#posts: art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the storytelling in severance season two so far is reminding me somewhat of farscape season three. both use a scifi conceit to literally split characters into different selves, and thereby explore their competing desires, particularly with regards to romance, and selfhood by extension.

(spoilers for both)

in farscape season three the protagonist is split into two equal selves. one of the john crichtons is able to resolve two seasons of romantic tension, and be in a happy relationship with his alien love interest. meanwhile the other john, bereft of love, obsessively attempts to perfect the technology that will take him home to earth. metaphorically, it’s a conflict between two versions of home, or selfhood. a self that is familiar, versus one that is alien. john yearns for a version of himself that can have it all: earth and aeryn, past and future, known and unknown. but the myth that underlies the season is icarus, and the folktale is the dog with with two bones. one of the johns does seem like he will get it all, and will even be healed of the scifi-metaphor for pain and trauma that haunts his brain—the neural chip harvey. but it turns out that this perfect resolution is impossible. the john that tries to have it all dies; the john that remains as the show’s main character is the john that has nothing. it turns out that it is not possible to simultaneously change and not change. “you can’t go home again,” essentially. if john is to truly move forward, according to the show, he must confront the reality of loss that is inherent to becoming something new, regardless of whether that new thing involves beauty and wonder (love) or something terrible (pain).

similarly in severance season two so far you have one version of mark who has spiraled downwards without love. and who, as of the most recent episode (2x03 “who is alive?”), is willing to risk himself to get that past love back. this is contrasted with a version of mark who “has everything.” he is not shattered by grief, he has a new love interest, he still has some innocence. like the johns, one mark is obsessively fixated on a former state, and one is able to narratively advance. but the fact that the story of how good the more innocent version of mark has it comes from lumon (“the mark i’ve come to know at lumon is happy”) emphasizes how much it is, indeed, a story. that version has also experienced loss, and suffering, and his existence is, of course, literal corporate slavery. it potentially foreshadows that now that one mark is attempting to “have everything” to an even greater degree, by stitching together his separate selves, that something will go wrong. like farscape with icarus, there are two myths suggested by the show so far: the orpheus and eurydice myth, which doesn’t bode well, and the persephone myth, which could go in a number of directions.

both shows use the season’s credit sequence to express the idea of self-conflict. in farscape, the narration over the season three credits is split into two echoing voices, and its description of the show’s premise becomes divided and confused. instead of john saying he’s “just trying to find a way home”, and to meanwhile “share the wonders i’ve seen” as he does in the credits for seasons one and two, john in the season three narration wonders if he wonder if he should “open the door” to earth, or leave it shut. he starts asking questions: “are you ready?”, “or should i stay?” he starts describing the things he’s seen as both “nightmares” and “wonders”. similarly the credits for season two of severance are full of duality and conflict. there is imagery of gemma on one side, and helly on another. the women flicker and run in opposite directions. meanwhile the two marks simultaneously work together and seem at odds. sometimes one mark pulls and carries the other. but instead of the season two credits ending with the two marks merging, as they do in the first season credits, one mark now attempts to crawl its way out of the other.

in general, both shows seem to use the idea of pain, grief, or trauma as a kind of psychological splitting point. and use romantic love to make the longing and loss (the positive and negative) involved in change more visceral. in mark’s case, the metaphor is pretty literal and immediate—the starting premise of the show is that he has split himself into two consciences because of grief for his wife. in john’s case, the metaphor takes a bit longer to develop. he changes in increasingly dark ways over the course of the first two seasons, and only by season three is it time to physically split him in order to explore the implications of those changes. this difference makes sense based on the type of story that each show is derived from. severance is more of a modern gothic tale, exploring the consequences of repression in an eerie atmosphere. farscape on the other hand, is more of a modern odyssey or wizard of oz, a mythological tale of displacement and change.

i don’t have predictions on specific developments in severance, but i’m interested to see where it goes with the metaphorical framework it’s set up so far. like farscape, it could easily end in a dog with two bones sort of way—by trying to have two contradictory things, mark loses both. and perhaps that will be a necessary nadir on the path to some ultimate stage of resolution. regardless, it’s nice to see a new scifi show making use of the genre’s ability for metaphor in a way that doesn’t (yet) feel boring or underdeveloped, whatever it chooses to do with it.

#posts: art#severance#farscape#this needed another meta level but c'est la vie#the meta the enemy of the object sometimes

