Photo

The influence of Brecht in the arts

The dramaturge Berthold Brecht is better known in the performing arts, but he also influenced the visual arts sector.

Brecht lived under the period of German fascism and nazism, going through the First and Second World War. All his work attempted to change the course of these events, by trying to make theatre a reflection rather than a contemplation tool.

Together with the theatre-maker Erwin Piscator, they devised the so-called theatre of the scientific age, in which through the use of images, machinery, acting techniques and text, audience members would be become critical spectators.

Up to that date, theatre was broadly following the Aristotelian model, as described in his work Poetics. Following that model, audience should go through a journey, in which they would identify themselves with the issue being addressed on stage, engage with the actor’s performance, arrive at the climax of action, and achieve the catharsis moment.

It was a dramatic and highly emotional process, which Brecht wanted to tear down. In his view, audience should never identify themselves with the actors, but rather understand that theatre is not a representation of reality; actors are just the storytellers of the events and audience must act (or react) critically.

Amongst the techniques used, one can refer to the acting-game, in which actors would stop the performance all of a sudden, speak directly to audience, make mistakes - just to show that they were not the real characters, but agents of the story. Just like a tribune.

Brecht called this process the Epic Theatre, which has been very influential in theatre, dance or cinema. From Pina Bausch to Harun Farocki, Dogma 66 or Wim Wenders, all of them are clearly followers and some even quote him.

Yet, when it comes to visual arts, his influence is more diluted. Artists such as Asier Mendizabel refer to his influence - ‘the role of art is to render reality impossible’. (Mendizabel, 2010). And indeed, Brecht offered powerful techniques that allow artists to analyse reality, think images, question the relationship between man and machine and to better conceptualise and structure one’s work.

Clearly, one can see the influence of Brecht in many artists and collectives today, such as Forensic Architecture, who use forensic tools to dissect the work of political forces, governments and the like worldwide under a guise of human rights.

The work of Brecht did not happen in a vacuum. On the contrary, he benefited from the studies of Piscator that he perfected. Besides, the Epic Theatre follows the line of similar modernist processes - Picasso, with the Cubist collage technique, or Eisenstein and the Constructivist editing process.

Bibliography Mendizabel, A. (2010) Fire and/or Smoke. Culturgest, Lisbon. credits: Ana Mendes, Love and strength, 2021-ongoing, mixed technique, variable dimensions

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Larp Party / collaborative art practices

Over the last years, collaborative art practices have become more relevant over the last seven years or so. By collaborative art practices, one may understand collaborative work, collectives, activism or socially engaged work.

The reasons for this insurgence deal with the context - the fact that the society has been under increasing pressure from populist movements, economical strain, ecological disaster, pandemic and war generates new forms of working. It is not really only about working together, but to feel some closeness and to create work out of that experience.

In my understanding, art should not come with a purpose. Artists have the freedom to create, without serving a specific goal. But, of course that everything is political and even artists that paint clouds are making a statement by doing that. Besides, some artists are naturally more active and/or expressive and that his reflected on the work that they do.

One of these collective artistic practices that has became more popular recently is the ‘Larp Party’, common in the Nordic countries. To give an overview, this is an event what merges together notions of theatre, visual arts, food, private event (and conceptual work). In this model, the maker of the event, establishes a location and time for the party, and finds his/hers own guest-list. Each invited person is given a role, which is similar to real life parties, but as the maker imagines it. Let’s say, I imagine that in my party there is always a guy smoking at the door, another one running to the toilette, a girl attacking the fridge and someone hiding a cat in the pocket. I will then invite friends / whoever I want, and give each of them one of these roles. Equally, it could be a party for animal lovers or ghosts. Then, the maker of the party is responsible for creating the set up - decoration, music, food, etc. The guests are free to play their roles as they wish and dress accordingly, as long as they respect the main characteristics of their role and the parameters of the play.

‘Larp Play’ is, in my view, an interesting artistic game to play, which can be used as a devise tool - to create new situations, meet people, set up performance or film productions, etc. It is not as easy as it seems, because of the blurry lines - it is neither a theatre play, nor a realistic portrait, thus, it requires some skill to understand and play it ‘our way’. Perhaps, that is the reason why it is so popular among artists, as the blurriness of the game, which borders performance, theatre, live action, documentary, visual arts, dating, literature and private parties, makes it ‘imaginative’ and unpredictable, as artists like.

0 notes

Photo

Social sculpture by Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) was a German artist, who went through the Second World War, where he served. Beuys conceived that each life should be considered an artwork, in that the person seeks to evolve as a human being. Then, all persons together would be a social sculpture composed of different evolved-individuals. This conception of art was not extraordinary if we consider the context - Beuys lived in a postwar society. Thus, one may assume that the need for social healing was very high. And that explains why Beuys was so concerned with shamanism. Besides, Germany is a famously Marxist country, in which the collective always comes first. Therefore, by promoting collective well-being one would achieve individual satisfaction (and protection).

One of the most relevant works of Joseph Beuys was ‘7000 oaks’, which he initiated in 1982 with the goal of planting 7000 trees in Kassel/Germany over a five-year period.

It is difficult to understand the work of Beuys without thinking on Brecht or Walter Benjamim. Both thinkers conceived art as a politically emancipatory tool, which should make people more critical.

Also interesting to think on the connections with contemporary artists who work in the public sphere, such as Doris Salcedo, Francis Alÿs or Tania Bruguera.

(photo: Artificial Nature, Yongsan Family Park, Seoul, 2019 © Ana Mendes)

0 notes

Photo

Data Merge, the magic trick for working with archives.

After five years of intensive work in my project ‘The People’s Collection’, which explores the identity of people originating from colonised countries in regard to museology and ethnography, I finally managed to create the whole project on my own, using InDesign.

I have had wonderful collaborations with different graphic designers over the years, including in this work. But, because this work deals with archives, it is very difficult to pass to someone else so much information. The project is composed of a collection of over 337 postcards, two books, etc..., so, it is super hard work. I had to photograph, catalogue and archive more than 450 images, remove backgrounds, translate names, research, etc.

Thus, in 2020, as a consequence of the lockdown, I decided to improve my InDesign skills to be able to work independently in this project. Spending three months working on Photoshop and Indesign was very painful, but now I have all the archives in good order. If something happens, I can correct it myself immediately.

Learning InDesign is pretty easy, watching some online tutorials. One of the most useful tools that I learnt, was how to use the data merge function. Again, there are many videos online, depending on the specificities of your project. One of the simplest ones is this case. If you need something more complex, search your online as there more complex ones.

Briefly, data merge tool is a very useful tool, if you need to use archives - text, image, data, etc. With this tool, you can add all your data to an excell file organised by categories (e. g., name data, image, number, address, etc); then, design your model on InDesign (e. g., a frame for each category), import the execel data to InDesign, use the merge tool and automatically it produces all the designs, merging the model that you created with the information that you added, placing everything on the right place. On the image above, you can see the back of one of the 337postcards that I created using this tool. Instead of creating one by one, it was automatic.

0 notes

Photo

Advice to the 'young’

Although I am not an art teacher or academic, I have some experience on teaching / mentoring students / artists in universities, schools, festivals, residencies, etc.

What I learnt from that is that the most difficult thing for an artist is the balance between outcome and investment. Most artists / students do not want/ know how to go through the trouble, the pain that it takes to learn something without knowing if one is going to succeed or not.

