Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Navigating the Digital Wild West: Are We Really Snowflakes?

We're all living more and more of our lives online, yet sometimes it feels less like a friendly neighborhood and more like a battleground. Lately, there's been this catchy but kinda insulting label thrown around: the 'snowflake generation' (Haslop et al., 2021, p.1418). The idea is that young folks, especially students, are too delicate and get offended by everything. But is that really the tea? 🤔

New research out of the University of Liverpool throws some serious shade on this 'snowflake' theory (Haslop et al., 2021, p.1418). Their study found that online harassment is so widespread among university students that many just see it as the 'norm' – something to be tolerated rather than challenged (Haslop et al., 2021, p.1424). Think about that for a second. Instead of being overly sensitive, could it be that we're actually becoming numb to online abuse?

This 'snowflake' narrative, pushed by some corners of the media and political sphere, might be intentionally diverting our attention from a much darker reality: the pervasive and damaging effects of online harassment, especially on those who identify as female and transgender (Haslop et al., 2021, p.1418). These are the folks who are disproportionately targeted, contributing to a gender-related digital divide that can silence voices and limit participation (Haslop et al., 2021, pp. 1427-1428). So, are we really snowflakes, or are we facing something much more systemic and serious in our digital world?

And let's dive into a darker corner of the internet: the manosphere. This is a network of blogs, podcasts, and forums that includes men's rights activists (MRAs) and anti-feminists (Marwick & Caplan, 2018, p.546). Researchers Marwick and Caplan highlight how these groups often use a shared language and narrative that portrays feminism as a movement that hates and victimizes men (Marwick & Caplan, 2018,p.544).

They focus on the term 'misandry' (hatred of men), arguing that within the manosphere, it's used to justify the networked harassment of feminists and anyone advocating for gender equality (Marwick & Caplan, 2018, p.550). By painting themselves as victims of 'misandry', they try to flip the script and silence those calling out actual inequality. It's a wild tactic, right?

Then, we saw the rise of #MeToo, a powerful wave of digital feminist activism (Reinicke, 2022, p.5). Social media became a vital space for survivors of sexual harassment to share their stories and find support (Pollino, 2021). Reinicke suggests that #MeToo has the potential to create real change in how we understand and address sexual harassment (Reinicke, 2022, p.4).

youtube

So, where do we go from here in this digital landscape? Here are some things to think about:

Should social media platforms be doing more to tackle harassment and moderate harmful content? What responsibilities do they have to us as users?

How can we push back against narratives that downplay online harassment, like the whole 'snowflake' thing?

What role can education play in helping us become better digital citizens and understand the real impact of our online words and actions?

How can men step up as better allies in challenging misogyny and online harassment? It's not just on women and marginalized folks to fix this!

What are your thoughts? What have you seen online? How can we make these digital spaces safer and more equitable for everyone? Share your stories!

References

Haslop, C., O’Rourke, F., & Southern, R. (2021). #NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1418–1438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856521989270

Marwick, A. E., & Caplan, R. (2018). Drinking male tears: language, the manosphere, and networked harassment. Feminist Media Studies, 18(4), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1450568

monstie69. (2024, July 7). Post by @monstie69 | 1 image. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/monstie69/755381274345193474/let-there-be-chaos

Pollino, M. A. (2021). Turning points from victim to survivor: an examination of sexual violence narratives. Feminist Media Studies, 23(5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2021.2006260

Reinicke, K. (2022). Introduction. Men after #MeToo, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96911-0_1

The #MeToo Movement. (n.d.). Www.youtube.com. Retrieved December 11, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KnGY2fiqHt0Vogels, E. (2021, January 13). The state of online harassment. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

#digital citizenship#online harassment#me too movement#social media#media#feminism#misandry#mda20009#digital communities#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Media Makes Gaming Seriously Social

I bet not all of us realize that gaming isn’t just about high scores and epic loot, it’s also about the people we meet along the way. Whether you’re building in Minecraft, hanging in a Discord server, or watching your favorite Twitch streamer, gaming today is as much about connection as it is about competition.

That’s right, we don’t just play games anymore, we experience them together. And media is the glue that ties it all together. From livestreams to fan forums, from modding communities to esports arenas, gaming has evolved into a social universe powered by media. So how is media transforming gaming into a seriously social experience?