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

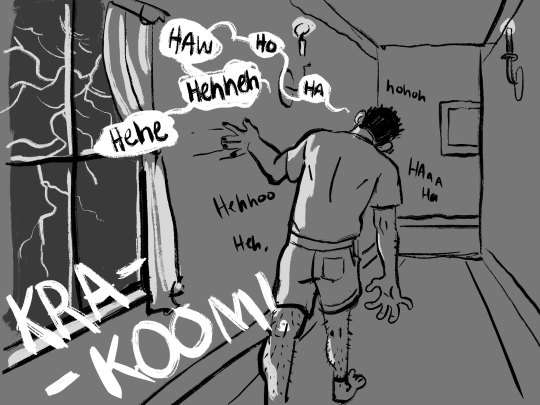

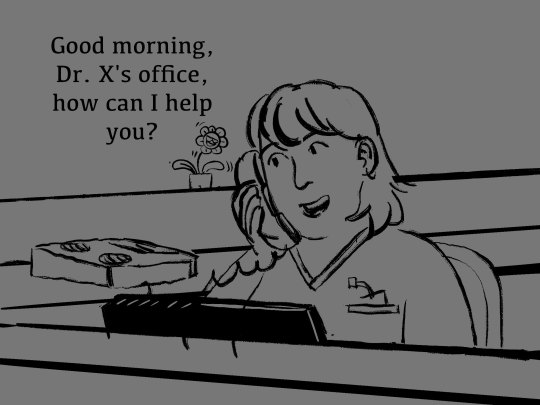

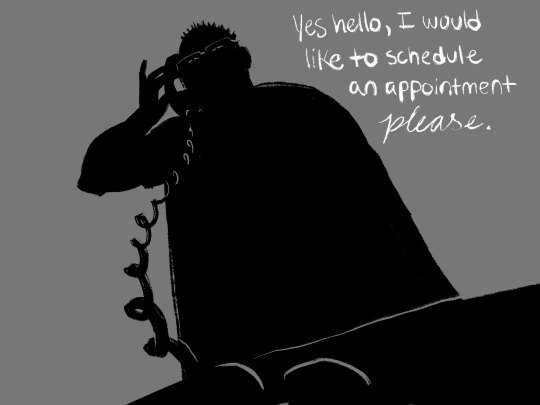

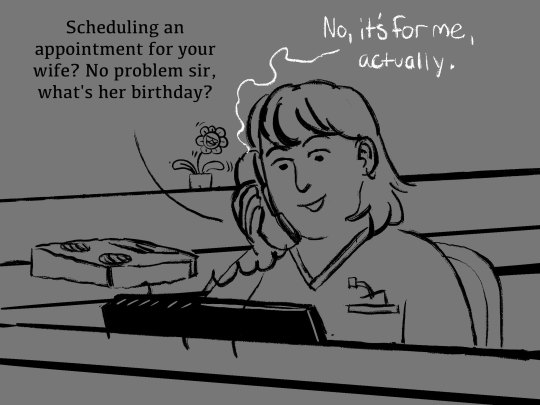

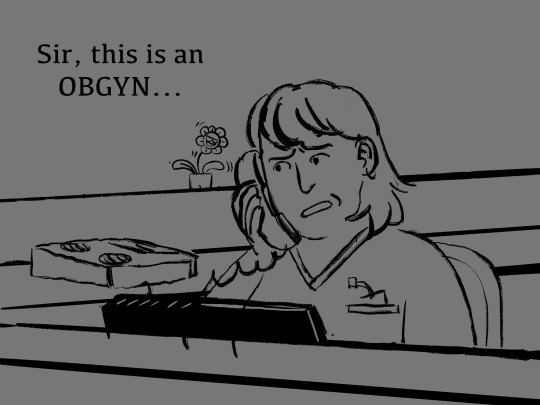

*doom music starts to play* I actually kindof like scheduling these kinds of appointments now...

but seriously Fellas, don't forget to schedule a pap smear every couple of years just in case. If you still have a cervix you can still get cervical cancer. ilu

this has been a psa

#my art#my comics#og post#psa#trans healthcare#gender affirming receptionist lady#transgender#lgbt#queer comics

173K notes

·

View notes

Text

🐊🐊🐊🐊🐊

#my art#digital art#digital painting#doechii#idek if i like this anymore but whtever spent too long to not post#lowkey i like the car in the bg more i have over-working disease when it comes to digital painting#and ive looked at jt too long i cant perceive it anymore#id in alt text#artists on tumblr

72K notes

·

View notes

Text

lil doodle from the other day born out of an overwhelming annoyance that for some reason body hair is associated with masculinity despite Everyone Having It. so why not draw a cute hairy girl about it

[image description: a drawing of a tan-skinned woman with brown and blond dyed hair pulled into a ponytail and copious body hair and stubble. she is smiling and doing a peace sign gesture with her hand. next to her is text saying "body hair has no gender!" end id]

#been apprehensive about posting this since i dont want people to be. Annoying.#but then i realized i dont care#doc talks#my art

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wife lovers till they die

#Viktor’s pout when Jayce said no to ascending with him was all I needed to see.#or my fave bridge scene#the man folded immediately#vi loves cait sm like#do I even need to bring examples#act 2 s2 is literally the only proof I need#cait could be on this post too but#this duo is so silly to me#art#fanart#digital art#fan art#my art#arcane#arcane fanart#vi arcane#jayce talis#jayvik#caitvi#what the hell sure#meljay#love wins#book street#bookstreet

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

hecate

#soc art#animation#greek mythology#hecate#triple goddess#maiden mother crone#this was actually for a class but im on break so spent ages on it#idk any of the witchcraft stuff im just exploring her evolution from the greek goddess#and remaking an early depiction of her statues#originally tried interpolating the moon and it looked Shit im glad i drew it#tumblr gets first post bc its my fave social media people always Get It here#artists on tumblr

55K notes

·

View notes

Text

#dank memes#funny#funny memes#funny post#funny stuff#meme#memes#tumblr memes#drawing#digital art#artwork#art#digital drawing

66K notes

·

View notes

Text

via @swatercolour here on Tumblr and also on [insta]

EDIT: I do not interpret "just managing" as "just suffering, just enduring, curling into a fetal position and waiting for it to be over." Managing is an active process.

So I'm using this post as a platform to make the reminder that "the power of the people is greater than the people in power," and we all are cordially invited to:

Take good care of ourselves. Mental, physical, emotional health. Hydrate. Move if we can, get outside if we can.

Keep up a routine. Remember quarantine and we all had to find a routine? This is the same.

Be intentional in our news consumption. Let's not stick our heads in the sand but let's not doomscroll either. Get an RSS aggregator. Subscribe to WTF Just Happened Today, Yoour Local Epidemiologist, Fix The News (for some inspiring hopeful news!). We'll check our feeds a few times a week, but no more than once a day.

Connect with friends and loved ones. Remind ourselves that while SOME people are horrible, for the most part people are awesome... if complicated. Share our fears but also our hopes. Eat together.

Now that we're keeping healthy, safe, sane, and hopeful... now we also fight. Quietly if we prefer, loudly if we prefer. But sustainably. I hate that I had to live through three rounds of this nonsense where a few people use half of us as tools to fuck over ALL of us, but here we are again. So let us take just one moment every week or so to...

Use 5calls to keep blowing up our reps phones. Tell them to either break ranks with the Orange Administration, or to stand up louder than just matching outfits and signs. Or to THANK them for standing up.

Use Vote411 to find elections before the midterms. A lot of villages, cities, townships etc have local elections that will affect where we live... and more importantly, the people in office there will affect things upwards too.

Use Ballotpedia to know exactly what's on our ballots ahead of time.

Protest, because it actually works.

