Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Hey Alax!

I really enjoyed the creative twist of how you wrote your blog post. Those small details, like describing hunting for buckeyes and looking for tadpoles, set the scene and allowed me to feel like I was there. It gave me as a reader the ability to see what shaped you to become the nature interpreter you are today.

I appreciate your mention that there's something everyone can find in nature that they love. As we have learned, some people have not had the joy of experiencing nature the way we have. This is the gift of being an interpreter, to help people find that aspect they see the beauty in, and want to learn about.

In this course and these blog posts, we often talk about who we are as nature interpreters, and how our environments have shaped our beliefs and ideas. We perhaps talk much less about the actual interpreters in our lives that have inspired us. I really enjoyed reading the way Chris changed your relationship with nature, specifically to have a deeper appreciation for certain aspects. Funny enough, he may not even be aware that he is an interpreter, and how his passion led to your own. His commitment and excitement for what he teaches embodies the way we all hope to be as interpreters in the future. When reading the way this sparked your love for birds, it reminded me of this line in the textbook discussing what interpretation does for people. “Ultimately, it helps them to further understand their home environment and the world around them” (Beck et al., 2018). Birds are such simple creatures, and you have probably been surrounded by them your entire life. Yet, this one experience changed your relationship with them forever, for the better.

A Passion for Nature (ft. Buckeyes, Birds, and Blame)

For my final required blog post, I wanted to kick things off by revisiting one of our first topics: my relationship to nature. I look back fondly on my childhood trips to our local park, where little hands would scavenge for buckeyes, stuffing them into pockets until they were full to bursting. This was done so my two brothers and I could have copious ammunition to throw at one another during our trail hikes (in case you weren’t aware, buckeyes are pretty much the perfect projectiles for rowdy children as these nuts are both small enough to not really hurt and heavy enough to allow for a bit of speed when given a proper 'thwiiip!'. Not that I’m condoning that of course, but you know... kids will be kids). I spent much of my childhood walking the creek behind my house and looking for tadpoles and climbing trees.

I was given copious opportunities to connect with nature; from bike rides through our neighborhood to apple picking, soccer tournaments and camping trips and forts in the woods. In the video presented to us this week, Dr. Suzuki describes how children often aren’t given the chance to contemplate and absorb experiences today. We try to break down our lives into small chunks and cram as much into those chunks as we can (DavidSuzukiFDN, 2012). I’m lucky because I was given that space to just be, to think, to absorb, to come to my own conclusions and make my own discoveries.

Moving forward as I grow into who I want to be as a nature interpreter, I’d like to think that my beliefs and my responsibilities will be geared towards helping children and other adults feel that same sense of discovery and joy and awe that I often felt as a kid. In the article “Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope” it is said that children love the art of discovering things (Clearing Magazine, 2019). I believe that allowing kids the opportunity to find things, to hunt for their own buckeyes, to search for their own tadpoles and to dig their hands in the dirt is imperative to building a strong relationship with nature.

My belief is that everyone can find something they love about nature. Whether it’s your garden, as was the case for Richard Louv, or the mountain woods as it was for David Suzuki, there’s something for everyone (DavidSuzukiFDN, 2012). I see my responsibility, therefore, as helping people find the thing they love about nature. My responsibility is to spark the joy and the creativity that I feel being in nature, so others can enjoy it as well.

According to Tilden’s Principles of Interpretation, the point of great interpretation is not just to deliver information to people, but to provide that information in a way that is engaging and uplifting and entertaining (Beck et al., 2018). We want to educate people, but we also want to inspire people! I’ve recently come to know Chris Earley, an interpreter who works at the Arboretum here on campus, and if you have the chance to get to know Chris or hear him speak, and I simply cannot stress this enough, take that opportunity!

Chris is such a great naturalist, mostly because he loves what he does. His joy for nature is contagious. During my master's program, we all had to attend three workshops led by him. Each one was about seven hours long with an hour lunch break in the middle (a full day, to be sure). The workshops were designed to help us build our ID skills when it came to different kinds of birds (one workshop was aimed at hawks, one at ducks, and one at warblers). Chris wasted absolutely zero time in these workshops, teaching us as many as 35 different bird species in the span of just one workshop. It was A LOT of information, and most of us left exhausted from the bombardment of technical information being thrown at us. And despite these being some of the longest days we had, most of the students in my cohort agree: those workshops were our favorite. Why? Because of Chris.

Chris’ knowledge is extensive, no one can argue that fact, but the way he teaches and engages people.... it’s another thing entirely. He kept our rapt attention for a total of twenty-one. hours. Talking JUST about birds! Before talking with Chris, I didn’t really have a huge interest in birds. I didn’t dislike them by any means, but I didn’t have any strong love for them. Now I look for them everywhere, I have a bird feeder at my window, I keep a birding log. I find it truly remarkable how one person’s joy can infect others, spreading the disease of ‘caring’ just as easily as influenza might travel through a crowded room.

My approach to interpreting in the future is to simply let my affection and excitement about nature speak for itself. I love trees, I love birds, I love flowers and squirrels and bears, I love rivers, mountains, sunsets, and gardening! Nature is all around us, but I think sometimes, some people forget that. We like to place the blame for this problem on technology: many of us get so sucked into our screens, scrolling through social media or trapped behind a laptop doing school or work that we stop paying attention to Mother Nature.

Now, I don't want you to get the wrong idea here, reader. I’m in my 20’s too, so I love video games and TV and TikTok as much as the next person our age. My plans for tonight in fact? Playing some Stardew Valley with my mom before watching the newest episode of Daredevil. Technology is great, and I don’t know that it’s 100% evil or deserves to take on the entire blame for the growing epidemic of environmental apathy. But I think there’s some work that needs to be done to break through that glass wall we hold in our hands. Work that we, as nature interpreters, are taking upon ourselves. It’s our job to be more engaging, interesting, and thought provoking than a magic doohickey that can tell you pretty much anything you want to know.

So how can we do that? How will I do that? Like I said earlier, I think the answer lies in genuine enthusiasm and passion. I think it’s relatively safe to say that we all took this class because we love nature. Showing that love and allowing others to discover their own love for nature in their own way, in their own time, is how I believe we build deeper connections to the natural world.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

REFERENCES

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

Clearing Magazine. (2019, June 17). Why environmental educators shouldn’t give up hope. CLEARING. https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/14300

DavidSuzukiFDN. (2012, July 20). David Suzuki and Richard Louv @AGO. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F5DI1Ffdl6Y

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Aliya!

I really enjoyed reading your idea that if something has value to a person, it is because they care about it and have knowledge on it. I honestly have never thought about it in that way before. It makes me think about what we have learned in school and growing up. I believe I have always deeply cared about the future of our world because my mom was always a big advocate for sustainability. As interpreters, we have the power to help people expand their mindset. If someone does not necessarily value nature, we have the ability to provide them knowledge on different aspects of it, to ignite that value. There is a statement made in the textbook that reminds me of your passion, stating that an interpreter “Strives to embrace the wonder and beauty of life and share that with others” (Beck et al., 2018, Chapter 1).

Your mention of inclusivity and incorporating technology with hands-on learning reminds me of what I have learned throughout this course. I too, asked myself the same question. Since people often learn best with action and hands on learning, yet using technology is so prevalent today, how can we combine the two? As I reflected on this, something I found that I would like to do going forward is to spark action through technology, such as blogs and podcasts. Examples of this is giving ideas and prompts for ways people can connect with nature after listening/reading.

