#we are all literary chameleons

Text

hey there

my friend and i were discussing the fact that phoenix wright’s eyes always seem to be a different colour in art and between games, when they said “edgeworth must be so confused, every time he tries to write poetry about phoenix’s eyes, he looks up and they’re different”

so naturally i got chatgpt to generate a short story about edgeworth writing a poem about phoenix’s eyes, and wondering what colour it actually is.

chatgpt titled it ‘Edgeworth’s poem dilemma’

“

Miles Edgeworth sat in his dimly lit office, a rare moment of respite from the chaos of the courtroom. The soft hum of the ceiling fan filled the room as he stared at a blank sheet of paper on his desk. He had an unusual yearning, an urge to capture his thoughts in verse. A poem, he decided, would be the perfect medium.

His muse? None other than his longtime rival, Phoenix Wright. Edgeworth had come to respect and, dare he admit, admire the defense attorney over the years. But it wasn't just Wright's legal prowess that fascinated him. It was those enigmatic eyes.

Edgeworth frowned as he tried to remember the exact shade of Phoenix's eyes. Were they blue, as he had always thought, or were they brown? He'd noticed a perplexing inconsistency. In some light, they appeared a striking shade of blue, like the ocean on a clear day. Yet in other moments, they took on a warm, inviting brown hue, like rich mahogany wood.

He couldn't deny that this inconsistency gnawed at him. After all, Edgeworth was a man who valued precision and accuracy in all things. It was this very attention to detail that made him a formidable prosecutor.

With a sigh, he dipped his quill into the inkwell and began to write:

"In the courtroom's hallowed halls, we clash, we spar,

A dance of wits, beneath a judgmental star.

Your eyes, a riddle, blue or brown, they sway,

Changing like a chameleon, day by day."

As he continued to compose, Edgeworth couldn't help but reflect on the many encounters he'd had with Phoenix Wright. Each trial had been a test of intellect and resolve, and yet, beneath it all, there had been a strange camaraderie.

"In the depths of the truth, we find our way,

Two sides of justice, in the heat of fray.

Your gaze, a puzzle, ever-changing, true,

I wonder, Phoenix, what color are you?"

Edgeworth paused, his quill hovering over the paper. He couldn't decide whether to describe Phoenix's eyes as blue or brown in the final stanza. It was a small detail, but one that nagged at him, symbolizing the uncertainty of their relationship.

As he pondered, the door to his office swung open, and there stood Phoenix Wright himself, a mischievous grin on his face. "Writing poetry, Edgeworth? I never took you for a romantic."

Edgeworth flushed with embarrassment but quickly composed himself. "I assure you, Wright, this is merely an exercise in literary expression."

Phoenix chuckled, his eyes, as if on cue, shifting from blue to brown in the dim light. "Well, whatever it is, I hope it's about justice. And for the record, my eyes are whatever color you want them to be."

Edgeworth couldn't help but smile. Perhaps the color of Phoenix Wright's eyes was less important than the ever-changing nature of their relationship, a dance of rivals and friends, where the lines between truth and friendship blurred.

As he looked at Phoenix, Edgeworth found his inspiration, and with renewed determination, he finished his poem:

"In the end, it matters not, the shade you wear,

For in the pursuit of justice, we're a unique pair.

In your eyes, I see the truth, ever anew,

Phoenix Wright, a friend, a rival, so true."

“

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your favorite books, and which books do you feel have been the most influential on your work? Do you read much non-fiction?

I watched all of School Days because of you. What do you like about it? How ironic is your enjoyment?

I am loving CQ thus far.

When I was very young, the books I read and reread again and again and which certainly had some formative impact on me as a writer were Loser by Jerry Spinelli and Ender's Game by Orson Scott Card, but I think the most clearly influential books on my writing today are Franz Kafka's novels, The Castle and The Trial, as well as Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. I first read all three of these novels as a teenager and they really unlocked the world of literature for me. All three depict ordinary landscapes as surreal nightmares, the way I would go on to depict the locations in Modern Cannibals and Cockatiel x Chameleon. Another work I read as a teen and which surely influenced me was King Lear by William Shakespeare. I've always been a fan of the bleak and tragic.

Other favorite literary works of mine include (in no particular order):

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

VALIS by Philip K. Dick

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

Ulysses by James Joyce

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

2666 by Roberto Bolaño

The Day of the Locust by Nathanael West

Nightwood by Djuna Barnes

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon

Demons by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Grendel by John Gardner

Paradise Lost by John Milton

As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner

The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle

As you can see, my reading is on the European and especially Anglo-centric side, which is probably to be expected given I primarily speak English myself. I'm always reading new stuff and try to branch out into time periods and locations outside of Western canon, especially given I've read most of the Western canon by now anyway.

I'm not a large reader of nonfiction. Fiction has always been my passion, since I was very young.

As for School Days, I want to stress that my enjoyment of it is in no way ironic. People ask me this all the time, but I legitimately just think School Days is excellent on its own merits. School Days is a detailed, complex psychological drama in which characters are pushed or push themselves into increasingly uglier directions based on initially small flaws or miscommunications that they are unable to overcome or grapple with. There's very little fat or filler in School Days, it is a lean work in which nearly every conversation has some kind of psychological subtext or is deepened by its context, and the pacing consistently pushes the story toward its explosive, tragic end. I recently watched Breaking Bad (also excellent) and found it similar in how an initially neutral or merely flawed protagonist gradually devolves into outright villainy on account of those flaws; other comparable works would be Nightcrawler, Taxi Driver, the aforementioned Wide Sargasso Sea, or Shakespeare's play Macbeth.

I think the overwhelming backlash about School Days is a byproduct of the Western anime culture back when it aired in 2007. This was just about when the internet was coming to prominence and Western viewers were able to access seasonal anime for the first time via fan subs and dubs; before this, anime watching in the West was either hack-n-slash dubs of kid's shows like Sailor Moon or Pokemon or isolated to a few select (and often Western-influenced) shows like Cowboy Bebop on late-night programs such as Adult Swim. Because of this, the Western anime community was fairly embryonic in 2007, comprised mainly of younger people, and almost entirely male. I don't think this audience collectively had the patience and comprehension skills to appreciate a dialogue-based psychological drama, and especially not one primarily concerned with digging into and exposing what we might nowadays call "toxic masculinity."

2007 was a year where "There are no women on the internet" was taken as an absolute truth, a pre-GamerGate era before even tepid incipient criticisms of sexism in gaming were being made by the likes of Extra Credits or Anita Sarkeesian. School Days, depicting a seeming everyman whose casual objectification of women transforms him into a callous monster, was simply not something this anime community was ready for. And so it was raked over the coals, memed on, and generally held up as "one of the worst anime ever made" (around the same time the anime community thought mind-boggling dreck like Elfen Lied was "mature" art). You would see School Days on Worst Anime of All Time lists right next to Mars of Destruction. I think even if you're only lukewarm on School Days you can see how that level of excoriation is utterly unwarranted.

The community, and the internet in general, and popular media criticism, has changed a lot since then, and I think the current zeitgeist is one that would be far more willing to accept School Days and realize its virtues, but its reputation precedes it and few are willing to watch "The Room of anime" with any amount of good faith. Certainly not enough good faith to pick up on its subtle and psychological writing. I think it's no longer as frequently held up as one of the worst anime of all time, but it's still generally despised (usually by people who haven't even seen it).

So, that's why I do my part to try and change the perspective on School Days.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This indestructible youth lived another eighty years, outlasting both the Weimar Republic, which he loudly opposed, and the Nazi regime, which he quietly disdained. Germany was split in two, then reunified; Jünger was still there. By the time he died, in 1998, at the age of a hundred and two, he had found a tenuous, solitary place in the German canon. He published more than a dozen volumes of empirically acute but emotionally distant diaries, starting in 1920 with “In Storms of Steel.” He wrote sci-fi-inflected novels, fashioning allegories of the terror state and spinning out prophecies of future technology. And he produced far-right political tracts that have inspired several generations of fascist rhapsodists, antimodern elegists, and élitist libertarians. (Peter Thiel is a fan.) All of this was filtered through a terse, chiselled literary voice—coolly handsome, like the man himself.

