#masculinity

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

⬆️⬆️⬆️ gotta keep all these in there

“hes a woman to me” IS HE? or are you equating women with submissive character traits you've arbitrarily put on a random man

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

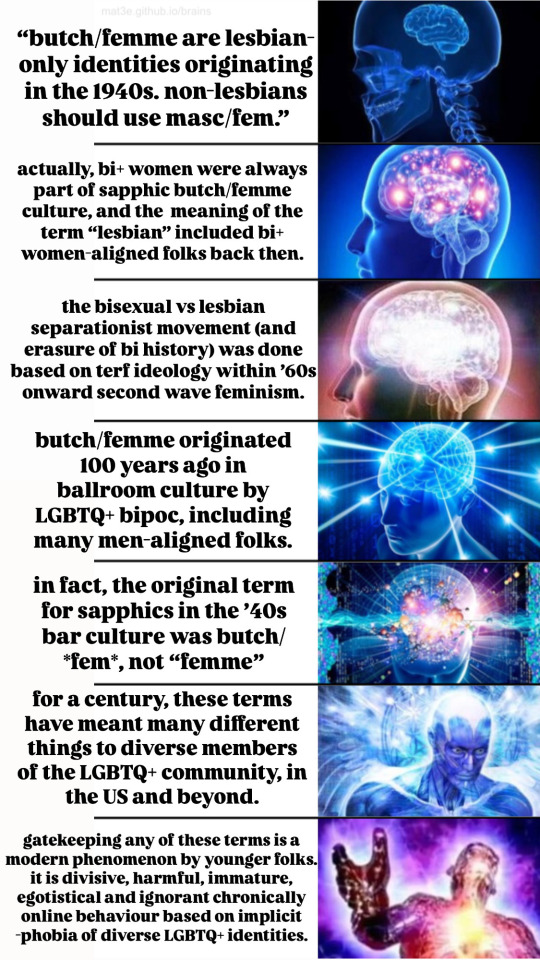

I learned a lot today from Obviously Queer’s video essay “FEMME: Lesbian History, Identity, Politics and Invisibility” and femmebis’ “The “Lesbian-Only Term” Myth: A Comprehensive Historical Essay on ‘Butch’ and ‘Femme’ ”.

#sapphic#butchfemme#wlw#lesbian#bisexual#honestly i could make another one of these just about what femme can mean to different folks#lgbtq+#femme#butch#masc#fem#bipoc#queer#queer bipoc#bi+#mspec#bi#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbt+#gay#lesbian bars#ballroom culture#genderqueer#masculine#feminine#masculinity#femininity#butch4femme#femme4butch

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Danny Delanox

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

cocky swole flex mix

#shredded#bodybuilding#jock#bodybuilders#teen muscle#teen bodybuilder#muscle#muscles#male physique#male beauty#abs & pecs#sixpack#masculinity#gay men#meninos#homens#bro#bicep flex#biceps

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two butches playing pool, from Sophia Wallace's "Girls will be Bois" series, 2002–2007.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

happy pride to every male & masc queer who feels alienated from the community during pride month. many places are taking to create "she+" and "femme & them" type events that conflate non binary identities with womanhood without creating similar spaces and events for mascs & men, leaving many trans men and mascs to feel totally alienated because their is no designated day or space for them to celebrate. while it's great to celebrate femininity & womanhood, we should be celebrating queer manhood and masculinity alongside it. it's important to have groups and events for all members of our community

if you feel alienated because you don't fit into these spaces, happy pride to you. happy pride to the butches and lesboys who don't feel safe going to lesbian events because of this. happy pride to trans mascs & men who don't have a space to go or a day to celebrate themselves. happy pride to non binary queers, genderqueer people and gnc people who are not feminine or female and have nowhere to go. happy pride to masculine and male intersex people who can't exist in the spaces they want to.

happy pride to cis masc and male queers who feel completely estranged from the community. happy pride to trans girls who are also men who cannot express their manhood at the risk of people using it as a weapon to misgender you. happy pride to the bigender and multigender people who are have to prioritize their feminine or female identities in order to make other people "feel safe." happy pride to the genderfluid people who don't get to talk about their masculinity or manhood. happy pride to the masc gays who feel alienated

we deserve to celebrate ourselves as well. take care of yourself this pride month

