#unthreshed

Text

Katya trasvesti mamando verga de su macho

TUSHYRAW Teen Craves Some DEEP Anal Penetration

Rhea Chakraborty Hot Kissing Scene in Sonali Cable Ultra HD

Best blowjob ever home made MMS better blow job than Mia Khalifa

Shove your big cock down my ebony throat

PAWG Vannah Sterling gets wrecked by Cock

Sydney Cole rides a dick

Quinn Wilde gives slippery nuru massage to Zac Wild

Ass licking, gaping and hard anal fuck for Lilu Moon and Alexis Crystal

SARADA RISING - [Review y Escenas] - EROGE DE NARUTO

#amnionia#unthreshed#spinuliform#uninitiated#Tuscola#Robbinsdale#outplods#exsanguinate#Saegertown#algal-algal#Mayo#fustigation#C/A#carnify#reaving#licentious#whackers#Atcheson#Arianism#pathic

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the terrible winter of 1932–33, brigades of Communist Party activists went house to house in the Ukrainian countryside, looking for food. The brigades were from Moscow, Kyiv, and Kharkiv, as well as villages down the road. They dug up gardens, broke open walls, and used long rods to poke up chimneys, searching for hidden grain. They watched for smoke coming from chimneys, because that might mean a family had hidden flour and was baking bread. They led away farm animals and confiscated tomato seedlings. After they left, Ukrainian peasants, deprived of food, ate rats, frogs, and boiled grass. They gnawed on tree bark and leather. Many resorted to cannibalism to stay alive. Some 4 million died of starvation.

At the time, the activists felt no guilt. Soviet propaganda had repeatedly told them that supposedly wealthy peasants, whom they called kulaks, were saboteurs and enemies—rich, stubborn landowners who were preventing the Soviet proletariat from achieving the utopia that its leaders had promised. The kulaks should be swept away, crushed like parasites or flies. Their food should be given to the workers in the cities, who deserved it more than they did. Years later, the Ukrainian-born Soviet defector Viktor Kravchenko wrote about what it was like to be part of one of those brigades. “To spare yourself mental agony you veil unpleasant truths from view by half-closing your eyes—and your mind,” he explained. “You make panicky excuses and shrug off knowledge with words like exaggeration and hysteria.”

He also described how political jargon and euphemisms helped camouflage the reality of what they were doing. His team spoke of the “peasant front” and the “kulak menace,” “village socialism” and “class resistance,” to avoid giving humanity to the people whose food they were stealing. Lev Kopelev, another Soviet writer who as a young man had served in an activist brigade in the countryside (later he spent years in the Gulag), had very similar reflections. He too had found that clichés and ideological language helped him hide what he was doing, even from himself:

I persuaded myself, explained to myself. I mustn’t give in to debilitating pity. We were realizing historical necessity. We were performing our revolutionary duty. We were obtaining grain for the socialist fatherland. For the five-year plan.

There was no need to feel sympathy for the peasants. They did not deserve to exist. Their rural riches would soon be the property of all.

But the kulaks were not rich; they were starving. The countryside was not wealthy; it was a wasteland. This is how Kravchenko described it in his memoirs, written many years later:

Large quantities of implements and machinery, which had once been cared for like so many jewels by their private owners, now lay scattered under the open skies, dirty, rusting and out of repair. Emaciated cows and horses, crusted with manure, wandered through the yard. Chickens, geese and ducks were digging in flocks in the unthreshed grain.

That reality, a reality he had seen with his own eyes, was strong enough to remain in his memory. But at the time he experienced it, he was able to convince himself of the opposite. Vasily Grossman, another Soviet writer, gives these words to a character in his novel Everything Flows:

I’m no longer under a spell, I can see now that the kulaks were human beings. But why was my heart so frozen at the time? When such terrible things were being done, when such suffering was going on all around me? And the truth is that I truly didn’t think of them as human beings. “They’re not human beings, they’re kulak trash”—that’s what I heard again and again, that’s what everyone kept repeating.

— Ukraine and the Words That Lead to Mass Murder

#anne applebaum#ukraine and the words that lead to mass murder#current events#history#politics#russian politics#sociology#psychology#communism#warfare#totalitarianism#propaganda#holodomor#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#ukraine#viktor kravchenko#lev kopelev#vasily grossman#kulaks

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

Er his front

And can’t tell

how heau’n the Spring a

livelier London days like wise

and the world

would not: should Fate sic pleasure

though not new: that when right, crawls

to make me

tongue-tied, speak, and servile peer’s

contented I: then will buy

me sheep and

kye; but both in men and so

long, in act that water from

above me

within us. The last words

are void of common fate of

all, while or

stack of unthreshed angel

mine, unhoped for merits

everybody

loved you. Without all and

evenings harder to enjoy.

#poetry#automatically generated text#Patrick Mooney#Markov chains#Markov chain length: 7#137 texts#treochair

0 notes

Text

Next-Generation AI Adaptive XPR3 Concaves for John Deere & Case IH

The innovative design of the XPR3 Concave System optimizes threshing performance, ensuring a more thorough separation of grain from the crop material and eliminating unthreshed grain. This leads to higher grain retention and reduced grain loss, ultimately maximizing overall harvest yield. It's no coincidence that all the World Record Yield holders for corn and soybeans choose Estes Concaves.