Minecraft: Your Everywhere, Everyday Social Sandbox

Remember that feeling of building LEGOs with your friends for hours? Minecraft takes that to a whole new digital level! This game isn't just something you play; it becomes part of your day, your "ambient play," as Hjorth et al. (2020) describe. You can be on your iPad chilling in the living room, building a pixel art masterpiece while chatting with your buddies about it. It blurs the lines between the digital and real worlds, letting you connect through creativity no matter where you are (Hjorth et al., 2020, p.28)

And the community vibes? Next level! The "Autcraft" server is a powerful example of how Minecraft fosters incredibly supportive online spaces, especially for neurodiverse players (Hjorth et al., 2020, pp. 40-41). It creates alternative pathways for communication and sociality that can be truly transformative (Hjorth et al., 2020, pp. 40-41).

youtube

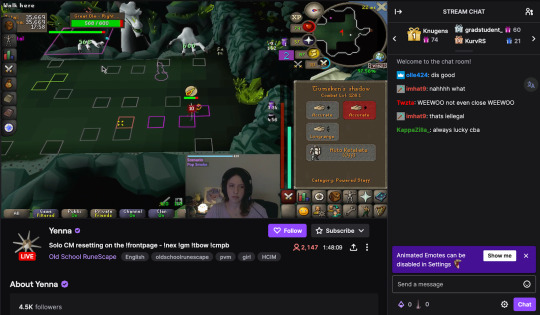

Twitch & YouTube: Your Backstage Pass to the Gaming World!

Want to see how the pros do it, or just hang out with someone while they explore a new indie game? Platforms like Twitch and YouTube have revolutionized how we experience gaming as a spectator sport and a social activity (Johnson & Woodcock, 2018, Streaming as game visibility and lifespan). Taylor calls Twitch "networked broadcasting," and it's so true! You're not just watching someone play; you're part of a live event with thousands of others in the chat, cheering, reacting, and forming a community around the streamer (Taylor, 2018, p.6).

Think about watching a massive esports tournament or a "variety" streamer playing their favorite games. The live chat transforms the experience into a shared social event (Taylor, 2018, p.6). Plus, these platforms have even created new kinds of "media work," where people can build audiences and even careers by sharing their gameplay and interacting with their viewers in real-time (Taylor, 2018, p.9).

Beyond the Big Names: The Diverse Indie Gaming Universe

Indie games have their own vibrant media ecosystem! Brendan Keogh's exploration of the Melbourne indie game scene highlights how many different "scenes" exist within the broader gaming world, each with its own values and focus (Keogh, 2020, pp. 209-211). Not everyone is chasing mainstream success; many are driven by artistic expression and community building (Keogh, 2020, p. 218). This diversity is reflected in the different ways they use media to connect with each other and potential players.

Media: The Threads That Tie It All Together 🧵

From the platforms we play on to the streaming services we watch, and the online communities we participate in, media is absolutely fundamental to the social fabric of gaming.

Different gaming platforms (consoles, mobile, PC) offer unique ways to play and socialize (Hjorth et al., 2020, p. 37).

Video sharing and live streaming platforms (YouTube, Twitch) have created massive communities around watching and interacting with gameplay (Hjorth et al., 2020, p. 32).

Online forums, social media, and dedicated communities (like Discord servers) provide spaces for discussion, knowledge sharing, and building friendships (Hjorth et al., 2020, p. 33).

Even in-game features and player-created content act as media for expression and connection (Hjorth et al., 2020, p. 33).

It's all interconnected. You might learn building tips from a YouTube video, try them out with friends in Minecraft, and then maybe even share your own creations online.

So what are your favorite ways to connect with others through gaming? What online communities feel like home? Share your experiences in the replies! Let's celebrate the awesome social side of play and the media that makes it all possible! 🎉

References

AutismFather. (2013, December 17). What is Autcraft. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dOWjbKo3sMc

Hjorth, L., Richardson, I., Davies, H., & Balmford, W. (2020). Exploring Play. Exploring Minecraft, 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59908-9_2

Johnson, M. R., & Woodcock, J. (2018). The impacts of live streaming and Twitch.tv on the video game industry. Media, Culture & Society, 41(5), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718818363

Keogh, B. (2020). The Melbourne indie game scenes. Routledge EBooks, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367336219-18

rebelpeas. (2024, September 12). Minecraft Builders • Community on Tumblr. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/communities/minecraft-builders

Taylor, T. L. (2018). Watch Me Play: Twitch and the rise of game live streaming. Princeton Oxford Princeton University Press.

Twitch. (2011). Twitch. Twitch. https://www.twitch.tv/

#mda20009#Game#gaming communities#communities#video games#minecraft#indie games#social#digital communities#Youtube

0 notes

Text

How Instagram is Shaping Beauty, Identity, and Data

Put a finger down if...

Put a finger down if you’ve ever spent the whole day editing your Instagram selfie. ✋ Put a finger down if you’ve tried ten different filters before settling on the "natural" one. ✋ Put a finger down if you’ve thought, Wow, I look so much better with this filter on… ✋

Yeah, same here.

Instagram filters have become a digital beauty standard, an unspoken rule of social media that says your face, as it is, just isn’t enough. But what if I told you that these "harmless" filters are actually shaping the way we see ourselves, reinforcing outdated beauty standards, and even training AI to recognize and rank our faces? (It actually sounds kinda scary)

Anyway, welcome to the world of digital citizenship and software literacy, where the filters we use are doing way more than just smoothing our skin.