Use Vote.org to make a plan to vote in the midterms. Make a plan that is immune to voter suppression tactics. Get our documents in order. Reach out to our friends to go to the polls as a group. Plan to livestream our visit, up until the point we have to turn our cameras off.

Make and share memes that promote hope, organizing, solidarity, and/or resistance.

Get involved with an action network like Indivisible, MoveOn, or Working Families Party.

Go to a local town hall meeting. Speak up.

Heck, start our own local activism networks, letter campaigns, call campaigns, or fundraisers with Action Network.

And we will remember our self-care. We will remind ourselves and each other that they want us scattered, focus is how we resist.

It IS coming back. Things ARE going to get worse. The world has become a place where a very few people are pulling levers and pushing buttons that are actively destroying much of what is good about living in a society where people care for each other.

Many others are in shock, sputtering "but can they do that?" MANY many others are waiting for someone to come save us.

But there are those who are actively, loudly, opposing.

And there are more people speaking up, acting up, every day. More people saying it's time to get scrappy. It's time to get into some good trouble. The shock is wearing off.

Yes, it's gonna get worse before it gets better (the long-term damage of the acts of the past momentum of all the damage that has been done will take that long to be felt -- but it WILL get better.

If WE will it.

#hope#resist#I have this image on my screensaver#I could NOT find the art on Tumblr or I would have RB'd it#I could find it on Xitter I could find it on Insta but not here#Tumblr I beg you - search please#and yeah I'm updating this with text from my Take Action post

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

We all making grandpa cry btw

#world news#anime art#anime memes#twitter#tweet#dank memes#funny post#meme#dank#funny#funny pics#silly#funny pictures#dankest memes#humor#ai art

48K notes

·

View notes

Text

Everybody always so bold when dunking from the other parallel dimension 😔

"Redraw tumblr post" time of the year again, based on this one specifically that i found weeks ago but I needed to do something with it hfgjdh (with the original post being on tiktok). I just love canon Blaze being absolutely ass at cooking💜

#sonic the hedgehog#blaze the cat#shadow the hedgehog#silver the hedgehog#amy rose#knuckles the echidna#miles tails prower#dr eggman#rouge the bat#e-123 omega#vector the crocodile#espio the chameleon#charmy bee#jet the hawk#wave the swallow#professor victoria#marine the raccoon#tangle the lemur#my art#auroblaze art#tumblr post meme#tiktok

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

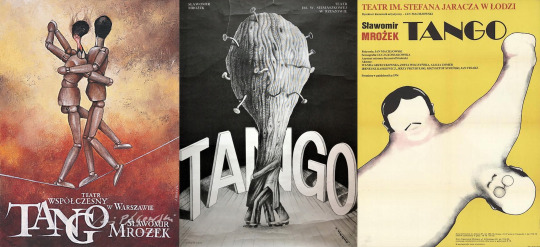

Theory, Reality, and 'Tango'

Happy to share a project I’ve been working on for the last few months. Around July, I happened upon a TV staging of the Polish play Tango by Sławomir Mrożek. Written in 1964, Tango is a classic of the mid-century Theater of the Absurd, as well as Polish avant-garde drama. It’s a highly famous play in Poland—a staple of high school curricula—but less well-known in the anglosphere these days. I enjoyed the staging a lot, and because it had no English subtitles, I thought I’d try to make some myself. This was a particularly fun project given that, as far as I know, the play hasn’t had a new English translation since 1968 [1]. I’ll use another post to talk a bit more about the translation process and the philosophy of translation that I found myself adopting—particularly how it differed from the philosophy I might have adopted if I was translating the play in book form, rather than a performance of it.

But for the moment, the long and short is that you can now watch Tango with my English translation on Youtube here. If you have a VPN (or are located in Poland), you can also watch on the Polish TVN website in better quality using a subtitle extension like Movie Subtitles or Substital. All subtitle files can be downloaded here.

youtube

As for the play. Tango takes place in a middle-class home of the 1960’s, and the drama centers on the dynamics between three generations of a single family. In Tango’s version of the world, permissiveness has won a complete cultural victory. Victorian traditionalism was overturned by the rebels and artists of the 1920’s, and all social values and conventions have since disappeared. Fed up with his family’s chaotic household, 25-year-old Artur, a member of the youngest generation, longs for his own form of rebellion. But with no conventions left to overthrow, the only rebellion remaining for Artur is rules and traditions. He attempts to instill order and re-impose tradition by force, but (avoiding specifics) it doesn’t go according to plan. In the end, no form of idealism wins in Tango. Not traditionalism, anti-traditionalism, or anti-anti-traditionalism. Instead, idealism ends up hollowed out and puppeted by those who are unscrupulous and willing to use violence to get what they want.

Tango struck me first because it was funny, and witty, and thematically felt startlingly relevant to the present day. This particular performance from 1999 that I’ve chosen to subtitle also struck me for being remarkably well-acted and well-staged. It’s tough to make absurdism feel emotionally genuine enough to have a dramatic effect, instead of descending into shallow pantomime and parody, and this rendition of Tango by director Maciej Englert pulls it off very well. The cast is comprised of some of Poland’s greatest stage actors of that time, and it shows.

But the play also made an impression on me because it seemed to be an unusual hybrid of theatrical modes, both in general and in the context of the Theater of the Absurd. Theater of the Absurd is often talked about as having a Western and an Eastern incarnation [2]. In the West, absurdism was considered existential and apolitical, while in the East—ie, in countries under Soviet control—absurdism was used to discuss ideas that were not safe to discuss directly. In reality, of course, this supposed division was not nearly so clear-cut. Especially since “Theater of the Absurd” wasn’t any kind of coherent artistic movement to begin with, but more of a general aesthetic trend [3]. Plenty of works that came out of the Western Theater of the Absurd had political attitudes, or at the very least observed dynamics with political implications [4]. And plenty of works that came out of the East depicted dynamics that resonated with people beyond those who lived within the Soviet bloc. This duality is especially alive in Tango, which is one of the reasons I found it such a fun and tricky play to pin down. On the one hand, one can read it as an allegory for, or commentary on, many specific things related to 19th and 20th century Polish history. On the other hand, the play’s ideas are also broad enough that it ends up feeling relevant to any number of cultures, eras, and situations.

