#when the santa fe motif comes in ????

Text

rooftop instrumentals from newsies are so good listening to it is not enough i need to be in the scene.

#when the santa fe motif comes in ????#fuuuckkkkk#i am a puddle of tears#this happens every time the santa fe theme is added to the background instrumentals in the movie#92sies

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Pick one of the figures in this sculpture and do your best to take on their position. How does it feel to be in this position? When have you been in a similar position?

This sculpture incorporates many figures, each with their own distinct expression and position. The largest figure, a woman wearing a Pueblo dress, sits with her legs straight out, her hands resting on her knees, and her shoulders rolled forward a little. Her head is level, but she raises her eyes upwards, towards the vessel balanced on her head. This vessel is a traditional ceramic of the Kah’p’oo Owinge (Santa Clara Pueblo), the Tewa pueblo to which the artist Roxanne Swentzell belongs. Climbing out of this black pot are two much smaller figures. One leans on the rim, looking off in one direction, while the other figure’s head just barely begins to emerge from within the vessel. Below, standing on the shoulder of the woman with a hand resting on her forehead for support, is a standing figure, reaching up towards the two emerging from the vessel. Resting in the crook of the woman’s right arm, is the final figure: while all the other tiny figures are wide-eyed and engaged in their various activities, this figure on the woman’s lap is lounging, turning a contented face upwards as though basking in the sun.

How would you describe the expression of the woman? Is she tired, fatigued by the energy of these small figures? Is she amused and content? Is it something else? Whenever I return to her face, I find a new shade of emotion as she experiences the commotion of the many figures crawling over her. I imagine her holding her breath and watching the vessel wobble as the figures crawl out of it.

The iconography—that of a larger figure with many smaller figures crawling all over—has become a common motif in Pueblo ceramics; it is known as a storyteller figure. The first was created by Ko-Tyit (Chochiti) Pueblo artist Helen Cordero, who made it in the 1960s to honor her grandfather, a renowned storyteller. Swentzell, too, thinks about communication between generations. She has said, “We are the mothers of the next generation and the daughters of the last. Male or female...in the Pueblo world, we are 'Mothers' (nurturers) of the generations to come in a world that supports life. It is always good to remember…to nurture life, for it is our work now as it was for our parents and ancestors that came before us and it will become the work of our children.” The very clay the Swentzell uses is a reminder of this as well; she uses locally sourced clay, thus tying it to the land of New Mexico itself. She says, “To have human figures made of clay is in itself part of the theme. We are all from this Mother, all from this Earth: made of her and will return to her... I love the perspective of understanding that we all come from the Earth.” What might it mean to work for life for future generations? How does art become part of that work?

Swentzell also plays with this storyteller imagery in this sculpture, linking the idea of communication from one generation to the next with the act of creating artwork for sale. Swentzell is a renowned sculptor, and her work has been honored at the prestigious Santa Fe Indian Market. Initially, she never considered selling her work. Instead she sees sculptures as an extension of her ability to communicate, like pages in a diary. Now that she does sell her work, she often explores the relationship between Indigenous identity, Indigenous art, and commodification. This particular work is known as Making Babies for Indian Market, a reference to the annual Santa Fe Indian Market. How does the title relate to what we see in the sculpture? What might Swentzell be suggesting about the relationship between creating art and selling it?

How do art, identity, and commodification intersect? What do the implications of these intersections and relationships have for future generations? In what ways are future generations a consideration in your own life or work?

Posted by Christina Marinelli

Roxanne Swentzell (Kah'p'oo Owinge (Santa Clara Pueblo), born 1962). Making Babies for Indian Market, 2004. Clay, pigment. Brooklyn Museum, Gift in memory of Helen Thomas Kennedy, 2004.80. © artist or artist's estate

#howtolook#roxanne swentzell#Kah'p'oo Owinge#Santa Clara Pueblo#sculpture#art#artist#native american#Pueblo#storytelling#mother#children#nurturers#new mexico#generations#Sante Fe Indian Market#Indigenous art#Kah’p’oo Owinge#Ko-Tyit#Helen Cordero

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

A couple hours late but I just saw you saying how Jesse and Fareeha are more inverses of each other and I completely agree! I personally see Sombra and Jesse as more paralleled, and would be interested in hearing your thoughts on that idea? You tend to be very well-spoken and are good at analyzing concepts, I've come to notice.

EDIT - NOVEMBER 3, 2018: With the release of “Reunion” and Ashe’s hero reveal, the majority of what I wrote about Deadlock in the first three sections—Sign of the Skull, Those Left Behind, Revolutionaries and Rebels—is incorrect. Despite this, I maintain that the socioeconomic context outlines in Those Left Behind remains relevant to the American Southwest in-universe and maintain my belief that it is applicable to McCree specifically, even if it does not apply to Deadlock. I will be writing a new post on Sombra and McCree soon. Stay tuned.

in reference to this post… from months ago

Lucky for you, I was thinking about Jesse and Sombra the night before you sent this! Deadlock and Los Muertos, actually, but I’ll get to that. I absolutely agree that the two of them make much more direct parallels than Jesse and Fareeha, who are interesting as a pair in their own right but they aren’t direct parallels.

I often joke that Gabe adopted the same child twice: smart-talking, hyper-competent Latine who tote around skull logos and are from gangs with the word “dead” in their names. It’s a joke—I don’t consider Gabe’s relationship with Sombra to be that of a parent-child, for one thing—but I believe that Jesse and Sombra are very similar regardless.

They both have similar backgrounds: joined local gangs at a very young age and earned later membership into a high-level covert organization through resourcefulness and an admirable natural aptitude in a specific desired skillset. Although both at first look to be unserious and overly laid-back, they prove themselves to be precision operators who indeed execute plans and achieve goals with immense gravity. They’re both supremely confident in their abilities, to the point that one can accuse them of having too high an opinion of themselves and being overconfident.

They come from similar backgrounds, having been orphaned during the Crisis and suffered under economic disparity driven by infrastructure changes in the rebuilding period. They both similarly drop off the map and resurface under new identities. They both have a deep concern in seeing done a justice that is beyond the reach of the law—or when the law refuses to deliver it.

All this, and more, under the cut. The post is very long.

I would also like to thank @segadores-y-soldados for all he’s written, especially on Sombra and especially recently. I make heavy reference to his writing on Sombra in certain portions of this post. I also must admit that reading his posts on Arturito has motivated me to finish this after three months of slow progress, though I still have a nagging feeling I’m forgetting a point.

Sign of the Skull

To make a quick run-through on Los Muertos and Deadlock Gang themselves before moving onto how these organizations inform Sombra and Jesse specifically. Sort of a section to outline basic things about the gangs that doesn’t neatly fit into other points. It’s mostly to establish their context, and some similarities between their structures and presentation.

Screenshot from the Sombra Origin showing members of Los Muertos. Each member has painted skeletons onto themselves with phosphorescent paint in varying colors.

Los Muertos is a Mexican gang with apparent regional influence with members in both Dorado and the nearby Castillo, and it even has some international reach judging from the Los Muertos graffiti on the Hollywood map. Little is known to us about their structure besides this, and even in-universe they are noted to be mysterious with little information publicly available about them.

However, Los Muertos openly broadcasts their intentions: to right the wrongs committed by the wealthy and powerful against the disadvantaged of Mexico. They position themselves as transgressors of the law specifically to disrupt the lives of the “vipers” in power. More on that later.

The name translates to “The Dead”, and they are identified by skull motifs, specifically the calaveras associated with the Mexican holiday Day of the Dead. Individual members openly identify themselves and indicate their membership by painting skulls and bones on their bodies with phosphorescent paint.

Screenshot from the Route 66 map of five motorcycles parked in front of The High Side bar. The Deadlock emblem is spray-painted by the entrance.

Deadlock Gang is an American motorcycle club and organized crime ring occupying a Southwestern town on an abandoned stretch of Route 66 running across Deadlock Gorge. It’s unclear where exactly the Gorge is, and the Visual Source Book’s pin for the map is highly unspecific, but I tend to believe it’s in somewhere in northern New Mexico because Jesse’s base of operations is listed as Santa Fe, NM.