#nonbinary#transmasc#trans#transgender#trans man#genderqueer#ftm#transmasculine#intersex#genderfluid#non binary#enby#gay#lesbian#bisexual#bear#gay bear#masculinity#transman#transmen#lesboy#butch lesbian#guydyke#pansexual#multigender#bigender#our writing#pride month 2024#pride 2024#pride

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Danny and Valentin

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

The young men in our study were between the ages of 14 and 17 from families with low incomes and lived in high-crime neighborhoods. They were split into three groups. The first group received money on reloadable gift cards every week. The second group was offered an after-school program and received money on a gift card as long as they attended the first few sessions. The third group served as a comparison or “control,” and participants were able to take advantage of the programming after the completion of the study. When asked about how they spent the money they had received, participants reported a variety of expenses. Some spent it on personal items and entertainment like clothes, video games, and activities such as amusement parks. Others reported using the money for necessities, such as helping out a parent with groceries or fixing a car. Some participants reported that they saved the money to reach goals such as purchasing a car or helping their family move out of their neighborhood and purchase a house. Receiving the cash transfer alone led to an increase in healthy behaviors. Participants who received the cash transfer were less likely than the control group to do things like drink alcohol, use marijuana, take prescription medication without a prescription, be in a physical fight, carry a weapon, or use a vapor product. Some participants said they felt the extra money helped them to perform better in school by allowing them to buy supplies, and others felt that the cash alone helped reduce crime. We also found that the cash transfer plus programming improved the financial health of participants, which may be because the after-school programming included financial education. Beyond the benefits of the cash, the young men who were offered and attended the after-school program noted that having a safe, neutral space to go after school helped them stay away from the violence in their neighborhoods.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

After reading the wiki pages dedicated to both femininity and masculinity I've come to the conclusion that, everything everyone does is wrong unless you are the exact same as what the people in power personally want you to be.

You're a masculine woman? Bad.

You're a feminine woman? Ew. You're a woman. Bad.

You're an androgynous woman? Bad.

You're a masculine man? Well you're not masculine enough. Bad.

You're a feminine man? ✨Gay.✨ Which is bad.

You're an androgynous man? Bad.

In conclusion:

DRESS AND PRESENT HOWEVER THE FUCK YOU WANT BECAUSE SOMEONE WILL ALWAYS HAVE A PROBLEM WITH IT.

"women get praised for masculinity!" women cant even have leg hair because its perceived as masculine (despite the fact all genders grow leg hair) so i genuinely dont know where this rancid ass take came from. have you met a woman. have you ever asked a woman about their experience with society in regards to presenting in perceived masculine ways. i dont think you have.

#trans masculinity#trans masc#masculine#masculinity#trans femme#trans feminine#trans fem#feminine#femininity#androgynous#presentation

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Prison-Based Animal Programs: Cats, Inmates, and Masculinity

by Sophiane Nacer, Metropolitan State University of Denver

I. Introduction

Prison-based pet programs (PAPs) are a relatively new phenomenon, though interactions between prisoners and animals are anything but (Furst, 2006). PAPs present an opportunity for inmates to engage in meaningful work and give back to the community while also experiencing the therapeutic effects that animal companionship provides (Fournier, 2016). However, there may be more to PAPs than meets the eye. In a prison environment where the inmate code legitimizes the destructive ideals of toxic masculinity, opportunities to practice compassion, empathy, vulnerability, and emotional breadth can be vital to preventing inmates from recidivating upon release (Fournier, 2016). PAPs that use cats may be particularly helpful in inmate resocialization, rehabilitation, and reintegration due to the traditional association between felines and femininity that provides the unique potential to dismantle destructive masculine ideas, ideals, and behaviors in inmates (Fournier, 2016).

II. Hegemonic Masculinity and Toxic Masculinity

Hegemonic masculinity is defined as the dominant notion of masculinity in a given context, both historical and geographical, that is comprised of both prosocial and antisocial notions of masculine expectations (Kupers, 2005). Fatherhood, pride in accomplishments, self-reliance, courage, and action-orientation are all examples of masculine attributes that are culturally accepted and valued (Fournier, 2016). Misogyny, ruthless competition, devaluation of feminine attributes, a need to dominate and control others, a readiness towards anger and violence, and hierarchical intermale dominance, are all examples of socially destructive masculine attributes that are perpetuated by the contemporary hegemonic masculine standard (Kupers, 2005). The term toxic masculinity is used to delineate these destructive attributes from the prosocial ones, creating a constellation of socially regressive male traits (Kupers, 2005).

