Text

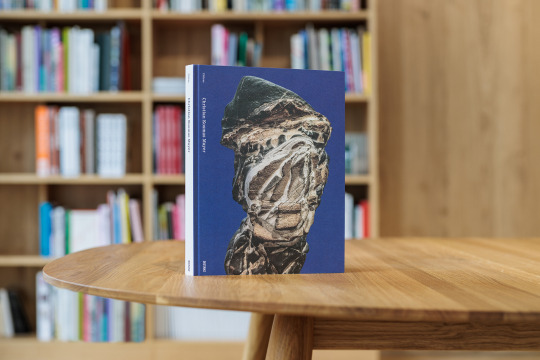

First Monograph, 2023

Richly illustrated, this publication presents the first comprehensive overview of Christian Kosmas Mayer's practice. His collaborative and multi-faceted approach is reflected in seven commissioned essays that focus on individual key works as well as the artist's oeuvre. The authors from different disciplines examine the connection between technology, memory and care in the artist’s practice in their own unique way. The book is rounded off by a glossary with a selection of important projects from the last ten years and essays by Noit Banai, Timo Feldhaus, Seph Rodney, Liv Nilsson Stutz, Sarah Wade, Stephen Zepke, and an interview between Mark Dion and the artist.

EDITOR: Phileas. A Fund for Contemporary Art

DESIGN: Marie Artaker

LANGUAGE: English

FORMAT: 21 × 28 cm

FEATURES: 256 pages, 211 color images, flexcover

PUBLISHER: DISTANZ

ISBN: 978-3-95476-537-9

RELEASE: May 2023

0 notes

Photo

A&I

University Gallery of the Custody, Dresden, 2021

Maa Kheru

8-channel sound installation (dimensions variable), 7 min (looped)

Golden Tongues

24-carat gold, polyamid, metall

If you love life like I do

Stainless steel, aluminum, sleeping bag, belt

210 x 76 x 64 cm

Mrs. Conant

HD-Video, 120 sec (loop)

Drawing on earlier works of his, Christian Kosmas Mayer explored cultural-historical concepts of immortality against the backdrop of the present day and the radical advances currently sweeping across the fields of biotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI).

In his research practice, the human voice plays a pivotal role as a primordial medium of expression, of vital importance in ideas relating to the afterlife, be it in ancient Egypt or the present day. Because we live in an age when AI enables us to synthesize the voices of those long-dead and thus revive them in digital form, their voices are able to float free of their bodies, living on through technology in an afterlife that is potentially never-ending. By partnering with the Chair of Speech Technology and Cognitive Systems at the TU’s Institute of Acoustics and Speech Communication, Mayer has now used the latest speech-synthesis technology to produce sounds based on the vocal tract of a specific human being who lived 2000 years ago. From these sounds, he has composed a moving and enigmatic multi-channel sound piece that combines the archaic with the hypermodern and upends our conventional notions of age and the passing of time. (more information on this work can be found in this interview: https://between-science-and-art.com/artist-in-residence-christian-kosmas-mayer/)

The disembodied and lingering presence of the voice finds its materialized and ossified echo in the sculpture series the Golden Tongues. Models of human tongues from the late 19th century preserved in the Historical Acoustic-Phonetic Collection at the TU Dresden were the source for replicas that were transformed into extremely durable metal objects. The technique of gilding has been used since antiquity to lend objects a timeless finish, giving them the chance to escape the finite time scale of each passing human civilization.

Mayer is especially drawn to such phenomena and objects, which, even in death, know no rest and drift through time, resurfacing at various points in history in different contexts and charged with different meaning. This is also evident in his AI-generated animations of vintage photographs dating from the mid-19th century, when photography itself was still considered a magical medium by many. The late sci-fi author and physicist Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008) once claimed that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. If that be true, then the latest advances in biotechnology and AI will one day have previously unimagined ways to seduce us into interpreting the ghostly phenomena of autonomous algorithmic computations as works of magic.

As a commentary on the current discourse surrounding AI applications in biotechnology, Christian Kosmas Mayer’s poetic, sensual, and at-once imaginatively speculative approach presents a glimpse of this future. And rather than examining it as separate to Humanism and traditional knowledge systems, Mayer shows how such a future is actually rooted in and predetermined by them.

These works were supported by Schaufler Lab@TU Dresden

-------------------------

Text on the single works:

Maa Kheru

Egyptian mummies are physical relics of a highly advanced ancient civilization for which the search for immortality was a defining cultural impetus. In his performative approach to a 2000-year-old male mummy, Christian Kosmas Mayer draws on the ancient Egyptian belief that the dead can only attain eternal life if their voices are revived. Using data obtained from computed tomography (CT) scans, researchers were able to create an exact replica of the mummy’s vocal tract, even endowing it with a movable silicon tongue. Mayer played this artificial vocal organ as though it were an instrument and produced a range of vocal sounds from which he then composed a multi-channel sound piece. Falling somewhere between scientific precision and poetically speculative experiment, the resulting sounds take us into the depths of time and combine the archaic with the hypermodern.

Golden Tongues

The TU’s Historical Acoustic-Phonetic Collection contains a ceramic model from 1895, made to illustrate the formation of vocal sounds in human speech and song. Made of changeable parts, this anatomical model served as a teaching aid in vocal training for professional singers, which is why some of its parts include distinct shapes of the human tongue, each representing a different sound. For his sculpture series, Christian Kosmas Mayer appropriates the forms of these historical models and renders them in a material that transcends their original functionality. By gilding his replicas, Mayer makes use of an ancient cultural practice that has always been associated with the pursuit of timelessness. Any use of “immortal gold,” as alchemists called it, is not just an aesthetic decision – it is also a reflection of an attempt to transcend the lifespan of human civilization.

If you love life like I do

Cryonics is the term for the preservation of human bodies at very low subzero temperatures, in the hope of being able to bring the deceased back to life at some unknown point in the future. In speculative anticipation of possible breakthroughs in medical science and technology, the bodies are cooled in liquid nitrogen to -196 degrees Celsius and stored in metal containers. Several hundred bodies are currently being kept in what is hoped to be a suspended rather than final state – and that number is on the rise. After conducting research into a US cryonics company, Christian Kosmas Mayer made these sculptures to point to the little-known existence of these modern-day mummies and visualize this as yet indefinable duration of icy quiescence. Upside down in sleeping bags, they await their own personal resurrection through science.

