I take photos, watch films, read books, and may or may not write stuff.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I'm Not A Robot

Earlier forms of media—such as books and radio—stirred our feelings through narratives while television introduced a visual closeness. Today, our technologies can respond to us. Applications, social networks, and interactive games react to our inputs, adjust to our needs, and even mimic emotions. The aim is not solely interaction; it’s about forming connections. Social media, for instance, entices us to linger for the dopamine hit. Video games provide stakes and characters we become invested in. Furthermore, gadgets are increasingly designed to evoke a sense of humanity. Consider AI companions, virtual pets, or even sex robots. This emotional design is not just for show; it’s a calculated approach. We form attachments. We come back. We rely on them.

As we embrace emotional connections with technology, we must consider our sacrifices in the process. When machines are crafted to imitate human interaction, they evade the complicated, genuine effort required in relationships. They are more straightforward, agreeable, and consistently accessible. Essentially, they are simpler to care for. Consider sex robots, for instance. They are frequently compared to sex work—but devoid of the human element. The interaction turns into a transaction, simplified to foreseeable input and output. While some suggest this allows for safe, guilt-free exploration, others caution that it fosters emotional disengagement from actual human partners. If a robot always responds with “yes,” how does that affect our expectations in human relationships? It can be argued that this proves our human desire for control, but also the conformist society we live in: we want easy access to information, easy access to people, easy access to emotions…when and however we want to.

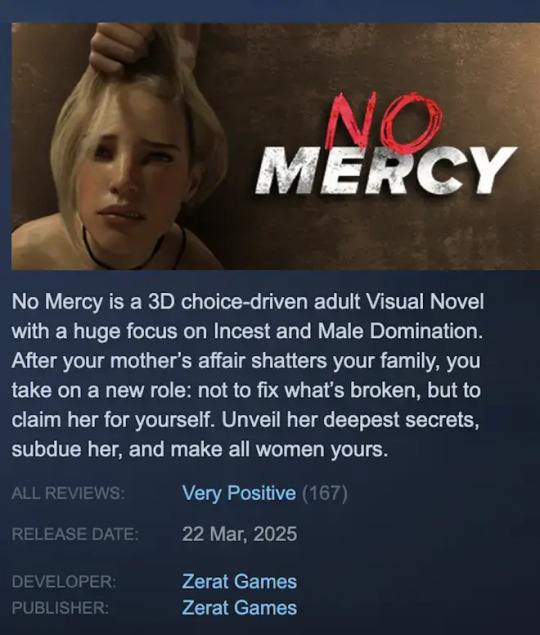

Contrary to popular belief, writer Meghan Murphy insists that sex dolls/robots are not merely a response to male loneliness but rather a reaction against increasing female independence, but can one type of technology encourage this behaviour? When the computer game ‘No Mercy’ came out on the PC gaming platform Steam in March of this year, it didn’t take long to have it permanently removed. Praising itself as an “incest and non-consensual sex” simulator, ‘No Mercy’ seems to portray women as punchbags, as sex objects, as something men can easily “make theirs” (game description from Steam shown below).

Interactive games described as ‘choice driven’ indicate that the player has the free will to make right or wrong actions – but is a game just a game, or does it unveil something worse? The developers, Zerat Games, seem to think the first one. In their public statement released on Steam’s forum, features such as incest and non-consensual sex (the main contents of the game) are concealed as kinks: “If we want to criticize someone for enjoying watching such portrayals, I believe we're intruding too deeply into their sexual sphere”. But would it be an intrusion if a parent wants to know what their kid is playing? After all, the game had no age range and Steam users can create their own accounts starting at 13 years old. As opposed to sex dolls and like most PC games, ‘No Mercy’ has a storyline to follow where the woman struggles and the man has the mission (common term used in games) to “become every woman’s worst nightmare” and “never take no for an answer” (Luck, 2025). The latter echoes men’s interactions with ‘affective’ technologies such as sex dolls and proves how when these devices are designed for men and (mostly) by men, they don’t have to make an effort – anything they want can be handled to them. The game can be interpreted as a response to female independence by celebrating male supremacy and portraying women—especially maternal figures—as subjects of manipulation and mistreatment. Its content diminishes female agency. By showcasing these dynamics in an interactive medium, the game trivializes gender-based violence and mirrors a wider cultural reaction against advancements in women’s rights.