Your blog posts show the knowledge you have in many aspects of the course. It was great to see the multiple points you touched on to show your growth, such as understanding your audience, respecting culture and history, and application to your future role.

Interpretive Blog #9

As I near the end of this course, I find myself reflecting on the key question: What kind of nature interpreter do I want to be? Interpretation is more than just sharing facts; it is about creating connections between people and the natural world. Throughout this journey, I have realized that my personal ethics, responsibilities, and approach to interpretation will shape not only how I engage with my audience but also how I contribute to environmental stewardship in the long term.

At the heart of my passion for nature interpretation is the belief that people will only protect what they understand and care about. This aligns with Freeman Tilden’s (1957) foundational principle that interpretation should reveal deeper meanings beyond surface-level facts. I believe that every individual has an innate connection to nature, whether they recognize it or not, and my role as an interpreter is to help rekindle that bond.

Another core belief I hold is that environmental education should be accessible and inclusive. As Knudson, Cable, and Beck (2018) emphasize, mass media and interpretive storytelling play a significant role in reaching diverse audiences. Not everyone has the privilege to explore pristine natural landscapes, but interpretation—whether through podcasts, digital media, or urban programming—can bring these experiences to people in new and engaging ways.

With these beliefs in mind, I recognize the responsibilities I hold in this role. One of the most important is fostering environmental stewardship. David Suzuki and Richard Louv (2005) emphasize that children who form positive experiences in nature are more likely to grow into adults who protect the environment. This means that every interaction I have with an audience, whether through a guided hike, a podcast, or an online program, must be designed not just to inform but to inspire action.

Another responsibility is ensuring that my interpretations are ethical and culturally respectful. Many Indigenous communities have deep, place-based knowledge of nature that has been passed down for generations. Western science alone cannot fully explain or interpret the land; therefore, I must incorporate Indigenous perspectives and respect their knowledge systems. The importance of this approach is highlighted by Beck and Cable (2011), who state that quality interpretation should include a diversity of voices and perspectives.

Given my personal strengths and interests, I find that storytelling and experiential learning are the most suitable approaches for me. Stories have the power to create emotional connections, making them one of the most effective tools in interpretation. Jacob Rodenburg (2023) notes that personal stories allow audiences to engage with nature on a deeper level, turning facts into meaningful experiences.

Additionally, Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (1984) reinforces the idea that hands-on engagement leads to lasting learning. When people experience nature firsthand—whether by listening to bird songs, feeling the texture of tree bark, or participating in conservation activities—they develop a more personal connection to the environment. I aim to incorporate this interactive approach into my future work, whether through guided hikes, citizen science programs, or digital storytelling.

In today’s digital age, technology is often viewed as a barrier between humans and nature. However, when used correctly, it can be a powerful tool for interpretation. As Knudson et al. (2018) explain, mass media allows interpreters to reach audiences who may never visit natural sites in person. Virtual reality nature tours, live-streamed wildlife cameras, and interactive nature apps can make conservation efforts accessible to a broader audience.

In my own interpretive work, I see technology as a way to enhance engagement rather than replace direct experiences. For example, apps like ‘Pl@ntNet’ and ‘Merlin Bird ID’ can help people identify species in real-time, deepening their appreciation for biodiversity. Meanwhile, podcasts and digital storytelling can bring ecological concepts to life in ways that resonate with modern audiences. My goal is to strike a balance—using technology to enhance learning while still emphasizing direct, in-person experiences with nature.

As a nature interpreter, my ultimate goal is to create meaningful experiences that leave a lasting impact. This means understanding my audience and adapting my approach to meet their needs. For example, younger children may benefit from hands-on activities and storytelling, while adults may be more engaged by scientific discussions and ethical debates about conservation.

Additionally, I believe that interpretation should be provocative in a way that sparks curiosity and action. Tilden (1957) emphasized that good interpretation is not just about delivering facts but about inspiring audiences to think critically and form their own connections to the material. For example, rather than simply explaining deforestation, I might guide a group through a forest and ask them to imagine what it would look like if all the trees were gone. By creating these emotional and intellectual connections, I can make environmental issues feel more personal and relevant.

Ultimately, my role as an interpreter is about more than just educating people about nature—it is about inspiring them to care and take action. I see myself as a bridge between knowledge and stewardship, helping others to form meaningful connections with the environment.

As I move forward in this field, I want to remain adaptable and open to new approaches. Interpretation is an evolving practice, and I know that my methods will continue to grow and change with experience. However, my core ethics—a commitment to inclusivity, ethical storytelling, and experiential learning—will remain constant.

As this course comes to a close, I feel more confident in my ability to make a difference. Whether I am leading a hike, producing an educational podcast, or using digital tools to engage new audiences, I will always strive to make my work meaningful. Because at the end of the day, interpretation is not just about sharing knowledge—it is about creating a sense of wonder, connection, and responsibility for the natural world. Every moment spent in nature is an opportunity to inspire someone else to appreciate and protect it. I hope to foster these moments for as many people as possible, helping them see the magic in the world around them.

References

Beck, L., & Cable, T. T. (2011). The Gifts of Interpretation: Fifteen Guiding Principles for Interpreting Nature and Culture. Sagamore Publishing LLC.

Knudson, L. B., Cable, T. T., & Beck, L. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World.Sagamore Publishing LLC.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice Hall.

Louv, R. (2005). Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Algonquin Books.

Rodenburg, J. (2023). The Role of Storytelling in Environmental Education. Ecological Perspectives Press.

Tilden, F. (1957). Interpreting Our Heritage. University of North Carolina Press.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 09: My Personal Growth as an Interpreter

Hi everyone, welcome back to my blog! I can not believe that this is my last post for the semester, but since it is, I better make it a good one! This post will be delving into my development in this course, my background that has led to my beliefs and approaches, and how the term nature interpretation has evolved for me.

My journey in this course started with very little idea of nature interpretation, or at least so I thought. As I have mentioned a few times throughout this blog, I am in my final semester of a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture. I originally chose this program because I was always drawn to how I could make the world a better place, both aesthetically and environmentally. I also have always been a huge advocate for sustainability and recognizing climate change. This led me to also completing an Environmental Citizenship Certificate. When selecting the courses I would take for my certificate, ENVS3000:Nature Interpretation came up. I remember reading the description for the ‘in person’ version of the course, and reading about planning and delivering an interpretive walk for a community group. To my knowledge at the time, I only associated interpretation with action, such as interpretive walks and dances. Little did I know was the vast way interpretation is embedded in our world, such as “... personal contact with visitors to interpretation through exhibits, signs, self-guiding tours, apps, podcasts, social media, virtual reality, and more” (Beck et al., 2018, Chapter 1).