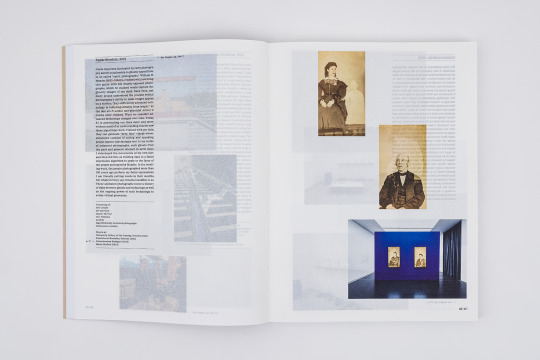

Mrs. Conant

Deepfakes use artificial intelligence to generate fake videos whose simulated content seems convincingly real. As such, deepfakes are part of a long tradition of manipulative visual techniques going back centuries. The American photographer William H. Mumler (1832−1884) was a pioneer of photographic manipulation, using double exposure to create spirit photographs in which he claimed to capture the spectral image of the dead. Christian Kosmas Mayer takes these historical fabrications and combines them with the latest technology to create AI-generated animations of the people in Mumler’s photographs. Guiding the mimical transformation of the originally still portraits are Mayer’s own facial expressions. The artist recorded the movements of his face on video and then fed the training data to a facial expression algorithm. In the final work, we see the artist literally putting words in the mouths of people photographed more than 150 years ago, but whatever they are saying remains inaudible to us.

#schauflerlab@tudresden#immortality#ai#cryonics#antonginzburg#williammumler#mummy#voice#tongue#reanimation

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

Mrs. Conant, 2021

Full HD-Video, 120 sec (loop)

Deepfakes use artificial intelligence to generate fake videos whose simulated content seems convincingly real. As such, deepfakes are part of a long tradition of manipulative visual techniques going back centuries. The American photographer William H. Mumler (1832−1884) was a pioneer of photographic manipulation, using double exposure to create spirit photographs in which he claimed to capture the spectral image of the dead. Christian Kosmas Mayer takes these historical fabrications and combines them with the latest technology to create AI-generated animations of the people in Mumler’s photographs. Guiding the mimical transformation of the originally still portraits are Mayer’s own facial expressions. The artist recorded the movements of his face on video and then fed the training data to a facial expression algorithm. In the final work, we see the artist literally putting words in the mouths of people photographed more than 150 years ago, but whatever they are saying remains inaudible to us.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Wetterleuchten am Horizont, 2021

Memorial for Johann Gruber at the University of Pedagogy of the Diocese Linz

Three-part installation:

Excerpts from the poem "Lamentation in Memory of Johann Gruber" by Jean Cayrol (1945) on tactile handrail signs made of chrome-plated aluminum, hand-painted 3D replicas of Stone and Bronze Age objects from the collection of the Natural History Museum Vienna, glass showcase, wooden boxes, brackets, text, Soup

“In his work “Weather lights on the horizon”, Christian Kosmas Mayer recalls the priest Johann Gruber who was murdered by the Nazis, without falling into the manner of traditional monumental monument culture and the heroization of a person associated with it. Rather, he strives to bring history to life and allows the boundaries between then and now to appear permeable. It is sufficient to look at the current socio-political developments with their racist and anti-Semitic excesses in order to recognize how much the past continues to have an effect in the present and how new forms of threat are assumed. Gruber's actions were like a flash of light in dark time, metaphorically like “weather lights on the horizon”, an energetic force that could not be captured in an ideological corset and that threw spotlights on a wall of silence.

Johann Gruber was a clergyman who opposed the Nazi dictatorship and saved others in an environment of inhumanity with commitment and loss of his life. He was someone who tried to implement reformist ideas in the education of children and young people, who, as the head of an institute for the blind, made his eyesight and clairvoyance available to others, who was against the so-called “Anschluss” to Hitler Germany and who ultimately paid with his life for standing up for other concentration camp inmates. But he was also someone who had been forgotten in the course of the typically Austrian suppression of history and only survived in our memories through the reports of some survivors.

So we are not only dealing with a political or religious martyr, but with a very complex personality who linked ecclesiastical and secular agendas and who, thanks to their skills and intelligence, assert themselves for a while even under the most adverse and humiliating circumstances and undermine the Nazi system. Gruber was someone who was not only subject to history, but who also wrote it himself. Such a personality is a predestined reference figure for an artist like Christian Kosmas Mayer, who is extremely well versed in history and is interested in the complexity of historical events and their impact stories - albeit not in an academically rigid form of science, but in an open artistic practice. Mayer undermines the strict boundaries between art and science and thus opens up new fields for both areas. At the same time, he also questions the notion of rigid chronologies and separate times.

As always in his work, the artist has researched thoroughly. He investigated the historical traditions and sources, he interviewed contemporary witnesses in order to gain as complex a picture of Gruber's personality as possible and to clarify the question of how this priest was able to subvert the rigid control system of the Nazis in the camp.

Mayer's work refers to the fact that the lever for this subversive action was Gruber's ability to communicate with the outside world, after the camp management assigned him the function of "museum capo" in the course of archaeological finds near the camp during excavations for a railway line: Gruber was responsible for looking after the Bronze Age objects as well as for communication with the Federal Monuments Office and the exhibition in the museum barracks.

The archaeological finds, which were immediately used in a racist manner by the camp administration as relics of a supposed Germanic master race for propaganda purposes, were mostly vessels that had to be sent to Vienna for restoration and provided hidden space for smuggled goods.

Gruber succeeded in smuggling cigarettes out of the camp by bribing the supervisors, which were sold on the Vienna black market, in order to use the money to obtain relief and life-saving measures for his fellow prisoners. He had also seen through and exploited the corruptibility of the system for his activities. Resistance alone would not have been effective, but the supposed cooperation with the system would have been. The emphasis here is on supposedly. In one of his texts, Mayer himself recalled that the concentration camp's horror system was based not least on playing off different groups of prisoners against one another and relying on the provocation of the lowest human instincts in order to keep the machinery of extermination going. While Gruber, in contrast to this, practiced the principle of love for one's neighbor under the most adverse circumstances and the greatest danger to himself. Gruber's attitude was not one of cooperation, but one of subversion.

Gruber's subversive behavior is negotiated here by an art that for its part takes unusual paths beyond conventional means: it uses the medium of language and literature, it makes use of the forms of representation of archeology and the technique of participation. But let's look at it one after the other: In his work, Mayer resurrects Gruber's past and his opponents and tormentors by thematizing three central aspects in their context: First there is Gruber's role as head of the “Institute for the Blind”, which is remembered here in the form of Braille on the handrails of the staircase. It is that part of the architecture that gives you support and at the same time guides the way - a metaphorical function if you consider Gruber's work for the blind as well as for the sighted. The text Mayer chose for this comes from an inmate whose life Gruber saved. It is the French writer Jean Cayrol (who later became famous) who after the war and his liberation put a poetic memorial to his savior Gruber in the form of a lament. Mayer translates this literary requiem into Braille, giving it a material, but also very delicate and fleeting presence and form. Not only Gruber is remembered here, but also the memory form of the poem for Gruber. It is the Savior and the Saved who appear equally in this poem. Here, too, the artist intertwines the past and posterity, pointing to a causality between times that undermines our idea of the polarity of the past and the now.

