#threepence

Note

Please draw more Charlie from TGYH, he needs more love

He’s thinking of what he’ll have for dinner

#thank goodness you're here#tgyh#tgyh charlie#quite the guy indeed#give him a threepence while you’re at it

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let Your Knights Weep

One of the big things I've had to train myself out of when writing medieval historical fiction?

The stiff upper lip.

This used to really bewilder my editor, who for some time attempted to nudge me away from having my grown men weep and wail and blubber, but for me it's an essential part of the setting. Whether in grief or fear, medieval people did not hold things back.

Here are some of my favourite quotes to explain.

First, a couple from two great 20th century medievalists:

CS Lewis in his Letters put it this way:

“By the way, don't 'weep inwardly' and get a sore throat. If you must weep, weep: a good honest howl! I suspect we - and especially, my sex - don't cry enough now-a-days. Aeneas and Hector and Beowulf, Roland and Lancelot blubbered like schoolgirls, so why shouldn't we?”

Dorothy Sayers, in her fabulous Introduction to her translation of THE SONG OF ROLAND, speaking of Charlemagne discovering Roland's body on the battlefield:

Here too, I think we must not reckon it weakness in him that he is overcome by grief for Roland’s death, that he faints upon the body and has to be raised up by the barons and supported by them while he utters his lament. There are fashions in sensibility as in everything else. The idea that a strong man should react to great personal and national calamities by a slight compression of the lips and by silently throwing his cigarette into the fireplace is of very recent origin. By the standards of feudal epic, Charlemagne’s behaviour is perfectly correct. Fainting, weeping, and lamenting is what the situation calls for. The assembled knights and barons all decorously follow his example. They punctuate his lament with appropriate responses:

By hundred thousand the French for sorrow sigh;

There’s none of them but utters grievous cries.

At the end of the next laisse:

He tears his beard that is so white of hue,

Tears from his head his white hair by the roots;

And of the French an hundred thousand swoon.

We may take this response as being ritual and poetic; grief, like everything else in the Epic, is displayed on the heroic scale. Though men of the eleventh century did, in fact, display their emotions much more openly than we do, there is no reason to suppose that they made a practice of fainting away in chorus. But the gesture had their approval; that was how they liked to think of people behaving. In every age, art holds up to us the standard pattern of exemplary conduct, and real life does its best to conform. From Charlemagne’s weeping and fainting we can draw no conclusions about his character except that the poet has represented him as a perfect model of the “man of feeling” in the taste of the period.

OK, now let's dig into some quotes that I found just in Christopher Tyerman's Chronicles of the First Crusade and Joinville's Life of St Louis:

Truly you would have grieved and sobbed in pity when the Turks killed any of our men....

As for the knights, they stood about in a great state of gloom, wringing their hands because they were so frightened and miserable, not knowing what to do with themselves and their armour, and offering to sell their shields, valuable breastplates and helmets for threepence or fivepence or any price they could get....

When Guy, who was a very honourable knight, had heard these lies, he and all the others began to weep and to make loud lamentation....

They stayed in the houses cowering, some some for hunger and some for fear of the Turks....

Now at vigils, the time of trust in God’s compassion, many gave up hope and hurriedly lowered themselves with ropes from the wall-tops; and in the city soldiers, returning from the encounter, circulated widely a rumour that mass decapitation of the defenders was in store. To add weight to the terror, they too fled…

In the course of that day’s battle there had been many people, and of fine appearance too, who had come very shamefully flying over the little bridge you know of and had fled away so panic-stricken that all our attempts to make them stay with us had been in vain. I could tell you some of their names, but shall refrain from doing so, because they are now dead.

I could go on looking for quotes in all the other medieval literature I've read, but that would be beyond the scope of this Tumblr post.

In the meantime, this leads me to make some comments on how trauma was perceived.

In Jonathan Riley-Smith's The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading, the author discusses the mental breakdowns suffered by the first crusaders during the second siege of Antioch, which caused many of them to flee at the moment of direst need:

In these stressful circumstances it is not surprising that the crusaders were often very frightened. At times, indeed, they seem to have been almost paralysed by a terror that they themselves could hardly comprehend. … When the crusade was bottled up in Antioch by Kerbogha's relief force it was gripped by such blind panic that there was the prospect of a mass break-out and on the night of 10 or 11 Juney 1098 Bohemond and Adhemar had the gates of the city closed. It is worth noting that many of those whom later chroniclers, writing after the events in comparative comfort in Europe, vilified for cowardice and desertion seem to have been treated more charitably by their fellow-crusaders, who must have understood what pressures they had been under.

