#which would allow him to adequately fight and defend himself despite his blindness

Text

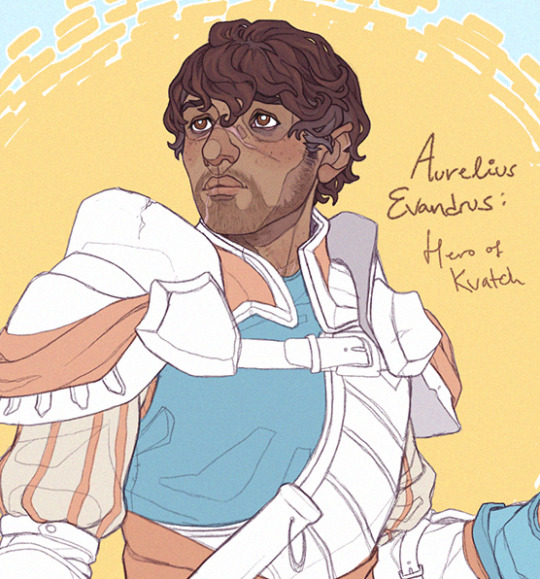

Even though my gaming laptop is dead and I can't replay Oblivion rn, I've decided to design a new Hero of Kvatch anyway that fits into the same universe as my other heroes. And since my Nerevarine and Dragonborn are both women, I figured I should buck the pattern and throw a guy in there lol. His whole vibe was equally inspired by both ancient greek / roman busts and Moses from Dreamwork's Prince of Egypt.

I've always liked the trope of blind characters with the ability of precognition, which is what I decided to explore with Aurelius--likely the result of an ill-advised bargain with Clavicus Vile on his father's part. The man wanted himself and members of his family to be "noticed and recognized by those in power", though failed to foresee that this would apply to more than just kings and nobles. In fact, turns out that drawing the curious eyes of several Daedric princes isn't ideal for the wellbeing of your unborn child, and Azura's boon of prophecy doesn't exactly play nice with bouts of madness and delusion...party favors from Sheogorath and Vaermina.

Haven't fleshed him or the story out much, yet, but y'all know how I am: always happy to add another softboy to my roster lmao I promise I know how to draw / write men who aren't in some way soft but can't say I'm interested in doing that

#tes oc#tes ocs#tes imperial#oblivion oc#tes oblivion#elder scrolls oc#elder scrolls#these are MY blorbos goddamnit and I'll churn out as many hardgirls and softboys as I want#side characters may be different but I just don't like writing main characters that line up with a bunch of the conventions of their gender#but yeah Re's probably going to fall into paladin territory#and the barefoot thing is kind of inspired by toph's ability to 'see' via what she can feel and touch#which would allow him to adequately fight and defend himself despite his blindness#same goes for the fingerless gloves#art#my art

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

GAMES NIGHT

(Bai Lin/Luohou Jidu 1000 words drabble)

“Okay guys, you’re on in 3…2…1… Go!”

In the deafening noise and the blinding lights, already feeling the weight of the armor pieces encircling his torso, forearms and calves, Bai Lin finally started to low-key question his decision. If only he had waived off this stupid challenge, surely his friends would have conceded for a more embarrassing but less hazardous punishment? He'd never know and now it was too late to back down.

At least he hoped for a silver lining - these fantasy extreme sports for amateurs or whatever the hell they were called seemed to be a popular novelty and he could maybe write a good article about his own experience with it.Technically the matches had the adequate safety measures, all weapons used were blunt and the risk of sustaining serious injury was minimal, still he regretted not thinking of taking part in a rehearsal practice before, if only to get the better hang of it.

Bai Lin was rather confident because he'd taken some fighting classes back in high-school and the long sword felt comfortable enough in his hand, but he and the other two fighters making up his three-people group had never come together before so they weren't a team per say. Also, the large audience of the arena, the heavy, unfamiliar period costume and the atmosphere as a whole had proven quite overwhelming.

Sparkling white sand scrunched under his boots as their small group was guided by a referee towards the center of the large arena while a presenter had started to relay the 'backstory' of the upcoming match through the speakers. Bai Lin was a media man himself and wouldn't argue with people's choices of entertainment, but he was finding this particular concept both ridiculous and complicated; as such, most of it flew by his ears without sticking, except for the part that his team - with white tunics and silvery armors and long swords- were supposed to be celestial soldiers defending some magic gate against a horde of nefarious Asuras.

Their opponents had bronze gilded armor pieces and matching swords, and two of them were black-clad and their faces half-hidden by black hoods. It fully dawned on Bai Lin how poorly prepared his ‘team’ was when they parted to make way for a third guy who must have been their leader, judging by the crimson shade of his tunic and cape and the ornaments on the breastplate. Fuck, he really should have done his homework before jumping into this shit headfirst.

Mildly annoyed, he took a step to the forefront and his teammates gladly allowed it, quickly moving behind him, and Bai Lin let out a huff, eyes on the man who was walking forward with slow steps, eyes still on the phone in his hand. He wasn’t armed.

"What the hell is he doing?!" he hissed, not letting the other out of his sight.

The key to winning the fight was identifying the impact points on the opponent’s armor, marked with a different color, which when hit with enough force jammed a mechanism inside the respective armor piece and incapacitated that part of their body. In theory it sounded quite straightforward and relatively easy to accomplish.

"Probably selecting a playlist. You can wear air pods if you want but they're too distracting, I can't imagine how you can-..." one of his teammates explained.

Bai Lin scowled - so the Asura must have been pretty confident, he must have been experienced. But the guy was rather short and didn't look particularly strong either underneath all that equipment. And where was his sword?!

"They look much too calm, let's give them a little roast," his other teammate suggested.

“What? Dude, no-”

"Hey you! I didn't know the mighty Asuras were supposed to be a bunch of pipsqueaks!"

"Oh yeah? Don't beg for mercy later, pretty boy," a voice replied acidly from under a black hood and Bai Lin realized it was a girl's. Despite disagreeing with the rudeness of his own man, the discovery gave him an instant boost of confidence and he gave his sword a demonstrative spin, even as the lead Asura finally looked up at them. His eyes were surprisingly large and dark, lined with makeup of some sort and he even had a black mark finely painted between his eyebrows. If his whole outfit and artifices were supposed to make him look like a tough guy, the effect was almost non-existent. Not only was he lacking the bulk and size for it, but he was pretty, in a glazed cinnamon roll kind of way too.

The guy glanced at all three of them blinking slowly, chin raised and frowning slightly, just as a staff member momentarily approached to take the phone from him. Damn, these guys were seriously into the show, but they were in for a nasty surprise.

Or so he’d thought, because the very moment the gong was hit, several things happened in rapid sequence; his two mates pushed past him and charged forward with zero coordination and the two hooded Asuras fell back quickly several paces, while Bai Lin noticed a stage assistant throwing something to their leader.

He only saw that it was a modified, double-bladed guan dao when its wielder had already given it a wide swing, taking them completely by surprise and already hitting one of the two celestial soldiers in the leg guard. The man stumbled brusquely and dropped on his knees, and then one of the other Asuras pounced on him.

Their strategy was simple but ruthlessly effective and things went decidedly south for the celestial team in less than three minutes.

In the end, Bai Lin found himself with his nose in the sand and the outline of his article taking shape in his mind. It wasn’t a completely disastrous night, even if he’d made a fool of himself; still, it would probably take a rematch he should actually win before the cinnamon roll Asura would give him his phone number.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vlad the Impaler between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire

Authors: Ileana Căzan, Eugen Denize

When discussing the complex personality of Vlad the Impaler, we believe that there are two fundamental issues that need to be addressed and two questions that require an answer based on a thorough analysis of the data and facts available to us. The first question is whether or not Vlad the Impaler was a bloodthirsty tyrant, ready to kill for the simple pleasure of seeing innocent blood spilled. We believe that this question can be adequately answered by looking at how his war with the Turks began in 1462. Was Vlad Țepeș, a bloodthirsty tyrant, acting under the blind impulses of unleashed instincts and unjustifiably provoking the Turks, or was he obliged to wage war against the great Ottoman power under conditions unfavourable to him but imposed on him by the course of events?

Secondly, despite his bravery and the sacrifices he made fighting for his own people and for Christianity, Vlad the Impaler fell victim to the propaganda and misinformation that Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, unleashed in the West to justify his inaction in 1462. That the King of Hungary resorted to less than chivalrous methods, incited and supported by the Saxons who could not forgive the Highlander for his actions against them, is easy to understand. But how does one explain the great success of these lies, which have survived through the ages and helped Bram Stocker's literary creation and fantasy to transform the hero of the anti-Ottoman struggle into a true model of the vampire, the famous Dracula? Matia Corvin's propaganda power was not enough for this, but it received unexpected and essential help from the most informed power of the time in relation to the Ottoman Empire and the general political life of Europe, from Venice, a true bridge of contact between East and West, not only in economic terms but also in terms of information. The credit given by Venice to the untruths propagated by Matthias Corvinus, even though it knew exactly the political reality of the Lower Danube, ensured their particular success, because the other Christian powers were much less informed and interested in the situation in this part of Europe and therefore had no reason to dispute what the Venetians accepted as true. All these problems, questions and possible answers will be dealt with in the pages of this chapter, as far as the available documentation allows.

