elros in that they both have their adventures. Elrond adventures through Middle-earth, learning about many places and peoples and discovering many wild and strange things, and then 1700 years later he establishes the Last Homely House and settles down for more responsibility. Elros takes on lots of responsibility at 90, leading his chosen people to build a civilization on the Land of Gift and settling down there for the rest of his life, and then he goes beyond for his great adventure in the next world. I think about your comment on infinity and feel like both their adventures can be described as their pursuits of infinity — the infinite space and time inside and outside. There are limits, of course, Elrond gets infinite time in one space but is limited by inhabiting only this one space, while Elros is limited by his time in this one space with Elrond but gets infinite time in another space. With his limited time in this world, Elros leaves his legacy — his marks on the world, and Elrond helps preserve this legacy by tracking these marks through close relationships with his brother’s descendants. In this way, like what you said elsewhere, Elrond immortalizes the mortals, giving a kind of infinity to their limits. But when the world ends and his infinity reaches its limit, it needs to be restored by those without this limit.

Now I haven’t talk about the sea and boat imagery yet:

Tûr bids farewell to Eärendel and bids him thrust it off – the skiff fares away into the West. Eärendel hears a great song swelling from the sea as Tûr’s skiff dips over the world’s rim.

You connected Elros bidding farewell to Elrond to Tûr bidding farewell to Eärendel. I like this comparison a lot! Both farewells involve one watching the other voyage on to the beyond. I wonder how do mortal spirits depart Mandos? I like to envision spirits being sent out on spirit-boats that sail out to Ekkaia toward the Walls of Night and dip over the edge, like a boat sailing out to the West dips over the horizon. I think in this way these two farewells really evoke similar kinds of imagery, just like the art! I also kind of understand what you said about Eärendel. He searches for Mandos by paths of the sea, following Tûr’s voyage to go where he goes. I think this idea is partially kept in The Silmarillion, in that they both sail to the West, Eärendil after Tuor, and come never back to Middle-earth. If we consider the presumption that Tuor is granted immortality, they both leave one place but gets infinity in another place. What you said about the Dúnedain’s water burials after the Change of the World is also fascinating! It is as if they try to find Ekkaia through the Straight Road to Aman, turning the spiritual journey physical — the voyage over water to the infinite unknown.

#elros#elrond#life and death of stars#dunedain#the silmarillion#tuor#earendil#the tale of earendel#the book of lost tales

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

at some point i should really get back to my hobby of posting obscure cool passages of jirt brainstorming from all the volumes of the histories of middle earth, not JUST the tale of earendel

#j r r tolkien#the tale of earendel#<- for ref in case u wanna trawl breathtaking haunting half-lost backformationed folklore and tuor's ulmo kink

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tolkien

Who Was Tolkien?

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (1892–1973) was a major scholar of the English language, specialising in Old and Middle English. Twice Professor of Anglo-Saxon (Old English) at the University of Oxford, he also wrote a number of stories, including most famously The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955), which are set in a pre-historic era in an invented version of our world which he called by the Middle English name of Middle-earth. This was peopled by Men (and women), Elves, Dwarves, Trolls, Orcs (or Goblins) and of course Hobbits. He has regularly been condemned by the Eng. Lit. establishment, with honourable exceptions, but loved by literally millions of readers worldwide.

Childhood and Youth

The name “Tolkien” was believed by the family to be of German origin; Toll-kühn: foolishly brave, or stupidly clever—hence the pseudonym “Oxymore” which he occasionally used; however, this quite probably was a German rationalisation of an originally Baltic Tolkyn, or Tolkīn. In any case, his great-great grandfather John (Johann) Benjamin Tolkien came to Britain with his brother Daniel from Gdańsk in about 1772 and rapidly became thoroughly Anglicised. Certainly his father, Arthur Reuel Tolkien, considered himself nothing if not English. Arthur was a bank clerk, and went to South Africa in the 1890s for better prospects of promotion. There he was joined by his bride, Mabel Suffield, whose family were not only English through and through, but West Midlands since time immemorial. So John Ronald (“Ronald” to family and early friends) was born in Bloemfontein, S.A., on 3 January 1892. His memories of Africa were slight but vivid, including a scary encounter with a large hairy spider, and influenced his later writing to some extent; slight, because on 15 February 1896 his father died, and he, his mother and his younger brother Hilary returned to England—or more particularly, the West Midlands.