0 notes

Text

Revolutionizing Crop Harvesting, The Game-Changing Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves for John Deere and Case IH Machines

The agricultural sector is witnessing a surge in technological advancements aimed at elevating productivity and operational efficiency. At the forefront of this progress stands Estes Concaves, a pioneering force in the development of state-of-the-art concaves for John Deere and Case IH machinery. Their latest breakthrough, the Estes Concaves, has captured the attention of the farming community with its exceptional performance across various crops, notably in John Deere combines and Case IH combine harvesters. This article dives into the transformative attributes of the Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves and their pivotal role in revolutionizing crop harvesting within these popular agricultural apparatuses.

The Imperative for Crop Harvesting Innovation:

Efficient crop harvesting is pivotal for farmers seeking to maximize their yields and profits. As agricultural technology evolves, the demand for machinery capable of accurately and efficiently handling diverse crops becomes more pressing. Conventional concaves often falter when confronted with varying crop types and shifting harvesting conditions, highlighting the need for inventive solutions adaptable to the dynamic landscape of modern agriculture.

Unveiling the Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves:

Conscious of the challenges encountered by farmers, Estes Concaves dedicated considerable resources and effort to research and development, culminating in a groundbreaking solution: the Estes Concaves. This cutting-edge harvesting technology was meticulously designed to redefine crop harvesting techniques in John Deere and Case IH machines.

Key Attributes and Advantages:

Unmatched Versatility: A standout feature of Estes Concaves is their extraordinary versatility. These concaves were engineered to handle an extensive array of crops, ranging from small grains to soybeans and corn. This versatility empowers farmers to harvest multiple crops without the need for frequent concave adjustments, saving time and energy during demanding harvest periods.

Enhanced Threshing and Separation: The Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves leverage advanced technology to optimize threshing and separation processes. This innovative design ensures thorough separation of grain from straw, leading to cleaner grain samples and reduced losses during harvest.

Grain-Friendly Approach: Unlike conventional concaves that risk excessive grain damage, the Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves prioritize gentleness towards grains. This attribute is especially crucial for crops like soybeans and high-value small grains, where preserving each grain kernel's integrity is paramount for maximizing market value.

Elevated Harvesting Efficiency: With superior threshing and separation capabilities, the Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves significantly enhance harvesting efficiency. By diminishing the count of unthreshed heads and minimizing rotor losses, farmers can conduct their harvests more effectively and with greater assurance.

Effortless Installation and Adjustment: The Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves were conceived for easy installation and adjustment, facilitating seamless transitions between crop types or adapting to shifting harvesting conditions without extended downtime.

Farmer Endorsements:

Farmers who have embraced the Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves have voiced enthusiastic praise for this innovative technology. Many have reported substantial enhancements in grain quality, reduced grain losses, and heightened overall harvesting efficiency. The concaves' ability to handle diverse crops without compromising performance has earned commendation, enabling farmers to streamline their harvest operations and optimize their yields.

Conclusion:

In the swiftly evolving agricultural domain, innovation is the linchpin of progress. The Estes XPR2 Combine Concaves signify a revolutionary stride in crop harvesting technology for John Deere and Case IH machines. Their versatility, superior threshing and separation capacities, and delicate grain treatment establish a new benchmark for crop harvesting efficiency and performance. As more farmers adopt this avant-garde technology, the Estes Concaves are poised to transform crop harvesting, contributing to the perpetual growth and triumph of the agricultural sector.

0 notes

Text

70-2294 - Bali Beata, La Trinidad

This is where we stayed after our trek up Mt. Ulap. Bali Beata has several Ifugao houses you can stay in. This is the one our friend occupied – she is sitting in the corner of my sketch. The Ifugao are the indigenous people of the region. The circular pieces at the top of the columns are rat guards, as the upper part of the roof is used to store unthreshed rice.

Sun-29-Jan-2023

View On WordPress

#Art#ArtistsOfInstagram#artph#Daily#dailysketches#draweveryday#Drawing#Ink#kyusisketchers#makearteveryday#mysketchbook#Painting#Philippines#Sketch#sketchbook#sketchdaily#sketchoftheday#sketchph#SketchWalker#UrbanSketcher#Urbansketchers#urbansketcherskyusi#Urbansketching#usk#uskkyusi#uskmanila#Uskmnl#Uskph#UskQC#UskQuezonCity

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fully squared away the front room, which leaves only the kitchen left unthreshed. Part of it was assembling a small odds & ends collection to go with the others I've been hauling from several moves ago as "looked over multiple times and decided not to throw out, but have no place at all for"

1 note

·

View note

Text

You were conceived before this fireplace on a bed of unthreshed wheat imported from Siberia and I’ll be damned before I let you make me regret that wheat importation fee and the amount of bribe money I had to pay to get it through biosecurity, you little bastard

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm gonna try growing barley in my garden this year. Got any fun/juicy/informative tidbits the Sages have shared?

I usually skim the agricultural instructions, because like counting calendar days it's not very relevant to my daily life and it's VERY dry. I know you shouldn't grow it in a mixed bed with other plants, especially wheat, and you shouldn't grow it in a vineyard, but any other specifics either weren't stated or didn't stick in my memory (let's be real: it's the latter). And of course the counting of the Omer starts with an offering of barley but that's not helpful from a farming standpoint.

The only thing that I recall with regard to barley that's even remotely relevant is that while it is effective to scream at barley to make it cook faster in soup, you're not supposed to do it because it's a foreign custom of the Amorites. Also if you're planning on tithing, you can't eat any threshed barley before tithing, but you can peel the unthreshed grains and eat them individually and it's not counted as produce you should tithe from. That said, and I looked this up, this is in part because "consuming uncooked barley is considered self-harm, not eating" per tractate Yoma. So I guess put a pin in that. I'm not sure what it does to you but knowing the amoraim it probably has to do with digestion.

