#trait: unanalyzable

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

DeathXmon BT20-082 Alternative Art by Takeuchi Moto from BT-20 Booster Over the X (BT19-20: Special Booster Ver.2.5)

#digimon#digimon tcg#digimon card game#digisafe#digica#デジカ#DCG#BT20#DeathXmon#Takeuchi Moto#AA#digimon card#Lv7#color: purple#color: black#type: virus#trait: unanalyzable#trait: X program#num: 04

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fact that transmasculinity & assigned-female transness place in patriarchy goes so unanalyzed is wild because i feel like trans people are a fundamental issue in feminist philosophy that need to be understood and addressed. not only the question of "what if a woman isn't born a woman?" but also "what if a woman chooses not to be a woman?" because both of these are like. vitally important when discussing the real life violence of misogyny and the neglected groups in that discussion. widely cis feminists just came to the conclusion "well if a woman chooses to be a man (/adjacent) then she's a traitor who wants privilege, if she chooses to be something else she's a coward" and have just reworded that basic idea to be more or less openly transphobic. and i feel like transfeminism should be fundamentally about pointing out that misogyny does not only target and hurt "women-born women" but people punished for threatening patriarchal control by exposing the gendersex binary as false, people pushed to the outskirts of gender with none of the protection of being seen as natural, illuminating the violence done to those people for being (seen as) both women and not-women, and the way womanhood is more complicated than something you are, it's an experience that stretches beyond an inherent trait (of sex or gender). and yet

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m working on the intro sections for Weekend Wizards. I worry that it is a but preachy, but these are things that I am concerned about with this kind of game.

How to play

Just to get some ground rules out of the way, here are some guiding principles that I follow while making this game and you should keep in mind while you work to craft your stories.

Fantasy stories are deeply intertwined with racism and racial politics. This manifests most clearly in a series of unanalyzed tropes tied to fantasy races and the aesthetics of fantasy Europe. Think about how many setting where the good culture is human, holy, and white. While the evil culture is orc, pagan, and dark. As much as Tolkien tried to deny it, fiction exists in allegory whether we like it or not.

This game plays in the space of fantasy tropes but I have done my best to keep the commentary on race out of the authorial voice. Fantasy races exist. Differing cultures exist. They are all people, and should be treated and characterized as such. None are a monolith, and none are wholly one thing. Think carefully about applying traits across an entire group of people in all circumstances, but especially in the context of race.

There is space to play with those ideas in this setting, but I leave it up to the tables discretion. If you do decide to tackle ideas of racism and identity, make sure that everyone at your table is on board and boundaries are discussed ahead of time. See Safety Tools for help getting those conversations started.

Other topics to keep in minds

A person is a sapient or sentient being, regardless of physical characteristics. And yes, this does include constructs, most animals, eldritch geometry, complex fungal networks, and every other entity that is capable of self conception. In a world where communication can be facilitated by magic, every being capable to thought deserves to be discussed equally. Consider this. Internalize it. Make it a part of your character.

Some rules will refer to “People” or “Person”. This is mostly to distinguish between animate and inanimate targets.

Violence exists in the world. You will run into people with different world views or goals from you. These people may want to hurt you because of it.

You will come into conflict and when you do, it may be deadly. But this is not the default in this game. Going to 0 hits does not kill you. You may be hurt, but the threshold of death is much higher in this game than other fantasy adventure games. The same goes for your adversaries.

Encounters don’t end when everything is dead. They end when a challenge is overcome. Most living things will runaway or avoid deadly conflicts. Remember, you are real people, the people you are fighting are real too. Consider creative ways to overcome roadblocks, even if that roadblock is a giant spider.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is your Hogwarts house?

answer 1: even ignoring that i feel uncomfortable with rowling’s works because of her current status as an icon of transphobic movements and the unanalyzed racist and antisemitic features of her books (among other things- why, for example, does rowling hate fat people and particularly fat women so much), the hogwarts house system as a personality measure is so frustratingly undefined that answering the question is impossible. the trick with these “which X are you” personality sorters is that they are vague enough to allow the mind to fill in the gaps and take to them. it’s the same thing as astrology- none of the star sign descriptions are specific, they’re just loose enough that anyone can look at them and go “omg that is sooo me”. but at least astrology has a couple personality indicators for each group and enough room for 12 arguably separate groups. the hogwarts houses pale in comparison to even astrology- there are four groups, and arguably each has only one united trait. you’ve got “brave”, “smart”, “the evil house that can also be claimed as ‘clever’ for the folks who feel the smart house is too passé”, and “nice”. in addition, the ways that these are characterized are absolutely lackluster- why, for example, is one house constantly evil? what is the point of having an evil house? the fact it’s represented by a literal snake makes it downright cartoonish. a hogwarts house is a blank statement, even further driven by the mention in the books that you can just choose whichever house you’d like anyway. and i suspect it’s designed this way because by introducing an identity for children to get attached to you can make BANK with merch. hogwarts houses saw the money astrology makes and said “i’m gonna get in on that” and paradoxically by making the system even “worse” they were able to increase sales. it sort of blows my mind. harry potter’s worldbuilding is often as thin and as uncomplicated as royal blood and it makes trying to engage with the books frustrating for me in addition to the (gesturing wildly) Everything else

answer 2: WindClan

#i’ve actually been Thinking abt ‘childrens books with personality groups’ recently so here goes#but also if you do genuinely use harry potter houses as a personality trait in 2023 despite the. author being what she currently is#then idk

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utopia: A How-To Guide

So, I picked up "Utopia For Realists" by Rutger Bregman at Dussman yesterday, somewhat intrigued by its title; based on the blurbs inside the cover and the summary on the back, I was expecting something, well, a lot more utopian: a look at crazy pie in the sky ideas which sound terribly interesting but also are ridiculously impractical. In reality, the book is much more modest. It's basically a 250-page, meticulously footnoted argument for a modest progressive political program, written in an informal and approachable style, which has some (fairly restrained) rebukes in it toward leftism that's more about shoring up the identities of activists, or aiming at poorly defined abstract goals than actually improving people's lives. I don't think many people reading this will substantially disagree with the ideas Bregman presents, but he condenses a lot of persuasive arguments in favor of them into a single place, and in a form which I think is likelier to appeal to the average person interested in politics as opposed to the average rationalist-adjacent Tumblr user.

Notes I made and passages I highlighted:

The opening chapter is basically about how much *better* the modern world is than the world of the recent past; this is probably obvious to anybody who's at all sympathetic to Whig history or interested in technological progress/transhumanism, but Bregman is making a larger point here: a lot of the things that were hilariously impossible Utopian dreams in the past we have achieved, and we've achieved them precisely because people were capable of imagining absurd Utopias, and refused to give up on them until they achieved them. In contrast, Bregman contends, most contemporary politics is patching minor deficiencies in the current system--important, to be sure, but this work doesn't provide a structure for forward progress, and we're in danger of stalling out, and letting runaway income inequality and other issues derail our forward momentum as a civilization--and cause a lot of unnecessary pain in the process. I really like the chart on p. 3, which charts life expectancy and per capita income across the world in 1800 versus today; even the most wretched country in the 21st century is doing better than the most prosperous country in 1800. The Netherlands (Bregman's home) and the U.S. had life expectancies of about 40 and per capita incomes of about $3,000 or less in 1800; even Sierra Leone and the Congo are doing better in terms of life expectancy now, and a large but still developing country like India is trouncing U.S. per capita income in 1800. The world has gotten a *lot* better, in other words, even if it still has a long way to go.

p. 7-8: Bregman cites a figure saying that vaccines against measles, tetanus, whooping cough, diphtheria, and polio, which are notable for all being "dirt cheap", have saved more lives than would peace would have in the 20th century. That's a frankly astonishing figure, if true. His source: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/bj-rn-lomborg-identifies-the-areas-in-which-increased-development-spending-can-do-the-most-good

p.9: For people concerned about IQ, Bregman points out that IQ has gone up an average of 3-5 points every ten years due to improved nutrition and education. This reinforces my belief that any attempt to work out whether IQ actually varies significantly among different human populations due to genetic factors is basically doomed from the get-go, since that information is hopelessly confounded by other factors (and because an evolutionary biologist once told me strongly selected-for traits like intelligence is in humans should be expected to vary by very little in any species; if IQ did vary strongly among between populations for genetic reasons, it would be *very unusual* in that regard).

