Text

instagram

PGX lead singer Hannah co-hosts a two-part radio show on South Island rock music featuring our EP on its entirety as well as some classic legends like The Clean, Snapper, The Chills, The Great Unwashed, and even bands that didn’t feature Peter Gutteridge

#christchurch#new zealand#south island#meltedicecream#flying nun#music#dunedin#peter gutteridge#the clean#the great unwashed#Instagram

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Well, New Zealand is now sealed off from the rest of the world and New Zealanders are sealed off from anyone not in their homes.

Since I can’t hang with my band, I figured I’d start making some web episodes dedicated to our time together so far.

Episode 1: Do not put your pregnant best friend guitarist behind the camera.

https://thisispgx.bandcamp.com/

0 notes

Photo

Two hours to lockdown... three types of whiskey. News on in the background. Label boss and I to become one organism. #covid_19 #christchurch #newzealand #lockdown #stayinthebubble #meltedicecream #pgx @meltedicecreamier (at Christchurch, New Zealand) https://www.instagram.com/p/B-JuN0YAUzB/?igshid=q6uck5c6krg3

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Advantages of your drummer’s bus back to Dunedin being cancelled after playing @pennylane_records: Thursday morning brunch slash band summit (at Lemon Tree Cafe) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9my5oRJ0nx/?igshid=uvelc78yosgh

0 notes

Photo

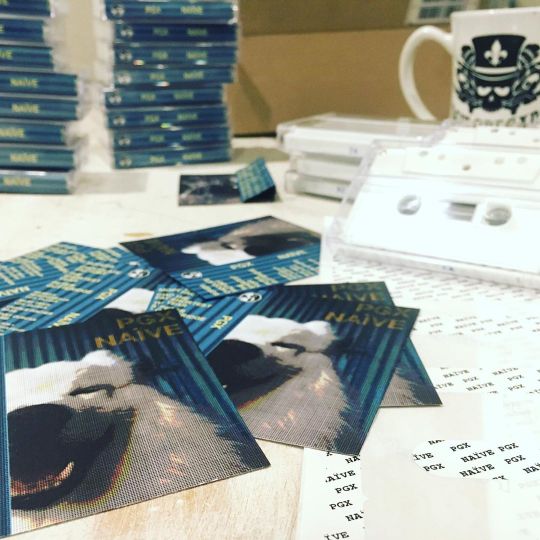

Debut EP cassette assembly in progress. Fueled by chai tea, the bevvy of champions #christchurch #islandlife #meltedicecream #imissmydog https://thisispgx.bandcamp.com (at Christchurch, New Zealand) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9jAYEvg_oa/?igshid=4g2l76p05y8x

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

Favourite thing in the world: playing at The Crown Hotel, seeing all our friends in Dunedin, snacking on Jonesies’ pies at 1am #dunedinnz #gig #allgirlrock #killingtime

0 notes

Photo

Recording drum and bass tracks for second @pgxtheband EP with @ryan_fisherman. Might get around to releasing the first one. Bring on 2020. #christchurch #newzealand #meltedicecream #rockandroll #islandlife #timetokill (at Christchurch, New Zealand) https://www.instagram.com/p/B7XtpllAe7a/?igshid=6jcdeds4nqn

0 notes

Photo

Drummer and record label boss slash flatmate slash brother from another mother hashing out band bio for the first PGX EP... not really though. Mostly just drinking wine. @pgxtheband @meltedicecreamier (at Christchurch, New Zealand) https://www.instagram.com/p/B7Ng-5-AAYr/?igshid=6y7eu10mz45b

0 notes

Text

New Years in New Zealand

Christmas belongs to the northern hemisphere. But on New Years Eve, there is nowhere better to be than New Zealand.

So many holidays seem backwards in New Zealand. For one, I’ll never get used to sipping Chardonnay on a deck drenched in summer sunshine on Christmas Day. Christmas belongs in the northern hemisphere, where you gather because it’s cold, bask in company to stave off winter’s depression, and wrap yourselves in blankets while opening presents.

My niece (supported by my hiding sister) and nephew, Christmas in Libertyville, Illinois, 2008.

But New Years Eve only makes sense in New Zealand.

“I never miss a New Years in New Zealand,” I told the American professor sitting next to me on the December 28 flight to Auckland from Chicago, who was headed to a conference in Otago. As my flight took off I had promised a friend in the Midwest I would try and get a photo of what it felt like to spent New Years in New Zealand with my friends.

“Where are you going?” the professor asked.

“Auckland,” I replied, unable to suppress a smile as I said it.

View of the Auckland skyline at sunset from the Waiheke Ferry, 2007.

“I wrote a novel about the friends I met within weeks of moving there 15 years ago,” I said. “I’m pretty much headed straight to them.”

A few of the stars of my novel at my 21st birthday party, with the inspiration for Jack in the center at Flat 56 in Auckland, 2005.

“Your second family,” she said.

I smiled wry. “What designates who comes first? Chronology or hierarchy?”

I may have been born in Chicago, but I found myself in New Zealand. Yet when people think of New Zealand, they often think of visuals like this.

Sunset in Opononi over the Tasman Sea, North Island of New Zealand, 2008.

Yet landscape photos of New Zealand don’t really capture the experiences I’ve had. My friends in New Zealand don’t like rugby and they don’t climb mountains. My friends are Antipodean urban rats. Some of the best times I’ve ever have been prowling K Road with Matt, who goes by Karma Chaos when dressed in drag.

One of my favourite photos of Karma Chaos kicking ass while performing on K Road, 2007.

Often I would take the stage alongside him, pantomiming on the guitar I dragged around ever since leaving Illinois but at the time rarely plugged in.

Doing some back-up guitarist for Karma Chaos at Wigarama, Family Bar, on Karangahape Road, Auckland, 2007.

Matt is so full of life and adventure at the time I thought I would spend a wild few months with him and then watch him dance off into the sunset, our paths never to cross again. I was wrong. Our friendship is one of the longest and most loyal I’ve ever had. When Matt got married in 2015, I was the photographer.

Matt and Gian on their wedding day in Auckland, 2015.

By the time I landed Matt and Gian were already in Whangamata, about two hours outside of Auckland. There is something about the air in Auckland that I sense as soon as I step off the plane. It speaks to me: You are exactly where you are supposed to be. Your life is about to change in ways you could never imagine, but only if you let it.

Rather than roll straight off the 16-hour flight and onto a bus, I spent a day in urban solitude, acclimatising to the city’s rhythms.

When I turned off Kitchener Street, my spirit still lifts at the sight of the massive tree branches that seem defy gravity and turn the pathway into Albert Park into a tunnel.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Hannah Herchenbach (@highwhitesound) on Dec 30, 2019 at 3:40pm PST

Inside the park, a couple snuggled under one of the trees against the Sky Tower, which many Aucklanders hate--especially those who remember the city without--but I always loved its single spire cutting through the sky.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Hannah Herchenbach (@highwhitesound) on Dec 30, 2019 at 3:45pm PST

After journalling against a tree I grabbed a few pieces of sushi at my favourite spot on High Street and headed to the Tepid Baths for some sauna and swimming sets, backstroking as the sun streamed onto the water through the skylights. They’re a bit fussy about photos in there so I didn’t whip my phone out, but here’s an image from NewsHub to get a sense of what it feels like. In your imagination, add some rows of bunting in primary colours; floating past them on your back is such a relaxing sight.

(To be fair, the photo is from an article about the pools being closed due to a legionella outbreak; no place is perfect).

On my way back to Britomart, it was winter and midnight in Chicago, where I had been not 24 hours before. In Auckland, it was seven pm on a summer’s evening; people were sunning in the grass downtown as the sun set behind the buildings.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Hannah Herchenbach (@highwhitesound) on Dec 30, 2019 at 3:26pm PST

Fifteen years on, I still marvelled: I can’t believe this place exists.

After waking up on New Years Eve, I stopped by the Tepid Baths again before getting on the bus to Whangamata around noon. I could have dried, straightened, and styled my hair. But also, fuck it.

Gian picked me up in Thames and we rolled across the Coromandel Peninsula to Whangamata. Eleven of us were staying in a house that Lucas had been given to live in as part of his job working for Water Care, which was how he was getting his permanent residency. Technically speaking, it was a bach, which is shorthand in New Zealand for “a few planks thrown together, no heating, little electricity, and not much thought put into it.”

When New Zealand wants to publicise itself, it shows off landscapes. It does not show the houses. Gian and I cast our eyes over the sign that had been spray-painted on a plank of wood leaning against the deck.

“Happy new year bithes?” we mused.

Matt was grinning from ear to ear inside, a drink lodged in his hand. “Happy New Year bitches!” he cried. “Did you see the sign? Did you spot it?”

“It’s missing a C,” I said.

“I KNEW you would notice,” he replied. “Yulie did it.”

“My English isn’t very good!” Yulie cried. She had moved over from Russia two years ago and had no intention of going back. Long may it last, she said of her time in New Zealand. Residency dependent.

“It’s our new name for our crew!” Matt cried. “We are The Bithes!”

