#instability theory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“I will not let your lack of curiosity deter my charity. I sought you out to relieve you of your regret, for once in your miserable life.” Yes! Miserable! He was miserable! His life was miserable. And in that moment he felt like he would die, for the chance to make Kaiba miserable, too: maybe he could abandon himself to the fast-festering violence inside him, and inflict a hurt that was finally worthwhile. Kaiba smirked as though he could read his every thought. Go on, he seemed to dare. And then the words echoed from the day before: I know you don’t have it in you.

Instability Theory

Kaiba’s declining mental state is jeopordising KaibaCorp’s most ambitious project yet. Jonouchi hasn’t seen his dad for weeks now and is starting to worry. They can probably help each other out, if they can get their issues out of the way first. A violet fairytale. Sci-Fi; Hurt/Comfort.

Read Chapter Three on Archive of Our Own.

Pairings: Jonouchi Katsuya & Kaiba Seto

Rating: Explicit

Warnings: This story is a dark one, so please beware. Future chapters will revolve around distressing subject matter concerning child abuse and CSA. This chapter is tagged for neglect, alcoholism and physical abuse.

Status: Chapter 3/?; 33,032 words.

Tags: daddy issues, rampant paranoia, sad boy saviour complex, malfunctioning virtual reality, hallucinations, enemies to lovers, fairytale allegories, strange dream sequences, bizarre dissociative internal monologues, marathon sex (eventually), canon inspired, character study

Playlist

New mix! As is custom, this is DJ mixed as a continuous set on Soundcloud and runs 104 minutes. Also indexed on Spotify for easier listening or folks that prefer that platform!

For lovers of: dark folk, darkwave, dreampop, electronica, post-punk, shoegaze, synthwave.

#yugioh#violetshipping#seto kaiba#puppyshipping#moonogre#joukai#kaijou#katsuya jounouchi#happy birthday jounouchi#sorry for all the whump my guy#instability theory

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deconversion by Lomonaaeren Pairing: Harry/Draco Rating: E Word Count: 103k They were right, those old wizards who thought Parseltongue was a Dark gift. As Harry begins his slide down, fighting desperately all the way, Draco is more than happy to take advantage of the Hero’s fall from the Light.

#drarry#drarry fic rec#harry/draco#draco/harry#hp fic rec#rating: e#100k+ words#post second wizarding war#post hogwarts#dark themes#get together#theme: manipulation#dark draco malfoy#angst#aurors au#auror harry potter#theme: mental instability#theme: snakes#magical theory#theme: parseltongue#dark harry potter#theme: insanity#insane harry potter#mlm ship#horror#theme: body modification

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎆HOT TAKE: Jevil was never a sane or good person. His true nature was merely exposed by the "strange someone."

(A theory by an actual insane person.)

Although this is the first time I am addressing Jevil on this blog, I feel it is worth analyzing his character due to his parallel yet vastly different experiences to Spamton's. He is very interesting, and I like him for different reasons, but I can't deny that his actions make him less sympathetic as a person.

In-game, Seam, who was once friends with Jevil, describes him as having "gone mad" after talking to a "strange someone." Fans have taken this as a reliable narrative since it's coming from a presumably old but wise figure who was once close to Jevil. However, allow me to introduce these two concepts:

The Unreliable Narrator Perhaps within Toby's intentions, Seam is portrayed as an old yet wise figure, almost like a wizard. Just because a character appears to fulfill an archetype does not mean that the character is actually that archetype.

Cognitive Bias It is a well-known fact that people are willing to see the best in others who we consider to be friends, family, or lovers. Seam thinking Jevil had "gone mad" was likely due to Jevil never expressing his worst antisocial traits openly before talking to a "strange someone."

Seam also describes Jevil as always being into games, which surprises no one given his jester themes and design. Pranksters can be mean-spirited, and in the case of his implied interactions with Spamton, this is very evident. Spamton describes him as only being into "games," and how no matter what he did (even cheating), he could not beat him. This reference is never in-game, but we can still apply it to our understanding of Jevil's character since it was part of a canon Q&A. His implied coulrophobia and disdain for clowns can either be seen as a meta-commentary and joke about the Deltarune fandom's love for secret bosses or an excellent hint of how mean-spirited and unhinged Jevil really is. Someone doesn't develop a phobia from just one bad game unless that interaction was very uncomfortable to the point where it made Spamton feel threatened (possibly for his life). (Also, I am aware some people say they are exes. Given the lack of substantial evidence of this in-game or in the Q&A, I think it's safer to say that the "ketchup kids" part merely references a meme and shouldn't be considered anything substantial for analysis.)

Jevil was already showing signs of someone with antisocial traits, particularly among individuals with Cluster B personality disorders. He also falls under the category of Personality Type B (unrelated to Cluster B personality disorders) because of his lack of urgency. We can summarize him with these hallmark antisocial traits:

Lacking remorse for actions.

General dearth of empathy.

Grandiose Self-Worth (I CAN DO ANYTHING)

Need for stimulation and prone to boredom (which is why his solitary confinement was awful for him.)

Lying and manipulative (tricks the fun gang into breaking him out of jail only to try and kill them afterward. He doesn't even want Kris or Susie's souls. He just wants to have "fun.")

Lack of any long-term goals (he merely exists for games.)

Lack of value for other's lives (he finds the idea of murdering teenagers as an exciting game.)

Blasé attitude about life. Essentially, he is doing whatever the hell he wants without fear of consequences.

Notice the recurring theme of "games." In this case, a "game" to Jevil means whatever he wants it to mean. A game for him might mean torture for another person. His bullet patterns also exemplify this. They are aggressive, cluttered, and have (fittingly) chaotic patterns. Spamton's, by comparison, are structured and not as dense, showing his restrained need to kill the party to achieve his goals (particularly with Kris.) Also, notably, Jevil never considers the party "friends" by the end of the battle, regardless if you choose the ACT or FIGHT options of beating him. If you pick the ACT option, he goes dormant as a tail, but in the FIGHT version, he stays active as the Devilsknife and shows enthusiasm about being used as a weapon (presumably) to harm others.

And here's the kicker of all this: these traits are seldom learned but are inherent to some individuals, particularly those who fall closer to psychopathy than sociopathy.

Psychopaths have strong genetic predispositions, meaning they are born that way. While there are many psychopaths who never go on to become mass murderers, it takes a significant amount of social pressure and understanding for them to realize their actions will get them into trouble.

Prior to speaking to that "strange someone," Jevil was likely held back by his perceived notions of governance and law in the Card Kingdom. As the court jester, he probably believed he could express his desire to mess with others because of his assigned role. Being the "fool" of the court, he must have made the Card Kings laugh at his expense, and for most of his existence, he was probably okay with this since jesters, in our reality, were known to make some pretty nasty jokes about royals only for it to all be laughed off. Playing games with Seam was just an added bonus, and Seam likely saw good in him that no one else did. However, Jevil learned that he could do whatever the hell he wanted with (perceived) zero consequences, and he ran with it.

Any goodwill he had with Seam or the Card Kings was dropped the instant he knew he could do anything he desired. This is not behavior from someone who is even remotely sane. The "strange someone" told him what he wanted to hear. Now, the jokes were no longer just jokes. Seam mentions Jevil saying things that don't make sense, but there is a shadow of doubt that this is the only reason he was locked away. Considering his interactions with the main party, he may have attempted to kill the Card Kings, hence why he was imprisoned by Seam, the only person, as Court Magician, who could match his strength.

This ties back to my initial arguments about Seam's unreliable narrative and cognitive bias. Seam saw Jevil as sane and playful, whereas the "strange someone" knew Jevil wanted to unleash his inner thirst for more dangerous games. These needs were always there, he just needed someone to tell him he could do them.

☠️

This is a bit of an aside, but I recommend anyone who likes Jevil to read Edgar Allan Poe's short story, Hop-Frog. It's about a diminutive jester whose attitude closely mirrors Jevil's, only without a Seam to hold that jester back. Honestly, Hop-Frog was the first thing that popped into my head after beating Jevil. It's definitely worth a read (or listen if you can't read it.)

Like with my Spamton sanity theory, I hope my Jevil analysis and insight as someone with life-long mental health problems can help others see this character in a way that may be enlightening or interesting.