Funny enough, I only recently delved into the world of understanding ethics this year too, when I completed a course on environmental ethics and perspectives. The combination of these two courses has allowed me to truly understand my beliefs, how they were formed, and what that means for my future as an interpreter. To review, personal ethics are “moral principles that guide an individual’s decisions and actions based on their values, beliefs, and experiences. They shape how one determines right from wrong in daily life” (Taylor, 2024). When going through my ethics course, I came across the ethical perspective of deep ecology. Deep ecology is the belief that humans and nature are not separate entities but act together (Murray, 2017). Deep ecologists believe our relationship with nature must change, and we must recognize that nature has intrinsic value the same way that humans do (McElgunn, 2022). Learning about this belief encapsulated the views I have had since I was a child, that I had never been able to describe with one term. I have always felt like the environment has value just as we do, and it is not just a resource for us to deplete. I have always felt aware and cautious of how my actions now affect future generations. Reading the textbook and course material, I read about this same mindset, such as in Chapter 15 of Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. “Interpreters preserve a legacy for future generations and a foundation upon which citizens can build a better world” (Beck et al., 2018). This allowed me to feel seen and understood, and allowed for advancement in my beliefs.

As I am ending off this course, my beliefs going into it did not really change. Instead, they evolved so that I had a clearer understanding of what I wanted to do with them. The main thing I learned though, is how I share those beliefs with others, in what way I share them, and the responsibilities I have to my environment. Before I began this course, I never thought of myself as a nature interpreter, or even an interpreter in general. Now, it is something I feel like is a part of me and something I want to continue to develop going forward. Defining myself as an interpreter means having a responsibility to grow, not just as a person, but as an interpreter too. Chapter 21 of Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World provided guidelines of how interpreters can evolve and grow “They make the effort to gain relevant specialized education and training, They provide public service with social responsibility, They participate in accreditation and certification programs, They keep current with a research-based foundation of knowledge, They lay out and follow a program of life-long learning, They accept and practice the discipline of an established code of ethics within their workplace” (Beck et al., 2018). This course also allowed me to understand that my responsibilities go deeper than to myself, but the responsibility I have to others. I have learned my responsibility to preserve history, recognizing privilege and unequal opportunities, understanding and catering to all visitors and learning styles, and much much more. I define my goal as an interpreter as being able to “have abilities to use creative imagination to help others understand and enjoy their cultural and natural environments” (Beck et al., 2018, Preface).

Finally, I want to touch on what method I have learned allows me to be the best I can be as an interpreter, which is visual interpretation. I have always been a visual learner myself, and through my degree, I have learned how to make beautiful visualizations. These illustrations show how design can allow for humans to connect with their environment in a positive way, and how spaces can be functional without compromising sustainability. Figure 1 shows an example of a piece of work I have done that shows this.

Figure 1: A 3D Model I made of a site that blends residential living with the existing environment and preserved natural areas.

As this course (and post) comes to an end, I am reflecting on my growth throughout this semester. While my beliefs have not changed, they have evolved and allowed me to understand a deeper form of communication. I will take this with me as I continue to work towards being the best interpreter I can be. I make a promise to myself, and to the world, that I will never stop teaching others the beauty of our environment.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D.M. (2018) Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For a Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

McElgunn, M. (2022, September 22). What is “Deep ecology”? Ecological Landscape Alliance. https://www.ecolandscaping.org/09/developing-healthy-landscapes/sustainability/what-is-deep-ecology/

Murray, D. (2017, March 6). The global and the local: An environmental ethics casebook. Brill. https://brill.com/display/title/33106?language=en

Taylor , E. (2024, December 18). Personal ethics: Definition, importance, and examples. The Knowledge Academy - Online certification training courses provider. https://www.theknowledgeacademy.com/blog/personal-ethics/

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 08: Learning from Nature: How Biomimicry Shapes our World

Did you know that velcro was inspired by burrs sticking to dog fur (Ivanić et al., 2015)? This is biomimicry, and it is by far the most fascinating thing I know about nature. Biomimicry is the idea of imitating processes found in nature for sustainable solutions to modern problems (Biomimicry Institute, 2024). Nature has relied on its own systems and processes through billions of years of evolution to optimize efficiency and resilience. With the looming climate shift, we are learning from this practice and turning to nature for sustainable solutions. Surprisingly, in my 22 years of life, I only first discovered the idea of biomimicry last year, when I was writing my thesis. As I was reading about it, I discovered how much it has influenced our world, through design, architecture, technology, and more. Before I give some examples, I want you to take a moment and think to yourself of any examples of biomimicry that come to mind.

Here are 4 of the infinite ways that nature has inspired advances in our world:

Certain fish species and their shape gave inspiration for cars and ships (Ivanić et al., 2015).

Planes were developed from inventors watching pigeons fly (Ivanić et al., 2015).

Termite mounds influenced many sustainable buildings, due to their natural ventilation (Verbrugghe et al., 2023).

The blades of wind turbines are modeled after the ridges on the fin of the humpback whale, as shown in Figure 1 (Ivanić et al., 2015).

Figure 1: Fin of the Humbackwhale as inspiration for wind turbine blade (Ivanić et al., 2015, p.28)

When you think about it, biomimicry encompasses the very idea of what interpretation is. Maybe not in the way we typically think of it as, where we are communicating to an audience. But, we as humans observed and then translated nature's designs, interpreting patterns, functions, and strategies. From there, we as interpreters can take this a step further and teach about connecting nature's processes into our own, and how it influences sustainable design. Chapter 21 of Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World discusses the influence of climate change on interpretation, and “taking into account projections from science about how things might be in the future if we aren’t careful in the present” (Beck et al., 2018). This is where biomimicry can help inform people about these scary projections, in a way that is easier to understand and that you can physically see through design.

Biomimicry is all around us, without even realizing it. In fact, as I was reading Chapter 21 of Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World, biomimicry was mentioned, when discussing a beautiful event witnessed in nature; “And reflecting up from the landscape, in the center of the rainbow, were fingers of light, like the spokes of a wheel, shooting into the darkened clouds above” (Beck et al., 2018). Were spokes of a wheel inspired by beams of light? Maybe! We are so influenced and inspired by nature that we are not 2 separate entities, we are connected together, like threads in an interwoven web.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

Biomimicry Institute. (2024, September 20). What is Biomimicry. The Biomimicry Institute. https://biomimicry.org/inspiration/what-is-biomimicry/

Ivanić, K. Z., Tadić, Z., & Omazić, M. A. (2015). Biomimicry–an overview. The holistic approach to environment, 5(1), 19-36.

Verbrugghe, N., Rubinacci, E., & Khan, A. Z. (2023). Biomimicry in Architecture: A Review of Definitions, Case Studies, and Design Methods. Biomimetics, 8(1), 107.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Kattrina!

Your blog was so fascinating to me! I loved your mention towards the end about sending readers in a million directions, because it embodies how much you were able to teach in such a short period of time! I enjoyed that your focus was about deep sea animals, as it is so different from my own knowledge and experiences with nature. Like you, I was shocked to read that these animals have evolved without eyes. My experiences with nature have typically revolved around landscapes and climate change as opposed to evolution, so it was cool to have such a different insight. As I was reading, I was thinking about how I wanted to see examples of these creatures, and was pleasantly surprised to find the link you put, super cool! As I continued reading your interpretation on this, it made me think about Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, and how this has applied to both humans and other species, where we have evolved and changed over time (Than et al., 2022). I really liked how you took it a step further to discuss how our environment affects the way we interpret things, which brings me back to my original point of how differently we went about this blog post. I think that's what I love about this course, and nature interpretation in general. Our different backgrounds and environments, like your comparison to you and your roommates family activity types, leads to us experiencing such different things. These things shape how we live our lives, and in turn, how we are as interpreters, and the information we share.