Most artists want to achieve /see something happening regardless of everything. The painful truth is that in order to try something, one needs to do it the right way, how it should be done, regardless of the outcome. If it takes 10 years to learn something, without knowing if you will succeed or what that actually means, one has to do it. The important aspect is the learning process, not the outcome.

Although this may sound / be very paternalist, it is the truth, and the only thing that I would recommend to any beginner. What needs to be done, needs to be done – it does not matter what, when how, just do it.

I have been approached by many artists who ask me how to get a grant, exhibition, residency or whatever. My answer is always: I write the application as I imagine it in my head, my little dream. If they take me, I am happy. If they do not take me, I am also happy, because I will do the project anyway.

When I started to work many people asked me this question, and I always said the same. Then, some people told me: no, never do that, you need to have a statement, do it this and that; there are even people who pay someone else to write the applications for them.

I must confess that, by then, I panicked and though, oh my god, how come that I got it all wrong. So, indeed I tried to do it in that manner, which I did not know exactly how it was. But, it became impossible. I would just get blocked and could not write a line.

So, I did not have other option and kept doing my thing. Today, I still ask myself if I was right or not. I am sure that I wasn’t. No one gets it right. One is always learning. But, that was the truth that would fit me by then, and the one that I grew with.

Overall, I have this abstract feeling / certainty – one needs to do what needs to be done no matter what may happen. Not more, not less, just that. Doing whatever just to get x, will take you to nowhere, for the single reason that you will not evolve. And that is what matter, in my view.

0 notes

Photo

This interview could start with ‘Dear John’, a project of care conceived by architect and interior designer Marianna Karalioliou about the dwindling Brixton barrows, and more specifically the craftsmen that look after them. In a covid 19 world, projects about the public space and/or that look after community members are more than welcome. We salute you, ‘Dear John’.

In your project about the Brixton Market, you propose to create a space for John, the man that repairs the barrows. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

During the second and final year of my MA studies in Interior Design at the Royal College of Art, I chose to do my Thesis project in the Interior Detail platform, run by senior tutor Ian Higgins. The general subject of the Detail platform for the year was the re-use of abandoned railway arches in London. After a potential site exploration that the group of Interior Detail did in South London, we decided that the common site for our thesis projects would be the railway arches of Valentia place, in Brixton.

Having established a site, the next step was to decide what function I would insert in the arch to start building up my project. My personal research for Brixton led me to discover a very peculiar issue that has been rising concern among the locals for quite some time. The market's traditional barrows are dwindling in number, as the craftsmen that are able to repair these ageing vehicles are few and far from London. This would palpably alter life in Brixton market, as the stallholders still rely entirely on the use of the barrows to run their businesses.

This is the beginning of 'John's' story. He's my fictional craftsman that embodies the initiatives of the locals to save the Brixton barrows. In his live – work space, within a set of railway arches that becomes part of an imagined masterplan where a new public space is created, John lives among other makers and offers his craftsmanship to the market people, repairing their barrows and preserving the character of the market and the area in general.

- Do you think that markets are important in urban cities like London?

Definitely. I might be a little biased as I come from Greece, a country where markets are an integral part of everyday life, but markets do not only enrich a city's public life, they also create a micro-scale in the modern metropolis. This micro-scale is what transforms co-existence to conviviality, a quality that is quite scarce in urban cities, from my experience at least.

- One of the things that I like about your project is the combination between arts and crafts. As an architect, do you think that they are important?

I couldn't imagine the one existing without the other and I wouldn't like to imagine how life would be without both of them. Arts and crafts in their greatest manifestations, such as in Ancient Greece, Renaissance etc., were leaps in the evolution of human civilisation, but I believe that the significance of their harmonious combination in everyday life is of equal importance. The quality of our lives is substantially improved when objects and 'things' are both thoughtfully considered and beautifully crafted, not only serving their purpose of making one's life easier but also offering aesthetic pleasure, at some level at least.

- Do you think that these roles - like John and others that repair boats, work with woods, etc - are important for the sustainability of society?

I have enormous respect and admiration for craftsmen like 'John', and I believe that their existence will always be of crucial importance for the sustainability of society. Despite the fact that they are somehow the exception in an economy that fosters standardisation and mass production, their significance lies within the invaluable knowledge and skills that pass on from generation to generation and have been formed throughout decades of experience. The hands on approach that craftsmen have is characterised by, what I would like to call, a sentimental intelligence and ingeniousness, as the relationship they build with their work is something much deeper than mere production and has quite a 'parental' quality to it. I don't think that the knowledge deriving from such personal devotion to a craft could ever be replaced, even in the most technologically developed societies.

- How do you perceive the public space in a covid 19 context?

In a circumstance where the private sphere is becoming the dominant part of everyday life as it forms a safety zone, public space either maintains the identity of a space of decompression, or is facing the danger of becoming a zone where insecurity dominates. As the Covid-19 is a quite recent context, I think we are all trying to find a new balance and discover new ways of living in public. The way I perceive public space hasn't drastically changed, as I still consider it as a way out of normal, everyday city life. The fact that we have to re-adjust and follow a new set of rules for the protection of public health might create some restrictions in public life and the way we inhabit public space. However, as public space is a living space that evolves and adapts to current social needs and circumstances, I would like to perceive it as a space of undiscovered opportunities. I certainly hope that the new terms of a global pandemic will create the ground to discover new ways of safely living in public.

- People speak in human ecology, a term that I dislike, but your project has the beautiful quality of looking for the others in the city. Do you think that covid 19 changed the terms in which we relate to one another?

Thank you for your comment. The truth is that my project had started before the Covid-19 outbreak and the public aspect of it had already been addressed and settled before the massive change the virus brought in our lives. However, something that started as a need to create a proposal that would be closely connected to the site and become an organic part of the area rather than a proposal that would focus solely on the design of John's space, soon acquired an additional dimension. It was as if the neighborhood I was envisioning to be born and nurtured by the vibrant area of Brixton became a reminder of the importance of public life in an urban city. Covid-19 certainly pushed us indoors and made us build stronger relationships with our closest ones, but it changed the way we define ourselves in the vaster social network of a neighborhood, an area and a city. Social distancing has made people more alienated and suspicious to each other, which is quite a natural reaction to such an unprecedented situation causing fear to all. However, I believe that this numbness we are all feeling is somehow creative, as it is making us reconsider how we want our social lives to be particularly in urban cities, when things hopefully return to normal, at least to some degree.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Circularity of Time

The Infinitesimal and The Monumental Duration Spin & Weave: An Exploration of the Themes of Nationalism, Social Fabric & the Circularity of Time ‘

- interview with architect and interior designer Aarushi Kalra.

AM - Could you give a bit of context about the Gandhi project of using the hand spinning of cotton as an instrument to raise awareness of the independence from England?

AK ‘ In 1909, in an anti-colonial move towards Indian self- sufficiency, against the British, Gandhi decided to revive a craft many saw as already dead: the hand- spinning of cotton into thread, using the Charkha - the Spinning Wheel of India. He saw spinning as an economic and political activity that could bring together the diverse population of the country and was a defining symbol in the struggle against the British rule. It was a symbolic call towards a self- sufficient India, highlighting the ‘Swadeshi Movement’ - a part of the Indian independence movement that contributed to the development of Indian nationalism. This movement aimed to make Indians rediscover their sovereignty and strengthen their pride in Indian heritage, while also disengaging with the imposed British norms and boycotting all British goods. Gandhi claimed that spinning thread in the traditional manner could create the basis for economic independence and the possibility of survival for India’s impoverished rural multitudes. His choice to stand in solidarity with the poor of the country, while East India company was systematically exploiting them became a powerful symbol that then became the face of the movement and urged his more privileged followers to copy his example, and discard, or even burn, their European-style clothing, proudly returning to their ancient, precolonial culture. This simple act of spinning pierced through the varied Indian community, uniting all classes, caste, gender and creed into one cause and fabric. However, today it seems to be reduced to a static symbol; as a part of history and as a part of the India national flag. It lost its efficacy once its dynamic performance ceased to anchor a political movement. We retain now only the echo of its circular rhythm.