Toxic masculinity is literally coded into prison life as the “inmate code”, which dictates that a “real man” or a “stand-up con” does not display weakness, does not display emotion other than anger, does not depend on anyone nor display any vulnerabilities, and is quick to violence to defend his place in the prison hierarchy (Kupers, 2005). Men who may not have displayed any overtly toxic masculine behaviors on the outside are forced to adapt to the culture of hypermasculine posturing and violence as a way to survive, through a process known as prisonization (Fournier, 2016). Toxic masculinity within prisons is also reinforced by the institution itself. Both inmates and staff, particularly correctional officers, are expected to be tough, show no vulnerabilities, constantly engage in an intermale struggle for power, and solve problems through brute force (Kupers, 2005). A key example of this is the practice of cell extraction, in which inmates and officers, dressed in riot gear and heavily armed, engage in an acute fight for dominance (Kupers, 2005). Inevitably, cell extractions serve to confirm an inmate’s loss of power and control, two things toxic masculinity requires of a “real man”. With no other acceptable or attainable means of confirming his masculinity, the inmate seeks to overpower and control weaker inmates through acts of violence, such as rape and other forms of physical assault (Fournier, 2016).

The internalization of and socialization to prison’s culture of toxic masculinity is deeply harmful, both to the inmate himself and to society. Six out of seven inmates will be released back into society after serving their prison sentence, making the need for effective rehabilitation and tools for reintegration critical to decreasing recidivism and social harm (Nellis, 2021). However, the shift from rehabilitation to incapacitation and confinement seen in the 1970s coupled with male resistance to therapy has deeply impaired the ability to counter these devastating effects of prison (Kupers, 2005).

III. Men, Mental Health, and Prison

The 1970s not only marked the transition from rehabilitation to incapacitation, but it also marked the beginning of a massive increase in incarceration (Kupers, 2005). As the prison population has quadrupled in the last three decades so has the proportion of inmates needing treatment for significant emotional and psychological problems, a trend attributed to deinstitutionalization, tough-on-crime initiatives, and a shrinking public mental health budget (Kupers, 2005). Prison mental health resources have failed to increase alongside their ever-growing population, meaning that said resources are typically reserved for only the most serious cases, such as prisoners suffering from acute psychosis, suicidal ideation or attempts, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder (Kupers, 2005). This leaves many individuals, including those court-ordered to attend therapy for anger management, sex offenses, and substance abuse, without any recourse (Kupers, 2005).

Further compounding the limitations of prison mental health treatment is the lack of confidentiality and privacy. Oftentimes, particularly in maximum security units where prisoners are confined to their cells for 23 hours per day, there is inadequate staff to facilitate transport to and from private treatment areas (Kupers, 2005). As such, “cell front” therapy has become increasingly popular (Kupers, 2005). Cell front therapy occurs with the inmate talking to their mental health provider through their cell door, in full view of neighboring inmates and passing correctional officers (Kupers, 2005). This prevents any measure of confidentiality and may put the prisoner at risk depending on the topic being discussed. Institutional rules surrounding mandatory reporting further compromise the privacy of the inmate and any confidentiality cell-front therapy could provide (Kupers, 2005). Lack of resources paired with poor confidentiality serves as external barriers to prisoners obtaining necessary treatments, though these are not the only barriers.

Men, both outside and inside of prison, tend to underreport emotional and psychological distress, only seeking help when things have reached a point of crisis (Kupers, 2005). This reluctance to seek mental health treatment has been attributed to toxic masculinity, in that it encourages men to repress all emotions other than anger and avoid actions that could be interpreted as dependency or weakness (Woodson, 2019). To succeed in therapy, men must reject a certain amount of the hegemonic masculinity that they have been socialized to since childhood, and in doing so place themselves in a position of rare vulnerability (Kupers, 2005). This is especially difficult for incarcerated men, who are subjected to toxic masculinity at a far greater intensity yet who are also most in need of treatment. Studies have shown that over half of all inmates in US jails and prisons suffer from mental illness, a rate 2-4 times higher than the general population (Satlin, 2013). Suicide rates are also high amongst the incarcerated population at 46 in every 100,000 in US jails (Carson, 2020a) and 21 per every 100,000 in US prisons (Carson, 2020b), compared to 13.4 per every 100,000 in the general population as of 2016 (Suicide, 2021). Men represent 85.7% of jail suicides (Carson, 2020a), 96.2% of prison suicides (Carson, 2020b), and are 3.7 times more likely to commit suicide than women amongst the non-incarcerated US population (Suicide, 2021).