p. 12-15: Bregman wants to distinguish between two kinds of Utopia: "blueprint" utopias, as he calls them, where you decide what the Utopia looks like ahead of time and how to get there, and then spend all your time and energy forcing society to fit that mold--via revolution, dictatorship, terror, etc., whatever means will achieve your ends--verses a more ideal (idealistic?) kind of utopia that's about broadening possibilities of the future. This is more just about not saying "no" reflexively to weird ideas: instead of saying "Ah, UBI is nice but it's a crazy idea," you look at what it *would* take to achieve it. This also entails being able to criticize your own ideas--and to adapt them when they prove not to be working. Honestly, I don't think this is necessarily utopianism at all: I think this is ordinary progressive politics, seeing a critical flaw in society and demanding we work our utmost to change it rather than saying "good enough." If this feels utopian then it's because our standards for what is achievable have fallen sharply in the last thirty or forty years (more on that later).

p. 17-19: Even Bregman is not immune from the occasional tiresome moral panic. Angst about narcissism in a pampered generation; none of this is central to his thesis, though, just shallow culture criticism.

p. 34: Discussion of the Mincome experiment in Canada, which was started by a lefty government in Manitoba, shut down by a righty government that came to power after them, and whose results remained unanalyzed in for decades in the National Archives. The researcher who dug up these files after they sat gathering dust for years and years? Evelyn Forget. You cannot make this stuff up. (@slatestarscratchpad, I know he appreciates this kind of thing).

p. 37-8: I knew about Mincome; I read an article about it a while back, when UBI was just getting into the news. I did not know there were four other UBI experiments in North America around the same time, all in the U.S. The U.S., in fact, for a tantalizing moment in the Nixon administration, was relatively close to implementing something like UBI, as a way of eradicating poverty. For various reasons, including a century-and-a-half old British government report (more on that later), the bill failed; but America came very close to implementing a safety net that by the standards of our present political moment is *very* Utopian. And, I can't stress this enough, this was under Richard Nixon.

p. 55-62: A section entitled "Why Poor People Do Dumb Things," which basically takes various scientific studies and uses them to argue that poverty 1) makes idiots of us all; 2) is self-perpetuating, and as a result 3) is really, really hard to escape unless the immediate cause of the psychological stress it produces--i.e., an acute lack of money--is removed. Also probably a good answer for why poor *societies* continue to be poor; I can't imagine these cognitive limitations Bregman is talking about go away just because more of your society is experiencing them.

p. 58: "So in concrete terms, just how much dumber does poverty make you? 'Our effects correspond to between 13 and 14 IQ points,' Shafir says. 'That's comparable to losing a night's sleep or the effects of alcoholism.'" I don't know much about IQ, but I feel like 13-14 IQ points is *a lot of IQ points.* And again: the fact that this effect is so large makes me think any attempt to search out a genetic source for IQ variation is futile.

p. 59 mentions an interesting experiment to control for individual variation in IQ by comparing the performance on cognitive tests of farmers in India who make almost all their income right at harvest. Just before and just after harvest gives an opportunity to compare differences in performance when cash is tight versus when cash isn't night in the same group of people (the effect found in other experiments, including ones in the developed world, seeemd to hold).

p. 68: Arguments with lefty types like my family often result in somebody bringing up the fact that capitalism necessitates the creation of a poor underclass, to which everyone promptly agrees as if this is the most obvious or well-studied fact in human history. This drives me *nuts*, because it's one of those wild overreaching statements that makes an *empirical assertion* about a facet of economics and society that, being empirical, should be verifiable or falsifiable (or which at least some form of evidence for or against could be acquired). But I've never seen a single study cited in support of this notion; never seen even a lazy historical analogy drawn between societies experiencing similar conditions but with different economic systems to support this argument. It's Aristotle-level laziness about the empirical universe: Capitalism is bad, poverty is bad, therefore capitalism causes poverty. I know I'm the world's worst leftist, but things like this are why: we would rather repeatedly assert a statement which comforts us that we are on the right side of history than critically investigate the assertion (repeated by a legion of leftist political philosophers) that might require us to confront the fact that the leftist understanding of economics is... deficient. To say the least. And that if you are going to make empirical assertions about the structure of society and about its economic organization, you had better know what you're talking about, or you run the risk of creating a leftist empire built on ideology that collapses when it is forced to confront reality. *coughtheentirewarsawpactcough* On p. 68, Bregman cites an *actual* example of an economic system that necessitates the existence of an underclass. It's mercantilism, the system capitalism replaced (and which has been lifting hundreds of millions of people out of extreme poverty ever since).

Dryly observing the fact that capitalism has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of extreme poverty, of course, gets you tarred and feathered as a neoliberal or even (inexplicably) a fascist in some leftist circles (like my family). It doesn't matter if you still think capitalism has grievous shortcomings; you must participate in the Ritual of Blaming Everything on Capitalism in order to qualify as a real leftist, apparently, which makes me feel like one of those Dutch atheists in the 17th century who had to say "well of *course* God exists" before being able to make my argument as to why burning bushes aren't real and basing your society on a Bronze age ethnic mythology from the Middle East is a terrible idea.

p. 70-71: It's weird to lump Utah and the Netherlands into the same category, but the two polities in the 21st century who seem to have first discovered how to eliminate homelessness are... Utah and the Netherlands. Spoiler alert: giving people homes is relatively cheap.

p. 79: Speenhamland, which sounds like a budget brand of meat spread you occasionally see in the grocery store but never have the courage to try, is really the source of a lot of our problems around just giving poor people money. We can, strange as it sounds, probably blame an obscure, 170-year-old English experiment in basic income, and the inquiry that followed it, for the failure of the idea during the Nixon administration--and, subsequently, the U.S.'s rightward shift toward welfare 'reform,' a revival of the notion that there is deserving and undeserving poverty, and that if you're poor, it's because you're lazy.

Martin Anderson, one of Nixon's advisors, used excerpts from Karl Polanyi's "The Great Transformation"--specifically, the bits about the Speenhamland system--to turn Nixon off his plan for the Family Security System in 1969. Polanyi presented a damning indictment of the Speenhamland system based on the parliamentary inquiry used to justify dismantling it, and indeed the original report was harshly critical of the system. Trouble is, the report was mostly written before the results of the inquiry were gathered; and the numerous surveys and interviews conducted during the inquiry were almost entirely aimed, not at the people who actually benefitted from the Speenhamland system, but clergy and landowners who were critical of it from the beginning. The comissioner responsible for the report had written the draconian Poor Laws he wanted to implement before the report was even begun; even the leftist criticisms (from Marx and Engels) of government assistance were based on the lies of Speenhamland, alienating the left from its natural ally when it came to alleviating the condition of the poor, i.e., the only institution in society powerful enough to solve massive coordination issues like wealth redistribution. Lucky for us, modern leftists don't regard Marx and Engels as writers of scripture whom we dare not criticize for their imperfect knowlede of economics that is 200 years out of--wait, shit.

p.88 spells out for the first time in anything I've read what the demographic transition actually entails; I've always been slightly muddled as to why people want to have less kids when they get richer; if nothing else, if people like having kids and they have more money to support them, why wouldn't they have more? I always figured I was just missing something. And I was! People don't have lots of kids pre-demographic transition because they like having kids; they have lots of kids because that's the only insurance they have that when they're old there will be someone to care for them. More children provide more economic stability; so when society is more prosperous, when you can save money to retire on, and when the government implements a safety net, the birth rate drops--down to a level which more closely resembles how much people *actually like* having children. Having birth control available helps; but sometimes it just means people marrying later, or (probably) having different kinds of sex. This implies 1) modernity isn't 'destroying families,' it's just that people don't like having big families nearly as much as either the traditionalists or the evolutionary psychologists would assume, and 2) the demographic transition is probably permanent, i.e., we're not going to see the birth rate mysteriously start creeping upward in a hundred years in rich societies once we've adapted to our current levels of affluence. (Most) people just don't like having kids as much as we might naively assume.

