Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Anti-Progressivism

Anti-progressivism is a broad political and ideological stance characterized by opposition to progressivism—a socio-political movement advocating for reforms in the direction of social justice, egalitarianism, environmentalism, and expansive government intervention in the pursuit of such ends. Anti-progressivism is not a singular, unified ideology, but rather a constellation of beliefs and positions that coalesce around resistance to perceived social, cultural, political, or moral changes typically associated with progressive thought.

At its core, anti-progressivism is defined not by a monolithic doctrine but by a reactionary or oppositional relationship to progressive ideologies. While progressivism champions change, reform, and the expansion of rights and state functions, anti-progressivism typically emphasizes tradition, stability, hierarchy, individual liberty (often in economic and cultural contexts), and skepticism toward centralized authority and engineered social change. Anti-progressives may view progressive movements as naïve, utopian, coercive, or destructive to social cohesion and inherited cultural norms.

Anti-progressivism has existed in various forms since the rise of modern progressivism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the United States, progressivism emerged during the Progressive Era (approximately 1890s to 1920s), characterized by political reformers seeking to curb corporate power, regulate working conditions, expand suffrage, and eliminate corruption. Anti-progressive responses arose in tandem, often defending laissez-faire economics, constitutional originalism, and federalism.

In the broader Western world, resistance to progressive change has been a central feature of conservative, traditionalist, and classical liberal thought since the Enlightenment. For instance, Edmund Burke, often considered the father of modern conservatism, criticized the French Revolution’s radical social engineering, laying early philosophical groundwork for modern anti-progressive sentiment. Anti-progressivism gained renewed visibility in the post-World War II period as cultural changes related to civil rights, feminism, sexual liberation, and secularization accelerated.

While anti-progressivism is often associated with conservatism, the two are not identical. Anti-progressivism can emerge from libertarian, nationalist, religious, or even reactionary frameworks, each opposing progressive ideas for different reasons:

Traditionalism: Emphasizes inherited customs, cultural institutions, and religious practices as foundational to societal well-being. Traditionalists argue that progressive reforms undermine long-standing moral and cultural frameworks, leading to social fragmentation.

Libertarianism: Rejects progressive calls for redistributive economic policies, expansive welfare states, and regulatory interventions, viewing them as infringements on personal and economic freedom.

Nationalism and Populism: Oppose globalist and transnational aspects of progressive ideology, such as open borders, multiculturalism, and supranational governance. Nationalists may view progressivism as a threat to national identity and sovereignty.

Religious Conservatism: Often sees progressive causes—such as abortion rights, LGBTQ+ inclusion, and secular public education—as morally objectionable or contrary to religious doctrine.

Reactionary Thought: In extreme cases, anti-progressivism takes the form of reactionism—a desire not merely to resist change but to reverse societal developments and return to a perceived earlier golden age.

Anti-progressivism manifests across several domains of public life. It cannot be reduced to a single policy position but encompasses a complex web of oppositional stances in social, economic, and political contexts.

Cultural and Moral Issues. One of the most visible arenas of anti-progressive sentiment is the cultural sphere. Progressive movements often advocate for the redefinition of social norms surrounding gender, sexuality, race, and identity. Anti-progressives respond with resistance rooted in concerns about moral relativism, identity politics, and the perceived erosion of shared cultural narratives. Topics such as same-sex marriage, transgender rights, affirmative action, and multiculturalism are flashpoints. Anti-progressives may critique these developments as forms of "social engineering" that undermine family structures, meritocracy, or religious values. In educational contexts, anti-progressivism is reflected in opposition to critical race theory, comprehensive sex education, and diversity and inclusion policies, viewed as ideologically biased or indoctrinatory.

Economic Policy and Regulation. In economic matters, anti-progressives often align with classical liberal or neoliberal economic thought, emphasizing free markets, deregulation, and limited government intervention. Opposition to progressive taxation, universal healthcare, climate regulation, and labor union expansion is common. Anti-progressives may argue that progressive economic reforms distort market mechanisms, create dependency, and reduce incentives for productivity. They frequently frame progressive economics as economically inefficient and morally problematic, citing principles such as personal responsibility and property rights.

Government Power and Centralization. A consistent theme in anti-progressivism is skepticism toward the expansion of state power. Many anti-progressives argue that progressive reforms result in bureaucratic overreach and technocratic governance that bypasses democratic accountability and individual autonomy. This is often framed in constitutionalist terms—particularly in the United States—where anti-progressives advocate for originalist interpretations of foundational documents and resist judicial activism. Internationally, similar attitudes are directed against the increasing influence of supranational bodies like the European Union or United Nations, which are viewed as conduits for progressive policy agendas.

Science, Technology, and Environmentalism. Although not inherently anti-science, anti-progressivism tends to be skeptical of the politicization of science, especially in fields where scientific discourse intersects with policy, such as climate change, biotechnology, and public health. Anti-progressives may accuse progressives of using "science" selectively to justify sweeping regulatory frameworks or cultural changes. Environmentalism, particularly climate policy, is a significant site of tension. Anti-progressives often critique progressive climate initiatives as economically disruptive, alarmist, or rooted in ideological commitments rather than pragmatic cost-benefit analysis. They may prioritize energy independence, economic growth, and technological innovation over global environmental regulation.

Law and Order, Crime, and Social Stability. Anti-progressives often emphasize the importance of law, order, and social stability. They may view progressive criminal justice reforms—such as bail reform, defunding police initiatives, or decarceration efforts—as threats to public safety and social cohesion. This perspective frequently rests on the belief that progressivism overemphasizes systemic explanations for criminal behavior while downplaying personal responsibility and the deterrent function of punitive justice systems.

Education and Academia. Anti-progressivism is frequently directed at educational institutions, particularly universities, which are seen as bastions of progressive ideology. Anti-progressives may critique curricula that emphasize postmodern theory, critical race theory, gender studies, or social justice education, arguing that these disciplines promote ideological conformity and suppress intellectual diversity. In response, anti-progressives may advocate for educational reforms that emphasize Western civilization, classical liberal education, or patriotic curricula, often under banners such as "education neutrality" or "academic freedom."

Anti-progressivism is not confined to the United States or the Anglo-American context. It exists in varied forms across the globe, often shaped by local cultural, religious, and political conditions.

In Europe, anti-progressivism is often associated with right-wing populist movements and parties that resist European integration, oppose immigration, and seek to preserve national traditions. Examples include Hungary’s Fidesz party and Poland’s Law and Justice Party, both of which frame themselves in opposition to the liberal progressive consensus of Western Europe.

In the Global South, anti-progressive attitudes can emerge from post-colonial nationalism, religious conservatism, or traditional communal structures. In countries such as India or Brazil, anti-progressive rhetoric may oppose Western cultural norms, LGBT rights, or feminist movements, often in the name of cultural authenticity or moral integrity.

Critics of anti-progressivism argue that it often masks or enables regressive, discriminatory, or authoritarian tendencies. They contend that resistance to progressive reforms can entrench systemic injustices, inhibit social mobility, and obstruct necessary adaptation to modern realities (e.g., climate change, technological disruption).

Additionally, critics point to the use of anti-progressive rhetoric to stoke populist or reactionary sentiment, sometimes leveraging fear, nationalism, or conspiratorial thinking. Some argue that anti-progressivism lacks a constructive vision for the future, offering only opposition without coherent alternatives.

Conversely, defenders of anti-progressivism argue that progressivism itself is prone to overreach, ideological zealotry, and disregard for the unintended consequences of rapid change. They claim that anti-progressive skepticism serves as a necessary check on radicalism and centralization, preserving social pluralism, personal freedom, and cultural continuity.

Anti-progressivism intersects with but should be distinguished from several other ideological currents:

Conservatism: While all conservatives are generally anti-progressive, not all anti-progressives are conservatives. For example, some left-wing critiques of progressivism (e.g., Marxist opposition to liberal progressivism) can be anti-progressive in tone without being conservative.

Reactionism: A more extreme variant of anti-progressivism, reactionism seeks not just to resist change but to reverse it. Reactionaries often romanticize past societal structures and express open disdain for modernity.

Populism: Populist movements often deploy anti-progressive rhetoric to frame themselves as champions of the "common people" against progressive "elites." However, populism is more of a political style or strategy than a coherent ideological doctrine.