What you're likely witnessing is the pervasive power of Instagram filters, a seemingly simple feature that belies a complex intersection of digital citizenship and software literacy (Barker, 2020, p.207). These aren't just whimsical overlays; they're shaping how we see ourselves, how we present ourselves, and even how machines interpret our very identities.

What's the Filter Actually Doing?

Filter refers to the tool that allows selfie takers to enhance their photos easily, without needing professional editing software (Hong et al., 2020, Excessive self-presentation). They can adjust colors, modify lighting, or add digital overlays like flower crowns, animal features, or bright, exaggerated eyes, all designed to make selfies more visually appealing (Hong et al., 2020, Excessive self-presentation). On the surface, engaging with Instagram filters is a prime example of software literacy. This means we're actively using an application that employs pre-programmed algorithms to manipulate our images (Rettberg, 2014, p.21). Jill Walker Rettberg, in "Filtered Reality," offers a broader perspective, defining a "filter" as a technological, cultural, or cognitive mechanism that removes, alters, or distorts content (Rettberg, 2014, p.22). Instagram filters embody this, going beyond mere aesthetics to potentially erase perceived "flaws" or impose a particular "style".

The Critical Angle: Unpacking the Algorithmic Influence

However, true digital citizenship demands we move beyond simply knowing how to apply a filter and instead critically analyze why we use them and what impact they have (Barker, 2020, p.209). Barker's research raises crucial questions about the "problematic nature of Snapchat’s beautifying filters," many of which share similar functionalities with Instagram filters (Barker, 2020, pp. 208-209). She highlights how these filters often promote narrow, exclusionary beauty standards by algorithms that slim jawlines and noses, enlarge eyes and lips, and smooth and lighten skin complexions (Barker, 2020, p.207). She also mentioned the term "digital adornment" - a way users experiment with creativity and self-expression in the digital realm, akin to using cosmetics or clothing (Barker, 2020, p.208). This can lead users, like Emily Arata, to question their natural appearance and feel that only the filtered version is presentable (Barker, 2020, p.208).

Rettberg’s concept of "Biometric Citizens" adds a crucial dimension to this analysis. She argues that our filtered selfies are not solely for human eyes but are increasingly processed as data by machines for purposes like facial recognition (Rettberg, 2017, p.89). Consider Instagram's augmented reality filters that overlay animal ears or virtual makeup; these rely on sophisticated facial detection technology, creating a biometric grid on our faces to ensure the digital elements move with us (Rettberg, 2017, p.93). As Rettberg points out in the context of Snapchat lenses, this normalizes the idea of our faces being constantly read by machines.

The connection between Barker's "digital adornment" and Rettberg's "biometric citizen" is striking. The very software that enables us to playfully alter our appearance for self-expression simultaneously turns our faces into a set of data points for algorithmic consumption (Barker, 2020, p.207). When we use an Instagram filter that subtly contours our face or brightens our eyes, we are not only engaging in a form of digital self-fashioning but also providing a specific dataset that aligns with certain beauty ideals that can be recognized and categorized by machine vision (Barker, 2020, p.209).

The problem of Instagram Filters

The Issue of Skin Tone: A particularly troubling aspect, highlighted by both Barker and Rettberg, is the tendency of some filters to lighten skin tones (Barker, 2020, p.214). This reinforces the "cultural biases" embedded in technology that assert lighter skin as more desirable (Barker, 2020, p.214). This demonstrates how seemingly innocuous software features can perpetuate harmful and racist beauty standards. Rettberg's discussion of the historical "skin tone bias in photography" further contextualizes this issue, showing how technological filters have long been calibrated for lighter skin, leading to the misrepresentation of people with darker complexions (Rettberg, 2014, p.28).

Gender Stereotypes in Filters: The problematic International Women's Day filters on Snapchat, as reported by Julia Carrie Wong, offer another critical example. The filter honoring Marie Curie, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist, applied "smoky eye makeup and lengthen[ed] the eye lashes" (Barker, 2020, p.213). This sparked outrage, with users questioning if "Marie Curie invent[ed] smokey eye then?" and highlighting the absurdity of sexualizing a renowned scientist with a beauty filter (Barker, 2020, p.213). This illustrates how software design can inadvertently reinforce outdated and harmful gender stereotypes (Barker, 2020, p.209).

Towards Responsible Digital Citizenship

Understanding the mechanics and implications of Instagram filters is crucial for responsible digital citizenship. We must critically evaluate the beauty standards promoted by filters by recognizing that these are often narrow, commercially driven, and can be racially biased. We must also be aware of the potential impact on self-esteem and body image, since constant exposure to filtered images, including our own, can contribute to dissatisfaction with our natural appearance.

