... that aims to reveal the relentless scam that we call everyday life Julian • 29 • he/himapparently this blog is no longer property neither of Shadowhunters nor of Magnus Bane • I reblog stuff that I like and tag #myart and #mygifs for my own things • occasionally also #mystuff for anything else

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Hansry + touches

#kingdom come deliverance#hansry#this golden colour is pretty#but can i just divert a little and say how fucking much i love the physical intimacy in this game concerning every character?#the casual touches and hugs and even non-romantical kisses#the playful nudges and the putting-a-strong-hand-on-the-other‘s-shoulder-to-show-them-i‘m-glad-they‘re-still-here-with-me#it gets me every time especially since this level of being physical with each other is sadly something that is quite rare in american media#and we‘re all flooded with that so whenever i see sth like this it makes me feel like home#they greet each other with a hug. they take each other‘s hand. not as a demonstration of sexual desire but simply of friendship#it just feels so real. so honest.

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To the fucking task."

So originally, I just wanted to make some nice Samuel gifs (as one does when they have a shitty day, right?), but then I got stuck at this very moment here. At the way that Samuel walks up to Henry, stands next to him and waits. He has already made his decision at this point, has sent Sara off to safety, has his sword ready in hand. He will fight, one way or another, he does not need Henry's approval for that. And yet he stops for a while and looks at him. Waits until Henry says the words. Because this one little moment isn't about him. The Skalitz tune and the long shot of Henry's expression right before shows us that this here is all about Henry fighting his own battles. Not in the Jewish quarter, but in his head, in Skalitz, long in the past.

And Samuel's waiting and his nod afterwards is all about that too. It's the unspoken question of "Are you with me?", and the just as silent reassurance that "It's fine if you're not". It's the understanding of a shared grief. It's giving Henry the room to clear his mind and make his decision, one that is not directed at the past, but focused on the present. And Henry knows this, snaps out of his memories about his parents the very moment that Samuel, his father's son, walks up next to him.

It's the support of a brother. It's mishpokhe.

(And it's just one fucking shared look and it made me way too emotional, what is this sorcery??)

#kingdom come deliverance#kcd#kcd2#kcd2 spoilers#samuel#kcd samuel#henry of skalitz#my gifs#sorry for the little essay had to get my thoughts out and for once i did not want to do that in tags only#might still make the gifs i actually wanted to make at some point if you all ask for it nicely hehe

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

last two, janosh is a hemulen and adder is a mymble :o)

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source

39K notes

·

View notes

Text

Redefining Medieval RPGs - The KCD 2 Documentary

#have not managed to watch the documentary yet#but that second gif is so hans and henry coded. like both of them are absolutely in character here and i love it#tom mckay#luke dale#kingdom come deliverance

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

He's trying to make off with the silver!

#hans capon#kingdom come deliverance#he was so badass for this#the way he does it so completely unfazed#also ah damn it i don‘t have the time rn for a longer tag excourse but you made me with these gifs shame on you#it‘s not just the coolness he shows here. it’s the skill this takes.#the skill to watch and visualise and analyse#like he doesn‘t really dodge an arrow that‘s not how it works. it‘s about seeing your enemy and knowing when he‘s gonna shoot#and doing so in the middle of talking so his thoughts are even distracted a little#and it ties in so well with his characterisation of being both a vigilant hunter and someone who can read his surroundings well#hans has a deep understanding for emotion both for his own and those of others#he‘s also an incurable optimist which leads to him getting fooled again and again (like by brabant or by zizka at nebakov)#but overall he feels for and with people perhaps more than most of the other characters in the game#and that is something that definitely comes in handy in a battle situation#add to that his life-long experience of being a feral street cat getting into quarrels left and right#plus someon who despite enjoying (or trying to) life to the fullest showing a tremendously low self-preservation drive#and then you get this#a fucking skilled warrior

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hold your horses

#our boyyy#really love how plain (positively) this drawing is and yet it gets his features so perfectly right#samuel#kingdom come deliverance#kcd fanart#(i was so close to having henry say 'hold your horses' in that fic but there was no more room for horse jokes)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of Hogs and Horses

a little gift to @bad-system, i suppose. and to everyone else who cannot stand Henry's plant-nerd personality getting ignored any longer.

ao3 link

For a while, Henry stood in silence and admired her. He felt that he truly could not have been luckier. Just to be in her presence alone, to have been granted the chance to lay eyes on her. To touch and smell, and feel her even. Cautiously, of course, with his fingers covered decently by gloves, he would not want to get ahead of himself. To marvel at her unique beauty, her liveliness and elegance, the form of her long, slender body, her arms so carelessly stretched out in what seemed to be a sheer act of rebellion, her face so full and white. Such angelic grace, such godlike … Well, now that might be going a tiny bit too far.

Besides, if one had listened to his thoughts right now, they might mistake them for the adoration of a lover, when that was only part of the truth. No, way more than a lover, Henry felt like a mother. He had born her. Had been offered her seeds, harboured her in the safety of his womb, nourished her and now he could finally see her bloom.

Henry took a step back and smiled so broadly it almost hurt. A robin in the trees above his head, clearly unimpressed by his motherly feelings, decided to reinforce its ignorance by taking an extensive shit. Right on top of his beautiful creation.

“Oy!” he shouted up to the bird, wagging his fist. “Who do you think you are?” And when he walked over to his child again to check for any damages on her fragile head, he added: “This is an envoy from a distant realm, you hear me? I was a stranger and you invited me in. She's not so different to … Nah, I shouldn't say that, now, should I?”

It was true though. Not the Christ part, some might consider those ideas the roots of blasphemy, but Henry did not understand enough about church doctrines to judge that, nor did he care to know. But she was a stranger here, a traveller one could say, even when she had not travelled on her own feet.

Henry had just wanted to return from a visit to his brother, when he had run into his sweetheart's travelling companion, purely by chance, or by accident really, that hit the nail better on the head, but not quite perfectly. Blasius de Petragna had been standing in the middle of Kolin's main market square. With his hands on a horse's arse.

“He,” Henry had greeted him, looking down with slight amusement from Pebbles's back. “Good to see that you've finally got off your high horse.”

Blasius had rolled his glinting amber eyes at him. “It limps.”

“Looks more like it refuses.”

“Well, it had limped for a little while. But then it decided to capitulate for good.”

“Ah, I see. You backed the wrong horse then.”

Blasius's eyes had become a little narrower still, and his voice had been heavy with growing annoyance. “Your taunt is really not of any help here, Henry. I need to get this beast to move.”

“But why though? The Jewish quarter is practically,” he had turned around, so he could make a well-founded assessment, “a few dozen steps away.”

“What, and you think I just walk by myself and leave it here? In the middle of the market?”

“Yes, sure.”

“On a market day? For someone to fine me for parking violation?”

“So rather than paying a fee, you'd continue to beat a dead horse?”

“It's not dead y–” Blasius had stopped in the middle of the word, as he had noticed Henry's expression. “Ah, of course.” His face was as blank as the back of a monk's head. “Another one of your idiomata.”

“I'm sorry.”

“Then show me how sorry you truly are by helping me, good gracious!”

It had not taken long for Henry to accomplish what all of Blasius's pushing and cursing hadn't managed in almost half an hour, and all it had taken was an apple. As soon as he had held it in front of the horse's mouth, it had forgotten all about its pain and protest, and had followed him willingly, right through the gate of the Jewish quarter. Here, Henry had handed the apple over to the scholar, who clearly understood more about mapping and reading the stars than about animals. The rest he had to manage on his own, Henry had said. He had, after all, already paid his farewells to Sam rather extensively and fervently. Returning now was a little embarrassing, wasn't it? Almost as embarrassing as saying goodbye and then walking off into the same direction. Though that was a whole different disaster entirely.