AM - How did you come up with this idea of exploring the idea of the spinning wheel as a tool for reflection, almost crafting through time?

Having grown up in India, Gandhi’s presence is all around us. Not necessarily as the figure we have studied throughout history, but as an integral subconscious symbol in day to day life – on the currency notes, names of the streets, etc. Moving out of India, for the first time, to pursue my post-graduation in London made me acutely aware of of my heritage. Moreover, at the time the news was flooded with updates on Brexit, the election of Donald Trump as the president, the building of the wall between US and Mexico and more news of the same nature from Russia, India etc. When we were presented with the brief that asked us to expose a political space of production that spanned the ‘infinitesimal to the monumental’, the symbol of the spinning wheel almost instantly came to my mind, as it was a simple machine and a simple activity that united the entire nation. I wondered how today the term nationalism has been broken and twisted to divide rather than unite. And as an extension of this thought, can it be argued that the spinning wheel that once spun the fabric of unity now spins the fabric of division? What once symbolized inclusivity now takes pride in furthering exclusivity? And that for me was the starting of “Spin & Weave”- a project that explores the theme of Nationalism, Social Fabric & the Circularity of Time. I was interested in investigating how a symbol, so intrinsically part of my own culture, can be revived to interact with present-day political, global occurrences. How a symbol of unity, can now represent boundaries? Based on my new insight into nationalism, this project was a way to explore whether this symbol out of its original context remains the same static image while showcasing the change of ideologies, or does it take on a new form and new meanings? The end piece was envisioned as a scaled model of an experiential installation which showed the two sides of the wheel. One, where a multitude of threads converge at its centre, representative of the people that would once come together to unite, while the other showed the same threads diverging into multiple directions disrupting the spectator's path and field of vision. To be able to traverse this space you might have to go over the strings or under them, cut them, tie them up, loosen them; but you have to make an effort to navigate this stretch. At the centre of all, is this spinning wheel, entangled in the boundaries it continues to weave. A wheel that cannot spin any longer but continues to monumentalise the act of spinning.

AM - Did you consider/imagined the meditative properties of spinning when you created your project?

“Take to spinning. The music of the wheel will be as balm to your soul. I believe that the yarn we spin is capable of mending the broken warp and weft of our life…” – Mahatma Gandhi

The process of spinning yarn is inherently meditative. It’s not something I originally considered at the beginning; however, it was hard to ignore it as I sat for days threading yarn, creating scaled models of the final output. There is a rhythmic cadence to it. It is monotonous, repetitive, but just as when you’re meditating it allows you lose yourself into it. It is a wonderful process to instil patience, stability and peace in an individual. Which in my belief had been of utmost importance at a time when the people of India needed to be level headed and find the strength to stand against the colonial rule. One of my biggest takeaways from this project was the lesson of patience and discernment. I learnt the importance of each individual’s effort in fuelling a collective power; which during the colonial time, created this beautiful, peaceful and unified fabric of my country.

AM - Do you think that there is a connection between crafting/identity and narration?

AK - In terms of physical and tangible materials, for sure. Every region, city and village boast of its own handmade traditions and skills, the ancestral knowledge embedded deeply in our cultures. The geographical location, environmental factors, and the available local materials initiated certain ancient practices that slowly got imbibed within the fabric of the place, which inherently defines its identity and a specific cultural viewpoint. Local materials are used to tell local stories in a particular cultural context. The way of using them only further adds to that. Anything that becomes tangible has an identity, and everything that has an identity has a narrative. Crafts are a way of giving shape to new forms, building a whole new database of identities and narratives in design. It enables the piece to embody the history, culture, socio economic political expression and the various personal stories and aspirations of the designers/ craftsmen. Art and design by nature are a form of storytelling. In no two cities or zones can the same art or craft be practiced in the same way. It is always adapted, and with this adaptation the story changes immensely across boundaries. This is the beauty of context in art, design and narratives. Any small change brought to any one aspect has a ripple effect on all the others, leading to a completely new personality of the base identity. An example of this is how from Japan's kimonos to Scottish tartan, and from Uzbekistani Suzani to Gandhi's push for Indian khadi, the culture of the world is woven, quite literally, into local fabrics. Though the machinery and techniques have been similar, yet throughout human history one look at a man’s clothing could tell you more than his words: his social standing, wealth, class, military rank and more. Historically cloth was unique to its region and country, sometimes literally tying in elements of the land and the people that live there. Even today in a globalized society where one can swipe through countries in no time, all groups of people have secrets hidden in patterns, dyes and fabrics that are waiting to be explored. - How do you think that we could share ancestral forms of knowledge without commodifying them? This is a very difficult conversation to have in the world today. There is a very fine balance between conserving and commodifying. We have lost so many art-forms simply because we haven’t been comfortable in the idea of commodifying them. There are various ways to share knowledge but as soon as they become quantifiable, it becomes a commodity. It almost seems to me as though we might need to change the way we understand commodities and become more mindful of the exchange of these. As a designer I believe in sharing ideas and culture, and I see no harm in others doing the same even if it comes at a certain cost. One can’t ignore the fact that one needs an income to enable these storytellers to run their own lives while comfortably dedicating their lives to the craft. This constant debate between conserving and commodifying, impacts the simplicity and the purity of exchanging stories and emotions through craft.

AM - How do you deal with the idea of orality associated with tradition? For instance, in African countries, many times traditions are never recorded, so, we lose them, but on the other hand that is how they evolve naturally... so, if we record them, we somehow kill them in the sense that they no longer transform/evolve...

AK - India has a very rich oral tradition. Take Indian Classical Music for example, where the original tradition of imparting knowledge over thousands of years was through recital with a minimal use of the written word. Recorded and written material developed, but only as a key to absolute basics. Beyond that, Indian classical music is still almost entirely improvised, improvisations based on these certain written ground rules. The same is true for most of our forms of Art, Dance and Scriptures. The oral tradition is in a sense trapped within the confines of a culture’s collective value system. It is first and foremost a group activity, and reinforces bonds within the culture, but it also depends on that group’s willingness to further keep the art of practicing and sharing alive. Writing, on the other hand, is an individual pursuit. Writing transmits ideas from other cultures that reside outside the local sphere and allows the individuals to interpret those ideas for themselves. Written or documented references not only cater to a wider audience, but also to a more distant generation; enabling them to enjoy, learn and reinterpret past stories, leading to a natural evolution that keeps these traditions relevant. The only drawback being the loss of understanding, guidance and the radicalizing of the written knowledge. I feel, this documentation must allow the artist to freely interpret and improvise this knowledge. The need of the hour today is also to learn the subtle language of symbolism and essence, not only to keep the traditions and rich stories alive as they were, but also to strengthen our understanding of each other’s thought processes and maintain a better harmony.

