#SF, especially #Alien. My latest video #games interest. Self-described #good advice, philosophical/psychological #thoughts, and #mbti. For balance, nature and #travel photos, #art that I find interesting, and the obligatory #humor with or without #animals.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

"You know where I can find a really legit liquor store?"

1 note

·

View note

Text

https://archiveofourown.org/works/66992527

Y'ALL THIS IS THE COOLEST FANFIC I'VE EVER SEEN.

It is a complete narrative about SecUnits on a Planetary Survey trying to communicate and keep their clients safe while dealing with the restrictions of their govmod.

IT IS ALSO A FULLY INTERACTIVE GAME OF MINESWEEPER.

The story is told BY PLAYING MINESWEEPER.

This fic is criminally underrated go look at it!!!

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

1979

Source: Youtube/The Kinolibrary

753 notes

·

View notes

Text

Murderbot: "Ugh, yes, fine I have friends. And I'm glad to not be dead or taken over or whatever. That doesn't mean I'm social. I'm still antisocial."

ART: "Yes, they know that. You're not subtle about it."

Murderbot: "I'm still not talking to you."

*lingering sense of smugness on the feed*

Muderbot is extremely competent. As much is it harps on how low quality it is, it has consistently made great choices and executed them and saved its humans over and over again. And also now we know from Rapport that it isn't as cheaply made as it thinks.

But also, it wouldn’t have survived a single book if it didn’t have friends

Without Mensah and PresAux it would have been taken over/killed

Without ART’s help it would’ve been captured

Without Miki it would be dead

Without Gurathin it would be dead

Without bots in Preservation Station it would be dead

Without ART, 2.0, Three, Preservation and Peri's humans it would be taken over by TargetControlSystem

Without ART drone it would be dead

What I’m saying is friendship is magic.

No, but seriously, as much as the series is about Murderbot learning to be a person (allowing itself to be one), it is also about the importance of friendship, of finding people to connect to. How these bonds can save you as a person, but also quite literally.

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Femininity is rewarded!" "No, masculinity is rewarded!"

You're both wrong. It's perceived gender conformity that's actually rewarded.

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

"We need a leader who will stop--"

No.

No leader will save us.

It's literally up to We The People.

Big or small. Local or national.

Connect. Organize. Act.

For decades, allies of the United States lived comfortably amid the sprawl of American hegemony. They constructed their financial institutions, communications systems, and national defense on top of infrastructure provided by the US.

And right about now, they’re probably wishing they hadn’t.

Back in 2022, Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” to describe a cycle that has played out again and again in the online economy. Entrepreneurs start off making high-minded promises to get new users to try their platforms. But once users, vendors, and advertisers have been locked in—by network effects, insurmountable collective action problems, high switching costs—the tactics change. The platform owners start squeezing their users for everything they can get, even as the platform fills with ever more low-quality slop. Then they start squeezing vendors and advertisers too.

People don’t usually think of military hardware, the US dollar, and satellite constellations as platforms. But that’s what they are. When American allies buy advanced military technologies such as F-35 fighter jets, they’re getting not just a plane but the associated suite of communications technologies, parts supply, and technological support. When businesses engage in global finance and trade, they regularly route their transactions through a platform called the dollar clearing system, administered by just a handful of US-regulated institutions. And when nations need to establish internet connectivity in hard-to-reach places, chances are they’ll rely on a constellation of satellites—Starlink—run by a single company with deep ties to the American state, Elon Musk’s SpaceX. As with Facebook and Amazon, American hegemony is sustained by network logic, which makes all these platforms difficult and expensive to break away from.

For decades, America’s allies accepted US control of these systems, because they believed in the American commitment to a “rules-based international order.” They can’t persuade themselves of that any longer. Not in a world where President Trump threatens to annex Canada, vows to acquire Greenland from Denmark, and announces that foreign officials may be banned from entering the United States if they “demand that American tech platforms adopt global content moderation policies.”

Ever since Trump retook office in January, in fact, rapid enshittification has become the organizing principle of US statecraft. This time around, Trumpworld understands that—in controlling the infrastructure layer of global finance, technology, and security—it has vast machineries of coercion at its disposal. As Mark Carney, the prime minister of Canada, recently put it, “The United States is beginning to monetize its hegemony.”

So what is an ally to do? Like the individual consumers who are trapped by Google Search or Facebook as the core product deteriorates, many are still learning just how hard it is to exit the network. And like the countless startups that have attempted to create an alternative to Twitter or Facebook over the years—most now forgotten, a few successful—other allies are now desperately scrambling to figure out how to build a network of their own.