The West Midlands in Tolkien’s childhood were a complex mixture of the grimly industrial Birmingham conurbation, and the quintessentially rural stereotype of England, Worcestershire and surrounding areas: Severn country, the land of the composers Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Gurney, and more distantly the poet A. E. Housman (it is also just across the border from Wales). Tolkien’s life was split between these two: the then very rural hamlet of Sarehole, with its mill, just south of Birmingham; and darkly urban Birmingham itself, where he was eventually sent to King Edward’s School. By then the family had moved to King’s Heath, where the house backed onto a railway line—young Ronald’s developing linguistic imagination was engaged by the sight of coal trucks going to and from South Wales bearing destinations like” Nantyglo”,” Penrhiwceiber” and “Senghenydd”.

Then they moved to the somewhat more pleasant Birmingham suburb of Edgbaston. However, in the meantime, something of profound significance had occurred, which estranged Mabel and her children from both sides of the family: in 1900, together with her sister May, she was received into the Roman Catholic Church. From then on, both Ronald and Hilary were brought up in the faith of Pio Nono, and remained devout Catholics throughout their lives. The parish priest who visited the family regularly was the half-Spanish half-Welsh Father Francis Morgan.

Tolkien family life was generally lived on the genteel side of poverty. However, the situation worsened in 1904, when Mabel Tolkien was diagnosed as having diabetes, usually fatal in those pre-insulin days. She died on 14 November of that year leaving the two orphaned boys effectively destitute. At this point Father Francis took over, and made sure of the boys’ material as well as spiritual welfare, although in the short term they were boarded with an unsympathetic aunt-by-marriage, Beatrice Suffield, and then with a Mrs Faulkner.

By this time Ronald was already showing remarkable linguistic gifts. He had mastered the Latin and Greek which was the staple fare of an arts education at that time, and was becoming more than competent in a number of other languages, both modern and ancient, notably Gothic, and later Finnish. He was already busy making up his own languages, purely for fun. He had also made a number of close friends at King Edward’s; in his later years at school they met regularly after hours as the “T. C. B. S.” (Tea Club, Barrovian Society, named after their meeting place at the Barrow Stores) and they continued to correspond closely and exchange and criticise each other’s literary work until 1916.

However, another complication had arisen. Amongst the lodgers at Mrs Faulkner’s boarding house was a young woman called Edith Bratt. When Ronald was 16, and she 19, they struck up a friendship, which gradually deepened. Eventually Father Francis took a hand, and forbade Ronald to see or even correspond with Edith for three years, until he was 21. Ronald stoically obeyed this injunction to the letter. In the summer of 1911, he was invited to join a party on a walking holiday in Switzerland, which may have inspired his descriptions of the Misty Mountains, and of Rivendell. In the autumn of that year he went up to Exeter College, Oxford where he stayed, immersing himself in the Classics, Old English, the Germanic languages (especially Gothic), Welsh and Finnish, until 1913, when he swiftly though not without difficulty picked up the threads of his relationship with Edith. He then obtained a disappointing second class degree in Honour Moderations, the “midway” stage of a 4-year Oxford “Greats” (i.e. Classics) course, although with an “alpha plus” in philology. As a result of this he changed his school from Classics to the more congenial English Language and Literature. One of the poems he discovered in the course of his Old English studies was the Crist of Cynewulf—he was amazed especially by the cryptic couplet:

Eálá Earendel engla beorhtast

Ofer middangeard monnum sended

Which translates as:

Hail Earendel brightest of angels,

over Middle Earth sent to men.

(“Middangeard” was an ancient expression for the everyday world between Heaven above and Hell below.)