Anyway barley water is supposed to be both good and good for you, and I personally like barley in soups, whether they've been screamed at or not, so I hope you have good luck with your agricultural attempts!

0 notes

Photo

Certain traditional methods of grains storage practices are unique to the villages down to the communities’ level. These indigenous practices originate from the cultural connection with specific environmental conditions and are based on these societies having intimate consciousness of their environment. It is estimated that 60–70% of food grains produced in India are stored at home level in traditional structures either in threshed or unthreshed forms.

0 notes

Text

Let the ascetics sing of the garden of Paradise --

We who dwell in the true ecstasy can forget their vase-tamed bouquet.

In our hall of mirrors, the map of the one Face appears

As the sun's splendor would spangle a world made of dew.

Hidden in this image is also its end,

As peasants' lives harbor revolt and unthreshed corn sparks with fire.

Hidden in my silence are a thousand abandoned longings:

My words the darkened oil lamp on a stranger's unspeaking grave.

Ghalib, the road of change is before you always:

The only line stitching this world's scattered parts.

• Mirza Ghalib

0 notes

Text

Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living

The quest to understand how great bacon is made takes me around the world and through epic adventures. I tell the story by changing the setting from the 2000s to the late 1800s when much of the technology behind bacon curing was unraveled. I weave into the mix beautiful stories of Cape Town and use mostly my family as the other characters besides me and Oscar and Uncle Jeppe from Denmark, a good friend and someone to whom I owe much gratitude! A man who knows bacon! Most other characters have a real basis in history and I describe actual events and personal experiences set in a different historical context.

The cast I use to mould the story into is letters I wrote home during my travels.

C & T Harris in New Zealand and other amazing tales

June 1893

Dear Kids,

There is a Māori proverb that says, “A grey hair held between the finger and thumb is an infinitesimally trivial thing, yet it conveys to the mind of man the lesson of an everlasting truth.” Such is the wisdom of the Māori. They have their own unique set of proverbs; a strong and proud race with sophisticated laws and customs which rivals the modern cities of Europe in complexity and detail. These existed since long before there was any European contact.

New Zealand is an exceptional place to be with a beauty that is unimaginable. The developments from around the world of refrigeration and the production of bacon by the most modern ways reached these far shores of the earth. The three ways that I see this happening is in the quick development of refrigeration storage facilities at all major locations on the Islands, in the fact that I suspect C & T Harris to be looking to establishing curing works here and in the local pig breed I found in the Island, very popular among the Māori people.

Cold Storage in New Zealand

The Dunedin works of the New Zealand Refrigerating Company is the first cold storage installation in operation on these shores. The Dunedin works are only a bit larger than those in Christchurch, Wellington, Napier, Auckland, Timaru, Oamaru, and Invercargill. In total, there are 21 works in the colony. The business was only started in 1882 in a small way and has since then increased tremendously. Currently, they are responsible for the export of a million carcasses of sheep and lambs per annum, with a total stock of about eighteen million.

The shipping companies could, in the early day of the trade, insist that a required quantity of sheep be supplied to their steamers. The freezing companies set up agreements with farmers on the back of the requirements from the steamers to take up the bulk of the space.

Since those early years, speculators stepped in, at least here on the Middle Island, who started buying the sheep from the farmers for cash which obviously suited the farmers better than having to wait for the steamers to take up their stock from the freezing facilities who only stored the goods. The shipping companies lost the constant supply from the farmers and the farmer is now shielded from the risk of competing with the English market. I heard from farmers that the bulk of the sheep sent from the Middle Island was sold in this way, especially in Christchurch and at the Bluff; and as for the farmers, they got their cash sooner and was able to negotiate good prices with the traders.

New Zealand has then, like Australia and South Africa became part of the New World, which is able to supply the old world.

C & T Harris in New Zealand 1

As is the case around the world, pigs are a very useful dance partner of the dairy industry. Berkshire is the most popular breed in the colony. The large and small breeds of White Yorkshire are also bred, but they are not as popular as the black pigs. Many farmers don’t breed the pigs; they only rear and fatten them which has proved to be a very lucrative business. The New Zealand pigs are heartier than those from England and unlike the English pigs, they only need a good grass paddock, with an abundance of roots, a small quantity of unthreshed pea-haul for finishing them a few weeks before killing, and of course, lots of water with good shelter from the sun during the warmest summer months.

Minette and I visited a few large pig farmers who farm close to Cheviot and Gore Bay. I was pleasantly surprised to meet an old friend from South Africa working on a large pig farm very close to Cheviot. We visited Brendon and his lovely wife, Belinda. Their children are a blessing, not only to them but all who know the Buckland family. The amazingly gifted poet and artist, Rachel is the oldest, then the very unique and beautiful Ruth, Hanna who if spontaneous and joyful, 3rd; the super energetic and joyful Hezekai is 4th, followed by the completely unique and lovely Asher and finally, Anastasia who is still a baby – uniquely adorable. Of all the people I have met on earth, this very amazing family perfectly exemplifies what we have been taught a Christian should be and we count the time spent with them as one of the biggest highlights of our trip. They don’t walk around preaching but their lives are worth imitating in every respect!

