writing is hard. let's make it easier. tip series editing services and prices

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Power of Silence in Dialogue

We often think of dialogue as something that’s just about what characters say, but let’s talk about what they don’t say. Silence can be one of the most powerful tools in your writing toolbox. Here’s why:

1. The Unspoken Tension

When characters leave things unsaid, it adds layers to their interactions. Silence can create a tension that’s so thick you could cut it with a knife. It shows things are happening beneath the surface—the real conversation is happening in what’s left unspoken.

Example:

“So, you’re leaving, huh?” He didn’t look up from the table, his fingers tracing the rim of his glass, slow and deliberate. “Yeah.” “Guess I should’ve expected this.” (Silence.) “You’re not mad?” “I’m not mad,” she said, but the way her voice broke was louder than anything she'd said all night.

2. Building Anticipation or Drama

Sometimes silence can heighten the drama, creating a pause where the reader feels like something big is about to happen. You don’t always need words to convey that sense of dread or anticipation.

Example:

They stood there, side by side, staring at the door that had just closed behind him. “You should’ve stopped him.” She didn’t answer. “You should’ve said something.” The room felt colder. “I couldn’t.” (Silence.)

3. Creating Emotional Impact

Sometimes, saying nothing can have the biggest emotional punch. Silence gives the reader a chance to interpret the scene, to sit with the feelings that aren’t being voiced.

Example:

He opened the letter and read it. And then, without saying a word, he folded it back up and placed it in the drawer. His fingers lingered on the wood for a long time before he closed it slowly, too slowly. “Are you okay?” He didn’t answer.

TL;DR

Silence isn’t just a pause between dialogue—it’s a powerful tool for deepening emotional tension, building anticipation, and revealing character. Next time you write a scene, ask yourself: what isn’t being said? And how can that silence say more than the words ever could?

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

advice for a character who grips control like a lifeline. who wants to be in charge of every little thing because whenever they're not in control of something something bad could happen. has happened. they can't let a single variable be wild or in someone else's hands

How to Write a Controlling Character

Backstory Rooted in Trauma or Guilt

This character likely has a history that has ingrained the belief that they must be in control or face devastating consequences. Perhaps they once trusted someone else with something crucial—a promise, a responsibility, or a life-altering choice—and that trust was broken in a way that had lasting repercussions. For example, maybe they lost someone because they weren’t “careful enough,” or they experienced a betrayal when they trusted another person’s plan.

They might frequently flash back to this moment, possibly catching themselves thinking, If only I’d been the one in control, this wouldn’t have happened. This memory fuels their need to keep a tight grip on everything, especially if they’re in high-stakes situations.

Rigid Daily Routines and Habits

This character’s day is probably packed with small rituals and routines that give them a sense of security. From double-checking door locks to setting multiple alarms, they rely on routines to give themselves a sense of order. In fact, they might be nearly ritualistic about small actions—checking emails three times before sending, never leaving a task halfway finished, or meticulously arranging their workspace.

Even something as simple as making coffee can become a precise process. If someone moves one of their tools or a file from their desk, they may feel a spike of frustration or even anxiety, seeing it as a disruption to their personal “system.” They could feel that control in their daily life is the only thing keeping chaos at bay.

Intensely Observant of Details and Mistakes

They are hyperaware of mistakes or inefficiencies in others, mentally cataloging things like a coworker’s slight lateness or a friend’s disorganization. They may feel a sense of superiority (or frustration) over people who don’t “have it together” and take it upon themselves to organize or “fix” things for others.

In conversation, they might cut people off or “correct” them even over small points, often justifying this to themselves as necessary. For instance, if someone shares a plan that seems half-formed, this character could immediately dive in, pointing out potential problems or filling in details.

Controlling Relationships and Social Situations

This character struggles in relationships where they aren’t the dominant or organizing force. They might instinctively take over when making plans with friends, micromanaging even casual hangouts to make sure everything goes “right.” For example, they might pick the restaurant, plan the travel route, and check weather forecasts—assuming that if they don’t, no one else will think of these things.

When someone resists their attempts at control, they can respond defensively, often turning cold or resentful, unable to understand why anyone wouldn’t want them to manage the situation. Statements like, “Fine, but don’t blame me if this doesn’t go well,” are frequent in their interactions.

Extreme Anxiety or Panic When Control Is Taken Away

When things go beyond their reach, this character might experience panic, as if they’re suddenly powerless. For instance, if an unexpected roadblock prevents them from handling a task (like a canceled flight they needed to board, or a plan that falls apart), they might spend hours trying to regain control, calling every contact or frantically exploring alternatives.