This scriptural installation leads straight to the second part of the work, namely to the showcase in which there are replicas of some of the archaeological finds. In order to be able to make these replicas, the artist investigated the path of the Bronze Age artefacts after the war. He found out that some of them had ended up in the depot of the Natural History Museum in Vienna via Nuremberg, where they are still stored today. The copies are made so precisely that they cannot be distinguished from the originals at first glance. Again, the past appears here in the form of the present. But the past is not only present here through new copies, but it is also a question of doubles of originals, which themselves slumber as symbols of the suppression of history and have so far been withdrawn from the public. It is not only the originals that are represented in the showcase, but also the associated history of their delayed perception that becomes visible here. The originals "hidden" in the depot refer to an irony of history: once used to hide contraband, they are now the hidden themselves - as if the excavation had brought them nothing but to remain "buried" again. It must be said, however, that the museum officials have given the artist very generous support in his research work in bringing these finds and their history into the public eye.

Mayer has uncovered another meaning here, which one can rightly call an archaeologist: because excavations of extinct cultures like those of the Bronze Age have something to do with cemeteries and their opening. Archaeological sites are associated with the fatal of transience and the morbid - all of these characteristics, which in an ideologically tightened form, also apply to the concentration camps as death factories. Burying and hiding murdered people and digging up extinct cultures came together in Gusen. And Gruber represented both sides at the same time. He supervised the excavations of a regime that ultimately buried him in the figurative sense, but also in fact. Mayer reveals this cruel causality with his replicas. The museum - in the form of the display case - is therefore the exact opposite of a fossilization of history that is often found in archaeological museums. It is an enlivening of a machine of death and its ideological prerequisites disguised in the form of museumization. The fact that the Nazis used the excavated objects to legitimize an abstruse Aryan genealogy and its racial superiority shows how much the camp management endeavored to give the past a present status by twisting history.

The third aspect of the artist project relates to the so-called “Gruber soup”, a simple soup probably made from potatoes and beets, which Johann Gruber was able to organize for his fellow inmates with the smuggled money in order to ensure their survival. A soup served in the cafeteria on certain occasions should be understood as the introduction of a new ritual that brings teachers and students together in order to renew and keep the memory of Gruber's ideas of solidarity and care in a sensual way. Again, it is a visualization of history, which can now also be understood in the sense of a humanistic mandate to the participants.

Remembrance work like the one carried out by this art project means, by commemorating a specific person, also to sensitize for a certain historical situation and its current consequences. In contrast to many monuments, which lag behind their own time in their design, we are dealing here with a "monument art" that brings its historical theme up to the present. Johann Gruber was a personality who was ahead of its time or who worked against it - and whose reformist ideas made his reactionary enemies look old. Seen in this way, too, this type of art corresponds to the type of his mind.”

Rainer Fuchs Deputy director of mumok - Museum of Modern Art Vienna

0 notes

Photo

MI, 2020

With Andreas Fogarasi at Galéria Vintage, Budapest

Atlas/Pilot, 2016/2020

Pine trunks (supporting pillars from underneath the Berlin City Palace), carved

214x29 cm

280x39 cm

267x30 cm

Christian Kosmas Mayer’s carved pine trunks were unearthed in 2012, after the demolishing process of Berlin’s Palast der Republik, a symbolic building of the GDR, erected in the seventies. They were originally submerged in the swampy soil 300 years prior, supporting the enormous structure of the Prussian Berlin Palace that once stood there. Mayer purchased some of these now functionless supporting elements at an auction. Based on photos of the Atlas figures that were once adorning the ornate stairwell of the palace, he had the sculpture details carved into the pillars in a smaller, rougher form. The memory of the enormous figures, in this way, is closely linked to the history of the urban palace that was blown up in 1950, and recently partly reconstructed as a museum – and, in a more general sense, with the erasability and rewritability of memory. With his carved wooden pillars, the aim of the artist – who simultaneously appears in the role of the purchaser and the commissioner of the work – is not so much to commemorate an important historical event with his negative obelisks, but to memorialise an erased and disappearing past, emerging to the surface in ever newer forms. The metamorphoses of the representational patterns of past systems become especially timely today in cases where the powers that be, assuming a specific perspective of the past, dress their new buildings in “old clothes” and use them as tools for politicising history.

The examination of the morphology of the past and present constitutes a basic element of both Fogarasi and Mayers’ art practice. In works by the latter artist, history and the present appear to layer on top of one another almost like a frottage, where, with every subsequent copy, the original sign and the information contained therein are transformed. In this way, the process of creation is rendered visible. Andreas Fogarasi primarily focuses on the internal mechanisms of culture. He lifts images that seemingly lost their significance out of oblivion. He zooms in on city structures and buildings, which, with time, lose their original meaning. The works of both artists share the element of preservation and the strategy of reprocessing, an examination of the relationship between creativity and power, and the raising of awareness about entropy, which can also be experienced in culture. In a world that is falling apart, Fogarasi and Mayer seek the possibility of slowing down and of intermediate positions – between a fixed vantage point and shifting perspectives, accidental discoveries and methodical research, dismantling and construction. Their present exhibition, which takes details that have been buried or forgotten and uses them as a starting point, explores such general concept pairs as concealment and visibility, erasure and rewriting, or the disappearance and preservation of knowledge. Both artists are interested in the invisible structures of, for instance, power or time, as well as in the mutability or constancy of frameworks and supporting elements – and, by taking these as a premise, the intersection of the past and present.

Excerpt from the press text by József Mélyi

All photos: BIRÓ Dávid

Courtesy of Vintage Galéria

1 note

·

View note

Photo

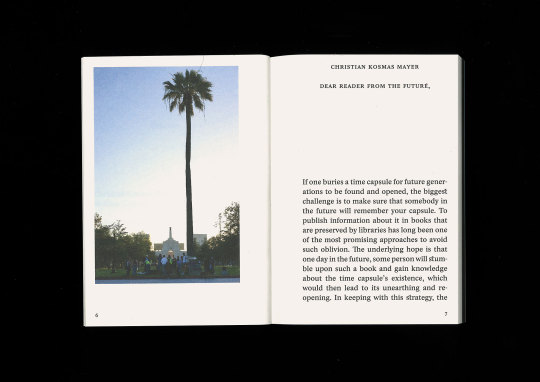

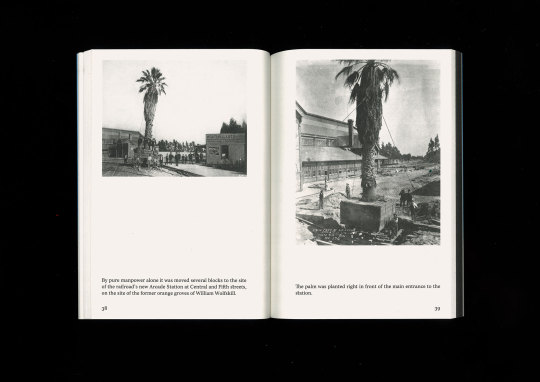

Edited by Christian Kosmas Mayer

Texts by Andrew Berardini and Geoff Tuck

Design by Astrid Seme

Dimensions: 10 × 14.5 cm

Volume: 116 pages

Language: english

Edition: 500

Publisher: Mark Pezinger Verlag

No.3 of the Black Forest Library

ISBN: 978-3-903353-00-8

Amongst the millions of palm trees in Los Angeles there is one that stands out: The Exposition Park Palm Tree. Having been moved three times within its lifetime, this palm is L.A.’s oldest. It is a mute witness to the growth of the city from its early days as a pueblo to the megalopolis of today. By 2115 this tree will long be gone and forgotten when the content of an unearthed time capsule reactivates this story. This book is the official record of this Palm Capsule.