Mental health services in US correctional facilities today are ineffective, unsafe, and in dire need of both reformation and increased funding. Society’s idealization of traditional masculinity, the most destructive traits of which are perpetuated by pervasive toxic masculinity, has created a significant barrier to men seeking the help they need (Kupers, 2005). The exaggerated form of toxic masculinity that exists within prisons, reinforced both by the inmate code and the institution itself, is directly antithetical to the purpose of corrections as prisoners adopt antisocial traits as a survival technique rather than prepare prosocial coping mechanisms for their eventual reentry into society (Woodson, 2019). For as long as the incapacitation model remains favored, it is unlikely that we will see drastic restoration to rehabilitative efforts. However, prison-based animal programs offer some hope of not only facilitating therapeutic efforts but also minimizing the assimilation of toxic masculine traits and preparing inmates for successful reintegration.

IV. Prison-Based Animal Programs

Inmates and animals have a centuries-old history of interaction. Whether its pigeons, lizards, mice, or cats, inmates have shown an appreciation for animals that has surpassed that of the non-incarcerated (Furst, 2006). Researchers studying inmate poetry commented that “perhaps the scarcity of opportunities to develop relationships with non-inmates and the difficulties inherent in connecting with fellow prisoners are responsible for the striking number of poems about the importance of animals" (Furst, 2006). One of the most famous displays of animal admiration from an inmate is that of Robert Stroud, the “Birdman of Alcatraz”, whose rearing of canaries in Leavenworth Federal Prison led him to be recognized as a published ornithologist while incarcerated (Strimple, 2003). There are also less famous cases, such as the first successful prison-based animal program that was established accidentally in 1975, when inmates at Lima State Hospital for the Criminally Insane found and cared for an injured sparrow (Strimple, 2003). After noticing an improvement in inmates’ cooperation with each other and staff, the hospital initiated a year-long comparison study between two identical wards, with one allowing pets and the other not (Strimple, 2003). They found that inmates residing in the pet ward required half the amount of medication, had fewer violent incidences, and had no suicide attempts where the non-pet ward had eight (Strimple, 2003). Considering the body of research that exists supporting the use of animal-assisted therapy in individuals with both physical and psychological illnesses, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, anxiety, PTSD, and depression, these results showed that animals could have the same beneficial effects for a criminal population (Furst, 2006). This prompted other institutions to create their own prison-based animal programs (PAPs), and by 2006 a nationwide survey of PAPs found that there were 159 PAP sites in forty-six participating states (Furst, 2006). Although this number has continued to grow, a more recent survey has not yet been conducted.

PAPs are generally categorized into eight different models- visitation programs, wildlife rehabilitation programs, livestock care programs, pet adoption programs, service animal socialization programs, vocational programs, community service programs, and multimodal programs (Furst, 2006). The most common PAP design found in the study was the community service model (33.8%), in which participating inmates train and care for companion animals that are then adopted out to the community, followed by the service animal socialization model (21.1%), which typically train dogs to assist individuals with disabilities (Furst, 2006). 66.2% of PAPs used dogs, followed by cattle (12.7%) and horses (12.7%), where only 1.4% used cats (Furst, 2006). The majority of PAPs required interviews prior to participation (71.8%) as well as a history of good behavior or standing within the institution (54.7%) (Furst, 2006). 59.2% excluded inmates charged with certain crimes, most commonly crimes against animals (59.5%) and sex offenses (45.2%) (Furst, 2006). Funding for PAPs was reported to come primarily from fundraising (52.1%) amongst inmates, staff, the public, and privately-owned companies like PetCo, Petsmart, and Walmart, with further donations received through the humane society, shelter, or rescue with whom the prison partnered (Furst, 2006).