Than, K., Taylor, A. P., & Garner, T. (2022, October 14). What is Darwin’s theory of evolution? LiveScience. https://www.livescience.com/474-controversy-evolution-works.html

The most amazing thing about nature!

Hey everyone, it’s been a while! Welcome back to my blog.

Today I want to talk about something really fascinating to me. Not sure how fascinating you all will find it but it really blows my mind to think about.

I learned this fascinating thing while I was studying for my DAT test this summer. While studying for the biology section, a fact popped up about how dark the very deepest depths of the ocean are – like pitch black! Which then led me to a deep dive where I learned a crazy fact (that may be super obvious to most of you, but I just never thought about it).

The DEEP SEA ANIMALS who live in these pitch black areas, have evolved WITHOUT EYES…because they don’t even NEED them! These animals live in COMPLETE DARKNESS! This complete darkness begins at the Midnight Zone (1000-4000 meters deep) of the ocean and below (Scott, 2024).

Some of these animals (who have eyes) evolved bioluminescence to be able to see which is also super cool.

Check out this link to learn more!

The big-picture super fascinating takeaway about nature that I gathered from this wormhole I got sent into is how insane our adaptability and evolution is depending on our environment.

Yes, I know, there are full courses on this and this maybe shouldn’t be a big realization for me at this age…but it totally was! I had never thought about it this much until this summer! A fish with no eyes, living in complete darkness!!!

Anyway, back to interpreting this though…

When I hear something like this, it truly opens my eyes about nature itself. For example, just humankind. Comparing a bicyclist to someone who isn’t very active, the cyclist would probably have really strong quads, because they need to! Someone who’s mainly sedentary likely wouldn’t, because they don’t really need those super muscular quads.

My roommate's family is full of marathon runners and just long distance runners in general. Since that’s the environment she grew up in, she also took part and has incredible endurance when she runs. Me on the other hand, people in my family actually liked to do sprints and quick paced sports like basketball.

Though both of these examples aren’t necessarily evolutionary adaptations, it's just an example of how your environment can impact the way you are and act.

Then I start thinking about how this also affects the way we interpret things. Depending on what experiences one has accumulated, this changes their perception and interpretation of what is around them.

Not to bring up the whole nature vs. nurture debate, but I think they both truly interact with each other in a very complex way.

If you put someone who’s whole family for generations has lived in a climate that doesn’t have much sunlight, and has lots of cold weather, and suddenly moved them somewhere tropical, it would likely take their bodies a long time to get used to it, and vice versa.

But eventually, our bodies would be able to adapt to it. The same way the fish in the deep sea, because of its environment, adapted by using bioluminescence or even evolving without eyes to have their energy used elsewhere rather than on unnecessary sight. Crazy!!!!

These differences that we all share, even between human beings (even though we are the same species) are such an advantage. It is amazing that we have so many different perspectives and ways we interpret based on our personal upbringing and experiences. In Chapter 21 of the textbook it is stated that “we need to become more proactive in making an interpretative approach an integral part of tourism experiences” (Beck et al., 2018, p. 459). Though the context of this was that tourism is a powerful driver for the economy, I think this also ties into the fact that being able to explore a new place with a very different set of perspectives as a local person really adds new levels of depth that the locals probably hadn’t even thought of! The textbook said it well: “taking into account diversity is critical to success” (Beck et al., 2018, p. 461).

Anyways, that is all from me this week. Sorry if I sent you into a million different directions in this post. The way we are so diverse in nature and really change based on our environments is truly so fascinating, I could talk about it forever!

Take care,

Kattrina

References

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

Scott, K. (2025, January 10). Animals of the ocean depths. Oceana. https://oceana.org/blog/animals-of-the-ocean-depths/

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Meghan,

I really loved the way you described nature as an orchestra, expanding on the idea proposed in The Music of Nature and the Nature of Music (Gray et al, 2001). When I was writing my own blog post, I was thinking about sounds in nature such as leaves in the wind, rivers flowing, and bird calls, as separate entities. I did not think about the way they all come together, like an orchestra the way you illustrated and elevated. It is a really beautiful way to define nature’s different musical elements.

This reminds me of the video, the 6 Blind Men and the Elephant in Unit 07, where each blind man touched a different part of the animal. This resulted in all of them having partially true, but different, interpretations. This illustrates the different perspectives that shape our understanding of certain areas, such as music within nature. The blind men had to put together all of their different understandings of the elephant to see the full picture. This is the same we must do when interpreting music. We must look at it as an orchestra, combining humans' role in music, as well as other species and natural sounds and rhythms.

I also appreciate how you touched on the example of Finnish folk poetry and the way it was performed (Sahi, 2010). It also alluded to the need to combine various perspectives - cultural, historical, and ecological. These aspects worked together, like an orchestra, to enrich the visitors' experience and understanding.

Nature Interpretation Through Music

Music is often defined as patterns of sound varying in pitch and time, created for emotional, social, cultural, and cognitive purposes. However, long before humans composed symphonies or folk songs, music existed in the natural world. The rhythmic crash of ocean waves, the melodic calls of birds at dawn, and the rustling of leaves in the wind all contribute to a vast and ever-changing soundscape. Nature itself can be understood as an orchestra, constantly composing patterns of sound that shape human experiences and emotions.

One of the most fascinating examples of music in nature is the song of the humpback whale. These undersea vocalizations are structured in ways similar to human music, following patterns governed by rhythm and repetition (Gray et al., 2001). Singing humpbacks use phrasing that mirrors human musical compositions, with song durations falling between that of a modern ballad and a symphonic movement (Gray et al., 2001). In addition to individual animal songs, nature's ambient soundscapes function like an orchestra in their complexity (Gray et al., 2001). Each creature contributes its unique frequency, amplitude, and timbre, creating a layered and immersive environment. Just as each instrument in a symphony has a designated role, every voice in a natural habitat occupies its own niche, forming a dynamic and harmonious balance of sound (Gray et al., 2001).

Nature is deeply embedded in human music, shaping melodies, rhythms, and themes across cultures. Finnish folk poetry, for example, has traditionally been performed through song, incorporating elements of the natural world into its lyrics and melodies (Sahi, 2010). These folk songs capture a deep connection between people and their environment, depicting forests, waterways, and wildlife with rich language (Sahi, 2010). Music can also be intentionally used to interpret and enhance human interactions with nature. During the opening day of Sipoonkorpi National Park, a folk music performance was staged within the forest to highlight the local Swedish-speaking cultural heritage and the historical significance of traditional agriculture (Sahi, 2010). By integrating music into the natural setting, the performance reinforced the connection between culture and the environment, enhancing visitors' understanding of the park's history and ecological significance.

Rather than a single song, an entire album immediately transports me to a natural landscape. Austin by Post Malone, released in July 2023, became the soundtrack to two trips that hold a special place in my memory. The first was a visit to my friend's cottage in Sauble Beach. The album had just come out, and I listened to it constantly while spending time by the water, enjoying bonfires, and relaxing in nature. A week later, my family rented a cottage in Grand Bend, and I played the album during the scenic drive from Sauble to Grand Bend. The music became intertwined with the experience, shaping my memories of long days on the beach, quiet evenings around the fire, and the feeling of unwinding in nature before the start of another school year. Now, hearing the album instantly evokes memories of those peaceful days, illustrating how powerfully music can anchor us to natural landscapes.

What song or album immediately transports you back to a favourite moment spent in nature, and why do you think this connection is so strong?