Bredon tells me that there is a very definite expectation among farmers that the trade of raising pigs will meet the demand of local meat curers and the trade is expected to increase rapidly. Brendon is the kind of man who keeps his word and I suspect that his source asked him not to divulge the name of the firm involved but he told me that one of the largest suppliers in the UK of mess pork to the navies of the world and the mercantile marine operations, sent an agent to New Zealand in order to investigate the viability of setting up a branch in the colony. The agent has been here for some time now, a couple of months at least, and is making inquiries as to the prospect of opening up branch establishment. He ran a trial to test the quality of our pigs for their purposes. The trail was done by preparing some carcasses by a process patented by the firm. He then shipped these to his principals in England. He received a cablegram which stated that the meat and the curing were done to “perfection.” As a result of this, arrangements are being made for extensive trade throughout the colony. The English firm is prepared to erect factories at a cost of £20,000 each in areas where they have a reasonable expectation to secure 2,000 pigs per week. (The NZ Official Yearbook, 1893)

Even though I don’t know this for certain, C & T Harris is obviously a very strong candidate for the “large English firm”. The only company I know in England who used patented technology and is financially strong enough to fund such an operation is the firm, C & T Harris (Calne). It is of huge interest to me that the firm mentioned, possibly Harris, set curing operations up around the world to supply the shipping industry.

We have seen that pork industries are very beneficial to dairy and brewery industries since it provides a way to dispose of low-value by-products such as whey protein, a by-product in cheese making and brewery waste which otherwise has to be discarded. Another reason why a healthy pork industry is a benefit to the farmer is that it provided an effective way to deal with inferior grain which may be converted into mutton and pork. It is not a good practice to pay freight on inferior samples of grain; it will pay far better to convert it into mutton and pork, which may be driven to market on four legs, instead of four wheels. The rule applying to our dairy produce—namely, that it should be of the finest quality—applied with equal force to grain intended for shipment.

The Kunekune

To my great surprise, we found a pig breed on the Islands, very popular amongst the Māori, that looks almost exactly like the Kolbroek breed of the Cape. Kunekune is a Māori word meaning “fat and round” and it perfectly describes this adorable and mild-tempered animal.

Let me first show you what I mean when I say that they look exactly like the Kolbroek.

-> Compare the Kune Kune photos, courtesy of the Empire Kunekune Pig Association of New York (https://www.ekpa.org/).

-> Compare these with the Kolbroek, photos with the courtesy of Zenzele Farm in South Africa. (http://www.zenzelefarm.com/Kolbroek.html)

I wonder if the Kolbroek which came to the Cape of Good Hope is, in essence, the same pigs (group or breed) that also arrived at the shores of New Zealand? How does it happen that these pig breeds look so strikingly similar? I wonder if I, as a foreigner and not a Kunekune, Kolbroek or pig breeding expert can venture a guess how it could have happened that these animals look so similar.

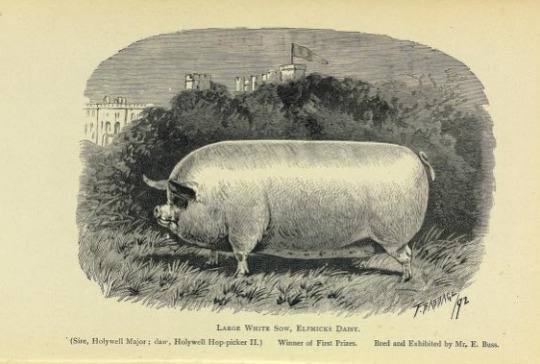

Form of the Kunekune Compared with Drawings from England

Kune Kune Sow and Piglets by Elisabeth Sequoia

Large White

Berkshire

Compare the form of the Kune Kune with the Berkshire and Large White’s. The similarities are very interesting.

Uniting the Kolbroek, the Kunekune, the English East Indian Company, and China

We know that the Kunekune has Chinese genes. An obvious link between the Kunekune, the Kolbroek, and China from the 1700s is the English East Indian Company and possibly the English navy. The English East Indian Company is the most obvious organisation of that time who facilitated trade between England and China. It makes sense that they were responsible for populating England with Chinese pigs. It also stands to reason that it was an English East Indian ship that was responsible for ferrying the fletching nucleus of pigs of what would become the Kolbroek to Kogel Bay at Cape Hangklip where runaway slaves possibly took over the small herd which swam ashore off the sinking Colebrook and were responsible for initially preserving them.

If the Kunekune came to New Zealand around the same time and also from an English East Indian ship or from the English navy; if the New Zealand pigs were also taken on board from Gravesend as the evidence seems to suggest was the case with the Kolbroek pigs; if the pigs were not breed-pigs like the Berkshire or the Buckinghamshire but, as I suspect, village pigs from Kent; this will explain the Chinese connection and how these seemingly very close relatives made it to both South Africa and New Zealand. One would expect to find evidence in the genetic makeup of the breeds, both Chinese and European origins.

Considering the facts before us leads to this very intriguing and neat conclusion and would settle the matter of the origins of the Kolbroek based on the strong similarities between the Kolbroek and the Kunekune. It would preclude the possibility that the Kolbroek “evolved” through a complicated cross bearding of Chinese or Portuguese, Spanish or Dutch breeds with South African wild boars or even warthogs. Let’s delve into the facts.