--

In conclusion: the way we feel about things today in the English-speaking isn't necessarily the way people felt about things in the past (and this goes for other cultures, real or imagined, too). I'm continually catching myself writing people with stiff upper lips and emotional reservations, and having to remind myself that the culture was different back them. If a grown man wanted to weep, he could. That's a good thing.

(Oh, and my medieval historical fantasy? Check out the Watchers of Outremer series on Amazon or wherever books are sold!)

#history#writing#historical fiction#medieval history#medieval#middle ages#historical#masculinity#history of masculinity#toxic masculinity

854 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isaac Granger Jefferson (1775-c. 1850) was an enslaved tinsmith and blacksmith at Monticello. His brief memoir, written down by an interviewer in 1847, provides important, fascinating information about Monticello and its people.1 Isaac was the third son of two very important members of the enslaved labor force at Monticello. His father, Great George Granger, rose from foreman of labor to become, in 1797, overseer of Monticello — the only enslaved individual to reach that position — and received an annual wage of £20. Isaac's mother, Ursula Granger, was a particularly trusted enslaved domestic servant whom Thomas Jefferson had purchased in 1773.2 Ursula was a pastry cook and laundress; her duties included the preservation of meat and bottling of cider.

Isaac Granger Jefferson

Isaac Granger, thus, spent his childhood on the mountaintop near his mother and from a very young age, he would have performed light chores in and around the house. He himself speaks of lighting fires, carrying fuel, and opening gates.3 Because he and his parents accompanied the Jefferson family to Williamsburg and Richmond when Jefferson was governor, the young Isaac was witness to dramatic events in the Revolution. In his reminiscences he recounted his vivid memories of 1781, including Benedict Arnold's raid on Richmond and the internment camp for captured slaves at Yorktown.4

Probably about 1790, Isaac Granger began his training in the metalworking trades. Jefferson took him to Philadelphia, where he was apprenticed for several years to a tinsmith. His own account is the only source of our knowledge of this aspect of his working life. He learned to make graters and pepper boxes and finally tin cups, four dozen a day. A tin shop was set up at Monticello on his return, but he recalled that it did not succeed. He also trained as a blacksmith under his older brother "Little George" and, sometime after 1794, became a nailer as well, dividing his time between nailmaking and smith's work.5

By 1796, Granger had a wife, Iris, and a son, Joyce. At this time he worked extra hours in the blacksmith shop, making chain traces for which Jefferson gave him threepence a pair. Also in 1796, according to Jefferson's records, Isaac Granger was the most efficient nailer. In the first three months of that year he made 507 pounds of nails in 47 days, wasting the least amount of nail rod in the process and earning for his master the highest daily return — the equivalent of eighty-five cents a day.6

In October 1797, Jefferson gave Isaac and Iris Granger, and their sons Squire and Joyce, to Maria and John Wayles Eppes as part of their marriage settlement.7 Thomas Mann Randolph was in need of a blacksmith at the time, so he hired Isaac from Eppes,8 though records are fragmentary and inconclusive on this point. Isaac and his family moved to Randolph's Edgehill plantation in 1798. A daughter, Maria, was apparently born soon after.9 As some of Granger's memories indicate his presence at Monticello in Jefferson's retirement years, he may have accompanied the Randolphs to reside there in 1809.

Tragedy stuck in 1799 and 1800, when Isaac's parents and brother Little George all died within a few months of each other. The persistence of an African heritage at Monticello is indicated by the fact that, in their illness, the members of this family consulted a black conjurer living near Randolph Jefferson in Buckingham County.10 Shortly after Great George Granger's death, Jefferson gave Isaac $11, the value of "his moiety of a colt left him by his father."11

In 1812 an Isaac belonging to Thomas Mann Randolph ran away and was caught and imprisoned in Bath County.12 We have as yet no way of knowing if this was Isaac the blacksmith. Randolph owned at least one other Isaac in this period.