Blasius had accepted his reasoning, and had assured that now that he knew the rather simple secret to a horse's heart, he would be able to guide it the last few steps. However, only because the secret was simple, it did not mean that it hadn't come of great use. So, he had concluded, a gift for Henry's effort was due. And then he had opened his saddle bag, and had pulled out a smaller leather bag from it, and then an even smaller satchel from that still. “In here, my friend, you will find a little seedling. A giant hogweed, that's what the shepherds of the montium Caucasi called it when they showed it to me. It's a beautiful plant once it's grown, but I did not take it with me for it's looks alone. It's a weapon, you see. A single touch of its blossom, leaves or its fluids works like a burning lens. Once the affected area of skin is exposed to direct sunlight, it will develop severe burns, even hours or days later. As if the devil himself had made an imprint on your body. I wanted to share it with Samuel, but since I know that you have your way with plants and alchemy as well, you might have just as much use for it.” Blasius had reached him the satchel, pulling it back slightly, just before Henry could take it. “Remember, friend, to be cautious. It is highly poisonous.”

“Ah.” Henry had taken the bag and regarded Blasius de Petragna with a way too satisfied grin. “Don't look a gift horse into the mouth, eh?”

That meeting in Kolín lay a few weeks back now. He had brought the seedling back home with greatest care and had planted it in the little herb garden he had built for himself. West of the city, right up the hill, close to where the gallows stood. Henry had claimed this spot about a year ago, as it provided everything he needed. Both the shadow of the trees and the warmth of the sun, since the area he had chosen was situated right on the edge of the forest. Solitude and seclusion, since all the talk about bad luck and damnation held most of the town's folk away. And a fertile ground, since … well, since apparently that was what even the most despicable criminal was good for, at least after his death.

Here, in the safety of the iron-enforced fence he had built around his garden, Henry had put the seedling into the ground. Just in front of the outer row of trees, next to the sage and rosemary. He was not entirely sure whether that direct sunlight was what the hogweed needed, but he thought that if its effects were amplified by the sun, it might just as well flourish in it. Besides, the position would serve as a natural defence against any vile plant thieves. Should they try to take it, they would be standing right in the sun when they did so, and that would cost them greatly.

Henry, of course, took all the precautions needed. And now, that the plant, his beauty, his child, had finally grown big enough to develop her first white, slightly unpleasantly pungent smelling blossoms, he grabbed his thick, old leather gloves and cut off some leaves and a part of the flower with a sigh and a heavy heart. From the parts that had been hit by the bird shit, he kept away as far as he could. He could not tolerate any impurity. Not when he wanted to find out how poisonous this hogweed truly could become, when dissected, crushed, burned and drowned on his alchemy table.

Whatever poison came about under Henry's examination was never put to the test. A war happened, and then another one, and then the poison was all forgotten. On a strange and winding path, one single phial of the apparent poison made it to the Wartburg in the city of Eisenach, where a mysterious knight going by the name of Junker Jörg was working on a book he later published as the September Bible. What Jörg used the phial's content for, was to remain his secret. A serving wench later claimed she had once seen him pour it into his inkwell, before unabashedly adding his own bodily waters to it. A cook working at the castle at the very same time was certain Jörg must have just drunken it all, and then he had dreamed, oh how strangely Jörg had dreamed, and in his nightmarish fevers had thrown the inkwell at the wall, piss or not.

The giant hogweed at the edge of the forest right next to the Rattay gallows, where the ground was fertile from ash and rotting flesh, remained a secret as well, for many, many years. Around four centuries, that was. Only then, in the time of exuberance and delusions of grandeur, did a travelling Frenchman, who did not care about damnation or the bad luck of the place – of course not, he was French after all – stumble across the beautiful, tall, elegant, white-headed child of a cartographer from Ragusa and a blacksmith from Skalitz. He took it home with him and planted it in his garden. Finding much joy in its impressive appearance, but swearing never to return to the Kingdom of Bohemia again, as the sun just burned differently there, judging by the vicious wounds on his skin. Just as much delight in the new addition to his pleasure garden did the Frenchman's friends take. And then their friends after that.

Just a few more years later, the hellish flower had spread over most of Europe, with the consequences still unknown to its admirers. Like a proper weapon, one might say. Or, as another man would call it, like a Trojan horse.

#kingdom come deliverance#kcd#henry of skalitz#blasius de petragna#that's it that's really all the characters in this little drabble#and that one unnamed frenchman and junker jörg but pff those are just unimportant side characters in our world's fate am i right?#for such a tiny piece of not even 2000 words this thing is filled with far too many inside jokes of history and stuff#my writing#when you need a break from flat cleaning and battle sorrows and talk to a friend about plants and suddenly this happens#might put up on ao3 too at some point later but noww off to beddd

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ball lightning while visiting a parking lot… Ball lightning is a rare phenomenon described as luminescent, spherical objects that vary from pea-sized to several meters in diameter....

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy little gif cause Tumblr needs some happy Logan too ✨

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I do think the hyperfocus on religious guilt, especially the hyperfocus on religious guilt pertaining to sexual behavior (with one particular romance taking up 90% of the fandom's concern here), is eclipsing the absolutely fascinating canonical relationship Henry has with God.

Henry's guilt, a complicated tangle of survivor's guilt and moral guilt, is never on clearer display than when he dreams of his parents. This dream is the face of how Henry feels about himself and the sins, moral and divine and cultural, he has committed. It always troubles me when I see people yelling at Henry's parents as if they were really there... and not recognizing this is insight directly into how Henry feels about what happened in KCD2.

Notice that he is deeply caught up on theft and revenge/wrath (even when he argues with his father/i.e. himself in his own defense).

Notice, too, that he has no apology to make about Hans (if romanced). Of even greater interest from a character analysis standpoint, neither of his dream-parents (the voice of his internal guilt and misgivings) spare more than a moment's surprise on it. Henry's mother immediately scolds Henry's father when he expresses surprise; down to the marrow of his dreams, Henry does not seem to feel badly, guilty, or conflicted about romancing Hans at all.

Henry's aversion to touching the dead in kcd1 and kcd2 (particularly when someone he deeply cares about does it) is period-place-typical. It is fascinating how he rationalizes with himself in different contexts and how he justifies or does not justify this.

Henry usually gravitates toward social pariahs out of genuine curiosity first, compassion second; I find this point (blended with the above point) especially interesting in the context of his work with Executioner Hermann from KCD1!

Henry's anger is extraordinary, especially in KCD1, and whether or not Henry comes to understand his anger has immense echoes into the "voice" of his guilt.

Henry has a curiously spotty religious knowledge; this always delights me, as he's had a dash of monk's education and grew up in a town without a church. "Crimbo" is a hilarious line, but in other ways, it is also nicely representative of the half-formed grip he has on religious philosophy.

Henry's furious outbursts of "you call yourself a Christian?" are almost exclusively tied to his outbursts in defense of the defenseless, and this is used as a call to moral shame, especially against militant men. I always think first of his genuinely furious attempt to interject when Kuno deliberately uses civilian women as bait in KCD1.

Henry at times seems incredibly confident in his personal relationship with God. I adore the quest A Sinful Soul for how it showcases this. In a direct prayer the player has limited control over, Henry addresses God as informally as one might address a neighbor he has a minor grievance with. He essentially tells God, "Look, I know what you said about this issue, but I also know that YOU know I'm right this time, so I'm gonna do it my way, cause I know you didn't exactly mean it the way you said it there. Thanks in advance - knew you'd agree with me." Henry believes in a God who makes individual exceptions based on what is moral; he also differentiates what is moral from what is godly, and seems certain that God also draws this distinction for Himself.

Fucking thrilling from a character development standpoint! Fucking thrilling in the breath before the Hussite rebellions.

#kingdom come deliverance#henry of skalitz#feeling the missed opportunities comment a lot#not only with this topic but with a lot of details / character traits / motives this story provides us with#also feel like i‘ve grown a little tired of this fandom lately. of the fandom only not of the game that‘s still so very dear to me#it‘s just the way the (tumblr) community has grown from a niche corner where deep character and plot analyses are shared#to a very popular place with a huge influx in content to this space where barely anything that exceeds hansry seems to matter anymore#(or shipping in general. the same fate happened to samuel (and liechtenstein) or individual devil‘s pack members)#with every aspect of their character traits just being squeezed into this shipping lens sometimes with so much force that it removes#so much character depth and all of the aspects that made the relationship dynamic interesting in the first place#sorry. feel like most of the times when i share my thoughts these days it‘s to spread disillusioned fandom negativity :/#and i know it‘s a completely understandable development especially for a story that caught most of its attention here (rightfully) through#their well-represented queer narratives and hansry deserves all the praise and attention in the world#i just wish sometimes that it was less about wanting two people to fuck with personal and anachronistic tropes being moulded onto them#and more about what the characters actually provide because there is so much potential there and i‘d love more people to see and enjoy that#anyway ramble ramble grump grump early morning too-little-sleep fandom depression sorry#everything you say here!#hitting the nail on the head as usual#(is that also a saying in english?)

