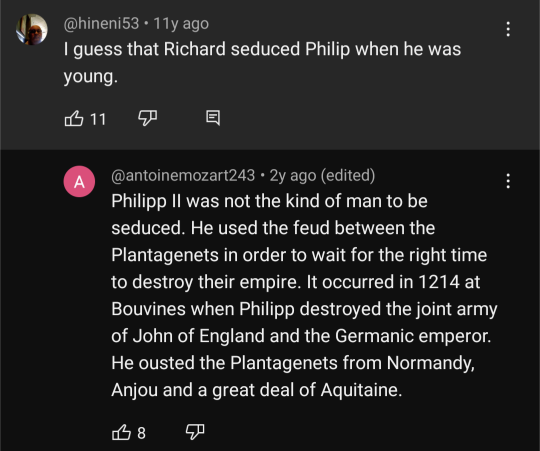

#what does Bouvines have to do with any of this!!!

Text

This is one of my favorite Bad TLIW takes of all time just the sheer irrelevancy of it XD

#TLIW#the lion in winter#Newsflash if ur a successful and crafty adult politician it's impossible to get molested as a teen A+ logic#what does Bouvines have to do with any of this!!!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hugo: Beginning with 1818, doctrinarians began to spring up in them, a disturbing shade. Their way was to be Royalists and to excuse themselves for being so. Where the ultras were very proud, the doctrinarians were rather ashamed. They had wit; they had silence; their political dogma was suitably impregnated with arrogance; they should have succeeded. They indulged, and usefully too, in excesses in the matter of white neckties and tightly buttoned coats. The mistake or the misfortune of the doctrinarian party was to create aged youth. They assumed the poses of wise men. They dreamed of engrafting a temperate power on the absolute and excessive principle. They opposed, and sometimes with rare intelligence, conservative liberalism to the liberalism which demolishes. They were heard to say: “Thanks for Royalism! It has rendered more than one service. It has brought back tradition, worship, religion, respect. It is faithful, brave, chivalric, loving, devoted. It has mingled, though with regret, the secular grandeurs of the monarchy with the new grandeurs of the nation. Its mistake is not to understand the Revolution, the Empire, glory, liberty, young ideas, young generations, the age. But this mistake which it makes with regard to us,—have we not sometimes been guilty of it towards them? The Revolution, whose heirs we are, ought to be intelligent on all points. To attack Royalism is a misconstruction of liberalism. What an error! And what blindness! Revolutionary France is wanting in respect towards historic France, that is to say, towards its mother, that is to say, towards itself. After the 5th of September, the nobility of the monarchy is treated as the nobility of the Empire was treated after the 5th of July. They were unjust to the eagle, we are unjust to the fleur-de-lys. It seems that we must always have something to proscribe! Does it serve any purpose to ungild the crown of Louis XIV., to scrape the coat of arms of Henry IV.? We scoff at M. de Vaublanc for erasing the N’s from the bridge of Jena! What was it that he did? What are we doing? Bouvines belongs to us as well as Marengo. The fleurs-de-lys are ours as well as the N’s. That is our patrimony. To what purpose shall we diminish it? We must not deny our country in the past any more than in the present. Why not accept the whole of history? Why not love the whole of France?”

Hugo, clearing his throat: Anyway, that's what the doctrinarians were saying. I wouldn't know anything about that, though.

#Vicky as a narrator is funnier than any character he could intentionally write#and this makes sense to be careful about saying what with NIII and everything#but it's still really funny how thinly-veiled this is#shitposting through les mis#still 3.3.3#this café keeps playing bangers and I can't focus#shitposting @ me#thicctor hugo#vicky huge-hoe#les mis#thicc vicc

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

i know how much you've richard the lionheart, so do have any thoughts about king john, particularly how he has been largely villainised in pop culture?

Ahaha. Poor John.

In one sense, I think it’s obviously been very easy to cast him as the villain: he was heartily disliked in his own time, was not much mourned when he died, and had the following centuries of the Magna Carta being held up as the forerunner of representative democracy, and him as the evil greedy king. Then of course the rediscovered popularity of the Robin Hood legends made him the villain again, and yeah. History, to say the least, has not been kind to John, and while other kings occasonally get “rehabilitated” or reworked or otherwise get a critical examination of the mass of popular perceptions surrounding them, I’m not sure that anyone has tried that extensively with him. You can’t ignore the fact that his contemporaries pretty much hated the guy, and the major political legacy of his reign (the Magna Carta) is one that does not lend itself, from the modern angle, to a ton of sympathy for him.