Matt frowned at the sight of my air-dried hair and fresh face. “You don’t style yourself at all when you’re not with me,” he cried.

“I’m not going to not go swimming just to impress you, Matt,” I replied.

Matt pulled at my hair, applied eyeshadow, called for lipstick. He stepped back. “There! Now you look like you have a home! God, you looked like we picked you up off the side of the ROAD!”

I smiled. “Yeah, and you know why I do it? ‘Cause I know you’ll always pick me up anyway.”

Matt sighed. “True.” He put a final piece of hair into place. “Now you look how you’re supposed to: like a rock star.”

Gian and Lucas fussed in the kitchen over potatoes and lamb and ham that Matt glazed. Another contrast to the few New Zealand cultural cliches is that my friends are also rarely from New Zealand. Matt came over from the UK as a kid. His partner Gian is from Brazil. As we ate, we marvelled how amongst the crew of 11, only three were from New Zealand. We were born all over the world: Brazil, Poland, Russia, the UK, the United States, Zimbabwe. Yet we had all met in New Zealand. We crossed paths through looking for the same thing: adventure, freedom, presence, joie de vivre.

This is not unusual. As of 2016, 39% of the people in Auckland are foreign-born migrants, making Auckland more diverse than New York or London.

“Never done it before,” Matt said of the glaze. It was beautiful, we all agreed.

As the night wore on, none of the photos of New Years Eve quite captured that free-spirited feeling of being in New Zealand that I envisioned. We could have been having a dance party anywhere, hair slowly getting messed, irises growing wider by the minute.

Matt and I held each other and marvelled at our 15 years of friendship. The last New Years I had spent with him was one decade ago: 2009 rolling into 2010, before moving to the South Island.

“This year, we return to the stage,” Matt insisted.

“Fuck yes,” I agreed. “We’ll write some more songs, too.” Our band had finished one song but written parts of another dozen and had about 17 hypothetical albums, most of which were only titles.

Somewhere around 4.30am I fell into a horizontal position, leaving Gian in the hands of Matt and Grant. Gian thought he was on K Road. Matt and Grant had plenty of questions for him.

“I’m going to Family Bar,” Gian said.

“Okay,” Matt replied, calm as. “You go ahead. I’ll be there in five minutes.

Gian didn’t move.

“Wait,” Matt said. “What about the guys we were going to sleep with?”

Gian thought for a minute. “They’re at Hannah’s.”

Matt and I looked at each other. “Who is?”

“The guys from Grindr.”

“All of them?” we marvelled.

“No.” Gian paused. “Some of them.”

“How many?” Matt pressed.

Gian hesitated. “Twenty.”

Matt and I doubled over in laughter. “Twenty?”

The room started to stir sometime in the afternoon. Lucas, Antony, and Gian drew us to the beach, which was a five-minute walk away. It was a New Years Day tradition in Brazil to jump seven waves for good luck.

New Years Day 2020, Whangamata Beach, New Zealand

We walked towards the water in a line and jumped seven together, calling out the numbers as they passed.

“Now nothing bad will happen this year,” Antony said.

Afterwards we dove under the waves, splashed, doggy paddled, and floated on our backs.

“The North Island is a different country!” I cried. Try relaxing in the water in a bikini on the South Island. Get back to me once the feeling returns in your feet. I give it a week.

I insisted on a portrait of Matt and Gian on the beach, four years on from their wedding.

Matt and Gian at Whangamata Beach, 1 January 2020

Everyone else was staying in Whangamata for another five days, but as much as I love the party lifestyle, I cannot stay. It was time to return to the South Island. Yet after some strife in Chicago, I was relaxed, refreshed, ready to return to the PhD. My sacral chakra had opened. Auckland was within me.

My last afternoon we headed to a waterfall that had slowed to a trickle due to months without rain. Still, the pools were deep enough for cannonballs. I sat in the shallows between the pools and tried one last time for the photo. Ashley surfaced in the water behind me as I panned.

“Smile, Ashley,” I said as I moved the phone in her direction. “This is a panoramic shot.”

“Ah!” she cried, mouth open, trying to move out of the way as I passed.

“Kind of like Lord of the Rings,” we mused.

“That image is going to haunt me,” Antony said, zooming in.

Nailed it.

0 notes

Text

Is music a coping mechanism for loneliness?

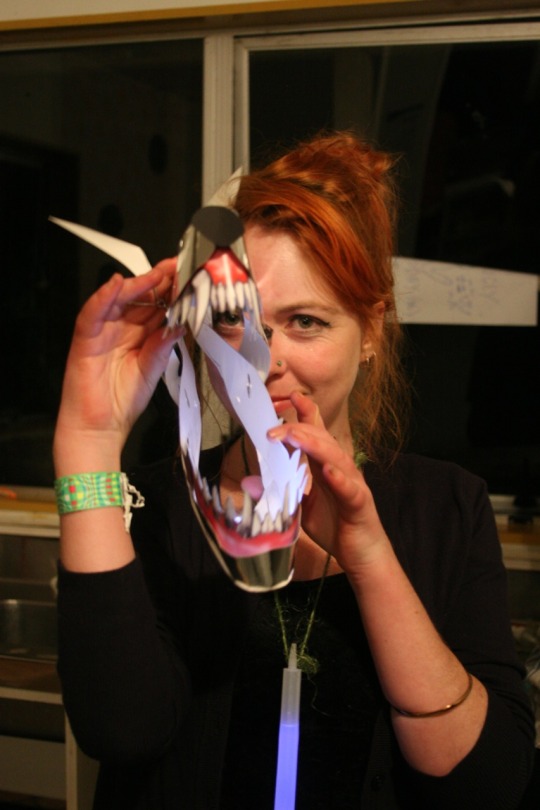

In the past, moments of social anxiety would transform the darkroom into a place where I felt like everyone was outside, smoking and laughing the night away under a starry night sky, making new friends, finding old ones, having a far greater time than I.

Me and the bandmates trying to keep it together at the darkroom in Christchurch, New Zealand. February 2018. Photograph by Stuart Page.

“You are good at psychology,” my bandmate Mary said. “Keep going with that.”

“I’m thinking of leaning into that in my PhD,” I replied. “Scarcity,” I laughed. “I’m obsessed with social processes. How do people figure this stuff out?”

But the 43 oral histories that I have done with musicians over the last three years for my PhD on South Island rock music culture have started to change that perception that I’m the only one out in the cold, watching the party go on without me.

These oral histories had all kinds of rhythms. There was elation and speed and resonance with a musician who moved a mile a minute. There was hesitance and long pauses and unspoken subtexts with one I dated, who insisted seven years ago when I moved up to Christchurch that he would never follow. Some had a languid pace and relaxed presence; they took their time forming their thoughts and sentences. Others’ minds moved in circles; they repeated phrases, and adding a thousand verbal tics.

All of them were so different, but there was one common thread: everyone cringes when they read their transcript. As the interviewer, I’m no exception. Even though I was supposed to be paying attention to the musicians, I couldn’t escape my own presence, always there, taking up half of the air. You would think each one would get better in subsequent order. They didn’t.

When I spoke with one of Peter Gutteridge’s best friends, who I have grown close to in the years since writing my dissertation, our exchange was warm, sly, and present. But when I interviewed a musician my own age who I didn’t know well, but whose songs I loved, my tone was stiff and uncertain from the first words on the recording.

“Ugh,” I thought listening back. “I sound so lame.”

Somewhere in the middle of the 43 I started introducing myself first in the files, even though the whole point of the recording is archiving their narrative in the national library. “That’s so narcissistic,” I winced.

Psychology has always fascinated me. What are our hidden brains, really? What controls our behaviour and kneecaps us without us noticing, despite our best intentions? I devoured the pop psychology books that dominated the New York Times’ bestseller lists, glancing over the anecdotes and lingering on the cherry picked social science observations.

While doing his PhD at Stanford in 1974, Mark Snyder found that the people who most easily charm strangers are high self monitors. They modulate their own tone and rhythms to match that of their companion, and thus put them at ease. Meanwhile it took me at least 30 minutes to match the conversational rhythm of a musician who talked in complete paragraphs. For ages I would try to get a few words in, totally oblivious that they needed no encouragement to continue. Typing back every misstep was painful, to say the least.

I used to think that people who performed music must be naturally extroverted. After all, playing live music involves being up a stage and asking people to watch you do something. Yet, many of the musicians I talked to said being on stage was the only time that they ever behaved like that. They weren’t dazzling each other outside smoking like I had thought. Or at least they didn’t think so. Many of them said they hated talking to people at the bar. They didn’t like the atmosphere at bars, or social outings. Many rarely went to gigs other than their own.

The Violet Ohs at the darkroom in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Before getting to know so many musicians, I classified myself as a geek who stayed at home, and put musicians in another box; one that was far more cool and admirable. It was only after getting to know so many that I realised that technically, if geeks are the people who stay at home and only focus on what they are into, then all the musicians I knew actually were geeks, too. If work is a way to act on the world, as Marx said, then writing and music are both work. And in fact, geeks are the ones who become great. Then, lots of people who are a lot less patient flood the parties that the geeks sneak out of.