In one lore piece, Deadlock is holding a national rally, suggesting they’ve got chapters nationwide and the founding chapter is in Deadlock Gorge. While it’s unclear what their reach is, there is a possibility of international chapters. (Torbjorn’s motorcycle-themed Deadlock skin may suggest this, but it does not have any Deadlock iconography, notably showing a bear where one expects the Deadlock emblem.)

This does not necessarily mean all of the Deadlock Rebels Motorcycle Club is a criminal organization, nor every single member a criminal, but… y’know, the founding chapter is a weapons trafficking racket. They’re a one-percenter outlaw motorcycle club, and there’s a quick and easy comparison in the real-life Hells Angels, whom the show Sons of Anarchy models itself after.

Deadlock, besides naming itself after the concept of death like Los Muertos does, also uses a skull in its emblem. We haven’t seen any member of Deadlock pictured, but extrapolating from the typical behavior of motorcycle clubs, they likely openly identify themselves and indicate their membership by wearing standardized jackets or most likely vests. Members likely have tattoos indicating membership as well, seeing as Jesse has a tattoo of the Deadlock emblem on his inner arm in his Blackwatch skin.

Those Left Behind

Sombra, orphaned during the Omnic Crisis, was taken in by Los Muertos, a gang that positioned themselves as champions of the underclass ignored during the post-Crisis rebuilding process. They’ve done this most notably by opposing the CEO of LumériCo Guillermo Portero, who they’ve described as having exercised his social influence to have many wrongfully imprisoned and who we know is working with the not-as-noble-as-they-put-forward Vishkar.

The social context of Los Muertos and Sombra is very directly told to us. From Sombra’s official bio:

After ░░░░░░ was taken in by Mexico’s Los Muertos gang, she aided it in its self-styled revolution against the government. Los Muertos believed that the rebuilding of Mexico had primarily benefited the rich and the influential, leaving behind those who were most in need of assistance.

From a lore post published to the website:

…its members style themselves as revolutionaries who represent those left behind by the government after the widespread devastation of the Omnic Crisis.

And Michael Chu on Los Muertos at Blizzcon 2016 (transcript):

Mexico really suffered a lot at the hands of the Omnic Crisis. The war destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure. […] They claim to be kind of revolutionaries fighting for people who were left behind during the rebuilding of Mexico after the war.

Despite their noble stated goal, they seemingly also cross a line in their illicit activity enough to earn the ire of Jack, who isn’t exactly on the straight and narrow himself but still seeks the right side of things. As Chu added:

Whether or not that’s really what they are up to, because they’re also engaged in a lot of other shady activities. It is up to you decide.

Given a lot of other suspect activity they engage in, that noble work might not be the only story to be had on them—especially depending on where you’re standing. Saviors with their thumbs in certain pies not meant for them, possibly.

The social context that Sombra rises out of is made very plain for us. But what does it have to do with Jesse?

While we know few specifics about his circumstances growing up, other than he also lived through the Crisis and was likely similarly orphaned during it, the description and in-game environment of the Route 66 map suggest the area is one of difficult social and economic circumstances, emphasis mine:

Though the travelers and road trippers who used to cross the US on historic Route 66 are gone, the Main Street of America still stands, a testament to a simpler time. The gas stations, roadside shops, and cafes have gone into disuse, and the fabled Deadlock Gorge is mostly seen from the comfort of transcontinental train cars. But amid the fading monuments of that earlier era, the outlaws of the Deadlock Gang are planning their biggest heist yet.

Concept art of The High Side, showing the abandoned bar in disrepair with boarded windows and faded paint.

At least one building, the Cave Inn (ba dum tsh) in the streets portion of the map, is visibly abandoned, and the theme of disrepair and long-gone halcyon days is especially prevalent in the concept art for the map. This all paints a portrait of a Deadlock Gang that operates out of an area that suffered immense economic hardship in recent years, likely particularly after the introduction of the transcontinental train cars, one of which is featured in “Train Hopper”, a comic which takes the time to emphasize the wealth of the passengers traveling on them. So, the Deadlock chapter is localized within a region that suffered economically under infrastructure changes that largely benefit the wealthy and powerful. It’s possible that these infrastructure changes were made possible because of efforts to rebuild after the physical devastation of the Crisis.

Without going off on a tangent about it, there’s a bit of a difference between “Deadlock comes out of the lower class in a geographic region beset by poverty” and “Deadlock gang itself currently has no money”. Apparently, well after the effects of financial misfortune set in, Deadlock was and is making enough money to maintain long-distance shipping, as suggested by their semi-trailer truck, and keep an entire town functioning well enough as a cover for their criminal enterprise. Also, missiles don’t sell for cheap. Deadlock might be financially comfortable now, but their context still involves deep socioeconomic disparity.

This is especially poignant against the Route’s invoked nickname, Main Street of America, which conjures images of the average American person. Those average people who owned gas stations, cafes, diners, roadside trinket shops, dive bars are the ones who are forgotten while the more affluent folks pass them over, traveling in style. There’s also a historical precedent in poverty and social disparity as driven by infrastructure changes specifically affecting the way people travel across regions and the country, specifically in the history of the freeway.

To sort of make the clarification, Jesse’s tattoo states that Deadlock was established in 1976—happy centennial, Deadlock—so they’ve certainly changed a lot as their social context and membership make-up changed. There’s much to be said about social non-conformity, outlaw motorcycle gangs, one-percenters, community integration, and how these intersect with both the politics and economics of the local communities along Route 66, especially given how the Route was recently listed as one of the country’s most endangered historic places, even in Deadlock’s apparent founding in a period of American social unease after the Vietnam War and during the late Cold War, and extrapolate a lot about Deadlock from all that, and even about Jesse himself from some of it, but that’s for a different post.

Revolutionaries and Rebels

In that context, it’s worthwhile to note that in their insignia, seen in the graffiti all over the Route 66 map and in Jesse’s tattoo in his Blackwatch skin, they calls themselves the Deadlock Rebels. Generally, outlaw motorcycle clubs are also known for their contempt for social convention and disdain for status quo.

Screenshot of the Deadlock Gang hideout with their insignia, which includes the words Deadlock Rebels, spray-painted onto a wall.

Deadlock is quite the opposite of Los Muertos, though. Deadlock maintains a law-abiding public face—holding innocuous and even advertised national rallies and hiding their illicit activity under numerous cover businesses—and are more discreet in their disrespect of law. One can double down on this by looking to how successfully real-life one-percenter clubs maintain their public image: openly contemptuous of social norms but keeping public knowledge of any legal transgressions to only the small indiscretions while hiding the major ones.

Taking a look at Deadlock’s primary targets, military installations: the train cars on the map are military-related, the gang traffics military hardware and weapons including missiles. Although Deadlock comes from a similar social context as Los Muertos, these aren’t targets seeking to effect a change in society like how Los Muertos seeks to. Deadlock appears largely self-interested, with little interest in changing the fortunes of anyone else in the American lower class. Los Muertos bills itself as other-interested, seeking to change the fortunes of the Mexican underclass as a whole.

Archetypically, Los Muertos are revolutionaries, Deadlock are rebels. While they both groups reject the status quo, the revolutionary seeks sweeping social change but the rebel rejects the status quo on a personal level. The revolutionary wants society to change to suit their vision of what it ought to be while the rebel positions themselves outside of society and will redefine themselves as society changes.

The difference is apparent in their choice of targets. Los Muertos targets institutions and people who directly have a hand in the building of their social context, and attacking those targets will potentially affect a social change. Deadlock targets institutions and people who may have a hand in their social context, but such targets are chosen primarily for the gang’s financial gain.

Los Muertos is politically motivated. Deadlock is financially motivated.

Admirers in the Shadows

Sombra and Jesse don’t remain in their gangs. They both end up joining shadow organizations with global reach, the terrorist organization Talon and the covert ops organization Blackwatch, respectively. Both organizations were wooed by their specific skillsets.