When asked if they would recommend PAPs to other prison administrators, 60 out of the 61 respondents (98.4%) confirmed that they would, with the one exception commenting that although beneficial to the inmates the programs are not revenue-generating (Furst, 2006). In support of their recommendation, respondents noted that PAPs had many benefits for inmates, including instilling a sense of responsibility and heroism, teaching job skills and parenting skills, providing meaningful work, encouraging patience, boosting self-esteem, reducing violent incidents, and decreasing anxiety amongst both inmates and staff (Furst, 2006). These attributes seem to run in direct contradiction with prison’s culture of toxic masculinity, by substituting it with a culture of compassion, community-mindedness, cooperation, and patience. A study that surveyed both program participants and members of the general prison population who interacted with PAP animals found that inmates “were more nurturing than aggressive, more expressive than stoic, and more cooperative than competitive” (Fournier, 2016). Participants also demonstrated an increased range of emotions which they openly expressed in the presence of others- discussing the joy of successes, the patience required for training, and the grief that comes when their dogs got adopted- something quite different than the heavily constricted expressions of emotion dictated by the inmate code and even normative hegemonic masculinity (Fournier, 2016). PAPs provide inmates with the opportunity to practice healthy masculinity through dedicating their time and efforts to the care of PAP animals. In return for their efforts, inmates are given unconditional positive regard and companionship, enabled to receive and give physical affection, and provided a confidant in an isolating, lonely, and treacherous environment (Fournier, 2016).

When asked, administrators at facilities with PAPs said that there were no downsides to the program (60%), with only 10.1% citing staff resistance as the only negative, rather than a flaw in the program itself (Furst, 2006). Anecdotally, administrators believed that recidivism amongst PAP participants was drastically lower than the general prison population, but no empirical studies have yet been performed to confirm this (Furst, 2006). With more than 2 million people incarcerated in the US and more than 6.5 million pets who become homeless every year the overwhelming support for PAPs presents a promising, life-saving option (Pets by the Numbers, 2020). PAPs, particularly the community service model in which prisons partner with animal shelters and rescues, are an opportunity to help both animals and prisoners by encouraging the unique bond that has long existed between the two and giving a second chance to two populations in dire need of one.

V. The Evolution and Perception of Cats

Cats were improbable candidates for domestication. Wild cats are territorial and live a solitary existence outside of mating and rearing young, making them the only domesticated asocial animal, though the extent to which cats are truly domesticated remains up for debate (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). Dog domestication began 27,000 to 40,000 years ago after humans, living as nomadic hunter-gatherers, found utility in less fearful wolves as barking sentinels and began a long process of artificial selection (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). Cats, on the other hand, do not appear to have been artificially selected by humans at all. Instead, approximately 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, they pioneered their own domestication through natural selection after having seen the benefit of hunting near human granaries and settlements (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). In this sense, cats co-evolved alongside humans, where dogs evolved under direct human influence.

In addition to their asocial origins and relatively short period of self-domestication, cat behavior is shaped by their status as both predator and prey (Dowling, 2020). Renowned for their hunting skills, cats have traditionally been used to deter mice and other pests; however, their small size places them at risk of being hunted by predators such as large canids, birds of prey, larger felines, and other carnivores (Driscoll, MacDonald, & O’Brien, 2009). As such, cats tend to be cautious, especially in new situations, and have developed a sophisticated body language that masks signs of physical and psychological distress in an effort to avoid predation (Dowling, 2020). This leaves many non-cat-savvy people with the impression that cats are unfriendly, unapproachable, and unpredictable, when in fact cats are simply outliers (Dowling, 2020).

Oftentimes the principal mistake people make when trying to understand cats is to compare them to another very popular pet- dogs. Dogs, who have undergone many years of domestication during which friendliness and obedience were intentionally selected for, are prosocial predator animals who tend to be confident, approachable, and expressive (Dowling, 2020). Over the course of their evolution, dogs even evolved a special orbital muscle that allows them to mimic the facial expressions of human infants; cats, lacking this muscle, are often denigrated as having “blank stares” or “evil eyes” (Dowling, 2020). Research has shown, however, that there is no difference in the strength of bonds that cats and dogs form with their owners, nor is there a difference in the health benefits owning either provides in terms of lower rates of anxiety and depression, better cardiovascular health, and self-esteem (Dowling, 2020).

VI. Felines and Femininity

The oldest example of cats and femininity being linked together is found in Bastet, the cat goddess of fertility, domesticity, childbirth, and sexuality (Mark, 2016). Bastet and the cats of ancient Egypt, a relatively egalitarian society, were revered by both men and women (Mark, 2016). As time progressed, however, the association between cats and femininity persisted while the reverence was lost.