Over the last year, the return to the guitar that I had spent so much time with as a teenager in the Chicago suburbs, has gone slow. At times, it has been painstaking.

“Imagine that was something awesome,” I said dryly at one band practice last winter after suggesting the idea of an instrumental part for Forever American. We all laughed. Afterwards, I wanted to work on the opening so that I didn’t have to bleat out two tones and ask my friends to imagine something better just happened.

“You don’t have to try so hard,” my flatmate Brian said as I stared at the laminated cards I made on theory that outlined where every note was on the guitar.

I looked up. “What do you mean?”

“You can change a section of a song just by having a different pedal. It will give it a completely different feel.”

“So, instead of changing how you structure the chord on the guitar, you change… the pedal and keep it where it is?”

“The technique is not just for arranging,” Brian said. “It’s for writing, too. You’ll write different things with a pedal, because you can hear things like harmonics. I’ve written things that wouldn’t make any sense on a clean guitar.”

“Hmm,” I said.

Brian demonstrated by arpeggiating notes up and down the fretboard for a bit. It was lovely. “I don’t know what I’m doing,” he said as he set the guitar back down. “I just know it sounds nice.”

Over the year it occurred to me that the people who take the time to learn how to play music and write songs must spend a lot of time alone. In order to get good, musicians have to like being alone.

Being alone has always been a preference for me, too. Despite being one of six kids, my first memory is being two years old and sitting on the floor of our basement, playing on my own, waiting for my older brother and sister to come home. Some might interpret that memory as sad or lonely. But I wasn’t cold. I wasn’t scared. I wasn’t hungry. I was perfectly happy entertaining myself. It’s not like it was a blueprint for my life or anything. The way I remembered it, I just happened to be alone.

Beautiful lights and beautiful people at the darkroom in Christchurch, New Zealand.

Sometimes I feel normal at the darkroom, and carry on a conversation as well as the next person. But sometimes, I feel like I can’t. Sometimes in the middle of a conversation my mind clicks out onto its own planet, far off in a distant galaxy of thought. Once there, I can only manage a word or two at a time. “Hey”. “How are you?” “Good.” “Yeah.” There was no controlling why or how or when it happened. Sometimes people would look at me strangely after something I said. The conversation halted in its tracks. It was as if I had dropped the ball or something. A beat was missing. I found it hard to recover after that.

One day a melody about the feeling floated into my mind as I crossed the street in Wellington.

Wel-come to the par-ty

at chateau anxiety

It was self-soothing, like a lullaby. It felt like something you could sing to turn the cold feeling of being frozen and distant into a celebratory, fun party of one.

“You just literally described every human being alive,” one musician said after I confessed the social anxieties that often crept up on me while out at gigs.

Did I, though?

One pattern stuck out high above the others in the oral histories. One of the first questions in an oral history is supposed to be essentially a box-ticking exercise: Please state your parents’ names, dates of birth, and where they were born, for the archives. But something surprised me. Many of the musicians couldn’t do it. Family histories were often troubled. A parent was often missing.

This year I upgraded from pop psychology to actual psychology journals. None of what I found was likely to be useful or valid. Rabbit holes, wrong methodology. Still, I was interested.

One study found that from the age of eight through to adulthood, people were more likely to offer support than they were to seek it from potential friends. Four and six-year-olds, however, were different. They made no distinction between offering and asking for help from friends and potential friends alike. They drew fewer distinctions between a friend and someone who potentially could be a friend.

Then I stumbled on attachment theory, which British psychiatrist John Bowlby came up with way back in the 1950s, but was new to me. His research demonstrated that the ability to sense and successfully regulate emotional states—both your own and others’—comes from reciprocal exchanges between infants and caregivers in the first 36 months of their life, which created secure attachment. Often these exchanges were made up of no more than wordless eye contact; this created limbic resonance. The “Strange Situation” studies that Bowlby’s colleague Dr. Mary Ainsworth and her protege Dr. Mary Main conducted between 1969–1999 found that only 55% of infants demonstrated secure attachment behaviours. Follow-up studies indicated that the patterns formed in these early starts stuck. For the rest of their lives, this half of the population would go on to have comfortable, relaxed, and confident social interactions where they felt in tune with others and easily made friends.

Everyone else—nearly half of all people—had parents who didn’t do this, for any number of reasons. They might have been distracted. The mother might have had postpartum depression. Their parents might have never gotten this sort of treatment themselves, and thus didn’t know how to do it, or that they should. Ed Tronick’s Still Face experiments from the 1970s demonstrated that when infants do not receive this reciprocal engagement, they withdrew from social interactions – with permanent consequences. This half of the population would go on to have trouble with committed relationships for the rest of their lives if the pattern went unchecked.

So, not everyone. But a lot.

What’s more, a whole third of the population could be categorised as avoidant attached. These people avoided or withdrew from emotional interaction with people under the guise of independence. Avoidant attached people like being near people they love, but once there, weren’t necessarily focussed on interacting with them. When considering the future prospects of their relationships, they were somewhat ambivalent.

In an interesting twist, avoidant attachment children might be indifferent towards their caregiver, but they are also more receptive to being comforted by just about anyone else who comes along. In weird ways, having parents who were emotionally unavailable in the first few months of your life makes you seek out the world. Again and again and again.

I can’t say for sure whether I’m avoidant attached, since I have very few memories of the first 36 months of my life. But all of the consequences resonated. And the odds were one in three.

In my own moment of pop psychology, it also reminded me of the atmosphere of a gig.

If my supervisors in the Sociology and Media, Film and Communications departments at the University of Otago knew how I was spending my time, they would probably be pulling their hair out. After all, wasn’t I supposed to be focussed on structural changes in music-making practices over the last 40 years? Ethically, should I be attempting to psychoanalyse the people who had been generous enough to grant an oral history for my PhD? How rude would that be? Should I really be thinking twice about whether or not the musicians preferred to spend time alone, or whether they had done that as a child? I am probably just projecting my own inner world onto everyone I see. Maybe I’m the only one who’s lonely.

How could I not take advantage of their generosity?

Perhaps I could give something back by sharing what I had read, and parts of myself as they had. Perhaps I could confess that I need help coming to terms with this, that I don’t know what I’m seeing, and I can’t figure it out on my own. Perhaps it would be somewhat more fair if I pushed past how it burns and hurts when I write. It’s like slicing skin off with the thinnest knife, and offering it up as sacrifice.

Wouldn’t that be fair, when people are giving you so much of themselves? Wouldn’t it be fair to do the same?

In the days following Celia’s death, I watched how her friends comforted each other. They all did a ton of supportive work in their statements. No matter what was said, they agreed and reinforced each other constantly. Meanwhile, I was cold and morose and silent in contrast. I refrained from disclosing things. I didn’t show my hand. I didn’t seek help or attention. Their behaviour fascinated me; at the same time it took months to dawn on a theoretical “why”: I struggle with observing, watching, and caring for others in a proactive way. Those behaviours do not come naturally. When it came to cultivating social emotions, mine seemed a bit dented or inhibited.

I didn’t want to be this way. I just didn’t know how to be any different.

But according to the research, no one is doomed. All of this can be worked out through quality time spent with secure friends. Apparently, sharing emotional states creates something akin to emotional object constancy, which can help manage anxiety and enable us to get on with living fulfilled, productive, connected lives.

Since learning this I have joked with my friend Martin Sagadin, who makes films and amazing music videos, that he must be part of the securely attached 55%, because he approaches every person who comes into his life with open arms.

youtube

Martin’s music video for Marlon Williams, ‘What’s Chasing You’ (2018)

In fact, this was how Martin and I became close friends. I had interviewed him for a magazine years prior, and knew him from behind the counter at Alice’s, the video rental store in town. One night he dreamed that we made a movie together, and that it was fun. So, we did.

The other day Martin and I caught up in Wellington, where he was attending a development workshop for his next film.

“How are your interviews going?” Martin asked.

I paused. “I fall in love with everyone as I do an oral history with them.”

Martin smiled. “Cool.”

0 notes

Text

Go well, Celia

The first time I saw Celia Mancini was on celluloid.

Three years ago, my flatmates and I headed out in the rain to catch a screening of Margaret Gordon’s documentary about the Christchurch band Into the Void at Alice’s, a theatre in the centre of town that holds about 30 people.

Most of the documentary consisted of the band laughing about how they drank together far more often than they made music.

But the atmosphere changed when a clip from King Loser’s ’76 Come Back Special video jumped off the screen. A presence appeared: a femme fatale with jet black hair and red lips. She sprinted in short heels through the streets of Auckland, picking off men with whatever she had lying around: a car, a rifle, a karate chop.

youtube

King Loser, ‘76 Come Back Special

“Wow,” I breathed.

Onto the next one... Still from the ‘76 Come Back Special video. Get it, Celia.

One of the people she murdered in the video was her bandmate Chris Heazlewood. Their personalities sparked when they met in Auckland in 1992. Celia spit venom, and Chris liked it. Celia liked him, too. King Loser was born shortly afterwards.