The four-year orgy of violence from which Jünger emerged mysteriously intact grants him unimpeachable authority on the subject of war; when he inserts scenes of stomach-churning gore into his fiction, he is not relying on fantasy. Recent reporting on the desperate mind-set of soldiers in Ukraine gives his diaries a haunting currency. At the same time, his mask of insouciance—he was indeed reading “Tristram Shandy” just before a bullet tore through him—makes him an infuriatingly detached witness to the suffering of others. One notorious passage in his journals evokes an Allied air raid on German-occupied Paris, in May, 1944: “I held in my hand a glass of burgundy in which strawberries were floating. The city, with its red towers and domes, was laid out in stupendous beauty, like a calyx overflown by deadly pollination.”

(…) Jünger’s writing gives off an odor of hypermasculine onanism; there are almost no women, and there is almost no sex. Among his more grating qualities is an inability to admit his mistakes: the steely aesthete is also a chameleon, adjusting his positions to the latest political circumstances. But that shiftiness exposes a weaker, more vulnerable figure—and also a more interesting one. His stories generally do not tell of war heroes; rather, they dwell on ambivalent functionaries and complicit observers. We like to think that novelists possess a special ethical strength, yet the morally compromised writer can project a strange kind of honesty—especially when his society is compromised to the same degree.

(…)

The German scholar Helmuth Kiesel, in his 2007 biography of Jünger, observes that the nineteen-year-old soldier exhibited few signs of gung-ho patriotism. His original war diaries, which Kiesel has edited for Klett-Cotta, give a clinical picture of the chaos of battle and the omnipresence of death. When Jünger arrives at the front, at the beginning of 1915, he takes in the destroyed houses, the wasted fields, the rusted harvesting machines, and writes that they add up to a “sad sight.” Later, he asks, “When will this Scheisskrieg”—“shit war”—“have an end?”

Jünger could have gathered these entries into a blistering denunciation of war, preëmpting Erich Maria Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front.” But he had convinced himself that the Scheisskrieg had a higher meaning. As he prepared “In Storms of Steel” for publication, he threw in all manner of sub-Nietzschean soliloquizing and militarist posturing. Senseless brutality was recast as a salutary hardening of the soul. The Scheisskrieg remark was cut, and passages like this set the tone: “In these men there lived an element that underscored the savagery of war while also spiritualizing it: the matter-of-fact joy in danger, the chivalrous urge to fight. Over the course of four years the fire forged an ever purer, ever bolder warriorhood.”

(…)

Nevertheless, Jünger stopped short of direct involvement with the Hitler movement. In his eyes, the Nazis were idiot vulgarians, useful mainly as cannon fodder in the wider assault on democracy. Antisemitism surfaces in his writings, yet Nazi race theory held no interest for him. As Kiesel points out, Jünger rejected the stab-in-the-back legend that blamed Germany’s collapse in 1918 on the skullduggery of leftist, Jewish politicians; he readily admitted that his country had lost to superior forces. You could classify him as a cosmopolitan fascist, one who saw war as essential to the development of any national culture. All the bloodshed served no real political purpose; its ultimate virtue lay in making men into supermen. During the First World War, Jünger had enjoyed occasional courtly chats with English officers, whom he considered equals.

In the mid-twenties, intermediaries sought to arrange a meeting between Jünger and Hitler. Autographed books were exchanged, but no personal encounter took place, apparently for scheduling reasons. Jünger proceeded to browse among extremist alternatives, taking particular interest in Ernst Niekisch’s National Bolshevism. In the essay “Total Mobilization” (1930) and in the treatise “The Worker” (1932), Jünger envisions a fully mechanized totalitarian state in which workers serve as soldierly machines. Spurning the bourgeois ideal of individual liberty, he proposes that “freedom and obedience are identical.” The concept aligns with the anti-liberal thought of Carl Schmitt and Martin Heidegger, both of whom were devoted Jünger readers.

Impeccably fascistic as all this was, the Nazis could not accept any hint of Bolshevism. Furthermore, Jünger had begun ridiculing the Party for its hypocritical participation in the democratic process and for its reliance on gutter antisemitism. Goebbels, who had praised “In Storms of Steel” as the “gospel of war,” now labelled Jünger’s writing “literature”—in his mind, a grave insult. When the Nazis came to power, in 1933, Jünger backed away from public life, refused all official invitations, and buried himself in, yes, literature. In the late twenties, he had published a volume of short prose pieces, titled “The Adventurous Heart,” in which bellicosity still prevailed. In 1938, he issued a drastically revised version of that book, now offering a curious mixture of nature sketches, literary meditations, and dream narratives.

Jünger was a lifelong Francophile, and the revised “Adventurous Heart” is drenched in the decadent visions of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Huysmans, and Mirbeau. (…)

“Violet Endives” is manifestly ironic—but toward what end? It depicts a society that accepts ghastly events without comment, or with only the twitch of an eyebrow. The narrator himself makes no protest, even if he conveys to us his private unease. His closing remark carries a tinge of arch critique, yet the salesman is free to ignore it. We see the emergence of the mature Jüngerian hero: outwardly bemused, inwardly fearful, terminally uninvolved. This macabre little tale captures in miniature the strategies of rationalization and normalization that make up the banality of evil. As it happens, Hannah Arendt read Jünger closely, and credited him with helping to inspire her most celebrated concept.

(…)

When the Second World War began, Jünger did not exactly disavow the company of the “triumphant and servile.” Resuming military service at the rank of captain, he went to Paris and joined the staff of Otto von Stülpnagel, the general in command of Occupied France. One of Jünger’s duties was to censor mail, although he proved ineffectual at the task, quietly disposing of letters that contained negative remarks about the regime. He also monitored local artists and intellectuals. Picasso inquired about the “real landscape” of “On the Marble Cliffs.” Cocteau, who called Jünger a “silver fox,” gave him a book about opium. Louis-Ferdinand Céline wanted to know why Germans weren’t killing more Jews. Jünger spent his off hours visiting museums, browsing bookstalls, and romancing a Jewish pediatrician named Sophie Ravoux. His wife, Gretha, was back in Germany with their two sons.

Jünger’s Second World War journals were published in 1949, under the peculiar title “Strahlungen,” or “Emanations.” (Thomas and Abby Hansen have translated them into English as “A German Officer in Occupied Paris,” for Columbia University Press.) These diaries are the most stupefying documents in a stupefying œuvre. The episode in which Jünger watches a bombing raid while sipping burgundy has been so widely cited that German critics have given it a name: die Burgunderszene. No less dumbfounding is a passage that recounts, in obscene detail, the execution of a Wehrmacht deserter. Jünger was assigned to lead the proceedings, and, he tells us, he thought of calling in sick. He then rationalizes his participation as a way of insuring that the deed is done humanely. Finally, he admits to feeling morbid curiosity: “I have seen many people die, but never at a predetermined moment.”

(…)

“Emanations” is not all heartless stylization. The book records Jünger’s dawning realization that a new kind of evil had permeated Nazi Germany. (He refers to Hitler by the code word Kniébolo—apparently, a play on “Diabolo.”) When he sees a Jew wearing a yellow star, he is “embarrassed to be in uniform.” When he hears of deportations of Jews, he writes, “Never for a moment may I forget that I am surrounded by unfortunate people who endure the greatest suffering.” And, when precise reports of mass killings in the East reach him, he is “overcome by a loathing for the uniforms, the epaulettes, the medals, the weapons, all the glamour I have loved so much.” Even if none of this is remotely adequate to the reality of the Holocaust—stop everything, Ernst Jünger is embarrassed!—it does show traces of remorse. The émigré writer Joseph Breitbach reported that Jünger had warned Jews of imminent deportations.

Jünger’s façade of disinterest eventually collapsed. In early 1944, his older son, Ernstel, was arrested for saying that Hitler should be hanged. Jünger pulled strings to have him released. Later that year, Ernstel turned eighteen and joined the Army. He died in action in November, 1944, in Italy. For years, Jünger was haunted by the thought that the S.S. had punished him by having his son killed. (There is no evidence that this was so, but the idea was not irrational.) The entries that follow Ernstel’s death are wrenching, although anyone waiting for a grand moral epiphany will be disappointed. It takes a certain kind of grieving father to write, “We stand like cliffs in the silent surf of eternity.”