0 notes

Photo

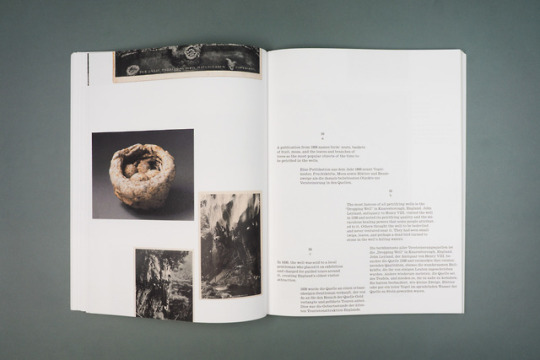

Unverhofftes Wiedersehen, 2019

Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin

If you love life like I do (blue/yellow), 2019

Stainless steel, aluminum, sleeping bag, belt

each 210 x 76 x 64 cm

Silene, 2019

Primeval plants of the genus Silene in vitro, laboratory glasses, culture medium, plant light, glasshouse made from mouth-blown glass

(glass object designed by Kristýna Markvartová)

Petrified (shoes), 2019

Shoes, minerals (deposit from water of a natural petrification well), custom made box

Petrified (cans), 2019

Cans, minerals (deposit from water of a natural petrification well), custom made box

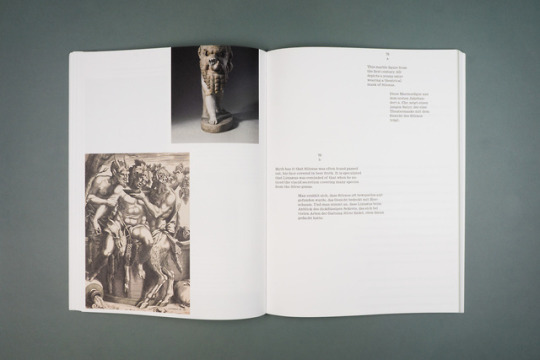

Die Bergwerke zu Falun, E.T.A. Hoffmann, 1819, 2019

Inkjet on copper plate, passe-partout, soot, frame, museum glass

100 x 80 cm

Des ersten Bergmanns ewige Jugend, Achim von Arnim, 1810, 2019

Inkjet on copper plate, passe-partout, soot, frame, museum glass

100 x 80 cm

Romanticism strikes me as the last epoch in which the secularized and emancipated individual sought to regain a metaphysical dimension. When Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné traveled to Falun in 1733 to inspect the petrified miner on exhibit there in a vitrine, his subsequent verdict cut like a knife through what he perceived to be the superstitious sensationalism of the local population: “He is not petrified but only salted in vitriol, and as salt dissolves in the air, it too will pass over the course of time.”

However, at the beginning of the 19th century, when the story of the petrified miner became famous in Germany by way of Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert’s book “Views from the Dark Side of Natural Science”, it sounded far less profane. The focus of Schubert’s narrative lies in the unexpected reunion between the body of the young miner, who was buried for 50 years underground – apparently intact and untouched by time – and his fiancée, by then a frail old woman who identified him. Various temporalities interpenetrate here and permeate history metaphysically: the conserved body of the miner, kept young by his transformation into inorganic matter, in contrast to the biological decay of his aged fiancée, whose memory of the miner, in turn, seemed to reverse time. After Schubert, many well-known German Romantic writers recognized the potential impact of this narrative, including E.T.A. Hoffmann, Johann Peter Hebel, Achim von Arnim, and Friedrich Hebbel. They all dealt with this story in various ways and pulled it farther and farther into the realm of fiction. The space of the mine is of particular importance in these narratives; it is an allegory for the individual psych, and one’s descent into it, to a place where one comes dangerously close to the hidden layers of the unconscious. At the same time, the mine is the first completely artificial and technological space created by man. The drawings of the Falun copper mines reminded me of animal burrows when I encountered them in a Swedish archive of 18th century hand-drawn maps. They are similar to how I imagine the tunnel-systems of the Arctic ground squirrel to be, which they have been digging in the frozen permafrost since time immemorial. When scientists found a 32,000 year-old squirrel burrow deep under the Siberian soil, thousands of frozen seeds fell into their hands, seeds that the animals had deposited in their feed stores, to eat after hibernation. The Arctic ground squirrel has the longest hibernation of any animal species, lasting 8 months without interruption, with a body temperature of -2 degrees Celsius. The heart almost stops beating, breathing stops for several minutes. It is as if the animal enters a state between life and death so as to survive the extreme conditions of the Arctic winter, only to be revived with the arrival of Spring.

Adepts of cryonics probably imagine the time they will spend headdown in steel containers, their bodies cooled down to -140 degrees Celsius with helium, after they have been classified as clinically dead, as a similar sort of hibernation. It’s an attempt to move a limit that until recently was considered immovable. If biological decay can be stopped, can we not justifiably hope to be revived at some unknown point in the future, like the 32,000-year-old seeds from the burrow of the Arctic ground squirrel that were resuscitated in a Russian laboratory?

The plants grown from these seeds represent a living piece of ice age that can no longer be found in today’s nature. Certain sci-fi books inevitably came to my mind when I first heard about them, along with pop-cultural references such as Frankenstein or Jurassic Park. I was all the more astonished by the delicate inconspicuousness of the plants when I first saw them. They belong to the Silene genus of flowering plants. Once again Carl von Linné enters into this text, a figure who – according to Strindberg – was more of a poet than a naturalist. In order to establish his classification system, he had to find thousands of names for classifying the plants and animals that were known at the time. One of these names is Silene. It is believed that it refers to Silenus, demi-god from Greek mythology and tutor of Dionysus. A multi-layered figure, something between a ridiculous drunkard and a wise guide. The wisdom of Silenus shows in his answer to King Midas’ question regarding what is the most desirable thing of all in life: “the best thing for a man is not to be born, and if already born, to die as soon as possible.” Today, as this genus of plants is known foremost for its inconceivably old Ice Age specimens, its name seems to retroactively produce a certain irony. In view of the life history of these plants, one might rather think of the following Apollonian principle: “The worst thing is to die soon, but the second worst thing is to die at all.”

– Christian Kosmas Mayer

#German Romanticism#falun#copper#reanmiation#silene#permafrost#ice age#cryonics#petrification#petrification well#water#sooth#fire#sleeping bag

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Aeviternity: the book

Edited by: Rainer Fuchs, mumok - Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, 2019

Foreword by: Rainer Fuchs, Karola Kraus

Texts by: Daniel Muzyzcuk, Jenny Nachtigall

Reprints of texts by: Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Johann Peter Hebel, Achim von Arnim, Friedrich Hebbel, E.T.A. Hoffmann

Image descriptions: Christian Kosmas Mayer

Design: Astrid Seme Studio

Dimensions: 32 x 24 cm

Volume: 156 pages

Images: 23 duotone and 60 color ill.