Sombra launched an even more audacious string of hacks, and her exploits earned her no shortage of admirers, including Talon. She joined the organization’s ranks…

With his expert marksmanship and resourcefulness, he was given the choice between rotting in a maximum-security lockup and joining Blackwatch, Overwatch’s covert ops division. He chose the latter.

A young Jesse McCree was recruited into Blackwatch after Gabriel Reyes saw his potential and gave him a choice: join Blackwatch, or rot in prison.

The difference here is that Sombra was offered a place, but she did not necessarily need that offer to continue on with her life. She takes it because Talon resources allow her to more effectively pursue her goals. If McCree did not take the offer to join Blackwatch, his life effectively ended. (There’s a whole thing to be said about this offer, why it was the best offer that could have been made to him at the same, and criminal rehabilitation—but that’s another post.) McCree’s decision to join Blackwatch isn’t motivated by pursuit of a specific goal. He just didn’t want his life to be over before it started. In that regard, his entire life is shaped very directly by his relationship to Overwatch as an individual and Blackwatch, even more than simply its role in ending the Crisis and overseeing the rebuilding efforts.

Sombra, as someone who survived the Crisis, similarly has that more distanced influence of Overwatch in her life, but there’s the possibility she may have a more direct one.

With the recent spawn interaction between Sombra and Hammond showing a sentimentality for her stuffed Overwatch bear, seen in her den in Castillo, there is a possible picture to paint of a Sombra who may have some sentimentality toward Overwatch and might be aiding individual members on the sly not only because she wants to uncover the Grand Conspiracy they’re caught up in but also because she has a personal motivation.

segadores-y-soldados has a lot of good and very recent speculation on what this could mean for Sombra, either working with the room in her background for her to have worked with Blackwatch or having her as never having worked with Overwatch. If she worked with Blackwatch, which is admittedly a shakier theory, it creates a direct and clear mirror with Jesse: given a second chance at life through working with Overwatch and Blackwatch. If she did not and the influence is only the distant one, and she simply remained on the edges of society and making use of the space available, it is an inverse of Jesse. I recommend reading these two posts on the idea: one, two, three.

Name: REDACTED

One could compare Sombra attempting to eradicate her identity as Olivia Colomar and later returning as Sombra to Jesse going underground after leaving Blackwatch and later resurfacing to work as a bounty hunter. Their decisions to drop off the map have different motivations and different degrees of extreme, and there is a different tenor in how one disappears as Olivia and returns as Sombra and the other disappears as McCree and makes a resurfaces in a return to that identity.

Sombra accidentally stumbled onto a massive conspiracy that controlled the world and drew their attention, compromising her security and forcing her to destroy all trace of Olivia Colomar to go into hiding. She came back as a completely new person with no trails to her old identity, a transformation so complete that it took years to connect the two.

It is possible to draw a stronger parallel between them here. Jesse similarly has parts of his identity that he’s hiding (but which Sombra knows about):

Sombra: Pleasure working with you, McCree… if that is your real name.McCree: Don’t know what you heard, but my name’s not Joel. Best remember that.

There’s a strong case for the Jesse is the journalist Joel Morricone theory: at some point in his life, he created a second identity for himself and is working to keep the two separate. It’s currently unclear exactly what the details of the arrangement is or why he goes to these lengths. Given that he disappeared for “several years” after quitting and before reappearing again as Jesse McCree, gunslinger for hire, it stands to reason he spent the intervening years living quietly under the Morricone identity.

We don’t really know much about the specifics of what motivated Jesse to go to ground, but based on his official bio, it seems related to the infighting following the Talon infiltration at Overwatch and Blackwatch that also drove him to quit. It could likely be motivated by security reasons—in a similar but less drastic way that Sombra burned her old identity to protect herself.

Justice Against Law

One of the building blocks of McCree’s character is his stance on justice. He makes it very clear: he is concerned primarily in dispensing justice to the point that he only accepts jobs as a bounty hunter if he believes the cause just and constantly gets involved in vigilantism, putting a stop to crimes both petty and serious.

Through this dogged pursuit of seeing justice done, he seeks a self-redemption for the wrongs he committed early in his life: “he came to believe that he could make amends for his past sins by righting the injustices of the world”. At the same time, he makes it clear that he believes justice and law run on different wavelengths. He appreciates Blackwatch for its “flexibility” to move “unhindered by bureaucracy and red tape”. The Morricone article seems to suggest a belief that justice can be defended by law, but everything else about him strongly states that he does not believe justice is exclusively defended by law.

The short version: McCree has a rigid sense of justice and dedicates his life to seeing it carried out, but he does not equate it with the law. Both of those points are amply evidenced and are at the forefront of McCree’s character.

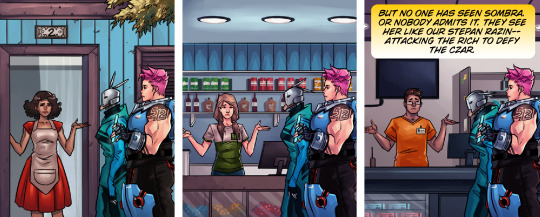

Edited sequence from the “Searching” comic where Zarya and Lynx-17 go door-to-door, showing everyone a photo of Sombra. Zarya’s internal dialogue in the last panel: “But no one has seen Sombra. Or nobody admits it. They see her like our Stepan Razin—attacking the rich to defy the czar.”

Sombra is (perhaps surprisingly) similar. As stated previously, she was brought in by a gang who billed themselves as seeking a justice for the Mexican underclass that they believed could not be achieved through legal means.

On her own? She holds to those ideals and that goal. She attacks and exposes the CEO of LumériCo, creating an opening to see some justice done for the Mexican people. (The attempt failed, and Portero is reinstated, but that’s besides the point.) Her continuing interest in seeing the Viper Portero removed only makes sense if she continues to have a personal investment in seeing justice for the underclass of her country.

This leads to Sombra being seen as an extrajudicial force of change and good by the Mexican people, particularly those in the Castillo and Dorado region. Zarya compares her to Stepan Razin (Wikipedia), who as I understand it led force composed in part of peasants in uprising and, though he failed, was immortalized as a folklore hero.

Though her methods are different and her goals much more specific, her actions, at least in Mexico, are similarly driven by a search for justice that cannot be delivered by the law.

The Enemies of Talon

I don’t have a lot to say about this, and segadores-y-soldados has summarized it quite better than I have, but it’s important enough to get it’s own section. But, Sombra working against Talon actually puts her technically on the same side as Jesse is—even though Jesse as of “Train Hopper” doesn’t seem that interested in actually ending Talon’s activities or denying them what resources they want, only in preventing them from hurting and killing innocents. (Though, I doubt Jesse is going to remain in that mode for long.)

It is entirely possibly, maybe even likely, that Sombra is aiding Jesse somehow as well as aiding Jack and Ana. I linked a couple of segadores-y-soldados’ relevant posts earlier, but I’ll link them again: linked before, new link.

Miscellanea, Smaller Comparisons

Sombra is embraced by her old gang Los Muertos, even though she has broken ties with them for her safety, as evidenced by the gang’s enthusiastic and open support of her attacks on LumériCo. Deadlock openly rejects Jesse and is suggested to have a “shoot on sight” policy for him, as evidenced by the numerous photos of him accompanying rifles and his photo pinned to a dartboard; it’s possible that they resent him for having avoided prison and taking the presented opportunity to turn over a new leaf.

Even after leaving their respective gangs, both Jesse and Sombra still make use of variations on the gangs’ symbols in their personal iconographies. Sombra identifies herself through a simplified graphic calaveras. While in Blackwatch, Jesse openly displays his tattoo and wears a buckle of the Deadlock winged skull; after leaving Blackwatch, his prosthetic arm features plating shaped like a skull. (The iconography extends to the game’s UI also, with EMP represented by a calaveras and Deadeye with a skull.)

Both take somewhat similar relationships to Gabriel: Jesse is framed as a surrogate son and a right-hand, Sombra is framed as a young accomplice who takes a more familiar tack and a frequent trusted partner. They’re opinionated and vocal about it, unafraid to talk back to Gabriel and criticize his planning.