AM - Do you think that it would be possible to create a project that would connect young artists with old craft studios to create sustainable projects in India? What is missing in terms of business channels that could render these local projects visible worldwide?

AK - Every craft form is based on shared information that is continuously evolving. Formulating more and more collaborations where old traditions and skillsets are funnelled into the younger artists, along with a freedom to reinterpret them through their own experience and insight, might help bring these traditions to new light. Take for example how a khadi wheel works - the wheel is a form of analogue technology and weaving is a cultural idea. The practice pushes the technology and cultural idea embedded in it forward. Now, for a ‘young’ artist, some of these technologies or cultural practices may present a space of possibilities that may connect to their own practice; or a possibility where they can combine it in with the latest technologies - retaining its roots but giving the product a more global and widely accepted appeal. This may perhaps be a way to find a common ground and explore further. To a certain extent this has already started to happen. However what concerns me is that in the collaborative effort between the designer and the artisan, the designer gets all the credit and possibly the profit while the artisan has gained nothing more than what they always had. The need of the hour is to evolve the stature of the craft and the craftsman enough to give the artisans an incentive to believe in what they do, and for the younger generation to be willing to learn and continue this process. Now as far as contemporising the traditional crafts go, I believe it requires work in two divergent directions. One is that art forms and crafts become a natural part of life again, as they once were. An extremely simple example is how in parts of the country and world over plastic plates are being replaced by banana leaves. This was a common traditional way of eating in southern parts of India, and now again there are people working on spreading it across the country, not as a tradition or luxury, but as an absolute basic awareness. On the flipside, craft must also be innovated and made a part of high-end design. One that celebrates the craftmanship for its glory, and adds an aspirational ramp value to these ancient crafts. An example of that is furniture designers today are reviving and reinventing the dying craft of making utensils and artefacts by hammering brass—traditionally practised by a community of Assamese artisans, to create high end, contemporary and innovative products that are highly global in their appeal while the manufacturing techniques belong to the Indian handicrafts’ tradition of the country. Government, innovators, investors, crafts organisations and designers need to come together and work closely with the craftspeople; listen to their voices, build on their strengths, think out of the box and possibly create a regulatory body that connects various craftsmen to designers all over the world, almost like an open source. However, it needs to have its own regulations in place to ensure that artisans and craftsmen are not exploited, and can also gain from the exposure and the innovation, giving them a reason to believe in the craft they have spent their lives mastering, again.

AM - Ana Mendes

AK - Aarushi Kalra

Aarushi Kalra is an architect and an interior designer, recently graduated from the MA Interior Design at Royal College of Art. Currently she is in the process of setting up her own design wing based in New Delhi, India, by the name of I'mX - that aims to work fluidly between multiple disciplines. One that challenges and immerses viewers into provocative, layered and experimental environments.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Over the last years, many artists have turned to the idea of the archive - considered as a personal (the collection of our everyday lives) or collective idea (notions of present and past time). Yet, it is not everyday that one finds an architect who considers the city as a poetic space. So, to line up with this rarity, we spoke to Georgie McEwan the artist behind the A Poetry of Fragments, a work that reconsiders the archive as an interactive and spatial practice.

> Because you studied architecture, but your work is very poetic, how do you perceive the city as a poetic space?

Everyday we encounter poetry in the beauty of the discarded, the overlooked and the mundane- objects, spaces and interactions that comprise the city. Poetic encounters empower our creativity, where seemingly worthless things can become evocative by simply engaging our imagination. This becomes an alternative way of looking at the world around us, and enables us to experience the city, its architecture and its chaos as an unfolding collage of poetry.

> What are the challenges of adapting physical archives to the online format?

No two individual’s experience of archival material is the same. What stands out to one person may be completely overlooked by the next. Archives are characterised by the mystery of incompleteness and individual interpretations of the material. These interactions are much more distinct in the physical archive experience than the digital. For example, two pages of a sketchbook stuck together hides a diary entry, a photograph sticking out from a page catches your attention, a box of items is continually rearranged into a new random order after each visitor. What would the digital equivalent of these chance displacements be? I think that is where the challenge lies, in finding ways to maintain this level of curiosity and interpretation online.

> How do you relate to the concept of memory?

Memory is governed by ambiguity, misinterpretation and its inevitable fading. Legacy in many ways is governed by memory. My work uses poetry to reinterpret archival material and reorganises Derek Jarman’s fragmented legacy into a series of spatial iterations. Upon visiting an archive, and where you may not be able to take photographs of the material, all that you can grasp from the experience is the memory of the material, and perhaps some notes or sketches. The material becomes translated, reinterpreted or forgotten. In celebrating these qualities of memory rather than rejecting them through preservation, a legacy can be celebrated in the present, played with, scattered, re-imagined and abstracted.

> During the confinement, did you transform your home in a poetic landscape?

In some ways, the confinement provided me with the necessary constraints I needed to explore ideas around collage and assemblage in a truer sense. Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau was an important influence for me during the construction and assemblage of my archival stage set piece, A Gaze Through The Window. In the same way Merzbau developed into an unfolding room-sized sculptural construction, a three-dimensional collage, the conditions of lockdown meant that my work became a sprawling assemblage of objects and materials composed from limited accessibility, in my own bedroom. For example, I fixed an old canvas frame wrapped in chicken wire to the ceiling to hang pieces from. Salvaged timber floorboards were vertically aligned for the backdrop. Upturned flower pots were used to prop up the model base. Models were cast from scraps of cardboard collected over the lowdown period. A Gaze Through the Window now only exists as a single photograph of the model, the landscape disassembled back into the mundane bedroom after lockdown was lifted.

> How do you balance the rigorousness of architecture with your imaginative randomness of Dada?

It is a difficult balance, but one I think is important to explore. In Dadaism, chance was a tool to loosen control of disorder, to challenge artistic norms - something that I think we can engage with in architecture today. It is often the ambition of the architect to prevent chance happenings, to maintain a resolved finality to the architecture, to reject entropy. Yet in reality, architecture is a time-related process where buildings are unfinished and subject to an ongoing assemblage of material and social unravelling. Spatial experience can be enriched by placing trust in an unknown outcome, in embracing the inevitable adventure of uncertainty, of randomness and imagination. When the architect assumes more of a poetic role, realities can be imagined beyond the limits of deterministic design, and the architectural outcome is richer in creativity and openness.

Georgie McEwan is a spatial designer based in London and Berlin, whose practice is engaged in the boundaries between architecture and art. More details at: https://georgiemcewan.com/

© credits photo: A Gaze Through The Window, an archival stage set (Georgie McEwan).

0 notes

Photo

Interview with Prof. Jean-Baptist Joly, founder and former director of Akademie Schloss Solitude (GER)

- in which we explore the connections between talent, skill and personality/identity and he role that institutions play in the formation of artists. The interview bellow is a transcription of a talk held on Zoom. It was kept in its original format to preserve the rhythm of speaking/thinking.