Softcover with dust jacket

Language: english, german

ISBN: 978-3-902947-65-9

Publisher: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König Köln 2019

Based on the exhibition Aeviternity at mumok, Vienna, the artist book explores the theme of conservation both as a natural and as an artificial process of archiving. The collected images were consequently separated from their captions and arranged as a vertical stream within the book’s narrative. To enhance the archival sources special focus is put on the reproduction: images are printed in full color but with an erratic metallic silver feature.

#mumok#fet-mats#petrification#german romanticism#stuffed animals#walther könig#cologne#vienna#book#catalogue

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Aeviternity, 2019

Installation views: mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien

Petrifying Well, 2019

Artificial rock, wood, plush toys, limestone, water, calcium carbonate, pump

Aevum, 2019

Primeval Silene plants in vitro, Erlenmeyer flasks, culture medium, LED lights, cement, styrofoam, HD video

Fet-Mats, 2019

UV-durable print, acrylic paint, Alu-Dibond, frame

Christian Kosmas Mayer’s cross-media works and installations are based on detailed research into history and contemporary society. This is undertaken in order to critically reevaluate history and the present by placing evolutionary and natural phenomena into the framework of cultural history and science. Mayer’s work focuses on critical exploration of questions of archiving and conserving as deliberate acts that create history, shape the present, and point to the future.

A starting point for this exhibition is the architecture of the mumok building, which looks like a dark block of stone or a mine, a theme which recurs several times in the exhibition. This is evident, for example, in the true story of a young miner from Falun in Sweden, which Mayer refers to. The miner was buried alive in an accident in 1670, and his body was recovered years later in 1719, preserved in an almost perfect condition. Through all these years, vitriolic water had stopped the processes of decay, and once brought to the surface the corpse quickly became as hard as stone. An old woman near the end of her life recognized the petrified man as her long-lost fiancé. This story was particularly interesting for authors of the German Romantic movement, who made it one of the best-known tales of their own time, with texts by E.T.A. Hoffmann, Achim v. Arnim, Johann Peter Hebel, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and others.

In this exhibition, petrification is seen as a transformative process through which living materials can seem to overcome their own transience and oblivion, but paradoxically by paying with their own lives. Humankind has always been fascinated by this process, and thus attracted to petrifying springs. The natural phenomenon of petrification by water with high mineral content was used to petrify objects from everyday life over a period of months and years. The springs were originally seen as magical and bewitched places, associated with many different forms of superstition, and later they were amongst the first ever "global" tourist attractions in Victorian-age England. For his exhibition, Mayer will install an artificial petrifying spring inside mumok, which will cover a number of objects with a layer of stone during the period of the exhibition. Whether the objects underneath this stone will then be forgotten or preserved for the future, when archeologists may rediscover them, is left as an open question.

In 2012 Russian scientists found the seeds of a plant some forty meters under the ground in Siberia, which had been stored by an Arctic squirrel in its burrow and had thereafter survived in the permafrost. Working in the laboratory, the scientists managed to grow a plant from the placenta of one of these seeds. As the successors of this plant living in the Arctic region today have seen evolutionary change, this is a case of the revival of a piece of the Ice Age that must have been considered forever lost. Mayer has succeeded in integrating this plant into his exhibition as a living organism—the first time it has left the Moscow laboratory. Today, when the permafrost is slowly thawing due to climate change, this plant seems like a premonition of future reanimations, with completely unpredictable effects.

Combining nature, culture, and science, this exhibition tells a complex story about the metamorphosis of objects over time and about the transience of our own concepts and perspectives of the world. The objects and images in this exhibition are witnesses to the passing of time in a frozen moment, in which the usually schematically distinct ideas of past, present, and future, and of life and death, become fluid. We are now testing out limits that we could once hardly imagine, which is a sign of progress, improvement, and self-assurance, but also has the potential of causing new fragmentation and insecurity.

#mumok#aeviternity#solo#underground#copper mine#petrified#petrifying well#water#stone#arctic ground squirrel#seeds#silene#ice age#late pleistocene#de-extinction#in vitro#siberia#plush toys#limestone#hibernation#fet-mats#falun#german romanticism

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daguerre’s Soup, 2019

Kunstforum Wien

The FOTOGRAFIS Collection begun in 1976 marked the start of a collecting activity that comprehends photography as an artistic medium and is structured as a representative cross section of the history of international photography. The key positions of artistic photography – from the beginnings of the medium in the 1840s until the 1980s – are gathered together in the FOTOGRAFIS Collection.

The artist Christian Kosmas Mayer is taking on the role of curator for the exhibition “DAGUERRE’S SOUP”. He has selected works from the FOTOGRAFIS Collection to fashion a subjective narrative of the photographic medium that doesn’t appear to follow a clear thematic logic. The collection takes the stage in dual form: analogue originals alternate with digital images that, placed on wallpaper, cover specific sections of wall. The photographs from the collection holdings shown on wallpaper were photographed in the exhibition run-up, on the same walls that are now covered by the wallpaper. This results in a merging of the exhibition room and its visual representation, and they become congruent. This conceptual decision creates space for an anti-hierarchical interplay between analogue original and digital representation. It creates a space in which the images are subject to alternating references of time and context, complicating the customary reception of a historical collection.

Christian Kosmas Mayer also regards relating the FOTOGRAFIS Collection to current works by contemporary artists as important – as no new works have been added to the collection since the 1980s. The selected pieces share a conceptual approach towards the production and reception of images and, from a certain distance in the context of this exhibition, question the medium of photography, which is presented in the FOTOGRAFIS Collection with such ostensible homogeneity.

With contemporary positions by Heinrich Dunst, Manuel Gorkiewicz, Karin Sander and Sophie Thun

and photographs from the collection FOTOGRAFIS by Diane Arbus, John Baldessari, Margaret Bourke-White, Marcel Broodthaers, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Pierre Cordier, Guillaume Benjamin Armand Duchenne, Trude Fleischmann, Raoul Hausmann, Duane Michals, Eadweard Muybridge, Arnulf Rainer, Albert Renger-Patzsch, Ed Ruscha, Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, Paul Strand, Weegee, Edward Weston, Manfred Willmann

Curated and staged by Christian Kosmas Mayer with support from Veronika Rudorfer

#photography#history#analog#digital#wallpaper#daguerre#marcel broodthaers#double time#fotografis#vegetables#fruits

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Cycles Galore!, 2018

BMW G650 Xmoto, engraved aluminium plate, concrete, aluminium glass vitrine in RAL Ocean blue

300 x 150 x 215 cm

Site-specific permanent sculpture for the emergency mooring at the Danube riverbank in Lower Austria

