Text

the storytelling in severance season two so far is reminding me somewhat of farscape season three. both use a scifi conceit to literally split characters into different selves, and thereby explore their competing desires, particularly with regards to romance, and selfhood by extension.

(spoilers for both)

in farscape season three the protagonist is split into two equal selves. one of the john crichtons is able to resolve two seasons of romantic tension, and be in a happy relationship with his alien love interest. meanwhile the other john, bereft of love, obsessively attempts to perfect the technology that will take him home to earth. metaphorically, it’s a conflict between two versions of home, or selfhood. a self that is familiar, versus one that is alien. john yearns for a version of himself that can have it all: earth and aeryn, past and future, known and unknown. but the myth that underlies the season is icarus, and the folktale is the dog with with two bones. one of the johns does seem like he will get it all, and will even be healed of the scifi-metaphor for pain and trauma that haunts his brain—the neural chip harvey. but it turns out that this perfect resolution is impossible. the john that tries to have it all dies; the john that remains as the show’s main character is the john that has nothing. it turns out that it is not possible to simultaneously change and not change. “you can’t go home again,” essentially. if john is to truly move forward, according to the show, he must confront the reality of loss that is inherent to becoming something new, regardless of whether that new thing involves beauty and wonder (love) or something terrible (pain).

similarly in severance season two so far you have one version of mark who has spiraled downwards without love. and who, as of the most recent episode (2x03 “who is alive?”), is willing to risk himself to get that past love back. this is contrasted with a version of mark who “has everything.” he is not shattered by grief, he has a new love interest, he still has some innocence. like the johns, one mark is obsessively fixated on a former state, and one is able to narratively advance. but the fact that the story of how good the more innocent version of mark has it comes from lumon (“the mark i’ve come to know at lumon is happy”) emphasizes how much it is, indeed, a story. that version has also experienced loss, and suffering, and his existence is, of course, literal corporate slavery. it potentially foreshadows that now that one mark is attempting to “have everything” to an even greater degree, by stitching together his separate selves, that something will go wrong. like farscape with icarus, there are two myths suggested by the show so far: the orpheus and eurydice myth, which doesn’t bode well, and the persephone myth, which could go in a number of directions.

both shows use the season’s credit sequence to express the idea of self-conflict. in farscape, the narration over the season three credits is split into two echoing voices, and its description of the show’s premise becomes divided and confused. instead of john saying he’s “just trying to find a way home”, and to meanwhile “share the wonders i’ve seen” as he does in the credits for seasons one and two, john in the season three narration wonders if he wonder if he should “open the door” to earth, or leave it shut. he starts asking questions: “are you ready?”, “or should i stay?” he starts describing the things he’s seen as both “nightmares” and “wonders”. similarly the credits for season two of severance are full of duality and conflict. there is imagery of gemma on one side, and helly on another. the women flicker and run in opposite directions. meanwhile the two marks simultaneously work together and seem at odds. sometimes one mark pulls and carries the other. but instead of the season two credits ending with the two marks merging, as they do in the first season credits, one mark now attempts to crawl its way out of the other.

in general, both shows seem to use the idea of pain, grief, or trauma as a kind of psychological splitting point. and use romantic love to make the longing and loss (the positive and negative) involved in change more visceral. in mark’s case, the metaphor is pretty literal and immediate—the starting premise of the show is that he has split himself into two consciences because of grief for his wife. in john’s case, the metaphor takes a bit longer to develop. he changes in increasingly dark ways over the course of the first two seasons, and only by season three is it time to physically split him in order to explore the implications of those changes. this difference makes sense based on the type of story that each show is derived from. severance is more of a modern gothic tale, exploring the consequences of repression in an eerie atmosphere. farscape on the other hand, is more of a modern odyssey or wizard of oz, a mythological tale of displacement and change.

i don’t have predictions on specific developments in severance, but i’m interested to see where it goes with the metaphorical framework it’s set up so far. like farscape, it could easily end in a dog with two bones sort of way—by trying to have two contradictory things, mark loses both. and perhaps that will be a necessary nadir on the path to some ultimate stage of resolution. regardless, it’s nice to see a new scifi show making use of the genre’s ability for metaphor in a way that doesn’t (yet) feel boring or underdeveloped, whatever it chooses to do with it.

#posts: art#severance#farscape#this needed another meta level but c'est la vie#the meta the enemy of the object sometimes

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

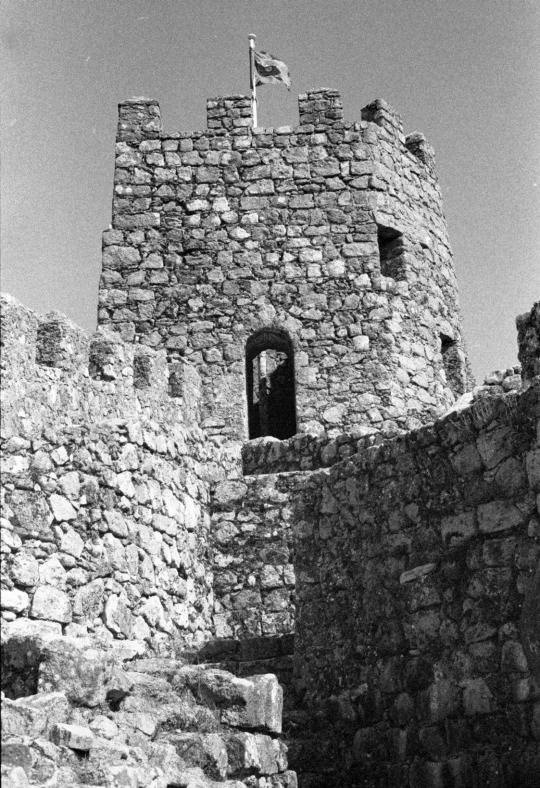

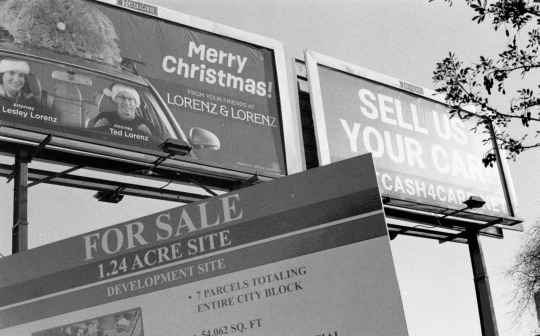

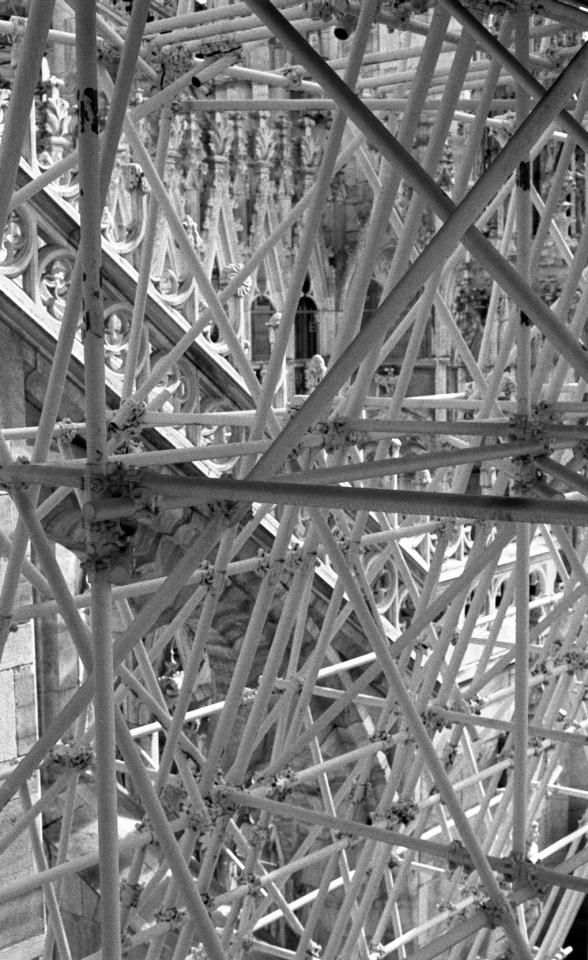

some of my black and white photography from the last couple years. locations: austin (tx, usa), boulder (co, usa), lisbon (portugal), sintra (portugal), milan (italy) .