💜

#deltarune#deltarune analysis#deltarune theory#deltarune chapter 1#jevil#mental instability#mental illness

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timeline things

I figured out how to fit the BS games into the timeline!

In order to incorporate all the heroes for this AU, the TC timeline will be split up so that “every time someone time travels and makes significant changes in that time, a new timeline split is created” (so going back in time to complete the Temple of Time in Twilight Princess wouldn’t cause a new timeline for instance). Basically this rule means that a timeline is created where the person DID travel through time and a timeline where the person LEFT and life continues on without that person, as if they just vanished into thin air. It is much more confusing than Nintendo's timeline but bare with me

This creates 4 main timeline splits

when Impa travels back and forth to aid Zelda in Skyward Sword

when Zelda sends Link back to his childhood in Ocarina of Time (we already know this one)

when Veran possesses Nayru to travel between the ages in Oracle of Ages

when Zelda travels back in time in the memories in Tears of the Kingdom

(technically Hyrule Warriors: Definitive Edition doesn't combine or split the timelines but rather makes the timelines super unstable since Cia brought people to her time rather than traveled herself, more on that later)

Skyward Sword

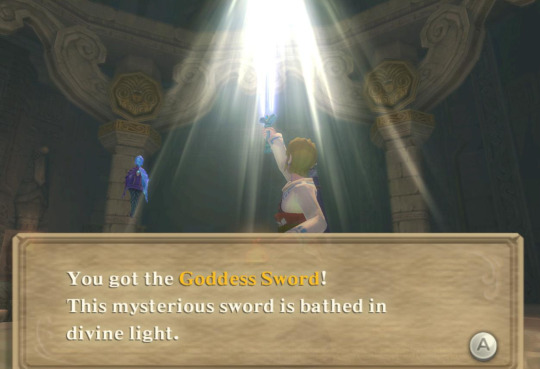

When Impa travels back and forth in time to help guide Zelda (Destiny) as Hylia's reincarnation, she inadvertently brings Ghirahim with her and starts the events of Skyward Sword as we know it. This is known as the Master Sword timeline because Link (Chosen) ends up upgrading the white goddess sword into the master sword.

However, this means Impa leaves a timeline where she didn't time travel in the first place known as the Goddess Sword timeline. In that timeline, Destiny is not kidnapped by Ghirahim but does end up being drawn to the power of the triforce on the surface. Chosen and Groose try to help her but Chosen doesn't find the goddess sword and Groose (the first ancestor of the Gerudo) ends up sacrificing himself to help defend them. Destiny somehow ends up barely sealing Demise but without Impa's guidance, she accidentally fuses the pieces of the triforce into one singular artifact known as the light force. The hylians of Skyloft still descend to found the settlement of Hyrule but some creatures (who later become the Minish) stay in the sky and discover the untouched goddess sword.

Demise's monster army is still scouring the surface as Hyrule is being founded. So in the Age of the Minish that follows, the small race descend from the sky and bring the light force and the goddess sword (referred to as the Picori Blade) to the hylians to help defeat the monsters. The light force only responds to the new princess (Power) due to her goddess bloodline. The hero of men (Mighty) wields the Picori blade and seals the monsters of Demise into the Bound Chest, thus creating the legends in the intro sequence of the Minish Cap. The Picori Blade goes on to become the Four Sword in the events of Minish Cap. Based on this, the Goddess Sword timeline contains the Four Swords trilogy (Minish Cap, Four Swords, FSA) while the rest of the games exist in the Master Sword timeline.

Ocarina of Time

We already know how the adult timeline and child timeline split. The downfall timeline is also basically the same in concept. When Young Link tries to wield the Master Sword, there's a timeline where he doesn't travel forward in time or get aged up into Adult Link. Thus, Young Link is not strong enough to defeat Ganondorf and dies during their fight.

The Adult timeline contains The Wind Waker, Phantom Hourglass, Spirit Tracks, and Hyrule Warriors.

The Child timeline contains Majora's Mask, Twilight Princess, Link's Crossbow Training, the Age of the Sheikah (first Calamity), and Breath of the Wild.

The Downfall timeline contains ALTTP, Oracle of Seasons, Oracle of Ages, and Link's Awakening.

Oracle of Ages

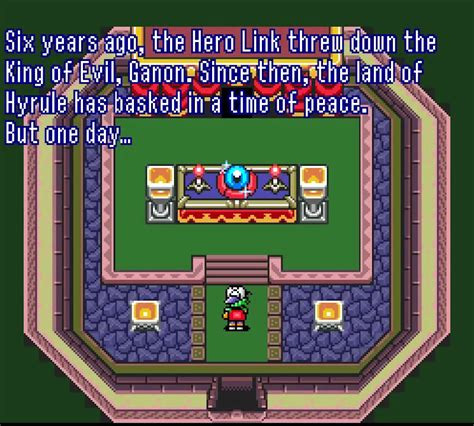

In OOA, the Twinrova send Veran to possess Nayru and use her time powers to go back in time to light the flame of sorrow while Legend uses the Harp of Ages to collect the Essences to stop them. But by doing so, there is a timeline that Veran-Nayru leaves and Legend is able to defeat the Twinrova prematurely, without the flame of sorrow lit to resurrect Ganon. In that battle, as a last ditch effort, the Twinrova curse Legend with horrible sorrow before they are defeated. This causes him to carry this innate sorrow in his heart that is subtle at first and slowly grows over time but Legend is none-the-wiser and sails home.

When Legend is sailing home, he goes on the adventure in Link's Awakening. But because of his growing sorrow, he can't bear the thought of saying goodbye to Koholint or waking the Wind Fish, so he chooses to stay there and live in that dream world forever. This is known as the Dream timeline.

In the Dream timeline, it's unknown if Legend is alive or if he died at sea or is in a weird state of Schrödinger’s limbo. In Legend's absence, the monsters of his time return six years later and two young children Star and Sun are forced to take up the mantle. They do not have the hero's spirit (Legend holds it) but are endowed with the light of the goddess, going on to become the heroes of light in BS Ancient Stone Tablets. These two heroes also go on a very fast-paced adventure many years later in BS The Legend of Zelda.

The other timeline where Legend successfully completes OOA and Link's Awakening in canon is called the Reality Timeline. In the Reality timeline, Legend returns home successfully and can defeat the monsters that return with ease. Many years later, Legend's successor Clover does ALBW and then travels to Hytopia to become one of the Triforce Heroes with two other Links nicknamed Ember and Aqua. In the Reality timeline, Hyrule enters an era of peace for many years until the Era of Decline, when Fay becomes the hero of TLOZ and the Adventures of Link.

Tears of the Kingdom

When Zelda goes back in time in the beginning of TOTK, she creates a timeline where she becomes the light dragon and lives for over 10,000 years (which is the canon of BOTW and TOTK) known as the Light Dragon timeline. The young pre-Calamity Zelda would notice the dragon during her childhood and feel strangely drawn to the creature, she ends up pulling herself away from her Sheikah research sometimes to spend time trying to catch a glimpse or study ancient legends about dragons and Zonai. The events of BOTW and TOTK occur normally in this LD timeline.

In the timeline where she doesn't become the LD, Zelda solely focuses on Sheikah research and experiments with ancient relics, even re-activating a strange mini-Guardian she names Terrako. This is known as the Terrako timeline because when the Calamity hits, Terrako goes back in time to prevent the death of the Champions in HW: Age of Calamity (technically creating 3 timelines because Terrako time travels too but we're going to pretend it works out for now until another game comes out)

Hyrule Warriors

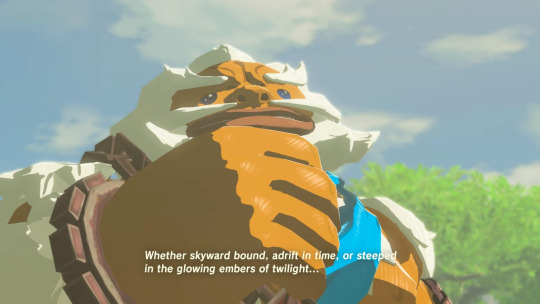

Normally, Hyrule Warriors is the game that connects all the OOT timelines because of Cia opening up the time-space portals between the eras, allowing for Breath of the Wild to come after. However in this timeline, BOTW occurs in the child timeline with Twilight Princess, which is why the past heroes mentioned in the Subdued Ceremony memory are “skyward bound, adrift in time, or steeped in the glowing embers of twilight”

Meanwhile, I put HW after Spirit Tracks when New Hyrule is founded and a new royal army is formed. Purely based on vibes in all honestly.