JBJ Yes, I can say a few things as a kind of introduction. I very much like the questions you put about the construction you had to build when you found an institution dedicated to artists, between things that are very difficult to catch, like, as you say, “identity”, “skills”, “aptitudes” or even “talent”, and a sustainable institution that should be somehow successful. It means finding good people or good artists and working with them in optimal conditions. My first question was really about: how can I do this if I don’t think that I can measure or find a system to measure any kind of quality of how good the skills of the artist are or how bad or how talented he/she is or not? And my point of view was not about the personalities of artists. I would say personality rather than identity. I think that identity is a dangerous word… somehow you always add to identity words like “social”, which is how people think that they belong to a cultural group or “national”, believing that you are only defined through a national community. I was afraid of this, and I tried to come back to questions like: how do we recognise nowadays (a question of the late eighties/early nineties), how do we recognise qualities in a piece of art, which means in the product of the activities of an artist, talented or not talented, how do we recognise quality, or a potential? And all those elements are impossible to qualify. But somehow it is possible to trust people who have an expertise about what is happening in the field of art, because they know the field, because they know artists, because they have considerable experience and are never sure that the expertise is definitely the right one, or definitely positive. Combining those elements of expertise, knowledge of the artistic scene, knowledge of decisions taken by institutions, museums, Kunstverein or such like, you could find a way to agree that, yes, someone is a good artist, and it would be worth giving her a fellowship, for example in Solitude. My point of departure was not about entering into psychology or cognitive sciences, but about obtaining good results with something we can’t qualify. In mathematics you can have an equation for which you use imaginary numbers, but you can’t know how to define them; however, at the end they disappear and you have the results. This is somehow the way how I tried to think about it. I do not know if it is clear for you… my idea was to recreate the moment when somebody says to an artist: I recognise the quality of your work and I think that I have an idea about something that would develop you further. So, when we look about history of art, we always know the names of the very famous artists who made mankind better or who gave an different understanding or a new view on things, but we always forget the go-betweens, the people in-between who were somehow giving the right information at the right moment, pushing with the contact, helping, supporting. They might be art critics, artists or anonymous people. Somehow it was the role in which I saw myself. I used art history as a tool or a given experience that would inspire me to establish a new system in the art world. 30 years ago, I was always using the same example of somebody like Brancusi, the Romanian sculptor, who is one of the most important artists of modern art, transforming the notion of sculpture after Rodin. When you look at his biography you have at a certain moment someone who is pushing him, giving him information. Somebody told him to go to Bucharest, then to Paris, and see what Rodin was doing there. It is exactly like it might, probably, have happened to you, Ana, when you applied for Solitude! Someone told you: Ah, I think that it fits for you – you should apply for this programme!

AM Yes, exactly, that was the reason (laugh)!

JBJ And for me this is exactly what people call nowadays a meme: you are a carrier of information. You are not the subject – the meme is the subject that is carried by your mind; those memes that are moving from one head to the next, from the person who knows to the person who should take the right decision following this information. The meme is the subject that is leading you to apply, and when you enter into the game of application, you are confronted with the selection system, with those experts taking decisions about who will have the fellowship and who won’t. This was quite daring for that time to impose single decisions by single persons for a jury. Because in cultural institutions in the twentieth century compromise is almost always the solution, but it doesn’t give only good results. I wanted to have clear decisions taken by identified individuals with a jury chair, (man or woman, we had both in the 30 years) looking precisely at the personalities of the jurors, making their own opinion about the personality of the selected artists. I trusted this system because I trusted the people who were in charge: the jurors would not do this for taking advantage of it – they would somehow step back from their own questions or interests, because they had a clear understanding of their responsibility and trusted the institution. As you see, the first step is finding a person that corresponds to this expertise, with the knowledge and the right behaviour, and then trusting this person. In your questions you do not mention trust, which is for me the key word of the construction of Solitude: I trust you and now you take decisions, choose jurors in all the disciplines of Solitude. In 30 years the number of disciplines increased; we added sciences, economy and so on. And when the jury chair made decisions about the jurors I spoke with every juror, and said again I trust you, you will be alone to take decisions, you will be responsible for your decisions and we will follow them all. Next step: when the selected artists arrive at Solitude you tell them (again!) I trust you, and we will follow you with your ideas within our limits (budget, legality etc.). When you look at this system, it is expertise first, then trust and trust again. When I look at the results, I do not know what talent is, but I know that with this system we have promoted something like 1,500 artists and I would say they might be considered, almost all of them, as serious artists. This would be my answer to the first part of your question – let’s now speak about to what extent talents or skills can be taught or acquired. In a place like Solitude you find artists with their primary education behind them. For this reason we did not have to deal with the question of teaching and acquiring the basic knowledge and skills for being an artist, but I am sure that it can be taught: basic skills like drawing (the best way to mark down your thoughts) can be taught. Drawing can be taught to a certain extent, but self-taught activities and self-education are even more important. What you learn as an artist is to deal with yourself: how you look at the product of your work, how you look at yourself being an artist. The French writer Gustave Flaubert said of himself that he was not talented at all, (je n’ai aucun talent d’écrivain), but he was his most critical reader, corrected mistakes and read and reread his texts, and was merciless to himself. For me this critical way of looking at the self is the thing that can hardly be taught; it is in yourself or it isn’t. A young artist that is so promising might be later disappointing, not because of a lack of skills or talent, but because of not having the right way to look at her or himself.

AM Because I also felt that, I think that my last question is also about the fact that we have so much time to ourselves and yet we have no expectations that somehow also focus on ourselves. And then you have to think about yourself, and you have to organise your ideas to allow a lot of time for yourself, for reflection. I also felt that it was important. But something that also happened a lot at Solitude was that there was a lot of mutation and share with artists. So, there were a lot of collaborations, and some artists also had time to think about their work; there were some artists that decided not to develop a project, but rather opted to think about their work, and in the end they decided to somehow shift their practice somewhat. So, for instance, the case of Xinjun [Zhang] is an artist that decided to spend some time working with the projects of other artists that also tried to experiment working in different forms as well. I think that, in this way, he did not change his identity nor his personality, as you say, but I think that somehow it allows him, allowed him, to work in a different way and to discover new things about himself.

JBJ So, should we speak now about collaboration or rather about the notion of time? Which do you prefer…?

AM As you prefer…(laugh)!

JBJ Okay, so, let’s follow your lines: the second question deals with collaboration “in a time when so many artists work collaboratively for economical, artistic and deontological reasons”. What do you mean by deontological?

AM Yes, because I think that a lot of artists also feel that it is more sustainable to work with other people, it is also a gesture towards society, because you are sharing your ideas and your resources, and you somehow dedicate your time, not your representation about yourself, but to work with other people. I think that this current crisis, the corona crisis, brought a lot of these issues for some artists. I’ve already heard of some colleagues who decided that they don’t feel like working anymore because they feel that art is not useful or that it is very difficult for them to overcome this. So, that is what I mean by deontological – that it is the perspective that is more sustainable in this sense.

JBJ When I read this sentence I am missing the enthusiasm and the fact that people working on the same project are convinced that it is important to do this because they are sharing the same conviction. For me this is more important than economic, artistic or deontological reasons. They are convinced that this is a necessary step to be done. For example, if you are missing something in your own skills, you have to work together with somebody else. I would say it is a shared notion of necessity of working on a project that brings people together. Regarding this notion of talent, skill can be enhanced through a shared system. Let’s take an example outside of art: you probably remember that France was world champion in football in 1998 with a team built around a great player, Zinedine Zidane. This team really produced its own qualities from the presence of two or three extremely well-gifted people who brought the rest of the team to their level of perfection. If you have two or three people who are extraordinarily, let’s say, skilled, then they will take everybody with them to this level. Same in 2016 when Portugal won the European football cup with a team around Cristiano Ronaldo.

AM Yes, I remember when they won, but I must say that I do not understand very much about football, but I remember that episode when Portugal won – I saw the game, but I did not focus on that because I do not really usually watch games, so I was not aware of that parity.