This ink-blot quality is one of the reasons for the play’s lasting appeal. For example, how to read the collapse of values at the beginning of the play? Perhaps the social permissiveness refers to the actual liberalism of the 1920’s, and the failures of the intelligentsia that facilitated the Nazi takeover of Poland in the 1940’s. Or perhaps it refers to the destruction of decency and normalcy in the midst of war and occupation [5]. Or it refers to life on the shifting sands of Soviet dialectics, the struggle to create real meaning out of something that claims to be progressive, yet feels inherently insubstantial. Or it refers to a more general secular, postmodern condition. If values are arbitrary and self-created, then how does one choose what values to create? One reviewer of this staging observed how the impression Tango made had changed since 1964: "Artur's hysteria meant something different in the Polish People's Republic, a land of ideologues without ideals, than it does today. Searching for values at random was a mockery then—today it is perhaps one of the most moving scenes in the play.”

(See also Martin Esslin in The Theater of the Absurd: “When Tango was first performed in Warsaw in 1964 it understandably produced a violent reaction: the audience interpreted the play’s message as a sardonic comment on Stalinism and its totalitarian structure of terror. But the play made an equally strong impact in Western Germany and other countries of non-Communist Europe…[T]he growth of arbitrary bureaucratic power, the erosion of political ideals and the consequent pursuit of power for its own sake by otherwise undistinguishable parties, led by crude, uncultured careerists, might also, after all, turn out to be a feature of…‘advanced’ Western societies.”)

All this said. I don’t think Tango is simply somehow “accidentally” about ideas that can be interpreted as being about something other than Poland’s immediate travails. Arguably, the duality exists in the text itself. The play is about Poland and Europe [6], it is in conversation with other Polish drama about Poland (Wesele, Dziady), as well as Polish absurdism (Witkacy, Gombrowicz). And it is also about things like values, and power, and art writ large, and is in conversation with Beckett, Ionesco, Chekhov, Shakespeare, and others. Specificity and universality feed each other—this is nothing new in art.

If anything, the tension between the specific and the universal seems like one of the biggest features of the play. Tango is a war between idea and reality, the abstract and the concrete. And this is another way in which it’s an unusual theatrical hybrid. You might even call it a theatrical identity crisis.

Broad history: Prior to the 19th century, Western theater did not tend to be realistic in the modern sense of it. Instead it was characterized by symbolism, exaggeration, and verse. Greek plays, opera, Shakespeare, Molière. Such theater could be subtle and true, but it did not generally aim for trompe l’oeil mimicry of real life, or have much interest in “regular” people and everyday events. Then after a 19th and 20th century turn towards realism (Chekhov, Ibsen, Shaw, etc), the Theater of the Absurd introduced a new and defiant kind of abstraction. In absurdist plays there might be internal, if absurd, logic, but the settings, characters and narratives tend to have only a limited amount of naturalism. Images are symbolic, language is Aesopian, and events take place in dreamy, generalized settings rather than a particular time and place. To the extent that absurdist plays use the concrete or naturalistic, it’s usually to immediately subvert it. Eugène Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano, for instance, blares the Englishness of the characters and the setting, but in a way that is obviously nonsensical, and comedic (or horrific) precisely because it has only a superficial correspondence to the England of real life:

MRS. SMITH: There, it’s nine o’clock. We’ve drunk the soup, and eaten the fish and chips, and the English salad. The children have drunk English water. We’ve eaten well this evening. That’s because we live in the suburbs of London and because our name is Smith. [7]

Or The Lesson, another Ionesco, starts out in a naturalistically appointed room, with what could be naturalistic characters, but within two pages begins a jarring descent into blatant absurdity. Theater of the Absurd doesn’t just do away with realism, either. It also does away with the conventional narrative structures of both realistic and earlier, less-realistic theater. Various works in the Theater of the Absurd were called anti-theater for this reason. Instead of having a typical beginning, middle, and end, or problem-escalation-resolution, absurdist plays are often circular and unresolved. Vladimir and Estragon start Waiting for Godot waiting, and they finish it waiting. The endings of The Bald Soprano and The Lesson repeat their beginnings, like a mirror reflected in a mirror. Absurdity arises from the inescapable, Sisyphean nature of existential dilemmas, and this ends up reflected in the most basic structures of absurdist theater.

Compared to such plays, Tango makes a surprising amount of sense [8]. It has a beginning, middle, and end. It is not set in the real world, but it is set in “a” real world, with a vague but coherent history. The characters don’t speak like real people exactly, but they do have consistent motivations and personalities. They’re not anti-characters like the Smiths and Martins in The Bald Soprano. The play also contains various gestures towards naturalism. The idea of a play about regular people who live in a regular apartment, is taken straight from the realistic tradition. The stage instructions are detailed, insisting upon a set cluttered with specific items, with characters in specific clothes, all of which are taken from real life. Here’s an example from the beginning of Act III:

We see before us a conventional, bourgeois living room from half a century ago. The confusion, blurriness, and lack of contours are gone. The draperies, which had previously been strewn about—half-lying and half-hanging—giving the stage random folds and making it look like a rumpled bed, are now in their places and have become proper, regular draperies. The catafalque remains in the same place…but is now covered with napkins and trinkets, like an ordinary sideboard.

For a key moment of violence, Mrożek even makes a point of saying that the execution must be naturalistic:

Attention! This scene must be very realistic. Both blows must be performed in such a way that their theatrical fiction is not obvious. Have the revolver be made of rubber, or even feathers, or have [the actor] wear some kind of pad under [their] collar. It doesn't matter, as long as it doesn't look ‘theatrical’.

Tango also “makes sense” in that it (seemingly) contains the comprehensible allegory and symbolism of more conventional theater. Each of the characters could potentially be read as a representative of a different generation or some piece of the social fabric, much like the characters in Stanisław Wyspiański’s Wesele [9]. You can read grand-uncle Eugeniusz as the avatar of traditionalism—a class that supposedly cared about values, but in practice turned out to be craven and opportunistic. Or Artur’s father Stomil as the aging, ineffectual avant-garde. Or Artur’s cousin and fiancée Ala as “the people”, torn between Artur’s flavor of bullying idealism, and the vacant brutality of the family’s boorish houseguest Edek.