Instead of 'merging the timelines,' HW creates cracks and instability between the timelines, accounting for weird inconsistencies between eras like Majora's mask in Link's house in ALBW or a small subsect of the Zora evolving into Rito without the flood in the Child Timeline. Maybe that’s also how the TC heroes manage to meet up across time hehe

Although, there’s a particularly strong connection between the downfall timeline and the goddess sword timeline. Namely, the palace of the four sword can be found in ALTTP while Ganon and the dark world find themselves in FSA (since with Groose’s death, the Gerudo, and Ganon by extension, cease to exist). I like to think their worlds are unstable already due to their status as ‘failed’ timelines in a sense and messing with the hero’s spirit (fracturing it into 4 with FS and the weird limbo Legend gets into in the BS games). So to compensate for their unstable states, they start to bond together and share pieces from their world like electrons to form some semblance of stability and strength.

This was just supposed to be about accounting for the BS games but all this timeline talk kinda got away from me and became an essay, it’s fun to think about though!

#I like the idea that the heroes have to find the portals in each realm rather than portals just showing up whenever#make them work for it#maybe they have to identify the points of instability in every Hyrule#to find the monsters and move on to the next world#giving them a bit more agency in when they leave and giving them time to recover from battle#we shall see#honestly I always thought the four swords trilogy didn’t make sense in the main timeline#mostly cause it was made by different people but whatever#so I fixed it in my own way#by making the timeline worse mwahaha#twin chains#tc au#loz#timeline theory#loz timeline#I like to think in one timeline link gets to be with marin#but the world goes to shit without him#but he’s none the wiser#i made a timeline image but can't figure out how to upload it#if anyone wants to see lmk

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ate some strawberry yoplait and my mouth isn't swelling up so either yoplait uses fake ass strawberry chunks or my allergy was maybe temporary? Or maybe I'm just not allergic to THESE strawberries. will have to conduct more experiments. but first I think I want to experiment with eggs again because I'd kill for a breakfast burrito

#i know that strawberries can trigger mast cell instability and cause an allergic reaction that isnt the same as like#someone being normally allergic to peanuts or something#And it comes and goes#And there are theories that one of my other conditions is caused by a minor form of MCAS so I'm already possibly predisposed to that#Idk man strawberries are weird#In case anyone was ever wondering though Starburst uses real strawberry juice in their strawberry flavored starburst#skittles does not.#As for eggs i am allergic to egg yolk but only in the cooked form of normal egg#I can have it baked into foods just fine I just can't eat like. Scrambled eggd

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Must I contribute to society is it not enough to have an unquenchable thirst for knowledge?

#i genuinely love the structure provided by school why can't I just do that forever#its only sophomore year but like. 😬#there are like so many things I want to do#which i guess is the beauty of the music industry#but its also got scary levels of instability#and idk sometimes im not sure if ive got that beginning first push in me#anyway ive thought but not done much research on potentially doing grad school#and becoming a professor#being paid to infodump sounds awesome and i love theory#and my advisor is really cool#but paying for it 😬😬😬😬#but like i could also work in sound while doing that#and compose scores#but mostly i want to learn theory#its so fascinating to me like music functions as both a math and a language system#but also i think a good way to practice scoring would be to re-score existing films#but also to analyze the original scores#analysis is so fun i want to know to create each emotion#hence continuing school

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh bruh shut up again with your asinine Lila Rossi is an adult or Esther from Orphan dungsense infested with maggots.

Take that to the recycle along with yourself.

#Yo imagine trying to make sense the worst way possible against a character#lila rossi#Do you know what you're asking for and how much more destruction confusion and distortion upon many?#INCREDIBLE! Watch other shows or other cartoons or magic cartoons challenge impossible#anti ml fandom#anti miraculous ladybugfandom#Do not desire a double edged sword if the previous sword carved undesirable conclusions#plumsaffron#Sigh why must one prompt theory for further accursed fandom instability

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snippet 3

Business | Technology��

KaibaCorp Dreams of Another World

May 28

“It’s not a question of what’s next. It’s what’s happening right now. Right in front of you.”

These are the words from the seventeen-year old visionary Seto Kaiba, known worldwide as the reigning Duel Monsters champion and CEO of KaibaCorp (TSE:KBA). His advice seems perfect for this moment: he is standing right in front of a gigantic dragon. It is screaming and ready to attack and he is fearless.

The creature in question is one of three in the world that belong to the young CEO: Blue Eyes White Dragon, a rare Duel Monsters card and the star of KaibaCorp’s impromptu demonstration of its latest project: Scheherazade.

Named after the fabled storyteller of “One Thousand and One Nights,” Scheherazade is as much a technological marvel as it is a philosophical leap forward. The platform creates immersive worlds drawn from both written stories and players’ own memories, merging fiction and reality into a seamless experience. A combination of machine learning, memory recall, and advanced simulation technology allows the system to respond and adapt for real-time, constant immersion. While virtual reality has been evolving steadily over the past decade, Scheherazade’s memory integration takes it to another level, with unprecedented possibilities for storytelling, education, and, of course, gaming.

Its most immediate application will be for duelists, offering fully interactive Duel Monsters matches in an arena where the creatures seem to step out of the cards and into life. Industry insiders speculate that this move could put KaibaCorp at the forefront of both gaming and virtual reality, potentially outpacing rivals like Industrial Illusions (NYSE:ILL) and Meta (NASDAQ: META).

This is the latest in the bold new direction forged under young Kaiba’s leadership, which transformed KaibaCorp from an arms contractor to a tech powerhouse, pioneering innovations at the intersection of telecommunications, augmented reality and entertainment. KaibaCorp’s origins date back to the post-World War II era when it rose to prominence as a leading arms manufacturer, standing just behind global defence giants like Lockheed Martin (NYSE: LMT) and Northrop Grumman Corp (NYSE: NOC). The company’s previous success in the defence sector is often credited to the founding family’s deeply personal experience with war: Ryu Kaiba, KaibaCorp’s founder, served in Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service during Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour. The war also impacted his son, the late Gozaburo Kaiba, who was one of the 650,000 survivors of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

The latter half of the twentieth-century saw KaibaCorp as a bastion of military technology, supplying weapons to governments around the world. Yet the company was perpetually mired in controversy, and a frequent target of political outcry for its contributions to war and conflict. Protests frequently accompanied its business dealings, which placed it at the centre of public debate about the ethics of arms dealership. It is speculated that mounting pressure and dwindling public support factored into the shocking suicide of Gozaburo Kaiba, who jumped to his death from the KaibaCorp headquarters during a meeting with the company’s board of directors.

This tragedy would make it the third time Seto Kaiba had lost a parent. Gozaburo Kaiba adopted both the current KaibaCorp CEO and his younger brother, KaibaCorp’s Senior Manager of Technology Operations, Mokuba Kaiba, following the deaths of their parents. Their mother died of eclampsia while giving birth to Mokuba, and their father was killed in a car accident in the infamous Izumo Earthquake Disaster.

Seto Kaiba succeeded Gozaburo as CEO of KaibaCorp at fifteen, making him the youngest person to ever lead a billion-dollar company. His youth left him no shortage of ideas, and he set the company on course for a seismic shift in focus. He went on a buying spree, absorbing a staggering number of promising computer technology companies in his first quarter as CEO. He also terminated operations at KaibaCorp’s global weapons testing centres and completely divested the company from projects supporting armed conflict. These actions led KaibaCorp to several high-profile lawsuits for defaulting on its contracts and sales agreements. These disputes were settled out of court for an undisclosed amount.

Between the payouts, acquisitions and lack of customers, KaibaCorp was teetering on financial ruin. The company was saved with Kaiba’s most notable innovation: SolidVision, the holographic projection technology that brought Duel Monsters to life. This was followed by the Duel Disk, a revolutionary p2p interface that allowed duelists to compete in real-time holographic battles, becoming a staple for competitive players across the world. These commercial successes catapulted KaibaCorp into global fame and made Duel Monsters a cultural phenomenon, while signalling KaibaCorp’s new mission: to create, not destroy.