In 1891 F. B. Harrison, a statesman who would later become the Governor-General of the Phillipines, wrote in The Journal of Education:

"The fiery spirit, the loud bark, the watchful temperament of the dog give him always a male aspect; and the sleek sleepiness, the treble mew, the spiteful deceit of the cat combine to render her female in character." (Gleeson, 2016)

By the 19th century, a distinct trend could be noticed in English writing where cats were associated with women and the feminine, while dogs were associated with men and the masculine (Gleeson, 2016). Unlike ancient Egypt, cats and women were not elevated through this comparison. Instead, traits such as aloofness, disloyalty, unpredictability, greed, selfishness, hypersexuality, pettiness, and spitefulness were attributed to cats and the women who were said to resemble them (Smith, 2009). Single women with one or more cats were- and still are- derogatorily labeled “crazy cat ladies”, physical altercations between women are called “cat fights”, and sexually aggressive women are “cats in heat” (Smith, 2009). Furthermore, associating a man with cats- and, by extension, women- is used to challenge his masculinity. Calling a man a “pussy” is considered a grave insult for its association with both female genitalia and cats, and is a sure way to start a fight (Smith, 2009). Even just owning a cat can cause a man to be seen as less masculine, gay or, according to a recent study, less datable (Kogan & Volsche, 2020).

This delineation separating men from cats is an example of toxic masculinity’s drive to separate all things male from all things female, lest a man’s masculinity be degraded by feminine associations (Smith, 2009). Dogs are “man’s best friend”- action-oriented, quick to please, and obedient- one does not usually have to work hard to gain a dog’s affection, or at least not as hard as one might have to work for a cat’s (Gleeson, 2016). This dynamic caters to toxic masculinity, which has taught men that they should not have to work hard for anyone’s affection; instead, women- and animals- should flock to them and vie for their attention (Gleeson, 2016). According to these same standards, both cats and women are small, weak, and difficult to handle (Smith, 2009). This makes them legitimate targets for abuse, which can be used to affirm masculinity when men feel powerless or when he needs to prove his masculinity to his peers (Smith, 2009).

However, a new movement- prompted by urbanization, apartment living, and social media- is encouraging men to discard this toxic interpretation of masculinity and “embrace a gentler, more thoughtful kind of masculinity” through cat ownership (Gleeson, 2016). Male cat owners in Australia were found to be 24% more likely to vote for liberal candidates, 29% less likely to believe homosexuality is immoral, and more likely overall to read and play boardgames (Gleeson, 2016). This indicates that, in addition to embracing a traditionally feminine pet, they have globalized their disregard for masculine ideas, such as conservativism and homophobia. While we cannot say which one caused the other- if owning a cat prompted them to adopt a non-traditional masculine identity or if adopting a non-traditional masculine identity prompted them to own a cat- the correlation suggests that associating with cats may do more to combat toxic masculinity than with other animals (Gleeson, 2016).

VII. Prison-Based Cat Programs

While still extremely rare, the number of cat PAPs has increased from the solitary program noted in the 2006 PAP survey (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). Perhaps the most famous is Indiana State Prison’s cat adoption program where inmates in the maximum-security prison, including those on death row, can apply to adopt a cat from the local animal shelter- a privilege so popular amongst inmates that there is an extensive waitlist (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). The program is funded by the inmates themselves, who are expected to keep a job and pay for all associates expenses, with many choosing to make their own cat furniture and toys as well (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). With the exception of death row inmates, who are prohibited from interacting with others, cats are permitted to wander the cell block under their owner’s watchful eye to interact with inmates who do not have cats of their own (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). This program is one of the few PAPs that are therapeutically focused, in that the element of community service comes secondary to the long-term benefits inmates receive from permanently adopting a cat (Furst, 2006). Maleah Stringer, the executive director of the Animal Protection League, the shelter partner that provides cats to the prison, says:

“There’s no more risk of the animals being hurt in prison than there is when we adopt to the normal public. The guys stay out of trouble because they know if they get in trouble, they’re going to lose the program. We’ve had more issues with mistreated animals coming back from adoptions than we ever do from the prison program.” (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020)

Seeing the success of this program- including a significant decrease in violent incidences and improved mental health among inmates and staff- another cat PAP was established at the Pendleton Correctional Facility, another maximum-security prison in Indiana (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). This program operates using a community service model where inmates prepare cats for public adoption (Furst, 2006). The cats remain in a community room rather than in individual cells, and inmates report to the room every morning for their work hours (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). Inmates in this PAP along with other cat PAPs focus on socializing cats, building their confidence, addressing any acute behavioral issues, and teaching them basic tricks (O’Conner, 2020). Socialization is particularly important for feral cats, semi-feral cats, and cats who have undergone traumatic events or circumstances, all of whom make up a large percentage of homeless cats (O’Conner, 2020).