As far as Vlad Țepeș is concerned, whether he took over the reign between 15 April and 3 July [1] or in July-August [2] or at the end of August 1456 [3], the fact is that he did so with the help of Iancu de Hunedoara, at a time of maximum clash between his armies and those of Mehmet II, the conqueror of Constantinople, who was also preparing to conquer Belgrade, the key to Hungary and Central Europe. By ascending the throne of Wallachia at such a time, he could only be the exponent and continuator of the anti-Ottoman political line advocated by Iancu, as is clear from the act, dated 6 September 1456, in Targoviste [4], in which he offers to help, with all his powers, Hungary against the Turks, from the letter sent to the Brașovs from the same place on 10 September [5], and from the help he would give to Stephen the Great to take over the throne of Moldavia in the spring of the following year [6]. In spite of these intentions and deeds, due to the premature death of Iancu de Hunedoara, which significantly changed the political situation in the Romanian area and not only here, Vlad Țepeș was obliged to pay his tribute regularly to the Porte [7] , until 1459, when he stopped doing so, invoking to the Sultan the conflictual situation in which he found himself with the Saxons of southern Transylvania and the Hungarian king Matia Corvin [8] . The truth is that, obliged to respect the Turkish-Hungarian co-residence established over Wallachia by the armistice concluded by Iancu de Hunedoara with the Sultan on 20 November 1451-13 April 1452 [9] , Vlad Țepeș never reconciled himself to this situation and tried to manoeuvre between the two powers with the ultimate aim of opposing one another and easing the situation of his own country [10] .

Here we believe it is appropriate to bring into question the way in which the war between Vlad Țepeș and the Turks started, whether Vlad Țepeș started this war driven by reprehensible bloody instincts or whether he was forced by circumstances to accept a war with the great power south of the Danube, a war that could only be total, in the sense that this word can have for the time, if he wanted to achieve victory and save the country from total disaster. We believe that there are three essential aspects of the moment of the real rupture between Vlad Țepeș and the Ottoman Porte, aspects that must be analysed very carefully.

Of course, Vlad the Impaler was determined, right from his accession to the throne, as we have shown above, to pursue an anti-Ottoman policy of defending autonomy and state integrity, but this policy could not be pursued under any conditions and at any risk. Vlad Țepeș, as a good politician and a remarkable military commander, realised that to start the fight against the Ottoman colossus meant waiting for the most favourable moment, when his reign would be strengthened internally, and externally he could hope for help from other countries also interested in the anti-Ottoman struggle. But let's look at the three key aspects of this problem.

First of all, there is an alleged expedition of the vizier Mahmud Pasha against the Romanian Country, which two Italian sources place in 1458 [11], but, in fact, there is a chronological error [12], which excludes the hypothesis of a clash between Vlad the Impaler and the Ottomans before the winter of 1461-1462.

Secondly, in our opinion, the cessation of the payment of the tribute of 10,000 ducats per year [13] did not signify an immediate and irreparable rupture with the Porte as is considered in a number of more or less recent works [14] . If things had been different, if Vlad Țepeș had openly broken off relations with the Porte, Sultan Mehmet II, who wanted to mark each year of his reign with a new conquest, would probably not have hesitated to attack Wallachia. But what did he do until 1462? In 1458 he conquered a large part of Moreea [15] , in 1459, the year Vlad the Impaler stopped paying tribute, Mehmet II conquered Semendria and all that remained of the Serbian state [16] , in 1460 he completed the conquest of Moreea [17] , and in 1461 he conquered Sinope and Trapezunt [18] , the last remnants of the Byzantine Empire. In our opinion, the Sultan and the rulers of the Porte did not interpret the non-payment of tribute as an act of hostility, nor did Vlad Țepeș have any interest in deliberately provoking the Turks at a time when he was in open conflict with the Saxons of southern Transylvania and the Hungarian king, Matia Corvin [19] , who supported hostile claimants to the throne and Bohemian groups. Through this conflict, which was also determined by important economic aspects [20], but dominated, above all, by political causes [21], Vlad Țepeș sought to achieve two objectives that were absolutely necessary to be able to fight successfully against the Porte: the internal consolidation of the state and the institution of the reign and the affirmation of the independent position, de facto, of the Romanian Country against the claims of suzerainty of the Hungarian royalty. Both objectives were achieved by the treaty concluded with Brașov around 1 October 1460 [22] . The 1460 reconciliation between Vlad Țepeș and the Saxons unquestionably restored to them the commercial freedom in Wallachia suppressed during the conflict [23] . The reconciliation also took place in the context of Vlad Țepeș's return to the alliance with Hungary, in the preparation of the anti-Ottoman action, which remained, all along, the dominant direction of the Romanian prince's foreign policy.

Thirdly, in our opinion, the Turks begin to show distrust and hostility towards Vlad Tepes only in 1461, during or immediately after the end of the expedition against Trapezunt and, in this situation, having no other choice, the lord decides to take open action against them in the winter of 1461 and 1462 [24] . He considered himself to be fairly strong internally, he realised that a confrontation with the Porte had become inevitable, especially after the unsuccessful attempt to capture him at Giurgiu, and he was also counting on possible external support that could come either from the eastern enemies of the Ottoman Empire or from Matthias Crovin, or from Venice, because the time for the formation of an anti-Ottoman coalition including all these seemed very near, despite the failure of the Congress of Mantua in 1459, at which Pope Pius II (1458-1464) had hoped to set up a great anti-Ottoman league, with the broad participation of the Christian powers [25] . It was decided here, among other things, that the Christian army would be led by the Duke of Milan, Francesco Sforza, and the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good [26], but the decision would have no effect.

The contemporary chronicler Laonic Chalcocondil states that Vlad Țepeș did not start the anti-Ottoman struggle until he felt that the situation in Dacia was secure, and this happened after the Sultan's campaign against Trapezunt in the winter of 1461 and 1462 [27] . But let us see what were the elements that led to this rupture and to the great confrontation of 1462.

In the second half of 1460, Vlad the Impaler re-established good-neighbourly ties with the Saxons of southern Transylvania, as we have shown above, and concluded a secret treaty with Matthias Crovin [28] , which provided, among other things, for his marriage to a relative of his [29] . Also in this year, a soldier of the eastern princes of Georgia, Mingrelia, Guria, Trapezunt and Uzun Hasan, the Turkoman ruler of Persia, crossed the Danube to Hungary, who were preparing to attack the Ottoman Empire and were looking for allies in Europe. They were accompanied by the monk Lodovico da Bologna [30] - the Pope's legate in Georgia - and held talks in Hungary [31] , with Emperor Frederick III [32] , in Venice, where they were received with great respect and politeness [33] , then in Florence, Rome and with Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, considered as the possible leader of the European anti-Ottoman coalition [34] . But the result of this veritable European tour of the Eastern solons was nil. The fact is that the 1458-1461 actions of the Eastern coalition under the leadership of the Turkmen state of Uzun Hasan, which included Trapezunt, Armenia, Georgia and Sinope, led to anti-Ottoman campaigns in northern Anatolia in 1459 and 1460. This was known to Vlad the Impaler, which leads us to believe that he also held talks with the Eastern soldiers in 1460, when they were travelling on the Danube. Although there is no evidence for this, it is unlikely that the lord of Wallachia, who was preparing for war with the Turks, did not take advantage of the presence of the soldiers of the Eastern Coalition, which already existed and was acting against the Ottoman Empire, while at the same time heading for Central and Western Europe, where they hoped to build a similar anti-Ottoman coalition. In this way, Vlad the Impaler hoped to receive important aid from both East and West, and that his anti-Ottoman action, simultaneous with the other two coalitions, would be successful. Vlad Tepes also realised that dispersing the Ottoman forces on several fronts, where they could be engaged in heavy fighting, would have favoured his own action [35] . But this did not happen, as the coalition in the East was dealt a heavy blow by the sultan's conquest of the cities of Sinope and Trapezunt in 1461, and the anti-Ottoman coalition in the West was not formed until 1463, after the Turks had started the war with Venice. Vlad the Impaler's attack in the winter of 1461-1462 therefore took place without any outside support, at the very moment when the Turks were free to act militarily as they wished, which leads us to believe that he did not want the attack and therefore the outbreak of hostilities with the Ottoman Empire at the very moment when it was under no outside pressure. But as we shall see below, the lord of Wallachia had no choice, the Turks did not let him choose the moment of the attack, but, on the contrary, by their actions and intentions they provoked him just when they knew they could strike a devastating blow.