This pursuit has now brought KaibaCorp to the verge of another groundbreaking moment. Scheherazade, set to roll out this summer, will first be available at stadiums and theme parks before making its way into homes through a specialised hardware release. Duelists and VR enthusiasts alike are eagerly awaiting the chance to immerse themselves in the fully realised worlds this technology promises to deliver.

In many ways, KaibaCorp’s evolution is as poetic as it is fascinating. What was once a company defined by its contribution to destruction is now positioned to offer the world a new way of seeing itself, through stories, memories, and duels.

“This is just the beginning. Scheherazade isn’t just a virtual space—it’s a new frontier for human imagination. It’s the bridge between what we can dream and what we can live.”

And in that, perhaps, lies Kaiba’s greatest victory: transforming a company of war into one that makes dreams reality.

______

The article featured two captioned pictures. Duel Monster Blue Eyes White Dragon, rendered in Scheherazade: a still of him pulled from the testing zone broadcast, looking up at Blue Eyes White Dragon. He was surprised at the lack of fear on his face– the light from the White Lightning Attack had washed every emotion into brightness. He was just vacant, ready, waiting. He was more expressive in the second photograph: Father and son. One of the last before Gozaburo’s death. The man had a hand on his shoulder and was sneering down at him. Kaiba, fifteen, slanted his face to return his contempt, the corner of his mouth barely lifted in a matching, cruel smirk.

#moonogre#yugioh#writing#wip#seto kaiba#gozaburo kaiba#instability theory#current wip#someone please come get my son#violetshipping

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The three orders: Laboratores, Bellatores, Oratores. Godwin, Johanka, the women doing shrooms, the other heretics we meet, Chenyek and the Guild, the schism between the Kuttenberg brothers and the Sedlec brothers, and the shadow of young Mr Hus all showing different weaknesses in the authority of the Church among the Laboratores. The civil war, Henry’s parentage, Hans and Henry’s flip-flopping dynamic, Toth/Liechtenstein/Devil/ Zizka slumming it, all showing the order of the Bellatores being uprooted and overturned. The ease with which Sigismund’s succession was makes nobles into nobodies foreshadowing the possibility of overturning the church as we know it with military pressure from bands of randos…

#kelsey liveblogs kcd#I forget the blog name but once again we are indebted to those who have been kcding since 2014 and their theories#the main thrust of kcd is the inherent instability of the feudal order

1 note

·

View note

Text

Oof worked through some shit today but I'm still ready to dive balls deep into Lenin's writing so maybe I'm still not ok/at peace lol

#dont get me wrong#Pre-Power Lenin was fucking goated with the sauce#but me wanting to get into theory is probably a sign of emotional instability and slight psychosis for me

0 notes

Text

Amity Park, The New transylvania Town.

Got inspired by this beautiful post <- By this person @nerdpoe <-

Due to Amity Park town folks is completely independent on Ectoplasm air and liquid, but totally allergic to the sun in daylight.

They found a loophole that they could go out at night, but nobody able to leave fully from amity park due to the lack of ectoplasm that cause them to become weak, their skin paler then white paint, lengthing fangs, eyes nearly glowing onimous green from ecto- starving and the instable rage induced that come with it.

The Fenton and Frostbite came up with the temporary solution, which was modified thermos bottles full of ectoplasm, which end up becoming a business around town.

The unfortunate side effect seems to make the pure ectoplasm turn red and heavy scented like blood outside the town.

Family, lovers, and friends that visited Amity Park would come back with a 4 boxes stuff to the brim with bottled up ectoplasm to get refilled and visit the town again every 2 months to the point rumors started to come due to some crazed theory.

That Amity Park became a town of vampires. The rumors start another rumor that they never leave the town at all due to the dark clouds cover it's entirely. (The saturated ectoplasm clouds look like dark fog clouds above the sky)

People who came to visit and come back with boxes full of bottled up blood.

Then, when rumors reach the ears of the Justice League, it would be a year in Amity Park to become a much bigger community than when it used to be a small town.

#dpxdc#dc x dp#danny phantom#dp x dc#dp x dc crossover#dcxdp#dc x dp prompt#danny is the ghost king#the world believes amity park became a clan city of vampires#pure ectoplasm when in a modified thermos bottle look and smell like blood

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

a few anons asked me about an arcane!viktor and league!viktor fic. here it is. the machine herald and the herald of the arcane sandwich.

18+, arcane season 2 spoilers

════════════════════

The recent influx of arcane anomalies is responsible for many, many things; the dysfunction of the Hexgates, the instability in several Hextech devices. And additionally, apparently, messing with anomalies often results in rifts, capable of bridging one universe with the next.

You're assuming, anyway. It's the only option to logically explain why you're currently sandwiched between two Viktors.

"Are they always this… obedient?" Viktor — the menacing, Hexcore-infused, arcane-touched version of Viktor — hums, his voice deep and distinctive. It rumbles through you, threatening to displace your shaky legs with its boom alone, echoing several times before it settles in your eardrums.

You take in a sharp breath, one you're sure the both of them can hear. The lack of space within the anomaly's pocket of unreality forces you to fall back against his chest. True to his assumption, when Viktor's hands find your waist, your limbs go limp. You pliantly allow him to lift you, until you're settled on his thigh.

"It is difficult to tell." Viktor — the other Viktor, all metal edges and mechanical thrums — finds your jaw. With a firm, steel index finger, he guides it, carefully bringing your wandering gaze back to him. His mask is expressionless, glowing orange pools of light examining you blankly.

But you swear, the thickness to the edges of his muffled accent, the way he grabs your chin hard, keeping you in place when your head threatens to fall back, as his counterpart's fingertips analytically skim your side — It screams jealous.

Your eyes flicker all over his figure, unsure what to focus on. Unsure what to make of this. And Viktor laughs, maniacal and amused. His third arm, his Hexclaw-hand, reaches down towards your much smaller figure, settles on your head, and ruffles your hair in something of a playful, infantilizing gesture. Or, it would be playful, if his third hand wasn't capable of producing a dangerous, one-thousand temperature Death Ray.

"I believe," Machine-Viktor starts, "We are intimidating them."

Arcane-Viktor glides his palm over your chest, approving. His touch is foreign, neither rough, nor smooth. "Precisely."

So much for trying to hide it. In this situation, how could you not be intimidated?

Both of them are insanely intelligent, to the point it nearly scares you. They're larger, taller; you have to crane your neck up to continue looking at Machine-Viktor, gaze steady on him like he's instructed.

And Arcane-Viktor is somehow even taller than his copy. It makes you feel helpless in his arms, with the way his figure dwarfs yours completely. You can practically feel the persistent glow of his eyes, boring into you. Examining you with a sixth sense of perception, that could only be defined as inhuman.

The Machine Herald and the Herald of the Arcane are inscrutable. They're both impossible to read, you couldn't hope to determine what they're planning if you had a million timelines to do so. There's a strange sense of understanding between them. A form of matched intuition, perhaps, that comes with being one in the same.

Truthfully, they've been arguing, bickering over every topic to be brought up since you got stuck here. Cosmological theories, conflicting assumptions, defining the line between the mechanical and the arcane — It's all flown over your head, honestly. Literally and figuratively. This is the first time they've focused on you since the moment you became pressed in between them.

Yet, when you are involved, they seem to be on the exact same page. The Machine Herald gives a single nod towards the Arcane Herald, and without the need for words, they're switching tasks.

Machine-Viktor takes your thighs, holds them instead, palms splayed underneath them to brace the weight. Your legs wrap around his waist instinctively, locked at the ankles, his metal armor smooth yet firm against your skin — and Arcane-Viktor steps in closer. Your back presses entirely against his chest, helping to support you.

His outline digs into your shoulder blades, golden and rib-like. And his hands, purple-hued, rich with power, grasp your face to tilt your head back. To make you look at him, instead. You aren't sure which set of eyes to focus on. The claw jutting out from his back twitches, seemingly regarding you with its own element of sentience. The other Viktor stiffens, for a moment.

But the position you've been placed in is deliberate; it leaves you wide-open. So, he takes advantage of the opportunity his counterpart has graced him with. His third arm hums mechanically as he moves it. He brings its hand to your mouth, and your lips part to let him press his thumb inside.