Their reaction may feel extreme to others. Even minor setbacks—such as a colleague taking initiative on a project or a friend planning something without consulting them—can trigger a disproportionate response, like clenching their fists, pacing, or silently stewing as they feel the situation “slipping.”

Inability to Accept Help or Collaboration

Their controlling nature makes it hard for them to collaborate, as they believe their methods are the only ones that work. For them, accepting help feels like an admission of weakness or failure, so they rarely delegate or ask for assistance. If they do reluctantly accept help, they are constantly supervising or “suggesting” things, making it feel more like they’re still in charge.

In a team setting, they might take on all the major tasks, either out of distrust in others’ abilities or a feeling that no one will match their standards. Their motto could be something like, “If you want something done right, do it yourself,” even if that means working late or burning out.

Reluctance to Show Vulnerability or Need

Since vulnerability and control rarely coexist for them, they avoid showing weakness at all costs, preferring to mask stress or struggles as “just part of the job.” If they do become overwhelmed, they’re more likely to shut people out, saying, “I’ve got it handled,” even if it’s far from true.

When people push them to let go or share the load, they might lash out, accusing others of “just not understanding.” They often see their intense responsibility as a form of sacrifice, justifying their behavior with, “If I don’t handle this, who will?”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Tip - How To Make Fight Scenes Interesting

More writing tips

So, when it comes to writing fight scenes, as I have done quite a few of them, there's some things I keep in mind.

Ensure Consistent Character Abilities: Characters should fight consistently throughout the scene. They shouldn’t magically become stronger or weaker without a clear reason. Consistency in their abilities helps maintain believability.

Avoid Making Heroes Invincible: I prefer not to portray heroes as invulnerable, as seen in many 80s action movies. Instead, I include moments where the hero gets hit, shows visible injuries, and shows fatigue. This makes them feel more human and improves the significance of their victories. It’s hard to create a sense of urgency if the characters don’t seem to be in real danger.

Portray Antagonists as Competent: I avoid depicting random cannon fodder as foolish by having them attack one at a time or easily get knocked out. Instead, I show them employing smart tactics such as ganging up on the hero and even getting back up after being knocked down.

Incorporate the Environment: Don’t forget to include the surroundings. Whether the fight takes place in a cramped alley, on a rain-soaked rooftop, or in a collapsing building, use the environment creatively. Characters can use objects as weapons, find cover, or struggle against challenging terrain.

Highlight Self-Inflicted Pain: Characters can hurt themselves just as much as their opponents. For instance, after landing a powerful right hook, a character might need to pause and shake off their hand in pain. This not only adds realism but also highlights the toll that fighting takes on the body.

Show Consequences After the Fight: Consider what happens after the battle concludes. Do injuries slow the hero down and limit their abilities for the rest of the story?

These are just a few tips for now. I am planning to release more tips on how I write my fight scenes with some examples included. See you then!

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

But Bryn, why don’t you want to hear negative feedback regarding your published novel?

Isn’t feedback important for a writer’s growth?

I want to preface: this isn’t a response to any of my reviewers in any way. It’s just something I didn’t think about until I got around to publishing, and I imagine many other writers and readers are the same.

So, why don’t most published authors bother trying to learn from their negative reviews?

Publishing a professional quality book takes a long time. For traditional publishing, it can be years after the writer picks up an agent. Self publishing often requires the writer to go through all the things the traditional publish would do, only they do it all on their own, so that too can take a long time.

This often means that writers will have written one, even two or three novels between the time they write the rough draft of their first novel and the time they publish it. (I wrote 100k words, ran two beta round, and edited a novella, just between the time I formatted OBP for print and actually put it on amazon.)

In this time period, a writer who’s actively striving to grow can learn a lot — a lot they would have liked to implement into the book they’re publishing, but can’t.

Often, reading those negative reviews doesn’t actually teach them anything they didn’t already learn themselves months ago. It just makes them feel like they let readers down by publishing too soon.

And the catch is: this never changes. A truly good writer never stops learning and growing and improving, and never stops believing that, hey, if they’d just rewritten that book one more time, maybe it wouldn’t have those issues they only learned how to spot two months after it went to the proofreader.

The negative aspects of reviews aren’t meant for the writer — they’re meant for potential readers. So don’t fret if your author friends don’t want to read that awesome constructive criticism you put together for their published works.