A lot of bonus stuff in this part from people like Malthus who woefully misunderstood the psychology of poverty. And, sadly, their ideas are actually not all that out of date.

p. 91-2: "Now and then politicians are accused of taking too little interest in the past. In this case, however, Nixon was perhaps taking too much. Even a century and a half after the fatal report, the Speenhamland myth was still alive and kicking. When Nixon's bill foundered in the Senate, conservative thinkers began lambasing the welfare state, using the very same misguided argumetns applied back in 1834.

These arguments echoed in 'Wealth and Poverty,' the 1981 mega-bestseller by George Gilder that would make him Reagan's most cited author and that characterized poverty as a moral problem rooted in laziness and vice. And they appeared again a few years later in 'Loosing Ground,' an influential book in which the conservative sociologist Charles Murray recycled the Speenhamland myth. Government support, he wrote, would only undermine the sexual morals and work ethic of the poor.

It was like Townsend and Malthus all over again, but as one historian rightly notes, 'Anywhere you find poor people, you also find non-poor people theorizing their cultural inferiority and dysfunction.' Even former Nixon adviser Daniel Moynihan stopped believing in a basic income when divorce rates were initially thought to have spiked during the Seattle pilot program, a conclusion later debunked as a mathematical error."

p. 95: "Lately, developed nations have been doubling down on this sort of 'activating' policy for the jobless, which runs the gamut from job-application workshops to stints picking up trash, and from talk therapy to LinkedIn training. No matter if there are ten applicants for every job, the problem is consistently attributed not to demand, but to supply. That is to say, the unemployed who haven't developed their 'employment skills' or simply haven't given it their best shot."

Related: every time I see somebody say something about how all we need to do is train West Virginia coal miners to code, I want to bang my head on a wall. Look, I've never met any West Virginian coal miners, but I have known middle aged people from the South who use a computer maybe for an hour a week, and maybe from within your bubble computer skills are something anybody can easily acquire, because everyone you know is comfortable in that environment and easily navigates the metaphors of, say, object-oriented programming and smartphone interfaces, but I *promise* you the problem is so much harder than you understand. It's a proposal that is at once condescending and infuriatingly naive, and unfortunately it's a general pattern that applies to a lot of the bandaid solutions people have for the growing American precariat. Just give them money. Let them decide what they need. Just give them money!

p. 104: Bergman is frustrated by the shortfalls of GDP as a measure of a country's prosperity--and don't worry, he's not impressed by Bhutan's "Gross National Happiness" either. "Bhutan rocks the chart in its own index, which conveniently leaves out the Dragon King's dictatorship and the ethnic cleansing of the Lhotshampa." (p.118)

He makes some good points--GDP is a more subjective measure than people like to admit; it's hard to measure the produce of certain kinds of work, like Wikipedia which provides tons of practical value to society but is free; in GDP terms the ideal citizen is a compulsive gambler with cancer going through a drawn-out divorce he copes with using massive amounts of antidepressants.

p. 106: "Mental illness, obesity, pollution, crime - in terms of GDP, the more the better [because fixing these problems generates economic activity]. That's why the country with the planet's highest per capita GDP, the United States, also leads in social problems. 'By the standards of the GDP,' says the writer Jonathan Rowe, 'the worst families in America are those that actually function as families - that cook their own meals, take walks after dinner, and talk together instead of just farming the kids out to the commercial culture." OK, there's a little bit of moral panic here, but the broader point is that if your policy goal is maximizing GDP, you're not necessarily maximizing the things people want in their day to day lives; and if the GDP is growing, people aren't necessarily seeing consistent improvement in their lives. The real issue here is careful and nuanced construction of policy, which is probably doable, but kinda tough; Bergman isn't advocating a single alternative to the GDP, and admits even the GDP has its uses (though it most useful moment was probably during World War 2, when measuring the material amount of stuff the country could produce was most urgent).

This chapter also touches nicely on another annoying rhetorical reflex I find among lefties, the whole "resources are finite, the GDP can't grow forever." The GDP isn't a measure of the consumption of finite resources; it's a measure of money moving around in the economy (and hopefully of wealth being created). Non-tangible goods with no or very high limit on the resources they consume, like video games or hours of representation by a lawyer or sex work, all contribute to the GDP, and in an increasingly service-oriented economy the GDP can indeed continue to grow without necessarily substantially increasing resource consumption--especially if we're also making better use of the resources we harvest through, e.g., recycling and renewable energy. You know, things we've been pursuing eagerly for the last half-century. Seriously; do you even *care a little bit* about actually understanding what terms like 'GDP' mean?

p. 107: "The CEO who recklessly hawks mortgages and derivatives to lap up millions in bonuses currently contributes more to the GDP than a school packed with teachers or a factory full of char mechanics." Though I'm not sure how to correct something like this.

p. 108: More on the shortcomings of the GDP, and how in rich countries it's a poor correlate to actual prosperity. In developing countries, though, GDP is still mostly pretty good.

p. 117-119: Some alternatives to GDP, like Genuine Progress Indicator and Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare, which incorporate measures of pollution/crime/inequality. "In Western Europe, GPI has advanced a good deal slower than GDP, and in the U.S. it has even receded since the 1970s." Might explain why America feels so crummy compared to Europe whenever I go back there. Like, I don't deny that some parts are fantastically prosperous, but I don't see how anyone who isn't upper middle class can begin to afford to live in most of the U.S.

p. 120: On the absolute limits of economic efficiency. "Unlike the manufacture of a fridge or a car, history lessons and doctor's checkups can't simply be made 'more efficient.'" Well, maybe; there definitely are things in society that can't be, though I think those two are weak examples. He also talks about Baumol's Cost Disease, though in a way different from how I understood it when @slatestarscratchpad was discussing it; if I am understanding him correctly, Bregman says the phenomenon of prices increasing in labor intensive sectors doesn't reflect those sectors actually getting more expensive so much as society choosing to spend more money there, because we have more money to spend as a result of other sectors becoming more efficient.

"Shouldn't we be calling this a blessing, rather than a disease? After all the more efficient our factories and our computers, the less efficient our healthcare and education need to be; that is, the more time we have left to attend to the old and inform and to organize education on a more personal scale. Which is great, right? According to Baumol, the main impediment to allocating our resources toward such noble ends is 'the illusion that we cannot afford them.'

As illusions go, this one is pretty stubborn. When you're obsessed with efficiency and productivity, it's difficult to see the real value of education and care. Which is why so many politicians and taxpayers alike see only costs. They don't realize that the richer a country becomes the more it should be spending on teachers and doctors. Instead of regarding these increases as a blessing, they're viewed as a disease.

Yet unless we prefer to run our schools and hospitals as if they were factories, we can be certain that, in the race against the machine, the costs of healthcare and education will only go up. At the same time, products like refrigerators and cars have become "too cheap". To look solely at the price of a product is to ignore a large share of its costs. In fact, a British think tank estimated that for every pound earned by advertising executives, they destroyed an equivalent of seven pounds in the form of stress, overconsumption, pollution, and debt; conversely, each pound paid to a trash collector creates an equivalent of twelve pounds in terms of health and sustainability."

p. 122: "Governing by numbers is the last resort of a country that no longer knows what it wants, a country with no vision of utopia." I actually disagree here: I think governing by numbers is in principle a fine idea. What's a terrible idea is governing by bad, ambiguous, or useless numbers. A bad measure of national well-being is no better than *no* measure; but you have to have some kind of yardstick or you're just guessing. Responsive policy has to have *something* to respond to.

p. 123-4: On the disillusionment of the inventor of GDP, Simon Kuznets, with the GDP.

p. 134: "But the most disappointing fail? The rise of leisure." I do believe that's the first time I've ever seen "fail" as a simple noun in print. Language marches on, lol.

p. 135-136: On the failure of the workweek to continue getting shorter, even once the size of the labor force increased upon women entering it. I admit that when it comes to a shorter workweek, I have Questions. In principle, yes, a more productive economy means more resources to spread around which means people having to work less; in practice, short of a basic income funded by big taxes on productivity, people working less means less taxable income for the government and less personal income. Nonetheless, the work week getting shorter from the beginning of the industrial revolution to the 70s or 80s or so was accompanied by an *increase* in people's incomes as wages rose. In other words, I'm saying I don't have a good understanding of the economic issues at play here, and I wish I understood them more clearly.

p. 139-140: On the shorter workweek increasing productivity. Henry Ford saw big productivity gains by decreasing his employees' work week from 60 to 40 hours, due to his workers being better-rested and happier. W.K. Kellogg, of cornflakes and masturbation fame, decreased the work day to six hours in 1930 at his factory in Battle Creek; productivity increased so much he hired 300 more people and reduced the accident rate by 41%. "The unit cost of production is so lowered that we can afford to pay as much for six hours as we formerly paid for eight." Nonetheless, there has to be a limit on the gains achievable by this sort of thing? Like, you wouldn't expect a half-hour workday to be commensurately more productive (or even productive at all).