Yet in spite of all of this “sense”, the play is undeniably absurdist, full of the kind of seeming nonsense typical of other absurdist theater. Artur punishes Eugeniusz by putting a birdcage on his head, or makes his grandmother lie on a catafalque. There are illogical exchanges like the following:

ARTUR: Will you be staying with us for long? ALA: I don’t know. I told my mother I might not come back. ARTUR: What did she say? ALA: Nothing. She wasn’t at home.

And in general, the events of the play progress in an absurd fashion. There’s no logical reason that Artur’s schemes for his family could actually change the social structure of the world. Supposedly serious things like murder and repression are casually and comedically invoked (until they aren’t).

ARTUR: You know what, Father? Why don’t we try [killing Edek] after all? There’s no risk. At worst, you’ll shoot him. STOMIL: You think so?

In other words, Tango references and evokes, in both form and content, the last few hundred years of Western theater. The cultural call-and-response of tradition, rebellion, and counter-reformation that it depicts parallels the artistic call-and-response of traditional theater, realism, and absurdism. It is bogged down by theatrical history much as Artur is bogged down by social history. Or as the family's apartment is bogged down by material history:

This table, even more than the interior as a whole, gives the impression of confusion, randomness and sloppiness. Each plate, each item, comes from a different service, from a different era and is in a different style.

There’s a certain confusion and chaos surrounding what kind of play this is supposed to be. Should a playwright comment on a social situation, express a human condition, or experiment with form? What kind of play is good for art? Good for people? Good in general? Tango features outright mockery of empty avant-garde theater, and an interesting ambivalence about symbolism. On the one hand, the play clearly uses symbolism. On the other hand, it was written in a context in which symbolism and indirectness were required in order for it to be performed in its original language behind the Iron Curtain.

Throughout the play, the characters debate the value of “form”, “reality” and “idea”, and how and whether to either achieve or integrate or discard them. It is the age-old debate, in both society and art, of how to balance theory with reality, truth with artifice. But–just as in history–none of the characters can resolve the debate, and most are hypocrites about their positions. The characters crave and fear reality in equal measure. Stomil, who makes impotent experimental theater, champions the idea of going “beyond form”--ie, going beyond things like rules and abstractions. He denounces the rule-loving Artur as a “vulgar formalist” and celebrates Edek for his “authenticity.” But for all that Stomil claims that his art is trying to achieve some sort of grand concreteness, his creations and explanations are all highly inaccessible and theoretical (after shocking his audience by setting off a gun: “By direct action–we create unity between the moment of action and perception”). And he admits that he doesn’t actually like Edek, who is sleeping with his wife Eleonora (“I’ve had my eye on that scoundrel for a long time. You don’t know how much I’d love to finish him off.”). Meanwhile Artur claims to want a return to order and tradition, but he also wants to rebel–something inherently destabilizing.

STOMIL: What do you want exactly, tradition? ARTUR: World order! STOMIL: Is that all? ARTUR: And the right to rebel.

And when he tries to follow through with his plans he finds the results hollow and unsatisfying. He finds that reality erodes principle, and yet principles that are not animated by an idea, that is in turn animated by reality, lack vitality and endurance. He strives for “a system in which rebellion is one with order, and nothingness with existence” that “will transcend contradictions entirely!” Much like Stomil with his theatrical gunshot, Artur thinks he can conquer such contradictions by wielding force–something seemingly fundamentally “real”. But in the end, his talent turns out to mainly be in exalting the concept of force, rather than actually embodying it.

Meanwhile Eugeniusz supposedly wants a return to propriety. Not so much order, like Artur, but an appearance of moral rectitude, the rituals of civilization (“Start a family. Brush your teeth. Eat with a fork and knife! Make the world sit up straight again instead of slouching.”). He detests Edek’s “filth” and the “degradation” of the rest of the family. Yet for all his love of the forms of properness, no one is more willing to lower himself than Eugeniusz. He is quick to abandon his supposed principles and attach himself to whoever has power.

This sense of contradiction and call-and-response between theory and reality is even echoed in the structure of the play. The first act starts out as more absurdistly symbolist–the characters play rhyming card games, Artur metes out his birdcage and catafalque punishments, Ala turns out to have been hidden under a table the whole time, Stomil puts on a play about Adam and Eve. Then the second act becomes more naturalistic, with long one-on-one, interpersonal conversations that contain more conventional dramatic stakes. And finally the third act combines both modes. The third act is full of both abstract ideas and images–the family in their tight old-fashioned clothes, Artur’s quest for a unifying philosophy–and regular human drama related to marriage and infidelity. Until it finally ends in a moment of violent naturalism, in the form of that realistic blow (“Attention! This scene must be very realistic.”).

Taken as a whole, Tango follows the pattern and tenor of dialectical debate, with satirical circularity. Soviet dialectics promised a means of navigating and resolving contradictions. It promised a means of understanding the cycles of history, and existing in the correct moral relation to them. Add more context, add more cleverness, and the cycles are no longer confusing. You can win them. In practice though, this version of dialectics often merely acted as an elaborate justification for otherwise unjustifiable political ends [10]. But unlike in a dialectical debate, Tango makes the crude, concrete conclusions explicit. The winner of Tango is not a dialectician. The winner is violent reality, simply wearing philosophy’s jacket.

What Maciej Englert’s staging understands, and one of the reasons it had such an effect on me, is the real human feeling that suffuses the play. Artur’s confusion and distress are real. As is Stomil’s frustrated impotence, Ala’s love, or even Eugenia’s fear and irritation. The cozy, chaotic naturalism of the set (taken straight from the script directions) emphasizes this human scale. Tango is not simply a detached satire of Stalinism, “some abstract hypothesis, a play on words, a product of intellectual imagination.” It is about the tension between the human and everything more than human–and in order for that tension to work, the human aspect needs to be just as apparent as the abstract aspect. To paraphrase a good review, Artur in this production is both scary and pitiful, human and symbol. Eleonora seems at first a caricature, but “becomes unexpectedly moving in the scene in which she talks humanly, without a mask, to Ala.” While Ala is full of “the truth of unhappy feelings...the cynicism that usually dominates this role in other stagings is put in quotation marks; [she] only pretends to be nonchalant towards life.” And this is also why it is all the more crushing when both the human and the abstract turn out to have been paving the way for something worse, something they both lose out to.