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

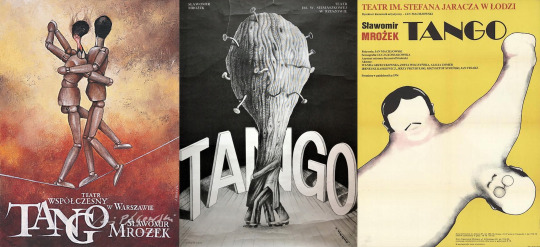

Translating ‘Tango’

This post will be an explanation of how I went about translating the 1999 performance of Sławomir Mrożek’s Tango without a personal knowledge of Polish—at the time I started, anyway—as well as a discussion of the translation philosophy I found myself adopting. For more context on the project and the play, see my original post [link]. This post contains spoilers for the play, though not immense ones. It’s fun to see the play blind, but you can read this without watching it.

Put simply, my approach was to use a variety of sources—both human and machine—in order to understand the “literal” meaning of the original text. From there, I would then hunt down more nuanced and idiomatic meaning. And finally, compose my own version. Scene by scene, here’s how it went:

1. Play the scene on youtube with the automatic transcription turned on and compare it against the script. One round comparing the Polish automatic transcription against the Polish script. One round comparing the automatically translated transcription against an automatically translated copy of the script. This gave me a basic idea of what was being said and if it differed from the script. The automatic transcription is far from perfect though. I would catch any more subtle differences as I worked, and as part of the editing process.

2. Run the scene’s corresponding pages through both Google Translate and DeepL. I tried a few different machine translation sites, but those two were the most reliable. They tended to have usefully different but similarly (in)accurate translations. That said, using any more than two had quickly diminishing returns, so I stuck with just those.

3. Compare the automatic translations against the two existing book translations. These are: the 1968 translation by Ralph Manheim and Teresa Dzieduscycka and the other 1968 translation by Nicholas Bethell and Tom Stoppard. Look for discrepancies. Look for idioms. Look for tone.

4. If any confusion arises, research. This meant a lot of googling of Polish grammar and idioms. I was lucky that, having studied a few other languages in the past, I had a sense of what threads to pull on. I’d watched a bunch of other Polish media recently, and read a lot of Russian literature (Russian and Polish are both Slavic etc), and that all helped point me in the right direction too. Since I didn’t know any native speakers, and didn’t have the money to pay one to be on-call, then if all other forms of research failed, I’d ask ChatGPT questions. It was useful for getting me unstuck, though limited in that I couldn’t trust its accuracy. If, at the end of this process, I was still unsure about something, I flagged it to have a human editor check later.

I wasn’t just researching basic meaning of course, I was also researching tone. What words sound familiar, crass, formal, academic, or simply strange? This is a play in which characters say a lot of strange things, and it was important to keep track of whether something sounded strange to me because it was supposed to be strange, or simply because I didn’t understand it.

I was also researching literary context. In Act III, for example, Artur insults his uncle Eugeniusz by calling him “you whitened/whitewashed corpse.” There were many possible translations of this. The Manheim translation translated it as “you whited skeleton” and the Bethell translated it as “you whited sepulchre.” I at first considered translating it as “you bleached pile of bones”, as I thought that might be the intended image, or “you bloodless corpse” if the important part of the image was not just one of death, but of lacking vigor specifically. However, neither insult seemed quite right because all of the other insults in Artur’s list emphasize Eugeniusz’s falseness and hypocrisy. In addition to a “whitened corpse”, he calls Eugeniusz a “stuffed nothing”, an “artificial organism” and a “rotting prosthesis.” Not having a Christian background, I didn’t realize at first that this was a probable Biblical reference. Research, however, pointed me to the scene in which Jesus insults the Pharisees by calling them hypocrites.

From the King James Bible: “Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye are like unto whited sepulchers, which indeed appear beautiful outwardly, but are within full of dead men’s bones and of all uncleanness.” [link]

I then checked whether a Polish bible that predated Tango also used a version of “pobielany” for “whited” or “whitewashed.” This was the case.

From the Gdańsk Bible: “Biada wam, nauczeni w Piśmie i Faryzeuszowie obłudni! iżeście podobni grobom pobielanym, które się zdadzą z wierzchu być cudne, ale wewnątrz pełne są kości umarłych i wszelakiej nieczystości.” [link]

The reference seemed highly plausible, especially considering Poland’s Christian culture, and Artur’s obvious Christ-like savior complex throughout Act III. So either “whited” or “whitewashed”—both are used in different English versions—seemed the word to use. I landed on “whitewashed corpse” as the total phrase. I didn’t like Manheim’s “skeleton” as skeletons are already white; what is gained by whitewashing one? And I didn’t like Bethell’s “sepulchre” either, as it makes the Biblical reference more direct than it is in the original. The idea of a fleshy corpse painted over with whitewash is exactly as grotesque as Mrożek’s original is. By keeping the word “corpse” I kept that image, and by using the more modern “whitewash” I kept the Biblical reference while being more evocative to a modern audience.

5. Examine the Polish original for style. Is there rhyme or repetition? Is there a phrase or word choice in Act I that gets echoed in Act III? If so, try to replicate. For example, in Act I Artur complains that Grandma Eugenia “przekracza granice”, or “crosses boundaries”. Later in Act III, Stomil declares that “there’s a limit”, to which Artur replies, basically: “Limits can be overcome. Didn’t you teach me that?”. Both exchanges use the word “granice” for a limit or boundary. All four of my sources varied in what word they used for “granice” during those two scenes. However, I decided that since the original uses just one word, I should as well. This would ensure that the connections between the scenes were as obvious—and reflective of the original—as possible. Since the word “line” is the most flexible, that’s what I used. Thus the dialogue became:

ARTUR: Grandma crossed the line. ELEONORA: What line? ARTUR: She knows what she did.

and

STOMIL: Then I forbid you! There’s a line. ARTUR: Lines can be crossed. Didn’t you teach me that?

6. Examine the line delivery in the video. Do the actors put emphasis in a certain place? Is there a long pause in the middle of a phrase? If so, arrange the sentence to reflect that delivery if at all possible. For example, towards the end of the play, Edek warns the family that they don’t need to worry about him taking over as long as they obey him. Most of the four sources put the concept of obedience at the end of the sentence, like so:

Bethell & Stoppard:

EDEK: I like a laugh, a bit of fun. Only I’ve got to have obedience.

Manheim & Dzieduscycka:

EDEK: I like a joke, like a good time. But get this: There’s got to be order.

Google Translate:

EDEK: I can joke and I like to have fun. There must only be obedience.

DeepL put it at the beginning, but it looked unnatural:

EDEK: And I can joke, and have fun I like. Only obedience must be.

However, the Polish original is closest to “Only obedience must be” and the actor that plays Edek delivers the line with a long, sinister pause between “Only obedience…” and “…must be.” Therefore, I wanted a phrase that started with the concept of “obedience” and ended with the concept of “must be”, but in a way that sounded more natural than what DeepL managed. Which is how I landed on:

EDEK: I like a joke. I like a good time. But obedience…is mandatory.

Speaking of style, I also decided to start both the “joke” and “good time” sentences with “I like” in order to give a sense of insistent repetition that exists in the original, even though the original doesn’t repeat “I like”. The original, as you can see from the DeepL version, starts each phrase with “And”, but that construct sounds weird in English in context. I also used “a joke” rather than “a laugh” or some other word because, as the automatic translations indicate, the word Edek uses (“pożartować”) contains the word for joke (“zarty”). And the play used the word “zarty” before when talking about how “The joke is over” and “[Stomil] has been joking for 50 years.”

(This is also a good example of why two different machine translations were useful. The Google Translate version of the line is a smoother translation. But the awkwardness of the DeepL version helped me understand the structure of the original. Meanwhile the human translations didn’t provide extra meaning, but did validate the accuracy of the machine translation, and gave me some stylistic ideas. Using “obedience is mandatory” came at the cost of using language that ideally would have been more casual—“I’ve got”/“There’s got”—as Edek tends to speak in a less refined way. In this case, it was a good stylistic idea, but one which I couldn’t use.)

On the other hand, sometimes I decided that arranging a sentence in a certain way wasn’t worth it. For example, in Act I, Eugeniusz petulantly snitches to Artur that “Edek ate the sugar.” However, the line as delivered in Polish is more like “The sugar was eaten by…Edek!” Because of this delivery, I considered translating it as “The sugar was because of…Edek!” But even though that sounded slightly more natural than “was eaten by”, it just didn’t look as petulantly funny as “Edek ate the sugar.” I decided that since the word “Edek” was recognizable, a viewer would be able to figure out how the line was delivered regardless of how I translated it. Therefore I kept the translation as “Edek ate the sugar” in order to convey the spirit of the underlying text, while trusting that the performance would speak for itself.