The process of socializing a cat is very rewarding but requires an excess of patience and the understanding that cats will acclimate on their own time rather than yours (O’Conner, 2020). This is one of the attributes that perhaps most differentiates cats from dogs, and may prove even more effective when it comes to socializing inmates towards prosocial behaviors and away from toxic masculinity. Patience, empathy, and compassion are exercised in any PAP, but seem to be especially pronounced in inmate interactions with cats (O’Conner, 2020). Dog PAPs are centered around obedience training and task-completion, which actually reinforces some aspects of toxic masculinity- such as a need for control and dominance over others (Fournier, 2016). Recognizing and adapting to the needs of others is a critical skill for prosocial interactions and reintegration, both of which are necessary when working with cats (Kupers, 2005).

Cats being a symbol of femininity and their traditional role as “women’s pets” also presents a unique opportunity to overcome toxic masculinity (Gleeson, 2016). Cat PAPs allow inmates to safely embrace a kinder, more compassionate culture of masculinity through their acceptance rather than degradation of a feminine symbol. The value inmates assign to animals, for their nonjudgmental and affectionate companionship, makes cats an ideal form through which to introduce non-hegemonic masculinity into a hypermasculine environment where displays of femininity are traditionally met with violence (Fournier, 2016). In theory, through this introduction, global improvement would occur to the point where the inmate is not influenced by the ideals of toxic masculinity in either choosing his pet, nor in his actions, choices, and opinions (Fournier, 2016). This theory is supported by the aforementioned survey of Australian “cat men”, who showed a global denunciation of toxic masculinity in their rejection of homophobia, conservativism, and stereotypical male hobbies (Gleeson, 2016). This globalized version of healthy masculinity may also remove some of the barriers that prevent successful mental health care within prisons; although cats can do little to increase the funding available to prison mental health services, their promotion of healthy masculinity may leave inmates more open to therapeutic intervention and, if nothing else, can serve as the most confidential of confidants (Kupers, 2005).

Finally, cats are well-suited to the structural limitations that prisons impose. Cat- more than dogs- can live in cells where space is limited and outdoor exercise may not be guaranteed (Can you have a cat in prison?, 2020). They also do not require frequent outdoor access, which decreases the need for staff involvement and makes them ideal for high-to-maximum security units where PAPs are otherwise difficult to accommodate (Kupers, 2005). While there has not been a survey comparing PAP expenses, it seems likely that cat PAPs incur fewer expenses given the amount the average cat owner spends yearly versus that which a dog, horse, or cattle owner spends (Pet Care Costs, 2017). In a time where prisons are looking for cost-effective methods to reduce recidivism, violent incidents, and mental illness amongst their populations, and animal shelters are looking for ways to save the 860,000 homeless cats euthanized each year, cat PAPs present a unique solution to both (Pets by the Numbers, 2020).

Conclusion

The culture of toxic masculinity degrades both women and cats while legitimizing their abuse as a way of affirming one’s masculinity (Smith, 2009). That same culture amplifies the physical and psychological dangers of confinement by creating intermale competition, encouraging violence and anger, and legitimizing the abuse of weaker inmates in the interest of confirming one’s power within prison walls (Kupers, 2005). In this way toxic masculinity serves to both manufacture and perpetuate violence, crime, and societal harm. Finding novel, inexpensive, and prosocial ways to combat the destructive aspects of hegemonic masculinity both within and outside of correctional facilities is critical, particularly in a time where rehabilitation is set aside in favor of incapacitation and funding is being diverted away from mental health resources to pay for an ever-growing prison population (Kupers, 2005). PAPs are on the forefront of innovative therapeutic methods that benefit both the participating inmates and the community at large (Fournier, 2016). Cat programs, although currently rare, should be considered especially effective for their potential to globally dismantle socialized toxic masculinity and prisonization.