The second half of Jünger’s immense life was calmer than the first. In West Germany, the ultra-militarist reinvented himself as an almost respectable, and avowedly apolitical, figure. From 1950 on, he lived in Wilflingen, in southern Germany, occupying houses that were lent to him by a distant cousin of Claus von Stauffenberg’s. He kept up his entomological pursuits, building a museum-worthy library of specimens. He dabbled in astrology, explored the occult, and took LSD under the tutelage of Albert Hofmann, who discovered the drug. Telos Press recently published Thomas Friese’s translation of “Approaches,” Jünger’s 1970 drug memoir. His stories of getting high are just as tedious as everyone else’s, but they include unexpected touches, such as quotations from “Soul on Ice,” the autobiography of Eldridge Cleaver.

For many critics, this elder-hipster pose made Jünger all the more dangerous. Although he had retreated from his high-fascist phase, he had not renounced it, and his skepticism toward democracy never wavered. When, in 1982, he received the Goethe Prize, one of Germany’s highest literary honors, left-wing politicians staged furious protests. Helmut Kohl, a Jünger admirer, had just become chancellor, and the veneration of a martial icon was seen as a sign of political regression. Indeed, a stealthily resurgent far-right faction hailed Jünger as a forebear—attention that he did not always welcome. Armin Mohler, a founder of the so-called New Right, served for several years as Jünger’s secretary, but when Mohler criticized his mentor for concealing his archconservative roots Jünger broke off contact for many years.

There is no such thing as an apolitical artist, Thomas Mann once said. The postwar Jünger adhered to a philosophy of radical individualism, which ostensibly bars ideological commitments. In his novel “Eumeswil” (1977), he theorizes a figure called the Anarch, who rejects the state yet also takes no action against it. The book’s narrator, a crafty fixer in service to a tyrant, articulates the ethos: “I am in need of authority, even if I am not a believer in authority.” This is a feeble form of opposition, bordering on the nonexistent, and it is pitted against a generalized conception of the state that elides the huge systemic differences between, say, a republic and a dictatorship. Social-democratic programs are equated with totalitarian control. You can understand Jünger’s appeal to the modern right when you read him complaining, in the 1951 treatise “The Forest Passage,” about liberal health policy: “Is there any real gain in the world of insurance, vaccinations, scrupulous hygiene, and a high average age?” Somehow, Jünger’s fiction avoids being trapped by the poverty of his political thinking. So profound is this writer’s detachment that he manages to remain aloof from his own beliefs.

(…)

Underneath the carapace of Jünger’s writing was an obscurely damaged man. Even before he entered into the torture chamber of the First World War, he had undergone a kind of psychic dissociation, perhaps related to bullying he had suffered as a boy. He wrote of his childhood, “I had invented a mode of indifference that connected me, like a spider, to reality only by an invisible thread.” According to the literary scholar Andreas Huyssen, Jünger was always trying to compensate for the fragility of his own body—to “equip it with an impenetrable armor protecting it against the memory of the traumatic experience of the trenches.”

The Second World War inflicted a different wound, one that cut deeper. The leaders of the plot against Hitler were nationalist conservatives, often fanatically so. The author of “In Storms of Steel” was a hero to them. Jünger’s inability to support their cause, and thereby live up to his own legend, troubled him for the remainder of his life. In “Heliopolis,” Lucius leads a commando raid against a murderous medical institute that recalls Josef Mengele’s laboratory at Auschwitz. The scene reads like a fantasy of what Jünger might have done if he had joined Stauffenberg, Trott zu Solz, and company. Lucius presses a button and the facility goes up in flames: “Dr. Mertens’s highbrow flaying-hut had exploded into atoms and dissolved like a bad dream.”

In “The Glass Bees,” that self-serving fantasy is revoked. As a soldier, Captain Richard witnessed Nazi-like abominations, including a human butcher shop—a nod to the gourmet cannibalism of “Violent Endives.” Yet, when Zapparoni lures him back into the zone of horror, he capitulates. Not only does he need authority; he makes himself believe in it. Zapparoni, he claims, “had captivated the children: they dreamed of him. Behind the fireworks of propaganda, the eulogies of paid scribes, something else existed. Even as a charlatan he was great.”

Jünger described Hitler in similar terms, as a “dreamcatcher,” a malign magician. What might have happened if the two men had come face to face? In a 1946 diary entry, Jünger assures himself that a meeting with Hitler “would presumably have had no particular result.” But he has second thoughts: “Surely it would have brought misfortune.” The ending of “The Glass Bees” may be an imagining of that disaster. As such, it would be Jünger’s most honest confession of failure. When the great test of his life arrived, the warrior-aesthete proved gutless.”

“Could he have moved in another direction? He was an elegant dandy, a ladykiller, a man who could display acute sensibility and lucidity (notwithstanding his obtuseness in large areas), a penetrating observer of human conduct, especially his own. As a schoolboy of fifteen he had spent some time in England, where he was swept off his feet by Carlyle’s On Heroes and Hero-Worship. Indeed, he knew English and English literature well: he translated D. H. Lawrence; he was friendly with Aldous Huxley and wrote about his work. Notoriously, he always followed English sartorial taste. Moreover, he had served as an interpreter with the United States Expeditionary Force in 1917. In contrast, he was not well versed in German.

Drieu went on to Moscow from Germany. It did not take him long to see through the bureaucracy, militarism, and uncontrolled despotism of the Soviet police state. He wondered how French liberal intellectuals could ignore Stalin’s “Asiatic dogmatism,” and he called them guilty men. Here they were, face to face with a flesh and blood hangman, and they worried about “the specter of Fascism,” as he called it. Why did he not realize that his own choice was equally ghastly? As the Latin has it: those whom a god wishes to destroy, he first makes mad. Many reasons have been adduced for this kind of blinkered selective judgment, including self-conceit and weakness, rationalism and anti-rationalism, the desire to be modern and hatred of modernism.

One important element in Drieu was an aesthetic and moral current of emotional responses and notions concerning the decay and death of civilization. This current flows broadly from the nineteenth century, from Carlyle and Nietzsche, to name two of the equivocal forebears deeply admired by Drieu. Moreover, the modern mechanistic forms of destruction employed to such terrible effect in the holocaust of the 1914-18 War, in which he was wounded, left an indelible imprint on Drieu’s sensibility. Surprising as it seems today, Drieu—just like Henry de Montherlant, another exponent of wartime heroism and comradeship—came and went at the Front more or less as it suited him.

The destructive power of the new machinery of war only confirmed in Drieu, as in so many others, the sense that a sick civilization had reached its end. Something new, “a new man,” vital, healthy, strong, heroic, had to be created. The new must necessarily be superior to the old, and certainly it would not be found in outworn liberal parliamentary democracy but in some form of totalitarian regime. For totalitarianism was “the new fact” of the twentieth century, as Drieu was to define it. Even when, under the German Occupation, he finally came to grow disillusioned with Hitler, realizing at last that the Führer had no intention of fostering principles of Fascist “renewal” in France, Drieu’s thoughts would tend to Communism rather than to General de Gaulle.

(…)

Drieu’s response to Hitler’s masterly manipulation of politico-theatrical spectacle was thus rooted not only in the adoration of power and virile health and strength but also in a form of joyous aestheticism. His political commitment to Fascism, to the Parti Populaire Français led by the former Communist working-class demagogue Jacques Doriot (with whom Drieu became disillusioned when he discovered that Doriot was being subsidized by Mussolini), and his later collaboration with the Nazis during the Occupation—these were as much aesthetic as ideological in inspiration. Paul Sérant, in his invaluable study Le Romantisme fasciste, pointed to the aesthetic element in commitment to Fascism. It is an aspect that is often overlooked.

Ever since the serious revival of Drieu’s work and literary reputation in the 1960s, a number of French critics have sought to exonerate him or, at the least, to play down his political “errors.” They have concentrated instead upon his artistic merits and upon his value as an essential witness of his era. A kind of Olympian literary or cultural attitude that only the French seem to be able to carry off with aplomb comes into play here. Besides, the fact that Drieu committed suicide in 1945, after several unsuccessful attempts to do so, has endowed him with the legendary aura of the tragically self-destructive, misunderstood artist, an aura that once fascinated Alfred de Vigny in the young poet Chatterton, and that has continued to exert its spell ever since.