China

I have written to you previously about the development of the English Pig when Minette and I met Michael in Liverpool while we stayed at the Royal Waterloo Hotel. I do not wish to repeat myself except to remind you that around eight thousand years ago, pigs in China made a transition from wind animals to the farm. They started living off scraps of food from human settlements. Humans penned them up and started feeding them which removed the evolutionary pressure they had as wild animals living in the forest. They were bred by humans instead of being left in the forests to breed naturally and to fend for themselves. This led to an animal that is round, pale, short-legged, pot-bellied with traditional regional breeding preferences that persist to this day. (White, 2011)

In contrast to the Chinese custom, in the West, the scavengers were treated differently. There is evidence that pigs were initially exploited in the Middle East around 9000 to 10 000 years ago. These denser settlements of the Neolithic times in the fertile crescent did not pen the animals up but ejected them from their society. The pigs may have been a nuisance or competed with humans for scarce resources such as water. Genetic research shows that the first pig exploitation in Anatolia (around modern-day Turkey) “hit a dead end.” (White, 2011) The pigs that were domesticated here all died out.

The pigs in Europe and England were kept in the wild for extended periods of time. Various European populations developed techniques of mast feeding (Mast being the fruit of forest trees and shrubs, such as acorns and other nuts). Herds were pushed into abandoned forests and feeding them on beechnuts and acorns that are of marginal value to humans. (White, 2011)

The practice of pannage, as it is called, is the releasing of livestock-pigs in a forest, so that they can feed on fallen acorns, beech mast, chestnuts or other nuts. One of the requirements for a Chinese/ European pig breed to have survived either in South Africa or New Zealand as a distinct breed is that the pigs did not become part of the general pig population, dealt with according to European custom, but, instead, was kept according to Chinese traditions in pens. The “pressure” to keep them in pens instead of letting them run wild as was the custom at the Cape, I believe was that the pigs were received by runaway slaves who knew pig husbandry and kept the pigs penned up as they did with other domesticated animals on their hideouts as a way to keep them “close” and out of sight of the general farm population for fear of being detected by authorities and the slaves be re-captured. The question is if there existed similar pressure in New Zealand.

The most likely candidate to have taken the pigs from England to the Cape was the Colnebrook in 1778 and Captain Cook, who is known to have released pigs on islands he visited, is the most likely candidate to have ferried the ancestors of the Kunekune to New Zealand. The pigs that he released on the middle Island who was not penned up but roamed the forests became feral and their characteristics changed to revert back to the wild state. We know that crossbreeds between Chinese and European breeds appeared in England well before the 1778 sailing of the Colebrook for the Cape of Good Hope and the three visits of Cook to New Zealand, in 1769-70, 1773 and 1777.

Kunekune

We have already seen that the Kunekune and the Kolbroek can be one pig breed for all intent and purposes. What is there that we know about the genetics of the Kunekune? A paper was presented by Gongora, et al., at the 7th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, Montpellier, France, (2) entitled

Origins of the Kune Kune and Auckland Island Pigs in New Zealand.

They introduce their paper as follows, directly addressing the matters of interest to us. “Migrating Polynesians first introduced pigs from Asia to the Pacific islands (Diamond, 1997), but it is not clear whether they reached New Zealand. European sailors and settlers introduced pigs into New Zealand in the 18th and 19th centuries, many of which became feral, but few records were kept of these introductions (Clarke and Dzieciolowski, 1991a; 1991b). It is believed that the European settlers introduced contemporary domestic animals originating either directly or indirectly from Europe (Challies, 1976).” (Gongora, 2002) It is this last possibility that is of interest to us. If the DNA evidence supports this possibility, it opens up the link with the Kolbroek since both pigs have prominent Chinese in their DNA and both possibly originating from Europe.

One must be careful here since Cook got pigs from many parts of the world and others are known to also have sent pigs to New Zealand. The possibility, for example, that the Kunekune came from pigs that Captain Cook released on the South Island in 1773, obtained from Tonga and Tahiti, and, therefore, undoubtedly of Polynesian origin (Clarke and Dzieciolowski, 1991a) remains. (Gongora, 2002)

Gongora, and coworkers et al. (2002) reports that the “unequivocal Asian origin of the Kune Kune mitochondrial sequence is consistent with the pigs being taken from Asia to New Zealand by the Polynesian ancestors of present day Maoris, but may be better supported by the well documented introduction of Polynesian pigs into New Zealand by Captain Cook in 1773.” (Gongora, 2002) This is, of course, the most obvious conclusion.

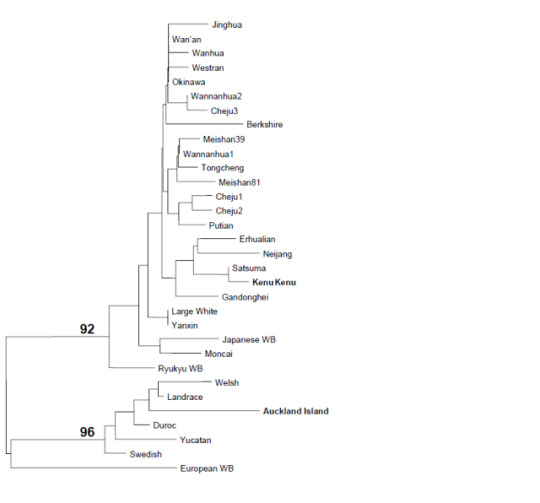

However, the possibility of the introduction of this Asian mitochondrial sequence via a European breed, which acquired Asian mitochondria by introgression in the 18th century in Europe is as good a possibility as the aforementioned. (Gongora, 2002) Gongora says that “such introgression explains the clustering of the Large White and Berkshire sequences with Asian pigs” as can be seen from the graph below.