Further in the personality vein of things, they’re characterized as deeply confident in their abilities to the point of cockiness and overconfidence, and they can be accused (and have been, by Gabriel, though with dubious sincerity) of having too high an opinion of themselves. But despite the breeziness, they are highly competent, thorough, and conscientious, and although they may appear to have a lot of things to say about other people’s plans, they execute their own plans with precision and utmost gravity. Arguably, both are playing a bit of the fool to mask how sharp, observant, and cunning they really are.

#Jesse McCree#Sombra#Sombra Overwatch#Olivia Colomar#Overwatch#Anonymous#Gena plays Overwatch#I FINALLY FINISHED IT.#I apologize to you anon for taking three months but it's nearly 4k words and I was in a slump.#But I am always very happy to talk about things—especially if it's McCree related.#But Sombra and McCree are very interesting as paired characters.#I fear I've spent more time talking about Los Muertos and Deadlock than I have Sombra and McCree though.#But I am deeply interested in the social dynamics and context of Deadlock specifically and all that can be drawn out of the little we know#so I tend to let it get away from me when talking Deadlock.

159 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://toldnews.com/technology/entertainment/the-handmaids-tale-comes-home-to-boston-as-an-opera/

‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Comes Home to Boston. As an Opera.

BOSTON — When Margaret Atwood began her novel “The Handmaid’s Tale” with the line “We slept in what once been the gymnasium,” she may well have been referring to the Lavietes Pavilion here.

After all, the dystopian story abounds with references to Boston and neighboring Cambridge, and suggests a Harvard University — Lavietes, its basketball arena, included — repurposed for the militaristic theocracy of Gilead.

Boston Lyric Opera is running with that possibility. For its new production of the Danish composer Poul Ruders’s unsettling and complex 2000 adaptation of the novel, the company opted for something site-specific. The gym was available, and for the first time the opera will be staged in the city where it takes place.

This is a happy coincidence for Boston Lyric Opera, which has been nomadic while it searches for a permanent home. (The company ended its relationship with its longtime space, the Citi Performing Arts Center Shubert Theater, in 2015.) But that doesn’t mean staging an opera in a basketball arena is without its challenges.

The acoustics, to start, can be a nightmare. And converting the basketball court involves effectively building a theater from the ground up. Then there’s the Ruders opera itself: a dense and difficult score with one of the most taxing mezzo-soprano roles in the repertory. (She spends nearly all of the work’s two-and-a-half-hour running time onstage.)

“There’s no comparison,” Jennifer Johnson Cano, the mezzo singing the title role of Offred, said after a recent rehearsal. “This is more challenging than Verdi and Wagner. I’ve done Elvira and Carmen. This beats all of them.”

But despite the opera’s demands — in addition to its leading role’s endurance test, the work also calls for a large orchestra and cast — it is having a resurgence, thanks in large part to the popularity of Hulu’s television adaptation of the novel, the #MeToo movement and the ever more urgent conversation around climate change.

“Any producer wants to have a thermometer on the zeitgeist,” said Esther Nelson, Boston Lyric Opera’s artistic director, who, as it happens, made a small appearance in the 1990 film adaptation. “This is the time to do ‘The Handmaid’s Tale.’”

Ms. Nelson and the company are ahead of the curve but will soon be joined by others. Mr. Ruders — whose new opera, “The Thirteenth Child,” will be given its premiere at Santa Fe Opera this summer — said that productions were in development in Copenhagen and San Francisco.

“This is certainly a happy thing for a composer,” he added, acknowledging that “The Handmaid’s Tale” has received an unusual number of productions for a contemporary opera, including an acclaimed American premiere in Minneapolis 15 years ago.

He began work on it in the mid-1990s with the blessing of Ms. Atwood, who, he recalled, agreed to the adaptation as long as she didn’t have to be involved with it. (She will be in Boston on Saturday to talk about the opera with Mr. Ruders at WBUR CitySpace.) His librettist was the British actor and writer Paul Bentley, later known for playing the High Septon on “Game of Thrones”; they collaborated by phone and fax.

The opera, miraculously, loses little of the novel’s plot and themes. The book moves fluidly among three time periods: before Gilead; Offred’s training as a handmaid; and her present. So does the opera, with the casual abandon of a film script — rare for an art form typically limited to a handful of set changes, not more than three dozen.

And while the libretto’s language can be frenetic and wordy, its structure is calculated in symmetries between the two acts. The music of the past is carefree and bright; “Amazing Grace” becomes a motif of irony and hypocrisy; the vocal range of Offred, pointedly a mezzo-soprano and not a soprano to emphasize that she is a slave and not a heroine, is narrow and introverted, allowed to soar only in her most private moments.

Working with David Angus, Boston Lyric Opera’s music director and the conductor of this “Handmaid’s Tale,” Mr. Ruders has created a new edition of the score that slightly reduces the orchestration and makes it more manageable for smaller companies.

The libretto, however, remains as difficult to stage as ever. The veteran director Anne Bogart, who casually dropped references to the filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the writer Italo Calvino while explaining her approach to “The Handmaid’s Tale,” is treating the opera as something like a memory play.

She said she envisioned her staging as the experience of wearing virtual reality goggles: The set changes depending on Offred’s perspective, which is, as Ms. Johnson Cano said, “a continuous stream.” Anything not currently on Offred’s mind or in her line of sight simply disappears. That means a lot of set pieces are on wheels, coming and going from a backstage that essentially doesn’t exist.

But a large staff has worked to make the arena as much like a theater as possible. Some things are surprisingly easy: The locker rooms don’t require much to become dressing rooms. And, as every team has a coach in need of an office, so, too, does an orchestra have a maestro.

Carl Rosenberg, an acoustician, has been working on the space, aiming to strike a balance between reflective and absorptive surfaces. But everything he does is ultimately speculative: The results won’t be known until the room has an audience.

What he most wants to avoid, he said, is a dead sound for the voices. If no one can hear Offred, there’s no opera. As Ms. Bogart said, “The Handmaid’s Tale” occupies a big world, but it’s really the journey of just one person.

“It’s the human heartbeat at the center of this,” she said, “that makes you care.”

The Handmaid’s Tale

Sunday through May 12 at the Lavietes Pavilion, Boston; blo.org.

#entertainment news internships summer 2019#entertainment news movies#entertainment news on e#EntertainmentBook#entertainmentunit#s.m entertainment news

0 notes

Text

WIP: Ghost Stories On Route 66

aka the one in which Hanzo Shimada is an expatriate student of the Fine Arts, attending college in what he assumes to be a reasonably sedate corner of the American southwest. Jesse McCree is an occasionally leather-clad NPS ranger whose duties extend somewhat further than shooing lost tourists back onto the clearly marked hiking trails. Something weird is going on in the desert south of Santa Fe and their lives unexpectedly come together in the middle of it.

Entertaining mythological notes!

* In Navajo legends, Coyote occupies the cosmological slots that include “the Chaos necessary to give Order its contrast and meaning” and “complete asshole who is totally more trouble than he’s worth” and “cultural hero who may or may not be more trouble than he’s worth but, in any case, trouble.” Great Wolf is a protector but Coyote is his cousin -- in fact, the Navajo word for “coyote” literally means “little wolf” -- and Fox is cousin to them both.

* There are no coyote subspecies native to Japan but in Shinto cosmology, Wolves and Foxes are guardians, tricksters, and teachers, kin to each other, and servants/messengers of the gods when they’re not gods in disguise themselves.

The light that enfolded him faded slowly to gray and then to dark. The warmth that enfolded him faded slowly to cool, and it was the touch of something far colder on his eyelids that prompted him to open them. The wind that kissed his face also lifted the hair from his shoulders, heavier against his scalp than it had been in years, shining a pure and perfect white in the light shed by the river of stars arching across the sky overhead, bowing down to touch the peak of the mountain looming far in the distance before him. A cloak of red and gold lay over his shoulders and a glittering silver path lay at his feet and he stepped upon it and began walking. He did not look back; he knew that there would be nothing for him if he did.