JBJ And, for me, what was important in the organisation of the work in Solitude, about this notion of shared activities, was the fact that we should organise a system, a biotope, in which people could meet without having the pressure of a possible intention of the institution on their back. The whole system about the internal presentations in the academy at that time was really around people being in the same room, or monthly dinners, where people have the opportunity of meeting each other. They might be interested in each other, from the personal rather than from the artistic perspective, so they could enter into a game of mutual curiosity. Those internal presentations were organised in such a way that each of the fellows was on certain days a pupil; on other days a teacher. This exchange at an equal level, being teacher and being taught, being a pupil and being the one who explains, this was for me the backbone of a continuous education system working outside of the hierarchical relationship between the teacher and the pupil. Everybody is playing the role one after the other. This also explains the way how the artists in Solitude could identify with other artists. How they could become friends. It was the intention of the institution to put them together, but it happened, but we tried to make it not too apparent.

AM Interesting…

JBJ This is the reason why we let the fellows themselves organise the internal presentations, not the staff. If people from the staff attended those presentations, they did it as individuals, as private persons, not as staff members.

AM It is true no one would comment, make comments or questions about the work. It was among the fellows. It was a parity. I remember that.

JBJ Exactly, yes. Then you ask about identity and talent. So, I told you the word identity, for me, is quite dangerous and I prefer to speak about personality. When I was a kid I had recurrent fights with my mother who was so proud of the history of her family, and who was always explaining that we are very talented people and that it was innate, that it came from the genetic quality we had inherited and so forth. So, she really thought this. And she still thinks like this because she is still alive. On the other hand, I always answered that what we are and think is all acquired; it has nothing to do with being innate. We were both wrong because the notion of personality is the result of a mix of biological and environmental factors that are totally intertwined. It is not possible to make any differentiation between what is innate and what is acquired. So, I think that when you have a strong personality or a personality that is remarkable in front of you, personality and talent are related, but I do not know how to identify talent. I see that some people are very well skilled because they learnt to draw or to sculpt or to write, but I think that, indeed, it is an integral part of the personality, especially of the personality of an artist, for which this expression is not something different – it is an integral part of daily life. An artist doesn’t make any difference between “Am I working or am I private”? “Am I retired or am I still active?” The life of an artist is probably a unity with a continuity between working, thinking or hanging around. When you think about what an artist has to accept in his or her own life for being an artist, what he/she has to give up, like a secure income, for example, a family, or getting children, then you understand how high the price to pay is. This is the reason why I admire them, because I know what is at stake when you decide to be an artist, and this is also where my respect for artists is coming from. In Solitude we tried to follow these principles with the staff in our daily life with artists.

AM It is true, it is a very good point because I think that eventually the most truthful… way of understanding an artist or identifying being an artist is this interconnectivity, so, you are an artist full time and it is an extension of everything that you do.

JBJ It is like entering into religion or engaging yourself as an activist. You Have to give up so many things, and it is the same for an artist.

AM It is true. There is no other way, basically. Either you are, in this sense, or..

JBJ Yes.

AM It is true. It is a very good definition, actually. I also thought that it was very interesting when you spoke in the beginning about this sort of connector or mentor, which is people who can…who have expertise or knowledge, and who can identify people who are skilled or talented in specific areas, because I think that it also connects with education. Like when you go to school, or sometimes not only to school, but there are people that I would say…I always have this notion that there are specific people who I met in my life that changed my life because they either gave me an opportunity, they recognised something, but something is not, something is not clear that you are already showing a certain skill, but they think that you could maybe do this or you could do that, and so they challenge you. That is a very blurry part and that is very beautiful – when actually you teach them that you can recognise some skills that are not yet revealed in someone and you can help them to develop these skills. It is a very beautiful part of teaching. And I also think that, I did not, I never think about this, but it is true, that the problem with jurors is that when it is a mixed jury, it is a negotiation. When it is a single decision, it is a bigger responsibility, but it is also the outcome of a process, a thinking process, so I think that it is more integral, whole, the process. It is true.

JBJ Then you have this wonderful question about the artists who are given time. There are different aspects in this question. One of the aspects is that artists joining a residency programme are professionals who know better than you what their needs are made of. If you commit them to things that are outside of their needs or interest, it is not worth it to be in this place and to be financially supported. I remember very well when we hosted the first artists, in July 1990. When the first group arrived I told them (as I have done in all the years after!): “The time you will spend in Solitude belongs to you and not to the institution”. I was sitting at my desk, waiting for the first artist who would knock at my door and tell me that she or he had an idea for a project, and we could start something that would be realised there. The first one came after just three days and it never stopped until I left the house, 30 years later. It never stopped, it was an ongoing process! After the first one had come other people said – Ah, I could imagine myself doing that, then the machine was working on its own. If you consider the fellowship submitted by some obligation, you create a contractual relationship – and I wanted to avoid this. If you are given time, and if I wait for you to come and say what you want to do, I can say yes, and it is not a contractual relationship like if I had given you a contract with what I expect from you. I did not say I expect something, but indeed something was expected. Less in terms of a product of art, less in terms of an activity or an event, but in terms of being actively part of a network. I wanted artists to recognise the value of being part of the Solitude network because I knew that this network would somehow be the way to make your future better after the time in Solitude. You, Ana, told me that you met former Solitude fellows when you were in New York, that you had a contact in Stockholm and so on. This is a part of the support that you got from the Academy: Being part of a network and being in touch with people you met there. At the beginning some artists were suspicious and asked us about the hidden agenda behind the support they got from the Akademie. What are you expecting from us, the artists? What is it? Will we be, at some point, instrumentalised by a government or an institution? Do we have to be a decorative backstage for the Prime Minister? Or will the politicians justify bad decisions by the fact that we are here, that we are the good side? It was very difficult for me to express what we were expecting, and indeed it took two or three years until we understood what it was. Around 1993 we used the term ‘network’ just after it became usual, naming exactly what we were doing. After a couple of years this network would make the institution influential worldwide, which is indeed what happened. Thinking in terms of a balanced exchange between what you give and what you receive is essential in this relationship. This is a point I underestimated at the beginning of Solitude, and I was wrong. Then you say: “In my view the artists are the makers of their lives and works. Do you think that this model, as I perceive it, enhances the definition of the individual and in this manner of their artistic career, meaning if we have to sort out ourselves, surely, we can do the rest?” If you…?

AM Yes, yes, if we, the artists.

JBJ I never thought that way. I think that I had rather, somehow, a kind of Protestant (although I was not educated as a Protestant) point of view about loneliness and about the responsibility you carry for yourself. If you put people in a situation where the time belongs to you and where you decide what you want to do, good artists would know how to deal with this, and bad artists would have difficulties with this. Somehow you would see clearly which artist is and isn’t worth it. But the question you posed is a question for you, for an artist looking at the institution from outside; it is not the question of the institution. It is another point of view.

AM I understand…

JBJ I think that it is very important that you see the position of the artists in the Academy is not the same as the position of the team. We could do all this work in the Academy because we are the non-artists, and our job is to understand artists. So we can be very close to them, we can help them, but we are not artists, and this is the condition under which the institution works because we know that we there is a clear difference between the two sides. Many artists’ residencies are run by artists offering another relationship to their guests, another kind of identification with the house, the art works, the artists. In not-so-well-organised residencies run by artists this is a kind of excuse: “We are artists too, you know, so you can’t demand so much from us, from our residency centre.” In Solitude we were clearly not artists, and we were not seeing ourselves as artists. When I was talking to artists about their work, it was always from the outside.