This inspired some of his very early and incohate attempts at realising a world of ancient beauty in his versifying.

In the summer of 1913 he took a job as tutor and escort to two Mexican boys in Dinard, France, a job which ended in tragedy. Though no fault of Ronald’s, it did nothing to counter his apparent predisposition against France and things French.

Meanwhile the relationship with Edith was going more smoothly. She converted to Catholicism and moved to Warwick, which with its spectacular castle and beautiful surrounding countryside made a great impression on Ronald. However, as the pair were becoming ever closer, the nations were striving ever more furiously together, and war eventually broke out in August 1914.

War, Lost Tales and Academia

Unlike so many of his contemporaries, Tolkien did not rush to join up immediately on the outbreak of war, but returned to Oxford, where he worked hard and finally achieved a first-class degree in June 1915. At this time he was also working on various poetic attempts, and on his invented languages, especially one that he came to call Qenya [sic], which was heavily influenced by Finnish—but he still felt the lack of a connecting thread to bring his vivid but disparate imaginings together. Tolkien finally enlisted as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers whilst working on ideas of Earendel [sic] the Mariner, who became a star, and his journeyings. For many months Tolkien was kept in boring suspense in England, mainly in Staffordshire. Finally it appeared that he must soon embark for France, and he and Edith married in Warwick on 22 March 1916.

Eventually he was indeed sent to active duty on the Western Front, just in time for the Somme offensive. After four months in and out of the trenches, he succumbed to “trench fever”, a form of typhus-like infection common in the insanitary conditions, and in early November was sent back to England, where he spent the next month in hospital in Birmingham. By Christmas he had recovered sufficiently to stay with Edith at Great Haywood in Staffordshire.

During these last few months, all but one of his close friends of the “T. C. B. S.” had been killed in action. Partly as an act of piety to their memory, but also stirred by reaction against his war experiences, he had already begun to put his stories into shape, “… in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire” [Letters 66]. This ordering of his imagination developed into the Book of Lost Tales (not published in his lifetime), in which most of the major stories of the Silmarillion appear in their first form: tales of the Elves and the “Gnomes”, (i. e. Deep Elves, the later Noldor), with their languages Qenya and Goldogrin. Here are found the first recorded versions of the wars against Morgoth, the siege and fall of Gondolin and Nargothrond, and the tales of Túrin and of Beren and Lúthien.

Throughout 1917 and 1918 his illness kept recurring, although periods of remission enabled him to do home service at various camps sufficiently well to be promoted to lieutenant. It was when he was stationed in the Hull area that he and Edith went walking in the woods at nearby Roos, and there in a grove thick with hemlock Edith danced for him. This was the inspiration for the tale of Beren and Lúthien, a recurrent theme in his “Legendarium”. He came to think of Edith as “Lúthien” and himself as “Beren”. Their first son, John Francis Reuel (later Father John Tolkien) had already been born on 16 November 1917.

When the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, Tolkien had already been putting out feelers to obtain academic employment, and by the time he was demobilised he had been appointed Assistant Lexicographer on the New English Dictionary (the “Oxford English Dictionary”), then in preparation. While doing the serious philological work involved in this, he also gave one of his Lost Tales its first public airing—he read The Fall of Gondolin to the Exeter College Essay Club, where it was well received by an audience which included Neville Coghill and Hugo Dyson, two future “Inklings”. However, Tolkien did not stay in this job for long. In the summer of 1920 he applied for the quite senior post of Reader (approximately, Associate Professor) in English Language at the University of Leeds, and to his surprise was appointed.

At Leeds as well as teaching he collaborated with E. V. Gordon on the famous edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and continued writing and refining The Book of Lost Tales and his invented “Elvish” languages. In addition, he and Gordon founded a “Viking Club” for undergraduates devoted mainly to reading Old Norse sagas and drinking beer. It was for this club that he and Gordon originally wrote their Songs for the Philologists, a mixture of traditional songs and original verses translated into Old English, Old Norse and Gothic to fit traditional English tunes. Leeds also saw the birth of two more sons: Michael Hilary Reuel in October 1920, and Christopher Reuel in 1924. Then in 1925 the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford fell vacant; Tolkien successfully applied for the post.