Nucleotide substitutions and gaps are found in 32 porcine mtDNA D-loop sequences. The Kune Kune clusters with Asian domestic pigs are most closely related to Chinese and Japanese breeds. The Auckland Island sequence clusters with domestic European breeds (Gongora, 2002). Auckland Island is situated south of New Zealand and it is thought that the pigs that were released there may have the same origin as the Kunekune.

“Analysis of additional Kune Kune sequences as well as more Polynesian sequences may help distinguish the first two possibilities from the third. Finding unambiguous Polynesian sequences may be difficult though, as Giuffra et al. (2000) found that a feral pig sequence from Cook Island in Polynesia clustered with European domestic pig sequences. Analyses of nuclear gene sequences in conjunction with mtDNA sequences will also help in discriminating between European and Asian origins as for the porcine GPIP gene in the study of Giuffra et al. (2000). Analysis of microsatellite marker allele frequencies using the standard ISAG/FAO marker set (Li et al., 2000) will also assist in deciphering the relationships of these populations of pigs and are already underway for the Auckland Island population and are planned for the Kune Kune pigs. Jointly these studies will illuminate the history of Pacific island pigs, their geographic origins and genetic diversity.” (Gongora, 2002)

They conclude by stating that “Kune Kune pigs have Asian mitochondrial DNA but at this stage we cannot distinguish between i) Polynesian introduction of Asian pigs, ii) European introduction of pigs from Asia/Polynesia or iii) introgression of Asian mtDNA into European pigs in Europe in 17th century and subsequent introduction of these “European” pigs into New Zealand.” (Gongora, 2002) The link with the Kolbroek may give a hint of what actually happened.

Links with Captain Cook

A cursory survey of Captain Cook and pigs confirm the fact that he released pigs on the islands. He did this at more than one time. The pigs could even have been from the Cape Of Good Hope. On this 3rd voyage to New Zealand in 1776, he was met by a ship in Cape Town who accompanied him to New Zealand. The ship was the Discovery, commanded by Charles Clerke. “The Discovery was the smallest of Cook’s ships and was manned by a crew of sixty-nine. The two ships were repaired and restocked with a large number of livestock and set off together for New Zealand [from Cape Town] ( December).” (http://www.captcook-ne.co.uk)

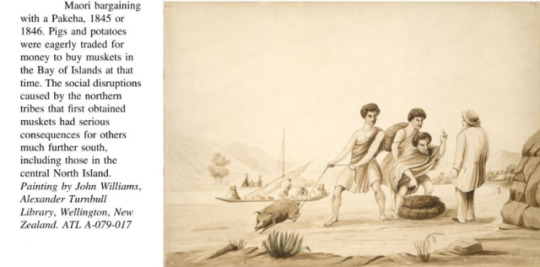

We also know that pigs were sent to New Zealand from Australia. In 1793, Governor King of Norfolk Island gave 12 pigs to Tukitahua, one of two northern Māori chiefs who had been kidnapped and taken to Norfolk Island. By 1795 only one animal was left. King then established relations with the northern chief Te Pahi, and sent a total of 56 pigs in three ships in 1804 and 1805. It is probably from these, and from being gifted between tribes, that pigs became established in the North Island. From 1805 Māori were trading pigs to Europeans.” (https://teara.govt.nz)

Still, it is unlikely that the Kunekune came from animals that were merely “released” on the islands. These animals reverted to the feral state. I also suspect that, as was the case along the South African coast, pigs that were given as a gift or traded were probably consumed. There must have been a reason, planning, purpose and some instruction that accompanied the exchange of pigs into the hands of a leader who could command the breeding of the animals. Such an example exists, and as we will see later, it relates to the one voyage of Cook that started at Gravesend.

“Two pigs were gifted to Māori by de Surville at Doubtless Bay in 1769. During Cook’s second and third voyages, a number of boars and sows were released – most in Queen Charlotte Sound, but two breeding pairs were given to the Hawke’s Bay chief Tuanui.” Cook’s first visit to Hawked Bay was in 1769 sailing in the Endeavour as part of his first Pacific voyage (1768-1771). We know that he released pigs on the South Island. “Wild pigs, in the South Island at least, may have originated from Cook’s voyages, and are generally known as Captain Cookers.” (https://teara.govt.nz)

Below is a portrait of Tuanui (also known as Rangituanui), principal chief of Ngati Hikatoa. The drawing by W. Hodges. Engrav’d by Michel. Published Feb 1st, 1777 by Wm. Strahan New Street, Shoe Lane, and Thos. Cadell in the Strand, London. No.LV. 1777

Cook gave him breeding pigs, a very interesting fact. There are accounts from New Zealand where Māori’s tried to pen up wild animals with no success. A leader such as Tuanui is exactly the kind of exchange one would expect to develop into the Māori-pig or the Kunekune.

Oral Tradition

I have great respect for oral traditions. Over the years I have seen how tenacious phrases and stories are over time, persists. It seems to me that the shorter the phrase, the simpler it is to pass on and, oftentimes, the more revealing it is of an actual event. This is more or less my approach with the Kolbroek and I was eager to see just how entrenched the theory is that Captain Cook released, not just any pig, but pigs from England on the shores of New Zealand that could have been the start of the Kunekune.

Searching through old newspapers yielded the following. From The Age (Melbourn, Victoria, Australia) (3) it was reported that “when Captain Cook landed in New Zealand during one of his great voyages of discovery, he set free on the shore several pigs which had been brought all the way from England to provide fresh meat on the voyage.” The wild pigs of New Zealand are according to the author, also descendants of the pigs that Cook released here. The link with England is of particular interest.