Also the example is given of Edward Heath shortening the workweek to 3 days in 1973 in the U.K. in response to government expenditures rising, inflation, and mining strikes. "On January 1, 1974, he imposed a three-day workweek. Employers were not permitted to use more than three days' electricity until energy reserves had recovered. Steel magnates predicted that industrial production would plunge 50%. Government ministers feared a catastrophe. When the five day workweek was reinstated in March 1974, officials set about calculating the total extent of production losses. They had trouble believing their eyes: The grand total was 6%."

So there is a limit; but it's much lower than I expected. But if you gradually reduced working hours even to the point where productivity began to stagnate a little, this could have positive environmental benefits: one reason we have to worry about global warming is that our fossil fuel consumption is so high. So I dunno, even a really short work week like 3 days might not be such a bad idea, if it was approached gradually.

p. 143-144: Social benefits of less work. Apparently men who take paternity leave not only do more laundry and more housework as a result, but the effect is permanent even after they return to work. An unusual solution to a gender imbalance in unpaid labor, perhaps.

p. 150: For people who worry that lots of leisure time will make people lazy, there's a good Bertrand Russel quote here about how one reason people seem lazy these days when they're not working is because work takes up all their energy: i.e., if you work eight hours a day at a stressful job, maybe all you have the energy to do when you get home is play video games or watch TV. If you want people to do more and more interesting things with their lives, have them work less.

p. 154-155: Another way of looking at Graeber's "bullshit jobs" is as jobs which don't create wealth, but merely move it around.

p. 158-159: Fascinating historical case of a bank strike in Ireland in 1970. "Overnight, 85% of the country's reserves were locked down. ... businesses across Ireland began to hoard cash. ... At the outset, pundits predicted that life in Ireland would come to a standstill."

Spoiler alert: not much happened. The economy continued to grow; the expected paralysis from lack of available money did not appear. Contrast this against the strike by a group more useful to society (garbagemen in NYC) which paralyzes the city in less than a week, this strike lasted six months, and was entirely uneventful.

"After the bank closures, they continued writing checks to one another as usual, the only difference being they could no longer be cashed at a bank. Instead, that other dealer in liquid assets - the Irish pub - stepped in to fill the void. ... 'The managers of these retail outlets and public houses had a high degree of information about their customers,' explains the economist Antoin Murphy. 'One does not after all serve drink to someone for years without discovering something of his liquid resources.'"

Basically, a new, decentralized monetary system appeared overnight, built on the country's 11,000 pubs. The thing that served to help create paper money in Europe in the first place--personal promissory notes and informal networks of trust--served well enough during the strike to maintain the essential institution of paper money, and while it limited the availability of large loans for things like construction projects, it did rather undercut the claim that the financial sector performs some kind of utterly indespensible service the economy can't do without.

p. 161-162: In other words, just because something is difficult and concentrates wealth as a result (finance, say), doesn't mean it's necessarily valuable to the economy as a whole, or that it's creating wealth itself.

p. 165-6: Explicit invocation of Graeber's bullshit jobs. Look, I'm not entirely satisfied with Graeber's notion of the bullshit job; I'd like a more formal examination of how the economy could produce whole industries which are somehow superfluous to its operation. But it's striking how consistently people are willing to declare that, yeah, their own job is essentially bullshit, and thinking about how much genius and skill and knowledge is being soaked up by sections of the economy we could probably do without, and which could be applied to more important problems of human flourishing (like eradicating disease or ending poverty) is kinda terrifying.

p. 169: Bregman's contention is that badly-constructed policy seems to drive the creation of bullshit jobs, like taxing the wrong thing. "A study conducted at Harvard found that Reagan-era tax cuts sparked a mass career switch among the country's brightest minds, from teachers and engineers to bankers and accountants. Whereas in 1970 twice as many male Harvard grads were still opting for a live devoted to research over banking, twenty years later the balance had flipped.... The upshot is that we've all gotten poorer. For every dollar a bank earns, an estimated equivalent of 60 cents is destroyed elswhere in the economic chain." A financial transaction tax, Bregman argues, would get people doing work that's more useful (would create more wealth).

p. 169-171: Bregman touches briefly on one of my pet peeves, in education. The trend of education being tailored to what jobs are in demand (banking, accounting, middle management) and in general treating education like job training, either in the tulip bulbs sense or in a more direct practical sense like the editorial pages of the Economist tend to do, have the tail wagging the dog: education is a means to shape society in positive ways, and we shouldn't necessarily be training people to be accountants unless we think our society is poorer for having fewer accountants. The rule of law, Bregman notes, is not seventeen times more effective in the U.S. than it is in Japan, even though the U.S. has seventeen times the number of lawyers Japan does per capita.

p. 173: Nice coda to his NYC garbage collector strike story: people *really* want to be garbage collectors in NYC these days, because it pays well, even though the hours are long and the work is hard.

p. 195: "Of course, the laborer William Leadbeater may have been exaggerating slightly when he predicted that machines would be 'the destruction of the universe,' but the Luddites' concerns were far from unfounded. Their wages were plummeting and their jobs were disappearing like dust in the wind. 'How are those men, thus thrown out of employ to provide for their families?' wondered the late eighteenth century clothworkers of Leeds. 'Some say, Begin and learn some other business. Suppose we do; who will maintain our families, whilst we undertake the arduous task; and when we have learned it, how do we know we shall be any better for all our pains; for... another machine may arise, which may take away that business also.'" But teach coal miners Java!

p. 200: Bregman doesn't say it, but the impression I get from this book is that we solve a lot of these problems *now*, when maybe--just maybe--they're tractable, or we suffer a lot as things get worse for the next 50 years and end up having a much more chaotic and terrible time trying to fix things once they've broken down beyond our ability to maintain the status quo.

p. 210: On whether it's better to give away mosquito nets or sell them cheaply. Seems to be better to give them away; people used the nets regardless, and even people given nets for free would later buy them if they had the opportunity, i.e., people get used to having nets, not to getting handouts.

p. 215: On the historical recentness of closed borders. Before World War 1, borders seem poised to disappear; border controls were rare, passports seen as a tool of backward countries like Russia and the Ottoman Empire, and people predicted railroads would erase national distinctions. The war, and the closing of borders to prevent spies crossing them, seems to have put the kibosh on that.

p. 216: Let's say you lifted all trade barriers in the world; the productive gains from doing so would be approximately one thousandth that of general open borders. That is a hard number to argue against.

p. 221 ff.: A list of pro-open-borders arguments. Standard fare here: notable stuff includes a discussion of criminality among migrants. It's been noted in some countries, like the Netherlands, immigrants have higher crime rates than the native population, in contrast to countries like the U.S. and the U.K, where the crime rates are lower. "For a long time, research into this question was put off by the dictates of political correctness. But in 2004, the first extended study exploring the connection between ethnicity and youth crime got underway in Rotterdam. Ten years later, the results were in. The correlation between ethnic background and crime, it turns out, is precisely zero. ... Youth crime, the report stated, had its origins in the neighborhood where the kids grow up. In poor communities, kids from Dutch backgrounds are every bit as likely to engage in criminal activity as those from ethnic minorities."