AM Yes, it is true. It is important.

NOTES

AM Ana Mendes

JBJ Jean-Baptiste Joly

[] means text that was not originally in the recording and was added to facilitate the understanding of the idea.

This interview is a direct transcription of a talk recorded on Zoom and has not been edited, except minimal proofreading corrections for grammar and spelling issues. For this reason, repetitions and mistakes may naturally occur.

Credits - Ana Mendes, Drawing Series IV, durational performance, 3 m x 2.5 m, 2019 (c) Ana Mendes

0 notes

Photo

Introduction to animation In this post, I am going to do a crossover between animation and collaborative work. This means that I devised a short exercise in animation and, simultaneously, created a collaborative loop with the artist Zephyr Alad, with whom I have worked extensively in the past.

My idea was to show how we can create a simple animation using text. I used a common saying ‘No pain no gain’ and created two different exercises that I then passed on to Zephyr.

In this first one, I used the words ‘no pain’ ‘no gain’ and ‘no’, as an object and animated them in photoshop. Using photoshop, you can create a very simple gif, which can, nevertheless, be quite playful. There are plenty of tutorials online, which you can watch, like this one. In my case, I created some compositions with stamp, ink and paper, scanned them and copied these images a certain number of times, and using photoshop created a stop motion animation style gif. You can watch the exercise here.

Afterwards, I tried a second method using the same idea/principle. This time, I used After Effects, created a composition, chose a text layer and wrote the same words ‘No pain’ ‘no gain’ on my composition. Afterwards, I animated them, using position key-frames. Again, you can watch tutorials online to learn how to animate text on After Effects. Finally, I decided to play a bit with rhythm, and used some repetition with the word ‘no’ in the end of the animation – so, it comes like this ‘no pain no gain no no no no’. Similarly, I could have reversed the order of the words ‘gain no pain no no’, ‘pain gain no no’, etc. My idea was to use a very simple trick, in this case the saying ‘no pain no gain’ to create a very simple animation, and explore the connection between words as language and image/signs. You can watch my exercise online here. While making these exercises, I spoke to Zepyhr about this project, and he agreed on taking part in. Thus, we set up a date on zoom, discussed what I had made and his plans, what methodology we had used.

Finally Zephyr Alas, created a different exercise himself, departing from my idea, which he used diversely, recorded a video tutorial and send it to me. In his case, Zephyr, played with different notions of space, time and composition, and created a complete animation, which as a more finished/graphic design tone. You can watch his tutorial online and get an idea of this approach and skills used, which are more advanced. Enjoy!

Credits - image (c) Zephyr Alad

#aftereffects #tutorial #text #language #animation #adobe

0 notes

Photo

In this post, we spoke with London based artist Daria Jenolek (DE) who works at the intersection of art, design and technology, creating immersive installations. In her work she explores the connection between nature and technology. Daria creates works that, although being digital, refer to the real world, in that she explores phenomena such as air pollution, the Northern Lights or radio waves.

AM: In your works, you explore the intersection between nature and technology. You have said before that you were always interested in nature. Why did you choose to address it in a digital form - people quite often imagine nature as something very tactile...

DJ: My interest in nature derives from my passion for the matter of light. Light can be natural and artificial at the same time. This duality was the starting point of looking deeper into biophysical and digital nature.

AM: In my view, your digital works have a very sculptural dimension, in which light, colour and movement mingle, as if you were building a materia out of that. Would you agree with this interpretation?

DJ: This is a very beautiful interpretation and I would agree with it. I am interested in combining digital and physical elements, which often result in immersive installations, combining moving image, light and sculpture.

AM: Although you are clearly a digital artist, your works dialog with real events - for instance, the wind seems to be implicit in the movement that you create, transitions, fading, merging, etc - it is a continuum.

DJ: Besides the interest of exploring and combing natural elements with technology, I always try to create art installations in which people can relate to real world elements, such as natural forces including wind and cloud formation as well as technological objects in our indoor environments, such as mobile phones, fridges, etc.

AM: Artists are usually very attached (even possessive) to their 'things' - our paper, pencils, fabric, photos, cameras, etc. You seem to be very detached. Do you think that it is related to the work that you create, in the sense that it is very immaterial?

DJ: Even though I am a digital artist, I started sketching by hand again (approximately a year ago). Now I am very much attached to my physical notebook. I realised ideas and thoughts need to be sketched, a way which makes it easier to communicate an idea. However, I am very much attached to my computer, a routine of different software and ways of archiving process.

AM: How would you conceive social responsibility, as an artist, considering the digital platforms?

DJ: As an artist working with technology I personally see it as my duty to reveal, discuss and reappropriate misuse of technologies.

AM: Today, artists struggle to convert their skills into a virtual format. What advice would you give to an artist that is trying to transition to a virtual/digital platform? Are there any programs that artists can learn by themselves or that would be useful? Where to start?

DJ: First of all, please follow your passion, heart and what you really love. Do not feel you have to transform into a digital artist just because circumstances such as a pandemic occur. I believe documentation is key to the work, put as much effort into the final documentation of the artwork as into the artwork itself. In that way it can be experienced online and people will enjoy watching the documentation of your artwork. However, if artists are interested in the digital world, I recommend starting with film, then try animation, eventually 3d animation which then may lead to interaction. This is true for sculpture, start using off the shelf motor and tech and then programme them step by step with microcontrollers. Believe in yourself and be aware of the fact that you can achieve anything with the help of the internet. There is a tutorial to any single digital element you would like to create, and do not hesitate to ask people for help or mentorship.

AM: Ana Mendes

DJ: Daria Jenolek

photo (c) Daria Jelonek and Perry-James Sugden, Growing a New Landscape, 2018, installation

0 notes

Photo

Intro Adobe Premier and After Effects Some artists have asked me tips on how to use Adobe Premier and Adobe After Effects. There are plenty of tutorials online that teach how to use these two programs, which can be complemented with working sessions from your artist-peers. At the Artist pair-up skill page, you can check some contacts of artists available to help you. In case you wish to get personalised advice, please get in touch and we will try to find someone to help you.

As a starting point, we would recommend watching this video with Mark Christiansen, part of the Lynda series, which gives an overview of both programs, and explains what their function is. We will not repeat in this post this information, as it is so well explained in the video. After watching the video, we would recommend that you try to watch other individual tutorials online, which will help you with specific tasks, such as creating a new project, best settings, how to export, etc. Next step would be to create a project, using some footage, which you can easily get online. Every time you encounter a problem, google it and watch a new tutorial. Finally, take notes of your main questions, difficulties and issues, and get in touch with a peer-artist willing to help you, and work together. Working online via Skype or Zoom is perfectly fine. This method should speed up your learning process. If you require assistance from a specific professional/skill, do not hesitate to get in touch. We do the match up for you.

0 notes

Photo

In this post, we spoke with Albert Barbu, graphic designer and visual artist, based in London. The main motivation - or curiosity - deals with the fact that, in Barbu’s works, composition/rhythm seems to be a very important element. So, we wondered to what extent his work his influenced by his French roots, and within that, the rhythm of the language 'infects’ the individual and his work.

AM: What is the aspect of graphic design that you like the most?

AB: I think I like its emotional power, the fact that it can create emotions with minimal shapes or colours. There are simple fundamental principals that - if you apply them correctly - can create something beautiful and poetic at the same time.I sometimes feel I am creating magic tricks for the eyes because the brain interprets visual cues in a peculiar way.