7. Once I’d given my translation my best-faith attempt, I paid an editor who spoke both languages to correct my Polish transcript and give feedback on my work (many many thanks to Maja Walczak). She helped me catch some subtle things I wouldn’t have caught on my own. For example, during the scene in which Edek is reading out his “principles” I had originally translated it as follows:

EDEK: Here it is. “I love you…and you’re asleep.” ALA: Anything else? EDEK: “It depends on the situation.” ALA: Oh come on, just read. EDEK: I was reading. That’s a principle.

“It depends on the situation” is an approximate translation of the Polish, which is “Zależy jak leży.” Without context, I assumed that the humor in the line just came from the fact that it was a bland, dismissive phrase that Ala wouldn’t recognize as a principle. That on its own is fairly funny, but not uproariously so. So I was surprised when the editor explained that this was actually a very well-known, very quotable exchange that people would reference and laugh about. She explained that the memorability comes from the fact that “Zależy jak leży” is short, simple, and most importantly—rhymes. I felt silly afterwards for not noticing that it rhymed. This turned out to be a clear case of how turning to existing translations for help rather than relying on personal fluency could lead my astray, because neither of the existing translations rhymed that line. Here’s what they had.

Bethell & Stoppard:

EDEK: Here we are. “My love is dead to the world.” ALA: What else? EDEK: No comment. ALA: Stop messing about—read. EDEK: I was reading—that’s a principle.

Manheim & Dzieduscycka:

EDEK: Here it is! “I love you, and you’re sound asleep.” ALA: That’s all? EDEK: “You made your bed, now lie in it.” ALA: Oh, come on, Eddie. Read. EDDIE: I did read. That’s a principle.

As you can see, both translations seemed to choose generically dismissive phrases, with no rhymes. The Manheim translation takes a stab at wit by using an idiom, which makes sense since—from what I could find—“Zależy jak leży” is also an idiom. But since I couldn’t think of an English idiom that meant “It depends”, I stuck with a version of the phrase “It depends” as that is a genuinely common English expression.” However, after the editor made her comment, I no longer felt beholden to such literalness. I ended up changing it to:

EDEK: Here it is. “I love you…and you’re asleep.” ALA: Anything else? EDEK: “Not today, go away.” ALA: Oh come on, just read. EDEK: I was reading. That’s a principle.

This new version manages to contain a short, funny rhyme that still conveys dismissiveness. And that made it a translation that felt truer to the spirit of the original, and that would ideally create more of the effect that the original creates in its target audience. Who know if it’s actually funnier or more quotable. But it was funnier to me.

Another example: At one point, Artur insults Ala, who has just cheated on him, by calling her “Ty kuro!” This translates literally as “You hen,” which is not something insulting, so I was a bit confused as to what it meant. The Manheim translation translated it as “You goose” while the Bethell translated it as “You whore.” Since the context and the actor’s intonation indicated he was giving a serious insult, I also chose at first to translate it as “You whore!” But the editor explained that “kuro” sounds a lot like an actually insulting word, “kurwo”, which can at times be translated as “whore.” The point of that line, therefore, is that he’s trying to insult Ala but can’t actually make himself say the insulting word—he is impotent and abstracted even in that moment. So I changed my translation to “You wh-horse!” This kept the idea that he was almost using the word “whore” but actually using an innocuous word for an animal.

*

When I started this project, I really wasn’t sure how much the translation would feel like “mine”. I assumed there was a good chance it would end up as some patchwork Frankenstein’s monster of my various sources, and if so, I intended to credit it as such. But as the process went on, I felt more and more ownership and authorship regarding my choices. This feeling increased as I came to understand the Polish better in my own right. It also increased the more I realized that I was bringing my own particular philosophy to bear when I made decisions.

I found myself thinking a lot about what matters in a translation of filmed dialogue, and how it differs from a text that is meant to be read or performed. As in all translation, movie translation requires making a tradeoff between loyalty and lyricism. As in all translation, one also has to decide how much of the character of the original language to preserve—the Polishness, Spanishness, Hindiness, etc—or to transmute into some cultural approximation in the target language. Different mediums also come along with different constraints. In the case of poetry, one might be constrained by rhyme or meter. In the case of drama, one might be constrained by whether or not a line will sound natural coming out of an actor’s mouth.

I noticed that there were choices I thought made sense for the script translations of Tango, but not for a filmed translation. For instance, both the Manheim and Bethell translations anglicize character names and remove diminutives. This is an understandable decision to make when translating a play that takes place in a neutral and ambiguous setting like Tango does. While there is a lot that is spiritually and contextually Polish about Tango, the specifics are not obviously Polish the way they are in something like Wesele ("The Wedding"). Wesele is another very famous Polish play, which is clearly set in the Poland of 1900 and is dense with Polish cultural references. Understandably, the English translation of Wesele by Noel Clark does not anglicize character names. But because Tango generalizes well, one may as well lean into that when composing a script that is meant to be performed by English-speaking actors for an English-speaking audience. If I was composing my own book version, I would strongly consider doing the same.

But filmed dialogue has not been generalized. The actors are delivering lines that are structured in a Polish way. They are saying Polish names and using Polish diminutives. An audience will be able to hear those names. And so, I tried to structure my translations in a way that would make use of what the actors were saying, and what an audience would be able to hear. I decided to leave in the Polish names and their diminutives—Artek, Arturek, Alunia, Edziu, etc. My experience from reading English translations of Russian novels is that while diminutives are a little confusing at first, one quickly gets used to it. Similarly, being familiar with Spanish, I couldn’t imagine English subtitles for something in Spanish turning say, “Pepito” into “Pepe” or “little Pepe.” It wouldn’t sound right. I figured I’d challenge people to understand at least one aspect of the actual Polish.

I placed a high priority on elucidating the acting. When translating dialogue for a dub, one wants the text to fit well with the film actor’s face (or animated character’s face), but half of the acting ends up being given to the voice actor doing the dub. The voice actor will elucidate the translation and film acting in their own way. But in the case of subtitles, the original actor is still doing all of the acting. They’re adding particular tones to particular words, and reacting in certain ways to the words that other characters say. Therefore, it was important to me to preserve as much of the nuance of those choices as possible. So I made an effort to translate everything the characters say—not to generalize at any point. It mattered to me to even translate filler words, since someone who doesn’t speak the language has no way of knowing if something that sounds like “uh” or “um” is actually an “uh” or “um” or a legitimate word. As I mentioned earlier, I also made an effort to structure sentences in English in a way that matched the Polish structure whenever possible. I put periods and commas where the actors paused, not just based on what might look correct on a page. If a Polish word sounded like an English word and meant the same thing, I tried to keep that word, and put it in the same place in the English sentence. Good acting will always speak for itself to some extent, and this performance is full of good acting. But it’s also a missed opportunity, even an insult, to not help clarify the choices that acting is made of—especially when it’s good.

In general, I was excited by how well subtitling a (good) performance of a play in its original language could provide access to the original spirit of that play. A different sort of access than reading or seeing a performance of the existing English translations. In a book translation of a script, it’s easy to justify taking liberties with the text. After all, some phrasings just sound better in English, right? And then once actors perform that text with its liberties, it’s another round in the game of telephone. When I first decided to make some subtitles for this Tango, I didn’t intend to translate it myself. I bought the Manheim translation, and figured I would just copy and paste it into subtitles, note the authorship at the beginning and end, and call it day. But it became immediately apparent that the translation would never work for subtitles, because the sentences were not arranged in a Polish way, were shorter or longer than in the Polish, and even occasionally cut, added, or mutated entire phrases from the original. The translation had mostly not changed the overall meaning of anything, but it didn’t match what was being performed in Polish. By virtue of needing (or choosing) to be loyal to the text as performed, I found myself being careful and precise in way in a way I wouldn’t necessarily have been otherwise. There was no room for wordiness, because the line deliveries didn’t allow it. I couldn’t add or delete things out of poetic license, because it would have been confusing when combined with what was on screen. Instead, I had to make things sound natural and poetic within the constraint of how long and in what way an actor was speaking.

The result, I think, is that it’s much clearer why this is considered a good play in its original context. You can read the existing English translations and understand just fine what the play is about. But there is a certain flab around that meaning. The script translations lose some of the joy in the biting precision of Mrożek’s wordplay, and the urgency and momentum of the dialogue. A performance in the original preserves that clarity, and a translation of a performance is (ideally) more likely to preserve that clarity along with it. This principle can be extended to various other aspects of the original, not just wordplay. Preserving diminutives, for example, adds shades to the way the characters interact that would be otherwise missing in an English performance.