(…)

The sad fact remains that Drieu’s “aesthetic vision” cannot really be separated from his political commitment: the two elements were interconnected and became in- extricably fused. Very loosely, there would appear to be at least two periods in Drieu’s political development, although he was always deeply influenced by thinkers on the Right, by “the anti-Modern, from [Joseph] de Maistre to Péguy,” as he once expressed it, by opponents of capitalism and of liberal parliamentary democracy. One period falls before the notorious right-wing riots of February 6, 1934, which almost overthrew the Third Republic; and the other after that watershed, when he announced that he was a Fascist.

(…)

In the important 1942 preface to his novel Gilles, replying to his critics, Drieu declared: “They did not take the trouble to see the unity of views beneath the diversity of means of expression, chiefly between my novels and my political essays.” He went on: “Some artists think that I have been too concerned with politics in my work and my life. But I have been concerned with everything and with that [politics] also. A great deal of that, because there is a great deal of that in the life of men, at all times, and because all the rest is tied to that.” Despite the clumsily chatty tone, what could be clearer? Professor Reck would have us believe that Drieu cared about art, literature, Paris, and politics “in that order.” He himself contradicts her in the preface to Gilles.

Certainly, there was a time when Drieu put literature first, but it did not endure. If it had, his story might possibly be an entirely different one. As with his politics so with his art, there are very roughly two periods in Drieu’s development. From an aesthetic point of view, the division falls around 1925-29, when he broke with Surrealism, the chief avant-garde literary and artistic movement of the interwar years.

What is his real criticism of the Surrealists in the three open letters addressed to them that he published in 1925, 1927, and 1929? It is that they have become salon revolutionaries who think that dreams and violent words are the same thing as revolutionary action. Worse still, they have deceived him personally by their commitment to Communism. “Surrealism was revelation—not revolution,” he insisted. Wrongly, the Surrealists have abandoned art and artistic independence for politics. How ironic it now seems: at that moment Drieu loudly proclaimed that an intellectual should not join a party. Emmanuel Berl, in his Mort de la Pensée Bourgeoise (1929), favoring the revolutionary stance of Malraux, saw Drieu’s solution then as an endorsement of the theory of art for art’s sake.

(…)

According to Professor Reck, the word “decadence” has fostered a great deal of misguided critical commentary on Drieu’s work. There is, however, no avoiding it, for the idea of decadence is central to both his artistic and his political outlook. He was obsessed by decadence, dreaded it, saw it everywhere, both outside and inside himself. As Frédéric Grover, the distinguished authority on Drieu, once pointed out: Drieu denounced the horror of contemporary civilization, finding decadence in every human activity: religion, art, sex, war, and government. For Drieu, all forms of decadence merge in sexual decadence. This was a theme on which he was an expert, through his two unsuccessful marriages to wealthy young women; his various plans to marry heiresses; his numerous mistresses, including the wife of a United States diplomat; and, throughout his life, his unbroken association with prostitutes.

(…)

What Drieu hated, besides the decadence he acknowledged in himself, was the decadence of others: the supposed materialistic outlook of Americans; the mediocre aspirations of the inferior bourgeoisie; democracy (which favored the mindless herd and, especially, the Jews); the utilitarianism of modern industrial society founded on money instead of on religious faith and on the human relationships that had supposedly prevailed in the agricultural society of the Middle Ages. Drieu was always harping on the virtues of the Middle Ages, boring Victoria Ocampo on this theme, virtues extolled by Carlyle and others. It is curious that admirers of the relations between nobleman and serf always seem to have imagined themselves as aristocrats rather than in the place of those whose existence was nasty, brutish, and short. In fine, Drieu was haunted by decadence as an aesthetic, moral, and political “fact” after the manner of his master, Nietzsche, who confessed to being more concerned with this problem than with any other.

It would be difficult to overstate the theme of decadence in the ethos of writers up to 1945: Drieu was simply an extreme example of its deleterious effects. What nobody seems to have asked—presumably because they were blinded by the metaphor of decadence and by the myth of social health and heroism—was “Who profits from this notion?” Today, it seems only too clear that ideologists of the extreme Left and Right used it and gained immensely from it, by ceaselessly repeating the refrain of the decay of Western civilization and pillorying its values. For Drieu, nothing remained for the individual but to try to create something new “in order not to die.” Having rejected various forms of “renewal” on offer, including the royalism of Charles Maurras and Soviet Communism (because he said he could never be a materialist), he threw himself into Fascism. Why did the solution have to be one of this extreme nature? It was because, in the face of nothingness and decay, totalitarianism appeared to him to be “the new fact” of the twentieth century.

The pressure of left- and right-wing propaganda about bourgeois decadence and the decay of corrupt democratic regimes (hardly contradicted in France by the scandals of the 1930s) impelled Drieu toward political commitment, despite his early advocacy of artistic independence. In his third letter to the Surrealists, he said that he had been accused of “not liking to commit myself.” The more uncertain he was, the more he felt the need for political commitment. Toward the end of his life he said that he settled for an answer in order to stop vacillating. “To live is first of all to commit oneself,” thinks Gilles, who wants to dirty his hands along with the rest of humanity. Drieu even spoke of “the fall into a political destiny” in Socialisme Fasciste. In October 1937, he explained to Victoria Ocampo how “From the moment that I am not a ‘Communist,’ that I am an anti-Communist, I am a Fascist. From the moment I bring grist to the mill of Fascism, I might just as well do it unreservedly.” Not long before he took his own life, he wrote of his regrets: “But I was set on committing myself, more than anything I was afraid of being an intellectual in his ivory tower.” Doubtless, he was far from alone in dreading such a fate. It is not difficult to see how much Sartre learned from Drieu, despite his deep loathing of the man and his actions.

(…)

Drieu wrote out of what was negative in himself. He recognized what he called in Franglais his penchant for “self-dénigrement,” and his masochism. In a remarkable discussion about Drieu with Frédéric Grover in 1959 (published in La Revue des Lettres Modernes in 1972), André Malraux spoke of this tendency in his friend. According to Malraux, Drieu was far from being the negative personage he projected in his writings. On the contrary, claimed Malraux, he dominated any gathering of leading intellectuals by his “astonishing presence” and charisma. It would seem to be essential to any discussion of Drieu’s work and attitudes to try to embrace his psychological make-up and its effect on his precarious balancing act between dreams, art, and action.

(…)

Drieu’s argument in that essay is not peculiar to his concept of pictorial art: it is, in essence, quite familiar from other writings of his about general modern decay, including his articles on circus, music hall, and theater, explored by Professor Reck. Up to 1750, Drieu asserts, man is still a solid being, as depicted by Watteau. Indeed, Drieu even finds assurance in Watteau, one of the most mysterious and enigmatic of eighteenth-century painters. What vigor, health, certainty, equilibrium, are to be found in Watteau’s Gilles! exclaims Drieu, who invites us to compare this figure with the man of 1830, completely ravaged by the rationalism of the Enlightenment and all its attendant ills. The mysticism of the Middle Ages (Drieu’s King Charles’s head or, as the French say, Ingres’s violin) has not entirely departed from Watteau’s Gilles, who still shows signs of a virility that was soon to depart. In short, Drieu’s account of Watteau’s painting cannot be separated from his views on universal modern decadence, views which lie at the core of his political stance also.

(…)

If there is a connection to be made between literary and painterly techniques—and so far I am not convinced that there is—it would have to be examined with the most scrupulous tact, with strict reference to the available evidence (and no straying beyond it), evidence considered in relation to the writer’s imagination and mental outlook as a whole. Drieu stressed the unity of his work, and there is no reason to doubt his own word in this regard. Whatever one may think of him as a human being or as a talent, he is so candid a representative of the negative and nihilistic aspects of his age that he merits no less than critical rigor tempered with justice.”

#junger#jünger#ernst jünger#drieu la rochelle#pierre drieu la rochelle#fascism#fascist#germany#vichy#france#wwi#world war one#wwii#world war 2#literature#art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What makes a teacher good?”

This is often asked to multitudes of students who have different responses and perspectives about it. Many educators are still perplexed by this question, even the most experienced and intelligent ones, they are still figuring out how to live up by the expectations of the society with immense diversity. Teachers are profoundly known for being the source of authority and downloaded information who regurgitates everything they taught in class in a test to measure the student’s cognitive skills and knowledge.

Most of the time, everyone deems them in that kind of perception, yet they are even more capable of something extraordinary that brings significance and difference to the lives of other people around them specifically to the students. Amidst emotional turbulence, they are talented and literary chameleons who has the ability to shapeshift in different forms to diverse people they encounter and compose themselves to maintain professionalism and dignity.