He walked for perhaps forever or perhaps less, and came to a place where the path became a narrow pass between two high cliffs. The shadows lay deep between the walls of stone but in those places where the starlight touched, the white of age-bleached bone shone among the drifting sand, here the unmistakable curve of a shattered human skull, there the fragments of broken human ribs. He sensed within those high bloodstained cliffs a cruelty and malice beyond even humanity, a hunger for blood and flesh that could never be sated. He sensed also that it slept, bound by a will both ancient and strong, and so he walked through the Rock-Monster Pass unharmed.

He walked again for long or perhaps not long at all, and came to a broad plain that extended as far as he could see and beyond even that. In reeds the plain was covered, as tall as a man with great leaves upon them. The wind sang through them and the leaves struck against one another with a sound like the ringing edges of knives, from their tips blew tassels of dried human skin, sere human flesh. He sensed within those waving reeds a savagery and bloodthirst beyond even humanity, a hunger for blood and flesh that could never be sated. He sensed also that it slept, bound by a will both ancient and strong, and so he walked along the Slashing-Reed Path unharmed.

He walked and before he knew that time or distance had passed, he came to an open valley. Cane cactus grew along its sides and across its flat, crowned in masses of sweet-smelling flowers and limned in thorns the length of a man’s hand, glistening with poison. Long strands of human hair hung from their hundreds of barbs and at their bases lay a tumbled scree of many fallen bones. He sensed within those spiny branches a hatred and spite beyond even humanity, a hunger for blood and flesh that could never be sated. He sensed also that it slept, bound by a will both ancient and strong, and so he walked through the Poison Cactus Country unharmed.

He walked what only seemed a few minutes before he came to a barren land of rolling dunes, sand piled in waves taller than a tall man’s head. The wind whistled along them and stirred from beneath them the ashen remains of many who had struggled to escape and burned, shriveled to nothing. He sensed within those sparkling sands a wrath and wickedness beyond even humanity, a hunger for blood and flesh that could never be sated. He sensed also that it slept, bound by a will both ancient and strong, and so he walked through Burning Sands Desert unharmed.

And so it was that he made the rest of his journey towards the far star-touched mountain and came at last to the forest that gathered at its feet. There in the shadow of the pines, just off the path itself, he saw a flicker of firelight and heard the sound of a sweet voice singing and all at once the cold and weariness of his long journey fell upon him and he found he could go no further.

Another traveler sat in the shadow of the pines feeding sweet-smelling wood to a gentle, warming fire and, coming closer, he found that he knew the traveler’s face but could not say why. The traveler looked up as he approached, a smile more warming than the flames curving his mouth, and his eyes shone golden in the dark. “You’ve come a long way just to see me, cousin.”

“I...have?” Hanzo asked, and for the first time realized his journey had a purpose. “Who are you?”

“A friendly face in the cold and lonely dark, I hope.” The traveler said, lightly, and Hanzo knew the name belonging to that face, but not the name of what looked out through his unnaturally bright eyes.

“You are not Jes -- the ranger that I know.” Hanzo replied and stayed where he was on the far side of the fire. “Who are you?”

“Will you not join me by the fire, cousin?” The traveler murmured, and stirred the pot sitting in the coals, releasing a fragrant burst of steam. “You are cold and weary, and I have warmth and comfort to offer you.”

“You call me cousin but you are no kin of mine that I know.” Hanzo replied and held his ground. “Who are you?”

“Ah, Hanzo Shimada, the things you don’t know yet could fill an ocean.” The traveler grinned and caught Hanzo’s eyes with his own and he felt himself touched by a will both ancient and strong -- touched, but not bound. “I think, my stubborn young friend, that the more important question here is who are you?”

“I...do not know what you mean.” Hanzo whispered and shivered as the cold settled into his bones.

“Oh, I think you do.” The traveler stirred the pot again, and poured a stream of fragrant liquid into the bowl he held. “Sit, child. Warm yourself and drink. Stop thinking of all those faery tales you heard as a boy and attend to the here and now.”

Hanzo came closer and sank down next to the fire, gathering the red and gold cloak that was not his closer around himself, and accepting the bowl the traveler handed to him. It was sweeter than the sweetest honey and more bitter than the ashes of ten thousand broken dreams and he knew, as he drank it, he would never taste anything like it again. He sat silently for a long moment, and allowed the warmth of the fire and the warmth of the drink soak into him, and when he spoke it was softly. “I know who I am, stranger.”

“No. I think you do not.” The traveler stretched his long body out on the ground on his side of the fire, and for the first time Hanzo saw that the tips of his fingers ended in claws. “I think you know who you thought you were -- who you thought you were meant to be. You came here to this place you had only read about it books because you thought you would find it as barren and blasted and empty as you felt in your own soul...and instead the desert is alive in ways you never could have guessed. You came here to wither alone into the nothing you thought you were.”

“I am nothing.” Hanzo replied, and gazed down, his reflection dark in the surface of the traveler’s strange drink. “I could do nothing to protect myself. I endangered the lives of my friends and my brother and could do nothing to help them. Minamikaze was correct -- I am not a dragon, and I will never be one.”

“There are more things in this world than dragons and nothing, my cousin. There is more in you than that.” The traveler’s hand cupped his chin, claws gentle against the skin of his cheek. “And, for the record, Minamikaze is a judgmental asshole who’s been right exactly twice in his entire existence and when next you see him, you can tell him I told you that.”

Hanzo choked on something halfway between a laugh and a sob, and the traveler’s fingers brushed the tears from his face.

“You do not know who you are, cousin. But you have chosen the path that will lead you to the where and the when that you will.” Warm lips brushed his forehead. “You need only the courage to walk it.”

“I -- “

In the distance, a howl rose, sharp as the edge of a knife and cold as death. The wind stilled before it and fled, the boughs of the pines overhead and the ground beneath them shivered, and the flames of the fire itself lost their warmth.

“The Serpent-Wolf hunts you still, hungry as only a thing that has tasted of your soul and now your flesh can be. For the sake of the one who lent you this, I think you should, perhaps, not meet him just now.” The traveler stroked his hand down the golden border of the cloak and seized his wrist in a taloned hand. “Wake up, cousin. We shall speak again.”

The traveler’s claws bit deep, drawing blood.

*

Hanzo jerked awake and the first coherent through to crawl out of the swirling morass of inchoate madness that was his mind was, I know that ceiling.

He did, in fact, know it: large wooden beams, carved their lengths with repeating geometric motifs painted particularly vivid shades of red and gold, white and ocher, paler latillas perpendicular and he was totally looking up at the ranger’s bedroom ceiling for the second time that week and his head spun savagely with the disorientation of it. He was looking up at the ranger’s ceiling. He was laying in the ranger’s bed, wrapped in the ranger’s wonderfully soft and warm sheets and comforter, his head resting on the ranger’s pillows, and he had absolutely no memory whatsoever of how he came to be there. In fact, the very last thing he could consciously recall was the sensation of being shot.

He lay perfectly still for a moment and took stock of the contents of his mind. Yes, that was a rather vivid and unmistakable memory of catching a couple very real and sincere bullets in the midst of an otherwise surreally horrific dinner hour at the Student Union. Moving slowly, he peeled back the covers and pulled up the hem of the tee he was wearing, expecting blood and pain and bloody pain to ambush him at any moment and found, to his pure and perfect astonishment, absolutely no physical suggestion of anything untoward whatsoever. No bandages, no blood, not even a powder burn where the ranger had held the barrel almost flush with his body and pulled the trigger. His arm, on the other hand, was wrapped in lengths of cloth dressing -- each finger individually, feeling too thick and clumsy to use properly, and up beyond the hem of the sleeve, the skin feeling prickly enough as he moved to discourage even thinking about unwinding any of it.