Gray, P. M., Krause, B., Atema, J., Payne, R., Krumhansl, C., & Baptista, L. (2001). The Music of Nature and the Nature of Music. Science, 291(5501), 52. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A69270354/AONE?u=guel77241&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=fb9366a8

Sahi, V. (2010). Using folk traditional music to communicate the sacredness of nature in Finland. https://ares.lib.uoguelph.ca/ares/ares.dll?Action=10&Type=10&Value=354143

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 07: Music & Nature

When I think about music, what immediately comes to mind is Spotify, the radio, singing, and instruments. Arguably, I would think that is what would come to mind for the majority of people. Even though I love and enjoy nature in every form, and consider myself knowledgeable about many aspects of it, I do not typically connect it to my own idea of music.

We always end up associating the creation, production, and performance of music with humans, and our species. In fact, I decided to search up ‘music in nature’ and ‘nature in music’ on Google out of curiosity. Funny enough, the majority of pictures that showed up were people sitting in nature, singing, with a guitar, or wearing headphones. Why is it that we associate music with people? What about other species, or the sounds that parts of landscapes create themselves? Well, what if I told you that some of the core aspects, that rhymes and the ideas of using musical instruments, comes from animals? Species that predate us by millions of years use these same elements (Gray et al, 2001). In fact, “The ability to memorize and recognize musical patterns is also central to whale and bird music-making” (Gray et al, 2001). This makes me think of how often music is used for memorization, such as songs about places in the world or numbers or names. When I want to retain information, I find it easier to remember by making up a song for it. Did I learn this from nature? How can this contribute to my role as an interpreter? I subconsciously use music and rhymes for my own memorization, yet I have never thought about using it as a way to teach others, especially if it is new or complex information that could be harder to retain.

To end off this blog post, I want to share a song that takes me back to a natural landscape. As I have mentioned here before, I had the privilege of being able to study abroad last year. Somehow, this increased my love for nature even more, because I was able to see its beauty in new ways, in many different places. One of those places was Scotland, where I decided to do a solo weekend trip to see the Scottish Highlands. I was in a bus full of groups of people, and as the only individual of the party, I was put in the single seat next to the bus driver. At first I did not know how to feel about this, but I left feeling extremely grateful for it. I could immediately tell the driver had a love for what he did, and he had an entire playlist curated for the trip. As I sat next to him, I could see the connection he made to each song and what was in front of us. A particular song he played stuck out to me, titled The Glen by Beluga Lagoon. Every time I hear it, it takes me back to beautiful rolling mountains, and the sense of place and peace I felt on the trip.

Gray, P. M., Krause, B., Atema, J., Payne, R., Krumhansl, C., & Baptista, L. (2001). The music of nature and the nature of music. Science.

A picture I took on my visit to the Scottish Highlands, listening to The Glen by Beluga Lagoon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Skylar,

I appreciated the depth of your analysis of Edward Hyams quote. It was really cool to read how we both analyzed the same quote similarly, but also different. I found it helpful that you added a photo of Edward Hyams, it is helpful to put the quote to a face.

It is neat to see the way we all envision things differently. The railway station you envisioned, that you added in a photo of, is very different from how I visualized it. Instead, I saw it as an enclosed station, that is typically underground. I think I thought of it this way because it is easy for us to forget about something when we can not really see it. It made me think about how differently we all provide context as interpreters, even if it is generally the same information.

Here is something similar to what I envisioned

This leads into the part where you discussed searching up the term nature history, and how the picture/article only really focused on animals. Funny enough, when I was thinking about nature interpretation when writing my own blog post, I actually was not thinking about animals at all. I instead only really thought about humans, our landscape, and physical objects. There are so many components of history that it can be hard to examine them all. However, the textbook outlines 3 types of authenticity; objective, constructed, and personal, stating that an interpretive experience may include all 3 (Beck et al, 2018). This allows for visitors to identify with different parts of history, and be able to delve into their own imaginations to experience it.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

"Keeping History Whole: Edward Hyams on Memory, Integrity, and the Relevance of the Past"

In Edward Hyams The Gifts of Interpretation, the argument posed relates to the significance of historical memory where he suggests that despite antiquity possessing itself no sense of special integrity, in seeking to keep things whole, an awareness of the past is required. Hyams utilizes a railway station as a metaphor in an effort to offer a critique on the ideology that history is no longer relevant after it has passed.

Photo of Edward Hyams Himself

Hyams reveals that integrity is more than simply about ideas of morality and honesty and instead are centered on a cohesion of values and ideas over a period of time. Where history becomes forgotten or fragmented, individuals are no longer capable of maintaining a coherent understanding of both the present and the future. Thus history memory is in essence separate from nostalgia for things of the past but rather centers on ensuring a sense of continuity in frameworks established along an ethical, intellectual and cultural landscape.

The analogy of the railway station provided by Hyams emphasizes the notion that simply because a person leaves a station does not mean it no longer exists, as the presence of the station remains a tactile part of the journey. Similarly, one’s past both personally and collectively does not vaporize once they move along and in essence it offers a shaping factor to the path whether it is chosen to be acknowledged or not. Ignoring history, Hyams argues, is to pretend that it at no point had an impact on where the individual or group stands today.

The Railway Station I Envision, however, this one was actually located in Oakville, ON.

Hyam’s perspective reiterates arguments posed in Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World by Beck, Cable, and Knudson. In chapter 14 of this text. an exploration into how the written word provides a vital service in the preservation of historical integrity is offered. These authors highlight that written interpretation is less a task of sharing facts and more so about creating narratives which allow audiences to connect with the past on levels of both emotion and intellect. These narratives are pivotal and without them historical memory can succumb to ineffectiveness in molding and shaping our collective understanding.

Chapter 15 of Interpreting History reiterates Hyam's belief that history is an evolving interplay rather than a set of solidified records. This chapter focuses on the necessity of contextualizing historical events in an effort to allow their relevance to remain intact. This is allied with in Hyam’s writing which illuminates the concern of observing history as an act that is over with which ultimately leads to broken perceptions of reality. The authors reveal that holding an effective interpretation actively engages the audience and pushes them to seek purposeful reflection whereby they can learn lessons that can be applied to modern issues.

Both Hyams and the authors of Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage for a Better World highlight the need for our responsibility is to remember and learn from history rather than worship its moments of glory and that in doing so we maintain the integrity of our knowledge collectively. Interpretation of history by means of literature, museums and public conversation facilitates maintaining sight of the past’s influence on both the present and the future.

I decided to do a Google Search for the term "nature history", and stumbled across this photo taken at the Royal BC Museum. I found it interesting how this focuses solely on animals, rather than plants as well or other natural artifacts.

What do you think? Do you agree with Hyams’ perspective on historical integrity? How do you see the past shaping our present?

Share your thoughts in the comments!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 06: Unpacking Edward Hyams Quote, and How it Relates to Us Today

There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it. (Edward Hyams, Chapter 7, The Gifts of Interpretation)

It is funny how we think we know a lot about something, until we are given a different perspective or narrative. When I first started this course, I knew very little about nature interpretation. In fact, I had barely ever heard of it. After the last 6 weeks, I have learned about nature interpretation itself, how it influenced my childhood and path in life, how it relates to privilege, science, and art, and much more. I considered myself somewhat knowledgeable, because I was thinking about how I would relate all that I have learned so far into my future as a nature interpreter. When I thought about nature interpretation, I was primarily thinking of how it relates to the present and the future. In fact, when I thought about it in relation to the past, I was only thinking about my own personal history, not the role an interpreter plays in actually sharing about history itself.