Infrastructure tends to be invisible until it starts being used against you. Back in 2020, the United States imposed sanctions on Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, for repressing democracy protests on China’s behalf. All at once, Lam became uniquely acquainted with the power of the dollar clearing system—a layer of the world’s financial machinery that most people have never heard of.

Here’s how it works: Global banks convert currencies to and from US dollars so their customers can sell goods internationally. When a Japanese firm sells semiconductors to a tech company in Mexico, they’ll likely conduct the transaction in dollars—because they want a universal currency that can quickly be used with other trading partners. So these firms may directly ask for payment in dollars, or else their banks may turn pesos into dollars and then use those dollars to buy yen, shuffling money through accounts in US-regulated banks like Citibank or J.P. Morgan, which “clear” the transaction.

So dollar clearing is an expedient. It’s also the chief enforcement mechanism of US financial policy across the globe. If foreign banks don’t implement US financial sanctions and other measures, they risk losing access to US dollar clearing and going under. This threat is so existentially dire that, when Lam was placed under US sanctions, even Chinese banks refused to have anything to do with her. She had to keep piles of cash scattered around her mansion to pay her bills.

That maneuver against Lam was, at least on its face, about standing up for democracy. But in his second term, Trump has wasted no time in weaponizing the dollar clearing system against any target of his choosing. In February, for example, the administration imposed sanctions on the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court after he indicted Benjamin Netanyahu for alleged war crimes. Now, like Lam in Hong Kong, the official has become a financial and political pariah: Reportedly, his UK bank has frozen his accounts, and Microsoft has shut down his email address.

Another platform that Trump is weaponizing? Weapons systems. Over the past couple of decades, a host of allies built and planned their air power around the F-35 stealth fighter jet, built by Lockheed Martin. In March, a rumor erupted online—in Reddit posts and X threads—that F-35s come with a “kill switch” that would allow the US to shut them down at will.

Sources tell us that there is no such kill switch on the F-35, per se. But the underlying anxiety is not unfounded. There is, as one former US defense official described it, a “kill chain” that is “essentially controlled by the United States.” Complex weapons platforms require constant maintenance and software updates, and they rely on real-time, proprietary intelligence streams for mapping and targeting. All that “flows back through the United States,” the former official said, and can be blocked or turned off. Cases in point: When the UK wanted to allow Ukraine to use British missiles against Russia last November, it reportedly had to get US sign-off on the mapping data that allowed the missiles to hit their targets. Then, after Trump’s disastrous Oval Office meeting with Volodymyr Zelensky in late February, the US temporarily cut off intelligence streams to Ukraine, including the encrypted GPS feeds that are integral to certain precision-guided missile systems. Such a shutoff would essentially brick a whole weapons platform.

Communication systems are, if anything, even more vulnerable to enshittification. In a few short years, Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites—which now make up about 65 percent of all active satellites in orbit—have become an indispensable source of internet access across the world. On the eve of Trump’s second inaugural, Canada was planning to use Starlink to bring broadband to its vast rural hinterlands, Italy was eyeing it for secure diplomatic communications, and Ukraine had already become dependent on it for military operations. But as Musk joined the Trump administration’s inner circle, a dependence on Starlink came to seem increasingly dangerous.

In late February, the Trump administration reportedly threatened to withdraw Starlink access to Ukraine unless the country handed over rights to exploit its mineral reserves to the US. In a March confrontation on X, Musk boasted that Ukraine’s “entire front line would collapse” if he turned off Starlink. In response, Poland’s foreign minister, Radek Sikorski, tried to stand up for an ally. He tweeted that Poland was paying for Ukraine’s access to the service. Musk’s reply? “Be quiet, small man. You pay a tiny fraction of the cost. And there is no substitute for Starlink.”

It isn’t just big US defense contractors that might enforce the administration’s line. European governments and banks often run on cloud computing provided by big US multinationals like Amazon and Microsoft, and leaders on the continent have begun to fear that Trump could choke off EU governments’ access to their own databases. Microsoft’s president, Brad Smith, has claimed this scenario is “exceedingly unlikely” and has offered Europeans a “binding commitment” that Microsoft will vigorously contest any efforts by the Trump administration to cut off cloud access, using “all legal avenues available.” But Microsoft has failed to publicly explain its reported denial of email access to the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor. And Smith’s promise may not be enough to ward off Europeans’ fears, to say nothing of the Trump administration’s advances. The European Commission is now in advanced negotiations with a European provider to replace Microsoft’s cloud services, and the Danish government is moving from Microsoft Office to an open source alternative.