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

the raid on Skalitz never happened :)

#kingdom come deliverance#theresa#bianca#kcd fanart#<333#do they have a ship name yet?#theranca#biathe#resanca

432 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nostalgia and the Nicer Things ⭐ 'I think today is just a good day' Prints | Ko-fi | Patreon | Bluesky

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

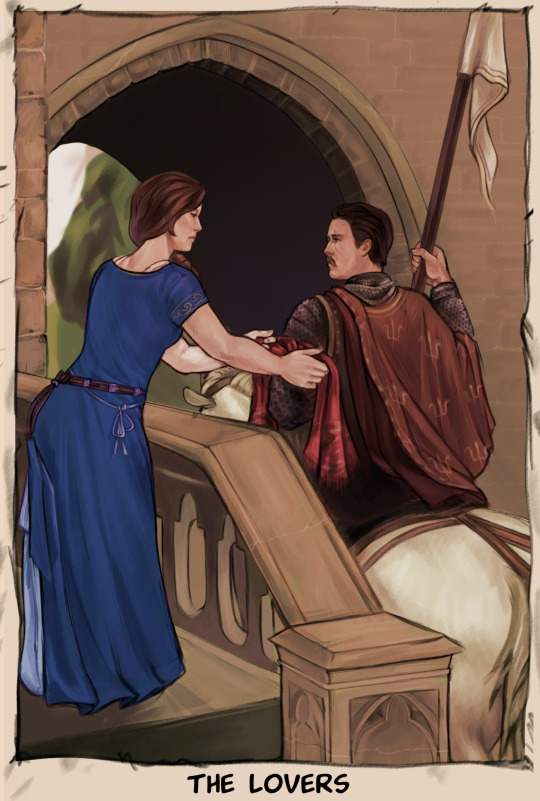

#kingdom come deliverance#katizka#jan zizka#katherine#kcd fanart#having so many thoughts about this but too tired from work to articulate them properly#but still had to share because#love love love#beautiful#parents#yess#moreeee#anywayy

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

This mission looked exactly like that...

#oh. my. god.#SO TRUE#you‘ve created a masterpiece#fave#kingdom come deliverance#i laughed so hard i actually choked not exaggerating

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sed Proditionem || chapter 7

Morituri Te Salutant

Štěpán is given a grand offer. Henry is confronted with his past (anyone surprised?). Žižka is telling a tale of happier times. Samuel is putting his German skills to the test. Then two naked swords are presented (how, indecent!), and war is declared.

{read it below or here on AO3}

(very short) tag list: @shmuel-ben-sarah-kcd2, @bad-system

☆

PREVIEW

The crowd watched his agony with excitement and bated breath. The second man fell down to his knees, covered his eyes with both hands and broke down in tears.

Štěpán took parchment and quill back into his hands, placed it carefully on his knees and began to write. Omnes enim, qui acceperint gladium, gladio peribunt, the one who takes up the sword, will die by the sword. But who helps us decide whether it's the sharp, merciful executioner's sword that a delinquent deserves or the ruthless brutality of a blunt axe?

☆

If it's meant to be then it will be So I met him there and told him I believe.

☆

The smell of a lush green forest paired with that of a freshly cut field and dry hay. Only faintly noticeable, the remnants of thick, suffocating smoke and charred wood and cloth had burned themselves into his nose, into his mind. None of it would matter soon. Soon, everything would reek only of death.

Štěpán put quill and parchment down on the crate next to where he was sitting, folded his hands in his lap and watched. He had managed to claim a good viewing spot for himself, here on a wagon loaded with dried meat and fish. They had a lot of wagons in this camp, so many that Žižka had complained about their inefficiency as they were only making slow progress on their way north, but then again, thirty thousand men needed a lot of supplies. In the few hours that Štěpán had now travelled with King Władysław Jagiełło's and Grand Duke Vytautas's army, they had perhaps advanced four or five miles, if not less than that. Now, with the approaching night, their expedition had stopped altogether, and they had set up their camp in and around a sparsely wooded forest that let up a hill to a clear top, only covered by a meadow and some fields. It was this hill top that the Polish King had chosen for the execution of the punishment. It was here, where hundreds of soldiers and civilian camp followers alike had now gathered to watch. It was almost grotesque, Štěpán thought, how many people had come to witness two men hanging themselves.

One of them had cried and begged when Grand Duke Vytautas had delivered the verdict in his cousin the King's name. Janosh had translated his choking stutters for Štěpán, how the man had pleaded for mercy, because what should his family at home think of him when he didn't return in honour and glory, but rather executed and wrapped in linen? Vytautas had replied that he wouldn't return to them at all. Instead, he would be hanging here until the end of time, the only question was how well he built his own gallows and whether his body would become a feast for the crows or for the wolves.

The other man, the one with a bald spot on the back of his head in the form of a heart, had not shed a single tear. He had cursed. At the King and the Grand Duke, and at God, so much Štěpán could understand. Janosh had refused to translate the rest for him.

Štěpán craned his neck to peer across the masses of heads that were all turned towards the platform where the two men were hammering the last nails into their own coffin, but the braided black hair and the green kaftan were nowhere to be found. Disappointing, but not surprising. Janosh seemed to be busy here in this camp, and his busy path lead surprisingly often to the King's tent. He had so far not given Štěpán any good explanation for why that was the case, but it wasn't like this one day of travelling together had offered them much time for talking. Štěpán would have to ask him later, and then he would not let Janosh go before he gave him a satisfying answer.

The crowd fell suspiciously silent, and Štěpán looked back over to the platform. The balding man was tying the last knot into the noose, then he looked up to the sky that was painted the same colour as the fire he had caused. The other man froze, watching in horror as his comrade placed a stool under the crossbeam and stepped up to throw the end of the rope over it so he could tie that too. Then he took a deep breath and turned to the masses. With a bellowing voice he shot another salve of curses across the hill, ending it all by putting his right fist to his heart before he finally grabbed the noose and hung it around his neck. Then he kicked the stool underneath his feet. It fell, but did not slide away as he had intended, and so he only fell down a few finger's breadths until his fall was stopped by the legs of the toppled stool. Not nearly enough to break his spine. His eyes got wide, his face took the colour of poppies, then of violets, he choked and gurgled and thrashed around with every limb of his body, and then he did scream and cry, but his voice was not as strong now as it had been before, only a broken, feeble breeze.

The crowd watched his agony with excitement and bated breath. The second man fell down to his knees, covered his eyes with both hands and broke down in tears.

Štěpán took parchment and quill back into his hands, placed it carefully on his knees and began to write. Omnes enim, qui acceperint gladium, gladio peribunt, the one who takes up the sword, will die by the sword. But who helps us decide whether it's the sharp, merciful executioner's sword that a delinquent deserves or the ruthless brutality of a blunt axe?

“What do you think of this punishment?”

Štěpán lifted his eyes from his own words, and saw Žižka standing next to him. He had taken off his shining plate armour and the white coat, was only wearing a simple tunic and a short-sleeved padded jacket now, with a cap on his dark, combed back hair that looked as if he wanted to go hunting. His expression did not show any strong emotion, neither shock nor satisfaction, but the one eyebrow that still responded to his facial muscles was raised expectantly.

“I think it's cruel,” Štěpán replied honestly.

“Hm,” Žižka made, and it was no confirmation but no objection either. “Do you think it's fair?”

He looked back to the man hanging from his noose. His body was still twitching, but Štěpán believed, hoped that he was at least not conscious anymore. Fair. The law was fair, and if it was supposed to stay that way, then there was no room for thinking in it. Thinking only bore personal sentiments, and those would always cloud better judgement. Laws and and the established consequences of breaking them on the other hand were set in stone, for everyone to read and act accordingly, and that was what made them fair. But even a tablet of stone would not last forever. “I know that it was necessary,” Štěpán answered, because that at least he was certain of.