In practice, of course, published translations tend to be executed with more care than subtitles. It’s rare that anyone in the English-speaking world talks about the translations of movies or TV shows, let alone filmed plays, with the same literary attention that is given to novels or poetry. I’ve long thought this was a mistake, as filmed dialogue can be as rich with meaning as any other kind of artistic use of language. If someone would publish a new translation of the book of a play, why not a new translation of a performance of it? Or of a movie? They all contain literary intent. And now that I’ve put my money where my mouth is, this seems even more obviously true than it did before. We’re missing out on experiencing art in new ways—both the original art, and the art of translation—by not treated filmed dialogue with the literary seriousness it deserves.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theory, Reality, and 'Tango'

Happy to share a project I’ve been working on for the last few months. Around July, I happened upon a TV staging of the Polish play Tango by Sławomir Mrożek. Written in 1964, Tango is a classic of the mid-century Theater of the Absurd, as well as Polish avant-garde drama. It’s a highly famous play in Poland—a staple of high school curricula—but less well-known in the anglosphere these days. I enjoyed the staging a lot, and because it had no English subtitles, I thought I’d try to make some myself. This was a particularly fun project given that, as far as I know, the play hasn’t had a new English translation since 1968 [1]. I’ll use another post to talk a bit more about the translation process and the philosophy of translation that I found myself adopting—particularly how it differed from the philosophy I might have adopted if I was translating the play in book form, rather than a performance of it.

But for the moment, the long and short is that you can now watch Tango with my English translation on Youtube here. If you have a VPN (or are located in Poland), you can also watch on the Polish TVN website in better quality using a subtitle extension like Movie Subtitles or Substital. All subtitle files can be downloaded here.

youtube

As for the play. Tango takes place in a middle-class home of the 1960’s, and the drama centers on the dynamics between three generations of a single family. In Tango’s version of the world, permissiveness has won a complete cultural victory. Victorian traditionalism was overturned by the rebels and artists of the 1920’s, and all social values and conventions have since disappeared. Fed up with his family’s chaotic household, 25-year-old Artur, a member of the youngest generation, longs for his own form of rebellion. But with no conventions left to overthrow, the only rebellion remaining for Artur is rules and traditions. He attempts to instill order and re-impose tradition by force, but (avoiding specifics) it doesn’t go according to plan. In the end, no form of idealism wins in Tango. Not traditionalism, anti-traditionalism, or anti-anti-traditionalism. Instead, idealism ends up hollowed out and puppeted by those who are unscrupulous and willing to use violence to get what they want.

Tango struck me first because it was funny, and witty, and thematically felt startlingly relevant to the present day. This particular performance from 1999 that I’ve chosen to subtitle also struck me for being remarkably well-acted and well-staged. It’s tough to make absurdism feel emotionally genuine enough to have a dramatic effect, instead of descending into shallow pantomime and parody, and this rendition of Tango by director Maciej Englert pulls it off very well. The cast is comprised of some of Poland’s greatest stage actors of that time, and it shows.

But the play also made an impression on me because it seemed to be an unusual hybrid of theatrical modes, both in general and in the context of the Theater of the Absurd. Theater of the Absurd is often talked about as having a Western and an Eastern incarnation [2]. In the West, absurdism was considered existential and apolitical, while in the East—ie, in countries under Soviet control—absurdism was used to discuss ideas that were not safe to discuss directly. In reality, of course, this supposed division was not nearly so clear-cut. Especially since “Theater of the Absurd” wasn’t any kind of coherent artistic movement to begin with, but more of a general aesthetic trend [3]. Plenty of works that came out of the Western Theater of the Absurd had political attitudes, or at the very least observed dynamics with political implications [4]. And plenty of works that came out of the East depicted dynamics that resonated with people beyond those who lived within the Soviet bloc. This duality is especially alive in Tango, which is one of the reasons I found it such a fun and tricky play to pin down. On the one hand, one can read it as an allegory for, or commentary on, many specific things related to 19th and 20th century Polish history. On the other hand, the play’s ideas are also broad enough that it ends up feeling relevant to any number of cultures, eras, and situations.

This ink-blot quality is one of the reasons for the play’s lasting appeal. For example, how to read the collapse of values at the beginning of the play? Perhaps the social permissiveness refers to the actual liberalism of the 1920’s, and the failures of the intelligentsia that facilitated the Nazi takeover of Poland in the 1940’s. Or perhaps it refers to the destruction of decency and normalcy in the midst of war and occupation [5]. Or it refers to life on the shifting sands of Soviet dialectics, the struggle to create real meaning out of something that claims to be progressive, yet feels inherently insubstantial. Or it refers to a more general secular, postmodern condition. If values are arbitrary and self-created, then how does one choose what values to create? One reviewer of this staging observed how the impression Tango made had changed since 1964: "Artur's hysteria meant something different in the Polish People's Republic, a land of ideologues without ideals, than it does today. Searching for values at random was a mockery then—today it is perhaps one of the most moving scenes in the play.”

(See also Martin Esslin in The Theater of the Absurd: “When Tango was first performed in Warsaw in 1964 it understandably produced a violent reaction: the audience interpreted the play’s message as a sardonic comment on Stalinism and its totalitarian structure of terror. But the play made an equally strong impact in Western Germany and other countries of non-Communist Europe…[T]he growth of arbitrary bureaucratic power, the erosion of political ideals and the consequent pursuit of power for its own sake by otherwise undistinguishable parties, led by crude, uncultured careerists, might also, after all, turn out to be a feature of…‘advanced’ Western societies.”)

All this said. I don’t think Tango is simply somehow “accidentally” about ideas that can be interpreted as being about something other than Poland’s immediate travails. Arguably, the duality exists in the text itself. The play is about Poland and Europe [6], it is in conversation with other Polish drama about Poland (Wesele, Dziady), as well as Polish absurdism (Witkacy, Gombrowicz). And it is also about things like values, and power, and art writ large, and is in conversation with Beckett, Ionesco, Chekhov, Shakespeare, and others. Specificity and universality feed each other—this is nothing new in art.

If anything, the tension between the specific and the universal seems like one of the biggest features of the play. Tango is a war between idea and reality, the abstract and the concrete. And this is another way in which it’s an unusual theatrical hybrid. You might even call it a theatrical identity crisis.

Broad history: Prior to the 19th century, Western theater did not tend to be realistic in the modern sense of it. Instead it was characterized by symbolism, exaggeration, and verse. Greek plays, opera, Shakespeare, Molière. Such theater could be subtle and true, but it did not generally aim for trompe l’oeil mimicry of real life, or have much interest in “regular” people and everyday events. Then after a 19th and 20th century turn towards realism (Chekhov, Ibsen, Shaw, etc), the Theater of the Absurd introduced a new and defiant kind of abstraction. In absurdist plays there might be internal, if absurd, logic, but the settings, characters and narratives tend to have only a limited amount of naturalism. Images are symbolic, language is Aesopian, and events take place in dreamy, generalized settings rather than a particular time and place. To the extent that absurdist plays use the concrete or naturalistic, it’s usually to immediately subvert it. Eugène Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano, for instance, blares the Englishness of the characters and the setting, but in a way that is obviously nonsensical, and comedic (or horrific) precisely because it has only a superficial correspondence to the England of real life:

MRS. SMITH: There, it’s nine o’clock. We’ve drunk the soup, and eaten the fish and chips, and the English salad. The children have drunk English water. We’ve eaten well this evening. That’s because we live in the suburbs of London and because our name is Smith. [7]

Or The Lesson, another Ionesco, starts out in a naturalistically appointed room, with what could be naturalistic characters, but within two pages begins a jarring descent into blatant absurdity. Theater of the Absurd doesn’t just do away with realism, either. It also does away with the conventional narrative structures of both realistic and earlier, less-realistic theater. Various works in the Theater of the Absurd were called anti-theater for this reason. Instead of having a typical beginning, middle, and end, or problem-escalation-resolution, absurdist plays are often circular and unresolved. Vladimir and Estragon start Waiting for Godot waiting, and they finish it waiting. The endings of The Bald Soprano and The Lesson repeat their beginnings, like a mirror reflected in a mirror. Absurdity arises from the inescapable, Sisyphean nature of existential dilemmas, and this ends up reflected in the most basic structures of absurdist theater.