A sound caught his ear: something halfway between a deep breath and a gentle almost-snore. Given the precise gravity of recent events, it was with only a relatively small amount of surprise that he turned his head and found Zenyatta laid out next to him, deeply and comfortably asleep from the quality of his breathing. Beyond him, half-sitting, half-slouching in one of the ranger’s heavy old wooden chairs, his feet propped up on the far side of the bed, was Genji, his head thrown back and his neck crooked at an angle incompatible with human contentment. One of the ranger’s ceramic mugs, probably containing the world’s most powerful sedative tea, sat on the bedside table at his elbow, or possibly four times the average dosage of pharmaceutical-grade ketamine, or possibly both.

For an instant the relief of seeing them both there, safe and unharmed, rose up in his chest and made his head spin, and it was all he could do breathe around it.

#WIP Ghost Stories On Route 66#This chapter is for all of you#You know who you are#Who want Hanzo to be safe#And also for me to hurt him#You've been warned

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bowers on collecting: Among my favorites — Sacagawea “golden dollars” part three

By Q. David Bowers

This week I continue and conclude my discussion of Sacagawea dollars. In 2000 they were released to the general public amid much publicity. Collectors loved them, but citizens ignored them. Vending machines would not accept them, most stores did not have a cash register space for dollar coins, and the Treasury Department’s hope that the sturdy coin with a life expectancy of 20 years or more would replace the paper dollar never came to be.

The obverse of the 2017 Native American dollar. Hover to zoom.

That the spotting and staining of coins due to Mint coinage and rinsing added to their “Antique” appeal, as the Treasury suggested, was certainly novel. Come to think of it, this explanation is nicer than the “environmental damage” label used by certification services! That said, the fact remained that many dollars became ugly after a small amount of handling. In time, processes were refined and problems diminished.

Continuing the story:

Sculptor-artist Glenna Goodacre received her $5,000 payment for designing the obverse in the form of as many Sacagawea dollars, but with a specially burnished and treated surface—unexpected by her and unannounced in advance. These proved to be a bonanza.

Goodacre was inducted into the West Texas Walk of Fame in 1997. Photo by Billy Hathorn.

This special surface was created when the Mint realized that if the coins given to Goodacre were publicized and sold—as they surely would be as she did not need 5,000 of them personally—it would be very embarrassing if they became stained and spotted, as likely would be the case. Accordingly, a special burnished finish, very distinctive in appearance, was applied to most of them. These coins were put up in cloth bags, resulting in some bagmarks, but not extensive.

These were delivered to her Santa Fe, New Mexico studio by Mint Director Philip Diehl accompanied by two Mint police officers. A special ceremony was held there on April 5, 2000.

Seeking to preserve them from handling the artist had the Independent Coin Graders (ICG) encapsulate them without adding grades, beginning on August 8. Many were later broken out of their holders and sent to PCGS or NGC where they nearly all earned high grades. Goodacre signed some of the holders. She kept 2,000 coins for herself. Nearly all of the others were sold for $200 each. While writing this article I checked the Internet, and a fair number of these are offered from about $500 to $1,000. The ICG coins are not graded, as noted. The PCGS and NGC coins have numerical grades, satisfying those who cannot live without numbers. I enjoy the Goodacre coin I have in my collection, acquired from Jeff Garrett.

Since the year 2000, the primary form of currency used in Ecuador has been the United States dollar.

A Spanish angel (with apologies to Willie Nelson) appeared on the horizon to save the day for circulating Sacagawea dollars—in the form of the country of Ecuador, the popular Spanish-speaking country with close ties to the United States. In 2000 they became legal tender there! Subsequently, hundreds of millions of Sacagawea dollars, unwanted at home, were shipped there. Some recipients thought that the coins were specially designed for them, given the appearance of Sacagawea’s child, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau.

Sacagawea dollars continued to be minted—in quantity at the Denver and Philadelphia mints plus Proofs in San Francisco. Each year I added new issues to my collection.

Surprise! In 2009 the Sacagawea dollar was discontinued.

2009-S $1 Native American, DC (Proof). Image courtesy of PCGS CoinFacts.

Not really, but the Treasury changed the name to the Native American dollar. Sacagawea remained on the obverse as nice as ever, but the reverse was changed to that each year there would be a motif relating to Native American culture.

2000–2008 reverse by Thomas D. Rogers.

To be logical, the original Sacagawea dollars of 2000 onward should have been called Flying Eagle dollars, for the reverse. There was one thing that was and is terrible from a numismatic viewpoint: completely hidden from view when in an album or certified holder, the date and mint mark are on the edge.

Message to the Mint: Change this back to normal practice—put dates and mint marks back on the obverse. After all, coin collectors buy hundreds of millions of dollars of your coins each year.

Full disclosure: I love the Mint dearly, have testified in Congress on behalf of the Mint and the Treasury Department, and at the Mint’s 200th anniversary held in Philadelphia, I was the keynote speaker. I have also advised a number of Mint directors over the years. Please view my message as being constructive and earning your thanks from the numismatic community.

To see all of the Sacagawea and Native American dollars and learn their mintages and prices, not to overlook some new issues (such as West Point Mint strikings), see the latest Guide Book of United States Coins.

Next week: A different subject.

❑

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter!

0 notes

Audio

WE HAVE A NEW SONG!

Gallipoli, according to Zack Condon:

Gallipoli started, in my mind, when I finally had my old Farfisa organ shipped to New York from my parent’s home in Santa Fe, NM. I acquired the organ from my first job at the CCA; the local foreign film theater and gallery space. A traveling circus’ keyboard player (not a joke) had left it in the warehouse after certain keys and functions of the organ had broken down and stopped working. I spent the next three years writing every song I could possibly squeeze out of it. Most of my first record (Gulag Orkestar, 2006) and large parts of my second record (The Flying Club Cup, 2007) were written entirely on this organ as well, where it lived in my childhood bedroom not far from downtown Santa Fe. I enlisted my father’s help to get it shipped out to Brooklyn, then up to my new home at the time in a corner of Westchester on the Titicus reservoir. The house was the caretaker’s home of a mansion owned by a multi-millionaire serving 20 years for tax and money fraud and I don’t know what else. I started writing the first songs of Gallipoli on that organ sometime in late 2016, as the winter started.

Soon songs began to take shape in quick and inspiring ways and I booked a three-week session at a fairly new start-up studio in Chelsea Manhattan, called Relic Room in the deep winter of that year. I brought in Gabe Wax, the producer of No No No, who I felt shared a similar vision sonically as I do, and who I knew was as game as I was to push every sound to its near-breaking point. With the main instruments recorded, with the help of my bandmates Nick Petree and Paul Collins on drums and bass, we proceeded to channel every note played through a series of broken amplifiers, PA systems, space echoes and tape machines, sometimes leaving a modular synth looping in the live room at volumes so loud we had to wear headphones as earmuffs while running into the room to make adjustments to the amplifiers. I wanted every creak and groan of the instruments, every detuned note, every amp buzz and technical malfunction to be left in the cracks of the songs. Even so, the Farfisa organ reappeared, where it was serviced and fixed by a friend of the studio’s over the course of a week so that it was back in working order to add into the mixes of the songs I had originally demoed on it. Ben Lanz and Kyle Reznick, the other brass players in the band, joined us towards the end for an amazing brass session. Ben helped arrange a beautiful brass rendition of a song I had written over a repeating motif on a modular eurorack (which Paul had brought to the studio and introduced me to).

Simultaneously around this time things in my personal life were shifting wildly, and I found myself traveling back and forth between New York and Berlin for longer periods of time. I would visit with my cousin Brody Condon (whom I roped into designing the record cover with me), spent time in the studios of Mouse on Mars (Jan Werner had been staying with me in Brooklyn during trips to New York), and drifted into some amazing concerts and other random events around town. New York had been feeling drained of life after all of its recent development in my mind, and I’d always had a certain personal calling to spend my time somewhere back in Europe ever since I lived in Paris back in 2008. I don’t know if it’s a coincidence that it’s the city that has appeared the most in my lyrics and song titles in the past, but Berlin had always left a deep impression on me one way or the other since the first time I came here 14 or 15 years ago.