References

Barker, J. (2020). Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of snapchat. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 7(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1386/fspc_00015_1

Hong, S., Jahng, M. R., Lee, N., & Wise, K. R. (2020). Do you filter who you are?: Excessive self-presentation, social cues, and user evaluations of Instagram selfies. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106159

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Filtered Reality. Seeing Ourselves through Technology, 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476661_2

Rettberg, J. W. (2017). Biometric Citizens: Adapting Our Selfies to Machine Vision. Springer EBooks, 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45270-8_10

softgothbabe. (2024, September 10). Post by @softgothbabe | 3 images. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/softgothbabe/761239788984713217/lovergirl-to-my-core

softpine. (2023, October 24). Post by @softpine | 3 images. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/softpine/732090617926238208/idk-man-im-not-one-of-those-people-who-thinks

#mda20009#digital communities#Digital Citizenship#filters#instagram filter#identity#beauty standards

0 notes

Text

🔥 Is Your Feed on Fire? The Hidden Algorithmic Sparks Behind Body Mod Visibility 🔥

We've all been there: scrolling through a feed filled with stunning tattoos, bold piercings, and jaw-dropping body modification. Yeah, it’s undoubtedly a visual feast showcasing human creativity and self-expression.

But the question is, why did this particular piercing went viral, or why that incredible tattoo artist seems to dominate your "explore" page? Prepare to have your perception tweaked, because there's more to online body mod visibility than meets the eye.

Carah and Dobson (2016) talked about "body heat" on social media. This term refers to certain hot female bodies that attract attention in the context of nightlife (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p.1). Similarly, in the realm of body modification, body heat means the images aligning with dominant, often "hetero-sexy" visual codes that might generate more algorithmic "heat" through increased likes, shares, and saves (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p.1). That’s right, instead of a neutral reflection of user interest, the algorithm learns to prioritize images aligning with what is already deemed "hot" (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p.1). This raises critical questions: Whose bodies and modifications are considered "hot" and therefore visible? And how does this algorithmic bias potentially silence or obscure body modifications that challenge these narrow standards? The initial virality of a post isn't solely based on artistic merit but is significantly influenced by its adherence to pre-existing, often exclusionary, aesthetic norms that the algorithm learns to favor (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p.1).

This algorithmic prioritization intertwines with Drenten, Gurrieri, and Tyler's analysis of "sexualized labour" in digital culture. They argue that many influencers, particularly women, engage in embodied performances, often adopting a "porn chic" aesthetic, to garner attention and potential monetization (Drenten et al., 2019, pp. 42-43). Showcasing body modifications can become intertwined with a "porn chic" aesthetic, utilizing specific poses, styling, and editing techniques to cater to certain ideals of attractiveness and capture valuable attention (Drenten et al., 2019, p.42). The "flawlessly filtered, perfectly posed shot" isn't just self-expression; it can be a calculated act of digital labour aimed at capturing the algorithm's attention and, by extension, a wider audience (Carah & Dobson, 2016, p.8). So, that seemingly effortless, artfully angled shot of a new tattoo? It could be part of a calculated digital performance aimed at maximizing visibility and potential monetization.

But here’s a crucial reality check, as highlighted by Duffy and Meisner's work on "platform governance at the margins": the digital playing field isn't level. Algorithms aren't neutral; they can exhibit biases, leading to uneven visibility (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.387). Creators from marginalized communities or those showcasing body modifications that deviate from mainstream norms often experience algorithmic visibility (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.285). This can manifest as content moderation or biased algorithmic boosts that inadvertently suppress "non-normative" expressions (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.285). That unique and boundary-pushing body art you were hoping to discover? It might be getting algorithmically sidelined, preventing it from reaching a wider audience.

Then, how do we navigate this algorithmically influenced landscape?

Well, be aware that what's popular isn't necessarily representative of the full spectrum of body modification artistry (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.300). You need to actively seek out diverse creators and styles that might not always dominate your main feed. Engaging with creators showcasing a wide range of body modifications, identities, and artistic approaches will be great as well. Your likes, shares, and thoughtful comments can help challenge algorithmic biases and boost marginalized voices (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.300). And understand that creating compelling content and navigating algorithmic pressures, potential biases, and content moderation can be demanding and often unpaid work for creators, especially those from marginalized communities (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.285). They might even resort to self-censorship or circumvention tactics to avoid algorithmic penalties (Duffy & Meisner, 2022, p.285).

References

bouncing-flowers. (2025, March 20). Post by @bouncing-flowers | 1 image. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/bouncing-flowers/778569490636111872/who-knew-humans-looked-so-tasty?source=share

Carah, N., & Dobson, A. (2016). Algorithmic hotness: Young women’s “promotion” and “reconnaissance” work via social media body images. Social Media + Society, 2(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116672885

Drenten, J., Gurrieri, L., & Tyler, M. (2019). Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12354

Duffy, B. E., & Meisner, C. (2022). Platform Governance at the margins: Social Media Creators’ Experiences with Algorithmic (in)visibility. Media, Culture & Society, 45(2), 016344372211119. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221111923

fangophilia Taro on Instagram: “Bangkok pop up shop till Dec.8th 12:00-19:00 At WWA Chooseless Thonglor soi 20, Ekkamai soi 21 #silverjewelry #silverjewellery #silveraccessory #earrings #nosejewelry #blacktattooart #blacktattoo #facetattoo #bodymods #bodymodification #bangkok #fangophilia.” (2021). Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/DDRhunfSSkx/

fanta30. (2024, January 3). Post by @fanta30 | 1 image. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/fanta30/738524319686311936