Edward Hyams quote provides us with what it means for something to have historical significance, and how interpretation allows for that to happen. When he is discussing integrity, he is referring to its preservation. How is an object, an event, or a person's legacy preserved? Through interpretation. Think about a store, filled with a bunch of different items. Except nothing has any information, titles, or dates, even the store does not have a name. Now, think about that same store, except it is now disclosed as an antique store. Every item is explained; what it is, where it came from, how old it is, the purpose it served, etc. Now, you have the ability to learn, the ability to understand the history of the item and why it was important. There was no peculiar merit in those objects, yet once they were interpreted for you, there is a memory to be unlocked, knowledge to be had.

When deciphering the second part of the quote, it made me think about how we perceive our landscapes. The railway station metaphor is alluding to people only reflecting on their immediate experience. As climate change continues to be a pressing issue, this metaphor relates to the divide our society faces. A growing standpoint is acting now to mitigate the effects of climate change, for us, but also for our future generations. Others still have the belief that nothing extreme will happen in their lifetime, so they prioritize short term benefits for themselves, such as overconsumption of greenhouse gases, knowing it will negatively affect others in the future. This relates back to the discussion in the textbook Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World, about ‘truth’ and how it can be hard to navigate in interpretation (Beck et al, 2018). What if people have different versions of the ‘truth’? When discussing climate change in the future, some will refer back to it as a crucial turning point in our history, while others will not deem it historically relevant at all. As interpreters, we must navigate the fine line between truth, and opinion.

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage: For A Better World. SAGAMORE Publishing, Sagamore Venture.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 05: Environmental Injustice

With this week being a free write for our nature interpretation blogs, I want to dedicate this post to discussing and highlighting environmental injustice. Environmental justice is a relatively new term for me; I only learned about it last year, when I was studying abroad and taking a course on climate change. I became so passionate about the topic that last semester I ended up writing my thesis on environmental injustice, and how natural spaces can be designed to tackle it. It allowed me to be able to educate myself on how low income and minority communities are affected disproportionately by climate change. Environmental justice is defined as “the just treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of income, race, color, national origin, Tribal affiliation, or disability, in agency decision-making and other Federal activities that affect human health and the environment” (US EPA, 2024). This relates back to learning and discussing privilege in Unit 3. As I previously shared, I have had the privilege to have a positive relationship with nature. Typically, when we think about nature and our environment, we see it as something beautiful, something we can find peace and comfort in. Learning about environmental injustice taught me that this is not always the case. Certain individuals, groups, and societies endure amplified environmental burdens such as low air and water quality, exposure to toxic waste and pollution, lack of green space, climate change vulnerability, food insecurity, disproportionate health impacts, and much more. When researching how to work towards amending these, a significant problem that I learned can arise is green gentrification, where residents are displaced as a result of introducing new green spaces to a community. One of the ways to prevent this is involving the community through every step of the design process, and allowing them to have their say in policy making. However, as we have learned in Unit 3, sometimes individuals do not get involved, not because they do not want to, but because they can’t, due to a variety of different barriers. A study in the paper Evaluating environmental education, citizen science,and stewardship through naturalist programs discussed the involvement of 2 different naturalist training programs in the United States (Merenlender et al, 2016). In both programs, participants were majority white (over 80% in both programs), and majority had higher education. The paper stated that barriers need to be reduced to encourage participation in minority groups. Recognizing these disparities is the first step in addressing them.

Learning about environmental injustice has allowed me to have a more in depth understanding on the relationship between people and nature. Access to clean air, water, and green space should be a right, not a privilege. By actively overcoming challenges that prevent certain groups from participating, we can allow for all voices to be heard, and become involved. While I can never fully understand the full effects this has on certain groups, I can continue to educate myself, and share what I have learned and researched to others.

Merenlender, A. M., Crall, A. W., Drill, S., Prysby, M., & Ballard, H. (2016). Evaluating environmental education, citizen science, and stewardship through naturalist programs. Conservation Biology, 30(6), 1255-1265.

US EPA . (2024, November). EPA. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/learn-about-environmental-justice

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hi Zoe,

When I was reading through your post, I appreciated that you included your own favourite outdoor activities. I loved that you also asked this back to your readers, to have an interactive component and allow for critical reflection. One of my favourite outdoor activities is simply just walking. I love that I can walk the same path, and each time I see something different. I think my favourite part however, is seeing other people walking too. It means that they took time out of their day to prioritize mental and physical well being, and spend time with nature. You can see the way it transforms someone, and the positive energy people radiate. When I go on walks in nature, it is quite common that people will say hi, or let me know about something up ahead, or even just give a smile. There's an unspoken connection, regardless of the fact we have never met, and it is because we are being tied together by nature.

As I am writing this, I realize that I have not gone on a walk in nature in quite a while. Why? It is something I love doing, and I know it is good for my physical and mental health, yet it is still so easy to put it on the backburner. While discussions of mental health are becoming more prevalent, it is still so effortless to be consumed by school and work. Reading your post reminded me of how much I value time in nature, yet how easily it gets pushed aside in the busyness of daily life. Maybe this is the reminder I needed - thank you for sparking this reflection!

Nature and it’s effect on Mental Health

For my blog contribution this week, I would like to discuss the positive impacts nature has on mental health-an especially important topic. Being in nature has been shown to have incredibly positive effects on mental health.

Physical Activity

One thing that really supports my mental well-being is physical movement. Exercise releases endorphins, those "feel-good" chemicals that lift your mood. Being active and the relaxing effect of the outdoors, creates a powerful combination for improving mental health.

Some of my favourite outdoor activities include:

Skating

Skiing

Sledding

Swimming

Hiking

Camping

These activities not only provide enjoyment but also provide a sense of accomplishment when we set and achieve goals, further boosting mood and confidence.

I just thought this was funny. Plus there’s so much room outside for activites so it applies!

Disconnect to reconnect

Technology has become a both a blessing and a curse. Technology can often lead to overstimulation and mental health struggles. When I go camping or engage in outdoor activities, I make a conscious effort to disconnect from my phone and social media. This allows me to step away from schoolwork/work, my online social life and random information.

Taking this break helps me reconnect with myself and those around me. Nature offers a chance to slow down and quiet the mind. It provides a break and a reset that enhances both future social interactions and productivity in daily life.

Mental health and nature

Regularly exploring nature in nature has been proven to improve several mental illnesses like anxiety, depression, attention difficulties and many more. Frequently spending time outdoors can also boost mood and improve overall happiness. It leaves individuals feeling more connected to the earth and therefore can drastically improve wellbeing. Being in nature with friends and family can also make you feel more connected with them instead of being on your phone. Here is a blog from the Royal College of Psychiatrists about mental health and nature:

How can nature interpretation help?

As we’ve learned in this course, nature interpretation can be viewed through many lenses and expressed in a variety of ways. This not only allows us to engage with nature creatively ourselves but also helps present it in ways that attract diverse audiences.

Different perspectives, such as art, science, and history, appeal to many different groups. We've also learned the importance of recognizing privilege, of our own and of others. This allows us to make nature interpretation more inclusive. This involves acknowledging barriers such as language, physical limitations, and intellectual challenges, and incorporating methods to overcome these barriers.