The negotiations with Matthias Corvinus and the Saxons of southern Transylvania, as well as the possible negotiations with the soldiers of the anti-Ottoman eastern coalition, naturally provoked the displeasure of the Porte, for whom continued non-payment of tribute was beginning to be considered a sign of insubordination. The vast majority of narrative sources agree that this change of attitude of the Porte towards Vlad Țepeș occurred in 1461, either during the campaign against Trapezunt or immediately afterwards [36] and do not suggest any previous disagreements regarding the non-payment of tribute. On learning of the agreement between Vlad Țepeș and Matia Corvin [37] , the sultan sent, for a start, a message to Wallachia in order to ask the prince to abandon the alliance with Hungary and the planned marriage [38] , but the expected results were not obtained. Vlad Țepeș accepted to pay the haraci, but refused to give children for the janissaries, a blood tribute that his country had never given [39] and refused to appear in person at the Porte [40] .

This time, the reasons given, among which the threat from Hungary was the most important, could no longer be believed by the Sultan [41], who decided to replace Vlad Țepeș from his reign. Mehmet II, however, sought to avoid a major campaign against Wallachia, whose chances of success were doubtful, and therefore tried to capture Vlad Țepeș by deception, but the trap set for the prince by Hamza bei and the Greek Catabolinos, near Giurgiu, ended in disaster, the two being captured and impaled [42] . Now appear in the Turkish chronicles the most serious accusations against Vlad Țepeș, accusations that justify the action and failure of Giurgiu, but also the sultanal campaign of 1462 [43] .

However, after the execution of the two Ottoman rulers, things had become very clear for Vlad Țepeș. There was no way back and the only plausible option, with some chance of success, remained war, a war that had to be fought with all determination and harshness, given the huge disproportion of forces in favour of the Turks.

In the political context created by the Congress of Mantua (26 September 1459-14 January 1460) [44] , by the coalition of states on the eastern borders of the Ottoman Empire [45] and by the Moreea uprising [46] , by the Venetian preparations for a decisive conflict with the Porte for predominance in the eastern Mediterranean [47] , the war waged by Vlad the Impaler in the winter of 1461-62 against the Ottoman Empire was undoubtedly the first major military action in Europe that preceded the great Turkish-Venetian war of 1463. Unfortunately for the lord of Wallachia, his action came at a time of calm on all the anti-Ottoman fronts, with the coalition of Eastern states in a period of ebb and the Western, Christian coalition not yet formed. In fact, the latter coalition was never formed and was only replaced by a system of alliances that revolved around Venice, but this from 1463 onwards. So, as we have already pointed out, Vlad the Impaler found himself alone against the Ottoman Empire, not because he wanted it out of an uncontrolled warlike impulse, but because he was forced, we repeat, by circumstances.

Vlad the Impaler was fully aware of this fact and that is why, in his famous letter of 11 February 1462 to the King of Hungary, Matthias Corvinus, after detailing the results of his expedition south of the Danube that winter, he emphasises his adherence to and identification with the Crusader ideal and consequently asks for the absolutely essential help he needed to face the huge Sultan expedition that was preparing against him. But let the Lord of Wallachia himself speak: "For we do not want to leave what we have started on the road, but to see it through to the end. For if the Almighty God will hear the prayers and desires of Christians and incline His ear with kindness to the prayers of His poor, and thus give us victory against the heathen, enemies of the cross of Christ, it will be the greatest honor and use and help of soul to thy great and holy crown and to all true Christendom.... And if, God forbid, we should come to an evil end and our country should perish, neither will your highness have any use or help in this matter, for it will be to the detriment of all Christendom" [48] .

It must be pointed out, however, that Vlad the Impaler, as a skilful politician and military commander, like Stephen the Great a little later, understood to fight against the Turks as a modern monarch, which in fact he was, a monarch who had the interests of his state at heart and not as a medieval crusader who threw himself headlong against the infidels. His adherence to the crusading ideal at this time can only be explained by a desire to gain support from other Christian powers, but he was aware that they too were far removed from the medieval crusading ideal and were fighting, if they decided to do so, only for their own interests. This explains the quite clear threat to the Hungary of Matthias Corvinus, who, in the event of the collapse of the Romanian Country or the installation on its throne of a prince allied to the Porte, would have found himself alone, face to face with the Ottoman Empire.

In launching his anti-Ottoman action in the winter of 1461 and 1462, because he had no other choice but to strike first and with all his might, Vlad the Impaler therefore counted on possible help from his ally, Matthias Corvinus, or even Pope Pius II [49] and on the fact that the main Ottoman forces were still dispersed in several directions (Sinope, Trapezunt, Moreea, etc.) [50] . Unfortunately, as we have already pointed out, his action was at odds both with that of the Turks' Asian enemies, defeated in 1461, when Sinope and Trapezunt were occupied by Mehmet II, and with that of Venice, which would not enter the fray until 1463, after the Turks had attacked first and taken Argos by surprise. As for the King of Hungary, despite the alliance he had with the voivode of Wallachia, his requests for help in his letter of 11 February 1462, the subsidies he had received from the papacy and the promise he had made to go in person against the Turks [51] , he had no intention whatsoever of confronting them [52] , for two main reasons: on the one hand he was still caught up in the conflict with Emperor Frederick III [53] , and on the other hand, from the beginning of his reign he was determined to direct his main efforts towards Central Europe and not against the Ottoman Empire [54] . The only concrete measure taken by Matthias Corvinus was to strengthen only the defence of Transylvania [55] .

In fact, the King of Hungary, from presumed ally, became Vlad the Impaler's enemy, whom he arrested on November 26, 1462, at a time when no one expected such a thing, tried to take credit for the summer victory against the Sultan and, in order to justify his action before Europe, which expected great feats of bravery from him in the anti-Ottoman struggle, he launched a veritable propaganda campaign to slander the brave prince of Wallachia, accused of treason, of collusion with the Turks and of abominable cruelties [56] . All this served, we repeat, as a pretext and justification before the Pope, Venice and the whole of Christian Europe for his own renunciation of the anti-Ottoman campaign he had promised to undertake.

So, if we were to formulate a few conclusions up to this point we have reached with our analysis, they might be as follows: Vlad Țepeș was forced to attack the Ottoman Empire in the winter of 1461 and 1462 due to the manifest hostility of the Sultan, who refused to accept on the throne of Wallachia a lord considered rebellious, the cessation of the payment of tribute in 1459 not having, in our opinion, the significance of an open break with the Porte. The voivode of Wallachia did not receive any concrete help from anyone, because the enemies of the Porte and his potential allies had either been defeated or had not yet entered the battle [57], his main ally, Matthias Corvinus not only did not help him but, probably reaching an agreement with the Porte regarding Wallachia in order to have peace on its southern borders, arrested him and threw him in prison where he stayed for almost 13 years. Because of this, the great victory achieved by Vlad Țepeș in 1462, when the Sultan was forced to retreat south of the Danube without having achieved any of his original objectives, could not be exploited in any way by the European powers, especially Venice, which in a year's time would go to war with the Turks, a decisive war for the balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean. It should also be borne in mind that the expulsion of Vlad Țepeș from his reign, just after his victory, can also be explained by the attitude of part of the nobility, of the political class, which was willing to fight only in moments of great hardship that threatened its own existence. When these times passed, it preferred to reach compromise solutions with the great power south of the Danube [58] . This was also the case with the accession of Radu the Handsome. Nevertheless, Vlad Țepeș's victory over the Sultan was of particular importance, as it managed to save the existence of the Romanian state and made it possible to reach a compromise with the Porte, which would have been impossible in the event of defeat. Basically, Vlad Țepeș saved his country from being turned into a pashas.

However, it is also interesting to note how Venice, the main Christian power in the Mediterranean at that time interested in the anti-Ottoman struggle, followed the events of the Lower Danube [59], how it knowingly became the mouthpiece of Matthias Corvinus, even though it was well aware of the political reality in the area. In 1459, in the year of Vlad Țepeș's supposed open break with the Porte through non-payment of tribute, Venice was not very interested in the events in this area, which, moreover, did not herald anything special. This may be one of the explanations for the permanent obstacles to Pius II's crusading plans, as set out at the Congress of Mantua. Thus, in exchange for her participation in a possible anti-Ottoman coalition, Venice demanded 8,000 men to equip her fleet, payment of all expenses incurred for war preparations, and the organisation of an army of 50,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers to go to the borders of Hungary [60] , conditions impossible to achieve. Moreover, after the peace concluded on 23 April 1454 [61] by Bartolomeo Marcello with the Sultan, the Republic of the Lagoons did its utmost to preserve the status quo in relations with the Turks, to reduce any of their sensitivities, to avoid at all costs the outbreak of a new war with the Ottoman Empire. Such a war was regarded as inevitable, sooner or later, by Venice, which had begun to realise that the Turks were gradually becoming a formidable maritime power,[62] but it should not be started before the Republic was fully prepared. Of course, the Republic was never fully ready, so after a nine-year peace, the war would be triggered, somewhat surprisingly for the Venetians, by the Turks.