*

Theater of Absurd appeals to me at the moment. It feels relevant. To the world, to my life. And the way Tango combines the Western and Eastern forms of the absurd gets at why. In the “Eastern” form, absurdism springs from a breakdown of logical reasoning that is imposed by external forces: war, authoritarian whim. Hence plays like Julius Hay’s The Horse, which tells the story of Caligula appointing his horse Incitatus to the Roman Senate, leading the population to start acting like horses. Or Václav Havel’s The Memorandum, in which bureaucratic characters are forced to communicate in an overly-rational neo-language that none of them can understand. In the “Western” form, absurdism springs from a more existential, post-modern breakdown of logical reasoning: how is one to make sense of existence if there is no objective logic? If all of the former institutions of meaning–religion, government, class, materialism, and so on–are meaningless, then what is left? And just as in Tango, it often feels today as if those two forms of absurdity have combined. If they were ever even separate.

No, of course I do not live under a totalitarian state, in the present-day West. I do not worry about gulags or famine or being hauled off in the night for saying the wrong thing. But there is a sense of institutional decay, and a sense of pretending otherwise about this. A sense that important details of my life are determined by obscure power struggles between people who are incompetent or ill-intentioned, or both. A sense of people going insane, and feeling proud of it all the while. A sense of nihilistic chaos lurking at the door, and people saying “Would it be so bad to let it in?” Meanwhile the internet accelerates countless forms of absurdity. It instills a surveillance mindset. It destroys old forms of reverence, and creates new, bizarre ones. Now you can see the most pathetic aspects of politicians and artists and intellectuals laid open on social media. Now you can see regular people turn themselves into grifters, beggars, and compulsive performers. It would almost be more dignified if people did this due to explicit government repression, or out of purely mercenary ambition. Instead of out of a more basic human, animal sense of precarity. Am I important? Am I safe? Do I have enough? Do I belong? Do you like me? Do you like me? Do you like me?

Former markers of respectability are losing their meaning. Respectability itself is losing meaning. And quite possibly these things deserve to be destroyed, perhaps this is just normal cultural turnover, but it’s not yet clear what is waiting to grow out of the rubble. For a while, maybe a decade, there was a swing towards authenticity. Fetishistic authenticity usually, but authenticity nonetheless. Hipster natural material aesthetics–being into leather, wood, iron, pickling. Relatability, parasociality, confession. This all still exists to some degree, but has lost much of its awkward earnestness, some genuine desire to be post-ironic, some kind of novelty. The fakery of amateurism rather than cynicism. Now fakery and authenticity are so intertwined it starts to feel like both have lost their meaning. Performance and entertainment are endemic, except they’ve never felt less like entertainment, or more like narcotics. Performance gains its power from its tension with truth, reality. Without reality, performance is impotent. And yet it’s never been more important. Absurd.

The internet simultaneously creates an unprecedented awareness of reality, and an unprecedented detachment from it. There have long been ways in which one could be awash in information and entertainment from waking until sleep. Television, books. There have been means of stupefaction for even longer. Intoxicants of all kinds. But the internet is more than just a stream of information in which people can lie down, open their jaws, and passively drink. It is interactive, frequently intensely so. The information, unlike in a book, is often related to what is happening right now. And unlike in a paper or on the news, the information is often delivered by people in one’s social circle. Suddenly one is aware of a thousand different things, horrible and otherwise, and not only that, the awareness comes along with the opportunity for action–money, publicity, simple acknowledgement–and hundreds of people one knows can see that action. You can live your life in a holodeck world. Yet down the line, reality keeps being real, and is affected by that holodeck world–mortally and trivially. These are not new observations really. Still, that combination of interactivity, intensity and detachment turns “reality” into something that is both omnipresent and intangible. Absurd.

It’s always been absurd. “Reality” has always been both obvious and ineffable, something to philosophically struggle with. “Truth” has always been difficult to grasp, and difficult to represent. Map and territory, forever locked in combat. But just as circumstances made this fundamental absurdity feel closer to the surface in the mid-20th century, so does it feel closer now. Theater of the Absurd arrived on the heels of decades of talk of perfectibility. Nazi perfectibility, Soviet perfectibility, even the perfectibility of the liberal, capitalist order. Promises of surmounting the lesser aspects of humanity. Purge or plan society in the right way, and you’ll be on the way to becoming better than human. Yet time and again, those lesser aspects had a way of revealing and reasserting themselves. Murder, cruelty, exploitation. Pettiness, cowardice, selfishness. All of these things, it turned out, could thrive regardless (or because) of a system’s stated ideals. And perhaps we’re in another phase of finding out that the latest means of elevating humanity is simply enabling new and twisted manifestations of the same old problems.

Idealism loses many times over in Tango. And each time it deserves to. The traditionalists repress, the rebels create listless chaos, and Artur’s anti-rebellion leads to repression once again, but this time with even less meaning behind it. Yet when crudeness without idealism–reality without idea–wins, it’s even more horrifying. So what’s the answer? Is there an escape? Will Godot ever appear?

Tango proposes the pessimistic view. Yes, the endless generational cycles of rebellion and counter-rebellion can end. The search for meaning and selfhood can end. History can end–in nightmare. Perhaps that’s not a productive view to live by. Certainly one could write an entire other essay about the persistence of human virtue. But sometimes it is a view that is worth inhabiting for a while.