When spring of 2017 came I gave in to the call of the new skate park that was built in front of my house in Brooklyn the year before. I had barely spent a week at the park reacquainting myself with the board when I missed a simple trick and fell, breaking my left arm for the fourth or fifth time in my life. I had been floating the notion of a second three-week recording session in the studio in New York in the coming months, but, injured and dejected, I decided to just head back to Berlin and do a lot of nothing. A week or so upon arrival I had what could vaguely be called an epiphany during a cigarette break in Prenzlauerberg and I decided to just pack things up and stay for good.

I got lucky with some private studio space in Berlin pretty quickly and settled happily into the new swing of things. I wrote for another half year, now often on a borrowed Korg Trident and other synthesizers from the owners of Kaiku studios on Stralauer Allee. By the summer of 2017 I was convinced I had enough material for another extended recording session. With the utter shit-show of American politics and the media frenzy surrounding it chattering on, and the prohibitively expensive prices of recording and staying back in New York city, I thought it best if Gabe and the others came out to Europe to join me for the final session. Paul had spent some months during his honeymoon out in Rome getting to know the city and burrowing in to parts of the Italian music scene, where he caught wind of a large studio in a rural part of Puglia, in the boot heel of Italy. We scoped it out and it seemed to be the right amount of isolated, well-equipped and not overbearingly fussy and we decided to go.

So me, Paul, Gabe and Nick met up in the first days of October 2017 in Rome, and hopped on a train to Lecce, Puglia, where we were picked up by Stefano Mancas, the owner of Sudestudio and driven to the studio complex out in the country. Ben and Kyle had scheduling complications due to touring with other bands and projects, so I became determined to dig my heels back into the way I used to do brass on my own and see what could happen.

The next month was a flurry of 12 to 16 hour days in the studio, with day trips around the coastline and a steady diet of pizza, pasta and tear-inducing ghost peppers we bought from the chili-man in Lecce. We stumbled into a medieval-fortressed island town of Gallipoli one night and followed a brass band procession fronted by priests carrying a statue of the town’s saint through the winding narrow streets behind what seemed like the entire town, before returning late to Sudestudio. The next day I wrote the song I ended up calling ‘Gallipoli’ entirely in one sitting, pausing only to eat. I eventually dragged Nick and Paul in to add some percussion and bass around midnight after a trance-like ten hours of writing and playing. I was quite pleased with the result. It felt to me like a cathartic mix of all the old and new records and seemed to return me to the old joys of music as a visceral experience. This seemed to be the guiding logic behind much of the album, of which I only realized fully at that point. We spent the rest of the month in the studio in Italy, eventually finishing the bulk of the album by November.

I returned to Berlin, where I started to put unfinished vocal parts to tape in my own studio whenever I got the chance. At some point I realized Gallipoli was done and flew Gabe Wax into Berlin for a final mixing session at Vox Ton studios, run by Francesco Donadello, a talented engineer and musician working deeply in analog equipment and experiments, and funnily enough, a good friend of Stefano Mancas from Sudestudio. After the Vox Ton session I mastered the record with Francesco at Calyx, not far from my own apartment in Berlin.

Zachary Condon

Berlin, Aug 2018

0 notes

Text

What To Know About Custom Home Builders

By Diane Lee

The modern residents of this era all enjoy many things. These are among the most advanced of appliances or installations that are have qualities that make them smart. Customization tends to be seen as high end or something that are only for those who can afford but you might be surprised how a service like this will be affordable, which is the thing with advanced technology these days.

It is mostly a tech function, all the concerns for changes that have made the industry better is all here, including better materials. Outfits like Custom Home Builders Santa Fe NM for example issue this kind of thing. These are able to come up with the best alternatives you the consumer can have to improve your house structure.

The consumers of course will need to study any type of service to match up with their specs or preferences. The contractor process being discussed is primarily concerned with customizing any new project that will eventually create amazing homes. But the contractors can also provide services to those who wish their homes renovated or rebuilt.

The renovation process is often seen as an overall one especially with structures that are older and were not customized. This will tend to create seemingly totally new buildings. The materials or installs in the old structure will rarely remain unchanged, and some could even be torn so all the important things are built on the foundations.

Customization could sound very fancy for many, but this could have all sorts of important structural add ons, and you could try the modern service today. For example, there may be new or advanced stuff that all homeowners could want today, those providing those qualities for the modern home like green design, advanced tech and a structure with continuity.

These qualities are interrelated and the custom built structure can have all these working together. The integration is something that is generally available to anyone, and the customization means having these qualities answer to things like geography, climate, scenery and materials or energy availability in any given area.

Some subdivisions or housing developments often share these things, and if these do then customization will simply incorporate client preferences. Then the designs and architectural styles come to the fore. And so will things like specific electronics, home security systems, alternative energy sources, ergonomic installs on the inside and outside and such.

This will actually be complex but tech in this sense has actually helped construction streamline things and make them affordable. There will be reduced need for purely decorative items, which could only be attractive and no more. Anything attractive these days usually have their own qualities for strength and usefulness, including added insulation or weatherproofing.

This means that the custom built house is something of a needed item for the future. Plus, there is good placement for this structure to be eventually considered among the top items on the market later on. Maintaining it will require work but not any more than those that are made with general or standard designs and motifs which might not have the advanced qualities this will have.

About the Author:

Get a summary of the factors to consider when choosing custom home builders Santa Fe NM area and more information about an experienced builder at https://ift.tt/2yTDqDy now.

What To Know About Custom Home Builders

from 10 first best of https://ift.tt/2ujXV76

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Grand Canyon National Park

Grand Canyon National Park

Grand Canyon, Arizona

Tuesday, June 12, 2018

Clear, 95°

“The wonders of the Grand Canyon cannot be adequately represented in symbols of speech, nor by speech itself. The resources of the graphic art are taxed beyond their powers in attempting to portray its features. Language and illustration combined must fail.” - John Wesley Powell

After the little hike at Horseshoe Bend it was only a couple hours’ drive to The Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in Arizona. Words like Grand, Massive, Oh Wow, and Impressive cannot truly describe The Grand Canyon. Its massive size overwhelms the senses. It is 277 miles long, up to 18 miles wide and attains a depth of over a mile (6,093 feet).

Grand Canyon Sign

The canyon and adjacent rim are contained within Grand Canyon National Park, the Kaibab National Forest, Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, the Hualapai Indian Reservation, the Havasupai Indian Reservation and the Navajo Nation. President Theodore Roosevelt was a major proponent of preservation of the Grand Canyon area, and visited it on numerous occasions to hunt and enjoy the scenery.

Distant Canyons

Nearly two billion years of Earth's geological history have been exposed as the Colorado River and its tributaries cut their channels through layer after layer of rock while the Colorado Plateau was uplifted. While some aspects about the history of incision of the canyon are debated by geologists, several recent studies support the hypothesis that the Colorado River established its course through the area about 5 to 6 million years ago (*Wikipedia)

Grand Canyon

On the South Rim side of the Park, there is no need to drive around in traffic. Park your car or RV and ride the free shuttle buses around the village and out to scenic overlooks. The drivers are funny and very helpful getting you to where you want to visit and offer great hints to get more out of your visit. I am not sure what the North Rim has for services but know it is higher in elevation and more remote.

Grand Canyon toward East

Coming in from Page, Arizona through the east gate, the first stop on the eastern end of the South Rim is the Desert View Watchtower, built in 1932. It is one of Mary Colter's best-known works. It is 27 miles from Grand Canyon Village; the tower stands 70 feet tall.

Desert View Watchtower

The top of the tower is 7,522 feet above sea level, the highest point on the South Rim. It offers one of the few full views of the bottom of the canyon and the Colorado River.

Colorado River Below

It was designed to mimic Anasazi watch towers, though, with four levels; it is significantly taller than historical towers.