How Isaac Granger gained his freedom is also unknown. He reported that he left Albemarle County about four years before Thomas Jefferson's death. He met and talked with the Marquis de Lafayette in Richmond in 1824. In 1847, he was a free man in Petersburg, still practicing his blacksmithing trade at the age of seventy-two.13 His reminiscences, taken down by the Reverend Charles Campbell in that year, do not reveal whether he took the surname Jefferson by choice or whether it was imposed on him by a white official, as was the case with Israel Gillette Jefferson, his fellow member of the enslaved community.

The fates of Iris, Squire, and Joyce Granger are unknown. Isaac had a wife, apparently not Iris, in 1847. Campbell wrote that Isaac Jefferson died "a few years after these his recollections were taken down. He bore a good character."14

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

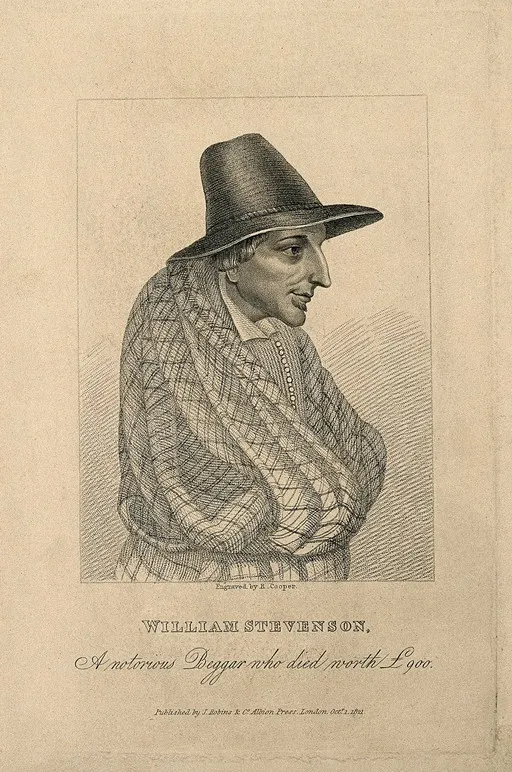

William Stevenson, the hoarding beggar died on July 17th 1817 in Kilmarnock.

William Stevenson was a Kilmarnock beggar who died with the equivalent of £80K in cash. He paid for a wake party with cakes and wine for Ayrshire’s poor and homeless that lasted for two weeks. He chose Riccarton Kirkyard because the earth was “nice an dry”.

Stevenson was trained as a mason, but spent the greater part of his life begging. Up until his last illness, the only thing we know about him was that he and his wife had separated. They must had hated each other a lot, because they had made an agreement that if one of them ever proposed they got back together, they would pay the other £100. As far as we know, they never saw each other again.

Stevenson fell ill at the age of eighty-five and was confined to bed. His chief concern was that what little money he had scraped together would not last. But it did. When he knew he was close to death, he began to make arrangements for a grand send off. He sent for a baker and ordered twelve dozen funeral cakes and a great quantity of biscuits. He ordered wine and spirits in correspondingly large amounts and said that more of both should be purchased if that proved to be insufficient. Next, he sent for a joiner and ordered himself an expensive coffin. Then the gravedigger, and asked for a roomy grave in a dry and comfortable corner.

He told an old lady who had been looking after him where she might find £9 hidden in his home to pay for all the expenses, and assured her that she had been remembered in his will. He died shortly afterwards and, when his room was searched they found a bag of silver pieces, more coins hidden in a heap of old rags and £300 hidden in a trunk. They also found bonds and securities. His fortune amounted to around £900. To the old lady, he left £20, which may not sound like much but, in today’s money, that’s close to £2,000.

William Stevenson lay in state for four days while his distant relatives were gathered to attend his funeral. But it was not a sombre affair. It was a party. Whole families were invited. He was visited by the young and the old, by beggars and poor tradesmen. The older attendees found they had each been left sixpence, the younger ones, threepence.