#Body Modification#Digital Citizenship#Social Media Algorithms#Platform Bias#Algorithmic Visibility#digital communities#mda20009

0 notes

Text

Beyond Trends: Why Slow Fashion Matters

Have you ever stopped to think about the journey of your clothes? Who made them? What impact did their production have on the planet? We're so used to cheap, trendy clothes being readily available, but is there a hidden cost? Let's explore the concept of slow fashion: a movement that challenges everything we think we know about style.

youtube

What is Slow Fashion? Slow fashion is a sustainable consumption movement that is the opposite of fast fashion (Chi et al., 2021, p.101). It involves a longer product life cycle, emphasizes quality, is often higher priced, and requires increased consciousness from producers and consumers (Pookulangara & Shephard, 2013).

In other words, instead of chasing fleeting trends, slow fashion is a conscious approach that values lasting quality by investing in well-made pieces designed to stand the test of time (Jung & Jin, 2014).

Fast Fashion's Dirty Secrets

Back to fast fashion, yes, it sure is tempting to snag that bargain outfit, but what's the real price we pay for fast fashion?

First, environmental destruction. The fashion industry is notoriously polluting, guzzling water, releasing toxic chemicals, and creating mountains of waste (Domingos et al., 2022, p.102). With trend cycles accelerating some brands release collections every few weeks, can we really afford to keep treating our planet like a disposable resource?

Second, worker exploitation. The Rana Plaza collapse in 2013, where over 1,000 people died, exposed the unsafe conditions and unfair labor practices prevalent in the fast fashion industry (Henninger et al., 2017, p.2). Is a cheap T-shirt worth someone's life?

And of course, the amount of waste. Fast fashion encourages a "wear-it-once" mentality, leading to massive amounts of textile waste in landfills (The Happy Turtle Straw, 2025). The U.S. EPA estimates that Americans toss out 16 million tons of textiles each year, recycling only 15% (Chi et al., 2021, p.102). Are we destined to drown in our own discarded clothes?

Making a Change

So, how can we participate in the slow fashion movement and be a more conscious consumer? - Buy Less, Choose Well: Focus on purchasing high-quality pieces that you love and will wear for years to come.

- Choose Classic Style: Opt for timeless designs that transcend fleeting trends. [Image of a capsule wardrobe with classic pieces]

- Shop Secondhand: Give pre-loved clothing a new life by shopping at thrift stores, vintage shops, and online consignment stores. [Image of people shopping in a thrift store]

- Support Ethical and Sustainable Brands: Look for brands that are transparent about their production practices and committed to fair labor and environmental responsibility. [Link to a directory of ethical fashion brands]

- Take Care of Your Clothes: Proper washing, storing, and repairing your clothes can significantly extend their lifespan.

While slow fashion offers a compelling alternative, it's not without its challenges. Some argue that "sustainability" remains a somewhat ambiguous concept (Henninger et al., 2017, pp. 3-4). Also, while consumers express interest in ethical and sustainable options, other factors, like style and price, influence buying decisions (Harris et al., 2016, Factors affecting sustainable clothing behaviour). Yet, consumers may be more inclined to purchase if they believe their slow fashion consumption behaviors can effectively contribute to environmental protection (Chi et al., 2021, p.109).

All in all, slow fashion is like a shift in mindset. Together, we can reduce the negative impacts of the fashion industry and cultivate a more conscious approach to consumption.

References:

The Happy Turtle Straw. (2025, January 27). Fashion’s Waste Problem: Fast Fashion’s Environmental Toll - The Happy Turtle Straw. The Happy Turtle Straw. https://www.thehappyturtlestraw.com/fashions-waste-problem-fast-fashions-environmental-toll/

Chi, T., Gerard, J., Yu, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021). A study of U.S. consumers’ intention to purchase slow fashion apparel: understanding the key determinants. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 14(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2021.1872714

Clean Clothes Campaign. (2024). Rana Plaza. Clean Clothes Campaign. https://cleanclothes.org/campaigns/past/rana-plaza

derinthescarletpescatarian. (2024, December 21). Post by @derinthescarletpescatarian. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/derinthescarletpescatarian/770462692320362496/im-so-pissed-right-now-i-know-that-fabric-has

Domingos, M., Vale, V. T., & Faria, S. (2022). Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: a Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(5), 2860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052860

Harris, F., Roby, H., & Dibb, S. (2016). Sustainable Clothing: Challenges, Barriers and Interventions for Encouraging More Sustainable Consumer Behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(3), 309–318.