It's more analytical than anything else.

Arcane-Viktor watches, transfixed, as your tongue swirls around the faux metal digit. It's a curious lesson in mortal instinct. You whimper, your gaze grows misty as you try your hardest to focus on him, but you barely falter. You aren't giving up. Weak and desperate, your whole body shudders, enough to be felt on his palms as a tremble rushes through you.

Oh, you want to be made to shudder, he realizes. This is a wealth of emotion and excitement and desire for you, an addicting amalgamation of new sensations to experience. Humans love to chase this high. They cannot be distracted by fear, when raw, depraved need clouds their judgement. His machine-equivalent understands this concept, surely.

Your plush lips meet the artificial joints: welded with clean, steel pivots. Viktor would recognize his own handiwork anywhere. But the intricate assembly around each linkage — the other Viktor has improved the design, he's made each subdivision double-jointed.

Intriguing. Perhaps he should teach his opposite self about the arcane, as reimbursement.

Your tongue licks a hot, slow stripe onto the end of the Machine Herald's thumb, and he breathes a half-sigh, half-huff, causing smoke to pour from the sides of his mask.

There's warmth, coming from both of their figures. Just two different kinds of warmth. For the Arcane Herald, it's electric, like stars and static, racing across your skin. For the Machine Herald, it's more stifling, artificial. Like standing over a hot stove. It's the heat of countless individual parts of machinery, internal and external, all working in unison to support his processes.

And you're starting to sweat.

"Marvellous," Arcane-Viktor murmurs, oddly inquisitive. "Are they not?"

Removing his thumb from your mouth, the metal slick with your saliva, the Machine Herald gives a rumbling hum of approval.

"Yes. They are."

Your throat tightens, suddenly dry. From above you, the all-powerful Herald of the Arcane tilts his head ever-so slightly, adjacent to an interested cat. He taps his thumb against your puffy bottom lip, as though he's considering repeating the display himself. Lingering residuals of magic thread through you faintly, tingling on your lips with each idle tap.

When he decides against it, finally letting go of your face, Machine-Viktor is quick to grasp your chin with his Hexarm. Roughly guiding your gaze back in his direction. Selfishly recapturing your attention.

Unfortunately, your attention is everywhere. It shifts, placed between the budding heat in your body, the weightlessness of your limbs as you're held in place, the press of metal armor to your thighs, the tracing of confident fingertips up your stomach. Your vision blurs around the edges, you can barely focus when you're this overwhelmed.

Arcane-Viktor's palm is beginning to trace up your chest, and you wonder if he can feel your heart pounding, if either of them know how much you're enjoying this. Surely, they're well-acquainted. They fucking tower over you, and you're bare, you are pliant. For either version of them, for Viktor, you will always be just as they hypothesized.

Obedient.

"They are trembling. How curious," The Herald of the Arcane continues, but the deep, confident vibrato to his voice makes you believe your reaction is far from unexpected. "Theoretically, I could imagine this being too much for them."

"No," The Machine Herald counters, "It is not."

The Arcane Herald appears to express as much aversion as an unchanging expression is able to. His palm begins to trace back down, this time. With the same slow, methodical movements; possessive, in a way. Down to your stomach, stopping just above your pelvis.

"You would truly place confidence in their ability to take us?"

Hands suddenly grasping your thighs tighter, you're pulled closer, unintentionally grinding you against the ridges of his metal plating — you breathe a quick, pleasured noise, your thighs tremor hard, but you know his iron grip wouldn't let them fall — and the Machine Herald practically scoffs.

"They will take all we give to them. Such is the essence of their potential."

The Arcane Herald pauses, before he answers, "I believe in your own lingering sentimentality, Machine Herald, you may be vastly overestimating their limits."

"It is not sentiment." The Machine Herald's voice is level. His thick accent curls around the words, tone rich with a downright ruthless sense of certainty. "Receptors in my central system have been allocated to measure their breathing. The pattern is not one of discomfort. They are rife with… eagerness."

His Hexarm reaches for your neck, and your head tilts back submissively. As confirmation, your heart skips, your breath catches. Your gaze is heavy and pleading. He squeezes methodically, until your eyes are rolling back, and your arms are falling limp.

Precise fingertips find your forehead, they muddle your every thought and function as their prying touch seeks to enter your mind. Your thoughts converge into a singular, tightly knit thread, pounding in echoes of pleasure. A hand brushes between your spread legs, finds where you are slick and aching —

"Viktor-"

Your voice is weak, desperate, shuddery from the lack of use.

And to your delight, both of your overseers react. Machine-Viktor gives your thighs a firm squeeze, he caresses your throat fondly. Arcane-Viktor teases you. His fingertips purposefully prod your waiting entrance, and Gods, they feel like magic incarnate.

They vibrate from the intensity of their own existence. You can feel every thrum, and each lush wave of the arcane, vibrating mercilessly against your sweetest spot. Then, just as you're beginning to believe you could come apart merely from this, his hand is delicately shifting away, and you're left to quiver around nothing.

"Fuck," You're swearing, "Please- don't stop���"

The Herald of the Arcane, as though he wasn't just mere moments away from sinking his fingers inside you, replies in a distinctly composed tone. "Humans can be such demanding creatures."

The Machine Herald nearly sounds annoyed. "You have forgotten our initial objective. We may switch places, if you are convinced you cannot satisfy them."

"Whatever occurred in your timeline, it is clear you never learned patience. We have time. Our research will prove most accurate when it is fleshed out to its fullest, not when it is rushed. Unless, perhaps you have discerned a solution to getting us out of this anomaly. Do share, Machine Herald."

Machine-Viktor remains still. Utterly unreadable, as always.

"Hold them."

Everything happens so quickly, so flawlessly, you'd almost swear they planned this — Arcane-Viktor takes hold of your thighs, he keeps them spread while he leans your body against his chest. And Machine-Viktor grasps your face, squeezes your cheeks, his leather glove rough against your chin. He's so close, all you can see is the orange of his makeshift eyes. Bright and intimidating, clouding your view with polychrome shapes, like if you were to glance at the sun for too long.

His touch is distinctly different, it is steady, resolute, determined. A single thick, metal finger drags through your arousal to first get the steel slick, and then he is pressing it inside; you can feel every small joint and deliberate ridge as he fills you. One of his manufactured digits is essentially the equivalent to three of yours.

You're left to weakly slump against his copy, completely at his mercy as he fucks you open, completely at their mercy as the two of them watch you attentively. Focused on the way his digit disappears within you, how your chest heaves as you gasp and whine.

"This is not enough stimulus," Arcane-Viktor ascertains. Matter-of-fact, his echoing voice perfectly stable. "Their thoughts are still clouded. Preferably, we would want them- their mind, and their body- to think only of us."

"Not enough? I thought you believed they could not handle us both." Machine-Viktor scoffs.

It's a challenge. An analytical assumption, and if his copy is anything like him, he knows it's a notion they'll enjoy deciphering. Together. With you as the subject.

"Well?" The Machine Herald hums, "Are you willing to put your hypothesis to the test?"

#wrote this on like zero sleep so if you see any mistakes pretend u do not see#you can't tell me viktor wouldn't argue with himself#viktor x reader#viktor x you#arcane x reader#viktor arcane x reader#viktor arcane#viktor smut#machine herald x reader

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Realism ≠ No Mansion

So I saw a confession on the Creepypasta Confessions blog and I am pissed.

First off, to be clear: I’m not trying to attack anyone personally. But I am extremely tired of people throwing around takes like this and calling it “realism” because it’s not. It’s uncreative and borderline gatekeeping.

This is gonna be a long one. Buckle up:

🚫 Saying “Jeff would kill everyone”

That’s not realism. That’s avoiding the question of why he might not. You’re dodging character complexity in favor of edge.

👁 Saying “Eyeless Jack only sees others as prey”

That’s not realistic. It’s ignoring that even monstrous characters might have nuance or boundaries, or that he might recognize other cursed beings as more than meat.

🎮 Saying “BEN Drowned only sees others as pawns”

You're writing off any chance of him forming actual relationships or attachments.

🎪 Saying “Laughing Jack sees them as entertainment”

Again, yeah… until he doesn’t. What happens when the entertainment fails? What happens when he connects? Explore that.