Desert View Watchtower interior

Mary Colter (April 4, 1869 – January 8, 1958) was an American architect and designer. She was one of the very few female American architects in her day. She was the designer of many landmark buildings and spaces for the Fred Harvey Company and the Santa Fe Railroad, notably in Grand Canyon National Park. Her work had enormous influence as she helped to create a style, blending Spanish Colonial Revival and Mission Revival architecture with Native American motifs and Rustic elements; that became popular throughout the Southwest. (*Wikipedia)

Plaque on top of Tower

Desert View Watchtower gives you another “Oh Wow” moment with the full view of the Canyon below. As you look out for miles on end, the Canyon is before you to the west and the high plains of the Colorado Plateau are toward the east. The vibrant colors of the Canyon, even in mid-day, gives a depth and saturation only dimmed by the slight smoke of the forest fires in Colorado several hundred miles away.

Colorado Plateau

There were a couple of Navajo vendors inside the Tower who were giving cultural information while making their crafts. They were doing wood and stone carvings with several work stations set up for visitors to watch them work. Both were very informative and answered questions while they worked.

Grand Canyon - Another Oh Wow Moment

Driving the twenty five miles along the South Rim to the Grand Canyon Village, there are multiple places (overlooks) to stop for views and photo opportunities of the Canyon below. At each pull out, several vehicles made a daisy chain caravan stopping for photos. It was slightly funny to watch everyone get out, look for a couple minutes, snap a few pictures and head out to the next one. This went on for the whole twenty five miles to the Village.

North Rim Horizon

Approaching the Village, it suddenly got really crowded as the Parks Service had quite a bit of road construction going on. Several roads were being repaved so crews were directing traffic into single lane passes as the crews stripped the old pavement and filled in so the new surface could be poured and smoothed out. Like most Government projects there were quite a few workers with many standing around, several operating heavy equipment, and several supervisors talking to each other. It will probably be a long summer of work . . . maybe with the high temperatures and tourists all over the place it would be a great idea to work night shifts. More work could be done with less people driving by, there would be cooler temperatures to work in, and you would be a little more productive in the process by getting more miles of pavement put down. Oh well, that would be too easy, just an observation from years of construction projects. (Rant over)

Getting to the Village Campground, finding a place to park, and waiting in line to talk with the Camp Registration office, it was slowly learned that I had not booked at that campsite. With a little digging in the Parks computer system and me looking at emails from March it was discovered that when looking to book, everything was full and I had booked just off site at a campground with a similar name. It was about this time that I really felt like an idiot but the lady assured me that it happens almost every day.

It was time to get back in the RV, turn around, hit traffic again and find the way to the Park entrance and drive a mile down the road to the new campground. This one was expecting me so check-in went smoothly and it was time to set up for another night in paradise.

As I was setting up the RV for the night I could hear that familiar “Whup, whup” sound of helicopters flying about. The campsite was along the return path of flight seeing helicopters on their way back to the airport about a half mile away. They must be doing a great business as there were choppers returning to the airport in sets of six or eight returning about the same time with the process repeating about every twenty minutes or so all afternoon. The campground had two elk that grazed across from the RV and five to ten more were further back in the campground. I believe they live there and stay in the area as several people said they were there every morning and afternoon eating till the sun went down.

It was about six hundred feet to walk to the shuttle bus stop outside the campgrounds so it was easy to make our way back to the park to view the sunset. The bus driver, Trey, was entertaining and talked about the smoke in the Canyons today. He said he had property in Durango, Colorado and knew all about that fire. It was started by the narrow gauge railroad that operates in the area and that the fire was still not close to being contained. He chatted with an Asian family who was also on the bus. He gave specific directions once getting off the bus on the fastest way to get to the Canyon rim for the best photo shots in the area.

The sun was just setting, giving an orange glow to the western horizon. The walls of the Canyon to the east were highlighted by the Alpenglow of the sun and gave nice details between light and shadow on the cliff face.

Afternoon Sun

There were several overlooks in this area around the Village and all were full of people snapping photos of every cliff and overlook.

Afternoon Vistas

At one glance I could see about forty phone screens illuminated, held high taking photos or selfies on one ledge overlook.

Sunset 1

It was kind of humorous seeing everyone running around trying the get that great shot of the sunset or the Canyon walls all aglow. You could hear the quiet voices of many different languages talking, a true international gathering of people celebrating the same thing, a beautiful sunset.

Sunset 2

Everyone stopped in awe of another day’s passing into night, shadows, and darkness.

Sunset 3

The bus driver also told us about the Grand Canyon Star Party that is held each year in June. Due to its dark skies and clean air, Grand Canyon offers one of the best night sky observing sites in the United States.

Evening Star

Grand Canyon Star Party

For eight days in June, park visitors explore the wonders of the night sky on Grand Canyon National Park's South Rim with the Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association and with the Saguaro Astronomy Club of Phoenix on the North Rim. Amateur astronomers from across the country volunteer their expertise and offer free nightly astronomy programs and telescope viewing.

Through the telescopes you might view an assortment of planets, double stars, star clusters, nebulae and distant galaxies by night, and perhaps the Sun or Venus by day. At the 2018 Star Party, Jupiter and Saturn will be evening highlights, but you might find an astronomer pointing a telescope at Venus in the early evening. Mars will rise just after 11 pm for those staying late in to the evening. (NPS information)

There were between fifty and seventy-five telescopes set up in the rear parking lot of the Village Visitors Center for the public to view the heavens once darkness set in. As the sun’s glow on the horizon was quickly diminishing the planets and stars were appearing across the night sky. Most telescopes were set up to view Venus and Jupiter as those were visible as soon as darkness set in. It was great seeing Jupiter and four of its moons so clearly through several telescopes.

We waited for this one man to set up his eight or nine foot tall telescope so we could view whatever he was going to point too. It was funny because he had trouble locating the North Star so he could calibrate his telescope but I and another by-stander showed him where it was. He spent about twenty minutes zeroing in his instrument before he was ready to view the stars. When he was finally locked on to his target it was a star nebulae cluster. It was beautiful, having the appearance of something like the Milky Way. You had to climb up on a ladder to get a view through the lens of his telescope.

It was a beautiful high desert evening, cooling off nicely once the sun dropped below the horizon. It probably dropped 10 degrees in about thirty minutes or so. The bus driver reminded everyone that the last shuttle from the Visitors Center left at 9:30 so stargazing had to be put on hold but it was hard to leave then as the stars were just beginning to pop out all over the heavens.

Walking across the parking lot where all the telescopes were set up, looking west there was a sudden burst of exhilaration from the crowd as a shooting star appeared to the right and fell in a beautiful greenish arc across the sky to the left. It was if the astronomers had ordered this beautiful light show. The crowd continued in an excited state for several minutes hoping another one would fall.

Taking the shuttle bus back, we had the same driver, Trey. Two young men (boys really) about twenty years old started to get onto the bus toting their bicycles. Trey said to them loud enough for anyone on the bus to hear, “Does it say anywhere that bicycles are allowed “In” the bus?” They stepped back off and started to go to the rear of the bus when he called out again to them, “I’ll give you a hint, not that way guys!” They stopped, turned around and went to front of the bus where a large bike rack was attached to the bumper. The boys, looked at it, looked at each other puzzled wondering how to attach their bicycles. Trey got off the bus and happily showed them how to operate the simple hold downs for quick loading and unloading of the bikes.

As he spoke about bicycles being allowed “In” the bus, this Hindu family just cracked up and was excitedly talking back and forth while the bicycles were loaded on board. As the two young men entered the bus, the family continued talking excitedly; they seemed amused that the boys were finally able to get on. Their son who was about nine or ten started asking Trey all kinds of questions about the Park, the Canyon, many types of animals and more. Trey told the mom and dad they needed to get this young boy some books as he “had wheels and was going somewhere with his life!” He asked the boy why he knew so much about the Grand Canyon and the area. The little boy answered, “I Googled it!”

A little comedy, beautiful sunset, the Heavens opening up with stars, and seeing a meteor fall close by, made for a very memorable day Traveling Life’s Highways.

#Grand Canyon National Park#Grand Canyon#America#America the Beautiful#Beautiful Places#Grand View Watchtower#Interesting things#Interesting places#Travel#Traveling Life's Highways#Road Trip#RV'ing#Veterans

0 notes

Text