Henninger, C. E., Alevizou, P. J., Goworek, H., & Ryding, D. (2017). Sustainability in Fashion : A Cradle to Upcycle Approach. Springer International Publishing.

herbaklava. (2024, July 7). Post by @herbaklava. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/herbaklava/755332789884289024/i-literally-hate-my-entire-wardrobe-except-for-a

Jung, S., & Jin, B. (2014). A theoretical investigation of slow fashion: sustainable future of the apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(5), 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12127

Pookulangara, S., & Shephard, A. (2013). Slow Fashion Movement: Understanding Consumer Perceptions—An Exploratory Study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 20(2), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.12.002

TED-Ed, & Chang, A. (2017). The life cycle of a t-shirt - Angel Chang. In YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BiSYoeqb_VY

Vito, F. (2022, July 27). What Is Slow Fashion and How Can You Join the Movement? Earth.org. https://earth.org/what-is-slow-fashion/

#fast fashion#slow fashion#fashion#sustainability#earth#environment#consumption#digital communities#communities#mda20009#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Digital Citizenship: It's Time to Get Radical

We always hear about digital citizenship, but let's be real, it's often taught in a super basic way that doesn't address the real issues of power, inequality, and justice online.

Beyond the Surface: A Critical Look at Digital Spaces

Digital citizenship is frequently presented through a unidimensional approach, focusing solely on online safety or ethical behavior (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.362). While these aspects are important, they don't fully address the complexities of the digital world. A multidimensional approach broadens the scope, considering digital ethics, media and information literacy, participation, and critical resistance (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.363). However, to truly understand digital citizenship, we need to adopt a critical and radical approach, acknowledging and challenging the unequal power dynamics and social inequities present online (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.362).

Intersectionality: Recognizing the Interlocking Systems of Oppression

Intersectionality is crucial for understanding how different forms of discrimination and inequality overlap and create unique experiences for individuals based on their social identity attributes such as gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and age (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.363). For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted racial and sexual minorities and economically vulnerable communities, highlighting existing systemic inequities (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.361). These inequalities are often amplified and reproduced in digital spaces, making it essential to address them through an intersectional lens (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.362).

Participatory Democracy: Claiming Our Digital Voice

Participatory democracy emphasizes the active involvement of citizens in shaping society (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.364). In the digital age, this goes beyond traditional political activities like voting and includes various forms of online engagement (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.365).

Expressive participation involves expressing political aims and intentions, regardless of the political sphere (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.364). This can include discussions with friends about politics or expressing support for political figures (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.364).

Personalized politics recognizes that civic engagement is increasingly directed towards corporations, brands, and transnational policy forums (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.365). Social media enables individuals to connect, organize, and mobilize around diverse issues, from fair trade to environmental concerns (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.365).

Digital Citizenship Education: Empowering the Next Generation

To foster participatory democracy through digital citizenship education, these are what we need to do:

First, teach with an intersectional lens. We need to help students understand how social identities intersect and shape experiences in the digital world (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.366). Educators, researchers, and practitioners should keep in mind that no digital citizenship educational model or policy can completely transform how marginalized students experience failure, success, belonging, and struggles in school until they truly understand how students’ social identities are conceptualized and entangled with race, ethnicity, class, gender, language, ability, and religion in a digital world (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.366).

Second, use social media for empowerment. Encouraging students to use social media to express their views, negotiate meanings, and support marginalized groups can be beneficial (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.366). Social media legitimize the public negotiation of meanings among oppositional and marginalized groups (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.366).

Finally, promote digital literacy. Students should be equipped with the skills to critically analyze online content and express themselves effectively in digital spaces (Choi & Cristol, 2021, p.362).

GetUp: A Case Study in Digital Engagement 💪

Organizations like GetUp demonstrate the evolving landscape of political engagement in the digital age (Vromen, 2016, p.2). By utilizing digital techniques, online petitions, and storytelling, GetUp effectively mobilizes citizens and integrates narrative-style storytelling in their campaigns to mobilize engagement (Vromen, 2016, p.2). This highlights the potential for hybrid organizations to drive social and political change through digital platforms (Vromen, 2016, p.3).

Click to visit GetUp's website

Toward A More Just Digital World

Digital citizenship is not just about individual responsibility; it's about understanding power dynamics, promoting social justice, and participating in democracy in the digital age (Choi & Cristol, 2021, pp.366-367). By embracing intersectionality and participatory democracy, we can create a more equitable and inclusive online world.

References

Choi, M., & Cristol, D. (2021). Digital Citizenship with Intersectionality Lens: Towards Participatory Democracy Driven Digital Citizenship Education. Theory into Practice, 60(4), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1987094

Home. (n.d.). GetUp. https://www.getup.org.au/campaign/all

Vromen, A. (2016). Introduction. Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-48865-7_1

0 notes

Text

Reality TV: The Ultimate Social Media Playground?

Let's take a look into the wild world where reality TV and social media collide. We know reality TV is designed to get people talking (Deller, 2019, p.153). It holds a mirror up to human behavior, which extends to audiences critiquing actions and speculating on authenticity (Deller, 2019, p.153). But in the age of social media, this conversation has exploded beyond living rooms and workplaces and now proliferates online (Deller, 2019, p.153).