In my view, as ever, I say that John was fairly complicated. He certainly did not start off in the best position when he came to the throne. Richard left him no money and an ongoing territorial war with Philip II of France, and since Richard had been absent from England so often, the barons had built a fairly reliable system of government in which the king did not necessarily need to be around for the country to run. In one sense, John’s misfortune was to be born on the wrong side of the Anarchy; William I, William II, and Henry I were all strong personal rulers with an iron grip on their barons, and part of the causes for the Anarchy were because Stephen could not control his rapacious and misbehaving vassals. If John had lived in that era, he would have followed in that model, and it probably wouldn’t have been terribly different from the others.

But England’s political structures had changed enough with the rules of his father (Henry II) and brother (Richard I), that when John came to the throne and wanted to run everything himself again, stepping on the barons’ toes as a result, trouble was almost a foregone conclusion. He was probably the member of his immediate family who was most interested in being the actual king of England and having a day-to-day hand in the operation of its government, especially after 1204, when the loss of most of the crown’s French territories meant that he had to actually be in the kingdom. (As well, the loss of Normandy was a huge symbolic blow, as it was obviously William the Conqueror’s own possession and the other half of the Anglo-Norman kingdom; the nobility all had estates in both England and Normandy, and now had to divide them between sons, further weakening families. John tried for ten years to get it back, but Philip solidified his victory in 1214 at the battle of Bouvines.)

As well, John’s situation with his nephew Arthur also left him between a rock and a hard place. Arthur was the son of his late elder brother Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany, which meant that technically by law, Arthur had a better claim to the throne than John did. Richard had named John his heir before his death, and they had worked together somewhat more after Richard’s return from German captivity in 1194 (John and Philip had been up to all sorts of mischief while he was gone on crusade, but Richard ended up reconciling with him.) John was also an adult, while Arthur was a teenager, and Philip would always have maintained Arthur as a rival claimant to the throne. So, by political necessity, it was easier for Arthur to disappear… as indeed he did, but killing your own nephew in cold blood was pretty bad, even for the thirteenth century, and John was obviously, immediately blamed for it.

This continues a larger pattern of John’s, which fatally weakened his reign: he was vindictive. No, he didn’t come to the throne in the best circumstances, and he was on the back foot since he was not nearly the warrior and military strategian that Richard was, so he was going to end up at a disadvantage in any longer conflict. However, it was certainly nothing out of the ordinary, and plenty of kings made a success of their reigns even in less-than-ideal circumstances to start off. John, however, was too interested in personally punishing people who had wronged him; he dealt harshly with the de Braose family, with William Marshal (who was the backbone of the early Plantagenet dynasty and would serve as regent for John’s son, the young Henry III), with the lords captured after the 1202 siege of Mirabeau (including some of Richard’s most loyal barons, who had turned against John, and could have been turned back to friends), with the Welsh, with the French, with the church – the list goes on and on.

It’s hard to maintain a functional rule if you’re most concerned with punishing people, and John got all of England excommunicated in 1209, which, believe me, did no favors for his popularity. By the time his barons forced him to accept Magna Carta in 1215, the situation had deteriorated to pretty much the point of no return (John accepted it and then immediately appealed to Pope Innocent III to annul it, so… also not helping.) You know it’s bad when English barons are actively asking for another Frenchman (the future Louis VIII, eldest son of Philip II) to invade the country and become king. John also lost the Crown Jewels, soon before his death, so yeah. Didn’t exactly go out on a high note.

Basically, I think John was a complicated and certainly considerably intelligent man (not at all the drooling idiot portrayed in The Lion in Winter, much as I otherwise love that movie), and he had some successes (especially while Eleanor was still around to help, but she died in 1204, weeks before the loss of Normandy). But he took care of pretty much permanently trashing his own reputation before his death, and he seems to have been one of the men who could have been great if they could have gotten out of their own way, which he couldn’t. He also had the unfortunate luck of being associated with both the Magna Carta and Robin Hood, as those are two traditions that a) had historical sticking power, and b) easily cast him as the bad guy. Like all the Plantagenets, he was talented, intelligent, interesting, and ambitious, but fatally flawed, and that’s what has stuck, probably the most of his family, for him.

30 notes

·

View notes