Anti-progressivism is a complex, multi-faceted ideological posture that spans a wide spectrum of political, cultural, and philosophical views. While often associated with the political right, it transcends partisan lines and arises wherever progressive visions of social reform are met with principled or pragmatic resistance. Far from being a mere negation of progressivism, anti-progressivism represents a significant and influential current of thought in global political discourse—one that raises critical questions about the nature, pace, and consequences of social change.

#anti progressivism#political philosophy#traditionalism#conservative thought#political ideologies#socio political analysis#ideology#metapolitics#cultural critique#social theory#history of ideas#modernity critique#political history#philosophy of politics#civilization decline#reactionary thought#postmodern world#historical analysis#enlightenment critique#anti utopian#dark academia#aesthetic philosophy#intellectual aesthetic#deep thinkers#controversial ideas#think piece#thoughtful reads#critical theory#essay post#tumblr essay

1 note

·

View note

Text

Universality

Universality is a profound and foundational concept in science and mathematics that describes the property by which systems with vastly different microscopic details exhibit the same macroscopic behavior. It is most prominently observed in the study of critical phenomena in statistical mechanics, but it also emerges across a wide range of disciplines, including condensed matter physics, dynamical systems, chaos theory, mathematics, computer science, and even certain branches of economics and biology. The notion of universality provides a framework for understanding how complex behavior can emerge from simpler rules and how such behavior can be characterized independently of specific details, relying instead on symmetries, dimensions, and collective properties.

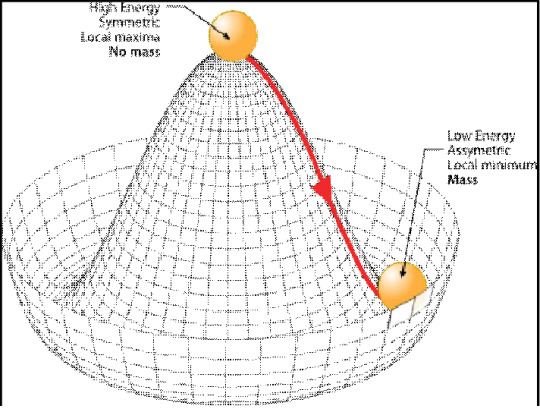

The concept of universality originated in the mid-20th century, particularly in the context of phase transitions in statistical physics. Physicists observed that vastly different physical systems—such as magnets near the Curie point and fluids near the liquid-gas critical point—exhibited strikingly similar behavior near their respective critical points. This was paradoxical because the underlying microscopic interactions in these systems were entirely different.

The resolution of this paradox came with the development of the renormalization group (RG) theory, primarily by Kenneth Wilson in the 1970s. RG provided a rigorous framework to explain how systems at different scales could be related through scale transformations, and how certain large-scale behaviors are invariant under these transformations. Universality emerged naturally from this framework: systems that flow toward the same fixed point in the space of physical theories under RG transformations exhibit the same critical exponents and scaling laws, regardless of their microscopic details. This laid the foundation for a deep understanding of universality and marked a turning point in theoretical physics.

A central feature of universality is the classification of systems into universality classes. These are groups of systems that, despite differences in their microscopic structures or interactions, share the same set of critical exponents, scaling functions, and general behavior near criticality.

The primary determinants of universality classes are:

Dimensionality of the system – The number of spatial dimensions significantly affects the critical behavior of a system. For example, the Ising model in two dimensions has different critical exponents than in three dimensions.

Symmetry of the order parameter – The nature of the symmetry breaking involved in the phase transition plays a key role. The Ising model, with a discrete Z2 symmetry, belongs to a different universality class than models with continuous symmetries like O(N) (e.g., the XY and Heisenberg models).

Range of interactions – Systems with short-range interactions often belong to different universality classes than those with long-range interactions.

Conservation laws and dynamics – In dynamical systems, the conservation or non-conservation of order parameters (such as energy or magnetization) can define dynamic universality classes distinct from their static counterparts.

Examples of well-known universality classes include the Ising universality class (scalar order parameter with Z2 symmetry), the XY universality class (vector order parameter with U(1) symmetry), and the Heisenberg universality class (vector order parameter with SO(3) symmetry).

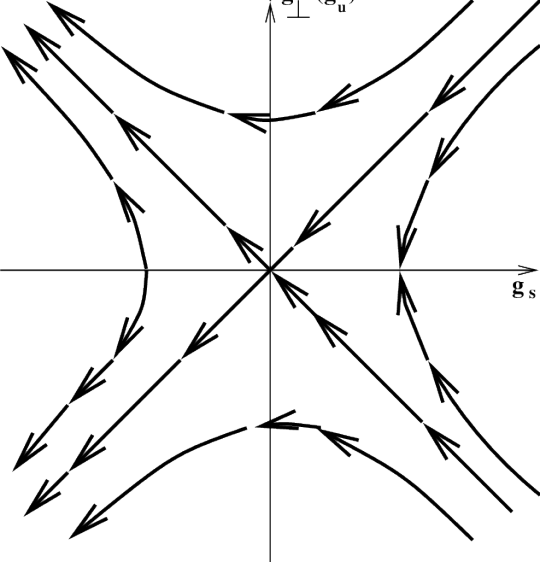

The renormalization group (RG) formalism is essential to the modern understanding of universality. It describes how physical systems behave under changes in scale, allowing for the systematic "coarse-graining" of microscopic details while retaining the large-scale features that determine macroscopic behavior.

The key idea in RG is that as one examines a system at increasingly larger scales, the effective parameters governing the system’s behavior flow under RG transformations. At critical points, these flows approach fixed points, which correspond to scale-invariant behavior. Systems that flow toward the same fixed point share universal properties—hence the emergence of universality.

In this context, critical exponents describe how physical quantities diverge near the critical point (e.g., specific heat, susceptibility, correlation length), and these exponents are determined by the properties of the RG fixed point, not the microscopic details of the system. For instance, the critical exponent β, which describes how the order parameter vanishes near the critical temperature, is the same for all systems in the same universality class.

While the concept of universality originated in statistical mechanics, its implications extend far beyond that domain.

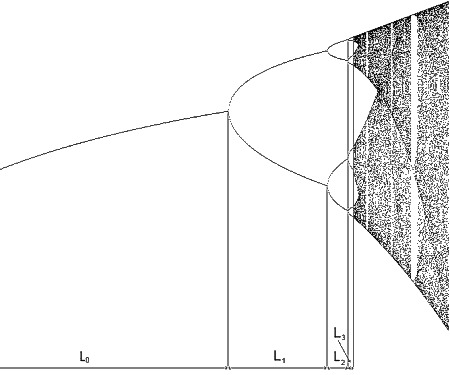

1. Dynamical Systems and Chaos

In the study of deterministic chaos, universality appears in the context of bifurcation theory and the transition to chaos. One of the most striking examples is the Feigenbaum constants, which describe the rate of period-doubling bifurcations in one-dimensional maps such as the logistic map. Regardless of the specific form of the map, the ratio of intervals between bifurcations converges to the same universal constant (~4.669), and the scaling behavior near the onset of chaos follows universal laws. This indicates that the transition to chaos in wide classes of dynamical systems exhibits universal features.

2. Quantum Field Theory and High-Energy Physics

Universality is also a key idea in quantum field theory (QFT), where it helps explain why effective field theories at low energies can be described using a limited set of relevant operators, despite the potential complexity of high-energy (UV) theories. RG methods show that low-energy phenomena are governed by universality classes characterized by the relevant operators at an IR (infrared) fixed point.

In lattice gauge theories and studies of quantum critical points, universality informs the scaling behavior of observables near quantum phase transitions, which occur at absolute zero and are driven by quantum fluctuations rather than thermal ones.

3. Computer Science and Algorithmic Universality

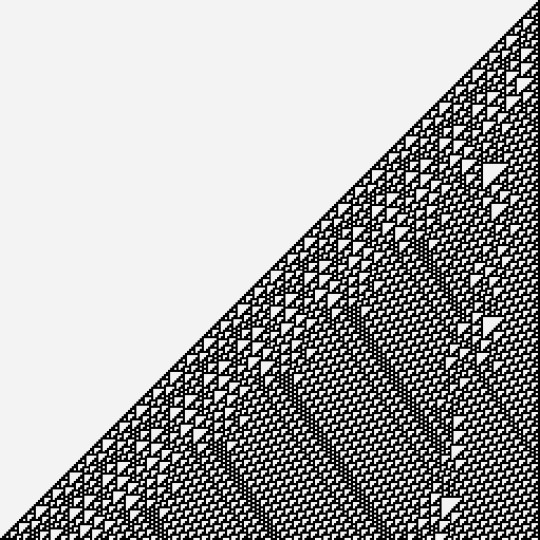

In theoretical computer science, a different kind of universality appears in the concept of computational universality, particularly in Turing completeness. A computational system (e.g., a Turing machine or lambda calculus) is said to be universal if it can simulate any other computational system. This form of universality is foundational to the theory of computation and underlies the universality of general-purpose computers.