The Evolution of Reality TV Talk

The Old Days: Forums and blogs like Television Without Pity (TWOP) were the go-to spots for dissecting shows (Deller, 2019, p.153). People would analyze heroes and villains, predict storylines, and critique every little detail of production (Deller, 2019, p.153). Recaps and liveblogs became a staple, with mainstream sites like The Guardian jumping in (Deller, 2019, p.153).

Social Media Takes Over: By the mid-to-late 2000s, sites like MySpace, Facebook, and Twitter became major players (Deller, 2019, p.154). Social media centralized content and discussions across a few platforms (Deller, 2019, p.155). Though forums and blogs haven't disappeared entirely, they've definitely been impacted (Deller, 2019, p.153).

Twitter: The King of Live TV Chatter

While reality TV content exists on pretty much every social media platform, Twitter (X) really encourages interaction from TV viewers (Deller, 2019, p.155). It's less about "value added" content (behind-the-scenes footage, etc.) and more about tweeting during the broadcast (Deller, 2019, p.155).

Why is Twitter (X) so popular for reality TV?

Liveness: Reality TV, especially live shows with voting, emphasizes "liveness," creating a shared social experience (Deller, 2019, p.155).

Hashtags: Broadcasters and production companies hype up the liveness with on-screen hashtags and verbal prompts from presenters (Deller, 2019, p.156). Official accounts, hosts, experts, and even celebrities can join in the live-tweeting fun.

Click to see the original post

Humor, Memes, and GIFs: The Language of Reality TV

Reality TV and humor go hand-in-hand (Deller, 2019, p.158). Social media discussions are full of puns, sarcastic commentary, GIFs, and memes (Deller, 2019, p.158). There are even fan accounts dedicated solely to jokes and memes from reality shows.

Meme Origin: Real Housewives Of Beverly Hills

Reality Stars: From TV to Your Feed

It's not just viewers who are all over social media. Reality participants are expected to have an online presence (Deller, 2019, p.159). They build hype before, during, and after their shows (Deller, 2019, p.159). Some shows even offer advice on how to manage their accounts (Deller, 2019, p.159).But apparently, it's a double-edged sword. While they can connect with fans, promote their brand, and even show their "authentic" side (Deller, 2019, p.163), they can be exposed to a torrent of negativity as well (Deller, 2019, p.162).

Reality star Kim Kardashian sharing her view about her online presence. Click to see the article.

Authenticity & the Edited Self

The source also brings up a super interesting point: Social media allows contestants to share their own version of events, especially if they feel they were unfairly edited on the show (Deller, 2019, p.163). Social media is edited, but the editing comes from the individual (Deller, 2019, p.164).

The Future of Reality TV?

So what's next for reality TV in the age of social media? Stewart argues that television networks have utilized social media to recreate the affect of a localized viewing community (Stewart, 2019, p.353). The liveness of television complements the live affect presented by social media platforms (Stewart, 2019, p.354). It is likely that reality television will continue to capitalize on developments within social media technologies (Deller, 2019, p.174). Expect more streaming, reboots, hybrid formats, and ethical considerations. Ultimately, reality TV's endurance proves it's a central part of the television landscape (Deller, 2019, p.175).

References

Deller, R. A. (2019). Reality television : the television phenomenon that changed the world. Emerald Publishing.

Enriquez, J. (2016, October 24). Kim Kardashian says social media have been “more beneficial than negative.” Mail Online; Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3865590/Kim-Kardashian-says-pros-social-media-beneficial-negative-things-60-Minutes-interview-Paris-robbery.html

LaCapria, K. (2024, July 27). The Best Memes In Reality TV History. TheThings. https://www.thethings.com/reality-tv-memes/

skyhawkstragedy. (2023, October 11). Skyhawk’s Tragedy: Where the Hits are Sky-High. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/skyhawkstragedy/730865201726062592/i-have-watched-wayyyy-too-many-korean-survival

Stewart, M. (2019). Live tweeting, reality TV and the nation. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(3), 352–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877919887757

(2025). X.com. https://x.com/fraktsiyalore/status/1884222746357555701

0 notes

Text

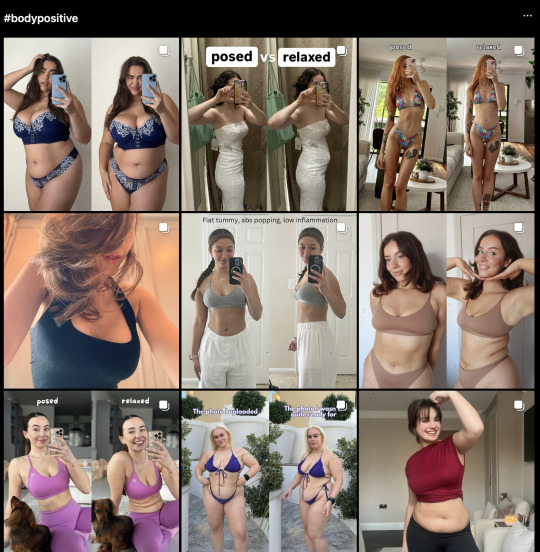

Body Positivity Or Just A New Beauty Ideal? The Truth About #BodyPositive On Tumblr