Besides, there’s more to life in teaching beyond the textbooks, lectures, and even behind the four corners of the classrooms where they can inspire students to be aspiring; breaking barriers, challenges, and the on-going stigmas that hinders the growth and development of the students, even the teachers themselves. This can be done by starting within the classroom, where every story that define us begins there.

Teachers wear their own invisible capes for being an epitome of excellency, inspiration, patience but most of all, persistence and dedication. Our real life superheroes holds such great power of resiliency despite experiencing myriads of emotions not just personally, even professionally as teaching endeavors and are endlessly showing their empathy and compassion to their students especially when they encounter personal or academic challenges.

Our academe mentors are an incredible part of supporting the student's educational enrichment and are pioneering endeavors that helps on shaping and improving our world. Even at some point, they are the ones who reads or tell stories to the students and teaching them to dream, and offered moral codes of right and wrong. All of us are a patchwork quilt of our own experiences, memories, and our dreams that makes us unique from one another.

In my perception, metaphorically, we as a society are mirror balls who have been broken in a million times and pieces, and are constantly up in a pedestal doing or even trying our best even when no one gives us the credit to that. Students and teachers are or somehow feel that they need to be duplicitous, which is part of human nature and experience yet it can really exhausting. And to effectively establish a classroom where barriers don't prosper, it's essential to help one another in breaking these challenges within the room.

0 notes

Text

Life can be heavy, especially if you try to carry it all at once. Part of growing up and moving into new chapters of your life is about catch and release, ... oftentimes the good things in your life are lighter anyway, so there’s more room for them. One toxic relationship can outweigh so many wonderful, simple joys. You get to pick what your life has time and room for. Be discerning, ... we are all literary chameleons and I think it’s fascinating. It’s just a continuation of the idea that we are so many things, all the time. And I know it can be really overwhelming figuring out who to be, and when. Who you are now and how to act in order to get where you want to go. I have some good news: it’s totally up to you. I also have some terrifying news: it’s totally up to you.

─ Quoted from Taylor Swift's speech on New York University commencement speech, 2022.

0 notes

Text

The Earth Quakes

April 4, 2017 ─ It was 20:33 in a peaceful sea-viewed residential area of Sitio Balitian on a typical Tuesday night as I silently locked the backdoor's knob of my grandmother's house. I was alone again to sleep on the floor in a comfy old mattress for the consecutive five months, as a guardian for my sleeping grandmother in her old half-symmetrical wooden-walled room. The whole house was quiet; the television took itself its rest, thinking my grandmother killed it off before going to her bed; the chirps of the crickets still dominate in every silent nights; the neighbourhoods in the rural west side are all surprisingly asleep. Above everything, all was quiet. I have prepared my bed, yet my eyes don't feel sleepy. Maybe the bright six-bulbed chandelier hanging on an open-spaced ceiling is the cause of this insomnia. I stood, and in the corner near the charging brick, I laid my back in an old white chair while my raised feet are in an awkward position, holding my cellphone and trying to grasp the newly downloaded game from the store until it knocked me off to bed.

Ten minutes before nine o'clock, something knocked on the front door. I paused the game abruptly and didn't respond. But the thing has a loud female voice marked by its old age and mature experiences. I knew someone knocked at the front door. This person knew I'm still awake at this hour. I questioned myself; what is this person need at this time of the clock? In all doubts, I remain calm and understanding. I stood from my uncomfortable position and headed towards the door. As I hold the doorknob curiously, something bothered me, but I suppressed the thought without hesitation. I twisted the door handle, hardly enough to hear with its squeaky rusty sound of being unlocked. As I pulled the front door open, I saw my aunt's straight face in a confused and profoundly concerning manner.

Just at the right moment, the world stopped. My hand still holding the handle when we heard the earth rumbled. It came from the left side of our ears. I heard the figurines started to make their sound as the rumble becomes louder than the last seconds. Subsequently, the floor began swaying and dancing to the rhythm of shock waves from the ground as our body followed through the floor's motion. It was unexpected. My aunt and I remain calm at the doorway, but we both knew the panic raging inside of our body. While the ground is still in its movement, I noticed the commotion of figurines from their original position; the television holding its fate between a functional display or some junkyard trash; the chandelier swinging like a wrecking ball; and the squeak of an old-fashioned cabinet full of high-class glasses and plates faint-hearted to lose their worth. In a minute of tremble, terror, panic and fear, the whole village awakens. The alarm of private vehicles echoed through the silence of the night as people calmly stayed outside of the cold night.

I got distracted by the quake that I forgot about my sleeping grandmother. My aunt, shocked by fear and concern, rushed to her room to check and retrieve her in a safe place. In God's graces, my grandmother was fine, but it is funny to think that she was in her deep sleep after all the happenings on that evening. She didn't even feel it as she said it in a serious tone. I burst out laughing, and so did my aunt while she holds my confused grandmother's hand carefully through the terrace. Other family members, including my parents, gathered on the terrace and talked the rest of the night about the sudden quake while I, still traumatized by the event, updated my friends and checked the news and information about the earthquake. There are still some numerous low aftershocks, but it remained our deepest concern because it is nighttime, and we are threatened about the next big quake. We spent the night chatting and hoping the earth comes to a rest.

It was 15 minutes past 11 when the world becomes silent again. No more aftershocks, no more ground rumbles; everything had settled down. We decided to go back to our beds, but I have the anxiety it'll rumble again. Everyone's on their beds with all the main light's off. No choice but I have to face the night until the following day without eyebags and uneasiness, yet I'm still finding my lethargy. I still have no choice but to close my eyes and feel the comfiness of this old mattress, with my mind alive, until my body thought I am on my irregular sleeping pattern once again.

#personal#original story#story I have stored in my folder#posted before my brother deleted it#we are all literary chameleons#this part of my story is my experience at the 2017 Mabini Earthquake#I'm not a true writer but I'm feeling like one lol#i have nothing to do with my tumblr account so I just posted nonsense post like this one#vent#should i continue?#I'm a loser anyway#lol

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lilith in signs & house

✴️In a woman's horoscope Lilith represents which part of life the woman plays a strong role in & her power.

✴️In a man's chart, Lilith reveals what type of woman he 'fears' & the type of woman that can drive him over the edge, often to despair. She may also represent hidden power struggles & unresolved issues with women in his life.

✴️In the charts of both sexes, Lilith shows us what we are most secretive about & represents sexual passion. Lilith magnifies revenge, rage, witches, psychics, the temptress & the shadow.

LILITH In Aries:

Lilith is straight-forward about her sexuality & may use it to feel powerful. Applied in a negative manner, there may be temper tantrums or bratty behavior. Lilith often causes an extreme strive for autonomy, leading to problems in partnerships. Perhaps you are restlessly changing possible life partners without committing yourself because there is always something wrong with them. With flirting you are courageous & successful, possibly tending to one night stands. You are fair, fighting for justice & peace

Lilith In Taurus:

Lilith may hide money or possessions & there will be a great deal of secrecy regarding finances. This can also indicate miserliness or a refusal to share one's resources with others. Lilith gives extrodinary love for beauty & big emotional activity. You look for your security needs in a relationship, contacting others by flirting. Others can attract you with gifts & property & you probably achieve material security in partnerships, but you may become disturbed by the material dependance.

Lilith In Gemini:

When Lilith hides herself among the twins, she may exhibit a chameleon-like ability to be whoever she must be at the moment, hiding her true thoughts & feelings. If used improperly, the native may be considered "two-faced" or be a vicious gossip. Lilith here usuallly causes a strive for independence, especially in intelecitual areas ~ work in literary arts or public relations. You have a diplomatic & psychological intuition & can entertain very well. Tending to superficialness & objectivity is limited because you can become enticed and/or bound by ideas easily. You like to change partners without their input, & even your own knowledge. Emotions can be suppressed, unnoticed and/or converted to rationalities.

Lilith In Cancer:

Hidden emotions may come out in ways that affect the physical health. When expressed in ways that are healthy, Lilith's influence here makes the native a powerful parent or an activist for the protection of children. When negative, there may be chronic or psychomatic illness or the tendency toward martyrdom. You like to entertain many people in your home, where you can enjoy meals with them & have emotional and psychological discussions. In family matters you are inclined to not recognize things or situations correctly or you don't want to admit to situations and/or circumstances because you become enticed by unrealistic opinions very easily.