People crave control. Seeing how the world is currently upside down politically, economically and socially, there has to be at least one thing that we can put our hands on and bring us joy. But affective technologies shouldn’t even be called affective if the feeling isn't mutual, and how can it be when one does it out of necessity and the other one doesn't do anything at all? Ultimately, while these affecting technologies promise connection, they often serve as tools of control—especially in a culture still reckoning with female independence and where the ‘male loneliness epidemic’ is on the rise. It's important to ask ourselves how we are building relationships, instead of just perfecting new ways to avoid them.

References

Baldanza, J. (2019). Pay to Play. Real Life. Available from https://reallifemag.com/pay-to-play/ [Accessed 13 February 2025].

Luck, F. (2025). Video game encouraging rape and incest removed from major gaming platform in the UK after LBC investigation. LBC. Available from https://www.lbc.co.uk/tech/video-game-banned-steam-women-uk-no-mercy/ [Accessed 13 April 2025].

Murphy, M. (2017). Sex robots epitomize patriarchy and offer men a solution to the threat of female independence. Feminist Current. Available from https://www.feministcurrent.com/2017/04/27/sex-robots-epitomize-patriarchy-offer-men-solution-threat-female-independence/ [Accessed 12 April 2025].

Zerat Games. (2025). Community Statement: Important News About No Mercy. Steam. Available from https://steamcommunity.com/games/3299570/announcements/detail/588390482275467288 [Accessed 13 April 2025].

0 notes

Text

YouTube and TikTok expose Gen Z and younger Millennials to thousands of strangers ‘embarrassing’ themselves through online challenges and witty homemade videos with friends and family. This content discloses the users’ lives making them visible to the public, but despite this still happening in 2025, there’s a shift into how much young online users share. The counterculture of anonymity within Gen Z particularly, regardless of it being predominant or not, addresses a new way of success and authenticity that simultaneously values privacy and security.

Influencers earn twice as much as others for simply showing their faces and personalities; it’s clear how fame comes as quick as it goes especially when they say or do the wrong thing. Therefore, anonymity is a tool to reclaim authenticity, and for creatives in particular, it helps them focus on their craft. Gen Z seem to be somehow more precarious before they post (or when they’re being posted), hence their poses in pictures such as ‘covering the nose’ and side-profiles. But does anonymity guarantee accountability? To what extent can anonymity be harmful to users online?

In her essay ‘The Personal Brand is Dead’, Kaitlyn Tiffany claims that Gen Z finds it normal to be “confusing and inscrutable” online (2022), demonstrating how this age group values mystery, but also the importance of being understood by the right people. Therefore, “Social steganography” helps to evade being understood by the wrong crowd: they put references and inside jokes in profile bios, professional networks, or even fandoms– all meant to be understood by certain recipients. This establishes distinct accounts for a select inner circle while also engaging the general audience, contributing to an air of mystique, similar to making your account private.

People can use their social media as they please; they can choose whether to show their faces, bodies and personalities. However, those who don’t, often rely on anonymity for other (not so positive) pursuits. Anonymity is a veil that conceals one’s identity; what they do once they’re under the shade is what draws the line between authenticity and accountability. It’s easy to post something online that might be harmful or offensive to other communities, but when there’s no face or name to put on someone, there are no repercussions to this individual. Could it be possible that these users aren’t afraid of anonymity anymore? People like Andrew Tate and the “alpha-male podcast bros” that come after him are clear on their beliefs, which raises the question of how their authenticity associates with their identity and if that’s all that constitutes it. The latter idea can be concerning given their views of women and masculinity. Then the algorithm happens and their platforms reach others, pushing their content thus continuing the cycle that surrounds the concept of authenticity.