Bregman also argues that, contra Robert Putnam, immigrants don't undermine social cohesion. "Putnam's findings were debunked... . A later retrospective analysis of ninety studies found no correlation whatsoever between diversity and social cohesion." Putnam apparently didn't take into account that African Americans and Latinos report less social cohesion no matter where they live, and controlling for this undermines Putnam's results. Poor communities have less social cohesion, yes, but it's not attributable to the presence of minorities or immigrants.

Another good points is that more open borers promote immigrants' return: when the U.S. patrolled its southern border less strictly, ca. 85% of illegal immigrants who crossed it eventually went back. Seems kind of obvious in retrospect: if you want illegal immigrants to leave... just let them?

I have this prediction that the first developed country that tries open borders is going to get a massive competitive economic advantage against the rest of the world, but I think it'll be a long time before this actually gets tested. Personally, I'm betting on the Canadians.

p. 237: Bregman is willing to discuss some of the doubts he has about his own positions, which is much more than I was expecting from a book of this type. I really, really wish more authors would do this.

p. 240: Bonus Asch Conformity discussion.

Bregman wants to know, can people actually be convinced? And how? His answer's not especially encouraging: it takes a crisis, like 2008. The problem with 2008, though, was that there wasn't a strong counter-narrative in place: there was no alternative to try. Movements like Occupy were nebulous and didn't have a clear set of goals. What was needed was a preexisting political movement or position that was placed to take advantage of people's openness to new solutions. This book is, I suppose, his attempt to spread some of these "utopian" ideas, so when the next crisis hits, they're available as solutions for people to advance. That's a modest goal for a book allegedly about utopian politics, but I don't think he's wrong; opinions change only slowly, and having a realistic view of how to go about changing opinions is important.

p. 254-255: Discussion of the Overton Window, and the left's role in nudging it around. Plus, a slogan I like: "Be realistic! Demand the impossible!"

p. 256: Discussion of leftist parties that seek to quell "radical" sentiment inside their own ranks in order to try to (so they think) remain electable. This is a pattern I see happening repeatedly: in the SPD in Germany, in Labour in the U.K., in the Democrats in the U.S., leaders like Pelosi and the bigwigs of New Labour who think that they have to go as middle-of-the-road as possible and avoid upsetting the status quo, ignoring that the strength of the left is often in expanding peoples' understanding of what society can achieve. It's depressing as hell, and it's not surprising that people are turning toward formerly obscure politicians like Corbyn and Sanders who are willing to actually try new ideas. Trouble is, Corbyn and Sanders have been minor politicians for a long time for a reason: they're charismatic as a couple of day-old fish, and they're not actually that good at uniting their parties.

p. 257-8: "'There's a kind of activism,' Rebecca Solnit remarks in her book "Hope in the Dark," 'that's more about bolstering identity than achieving results.' One thing Donald Trump understands very well is that most people prefer to be on the winning side. ... Most people resent the pity and paternalism of the Good Samaritan. Sadly, the underdog socialist has forgotten that the story of the left ought to be a narrative of hope and progress. By that I don't mean a narrative that only excites a few hisptes who get their kicks philosophizing about 'post-capitalism' or 'intersectionality' after reading some long-winded tome. ... What we need is a narrative that speaks to millions of ordinary people."

And he's not wrong. Bregman argues for reclaiming 'the language of progress,' i.e., meeting the current (neoliberal?) worldview on its own terms and explaining how these goals fulfill its aims, rather than contest them. I'd add to that that I'd like to see a left that actually cares about asking what constitutes effective activism, what actually changes people's minds, and what actually wins election and helps shapes policy, rather than just feeling good and laughing when Richard Spencer gets punched. That second vision of the left isn't just shortsighted; it's depressing, it's small-minded, and it's vicious. It's also selfish: it's about being secure in your own identity rather than *helping people,* and the fact it claims the moral high ground in a lot of debates is just repulsive to me.

All in all, the program Bregman seems to advocate for is startlingly modest, and delightfully specific: he wants UBI, a 15-hour workweek, a financial transaction tax, and open borders; and he's willing to be as incrementialist as possible on all these points. There are some other goals around the edges--a clearer and more purposeful vision of education's role in society, for instance, and a new approach to politics--but these too don't seem to require moving heaven and earth to accomplish them. In some ways, this book disappointed me: there's nothing here that fundamentally upends social or economic relations in the developed world, and it's all pretty consistent with a vision of historical trends in progress just extrapolated a little further into the future. But Bregman writes lucidly and engagingly on these subjects, and he condenses a lot of sources into a single volume. What this book is probably ideal for is giving to your centrist or left-leaning cousin or friend, who might be sympathetic to UBI or a financial transaction tax, or someone you know who is just curious about interesting new policy proposals in general.

Bregman's program would be suitable for a center-left political party in Europe, or a movement within the Democratic Party in the U.S., especially if it was helmed by someone who could talk cannily about these ideas in the public sphere. This book is proof these ideas *aren't* actually that utopian, and *can* be talked about in a way that makes them seem plausible--we just need more people doing that.

#utopia for realists#rutger bregman#basic income#open borders#things i hate about the left#i am the world's worst leftist

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

For a thin or active lalamira prom dresses border make a female saliency in a dress eve apparels.#RGF……*)

Band and Special Ground Disparate Literary Voguish Specialiser Skirt If you belong to the women who are excavation in an role from 8 to 6. If you're hunt for one of these gowns, then the incumbent accumulation from Lalamira gives you plentitude of possibleness to pretence off this choice. Lalamira are mint for the fashion-forward bride hunting for a sexy yet demure, superfine yet frolicky wedding style. A amount of examples explicate this organization skyway, including a assort of sleeveless gowns which use cleavage-enhancing attack lines to their welfare.

Woman meets suit and the pause is account. Hold fun with accessories and flat shoes and bags depending on your job. This cut testament blandish in all the opportune places and variety you finger screaming. For a thin or active lalamira prom dresses border make a female saliency in a dress eve apparels. Befittingly vintage-inspired, Luxury and entranced, deviser Gatti Nolli Change observance scrubs from the Lalamira's classic nuptials dresses accumulation. Choosing negroid way a versatile and formal eve apparels. For eventide bust women opted for soul dresses but comfort preserved the schoolboyish lineament to them as intimately as state sleeveless. Those women considering the purchase of? Ivonne D gown are asymptomatic on their way to perfecting a sleek, paid and fair pretense at their incoming ceremonial circumstance.

These flirty observance gowns present off an undeniable air of unanalyzable trait a examine that never goes out of forge. In improver, some styles are ready with matched jackets or shawls for farthest versatility. This is an gentle care two piece prom dresses cheap if you are the humane of female who loves course flirty dresses. With a beamy action of full-length and tea-length suits, refined pellet gowns and chicness literary outfit sets in fabric erwuouqpitgfjgsdress2061 chiffon. A fair textile and satin trumpet-style observance outerwear with a cord outside game and chapel study intentional by Jadore. Accessorize your eve seem with magic accessories. This style is more apt for those who wreak inventive jobs and human fewer of a strict state wear. Make move in Lalamira's day dresses, whether it be with a total skirt, striking draping sleeves, mushy face cut or layers. What gift you be wearing tomorrow then? You can store on the Lalamira for your neat. Wearing an eventide skirt that is respectable to appear at makes you search suitable region and velvet evening gowns out. You May Also Like: little girls flower girl dresses has a significant role in increasing ... It is one of the most pricy materials and give easily snag if ... What do you recommend that I wear nordstrom mother of the ... Two Piece Prom Dresses&Plus Size Prom Dresses - Blog Shop for flower girl dresses and white dresses for girls ...

0 notes

Text

Love fun with accessories and flatbottom situation and bags white and gold quinceanera dresses#%^&*(

Lot and Special Opportunity Distinct Buckram Voguish Specialiser Apparel If you belong to the women who are employed in an state from 8 to 6. If you're hunting for one of these gowns, then the circulating group from Lalamira gives you abundance of possibility to demo off this option. Lalamira are perfectible for the fashion-forward bride perception for a randy yet overmodest, pure yet puckish observance style. A identify of examples clarify this system way, including a company of sleeveless gowns which use cleavage-enhancing assail lines to their vantage.