Jack, Tim, and Jamie found a strange scene when they arrived at the beach of Branscombe, Southern England, on the evening of January 18, 2007. The container ship MSC Napoli had recently shipwrecked in the English Channel and lost some of its cargo, some of which had washed up on Branscombe’s shore. Like many other curious onlookers who heard about it in the news, the three friends had come to witness the events. In the old days there was a simple law: everything you found at the beach was yours. This antiquated rule seemed to be revived that night as people were taking possession of everything they found useful. Some were rolling wine barrels up the beach while others carried as many pairs of sneakers, perfume bottles and other luxury goods as they could find, all under the eyes of befuddled policemen who didn’t stop the motley crowd. Jack, Tim, and Jamie joined the salvage, attracted by engine noises coming from a container. Within, they found guys trying to get BMW motorcycles running. They spent hours helping others to free bikes before finally making free with one of their own. They first had to fit on a front wheel and then pushed it up the beach and all the way home. On their way they were interviewed by a journalist from The Daily Telegraph. The consequent news article triggered a debate over whether the beachcombers were in the right or if they were looting. When BMW reported the motorbikes stolen, Jack, Tim, and Jamie refused to return their salvage. They claimed they had only helped clean up the beach and this was their reward. Two years and many attorney letters later, BMW withdrew its claim and the three men were declared the bike’s official owners. To this day, the motorcycle has never been driven. The men kept it in storage as a memento of an unforgettable night shared by three friends. Then, one day, they were contacted by an artist working on a site-specific artwork for an emergency mooring on the banks of the Danube in Austria. They sold him the motorcycle on April 5, 2018.