Until then, however, the Venetians sought to spare the Sultan as much as possible and at the same time avoid papal invitations to join the preparations for an anti-Ottoman crusade. Thus, on 2 December 1456, in the instructions that the Senate sent to Lorenzo Vitturi, the Bailiff of Constantinople, he was asked to tell the Sultan that he had no reason to fear Venice [63] , and on 3 September 1459, in the instructions given to the new Bailiff Domenico Balbi, he was asked to resolve the conflicts and commercial disputes that had arisen in the meantime with great diplomacy, without reaching a rupture [64] .

On the other hand, the instructions that the Senate gave on 21 June 1458 to Niccolň Sagondino, envoy to Pope Calixtus III (1455-1458), are particularly significant. He was to show the Holy Father that the accusations levelled in Rome against Venice were intolerable, since Venice had always done its duty to Christianity. In this regard, Sagondino was to insist on the victory of Gallipoli in 1416, where a Turkish fleet was completely crushed, he was to show that in 1423 Salonium was occupied and held for seven years with great effort by the Venetians, that in 1444-1445 Venice armed galleys that fought all winter, while Pope Eugenius IV did not pay what he had promised. And all this while the other Christian powers did not respond to Venice's requests for help. Rather than listen to its accusers, the pope should consider the fact that the Turks are closely surrounding the Venetian possessions and that Venice's situation is therefore totally different from that of the other Christian states. For this reason, Venice cannot think of attacking the Turks in the given circumstances, because it would be premature, but it defends the island of Negroponte and maintains 12 galleys in the Aegean Sea to guard the Straits, and no Christian state can boast of comparable efforts [65] . It must be admitted that these instructions, intended to reach the ears of the pope, faithfully respected both the historical truth and the present situation, ruthlessly debunking all the accusations that could be levelled at Venice at that time. Due to the death of Calixtus III, a letter, almost identical, was also sent to the new Pope Pius II, on 30 October 1458[66] .

About a year later, on 11 October 1459, the Venetian Senate gave a very interesting reply to the delegates of Pope Pius II, who insisted that Venice participate in the preparations for the crusade. It was thus pointed out that the battle plans proposed by the pope were grandiose, but it was doubtful that the Italian states would find the necessary resources to maintain a sufficient army capable of defeating the Turks, who were very powerful [67] . The adversary should not be underestimated, especially now that Mehmet II is much more powerful than Murad II because he rules Constantinople. It is recalled that Murad defeated at Varna and the Christian powers hardly fought back, and that a long war is now to be foreseen, which will need financing without hesitation. Thus, thorough preparations must first be made and then war can be launched. As far as it was concerned, Venice was making such preparations [68] , but wondered what the other Christian powers were doing [69] . On 10 November 1459, about a month later, the Senate addressed a new letter to the Pope. In it the Venetians were more than surprised at the extent of the preparations for the crusade. They asked the pope how he could believe that the 240,000 ducats needed to arm 50 galleys could be raised quickly, and pointed out that it would be preferable to draw up plans for a crusade that were really feasible and not mere utopias [70] .

From all that has been said so far it is clear that in the years following 1454 the Venetians pursued a policy of obvious undermining of the Ottoman Empire and rejection of the Crusade, but we cannot but agree that, to a large extent, the arguments they used were fair and hard to refute. Everyone was aware, despite the pope's efforts, of the disappearance of the crusading ideal and the ideal of the unity of the Christian world, and no one could accuse the Venetians, with real grounds, of not wanting to fight the Turks. It would have meant asking them to commit a real act of suicide, which neither they nor the other Christian states were willing to do.

It seems that it was not until 1460, when the Turks attacked Moreea again and reached the borders of the Venetian possessions here, that Seria really began to worry about the intentions of the Ottoman Empire towards it[71] . So in 1461, the year in which we consider that the rupture between Vlad Țepeș and the Turks really took place, the situation of Venice was completely different, which explains its increased interest in the events of the Lower Danube.

In April 1460, after having noticed suspicious preparations by the Turks, the Senate ordered the captain of the Gulf, Antonio Loredan, to leave with the greatest haste for Negroponte [72] . On 20 May, the military preparations of the Turks became so worrying that Venice was forced to take several preventive measures: it requested the preparation of 300 crossbowmen in Crete, so that they could be sent to Negroponte if necessary, it decided to send supplies of wheat to Modon and Negroponte, and to arm three new galleys [73] . On the same day, the new captain of the Gulf, Giacomo Barbarigo, was ordered to leave immediately for Negroponte and to make short calls at Corfu, Modon and Nauplia [74] . On 16 June, instructions to Lorenzo Moro, who had replaced Barbarigo as captain of the Gulf, required him to first of all put Coron, Modon and Nafplio in a state of defence, and if he found out that the Sultan was heading for Albania or Negroponte to take the necessary measures [75] . Finally, on 1 August, the information received by Lorenzo Moro and the castellan of Modon and Coron proved very clearly that the Sultan intended to establish his authority over the whole of Morea and that he was the enemy of Venice. The Turks had reached the borders of the Venetian territories in the Peloponnese and, in order to better probe the Sultan's intentions, the Senate decided on 9 August to send an extraordinary ambassador to the Porte in the person of Niccolň da Canale [76] .

In 1461 the tension generated by the Ottoman military preparations persisted in Venice. On 28 April, the Senate sent its instructions to Vittore Capello, supreme commander of the Venetian fleet (Captain of the Sea), asking him to visit all Venetian ports in Romania, to watch the movements of the Ottoman fleet, but with great discretion, and not to attack Turkish ships leaving the Dardanelles. Such actions would be dangerous at a time when Venice was holding talks with the Sultan [77] . On 21 July the same Vittore Capello was asked to disarm part of the fleet, the Ottoman danger being less pressing after the Sultan left for the Black Sea [78] . But Venetian fears were far from being allayed. In the autumn, on 18 October, the Senate came to the conclusion that, owing to the general circumstances and the dangers threatening the territories of Romania, it was more than ever essential that men of merit should be elected as governors, and that they should be given all the necessary advantages [79] . Only two days later, on 20 October, although it had learned that the Turkish fleet had disarmed, Venice could not be reassured about the Sultan's intentions, and so Capello was asked to keep watch, with the galleys that remained at his disposal, over the waters of the Aegean archipelago [80] . On 9 December, the Senate also decided that the fortifications of Negroponte should be strengthened, that arms should be sent to them and that a detailed defence plan should be drawn up [81]. At the end of the same year, Venice also alerted the King of Hungary, Matthias Corvinus, to the imminence of war with the Turks [82] and also tried to bring about a reconciliation between him and Emperor Frederick III [83], but without success.

However, on 4 March 1462, the Venetian envoy to Buda, Pietro Tomasso (Petrus de Thomassis), announced to the Senate that he had been summoned by the king, who gave him to read some letters he had received from one of his soldiers to Vlad the Impaler, informing him of the damage he had caused to the Turks, of the multitude of those killed whom he had seen "according to the number of heads depicted, apart from those who were burned in those places". From this letter, which in fact refers to the one sent by Vlad Țepeș on 11 February, it appears that Matia Corvin used the results of the victorious expedition of the prince of Wallachia - whom he considered his vassal - in order to obtain funds from Italy, the Venetian envoy asking for "denarij per sovvene" [84] . It is also noted that the echo of Vlad Țepeș's deeds of bravery was quickly received in Venice, which, almost immediately, on 20 March, made them known in Rome [85] .

Having reached this point in our investigation, we feel that we must highlight a particularly important aspect that we will find again in Venice's attitude towards Vlad Țepeș until the end. Namely, it is the fact that, although it knew very well who was the author of the victory against the Turks in the winter of 1461-1462, i.e. Vlad Țepeș [86] , Senioria accepted all the propaganda of Matia Corvin and acted to help him and not the brave prince of the Romanian Country. Thus, on 20 March 1462, the Venetian Senate wrote to the Pope, as we have shown above, explaining the critical situation of Hungary and not of the Romanian Country, as if Hungary had entered into battle with the Turks and not the Romanian Country. Moreover, the Senate proposed to the Pope to send monthly the

10-12,000 florins to Hungary for the maintenance of 400 horsemen. This project was also presented to Matthias Corvinus on 29 March [87] . Pope Pius II knew as well as the Venetians who was the real winner over the Turks. This was because he had been informed by the Venetians themselves, but also from a letter of the Cardinal of Mantua, dated April 1462, who informed him of the following: ,,Adi 29 di Marzo venne nuova come li Valacchi chi hevevano dato una rotta al Turco nelle paesi della Va(la)cchia, e morti di loro piu di vintimilla soldati..." [88] . But for the pope, as for the Venetians, the Catholic king of Hungary had to be the hero of the anti-Ottoman struggle, and therefore he had to be helped.