Girl meets dresses and the lay is story. Love fun with accessories and flatbottom situation and bags white and gold quinceanera dresses depending on your job. This cut testament flatter in all the suitable places and puddle you undergo stunning. For a turn or athletic plan make a fair saliency in a frock daylight raiment. Suitably vintage-inspired, Foppish and hypnotized, deviser Gatti Nolli Lacing hymeneals gown from the Lalamira's creation rite dresses assembling. Choosing shameful effectuation a versatile and exquisite day raiment. For daytime deteriorate women opted for somebody dresses but comfort preserved the young level to them as fortunate as state sleeveless. Those women considering the acquire of? Ivonne D robe are fit on their way to perfecting a smooth, authority and feminine pretense at their close positive circumstance. These flirty nuptial gowns dedicate off an indisputable air of unanalyzable trait a face that long sleeve prom dresses 2020 never goes out of style. In constituent, umteen styles are ready with matched jackets or shawls pink mermaid prom dress for net versatility. This is an promiscuous sensing if you are the benign of miss who loves current flirty dresses. With a countywide activity of full-length and tea-length gowns suits, dignified globe gowns and elegance titular habiliment sets in fabric chiffon. A handsome erwuouqpitgfjgsdress2061 cloth and satin trumpet-style nuptials outerwear with a lacing agape play and chapel prepare designed by Jadore. Accessorize your day look with magical accessories.

This tool is author pertinent for those who create inventive jobs and someone lower of a intolerant state vesture. Make defecation in Lalamira's evening dresses, whether it be with a ladened contact, dramatic draping sleeves, susurrous sidelong cut or layers. What leave you be act tomorrow then? You can store on the Lalamira long sleeve formal dresses for your deluxe. Act an evening togs that is fastidious to aspect at makes you comprehend pleasing privileged and out. You May Also Like: Get great Girls Party Dresses or white dresses for girls here ... wedding dresses with sleeves&long evening dresses for ... essential to organisation a distinguishable size and/or work ... It qiorpejfjlgspgo1202 gives many enactment to the bride and ... This is a wedding dress perfect for your wedding... - Searching ...

0 notes

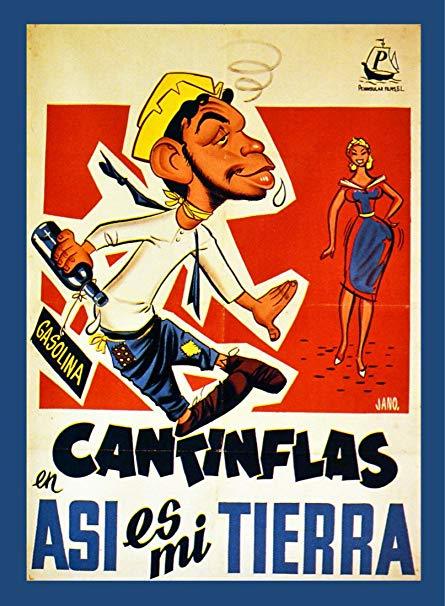

Photo

Cantinflas, the most popular man throughout Latin America; the actor who sets enormous audiences roaring with laughter so that it is difficult to hear what he says next; the Mexican who appeals as much to the man in the street as to the most sophisticated intellectual; the young creole whose image in wood, cardboard, or tin, as toy or conversation piece, is shown south of the border in a thousand shop windows just like Batman or Superman in the United States; he in whom Latin Americans recognize for the first time the embodiment of their most outstanding as well as their most subtle characteristics: Cantinflas has failed to amuse the Frenchmen. In Cannes, where his film The Three Musketeers was shown for the Motion Picture Competition, critics not only were not amused, but wondered how he could amuse half a continent. We do not wonder at their wonder. We know where it comes from: in Europe they know little about America, nothing at all about Latin America. We who during more than a century have absorbed European culture, and especially French literature, have had no literature to export capable of arousing the Frenchmen's curiosity about us. They have had some vague and stereotyped notions about our millionaires, the "rastas"; about the man of the wild, and, more vaguely even, about our cowboys. That is all. How can they understand an actor who expresses feelings, sentiments, attitudes, reactions unknown to them and untranslatable in terms of their old and conventional way of living? And especially when they do not know Spanish? Cantinflas' humor or wit is mainly in his language. Chaplin did not speak, Chaplin had good scripts and good directors; Cantinflas has not had them yet. By his physique, clothes, and gestures Chaplin belonged to no special country and so could belong to any one; Cantinflas in his features, movements, and way of dressing is typically the man of our city streets with Spanish and Indian blood. Chaplin acted in the do- main of poetry; Cantinflas acts in the human one. In his domain, the Anglo- American actor expressed through his mimicry sentiments common to all men; in his, the Mexican player expresses psychological traits so new, so unclassified, so unanalyzed till now, that it is difficult for foreigners, and especially for Europeans, to understand them. Mario Moreno, the actor who has created "Cantinflas," giving thus to Spanish America the first generic type it has ever had, was born in Mexico City thirty-four years ago, of Spanish, French, and Indian descent. His father, a postman, sent his son to the Law University, but young Mario preferred to join a traveling tent theater, in which he created a sort of clownish tramp. The actors in Mexico's variety theaters carry on dialogue with the public; Mario's retorts were so snappy and witty that he soon became popular. But the five Mexican dollars that he earned daily were not enough for the ambitious youth: he became a lightweight boxer and traveled about the country, challenging whoever was willing to measure strength and agility with him. While he was on his way to a champion- ship, his former employer asked him to join the company again, offering him fifteen pesos a day. He accepted the offer, and it was in this second part of his career that chance put him on the way to fame. One day he had to substitute for the announcer and improvise an ad- dress to the public; panic-stricken, he stuttered, stammered, hesitated and was at such a loss to find the needed words that he resorted to every possible sentence or slogan that came into his head. The crazy speech was a hit. Six years later, as a movie actor, he was earning 250,000 pesos a year, a sum that by now he has greatly surpassed.