“So you understand the reason why Jagiełło had to do it?”

“They violated and murdered good people. Civilians. That is a war crime.”

“What else?”

Štěpán kept silent for a moment, watched as the hanged man's body finally fell still. His eyes were open, they looked blood-red from the distance, or perhaps it was only the reflection of the evening sky. “They burned a church. I heard that they also desecrated the host. King Jagiełło wants to be seen as a faithful Christian. It's how he justifies his campaign against the Teutonic Order, by proving that there is no reason for any further crusades.”

“Good.” Žižka sounded proud, almost paternal, and Štěpán realised that he had never before heard anyone talk this way to him. The tone was dangerous, because it made him long for more, and because he knew that it was a fallacious longing that could not be satisfied, as deep below the apparent pride resentment was hiding. “Anything else?”

Štěpán did not care for the fallacy. He wanted to hear that voice again. He couldn't. The man was swinging left to right with his red eyes wide open, the other convict tried to stand up again, but his legs were so weak that they gave in underneath him and he fell back to his knees. The crowd's suspense had been broken, they were screaming at him now, insulting him in Polish and Lithuanian and Ruthenian, Czech and Tatar, urging him to finally face his deserved fate and take his own life.

“What did these men do?” Žižka continued, still sounding like a father who was guiding him kindly, and it bathed the grim scene in front of him in a much more bearable light. “What did they do to the church, to the houses and crops, what does that mean for us, for this expedition?”

“They burned it.” Štěpán almost snapped the quill in two as he realised. Reddened, dead eyes, clouds moving fast across the sky, mirroring the sun's flames and the darkness of the night. “Fire. They set it on fire. Which caused pillars of smoke to rise up that were likely visible from many miles away.” He turned back to Žižka. Somewhere in his one steel-blue eye and below all the hair of his moustache, a fond expression was hiding. “Do you think they've seen it? Do you think the Order is already on our tails?”

“My guess is that we'll know once we get to the Drewenz River.”

“You're expecting them to wait for us there.”

Žižka crossed his arms, and the short jacket made them look twice as big as they normally did. The mind of a strategist, the body of a warrior. Far away from what Štěpán was, but maybe in a few years, when he had spent more time with Žižka and his band, who knew how things were then. Given they even made it this long, that was. “Jagiełło is still in good spirits. We haven't heard anything of the Order on our whole way, and he believes that it's a good sign. I believe an enemy lying in silence is far more dangerous than one who screams at you from afar. But we'll see.”

“It's said that the Order has heavy artillery. If they saw the fires and know our path, they might already be waiting somewhere near an open field that we'll have to cross, lying in ambush and waiting to shoot us down once we get there.”

Now, Žižka did smile. It was visible in the wrinkles next to his eyes, and from the way his teeth bared. “You spent too much time with Kubyenka and Janosh, boy. It made you start to think like a bandit. No. if there is one thing we can rely on about the Order, it is their knightly honour. They will want to face us in a proper battle. Defeat us by demonstrating that they truly are the best skilled warriors in Christendom.”

The best skilled warriors in Christendom. A phrase that had been thrown around the camp the whole day, sometimes whispered as a warning, sometimes spoken in taunt, as if it was only a mocking name that bore no resemblance to reality, but everyone could see through the mask of fear that painted the jest a lie. It was an entirely different thing to hear it from Žižka's lips now. Not as a jest, and not in fear either, only as a blunt matter of fact. “So do we even have a chance?”

“The odds could definitely be worse. Even with Sigismund's and Wenceslas's support, it will be hard for the Germans to gather enough soldiers to meet the size of our force. But I'd assume that they are better equipped than us. And they are definitely more disciplined.” His eye wandered to the platform, where the second man had finally finished his gallows too, and was now trying to attach his own noose to the beam. His hands were shaking so much that the rope slid down again and again. The crowd became impatient. “You forgot one reason, boy, why Jagiełło had to do it. Disobedience. There is no room for disobedience in a battle like this.”

“Are you mad at us?” He wrapped the words into a question, but it was needless, Štěpán could hear the reproach in his voice, and it wasn't directed at the two plunderers. Žižka did not reply. Just as needless, he could not have given Štěpán more confirmation than that. “I thought you wanted us to come. It was you who asked us for it in Prague.”

“But not under these circumstances. With Capon being here in disguise as some nameless, itinerant knight, and you, you have run away from your guardian like a thief.”

“I'm old enough to decide over my whereabouts for myself.”

“We both know that's not how it works. You're still a vassal in Dubá's service. If you're lucky he'll only have you whipped for disobedience, if he decides to show more strictness, he might as well have your ears cut off for deserting.”

“I'm his assistant, Žižka, not his soldier.”

“And yet you ran. Even though you knew that Dubá relies on you, that he needs you to help him with the work he cannot tend to on his own anymore, now that he is old. You studied the law just for that cause.”

Štěpán pouted. It wasn't like he hadn't thought about all this before, how Sir Ondřej would fare now that Štěpán hadn't even left him a message about where he went, and what happened to the old Lord in case Štěpán wouldn't return. He really didn't need Žižka to make him feel bad about it too, but perhaps that was just one of the downsides that came with his paternal tone. Or it was simply the commander in him spurring him on. How many ears must he have cut off when one of his band had not followed his orders? Had that been why Kubyenka had threatened to do the same to him back in the gorge? How many times had he witnessed Žižka doing it to one of their men? Štěpán put the quill down and wrapped his arms around his body. The corners of his mouth dropped even further. “So what? Sir Ondřej will find someone else who can study the law. I'm just a tool to him, I'm not indispensable.”

“That is not relevant here, boy. You disobeyed him. I need you to understand what such disobedience can lead to under different circumstances.”

Štěpán looked up to the gallows on the platform, with the two dead men underneath of whom one was still breathing. He had finally managed to tie the noose to the beam and had draped it around his neck, but he hadn't jumped yet. He might not have to, his legs were trembling so severely, Štěpán was certain they would just give in on themselves any moment now. On the trees of the nearby woods, the crows were inviting him to feed them faster.

“You won't engage in the battle.”

Štěpán spun around so quickly, the parchment almost slipped off his lap. “What?”

“You will stay at camp.”

“At camp? Together with the women and children and the cooks and sutlers?”

“Together with all the other folks who are not fit for battle, yes. Now, do not open your mouth and your eyes so far, it makes you look like a fish. What did you expect, boy? You have barely any military training, we'll have no use for you on the battlefield.”

This was atrocious! The long ride for over a week, sharing a single room with the other five in some reeking tavern on the side of the road, the jump from the Zlenice castle wall, nearly breaking his ribs, leaving Šárka behind. All for nothing? If this was the retribution for his disobedience, Žižka might as well have asked him to hang himself in front of everyone too, it would have been much less cruel of a punishment. “I did not come all this way to be shoved to the sidelines! Let me at least wait somewhere where I can watch the action, I do not have to participate in it!”

Žižka's right eye and the rest of his face had become just as cold and motionless as the blind left one. “I say it one more time, and it will be that last time, Štěpán. I do not have any use for you there.”

“But I might have use for him.”

Štěpán turned to look for the source of the deep, but youthful voice that had uttered these words in broken Czech. The man had stopped a few steps away from them, near a wagon of dried fruit. He was dressed noble and way too warm for the temperature that was still as burning as a hearth, despite the approaching night. A black cap of velvet, crowned with golden thread and a smoke coloured gemstone brooch in the middle. Velvet on his coat too, trimmed with silver depictions of vines and in between them eagles with spread wings. A man of the Polish King then. Štěpán was sure he had seen him at Jagiełło's side before. A young, proud face, he could not be much older than Štěpán was, bright eyes that looked down on him, despite Štěpán's raised position, from the way the man had his chin tilted up, a smug smile tugging on the left corner of his lip.

“Oleśnicki,” Žižka greeted the man, but he did not bow, nor did his voice show any kindness.