Compared to such plays, Tango makes a surprising amount of sense [8]. It has a beginning, middle, and end. It is not set in the real world, but it is set in “a” real world, with a vague but coherent history. The characters don’t speak like real people exactly, but they do have consistent motivations and personalities. They’re not anti-characters like the Smiths and Martins in The Bald Soprano. The play also contains various gestures towards naturalism. The idea of a play about regular people who live in a regular apartment, is taken straight from the realistic tradition. The stage instructions are detailed, insisting upon a set cluttered with specific items, with characters in specific clothes, all of which are taken from real life. Here’s an example from the beginning of Act III:

We see before us a conventional, bourgeois living room from half a century ago. The confusion, blurriness, and lack of contours are gone. The draperies, which had previously been strewn about—half-lying and half-hanging—giving the stage random folds and making it look like a rumpled bed, are now in their places and have become proper, regular draperies. The catafalque remains in the same place…but is now covered with napkins and trinkets, like an ordinary sideboard.

For a key moment of violence, Mrożek even makes a point of saying that the execution must be naturalistic:

Attention! This scene must be very realistic. Both blows must be performed in such a way that their theatrical fiction is not obvious. Have the revolver be made of rubber, or even feathers, or have [the actor] wear some kind of pad under [their] collar. It doesn't matter, as long as it doesn't look ‘theatrical’.

Tango also “makes sense” in that it (seemingly) contains the comprehensible allegory and symbolism of more conventional theater. Each of the characters could potentially be read as a representative of a different generation or some piece of the social fabric, much like the characters in Stanisław Wyspiański’s Wesele [9]. You can read grand-uncle Eugeniusz as the avatar of traditionalism—a class that supposedly cared about values, but in practice turned out to be craven and opportunistic. Or Artur’s father Stomil as the aging, ineffectual avant-garde. Or Artur’s cousin and fiancée Ala as “the people”, torn between Artur’s flavor of bullying idealism, and the vacant brutality of the family’s boorish houseguest Edek.

Yet in spite of all of this “sense”, the play is undeniably absurdist, full of the kind of seeming nonsense typical of other absurdist theater. Artur punishes Eugeniusz by putting a birdcage on his head, or makes his grandmother lie on a catafalque. There are illogical exchanges like the following:

ARTUR: Will you be staying with us for long? ALA: I don’t know. I told my mother I might not come back. ARTUR: What did she say? ALA: Nothing. She wasn’t at home.

And in general, the events of the play progress in an absurd fashion. There’s no logical reason that Artur’s schemes for his family could actually change the social structure of the world. Supposedly serious things like murder and repression are casually and comedically invoked (until they aren’t).

ARTUR: You know what, Father? Why don’t we try [killing Edek] after all? There’s no risk. At worst, you’ll shoot him. STOMIL: You think so?

In other words, Tango references and evokes, in both form and content, the last few hundred years of Western theater. The cultural call-and-response of tradition, rebellion, and counter-reformation that it depicts parallels the artistic call-and-response of traditional theater, realism, and absurdism. It is bogged down by theatrical history much as Artur is bogged down by social history. Or as the family's apartment is bogged down by material history:

This table, even more than the interior as a whole, gives the impression of confusion, randomness and sloppiness. Each plate, each item, comes from a different service, from a different era and is in a different style.

There’s a certain confusion and chaos surrounding what kind of play this is supposed to be. Should a playwright comment on a social situation, express a human condition, or experiment with form? What kind of play is good for art? Good for people? Good in general? Tango features outright mockery of empty avant-garde theater, and an interesting ambivalence about symbolism. On the one hand, the play clearly uses symbolism. On the other hand, it was written in a context in which symbolism and indirectness were required in order for it to be performed in its original language behind the Iron Curtain.

Throughout the play, the characters debate the value of “form”, “reality” and “idea”, and how and whether to either achieve or integrate or discard them. It is the age-old debate, in both society and art, of how to balance theory with reality, truth with artifice. But–just as in history–none of the characters can resolve the debate, and most are hypocrites about their positions. The characters crave and fear reality in equal measure. Stomil, who makes impotent experimental theater, champions the idea of going “beyond form”--ie, going beyond things like rules and abstractions. He denounces the rule-loving Artur as a “vulgar formalist” and celebrates Edek for his “authenticity.” But for all that Stomil claims that his art is trying to achieve some sort of grand concreteness, his creations and explanations are all highly inaccessible and theoretical (after shocking his audience by setting off a gun: “By direct action–we create unity between the moment of action and perception”). And he admits that he doesn’t actually like Edek, who is sleeping with his wife Eleonora (“I’ve had my eye on that scoundrel for a long time. You don’t know how much I’d love to finish him off.”). Meanwhile Artur claims to want a return to order and tradition, but he also wants to rebel–something inherently destabilizing.

STOMIL: What do you want exactly, tradition? ARTUR: World order! STOMIL: Is that all? ARTUR: And the right to rebel.

And when he tries to follow through with his plans he finds the results hollow and unsatisfying. He finds that reality erodes principle, and yet principles that are not animated by an idea, that is in turn animated by reality, lack vitality and endurance. He strives for “a system in which rebellion is one with order, and nothingness with existence” that “will transcend contradictions entirely!” Much like Stomil with his theatrical gunshot, Artur thinks he can conquer such contradictions by wielding force–something seemingly fundamentally “real”. But in the end, his talent turns out to mainly be in exalting the concept of force, rather than actually embodying it.

Meanwhile Eugeniusz supposedly wants a return to propriety. Not so much order, like Artur, but an appearance of moral rectitude, the rituals of civilization (“Start a family. Brush your teeth. Eat with a fork and knife! Make the world sit up straight again instead of slouching.”). He detests Edek’s “filth” and the “degradation” of the rest of the family. Yet for all his love of the forms of properness, no one is more willing to lower himself than Eugeniusz. He is quick to abandon his supposed principles and attach himself to whoever has power.

This sense of contradiction and call-and-response between theory and reality is even echoed in the structure of the play. The first act starts out as more absurdistly symbolist–the characters play rhyming card games, Artur metes out his birdcage and catafalque punishments, Ala turns out to have been hidden under a table the whole time, Stomil puts on a play about Adam and Eve. Then the second act becomes more naturalistic, with long one-on-one, interpersonal conversations that contain more conventional dramatic stakes. And finally the third act combines both modes. The third act is full of both abstract ideas and images–the family in their tight old-fashioned clothes, Artur’s quest for a unifying philosophy–and regular human drama related to marriage and infidelity. Until it finally ends in a moment of violent naturalism, in the form of that realistic blow (“Attention! This scene must be very realistic.”).

Taken as a whole, Tango follows the pattern and tenor of dialectical debate, with satirical circularity. Soviet dialectics promised a means of navigating and resolving contradictions. It promised a means of understanding the cycles of history, and existing in the correct moral relation to them. Add more context, add more cleverness, and the cycles are no longer confusing. You can win them. In practice though, this version of dialectics often merely acted as an elaborate justification for otherwise unjustifiable political ends [10]. But unlike in a dialectical debate, Tango makes the crude, concrete conclusions explicit. The winner of Tango is not a dialectician. The winner is violent reality, simply wearing philosophy’s jacket.

What Maciej Englert’s staging understands, and one of the reasons it had such an effect on me, is the real human feeling that suffuses the play. Artur’s confusion and distress are real. As is Stomil’s frustrated impotence, Ala’s love, or even Eugenia’s fear and irritation. The cozy, chaotic naturalism of the set (taken straight from the script directions) emphasizes this human scale. Tango is not simply a detached satire of Stalinism, “some abstract hypothesis, a play on words, a product of intellectual imagination.” It is about the tension between the human and everything more than human–and in order for that tension to work, the human aspect needs to be just as apparent as the abstract aspect. To paraphrase a good review, Artur in this production is both scary and pitiful, human and symbol. Eleonora seems at first a caricature, but “becomes unexpectedly moving in the scene in which she talks humanly, without a mask, to Ala.” While Ala is full of “the truth of unhappy feelings...the cynicism that usually dominates this role in other stagings is put in quotation marks; [she] only pretends to be nonchalant towards life.” And this is also why it is all the more crushing when both the human and the abstract turn out to have been paving the way for something worse, something they both lose out to.

*

Theater of Absurd appeals to me at the moment. It feels relevant. To the world, to my life. And the way Tango combines the Western and Eastern forms of the absurd gets at why. In the “Eastern” form, absurdism springs from a breakdown of logical reasoning that is imposed by external forces: war, authoritarian whim. Hence plays like Julius Hay’s The Horse, which tells the story of Caligula appointing his horse Incitatus to the Roman Senate, leading the population to start acting like horses. Or Václav Havel’s The Memorandum, in which bureaucratic characters are forced to communicate in an overly-rational neo-language that none of them can understand. In the “Western” form, absurdism springs from a more existential, post-modern breakdown of logical reasoning: how is one to make sense of existence if there is no objective logic? If all of the former institutions of meaning–religion, government, class, materialism, and so on–are meaningless, then what is left? And just as in Tango, it often feels today as if those two forms of absurdity have combined. If they were ever even separate.