💋 Saying “Nina only cares about Jeff”

Okay, and what about after? What about growth? What about disappointment or found family? You’re locking her character in amber.

⏰ Saying “Clockwork and Toby are too insane to get along”

So… you’ve never heard of shared trauma bonds, dissociation, or neurodivergent kinship, huh? They're more than their instability.

👧 Saying “Sally won’t trust anyone”

Great. That’s the start of a story. What about the arc? Who does she learn to trust? What brings that wall down?

🌲 Saying “Slenderman isn’t a father figure to everyone”

Sure. But why can’t he be one to someone? Who sees him that way? What does he feel about that? Explore the dissonance, not just the denial.

🔥 “Realism” Isn’t an Excuse to Be Boring

I’m sorry you couldn’t think of ways these characters might grow, clash, bond, or just coexist without stabbing each other, but don’t act like that’s realism.

Here’s some so-called “realistic” reasons for why Slenderman might have a mansion just pulled out my ass just right now:

Maybe it’s not his, it’s just a convenient base

Maybe he built it to contain or protect his proxies

Maybe a proxy built it for him

Maybe it’s just a house from when he was human, if you roll with that theory

Why might Jane and Jeff exist in the same space?

Slenderman's forcing them to

Jane’s forgiven him, Jeff doesn't have to stay evil

She’s forgotten what he did, Slenderman gave Toby amnesia why not her?

You can write any of this in a grounded, character-driven way. “Realistic” doesn’t mean “everyone is alone and evil forever.” It means understanding why they’re not.

💡 This Mindset Hurts New Creators

What pisses me off the most is that someone who wants to write a “realistic AU” might see this garbage take and think:

“Oh… I guess I can’t do that.”

YES. YOU. CAN. If you want to write a mansion AU? Do it. If you want to make them friends, enemies, exes, reluctant roommates? Go wild.

Just ask yourself why it works. Get creative. Build the bridges. Tell the story. Stop saying "this can't work." And say, "How can this work?"

Don’t let boring people kill possibility and call it "canon."

#creepypasta#creepypasta fandom#creepypasta community#creepypasta au#slender mansion#slenderman#creepypasta headcannons#creepypasta thoughts#jeff the killer#eyeless jack#ben drowned#laughing jack#nina the killer#jane the killer#ticci toby#clockwork#sally williams#creepypasta meta#fandom meta#found family#character development#fandom discourse#fandom creativity#creative freedom#stop gatekeeping#hot take#unpopular opinion#rant post#long post#this needed to be said

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's also deeply fascinating how the different gimmicks or context for each season sets the tone and culture of the server during it.

Third Life was a uniquely "serious" season when it comes to the depth of the emotional weight put on things, I'd argue. It was the first season, and presumably the last. It wasn't a looping endless death game at the time, it was their only life (well, only three lives) and everyone built real roots. Kingdoms and marriages, things they wanted to genuinely protect, things they wanted to last. There was this thought that if they were to die, that would be the end. There was this thought that if they- and their allies- were to live, they could be happy together. There was this idea that they could live, that there was a world where they keep what they've earned in this place. Which isn't to say emotional stakes don't exist in later series, but Third Life is the one time where permanence and ending were both real tangible concepts to be sought after or feared, unlike now, where there's always last time and next time hovering over the players.

Last Life, on the other hand, was a season of remarkable instability. I've credited this in the past to two core mechanics within the season: the Boogeyman Curse, and the new rule that red names have to leave their teams. These two rules made teams practically impossible to keep. There was the constant fear of betrayal from the Boogeyman, and the constant knowledge that friend could turn into enemy within a second, that the only constant for you to rely on is yourself. Teams were flimsy this season, most people were fundamentally lonely, and distrust permeated most relationships. Beyond the mechanic changes, though, there's also the grief to be talked about. This was the second season, the first time they came back. And with that, came the full reality of impermanence. All their walls and castles and forts and tunnels, even the graves they dug for fallen friends, were gone now, as if they never existed. Nothing in this world is theirs to hold onto, no matter what they do. All they truly have forever is themselves. Last Life is the first time they grapple with this.

Double Life is a server I've talked about a lot because of the sheer cultural isolation promoted by its gimmick. Each player was assigned one other person who was linked to them, who they were forced to rely on for their survival, and, very quickly, an attitude formed that posed soulmate bonds as the most important- no, in some ways the only important- relationship one can have. There was an obligation to be with your soulmate and stay with them and want them and noone else. Alliances outside of soulmate pairs were flimsy, if they existed at all, as the server fell into an isolationist mindset, each soulmate pair an island. People who didn't conform to the soulmate system, people who wanted to choose their own soulmates, or who were alone, or weren't interested in soulmates, were often looked at strangely. With pity or judgment or sometimes aggression. Double Life was just deeply isolating because there was very little community. It was you and your soulmate, and everyone else is the enemy, or at least an outsider.

Limited Life, surprisingly, felt like a series with a lot of freedom. You would expect the constraint of twenty four hours to live to feel like a cage, a limitation, it's literally called Limited Life. But in practice I think you actually got the opposite feeling a lot, because lives were in hours, which meant instead of dying 3-6 times, you could hypothetically die 20+ times. Because of this, I feel like you got a lot more playing around and taking risks and petty rivalries and side storylines in this season, people being less cautious because there was less to lose with an individual death. The fact that you can gain time for killing in this series helped as well, making time feel like a renewable resource, something that's running out in theory, but that you can really just replenish, if you have the competence for it. This made people possibly even more aggressive than in past seasons too, I'd argue, because there was very real incentive to kill, because you will always gain something for it (as long as the kill is legal). This is how we ended up with winding sky paths and tnt falling from the sky every five seconds. Because people were simultaneously more aggressive and less afraid than usual.

Secret Life's another interesting one. I feel like the secret tasks had the capacity to be isolating- and in some cases they were- but I kind of feel like Secret Life had a pretty good sense of community overall, not in spite of, but in many cases because of the secret tasks. Most tasks were funny, tasks were conversation starters in a way (obviously you couldn't talk about them outright, but people would follow someone around to tease them while they're doing their task plenty), tasks typically forced people out of their bases and into going around the server where they'd inevitably talk to people, many tasks even outright involved mandatory interaction with people (often people outside your alliances). And sure, everyone had secrets they couldn't tell, but the non-red tasks (usually) weren't anything harmful, and everyone could have some kind of solidarity in the fact that they all had tasks of their own. And sure, the yellow names being able to guess tasks added some 'tension', but that gave yellow names solidarity with each other and a reason to talk amongst themselves and to the greens. I just feel like Secret Life was an especially social season because of the tasks themselves and how a lot of them mandated communication outside your own alliance.

And then there's Wild Life. This..is another season I think was pretty social, for very similar reasons to Secret Life. The Wild Cards were fun, they gave people something to bond over (because they all have to deal with the wild cards), and they'd often offer an excuse to leave your base and go around the server instead of spending whole episodes working at your own base with your preexisting alliance. People still tried to kill each other of course (particularly when there were dark greens alive to get lives from), but there was also often more focus on the wild cards than on the battle royale aspect of the game. I mean, it took shockingly long for people to even start really killing each other in the finale, I remember sitting through practically half the session and wondering how they were going to wrap it up this session because noone was killing each other for a good chunk of it. This season also had the zombies (both in the super power episode and in the finale), which I think gave some more levity, because even if you die, you're not even gone from the series, you get to pop back up and be silly for a little bit, which I think also lightened the pressure to play too intensely.

I just feel like every season had a very unique culture caused by the gimmicks and context surrounding them and that's fascinating to me.

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Age: The Veilguard: Strangled by Gentle Hands

*The following contains spoilers*

“You would risk everything you have in the hope that the future is better? What if it isn’t? What if you wake up to find the future you shaped is worse than what was?”

– Solas, Dragon Age: Inquisition (2014)

I. Whatever It Takes

My premium tickets for a local film festival crumpled and dissolved in my pants pocket, unredeemed as they swirled in the washing machine. Throughout that October weekend in 2015, I neglected my celebratory privileges, my social visits to friends, and even my brutal honors literary theory class. All because a golden opportunity stretched before me: a job opening for a writing position at the once-legendary BioWare, with an impending deadline.