(Or maybe they will, especially if its a serially released work, and that’s awesome too!)

630 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Make Readers Care About Your Plot

It's a funny little trick, really. Because the truth is readers don’t care about your plot.

They care about how your plot affects your characters. (Ah ha!)

You can have as many betrayals, breakups, fights, CIA conspiracies, evil warlords, double-crossings, sudden bouts of amnesia, comas, and flaming meteors racing directly toward Manhattan as you want.

But if readers don’t understand how those events will impact:

A character they care about

That character’s goal

The consequences of the event, whether positive or devastating

…then you may as well be shooting off firecrackers in an empty gymnasium.

Why Plot Without Character Falls Flat

Here’s an example:

A school burns down. Oh my god, the flames! The carnage! The dead and injured children! There are police everywhere—total chaos!

And your main character? Standing on the sidewalk, watching and crying.

Dramatic? Sure. But does the reader care? Not really. There’s no emotional connection, so it's basically a meaningless plot point.

Plot + Character Impact = Reader Investment

Now, let’s take the same event but give it stakes.

Meet Mary Ann. Mary Ann has been a middle school teacher for 25 years. This year, she gets a new student—Indigo. An unusual girl with clear troubles at home and a habit of burning things.

Mary Ann defends Indigo when the school administration wants to expel her, citing safety concerns. Mary Ann sees something familiar in Indigo—something that reminds her of her own sister, who was institutionalized as a child.

One day, Indigo explodes in rage, screaming, “Burn it down! I’ll burn this whole place down!”

Mary Ann is shaken. This isn’t just defiance—this is a real threat. She nearly sides with the administration but, haunted by her sister’s fate, fights for Indigo’s second chance.

Indigo is placed in counseling. A compromise that will hopefully solve the problem.

That night, Mary Ann sleeps soundly. She did the right thing. Didn’t she? But the next morning, on her drive to school, the radio blares an emergency bulletin. There's a fire at the school.

Mary Ann speeds through red lights. Her stomach twists. When she arrives… it’s too late.

Oh my god, the flames! The carnage! The dead and injured children!

The exact same plot point—but now it matters.

How to Make Your Plot Matter to Readers

The secret? Before you set something on fire (literally or figuratively), give your character—and thus your reader—a stake in the outcome.

1. Tie Events to Character Desires and Fears.

Why does this event matter to this character?

How does it challenge their values, beliefs, or personal history?

2. Make the Conflict Personal.

The fire isn’t just a disaster—it’s a gut-punch because Mary Ann fought for Indigo.

The outcome isn’t just tragic—it’s haunted by Mary Ann’s past regrets.

3. Show Consequences.

Readers need to feel what’s at stake before, during, and after the event.

The weight of the aftermath makes the plot stick in the reader’s mind.

The result? Higher engagement, deeper emotional connection, and a plot that actually matters.

Summary: It’s Not About the Events—It’s About the Impact on Your Characters

I used a fire in this example, but this applies to any plot development.

Even something subtle—a whispered secret, an unread letter, a missed train—can have devastating emotional weight if it affects your character in a meaningful way.

Make your readers care about your plot by making your character care about it first.

Hope this helps!

/ / / / /

@theliteraryarchitect is a writing advice blog run by me, Bucket Siler, a writer and developmental editor. For more writing help, download my Free Resource Library for Fiction Writers, join my email list, or check out my book The Complete Guide to Self-Editing for Fiction Writers.

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

Repetition is one of the most marked features of all poetry. The incantatory magic of poetry has something to do with recurrence, things coming back to us in time, sometimes the same way, sometimes differently. Meaning accrues through repetition.

Edward Hirsch, A Poet's Glossary

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

YOU’RE STILL A WRITER IF:

you don’t write every day or every week

you haven’t been able to write in a few months

this is your first story or your hundredth

you never finish a book

you are completely unpublished

All you gotta do is write!

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Not an Editing “Tip.”

(Just a tool that might help clean up your writing and create a faster paced reading experience.)

Removing excess words. If you don’t need particular words, why keep them?

Another crashing wave sends me into a sprawl, and I’m forced to use my tides a few more times to distance myself from the rocks.

I should drop down as deep[er] as I can manage [and] use the reef for cover.

I can’t tear my eyes away until he disappears fully from view.

A burst of lightning shows the outline[s] of the cliff side.

A loud thud from the port window makes me jump, drawing my full attention. -> I jump at a loud thud from the port window.

Showing instead of telling. Making the reader feel what the protagonist feels is almost always better than telling them the protagonist is undergoing something.