After the burial, everyone repaired to a barn, where most of them got so drunk that they had to be helped home. Some did not make it home at all, but fell asleep on a pile of corn sacks. The only account I could find of William’s funeral was by someone who clearly didn’t approve of it. It uses words like ‘wicked’, ‘careless’ and ‘waste’. It also goes on to say that those who missed the celebrations threatened to dig up his body so that they could give him another send off. They left him where he was, but apparently, the party continued for several weeks. That doesn’t sound like a waste to me. I think when a funeral is such fun that you want to do it all over again – that’s a pretty good funeral.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson: The Man with the Twisted Lip

Crimes in Context.

Sit down bloggers, it's time for a few rounds with my current least-favorite monetary system, and an actual scale of the wealth difference between the poorest and wealthiest Victorians. I already did some math here, where @thethirdromana did some research regarding other contemporary math failures about begging. I swear this will be interesting after we get through the math.

Imperial Currency Definitions

Pound, or "quid" or "pound sterling": Literally one pound of silver coins. (Sterling is a silver alloy.) The gold coin representing it was called a Sovereign. It's worth 240 pennies or 20 shillings. There was also a gold half-sovereign. (120 pennies, 10 shillings...)

Shilling: 1/20th of a pound. A silver coin.

Penny also pence, but only as a plural: 1/240th of a pound, or 1/12th of a shilling. Confusingly, there were silver pennies, copper pennies, and bronze pennies, with the exact same value, during the 1800's - silver pennies were minted specifically for royal charity, to be given out on Maundy Thursday. (The day before Good Friday.)

A lot of victorian accounts are written in Pounds, shillings, pennies, represented as L/s/d, but there were also other coins. I do not like them any better than this setup, but they provide context, so here we go.

Guinea: One pound and one shilling. Not it's own coin by the 1890's, since the last ones were minted in 1814, probably because they're stupid. I've seen it cited that if a professional gentleman was paid a guinea he got the pound and his clerks or assistants got the shilling.

Crown: Five shillings / a quarter pound. Represented by a silver coin.

Sixpence / Fourpence (Groat) / threepence / twopence (half-groat): conveniently, the numbers within the name tell you all you need to know. These were silver but twopence was also only minted for Maundy money during this era.

Halfpenny / Ha'penny: Half a penny, a bronze coin.

Farthing: A quarter of a penny, also a bronze coin, presumably for transactions like buying a single egg or leaving an extremely insulting tip.

Typical Wages:

Poverty:

Laborers and factory workers may get anything from 4 shillings (0.2 pounds) to 1 pound per week. Women and children were routinely paid much less for the same work as men. Francis Moulton's 8s room from The Noble Bachelor cost up to two weeks wages per night. If an average adult male working in a factory was paid about 1 pound per week, he would make about 50-52 pounds per year. If a maid was paid 4 shillings a week, she would make about 10 pounds a year. If a child was paid 1 shilling a week, they would make about two and a half pounds a year. My sources cited a variety of years from 1860 on, so take all of these as ballpark estimates.

The difference between 10 pounds and 50 pounds per year doesn't sound that stark, but today it's the equivalent of 1,000 pounds (1,200 USD) and 5,000 pounds (6,000 USD). Neither is enough to live on now, and it wasn't enough to live independently then, but it's the difference between living on L 2.7 / USD 3.2 a day and L 13.7 / USD 16.4 per day: You starve a lot faster at that first rate.

(Obligatory note that live in servants often had it better than factory workers making the same wage on account of having room and board provided as part of their compensation. Hence why a governess - a gentlewoman in distress - considers L50 a year a fairly comfortable wage: she's not paying rent, or for the bulk of her food. Like today's population of new graduates teaching English abroad.)

Comparative Wealth:

Neville St. Clair states he's making about L 700 a year by begging. This is the equivalent of 71,000 pounds / 85,200 USD today. It's about the same salary as a modern university chairperson. At the time of this story it's enough to live in an upper middle class suburb very securely, with several servants. It is, however, an absolute bullshit number. To acquire five hundred and sixty six (ish) pennies per day, in 691 coins, St Clair probably had upwards of five hundred people toss him a coin. Presuming that the reason nobody gave him twopence was low circulation of that specific coin, we can estimate that few, if any, people gave him three pence or more, judging by a lack of any of three pence, four pence, or sixpence coins. (There also aren't any farthings but I'm not sure what 0.25 pennies could actually buy you in those days. Possibly people who had any money to spare didn't carry them.)