No, of course I do not live under a totalitarian state, in the present-day West. I do not worry about gulags or famine or being hauled off in the night for saying the wrong thing. But there is a sense of institutional decay, and a sense of pretending otherwise about this. A sense that important details of my life are determined by obscure power struggles between people who are incompetent or ill-intentioned, or both. A sense of people going insane, and feeling proud of it all the while. A sense of nihilistic chaos lurking at the door, and people saying “Would it be so bad to let it in?” Meanwhile the internet accelerates countless forms of absurdity. It instills a surveillance mindset. It destroys old forms of reverence, and creates new, bizarre ones. Now you can see the most pathetic aspects of politicians and artists and intellectuals laid open on social media. Now you can see regular people turn themselves into grifters, beggars, and compulsive performers. It would almost be more dignified if people did this due to explicit government repression, or out of purely mercenary ambition. Instead of out of a more basic human, animal sense of precarity. Am I important? Am I safe? Do I have enough? Do I belong? Do you like me? Do you like me? Do you like me?

Former markers of respectability are losing their meaning. Respectability itself is losing meaning. And quite possibly these things deserve to be destroyed, perhaps this is just normal cultural turnover, but it’s not yet clear what is waiting to grow out of the rubble. For a while, maybe a decade, there was a swing towards authenticity. Fetishistic authenticity usually, but authenticity nonetheless. Hipster natural material aesthetics–being into leather, wood, iron, pickling. Relatability, parasociality, confession. This all still exists to some degree, but has lost much of its awkward earnestness, some genuine desire to be post-ironic, some kind of novelty. The fakery of amateurism rather than cynicism. Now fakery and authenticity are so intertwined it starts to feel like both have lost their meaning. Performance and entertainment are endemic, except they’ve never felt less like entertainment, or more like narcotics. Performance gains its power from its tension with truth, reality. Without reality, performance is impotent. And yet it’s never been more important. Absurd.

The internet simultaneously creates an unprecedented awareness of reality, and an unprecedented detachment from it. There have long been ways in which one could be awash in information and entertainment from waking until sleep. Television, books. There have been means of stupefaction for even longer. Intoxicants of all kinds. But the internet is more than just a stream of information in which people can lie down, open their jaws, and passively drink. It is interactive, frequently intensely so. The information, unlike in a book, is often related to what is happening right now. And unlike in a paper or on the news, the information is often delivered by people in one’s social circle. Suddenly one is aware of a thousand different things, horrible and otherwise, and not only that, the awareness comes along with the opportunity for action–money, publicity, simple acknowledgement–and hundreds of people one knows can see that action. You can live your life in a holodeck world. Yet down the line, reality keeps being real, and is affected by that holodeck world–mortally and trivially. These are not new observations really. Still, that combination of interactivity, intensity and detachment turns “reality” into something that is both omnipresent and intangible. Absurd.

It’s always been absurd. “Reality” has always been both obvious and ineffable, something to philosophically struggle with. “Truth” has always been difficult to grasp, and difficult to represent. Map and territory, forever locked in combat. But just as circumstances made this fundamental absurdity feel closer to the surface in the mid-20th century, so does it feel closer now. Theater of the Absurd arrived on the heels of decades of talk of perfectibility. Nazi perfectibility, Soviet perfectibility, even the perfectibility of the liberal, capitalist order. Promises of surmounting the lesser aspects of humanity. Purge or plan society in the right way, and you’ll be on the way to becoming better than human. Yet time and again, those lesser aspects had a way of revealing and reasserting themselves. Murder, cruelty, exploitation. Pettiness, cowardice, selfishness. All of these things, it turned out, could thrive regardless (or because) of a system’s stated ideals. And perhaps we’re in another phase of finding out that the latest means of elevating humanity is simply enabling new and twisted manifestations of the same old problems.

Idealism loses many times over in Tango. And each time it deserves to. The traditionalists repress, the rebels create listless chaos, and Artur’s anti-rebellion leads to repression once again, but this time with even less meaning behind it. Yet when crudeness without idealism–reality without idea–wins, it’s even more horrifying. So what’s the answer? Is there an escape? Will Godot ever appear?

Tango proposes the pessimistic view. Yes, the endless generational cycles of rebellion and counter-rebellion can end. The search for meaning and selfhood can end. History can end–in nightmare. Perhaps that’s not a productive view to live by. Certainly one could write an entire other essay about the persistence of human virtue. But sometimes it is a view that is worth inhabiting for a while.

*

[1] And because, it must be said, I did not know Polish at the time I started the project. The two previous translations were both written in 1968. One is by Ralph Manheim and Teresa Dzieduscycka, published by Grove Press. It can still be found in print as part of The Mrożek Reader, or used. The other translation is by Nicholas Bethell and Tom Stoppard. It is not in print that I know of. I was able to find it used in the collection Three East European Plays. Both translations have their strengths and weaknesses. Overall though, I wasn’t a huge fan of either one. They each do the job in their own way, but I also found them to be a bit wordy in a way that blunted the tight, biting quality of the humor of the original. If I had to choose, I would lean towards the Bethell and Stoppard translation for reading and the Manheim and Dzieduscycka translation for performing.

[2] See Marketa Goetz Stankiewicz in “Slawomir Mrozek: Two Forms of the Absurd” for a good discussion of this. Both as it applies to Theater of the Absurd generally, and to Mrożek specifically. [jstor] [scribd]

[3] From Martin Esslin’s introduction to The Theater of the Absurd:

It must be stressed, however, that the dramatists whose work is here discussed do not form part of any self-proclaimed or self-conscious school or movement. On the contrary, each of the writers in question is an individual who regards himself as a lone outsider, cut off and isolated in his private world. Each has his own personal approach to both subject-matter and form; his own roots, sources, and background. If they also, very clearly and in spite of themselves, have a good deal in common, it is because their work most sensitively mirrors and reflects the preoccupations and anxieties, the emotions and thinking of many of their contemporaries in the Western world.

[4] From Stankiewicz, “Slawomir Mrozek: Two Forms of the Absurd”:

to the Warsaw audience Ionesco and Beckett are felt to be political writers. Their characters, like Mrozek's slogan-spouting little men, are seen as victims of a specific way of life forced upon them. The ‘enemy’ can be identified, or rather he is discovered, while the laughter still echoes through the theater.

[5] Take this from The Captive Mind by Czesław Miłosz, describing the mental shock of conquest in WW2 Poland:

[A man’s] first stroll along a street littered with glass from bomb-shattered windows shakes his faith in the ‘naturalness’ of his world. The wind scatters papers from hastily evacuated offices, papers labeled ‘Confidential’ or ‘Top Secret’ that evoke visions of safes, keys, conferences, couriers, and secretaries. Now the wind blows them through the street for anyone to read…he stops before a house split in half by a bomb, the privacy of people's homes—the family smells, the warmth of the beehive life, the furniture preserving the memory of loves and hatreds—cut open to public view…overnight money loses its value and becomes a meaningless mass of printed paper….Once, had he stumbled upon a corpse on the street, he would have called the police…Now he knows he must avoid the dark body lying in the gutter, and refrain from asking unnecessary questions…Everyone ceases to care about formalities, so that marriage, for example, comes to mean little more than living together....Respectable citizens used to regard banditry as a crime. Today, bank robbers are heroes because the money they steal is destined for the Underground….The nearness of death destroys shame. Men and women…copulate in public, on the small bit of ground surrounded by barbed wire—their last home on earth.

[6] See Daniel Gerould’s interpretation from The Mrożek Reader:

Tango takes the family as a microsociety, or scale model, for studying the history of modern Europe. The disintegration of the three different generations of the farcical Stomil clan, each representing a further step in the historical debacle, charts the decline and fall of European civilization from turn-of-the-century liberalism through interwar avant-garde experimentation to the present-day triumph of totalitarianism. By the use of parody and allusion (citations come from Shakespeare and the Polish romantic and modernist traditions), Mrozek creates a multi-layered work—a museum of modern European art, manners, and morals—which serves as a prism for viewing the relations of culture to power and for assessing the intelligentsia’s responsibility for glorifying force as the ultimate value.

[7] The Bald Soprano by Eugène Ionesco, trans. Donald M. Allen.

[8] Even compared to much of Mrożek’s work prior to Tango.

[9] Written in 1901, Wesele (or “The Wedding”) is one of the preeminent works of Polish theater. It tells the story of a wedding party celebrating the mixed-class marriage of a young city poet to a peasant girl. The party is made up of guests from all walks of Polish life, and they mingle uneasily over the course of the night. Ghosts from Polish history and mythology appear, exacerbating the social tensions.