Professor Tolkien, The Inklings and Hobbits

In a sense, in returning to Oxford as a Professor, Tolkien had come home. Although he had few illusions about the academic life as a haven of unworldly scholarship (see for example Letters 250), he was nevertheless by temperament a don’s don, and fitted extremely well into the largely male world of teaching, research, the comradely exchange of ideas and occasional publication. In fact, his academic publication record is very sparse, something that would have been frowned upon in these days of quantitative personnel evaluation.

However, his rare scholarly publications were often extremely influential, most notably his lecture “Beowulf, the Monsters and the Critics”. His seemingly almost throwaway comments have sometimes helped to transform the understanding of a particular field—for example, in his essay on “English and Welsh”, with its explanation of the origins of the term “Welsh” and its references to phonaesthetics (both these pieces are collected in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, currently in print). His academic life was otherwise largely unremarkable. In 1945 he changed his chair to the Merton Professorship of English Language and Literature, which he retained until his retirement in 1959. Apart from all the above, he taught undergraduates, and played an important but unexceptional part in academic politics and administration.

His family life was equally straightforward. Edith bore their last child and only daughter, Priscilla, in 1929. Tolkien got into the habit of writing the children annual illustrated letters as if from Santa Claus, and a selection of these was published in 1976 as The Father Christmas Letters. He also told them numerous bedtime stories, of which more anon. In adulthood John entered the priesthood, Michael and Christopher both saw war service in the Royal Air Force. Afterwards Michael became a schoolmaster and Christopher a university lecturer, and Priscilla became a social worker. They lived quietly in North Oxford, and later Ronald and Edith lived in the suburb of Headington.

However, Tolkien’s social life was far from unremarkable. He soon became one of the founder members of a loose grouping of Oxford friends (by no means all at the University) with similar interests, known as “The Inklings”. The origins of the name were purely facetious—it had to do with writing, and sounded mildly Anglo-Saxon; there was no evidence that members of the group claimed to have an “inkling” of the Divine Nature, as is sometimes suggested. Other prominent members included the above—mentioned Messrs Coghill and Dyson, as well as Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, and above all C. S. Lewis, who became one of Tolkien’s closest friends, and for whose return to Christianity Tolkien was at least partly responsible. The Inklings regularly met for conversation, drink, and frequent reading from their work-in-progress.

The Storyteller

Meanwhile Tolkien continued developing his mythology and languages. As mentioned above, he told his children stories, some of which he developed into those published posthumously as Mr. Bliss, Roverandom, etc. However, according to his own account, one day when he was engaged in the soul-destroying task of marking examination papers, he discovered that one candidate had left one page of an answer-book blank. On this page, moved by who knows what anarchic daemon, he wrote “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit“.

In typical Tolkien fashion, he then decided he needed to find out what a Hobbit was, what sort of a hole it lived in, why it lived in a hole, etc. From this investigation grew a tale that he told to his younger children, and even passed round. In 1936 an incomplete typescript of it came into the hands of Susan Dagnall, an employee of the publishing firm of George Allen and Unwin (merged in 1990 with HarperCollins).

She asked Tolkien to finish it, and presented the complete story to Stanley Unwin, the then Chairman of the firm. He tried it out on his 10-year old son Rayner, who wrote an approving report, and it was published as The Hobbit in 1937. It immediately scored a success, and has not been out of children’s recommended reading lists ever since. It was so successful that Stanley Unwin asked if he had any more similar material available for publication.

By this time Tolkien had begun to make his Legendarium into what he believed to be a more presentable state, and as he later noted, hints of it had already made their way into The Hobbit. He was now calling the full account Quenta Silmarillion, or Silmarillion for short. He presented some of his “completed” tales to Unwin, who sent them to his reader. The reader’s reaction was mixed: dislike of the poetry and praise for the prose (the material was the story of Beren and Lúthien) but the overall decision at the time was that these were not commercially publishable. Unwin tactfully relayed this message to Tolkien, but asked him again if he was willing to write a sequel to The Hobbit. Tolkien was disappointed at the apparent failure of The Silmarillion, but agreed to take up the challenge of “The New Hobbit”.