If Neville works his corner for just long enough to get home by the 5:15 train, and it takes him maybe ten minutes to change out of his disguise, it's a reasonable assumption that he leaves his corner by 4:30 ish. He isn't noted as leaving particularly early in the mornings either, so I'm going to roughly estimate that he works about eight hours a day. If so he is earning more than a penny per MINUTE begging. He's getting someone throwing him a penny every 55ish seconds. There's a line of his benefactors dropping coins into his hat.

Threadneedle street was home to the Bank of England and the London Stock Exchange: presumably St. Clair picked this location because people going to and from either actually had some money to spare. But it also leads to an inevitable alternate idea: since it's impossible for St. Clair to be regularly making two pounds a day begging, perhaps his beggar disguise is for more criminal reasons... perhaps a long running plot to rob the bank? Either he is casing the place or he's a lookout. Or perhaps he's the accomplice of a clerk skimming his own pound or two a day out of the change from deposits, handing it over to St. Clair whenever he walks out for lunch or at the end of his day so that he's never discovered with a truly stupid amount of pennies.

And as far as Holmes is concerned... he's brilliantly deduced the bizarre portion of this case. Who cares that the scale of the begging is impossible? The Victorian middle class could be just as blinded by propaganda regarding the poor as we can be today. Even though there were no official public services and the myth of the welfare queen is a modern invention there were definitely people who resented the entire idea of charity: human nature has not completely changed in the last 130 years.

#Crimes in Context#Letters from Watson#The Man with the Twisted Lip#This wouldn't count as fictionalization as Watson wouldn't know#but it makes slightly more sense than St Clair's story being actually accurate#No I did not purposefully make it so that the two stories who reference red hair contain potential bank robbing#spoilers#Spoilers for the Red Headed League

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currencies in fantasy settings and particularly TTRPGs (and the genre of vidya games they spawned) is a personal interest of mine.

Because they're often really boring and plain. I shall now vent about this.

Now, there's one very good reason for it: players can't be arsed with exchange rates and complexity in this area. Gold is just how much wealth-per-stab your murderhobo is currently making.

The less good reason is designer laziness. Even on the rare occasions they decide not to just name them "gold, silver, copper" it's nearly always just a fancy fantasy name slapped on top of a decimal system.

For us that makes sense. Pretty much everyone uses decimal coinage these days.

You may be aware, however, that in the past most coinage was bonkers complicated - at least, to the modern person. Before decimalisation in the 1970s, the UK had a currency loosely based on a Base 12 system.

That is, you had 12 pence (d) to 1 shilling (s) and 20s to £1 (originally, pounds were only of real use to bankers and nobles, hence the shift in number). 1s could be subdivided into sixpence, threepence and tuppence, while 1d could be divided into hapennies (1/2d) and farthings (1/4d). You also had crowns (5s) and half-crowns, groats (4d, sometimes) sovereigns (£1, different name, don't ask) and guineas (eventually fixed to £1, 1s). Plus a whole bunch of short-lived coins, which happens when your system has never been properly reformed for 800 years.

When I, a decimal child, first learned about this I thought it was insane. How could shopkeepers do anything with that mess? But what I missed was that Base 12 is the easiest for the human brain to calculate.

Yes, without computerised registers (for which Base 10 was already standardised), a human merchant, shopkeeper or customer could do more with Base 12 because 12 has so many factors: it's divisible by 2, 3, 4 and 6. 10 is only divisible by 2 and 5. Despite all the weird extra coins tacked in, the basic units of pounds, shillings, pence (£sd) was easy to use. We changed it because everyone else was.

So on a setting without computers or even mechanised calculators, why do they have a decimal system?

Be brave! Confuse your readers and players! Make the currency Base 30 except for some foreign coins used as bullion that are treated as Base 7 for religious reasons.

This also lets you play around a bit with rewards - instead of a sack of coin worth 30 gold, why not present your party with some old gold coins that might be worth 30g to a lord's personal bank, or up to 200g to the right collector.

Escape from gold, too - explore your dwarves using palladium or various alloys, mithril fractions set in "less precious" metals, etc. Elves might eschew coinage altogether and use other tokens that represent a value of age or crop yield. Pre-Meiji Japan based their economic system on rice yields, with 1 ryō (the basic gold coin) being equivalent to the amount of rice one person could eat in a year (a koku).