Of course, the American tech industry has famously cozied up to Trump this year, with CEOs attending his inauguration, changing content moderation policies, and rewriting editorial missions in ways that are friendlier to administration priorities. And as always, what Trump can’t gain through loyalty, he’ll extract through coercion. Either way, the traditional platform economy is being reshaped as commercial platforms and government institutions merge into a monstrous hybrid of business monopoly and state authority.

In the face of all these affronts to their sovereignty, a chorus of world leaders has woken from its daze and started to talk seriously about the once-unthinkable: breaking up with the United States. In February, the center-right German politician Friedrich Merz—upon learning that he’d won his country’s federal election—declared on live TV that his priority as chancellor would be to “achieve independence” from the US. “I never thought I would have to say something like this on a television program,” he added.

In March, French president Emmanuel Macron echoed that sentiment in a national address to his people: “We must reinforce our independence,” he said. Later that month, Carney, the new Canadian prime minister, said that his country’s old relationship with the US was “over.”

“The West as we knew it no longer exists,” said Ursula von der Leyen, the head of the EU Commission, in April. “Our next great unifying project must come from an independent Europe.”

But the reality is that, for many allies, simply declaring independence isn’t really a viable option. Japan and South Korea, which depend on the US to protect them against China, can do little more than pray that the bully in the White House leaves them alone.

For now, Denmark and Canada are the other US allies most directly at risk from enshittification. Not only has Trump put Greenland (a protectorate of Denmark) and Canada at the top of his menu for territorial acquisition, but both countries have militaries that are unusually closely integrated into US structures. The “transatlantic idea” has been the “cornerstone of everything we do,” explains one technology adviser to the Danish government, who asked to remain anonymous due to the political sensitivity of the subject. Denmark spent years pushing back against arguments from other allies that Europe needed “strategic autonomy.” And according to a former adviser on Canadian national security, the “soft wiring” binding the US and Canadian military systems to each other makes them nearly impossible to disentangle.

That explains why both countries have been slow to move away from US platforms. In March, the outspoken head of Denmark’s parliamentary defense committee grabbed attention on X by declaring that his country’s purchase of F-35s was a mistake: “I can easily imagine a situation where the USA will demand Greenland from Denmark and will threaten to deactivate our weapons and let Russia attack us when we refuse,” he tweeted. But in reality, the Danish government is even now considering purchasing more F-35s.

Canada, too, has already built its air-strike capacities on top of the F-35 platform; switching to another would, at best, require vast amounts of retooling and redundancy. “We’re going to look at alternatives, because we can’t make ourselves vulnerable,” says the Canadian adviser. “But we would then have a non-interoperable air force in our own country.”

If allies keep building atop US platforms, they render themselves even more vulnerable to American coercion. But if they strike out on their own, they may pay a steeper, more immediate price. In March, the Canadian province of Ontario canceled its deal with Starlink to bring satellite internet to its poorer rural areas. Now, Canada will have to pay much more money to build physical internet connections or else wait for its own satellite constellations to come online.

If other governments followed suit in other domains—breaking their deep interconnections with US weapons systems, or finding alternative cloud platforms for vital government and economic services—it would mean years of economic hardship. Everyone would be poorer. But that’s exactly what some world leaders have been banding together to contemplate.

In Europe, discussions are coalescing around an ambitious idea called EuroStack, an EU-led “digital supply chain” that would give Europe technological sovereignty independent from the US and other countries.

The idea gathered steam a couple of months before Trump’s reelection, when a group of business leaders, European politicians, and technologists—including Meredith Whittaker, the president of Signal, and Audrey Tang, Taiwan’s former minister of digital affairs—met at the European Parliament to discuss “European Digital Independence.” According to Cristina Caffarra, an economist who helped organize the meeting, the takeaway was stark: “US tech giants own not only the services we engage with but also everything below, from chips to connectivity to cables under the sea to compute to cloud. If that infrastructure turns off, we have nowhere to go.”

The feeling of urgency has only grown since Trump retook office. The German and French governments have embraced EuroStack, while major EU aircraft manufacturers and military suppliers like Airbus and Dassault have signed on to a public letter advocating its approach to “sovereign digital infrastructure.” In all the European capitals, the Danish government adviser says, teams of people are calculating what elements should be folded into the effort and what it would cost.

And EuroStack is just one part of the response to enshittification. The European Union is also putting together a joint defense fund to help EU countries buy weapons—but not from the US. The EU’s executive agency, the European Commission, is patching together a network of satellites that could eventually provide Ukraine and Europe with their own home-baked alternative to Starlink. Christine Lagarde, the head of the European Central Bank, has also started talking pointedly about how Europe needs its own infrastructure for payments, credit, and debit, “just in case.”