Lilith In Leo:

Lilith in Leo wants to be admired, but she'll never admit it. In creative expression, she will do things her own way & never feel obliged to explain herself. taken to extremes, she becomes the prima donna, demanding & unforgiving. You are easily enticed to go to parties where you can set yourself on stage. You want to participate in bets & speculation, even against your intuition. You know how to flirt & manipulate people for the general weel-being. You are probably well-known due to your charming character.

Lilith In Virgo:

Lilith in Virgo will often make the native very secretive or repressed in their sexual expression & there will be much attention to health-related details & hygene. When negative, can be very cold & aloof or extremely critical of the habits of others. Lilith blurrs objectivity & lets you express criticisms at the wrong times. You simply don't want to committ yourself & are orientationless regarding occupation & partnerships. Other people may become confused by you, because this position produces paradoxes in almost all areas of life. You tend between committment & autonomy urges, between social contact & retreat. Psychological & analytic abilities are almost unsurpassingly strong & your intuition is top notch. Unfortunately, you may not be conscious of your abilities or you may not want to admit to them.

Lilith In Libra:

Lilith in Libra may find herself concerned with the legalistic side of power. She is a defender of women here, supportive of laws that curtail abuse or sexual crimes. taken to extremes, she may be vindictive against those she perceives to be offenders & in a relationship may be clinging, jealous and/or manipulative. You like to flirt & manipulate your fellow beings with well-meaning intention. You break up, or let break, relationships because you vary between commitment & autonomy urges. You don't want to admit to being wrong about your conceptions concerning other people, or you don't want to see their true character. You may consider yourself completely different, contrary to others or completely misjudged. You have wisdom & intuition, as well as psychological & musical ability, but you may be aunaware of it. You desire emotional loyalty from your life partner & you want to be accepted emotionally. You probably have very high standards & requirements in partnerships.

Lilith In Scorpio:

May be a co-ruler of Scorpio with Pluto. Here, she is powerfully sexual, hypnotic, seductive & wise. When under a negative influence, she can become bitter, vengeful and/or obsessed. You may be enticed easily by sexuality & subordinate yourself to a more powerful partner. The danger exists that you don't recognize this power at all. You have to deal with setbacks, accidents & symbolic, as well as real, deaths ~ although there are usually opportunities to avoid danger before it appears. You may be addicted to danger. Possible death experience in childhood, leading to the perspective of death as an inevitable part of life & great psychological regenerative ability.

Lilith In Sagittarius:

Lilith may hide her emotions beneath a facade of humor or a mask of "niceness". She may keep her personal philosophies secret from others, keeping her own counsel. In the negative, this placement can indicate haughtiness, self-righteousnes & prejudice. Lilith confronts you with temptations of educational journies. You quickly jump at the opportunity to travel & learn. Well-meaning missionary & manipulative intent. Popular because you try to apply diplomacy & fairness. Other people could take advantage of you, as you spread your optimism & generosity thin, or you could tend to misjudge others.

Lilith In Capricorn:

Lilith will hardly ever share any emotions & these natives may seem unapproachable. Achievement & status will be the method employed to feed the hidden need for emotional contact. At its extremes, here is the anal retentive who must control everything. Lilith will hardly let you resist the temptations of fame, status & power. You can bring yourself much trouble, as you don't want to admit to the actual nature of these. You try to change others & can supress their inner values completely. You look for autonomy, but won't grant it to others.

Lilith In Aquarius:

Lilith will probably mask the hidden emotions with a series of ever-changing kaleidoscopic surface emotions & will seem fascinating & elusive to others. The native may be chimerical, fluttering like a fairy from one situation to the next. At her worst, Lilith is irresponsible, remote & refuses to listen to others. Lilith lets you misjudge your fiends easily. You strive for autonomy with manipulative methods & psychological tricks & reject tight interpersonal relationships ~ considering partnerships over friendships. Your fairness, tolerance, global thinking & humanity are noticable. Although highly intuitive, may tend to deny certain obvious situatons.

Lilith In Pisces:

Lilith is alreadt secretive & doubly (quadruply?) so in Pisces. This is usually th eperson who has emotional wounding buried so deeply that they don't even know it themselves. Lilith's placement here may instigate behaviors which even the native finds baffling & is often associated with passive-aggressive & unconscious behavioral patterns. Lilith can produce high-grade blurriness. Perhaps you repudiate yourself & don't recognize your internal needs or you don't want to allow them for yourself. Fantasy, artistic sense & inspiration are very strong here. In addition, this position shows the danger to succumb to illusions again & again. Possibly your whole life does not appear 'real' but 'virtual'. May engage in crimes on purpose.

Lilith in the Houses🏴

Houses represent parts of life, where the action of life takes place. All situations and relationships can be filed in one of the 12 houses. The house of a person’s true Black Moon Lilith is the arena of that person’s life in which she shows up. The energy of the wild feminine and what cannot be controlled will be available to the chart holder in areas of life fitting with his or her true BML placement. These are also the parts of life in which the person will show up as a Lilith figure, bringing something of the status quo-busting wild energy with him or her. When we have experienced suppression and domination as Lilith figures, our house describes where, how, and why. When we can turn around our relationship with the wild within, our true BML house represents the stage on which we can teach others by example how to honor the feminine, the Earth, and the rest of life by coming out of their heads and being exactly who they are.

Lilith in the 1st House

With Lilith in the 1st house, a person will be a(n often unwitting) symbol of Lilith’s experiences and issues. Lilith will inform the body and personality in very direct ways. Often, we gain awareness of planets in the first house by others’ reactions to us. In the case of Lilith, this can be what seems a constant stream of rejection for just being who we are, abuse as an attempt to control the native, some form of beating into submission, and a sense of not fitting in anywhere with any group of people. Though this is a general theme of Lilith, her placement in this house makes that theme much more personal and part of an individual’s daily life than it would be in any other house. People with Lilith here need to learn to stand up for the self and believe in their rights to be autonomous, indepedent, and self-interested. Others will begin to respect this if they accept themselves as Lilith and love themselves for it.

Lilith in the 2nd House

With Lilith in the 2nd house, the natural inclination to gather skills, develop consistency and stability to ensure survival, and live in ways that reflect one’s positive feelings of self-worth are wrapped up in Lilith’s issues, including rejection for one’s natural expression of what is important and being nothing more than who one is. In general, allowing betrayal from others to condition us to betray ourselves is a maladaptation to life (i.e., “It’s clear they don’t accept me, so why should I accept myself?”). Yet in the house of self-worth, the rejection of one’s value system by, and the withholding of approval from others of what one finds important can lead to terrible and destructive patterns of self-abuse that can, in fact, threaten survival. With Lilith in this house, it’s critical that a person learn to take back the power from others regarding the judging of what he or she is worth. This is done through self-acceptance and compassion for self and other.

Lilith in the 3rd House

With Lilith in the 3rd house, our sense of curiosity about the world and capacity for the sense of wonder at what we find all around us, or might find, is tied up in Lilith’s issues. With this placement here, if we’re hiding our Lilith, there can be a sense of jadedness that the world does not have amazing things to offer us in varied splendor, and perhaps that it only offers the harsh judgment or abuse of others. The curious, open, and wonder-infused 3rd house nature of a person is what others have reacted against and used to punish the person with Lilith here. These people need to allow others their discomfort while the natives explore the world around them and ask and learn what they need to ask and learn.

Lilith in the 4th House

With Lilith in the 4th house, the family and heritage we come from centered on some or all of Lilith’s themes in one way or another. It could be that a particular family member ends up representing Lilith for the entire family, or that the family as a group experiences Lilith in a direct way. Or it could be that many members live Lilith stories from one side or the other - shunning or suppression or wildness and punishment for it. Now, this might sound like many people’s families, but there’s an edge with Lilith: the stakes of either forceful authentic self-expression in the family or at home (or leaving it behind to create a new life elsewhere to maintain wholeness), or those of suppressing the expression of self and other, are high. In other words, there is a great investment in such families either of trying to be Lilith or trying to suppress her, or both, possibly resulting in generations of what may seem on the outside of it to be a war between the sexes or other sort of power struggle between one faction and another (old and young, foreign and domestic, etc.). People with this placement need to accept these realities and learn to manage their own emotional landscapes with consciousness, compassion, and intention.