Cellular automata also exhibit universality. For example, Conway’s Game of Life is computationally universal, meaning that it can simulate a Turing machine despite its simple local rules.

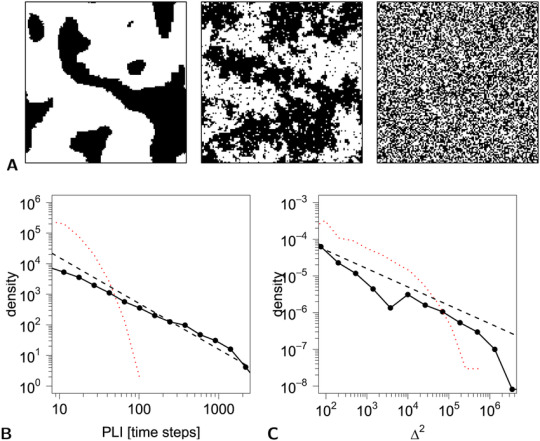

4. Percolation, Fractals, and Geometry

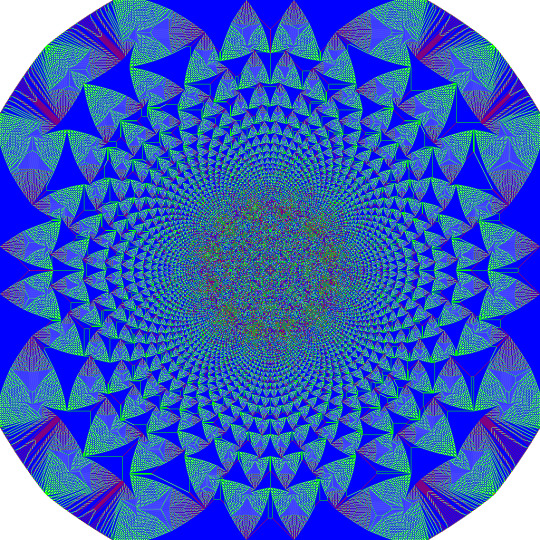

Percolation theory provides another domain where universality emerges. Near the percolation threshold, properties like the size of connected clusters exhibit power-law distributions characterized by universal critical exponents. These exponents depend only on the dimensionality of the system and not on the microscopic details of the lattice or geometry.

Fractals, which exhibit self-similarity and non-integer dimensions, are also associated with universality. The fractal dimensions of certain critical clusters (e.g., in percolation or the Ising model) are universal and can be related to the scaling laws governing the system.

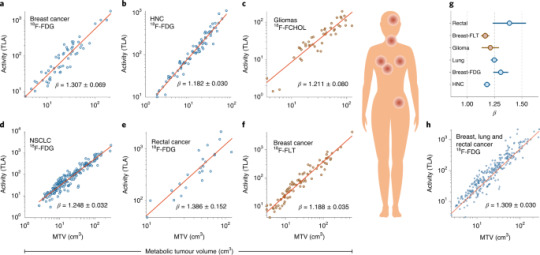

Although more speculative and less rigorously defined, analogs of universality have been proposed in biological and economic systems. For example, scaling laws in biological systems—such as the relation between metabolic rate and body mass (e.g., Kleiber’s law)—exhibit regular patterns across a vast range of organisms. Similarly, certain macroeconomic behaviors, such as power-law distributions in wealth and income or the scaling of urban infrastructure with population size, have been argued to reflect universal principles.

However, unlike in physics, the presence of complex, adaptive agents and feedback loops in these systems complicates the identification of precise universality classes or fixed points. Nonetheless, attempts to apply statistical physics and RG-like methods in these fields continue to be active areas of interdisciplinary research.

Universality in a formal mathematical sense often involves invariance under group actions, limit theorems, or fixed-point theory. For example:

Central Limit Theorem: One of the simplest manifestations of universality in probability theory. It states that the distribution of the sum of many independent random variables tends toward a Gaussian distribution, regardless of the underlying distribution, provided the variance is finite.

Random Matrix Theory: In the study of eigenvalues of large random matrices, universality appears in the distribution of spacing between eigenvalues, such as the Wigner-Dyson distribution. These distributions are universal across broad classes of ensembles, including those modeling nuclei, disordered systems, and even zeros of the Riemann zeta function.

Scaling Limits and Universality in Stochastic Processes: Brownian motion, the scaling limit of many discrete random walks, provides a classical example. Similarly, the Kardar-Parisi-Zhang (KPZ) universality class encompasses a wide range of stochastic growth models that, despite different dynamics, share the same large-scale statistical properties.

Universality challenges reductionist viewpoints by emphasizing that many macroscopic behaviors are insensitive to microscopic details. This has profound implications for how scientists model and understand complex systems. Rather than focusing on the exact microscopic state of a system, one can study representative models that capture the relevant symmetries and conservation laws to extract universal predictions.

It also exemplifies the power of abstraction and the importance of symmetry and scaling in nature. The idea that fundamentally different systems can exhibit identical critical behavior suggests that there are deep organizing principles underlying complex phenomena.

Furthermore, the concept has epistemological significance, influencing how knowledge is structured and how laws of nature are interpreted. It bridges the gap between the particular and the general, providing a unifying framework for diverse phenomena.

Universality is a cornerstone of modern science, offering a window into the fundamental structure of complex systems. From phase transitions and critical phenomena to dynamical chaos, quantum fields, algorithmic computation, and beyond, universality reveals the deep and often surprising regularities that transcend specific details. Its discovery and formalization represent one of the most profound insights in 20th-century physics, with ongoing implications for a broad range of disciplines in the 21st century. As science progresses, the principle of universality continues to guide our understanding of emergent behavior, scale invariance, and the interconnectedness of nature.

#universality#critical phenomena#scale laws#renormalization group#fractal geometry#chaos theory#complex systems#emergence#systems philosophy#interconnectedness#science thoughts#deep physics#mathematical beauty#physics aesthetic#theoretical physics#quantum field theory#computational theory#algorithmic aesthetic#symmetry breaking#phase transitions#feigenbaum constants#science lovers#philosophy of science#statistical mechanics#patterns in chaos#universal laws#scientific philosophy#epistemology

0 notes

Text

Anti-Politics

Anti-politics refers to a broad and complex set of attitudes, ideologies, and social phenomena characterized by disillusionment, skepticism, or outright rejection of traditional politics, political institutions, and political actors. While not a unified doctrine or movement, anti-politics reflects a widespread perception among individuals or groups that conventional political processes are ineffective, corrupt, self-serving, or disconnected from the needs and desires of the populace. It has manifested historically and contemporarily in various forms, including populist movements, voter apathy, protest voting, non-institutional activism, and the rise of political outsiders. Anti-politics has significant implications for the functioning of democratic institutions, the legitimacy of governance, and the health of civic life.

The phenomenon of anti-politics is not new. Throughout history, populations have displayed anti-political sentiments in response to perceived political inefficacy, corruption, or authoritarianism. During the Enlightenment, thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau expressed concerns about the alienation of the people from institutionalized politics. In the 19th century, the rise of anarchist and syndicalist ideologies often reflected radical anti-political positions that viewed the state and electoral politics as inherently oppressive or illegitimate.

The 20th century witnessed several waves of anti-political sentiment, notably in the wake of World War I and II, when political systems—liberal democracies, monarchies, and totalitarian regimes alike—were blamed for catastrophic failures. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw significant anti-political mobilization, particularly among youth and countercultural movements disillusioned with mainstream party politics, capitalism, and military intervention (e.g., the Vietnam War). In post-Soviet Eastern Europe, disillusionment with the failures of communist regimes gave way to cynicism about newly emerging liberal democracies, often resulting in high levels of voter abstention and distrust in political elites.