Robin Berjon, a French computer scientist who spoke at the first EuroStack meeting, acknowledges that the project has yet “to get proper financing and institutional backing” and is “more a social movement than anything else.” If these projects succeed, they will be expensive and slow to bring online—and most will almost certainly underperform cutting-edge US equivalents. But Europe’s issues with American platforms are no longer just about ads and cookies; they’re about the very future of its democracies and national security. And in the longer term, the US itself faces a disquieting question. If it no longer provides platforms that the rest of the world wants to use, who will be left—and whose interests will be served—on American networks?

After Doctorow’s platform monopolists enshittified the user experience, they turned on the businesses that were their actual paying customers and started to abuse them too. US citizens are, ostensibly, the true customers of the US government. But as difficult and expensive as it will be for US allies to escape the enshittification of American power—it will be much harder for Americans to do so, as that power is increasingly turned against them. As WIRED has documented, the Trump administration has weaponized federal payments systems against disfavored domestic nonprofits, businesses, and even US states. Contractors such as Palantir are merging disparate federal databases, potentially creating radical new surveillance capabilities that can be exploited at the touch of a button.

In time, US citizens may find themselves trapped in a diminished, nightmare America—like a post-Musk Twitter at scale—where everything works badly, everything can be turned against you, and everyone else has fled. De-enshittifying the platforms of American power isn’t just an urgent priority for allies, then. It’s an imperative for Americans too.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

When President Donald Trump loses the support of posters on The Donald, it’s notable, to say the least. The ultra-pro-Trump message board, whose members were accused of helping plan the January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol, has been one of the most loyal corners of the internet for the president.

But just like many other parts of the MAGA universe as of late, many users have had enough.

“So disappointed in Trump on this one, it’s inexcusable,” a user wrote in the early hours of Monday morning, echoing widespread anger and resentment at the Trump administration’s handling of the Jeffrey Epstein case.

Trump and his allies had promised Republicans that once they took office they would release explosive revelations about what really happened when Epstein, the accused sex trafficker, died in custody in 2019—and his supposed “client list.” But last week, the FBI and the Department of Justice issued a memo concluding that there was no cover-up and that Epstein had died by suicide. Even worse, the memo stated that the Epstein “client list” that attorney general Pam Bondi had said was on her desk in February didn’t actually exist.

The outrage was instant and overwhelming, as grassroots supporters, right-wing influencers, and conservative media outlets fumed. It wasn’t just about Epstein. It was, to them, a denial of the alleged child abuse rings that have become a cornerstone of conspiracy theories related to Epstein. The anger intensified further after WIRED reported that surveillance footage from a camera positioned near Epstein’s prison cell the night before he was found dead had likely been modified.

Trump has been scrambling to dismiss the criticism and defend Bondi, writing in a Truth Social post on Saturday that “selfish people” are trying to harm his administration “all over a guy who never dies.”

The uproar around Epstein is just the latest in a number of bubbling Trumpworld concerns. For Tucker Carlson, the former Fox News host who now streams on X, it was the bombing of Iran. For Laura Loomer, a noted conspiracy theorist who has Trump’s ear, it was Trump’s acceptance of a luxury plane from Qatar. For Ben Shapiro, a pro-Trump podcaster, it was tariffs. For Joe Rogan, a massively popular podcaster, it was ICE raids targeting noncriminal, migrant workers. For Elon Musk, who recently left his role in DC as a special government employee, it was the Big Beautiful Bill.

To date, most high-profile right-wing media figures have stopped short of attacking Trump directly, focusing their anger instead on Bondi or other administration figures. But as resentment continues to grow in these communities who feel betrayed by Trump, that could change.

“The potential is a death by thousands cuts scenario, where enough criticism hits from enough different angles that the calculus switches for a lot of the more influential figures in the movement,” Matthew Gertz, a senior fellow at progressive media watchdog group Media Matters for America, tells WIRED.

One of the first signs that the current Trump administration would not be able to keep all its supporters happy came when Secretary of Health Robert F. Kennedy Jr. endorsed the MMR vaccine in the face of a deadly measles outbreak in Texas that began in January. Kennedy was hailed as an anti-vaccine hero by the alternative health community upon his appointment, but many of those same people were furious following his vaccine recommendation. “I’m sorry, but we voted for challenging the medical establishment, not parroting it,” Mary Talley Bowden, a doctor who criticized Covid vaccines, wrote on X in April, echoing many other angry responses.