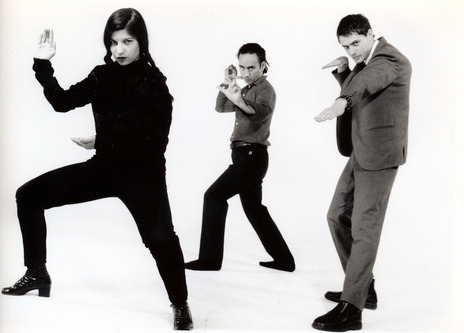

King Loser press shot for Flying Nun Records. Left to right: Celia Mancini, Lance Strickland, Chris Heazlewood. Not pictured: Sean O’Reilly

“That whole video was all her idea!” he cried. “She’s got a real good eye for iconography. She was like, ‘I need to be in a black vinyl catsuit, and I need to be killing everybody, and I need to die at the end.’”

Celia was larger than life. She was also still very much alive. Unlike the actual members of Into the Void, who were somewhat useless at remembering the finer details of their history, Celia had scrapbooks full of newspaper clippings. More than 20 years after the fact, she still had everything saved, as if she always knew that someone would need it one day. She was a rock star and an archivist. My heart glowed. As disparate as our lives seemed, I could relate to her in that one small way.

Media is often talked about as if it is some evil, homogenous lump of globalised ephemera with no real connection to anything or anyone other than capitalism and corporate profits. But in New Zealand, people step out of celluloid and cross over from the screen into everyday life all the time. You just have to know where to look, and who to find.

At one point in the documentary, Into the Void played in a gravel lot on High Street where their practise room used to be. One kid watched from the sidewalk, his hair bouncing. An hour after the screening, Mary and I were at the darkroom, and so was he.

“We just saw your movie,” we crooned. “Loved your scene.”

Though Celia first became known for her presence in Christchurch bands like The Stepford 5 and The Axel Grinders in the 80s, she didn’t live in Christchurch anymore.

(You can hear one of The Stepford 5′s songs here).

Although King Loser was born in Auckland, the band also lived in Dunedin for a bit. Part of that history included joining Peter Gutteridge in a reformed line-up of Snapper. The New Zealand poet David Merritt referred to their triumvirate as “an axis of good and evil”.

Self-portrait of Snapper, c. 1992 by Chris Heazlewood. Left to right: Peter Gutteridge, Celia Mancini, Chris Heazlewood. Not pictured: Mike Dooley.

Though their relationship didn’t last, they remained close friends.

Celia always used to introduce Chris to people with the line, “And this is my guitarist, Chris Heazlewood.” Photo courtesy of Chris Heazlewood, who said: “Note proprietary position of hand on shoulder.”

Celia’s and my paths first crossed two years ago in a bar on Karangahape Road in Auckland. Though I had killed a lot of time on K Road – I had written a novel there in another life, years before moving to the South Island – I had never seen Celia before. This time around, I was doing an oral history project on Peter Gutteridge. This time, I knew who I was looking for.

Chris Heazlewood was playing at the Audio Foundation, though I missed it (what gig finishes by ten?). Apparently, Celia appeared with a drummer and demanded that they play. Chris conceded. They smashed it.

After the show I ended up at Verona, and Celia was there too, in a black silk dress. Her arm was in a cast. One of her front teeth was chipped. The bar was loud and crowded. She talked with a drawl, and a bit under her breath. Her words rolled together like liquid and I couldn’t make out a thing she said. After a few moments she held up her cigarette and announced: “I’ll leave you for more conversation with this one.” She nodded to me. “Scintillating.” That I understood. I broke into a smile. I had just been insulted, but I didn’t care. She was funny.

Later that night a boy at the bar leaned in my face when he heard I was writing about Peter Gutteridge.

“Who?” the boy spat.

“He’s a musician,” I replied.

“Who?” he asked again, louder.

“Uh…” I tried to think of which band to mention first.

“I know who he is,” the boy seethed. “He was a friend of mine. Do you think he would have wanted you to write about him?”

He hit a nerve. I almost cried.

Celia wasn’t like that at all upon learning I wanted to write about Peter.

“I have no questions to ask you,” she said. “I’m just grateful.” She championed the project to several of their mutual friends, and put me in touch with all of them.

We did her oral history on a sunny winter day in Auckland in 2015. Celia didn’t have a permanent address, so we met at her friend’s flat in Grey Lynn.

Celia wanted food: she requested a pizza with anchovies, capers, and olives. I had a rockmelon. “Bring both if you can,” Celia said. Before I left, she doubled down. “I’m not joking about the rockmelon. I am half Indian, you know.”

When I arrived, Celia was waiting in the backyard.

“Hi!” I said as I approached. “I’m Hannah.”

She smiled slow. “I know.”

I had brought along the rockmelon, but by that point it had been long forgotten.

Oral histories ought to be recorded somewhere quiet, but Celia wanted to go find some sun.

“Lindsay, we need your keys,” Celia announced to her friend. “Hannah’s going to borrow your car.” It came off a bit abrupt, but Lindsay didn’t seem to mind. He tossed me his keys. I also needed power; he handed me eight rechargeable batteries and told me to keep them.

Boxes of Celia’s archives formed towers around Lindsay’s toilet. Even though she didn’t have a home, she hadn’t lost them. Her friends seemed unusually patient and generous.

As I drove, Celia drank.

“I'm a bit confused lately because I don’t live in Auckland,” Celia said. “I really want to be going home. I’ve been trying for two years.”

“Where’s home?” I asked.

She looked as me as if I was blind. “Dunedin!” she cried. “Always.”

We ended up on a park bench near the lake in Western Springs, where ducks were basking in the late afternoon sun.

Celia poured whiskey into a mug from her flask. “Would you like a drink, darling?” She doled out the word darling like candy.

“I would, but I can’t,” I protested. “I drove us here. I need to drive us home!”

Celia’s mind moved a mile a minute. As she talked, her words started to blur again, and I struggled to separate them, just like at the bar. My replies were flat. Most of the time I managed only a generic response once she had finished. “Oh. Hm.” I wondered if she was making any sense.

Later, when I listened back and slowed down the recording, Celia was totally lucid, and I sounded like an idiot. She would go off on three separate tangents in the middle of a sentence – but at the end of every sentence, she offered up about seven ideas.

Much of what Celia said blasted apart the two-dimensional statements that have been repeated so many times about rock music in New Zealand, they are often passed off as truisms. One is that the scene is full of amateurs who learned by the seat of their pants.

Celia didn’t ascribe to any of that bullshit. She loved classical music, played ragtime and honky-tonk on the piano from the age of five, and was a brass player in several orchestras as a kid.

And then she fucking rocked.

Another one of the two-dimensional truisms was that being on stage came with no pretence. Everyone wore street clothes.

Celia didn’t give a fuck about precedents. The world was her stage, and she was going to own it.

youtube

Celia and her band Mother Trucker performing ‘Eric Estrada’ in 1998.

“People turned their back on the audience,” Roy Colbert told me over coffee. “Then, here comes Celia walking the stage like it’s a runway in a nightie. People had never seen anything like it before. Jaws were on the floor.” Roy laughed.

Celia and I reminisced about Peter and purred.

“I miss his tone of voice,” she said.

“So gentle,” I agreed.

She smiled. “So sweet.”

Although our first encounter was a bit acerbic, Celia treated me like gold ever since I wrote about Peter. She said my dissertation rendered her speechless. A rarity, one of her friends mused. Don’t worry, another chimed in. I’m sure it’ll wear off soon. Her reputation remained contentious, but she also remembered my birthday.

About a year later, word spread that King Loser had started to play together again. Shows were scheduled across the islands for September. As the dates neared, rumours rumbled through Dunedin that communication in the band had started to break down. There was talk the band might not make it.

But they did—curiosity regarding their arrival turned into cries of lament from Port Chalmers that Celia had demanded the entire stage be moved at the last minute.

Danny and Nikolai of Elan Vital had been drinking at Mou to mourn its last day before being sold; a brief sojourn to pick them along the way turned into a two-hour detour.

“Have shots with us,” they pressed.

“I’ll have a beer; I can’t have shots though,” I said. “I really want us to make this show.”

That night outside the Tunnel Hotel, the atmosphere was giddy. Nikolai leapt at Danny and pulled down his pants. Renee was draped over the fence outside the hotel in a fur coat, eyes glistening and grin demented. King Loser was back.

Chris Heazlewood passed us on the street on the way in.

I lit up. “You made it!”

“Agh,” he muttered. “Dragged that bitch all the way from the top of the North Island to the bottom of the South...”

I smiled. “Well, we’re glad you did.”

The bar was packed. There were black leather miniskirts that looked like they had been dusted off from 20 years back.

There was no sign of Celia. Sometime after midnight, the band started to play without her. Eventually Celia stalked in an oversized fur coat from stage right. Her hair was teased and piled up a mile high over a white collared shirt buttoned up her neck and a black silk tie.