Of course for the sake of ease you should always have a conversion chart handy, but I find that toying with currency is a simple but very effective way to worldbuild and create immersion. Plus, it's just kinda fun.

#deafmangoes#world building tips#worldbuilding#creative writing#currency#rpg worldbuilding#ttrpg writing#ttrpg homebrew

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Citrus Farming Success Story of Hankey Citrus Farm

When land claimants, commercial partners and the government band together it leads to profitable ventures, and agriculture minister Thoko Didiza believes a citrus farm near Hankey is a prime example of what these partnerships can achieve.

Didiza visited the Threepence Farm on Tuesday where seasonal workers were picking fruit destined for the international market.

She praised the Katoo Family…

View On WordPress

#biggest citrus exporters in south africa#citrus farms in gauteng#citrus farms in limpopo#citrus hectares south africa#citrus industry background#citrus prices south africa#citrus season south africa#How many orange trees can be planted in a hectare?#How much does citrus earn per hectare in South Africa?#Is lemon farming profitable in South Africa?#Is orange farming profitable in South Africa?#south african citrus industry statistics#What crop is in highest demand in South Africa?#Where are most citrus fruits farmed in South Africa?#Which agriculture is most profitable in South Africa?#Which is the most profitable fruit farming?#Who has the biggest farm in South Africa?#Who is the biggest citrus farmer in South Africa?#Who is the largest producer of citrus?#Who is the largest producer of oranges?#Who is the leading producer of oranges in Africa?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

AHA

ok i've learned a few more things that have significantly expanded on the content I can reach in the beta (version b.6 rn!)! my journal was finally able to be assigned in the the wisdoms tree, but I'm not sure when that became available.

you can indeed get more elements of the soul! Assigning skills to the tree catalogs them, and gives you an element.

there's several forms of crafting I'm seeing but I haven't been able to find the relevant materials just yet for the ones I see. so far I've collected wood, metal, fabric, flower, and leaf type materials

Visitors will occasionally show up, but they only stick around for 20ish seconds, and theres not a big indication they've arrived, they just appear in the sundries tab. You can please them with a skill or a book for spintria

Oriflamme's has shown up exactly once for me at the beginning of a new spring with a special new book I could buy with spintria! You can still sell spintria for mundane currency, but spintria are few and far between for me right and mundane money is very easy to get. It's 2 shillings to recruit someone for the day and thats two sessions of work at Sweet Bones

Skills are upgraded through memories that match their corresponding aspects. Interestingly, the skill only has gained exactly the amount of the aspects on the memories used to upgrade

Memories are probably the most important thing to collect. You get the weather each morning, but all memories break the next dawn. It's best to focus on one or two things to unlock or upgrade at a time so you can consider them quickly enough

So far I've generated memories by speaking to my initial friend, using Ereb at Sweet Bones, rereading a book, and visiting the moor. I think I can probably gain memories from beachcombing as well, but I've only just gotten the right soul elements to do that verb. Probably get memories or possibly lessons from the various crafting stations. Weather changes based on the season and is random each day. I've mostly been using it to exalt a follower to unlock rooms so far

There are two desks close to the start of exploring the hush house that require different aspects to be used, but I'm having an easier time unlocking book mysteries through consider still right now.

Completing a book mystery seems to usually give you a new lesson that you can then use to get a skill. more on this later as I begin to understand this whole system.

you don't have to have the specified amount of aspect to unlock a book's mystery, that just guarantees it. if you fail the initial check, you get a chance to view furniture and walling hangings

british money is so annoying im trying to get rid of my small change so i dont have a dozen different currencies in my sundries pocket but rn im still stuck with a twopence and threepence coin right now. money automatically combines higher when you have enough currency, including spintria, thankfully. if you want to break it apart you can talk to the postlady but right now you get your change back.

interestingly, depending on the element you use for work at Sweet bones, you can either get sixpence, or literally pennies. Phost, mettle, chor, health, and shapt all give sixpence, Fet and trist have been "fortunetelling" for pennies

I'm guessing mastering a wisdom means filling out a branch in the wisdom tree currently - which means you have to take care to place your skills wisely in it. make sure to pay attention.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

💎📷 ?