The fish face returned to Štěpán's expression, and he could not have cared less. Oleśnicki. Zbigniew Oleśnicki, the King's very own secretary. He slid off his crest, landed on his feet a bit roughly, stumbled, noticed how parchment and quill had fallen down to the ground. “Sir, I … I'm honoured, by your presence, Sir.” He bowed down in a hurried greeting, and to pick his equipment back up, making it look as if he wanted to kiss the secretary's feet, and he felt ashamed over it immediately, his cheeks blushing. “And I'm also honoured that you would … Wait, what did you say?”

Zbigniew Oleśnicki's knowing grin grew even further. “I'm assuming you heard correctly, young Lord of Tetín. I, and that is also to say, the King of Poland, Władysław, second of his name, Jagiełło, have a special task for you.”

Štěpán felt as dizzy as after his fall with the birch tree. Žižka did not share his excitement. “For him? The King has assigned a task to the ward of some Bohemian nobleman?”

“Not any nobleman, if I am correctly informed.” Zbigniew Oleśnicki turned his head to Žižka, but he did not lower it the slightest, and his smile became cold. Žižka looked like he would have loved to punch his face in, and Štěpán decided to ignore that too. “Lord Ondřej of Dubá and Zlenice is one of King Wenceslas's highest judges, is he not? And I have heard that Lord Dubá has thoroughly instructed his ward in all aspects of the law.”

Štěpán grinned proudly, bowed his head and felt his ears glow with pride. “That is correct, Sir.”

“Furthermore, the young Lord of Tetín has proven his worth only this morning when he courageously rushed in to stop these two criminals and their horde from causing any more carnage. Oh.” A scream interrupted his words, but it quickly died off as the noose closed around the man's neck. He was luckier than the first one. The fall had broken his spine at once. “A pity. You would not know it from his cries and screams, but he had quite the singing voice. It was a nice distraction on our way here.”

“You still have not explained yourself yet, Oleśnicki.”

The King's secretary glared down at Žižka, and his eyes looked almost as pale and cold as those of Petr of Haugwitz. Erik, Štěpán reminded himself. Erik of Lies. “I believe I have explained myself very well.”

“You said that Štěpán is educated and has proven his worth to our cause. The same thing can be said about a hundred other men here. Could be said about deputy chancellor Mikołaj Trąba for example. Could be said about you.”

“Yes, but I am not suited for this role, as I will have to guard the King during battle and cannot be distracted by anything else. And the chancellor has already refused.”

“So you're asking him,” Žižka said, and Štěpán felt his fists clench with anger over how Žižka talked about and for him. The quill snapped, the pieces fell to the ground. He bent down once more to collect them, and felt the two men's disparaging looks weigh down on him. “The seventh son of some Czech family who came to serve under Sokol's mercenary banner. Who is here without his guardian's leave, meaning that his name will not be mentioned anywhere and that he will clearly not be missed.”

The secretary laughed drily. “You make it sound as if I wanted to send him to the vanguard, Jan, as cannon fodder to those German bastards. It is an honourable task.”

“I want to hear it,” Štěpán finally interrupted their quarrel. “And as the one being offered the task, I will be the one to decide.”

Žižka took a deep sigh, shook his head, but then stepped back with an inviting gesture forward that screamed It's your grave to dig. Behind him, the two men were swinging almost peacefully from their gallows. The crowd had already cleared to a large extent, a dead man did not seem to be nearly as exciting to watch as one fighting with death and losing.

The satisfied grin returned to Zbigniew Oleśnicki's face, and Štěpán could sense that it had more to do with Žižka being put in his place than with Štěpán's agreement. “The offer that I want to make you, young Lord, is to write history for us. Quite literally, that is.”

“You … You want me to write the chronic. Over the events of the battle.”

“See? I knew you were smart enough for this work.”

“Well, I, thank you for the offer, Sir, I …”

“And where would he be,” Žižka interrupted his stammering, “during the fighting?”

“With the King, of course.”

Štěpán's face got so hot, he was certain it would soon have to melt away. By the King's side, with the war raging around him. Listening to the King's orders, taking notes of them.

“On the battlefield.”

“At the rear end of it, yes. He would have to be there, to witness everything and write it down.”

“It would be an honour,” Štěpán hurried to say, before Žižka could utter any more objections. “A great honour, thank you, Sir, I will be glad to do it, and I will not fail you or the King.”

Zbigniew Oleśnicki smiled contentedly, and then he grinned even wider when he turned to Žižka to bid him farewell with a bow. Žižka did not return the gesture.

“This is a good thing for me, Žižka,” Štěpán finally said when the secretary had left them. Most of the crowd had disappeared too and had gone to prepare everything for the night. Somewhere in the shadows of the forest, a single man was sitting on a tree stump, watching over the two corpses like the crows in the leaves above him. A stern, but noble face, long, straight hair falling on his back, and the hat he held in his hands looked like it was of the red velvet the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas's crown was made of, but it was hard to tell from the distance.

“Even more than that,” Žižka said, taking no notice of the man, “it is a good thing for Oleśnicki. Guard the King, eh? I'm sure that sly eel is already praying for a chance to save Jagiełło's life, so he can crawl up his arse even further.”

“So what? Then we're killing two birds with one stone. You said it yourself, I'm not a fighter, but I know about the theories of war, and how to write them down. Christ, I've been doing the writing all this time!” He waved the broken pieces of the quill around and tried not to think about the sad impression it must make. “This was made for me. And I don't care whether he's only using me. Or whether he hopes to erase my name, and put his own one down on the chronic afterwards. It's still a chance for me to prove myself the way I know.”

Žižka took a deep sigh, rubbing the back of his hunter's cap. But then his face finally smoothed, and he took the cap off, and as he reached forward to place it on top of Štěpán's head, his full moustache was lifting under a smile. “Well, then I suppose I owe you my congratulations. Just be careful, alright? That's all I'm asking of you, son.”

Son. Štěpán chuckled softly over the word, his chest felt as full as if he had breathed in all the air of the hilltop, swollen with happiness and pride. Under the shadows of the trees, the man raised his head and, as if he had given a silent command in a language only he understood, the first crows rose up from the branches, rushing in with eager screams to devour their feast.

* * *

It started raining as they were nearing Kauernick at the Drewenz River crossing, and the cooling rain lifted everybody's mood immediately. The air started smelling beguilingly of damp grass and soaked earth, the birds started singing again, as they had no reason to hide any longer, and it was only with great effort that Henry could resist the urge to whistle along with them. He stood up in his stirrups, let his gaze wander over the rolling meadows surrounding them, seemingly stretching out to the end of the world, and over the mile long retinue of riders and foot soldiers and camp followers and hundreds and hundreds of wagons, roaring louder than the bells of Saint Peter and Paul on the Vyšehrad would on a Sunday. It was not all that long ago, Henry thought, that he had visited his father there for the first time. Telling him about their failed plan in the gorge, asking burgrave Radzig Kobyla which route he should follow, that of his fate or his heart. Whatever path calls out for you, his father had said, I want you to know that there will be at least someone else walking it with you. He had been talking about himself that day, and Henry had been convinced he might as well have left the at least out completely, because who else would be there to have his back in every twist and turn he walked on? How lonely he had felt back then, how blinded he had been by the rut of his life and by frustration over his own actions, and it had robbed him of his ability to see. He had a family beyond his father. A brother who had not even blinked an eye when Henry had asked him to come. Friends he would die for and who would die for him. And Hans.

Kurva, Henry thought, shifting around in his saddle. The scar on his hip got more and more uncomfortable. And his arse hurt. An adventure like this was all well and good, until one realised that it involved days and weeks of riding without end.

“Strange, isn't it?” Hans said next to him with glee in his voice, because either his saddle was softer than Henry's, or his arse was, or he was simply too delighted to take notice of it. Which might just have been the case. Hans was grinning so widely, Henry wouldn't have been surprised if he just stretched out his arms like wings any moment now, as if they were twenty again. “How well we have advanced so far! As if Lautenburg was the only place where the Order had stationed any of their men.”

“Žižka believes it might be some kind of ruse.”

“Yes, because he is the king of ruses, but that does not mean that everybody is constantly rusing everybody else.”

“It's plausible though. When we got here yesterday morning, we had no problem to find and follow the route of the expedition until we caught up with them. Why should the Teutonic knights miss it? All this chaos and the fires.”

Hans shook his head, rolled his eyes. “Because they are kept busy in Schwetz.”