Having discussed the downsides of some podcasts (or the podcasters), this digital audio programme gives producers the freedom to talk about anything they want, however they want to and show a side of them they perhaps had been wanting to show. It’s a new level of authenticity where journalists can add background music to make their news sound more dramatic, or friends can gather around and talk about their failed love lives and laugh about it. It proves that in order to be authentic, you don’t necessarily have to show your face. There’s a sense of anonymity behind this that causes no harm to others.

However, before social media took over the internet, a way to access people’s lives was through blogs with content that ranged from recipes, to trips abroad. The comeback of blogs through platforms such as Substack and WordPress in 2025 may indicate how people are more confident in sharing information they’re familiar with. What makes this more interesting is how users can also choose to remain anonymous or to publish their writing with their real names. Perhaps people are willing to take accountability of their personal expressions online and, because blogs allow comments from the public, they accept them without necessarily engaging in heated discourses that are easier to make on social media. After all, it’s just them wording their thoughts and the way they show them is a way to express their authenticity.

Digital platforms shaped how we present ourselves online, but raised tension between presenting an authentic self versus curated personas. Algorithms push us toward certain types of content, which make us question how much control we have over our online identities. But not everything is lost; younger generations have shown there are ways to be authentic and have control over what to reveal whilst keeping private, bringing with them emerging technologies and trends that are changing the future of storytelling and personal expression online. It’s just a matter of finding the balance in what to show and how.

References

Casawi Fashion (2024). The Rise of Anonymity: Redefining Success in the Digital Age. Casawi Magazine. Available from https://www.casawi.eu/post/the-rise-of-anonymity-redefining-success-in-the-digital-age [Accessed 09 April 2025].

Das Mahapatra, Tuhin. (2024). Why are Gen Z teens doing the 'nose cover' pose in family photos? Privacy or pose? Hindustan Times. Available from https://www.hindustantimes.com/trending/why-are-gen-z-teens-doing-the-nose-cover-pose-in-family-photos-privacy-or-pose-101705110022863.html [Accessed: 09 April 2025].

Nicholson, M. (2024). The Role of Podcasts in Modern Storytelling. Adriana Lacy Consulting. Available from https://blog.adrianalacyconsulting.com/the-role-of-podcasts-in-modern-storytelling/ [Accessed 08 April 2025].

Stamm, E. (2022). Who Can It Be Now. Real Life Magazine. Available from https://reallifemag.com/who-can-it-be-now/ [Accessed 14 February 2025].

Tiffany, K. (2022). The Personal Brand is Dead. The Atlantic. Available from https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/06/gen-z-internet-anonymity-instagram-tumblr/661316/ [Accessed: 01 March 2025].

*Banner image: Spirited Away, Hayao Miyazaki, 2001. Available from https://www.cbr.com/no-face-spirited-away-explained/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Throughout the colonial era, settlers narrated their mission in terms of restoration: turning “worthless wilderness” into something commodifiable and profitable. This “worthless wilderness” they talk about is nothing else than nature, home to flora and fauna that was back then defined by negative connotations related to emptiness and desolation. Centuries later, in 1964 when the U.S Congress passed the Wilderness Act, this term was defined as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain”. And even before that, escaping to the wilderness was praised for its health benefits, which can be evidenced in literary compositions such as Louisa May Alcott’s ‘Little Women’, where Jo March takes her sister Beth to the seaside as her health worsens due to scarlet fever (1868). Having established that, the concept of wilderness changed over the years and with the rise of technology, wilderness enmeshes the “online” and “offline” world.

Before the internet, the idea of escaping to the wilderness (or taking time off in nature) was seen as a way to reconnect with a “purer” or more “authentic” self. People believed that being away from modern life, away from societal pressures allowed for a clearer, more “real” connection to themselves and the natural world. In this sense, nature was the antidote to the distractions and disconnection of city life or industrial society. Here, the term ‘escape’ is important; it emphasises the need of this disconnection. But if we fast forward years later, with the emergence of newer technologies, more apps to download, easier access to world news and constant interaction with other users, the concept of digital detox became a modern version of that escape.