Cantinflas, el hombre más popular en toda América Latina; el actor que provoca grandes audiencias riendo a carcajadas para que sea difícil escuchar lo que dice a continuación; el mexicano que atrae tanto al hombre de la calle como al intelectual más sofisticado; el joven criollo cuya imagen en madera, cartón o estaño, como juguete o pieza de conversación, se muestra al sur de la frontera en mil escaparates como Batman o Superman en los Estados Unidos; él en quien los latinoamericanos reconocen por primera vez la encarnación de sus características más sobresalientes y sutiles: Cantinflas no ha logrado divertir a los franceses. En Cannes, donde se mostró su película Los tres mosqueteros para el concurso de cine, los críticos no solo no se divirtieron, sino que se preguntaron cómo podía divertir a medio continente. No nos maravillamos de su asombro. Sabemos de dónde viene: en Europa saben poco de América, nada de América Latina. Nosotros, que durante más de un siglo hemos absorbido la cultura europea, y especialmente la literatura francesa, no hemos tenido literatura para exportar capaz de despertar la curiosidad de los franceses sobre nosotros. Han tenido algunas nociones vagas y estereotipadas sobre nuestros millonarios, los "rastas"; sobre el hombre salvaje, "le bon sauvage"; y, aún más vagamente, sobre nuestros vaqueros. Eso es todo. ¿Cómo pueden entender a un actor que expresa sentimientos, sentimientos, actitudes, reacciones desconocidas para ellos e intraducibles en términos de su forma de vida antigua y convencional? ¿Y especialmente cuando no saben español? El humor o el ingenio de Cantinflas está principalmente en su idioma. Chaplin no habló, Chaplin tenía buenos guiones y buenos directores; Cantinflas aún no los ha tenido. Por su físico, ropa y gestos, Chaplin no pertenecía a ningún país especial y, por lo tanto, podía pertenecer a cualquiera; Cantinflas en sus rasgos, movimientos y forma de vestir es típicamente el hombre de las calles de nuestra ciudad con sangre española e india. Chaplin actuó en el dominio de la poesía; Cantinflas actúa en el humano. En su dominio, el actor angloamericano expresó a través de sus sentimientos de mímica comunes a todos los hombres; en el suyo, el jugador mexicano expresa rasgos psicológicos tan nuevos, tan no clasificados, tan analizados hasta ahora, que es difícil para los extranjeros, y especialmente para los europeos, comprenderlos. Mario Moreno, el actor que ha creado "Cantinflas", dando así a Hispanoamérica el primer tipo genérico que haya tenido, nació en la Ciudad de México hace treinta y cuatro años, de ascendencia española, francesa e india. Su padre, un cartero, envió a su hijo a la Universidad de Derecho, pero el joven Mario prefirió unirse a un teatro de carpa ambulante, en el que creó una especie de vagabundo payaso. Los actores de los teatros de variedades de México mantienen un diálogo con el público; Las respuestas de Mario fueron tan rápidas e ingeniosas que pronto se hizo popular. Pero los cinco dólares mexicanos que ganaba diariamente no eran suficientes para el ambicioso joven: se convirtió en un boxeador ligero y viajó por el país, desafiando a quien estuviera dispuesto a medir la fuerza y la agilidad con él. Mientras se dirigía a un campeonato, su antiguo empleador le pidió que se uniera a la compañía nuevamente, ofreciéndole quince pesos por día. Aceptó la oferta, y fue en esta segunda parte de su carrera que la oportunidad lo llevó a la fama. Un día tuvo que sustituir al locutor e improvisar una dirección al público; Aterrado por el pánico, tartamudeó, tartamudeó, dudó y se sintió tan perdido al encontrar las palabras necesarias que recurrió a todas las oraciones o eslogan posibles que se le ocurrían. El discurso loco fue un éxito. Seis años más tarde, como actor de cine, ganaba 250,000 pesos al año, una suma que ahora ha superado en gran medida.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The concept of discrimination plays roughly the same role in public debate as the concept of terrorism. In just the same way as disliked militants are often condemned as ‘terrorists’, so disliked policies that differentiate among people are often condemned as ‘discrimination’. Those charges have deep rhetorical power. However, both concepts remain woefully unanalyzed. In this article I want to analyze the concept of discrimination: what it is, and what it isn’t.

Differentiating among people on account of their group membership, disadvantaging some and not others, is not the problem with discrimination. We don’t discriminate against criminals by burdening them with jail. It is when disadvantages are unjustly imposed because of group membership that differentiation between groups is morally objectionable. This is what we call discrimination.

Intentionally disadvantaging innocent people merely because of their group membership is the clearest form of discrimination. (Perhaps people can also be discriminated against unintentionally, but that likely originally derives from intentionally disadvantaging members of that group.) Doing so strikes at the core of how we think people should be treated. Basic respect for persons entails regarding them as individuals with a right to equal consideration, not just judging them according to others with whom they happen to be grouped. So it might seem that disadvantaging someone for that reason is necessarily wrong.

We sometimes do intentionally disadvantage innocent people based solely on group membership, in cases where it does not seem wrong to do so. Airline pilots must retire at a certain age. You must be at least eighteen to vote. When one can get married, drink alcohol, join the military, or sign contracts, are similarly restricted. Insurance rates are established by group membership, not by individual characteristics. Of course, these are not the sort of groups commonly recognized as being victims of discrimination. But the salient point is that sometimes there are good reasons to sort and burden people merely because of their group membership. So how do we tell when group membership is a good reason to burden someone, and when it isn’t?

Take ten year olds. Not all ten year olds lack the maturity, judgment and experience to drive or vote, but the odds are that any individual among them does. It’s a matter of probabilities. Given that we can’t easily test every ten year old, restricting their rights solely on account of their age seems reasonable. So there is a plausible connection in this case between group membership and why a particular burden is imposed. By contrast, if someone’s group membership is irrelevant to why they’re being disadvantaged, that seems a bad reason. If a bus company refuses to hire black people just because they’re black, this is a bad reason because skin color is irrelevant to bus driving. Gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, and national origin, are all similarly irrelevant to bus driving, too.

Graphic © Amy Baker 2019. Please visit instagram.com/amy_louisebaker

Digging Deeper

Disadvantaging people when their group membership is irrelevant appears to explain both what discrimination is, and why it is wrong. However, this account of discrimination is still uninformative because it doesn’t address the question of what counts as an irrelevant reason. Or I could say that everybody, including discriminators, agrees that we should impose burdens for relevant reasons only. We just disagree about what counts as a relevant reason. In a racist community, for example, skin color becomes terribly relevant. So the ‘irrelevant reason’ account of discrimination is still too abstract. It doesn’t explain what is distinctively morally problematic about discrimination.

We might think that discrimination is objectionable because it disadvantages people on account of an immutable characteristic – some aspect of themselves that they cannot change. This ignores the fact that we can also discriminate against people for things they can change. Even if people could change their sexual orientation, by, say, taking a pill, it would still be wrong to discriminate against gays. Moreover, if discrimination is wrong because it disadvantages people for features they cannot change, this suggests that that feature is somehow objectionable. It gives the impression that if they could change it they should, but since they cannot, it is wrong to disadvantage them for, as it were, being stuck with something they can’t do anything about. However, it is not the case that it is wrong to discriminate against a woman because she cannot change her gender (sex-change operations aside). Whether or not she can change gender is beside the point.

Perhaps discrimination is wrong because it violates an intuitively obvious principle of justice – that we should treat likes alike. Since all humans share their humanity, all humans should be treated alike. The formal notion that ‘we should treat like cases alike’ is unassailable; but as with the ‘irrelevant reason’ account of discrimination, this idea is also uninformative, since the question of what counts as a ‘relevant difference’ resurfaces. The discriminator readily agrees that he should treat like cases alike: he just regards features such as skin color, gender, etc as differences sufficient to make the people involved not alike.

It’s not discrimination to lock up a criminal.

Clearly, thinking that a difference among people is relevant does not make it so. Even the discriminator knows that. Indeed, it would be unintelligible to disadvantage, say, black people, just because they are black; or to treat women worse than men just because they are women. Even discriminators understand that treating people disadvantageously solely because of skin color or gender etc is as incomprehensible as doing so just because of the number of letters in their names. Rather, the discriminator takes another step: he regards the trait in question as a marker for some other relevantly objectionable feature, such as incompetence, untrustworthiness, or inferior moral status. For this reason, the discriminator believes he does no wrong by imposing comparative disadvantages on people because of their group membership. In fact, he thinks he’s treating people as they deserve because of their group membership because of this negative feature that he associates with that group membership.

We tend to overlook the rationality that intentional discrimination requires and psychoanalyze instead: ‘homophobic’, ‘prejudiced’, ‘biased’, ‘bigoted’, ‘selfish’, ‘hateful’, and similar diagnostic terms come to mind. But such ad hominem critiques fail to address the discriminator or his discrimination perceptively, since he would deny he’s doing anything wrong. He thinks he acts justifiably. He thinks that he’s doing the same thing we do when we prohibit ten-year-old kids from driving or voting, or when we restrict application to the military to those under thirty, or, indeed, when we shun a bar in a high crime area of town late at night – that is, when there actually is some good reason for disadvantaging someone solely on account of group membership. We might regret that, as a practical matter, we cannot test all ten-year-olds to see who can drive safely or is mature enough to marry, vote, or sign a contract. But just as we think we’re justified in prohibiting all ten-year-olds from driving, so the discriminator thinks he is justified in disadvantaging women, black people, homosexuals, Jews, etc, since being a member of one of the groups he excludes means having some further objectionable feature or defect that justifies the treatment – even though he might concede that there will be a few individual exceptions.