The application process wasn’t like anything I’d seen before. Rather than copy+paste a cover letter and quickly swap out a couple of nouns here and there, this opening required me to demonstrate my proficiency in both words and characters – namely, BioWare’s characters. Fanfiction wasn’t normally in my wheelhouse – at the time, I had taken mainly to spinning love sonnets (with a miserable success rate). But I wouldn’t balk at this chance to work on one of my dream franchises – especially since the job prospects for fresh English BAs weren’t exactly promising. So, I got to work crafting a branching narrative based on the company’s most recent title: Dragon Age: Inquisition. Barely two months prior, I saw the conclusion of that cast’s story when the Inquisitor stabbed a knife into a map and swore to hunt her former ally, Solas, to the ends of the earth. Now it was my turn to puppeteer them, to replicate the distinct voice of each party member and account for how they’d react to the scenario I crafted. And if it went well, then maybe I’d be at the tip of the spear on that hunt for Solas. Finishing the writing sprint left me exhausted, but also proud of my work.

The folks at BioWare obviously felt differently, because I received a rejection letter less than a week later. Maybe they found my story trite and my characterization inaccurate, or maybe they just didn’t want to hire a student with no professional experience to his name. Regardless, I was devastated. It wouldn’t be until years later that I learned that, had my application been accepted, I likely would’ve been drafted into working on the studio’s ill-fated looter shooter, Anthem (2019), noteworthy for its crunch and mismanagement. My serendipitous rejection revealed that sometimes the future you strive to build was never meant to match your dreams. What seemed like an opportunity to strike oil actually turned out to be a catastrophic spill.

Still, my passion for the Dragon Age series (as well as Mass Effect) persisted in the face of BioWare’s apparent decline. I maintain that Inquisition is actually one of the studio’s best games, and my favorite in the series, to the point where I even dressed up as Cole for a convention one time. The game came to me at a very sensitive time in my life, and its themes of faith vs falsehood, the co-opting of movements in history, and the instability of power all spoke to me. But I will elaborate more on that at a later date. My point is, I held on to that hope that, in spite of everything, BioWare could eventually deliver a satisfactory resolution to the cliffhanger from their last title. Or perhaps it was less hope and more of a sunk cost fallacy, as an entire decade passed with nary a peep from Dragon Age.

As years wore on, news gradually surfaced about the troubled development of the fourth game. Beginning under the codename “Joplin” in 2015 with much of the same creative staff as its predecessors, this promising version of the game would be scrapped two years later for not being in line with Electronic Arts’s business model (i.e. not being a live-service scam). Thus, it was restarted as “Morrison”. The project cantered along in this borderline unrecognizable state for a few years until they decided to reorient it back into a single-player RPG, piling even more years of development time onto its shaky Jenga tower of production. Indeed, critical pieces were constantly being pulled out from the foundations during this ten year development cycle. Series regulars like producer Mark Darrah and director Mike Laidlaw made their departures, and the project would go on to have several more directors and producers come and go: Matthew Goldman, Christian Dailey, and Mac Walters, to name a few key figures. They eventually landed on John Epler as creative director, Corinne Busche as game director, and Benoit Houle as director of product development. Then came the massive layoffs of dozens of employees, including series-long writer Mary Kirby, whose work still made it into the final version of DA4. Finally, the game received a rebranding just four months before release, going from Dreadwolf (which it had been known as since 2022) to The Veilguard (2024) – a strange title with an even stranger article.

Needless to say, these production snags did not inspire confidence, especially considering BioWare’s been low on goodwill between a string of flops like Anthem and Mass Effect: Andromeda (2017) and, before that, controversial releases like Dragon Age II (2011) and Mass Effect 3 (2012). The tumult impacted The Veilguard’s shape, which scarcely resembles an RPG anymore, let alone a Dragon Age game. The party size is reduced from four to three, companions can no longer be directly controlled, the game has shifted to a focus on action over tactics a la God of War (2018), the number of available abilities has shrunk, and there’s been a noticeable aesthetic shift towards a more cartoonish style. While I was open to the idea of changing up the combat (the series was never incredible on that front), I can’t get over the sensation that these weren’t changes conceived out of genuine inspiration, but rather vestigial traces from the live-service multiplayer iteration. The digital fossil record implies a lot. Aspects like the tier-based gear system, the instanced and segmented missions, the vapid party approval system, the deficit of World State import options, and the fact that rarely does more than the single mandatory companion have anything unique to say on a quest – it all points to an initial design with a very different structure from your typical single-player RPG. The Veilguard resembles a Sonic Drive-In with a mysterious interior dining area – you can tell it was originally conceived as something else.1

That said, the product itself is functional. It contains fewer bugs than any previous game in the franchise, and maybe BioWare’s entire catalog for that matter. I wouldn’t say the combat soars, but it does glide. There’s a momentum and responsiveness to the battle system that makes it satisfying to pull off combos and takedowns against enemies, especially if you’re juggling multiple foes at once. Monotony sets in after about thirty or forty hours, largely due to the fact that you’re restricted to a single class’s moveset on account of the uncontrollable companions. Still, this design choice can encourage replay value, as it does in Mass Effect, and free respec options and generous skill point allocations offset the tedium somewhat.

While the character and creature designs elicit controversy – both for the exaggerated art direction and, in the case of demons and darkspawn, total redesign – the environmental art is nothing short of breathtaking. I worried that this title would look dated because of how long it had been in development and the age of the technology it was built upon. Those fears were swiftly banished when I saw the cityscapes of Minrathous, the cyclopean architecture of the Nevarran Grand Necropolis, or the overgrown ruins of Arlathan. But like everything in The Veilguard, it’s a double-edged sword. The neon-illuminated streets of Docktown, the floating citadel of the Archon’s Palace, and the whirring mechanisms of the elven ruins evoke a more fantastically futuristic setting that feels at odds with all three previous titles (even though all three exhibited a stylistic shift to some extent). It aggravates the feeling of discordance between this rendition of Thedas and the one returning players know.

All of these elements make The Veilguard a fine fantasy action-adventure game – even a good one, I’d say. But as both the culmination of fifteen years of storytelling and as a narrative-based roleplaying game – the two most important facets of its identity – it consistently falls short. Dragon Age began as a series with outdated visuals and often obtuse gameplay, but was borne aloft by its worldbuilding, characterization, and dialogue. Now, that paradigm is completely inverted. The more you compare it to the older entries, the more alien it appears. After all these years of anticipation, how did it end up this way? Was this the only path forward?

Throughout The Veilguard’s final act, characters utter the phrase “Whatever it takes,” multiple times. Some might say too many. I feel like this mantra applied to the development cycle. As more struggles mounted, the team made compromise after compromise to allow the game to exist at all, to give the overarching story some conclusion in the face of pressure from corporate shareholders, AAA market expectations, and impatient fans. Whatever it takes to get this product out the door and into people’s homes.

This resulted in a game that was frankensteined together, assembled out of spare parts and broken dreams. It doesn’t live up to either the comedic heights or dramatic gravity of Inquisition’s “Trespasser” DLC from 2015, despite boasting the same lead writer in Trick Weekes. Amid the disappointment, we’re left with an unfortunate ultimatum: It’s either this or nothing.

I don’t mean that as a way to shield The Veilguard from criticism, or to dismiss legitimate complaints as ungrateful gripes. Rather, I’m weighing the value of a disappointing reality vs an idealized fantasy. The “nothing”, in this sense, was the dream I had for the past decade of what a perfect Dragon Age 4 looked like. With the game finally released, every longtime fan has lost their individualized, imaginary perfection in the face of an authentic, imperfect text. Was the destruction of those fantasies a worthy trade? It doesn’t help that the official artbook showcases a separate reality that could’ve been, with a significant portion dedicated to the original concepts for Joplin that are, personally, a lot closer to my ideal vision. I think it would’ve done wonders to ground the game as more Dragon Age-y had they stuck with bringing back legacy characters, such as Cole, Calpernia, Imshael, and the qunari-formerly-known as Sten.

I don’t necessarily hate The Veilguard (I might actually prefer it to Dragon Age II), but I can’t help but notice a pattern in its many problems – a pattern that stems from a lack of faith in the audience and a smothering commitment to safety over boldness. As I examine its narrative and roleplaying nuances, I wish to avoid comparing it to groundbreaking RPGs such as Baldur’s Gate 3 (2023) or even Dragon Age: Origins (2009), as the series has long been diverging from that type of old-school CRPG. Rather, except when absolutely necessary, I will only qualitatively compare it to Inquisition, its closest relative.