In the 21st century, anti-politics has resurged globally due to various factors, including globalization, economic inequality, corruption scandals, perceived failures of neoliberal governance, and a general sense of elite detachment from ordinary citizens.

Anti-politics is a multi-dimensional concept encompassing attitudes, behaviors, and ideologies that oppose or disengage from established political norms and institutions. It can manifest through:

Disengagement: Withdrawal from political participation, including abstention from voting, refusal to engage in public debate, and political apathy.

Rejection: Active denunciation of political institutions, parties, and leaders as illegitimate or corrupt.

Alternative politics: Engagement in non-institutional forms of political action, such as grassroots organizing, direct action, or communal living, as a rejection of formal politics.

Populist narratives: Framing political elites as a corrupt class disconnected from the “real people,” thereby promoting an anti-establishment ideology.

While sometimes conflated with apathy, anti-politics can also be a highly engaged position, wherein individuals channel their discontent into alternative political forms rather than conventional party politics.

Anti-political sentiment is typically driven by a combination of structural, psychological, and cultural factors:

Perceived Corruption: When political institutions are seen as corrupt or self-serving, public trust erodes. High-profile scandals, revolving-door politics, and the influence of money in politics often catalyze anti-political attitudes.

Elite Detachment: A widespread perception exists that political elites are out of touch with the lived realities of ordinary citizens. Technocratic decision-making, political jargon, and bureaucratic complexity contribute to feelings of exclusion.

Policy Ineffectiveness: When governments fail to deliver on key issues—such as economic stability, public services, or environmental protection—citizens may question the efficacy of political processes.

Partisan Gridlock: In political systems characterized by hyper-partisanship, the inability of parties to cooperate can lead to governmental dysfunction, reinforcing cynicism about the value of political engagement.

Economic Inequality and Neoliberalism: The rise of neoliberal economic policies has coincided with growing disparities in wealth and opportunity, leading some to blame mainstream politics for favoring corporate interests over popular welfare.

Media and Communication: The 24-hour news cycle, social media, and sensationalist journalism can amplify perceptions of dysfunction, scandal, and division, feeding into anti-political narratives.

Historical Legacies: In post-authoritarian or post-conflict societies, legacies of repression or failed governance can instill long-term distrust in formal political institutions.

Anti-politics can take many forms, ranging from passive disengagement to active resistance:

Electoral Abstention: Low voter turnout is one of the most visible indicators of anti-political sentiment. While abstention may be due to apathy or inconvenience, it often signifies a deliberate rejection of political choices deemed illegitimate or meaningless.

Protest Voting: Casting votes for fringe or protest parties, spoiling ballots, or writing in absurd candidates can signal dissatisfaction with mainstream options.

Populism: Populist movements often mobilize anti-political sentiment by presenting a binary conflict between “the people” and “the elites.” While populism is a form of political engagement, it frequently draws from anti-political reservoirs of discontent.

Direct Action and Horizontalism: Movements like Occupy Wall Street, Extinction Rebellion, or certain strands of anarchism and autonomism reject hierarchical political structures and instead advocate for direct democracy and horizontal organizing.

Digital and Networked Disengagement: The rise of digital platforms has enabled both alternative political engagement and retreat into echo chambers or apolitical subcultures, reinforcing detachment from formal political discourse.

The rise of anti-political sentiment poses significant challenges for democratic governance. On one hand, it can be seen as a symptom of democratic decay—indicative of disillusionment with institutions meant to represent the public will. On the other hand, it can serve as a catalyst for democratic renewal by exposing systemic failures and demanding accountability.

Negative Impacts Include:

Erosion of Legitimacy: When large segments of the population disengage or reject political institutions, the legitimacy of those institutions weakens.

Governability Crisis: Widespread distrust may result in paralysis, as elected officials find it difficult to garner support or build coalitions.

Rise of Demagoguery: Anti-political environments can foster conditions conducive to the rise of charismatic leaders who promise to “drain the swamp” or bypass traditional institutions.

Civic Decline: A retreat from political life may weaken civil society, reduce social capital, and diminish collective problem-solving capacities.

Potentially Positive Outcomes:

Institutional Reform: Anti-political critique can spur political reform, transparency initiatives, and participatory mechanisms aimed at restoring trust.

Democratization from Below: Grassroots movements can rejuvenate democratic engagement through innovative forms of deliberation and participation.

Accountability Pressure: Public skepticism can pressure political elites to act more responsibly and maintain ethical standards.

Anti-politics is a global phenomenon, though its manifestations and causes vary widely across political systems:

Western Democracies: In mature democracies like the United States, the UK, and France, anti-politics often takes the form of declining voter turnout, growing independent voter blocs, and the success of anti-establishment parties (e.g., UKIP, the Tea Party, or France’s National Rally).

Post-Communist States: In countries like Russia, Poland, or Hungary, anti-political attitudes emerged following the collapse of communist regimes, often leading to nostalgia for strongman rule or disillusionment with liberal democratic transitions.

Global South: In many parts of Africa, Latin America, and South Asia, anti-politics intersects with histories of colonialism, authoritarianism, and elite dominance. Corruption, state violence, and exclusionary development contribute to profound distrust in political systems.

Authoritarian and Hybrid Regimes: In non-democratic contexts, anti-political sentiments may be suppressed or redirected through state propaganda. However, when expressed, they can fuel both revolutionary movements and political apathy.

Anti-politics is not only a political phenomenon but also a deeply social and psychological one:

Alienation: Drawing from Marxist theory, political alienation refers to the estrangement of individuals from political life due to perceived powerlessness, normlessness, or isolation.

Cognitive Overload and Political Complexity: In modern societies, the complexity of governance can lead to disempowerment, as citizens feel ill-equipped to understand or influence political processes.

Identity and Recognition: Political institutions may fail to recognize the identities, experiences, or cultural values of diverse groups, leading to a sense of exclusion and rejection of the system.

Generational Shifts: Younger generations often express higher levels of anti-political sentiment, sometimes due to disillusionment with economic prospects, environmental crises, or digital media cultures.

The study of anti-politics itself is not without critique. Some scholars argue that the concept is too vague or elastic, encompassing too many disparate phenomena. Others note that labeling dissent or alternative politics as “anti-political” may delegitimize genuine political engagement outside conventional institutions.

Moreover, some political theorists argue that anti-politics reflects a misunderstanding of the nature of politics as inherently conflictual and contested. From this view, efforts to transcend politics in favor of unity or purity (common in populist rhetoric) may mask authoritarian tendencies or suppress pluralism.

Anti-politics represents both a critique of and a challenge to contemporary political life. It embodies a wide spectrum of responses—from disengagement to insurgent mobilization—that reflect dissatisfaction with how political power is distributed, exercised, and justified. Understanding anti-politics requires an interdisciplinary approach that considers historical legacies, institutional performance, sociocultural dynamics, and the psychological dimensions of political life. While it can threaten democratic stability, anti-politics also offers a mirror for self-examination and the potential impetus for political innovation and reform.

#anti politics#political theory#populism#political disillusionment#systemic critique#government corruption#elite distrust#anarchist thought#neoliberalism#voter apathy#power structures#anti capitalism#alienation#protest culture#democratic crisis#institutions under fire#radical politics#politic sucks#revolutionary thought#modern politics#political corruption#grassroots movement#civil unrest#cynicism#resist the elite#critical theory#leftist tumblr#political aesthetic#collapse of trust#tumblr politics

0 notes

Text

List of phylosophies and ideological already described:

Cognitivism

Conservation Movement

Democratic Mundialization

German Historical School

Korean Phylosophy

Pre-Maxist Communism

Quantum Mysticism

Semi-Democracy

Social Populism

Wahdat-ul-Shuhud

Xueheng School

Anti-Politics

Universality

0 notes

Text

Xueheng School

The Xueheng School (学衡派), also known as the Critical Review Group, was a significant intellectual and cultural movement in early 20th-century China. Active primarily in the 1920s and 1930s and centered around the publication Xueheng (Critical Review), this school played a prominent role in the debates surrounding cultural modernization, Confucian revival, and the confrontation between Chinese tradition and Westernization during the Republican period. The Xueheng School was rooted in traditional Confucian thought but was also influenced by Western philosophical and scholarly methods, aiming to synthesize the best of both civilizations. It stood as one of the key conservative counter-currents to the radical modernist and anti-traditionalist tendencies of the New Culture Movement.