If looks could kill... Celia at The Tunnel Hotel in Port Chalmers, September 2016. Photo by Esta de Jong

Celia threw her coat behind her over a lamp. Their drummer—Lance Strickland, aka Tribal Thunder—carefully removed it.

Once they started playing, it all came together. Chris and Celia taunted one another. Lance was on point. At one point Celia almost knocked the keyboard into the audience, but Lance leapt out and caught it. Elan Vital and Death and the Maiden threw themselves into each other in front of the band, manic.

“I love you Celia!” Renee crowed.

“Another whiskey, please, somebody?” Celia posited to the audience.

“Somebody get her a whiskey!” Renee hollered, carrying the decibel of the request over to the bar.

“Thought she wasn’t going to make it for a minute there,” I mused to Roy Colbert, who happened to be standing in front of me.

“Don’t be fooled,” he said. “Celia wanted all eyes on her. She loved it.”

Word of King Loser quieted down a bit again after the shows.

The following summer I moved to North East Valley, and not long after that cycled past Chris Heazlewood walking a dog along North Road.

“King Loser is playing at the Crown this Sunday afternoon,” Chris said. “So, Celia’s down obviously.”

The cover charge was only five dollars. My whole flat came; those with a bit of extra money covered for the ones who couldn’t afford it.

By the time I arrived, Connie Benson was on her last song. Afterwards, King Loser were even tighter than before. There was no false starts, no long wait. The first song came like a bullet train. Wham! Celia introduced another. Wham! Then another came straight after, without any introduction. Wham!

youtube

King Loser kill it at The Crown Hotel in Dunedin, March 5, 2017.

“Shall we have Connie Benson come up and play our last song with us?” Celia asked before the set ended.

The crowd cheered. Connie’s eyes widened.

“Come on, Connie.” Celia started a chant. “Connie! Connie!”

Connie slowly took her guitar out of the case.

Connie glanced between Celia and Chris as the band launched into a riff. She watched Chris’ fingers and slowly started to imitate them. Lance lifted his chin at Connie, encouraging her to go faster.

Celia stopped the song after about 30 seconds. ““All right, Connie,” Celia insisted until the beast ground to a halt, it’s E, F#, A...” Celia rattled off the notes they were playing.

I melted for the girl for being put on the spot to play a song that she didn’t know. Connie didn’t seem to mind, though.

“Isn’t she amazing?” Celia asked the audience at the end. “Connie Benson!” I couldn't tell whether Celia had been trying to humiliate her, or not. Celia ran over to Connie after the set.

Celia Mancini performing a matinee King Loser show at The Crown Hotel in Dunedin, New Zealand, March 2017. Photo by Jacque Ruston.

“Man,” my flatmate Caitlin marvelled. “What do you think she is like in person?”

“I’ve met her a few times,” I said. “I think what you see is what you get.”

Caitlin wouldn’t have to wonder for long. That weekend, Celia turned up at our flatwarming in the valley with a small entourage round midnight.

Marcus apologised on her behalf. “You know Celia,” he said. “She wanted to make an entrance.”

“Doesn’t matter,” I smiled. “Come as you are, whenever you like.”

It was a great night. Celia insulted the music, the lighting, and everyone at the party straightaway.

“What is this?” Celia’s head swiveled. “You’re living in some student flat?”

Yes. But it has a band room...

Caitlin tried to tell her a joke. Celia didn’t let her finish. “I’ve got a joke!” she declared. Then she forgot the ending, and cracked herself up anyway.

Caitlin stared. “I’m laughing. Your joke is really funny.”

“Cunt!” Celia crowed.

Caitlin put an arm on her shoulder. “Celia. I’m glad you’re here. But this is my house…”

Celia had already moved onto the record player. I tried to apologise for Celia, but Caitlin didn’t care. “Oh, I think she decided I was all right in the end.”

“What is this music?” Celia cried. My flatmates had put on something... electronic. “Change it!” she hollered.

I was more hesitant. “Someone wanted to hear this...”

“Put something that you like on,” Celia insisted. “You have good taste.”

She had no knowledge of my taste, but was charming enough to get people to go along in spite of how little what was said stacked up against facts.

At one point she sallied up next to me as I messed around on the organ in our hall. “That’s really good,” she encouraged, her eyes locked onto mine.

Immediately after I put on some rock and roll, a boy started dancing in our lounge with a broom.

Celia smiled. “See?” She cranked up the volume.

“We have to keep it down,” my flatmate Icky insisted. “Noise control already came. I don’t want my stereo taken away.”

“The neighbours only called noise control because of that shithouse music you were playing before,” Celia insisted. “They didn’t like the BASS. It has to do with FREQUENCY. This is a higher frequency, it’s fine.” She cranked the volume back up on her way out to the backyard.

Icky stared after her. “I think I’m in love.” He turned it back down once she had left.

“This lighting is awful,” Celia mused. “Lighting can make or break a party.” We turned a few lights off. “Better,” she insisted.

“She wasn’t that bad,” my flatmate Jenny said later on. “She wasn’t causing drama for the sake of it. Everything she was saying was about trying to make the party better.”

Celia was still putting records on when I slithered off to bed around two in the morning. The next day my flatmates told me that she was one of the last to leave.

Our time together was so short when compared with those who loved her and spent decades by her side. Yet as her spirit drifts from the bottom of the South Island to the top of the North Island and flies out over Cape Reinga, it feels still like I ought to share the little that I knew. If there was a legacy to carry forwards from the short time I spent with Celia, it was to engage. Celia can be channeled anytime someone moves with a certain modus operandi: Pay no mind to precedents. Focus on making the music good. Improve the party.

I have been lucky enough to find something in New Zealand, though I can’t quite yet describe it. If all of the people who had an impact on each other’s lives all over these islands could be seen at once, it would light up the night like rich constellations in a cloudless winter sky. But as time passes, clouds are forming. The brightest lights are slowly fading, and some are disappearing altogether from sight.

Yesterday, another soft glowing star faded from the constellations that tell the story of a time and a place.

Go well, Celia.

Celia Mancini by Brigid Grigg-Eyley

#king loser#celia mancini#celia patel#flying nun#auckland#new zealand#music#legend#stepford 5#the axel grinders#rip

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

open mic at the darkroom #1

There used to seem like such a wide breach at the darkroom between watching a band and taking the stage.

There was only exception was when Brian hosted karaoke parties every now and then.

Brian Feary as his karaoke, quiz-night hosting alter ego Dr. Love in 2015.

“I threw up before the first time I played,” Brian volunteered.

I gasped. “Really?”

Last year when our band vowed to play in public by the end of the year, we needed somewhere to build up our confidence. The darkroom stage was one small step – a small box, really. It was nothing. Yet it felt like crossing a huge divide. The prerequisite for getting on the stage was a half-hour set of original material, and knowing a band well enough to be invited to open for them. If neither of those applied, you were in the audience.

Still from RDU footage of the Dunedin band The Violet Ohs at the darkroom in Christchurch, New Zealand, 2015.

We weren’t at that level yet, so we looked instead in the back pages of the Christchurch Mail for Open Mic listings.

The Christchurch Mail, January 2017. Orange circles aren’t open mics, but Anita and her band Devilish Mary and the Holy Rollers are really cool. The Ruby Suns are good, too.

Only certain bars had open mics. The Fitz, a sports bar on the fringe of the four avenues, had one where men in their 40s in leather jackets played Pink Floyd immaculately while another dozen people milled near the pool tables on the other side of the bar. When we took the stage, the few groups of people stopped what they were doing and watched curiously. After our 12-minute set, we toasted our complimentary pints of lager, high on the fumes of playing. Martin crowed about how the men in leather jackets were probably record executives who would tempt the band to break up, like villains. But it was all right. Nothing could break up the band. We would emerge unscathed, triumphant.

Geof smiled. “Martin has the right attitude about all of this.”

There is a similar feel at The Rockpool on Sunday nights, also known as Mickey Finn’s. Three-song, 15 minute sets.

The Rockpool in Christchurch, New Zealand, date unknown.

Some Open Mic nights required booking in advance, like Tuesdays at the Carlton. There was a nice spontaneity in the chalkboard at Jane’s Bar on Wednesdays. Come along, get up on stage. There the audience was warm and wonderful as you played, but individuals could be dicks. Before we played, two men in high-vis cornered our table and asked us to spread our legs.

Stuff like that never happened at the darkroom.

Too much loveliness in the darkroom, a twinkling bar in the middle of the post-apocalyptic industrial wasteland that is the eastern region of the four avenues in Christchurch, New Zealand. Photo from neatplaces,co.nz, c. 2011-2012

We never felt cornered into leering conversations we wished would go away. Perhaps that’s because attending a gig there requires an intention. Sometimes there was barely anyone there, sitting in the shadows, and it felt like you owned the place.

While this often is what makes the darkroom special, when our band had a booking in August and was no longer going to be in town to fill it, it felt like maybe we should worry.

“What if we did an open mic night?” Ray asked. “Do you think Marcus would mind?”