“Nah. They must have smelled the rat by now.”

“Oh, cheer up, Henry!” He let go off the reins to give the rear of Henry's thigh a slap with the back of his hand, and they were truly riding for too long now, because his skin felt sore there too, and Henry pressed his teeth together and shifted his weight once more. “Why don't you want to believe that just this once luck is on our side? You know how it is, fortune favours the brave!”

“And that's us? The brave?”

“Of course it's us! We're quite brave, I'd say.” Hans turned his face to him, and it was a beautiful sight, the soft raining moulding his golden hair into locks, dampening his brows and lashes and beard, like dew sticking to blades of grass in the morning. Hans laughed. It was honest, and it made Henry smile back in return, even when he did not feel like it. “God knows you're one of the bravest men I know, Henry.”

“Oh, I don't know about that. At least I wasn't the one who left so much behind for this journey. You left Rattay for this. You gave up your name and took on this travelling knight persona.” He swallowed down a lump in his throat that came with the realisation. “If you die, your body will be buried with all the rest, without any headstone to recognise and remember you by. I think you're much braver than me.”

Hans shook his head, laughed up to the clouded sky. “Christ's wounds, Henry, you really know how to brighten every mood!”

Henry rode his horse closer to him, so close that, when he reached out his hand, he could grasp the reins together with Hans. Rough skin on light leader gloves. A promise, and Henry realised with pride that he could give it, because now he actually meant it. “I won't let that happen. If someone wants to strike you down, they will have to get past me first.”

“And the same thing goes for you. Whatever happens, I will protect you with my life, Henry.” Hans put his left hand down on Henry's, held him tight. A promise too, but also an apology. Stop it, Henry wanted to say, there is nothing you have to feel sorry for, but he kept it to himself, did not want to interrupt Hans, not in such a moment of honesty that they hadn't shared for what felt like an eternity. “To the others here I'm only Sir Ignatius of the Cornflower, but you and me, we both know who I truly am. The Lord of Rattay who has sworn to keep his vassals safe. And more importantly than that, I have sworn an oath to you specifically. That I would always be by your side, no matter where life leads us. Now, I …” He cleared his throat. Somewhere ahead, a quiet turmoil passed through the front half of their expedition as they entered yet another dense forest. Henry furrowed his brow, tried to remember, but he couldn't. “I know I have not always succeeded at that,” Hans continued with sincerity and shame. “And I … I think I can understand why you had to leave to Prague for a while. I've tried my best to be a lord and a father, and in doing so, I may sometimes have failed to be a lover, and even more so, a friend. But my oath still stands, Henry, and I will do everything in my power to live up to it going forward.”

Henry shook his head, not over the words that had moved him to his core, but because he really could not make any sense of it, and then he leaned over to Hans and whispered with the greatest frankness: “Look, that's very sweet and all, but what oath are you bloody talking about?”

Hans let go off his hand and spun around to him in his saddle, as if he had never heard a more crushing insult. “The oath I spoke to you on my wedding of course.”

“What?”

“After the celebrations. Down by the water, uhm …” He shook his head and his gaze wandered off into the distance as he tried to recall the events, because apparently he could not remember shit either, so was he fucking making this up? “Žižka was there too! It was just before Godwin joined us, I think, all naked on that horse. I tied a ribbon around your wrist.”

“A ribbon?”

“Henry!”

“I'm sorry.” He had to laugh over Hans's outrage that was just too ridiculous, especially considering that he did not seem to know what he was talking about all too well either. “I'm afraid I do not remember much from that night.”

“Well, neither do I, but that moment was special to me.”

“And I'm certain it was special to me too, back then.”

“Clearly.” Hans averted his gaze and pouted, and it was so childish that Henry's laugh grew into a full heartfelt bark. “It was so special to you, in fact, that you just forgot all about it.”

“Yeah, like I forgot about everything else. What do you mean, Godwin got naked on a horse?”

Now Hans had to laugh too, raising both his eyebrows at Henry. “God help me, Henry, you must have been more wasted than I was, when you even forgot about …” His words died off, the smile vanished. He stood up as far as he could, but all that was visible in front of them was the darkness of the woods, the path twisting and turning so wildly between bushes and creeks, that one could barely make out another dozen rows of their army. But the rest of them they could hear. Their shouts and the neighing of their horses as reins were pulled, and they felt the tension as clearly as the coldness of shadow and rain. “What's going on?”

“Halt!” someone screamed, out of sight from Henry's position. The horses stopped, as if they had run into an invisible wall. Hans's chestnut gelding pranced back and forth and snorted in protest from how hard he had to pull the reins. The riders in front of them whispered to each other as if the Messiah himself had appeared. Or the Devil. It was hard to tell.

“Stay here,” Henry said, then he already guided his horse into the undergrowth to make his way past the others. Slowly over the forest's earth that the rain had turned into mud. Listening to the whispering of the other Bohemian mercenaries who seemed to be just as clueless as he was, and then to the talk of the Polish troops that rode before them, of which Henry could only understand little. He did not have to. The tone of their voices and the panic on their faces was enough to realise that it was indeed the Devil they had encountered.

Thorny blueberry bushes and fern and moss, then some Polish riders with a roaring, yellow lion on their sky-blue shields had to move aside so that Henry could bypass a channel of rainwater. One of them cursed in Polish, the other one knew better and insulted him in broken Czech. “Eh, what are you doing, you fool, stay in line!”

“I need to get to Žižka,” Henry retorted like it was a plausible excuse.

It was not. The lion Pole only rolled his eyes at him. “Right, like we all don't need to get to someone. Why don't we just all storm forward and trample each other down, eh?”

Henry cursed, first internally, then a little stronger externally, before he spurred his horse on again. More blueberry bushes, more fern, then the ground turned from mud into sand and stone as the forest got lighter. He had moved past two or three Polish banners, had got to a point in their group where more crests of Saint George were visible, and much further ahead still, the three goat heads around a ring of Jan Sokol of Lamberg's crest. Behind his banner, the forest cleared for a wide riverbed, the Drewenz. And right next to where the bridge had to be, the wooden walls of the Kauernick castle rose up. Above it, thick clouds darkened the sky on one side, while on the other, the sun had forced her way back out of her hiding. Somewhere behind the trees, Henry thought, there had to be a pretty rainbow. He did not get to waste any more mind on it, because when he once more looked at the castle that lay half in shadows, half in bright sunlight, he realised that it wasn't a castle at all. The construction had towers and walls, but they were entirely made of wooden planks, not of stone, and with larger empty spaces in between, making it look like the structure was entirely built of balustrades, instead of solid walls. On its multiple storeys, men were standing, draped in white cloaks, icicles growing out of the wooden platforms like stalagmites, and on the highest points of each tower, banners were flapping in the wind. Black crosses on white fields.

Audentis fortuna kiss my arse.

“Henry!”

He turned left and saw Katherine waving at him from between the group of riders. Kubyenka was by her side, and his face was rutted by wrinkles of confusion that were as deep as the Rattay castle moat.

“Hey!” Henry greeted, trying his best to bring his horse back in line to meet up with them. “What is going on there?”

“How the hell should we know?” Kubyenka just retorted without taking his eyes off the wooden building at the end of their road. “Ask the captain.”

“I'd love to.” He looked to the front again, to Jan Sokol's banner raised high above the heads of at least a hundred more riders and almost just as many wagons, some of them placed so closely next to each other that not even the Tatar Golden Horde in full speed could have rushed through them. Impossible. Then he looked back over his shoulder to where the winding path disappeared between massive beech trees and even more massive pines, and the road was crowded now like the Prague streets on a market day, because everyone was curious, everyone wanted to see and know more, and somewhere far, far down the trail between the closely huddled masses, Hans was still waiting for him, and Henry cursed again and even more profoundly than before, making the sign of the cross just in case.

An hour or so later, the whole expedition had left the forest and set up their camp near the Drewenz River, opposite the wooden construction of the Teutonic knights. Which had turned out to be something not all that unlike a castle, namely the Order's sentry fortification of the river crossing. And a fucking huge one at that. Immediately after giving the command to wait and settle south of the river, King Jagiełło had sent two heralds over to the fortification, both to scout and to talk. The talking had not proven particularly successful. There was no room for negotiating, no bargaining to be had. They had not erected their defence for the past week for nothing, the Teutonic knights had declared. Their goal was clear, their Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen had given the order himself. Not a single Polish or Lithuanian soul, or a Bohemian or a Tatar one for that matter or one of whatever hole they had crawled out of, was to set foot north of the river. And if they did anyway, they would get shot down with hand cannons and bombards within seconds.