These tools allow us to create important content whether it's a podcast, speech, blog, or travel guide that sparks interest and curiosity. When we inspire people to explore nature, we encourage them to try new outdoor activities and develop a deeper connection with nature.

This passion for nature is powerful, especially given its positive impact on mental health. We can motivate people to spend less time on their phones and more time enjoying outdoor activities. We can encourage others to spend quality time with loved ones through camping or hiking. We can create curiosity and appreciation for the beauty of nature, from sunsets and mountains to butterflies and unique species. By doing so, we promote better mental health and overall well-being. Through thoughtful and inclusive nature interpretation, we have the power to inspire others and promote a lasting love for the outdoors.

Questions

What are some outdoor activities do you take part in? How do they improve your mental health and wellbeing?

How do you think you can inspire others to spend more time in nature?

What outdoor activities do you do with others? How do they affect your relationships?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 04: Interpreting Nature through Art

Interpretation begins with a strong set of facts and information. As an interpreter, we strive to display these facts in ways that people understand and recognize in their own way. We want them to feel an emotional connection, to learn and to be inspired.

To interpret nature through art, we must first recognize it as a medium in which to communicate. It is a resource that is so easily accessible to us, yet easy to not utilize if we believe artistic ability is not something we personally possess. As stated in Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World, “in interpretation, the arts are a means, but rarely the ends” (Beck et al, 2018). This resonated with me because it exemplifies the way art can be used as a tool, to evoke an emotional connection and facilitate a deeper understanding, to convey messages based on individual perception. As a landscape architecture student, this is exactly what I aim to do. I use art; creating 3D models, perspectives and renderings, sketches and diagrams, to showcase both nature in its current state, and how those same natural areas can be redesigned to be functional while still promoting sustainability. Nature has been my guide to creativity, my art is based on it. While being students in this course, our passion about the environment is at the forefront. I see myself as a bridge between nature and people. However, as we have learned in previous units, there are many people who do not have a connection with nature, for various reasons. Art is a way to attract people in, and can then be utilized by integrating with facts and science. This aligns with Tilden’s 3rd Principle of Interpretation: “Interpretation is an art, which combines many arts, whether the materials presented are scientific, historical, or architectural. Any art is to some degree teachable. (Beck et al, 2018).

Building on this, these principles have been expanded on, and correspond with a gift. The Gift of Beauty is described in the text as how people perceive the beauty in their environment through interpretation. People typically define beauty based on what they actually see. Through the unit and my own reflection, I have learned that I interpret the gift of beauty not based on the beautiful things I see, but how those things make me feel, what I learn from it, and how I carry it with me in the future, after it has taught me something. The gift of beauty is the gift of connection, connecting to nature in our own way. As an interpreter, it is also our responsibility to not only recognize our own interpretation, but guide others to find their own connection through interpretation. This is why I think art is such an important tool. I want to ensure that others do not just see the beauty, but feel it too.

I want to end this blog with a quote from Aristotle that embodies the essence of interpreting nature through art:

‘Art takes nature as its model’

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayah,

Your blog post about interpreting nature through art allowed me to grasp the concept in a new way. I loved the way you described it like a puzzle, it was such a beautiful way to exemplify people's individual connections to nature, what it means to them, and how they interpret it. Your mention of nature not just being something we observe, but something we experience, reminds me of Tilden’s introduction of the idea ‘the story’s the thing’, as mentioned in Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World (Beck et al, 2018). Art can be the medium we use to communicate, a method to focus on the importance of the storyline. It is not about just presenting the facts, but what emotions are provoked through the way you communicate to your audience as an interpreter. I noticed that this is similar to the way you described the gift of beauty. Without directly saying it, you were able to capture how it really is not about what you say (the facts), it is how you say it (telling a story to awaken feelings and emotion).

I also really appreciated your mention of Sam Ham and making concepts relevant to the audience. As an interpreter, all you want to do is to communicate that to allow visitors to think and feel something, regardless of if they are thinking and feeling the same things you are. It reminds me of Tilden’s overriding principle of interpretation; sharing what you love, and love sharing it to others, you feel its ‘special beauty’ (Beck et al, 2018).

Week 4: Who are you to interpret nature through art? How do you interpret “the gift of beauty”?

When you think about it, interpreting nature through art is kind of like being handed a puzzle where the pieces are scattered across a landscape. Who am I to take those pieces- those sunrises, wildflowers, and forests- and make sense of them? Well, maybe that is the point. We’re not here to solve the puzzle entirely but to reframe it, add meaning, and invite others to look at it from different or new angles.

Nature isn’t just something we observe; it’s something we experience. Sam Ham’s work on thematic interpretation reminds us that our role as interpreters- whether through art, writing or conversations- is to provide focus and spark curiosity. Ham’s TORE model (Thematic, Organized, Relevant, Enjoyable) is like a cheat sheet for making those interpretations meaningful. At its core, it’s about delivering a theme that sticks, something that provokes thought and connects with people on a deeper level.

When I experience nature, I often think about the connections between the tangible and intangible. David Larsen’s concept of linking what we see- like the veins on a leaf- with what we feel- like the sensitivity of a quiet forest- has been pivotal. It’s not just about observing what’s in front of me but about connecting it to something greater and more universal, like peace, awe, or even nostalgia. That is “the gift of beauty”. It’s the ability to recognize what’s extraordinary in the natural world and reflect on it in ways that inspire emotions or meaning.

Ham also discusses how crucial it is to make concepts pertinent to the audience. The true magic takes place there. After all, beauty is quite subjective. What resonates with you may not be the same as what I find beautiful. But if my interpretation can make you pause, think and feel something, then I’ve succeeded in sharing that gift.

The concept of “genius loci” or a place’s spirit, is also discussed in this chapter. When understanding nature, this idea strikes a deep chord. Every mountain, park, and forest have distinct personality and tale to tell. I try to convey the essence of a place when I paint or write about it, not just how it seems but also how it feels to stand there, take in the atmosphere, and let its presence take over you.

At the end of the day, interpreting nature through art isn’t about claiming authority over it, it’s more about creating a dialogue. It’s about inviting others to see what you see and feel what you feel. It’s about reminding ourselves that beauty is a gift meant to be shared- and that we all have a role in passing it along.

So, who am I to interpret nature? I am just someone who wants to make sense of the puzzle and share the joy of putting a few pieces together. And maybe, just maybe, that’s enough.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Good morning everyone! I just wanted to share a photo of the sunset I took last night :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zoe,

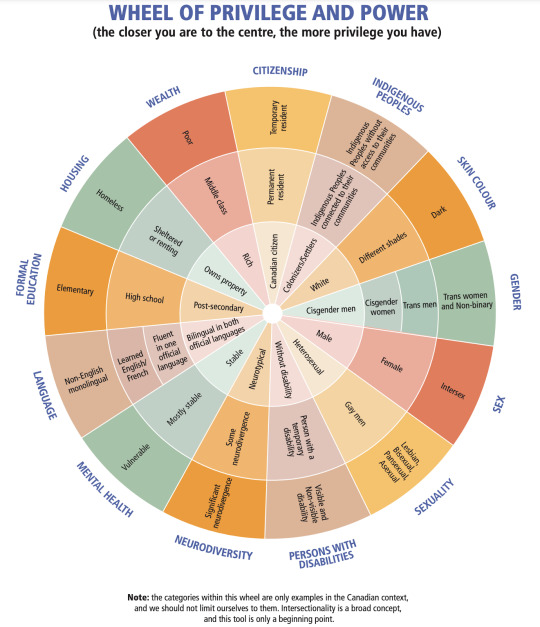

Your post was extremely insightful and powerful. I really appreciated it, especially because of the visual you presented from the Government of Canada. As someone who is primarily a visual learner, it was really helpful to see the Wheel of Privilege and Power. It also really puts privilege into perspective. I realized that before seeing it, I looked at privilege in terms of an all or nothing approach; you either have it or you don’t. I did not think about how there are different levels, and that privilege is not just there or not there, it affects different people in different ways, privilege is a spectrum.