The Diversity Dilemma The study by Reif, Miller, & Taddicken (2022) took a look at a bunch of selfies posted with the #bodypositive tag. They found that while the idea of body positivity is all about accepting everyone, a lot of the pictures still featured women who were young and white (Reif et al., 2022, p.11). So where was the diversity? It's like, even in spaces that try to be inclusive, those existing beauty standards sneak in (Reif et al., 2022, p.1). Keller (2015) talks about how privilege affects who can even participate in feminism. Not everyone has the time, resources, or even the safety to be visible online (Keller, 2019, p.3).

Original post Self-Acceptance vs. Self-Improvement: A Battle Within

The researchers also looked at what people were saying in their posts. They found two main themes: self-acceptance and self-improvement (Reif et al., 2022, p.13). Amazingly, self-acceptance is all about loving your body now (Reif et al., 2022, p.13). But then there's the self-improvement side, with posts about weight loss and fitness journeys (Reif et al., 2022, p.14). It's like, even when we're trying to love ourselves, there's this pressure to be better.

You can easily see captions saying, "I'm learning to love my body," but then they're followed by, "…so I'm hitting the gym". It's like, can't we just exist without feeling the need to optimize? Maddox (2019) would say that it reflects a postfeminist pressure to be both empowered and disciplined (Maddox, 2019, Analysis).

Performing Femininity: Are We Just Playing a Role?

Now this is where it gets really interesting. The researchers looked at how the women in the selfies were posing, using categories based on Goffman's ideas about gender (Reif et al., 2022, p.9). They found a lot of "feminine touch," head tilts, and poses where people weren't looking directly at the camera (Reif et al., 2022, p.12).

And get this: these poses were more common than in selfies using general tags on Instagram (Reif et al., 2022, p.12). So, what's going on? Are people exaggerating femininity to get attention?. Are they trying to fit in?. Or are they reclaiming those poses for themselves? Keller's (2015) work on feminist bloggers is key here: How much of what we do online is a performance? How much is "authentic"? These questions really got me thinking.

Likes, Comments, and the Hunger for Validation

About the reactions, the study found that only about half the selfies got any notes at all (Reif et al., 2022, p.14). And the comments? Mostly positive, which is nice, but… Reif, Miller, & Taddicken (2022) also found some comments that were straight-up sexualizing (Reif et al., 2022, p.17). It shows how positive feedback can also lead to objectification and pressure.

Tiidenberg & Cruz (2015) call it the "popularity paradox": We want to be seen, but we also want to be liked, and that can make us do some weird stuff.

Tumblr Vibes: Platform Vernacular Matters

Keller's (2015) research emphasizes that each platform has its own "vernacular" (Keller, 2019, p.9). Tumblr, back then, was a space where people could be more real, more raw (Keller, 2019, p.8). Reif, Miller, & Taddicken (2022) notes that Tumblr, before its policy changes, was a unique space (Reif et al., 2022, p.2). But even with that freedom, the study shows that power and privilege still shaped what was visible (Reif et al., 2022, p.2).

So, Where Do We Go From Here?

So what does it all mean? This study is like a reminder that creating truly inclusive spaces online is hard work. We have to be aware of who gets seen, challenge those "beauty standards" and push back against the pressure to "improve". Things have changed since 2017, but the questions are still super relevant:

How can we make online spaces truly inclusive?.

How can we be more aware of the pressure to perform?.

How can we create communities that are genuinely supportive, not just focused on likes?.

What do you think? How do you navigate body positivity online?

References

Keller, J. (2019). “Oh, She’s a Tumblr Feminist”: Exploring the Platform Vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms. Social Media + Society, 5(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119867442

Maddox, J. (2019). “Be a badass with a good ass”: race, freakery, and postfeminism in the #StrongIsTheNewSkinny beauty myth. Feminist Media Studies, 21(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1682025

Reif, A., Miller, I., & Taddicken, M. (2022). “Love the Skin You‘re In”: An Analysis of Women’s Self-Presentation and User Reactions to Selfies Using the Tumblr Hashtag #bodypositive. Mass Communication and Society, 26(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2022.2138442

somedayilldelete. (2024, May 15). life lol. Tumblr. https://www.tumblr.com/somedayilldelete/750574334582652928/okay-so-this-is-a-new-blog-that-im-starting

Tiidenberg, K., & Gómez Cruz, E. (2015). Selfies, Image and the Re-making of the Body. Body & Society, 21(4), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034x15592465

#mda20009#bodypositive#selfies#socialmedia#feminism#authenticity#self love#selfworth#digital communities

2 notes

·

View notes