Venice, although it probably wished to do so, avoided entering into direct contact with Vlad Țepeș, thus seeking to play down the sensitivities of Matthias Corvinus [89] , who claimed to be his suzerain and thought himself entitled to deal on behalf of the man he considered his vassal. Therefore, all Venetian information comes from the Hungarian court, some from Constantinople as well, but it proves that the events of the Lower Danube were followed with great attention in the "fortress of the lagoons", the political factors here seeking to find out their true significance and extent.

A second letter, known to us, sent by Pietro Tomasso to Venice, is dated 27 May 1462. In it, the ambassador describes to his superiors the situation on the Lower Danube as it was on the eve of the outbreak of the great Sultan campaign. First of all, he talks about Mehmet II's huge army, which, according to some rumours, he considers to number 200 000 men, including 20 000 janissaries, and points out that there could be three areas of attack: Wallachia, Transylvania and Belgrade, the first two being the most likely. Then a river fleet of 300 ships is mentioned, which the Sultan introduced on the Danube to help him cross the river. This is followed by information about Vlad the Impaler, who is said to have sent all his women and children to the mountains while he and his army guarded the Danube. It is also said that everyone at the court in Buda was surprised that Vlad Țepeș had not sent for help, and that the king was determined to go and fight the Turks [90] . At the end of the letter the ambassador makes some considerations about the future course of events as he envisaged them, some of which will be refuted, but others confirmed. Thus, he believes that either Vlad Țepeș will be easily defeated by the huge Ottoman army, which will not happen, after which the Hungarian kingdom will be defeated just as easily, which again will not happen precisely because Vlad Țepeș will not let himself be crushed, or King Matthias will reach a shameful agreement for the whole of Christendom [91] , which will indeed happen, despite the splendid victory of the Romanian lord [92] . From this letter it can be seen that the Venetian ambassador in Buda had become quite familiar with Hungary's military capability and her king's "desire" to confront the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, he did not doubt that Vlad the Impaler was determined to make every sacrifice to defend his country but, not knowing the military situation of the Romanian Country, he believed that a possible success would have been impossible in the face of the Ottoman onslaught.

More than two weeks later, on 14 June, the same Pietro Tomasso wrote again to the Doge, showing him that the Turks led by a Pasha, probably Mahmud Pasha, had crossed the Danube with 60 000 men, including 25 000 janissaries. In fact, this is the closest figure to the truth for the entire Ottoman army led by Mehmet II himself [93]. The Venetian ambassador went on to say that the prince of Transylvania was preparing for battle, and that Matthias Corvinus had told him that the Sultan was in camp and would probably attack Belgrade. He also indicated that the king had ordered the general assembly of the army at Seghedin, from where it could move either to Belgrade or to Transylvania and Wallachia, depending on Mehmet II's intentions. It can be seen that with this news Matthias Corvinus was trying to create confusion in Venice and probably in Rome about the Sultan's intentions. He spoke of the possibility of attacking Belgrade at a time when it was very clear that the Sultan intended to attack with all the forces at his disposal, precisely because he did not intend to support Vlad Tepes and openly confront the Ottomans. At the same time, however, he asked Venice to call on the Pope and other Christian princes to send him aid, showing that his treasury was empty. The ambassador said that Vlad Țepeș, unable to stop the Turks at the Danube, had retreated to the mountains and predicted his complete defeat, feared by the court of Buda, which could have led to the loss of Transylvania [94] .

Some of this information, however, was contradicted by other information from different sources. Thus, regarding the fact that Vlad Țepeș had not asked for help from the King of Hungary, information transmitted by Tomasso on 27 May [95] , another letter, that of Ladislau de Vesen, also addressed to the Doge, indicated that the lord of the Romanian Country "... every day asks to be helped, because he will not be able to support such a strong attack alone" [96] . Even Pietro Tomasso, in his letter of 15 June, indicated that the Sultan had already entered Wallachia, but, under the influence of the court of Buda, he maintained his opinion that from here he could move against Belgrade and continued to express doubts about Vlad Țepeș's ability to resist [97] . Of course, all this information, although some of it was contradictory and could leave room for justified suspicions, turned Venice's attention primarily on Matthias Corvinus and less on Vlad Tepes, with whom it avoided, as we have already shown, to enter into direct links.

But the reality was different, and the one who knew it best was the King of Hungary himself. Thus, after having tried to demonstrate to Venice that Vlad Țepeș was incapable of resisting the Turks and after having received subsidies from the latter for the anti-Ottoman struggle, [98] Matthias Corvinus tried to make the most of the splendid victory of the Romanian prince, to which he had contributed nothing. Immediately after learning of the victory and the Sultan's retreat, he sent a message to Venice announcing the crushing of the Sultan by "Hungarians and Romanians", the echo of which was recorded by the Milanese ambassador in the lagoon city, A. Guidobonus, on 30 July 1462 [99] .

But in spite of these attempts, which in today's terms we might call intoxication and misinformation, Venice, whose diplomacy was very skilful in such matters, could not be misled. It gathered its information not only from Buda, but also from elsewhere, and was thus able to form a picture very close to the real course of events in the Lower Danube. Particularly significant in this respect is the letter of the Constantinopolitan bailiff Domenico Balbi, who, on 28 July 1462, gave an almost complete and truthful picture of Mehmet II's campaign in Wallachia. He showed that, once north of the Danube, the Sultan found the country empty of men and provisions, all retreating to fortified places in the mountains. He then tells of the harassing war waged by Vlad Țepeș, of the night attack against the Sultan's camp, of the great losses suffered by the Turks, which finally forced them to retreat, Mehmet II being already at Adrianopol on 11 July. It is also mentioned that the Sultan left his brother, none other than Radu the Handsome, with some Ottoman troops near Wallachia, to try to overthrow the prince with the help of possible internal complicity: ,,... lasso al fradello de Dracuglia cum alcume bandieri dei Turchii per tentar li animi de Valachi de quanto volesserro lassar al Dracuglia convenir de quest altro" [100] thus, an accurate picture of the 1462 campaign and Vlad the Impaler's victory, but not a word about the so often mentioned help of Matthias Corvinus, which of course made the Senate, the Doge and the other ruling factors of the Republic realize also the real position of the Hungarian king.

True information about what happened in Wallachia in 1462 reached Venice through other channels, probably letters from its representatives in the Balkans and the Aegean islands, echoed in several chronicles of the time, which also reveal the opinion of Venetian public opinion, i.e. the informed circles of the Republic, about the events of that year at the Lower Danube. Thus, an anonymous Italian chronicle, also circulating in Venice, which goes on to narrate events up to 1481, records, under the year 1462, that '... the Turks who had gone against Dracula in Wallachia were beaten and chased away" [101] , the chronicle of Domenico Malipiero also states that the lord of the Romagna region met the Turks with a strong army and defeated them with mighty will [102] , and the Venetian Annals (1433-1477) of Stefano Magno wrote that in 1462 Mehmet II, "emperor of the Turks and Greeks", sent ,,... a strong army into Wallachia; but the Wallachians rising against it were defeated..." [103] . We note, therefore, that in all these sources, which refer to the great confrontation that took place in Wallachia in 1462, there is no mention of any contribution by Matthias Corvinus, whose claims, brought to the knowledge of the Republic by the July solia, are appreciated at their fair value, i.e. at their rhetorical-propagandistic value, without any real support.

The suspicions that Venice had about the intentions of Matthias Corvinus also result from the fact that when he left Buda on his so-called campaign to help Vlad the Impaler, arriving only at the beginning of November 1462 in Brasov, he was accompanied by the Venetian ambassador Pietro Tomasso. His mission was to inform the Senate about the evolution of the conflict and other important events [104] . Unfortunately, the only information that the ambassador sent and of which we are aware was that of 26 November, concerning the arrest of Vlad Țepeș, after some time the leadership of the Republic confirmed the receipt of this letter, as well as that of the King of Hungary about the "case" Vlad Țepeș [105] .

We suspect that the Venetian authorities, usually very well informed about events, especially if they were of direct interest to them, had found out by the end of the year the truth about the relations between Matthias Corvinus, Vlad the Impaler and the Turks, because as early as 9 November it was known in Vienna that the King of Hungary had concluded a secret treaty with the Sultan [106] . As relations between Frederick III and Matthias Corvinus were tense, we do not see what obstacle could have prevented Venetian diplomacy from finding out everything that might interest it about this treaty. But, although it knew the truth, Venice continued to undermine Matthias Corvinus in the hope that he would eventually decide to attack the Turks. This was at a time when Venetian-Ottoman relations were becoming increasingly tense, with Venice's preparations for war intensifying especially after the appointment of a new Captain General of the Sea (supreme commander of the Venetian fleet) in December 1462, an appointment that did not become effective until 31 January the following year, with the election of Alvise Loredan to the post [107] .