I can’t believe the sight I see. -> My lungs catch painfully, a shocked squeak rising out.

Everything is slick and wet. -> The slick metal offers no hold for my wet hands. I clench my fingers until the ridges bite into my scales, shark teeth holding me in place. Agonizing.

Removing passive voice. Active voice is more engaging and should be always be used unless you have a specific reason not to use it for that sentence.

The rock is a muddled, dark brown, and I almost miss him amid the lofty coastline. -> I almost miss him against the muddled, dark brown rock, his body tiny amid the lofty coastline.

Her voice is strained and furious. -> Fury strains her voice.

The wound is closed again, but before it closed, enough blood seeped out that I now feel woozy and off kilter. -> The wound closed while I slept, but enough blood seeped out that my head still spin, my limbs heavy.

Always remember though: you have to do what works best for that particular moment. Some scenes require different strokes than others. Use your best judgement, and take pride in your personal writing style.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick Tip on Giving Characters Flaws:

Turn their best qualities completely upside down. Turn those traits around on them. They’re compassionate? Maybe they’re way too easily forgiving and get screwed over by it repeatedly. Extremely outgoing and extroverted? Maybe they’re apathetic to those who struggle with even having small talk, and make those people highly uncomfortable. Brave? Maybe they can be reckless and often get themselves in unnecessary danger.

Don’t sprinkle in flaws at the end. Base them on something. They should enhance your character and make them more three-dimensional. They shouldn’t be an afterthought, and the goal shouldn’t be to make your characters “relatable”.

9K notes

·

View notes

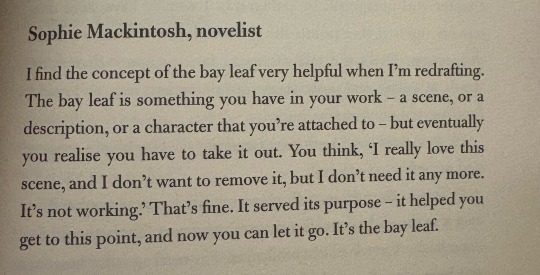

Text

This from In Writing, a collection of writers reflecting on practice, really resonated with me.

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

The latest initiative I’ve been working on with my colleagues at the Federation of BC Writers—and although the programming will be on Pacific time, it is open to writers everywhere. I’m going to be one of the mentors.

WHAT'S INCLUDED:

6 open mics

7+ accountability check-ins

3 workshops

4 story sessions

40+ writing sprints at different times of the day and days of the week

a private, moderated community to work through challenges, cheer each other on, and engage in writerly conversation

planning sessions to help you get started

a web-based point system to keep you motivated (with prizes)

access to workshop recordings, articles, and motivational posts

a wrap-up party

certificate of completion

(Prices are in Canadian $, which translates to a big discount for Americans!)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I started up one of my writing sessions yesterday, and my mind couldn’t help but wander a bit. I figured that other writers (or any creatives for that matter) could benefit from a little advice, and a little reminder:

Save your older work.

Even if you’re new to your craft, or if you’ve been at it for years and years, don’t delete/get rid of your older work if you don’t have to.

When I started writing, I wrote anything and everything that came to mind. I let the ideas flow and put the pen to the page. But later on, when I looked back at it, I thought that it was bad. Cringy. Awful. And I deleted them entirely.

Sure, some of them were pretty dang bad. (Not every story’s going to be great.) But let me tell you, for some of those stories, I massively regret deleting them. Even if they were bad, cringy, and awful, they were still stories that I had written. Stories that had good concepts at their core, or neat ideas sprinkled throughout the tales.

I wish that I kept those stories, no matter how bad I thought they were at the time. Maybe those ideas just needed more polishing to really allow them to shine. Or maybe they could’ve been put to better use in a different story.

You might think that your old work is bad, and you might want to get rid of it entirely, but don’t. Look at your old work, and if there are things that you want to keep, or things that you want to change, take note of them. Maybe your ideas were better suited for something else, or maybe the concepts could be better executed with your current skill level.

We cringe at our old work because we may think it’s badly done. Maybe it was. But you may also be viewing it from a standpoint where you’re more skilled in your craft than you were when you first created your work. You can more easily see the flaws and imperfections that you couldn’t see before.

Look back at your old work and see how you’ve grown since then.

See what you did right. See what could’ve used some improvement.

Don’t throw out things entirely if you don’t have to. Even if you think they’re bad now, there could still be diamonds in the rough hiding in plain sight.