*

[1] And because, it must be said, I did not know Polish at the time I started the project. The two previous translations were both written in 1968. One is by Ralph Manheim and Teresa Dzieduscycka, published by Grove Press. It can still be found in print as part of The Mrożek Reader, or used. The other translation is by Nicholas Bethell and Tom Stoppard. It is not in print that I know of. I was able to find it used in the collection Three East European Plays. Both translations have their strengths and weaknesses. Overall though, I wasn’t a huge fan of either one. They each do the job in their own way, but I also found them to be a bit wordy in a way that blunted the tight, biting quality of the humor of the original. If I had to choose, I would lean towards the Bethell and Stoppard translation for reading and the Manheim and Dzieduscycka translation for performing.

[2] See Marketa Goetz Stankiewicz in “Slawomir Mrozek: Two Forms of the Absurd” for a good discussion of this. Both as it applies to Theater of the Absurd generally, and to Mrożek specifically. [jstor] [scribd]

[3] From Martin Esslin’s introduction to The Theater of the Absurd:

It must be stressed, however, that the dramatists whose work is here discussed do not form part of any self-proclaimed or self-conscious school or movement. On the contrary, each of the writers in question is an individual who regards himself as a lone outsider, cut off and isolated in his private world. Each has his own personal approach to both subject-matter and form; his own roots, sources, and background. If they also, very clearly and in spite of themselves, have a good deal in common, it is because their work most sensitively mirrors and reflects the preoccupations and anxieties, the emotions and thinking of many of their contemporaries in the Western world.

[4] From Stankiewicz, “Slawomir Mrozek: Two Forms of the Absurd”:

to the Warsaw audience Ionesco and Beckett are felt to be political writers. Their characters, like Mrozek's slogan-spouting little men, are seen as victims of a specific way of life forced upon them. The ‘enemy’ can be identified, or rather he is discovered, while the laughter still echoes through the theater.

[5] Take this from The Captive Mind by Czesław Miłosz, describing the mental shock of conquest in WW2 Poland:

[A man’s] first stroll along a street littered with glass from bomb-shattered windows shakes his faith in the ‘naturalness’ of his world. The wind scatters papers from hastily evacuated offices, papers labeled ‘Confidential’ or ‘Top Secret’ that evoke visions of safes, keys, conferences, couriers, and secretaries. Now the wind blows them through the street for anyone to read…he stops before a house split in half by a bomb, the privacy of people's homes—the family smells, the warmth of the beehive life, the furniture preserving the memory of loves and hatreds—cut open to public view…overnight money loses its value and becomes a meaningless mass of printed paper….Once, had he stumbled upon a corpse on the street, he would have called the police…Now he knows he must avoid the dark body lying in the gutter, and refrain from asking unnecessary questions…Everyone ceases to care about formalities, so that marriage, for example, comes to mean little more than living together....Respectable citizens used to regard banditry as a crime. Today, bank robbers are heroes because the money they steal is destined for the Underground….The nearness of death destroys shame. Men and women…copulate in public, on the small bit of ground surrounded by barbed wire—their last home on earth.

[6] See Daniel Gerould’s interpretation from The Mrożek Reader:

Tango takes the family as a microsociety, or scale model, for studying the history of modern Europe. The disintegration of the three different generations of the farcical Stomil clan, each representing a further step in the historical debacle, charts the decline and fall of European civilization from turn-of-the-century liberalism through interwar avant-garde experimentation to the present-day triumph of totalitarianism. By the use of parody and allusion (citations come from Shakespeare and the Polish romantic and modernist traditions), Mrozek creates a multi-layered work—a museum of modern European art, manners, and morals—which serves as a prism for viewing the relations of culture to power and for assessing the intelligentsia’s responsibility for glorifying force as the ultimate value.

[7] The Bald Soprano by Eugène Ionesco, trans. Donald M. Allen.

[8] Even compared to much of Mrożek’s work prior to Tango.

[9] Written in 1901, Wesele (or “The Wedding”) is one of the preeminent works of Polish theater. It tells the story of a wedding party celebrating the mixed-class marriage of a young city poet to a peasant girl. The party is made up of guests from all walks of Polish life, and they mingle uneasily over the course of the night. Ghosts from Polish history and mythology appear, exacerbating the social tensions.

[10] See The Captive Mind for a description of the experience of living in a political and intellectual atmosphere in which Soviet dialectical materialism was the dominant philosophy. It’s difficult to pick any one particular quote, but here are a couple:

Dialectics is the ‘logic of contradictions’ applicable, according to the wise men, to those cases where formal logic is inadequate, namely to phenomena in motion. Because human concepts as well as the phenomena observed by men are in motion, ‘contradictions contained in the concepts are but reflections, or translations into the language of thought, of those contradictions which are contained in the phenomena.’ [...] The Method exerts a magnetic influence on contemporary man because it alone emphasizes, as has never before been done, the fluidity and interdependence of phenomena. Since the people of the twentieth century find themselves in social circumstances where even the dullest mind can see that ‘naturalness’ is being replaced by fluidity and interdependence, thinking in categories of motion seems to be the surest means of seizing reality in the act. The Method is mysterious; no one understands it completely–but that merely enhances its magic power. Its elasticity, as exploited by the Russians, who do not possess the virtue of moderation, can result at times in the most painful edicts. Nevertheless, history shows us that a healthy, reasoning mind was rarely an effective guide through the labyrinth of human affairs. The Method profits from the discoveries of Marx and Engels, from their moral indignation, and from the tactics of their successors who have denied the rightness of moral indignation. It is like a snake, which is undoubtedly a dialectical creature: ‘Daddy, does a snake have a tail?’ asked the little boy. ‘Nothing but a tail,’ answered the father. This leads to unlimited possibilities, for the tail can begin at any point.

Paradoxical as it may seem, it is this subjective impotence that convinces the intellectual that the one Method is right. Everything proves it is right. Dialectics: I predict the house will burn; then I pour gasoline over the stove. The house burns; my prediction is fulfilled. Dialectics: I predict that a work of art incompatible with socialist realism will be worthless. Then I place the artist in conditions in which such a work is worthless. My prediction is fulfilled.

*

SOURCES

This list is not academically exhaustive, and isn’t trying to be. I was limited by what I could read in five months–both in terms of personal interest and ability, and in terms of what I could get access to. But it should give a general idea re: what has informed this post.