Works Cited

Can you have a cat in prison? (2020, November 18). Retrieved May 01, 2021, from https://prisoninsight.com/can-you-have-a-cat-in-prison/

Carson, E. A., & Cowhig, M. P. (2020a). Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2016 – Statistical Tables (pp. 1-29, Rep. No. NCJ 251921). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. doi:https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mlj0016st.pdf?utm_content=mci&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

Carson, E. A., & Cowhig, M. P. (2020b). Mortality in State and Federal Prisons, 2001-2016 – Statistical Tables (pp. 1-24, Rep. No. NCJ 251920). Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. doi:https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/msfp0116st.pdf

Dowling, S. (2020, May 20). Why do we think cats are unfriendly? Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20191024-why-do-we-think-cats-are-unfriendly

Driscoll, C. A., Macdonald, D. W., & O'Brien, S. J. (2009). From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(Supplement 1), 9971-9978. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901586106

Fournier, A. K. (2016). Pen pals: An examination of human–animal interaction as an outlet for healthy masculinity in prison. Men and Their Dogs, 175-194. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-30097-9_9

Furst, G. (2006). Prison-based animal programs. The Prison Journal, 86(4), 407-430. doi:10.1177/0032885506293242

Gleeson, H. (2016, December 11). Hail the rise of cat men, an antidote to toxic masculinity. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-12-11/the-rise-of-cat-men-antidote-to-toxic-masculinity/8082618?nw=0

Kogan, L., & Volsche, S. (2020). Not the cat’s Meow? The impact of posing with cats on Female perceptions of Male Dateability. Animals, 10(6), 1007. doi:10.3390/ani10061007

Kupers, T. A. (2005). Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prison. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 713-724. doi:10.1002/jclp.20105

Mark, J. J. (2016, July 24). Bastet. Retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://www.worldhistory.org/Bastet/#:~:text=Bastet%20is%20the%20Egyptian%20goddess,associated%20with%20women%20and%20children.

Nellis, A. (2021). No End in Sight: America's Enduring Reliance on Life Imprisonment (pp. 1-45, Rep.). Washington, D.C.: The Sentencing Project. doi:https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/no-end-in-sight-americas-enduring-reliance-on-life-imprisonment/

O'Connor, G. (Director). (2020, November 19). The Cats that Rule the World: Prison Cat, Galileo [Video file]. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nqGvJlDO5Vo&t=14s

Pet Care Costs. (2017, May 17). Retrieved May 8, 2021, from https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/pet_care_costs.pdf

Pets by the numbers. (2020, December 26). Retrieved May 07, 2021, from https://humanepro.org/page/pets-by-the-numbers

Satlin, A. (2013, February 04). Mental illness soars in prisons, jails while inmates suffer. Retrieved May 9, 2021, from https://www.huffpost.com/entry/mental-illness-prisons-jails-inmates_n_2610062

Smith, S. E. (2009, September 26). Felinity and Femininity [Web log post]. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from http://meloukhia.net/2009/09/felinity_and_femininity/#:~:text=Today%2C%20of%20course%2C%20cats%20are,who%20like%20cats%20are%20emasculated.&text=Cats%20and%20female%20sexuality%20are,they%20are%20objectified%20and%20sexualized.

Strimple, E. O. (2003). A history of prison inmate-animal interaction programs. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(1), 70-78. doi:10.1177/0002764203255212

Suicide. (2021, May 2). Retrieved May 9, 2021, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide

Woodson, M. (2019). The Best We Can Be: How Toxic Masculinity Creates a Second Inescapable Situation for Inmates. Public Interest Law Reporter, 24(2).

983 notes

·

View notes

Text

not femininity or masculinity but a secret third thing (faggotry)

#this is my gender expression#shitpost#trans#transgender#queer#lgbtq#lgbtqia#mogai#transsexual#nonbinary#enby#genderfuck#genderqueer#genderfluid#genderflux#trans masc#trans femme#androgynous#neutrois#gay#femininity#masculinity#trans femininity#trans masculinity#9k#this got notes

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Young butch watched over by a poster of Bruce Lee, from Sophia Wallace's "Girls will be Bois" series, 2002–2007.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Natural body armor.

#alpha jock#alpha master#alpha god#alpha man#alpha muscle#gay hot#hot male#gay muscular#muscle men#flexing#bodybuilders#masculinity

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Independent journalist Vera Papisova talks about her experiences dating right-wing men for a magazine feature.

#badass women journalists hell yeah#tiktoks#vera papisova#right wing men#right wing radicalization#manosphere#masculinity

731 notes

·

View notes