And give your past self some credit. They made an attempt. They did it the best way they knew how. And hey, you could learn a thing or two from them once in a while.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate I when I get an idea for a novel. Like oh no here starts the slow sad slip n’ slide to dissapointment again.

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

Encouragment for writers that I know seems discouraging at first but I promise it’s motivational-

• Those emotional scenes you’ve planned will never be as good on page as they are in your head. To YOU. Your audience, however, is eating it up. Just because you can’t articulate the emotion of a scene to your satisfaction doesn’t mean it’s not impacting the reader.

• Sometimes a sentence, a paragraph, or even a whole scene will not be salvagable. Either it wasn’t necessary to the story to begin with, or you can put it to the side and re-write it later, but for now it’s gotta go. It doesn’t make you a bad writer to have to trim, it makes you a good writer to know to trim.

• There are several stories just like yours. And that’s okay, there’s no story in existence of completely original concepts. What makes your story “original” is that it’s yours. No one else can write your story the way you can.

• You have writing weaknesses. Everyone does. But don’t accept your writing weaknesses as unchanging facts about yourself. Don’t be content with being crap at description, dialogue, world building, etc. Writers that are comfortable being crap at things won’t improve, and that’s not you. It’s going to burn, but work that muscle. I promise you’ll like the outcome.

39K notes

·

View notes

Text

A lot of fiction these days reads as if—as I saw Peter Raleigh put it the other day, and as I’ve discussed it before—the author is trying to describe a video playing in their mind. Often there is little or no interiority. Scenes play out in “real time” without summary. First-person POV stories describe things the character can’t see, but a distant camera could. There’s an overemphasis on characters’ outfits and facial expressions, including my personal pet peeve: the “reaction shot round-up” in which we get a description of every character’s reaction to something as if a camera was cutting between sitcom actors.

When I talk with other creative writing professors, we all seem to agree that interiority is disappearing. Even in first-person POV stories, younger writers often skip describing their character’s hopes, dreams, fears, thoughts, memories, or reactions. This trend is hardly limited to young writers though. I was speaking to an editor yesterday who agreed interiority has largely vanished from commercial fiction, and I think you increasingly notice its absence even in works shelved as “literary fiction.” When interiority does appear on the page, it is often brief and redundant with the dialogue and action. All of this is a great shame. Interiority is perhaps the prime example of an advantage prose as a medium holds over other artforms.

fascinated by this article, "Turning Off the TV in Your Mind," about the influences of visual narratives on writing prose narratives. i def notice the two things i excerpted above in fanfic, which i guess makes even more sense as most of the fic i read is for tv and film. i will also be thinking about its discussion of time in prose - i think that's something i often struggle with and i will try to be more conscious of the differences between screen and page next time i'm writing.

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Editing Your Novel Part 1: Before You Edit

New Year, new edits! Editing is a big task to tackle, no matter how you go about it. Chunking it into several parts gives you a much easier set of goals to meet, methods to track those goals, and ways to make an impossible project more manageable.

The First Rule of Editing: Love Your Draft.

If you hate everything you wrote, you are not ready to edit it yet. If you feel as if you'd rather drive off a cliff than reread the work you've just done, put that book away for a few more weeks. If you can't stand your work, you aren't going to be able to give it the care it deserves. That feeling will go away, trust me. You just need to give it some time to rest.

Pre-Editing Prep Steps:

Change the Format - Changing your font will help you see your wards in a new way and the most common tip is to use comic sans. You might resist this tip. You might refuse on the basis that it is a silly font meant for silly jokes. But just try it out and see if it works for you. You can always switch to Arial like a coward if you want.

Read it Out Loud - No, you don't have to listen to the sound of your own voice (though if you're a theater kid, they might be a great way to work out kinks in your dialogue). There's plenty of decent screen-readers out there that will help. NVDA Screen Reader is a free program anyone can use. Google TalkBack is pre-installed in most Android devices, and Microsoft Word has a feature called Read Aloud that will drive you crazy after awhile, but works.

Outline What You Have - If you wrote your first draft based on nothing but feels or had an outline that took a sharp left turn at Timbuktu, re-outlining what you're looking at can help you work out how to tackle your edit. Now, you don't have to go all out - I'm a big fan of using flashcards to track scenes. They're easy to swap out and update when you change things, and you can lay them out in any organization to get good overview of your plot.

Take some time to get organized, and check into the next post when we talk about the plot pass!

226 notes

·

View notes