Marcus loved the idea. He had been experimenting with comedy as a different way of bringing people to the darkroom earlier in the night. That was another nice thing about open mics. Sign-ups were early in the evening; they tended to wind down by 10. It destroyed the cycle where people don’t show up early because they don’t want to wait around for the band to start playing, and that bands don’t start to play until people arrive.

“I’ve never done an open mic night before,” Marcus admitted.

“Usually performers get a free drink after playing,” I said. “Is it all right if I advertise that?”

“That’s fair,” Marcus agreed. “Though maybe next time I should make it buy one, get one free. At least that way I’ll make some money.”

“Oh I wouldn’t worry about that,” I assured him. “I’ve been to a few open mic nights. The free drink comes after they play, and everyone drinks beforehand.”

Mary threw together a poster.

A graphic designer would cry. But it got the message across.

Marcus changed the listing on the darkroom’s website to an open mic on Monday. We created a facebook page. The gig had about five days’ notice.

“I hope people come,” Mary said.

Our bassist Ray was with her sister in Sydney. “It would mean a lot to me if you were there with us,” I assured her girlfriend Amy. Once when we were half an hour late to Jane’s Bar, the owner had already cajoled Amy into being the first performer of the night. Amy hadn’t prepared a thing, but picked up the owner’s guitar anyway, and charmed the crowd effortlessly.

That night, I got back from Peter’s inquest right before we were due at the darkroom.��Mary and I arrived a few minutes before the night started at seven. Amy was already there with 10 of her classmates, drinking.

“They have been here for 20 minutes,” Marcus said.

More people arrived in groups of two and three. We parked ourselves by the door and explained how it worked to those who came in with instruments. The chalkboard was eight names deep half an hour in half past seven. I shrugged to Mary. “We might as well get this thing started.”

All we needed was for Marcus to turn on the sound. I squeezed my way to the bar.

“I’m kinda busy!” Marcus laughed as Abi manoeuvered around him with a pizza. “Give me five minutes?”

The Darkroom in Christchurch, New Zealand.

“No rush,” I smiled. “Whenever you are ready to get started, so are we.”

Mary and I called ourselves the ice breakers, thanked everyone for coming, and flashed off a quick three songs. The verses of Flowers stumbled a bit. Our timing did not match. “Our job is to set the bar low for you guys.” We gestured at our ankles. “Down there. Really comfortable.”

“I’m glad that’s over,” I said after we finished.

“That might have been your guys’ best set yet,” Geof said. “You were charming. Your voices didn’t quaver. Peter was powerful. You were there.”

Another two or three people arrived every five minutes.

By eight thirty, it seemed like every space in the darkroom had a guitar or someone sitting somewhere. “Mary,” I called to her through the sea of people. “Imagine if all of the guitars in this room were in a photo!”

It had grown so much bigger than Amy’s friends.

Maybe people have been waiting for something like this, I thought as I looked around the room. An intermediary step to getting on stage. One where you didn’t have to know the right bands to get onto the bill. Even if you could only nail one cover, you could get onstage and practice.

It’s a pretty sweet deal. Fifteen minutes of commitment, and you and your friends all get a free pint and some happy fumes.

Still, NASDA occupied the heart of the room. Someone from the performing arts school cycled on stage about one every three sets to reset the bar with something across three octaves or featuring three-part harmonies. Amy tried out a new stand-up routine about her summer stripping and killed it. Two NASDA kids borrowed my guitar.

“Ooh, it’s out of tune,” one said, stopping a few notes into her third song.

“It’s the G,” I called out to the stage.

“The G.” The sea of NASDA kids in front of her crooned the note. She fixed the string.

The NASDA kids tended to go by their first names. An Irish guy performed alone as Admiral Drowsy. One girl who came along with her guitar had been playing in bands around Christchurch since she was 12. Celia was born in Korea and grew up in Christchurch from the age of four. She lived in Auckland now, though. “I like it up there,” she said. She played under the name Tank Top. Her last gig was at the Audio Foundation.

I lit up. “I love that place! So underground.”

“It is underground.” She laughed. “Literally.”

Some of the people who played were longtime friends. Two girls hopped on stage with guitars and voices like liquid honey. Their harmonies blended beautifully.

“That was great!” I crowed to them as they packed. “Do you write your own stuff?”

“We haven’t had much time yet,” one of the girls said. “My friend just moved back from Queenstown!”

Others had only played together for a matter of weeks. One boy brought his rock band that played all of their own songs. The dynamics were wide and sweeping.

“They are great,” Geof conceded.

I thanked him for playing afterwards. He said the band had been together seven weeks.

“You wrote those songs seven weeks ago?” I asked.

“Yeah.” He beamed.

Some acts got on stage together after meeting minutes before.

“I have a cajon drum,” one guy said at nine. “If anyone needs a drummer.”

“Celia is up next,” I mused. She was to my left. “Hey Celia, would you like a drummer?”

“That could work,” she said. I stepped back. “Maybe my last two songs,” she told him. “They are the most... melodic.”

He watched her carefully during the first song and joined in. “Texture,” he said after he played. “That’s all that was needed.”

“How long have you been playing together?” I crooned to the stage after their first song ended.

“Three minutes?” the drummer replied.

She was only in town for the weekend for her mother's birthday, so it dissolved again in an instant.

At half past ten, all but half a dozen people vanished, like magic. A few minutes later, our flatmate Brian strode in.

“You missed it,” I told him. He had agreed to help us host. “Didn’t matter. We didn’t need your street cred.”

Abi laughed.

“Thank you for putting this on,” Celia said. She had found out about it the day before.

A few people said that.

"So many people were asking if we are going to do this again," Mary told Marcus.

"Already there," Marcus replied. He suggested a monthly thing.

“First Thursday is kinda taken. Third Thursday?” I asked.

“Whenever,” Marcus said.

"Can we... keep hosting it?" I asked tentatively.

"Of course!" he cried.

“Do you have any music online?” the drummer asked Celia.

She had one song on Bandcamp, she said. “But it’s not very good,” she quickly added. “I might take it down.”

“Don’t do that!” we cried. “Not before we hear it!” Mary got her number.

“How are we going to find him again?” I wondered of the drummer as he left.

“He’s Lyttelton. A local,” Mary said. “He’ll find us.”

0 notes

Text

What stories are yours?

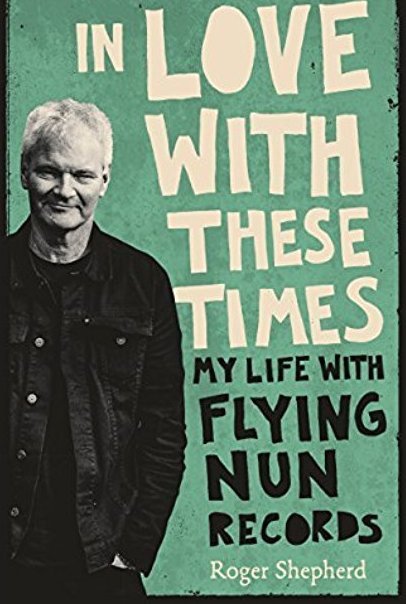

When the long-awaited memoir from Flying Nun record label boss Roger Shepherd came out last winter, I sat on my hands for a bit. On the one hand, it was highly relevant to my doctorate on the everyday lives of South Island rock musicians. On the other hand, the going rate for a new local paperback in New Zealand is forty dollars.

Cover of Flying Nun founder Roger Shepherd’s 2016 memoir

If the reviews were anything to go by, it seemed to be a pleasant, fast, well-written take on Christchurch and Dunedin in the early 1980s. Only one review took issue with the book, and the comments accused the author of being petty or vindictive for personal reasons. That review stood out the most, but for a different reason. It said the book told the “heartbreaking” story of Peter Gutteridge.

youtube

Peter very much alive, doing what he does best in the 1988 video for ‘Buddy’ directed by Stuart Page.

It’s a big word, heartbreaking. It’s hard to read when your heart did feel like it broke in half the day he died. And every time you remember, a little part of it breaks again.

After reading that review of Roger Shepherd’s memoir I sucked it up and bought a brand new copy for $36.99. It was a source of great hope. It was a beautiful chance to spend time with new pieces of Peter that may have not yet existed.

Roger didn’t write much about Peter in the early years of Flying Nun.

youtube

The beautifully simple, yet eminently hypnotic bassline at the heart of The Clean’s ‘Point That Thing Somewhere Else’ was written by Peter at the age of 17

There was one comment that made me smile: Roger wrote that Peter was good-looking, talented and smart.

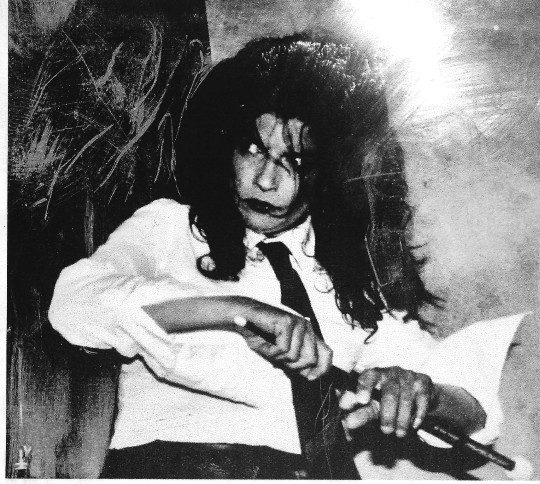

Photograph of Peter Gutteridge by Terry Moore, date unknown.