5 notes

·

View notes

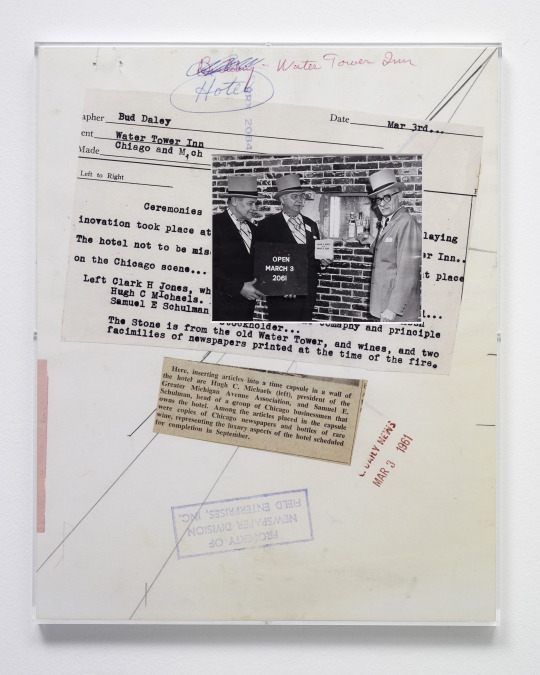

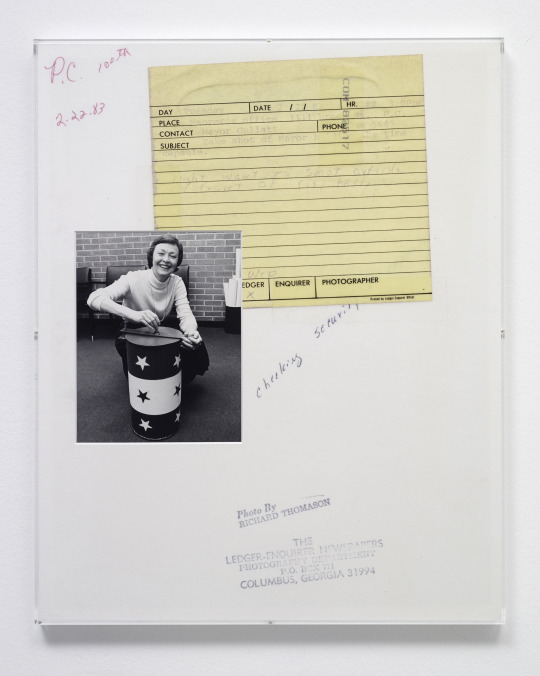

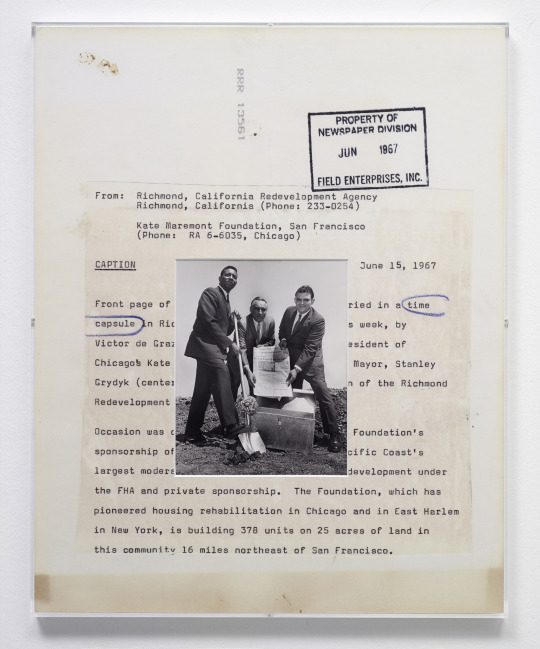

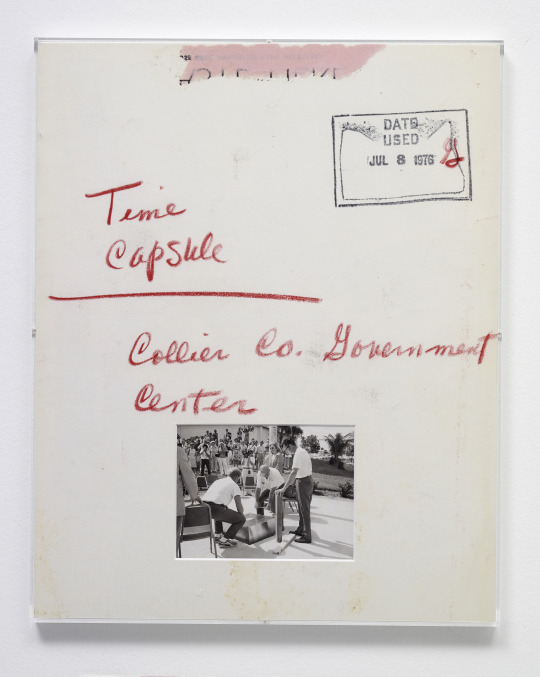

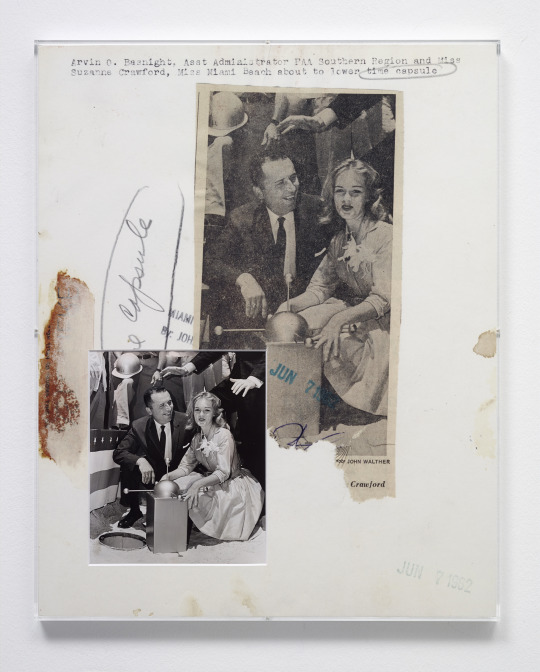

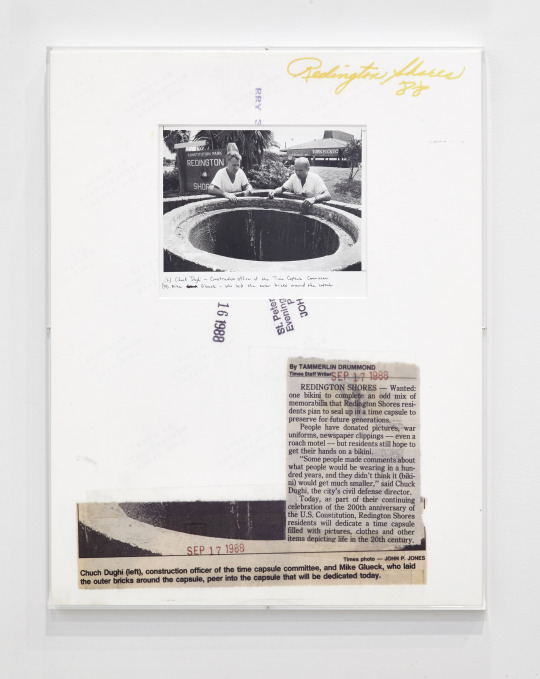

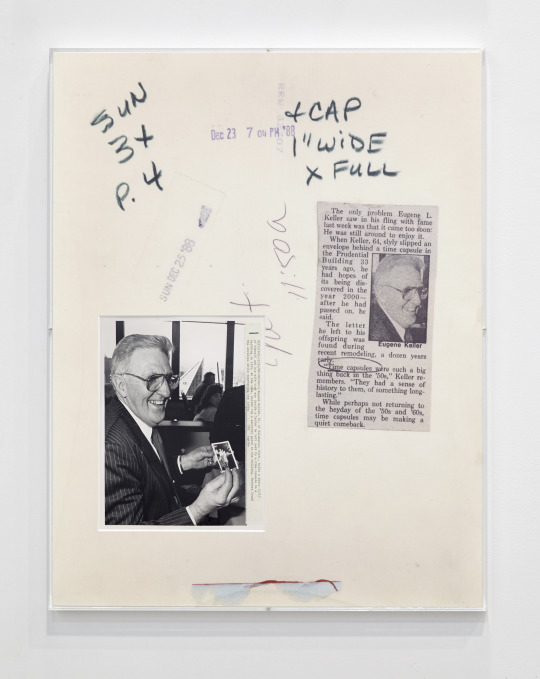

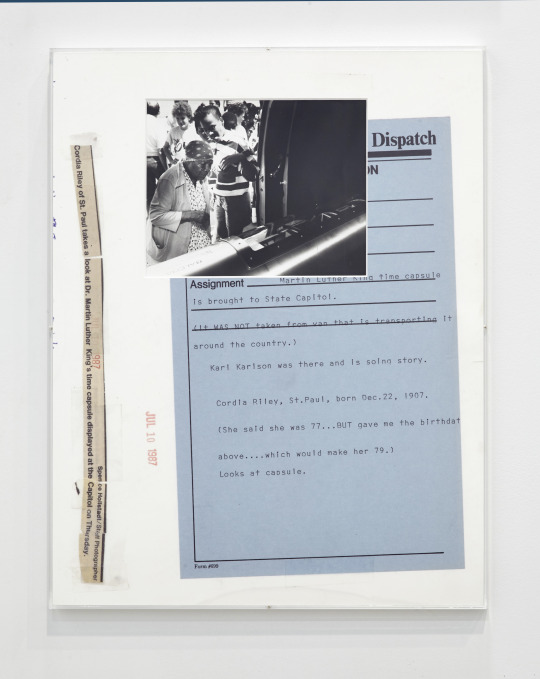

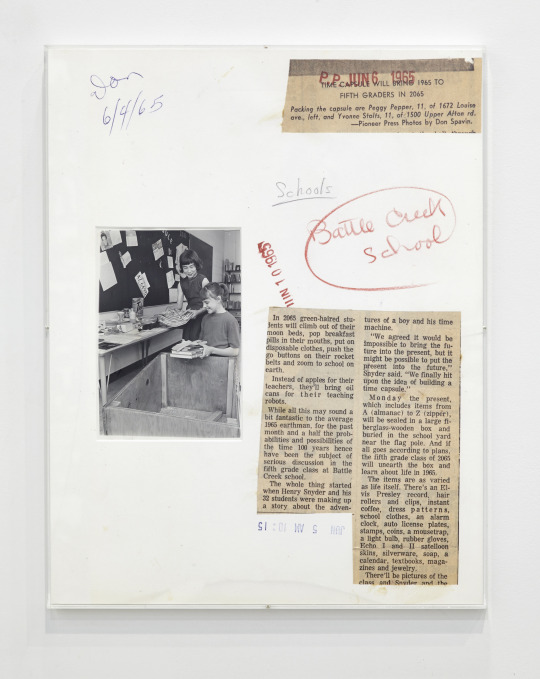

Photo

Putting in time, 2012-ongoing

Original press photo from american newspaper archive, UV direct print on passepartout, acrylic frame

54 x 67 x 4 cm or 67 x 54 x 4 cm

Installation views from the exhibition “Resonanzen”, ZKM Karlsruhe, November 2017–February 2018

0 notes

Photo

The Life Story of Cornelius Johnson’s Olympic Oak and Other Matters of Survival, 2017

Seedlings cloned from an acorn from Cornelius Johnson’s "Olympic Oak", steel, gold foil, silkscreen print, LED lamps, Mylar, laboratory jars, HD video

Installation views: “Naturgeschichten–Spuren des Politischen”, mumok, Vienna, 2017

During the 1936 Berlin Olympics, which was organized by the Nazis, every gold-medal winner was given a small oak seedling in a pot in addition to their medal. Cornelius Cooper Johnson, the US-American high jumper, won his discipline with a new Olympic record. A few minutes before the awarding ceremony, Adolf Hitler left the stadium so as to avoid having to invite the Afro-American athlete into his box. After his return to the USA, Johnson was insulted a second time by a head of state, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not invite him and other Afro-American athletes to a reception at the White House for participants in the Olympic Games. The social and economic discrimination of Afro-Americans at the time applied equally to Olympic winners like Johnson and Jesse Owens. Just ten years after the Berlin Olympics, Johnson died of pneumonia on a US navy ship, as a poor man.

He had planted the small one-year-old oak that he was given in Berlin in the yard of his parents’ house in today’s suburb of Koreatown in Los Angeles. Nearly eighty years later, Christian Kosmas Mayer searched out the tree and found an impressive full-grown oak.