Plays & Fiction:

The Bald Soprano (Eugène Ionesco, trans. Donald M. Allen), The Lesson (Eugène Ionesco, trans. Donald M. Allen), Waiting for Godot (Samuel Beckett), Endgame (Samuel Beckett), The Maids (Jean Genet, trans. Bernard Frechtman), Tango (Sławomir Mrożek, trans. Ralph Manheim and Teresa Dzieduscycka, trans. Nicholas Bethell and Tom Stoppard), The Police (Sławomir Mrożek, trans. Nicholas Bethell), The Elephant (Sławomir Mrożek, trans. Konrad Syrop), The Memorandum (Václav Havel, trans. Vera Blackwell), The Horse (Julius Hay, trans. Peter Hay), Hamlet (William Shakespeare), Macbeth (William Shakespeare), Pygmalion (George Bernard Shaw), The Wedding (Stanisław Wyspiański, trans. Noel Clark), The Marriage (Witold Gombrowicz, trans. Louis Iribarne), Dziady, Part III (Adam Mickiewicz, trans. Google, trans. Count Potocki of Montalk), The Moon is Down (John Steinbeck), Crime and Punishment (Fyodor Dostoyevsky, trans. David McDuff), War and Peace (Leo Tolstoy, trans. Louise and Aylmer Maude), 1984 (George Orwell), Chekhov: The Major Plays (Anton Chekhov, trans. Ann Dunnigan)

Filmed adaptations:

Tango (1999, dir. Maciej Englert), Wesele (1972, dir. Andrzej Wajda), Wesele (2019, dir. Wawrzyniec Kostrzewski), Dziady (1997, dir. Jan Englert), Ślub (1992, dir. Jerzy Jarocki)

Non-fiction:

Anonymous, trans. Philip Boehm. A Woman in Berlin. 1954.

Juliette Bretan.“‘Life Makes Most Sense at the Height of Nonsense’: Interwar Polish Absurdism.” October 2020. [link]

Jan Bończa-Szabłowski. “The young one spoils everything.” November 3, 2010. [link]

Robert Brustein. “Foreword”, Chekhov: The Major Plays. 1982.

Michał Bujanowicz. “On Sławomir Mrożek - Playwright’s Tango.” April 2004. [link]

Michael Childers. “The Direction and Presentation of Tango.” 1977. [link]

Martin Esslin. Theater of the Absurd, Third Edition. 2001.

Martin Esslin. “Introduction,” Three East European Plays. 1970.

Daniel Gerould. “Introduction: Mrożek for the Twenty-First Century,” The Mrożek Reader. 2004.

Eugenia Semyonovna Ginzburg, trans. Paul Stevenson and Max Hayward. Journey Into the Whirlwind. 1967.

Malwina Głowacka. “Tango.” Więź, No. 11. November 1, 1997. [link]

Joanna Godlewska. “Tango.” Przegląd Powszechny, No. 9. 1997. [link]

Jacek Kopciński. “Sleep and awakening.” March 2019. [link]

Jan Kott, trans. L. Krzyzanowski. “Introduction: Face and Grimace, ” The Marriage. 1969.

Janusz R. Kowalczyk. “Tender Irony.” Rzeczpospolita, No. 14. June 19, 1997. [link]

Magnus J. Kryński. “Mrozek, Tango, and an American Campus.” The Polish Review, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Spring, 1970). [jstor]

Keith Lowe. Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II. 2012.

Wojciech Majcherek. “The Last ‘Tango’ in Warsaw.” Express Wieczorny, No. 140. June 17, 1997. [link]

Czesław Miłosz, trans. Jane Zielonko. The Captive Mind. 1953.

Michael C. O’Neill. “A Collage of History in the Form of Mrozek’s Tango.” The Polish Review, Vol. 28, No. 2 (1983). [jstor]

Jerzy Peterkiewicz. “Introduction: The Straw Man at a Wedding,” The Wedding. 1998.

Jacek Sieradzki. “The author of ‘Tango’ dances with us.” Polityka, No. 37. September 13, 1997. [link]

Marketa Goetz Stankiewicz. “Slawomir Mrozek: Two Forms of the Absurd”. Contemporary Literature

Vol. 12, No. 2 (Spring, 1971). [jstor] [scribd]

Mardi Valgemae. “Allegory of the Absurd: An Examination of Four East European Plays.” Comparative Drama, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Spring 1971). [jstor]

Jacek Wakar. “Great ‘Tango’ for the opening of a new stage.” Życie Warszawy. June 16, 1997. [link]

Piotr Zaremba. “Important ‘Wedding’ Anno domini 2019.” February 19, 2019. [link]

“Tango.” FilmPolski.pl. [link]

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

it was not on wheat...

#my art#my comics#og post#hold up i got one more image to add to this#sorry for the block of handwritten text lol i needed it to be kinda messy

92K notes

·

View notes

Text

i promised you 🦋

(crossposting from x, bsky, & ig)

#i don’t know how to tag on tumblr#only crossposting this here bc it was posted without permission#jayvik#jayvik nation#arcane#jayce talis#viktor arcane#league of legends#jayce x viktor#arcane fanart#2d animation#my art

55K notes

·

View notes

Text

(Based in this post)

Happy Pokemon day!! If youre a johto starter you either get isekai’d or become french

#wow foop posting art on main this is revolutionary#foopart#pokemon#pokemon legends arceus#pokemon legends za#chikorita#totodile#tepig#cyndaquil

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinda wanna do more characters in this style it’s so silly and fun

Edit: And i did :)

🦔 🐈 🦇 🦔 🐝 🦎 🐊 | 🦔 👧| 🦔 🦊 | 🦔 🤖 | 🥚🪨 | 🦅🐦⬛🪿 |

#my art#art#sketches#sth#sonic the hedgehog#shadow the hedgehog#sonic#digital art#miles tails prower#tails the fox#knuckles the echidna#I don’t have anything else to post 😔#busy days#EDIT#accidentally posted the transparent version oopsie#1k#5k#10k#20k#30k#40k

49K notes

·

View notes