AM: Do you like to create typography?

AB: I tend to use typography as a matter, something that I can play with. I haven't been creating fonts but if I do it would be for a very specific use-case or project.

AM: When you think about typography/language does it come to your mind with a certain rhythm or do you perceive it as still?

AB: I'd say it rather comes with a sound and a movement. A letter in a specific font has a specific sound - or aesthetic movement. When combined together they create sound compositions in my head. Then, with sounds you can create rhythms. This sound - or rhythm - of a word in a specific font is different from the sound of the same word pronounced orally by language. Language originally gives birth to the word, but then typography gives the word its own alternative sound identities.

AM: If you think of a certain word - say 'bread' or 'cheese' does it has the same rhythm in all languages?

AB: Both are different. If we take French as an example, "pain" (bread) is shorter - both in terms of the letter count but also how a person would pronounce it. This is the mother language which gave birth to the word. Now if we look at the typographic sound of it, "bread" is a packaged set enclosed between "b" and "d". It is stable but it's closed. On the other hand, "pain" is rising from the ground (to movement of p), then evolves and remains open. It is stable but it's open. I wonder if this movement reflects the way that bread is interpreted in both cultures. I always felt that English bread was quite industrial. Bakers follow a protocol to bake it and that's it. People eat it because they're hungry. French bakers on the other hand, work with the grain, develop their own flours and bread is always on the table, it is shared and social.

AM: Do you think that French language, which is very rich in terms of sound, creates a different rhythm than let's say German which has harder sounds or English that is very versatile?

AB: Absolutely. French sounds a bit like Roccoco, German like Cubo-Futurism and English sounds like... Pop-Art.

AM: Ana Mendes

AB: Albert Barbu

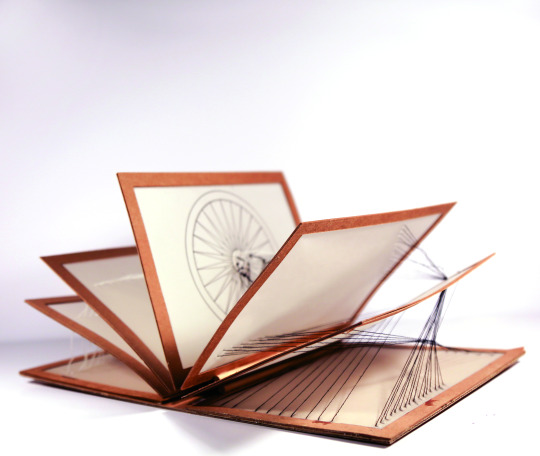

Credits - Ana Mendes, The Little Book of Germany, 2019, artist book, 14 x 9 cm. (photo: Ana Mendes)

0 notes

Text

Futurelearn.com

Some useful resources. At Futurelearn.com one can learn many different skills, from language, history to law or coding. Future Learn is a digital education platform initiative created by Open University. Many of the courses are free, but there is an option to upgrade and get more content.

0 notes

Text

Natural Dyes (with avocado)

Recently, while giving an artist talk at the Estonian Academy of Arts, Talin, one of the students, Laura-Maria Vahimet, asked me to explain to her how to dye with avocado. Thus, I am publishing this tutorial, as it can be useful to more people.

I started to use natural dyes, last year, when I created my project ‘Artificial Nature’, at Yongsan Family Park, Seoul, and Lagos Biennial, Nigeria.

In the image above, you can see some of the experiments that I created there with different materials - from left to right - synthetic colour, cherries, onion, synthetic colour, avocado, synthetic colour and berries. Comparing the tones, you understand that all of them clearly relate with the source material, except avocado, which turns out salmon pink. This surprising colour is also one of the most stables that I have seen - many times the natural dyes do not produce uniform colours.

In order to dye with natural dyes, you need two basic things – choose the fabric (silk, wool, cotton) and the material (avocado, wood, rust, etc). With these two elements, you can experiment with different techniques – time, temperature, mordant, etc.

In my view, natural dyes is a process similar to developing analogue photography. To see the results, you need to stick to one material (i.e., silk, cotton) and product (i. e., coffee,soil) and play around with different techniques to see what happens. Once you have an understanding of how the materials interact with each other, you can add more options. Yet, be aware that the natural dyes never produce the same result – water, temperature, pots change the outcome. You will not be able to achieve the same result twice, but you can get an approximation.

In this tutorial, I will stick to the fabric - silk - and material avocado. Silk is one of the easiest materials to dye, as it is a protein fibber, the dyes adhere to it easily. The same happens with wool. On the contrary, synthetic fabrics are nearly impossible to dye.

Avocado is one of the most beautiful and surprising natural dyes, as it turns out salmon pink. Nevertheless, last year, it happened during one of my experiments that it produced a very beautiful olive green colour. I tried to repeat the same process minutes later, but I never obtained green...

This tutorial is very brief, as it is meant to artists, so that you can make some trials and check if you like natural dyes. If you want to proceed, you can watch a tutorial online or send me a message.

Briefly:

I – Prepare the fabric, the mordant

First, you need to prepare the mordant, so that the natural dye adhere to the fabric. Fabrics are, usually, prepared with chemicals – that is why they look stiff and shiny when you buy them. These chemicals prevent the natural dyes from adhering to the fibbers. Besides, the natural dyes will not last long if you do not use a mordant and, in some cases, a fixative. I will not explain the fixative here, as this tutorial is meant for someone who wants to play with natural dyes, so, it does not matter if they will last long, as it is a test. If you want to know more about fixatives, send me a message.

Thus, the mordant is a process through which the fabric is prepared to receive the natural dye. To prepare the mordant, you need to choose a specific product - choice depends on the fibber type, desired effect and dyeing material. In this tutorial, I will use Alum (Aluminum Potassium Sulfate), which is the safest solution. You can buy it online.

How to prepare the mordant:

1 - Weight the silk and prepare 25 mg or alum per 100 gr of silk.

2 – Let the silk (fabric) soak in a big pot with water for 24 hours.

3 - Dissolve the alum in a big pot filled with warm water. You need to have enough water to cover the fabric very well. Add the silk. Place the pot on the stove and let the mixture stir in low temperature for one hour. Turn the stove off. Let the mixture soak overnight.

4 - Remove the silk from the pot, let the fabric dry and store it to a future use.

II – Prepare the dyes

1 - Soak the silk again in a large pot with water (room temperature) for about one hour.

2 – Prepare five or six avocados (peels and seeds) per 100gr of fabric. Cut them in small pieces so that the dyes are extracted easily. The more avocado you use, the sharpest the colour is.

3 – Let this mixture stir at low temperature for one hour. Turn the stove off and let the mixture cool off, for some hours or overnight. Again, more time increases the intensity of the colour. So, you can decide.

4 – Filter the mixture, throw the avocado away, place the liquid on the pot, let it stir at low temperature, add the wet silk, let it soak for one hour; turn the stove off and let it cool down for a few hours. Afterwards, wash the silk in cold water, let it dry and check the result.

4 – Finally, you can play with these steps to obtain different results. For instance, you know that the more avocado you use, the strongest the colour is; temperature produces a similar effect, as well as the stirring time. Some people dye the same piece several times, by continuously, warming the dye bath, adding the silk, washing with water, stirring again, and so on and so forth.

5 – Like I said, I recommend that you limit your choice to two or three elements – fabric and material - so that you can understand how it changes.