Last week, conspiracy theorists who believe the government is secretly controlling and manipulating the weather to control the US population began to turn on Trump.

Lee Zeldin, the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, posted a video saying that his agency would release “everything we know” about geoengineering. When the subsequent webpages went live with information debunking the “chemtrails” conspiracy theory, Trump supporters were not happy. The chemtrails conspiracy theory falsely claims that the straight-line condensation trails visible behind aircraft are actually clouds of toxic chemicals sprayed by government-controlled planes in order to infect the population.

“Zeldin is engaged in a pitiful attempt at damage control due to the rapidly growing awareness of the weather warfare raging in our skies,” Dane Wigington, who writes a conspiracy-laced geoengineering blog, wrote on X.

Even Trump’s key conservative platforms are drawing critique. Though Trump’s embrace of ultra-hard-line immigration practices and far-right policies like remigration seemed to be the answer to the wishes of even the most extreme far-right figures, some are concerned the deportations are not happening nearly fast enough.

“Mass deportations are a lie,” white nationalist Nick Fuentes wrote on X last week, later adding: “At a certain point you can’t keep blaming the ‘bad advisors’ or personnel around Trump. We have been playing this game for +10 years now. Who appointed all of the personnel anyway? There are no excuses left.” This sentiment was shared among many far-right communities online. “Trump needs to just do it. We elected him because he said he would. Just do it,” one member of The Donald wrote.

“When do the mass deportations start?” David Freeman, a pro-Trump influencer known online as Gunther Eagleman, wrote on X earlier this month to his 1.4 million followers.

Some influencers have started to directly call out Trump.

“He’s doing the exact opposite of everything I voted for,” said Andrew Schulz, a comedian and one of the high-profile podcasters who interviewed Trump in the lead-up to last year’s election, during the most recent episode of his Flagrant podcast.

“The risk for Trump would be if the grassroots people who spend money on subscriptions and who watch YouTube videos and listen to podcasts start demanding something else from the people in the influencer class,” says Gertz. “The influencer class is going to have to adjust to what would be a new paradigm in the way right-wing political media is functioning. I think we’re certainly nowhere near there yet, but if that does ever switch I would imagine it would happen pretty quickly as different figures see others having success with it.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is your regularly scheduled reminder that "Life finds a way" is about the dinosaurs becoming transgender

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

i made this in 3 days because these books have taken hold of me

Bonus page:

Redacted everything Miles says that's false

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

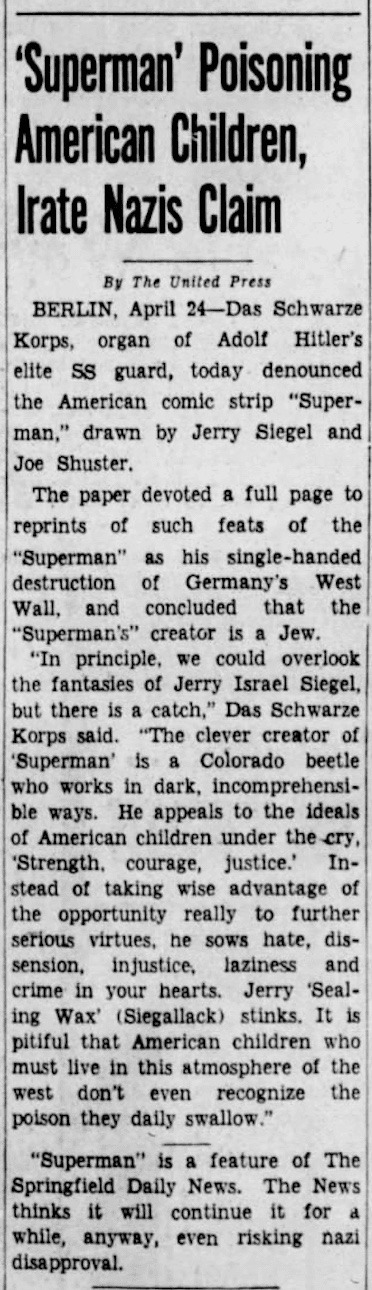

Researching, published in 1940. History repeating itself is fascinating and eerie.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

i love when i share what seems to me like basic entry-level critical self-awareness advice with other people and they react like i'm a terrifyingly transgressive but tempting corrupting influence. i really missed my calling as one of those villains who are unimpeachably ideologically correct but undermined by a personal deficiency of character that makes them hideously unattractive to anyone more socially adept.

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

shot in the HEAD. and you're to blame. You are not good. At dart game

52K notes

·

View notes