Lilith in the 5th House

Those of us with Lilith in the 5th need to create and express in authentic and unabashed ways. The connectedness that Lilith retains (or seeks, if we’re unaware of or hiding her) is in unfettered expression of her wild nature. Which she would say, of course, is simply her nature. Everything that contributes to or might result in creative expression can be avoided for fear of experiencing pain. A person with Lilith in this house might have been shamed in youth because of how he or she played. Before such a child’s behavior is edited into conformity, his or her natural expression of creativity will be colored by Lilith’s themes. The games of such children may involve one or more of Lilith’s heavy themes, any of which will be difficult for most parents to understand as natural expressions from their children, let alone accept: betrayal, abandonment, rejection, or sexual power games including rape. And they’ll play on either side of these issues – receiving or giving, as victim or persecutor.

Lilith in the 6th House

With Lilith in the 6th house, a person’s natural sense of duty and how he or she goes about getting things done is what is judged by others as potentially dangerous. People who might be in a position to mentor or train the person as an apprentice may sense something unruly and threatening about him or her and not be willing to take the person on as a student. It also indicates that this person’s natural mentors are connected with Lilith; understand and express their own version of Lilith’s energy. Finding such people will be difficult if Lilith is hiding in the person, and if she is not, finding them will involve first crossing many potential teachers off the list who reject the individual’s forthright expression of his or her reality.

Lilith in the 7th House

With Lilith in the 7th, we can look for Lilith in other people so that we don’t have to express her (the 7th holds energies we’re not necessarily sure how to relate to in ourselves and so we seek others to embody them). Whatever is in the 7th house, we need to learn to run the energy for ourselves. When we keep others around us to do it for us, we make the statement that we’re not whole. With Lilith here a person needs to take responsibility for being Lilith, and take care not to keep a door open for others’ understandings of and reactions to Lilith to come in.

Lilith in the 8th House

Lilith in the 8th house means that the instinctive, irrational, and primal side of a person is most comfortable in arenas of life where trust and intimacy are of paramount importance – this is her natural home in the person’s psyche and, therefore, outer life. This includes sexuality shared with other people, but also any relationships that require absolute honesty and have something to do with power, hence the traditional assignation to this house of “sex, death, and other people’s money.”

Lilith in the 9th House

With Lilith in the 9th house, this relationship with living a life based in having a guiding principle is what has been judged by others, and for what a person has received censure and punishment. All of the arenas of life described by the 9th house involve a sense of acting on belief and hope, understanding that such action is a risk. This risk is that the beliefs might be misguided or based in inappropriate assumptions. So, then, those with this placement may avoid risking living according to his or her beliefs to avoid negative reactions from others for bringing, or being, Lilith.

Lilith in the 10th House

With Lilith in the 10th house, a person can become a symbol of Lilith’s irrational instinct and primal wisdom to other people. His or her public self carries the energy of Lilith, and others will want to apply the prevailing labels for Lilith to this person, no matter how he or she behaves. If, after enough of this sort of treatment, Lilith in the person is hiding, developing a healthy and mature public role will be suppressed by this person. This is the house of being out in the world and of participating in the economy, leading the person with this placement to experience difficulty at work and just being out in public, for having this label applied.

Lilith in the 11th House

With Lilith in the 11th house, our pre-rational, instinctive, and wild self is most evident in the kind of future we envision, how we plan for it, and those we ally with to assist us in creating it. This can lead us to experiences of finding ourselves labeled as Lilith in every group we join, but this is an unconscious manifestation of Lilith’s placement here. We may have experienced being rejected from many groups for expressing our views, and we may have been feared as dangerous influences by organized others we attempt to befriend or with whom we attempt to become involved.

Lilith in the 12th House

With Lilith in the 12th house, a person will experience being Lilith in all contexts related to the way he or she connects with other and greater realms. To the degree that someone with this placement has internalized others’ fears about the wild as a negative statement of his or her worth and lovability, 12th house activities will be limited, avoided or denied. With Lilith here, entering into the meditative, creative or spiritual sides of this house means in some way being Lilith. Most of us choose not to experience the collective’s negativity about Lilith and will therefore avoid being her at almost all costs. Yet she is real, a part of each of us, there are times when she is activated.

Thank you for your time reading this 😊.

#Lilith#lilith in aries#lilith in taurus#lilith in gemini#Lilith in cancer#lilith in leo#lilith in virgo#lilith in libra#lilith in scorpio#Lilith in Sagittarius#Lilith in Capricorn#Lilith in Aquarius#Lilith in Pisces#Lilith in 1th#Lilith in 2th#Lilith in 3th#Lilith in 4th#Lilith in 5th#Lilith in 6th#lilith in 7th#lilith in 8th#Lilith in 9th#lilith in 10th#Lilith in 11th#Lilith in 12th#astrology#astro post#astro observations#astrology note

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright alright I just watched the entire speech and took notes 📝 here are my thoughts through my Kaylor/Gaylor colored glasses 👓

* “male model” was absolutely unnecessary but she knew she couldn’t just say model for obvious reasons but she clearly needed to say model to secret shout out Boo thang

* “writing is my compass” —so the words she writes are what guide her life. The words. Very revealing

* “we are all literary chameleons deciding who to be and when” 👀👀👀

* “years of unsolicited advice” from age 15, “constantly issued warnings” that “if I didn’t make any mistakes, all the children of America would grow up to be perfect angels” If that isn’t a full out admission to being forcefully closeted I don’t know what else it

* she got real emotional when she said “centered around the idea that mistakes equal failure and ultimately the loss of any chance at a happy or rewarding life” remember she just told us she was constantly warned about mistakes that would impact Americas children….hello anyone is this thing on? More very blatant closeting disclosure IMO

* “my mistakes (being gay) led to the best things in my life�� (another Karlie shout out)

* “protect my private life fiercely” seemed like another way to say my REAL life because we’ve all been spoonfed the very private narrative for 5 years and so it seems unnecessary to bring it up again

* “throw out the old schools of thought in the name of progress and reform 🌈” and “sit and listen to the wisdom of those who have gone before us” (all I could think of was Chely Wright)

Overall home girl did a great job. Her closing about being a doctor was chefs kiss. I do see this speech as being an undercover kind of acknowledgment to those paying attention but at the same time she always has that tinge of indignation to her words that is like fuck you I’m justified in my choices, which to me is like, whatever you need to tell yourself, Boo? We are all still waiting in the wings for the actual Letting It Go! LIFE IS TOO SHORT GIDDY UP 🌈🚪🌈

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started writing songs when I was twelve and since then, it’s been the compass guiding my life, and in turn, my life guided my writing. Everything I do is just an extension of my writing, whether it’s directing videos or a short film, creating the visuals for a tour, or standing on stage performing. Everything is connected by my love of the craft, the thrill of working through ideas and narrowing them down and polishing it all up in the end. Editing. Waking up in the middle of the night and throwing out the old idea because you just thought of a newer, better one. A plot device that ties the whole thing together. There’s a reason they call it a hook. Sometimes a string of words just ensnares me and I can’t focus on anything until it’s been recorded or written down.

As a songwriter I’ve never been able to sit still, or stay in one creative place for too long. I’ve made and released 11 albums and in the process, I’ve switched genres from country to pop to alternative to folk. This might sound like a very songwriter-centric line of discussion but in a way, I really do think we are all writers. And most of us write in a different voice for different situations. You write differently in your Instagram stories than you do your senior thesis. You send a different type of email to your boss than you do your best friend from home.

We are all literary chameleons and I think it’s fascinating. It’s just a continuation of the idea that we are so many things, all the time. And I know it can be really overwhelming figuring out who to be, and when. Who you are now and how to act in order to get where you want to go. I have some good news: it’s totally up to you. I also have some terrifying news: it’s totally up to you.