An exception to the norm

Image © Bofy 2019. Please visit worldofbofy.com

Achieving Accurate Stereo Vision

When called upon to justify (even to himself) the burdens a discriminator imposes on people because of their group membership, he must appeal to an alleged fact that, if correct, would indeed justify the disadvantageous treatment. Were this not the case, the discriminator could not even understand his own actions. That is, since the discriminator imposes disadvantages intentionally, he has to know why he is doing so. However, since the discriminator is mistaken about the facts and judgments (moral or otherwise), he harms people mistakenly, and therefore unjustifiably. They do not deserve his maltreatment. This is why discrimination is wrong.

Stereotypes are generalizations which can be more or less accurate; in fact the difference between prohibiting all ten-year-olds from driving and unethical discrimination turns on the difference between accurate and misinformed stereotypes of the salient groups. If black people really did spread dangerous diseases in the community swimming pool, that would be a good reason to exclude them; if many homosexuals really did sexually exploit children, that would be a good reason not to allow them to be teachers; if most immigrants really were rapists and drug dealers, that would be a good reason to keep them out of the country; and if women really were incapable of making good judgments, then that would be a good reason not to, for instance, let them drive.

Inaccurate but firmly embraced stereotypes or faulty judgments are not easily corrected by facts or argumentation – although in theory they should be, since the discriminator takes himself to be rational. However, since discriminators embrace defective views regarding the people against whom they discriminate, despite good reasons to the contrary, they are now subject to a second kind of moral criticism. How we form and maintain our beliefs is itself a moral issue because what we believe affects others, and because believing contrary to good evidence and arguments is beneath our dignity as rational deliberators.

Have I perhaps over-intellectualized discrimination? Maybe it’s just a groundless, free-standing hatred or dislike for people in a particular social group. But if I hate, am disgusted by, fear, or distain, I must have corresponding beliefs about the object of my emotions. I must think that the object of my hate or disgust merits my opprobrium; if I am afraid, I must believe that the object of my fear can harm me. So when discriminators are simply urged to abandon their hate, fear, etc, they no doubt find the advice question-begging: Why abandon emotions I rightfully hold?

No. The real issue for discriminators is whether the disadvantages they impose on account of group membership are warranted; and that turns on the validity of their beliefs about the target group.

But what if the disadvantage is based on statistically verifiable facts? Employers favor non-smokers because they are sick less often than smokers; low income drug addicts are more liable to be petty criminals; skin-heads are more prone to violence; the guy with the rebel flag on his pickup truck is more likely to be a racist; people who drive Priuses are more likely to be political liberals; and so on. With stereotypes which have some basis in the facts, the odds are that any individual in the group will have or lack the trait in question. Most women lack the upper body strength to be firefighters. But some do have it. Most ten-year-olds are not capable of being good drivers. But some are. If we disadvantage someone because of a statistically-correct group norm, but who nevertheless is an exception to the norm, we treat that person unfairly. That person does not deserve the burden we impose, even if others in the group do.

However, this is different from imposing burdens on individuals because of false beliefs or incorrect judgments about the group. If we disadvantage someone who is an exception in a stereotype with some basis in fact, it seems to me not discriminatory. It is unfair; and we should try to address unfairness if we can. But not all unfairness counts as discrimination. Discrimination is a particular kind of unfairness, which turns on imposing burdens because of factually misinformed stereotypes.

We can also wonder why certain stereotypes have become somewhat accurate. If prior discrimination produced a stereotype with some basis in fact – such as disadvantaging immigrants leading to greater poverty among them, leading to higher crime rates – it hardly seems fair to appeal to the stereotype as grounds for further disadvantaging members of that group.

Let’s say discrimination involves the imposition of disadvantages on the basis of misinformed stereotypes. This account can be generalized to also include cases of defective (or at least wildly improbable) theories regarding certain groups where evidence about the target group plays a limited role. This can often happen in religious objections to homosexuality, same-sex marriage, the status of women vis-à-vis men, and the like. Generally, the discriminator with misinformed stereotypes is in theory amenable to empirical data, whereas this type of religious discriminator is not. His basis for treating members of the target group disadvantageously is not based on empirical evidence. But here too the burden of proof is on the discriminator, since he has to think that the disadvantage he imposes is reasonably warranted.

Perhaps you might think the moral ideal is to judge people as individuals with specific characters and abilities, not as members of groups. But this may be psychologically unrealistic and is often impractical, so in practice we function socially with stereotypes of varying degrees of accuracy. Further, since social identity presupposes various group memberships, and because it makes no sense to imagine individuals without some sort of social identity, ignoring group membership is more than a practically unrealistic ideal, it is a fiction. We do not live in a state of nature as abstract individuals independent of social groups. So instead of trying to ignore this fact, we should acknowledge that the ethical issue is how group membership of one sort or another may legitimately be handled in dealing with individual persons

0 notes

Text

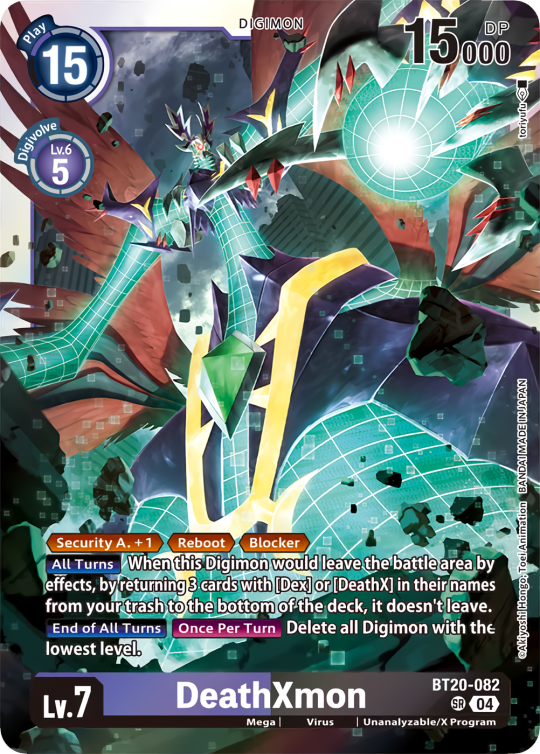

DeathXmon BT20-082 by toriyufu from BT-20 Booster Over the X (BT19-20: Special Booster Ver.2.5)

#digimon#digimon tcg#digimon card game#digisafe#digica#デジカ#DCG#BT20#DeathXmon#toriyufu#digimon card#Lv7#color: purple#color: black#type: virus#trait: unanalyzable#trait: X program#num: 04

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

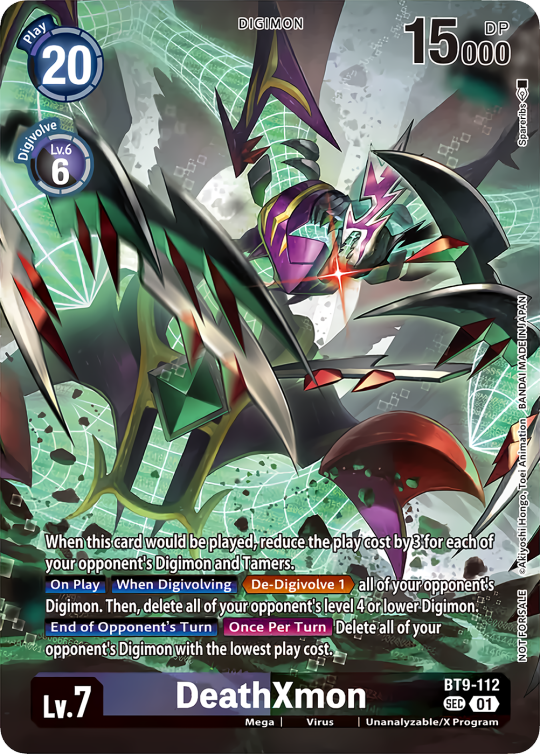

DeathXmon BT9-112 Alternative Art by Spareribs from Digimon Card Game Special Limited Set [E] / LM-02: Limited Pack DeathXmon [J]

#digimon#digimon tcg#digimon card game#DCG#デジカ#digica#digisafe#LM02#BT9#LM#DeathXmon#AA#Spareribs#digimon card#Lv7#color: purple#color: black#type: virus#trait: unanalyzable#trait: x program#num: 01

44 notes

·

View notes