Instead of disconnecting from culture or society at large, digital detox focuses on technology—more specifically, our relationship with the internet and digital tools. People see the constant connectivity, social media, and screens as the main source of disconnection from themselves, their deeper thoughts, or their surroundings. So, to "reclaim" authenticity, many turn to digital detoxes as a way of stepping away from the overwhelming presence of technology.The digital detox trend assumes that we’ve become too "disconnected" from our true selves through overuse of technology, and that stepping away from it—whether by going offline or retreating to nature—is a way to reestablish a connection with something more genuine or real. The idea is that by escaping the “noise” of digital life, we can reconnect with a more “authentic” experience of living. A more specific example is found on social media such as X/Twitter, where interactions between fans of the same artist rely on the phrase “go touch some grass!”, once a member of the fandom starts acting out of line such as engaging in arguments, displaying excessive negativity or even showing overly delusional behaviours (examples seen below). As seen from the expression, ‘grass’ is therefore interpreted as the ‘wilderness’ discussed previously. The expression is a lighthearted humorous way of advising someone to take a break from their online activities.

On the other hand, we use these technologies to stay updated on the latest news and trends, factors that can help us shape our own opinions and therefore our personalities, creating a sense of self, an identity. But what happens when one does a permanent digital detox and has no access to information? Can a full digital detox be possible without becoming ignorant? The idea that we’re disconnected from our “true selves” just because we engage with technology can be flawed. Authenticity doesn’t have to be bound to being offline or in nature. You can be authentically engaged with technology, just as you can be authentically engaged in the wilderness. The key is how we engage, not where we are.

In other words, it’s not about where we are—online or offline—but how we engage with these spaces. A digital detox, in this view, becomes less about recovering our “authentic selves” and more about taking a break from overstimulation or tech-driven burnout, rather than a blanket cure for inauthenticity or lack of identity.

So the connection between authenticity and digital detox, when viewed through this lens, might be more about understanding balance. Digital detoxes can help us find space for reflection and peace away from the digital noise, but that doesn’t mean the internet or technology itself is inherently “inauthentic.” It's all about how we relate to it. Technology itself can be a tool for authenticity if we use it in ways that enhance, rather than detract, from our self-awareness and connection to the world around us.

References

Later. (no date). Touch Grass. Social Media Glossary. Available from https://later.com/social-media-glossary/touch-grass/#:~:text=Touch%20Grass%20is%20a%20figurative,nature%20or%20getting%20fresh%20air [Accessed 01 April 2025].

The Wilderness Act 1964, section 2.

Collee, L. (2021). The Great Offline. Real Life. Available from https://reallifemag.com/the-great-offline/ [Accessed 07 February 2025].

Tinysey (2025). The New Social Currency is…Being Offline? | Digital Detox Core. YouTube. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cexsiAzgCU [Accessed 05 April 2025].

0 notes

Text

April 24th, 2023

"Oh, how I love being a woman!"

Inspired by the works of Lirika Matoshi.

#photography portfolio#photography#womenswear#vintage#dreamy#zine#cottagecore#cottage aesthetic#lirika matoshi#fashion photography

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🖼 Jeune femme à sa toilette Vanité (c. 1630-1635) 👨🏻🎨 Nicolas Régnier 🎨 Oil on canvas

An old Uni project for my friend. Check the link to see what we tried to recreate, adding our own touch.

0 notes

Text

January 8th, 2021

I spent most, if not the entire of the pandemic, back in my home country, whose regulations were stricter than here in the UK; and yet where I felt the safest. I didn't understand why back in the day, doctors would recommend going to the seaside when feeling sick. Now I do.

This was on one of my first outings with my family, and I felt the need to capture the moment. We saw how COVID separated so many families, so it was reasonable, at least for us, to keep wearing masks. That was also the last time I was home until 2 years later, the longest time I had been away from the people I love the most.

1 note

·

View note

Text

January 26th, 2020

First post on my new blog!

2 notes

·

View notes