This soon developed into something much more than a children’s story; for the highly complex 16-year history of what became The Lord of the Rings consult the works listed below. Suffice it to say that the now adult Rayner Unwin was deeply involved in the later stages of this opus, dealing magnificently with a dilatory and temperamental author who, at one stage, was offering the whole work to a commercial rival (which rapidly backed off when the scale and nature of the package became apparent). It is thanks to Rayner Unwin’s advocacy that we owe the fact that this book was published at all – Andave laituvalmes! His father’s firm decided to incur the probable loss of £1,000 for the succès d’estime, and publish it under the title of The Lord of the Rings in three parts during 1954 and 1955, with USA rights going to Houghton Mifflin. It soon became apparent that both author and publishers had greatly underestimated the work’s public appeal.

The “Cult”

The Lord of the Rings rapidly came to public notice. It had mixed reviews, ranging from the ecstatic (W. H. Auden, C. S. Lewis) to the damning (E. Wilson, E. Muir, P. Toynbee) and just about everything in between. The BBC put on a drastically condensed radio adaptation in 12 episodes on the Third Programme. In 1956 radio was still a dominant medium in Britain, and the Third Programme was the “intellectual” channel. So far from losing money, sales so exceeded the break-even point as to make Tolkien regret that he had not taken early retirement. However, this was still based only upon hardback sales.

The really amazing moment was when The Lord of the Rings went into a pirated paperback version in 1965. Firstly, this put the book into the impulse-buying category; and secondly, the publicity generated by the copyright dispute alerted millions of American readers to the existence of something outside their previous experience, but which appeared to speak to their condition. By 1968 The Lord of the Rings had almost become the Bible of the “Alternative Society”.

This development produced mixed feelings in the author. On the one hand, he was extremely flattered, and to his amazement, became rather rich. On the other, he could only deplore those whose idea of a great trip was to ingest The Lord of the Rings and LSD simultaneously. Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick had similar experiences with 2001: A Space Odyssey. Fans were causing increasing problems; both those who came to gawp at his house and those, especially from California who telephoned at 7 p.m. (their time—3 a.m. his), to demand to know whether Frodo had succeeded or failed in the Quest, what was the preterite of Quenyan lanta-, or whether or not Balrogs had wings. So he changed addresses, his telephone number went ex-directory, and eventually he and Edith moved to Bournemouth, a pleasant but uninspiring South Coast resort (Hardy’s “Sandbourne”), noted for the number of its elderly well-to-do residents.

Meanwhile the cult, not just of Tolkien, but of the fantasy literature that he had revived, if not actually inspired (to his dismay), was really taking off—but that is another story, to be told in another place.

Other Writings

Despite all the fuss over The Lord of the Rings, between 1925 and his death Tolkien did write and publish a number of other articles, including a range of scholarly essays, many reprinted in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays (see above); one Middle-earth related work, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil; editions and translations of Middle English works such as the Ancrene Wisse, Sir Gawain, Sir Orfeo and The Pearl, and some stories independent of the Legendarium, such as the Imram, The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun—and, especially, Farmer Giles of Ham, Leaf by Niggle, and Smith of Wootton Major.

The flow of publications was only temporarily slowed by Tolkien’s death. The long-awaited Silmarillion, edited by Christopher Tolkien, appeared in 1977. In 1980 Christopher also published a selection of his father’s incomplete writings from his later years under the title of Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth. In the introduction to this work Christopher Tolkien referred in passing to The Book of Lost Tales, “itself a very substantial work, of the utmost interest to one concerned with the origins of Middle-earth, but requiring to be presented in a lengthy and complex study, if at all” (Unfinished Tales, p. 6, paragraph 1).