“They believe such a threat can stop us,” Kubyenka had said to Henry as the heralds had brought back the Order's drastic declarations. “This Ulrich fella must think that because we're such a weird bunch of a troop and follow two cousins who were stuck in their own family quarrel not too long ago, we'd be easy opponents to them. Ha. He surely never made the acquaintance of the devil's pack before.”

Henry wasn't quite sure whether the pack could truly serve as a good example for a mismatched team in light of their most recent successes, but he kept that thought to himself.

Now, they were waiting. Right in front of King Jagiełło's big tent of red and white cloth with embroidered eagles, in which he usually brought his council together. Or the important people, as Henry liked to call them. Žižka was part of those important people. Since the last evening, some time after the self-execution of the two string-pullers of the Lautenburg plundering, Štěpán was part of them as well. And for some unexplainable reason, whenever the council got together, Henry had also noticed Janosh to mysteriously disappear. “Perhaps Jagiełło is an enjoyer of good food,” Hans had said when Henry had asked him about it. Sam, who had been riding close by, had raised his brows at him, but kept his mouth shut.

Both Hans and Sam had retreated to their own tent that they shared with the rest of the pack, and Mirtl and Kubyenka had come with them. They could spend the waiting more sensible, Kubyenka had suggested, such as by filling their stomachs. “What about you, woman?” He had looked at Mirtl with these words. “I'm sure you can make us something nice.” Hans and Sam had screamed their cautionary “No!” in perfect unison.

“Well, at least they have not attacked us yet.” Kat crossed her feet, her arms were crossed already, twinen herself into a double-twisted pretzel. “They have full control over the bridge and the Kauernik castle, they could have easily come at us by now.”

“A bridge is not a good ground to fight on,” Godwin objected, but his eyes were clouded by wariness when he moved them over to where the fortification and its menacing cross banner towered over the hundreds of roofs of tents.

“But they had the moment of surprise on their side. They said it themselves, they had waited for over a week, while we hadn't even expected them.”

“Especially not so many.”

“What do you think,” Henry asked hesitantly, feeling the weight of heavy lead on his heart press down even further, “what's the size of their army?”

Godwin shook his head. He had taken off his cap, to knead it between his hands, and sweat pearled on his naked scalp. His eyes avoided Henry's as good as they could, and at first, Henry believed he wouldn't answer at all, caught between wanting to give them the honesty they deserved and not wanting to crush their morale, but then he took a deep sigh. “From the looks of it and judging by what the two lads reported back, their army must come close to the size of ours. A few banners less perhaps, but they have a large amount of artillery on their side.”

Henry nodded and looked back up to the nearest tower. At least a dozen men were waiting up there in the heat of noon, only small spots of white, like the bird shit on the Karolinum's roof, but even from this distance, Henry recognised the cannons they held in their hands. Pointed at the Polish-Lithuanian troops that had gathered right in front of them like pigs for slaughter. And he knew that they had proper bombards too, their own little Fingers of God. Perhaps that was the gift one was granted for carrying God's cross out into the world. But then again, right after their stay in Trautenau, when they had just rode up the first slopes of the Giant Mountains, Godwin had told them of the other reason why he had agreed to come with them, next to saving his friends' arses, that was. The Teutonic knights were liars, he had told them, hypocrites. Claiming to spread the Christian belief only to justify their hunger for territorial gains and power. Tearing down everything in their way that was not following God's will yet, all while not following it themselves, but rather a flawed interpretation of their faith that was only interested in wealth and ostentation and violence. And those weren't even his own words, Godwin had explained, but those of Master Jan Hus himself, and if anyone would know it was him.

Right?

On that morning, at the foot of the Giant Mountains, it had all made sense to Henry. Now, a week later, staring up to the knights in their white armour, glowing in the sun like angels sent down to deliver divine punishment, he wasn't so sure anymore. Or perhaps, all of these thoughts were presumptuous, or nothing of this had anything to do with God at all, but rather with Hans and his continuous invocation of fortuna, and the dung pile of bad luck that he must have shovelled onto himself with it by now.

“And yet,” Kat began, and Henry was thankful she interrupted his circulating, gloomy thoughts, “they haven't released a single shot yet, even when they could have easily done so.”

“I don't think they're interested in a proper battle, not yet,” Henry replied. “Perhaps they are even hoping that this fortification of theirs will be enough to serve as a warning that will scare us off before any fighting can even take place.”

“Their Grand Master might hope so,” Godwin pondered with a shake of his head, shattering Henry's naïve wishful thinking to pieces. “But the rest of his men? I doubt it. Jagiełło and Vytautas have advanced so far, they won't just return now, and neither does the Order want us to. The war has already been started, the men are hungry for blood, theirs just as much as ours.”

“But we cannot go any further either,” Henry said, crossing his arms in front of his chest, wool and leather clinging to the skin of his shoulders, wetted from both rain and sweat. “We won't be crossing the Drewenz, that they have made sure.”

There was worry on Kat's face as she looked up at him, and fear. The work of setting up camp had messed up her hair, one strand had come loose, stuck to her full cheek, still wet and glistening in the light of the resurfaced sun like a cobweb. “So what, will the battle be fought here, right by the river?”

“I hope not. I still haven't learned how to swim.”

“Believe me, son,” Godwin laughed bitterly, “no man can swim in heavy armour. And you don't want to witness the horror of a whole troop drowning as they slowly feel their own boots and platelegs run full of water, dragging them down to their grave.”

“You talk like you've seen it before.”

Godwin's eyes were fixed on him, but his gaze was somewhere far away, lost in the past, and then he lifted his head and looked up to the crow sitting on the pole of the red eagle banner and to the dark storm clouds in the distance. “I've seen enough.”

They stood in silence for a while. Listening to the sounds of thousands of soldiers talking, and letting their armour clatter as they kept themselves busy with battle practice, or the metal pots and wooden bowls of those who tried to distract themselves with cooking and eating. They listened to their own thoughts too, and somehow those managed to be even louder than the camp around them, because the tense silence was felt by all of them, and no songs were sung and no laughter shared.

Henry clasped his shoulders tighter and thought of the past week, of Hans, of the warmth of his back pressed to his chest at night, the smell of his hair that was so uniquely Hans, sweet like violets and wooden and fresh like a forest, and Christ, how long he had believed to never feel this close to him again, and then Henry raised his eyes and saw two soldiers walking past them, a taller one with a long face like a horse and a shorter one whose head was covered by a black scarf he had wrapped around himself as protection from the sun. And suddenly he heard his voice.

You will die here, István said. He will die here. He will fight like the brave, chivalrous noble that he is, until someone pushes him off the bridge like a coward. And you will watch him sink, unable to save him. Until the only thing left is that ugly shield with that flower that you made for him yourself, floating on the surface of the river, and then even that will be washed away. And he will be buried in some mass grave on unconsecrated ground to rot in Hell like I do. And no one will return home to tell the tale. The man with the black scarf turned his head. His round face, his curved, thin lips, his light brown, taunting eyes. All because you could not be satisfied with the life you had, he said, and then his lips twisted into a wicked smile. Always restless, always striving, always hungry. How well I raised you, boy.

The cover of the tent was pushed open, and Henry jumped at the sudden sound and movement. The man with the scarf narrowed his eyes in confusion. Blue as the summer's sky, and his lips were fuller too, his chin more angular, his cheeks hollow. Henry turned his back to him.

About two dozen men left the King's tent, all in silence and discontent, while many more remained inside, not looking any happier. Henry could catch a quick glimpse at the lowered, darkened faces of those sitting around a large, round table, lit up by a few candles placed between them. Of the Polish King he could only see the golden spikes of his crown, while his cousin, the Lithuanian Grand Duke, was standing at the far end of the tent, wrapped in darkness like into a cloak. Opposite the King, was Štěpán, almost lying across half the table as he apparently tried to bring the parchment he was writing on as close to the dim candlelight as possible. His bent body obstructed the view on most of the people next to him, but the black hair and the green embroidered kaftan of the one sitting by his side was still unmistakable.