[10] See The Captive Mind for a description of the experience of living in a political and intellectual atmosphere in which Soviet dialectical materialism was the dominant philosophy. It’s difficult to pick any one particular quote, but here are a couple:

Dialectics is the ‘logic of contradictions’ applicable, according to the wise men, to those cases where formal logic is inadequate, namely to phenomena in motion. Because human concepts as well as the phenomena observed by men are in motion, ‘contradictions contained in the concepts are but reflections, or translations into the language of thought, of those contradictions which are contained in the phenomena.’ [...] The Method exerts a magnetic influence on contemporary man because it alone emphasizes, as has never before been done, the fluidity and interdependence of phenomena. Since the people of the twentieth century find themselves in social circumstances where even the dullest mind can see that ‘naturalness’ is being replaced by fluidity and interdependence, thinking in categories of motion seems to be the surest means of seizing reality in the act. The Method is mysterious; no one understands it completely–but that merely enhances its magic power. Its elasticity, as exploited by the Russians, who do not possess the virtue of moderation, can result at times in the most painful edicts. Nevertheless, history shows us that a healthy, reasoning mind was rarely an effective guide through the labyrinth of human affairs. The Method profits from the discoveries of Marx and Engels, from their moral indignation, and from the tactics of their successors who have denied the rightness of moral indignation. It is like a snake, which is undoubtedly a dialectical creature: ‘Daddy, does a snake have a tail?’ asked the little boy. ‘Nothing but a tail,’ answered the father. This leads to unlimited possibilities, for the tail can begin at any point.

Paradoxical as it may seem, it is this subjective impotence that convinces the intellectual that the one Method is right. Everything proves it is right. Dialectics: I predict the house will burn; then I pour gasoline over the stove. The house burns; my prediction is fulfilled. Dialectics: I predict that a work of art incompatible with socialist realism will be worthless. Then I place the artist in conditions in which such a work is worthless. My prediction is fulfilled.

*

SOURCES

This list is not academically exhaustive, and isn’t trying to be. I was limited by what I could read in five months–both in terms of personal interest and ability, and in terms of what I could get access to. But it should give a general idea re: what has informed this post.

Plays & Fiction:

The Bald Soprano (Eugène Ionesco, trans. Donald M. Allen), The Lesson (Eugène Ionesco, trans. Donald M. Allen), Waiting for Godot (Samuel Beckett), Endgame (Samuel Beckett), The Maids (Jean Genet, trans. Bernard Frechtman), Tango (Sławomir Mrożek, trans. Ralph Manheim and Teresa Dzieduscycka, trans. Nicholas Bethell and Tom Stoppard), The Police (Sławomir Mrożek, trans. Nicholas Bethell), The Elephant (Sławomir Mrożek, trans. Konrad Syrop), The Memorandum (Václav Havel, trans. Vera Blackwell), The Horse (Julius Hay, trans. Peter Hay), Hamlet (William Shakespeare), Macbeth (William Shakespeare), Pygmalion (George Bernard Shaw), The Wedding (Stanisław Wyspiański, trans. Noel Clark), The Marriage (Witold Gombrowicz, trans. Louis Iribarne), Dziady, Part III (Adam Mickiewicz, trans. Google, trans. Count Potocki of Montalk), The Moon is Down (John Steinbeck), Crime and Punishment (Fyodor Dostoyevsky, trans. David McDuff), War and Peace (Leo Tolstoy, trans. Louise and Aylmer Maude), 1984 (George Orwell), Chekhov: The Major Plays (Anton Chekhov, trans. Ann Dunnigan)

Filmed adaptations:

Tango (1999, dir. Maciej Englert), Wesele (1972, dir. Andrzej Wajda), Wesele (2019, dir. Wawrzyniec Kostrzewski), Dziady (1997, dir. Jan Englert), Ślub (1992, dir. Jerzy Jarocki)

Non-fiction:

Anonymous, trans. Philip Boehm. A Woman in Berlin. 1954.

Juliette Bretan.“‘Life Makes Most Sense at the Height of Nonsense’: Interwar Polish Absurdism.” October 2020. [link]

Jan Bończa-Szabłowski. “The young one spoils everything.” November 3, 2010. [link]

Robert Brustein. “Foreword”, Chekhov: The Major Plays. 1982.

Michał Bujanowicz. “On Sławomir Mrożek - Playwright’s Tango.” April 2004. [link]

Michael Childers. “The Direction and Presentation of Tango.” 1977. [link]

Martin Esslin. Theater of the Absurd, Third Edition. 2001.

Martin Esslin. “Introduction,” Three East European Plays. 1970.

Daniel Gerould. “Introduction: Mrożek for the Twenty-First Century,” The Mrożek Reader. 2004.

Eugenia Semyonovna Ginzburg, trans. Paul Stevenson and Max Hayward. Journey Into the Whirlwind. 1967.

Malwina Głowacka. “Tango.” Więź, No. 11. November 1, 1997. [link]

Joanna Godlewska. “Tango.” Przegląd Powszechny, No. 9. 1997. [link]

Jacek Kopciński. “Sleep and awakening.” March 2019. [link]

Jan Kott, trans. L. Krzyzanowski. “Introduction: Face and Grimace, ” The Marriage. 1969.

Janusz R. Kowalczyk. “Tender Irony.” Rzeczpospolita, No. 14. June 19, 1997. [link]

Magnus J. Kryński. “Mrozek, Tango, and an American Campus.” The Polish Review, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Spring, 1970). [jstor]

Keith Lowe. Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II. 2012.

Wojciech Majcherek. “The Last ‘Tango’ in Warsaw.” Express Wieczorny, No. 140. June 17, 1997. [link]

Czesław Miłosz, trans. Jane Zielonko. The Captive Mind. 1953.

Michael C. O’Neill. “A Collage of History in the Form of Mrozek’s Tango.” The Polish Review, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1983). [jstor]

Jerzy Peterkiewicz. “Introduction: The Straw Man at a Wedding,” The Wedding. 1998.

Jacek Sieradzki. “The author of ‘Tango’ dances with us.” Polityka, No. 37. September 13, 1997. [link]

Marketa Goetz Stankiewicz. “Slawomir Mrozek: Two Forms of the Absurd”. Contemporary Literature

Vol. 12, No. 2 (Spring, 1971). [jstor] [scribd]

Mardi Valgemae. “Allegory of the Absurd: An Examination of Four East European Plays.” Comparative Drama, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Spring 1971). [jstor]

Jacek Wakar. “Great ‘Tango’ for the opening of a new stage.” Życie Warszawy. June 16, 1997. [link]

Piotr Zaremba. “Important ‘Wedding’ Anno domini 2019.” February 19, 2019. [link]

“Tango.” FilmPolski.pl. [link]

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

best picture

For the first time in a long time, I watched all of the movies nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars this year. Partly on a whim, partly for a piece I’ve been working on for a while about what is going wrong in contemporary artmarking. I cannot say that the experience made me feel any better or worse about contemporary movies than I already felt, which was pretty bad. But sometimes to write about a hot stove, you gotta put your hand on one. So. The nominees for coldest stove are:

Poor Things. Did not like enough to finish. I always want to like something that is making an effort at originality, strangeness, or style. Unfortunately, the execution of those things in this movie felt somehow dull and thin. Hard to explain how. Maybe the movie’s motif of things mashed together (baby-woman, duck-dog, etc) is representative. People have been mashing things together since griffins, medleys, Avatar the Last Airbender’s animals, Nickelodeon’s Catdog, etc. Thing + thing is elementary-level weird. And while there’s nothing wrong with a simple, or well-worn premise, there is a greater burden on an artist to do something interesting with it, if they go that route. And Poor Things does not. Its themes are obvious and belabored (the difficulty of self-actualization in a world that violently infantilizes you) and do not elevate the premise. There’s a fine line between the archetypal and the hackish, and this movie falls on the wrong side of it. It made me miss Crimes of the Future (2022), a recent Cronenberg that was authentically original and strange, with the execution to match.

Anatomy of a Fall. Solid, but not stunning. The baseline level of what a ‘good’ movie should be. It was written coherently and economically, despite its length. It told a story that drew you along. I wanted to know what happened, which is the least you can ask from storytelling. It had some compelling scenes that required a command of character and drama to write—particularly the big argument scene. The cinematography was not interesting, but it was not annoying either. It did its job. This was not, however, a transcendent movie.