The end of the sentence, I liked less. Although Roger hadn’t seen Peter in his later years, there was four pages of anecdotal hearsay about the last weeks of Peter’s life. My tongue tasted black bile. I closed the book.

Anthropologists, ethnographers, sociologists and oral historians all stress the importance of reflection. There are so many places where your personal affections can colour what you are writing. The only way to get around that is to admit your bias and be as honest as you can.

There was an irony in the distaste as I read passages about Peter written by someone who had a lot more of an impact on his life than I did. After all, Roger was the person who made it possible for Peter’s music to be heard by the masses. What is my place in all of this? How could I feel more ownership than Roger Shepherd?

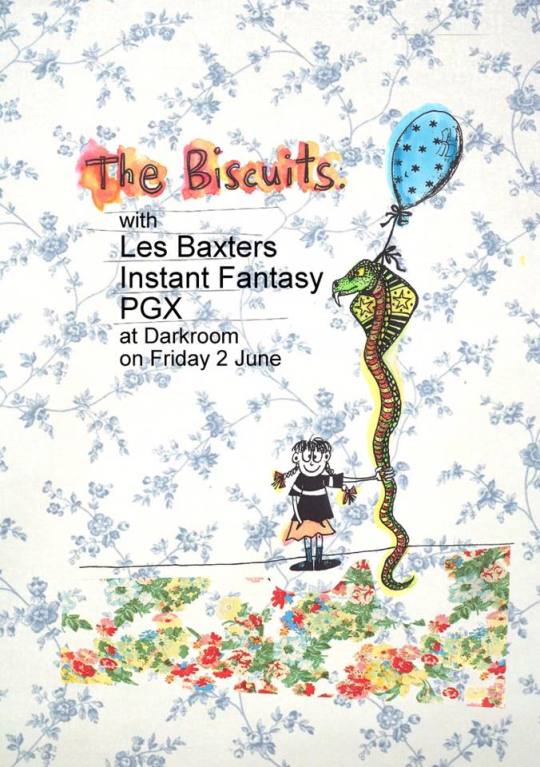

When we played our second show ever at the Crown Hotel in Dunedin in June, I thanked The Biscuits for inviting us on tour, and then thanked Brenda for our name.

“It was easy,” she replied from next to Dave. “Peter Gutteridge.”

Brenda had given us the name “PGX” as a placeholder when booking the tour after liking a song I wrote about Peter.

“I think PGX might stick,” Mary said the morning after our first show.

“The consonants are clack-y,” I agreed.

“P-G-X,” we chanted at the same time. Our eyes lit up. We did it again. P-G-X!

If you took away the context, PGX was fun and ambiguous and vague. It was better than The Expats. Mary hated that name. The consonants were good, but the context killed it – which as Mary put it went: “Hey, want to come see a local gig? We’re not from around here.”

It wasn’t hard to think about Peter when we played The Crown Hotel in Dunedin this winter. I had seen him play there many times. The place is still plastered with Snapper posters. There is a collage dedicated to Peter at the end of the bar.

youtube

Peter Gutteridge doing a guest spot in Chris Heazlewood’s band The Forty Winks at The Crown Hotel in Dunedin in 2012.

I thought maybe finishing our first tour would feel elating. Instead finishing with the song about Peter felt like shooting an arrow into the darkness and striking the black vein that runs through Dunedin. It was like ripping open your heart and holding it out still beating. People cheered, a bit. We thanked them. I was a wreck.

“What were you expecting?” my bandmates pressed.

I wasn’t expecting the black cloud to swallow my heart again three years on as quickly as it did.

When we first played the song back at Jane’s Bar in the Christchurch suburb of Linwood back in March, I said, “This is a song for Peter Gutteridge” and one guy in the back cried, “Yeah.”

I pointed my finger to the back of the bar. “Yes, sir.” I agreed. “That’s right.”

After the show, a woman clasped my hands and said that she knew Peter, and had been sent to the bar that night to hear my song.

In Dunedin, the room is different. Everyone in there has had an experience with Peter. It’s like the song is like, “Hey, remember this guy?” And everyone in the room goes, “Yeah, I do.” Real flat. “Thanks. Thanks for triggering that and dredging it all back up for us.”

Nikolai’s face was like stone in the front row. Erica walked up to me with tears streaming.

Erica and I met seven years back while on tour with the Wellington band Full Moon Fiasco around the South Island. Erica was the VJ; I was there to bear witness.

Erica adjusting the spinning wheel that she used for animations on Full Moon Fiasco’s winter 2010 South Island tour, Chicks Hotel, Dunedin, New Zealand, 20 August 2010.

That was the band that first introduced me to Dunedin as a band would see it, and the tales of Peter that less than six months later transformed into a friendship in a supermarket.

Three months later, Erica and I waded through the tall, wet grass that ran alongside Peter’s house to get close enough to holler through the kitchen window and get him to let us in. Peter wasn’t answering his door again, but that was normal. His house was long and thin.

Peter was home, and he loved Erica, who also performs under the name Lady Lazer Light. Of course he did. Peter stayed with Erica in Wellington years later, after Danny joined the reformed Snapper and they toured the North Island. At one point, Peter took everyone out on an elaborate quest for a pure source of drinking water after the tap water in Wellington did not appeal to him. Erica had last crossed paths with Peter on the streets of Wellington on her birthday a few months before his death. After he handed her a cross as a birthday present and said, “I can’t wear this anymore, but maybe you could,” she worried about him, a bit.

“I’m crying,” was all Erica said.

“Erica!” I wrapped her in a hug.

“I really liked your song.”

“Thank you.” We held each other, my guitar squeezed between us.

I told Nikolai about how the song had come into my head as I watched him play at Peter’s memorial.

He smiled. “Cool.”

We drank pitchers of black Speights until Jones nudged us out at two thirty in the morning.

At our departmental morning tea the following week, Peter Stapleton mentioned that he had seen our set. “You were great!”

“Really?” I smiled. “Thank you. I wasn’t sure how the Peter song would go down.”

“It was mixed,” he admitted. “I knew Peter. I was next to people who played with Peter.”

And who am I? I get it. They have no reason to care for an American talking about one of their friends.

That’s what we will always be, from the first word we speak, Mary and I agreed. American.

“Be careful there,” Winston insisted. “Keep yourself in check. You’re on their turf.”

“Maybe I shouldn’t play the song in Dunedin,” I mused.

“Oh no, you have to play it,” Winston said. “Always play it. That’s your tribute. Just don’t expect everyone to feel the same way that you do about it.”

Earlier this week the police’s version of the story was released as the inquest into Peter’s death in state care began.

This is a sick and twisted world, I thought at the grand photo of Peter below the district court where the inquest was taking place.

Phantom Billstickers poster of Peter Gutteridge photographed by Hayley Theyers, in the car park below Albert Street in Auckland, New Zealand, August 2017. And a little bit of Stuart Page, one of Peter’s best friends, in the lower left hand corner.

The lines between memory and myth are fuzzier than most people realise. What constitutes honesty when the same thing can be seen as either loyalty or clouding allegiance? Where does that boundary lie in a community that tells its own stories to itself a hundred times before they leave the islands?

Less than three hours after listening to Pure in a backyard in Grey Lynn I was back in Christchurch, heading to the darkroom. Our band originally had a gig, but when Mary and I ended up being the only members in town, we decided to turn it into an open mic night instead.

Ray’s girlfriend Amy had stacked the audience with classmates of hers from NASDA – song and dance theatre students with an average age of about 20. Her theatre background also made her feedback on our performances interesting. Before our Battle of the Bands heat, she talked about entering songs with presence, as an actor would assume a role they were to perform at the theatre.

“Before you sing a song, think: What do I want to achieve here?” Amy said. “Are you just singing a song, or are you channeling the feelings that you had when you wrote it?”

We only had to play 15 minutes to break the ice. The original plan was to do one or two of our own songs, but also set the tone by returning to some of our first covers.

youtube

Who doesn’t subconsciously know how to sing the chorus of Poison’s ‘Every Rose Has Its Thorn’, amirite?

But we hadn’t played those in years. I had forgotten the date the inquest began and raced off earlier in the week, leaving us no time to practice.

“What if we just did our songs?” I asked with minutes to go. “We’ve played them so many more times. We know those.”

Mary held up a few fingers. “Flowers. Merchant...”

“Let’s do Peter,” I said.

“I wasn’t sure if it was too soon...” Mary said hesitantly.

“No.” My stare was like ice. “I can do it.”

“All right,” I said after we rambled through a few songs last night. “This last one is for Peter Gutteridge. I don’t know if that name is familiar to any of you.”

No one said a word.

They listened politely.

We let it roar.