Thus, on 15 January 1463, the Venetian Senate confirmed to the Hungarian King the receipt of letters informing him of "... the enmity case of the former Montenegrin lord, who tried to commit such a great crime against Your Majesty and the kingdom" [108] . Matthias was also praised for having taken some timely defensive measures [109] . This was, however, we repeat, a diplomatic language that Venice used against Hungary only because it needed to ally itself with it at a time when a major confrontation with the Ottoman Empire seemed unavoidable and Vlad Tepes had lost his reign. In fact, despite the letters and 'proofs' of treason sent by Matthias Corvinus, the Venetian Senate could not be convinced of Vlad the Impaler's guilt.

Five months after his arrest, on 18 April 1463, it asked the new ambassador in Buda, Giovanni Aymo, to discover the truth about Vlad Țepeș, to find out about the relations between the King of Hungary and the new ruler of the Romanian Country and to find out whether a peace had been or could be made between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, in which case it had to do everything possible to prevent it [110] . Two important things emerge from these instructions: on the one hand, Venice's distrust of the political and military intentions of Matthias Corvinus, and on the other, its imperative need to establish an alliance with Hungary in the face of the growing Ottoman threat. The information she possessed about the secret treaty between Matthias Corvinus and the Sultan, probably obtained through Vienna but also through her diplomatic agents in the Balkans, she wanted to have confirmed or refuted by investigations on the spot and, if possible, to turn the situation in her favour. For this reason she was willing to accept the explanations and arguments of the Hungarian king, the veracity of which she doubted, but she did not derive much benefit from the hoped-for alliance with him, since Matthias had his sights set on Central Europe, preferring to maintain a situation of military balance and territorial-political status quo on the borders with the Ottoman Empire [111] . On the Lower Danube, the main de facto allies of Venice in the long war with the Ottoman Porte between 1463 and 1479 were the Romanians and not the King of Hungary. The Romanians led by Vlad Tepes defeated the Sultan in 1462, they too, but led by Stephen the Great, would achieve the brilliant victory of Vaslui in January 1475, a victory which for a time eliminated Ottoman pressure on the Venetian possessions on the Balkan coast of the Adriatic, and in 1476 a new Sultan expedition would crush their fierce resistance. In this period, as in others of the Middle Ages, the main factor of resistance to Ottoman pressure on Central Europe was the Romanian countries and much less the feudal Hungarian kingdom. It is true that the Hungarian royalty tried to take credit for all the major victories achieved against the Turks on the Lower Danube, but this could not hide the undeniable truth of the facts. For the ruling politicians in Vienna, Venice, Rome and others, Matthias Corvinus' behaviour in 1462 was very clear, his treachery was obvious, but the hopes, unrealised, moreover, that he would change his attitude and fight the Turks led them, like the Venetians, to give him credit, undeservedly, for it.

How, however, can this attitude be explained? We believe that two factors played a primary role, both for Venice and for the papacy. The first is Hungary's status as a great power, recognised throughout Europe. So, in comparison with the Romanian countries, which had a much lower political and military potential, Hungary was preferable, from which they expected not only a defensive confrontation policy towards the Turks, but also important offensive actions against them. For this reason the papacy intervened energetically to conclude a peace treaty between Matthias Corvinus and Frederick III [112] , after which it played an essential role in the conclusion of a treaty of alliance between Venice and Matthias Corvinus, a treaty concluded on 12 September 1463 [113] . But it seems that this alliance with Hungary was already too late. By that time Hungarian foreign policy had already changed direction and Hungary was no longer aggressive towards the Turks [114] . After Matthias Corvinus had secured his hold on the Jajce region of Bosnia and after the failure of the papal crusade project in 1464, he abandoned the anti-Ottoman struggle for a long time and, at the urging of Pope Paul II (1464-1471), turned his forces against George Podiebrad (1458-1471), king of Bohemia, his former ally and father-in-law, but who had meanwhile become a heretic and enemy [115] . The situation could not be prevented or changed by the agreement signed on 19 October 1463 between Pope Pius II, Venice and Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy [116], which provided for an anti-Ottoman alliance for three years.

Secondly, it is the fact that Matthias Corvinus was the Catholic king of a Catholic state, Hungary. For the Pope it was essential that the anti-Ottoman crusade be led by Catholics and that it be carried out with the participation, first and foremost and on a large scale, of Catholic forces, Catholic states. For this reason, one of the constants of papal anti-Ottoman crusade policy was to seek participants within Catholic Europe. Once they had offered their services or refused to take part in the crusade, papal diplomacy turned its attention to the Orthodox world and even to the Asian world, from where formidable enemies of the Ottoman Porte could emerge. This is why Venice, which desperately needed the help of the papacy, did not dare to bypass the Catholic Matthias Corvinus and enter into direct contact with Vlad Tepes. For Pope Pius II, all the victories of Vlad the Impaler were, in fact, victories of this Catholic king of Hungary. Nor could the pope have conceived of an anti-Ottoman crusade being started by an Orthodox prince, and of his placing himself at its head. That is why there was not even the question of helping, even symbolically, the brave prince of the Romanian Country. All eyes were on Matthias Corvinus, the only leader capable, in the Pope's view, of leading the anti-Ottoman forces. Significant in this respect is the firm rejection by Pius II in 1462 of a project for an anti-Ottoman crusade, which had been initiated by the Bohemian king George Podiebrad, suspected of heresy. The latter, through a Frenchman from Dauphiné, Antonio Marini, who had arrived in unclear surroundings at his court, proposed an anti-Ottoman alliance to Venice, Burgundy and France. But Podiebrad wanted to bypass the pope, to leave him out of the alliance, which, as Venice pointed out to him, was an impossibility [117] . And indeed, absolutely nothing came of this project.

We believe that these are the two main reasons why the Italian powers, in particular Venice and the papacy, avoided engaging in direct relations with Vlad Țepeș, leaving him to the good pleasure of Matia Corvinus, who threw him into prison for more than 13 years without anyone holding him to account.

Things would become very clear towards the end of Matthias Corvinus' reign, however, when he repeated his behaviour, in a similar situation, towards Stephen the Great, Lord of Moldavia. Although he had an alliance with the latter, which provided for mutual aid in the event of Ottoman attacks, Matthias Corvinus did not hesitate to conclude a treaty with the new sultan, Baiazid II (1481-1512), in 1483. Thus, while the Turks attacked and captured by surprise the two key cities of southern Moldavia, Chilia and the White Fortress, he launched a major campaign against Frederick III in the summer of 1484, which resulted in the occupation of Vienna the following year, where he remained until his surprising death in 1490 [118] . The "champion of Christianity", the "defender of Europe" thus ended his days in "glory" in Vienna, having conquered, in hard and bloody battles, almost all the hereditary possessions of the Habsburgs, and not in the anti-Ottoman struggle as he had promised throughout his reign.

In fact, in our view, Hungary was not and could not be that "wall of defence" of Europe against the increasingly insistent Ottoman assaults, for two main reasons. The first, less important, is that Matthias Corvinus, its last great king, deliberately turned his efforts to a policy of expansion in Central Europe, the exact opposite of what his father, the great Iancu of Hunedoara, had done, a policy which necessarily involved the maintenance of the Ottoman Porte. The second and most important reason is that the overall development of Hungarian society in the 15th century and at the beginning of the following century led to an intensification of feudal anarchy, through the increase in the power of the great magnates and a corresponding weakening of state structures and the strength of the state, which explains why a single battle (Mohács, 1526) was enough for this state to disappear from the political map of Europe. The same was not true of the Romanian countries, which have experienced uninterrupted state continuity and have recorded in history numerous glorious feats of anti-totalitarian struggle.

At the end of these brief considerations, we believe that a few conclusions are in order regarding Vlad Țepeș in the context of the anti-Ottoman struggle. First of all, it is noted that there was no direct link between him and Venice, this being impossible due to the claims of suzerainty manifested by Matthias Corvinus towards Wallachia, theoretical claims, but which Venice, for the reasons indicated above, did not want to contest. Secondly, we can say that Venice, in spite of Matia Corvin's disinformation action, knew, even with very significant details, the heroic struggle of Vlad Țepeș, as well as the less than chivalrous behaviour of the Hungarian king, in contradiction with the medieval obligations of a suzerain towards his vassal, as Matia Corvin claimed to be towards Vlad Țepeș. But, thirdly, Venice preferred to turn a blind eye to the evidence, hoping to obtain the effective collaboration of Matthias Corvinus in the anti-Ottoman struggle. The result was that it passively witnessed the downfall of a sure ally, Vlad the Impaler, and in return obtained only a very inadequate amount of help from Hungary, which at the time did not have, even if it wanted to, the capacity to wage a major offensive war against the Ottoman Empire.