Žižka left the tent as one of the last, then he waited for the two men coming after him, before he closed the cover for good. His shoulders lifted and fell under a deep sigh, and when he turned, he looked as exhausted as if he had just spent a whole day listening to the Prague archbishop preach. Judging by his hardened expression, the council meeting seemed to have proven just as little insightful.

“So?” Godwin asked.

Žižka shrugged. “Many ideas have been posed. Jagiełło has listened them all and will now have to consider them.”

“So he has not made a decision yet?”

Žižka shook his head.

“How long will it take?”

“With so many people and languages and experiences and expectations?” Žižka laughed the bitter laugh of someone who was on the brink to losing his rag. The wrinkles on Kat's face grew even deeper. “Who knows. Might be weeks.”

“But we don't have that long,” Henry burst out.

Žižka looked at him like one would look at a gullible child, and Henry certainly felt like one too. “I know that. And Jagiełło knows it too. I'm sure he has realised by now that his council of primoribus consiliariis, as the smart people in there like to call it, is not as fruitful as he hoped. He will have to narrow the number of counsellors down if he hopes to make a proper decision.”

Henry nodded, because it made sense. Too many cooks spoiled the broth, he had learned that many years ago, when he had once helped Matthias steal Beran's dice, as retribution for a trick the old turner had played on him, and it had taken them a whole night of plotting and drinking and arguing, until Fritz and Henry had decided to figure out a plan on their own. At the start of the next day, the dice had been theirs. Acquired rather dishonourably, but perhaps the ends truly justified the means.

He looked past Žižka to the closed tent, tried to listen for the talk inside, but either the tent's walls were too thick or they had not picked up their conversation yet and were still sitting in uncertainty and gloom. “What about Janosh? Will he be part of that smaller council?”

“Janosh? I doubt it. But he will be part of the decision making.” Žižka seemed to notice the baffled look Henry gave him, because he laughed and placed a strong hand on his shoulder. “There are a lot of things between Heaven and Hell that you do not and will not understand, lad.”

“But let us at least understand one thing, Žižka,” Godwin interrupted before Henry could ask any of the questions that were burning on his tongue. “What are our options? Clearly, we won't be storming Kauernik anymore as we had intended to.”

“No, that one is out of the question. Vytautas insists on fighting here and now, but Jagiełło won't agree to that, he's way more level-headed than his cousin. Come on, let us walk back to our tent, all the talking has made me thirsty.” He set himself into motion, and Henry, Godwin and Kat followed him like sheep running after their shepherd. “The solution that I consider the most sensible would be to find another river crossing. We could move east, to the headwaters of the Drewenz. But the terrain on this side is covered in dense forest, we would only advance slowly with all these damned wagons, and the Order will be on our arse the whole time. We would also have to go by Ilgenburg eventually, where many of these German fuckers are living in and around the castle. The easiest thing to do there would be to sack the town.”

Kat lifted her skirt as their way led them down to a small basin between two hills that the previous rain had filled well. “So more killing of innocents?”

“Let's just hope that the punishment of the Lautenburg plunderers has provided a deterrent example for the others.”

“Sure, because the rest of this army is so much more peaceful,” Kat murmured with a voice bitter as bile.

Henry put his boot down into the mud, and thought of Matthew and Fritz and the table full of empty beer mugs, and Matthias was lying flat on his back on the ground, he could not remember whether it had been the alcohol or one of the other boys who had knocked him down. Henry's feet were unsteady on the wet ground, balancing Fritz up on his shoulders, and Fritz was pissing through the window right onto Beran's bed. “I have been drinking enough all night,” Fritz had said. “It will barely stink.” Beran had stormed out of his house in panic, naked as God had created him, screaming at his wife that he had known all along they should have repaired that damned roof a while ago.

A few months later, it had not been rain nor piss seizing his bed, but the greedy hands of flames. Henry's unsteady feet on the ground. Not only mud this time, but blood and ash and scorched earth. War is a nasty business, whispered so clearly into his ear, that Henry spun around, convinced that the soldier from before must have followed them, that his blue eyes, his broad chin must have only been a mask, but there was no one with them. He felt cold all of a sudden, despite the summer heat. “Do you think we can make it?” A question out of curiosity second, and out of a need for distraction first.

“To Marienburg?” Žižka asked. “No, they won't let us get much further north. As soon as we cross the river, there will be battle.”

“How well are they equipped?” Godwin lifted a bigger branch from the ground and tossed it to the side. They had reached the outer rows of trampled fern and scattered beeches now that lined the edge of the forest. The tents around them showed the colours of Moravia and Bohemia. “Do we have any definitive numbers on how many men the Order has?”

“Enough to win, that's all that matters.” Žižka greeted Kubyenka who was sitting by a cooking pot, and stopped a few feet later in front of their tent, where he opened a crest to take out a bulbous bottle of wine. Sweet red, mixing with the smell of boiled onions and mutton, and leather and steel. The muffled talking inside the tent stopped, a plank bed creaked, then Sam and Mirtl stuck their heads through the tent opening with expectant looks, and Hans walked past them, stepping outside and over to where Henry stood. Somehow their hands met while neither of them was looking at the other one.

Žižka took a large sip of the wine, before he finally turned and faced his pack. His eyes moved from Kubyenka up to Kat, and then over to Sam and Mirtl, and to Godwin, and finally rested on Hans and Henry. “You know, I'll admit it. When you came to us yesterday, I was furious. I thought that last month in our dear Alma Mater you had all made your decisions, and I considered them wise ones. Choosing family and duty and the safety of your own skin seemed like the right thing to do. And then you fucked it all over. For what? For adventure? Or for me? No, no, spare me your answers.” He drank from the wine again, even longer this time, and when he finally put the bottle down again, he used his free hand to rub his blind eye, while the right one glistened like a layer of fresh ice on a lake. “Your motivations do not matter. Because when you all will meet your fate out there on the battlefield, whatever it may be, I will feel responsible for it one way or another. But I have learned to accept your decision anyway. And you know what? I'm even glad about it. It's a nice end to our tale, isn't it?” He laughed, and it sounded almost mad.

Hans squeezed Henry's hand a little tighter. Godwin and Kat raised their brows at each other. Mirtl looked up to Sam, until they both seemed to realise something the others couldn't and took a quick step away from each other. Kubyenka reached up from where he was sitting, took the bottle from Žižka's hand and poured the rest of it into the cooking pot, where the alcohol went up in smoke.

Žižka shook his head as if in disbelief. “So many years of having you bastards constantly on my arse. And now I led you until the end of the world. Just so we can all die here together.”

* * *

Lake Lubian was only a gigantic hole of black, as if someone had drained all the water out of it and replaced it with pitch. The Polish soldier down at the bank with his feet in the knee-high reed weaved his torch around wildly, perhaps to chase away the bloodsuckers, and Žižka thought that if he let it slip in all his brandishing and had it fall into the pitch lake, it might make for a nice fire.

But then again, it was warm enough as it was. Though the air smelled like rain. It might take a while until it had reached them, tomorrow morning perhaps. When the battle began.

Žižka narrowed his eye as he looked to the opposite, northern side of the lake, but it was too dark to recognise anything, now that the sun had already set, and a small kink in the middle of the lake blocked the view on the Tatar camp from where he was standing. He could make out the Lithuanians, however, over to his left, but only in the form of a soft glowing light between the trees, as they had built their tents a little way off the lake, up on the low line of hills, under the protection of the forest. And a little bit further into the same direction, the Teutonic Order had settled. Resting and waiting for the day to come.

Insects were buzzing, frogs were croaking, birds were screaming. In the tops of the trees, the wind moaned, it pushed the water into the banks, rustled the reed and the duckweeds, stroke his hair with its warm fingers. Štěpán still had his hat, and whenever the boy was not with Jagiełło, he was wearing it with pride. Hm. Žižka would have to get a new one, after the battle. A proper one, like those that the Polish nobles liked to wear. It would be a treat to himself.

“No, I tell you, it never looked like that before.”