The Xueheng School emerged in the aftermath of the May Fourth Movement (1919), a broad intellectual, cultural, and political campaign that sought to reject Confucianism, feudal values, and traditional Chinese culture in favor of science, democracy, and Western modernity. Many leading intellectuals of the time, including Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi, and Lu Xun, advocated wholesale Westernization and the abandonment of what they viewed as outdated Confucian norms.

The Xueheng School arose in response to these trends, arguing that Chinese tradition, particularly Confucianism, held enduring value and should not be discarded. Its formation was also facilitated by the return of a group of Chinese scholars from the United States, many of whom had studied at Columbia University under the guidance of the American philosopher John Dewey, although they would ultimately diverge sharply from Dewey’s pragmatism. This group included leading figures like Mei Guangdi (梅光迪), Wu Mi (吴宓), Liu Boming (刘伯明), and others, who formed the intellectual nucleus of the Xueheng movement.

The school took its name from its journal, Xueheng, which was launched in 1922 at National Southeastern University (later renamed National Central University, now part of Nanjing University). The term xueheng can be translated as “weighing scholarship” or “measuring learning,” reflecting the journal’s commitment to critical and balanced academic inquiry.

Xueheng served as the platform through which the school disseminated its ideas. Over its many issues, the journal featured essays, reviews, translations, and polemical writings that engaged with a wide range of subjects, including philosophy, literature, ethics, history, education, and cultural critique. The editors sought to counteract the extreme iconoclasm of New Culture thinkers by defending the intellectual merits of Chinese classical civilization.

At the heart of the Xueheng School’s philosophy was a deep reverence for Confucian values, seen not as relics of a feudal past but as the foundation of Chinese civilization and moral order. The School emphasized the spiritual and ethical dimensions of Confucianism, particularly the ideas of ren (benevolence), li (ritual propriety), and zhongyong (the doctrine of the mean). They argued that these principles could and should form the basis for modern Chinese identity and social reform.

Unlike the more dogmatic revivalist movements, the Xueheng School did not propose a simple return to the past. Rather, it advocated a selective and critical synthesis of Chinese tradition and Western modernity. The members believed that Western science and technology could be adopted without dismantling the ethical and philosophical foundations of Chinese culture. This approach marked them as cultural conservatives, but not reactionaries; they sought to modernize without Westernizing.

Another defining trait of the Xueheng School was its commitment to scholarship and philology. Many of its members were trained in classical studies and applied rigorous methodologies in their examination of Chinese texts, history, and thought. This scholarly rigor stood in contrast to the rhetorical radicalism of their ideological opponents. The School thus often stressed academic integrity, textual criticism, and the importance of a liberal arts education grounded in classical learning.

Wu Mi (吴宓) is often considered the most emblematic figure of the Xueheng School. A deeply traditional scholar who had studied abroad, Wu was both a poet and a professor of literature. He was committed to the preservation of classical Chinese education and the humanities, and he was a vocal critic of the excessive utilitarianism and scientism he saw in New Culture intellectuals.

Mei Guangdi (梅光迪), another central figure, was trained in English literature and advocated for a refined literary culture rooted in both Chinese and Western classics. He worked to introduce Western literary criticism into Chinese scholarship but resisted the cultural relativism and moral nihilism he associated with some aspects of modern Western thought.

Liu Boming (刘伯明) was instrumental in promoting philosophical education in China. His writings frequently addressed issues of metaphysics, ethics, and pedagogy, reflecting his belief in the cultivation of moral character as the ultimate aim of education.

Other notable figures associated with the Xueheng School included Shen Zhongying (沈仲英), Hu Xianxiao (胡先骕), and Liang Shuming (梁漱溟), although the latter often diverged from core Xueheng positions and is more commonly associated with the Rural Reconstruction Movement.

The Xueheng School was deeply involved in intellectual polemics with the proponents of the New Culture Movement. One of their primary targets was Hu Shi, whose promotion of vernacular Chinese (baihua) and radical empiricism they saw as a threat to China’s cultural continuity. Wu Mi and others published a series of critiques arguing that abandoning classical Chinese would sever modern Chinese from its rich literary heritage and undermine linguistic precision and aesthetic expression.

The School also criticized Lu Xun and Chen Duxiu, particularly for what they viewed as nihilistic or destructive tendencies in their thought. The Xueheng scholars often argued that these reformers mistook the temporary failings of Chinese institutions for intrinsic flaws in Chinese culture itself.

These debates were not merely academic. They reflected profound ideological divides over China’s path to modernization—whether it should entail cultural self-affirmation or cultural self-negation. The Xueheng School provided a rare and articulate voice for the former view.

The influence of the Xueheng School waned by the mid-1930s as the political situation in China deteriorated and ideological struggles gave way to military conflict and national crisis. However, its legacy continued in several significant ways.

First, the School helped preserve classical studies and traditional Chinese thought during a time when they were under severe attack. Its members trained a generation of students who would carry on the study of Confucianism, Chinese literature, and history even in later decades.

Second, the Xueheng School’s ideas anticipated many of the cultural nationalist arguments that would become prominent in the mid-20th century, particularly during the war against Japan and in the post-1949 period among Chinese scholars abroad.

Third, in contemporary China, there has been a revival of interest in the Xueheng School, especially in academic and philosophical circles that seek to reassess the legacy of modernization and revalorize China’s own intellectual traditions. The journal Xueheng itself was revived in the 21st century under the auspices of Nanjing University, where it continues to publish scholarly work on Chinese philosophy, history, and culture.

The Xueheng School represents an important episode in the broader intellectual history of modern China. While it failed to dominate the mainstream narrative of the 20th century, which was heavily shaped by revolutionary ideologies and rapid Westernization, its influence persists in the long-standing debate between tradition and modernity, as well as in current efforts to articulate a “Chinese path” to modernization that is rooted in native values.

Scholars today increasingly recognize the value of the Xueheng School’s nuanced and scholarly approach to cultural questions. Its insistence on critical engagement rather than blind reverence or rejection offers a model for cultural self-understanding that is relevant not only to China but to any civilization grappling with globalization and identity.

#xueheng school#学衡派#chinese philosophy#confucianism#chinese history#republican era china#modern chinese history#intellectual history#chinese literati#confucian revival#chinese culture#east asian philosophy#chinese traditional culture#may fourth movement#cultural conservatism#chinese scholar#classical chinese thought#chinese modernity#humanities in china#traditional vs modern#chinese academia#20th century china#republic of china era#sinology#chinese aesthetics#philosophy tumblr#literary criticism#cultural debate#chinese intellectual tradition#history of ideas

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Social Populism

Social populism is a political ideology and strategy that combines elements of populism with social justice-oriented policies. It is typically characterized by a rhetorical and programmatic commitment to the empowerment of the "common people"—particularly working-class and marginalized populations—through the expansion of welfare states, redistribution of wealth, and increased economic and political inclusion. Social populism is generally situated on the left or center-left of the political spectrum and distinguishes itself from right-wing or nationalist populism by its emphasis on egalitarianism, solidarity, and universal social rights. While it shares certain rhetorical and strategic features with other populist movements, social populism is fundamentally shaped by its focus on collective welfare, progressive taxation, and robust public services.

The ideological roots of social populism can be traced to a confluence of democratic socialism, labor activism, and agrarian populist traditions that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The agrarian populist movements in the United States (e.g., the People's Party of the 1890s) and similar movements in Latin America (e.g., the early phases of Peronism in Argentina) provided early examples of political mobilization against elite domination in defense of economically disadvantaged groups. However, these movements were often ideologically heterogeneous and included both left-leaning and conservative elements.

Social populism began to acquire more coherent ideological form in the mid-20th century, particularly during the post-World War II period, when Keynesian economics and the welfare state became dominant paradigms in Western democracies. The rise of mass parties representing labor interests—such as the British Labour Party, the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), and Scandinavian Social Democratic parties—helped institutionalize social populist principles in governance. These parties promoted policies like universal healthcare, free education, pension systems, public housing, and strong labor rights, often coupling these with anti-elitist critiques of traditional ruling classes and economic oligarchies.

In Latin America, social populism took on a distinct trajectory, especially through charismatic leaders like Juan Perón in Argentina, Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, and later Hugo Chávez in Venezuela. These leaders combined leftist economic policies with nationalist and populist rhetoric, often bypassing traditional party systems and governing through direct appeals to the masses.