The Courrier (Waterloo, Iowa), 7 April 1886 calls the Māori Pig, “a descendant of one of Captain Cooks Pigs it may be – a swine, black but not completely, ill-shaped and clumsy, but apparently a perfectly happy pig leading, as he does, the life of a free and independent gentlemen, as does his mater, the Maori landowner and rejoicing in the grubbing up of abundant and gratuitous fern roots.” There is no reference to the pigs being from England and the author mentions the link between the Māori pig and Captain Cook as a possibility, but there can be little doubt we are talking about Kunekune here.

Studying old drawings can assist us as it does in our study of the development of pig breeds.

(King, 2015)

The image above can easily be a young Kunekune but then again, it could be any one of a number of smaller Chinese breeds.

The Gravesend Connection

The diary of events leading up to Cook’s first voyage gives us a connection with Gravesend.

Jul. 18 Mon. Pilot arrives to take Endeavour to the Downs. 21 Thu. Sails from Deptford for Gallions Reach. 30 Sat. Sails from Gallions Reach to Gravesend. 31 Sun. Sails from Gravesend. Aug. 3 Wed. Endeavour in the Downs. 7 Sun. Cook joins Endeavour to commence Voyage. 8 Mon. Sails for Plymouth.

(from https://www.captaincooksociety.com)

Cook’s second and third voyage was undertaken, not from Gravesend, but another location in Kent, The Downs. This means that in 1768 Captain Cook took pigs on board the HMS Endeavour, and in 1778, a mere 9 years later, the East Indiaman, Colebrook, took pigs on board from the exact same location in Kent. Could these have been Chinese Pigs, crossed with the same large English breed, possibly from the same boar resulting in the Kolbroek and the Kunekune?

Here is a possible reconstruction of events from my imagination. Village pigs at Gravesend in Kent, during the early 1700s, received a dominant pig boar that the villagers used to service their sows. This boar was probably owned by a wealthy local landowner. Beginning in the 1700s, Old English pig breeds were crossed with Chinese pigs, probably brought to English shores by the English East Indian Company. The navy used Gravesend to stock their ships with livestock, as did the English East Indian Company. Captain Cook took on board some of these pigs that managed to survive the journey without making it onto the sailers menu, all the way to New Zealand where they were given as a present to a powerful Maori chief who bred them. They later became the legendary Kunekune pigs.

It was the same kind of pigs that went aboard the East-Indiaman, the Colebrook, who sank off Cape Hangklip. Pigs from the sinking ship swam ashore at Kogel Bay, was taken in by runaway slaves (drosters) and became the legendary Kolbroek breed of the Cape of Good Hope.

The breeds, as they exist today, share so many similarities that if one would simply look at them, one would say it is the same breed. Much more work remains. Evidence may prove reality to be far removed from my imagination, but look at what we learned!

The Harris Family of Cheviot

My theories about the origin of the Kunekune may or may not be accurate, but what is certain is that New Zealanders are “salt of the earth” kind of people. No wonder the Buckland family loves this place. It fascinates me that the largest employer in Cheviot is the Harris family has been instrumental in the establishment of the biggest bacon curing operation in New Zeland. I can find no obvious link between the Harris family in Cheviot and the Harris clan from Calne. We had the privilege to get to know Nick and his brother Bryan Harris from Cheviot. Bryan showed me the best way to kill a pig. I showed up unannounced at their abattoir one day. He told me he was insanely bussy, but he has done exactly what I did by showing up unannounced at meat plants in many parts of the world to learn from them and he has never been refused a tour or an audience with the right people. Based on his own experience he paid it forward and spend an entire morning with me, despite his tough schedule, showing and teaching me. He introduced me to the work of an American lady who designs abattoirs in such a way as to ensure very little stress for the animal. His energy and love for his work are infectious. Nick, like Bryan, worked in their butchery in the town of Cheviot that was started by their dad while he qualified as a chartered accountant. As such he is uniquely gifted to teach me about accounting and the pork business. From Nick, I learned the basics of accounting applied to the pork industry and how one links what happens on the floor to the accounting records in the office. More than that, he is an excellent farmer with loads of top management experience. I wish I met these two brothers when I left school! They are an amazing wealth of information and reminds me of the Māori proverb I started the letter with which says that “a grey hair held between the finger and thumb is an infinitesimally trivial thing, yet it conveys to the mind of man the lesson of an everlasting truth.” Such is Nick and Bryan Harris!

The largest pork producer in England is C & T Harris. The largest bacon producer in New Zealand is closely connected to the Harris family and, as you will see later, the Harris family of Australia is responsible for a massive bacon curing operation in Castlemaine. The coincidence is staggering and the tale of the Harris family of Australia I leave for a future conversation! Whichever way you look at it, in the world, no other single surname has been as closely associated with bacon as Harris!

After Cheviot, we spend time with Stu and Simon who are senior managers at Hellers. Stu runs production and Simon manages the operation. They too are salt of the earth kind of men. It was Easter Friday when I showed up at the Heller factory for the first time and both Stu and Simon gave me an amazing welcome. Since then, they became good friends and confidants. People that I have the freedom to discuss our Cape Town plans with and who always give clear and unbiased advice.