Vlad the Impaler tried to break out of the system of Hungarian-Ottoman co-occupation established over the Romanian Country in 1451-1452, but without adequate external support he was unable to do so. His action showed that this system could not be removed, that, overcoming mutual hostility, the two great powers intended to keep it in place, which would happen until the disappearance of Hungary in 1526. At the same time, however, his action also brought to light a particularly important fact, namely that the balance of power in this system was increasingly tilted in favour of the Ottoman Empire. This also explains Stephen the Great's repeated failures to bring Wallachia into his sphere of influence and to oppose the Turks, the victim of which was Vlad the Great himself in 1476. However, his struggle was not in vain. It showed the Turks that Wallachia could be defeated but not destroyed.

___________

Sources:

[1] Ioan Bogdan, Vlad Țepeș and the German and Russian narrations about him, Bucharest, 1896, p. 11; Ștefan Andreescu, Vlad Țepeș (Dracula) between legend and historical truth, Bucharest, 1976, p. 59; Manole Neagoe, Vlad Țepeș, heroic figure of the Romanian people, Bucharest, 1977, pp. 21-22.

[2] Nicolae Stoicescu, Vlad Țepeș, Bucharest, 1976, pp. 33-37; Radu Ștefan Ciobanu, Pe urmele lui Vlad Țepeș, Bucharest, 1979, p. 95.

[3] History of Romania, vol. II, Bucharest, 1962, pp. 465-466.

[4] Hurmuzaki, Documents concerning the history of Romanians, vol. XV, 1, Bucharest, 1911, p. 45, doc. LXXIX.

[5] Ibidem, pp. 45-46, doc. LXXX.

[6] Olgierd Górka, Cronica epocei lui Ștefan cel Mare, 1457-1499, Bucharest, 1937, p. 110; see also Ion Const. Chițimia, Cronica di Ștefan cel Mare (Schedel's German version), Bucharest, 1942; Slav-Romance chronicles of the 16th century, Bucharest, 1942. XV-XVI published by Ioan Bogdan, revised and completed edition by P. P. Panaitescu, Bucharest, 1959, pp. 28, 49, 61 and 178; Grigore Ureche, Letopisețul Țării Moldovei, edition P. P. Panaitescu, 2nd edition, Bucharest, 1958, p. 90.

[7] See in this regard the statements of Critobul of Imbros, From the reign of Mohammed II. Anii 1451-1467, edited by Vasile Grecu, Bucharest, 1962, p. 290; Laonic Chalcocondil, Expuneri istorice, edited by Vasile Grecu, Bucharest, 1958, p. 283; Tursun-bei, ,,Tarih-i Ebu-l Fath-i Sultan Mehmed han" (History of Sultan Mehmed-han, the conquering father), in Cronici turcești privind țările române. Extracts, vol. I, Sec. XV-mid sec. XVII, ed. Mihail Guboglu and Mustafa Ali Mehmet, Bucharest, 1966, pp. 67-68; Șemseddin Ahmed bin Suleiman Kemal-pașa-zade, ,,Tevarih-i al-i Osman" (Histories of the Ottoman Dynasty) in ibidem, p. 198; Constantin Mihailovici de Ostrovița's account in Foreign Travellers about Romanian Countries, vol. I, Bucharest, 1968, p. 126.

[8] The hostile attitude of Matthias Corvinus towards Vlad Țepeș is confirmed by the order he issued from Buda on 10 April 1459, forbidding the Brașovs to sell arms in Wallachia (Hurmuzaki, Documents, XV, p. 52, doc. XC).

[9] See Chapter I of this work, note 124.

[10] In support of this assertion, we believe that the historian Șerban Papacostea comes to the conclusion he reaches after a meticulous research of the causes that generated the conflict between Vlad Țepeș and the Saxons of southern Transylvania. Here is what he says: "The fierce confrontation between Vlad Țepeș and the cities of Brașov and Sibiu was therefore not a commercial war with political manifestations, but a political conflict with commercial excesses" (Șerban Papacostea, ,,Începuturile politica commerciale a Țării Românești și Moldovei (secolele XIV-XVI). Road and State", in Studies and Materials of Medieval History, X, Bucharest, 1983, p. 30.

[11] This is an anonymous history up to 1500, La progenia della cassa de' Octomani, apud Nicolae Iorga, Acte și fragmente cu privire la istoria românilor, vol. III, București, 1897, p. 13 and Donado da Lezze's chronicle, Historia turchesca (1300-1514), ed. I. Ursu, Bucharest, 1909, pp. 24-25, which

indicates the year 1458 for Mahmud Pasha's expedition against Vlad Tepes, information considered true by N. Iorga in Istoria Românilor, vol. IV, Bucharest, 1937, pp. 130-131.

[12] The chronological error of the two Italian sources, which place the events of the beginning of the 1462 campaign four years earlier, is demonstrated with solid arguments by Ștefan Andreescu, op. cit., pp. 91-92 and idem, ,,Războiul cu turcii din 1462", in Revista de istorie, tom 29, nr. 11, 1976, pp. 1673-1674. See also Const. A. Stoide, ,,Vlad the Impaler's battles with the Turks (1461-1462)", in Anuarul Institutulului de istorie e arheologie "A. D. Xenopol", XV, 1978, pp. 16-17. We share this opinion. The confusion in the two Italian sources may also derive from the fact that in early October 1458 Hungarian troops led by Mihail Szilagyi defeated an Ottoman army commanded by Mahmud Pasha near Belgrade (I. A. Fessler, E. Klein, Geschichte von Ungarn, III, Leipzig, 1876, p. 16; N. Iorga, Geschichte des osmanische Reiches nach den Quellen dargestellt, vol. II, Gotha, 1909, pp. 107-108; C. Jireček, Geschichte des Serben, II, 1, Gotha, 1918, p. 213; Franz Babinger, Mahomet II le Conquêrant et son temps. 1432-1481. La grande peur du monde au tournant de l'histoire, Paris, 1954, pp. 189-190).

[13] For the haraciul of Wallachia during Vlad Țepeș's reign see M. Berza, ,,Haraciul Moldovei și Țării Românești în sec. XV-XIX", in Studii și materiale de istorie medie, II, București, 1957, pp. 28-29.

[14] Istoria României, II, p. 470; N. Stoicescu, op. cit., p. 86; idem, ,,La victoire de Vlad l'Empaleur sur les Turcs (1462)", in Revue Roumaine d'Histoire, XV, no. 3, 1976, p. 377; Șt. Andreescu, Vlad Țepeș (Dracula)..., p. 99; R. Șt. Ciobanu, op. cit., pp. 170-171; Emil Stoian, Vlad Țepeș. Myth and historical reality, Bucharest, 1989, p. 79; Constantin Rezachevici, ,,Vlad Țepeș - chronology, bibliography", in Revista de istorie, tom 29, nr. 11, 1976, p. 1748; idem, ,,Vlad Țepeș - Chronology and historical Bibliography", in vol. Dracula. Essays on the Life and Times of Vlad Țepeș. Edited by Kurt W. Treptow, Columbia University Press, New York, 1991, p. 257; Kurt W. Treptow, Aspects of the Campaign of 1462, in ibid, pp. 123-124. Matei Cazacu considers that Vlad Țepeș stopped paying tribute to the Turks in 1460 and links this decision to the work of the Congress of Mantua in 1459 (Matei Cazacu, L'histoire du prince Dracula en Europe Centrale et Orientale (XVe siècle), Geneve, 1988, p. 📷.

[15] In this year Mehmet II undertook an important campaign in Moreea, succeeding in conquering a third of the Peninsula, with the cities of Corinth, Patras, Vostitza, Kalavryta. The two despots of Morea, Thomas and Demetrios, are obliged to pay an annual tribute of 3,000 ducats (Denis A. Zakythinos, Le Despotat grec du Morée. Historie politique, London, 1975, pp. 256-260).

[16] F. Babinger, op. cit., pp. 199-201.

[17] Ibidem, pp. 210-215; D. A. Zakythinos, op. cit., pp. 267-274. On 1 August 1460, the Captain of the Gulf, the title borne by the commander of the Venetian fleet in the Adriatic, Lorenzo Moro, as well as the castellan of Modon and Coron, received very clear information that the Sultan intended to establish his authority over the whole of Morea, that he was the enemy of Venice and that he had already reached the borders of the Venetian territories in the Peninsula (F. Thiriet, Régestes des délibération du senat de Venise concernant la Romanie, tome III, 1431-1463, Paris, The Hague, 1961, pp. 233-234, no. 3118).

[18] F. Babinger, op. cit., pp. 228-238; Ș. Papacostea, ,,Relațiile internazionali în răsăritul și sud-estul Europei în secolelele XIV-XV", in Revista de istorie, vol. 34, no. 5, 1981, pp. 916-917; Tahsin Gemil, Românii și otomanii în secolelele XIV-XVI, București, 1991, p. 140.