1. Anti-elitism and Popular Sovereignty

At the heart of social populism lies a fundamental distrust of economic and political elites, who are often portrayed as having subverted democratic institutions to serve their own interests. Social populist discourse emphasizes the idea of a morally virtuous and economically exploited "people" who must reclaim control over political and economic systems. This rhetoric is not merely symbolic; it is translated into policy proposals designed to redistribute power and resources from elites to the broader population.

2. Social Justice and Redistribution

Unlike right-wing populism, which may focus on nativism or cultural grievances, social populism emphasizes economic inequality as a central societal ill. It advocates progressive taxation, wealth redistribution, and public investment in social services as mechanisms to correct historical and structural injustices. Policy tools commonly endorsed by social populist movements include minimum wage laws, universal basic income, rent controls, and labor union empowerment.

3. Public Provision and Welfare Statism

A defining feature of social populism is its commitment to state-led solutions for social problems. This often manifests in strong advocacy for publicly funded education, healthcare, childcare, and pensions. Social populists typically oppose privatization of public services and view the welfare state as a means to achieve both social cohesion and economic stability.

4. Participatory Democracy

While social populism sometimes involves the personalization of power in charismatic leaders, many of its proponents emphasize participatory forms of governance. These may include referenda, participatory budgeting, grassroots assemblies, and the decentralization of decision-making processes. The goal is to reduce the distance between citizens and the state, thereby enhancing democratic legitimacy.

5. Internationalism and Solidarity

Though not universal, many social populist movements embrace a form of progressive internationalism, advocating solidarity with oppressed peoples globally and criticizing neoliberal institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. However, there is variation in how social populism interacts with globalization: some variants are staunchly protectionist, while others support open borders coupled with international labor standards.

The distinction between social populism and other populist ideologies is crucial. Right-wing populism, for example, also employs anti-elitist rhetoric but typically defines "the people" in ethnonationalist or culturally exclusive terms. It often scapegoats immigrants, minorities, or foreign institutions. In contrast, social populism defines the people along socio-economic lines, emphasizing class and economic marginalization rather than ethnicity or religion.

Moreover, social populism diverges from neoliberal centrism, which accepts market primacy and often favors technocratic governance over mass mobilization. While neoliberalism seeks to depoliticize economic decision-making, social populism re-politicizes the economy, framing issues like taxation, public investment, and corporate regulation as matters of democratic choice.

Social populism faces several institutional and structural challenges. Its reliance on strong state institutions for redistributive policy can be hindered by fiscal constraints, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and resistance from entrenched economic elites. In some cases, social populist governments have been criticized for undermining institutional checks and balances, particularly when charismatic leadership concentrates power and marginalizes dissent.

Moreover, critics argue that some variants of social populism risk lapsing into clientelism, where state resources are distributed in exchange for political loyalty. This danger is particularly acute in contexts with weak democratic institutions or high levels of corruption. Additionally, some observers question the long-term sustainability of expansive social spending, particularly in the absence of strong economic growth or diversified revenue sources.

In Latin America, social populism has been a recurring force since the mid-20th century. Classic examples include Peronism in Argentina, which combined state-led industrialization, labor union support, and charismatic leadership. In the 21st century, a new wave of left-wing populist governments—often referred to as the "Pink Tide"—emerged in countries like Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Leaders such as Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, and Rafael Correa promoted extensive social programs funded by commodity exports, reasserted state control over key industries, and framed their governance as participatory and anti-imperialist.

While these regimes achieved significant gains in poverty reduction and literacy, they were also criticized for democratic backsliding, erosion of press freedoms, and overdependence on resource rents. The collapse of oil prices in the mid-2010s exposed the vulnerabilities of these models.

In Europe, social populism has manifested more frequently through established parties adopting populist strategies. Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the UK Labour Party (2015–2020) is one example, marked by calls to nationalize public utilities, expand social services, and challenge the financial sector. Similarly, Spain’s Podemos and Frances La France Insoumise combine anti-austerity platforms with populist appeals to the working class and youth disillusioned with traditional parties.

However, these movements have had mixed electoral success and often face difficulties in coalition politics, especially in multi-party parliamentary systems. Institutional constraints imposed by the European Union, particularly fiscal rules and monetary policy, have also limited the scope of redistributive policies.

In the U.S., social populism has been represented by figures such as Bernie Sanders, whose campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination emphasized universal healthcare (Medicare for All), free college tuition, labor rights, and opposition to corporate influence. Although not successful in securing the nomination, Sanders’ campaigns shifted public discourse and policy agendas within the Democratic Party.

Social populism often intersects with broader social movements, including labor unions, feminist organizations, indigenous rights groups, and climate justice activists. In many cases, these movements provide the grassroots infrastructure and ideological content for social populist projects. However, tensions can arise when populist leaders centralize authority or when social movements demand more radical changes than political parties are willing to enact.

Economically, social populism draws on Keynesianism and, to a lesser extent, neo-Marxist and post-Keynesian theories. It challenges the orthodoxy of neoliberal economics, arguing that state intervention is necessary to correct market failures and ensure equitable distribution. Social populist policies may include:

Public sector job creation

Infrastructure investment

Universal basic services

Financial regulation

Debt forgiveness

Land reform (in agrarian contexts)

These measures are often justified both morally and pragmatically, as a means of stimulating aggregate demand, reducing inequality, and promoting social cohesion.

Social populism represents a significant current in global political development, offering a vision of democracy that is both participatory and economically inclusive. While it shares the populist emphasis on "the people" versus "the elite," it diverges sharply from authoritarian or exclusionary variants of populism by promoting egalitarianism, solidarity, and universal rights. Its impact is contingent on institutional capacity, economic conditions, and the ability to maintain both popular support and democratic integrity. As global inequality persists and disillusionment with neoliberalism grows, social populism is likely to remain a vital—if contested—element of 21st-century political life.

#social populism#left populism#populism#democratic socialism#social justice#political theory#leftist politics#economic justice#welfare state#class struggle#anti elitism#political ideologies#progressive politics#labor movement#workers rights#redistribution#universal healthcare#public services#we are the 99#inequality#power to the people#social democracy#participatory democracy#grassroots#solidarity#political education#keynesian economics#left wing politics#post neoliberalism#modern left

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cognitivism

Cognitivism is a broad and influential theoretical framework in psychology and education that emphasizes the importance of internal mental processes in understanding how individuals acquire, process, store, and retrieve information. Emerging in the mid-20th century as a reaction to behaviorism’s limitations, cognitivism places the mind at the center of the learning and psychological experience, asserting that observable behavior is only a small part of what constitutes human learning and thought. It encompasses a range of disciplines, including cognitive psychology, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, neuroscience, and educational theory.

Cognitivism rose to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s during what is often referred to as the cognitive revolution. This movement challenged the behaviorist orthodoxy that had dominated psychology for decades, particularly in the United States. Behaviorism, largely associated with figures like John B. Watson and B.F. Skinner, focused strictly on observable stimuli and responses, largely ignoring or minimizing the importance of unobservable mental phenomena.

The shift began with a growing recognition that behaviorist models could not adequately explain certain aspects of human learning, language acquisition, and decision-making. Influential works such as Noam Chomsky’s 1959 critique of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior argued persuasively that language acquisition was not solely a product of reinforcement but involved innate cognitive structures. Simultaneously, advances in computer science provided metaphors and tools for conceptualizing the mind as an information processor.

The intellectual roots of cognitivism can also be traced back to earlier thinkers such as Jean Piaget, whose developmental theory emphasized stages of cognitive development in children, and Immanuel Kant, who posited that knowledge arises from the interaction between innate mental faculties and sensory experience. However, it was not until the mid-20th century that a systematic and scientific approach to cognitive theory emerged, grounded in empirical research and formal modeling.

Cognitivism rests on several foundational assumptions:

Mental Representation: Cognitivists assert that the mind creates internal representations of the external world. These mental models allow individuals to manipulate, interpret, and respond to their environment in flexible and adaptive ways.

Information Processing: The cognitive approach views the human mind as an information processor, analogous to a computer. Learning and thinking involve the encoding, storage, retrieval, and manipulation of information. This paradigm includes stages such as sensory input, short-term (working) memory, long-term memory, and output responses.

Active Construction of Knowledge: Learners are not passive recipients of stimuli; they actively construct knowledge based on their prior understanding and experiences. This idea contrasts with behaviorist notions of learning as a simple response to reinforcement.