Oppenheimer. Did not like enough to finish. But later forced myself to, just so no one could accuse me of not knowing what I was talking about when I said I disliked it. I felt like I was being pranked. The Marvel idea of what a prestige biopic should be. Like Poor Things, it telegraphed its artsiness and themes and has raked in accolades for its trouble. But obviousness is not the same as goodness and this movie is not good. The imagery is painfully literal. A character mentions something? Cut to a shot of it! No irony or nuance added by such images—just the artistry of a book report. The dialogue pathologically tells instead of shows. It constantly, cutely references things you might have heard of, the kind of desperate audience fellation you see in soulless franchise movies. Which is a particularly jarring choice given the movie’s subject matter. ‘Why didn’t you get Einstein for the Manhattan project’ Strauss asks, as if he’s saying ‘Why didn’t you get Superman for the Avengers?’ If any of this referentiality was an attempt to say something about mythologization, it failed—badly. The movie is stuffed with famous and talented actors, but it might as well not have been, given how fake every word out of their mouths sounded. Every scene felt like it had been written to sound good in a trailer, rather than to tell a damn story. All climax and no cattle.

Barbie. Did not like enough to finish. It had slightly more solidity in its execution than I was afraid it would have, so I will give it that. If people want this to be their entertainment I will let them have it. But if they want this to be their high cinema I will have to kill myself. Barbie being on this list reminds me of the midcentury decades of annual movie musical nominations for Best Picture. Sometimes deservingly. Other times, less so. The Music Man is great, but it’s not better than 8 1/2 or The Great Escape, neither of which were nominated in 1963. Musicals tend to appeal to more popular emotions, which ticket-buyers and award-givers tend to like, and critics tend to dislike. I remember how much Pauline Kael and Joan Didion hated The Sound of Music (which won in 1966), and have to ask myself if in twenty years I’ll think of my reaction to Barbie the same way that I think of those reviews: justified, but perhaps beside the point of other merits. Thing is. Say what you want about musicals, but that genre was alive back then. It was vital. Bursting with creativity. For all Kael’s bile, even she acknowledged that The Sound of Music was “well done for what it is.” [1] Contemporary cinema lacks such vitality, and Barbie is laden with symptoms of the malaise. It repeatedly falls back on references to past aesthetic successes (2001: A Space Odyssey, Singin’ in the Rain, etc) in order to have aesthetic heft. It has a car commercial in the middle. It’s about a toy from 60 years ago and politics from 10 years ago. It tries to wring some energy and meaning from all of that but not enough to cover the stench of death. I’d prefer an old musical any day.

American Fiction. Was okay. It tried to be clever about politics, but ended up being clomping about politics. At the end of the day, it just wasn’t any more interesting than any other ‘intellectual has a mid-life crisis’ story, even with the ‘twist’ of it being from a black American perspective. Even with it being somewhat self-aware of this. But it could have been a worse mid-life crisis story. The cinematography was terrible. It was shot like a sitcom. Much of the dialogue was sitcom-y too. I liked the soundtrack, what I could hear of it. The attempts at style and meta (the characters coming to life, the multiple endings) felt underdeveloped. Mostly because they were only used a couple times. In all, it felt like a first draft of a potentially more interesting movie.

The Zone of Interest.Wanted to like it more than I did. Unfortunately, you get the point within about five minutes. If you’ve seen the promotional image of the people in the garden, backgrounded by the walls of Auschwitz, then you’ve already seen the movie. Which means that all the rest of the movie ends up feeling like pretentious excess instead of moving elaboration. It seemed very aware of itself as an Important Movie and rested on those laurels, cinematically speaking, in a frustrating way. It reminded me of video art. I felt like I had stepped through a black velvet drape into the side room of a gallery, wondering at what point the video started over. And video art has its place, but it is a different medium. Moreover video art at its best, like a movie at its best, takes only the time it needs to say what it needs to say.

Past Lives. I’m a human being, and I respond to romance. I appreciate the pathos of sweet yearning and missed chances. And I understand how the romance in this movie is a synecdoche for ambivalent feelings about many kinds of life choices, particularly the choice to be an immigrant and choose one culture over another. The immigrant experience framing literalizes the way any choice can make one foreign to a past version of oneself, or the people one used to know, even if in another sense one is still the same person. So, I appreciate the emotional core of what (I believe) this movie was going for, and do think it succeeded in some respects. And yet…I was very irritated by most of its artistic choices. I found the three principal characters bland and therefore difficult to care about, sketched with only basic traits besides things like Striving and Being In Love. Why care who they’d be in another life if they have no personalities in this one? It’s fine to make characters symbols instead of humans if the symbolic tapestry of a movie is interesting and rich, but the symbolic tapestry of this movie was quite simple and straightforward. Not that that last sentence even matters much, since the movie clearly wanted you to feel for the characters as human beings, not just symbols. Visually, the cinematography was dull and diffuse, with composition that was either boring or as subtle as a hammer to the head.

Maestro. Did not like enough to finish. Something strange and wrong about this movie. It attempts to perform aesthetic mimicry with impressive precision—age makeup, accents, period cinematography—but this does not make the movie a better movie. At most it creates spectacle, at worst it creates uncanny valleys. It puts one on the lookout for irregularities, instead of allowing one to disappear into whatever the movie is doing. Something amateurishly pretentious in the execution. And not in the fun, respectable way, like a good student film. (My go-to example for a movie that has an art-school vibe in a pleasant way is The Reflecting Skin). There’s something desperate about it instead. It has the same disease as Oppenheimer, of attempting to do a biopic in a ‘stylish’ way without working on the basics first. Fat Man and Little Boy is a less overtly stylish rendition of the same subject as Oppenheimer, but far more cinematically successful to me, because it understands those basics. I would prefer to see the Fat Man and Little Boy of Leonard Bernstein’s life unless a filmmaker proves that they can do something with style beyond mimicry and flash.

The Holdovers. Did not like enough to finish. It tries to be vintage, but outside of a few moments, it does not succeed either at capturing what was good about the aesthetic it references, or at using the aesthetic in some other interesting way. The cinematography apes the tropes of movies and TV from the story’s time period, but doesn't have interesting composition in its own right. It lacks the solidity that comes from original seeing. (Contrast with something like Planet Terror, in which joyous pastiche complements the original elements.) The acting is badly directed. Too much actorliness is permitted. Much fakeness in general between the acting, writing, and visual language. If a movie with this same premise was made in the UK in the 60’s or 70's it would probably be good. As-is the movie just serves to make me sad that the ability to make such movies is apparently lost and can only be hollowly gestured at. That said, the woman who won best supporting actress did a good job. She was the only one who seemed to be actually acting.

Killers of the Flower Moon. The only possible winner. It is not my favorite of Scorsese’s movies, but compared to the rest of the lineup it wins simply by virtue of being a movie at all. How to define ‘being a movie’? Lots of things I could say that Killers of the Flower Moon has and does would also be superficially true of other movies in this cohort. Things like: it tells a story, with developed characters who drive that story. Or: it uses its medium (visuals, sound) to support its story and its themes. The difference comes down to richness, specificity, control, and a je ne sais quois that is beyond me to describe at the moment. Compare the way Killers of the Flower Moon uses a bygone cinematic style (the silent movie) to the way that Maestro and The Holdovers do. Killers of the Flower Moon uses a newsreel in its opening briefly and specifically. The sequence sets the scene historically, and gives you the necessary background with the added panache of confident cuts and music. It’s useful to the story and it’s satisfying to watch. Basics. But the movie doesn’t limit itself to that, because it’s a good movie. The sequence also sets up ideas that will be continuously developed over the course of the movie.* And here’s the kicker—the movie doesn’t linger on this sequence. You get the idea, and it moves on to even more ideas. Also compare this kind of ideating to American Fiction’s. When I said that American Fiction’s moments of style felt underdeveloped, I was thinking of movies like Killers of the Flower Moon, which weave and evolve their stylistic ideas throughout the entire runtime.

*(Visually, it places the Osage within a historical medium that the audience probably does not associate with Native Americans, or the Osage in particular. Which has a couple of different effects. First, it acts as a continuation of the gushing oil from the previous scene. It’s an interruption. A false promise. Seeming belonging and power, but framed all the while by a foreign culture. Meanwhile potentially from the perspective of that culture, it’s an intrusion on ‘their’ medium. And of course, this promise quickly decays into tragedy and death. The energy of the sequence isn’t just for its own sake—it sets up a contrast. But on a second, meta level it establishes the movie’s complicated relationship to media and storytelling. Newsreels, photos, myths, histories, police interviews, and a radio play all occur over the course of the movie. And there’s the movie Killers of the Flower Moon itself. Other people’s frames are contrasted with Mollie’s narration. There’s a repeated tension between communication as a method of knowing others and a method of controlling them—or the narrative of them—which plays out in both history and personal relationships.)