I also can appreciate your own reflection on privilege based on Peggy's McIntosh’s idea of an invisible backpack, and it inspired me to do the same. I am a white female, who speaks English, was born and raised in Canada, and live with my parents who are still together. I had the privilege of being able to go to school, get an education, and be able to learn something I can now teach to others. However, I do live with Type 1 Diabetes, which is a disability, so I appreciate your mention of this in the designs of parks. For me personally, parks and other spaces can be designed with many bathrooms with sharp boxes, rest stops, and accessibility to food or drinks to be purchased in the event of low blood sugar. This unit allowed me to reflect on myself, and helped me understand the extent to how privilege can influence so many different factors of nature interpretation.

A Reflection of Privilege

I think it is important for everyone to take time and reflect about our positions, privilege, and where we currently stand. I define privilege as a person having access to more possibilities due to biases, as well as many provided and inherited traits and factors (including sociological, physical, mental, and economical sliding scales, just to name a few). The government of Canada has provided a great way to visualize this concept with the wheel of privilege and power.

Photo 1: A colorful three layered Wheel of Power. The center of the wheel highlights circumstances of more privilege, and the outside is those with less privilege. From: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/ircc/documents/pdf/english/corporate/anti-racism/wheel-privilege-power.pdf

Just as this Wheel of Privilege provides a starting point for reflection around privilege, I found Peggy McIntosh’s concept of the invisible backpack offered another way for me to reflect. When I unpack my invisible backpack, and examine my own privilege, I acknowledge that I am a white female identifying settler, who speaks English as my first and only language. I was able to grow up encouraged to experience nature, and provided with many opportunities to do so. I am very privileged to be an undergraduate student free to choose my education in Zoology and Fine Arts. I am very grateful for the many gifts and opportunities that have been presented in my life, and am working on recognizing the powers that these opportunities have granted me. For example, I am very grateful for the support of the family and friends, who have encouraged me to receive this education, and would not be where I am today without them. I am also very grateful to have experienced the wonders and beauty of Turtle Island, but I understand that my experience has been from a settler point of view, and belonging to the created country of Canada. I have easy access to clean water, food which are provided from these lands. However, I know just because my privilege has provided me with conflict free and safe experience in Canada, but I know others can not say the same.

It is important to be able to recognize my own privilege because privilege is relevant with all social interactions in society, and definitely comes into play during nature interpretation. This week's readings touched on some of the instances where privilege and barriers come into play. For example, it was discussed that minorities are underrepresented visitors at a lot of national parks, compared to caucasian visitors. This could be due to many factors, like cultural values, fear of nature, perceived stigmas, poor transportation options, and a lack of advertising and awareness. I think there could also be complex factors like socioeconomic influences, preventing people from being able to take time off work and afford traveling to these parks. Of course, I also understand it is difficult because everybody's situations will be unique, and it is my opinion that when we try to look into why some of these barriers exist, the common answers will be generalizations.

The text book reading also discussed the privilege of able-bodied people having easier access to nature than people with mobility disabilities. A lot of parks in the past were not designed to accommodate people with other mobility requirements such as those with walkers, wheelchairs, and canes. As a nature interpreter, it is important to consider the routes and accessibility for all of the guests when designing potential programs. As a currently able bodied person, I don't have experience with what things I should take into consideration when making programs. I think it is an important initiative to work directly with people who have mobility disabilities and collaborate to understand what their needs are.

Being a nature interpreter means knowing your guests, and being able to meet their needs as best as possible in order to provide the best experience. Everybody deserves equal access to the educational programs and ability to connect with nature, but acknowledging privilege means understanding that unfortunately, not everybody will be able to access these opportunities. I think it is important for future aspiring interpreters to receive up-to-date Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion (DEAI) training. I personally want to make sure that I am constantly expanding my world views, and trying my best to bridge those gaps of knowledge between my privileged experiences and the experiences of others. Some goals to achieve this might be expanding the diversity of knowledge by asking for feedback after my educational programs.

I also want to aim to be a compassionate nature interpreter, and try to understand that not everyone will have the same values as myself, and there might be conflicts in the future. Those moments are important because though they may be uncomfortable, sharing our understanding of the world will hopefully lead to taking down walls, and extending one's community. It is my hope to create space and opportunity for everyone to become curious, and inspired to learn more about the world which we all share. I predict that when we take the time to get to know others, and make space for each other, we will be able to improve the capabilities of the nature interpreter role, and the educational spaces being used.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog Post 03: Privilege in Nature Interpretation

You may recall my first blog post, titled My Relationship with Nature. In this post, I discussed how my relationship with nature was formed through my hometown and what was accessible to me. I talked about how I was able to have a positive relationship with nature because I had the privilege to be connected to it, being surrounded by it, and having experiences brought to me. And while that remains true, after completing this unit and reading Chapter 7 of Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World, I realized my understanding of privilege only scratched the surface. Prior, I understood privilege to be defined as what you are given in life, and the opportunities that are handed to you. However, I now understand that it goes much deeper than that. My working definition of privilege now includes the understanding that privilege is not just about having something others do not, but how some have set advantages to even have access to those opportunities, and they did not do anything themselves to earn that. The Youtube video Social Inequalities Explained in a $100 Race really helped me understand this. I encourage everyone to take 5 minutes out of their day to watch it.

Now, how does this apply to nature interpretation, and our future roles as interpreters? Well, as interpreters, we strive to be able to share our craft, tell our story, and get people involved. In order to do this, we must recognize the privilege that comes with visitors actually participating. One main reason visitors do not participate is not because they do not want to, but because they can’t (Beck et al, 2018). In order to eliminate this in the future, our roles as interpreters can include the following: include bilingual interpreters, provide transportation, personally inviting minority groups, have information in various languages and forms, having diversity among staff, having sites developed to different group sizes, having an AODA compliant site, and having programs and activities at various times for all ages (Beck et al, 2018). I can also apply these guidelines specifically to my own future role as an interpreter when designing these sites. Throughout my landscape architecture degree, we have learned the importance of following AODA requirements, how we can ensure our design is accessible, and putting them into practice. As someone who is classified as disabled myself, I have first hand seen the benefits of doing so. I also have had the ability to write a thesis and work on my final capstone project about redesigning urban spaces inspired by nature to tackle environmental injustice. Doing that research taught me a lot about the privilege of access to nature. By applying said research with integration of the guidelines listed above, I can ensure that I am using my skills as an interpreter to confirm I am assessing risks, reflecting on myself, and understanding who my audience will be. This will allow me to do everything I can to see, understand, address, and prevent barriers.