Cognitive Load and Capacity: Cognitivism recognizes that human cognitive resources—particularly working memory—are limited. Instructional design and learning strategies must therefore take into account cognitive load theory to optimize the learning process.

Schema Theory: A schema is a cognitive structure that organizes knowledge and guides information processing. Schemas help learners assimilate new information and accommodate it into existing knowledge structures, a process central to understanding complex phenomena and problem-solving.

Cognitivism is supported and enriched by a diverse group of theorists who have contributed significantly to the understanding of mental processes.

Jean Piaget: Although often associated with constructivism, Piaget's work laid the groundwork for cognitivist thought through his theory of cognitive development, which proposed that children move through distinct stages (sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational) as their thinking matures.

Jerome Bruner: Bruner emphasized the importance of categorization in learning and introduced the concept of the spiral curriculum. He argued that any subject could be taught effectively at any stage of development if properly structured.

Ulric Neisser: Often referred to as the "father of cognitive psychology," Neisser's 1967 book Cognitive Psychology helped formalize the field. He emphasized the importance of studying how information is acquired, transformed, stored, and used.

George A. Miller: A pioneer in cognitive science, Miller introduced the concept of “chunking” in memory and proposed that the capacity of working memory is limited to about seven items, plus or minus two. His work linked psychological theory to computer science and linguistics.

David Ausubel: Known for his theory of meaningful learning, Ausubel introduced the idea of advance organizers—cognitive tools that help integrate new information with existing knowledge.

Robert Gagné: His "Conditions of Learning" theory outlined nine instructional events that correspond to cognitive processes involved in learning. He emphasized the importance of structured instructional design.

John Sweller: Creator of cognitive load theory, Sweller demonstrated how excessive cognitive demands can impair learning and provided strategies for minimizing extraneous load during instruction.

Cognitivism encompasses a variety of interrelated mental processes that are critical to learning and behavior:

Perception: The process by which individuals interpret sensory input to form a coherent picture of the environment. Cognitivism studies how perceptual processes interact with attention and prior knowledge.

Attention: Cognitivists explore how attention is directed, maintained, and shifted. Attention is seen as a limited resource and a prerequisite for encoding information into memory.

Memory: Memory is central to cognitive theory. The multistore model of memory (Atkinson and Shiffrin) distinguishes between sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Cognitive theories also explore the mechanisms of forgetting, encoding specificity, and retrieval cues.

Language and Thought: Cognitivists study how language is processed and how it relates to thought, exploring phenomena such as language comprehension, production, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

Problem Solving and Reasoning: This involves understanding how individuals identify problems, generate solutions, and make decisions. Studies often focus on heuristics, biases (as per Kahneman and Tversky), and logical inference.

Metacognition: Metacognition refers to "thinking about thinking." It includes awareness of one’s own cognitive processes and strategies for regulating them, such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating one’s own learning.

Cognitivist theories have had profound implications for instructional design and pedagogy. Unlike behaviorist approaches that emphasize rote learning and reinforcement, cognitivist strategies promote deep understanding and knowledge transfer.

Instructional Design: Based on Gagné’s conditions of learning and Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning, effective instruction must align with the way the brain processes information. Instructional materials are designed to reduce extraneous cognitive load and enhance germane load, facilitating schema construction.

Scaffolding: Derived from Bruner’s work, scaffolding involves providing temporary support to learners until they are capable of performing tasks independently. This aligns with the cognitivist view of learning as a process of building internal cognitive structures.

Advance Organizers: Ausubel's concept emphasizes presenting learners with high-level overviews or frameworks before introducing new content. This primes existing schemas and enhances meaningful learning.

Active Learning and Concept Mapping: Cognitivist approaches encourage the use of concept maps, analogies, and real-world examples to foster meaningful connections between new and existing knowledge.

Formative Assessment: Cognitivism supports the use of frequent, diagnostic assessments that inform instruction and help students regulate their learning through feedback and reflection.

Despite its wide influence, cognitivism has faced several criticisms:

Underemphasis on Emotion and Motivation: Critics argue that traditional cognitivist models often neglect the role of affective factors such as emotions, motivation, and social context, which are crucial for understanding learning and behavior.

Reductionism: Cognitivism has been criticized for its tendency to reduce complex mental processes to mechanistic models, sometimes overlooking the richness of human experience.

Overreliance on Computer Metaphors: The analogy between the mind and a computer has been useful but limited. Critics point out that human cognition involves consciousness, intentionality, and biological embodiment, which do not have clear parallels in artificial systems.

Neglect of Cultural and Social Factors: While some cognitive theorists have addressed the role of context, many traditional models focus predominantly on individual cognition, ignoring the social and cultural dimensions emphasized in sociocultural theories of learning (e.g., Vygotsky).

In recent decades, cognitivism has increasingly been integrated with other theoretical frameworks:

Constructivism: While distinct, cognitivism and constructivism share several principles, including the emphasis on active learning. Constructivists build on cognitivist foundations by focusing more explicitly on the learner’s construction of meaning through social interaction and authentic experiences.

Social Cognitive Theory: Albert Bandura’s work bridges cognitive and behavioral theories by introducing concepts such as observational learning, self-efficacy, and reciprocal determinism, emphasizing that cognition, behavior, and environment interact dynamically.

Embodied Cognition: This newer perspective challenges classical cognitivist views by arguing that cognition is grounded in the body’s interactions with the world. It suggests that sensorimotor systems are integral to mental processes.

Cognitivism has deeply influenced the interdisciplinary field of cognitive science, which integrates insights from psychology, computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, and philosophy to study the mind and intelligence. Research in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in symbolic AI, has drawn heavily on cognitivist assumptions, modeling reasoning, memory, and problem-solving with algorithms and rule-based systems.

In education technology, cognitive theories inform the design of intelligent tutoring systems, adaptive learning environments, and multimedia instructional tools. These systems use models of learner cognition to personalize content, track progress, and provide targeted feedback.

Cognitivism represents a foundational paradigm in psychology and education that continues to shape how we understand learning, thinking, and knowledge acquisition. By emphasizing the role of internal mental processes, it has provided rich theoretical models and practical strategies for enhancing human learning and performance. While not without limitations, cognitivism’s integration with other perspectives ensures its continued relevance and adaptability in a rapidly evolving intellectual landscape.

#cognitivism#cognitive psychology#philosophy of mind#philosophy#cognitive science#psychology#educational psychology#learning theories#cognitive theory#mind and behavior#cognitive development#jean piaget#noam chomsky#cognitive revolution#mental processes#constructivism#neuroscience#educational theory#theories of learning#information processing#cognitive load theory#schema theory#psychological theories#cognitive models#aiand cognition#cognitive philosophy#history of psychology#learning science#cognitive education#mind and learning

0 notes

Text

Semi-democracy

Semi-democracy, also known as a hybrid regime or partial democracy, is a form of government that incorporates both democratic and autocratic features. These regimes often conduct elections and allow for limited pluralism, yet fail to guarantee civil liberties, the rule of law, or meaningful political competition. The term "semi-democracy" is used in political science to describe political systems that sit between full democracies and authoritarian regimes, forming part of a spectrum rather than a dichotomy. The classification and study of semi-democracies play a critical role in comparative politics, as many modern states exhibit characteristics of this form of governance.

The concept of semi-democracy emerged prominently during the third wave of democratization (starting in the 1970s and continuing through the early 2000s), when numerous countries transitioned away from outright authoritarianism but did not fully consolidate democratic institutions. These transitions often led to unstable or incomplete democratic regimes, which scholars began to analyze under new terminologies, including "illiberal democracy," "electoral authoritarianism," and "competitive authoritarianism."

The disintegration of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War catalyzed the emergence of many regimes that initially appeared to democratize but later stagnated or reversed, providing a rich field for the study of semi-democratic regimes. These regimes diverged from liberal democratic norms while retaining some of their outer trappings, such as elections and legislatures.

Semi-democracies are defined by their combination of democratic and authoritarian traits. While there is variation among different theoretical models and frameworks, key characteristics of semi-democracies generally include:

Electoral Processes: Elections are held regularly and may appear competitive, but are often flawed due to systemic bias, manipulation, or the absence of fair electoral oversight. The electoral playing field is typically uneven, favoring incumbents or dominant parties through media control, legal manipulation, or administrative bias.