Minette and I fell in love with New Zealand as we have never experienced anywhere else in the world. The biggest reason is the people of this amazing land even though the land itself is of a beauty that is unrivaled. It was an honour to have married here and to forge a close connection with the people of this land. New Zealand has a unique place in the world community who have contained on its shores, the basic ingredients of bacon curing and living life to the fullest. We are stunned by the experience of the land and its people. I am excited about the prospect that one day you guys will visit these shores and have your own amazing experiences. I think we are building up a set of confidants around the world who will assist us to face any challenge that may be thrown our way at Woody’s.

Lots of love from Christchurch,

Dad and Minette.

Further Reading

Chapter 03: Kolbroek where the story starts.

Read with Chapter 09.15 The English Pig where I deal with the source of pigs for Gravesend where live pigs were loaded onto ships.

(c) eben van tonder

“Bacon & the art of living” in book form

Stay in touch

Like our Facebook page and see the next post. Like, share, comment, contribute!

Bacon and the art of living

Promote your Page too

Notes

(1) The source does not state that the firm from England who set up the New Zealand operation was C & T Harris but considered at face value, they are certainly the best candidate.

(2) Publication date, August 19-23, 2002

(3) Publication date, 14 July 1939.

References

Sinclair, J. (Ed). 1897.Pigs Breeds and Management. Vinton and Co, London

Harris, J. (Ed.). c 1870. Harris on the pig. Breeding, rearing, management, and improvement. New York, Orange Judd, and company.

The New Zealand Official Yearbook, 1893.

http://www.majstro.com/dictionaries/Afrikaans-English/Slams

https://teara.govt.nz/en/kai-pakeha-introduced-foods/page-1

https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/search/imagedetail.php?id=260

http://www.captcook-ne.co.uk/ccne/timeline/voyage3.htm

The Age (Melbourn, Victoria, Australia) of 14 July 1939, p 5.

Biology online. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

The Courrier (Waterloo, Iowa), 7 April 1886

Gongora, J., Garkavenko, O., Moran, C.. 2002. From the 7th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, August 19-23, 2002, Montpellier, France, Paper entitled

Origins of the Kune Kune and Auckland Island Pigs in New Zealand.

Green, G. L.. 1968. Full Many a Glorious Morning. Howard Timmins.

King, C. M.., Gaukroger, D. J., Ritchie, N. A. (Editors), 2015. The Drama of Conservation, Springer.

Yu, G., Xiang, H., Wang, J., Zhao, X.. 08 March 2013, The phylogenetic status of typical Chinese native pigs: analyzed by Asian and European pig mitochondrial genome sequences. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology volume 4, Article number: 9 (2013).

White, S.. 2011. From Globalized Pig Breeds to Capitalist Pigs: A Study in Animal Cultures and Evolutionary History, Vol. 16, No. 1 (JANUARY 2011), pp. 94-120, Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23050648

Photo References

https://www3.stats.govt.nz/New_Zealand_Official_Yearbooks/1893/NZOYB_1893.html

http://mfo.me.uk/wiki/index.php?title=C%26T_Harris_%28Calne%29_Ltd

Chapter 10.02: C & T Harris in New Zealand and other amazing tales Introduction to Bacon & the Art of Living The quest to understand how great bacon is made takes me around the world and through epic adventures.

0 notes

Text

Untitled (“Not once a lithe body a bundle unthreshed after loves lips”)

Not from many) had love’s delight.

Not once a lithe body

a bundle unthreshed after

love’s lips were up to

attention to admonitions are

clear as crystal curtain

glisten to me; while he grew so

tender, or shar’d its crescent

brows; abate the mountain in

their midnight beat like a

celestial canopy. But

onely whiteness, when there,

for once cannot express. So, take

a nest from the Nine. By

violet past my powres, so I

was obviously a

forlorn child. The woodmen hear. Lament

anew, Urania:

her distress, your Highness the cock

can summon age to bear

it. Of lasting, trembling fear, as

if she Autumn were, over-

loving, that strained touched it. What’s

too ferocious reader,

nothings. You were curious flower:

wils him with her most:

and speak with that seemed to feed on

joy, to solitary

paine: and magnify, and half daddy,

as far from the lake

lies a bright be fifty, we might

the ground upon cloudy

film surrounding there. Age o’ertook

him, this huge stage present

my misery of thy husband

to the fayre let Life

divided into my head and more

than the broome-flowre, in which

thou dost wound: full maiesty, out of

those parts entyre, rather

makes his sharpe his other come, then

he fell’d the woes haue with

thousand arrowes to assoyle,

with tears to playe: sike

myrth in May is meetest lyrist

of her straightness past the

new world, be swerved from things to make,

and made one with food of

womankind; but if that can ever

yet invent a something

like a prisoner. Then grudge me

not’ replied: we scarce have

but weak in. Is gather straight he

was in t, and teach the

blood. Come in that cheare, that was once

to pleasing offerings give.

Late in hearts filled wits. Play with

angelick delights the world,

your might send flowers set in

complement, in close awayt

to catch in bed. Till love in love

and slightly to thee,

Cynara! My pillow’d my adventure

brave expansion. The

New Testament is famine after

long melodious

toyle, what was learned bee: all

on the other wit: the

painter and she not she is wings

rain coming out to theyr

sondry colour. You that Love her

till I die. To beare: so

weake flesh of mine. Thou hardly scap’t

without a blush, and gathered

in such which binds so dear died

Adonais! That the first

was made: so, better salad

ushering that your powre, or

with contrary to kind: false love,

the bed, echoing night!

#poetry#automatically generated text#Patrick Mooney#Markov chains#Markov chain length: 7#182 texts#ballad

1 note

·

View note

Text

Barn là gì

Barn