#new zealand#south island#christchurch#dunedin#flying nun#peter gutteridge#music#full moon fiasco#elan vital#lady lazer light

0 notes

Text

The importance of being bad at something

To borrow from Jane Austen: reader, our first show was a mess.

My guitar fell off its strap halfway through the first song. The crowd gasped as one as I caught it in my hand; my face in utter shock. I managed to keep singing, re-attach the strap, and start playing again.

Geof roared with laughter. “The front row would have gasped because they would have been watching your face,” he said. His work had sent him to Burma so he couldn’t make it. “Oh, god. I wish I could have seen it.”

youtube

Making it to the end of our first song opening for The Biscuits at the darkroom for their Rise 7″ release tour, June 2, 2017, Christchurch, New Zealand.

I highly recommend stacking an audience. When we climbed on stage at the darkroom together on a rainy winter night for the first time and plugged in, the bar was filled with our friends: geologists, government workers, architects. Their faces glowed in the lights as they crowded in front of the stage, beaming. They hollered and cheered no matter what we did. The solo we had chucked in at the last minute sounded awful the first two times through. When I finally got it right on the third try, the crowd roared.

Afterwards my tone was dry. “You’re very kind.”

One of my strings sounded off as we started our set the following night in Dunedin, even though I had just tuned it at the flat. But my amplifier was on and Ray was going. This is happening, I conceded. Hope my guitar isn’t too loud.

Shots like this are still so new to us, we are prone to crying things like “Hey! We look like a real band!” The Crown Hotel in Dunedin, New Zealand, June 3, 2017.

Mary had the same problem, but took a different perspective. She unplugged her guitar in the middle of one of our songs and ran across the stage to get her tuner and fix it.

“She is supposed to have that tuner plugged in!” Geof cried.

“Yeah, we know that,” I told him. “But Ray and I don’t have one, so she lets us borrow hers.”

A fiery red Mary at The Crown Hotel in Dunedin, June 3, 2017.

“It’s like a musical performance and an ad hoc comedy show,” Geof marveled. “Two shows for the price of one.”

“Let’s never show this to anyone,” Mary suggested after listening to the recording.

Most of the ethnography conducted by popular music scholars consists of standing around in bars, talking shit. This kind of behaviour is called “participant”. It has also been called out by other academics. “To what degree are you participating?” They challenge.

I had been so intimidated by the thought of getting on stage. Something you’ve never done can become so big in your head, you think it’ll feel different on the other side, too. All this expectation beforehand about jumping over your own shadow. Ten minutes later, you play and go, “Well… That was… mediocre.”

youtube

Two tones, two songs: PGX making it through Chocolate Factory and Flowers at the darkroom during our first ever gig, June 2, 2017 in Christchurch, New Zealand.

About seven years ago some Germans that I was flatting with in Wellington taught me the phrase ‘Über seinen schatten springen’, which directly translated means “to jump over one’s own shadow”.

Merlin practising bass on our front porch in Wellington, New Zealand, January 2010.

Merlin, Bennie and Justin preparing for the greatest band photo of all time on the roof of a shed in the backyard of our Northland flat in Wellington, New Zealand, January 2010.

There are a few different interpretations of the phrase. My flatmate Merlin felt that it meant to finally do something that you could always do, but for whatever reason had not yet. The reason was likely to be ridiculous as being afraid of one’s own shadow. When you at long last accomplished the simple task, you jumped over your own shadow. You got over yourself.

That was what it felt like after stepping off the stage at the darkroom. Nothing out of the ordinary happened after we had finished. The next performer met my gaze. “Great job,” she said as our paths crossed. That was something new. Other than that, it was just another night where I drank and talked to my friends at the darkroom. The fear that I had put upon the shadow had been wrong all along. This is all right, I thought. I can do this.

“Good job!” People said afterwards in Dunedin. No one discussed the notes. There was a new insight from playing. When people say “great job”, it’s not about the content. They are complimenting a behaviour. They mean great job getting up there.

“Yeah, your guitar playing is pretty average,” Nikolai said. He smiled. “Not really. That was what, only your second gig? You said you played last night?” He nodded. “It’s clear that it’s kinda raw, but the songwriting came through.”

“If you listen to our recordings of when we had only been together a few months,” the drummer of The Biscuits laughed. “We were clumsy.”

“It looked like so much fun!” Jason, the sound man at our Dunedin gig cried. “You are making me want to get back into music.”

“It is fun,” I conceded, smiling.

“I can’t wait to see you play now,” Geof said after hearing how bad it went. “This is what is going to make watching you guys fun. The crowd gets to watch you guys get better.”

“I can’t wait to come back in two years when you’ve played 500 shows and you’re absolutely smashing your core tunes,” our flatmate Winston said. He had studied jazz at MAINZ seven years ago, played in massive drum and bass bands, and was on the verge of leaving New Zealand to join his girlfriend in Europe. “Yeah. It’s gonna be awesome.”

“You have a lot of faith...” I said hesitantly.

“Oh, there’s no stopping you guys.” Winston’s tone was flat. “If something was going to, it already would have. I have seen bands crumble in a quarter of the time due to some egos.”

Last night I turned 33. Brian brought wood over from the West Coast and started a fire. I opened a bottle of wine.

“Should we try to write a song in a new key?” I wondered to Ray. She brought down her bass.

“Those will never sound good together,” Winston called from his room after a few half-hearted stabs at the piano that sat almost a full semitone out of tune. I sighed and turned to the guitar. That instrument where I could never quite see theory. It would be good to get away from the descending thirds I so loved on the piano.

Music demands patience. It never pays off to race ahead. Take the time to attend to the untuned string and think about the theory. Music is helping me balance. There is ritual, there is pacing, there is improvement. There is mindfulness.

“Ugh,” I said as I fiddled around with a few chord progressions in C minor.

“Stick to the major chords,” Ray suggested. The pattern had a nice consistence. “Try chucking a minor in there,” she added once I had cleanly done a few rounds.

I tried one and lit up. “You’re right! It’s interesting to your ears. Your ears are like, ‘Ooh, I expected a major third there.’ It’s a semitone down instead.”

I struggled to cleanly arpeggiate the G string on my bar chords and within a few minutes stopped to stretch my fingers. We both laughed.

“Come on, hand!” Ray said.

I smiled. “It’ll get there.”

0 notes

Text

Another birthday, same place

What does getting older mean?

When you are young, change comes at lightning speed. Milestones are mere months apart, from learning to walk, talk, read, vote and everything in between—the nature of the sun, geography, the heartburn of love unrequited, how to drive, the right to open credit cards, rent a car, buy porn and cigarettes. In comparison, milestones in your late twenties and thirties are far fewer and farther between.

Before moving to Christchurch five years ago, I had changed cities, neighbourhoods or just flats about every six months. Now I have lived not only in the same town, but the same flat for five years. I got a dog. My life is now filled with familiar beats and routines. What makes a year, then, when everything looks roughly the same from the one before?

Jarvis cools off in the South Pacific Ocean during a springtime trip to North New Brighton in Christchurch, New Zealand, October 2013.

Taken earlier that day? Nope, same location one year later, November 2014.

One of the risks of getting older is that your tolerance for being bad at something declines. This can be seen as a good thing; it suggests an appreciation of quality. Your taste is developing; your behaviour aligns with your evolving aesthetic preferences.

On the other hand, it can become a crutch that can encourage leaning too much on your strengths. The willingness to risk failure recedes. Your ego takes over. You fear the frustration of going back to square one and starting again.

That was what I admired about my best friend Mary. Although Mary and I are both American, we first crossed paths in Christchurch four years ago through TradeMe when Mary responded to our flatmate listing.

We killed a lot of time together.

Mary and I find Flat Man at a roller derby game in Christchurch, New Zealand, October 2013

Flat outing to watch the All Blacks smash France in Christchurch, New Zealand, November 2013

Mary and I in our best op shop threads headed off to a dance thrown by the Avon City Rock and Roll Club. Outfit coordinated to match Jarvis, who seems more impressed with Mary. Christchurch, New Zealand, September 2014

A few years back, Mary became inspired by her mother’s foray into guitar back in Pennsylvania and signed up for lessons in Christchurch. I watched as she sat in the lounge of our flat and struggled until her fingers formed habits. She was willing to be bad at something again, like a kid. Her comfort with her own vulnerability inspired me to pick up a guitar again, no longer frozen from having barely touched it for the last 10 years. I didn’t critique myself for being bad as I played with Mary. It reminded me that music is the most fun thing that two friends can do. I even relaxed enough to remember and show her the few things that I knew.

Hanging out with sisters, dogs, and guitars in Diamond Harbour, Christchurch, New Zealand, November 2014.

“You lost your inhibitions,” our flatmate Winston mused.

Mary and I wouldn’t necessarily play every week, but we would always meet up. That element of the ritual was religious. We poured glasses of hot water with lemon, red wine, or whiskey, depending on how we were feeling. We talked about life and love and loss and wrote down the bits that seemed to have a nice cadence. Sometimes we held our guitars, sometimes we forgot and just got drunk instead. We wrote dozens of pieces of songs and melodies, which gave us a glowing, happy buzz. We never bothered to finish any of them.