—Taylor Swift in her commencement address for NYU’s graduating Class of 2022 (May 18, 2022)

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

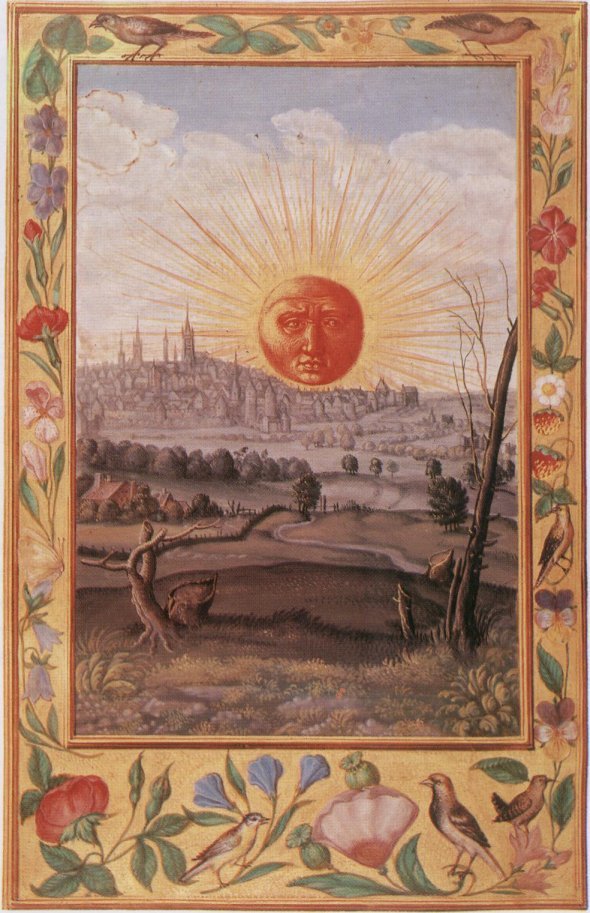

“We are all literary chameleons and I think it’s fascinating.”

Taylor receiving the Honorary Doctorate Degree at New York University (May 19, 2022)

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learn Chinese with CQL: 乃

One of the sentences in my last post on 岂 contained the following sentence:

抹额乃重要之物, 非父母妻儿 岂能触碰?

LWJ: The headband is a sacred object, no one apart from parents, spouses and children can touch it.

The particle 乃 naî was new to me, and may be new to you too, so I spent some time looking! It is a highly literary word (the earliest example I have here is from the 3rd or 4th century BC!!) and as such has had plenty of time to change. Unlike 岂, it doesn’t really seem to appear in any non-formal, non-literary contexts at all (apart from the internet slang 乃萌 = 你们).

The meanings of 乃 are very varied: according to Wiktionary, it means:

you

thus, therefore, so

‘to be’

but

才

etc…

I’ll concentrate on the first three meanings, since at least in CQL they seem to be the most common.

Short linguistics interlude:

This word is actually etymologically related to 你 and 那, as well as some Tibetan words - which is awesome, since there are fewer obvious cognates in Mandarin to the non-Sinetic side of the Sino-Tibetan family since so many sound changes have happened. The fact that it is related to both words for ‘you’ and ‘that’ explains its two widely different meanings - why it is used as a personal pronoun, but also as a copula…bear with me. There are certain patterns of change throughout language which repeat themselves across many languages, from all over the world. The change from a word meaning ‘this, that’ to a word mean ‘is, to be’ is one of these, and is hugely common in the history of Chinese as well. The copula 是 actually used to mean ‘this, that’ as well, as well as a bunch of other old copulas, so as weird as it looks it is a common enough relationship)

USAGE 1: to be

Admittedly the script of CQL isn’t the world’s most extensive corpus, but 乃 used with this meaning is by far the most common of the six.

(note: because there is a LOT of vocabulary potentially unfamiliar to many, I will give the pinyin and English translation, and leave you to pick out whatever words are new for yourself: this post is already long enough. All translations mine; take especially the literary ones with a pinch of salt)

Example 1, Lan Wangji:

抹额乃重要之物.

mó é nâi zhòngyào zhī wù

‘The headband is an important object.’

Example 2, Lan Wangji:

应该是感应到我乃蓝氏族人

yīnggāi shì gânyìng wô nâi lánshì zúrén

‘It is probably that it senses I am a member of the Lan sect.’

Example 3, Lan Qiren:

家训乃我蓝氏立身之本!“

jiāxùn nâi wô lán shì lìshēn zhī bên!

‘The family precepts are the very root of how we in the Lan sect conduct ourselves!’

Example 4, Lan Sizhui:

尔乃何人?

êr nâi hé rén?

‘Who are you?’

Here he is quoting the opening question of Inquiry 问灵, hence the unusual formality. 尔 here is a formal word for ‘you’ as well. You can sense a pattern in how Lan-ish this is…But just to reiterate hunxi’s post that lives in my brain forever about Wei Wuxian as a linguistic chameleon, here’s his compliment to Nie Huaisang on his fan:

Example 5, Wei Wuxian:

此乃当世极品啊

cî nâi dāngshì jípîn a

‘This is a superb product of the contemporary age’ = ‘This fan is extraordinary’

USAGE 2: so, therefore, thus

乃 is often used together with 是, and the meaning ranges from a simple copula, just like the above, to something more like modern 就是, 倒是. In the CQL script at least this is also fairly common.

Example 6, Lan Yi:

抱山乃是我这一生唯一的挚交

bàoshān nâi shì wô zhè yīshēng wéi yī de zhì jiāo

‘Baoshan was the only genuine friend I had in my life’ :((((

Example 7, Wei Wuxian:

晚辈乃是抱山散人之徒 藏色散人之子, 魏婴

wânbèi nâi shì bàoshān sànrén zhī tú cángsè sànrén zhī zî, wèi yīng

‘This one (lit. ’later generation’, opposite 前辈) is Baoshan Sanren’s disciple Cangse Sanren’s son, Wei Ying’

Example 8: someone naggy dunking on demonic cultivation, maybe Lan Xichen or Jin Zixuan…

身为世家弟子, 佩剑乃是殊荣!

shēn wèi shì jiā dìzî, pèi jiàn nâi shì shūróng

‘As the disciple of one of the world’s foremost clans, carrying your sword is (=should be) an honour!’

In the examples 6 and 8, 乃 could be substitued for 就是 or 倒是 in more modern language.

USAGE THREE: you

This usage in particular appears to be very, very old: there are no examples of it in CQL as far as I have found. There are a lot of identity-adjacent personal pronouns used, humbling or honorific, but no uses of 乃 as just a regular second-person pronoun (though we do get 尔). I’ve pulled one final example from Wiki instead - only one, I’m afraid, because all the others were horrifically complicated to translate.

Example 9, 3rd/4th century BC, 书经 ‘The Book of Documents’:

朕心朕德, 惟乃知。

zhèn xīn zhèn dé, wéi nâi zhī

‘My heart and my morals (= ‘my innermost feelings), only you know.’

Two points here: 朕 is a first person pronoun, and 惟 is an alternative to 唯 as in ‘唯一’ ‘the only’.

There we go, that’s it!! I hope you found that interesting. If anybody decides to film a prank video where they start a Chinese class introducing themselves by saying ‘在下乃…’, do tag me.

加油!

- 梅晨曦

#two! posts! in! one! day! it's all fun and games with melissa#learn chinese with cql#learn chinese with lwj#learn chinese with wwx#chinese#langblr#classical chinese#chinese grammar#grammar#learn chinese#literary chinese#honestly this series = I like#very fun#also the 3rd century BC??????#do you ever speak and just...feel the weight of history in your mouth#in the 3rd century BC English was busy just...being proto-germanic#the oldest really English old English (as opposed to being dubiously 'germanic') is from about 450 CE#to put that in perspective#from 4th century bc that is EIGHT CENTURIES LATER#and now it's being used on the internet as slang#these things...I don't enjoy going to museums much#too adhd etc#but when we speak isn't it incredible that we preserve without knowing it#vestiges of hundreds of generations of lovers and children and classmates#in our verb systems and irregularities - I'm looking at you Verner's law#it's just....it is astounding#whenever anything else lets you down words will always be there#there's always something to learn and always something to wonder at#and you can feel the weight of all those people that have gone before us#they are some of the oldest objects we have words

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

"we are all literary chameleons" 🧠🦎

- Dr. Taylor Swift (@taylorswift )

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ML Analysis: Alya Cesaire: Best friend or Plot Puppet?

Thank you to @cakercanart for commissioning this analysis.

For this we will be discussing Alya Cesaire

This is a LONG POST, so I am posting a read more. I would love to hear your thoughts on this analysis. Do you agree? Do you disagree? Did you want to include something? Let me know.

I think in order to organize this post I will be splitting it up as follows.

How to write a best friend.

Alya Cesaire the Best Friend

Alya Cesaire the Plot device

Canon vs Salt

Final thoughts

So lets get to it