My most prized possession is probably my great-grandmother's charm bracelet from the 40s. It's got a lot of neat little things, but to me the most interesting one is the New Zealand threepence minted in 1943. No idea how she got it, as no one in my family is from New Zealand, and as far as I know she never visited.

My lockscreen is less exciting, just a picture of this massive pine tree outside my house.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Gold Plated 1920 George V British Silver Threepence (.500) Long Necklace.

0 notes

Note

Please please please draw Charlie from Thank Goodness youre here, he needs love

Yes i will

Charlie somehow retrieved that threepence, three cheers! But the little one wants it too… Oh well.

I love charlie to death he’s such a fun character that got beat up a surprising amount of times in the game

#thank goodness you're here#thank goodness you’re here game#tgyh charlie#ask#charlie’s so proud of himself#and i am proud too#i think he brought the least amount of trouble to the salesman

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas 2023.

Another Christmas Day has arrived and is almost over, and as I reflect on my childhood, I’m surprised that I don’t have many memories of this special day. I’m not sure why.

However, one memory that stands out is being at my Grandparent’s house when I was about five years old. I always hoped I would be the lucky person to get the threepence in the pudding, even though I was not too fond of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Currency Crisis in Ireland 1780-1810

The end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries was a time of an acute shortage of ‘hard cash’ in Ireland and this was due to the fact that:

Currency issued by the Royal Mint was limited to small copper coins; penny, twopence, threepence and fourpence

The English Treasury had run out of silver and gold since the reign of Queen Anne

They were relying upon the periodic…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The old man narrowed his eyes, this time studying my face, and he said, “Can I see one of the shillings?”

I handed one over, as well as a threepence, for his perusal. He scrutinized the coins with the same intensity with which he had the watches, with a magnifying glass and a carefully-applied light.

“I’m going to assume,” said the pawnbroker, still studying the coins, “that you don’t have a bank account, let alone a phone or credit card. Am I right?”

“You are,” I admitted, filing the words away for the time being.

“Well, I don’t carry this kind of cash anymore. If you have five of these shillings, I can give you three hundred pounds for them and the threepenny. If you’re mindful, that should be enough for a room and a couple meals, maybe a change of clothes for the both of you. If that’s the kind of thing you’re looking for.”

“That’s precisely what we are looking for.” Three hundred pounds! Three hundred! And such a dizzying sum could only afford a room and a few meals? How far was this distant future?

“Then you can come back tomorrow and we can discuss... the rest.” His eyes flicked between the two of us.

Whether we should return tomorrow is something I would need to consider later on. It was enough at the moment not to flinch when I provided five shillings and three pence and received in return three hundred pounds.

#excerpt from a short I haven't named beyond “WTT”#the main character is someone you know#dun dun DUN#filed under: things I'm working on that aren't my book#gwens pen

0 notes

Text

#aFactADay2021

#315: pre-decimalisation british currency was a nightmare. you had a penny, which was actually about 41.6% of the value (not inflation adjusted) of a new penny. you also had a half penny, which is a bit smaller than a penny, and a quarter penny, which was even smaller. it was called a farthing, which comes from fourth-ing. buuut unfortunately these were withdrawn in 1960. going upwards from a penny, we have our first non-copper coin, the brass threepence. next up is a sixpence, which was made out of silver and also called a tanner. a shilling, equivalent to twelve pence, was known as a bob. a florin is worth 2 shillings, or 24 pence, and a crown is worth 5 shillings, or 60 pence. there was also a half crown, worth 2 shillings and 6 pence, written as 2s6d, "two-and-six" or 2/6, confusingly. the d for pence actually comes from the roman coin denarius.

you thought we were finished!!!

theres also a thing called a double florin, worth 4s, but only survived for about 4 years. then there was a 10s note, and of course, the one pound note.

so, in order, we have...

farthing - 1/4d

hapenny - 1/2d

penny - d

thrupence - 3d

tanner - 6d

bob - 12d or 1s(hilling)

florin - 24d or 2s

half crown - 30d or 2s6d

double florin - 48d or 4s

crown - 60d or 5s

ten bobs - 120d or 10s

pound - 240d, 20s or £1

... thats just toooo many

0 notes