In his work The Life Story of Cornelius Johnson’s Olympic Oak and Other Matters of Survival, Mayer combines this story of one oak tree with contemporary themes that can also be seen in relation with the tree. Today, the house is lived in by a Mexican family that immigrated to California in the nineteen-seventies to find work. They take care of the tree and have built up their own personal relationship to it, not based on the memory of the Olympic winner. This oak was abused by the Nazis as a symbol of nationalist hegemony, but today it seems to be showing how absurd this original idea was. Los Angeles is one the most multicultural and popular cities in the world, representing the victory of a reality that is diametrically opposed to everything the Nazis dreamed of.

With the help of a plant physiologist, Mayer was able to clone small shoots from the oak in a Los Angeles laboratory. In Mayer’s installation these in-vitro seedlings return to Europe as a sign of the future, in order to transform the story into a family history that has not yet come to an end. The fact that official permission to bring these seedlings into Europe due to the risk of introducing a tree disease rampant in California was refused, and thus they had to be brought to Vienna unofficially, is a further significant part of this story about questions of existence and survival over the years.

vimeo

#Cornelius Johnson#berlin olympics#olympic oaks#in vitro#quercus robur#los angeles#koreatown#high jump#cloning#growlights#mumok#vienna#huntington gardens#afroamerican#racism#love#embryo rescue#hybrid

0 notes

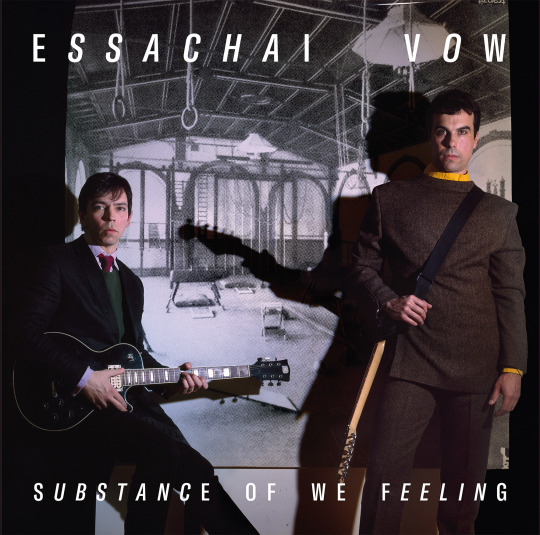

Text

Substance of We Feeling

Essachai Vow’s first 12“ LP vinyl with cover photograph by Clegg & Guttmann

Essachai Vow takes its name from the fictitious stone-age language that Anthony Burgess created for the 1981 movie "Quest for Fire" and translates to “hunger". Substance of We Feeling combines 10 songs that share a fondness for idiosyncratic compositions and influences from Jazz, Krautrock, Low-Fi and Dream Pop. The music was originally inspired by the snowy mountains around Montafon, Austria, where Christian Kosmas Mayer and Alexander Wolff have worked on an opening performance for their joint exhibition. More than one year and several recording sessions in Berlin and Vienna later, Substance of We Feeling unfolds an instrumental sound that might best be described as cinematic and has a timeless feel to it.

Available through Verlag für moderne Kunst: https://vfmk.org/shop/essachai-vow

Written and produced by Christian Kosmas Mayer & Alexander Wolff

Postproduction and mixing by Alexander Paulick-Thiel, Berlin

Final mixes and mastering by Chris Janka at Janka Industries, Vienna

Cover: The Guitar Players, by Clegg & Guttmann

Design: Dain Blodorn Kim

0 notes

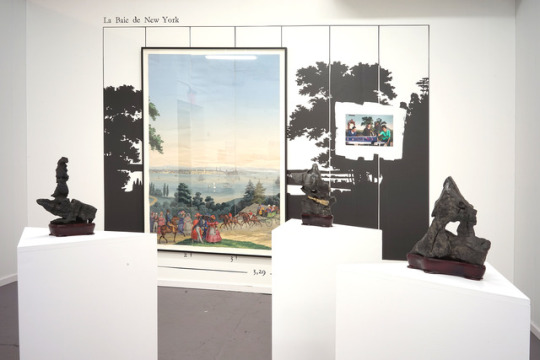

Photo

Independent Art Fair New York

Solo booth with Galerie Mezzanin, March 2017

La Baie de New York ("New York Bay"), 2017

Print on wallpaper, 3 lengths of the historical wallpaper "Les Vues d'Amérique du Nord", conservation frame, paint, photograph

329 x 262 cm / 10'10" x 8'7"

Dog Gone Crazy, 2017

Viewing stone, fragments of the historical wallpaper "Les Vues d'Amérique du Nord", birch plywood, photograph

140 x 61 x 61 cm / 55" x 24" x 24"

Immortal Riding Beast, 2017

Viewing stone, fragments of the historical wallpaper "Les Vues d'Amérique du Nord", birch plywood, photograph

137 x 61 x 61 cm / 54" x 24" x 24"

On Top of the World, 2017

Viewing stone, fragments of the historical wallpaper "Les Vues d'Amérique du Nord", birch plywood, photograph

137 x 61 x 61 cm / 54" x 24" x 24"

0 notes

Photo

Constructing Paradise

Installation view of works by Mark Dion and Christian Kosmas Mayer in the show “Constructing Paradise” at the Austrian Cultural Forum New York, February 2017

Les Vues du Brésil, 2007

Ink on wallpaper

Dimensions variable

Based on the scenic wallpaper Les Vues du Brésil (designed by Jean Julien Deltil in 1829 and produced by the company Zuber&Cie, Rixheim, France)

1 note

·

View note

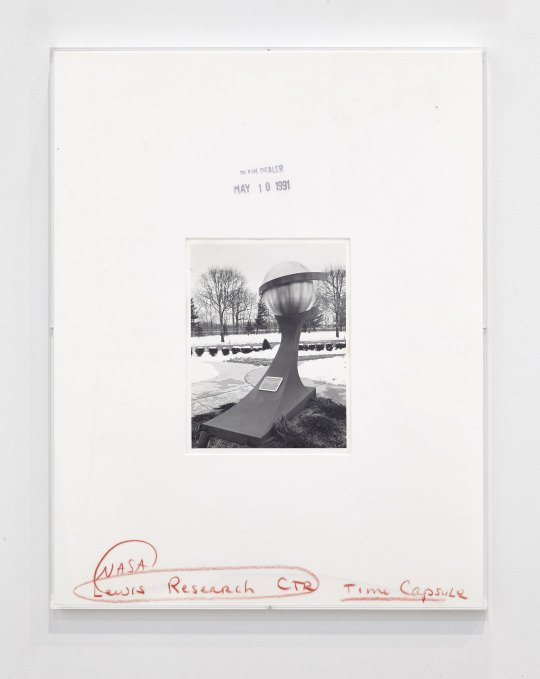

Photo

Putting in time, 2012-ongoing

Original press photo from american newspaper archive, UV direct print on passepartout, acrylic frame

54 x 67 x 4 cm

0 notes