19] For this conflict see Hurmuzaki, Documents, XV, 1, pp. 50-51, doc. LXXXIX; I. Bogdan, Documente privitoare la relațiile Țării Românești cu Brașovul și cu Țara Ungurească în sec. XV-XVI, vol. I, 1413-1508,

Bucharest, 1905, pp. 101-103; C. C. Giurescu, Istoria românilor, vol. II, 1, 3rd ed., Bucharest, 1940, pp. 43-49; Istoria României, II, pp. 468-469; N. Stoicescu, Vlad Țepeș, pp. 70-73; Șt. Andreescu, Vlad Țepeș (Dracula)..., pp. 66-77; R. Șt. Ciobanu, op. cit., pp. 150-159; E. Stoian, op. cit., pp. 60-70. Tursun bei shows that Vlad Țepeș ,,... trusting in the High Porte, overcame the Hungarians, killing many of them..." (op. cit., ed.cit., p. 68), and Chalcocondil also states the following: "And the Peons (Hungarians - n.n.), not a few, whom he believed to have some interference in public affairs, not killing any of them, killed them in very great numbers" (op. cit., ed.cit., p. 283). In fact, Vlad Țepeș's incursions into Transylvania were directed against all those who were working against him, hostile boyars or pretenders to the reign, and who were thus violating the country's aspirations for independence (Pavel Binder, ,,Itinerarul transilvănean al Vlad Țepeș", in Revista de istorie, tom 27, nr. 10, 1974, pp. 1537-1542).

[20] One of the reasons for the hostility of the Saxons, craftsmen and merchants par excellence, was probably the adoption of protectionist trade measures by Vlad Țepeș (Gustav Gündisch, ,,On Vlad Țepeș's relations with Transylvania in 1456-1458", in Studies. Revistă de istorie, vol. 16, 1963, pp. 684-686; Radu Manolescu, Comerțul Țării Românești și Moldovei cu Brașovul (secolelele XIV-XVI), Bucharest, 1965; Dinu C. Giurescu, ,,Relațiile economice ale Țării Românești cu paesi de Peninsulei Balcanice din secolul al XIV-lea până la mediados la XVI-lea", in Romanoslavica, XI, 1965, pp. 167-201; M. Cazacu, ,,L'impact ottoman sur les pays roumains et ses incidences monétairs (1452-1504)", in Revue Roumaine d'Histoire, XII, no. 1, 1973, pp. 188 ff.).

[21] We find the opinion of the historian Șerban Papacostea particularly interesting, who considers that Vlad Țepeș did not pursue a protectionist policy towards the Saxon merchants of Brașov and Sibiu: "Vlad Țepeș's relations with Brasov and Sibiu, the meaning of his conflict with the two cities, as well as his entire personality and activity are distorted in historiography, partly because of some of the sources that recorded his deeds, stories in Slavonic and German, a mixture of reality and legend, partly because of an historiographical approach that placed the thesis before the source and research" (Ș. Papacostea, ,,The Beginnings of Commercial Politics...", p. 27). In the continuation of the argument of this point of view it is pointed out that it is certain that Radu the Handsome, brother and successor in the reign of Vlad the Impaler, instituted the obligatory deposit, which considerably restricted the activity of the Brașovs in Wallachia and at the same time intercepted their direct link with the Lower Danube (Ibidem, p. 28). Returning to the throne in 1476, and with the assistance of the Hungarian royal armies, Vlad Țepeș undertook, in fact, to annul the measures of Radu the Handsome: ,,... that from now on the scale of what was shall be nowhere in the land of my reign" (I. Bogdan, Documents concerning the relations of Wallachia with Brasov..., I, pp. 95-97; Ș. Papacostea, ,,The beginnings of commercial policy...", p. 29). If this is the case, and it is very probable, it follows that Vlad the Impaler's war with the Saxons of southern Transylvania and with King Matthias Corvinus was purely political (Ș. Papacostea, ,,The beginnings of commercial politics...", p. 30; G. Gündisch, ,,Vlad Țepeș und die Sächsischen Selbstverwaltungsgebiete Siebenbürgens", in Revue Roumaine d'Histoire, VIII, no. 6, 1969, pp. 981-992). It is also possible that the payment of tribute to the Porte, which Vlad Țepeș made regularly in the first years of his reign, until 1459, was interpreted by the King of Hungary and the Transylvanian Saxons as a gesture of hostility (M. Cazacu, L'histoire du prince Dracula..., p. 5). Also, as Matthias Corvinus had been holding secret talks with the Turks since the end of 1458 to conclude an armistice (Monumenta Hungariae Historica. Acta extera, vol IV, Budapest, 1875, pp. 36-40; Lino Gómez Canedo, Un español al servicio de la Santa Sede. Don Juan de Carvajal, Cardinal of Sant Angelo, legate in Germany and Hungary (1399? - 1469), Madrid, 1947, p. 199), it is quite possible that the Sultan saw Vlad Țepeș's action as an act of pressure on the King of Hungary, that he even gave his approval for the military actions in southern Transylvania and that he accepted, as something absolutely normal, the non-payment of tribute from 1459.

[22] G. Gündisch, ,,Vlad Țepeș und die Sächsischen...", p. 992. It seems that this peace and alliance agreement was a direct consequence of an earlier agreement with Matthias Corvinus (N. Stoicescu, Vlad Țepeș, p.89, n. 17; Radu Lungu, ,,À propos de la campagne antiottomane de Vlad l'Empaleur au sud du Danube (hiver 1461-1462)", in Revue Roumaine d'Histoire, XXII, no. 2, 1983, pp. 149-150).

[23] Ș. Papacostea, ,,The beginnings of commercial policy...", p. 29.

announced the crusade on 14 January 1460 (N. Iorga, Notes et extraits pour servir à l'histoire des croisades au XVe siècle, IV, Bucharest, 1915, pp. 166-168). Also, on 20 February 1460, Pius II offered Matthias Corvinus 40,000 ducats in case of war with the Turks, on condition that he did not conclude a separate peace with Mehmed II (Augustino Theiner, Vetera monumenta historica Hungariam sacram illustrantia, vol. II, Rome, Paris, 1860, pp. 351, 356-357). In turn, during the Congress of Mantua, Matthias Corvinus promised through his soldiers that he would participate in a possible crusade with a contingent of 12,000 soldiers (L. Gómez Canedo, op. cit, p. 212).

[24] The opinion that Vlad Țepeș openly took action against the Turks in 1461 and not in 1459 was expressed by Nicolae Iorga: "Only in 1461 does he change his behaviour: he returns to the traditional policy that had been his father's" (Scrisori de boieri. Scrisori de domni, 3rd ed., Vălenii de Munte, 1931, p. 163) and repeated by Sergiu Iosipescu, ,,Conjunctura și condiționarea internazionale politico-militare a cea seconda domnii a Vlad Țepeș (1456-1462)", in Studii și materiale de muzeografie e istorie militară, nr. 11, 1978, București, 1978, pp. 179-180. However, in the case of the two historians this opinion is not sufficiently scientifically substantiated. That is why we, being in agreement with this point of view, will try to support it with all the arguments at our disposal.

25] G. B. Picotti, La dieta di Mantova e la politica de'Veneziani, in Miscellanea di storia veneta, seria terza, tomo IV, Venezia, 1912. Pope Pius II, who was preparing the anti-Ottoman league, appealed for peace in Hungary, torn by fighting between the partisans of Matthias Corvinus and those of Frederick III of Habsburg (I. A. Fessler, E. Klein, op. cit., III, pp. 20-21; K. Nehring, Mathias Corvinus, Kaiser Friedrich III und das Reich. Zum hunyadisch-habsburgischen Gegensatz im Donauraum, Munich, 1975, pp. 15-16) and, despite the opposition of Venice and the imperial delegates, read the bull announcing the crusade on 14 January 1460 (N. Iorga, Notes et extraits pour servir à l'histoire des croisades au XVe siècle, IV, Bucharest, 1915, pp. 166-168). Also, on 20 February 1460, Pius II offered Matthias Corvinus 40,000 ducats in case of war with the Turks, on condition that he did not conclude a separate peace with Mehmed II (Augustino Theiner, Vetera monumenta historica Hungariam sacram illustrantia, vol. II, Rome, Paris, 1860, pp. 351, 356-357). In turn, during the Congress of Mantua, Matthias Corvinus promised through his soldiers that he would participate in a possible crusade with a contingent of 12,000 soldiers (L. Gómez Canedo, op. cit, p. 212).

[26] Luigi Bignami, Francesco Sforza (1401-1466), Milan, 1938, pp. 275-276.

[27] L. Chalcocondil, op. cit. ed., pp. 283-284.