And nowhere does it come up shorter to Inquisition than in the agency (or lack thereof) bestowed to the player to influence their character and World State.

II. Damnatio Memoriae

No, that’s not the name of an Antivan Crow (though I wouldn’t blame you for thinking so, since we have a character named “Lucanis Dellamorte”). It’s a Latin phrase meaning “condemnation of memory”, applied to a reviled person by destroying records of their existence and defacing objects of their legacy. In this case, it refers to the player. When it comes to their influence over the world and their in-game avatar, The Veilguard deigns to limit or outright eliminate it.

Save transfers that allow for the transmission of World States (the carrying over of choices from the previous games) have been a staple of the Dragon Age and Mass Effect franchises. Even when their consequences are slight, the psychological effect that this personalization has on players is profound, and one of many reasons why fans grow so attached to the characters and world. At its core, it’s an illusion, but one that’s of similar importance to the illusion that an arbitrary collection of 1s and 0s can create an entire digital world. Player co-authorship guarantees a level of emotional investment that eclipses pre-built backgrounds.

However, The Veilguard limits the scope to just three choices, a dramatic decrease from the former standard. All import options come from Inquisition, with two just from the “Trespasser” expansion. One variable potentially impacts the ending, while the other two, in most cases, add one or two lines of dialogue and a single codex entry. Inquisition, by contrast, imported a bevy of choices from both previous games. Some of them had major consequences to quests such as “Here Lies the Abyss” and “The Final Piece”, both of which incorporated data from two games prior. The Veilguard is decidedly less ambitious. Conspicuously absent options include: whether Morrigan has a child or not, the fate of Hawke, the status of the Hero of Fereldan, the current monarchs of Fereldan and Orlais, the current Divine of the southern Chantry, and the individual outcomes of more than two dozen beloved party members across the series. Consequently, the fourth installment awkwardly writes around these subjects – Varric avoids mentioning his best friend, Hawke, as does Isabela ignore her potential lover. Fereldan, Orlais, and the Chantry are headed by Nobody in Particular. Morrigan, a prominent figure in the latest game, makes no mention of her potential son or even her former traveling companions. And the absence of many previous heroes, even ones with personal stakes in the story, feels palpably unnatural. I suspect this flattening of World States into a uniform mold served, in addition to cutting costs, to create parity between multiple cooperative players during the initial live-service version of Morrison. Again, the compromises of the troubled production become apparent, except this time, they’re taking a bite out of the core narrative.

Moreover, the game’s unwillingness to acknowledge quantum character states means that it’s obliged to omit several important cast members. At this point, I would’ve rather had them establish an official canon for the series rather than leaving everything as nebulous and undefined as possible. That way at least the world would’ve felt more alive, and we could’ve gotten more action out of relevant figures like Cassandra, Alistair, Fenris, Merrill, Cole, and Iron Bull. Not to mention that The Veilguard’s half-measure of respectful non-intereference in past World States ultimately fails. Certain conversations unintentionally canonize specific events, including references to Thom Rainier and Sera, both of whom could go unrecruited in Inquisition, as well as Morrigan’s transformation into a dragon in the battle with Corypheus in that game’s finale. But whatever personal history the player had with them doesn’t matter. The entire Dragon Age setting now drifts in a sea of ambiguity, its history obfuscated. It feels as gray and purgatorial as Solas’s prison for the gods.

Beyond obscuring the past, The Veilguard restrains the player’s agency over the present. When publications first announced that the game would allow audiences to roleplay transgender identities and have that acknowledged by the party, I grew very excited – both at the encouraging representation, and at the depth of roleplaying mechanics that such an inclusion suggested. Unfortunately, The Veilguard offers little in roleplaying beyond this. The player character, Rook, always manifests as an altruistic, determined, friendly hero, no matter what the player chooses (if they’re offered choices at all). The selections of gender identity and romantic partner constitute the totality of how Rook defines themselves, post-character creation – exceptions that prove the rule of vacancy. Everything else is set in stone. The options presented are good, and should remain as standard, but in the absence of other substantive roleplaying experiences, their inclusion starts to feel frustratingly disingenuous and hollow, as if they were the only aspects the developers were willing to implement, and only out of obligation to meet the bare minimum for player agency. In my opinion, it sours the feature and exudes a miasma of cynicism.

Actual decisions that impact the plot are few and far between, but at least we have plenty of dialogue trees. In this type of game, dialogue options might usually lead to diverging paths that eventually converge to progress the plot. You might be choosing between three different flavors of saying “yes”, but as with the World States, that illusion of agency is imperative for the roleplaying experience. The Veilguard doesn’t even give you the three flavors – the encouraging, humorous, and stern dialogue options are frequently interchangeable, and rarely does it ever feel like the player is allowed to influence Rook’s reactions. Relationships with companions feel predetermined, as the approval system has no bearing on your interactions anymore. There are so few moments for you to ask your companions questions and dig in deep compared to Inquisition. Combined together, these issues make me question why we even have dialogue with our party at all. Rook adopts the same parental affect with each grown adult under their command, and it feels like every conversation ends the same way irrespective of the player’s input. With the exception of the flirting opportunities, they might as well be non-interactive cutscenes.

Rook’s weak characterization drags the game down significantly. With such limited authorship afforded to the player, it’s difficult to regard them as anything more than their eponymous chess piece – a straightfoward tool, locked on a grid, and moving flatly along the surface as directed.

III. Dull in Docktown

On paper, a plot summary of The Veilguard sounds somewhere between serviceable and phenomenal: Rook and Varric track down Solas to stop him from tearing down the Veil and destroying the world. In the process, they accidentally unleash Elgar’nan and Ghilan’nain, two of the wicked Evanuris who once ruled over the elven people millenia ago. With Solas advising them from an astral prison, Rook gathers a party together to defeat the risen gods, along with their servants and sycophants. Over the course of the adventure, they uncover dark truths about the origins of the elves, the mysterious Titans, and the malevolent Blight that’s served as an overarching antagonistic force. Eventually, Rook and friends join forces with Morrigan and the Inquisitor, rally armies to face off with their foes, and slay both the gods and their Archdemon thralls before they can conjure the full terror of the Blight. As Solas once again betrays the group, Rook and company have to put a decisive stop to his plans, which could potentially involve finally showing him the error of his ways.

The bones of The Veilguard’s story are sturdier than a calcium golem. Problems arise when you look at the actual writing, dialogue, and characterization – the flesh, blood, and organs of the work.

I’ve seen others chide the writing as overly quippy, but that better describes previous titles. Rather, I think The Veilguard’s dialogue is excessively utilitarian and preliminary, like a first draft awaiting refinement. Characters describe precisely what’s happening on screen as it’s happening, dryly exposit upon present circumstances, and repeat the same information ad nauseum. This infuriating repetition does little to reveal hidden components of their personalities, or their unique responses to situations. You won’t hear anything like Cole’s cerebral magnetic poetry or Vivienne’s dismissive arrogance. Many exchanges could’ve been uttered by Nobody in Particular, as it’s just dry recitation after recitation. It almost feels like watching an English second language instructional video, or a demonstration on workplace safety precautions. Clarity and coherence come at the cost of characterization and charisma.

Words alone fail to make them interesting. Most companions lack the subtlety and depth I had come to expect from the franchise, with many conversations amounting to them just plainly stating how they’re feeling. Most rap sessions sound like they’re happening in a therapist’s office with how gentle, open, and uncomplicated they feel. Compare this to Inquisition, where every character has a distinct voice (I should know, I had to try to copy them for that stupid application), as well as their own personal demons that it betrays: Sera’s internalized racism, hints of Blackwall’s stolen valor, Iron Bull’s espionage masked by bluster, or Solas’s lingering guilt and yearning for a bygone age. These aspects of their characters aren’t front and center, but things the audience can delve into that gives every moment with them more texture. The Veilguard’s companions lay out all their baggage carefullly and respectfully upfront, whether it’s Taash’s multiculturalism and gender identity issues or Neve’s brooding cynicism towards Tevinter’s underbelly. You’ve plumbed the depths of their personas within the first few minutes of meeting most of them.