Civil Liberties and Political Rights: Citizens in semi-democracies often face restrictions on freedom of speech, press, assembly, and association. While some civil liberties may be formally protected, their application is inconsistent, and enforcement can be arbitrary or politicized.

Rule of Law: The judiciary may lack independence, and legal institutions may be subverted by the executive branch or ruling elites. Laws can be selectively enforced, particularly against opposition figures or dissenters.

Political Pluralism: Opposition parties are allowed to exist and participate in politics, but they often operate under severe constraints. Media access, campaign financing, and organizational freedom may be limited for opposition actors.

Accountability and Transparency: Mechanisms for holding officials accountable are typically weak. Corruption is common, and state institutions may be captured by elites or special interest groups.

Civil-Military Relations: In some semi-democracies, the military plays an influential political role, either overtly or behind the scenes. Civilian control of the armed forces is often incomplete or fragile.

Several prominent scholars and political science frameworks have developed typologies to classify and analyze semi-democracies. Among the most influential are:

Freedom House Index: This measures political rights and civil liberties, categorizing countries as "Free," "Partly Free," or "Not Free." Semi-democracies typically fall into the "Partly Free" category.

Polity IV Project: This ranks regimes on a scale from -10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated democracy). Scores between -5 and +5 often denote semi-democratic or hybrid regimes.

Levitsky and Way's "Competitive Authoritarianism": These regimes have formal democratic institutions but are substantively authoritarian. Elections occur, but the competition is not meaningful due to systematic abuses.

Andreas Schedler’s "Electoral Authoritarianism": Schedler emphasizes the role of electoral institutions in semi-democracies that maintain democratic façades without meeting substantive democratic standards.

These models serve to map the vast heterogeneity among semi-democracies and provide a more nuanced understanding of their structures.

Institutional arrangements in semi-democracies vary widely but typically include the following:

Presidential or Semi-Presidential Systems: Many semi-democracies have strong presidential systems where power is concentrated in the hands of the executive. Checks and balances are often weak, and executives may rule by decree or manipulate institutions.

Dominant Party Systems: A single party often dominates the political landscape, not necessarily through coercion alone, but through structural advantages that marginalize opposition.

Bicameral or Unicameral Legislatures: Legislatures exist and function but often lack real power or independence. Parliamentary debate may be controlled, and legislative oversight is usually weak.

Controlled Civil Society: NGOs, unions, and media organizations may be formally legal but are frequently subject to surveillance, regulation, or co-optation.

There are several factors that contribute to the emergence and persistence of semi-democracies:

Historical Legacies: Colonial rule, past authoritarian governance, and civil conflict can shape political institutions in ways that favor hybrid regimes.

Economic Conditions: In many semi-democracies, economic inequality and underdevelopment reduce the capacity for democratic consolidation. Rentier economies—those dependent on natural resource revenues—often support authoritarian practices.

Elite Bargaining and Pact-Making: Transitions to democracy are sometimes the result of elite negotiations that leave key power structures intact, thereby institutionalizing partial democracy.

International Influence: External actors such as donor countries, international organizations, and regional powers may either support or undermine democratization efforts, depending on geopolitical interests.

State Capacity and Institutional Weakness: Weak bureaucracies and the absence of rule of law can prevent the development of robust democratic institutions.

Semi-democracy has profound implications for governance, development, and social cohesion:

Governance Quality: Semi-democratic regimes often suffer from poor governance, corruption, and inefficiency. While better than fully autocratic regimes in some cases, they may underperform relative to full democracies.

Political Stability: These regimes can be prone to instability, either through gradual authoritarian backsliding or mass protest movements demanding fuller democratization.

Human Rights: Violations of human rights and repression of dissent are common in semi-democracies, though generally less severe than in fully authoritarian states.

Economic Development: The economic performance of semi-democracies varies widely. Some are able to sustain moderate growth, especially where institutions are partially functional, while others stagnate under kleptocratic or clientelist systems.

Public Trust and Legitimacy: Citizens may become disillusioned with political institutions due to perceived hypocrisy, lack of responsiveness, and corruption, leading to political apathy or radicalization.

In some cases, semi-democracy represents a transitory phase toward full democratization. In others, it marks a stage of stagnation or regression. The phenomenon of democratic backsliding—the gradual erosion of democratic norms, practices, and institutions—has become a prominent concern in the 21st century, particularly in countries once considered consolidated democracies.

Simultaneously, semi-democratic regimes often exhibit a surprising degree of authoritarian resilience, maintaining power through adaptive strategies such as digital surveillance, legal repression, and selective liberalization.

Examples of semi-democratic regimes vary in region, structure, and trajectory:

Russia (Post-1990s): Originally hailed as a democratizing state, it has increasingly consolidated power under a dominant leader, with significant constraints on opposition and media.

Turkey (Early 2000s–present): While maintaining elections and a multiparty system, the regime under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been criticized for suppressing dissent and eroding judicial independence.

Malaysia (pre-2018): Dominated by a single party (UMNO) for decades, Malaysia held regular elections, but the playing field was heavily skewed, and opposition faced legal and institutional hurdles.

Hungary and Poland (2010s–present): These EU member states have seen democratic institutions and press freedom erode significantly under elected governments, sparking concerns over democratic backsliding within consolidated democracies.

The concept of semi-democracy is not without controversy. Critics argue that the term may legitimize repressive practices by implying a degree of democratic validity. Others contend that hybrid regime typologies risk oversimplifying complex political realities or fail to capture the dynamic nature of political change. Nonetheless, the framework of semi-democracy remains a vital analytical tool for understanding the variegated nature of political regimes in the contemporary world.

Semi-democracy occupies a crucial space in the study of political regimes, reflecting the messy and non-linear reality of democratization. It underscores that democracy is not merely defined by elections but by the quality and inclusiveness of political processes, the robustness of institutions, and the protection of fundamental rights. As global political trends evolve, the concept of semi-democracy continues to provide valuable insights into the successes, failures, and ambiguities of democratic governance in the 21st century.

#semi democracy#political theory#hybrid regimes#democracy in crisis#authoritarianism#democratic backsliding#comparative politics#global politics#political science#civic freedom#political corruption#civil liberties#rule of law#electoral manipulation#political analysis#state power#post democracy#illiberal democracy#freedom and power#governance crisis#political education#modern dictatorship#critical thinking#political awareness#power structures#political repression#transitional democracy#political reform#democracy watch#regime change

0 notes

Text

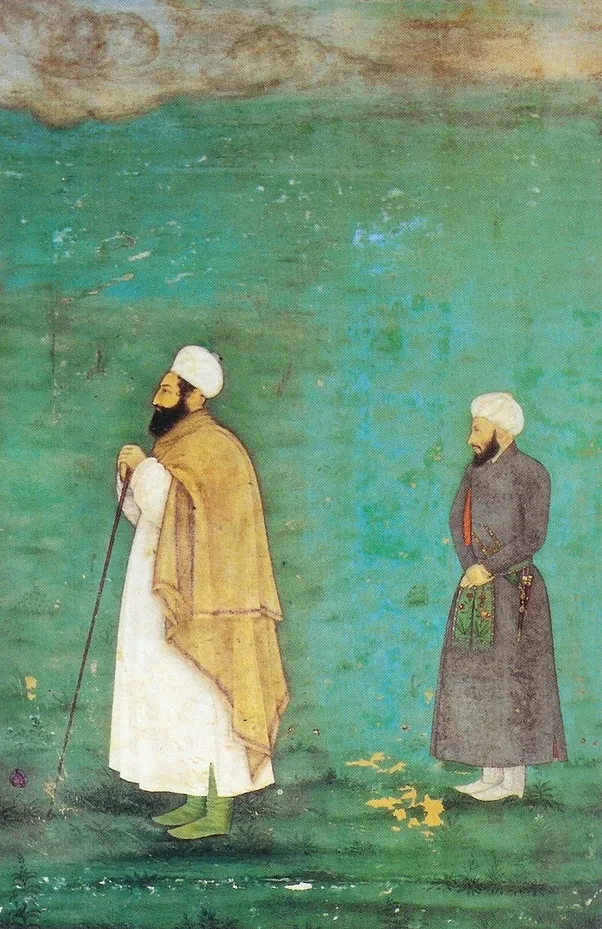

Wahdat-ul-Shuhud